- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- Immigration is not just a US challenge. But on eve of election, it feels that way.

- Today’s news briefs

- Abortion on the ballot: What’s happening in 10 key states

- ‘A bridge to humanity’: Behind a Monitor series on an underreported story

- Who’s the real loser in the 2024 election? Mainstream media.

- Netflix doc takes a new look at the kiss that rattled Spanish women’s soccer

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

The fabulous world of journalistic nuance

Mark Sappenfield

Mark Sappenfield

As people in the newsroom will tell you, I am a nuance fanatic. Put simply, if something isn’t nuanced, I generally don’t believe it. The desire for simplicity leads to the temptation to simplify. The results: polarization and bad policy.

So I love Whitney Eulich’s story today, for the same reasons I loved Francine Kiefer’s last week. We all must have the freedom to make up our own minds about a difficult issue like immigration. But essential to that is actually understanding the complex portrait of what is happening.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Immigration is not just a US challenge. But on eve of election, it feels that way.

The issue of immigration in the U.S. is tumultuous. But underneath the noise, a sea change has occurred that receives far less attention.

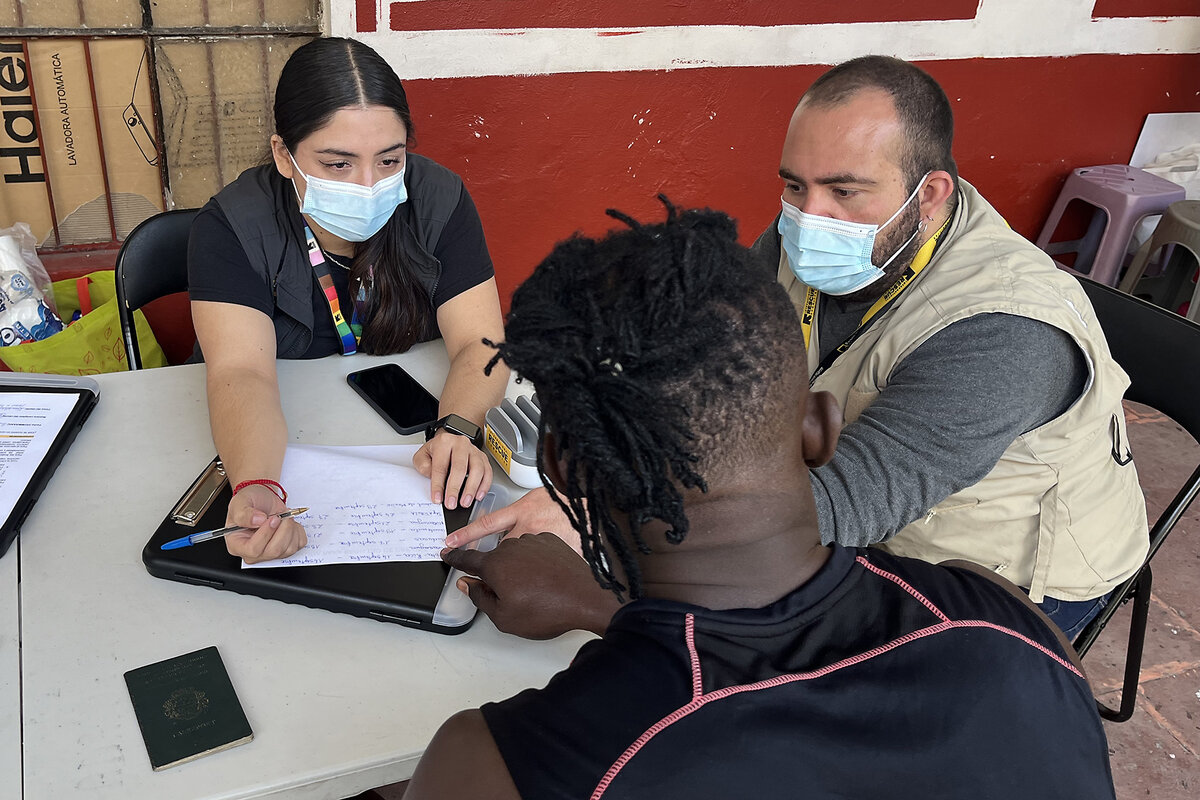

On a recent early morning in Mexico City, two humanitarian workers from the International Rescue Committee secure tables, a medical privacy screen, and a satellite internet kit to a flatbed truck with neon-green straps. They are part of a new “mobile unit” responding to the changing face of migration to the United States in Mexico.

Between 1999 and 2009, men from Mexico, often traveling alone as they jumped over the border or waded across the Rio Grande in search of jobs, made up some 90% of those arrested for trying to cross into the U.S. irregularly. In 2014 came a notable uptick in children and families arriving at the U.S. border from Central America.

Since then, global conflicts, natural disasters, and the COVID-19 pandemic have created powerful push factors. Today entire families flee political oppression, organized crime, war, natural disaster – and poverty. They’re coming not only from Latin America, but also from as far away as China and Sierra Leone.

Yet the discourse around immigration and asylum-seekers, especially in the lead-up to the U.S. presidential election, remains stuck in a stubborn binary: “black and white, legal vs. illegal,” says Jennifer Van Hook, a fellow at the Migration Policy Institute. The reality, she says, is "murkier."

Immigration is not just a US challenge. But on eve of election, it feels that way.

Illegal immigration is an electoral lightning rod of the 2024 presidential race in the United States.

But debates over “criminal” migrants, mass deportations, and American sovereignty obscure a more complicated reality. In particular, who wants to come to the U.S. – and why – has shifted massively in recent years.

Between 1999 and 2009, men from Mexico, often traveling alone as they jumped over the border or waded across the Rio Grande in search of jobs, made up some 90% of those arrested for trying to cross into the U.S. irregularly.

Over the past decade, global conflicts, natural disasters, and the COVID-19 pandemic have brought a much vaster and more diverse group of people to America's southern border. Today entire families flee political oppression, organized crime, war, natural disaster – and poverty. They’re coming not only from Latin America, but also from as far away as China and Sierra Leone.

Yet the discourse around immigration and asylum-seekers remains stuck in a stubborn binary: “black and white, legal vs. illegal,” says Jennifer Van Hook, a professor of sociology and demography at Penn State and fellow at the Migration Policy Institute. The reality, she says, is “murkier.”

And that has implications for the way immigration is accepted, or not, and perceived in the U.S. “There’s a tendency to disregard circumstances in wanting to classify people,” Dr. Van Hook says.

A complex portrait

Take Springfield, Ohio, which gained national attention this year after candidate Donald Trump claimed its growing Haitian population was “eating” the town’s pets.

Many immigrants there have temporary protected status – which grants provisional rights to work and live in the U.S. – yet the discourse centered firmly on America’s problem with “illegal immigrants.”

