- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 8 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- Election Day 2024: Why both sides feel this is a tipping point for America

- Today’s news briefs

- What happens if Trump tries to overturn another election loss?

- It’s a ‘law and order’ election in Georgia – with a twist

- At war with Israel, Hezbollah takes fire from underwhelmed supporters

- Transformed playgrounds, and a bridge between art and science

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

How we’ll cover Tuesday’s elections

Mark Sappenfield

Mark Sappenfield

On Tuesday, we will cover the U.S. elections a little differently. We expect huge demand for information, as well as a desire for sources that won’t incite, frighten, or put a thumb on the partisan scale. So we will put a significant amount of our effort into live updates, which will be calm, insightful, short takes on key news with important analysis or context.

The link to the live updates page will be on our homepage. Just come to CSMonitor.com on Tuesday to find it. We’d appreciate your feedback on the idea and the execution. Please email me at editor@csmonitor.com.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Election Day 2024: Why both sides feel this is a tipping point for America

Amid unusually high concern about this election, many voters don’t recognize that people on the other side are also deeply worried. And that may be part of the problem.

-

Caitlin Babcock Staff writer

Lauren Markow lived through the Cold War with a bomb shelter at her St. Louis home. Yet to her, it feels like America is at a dangerous new tipping point with former President Donald Trump on the verge of reelection.

Meanwhile, Hillsdale College sophomore Cole Sutherland has been feeling a sense of “doom” about the possibility of Vice President Kamala Harris winning this presidential election, the first in which he is old enough to vote.

Ms. Markow and Mr. Sutherland represent opposite poles in Middle America. But both say it’s important to seek common ground – including a shared love of country.

So we invited the two to speak over Zoom.

On Sunday afternoon, they talked through their fears for the country’s future. Before they logged off, Ms. Markow shared a parting quote.

“Given how scholarly you are about these things, I think you might appreciate this,” she told Mr. Sutherland.

Near the end of the Civil War, Abraham Lincoln was asked if he had ever doubted that the Union would prevail. He responded in the words of his secretary of state, William Seward: “‘There was always just enough virtue in this republic to save it; sometimes none to spare.’”

Election Day 2024: Why both sides feel this is a tipping point for America

Lauren Markow lived through the Cold War and the turbulent 1960s, yet to her it feels like America is at a dangerous new tipping point.

She teared up thinking about it the other day as she sped past brilliant fall foliage headed west from St. Louis, away from the suburb where she grew up with a bomb shelter at home – and toward an election that looms ever larger in her thought. Not only because of what it means for her as a Democrat desperate to restore civility and worried that former President Donald Trump could be more unrestrained in a second term, but also because of the children in her life.

“If Trump gets elected and he does the things he says he wants to do, my 10-year-old friends will never know what this country really can be on better days,” she says. “This country was an exquisite and stunning idea.”

Meanwhile, seven hours to the northeast in Michigan, college sophomore Cole Sutherland has been feeling a sense of “doom” about the possibility of Vice President Kamala Harris winning this presidential election, the first in which he is old enough to vote. Among other concerns, he sees her and her allies as disregarding guardrails that the Founding Fathers carefully put in place.

“They wanted a place for the people, but they didn’t want direct democracy because that ends up being mob rule, in which one party gets crushed,” says Mr. Sutherland, adding that the founders instead envisioned a representative republic.

“I think that’s in one of the Federalist papers,” he adds. “Hang on, I have it. ... It’s in Federalist 10.” Within seconds he pulls up James Madison’s treatise on how to strike a balance between majority rule and minority rights, which he recently wrote a paper on for one of his classes at Hillsdale College, ranked third by The Princeton Review for “most conservative students.”

In Mr. Sutherland’s view, Democrats are misusing and weaponizing the term “democracy” under the guise of preserving it. Such rhetoric, he says, “represents a moving away from the American founding that is very dangerous for the country.” For example, he mentions the growing push to eliminate the Electoral College, and instead let the popular vote determine presidential elections.

Ms. Markow and Mr. Sutherland are multidimensional people, and shouldn’t be seen as simplistic proxies for Democrats and Republicans. But they are two of millions of Americans facing an election that, to many, feels existential.

It’s not uncommon for politicians to use such rhetoric in their campaigns. President Joe Biden, whose 2020 campaign focused on a message of unity, earlier this year called GOP nominee and former President Trump “the one existential threat.” And Trump ally Steve Bannon in June cast this election as coming down to “victory or death,” asking supporters, “Are you prepared to leave it all on the battlefield?”

But what is different this year is that nearly 2 in 3 Americans now feel as if the election will “make a great deal of difference” in their life – the highest level registered in NBC News polling over the past few decades, and triple the level in 1996.