No group understands the diverse needs and motivations of the constantly changing immigrant population heading to the U.S. better than humanitarian workers in Mexico.

On a recent early morning in Mexico City, two men from the International Rescue Committee (IRC) secure tables, a medical privacy screen, and a satellite Internet kit to a flatbed truck with neon-green straps. These new “mobile units” respond to migrants spread across the country, not just those hunkered at the northern border. They provide access to phone charging stations and information about migrant rights or new technology in the asylum process.

The unit pulls up to the back door of one of the oldest churches in the historic center of Mexico City. Nearby, hundreds of mostly African, Haitian, and South American migrants live in tent camps.

IRC protection officer Carolina Álvarez Barajas helps an asylum-seeker from the Republic of Congo, whose name we aren’t publishing for his privacy, download an application on his phone. But she needs help from someone on her team who can translate for her from French.

Although the app, called CBP One, is the first step for an appointment at a port of entry before filing for asylum, it is available only in Spanish, English, and Haitian Creole, languages that are essentially useless to scores of migrants here today from Africa who speak French or Portuguese.

The Congolese man, who says death threats forced him to flee home, selects Spanish on CBP One and screenshots the buttons he’s supposed to press to check in on the app daily until he’s assigned a date to travel to the border for an interview. He expects it could be months.

Not just an American challenge

Mr. Trump has long railed against undocumented immigration, going so far as to call migrants “rapists.” Nearly 90% of his supporters favor mass deportation of unauthorized immigrants. Meanwhile, Democratic candidate Kamala Harris has faced widespread criticism for her perceived role in 2023’s record-high border crossings (which have since plummeted). She now says she supports a tougher crackdown.

But this isn’t an America-only challenge. Mexico is adjusting to record immigration numbers and its effects, too.

Over the past decade Mexico has formalized, under pressure from the U.S., the policing of migration on its southern border. As Border Patrol encounters have fallen since historic highs last December, apprehensions inside Mexico have grown: double in the first half of this year compared with the same period last year, according to the Danish Refugee Council and IRC. Amid restrictions on asylum-seekers in the U.S., Mexico has had to strengthen and expand its own system. It’s now among the top five receiving countries in the world for new asylum claims.

Hundreds of thousands of migrants are now coming to Mexico from across the globe and remaining longer – sometimes permanently. That has kicked up tensions in some neighborhoods in Mexico City and at the northern border. But unlike in the U.S., the population surge is met with more sensitivity in Mexico, says Eunice Rendón, Mexico coordinator of the Agenda Migrante initiative. Because of Mexico’s history as a country of migrants, “we have more empathy around what is driving people to leave home,” she says.

While anti-migrant voices in the U.S. focus on violence perpetrated by migrants, in Mexico they are clearly victims of it. In a migration reversal, amid an uptick in violence among cartels in southern Chiapas state, some Mexicans are crossing south into Guatemala for safety, says Rafael Velasquez Garcia, IRC’s Mexico country director.

Organized criminals target migrants to boost revenue by selling fake CBP One appointments or charging “exit fees” to move around the country, says Mr. Velasquez. They’re “now finding even greater opportunity with what we estimate [are] about a million people stranded in Mexico.”

“Anywhere else in the world where you have a million people stranded in an environment like this, we would recognize it as a humanitarian crisis and respond to that,” he says. “But right now, there is no humanitarian response plan. … The majority of the response is on the shoulders of local civil society.”

A family affair

In 2014 came a notable uptick in children and families arriving at the U.S. border from Central America, many fleeing violence and intentionally turning themselves over to border agents. That trend has only grown since the pandemic – with huge implications for humanitarian work in Mexico.

When a church in Mexico City, La Parroquia de la Santa Cruz y Nuestra Señora de la Soledad, began opening its imposing, hand-carved doors to migrants in 2017, volunteer Claudia Torres says they were still aiding mostly young men who were just passing through. By 2020, they were helping entire families with young children. Now they work with volunteer midwives who help deliver babies, sometimes even under the church’s roof.

“Families are more complicated,” says Ms. Torres, who sits on the church patio registering arriving migrants, including a young mother from Ecuador who walks in seeking to bathe her two sons.

Once the family walks away, Ms. Torres gestures for another volunteer to come near. “It was that little boy’s seventh birthday earlier this week. We’ll sing him the mañanitas,” she tells her, referring to Mexico’s iconic birthday tune.

By the time the boy’s mother has scrubbed behind his ears, there’s an impromptu party, complete with a tray of chocolate-covered marshmallows and a small crew of volunteers singing and cheering.

The boy beams.

This scene, as joyful as it is heartbreaking, bears little resemblance to the rhetoric on the American campaign trail.

Editor's note: This story was updated on Nov. 1, the same day as publication, to clarify the role CBP One plays in the asylum process.

Today’s news briefs

• North Korea meeting with Russia: Russia’s top diplomat met his North Korean counterpart for talks amid reports that Pyongyang has sent thousands of troops to Russia to support its military in the war in Ukraine.

• Texas hospitals and immigration: Texas hospital patients will be asked if they’re in the United States legally starting Nov. 1.

• Fewer new jobs in October: U.S. employers added 12,000 jobs in October, a total that economists say was held down by the effects of strikes and hurricanes that left many workers temporarily off payrolls.

• Botswana ruling party defeated: Botswana’s president has conceded defeat in the general election. It is a seismic moment that ends the ruling party’s 58 years in power since the country’s independence from Britain in the 1960s.

• New York public schools honor Diwali: For the first time, New York City’s public school students have the day off to mark the holiday of Diwali, celebrated in India and among the global Indian diaspora as the victory of light over darkness.

Abortion on the ballot: What’s happening in 10 key states

The U.S. Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade two years ago, passing the issue of abortion rights to the states – and their voters. Next week’s election will show us how states respond.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

-

Ali Martin Staff writer

Since the U.S. Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade in 2022, eliminating the nationwide right to abortion, the United States has fractured into a patchwork of restrictions on access to the procedure. But in the Nov. 5 elections, 10 states – accounting for one-fifth of the U.S. population – will vote on proposed amendments to their state constitutions, in almost all cases aimed at boosting abortion access.

Easier than amending the U.S. Constitution, this kind of state-by-state modulation illustrates the function that state constitutions are meant to play in American democracy, experts say.

Proposed amendments in three blue states – New York, Colorado, and Maryland – would enshrine abortion rights in their constitutions. Red states, too – Nebraska, Montana, Florida, South Dakota, and Missouri – are voting on varying levels of abortion access. Amendments in Arizona and Nevada would establish abortion rights up to viability.

State constitutions “don’t have the sanctity of the federal Constitution, for better or for worse,” says Justin Long, an associate professor at Wayne State University Law School in Detroit. That likely means, he adds, that in coming elections, some states will see “a back and forth” over constitutional protections for abortion.

Abortion on the ballot: What’s happening in 10 key states

When the U.S. Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade in 2022, eliminating the nationwide right to abortion, it handed the issue to the states – and their voters. The Nov. 5 election, more than any other moment to date, will tell us how states are responding.

Ten states, accounting for one-fifth of the U.S. population, will vote on some kind of abortion amendment to their state constitution. Since the court reversed Roe in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, the United States has fractured into a patchwork of varying restrictions on access to the procedure. About half the country has measures on the books protecting broad access to abortion, and about half the country now has strict limits or an outright ban.

This election will further clarify that landscape, and potentially be decisive in contests further up the ballot by driving turnout. Easier than amending the U.S. Constitution, this kind of state-by-state modulation illustrates the function that state constitutions are meant to play in American democracy, experts say.

State constitutions “don’t have the sanctity of the federal Constitution, for better or for worse,” says Justin Long, an associate professor at Wayne State University Law School in Detroit.

That likely means, he adds, that in coming elections some states will see “a back and forth” over constitutional protections for abortion.

Which states are voting? And what are they voting on?

In Nebraska, voters will choose between two competing abortion amendments. One would effectively codify existing state law, which bans abortion in the second and third trimesters, with exceptions for rape, incest, and to save the life of the mother. The other proposed amendment would protect the right to abortion until viability – considered by most doctors to be around 24 weeks into a pregnancy – or later to save the life of the mother.

If both measures pass, Nebraska Republican Gov. Jim Pillen would have to decide if they are in conflict. If he decides that they are, the amendment with the most votes would go into effect.

KFF

Residents in three states with expansive abortion protections will be voting on whether to enshrine those protections in their state constitutions.

In New York, where abortion has been legal up to viability since 1970, voters will consider a proposed “Equal Rights Amendment.” This would expand its existing prohibition on discrimination based on race, color, and religion to include “pregnancy, pregnancy outcomes, and reproductive healthcare and autonomy,” as well as sexual orientation and gender identity.

In Colorado and Maryland, two of nine states where abortion is legal at any stage in a pregnancy, proposed amendments would enshrine a right to abortion in their state constitutions.

Meanwhile, Nebraska is one of five reliably red states where residents will be voting on abortion amendments.

- In Montana, a proposed constitutional amendment would guarantee a right to abortion before viability. After the Dobbs ruling, abortion remained legal in the state until viability, per a 1999 state Supreme Court decision.

- In Florida, where a recent law banned abortion after six weeks of pregnancy, a proposed amendment would protect a right to abortion until viability.

- In South Dakota – where abortion has been illegal, with some exceptions, since 2022 – residents will vote on amending the state constitution to protect a right to abortion in the first two trimesters of pregnancy.

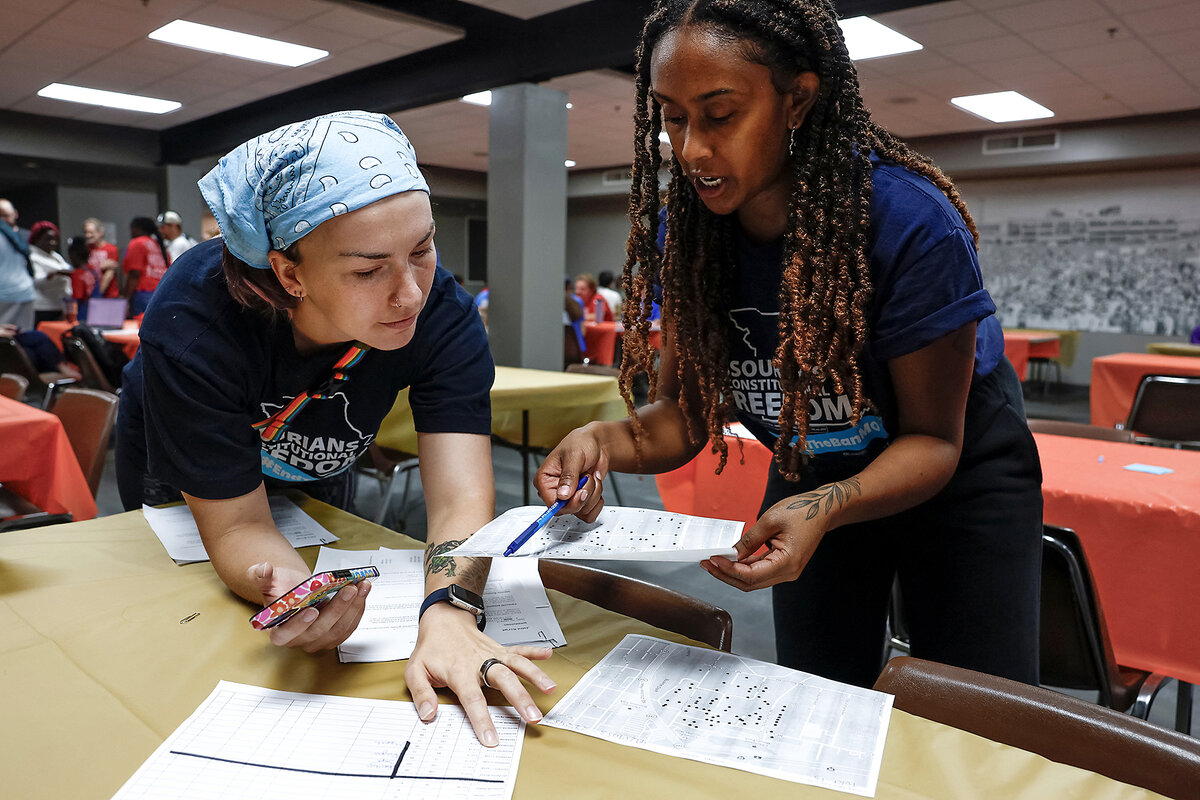

- In Missouri, which also enacted a near-total ban on abortion in 2022, voters will consider a ballot measure that would establish a right to abortion until viability in the state constitution.

Two purple states will also be voting on abortion amendments:

- In Arizona, where abortion is banned after 15 weeks of pregnancy, a proposed constitutional amendment would establish a right to abortion up to viability, and later to protect the life of the mother.

- In Nevada, a proposed constitutional amendment would codify existing state law, which permits abortion during the first 24 weeks of pregnancy.

In most of these states, passage requires simple majorities. The exceptions are Colorado and Florida, where constitutional amendments require 55% and 60% of the vote, respectively.

Recent polling suggests that most of the proposed amendments are likely to pass. But Florida, with its 60% threshold, might not make it. A survey conducted last week by St. Pete Polls showed the Florida abortion amendment falling short with 54% support, while another poll, by the University of North Florida, showed the measure reaching the minimum 60%.