Voters like Ms. Markow and Mr. Sutherland are making their decision against a backdrop of fear and division, heightened for many by news coverage that can focus on certain issues and perspectives to the exclusion of others. The proliferation of misinformation has further skewed perceptions. If people think the country will end as they know it if their side loses, that could cause worsening divides – or potentially lead to political violence.

With humanity on the brink of massive change due to the rise of artificial intelligence, Ms. Markow worries the United States is devolving into toxic political brinkmanship that is undercutting its leadership in the world. She is also concerned that it is eliminating the spaces in American society for the kind of collaborative thinking needed to find urgent solutions.

“I’ve been saying this for the past couple of years: Stop treating the country like a trophy at a sporting event,” says Ms. Markow. “Can we please agree that the country is very vulnerable, in a place of real danger, and we all need to be on the same side?”

Even as Ms. Markow and Mr. Sutherland represent opposite poles in Middle America, however, both say it’s important to look for common ground – including a shared love of country.

Key influences, from a housekeeper to COVID-19 “groupthink”

She’s a student of Tai Chi. He’s a devout Baptist.

Ms. Markow was raised in a wealthy Jewish family, with a father who worked long hours as a surgeon, a mother who often struggled with depression, and an African American housekeeper who significantly shaped her worldview.

Her housekeeper’s understated wisdom and lived experience – such as the time she had to stay in separate hotels on a family road trip – opened young Lauren’s eyes to new perspectives. She says her father’s racism and the sometimes toxic environment in her home also introduced her early to the challenge of navigating tense spaces.

“I would break tension and redirect things,” she says. “I learned how to listen respectfully and disagree respectfully.”

Ms. Markow has sought to practice such active listening throughout her adult life, including through an informal Lunch With a Liberal initiative she started in 2016 to hear out Trump supporters over a sandwich.

Her own experience is a lesson against simplistic labels: She’s a cultural Jew drawn to Buddhism; an abortion-rights proponent who urges some limits around terminating a pregnancy; a critic of war and of Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, but also of some pro-Palestinian protesters who don’t recognize the intolerance of Hamas toward people like her gay son.

Mr. Sutherland came of age during the pandemic, in which what he saw as groupthink led him to question the prevailing views in his left-leaning high school in Louisville, Kentucky. One example was people labeling the possibility that a lab leak sparked the initial COVID-19 outbreak as a “conspiracy theory,” without examining relevant evidence. He also came to distrust the mainstream media.

Through this period of self-examination, Mr. Sutherland went from someone who had mostly found himself in line with his school’s political atmosphere to someone who was kicked out of class for challenging a teacher’s position supporting abortion rights.

He started attending his Baptist church more regularly, during which his view of what it means to love your neighbor evolved from accepting everything people do to recognizing that sometimes it’s more loving to point people to a better way. He takes issue, however, with the “fire and brimstone” approach of many right-wing Evangelicals. The key, he says, is to “live your life in a way that honors and reflects Christ,” which he says can open people’s hearts.

He declined to take part in a school walkout over a statewide “Don’t say gay” bill, a label he describes as a “gross mischaracterization” of the legislation. Several students approached him privately and told him they didn’t feel comfortable doing the walkout either, but didn’t want to stand out. He sees the same problem in society as a whole.

“How badly have we failed if people are just participating in things to go along with the crowd?” he asks.

Concerns about democracy

Ms. Markow sees that happening in the GOP, and describes the Republican Party as having been taken hostage by Trumpism. She describes an “almost hypnotic sway,” causing people to identify with something they would normally oppose – and then being in denial about it. For example, top Republicans criticized Mr. Trump for his role in inciting the Jan. 6, 2021, attack on the U.S. Capitol, but then quickly backpedaled.

“It’s like national Stockholm syndrome,” she says.

Mr. Sutherland is not Mr. Trump’s biggest fan, though he plans to vote for him as a better alternative than Ms. Harris. But he sees Democrats’ characterization of Mr. Trump as a threat to democracy as a disingenuous way to marginalize the opposition and thwart robust debate – not just about the structure of American government, but about any issue.

One of his politics professors at Hillsdale calls this the “democratic incantation.”

“The word ‘democracy’ – it’s been made something sacred,” says Mr. Sutherland.

Ms. Harris and even some former Trump administration officials have criticized Mr. Trump as having autocratic impulses, and predict he would test constitutional limits on power far more in a second term than he did in a first term. They point to his refusal to say he would accept a defeat in 2024; his plans to gut the civil service, installing political appointees in positions meant to be held by nonpartisan experts; and his recent rally at Madison Square Garden that led critics to draw parallels with a pro-Nazi gathering in the same location in 1939.