In Nebraska, meanwhile, a recent poll found that a plurality of voters support both proposed amendments, but the initiative preserving the state’s current 12-week ban has slightly more support.

Could these votes affect other races on the ballot?

It’s unclear.

Polls consistently show that supporters of the more expansive abortion rights are more likely to back Democrats than to back Republicans. But data also suggest that a significant proportion of conservatives would be willing to vote in favor of an amendment favoring abortion rights as well as Republican candidates.

In the swing state of Arizona, for example, recent polls show a supermajority of support for the proposed abortion amendment and show Donald Trump with a slight lead over Kamala Harris. In Montana, incumbent Democratic Sen. Jon Tester is trailing in recent polls, but a 2023 survey found that 6 in 10 voters believe abortion should be legal in many or all circumstances.

That’s bolstered hope among Missouri Democrats that the ballot measure will help their party’s candidates, says Steven Rogers, an associate professor of political science at St. Louis University. But “If you look at political science research, there isn’t a lot of evidence that it helps, that there’s reverse coattails,” he says.

How these amendments could make a difference is in close races, if they bring more voters to the polls. With young women in particular – who overwhelmingly support abortion rights and Ms. Harris, but are not yet considered reliable voters – an abortion amendment could attract decisive votes, experts say.

“If the abortion amendments have been an effective mobilization forcer, it could benefit the Democrats,” says Don Levy, director of the Siena College Research Institute.

What could these votes mean for abortion access?

At the moment, the U.S. is split roughly in half between states where abortion is banned completely, or almost completely, and states where the procedure is legal in most or all circumstances.

In 2022, about 21.5 million women of childbearing age lived in states that ban abortion after six weeks of pregnancy or fewer, according to Politifact. If all 10 states pass their proposed abortion amendments, abortion rights will be expanded for roughly 7 million women of childbearing age. For roughly 4 million women of childbearing age, nothing will change in practice.

“In the abortion-access states, what the amendments might do is cause legislators to enact increased protection for abortion access, such as funding or going beyond what the amendment provides,” says Naomi Cahn, a professor at the University of Virginia Law School. “In the abortion-restrictive states, I think it’s much more difficult to say what would happen.”

This election cycle could trigger longer-reaching changes. In some states, there are already discussions over pursuing constitutional amendments to restrict abortion again. In other states, like Arizona, residents will also be voting on ballot questions that would make it more difficult in the future to amend their state constitution.

If the Missouri amendment passes Nov. 5, for example, “It’s widely anticipated that ... in 2025 or 2026, we may have another amendment going the other way,” says Professor Rogers. “We’re going to be in this abortion back and forth for a while.”

KFF

Podcast

‘A bridge to humanity’: Behind a Monitor series on an underreported story

Yes, the U.S. presidential election will be consequential. And yes, big powers and proxies are being drawn into high-profile conflicts. Our international news editor tells why and how we went deep on Sudan, too, where a civil war has been devastating, but where resilience and agency endure.

A land war in Europe. Widening strife in the Middle East. A U.S. presidential election.

The West tends to lose sight of the African continent even in less distracting times. But there’s plenty that’s worth attention in the more than 50 countries there. Sudan’s current conflict is especially stark.

“What makes it really grave is that both sides are using starvation as a weapon of war,” says Peter Ford, the Monitor’s international news editor.

Also present in Sudan: cooperation, resilience, and agency.

“Our stories in and from Sudan are about how … people can rise above that chaos and the difficulties and they can find ways of working together to overcome their problems,” Peter says on our “Why We Wrote This” podcast. That coverage, which included a recent series organized by Johannesburg-based editor Ryan Lenora Brown, helps give readers “a really different picture of life in Africa.”

The work builds a bridge for Monitor readers. “It’s a kind of bridge of humanity, if you like,” Peter says. “And I find it a very fulfilling job to keep that bridge maintained.” – Clayton Collins and Mackenzie Farkus

Find article links and a transcript here.

Why We Went Deep on Sudan

Who’s the real loser in the 2024 election? Mainstream media.

The 2024 election may be the tipping point in which the digital culture determines what information is consumed and the public turns from the old reliable mainstream media to siloed, partisan news sources.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

The decision by The Washington Post not to endorse a presidential candidate has roiled the newspaper, triggered a flood of subscription cancellations, and generated reams of commentary about media ownership and journalistic integrity.

In the final week of the presidential campaign, the controversy felt like a holdover from the mass media past. Media fragmentation, partisanship, and distrust of legacy news outlets now prevent campaigns from directly pitching to the largest possible audience.

The hunt for blocs of persuadable voters who get their news from algorithmic digital feeds has propelled presidential candidates to podcasters and social-media influencers, largely bypassing traditional media and journalistic scrutiny. News reports now jostle for attention with text, audio, and video generated by political partisans, sometimes spliced with fake or digitally manipulated images, along with clickbait claims and hot takes from obscure sources. Truth is increasingly elusive.

“I think that this election will be looked at by future historians as a time when the podcast culture and the digital culture determines what constitutes information that should be consumed,” says Jeffrey Dvorkin, former NPR ombudsman. “The challenge for mainstream media is to reaffirm their reliability. But too often, the public doesn’t care as much about that as perhaps it once did.”

Who’s the real loser in the 2024 election? Mainstream media.

The decision by the Washington Post not to endorse a presidential candidate for the first time in 36 years has roiled the newspaper, triggered a flood of subscription cancellations, and generated reams of commentary about media ownership and journalistic integrity.

But in the cacophony of a campaign in its final week, the tempest over endorsements felt like a holdover from a passing era of mass media consumption. Media fragmentation, partisanship, and distrust of legacy news outlets, particularly from the right, now prevent campaigns from directly pitching through mainstream media.

The hunt for blocs of persuadable voters who get their news from algorithmic digital feeds has propelled presidential candidates to the studios of podcasters and social-media influencers, largely bypassing traditional media and journalistic scrutiny.

News reports still move across digital platforms and feed election-related debate. But they jostle for attention with text, audio, and video generated by political partisans, sometimes spliced with fake or digitally manipulated images, along with clickbait claims, counterclaims, and hot takes from obscure sources, churned into a ceaseless flow of monetizable content. Expertise takes a back seat to emotions. Truth is increasingly elusive.

“I think that this election will be looked at by future historians as a time when the podcast culture and the digital culture determines what constitutes information that should be consumed,” says Jeffrey Dvorkin, a former news executive who served as NPR’s first ombudsman. “The challenge for mainstream media is to reaffirm their reliability. But too often, the public doesn’t care as much about that as perhaps it once did.”

For a generation reared on digital media, distinctions between types of news sources have eroded. In a Pew Research survey taken in September, young adults ages 18 to 29 are as likely to trust information from social media (52%) as they are to trust national news organizations (56%) for that. Among all adults, the gap was nearly 20 points, with far less trust in social media.

Trust in U.S. news media has been falling for decades, a point that Jeff Bezos, the billionaire founder of Amazon and owner of The Washington Post, made in an opinion piece defending his decision to nix candidate endorsements, which he said create “a perception of bias.” Mr. Bezos denied that the decision was guided by his business interests, saying there was no quid pro quo after a meeting last week between the CEO of his space-rocket company and former President Donald Trump, the GOP nominee. Critics say Mr. Bezos is trying to placate Mr. Trump, whom Amazon accused in 2019 of strongarming the Pentagon into denying it a cloud-computing contract in retaliation for the Post’s reporting on his administration. A lawsuit was dismissed in 2021.

“Most people believe the media is biased. Anyone who doesn’t see this is paying scant attention to reality, and those who fight reality lose,” Mr. Bezos wrote. He added, “Complaining is not a strategy. We must work harder to control what we can control to increase our credibility.”

“Trustworthy” media is a thing of the past

While trust in the news media has declined broadly since the 1970s, the biggest shift is on the political right. In 2000, 47% of Republicans had a “great deal” or “fair amount” of trust in the news media to report fairly and accurately, according to Gallup. By 2024, that share fell to 12%. Over the same period, the share of Democrats who trusted the media – just over half – was unchanged. Independents have tracked the decline among Republicans, though less precipitously.

Asking conservatives to assess news media is problematic in an era of hyperpartisan outlets, notes Diana Mutz, a professor of political science and communications at the University of Pennsylvania who runs multiyear panel surveys of voters. “The media is really not a single entity anymore,” she says. “If you ask [Republicans] if they trust their own media, they trust it more than ever. They see their own sources as highly reliable and trustworthy.”

Those sources, notably Fox News and rival right-wing broadcasters, are closely aligned with the politics of Mr. Trump, in ways that aren’t fully mirrored on the left, where mainstream news outlets, from network and cable TV to radio and national newspapers, are authoritative fonts of information for Democrats, as well as some independents and conservatives.

During the Trump presidency, this media consumption divide became a chasm as national news organizations sought to scrutinize his administration and its backsliding on democratic norms. In some cases, robust reporting was cheered by partisans as a form of resistance to Mr. Trump, who labels the news media “enemies of the people.”

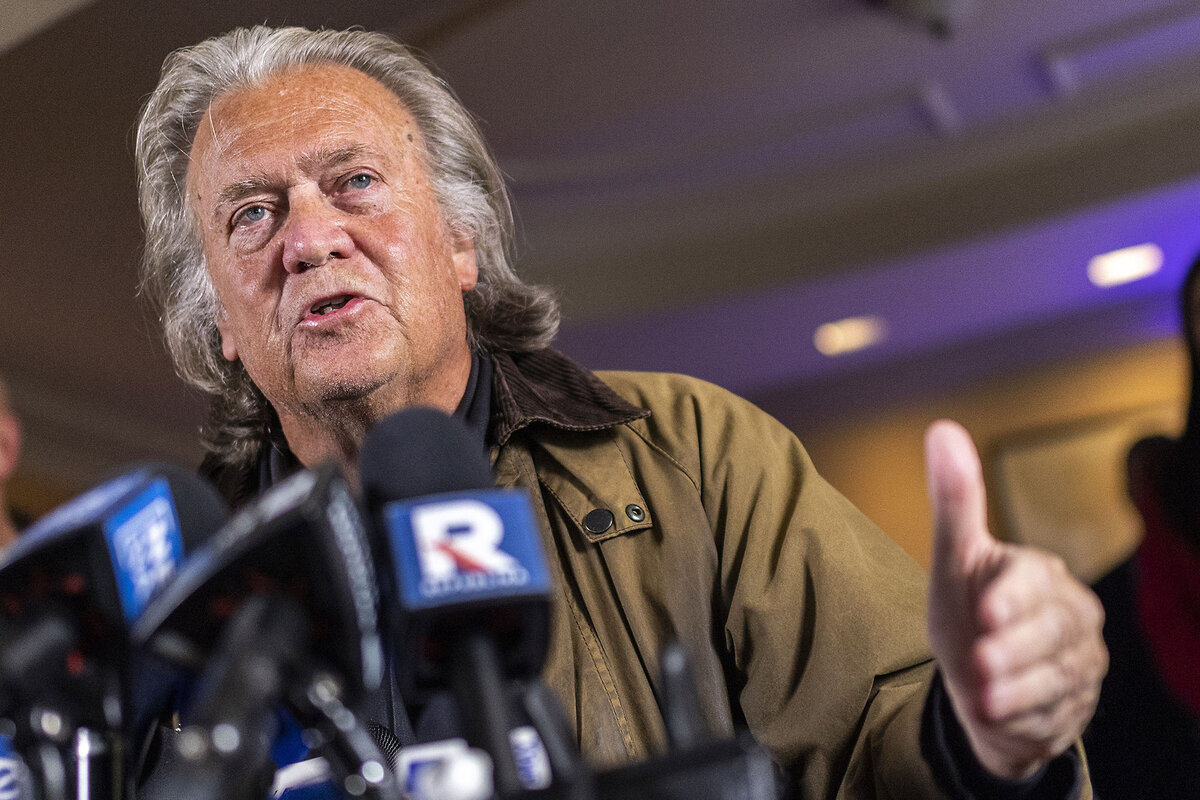

In 2018, Stephen Bannon, a former campaign strategist for Mr. Trump, framed this antagonism in stark terms. “The Democrats don’t matter,” Mr. Bannon told author Michael Lewis. “The real opposition is the media” and, he added, the way to deal with them is to “flood the zone” of digital media with junk content to disorient consumers and distract from fact-based reporting.

Mr. Bannon has since done just that as a right-wing media personality who also played a key role in Mr. Trump’s effort to reverse his 2020 election defeat. On Tuesday, he was released from a federal prison after serving four months for contempt of Congress over his defiance of a subpoena from investigators into the Jan. 6, 2021, riot at the Capitol.

Analysts say Mr. Bannon’s approach has become something of a playbook for right-wing partisans. Mr. Trump’s own Truth Social network is awash in conspiracies, falsehoods, and debunked rumors, often emanating from its owner. Similarly, Elon Musk, the owner of the social media platform X and a backer of Mr. Trump, has used the platform to spread misinformation about election fraud and other topics after dismantling verification teams that conservatives saw as biased against them.