But Mr. Sutherland takes issue with what he calls “‘Trump is literally Hitler’ rhetoric.” He says Ms. Harris is falsely demonizing virtually half the country as supporters of fascism.

That, he says, is “a huge threat to the country.”

One thing they agree on: the need for civility

Ms. Markow is concerned that a hardening of views is eroding the elasticity that enables democracy to survive times of tumult. A key part of this in her view is the decline in civility in the Trump era.

“No matter how much you agree with his policies, I feel like we’ve lowered the bar so far on civility that even a scorpion couldn’t limbo under it,” she says.

Mr. Sutherland also sees value in having respectful conversations with those who hold opposite views.

So we invited the two to speak over Zoom.

On Sunday afternoon, two days before the election, they talked through their fears for the country’s future – Mr. Sutherland in his dorm room following a busy week of midterms and Ms. Markow in her home office coming off a Tai Chi retreat.

They probed each other’s views on everything from abortion to immigration, pushing back at times. But they also agreed that the country needs to be preserved for the next generation. And they held out hope – in part because of citizens willing to have conversations like this – that it would be.

“It’ll be there after us; it was there before us,” said Mr. Sutherland, sporting a red Louisville sweatshirt.

After more than 75 minutes, they exchanged emails to continue the conversation. Before they logged off, Ms. Markow shared a parting quote.

“Given how scholarly you are about these things, I think you might appreciate this,” she told Mr. Sutherland.

Then she read him a line that President Abraham Lincoln, when asked if he had ever doubted that the Union would prevail in the Civil War, quoted and attributed to his secretary of state, William Seward: “‘There was always just enough virtue in this republic to save it; sometimes none to spare.’”

Today’s news briefs

• Breonna Taylor case: A federal jury convicts a former Kentucky detective of using excessive force on Breonna Taylor the night she was shot by police officers in 2020.

• U.K. border security: British Prime Minister Keir Starmer says he will double funding for Britain’s border security agency and treat people-smuggling gangs like terror networks, part of efforts to stop migrants crossing the English Channel in small boats.

• Nvidia replaces Intel: Nvidia is replacing Intel on the Dow Jones Industrial Average, ending a 25-year run for a pioneering semiconductor company that has fallen behind as Nvidia cornered the market for chips that run artificial intelligence systems.

What happens if Trump tries to overturn another election loss?

Since former President Donald Trump’s extralegal efforts to overturn his 2020 defeat, the system has been strengthened in a variety of ways. But a narrow victory by Vice President Kamala Harris could still lead to a drawn-out battle.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 8 Min. )

Former U.S. President Donald Trump has been signaling that he is highly likely to challenge the election results should he lose on Tuesday. The big question is what may happen next.

Mr. Trump never conceded his 2020 loss, and his extralegal attempts to overturn that election culminated in the Jan. 6, 2021, U.S. Capitol riot. In this campaign, he is again making misleading claims that the vote is being rigged against him.

His team has been preparing for this moment for four years, installing allies on county election boards and training thousands of volunteers to watch for potential fraud.

Vice President Kamala Harris’ campaign is also gearing up for a postelection battle. Ms. Harris told ABC News that her team was “sadly ready” to respond should Mr. Trump try to overturn the results.

Yet while postelection chaos is possible, 2024 is unlikely to be a replay of 2020. The system has been strengthened: Congress passed legislation making clear that elected officials cannot reject the will of the voters. And states and localities have worked assiduously to harden the voting process against attacks. Mr. Trump also doesn’t have control over the military or Justice Department this time around, and it will be Vice President Harris, not Vice President Mike Pence, presiding over the Electoral College count in Congress.

What happens if Trump tries to overturn another election loss?

In speeches, social media posts, and interviews, former U.S. President Donald Trump has been signaling that he is highly likely to challenge the election results should he lose on Tuesday. The big question is what may happen next.

Mr. Trump never conceded his 2020 loss, and his extralegal attempts to overturn that election culminated in the Jan. 6, 2021, U.S. Capitol riot. In this campaign, he has again refused to say he’ll accept the results if he comes up short, and is already making misleading claims that the vote is being rigged against him.

“They’re going to cheat. They cheat. That’s all they want to do is cheat,” Mr. Trump said at a Wisconsin rally in early October. “It’s the only way they’re going to win.”