Such unchecked misinformation makes it harder for the news media to sift fact from fiction and for the public to find reliable information, says Mr. Dvorkin, now a senior fellow at Massey College at the University of Toronto. The net effect on voters may be to lessen their faith in a messy democratic process, which depends on a shared set of facts. “At a time when it’s more difficult to get reliable and contextual information, people will move towards simple solutions,” he says.

Still, it’s unclear how persuasive the flood-the-zone strategy actually is in winning elections that hinge on a handful of swing states. The vast majority of voters don’t change their minds between presidential elections, says Professor Mutz, and the minority that do aren’t necessarily immersed in a cacophony of unreliable digital content.

“Most of the misinformation that’s out there is being promoted and consumed by people who aren’t going to change their vote anyway,” she says.

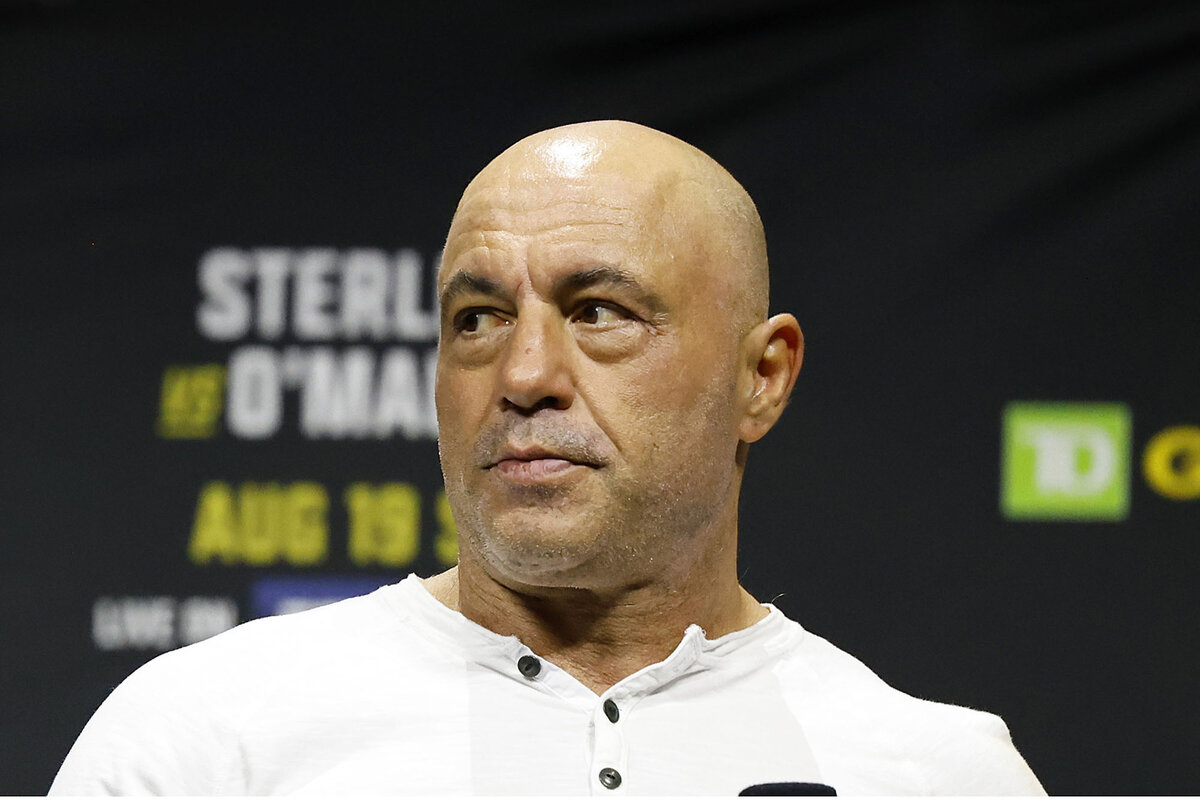

Male podcasters like Joe Rogan are the go-to GOP bullhorn

On the campaign trail, Mr. Trump has sought out podcasters like Joe Rogan and other male hosts, including comedians and sports aficionados popular with younger men, a demographic that Mr. Trump needs to turn out. Similarly Vice President Kamala Harris has appeared on podcasts such as “Call Her Daddy” and spoken to Charlamagne Tha God, a Black radio and podcast host.

Ms. Harris has also sat for interviews with national news media, whose requests Mr. Trump largely eschews. (One such interview with CBS News “60 Minutes” sparked controversy over the network’s editing of her remarks that appeared to flatter Ms. Harris.)

In a fragmented media landscape, getting the attention of voters who aren’t partisan news consumers is fraught, says Daniel Kreiss, a professor of political communication at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. “They’re not following this stuff on a regular basis, but they are consuming sports and lifestyle content more regularly,” he says. These voters “are the least attentive and therefore they’re the most open to changing their minds.”

This has made podcasters a campaign priority more so than national outlets that were once seen as essential for candidates.“The legacy media simply does not have the reach and influence that it once did, but no outlet does,” says Professor Kreiss.

The Post joins the editorial boards of the Los Angeles Times and USA Today in staying neutral in the 2024 race, after all three newspapers endorsed Joe Biden in 2020. (The Monitor does not endorse political candidates.) Analysts say that endorsements carry weight in state and local races where candidates are less familiar to voters, which isn’t the case in a presidential election. In 2016, Mr. Trump was opposed by almost all national and metropolitan newspaper editorial boards – and won.

What Mr. Trump did in that race and is doing now, says Professor Kreiss, is to communicate with voters in a way that cuts through a fragmented media landscape. He tells a consistent story “that drums out all the other noise. It’s always about these forces that are threatening white Americans, white Christian Americans, white rural Americans, that ‘us and them.’ It’s a clear, compelling story in a very clear moral universe. Who are the bad guys? Who are the good guys? Who’s doing this to you? … Everyone knows what that story is.”

Netflix doc takes a new look at the kiss that rattled Spanish women’s soccer

Just as the Spanish women’s national team was celebrating its 2023 World Cup victory, it found itself embroiled in a fight with the soccer federation president over an unwanted kiss. Netflix has just released a documentary looking at the scandal.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

The kiss changed everything.

It was August 2023 and the Spanish women’s soccer team was standing on the awards podium, basking in the glow of their first World Cup win. As cheers engulfed the stadium, Luis Rubiales, then-president of the Royal Spanish Football Federation, grabbed Jenni Hermoso, a forward, by the back of the head and forcibly kissed her on the lips.

Little did Ms. Hermoso or the rest of the team know that over the next days and weeks, that kiss would force a national dialogue about sexism, machismo, and sexual abuse in Spain.

Now, a new Netflix documentary, out Nov. 1, looks to tap into the culture of Spanish women’s football that led up to the kiss, and everything that came after it. “It’s All Over: The Kiss That Changed Spanish Football” is a story not just of players’ tenacity and passion to overcome the challenges that followed the infamous kiss, but their daily fight for equality and recognition in a male-dominated sport.

“Macho violence still affects female athletes in both explicit and more subtle forms,” says Susana Vazquez Cupeiro, a professor of gender studies. “A greater collective effort is necessary if we want to achieve equality.”

Netflix doc takes a new look at the kiss that rattled Spanish women’s soccer

The kiss changed everything.

It was August 2023 and the Spanish women’s soccer team was standing on the awards podium, basking in the glow of their first World Cup win.

As deafening cheers engulfed Accor Stadium in Australia, Luis Rubiales, then-president of the Royal Spanish Football Federation (RFEF), made his way through the line of players to offer his congratulations. When he got to forward Jenni Hermoso, he grabbed her by the back of the head and forcibly kissed her on the lips.

Little did Ms. Hermoso or the rest of the team know that over the next days and weeks, that kiss would not only threaten to mar their historic win but would spark Spain’s version of the #MeToo movement. Athletes, politicians, and celebrities came forward in support, shouting “se acabó” – it’s all over – and forced a national dialogue about sexism, machismo, and sexual abuse in Spanish football and broader society.

Now, a new Netflix documentary, out Nov. 1, looks to tap into the culture of Spanish women’s football that led up to the kiss, and everything that came after it. “It’s All Over: The Kiss That Changed Spanish Football” is a story not just of players’ tenacity and passion to overcome the challenges that followed the infamous kiss, but their daily fight for equality and recognition in a male-dominated sport.

“It’s All Over,” directed by Joanna Pardos, is a testament to the Spanish team’s resilience and its ability to rise up against adversity. And while viewers will certainly come away with a sense of euphoria about the success of this past year’s #SeAcabó social movement, women’s soccer continues to face setbacks and roadblocks to real change.

“We can’t deny that we’re in a process of social change, thanks to years of hard work and sacrifice by our female athletes,” says Susana Vazquez Cupeiro, a professor of gender studies at the Universidad Complutense de Madrid. “[But] macho violence still affects female athletes in both explicit and more subtle forms. ... A greater collective effort is necessary if we want to achieve equality.”

“We’d started a war”

Millions of people around the world saw Mr. Rubiales kiss Ms. Hermoso on the mouth. But the troubles for the Spanish team had begun brewing months before. So while “It’s All Over” begins focused on the fallout of the kiss, it makes an important flashback to when the real shift within the system began.

In September 2022, 15 players from the national team declared themselves unavailable for selection after their demands to oust coach Jorge Vilda went unanswered by the Spanish football federation. Though the players’ specific complaints about Mr. Vilda were not made public at the time, some later said that he routinely disregarded their privacy at team hotels.

By the time the World Cup came around less than a year later, eight of the 15 players had decided to come back, but tensions between the national team players and the federation were already high.

“We always seem to be asking for things that aren’t considered ours,” says national team defender Irene Paredes in the documentary.

“We realized we’d started a war,” goalkeeper Lola Gallardo goes on to say. “[The RFEF] was up here, and we were down there.”

There were times when many players felt they couldn’t win that war. Through text messages between players, personal testimonies, and media leaks by the RFEF, the documentary shows how Mr. Rubiales and his cohorts pitted players against one another in order to come out on top.

On Aug. 25, five days after the World Cup, Mr. Rubiales gave an impassioned speech to the football federation’s general assembly, where he hit out at “false feminism” and refused to resign. For the national team, it was too much. Midfielder Alexia Putellas took to the social platform X and published a post that would come to change women’s football: “This is unacceptable. It’s all over.”

National team members jumped on the moment, reposting it on their own social media platforms, and soon the message was being shared by Spanish athletes, celebrities, and even Spanish Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez. On Sept. 6, Ms. Hermoso filed a criminal complaint against Mr. Rubiales, and four days later, he resigned as RFEF president.

Small steps forward

Despite the Rubiales affair, Spanish women’s soccer continues to suffer from a lack of systemic change. Part of that stems from laws that some say don’t adequately protect players.

Spain has been a leader in Europe when it comes to legislation on sexual violence. A 2022 law required that women must explicitly give consent for sexual acts. But Mr. Rubiales was able to remain in his position for months after the kiss due to a holdover law from 1990, whose 2022 update has yet to be implemented.

“In Spain, we have lots of laws that show how feminist we are, but nothing is actually being put into practice,” says Mar Mas, the chairwoman of the Madrid-based Association for Women in Professional Sports. “When it comes down to it, the government is on the side of the football federation, so nothing changes. How do I feel? Frustrated.”

“It’s All Over” does suggest, however, that mindsets in Spain are starting to change when it comes to female athletes, if not to sexism more generally.

As the #SeAcabó movement took off, women across Spain spoke of the micromachismos they experienced in the workplace. And a November 2023 study by the Centro Investigaciones Sociológicas public research institute found that 96% of men surveyed thought gender equality was the key to a more fair society.

Still, Spanish soccer observers say the changes amount to baby steps. For the second year in a row on Monday, Barcelona midfielder Aitana Bonmatí was awarded the women’s Ballon d’Or, an international award that recognizes the sport’s best players each year. But only a handful of the players shortlisted for the award were present at the presentation ceremony due to it being scheduled at the same time as women’s international matches – a decision that critics say shows a lack of respect for the women’s game.

And when Jenni Hermoso was awarded the Sócrates humanitarian award at the same ceremony, for her stand against sexual violence and inequality in soccer, the host reportedly had to prompt the men in the room to follow the women in a standing ovation.

As the film comes to a close, there is a feeling that, when it comes to achieving equality in women’s football, the job is not over yet. Some members of the national team have spoken out about violence against women in sports at the United Nations, while others have joined sports unions to bring about change for the future. But there is a sense of strength in numbers.

“The fact that people from around the world came together to support me gave me a superpower to keep going,” says Ms. Hermoso in the film. “After everything we’ve been through, we’re still here.”

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

The delights of US democracy

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

For America’s Election Day on Nov. 5, a pizza parlor plans to celebrate democracy. Valentina’s Pizzeria in Madison, Alabama, will offer pies and boxes with images of the two presidential candidates, hoping to encourage customers to talk with one another.

“It’s a tense race and pizza is the comfort food of America. It brings everybody together,” owner Joe Carlucci told a local TV station. “No matter who wins this race we have to stand behind them good, bad, or indifferent, we have to come together as a country.”

Such events don’t make much news, but they do act as community-based counterpoints to the national dread expressed during the election. Nearly 4 in 5 Americans report anxiety because of the campaign. About a third say the idea of discussing politics has deterred them from attending a social event.

Yet pro-democracy activists say that encouraging fun events around elections is essential.