Mr. Trump’s team has been preparing for this moment for four years, organizing on the ground and installing allies on county election boards. The Republican National Committee has invested heavily in “election integrity” efforts, training thousands of volunteers to watch for potential fraud. Trump-aligned groups have proliferated across the United States to challenge election results, including a network organized by Cleta Mitchell, who worked with Mr. Trump to try to overturn his 2020 loss. Lawsuits are being filed at a historically high rate, with more legal wrangling a near-certainty. There have already been isolated incidents of campaign-related violence, intimidation, and ballot sabotage.

Vice President Kamala Harris’ campaign is also gearing up for a postelection battle. Ms. Harris told ABC News that her team was “sadly ready” to respond should Mr. Trump try to overturn the results.

Yet while postelection chaos is quite possible, 2024 is unlikely to be an exact replay of 2020. In important ways, the system has been strengthened: Congress passed legislation making clear that elected officials cannot reject the will of the voters. And states and localities have worked assiduously to harden the voting process against potential attacks. Mr. Trump also doesn’t have control over the military or the Justice Department this time around, and it will be Vice President Harris, not Vice President Mike Pence, presiding over the next Electoral College count in Congress.

If the election is close, we’ll likely see “lots of litigation,” as well as “various efforts to challenge the legitimacy of the outcome,” says Rick Pildes, a constitutional law professor at New York University. Still, he adds, “I think there are many institutional, legal, and even political safeguards in place that should ensure that the lawful winner of the election actually becomes president.”

What’s changed since 2020

Many Americans expect Mr. Trump to reject an election loss. Two-thirds of swing-state voters in a Washington Post poll released last week said they doubt the former president will accept the result if he loses this election – including more than one-third of those who plan to vote for him. A majority of swing-state voters, 57%, also said they feared Mr. Trump’s supporters would respond to a loss with violence.

Mr. Trump set off alarm bells among Democrats recently when he declared that he and House Speaker Mike Johnson had a “little secret” that could help him win – a comment many took as a hint the House might try to overturn a Harris win. Mr. Johnson said the next day that the secret was simply “one of our tactics on get-out-the-vote,” not anything “diabolical.”

Even if House Republicans wanted to, though, it’s unlikely they could block a legitimate win by Ms. Harris, thanks to a new law Congress passed in 2022. The Electoral Count Reform Act (ECRA) made clear that the “alternate elector” legal theory cited by Mr. Trump’s allies to try to overturn his loss in 2020 – appointing rogue slates of Electoral College electors who would back him over Joe Biden – would be a legal no-go in future elections. It would take majorities in both chambers of Congress to reject the law’s strictures on certification – and many Senate Republicans who backed the law will still be in office on Jan. 6, 2025, making that an unlikely outcome.

“The good news is that ECRA is a really big improvement,” says Ned Foley, a constitutional and election law expert at the Ohio State University who advised Senate negotiators who crafted the law. “The whole approach of ECRA is to basically say that the rule of law controls the outcome, and that politicians can’t subvert the outcome just because they don’t like it.”

Democrats and Republicans who have stood up to Mr. Trump currently hold the governorships and secretary of state offices in nearly every swing state – many having defeated candidates Mr. Trump endorsed in the 2022 midterms. That means the officials who are supervising the elections and who will ultimately certify the statewide results are unlikely to side with Mr. Trump if he tries to subvert the law.

The biggest risk may come if county officials refuse to certify their results. Trump supporters have attempted this in other elections in recent months, arguing that the votes had problems in their view and should be tossed out. But ECRA as well as many state laws have underscored that the certification of election results isn’t at the discretion of local officials. They would likely face judicial orders to certify, or face real legal penalties – a strong motivator, though no guarantee.

Georgia Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger, one of the Republican officials who resisted Mr. Trump’s demands to overturn their state’s results in 2020, told the Monitor in late September that county officials would be forced to follow the law and certify their results, whichever candidate benefited.

“At the end of the day, state law is very clear, and that cannot be violated. All elections must be certified,” he said. “That’s black-letter law, and everyone has to follow state law.”

A 2023 U.S. Supreme Court ruling also rejected a Republican-pushed “independent state legislature” legal theory that would have given dramatically more power to state legislatures to set rules for federal elections. That decision lowered the chances that GOP-controlled state legislatures could successfully overturn the will of the voters should Ms. Harris win in their state.

History rhyming, not repeating itself

But while there are more safeguards around the election process than in 2020, a more fraught situation could still develop if the margin of victory is narrower.

The 2020 election wasn’t actually that close. All but one of the swing states went for Mr. Biden, who ultimately got 306 electoral votes, far more than the 270 needed for victory. That meant Mr. Trump needed not just one but several states to overturn their results, and his potential allies in any given state weren’t guaranteed success even if they went along with his efforts.

No individual state was close enough to give a legal challenge much of a chance, either. Recounts and court fights can swing election results, but it’s almost unheard of for a state’s results to change if the margin of victory is more than around 1,000 votes. The narrowest margin in 2020 was in Arizona, which went for Mr. Biden by just over 10,000 votes.

A closer vote count, however, could lead to a drawn-out court battle. The 2000 election, which came down to just 537 votes in Florida, was fought in the courts and ultimately settled in a controversial decision by the U.S. Supreme Court.

This year, it’s clear both sides are particularly ready for a courtroom brawl. Dozens of legal battles are already underway:

- On Saturday, Trump’s team filed a lawsuit falsely claiming that several Georgia counties were breaking the law by letting voters drop off ballots – only to have a judge immediately rule against it.

- Friday evening, the U.S. Supreme Court dismissed a request from Republicans to overturn a Pennsylvania Supreme Court ruling allowing voters who messed up their mail ballots to be able to cast provisional ballots on Election Day.

- The Trump campaign sued after officials in Bucks County, Pennsylvania, closed in-person absentee voting too early; a judge extended the deadline as a result.

- Democrats are currently suing in Erie County, Pennsylvania, over mail ballot delays.

- Republicans have lost last-minute suits in multiple states seeking to tighten rules around military and overseas ballots.

While the conservative-dominated U.S. Supreme Court rejected a number of last-ditch attempts to overturn Mr. Trump’s loss in 2020, that doesn’t mean they’d do so again in different circumstances.

Democrats and voting rights advocates were alarmed last week, when the high court’s conservatives ruled that Virginia could restart a purge of 1,600 voter registrations suspected of being noncitizens. The court overturned a unanimous lower court decision that had blocked the effort because it fell in the 90-day preelection “quiet period” in which federal law prohibits removing voters from the rolls – and because multiple U.S. citizens were found to have been erroneously flagged for removal.

Democrats also worry about what the court might do if Republican-controlled state legislatures decide to throw out narrow wins by Ms. Harris and instead send alternate elector slates to Congress, something Mr. Trump tried and failed to get them to do four years ago. That is now prohibited under ECRA – but that brand-new law hasn’t been tested in court.

Isolated incidents of sabotage, disruption

For all the chaos of the 2020 postelection period, Election Day itself went off fairly smoothly. This year, while early voting has been mostly trouble-free, there have been a handful of alarming, if isolated, incidents of illegal election disruption.

In Oregon and Washington, someone set fire to a pair of ballot drop boxes, destroying hundreds of ballots (footage obtained by police shows the same car at both sites). In a separate, earlier incident, someone set fire to the contents of a mailbox in Arizona, damaging a handful of ballots.

In Florida, police arrested an 18-year-old Trump supporter for brandishing a machete at a polling location last week. More than a dozen other cases of election-related violence, intimidation, and sabotage have been identified in recent weeks.

The FBI and Department of Homeland Security warned in a bulletin sent to state officials earlier this month that “election-related grievances” could motivate people to “engage in violence, as we saw during the 2020 election cycle.”

“It does appear as if the Trump campaign and his allies right now are spending more time trying to create a false myth of the inevitability of his victory,” says David Becker, a former Justice Department official who runs the nonpartisan Center for Election Innovation and Research. “I’m worried about how that could be leveraged postelection, should Trump lose, to create a sense of shock and anger that could result in violence postelection.”

It’s a ‘law and order’ election in Georgia – with a twist

Many Americans say they’re concerned about law and order. That often favors Republicans, but voters in the swing state of Georgia show how the issue has extra complexities this year.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

As golf carts meander through a leafy lakeside park, Steve Arnold has to acknowledge an obvious truth to his cozy middle-class existence: “Yeah, we’re in a bubble here.”

On paper, Peachtree City, Georgia, is an American safe space.

About 20 miles southwest of Atlanta, the crime rate here is far below the national average.

But beneath the idyllic surface of this Atlanta suburb lie concerns about public safety. “Law and order is the key issue,” says Mr. Arnold. He and his wife, Tammy, are voting Republican, citing concerns about illegal immigration for one thing.

Often public order is an issue that benefits Republican candidates. But this historic election also features a Republican former president who’s been convicted in criminal court, running against a Democratic former prosecutor whom critics accuse of being soft on illegal immigration and other crimes.

The election’s protagonists point to a broader complexity, as Americans grapple with concerns about safety and stability, as well as with questions about corruption and the fairness of the criminal justice system.

“We may feel safe here, but this election in many ways is about whether we feel safe as a country, and who we trust to keep us safe,” Ms. Arnold says.