“Those of us who work in community engagement can either fan sparks of delight or extinguish them,” wrote Wendy Willis of the National Civic League. “As we see ourselves as stewards of democracy and stewards of delight, we can do both at the same time without missing a beat.”

The delights of US democracy

For America’s Election Day on Nov. 5, a pizza parlor plans to celebrate democracy. Valentina’s Pizzeria in Madison, Alabama, will offer pies and boxes with images of the two presidential candidates, hoping to encourage customers to talk with one another.

“It’s a tense race and pizza is the comfort food of America. It brings everybody together,” owner Joe Carlucci told a local TV station. “No matter who wins this race we have to stand behind them good, bad, or indifferent, we have to come together as a country.”

Also on Nov. 5, voters in Philadelphia heading to three polling stations will be invited to attend local festivals of art and music designed to depict the wonders of “the democratic process.” Voting day should “be a joyful celebration of our shared ability to shape the future,” said Lauren Cristella, head of a nonpartisan organization sponsoring the event.

In Traverse City, Michigan, meanwhile, residents attended a recent outdoor “celebration of democracy” that included a man dressed up as Uncle Sam. The festival served as a reminder of the resilience of the electoral system.

Such events don’t make much news, but they do act as community-based counterpoints to the national dread expressed during the election. Nearly 4 in 5 Americans report anxiety because of the campaign, according to a poll in August by LifeStance Health. About a third say the idea of discussing politics has deterred them from attending a social event.

Yet pro-democracy activists say that encouraging fun events around elections is essential.

“Those of us who work in community engagement can either fan sparks of delight or extinguish them,” wrote Wendy Willis of the National Civic League last year. “As we see ourselves as stewards of democracy and stewards of delight, we can do both at the same time without missing a beat.”

Around the world, people living in nondemocratic nations may be scratching their heads over the fact that so many Americans do not appreciate the strength of their democracy. That feeling is especially true during a super-cycle of elections. Nearly half of the world’s population is casting ballots in 2024, a record number. There is also a historic number of elections.

In countries that have recently restored or saved their democracies – from Senegal to Guatemala to Bangladesh – celebrating their triumphs comes naturally. One example is Moldova, which held a vote for president on Oct. 20 as well as a referendum on European Union membership.

“It was a celebration of democracy at the end of the day,” Mihai Popșoi, Moldovan deputy prime minister, told CNN. “Despite the Kremlin’s [vote-buying] assault on Moldovan democracy, our democracy has withstood, and it has shown the entire world what the will of the people is.”

In Washington, one celebration of democracy did take place, on Sept. 15, for International Day of Democracy. In a press statement, Antony Blinken, secretary of state, said, “We celebrate democracy as the single most powerful tool for unleashing human potential.”

That potentiality, presumably, includes building, protecting – and celebrating – democracy.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

A redeeming forgiveness

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Michelle Boccanfuso Nanouche

There’s an alternative to letting anger or resentment drive our lives: opening our hearts to God’s love, which redeems and heals.

A redeeming forgiveness

Forgiveness can be a game changer. Turned down for an apartment rental after mentioning my husband’s ethnic name, I broke down in tears of anger and disappointment. But my husband quickly forgave the offense, which enabled him to graciously reach out himself. The outcome of that conversation was an appointment for a showing – during which any prejudice fell completely away. We were warmly invited to make the apartment our home.

At first I marveled at his quick ability to forgive and move forward. But Christian Science has taught me that the capacity to forgive isn’t simply a good human quality that we may possess to varying degrees. Spiritually considered, it’s a God-gifted resource drawn from the infinite well of divine Love and reflected spiritually by each of God’s children.

The psalmist wrote, “Bless the Lord, O my soul, and forget not all his benefits: who forgiveth all thine iniquities; who healeth all thy diseases; who redeemeth thy life from destruction; who crowneth thee with lovingkindness and tender mercies” (Psalms 103:2-4). From the amplitude of God’s love flows to us the benefits of forgiveness, healing, and redemption of whatever would try to rob us of joy and progress. We are created by God to reflect – and to receive – His healing love and tender mercy in any and every case.

And yet, forgiveness can sometimes seem out of reach. The psalmist’s counsel to “forget not all his benefits” can remind us that God, divine Love, is the unchanging Redeemer of any circumstance. Divine Love loves as the sun shines – fully and equally on all. Recognizing God as the source of all good and right desires, motives, and actions, we find capacities for forgiveness that we might otherwise miss. Then incidents that produced anger and hurt become occasions to draw on the deep, healing resources of Love.

This isn’t to say that we disregard an injustice or other wrong. Rather, it provides a spiritual basis for empowering us – and others – to think and act more consistently with our nature as the reflection of infinite Love.

The founder of Christian Science, Mary Baker Eddy, wrote, “Jesus aided in reconciling man to God by giving man a truer sense of Love, the divine Principle of Jesus’ teachings, and this truer sense of Love redeems man from the law of matter, sin, and death by the law of Spirit, – the law of divine Love” (“Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” p. 19).

Jesus understood that genuine love isn’t scanty or given out to some and not others. He proved that God, Love, is the very substance and source of what we are as God’s children. From divine Love flows the power of Christ – the power that overrules resistance to healing and to correcting human errors through love and forgiveness. No case is too hard for Christ-love to redeem and heal. Nothing can move us beyond the healing and redeeming reach of the ever-present, all-powerful divine Principle, Love.

For a long time I held on to a hurt that seemed unforgivable. Then, while praying one day, I caught a glimpse of what it means to be the reflection of Love. I felt such a closeness to our Maker, God. I realized I could consign anything to divine Love. I could relinquish my fears and doubts and let the healing Christ replace them with an openness to forgiving.

Forgiveness suddenly felt completely possible to me – no longer contingent on the past behavior of others, but more about redeeming myself through Love. I could see that the same Christ message that was coming to me, releasing me from anger and hurt, comes to us all to redeem us from whatever would undermine harmony. And I forgave with a deep and unforgettably healing forgiveness.

There is a scriptural passage that has become a go-to reminder to me of our instant access to the blessing of Christ-impelled forgiveness: “The Lord his God be with him, and let him go up” (II Chronicles 36:23). No one is beyond the healing reach of God’s love. We can give up hurt, betrayal, annoyance, anger – whatever would seem to hinder that healing forgiveness – for the universal love of God, at any moment. Nothing can block the endless flow of divine good that empowers us to know the freedom of Christly forgiveness.

Viewfinder

The power of many hands

A look ahead

Thank you for coming along with us this week. As you might imagine, we have a trove of stories lined up for next week, including coverage of the U.S. presidential election – from swing states to vote counting. We’ll also look at the trajectory of Hezbollah, with evidence that faith in the organization is waning in some quarters.