It’s a ‘law and order’ election in Georgia – with a twist

As golf carts meander through a leafy lakeside park, Steve Arnold has to acknowledge an obvious truth to his cozy middle-class existence: “Yeah, we’re in a bubble here.”

On paper, Peachtree City, Georgia, is an American safe space.

About 20 miles southwest of Atlanta, the planned community has long been a harbor for airport workers and now sprawls with golf courses and over 100 miles of cart paths.

The crime rate here is far below the national average. Teens arrested for breaking into a smoke shop was a top local story this fall.

But beneath the idyllic surface of this Atlanta suburb lie concerns about public safety. Mr. Arnold recalls a recent scene where parents felt the need to surround a group of young, female volleyball players during a tournament trip to a nearby town to protect them from leering groups of what appeared, to him, to be Central American immigrants.

“Law and order is the key issue – everything hinges on that,” says Mr. Arnold, a mortgage broker. “You can’t have open borders and feel safe anywhere. Crime comes to you.”

Mr. Arnold has deeper concerns, too, about the state of criminal justice. Are political elites using the power of the state to pick winners and losers, including the presidency? “If power means everything and rights nothing, what kind of country is there to inherit?” says his wife Tammy, a voter, like him, for former President Donald Trump.

Other voters in Peachtree City flip that coin: How can anyone be safe if criminality comes from the top?

“If we have a leader who eschews the Constitution itself, well, at the end of the day, none of us are free,” says Lana Bates, a lifelong Republican who just voted for Democrat Kamala Harris.

For those reasons and more, law and order is a major issue for many Georgia voters, who could swing the election.

Public concerns about disorder often deliver ballot-box gains to the Republican Party, with its promises of stability and tough-on-crime policies. But this year there’s also an unusual plot twist. This historic election features a Republican former president who’s been convicted in criminal court, running against a Democratic former prosecutor whom critics accuse of being soft on illegal immigration and other crimes.

These election protagonists point to a broader complexity, as Americans grapple with concerns about safety and stability, as well as questions about corruption and the fairness of the criminal justice system.

“We may feel safe here, but this election in many ways is about whether we feel safe as a country, and who we trust to keep us safe,” Ms. Arnold says.

Personal safety as an election theme

The economy is key for most voters in Georgia, says University of Georgia pollster Trey Hood.

But a sense of personal safety, he says, remains a theme – and many voters see their own concerns reflected in the presidential candidates’ aspirations and philosophies.

Violent crime rose after the pandemic, but has come down nationally since then, including in Georgia. Nevertheless, about 35% of U.S. voters say that crime is “extremely important” to their vote, with Republicans more likely to say that. For many, the sharp spike in illegal immigration during the first few years of the Biden administration is inextricably tied to a sense of disorder and concerns about crime.

Both Republicans and Democrats see it as very important to maintain public respect for police. Both support protecting the rights of those accused of crimes, yet both are also more likely to say the justice system is “not tough enough” rather than “too tough” on criminals.

Complicating this public consensus is the reality of a criminal justice system that jails 1.2 million people – more, per capita, than any other democratic nation. Research based on 2010 data found that roughly 1 in 12 Americans has a felony conviction.

Thanks to new laws, about 2 million former felons have now had their voting rights restored.

It is not a constituency either party can cleanly claim. While Mr. Trump lambasted Harris running mate Tim Walz for reinstating voting rights for ex-prisoners in Minnesota, a new Marshall Project survey found that a majority of incarcerated Americans would vote for Mr. Trump, in part because they feel he has been, like them, unjustly prosecuted.

For the campaigns, the ideas around crime become as simple as a Peachtree City yard sign: “Trump = Safety; Kamala = Crime.” For her part, Ms. Harris has framed the race as a choice between a prosecutor and a felon.

Both aspirants are trying to reach an American middle class concerned about crime but also about the capacity of the criminal justice system to address deeper social problems.

“We have to look at root causes of crime instead of just throwing everyone in a box,” says Sharhonda Hickman, a Harris voter in Savannah.

Americans generally want tougher law enforcement, but by a roughly 2-to-1 margin they think addressing social problems should be the higher priority as a way to reduce crime, polling by Gallup finds.

At the same time, more Americans are keeping guns in their homes for safety, more are worried about being a victim of a hate crime, and more say the criminal justice system isn’t fair.

“The hard versus soft characterization [of crime fighting] is one that we have lived with for decades, but I don’t know what that means for felony disenfranchisement, what to do about prison conditions, or what to do about gun control and where responsibility lies when teenagers get a hold of them and shoot up their schools,” says William Howell, coauthor of “Presidents, Populism and the Crisis of Democracy.”

Still, as he sees it “there really are deals to be made that conform with what broad segments of the American public would actually support.”

Those trends in some cases can be surprising.

Here in Republican-led Georgia, gun rights have been ascendant as in many other states as more and more Americans – including Ms. Harris – see personal weapons as safety necessities. But after a mass shooting by a 14-year-old in Apalachee County, prosecutors brought charges against the father as a way to reframe responsibility around gun ownership. A state committee is looking into stricter gun storage laws.

The U.S. Attorney’s office in Atlanta just released a scathing report on the state of Georgia prisons, which many see as a first step to improving conditions in a state that ranks fourth nationally in numbers of imprisoned people.

Georgia has long made it difficult to expunge felony charges, making it hard for affected people to find work. But in 2021, Georgia’s Republican legislature passed the Second Chance Act that allows nonviolent offenders to have their records expunged once they’ve completed their sentence.

“Allowing those who go to prison to come out as citizens ... is something that stops that revolving door [of recidivism],” says Chad Posick, a criminologist at Georgia Southern University, in Statesboro. “That’s now a bipartisan point.”

Seeking solutions – and respect for the law

Questions of crime, justice, and public order run through the election from right-leaning Fayette County, where the Arnolds live in Peachtree City, to largely Democratic Chatham County, anchored by Georgia’s historic port city of Savannah some 200 miles away.

For local fisherman Andy Greene, crime stood at the top of his list of priorities as he voted for Ms. Harris. But, even though Savannah has seen a jump in murders this year, his choice didn’t relate to concern about shootings.

“If we elect a criminal to be president, we’re sending a very powerful message that the law doesn’t matter,” says Mr. Greene, noting Mr. Trump’s felony convictions for falsifying business records in New York. “You can already see it in the way boaters with Trump flags fly through no-wake zones. It’s basically, ‘I can do what I want, the hell with the law.’”

To some here, the most important answers to crime won’t come at the voting booth.

“Crime is on my radar, but in my view there are limits to what politicians can do about crime,” says Blake Schenerlein, from Savannah, who has already voted. “Communities have to step up, too.”

This summer, Savannah sponsored a Stronger Together initiative that asked residents to take a larger role in addressing crime. Tougher policing here includes a new law targeting gun owners, making it a misdemeanor crime to leave a weapon in an unlocked car.

Professor Posick, the criminologist, sees signs of a public seeking practical solutions.

“You have fringe people who say, ‘Abolish prisons,’ or ‘Lock everybody up,’ but the majority of people are saying, ‘We can’t do either one of those exclusively, right?’ We’re seeing that play out in real time,” he says. When the result is a search for effective policies, “regardless of political orientation, that’s an interesting dynamic.”

At war with Israel, Hezbollah takes fire from underwhelmed supporters

For years, Hezbollah confidently assured its Shiite Lebanese base that when the time came, it would robustly defend Lebanon and punish Israel. Now, amid another destructive war, many supporters are losing faith. Can it win them back?

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

With Hezbollah and Israel locked in another punishing war, disappointment and anger echoes increasingly across Lebanon’s Shiite community, which has borne the brunt of thousands of Israeli airstrikes. Across southern Lebanon, entire villages have been destroyed.

In 2006, in a conflict widely attributed to Hezbollah’s own miscalculation, a Hezbollah supporter who gives the name Hussein lost 16 members of his family in an Israeli airstrike. Yet his personal loss only increased his support for Hezbollah’s “resistance” as a way to achieve revenge.

But fast-forward 18 years, and Hussein, among many traditional Hezbollah supporters, expresses doubts about its decision to launch rocket attacks, for more than a year, against northern Israel in solidarity with Hamas.

“We feel that everything is happening for no reason, for nothing,” says Hussein. “They are saying they have surprises, but we are waiting to see. ... We lost our jobs, our work – it’s a disaster.”

Recent more effective Hezbollah strikes have won praise, and include a mid-October drone strike that killed four Israeli soldiers and wounded 67.

“People are seeing this; people are happy,” says Hussein. “But it’s not done; it is taking a long time,” he adds. “The result of this war will be so important to the future of Hezbollah.”

At war with Israel, Hezbollah takes fire from underwhelmed supporters

With Hezbollah and Israel locked in another punishing war, disappointment and anger echo increasingly across Lebanon’s Shiite community, which has borne the brunt of thousands of Israeli airstrikes in south and east Lebanon and the southern suburbs of Beirut.

Weeks of an intensely destructive Israeli military campaign, which has included the killing of Hezbollah’s revered leader, Hassan Nasrallah, and much of the Iran-backed Shiite militia’s senior leadership, has displaced 1.3 million Lebanese. Across the south, near the border with Israel, entire villages have been destroyed.

Hezbollah supporters are tired, and far less forgiving of what they perceive to be the organization’s mistakes and battlefield shortcomings.

One such longtime supporter, a 30-something businessman in Beirut who gives the name Hussein, had his loyalty tested before, in the last all-out Israel-Hezbollah war in 2006. Then, an Israeli airstrike in Beirut killed 16 members of his family, including five children.

That destructive conflict was widely seen to have been triggered by Hezbollah’s own miscalculation back then: that a cross-border kidnapping and killing of Israeli soldiers would yield only a limited Israeli response.

And yet, until now, Hussein’s personal loss so many years ago did not detract from his support for Hezbollah. In fact, he says, it increased his backing for Hezbollah and its armed “resistance” against Israel, as a way to achieve revenge.

But fast-forward 18 years, and Hussein, along with many traditional Hezbollah supporters, today expresses doubts about Hezbollah and its decisions. This time the Israeli onslaught was sparked by more than a year of Hezbollah rocket attacks against northern Israel, in solidarity with Hamas in Gaza, its Palestinian ally in the Iran-led “Axis of Resistance.”

“They are saying they have surprises, but we are waiting to see,” says Hussein, of Hezbollah’s continued promises of fighting prowess.

“We expected much, much more than what is happening now. Like Sayyed Nasrallah said, one building destroyed in Dahiyeh [Hezbollah’s south Beirut stronghold] will be met with many buildings destroyed in Tel Aviv,” he says. “Unfortunately, until now, no buildings have been destroyed in Tel Aviv, which is surprising and disappointing us.”

Instead, entire apartment blocks have been flattened by Israel in Dahiyeh, as it targets Hezbollah leadership and infrastructure. Hussein’s shop remains intact, despite airstrikes two streets away.

Years of Hezbollah promises

“We feel that everything is happening for no reason, for nothing,” says Hussein, explaining that Hezbollah’s standing nearly alone in solidarity with Hamas was an insufficient argument for war.

Hezbollah “entered this war supporting Hamas, and no one else supported Hamas,” he says. “You have many Arab and Muslim countries. So why no one [else took] any action? And you want to do this.”

Hussein says he is angry that Israel has managed to deliver multiple body blows to Hezbollah – including an exploding pager attack that wounded thousands of fighters, and the assassination of Mr. Nasrallah – while Hezbollah so far has failed to deliver on years of promises that it would always inflict far greater pain on the Jewish state. Indeed, Hezbollah has yet to use many of its most potent weapons – precision-guided missiles – against Israel.

Hezbollah, which is also a well-funded political party that provides services to the Shiite community, still has some popular support. But patience is wearing thin because of intense civilian suffering.

“You know, this time we moved several times from house to house, because the places that are targeted are expanding,” says Hussein. “Even in Beirut we were thinking it was safe – it’s not safe anymore.

“We lost our jobs, our work – it’s a disaster. And all the news speaks about [Hezbollah] support. We are not supporting.”

That said, recent more effective Hezbollah strikes have won praise, and include a mid-October drone strike on the dining hall of Israel’s Golani Brigade, which killed four soldiers and wounded 67.

“People are seeing this, people are happy,” says Hussein.

“But it’s not done; it is taking a long time,” he adds. “The result of this war will be so important to the future of Hezbollah.”

Indeed, Hezbollah’s carefully burnished reputation as the most powerful arm of Iran’s “Axis” has been damaged.

For decades it has acted as a state with in a state, the self-declared defender of Lebanese territorial sovereignty – in place of Lebanese state forces too weak to do the job.

“On the path of war”

The organization’s newly named leader, Naim Qassem, vowed in a recorded speech Wednesday that Hezbollah was open to a cease-fire, but otherwise “will remain on the path of war.”

Referring to Hezbollah’s drone attack on Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s coastal home two weeks ago, he said, “Netanyahu survived this time, perhaps his time hasn’t come yet.”

But with the other top 20 or more Hezbollah chiefs and commanders killed in recent weeks, rumors swirled that Mr. Qassem had sought sanctuary in Iran. Israeli defense chief Yoav Gallant posted on the social platform X, “Temporary appointment. Not for long.”

So far, Hezbollah’s pledges are not enough for some former supporters.

“Our kids are on the streets because of you. Our houses are gone because of you,” complains one Shiite resident of Dahiyeh, describing the prevalent mood. “Where are you? Nobody to be found. You know what? We quit. We’re going to find a different way. They are struggling to get water, never mind getting food.

“All this happened in 10 days, I just can’t believe it,” says the resident, who asks not to be named and says he knew many Hezbollah members wounded in the pager attacks. “Never in my wildest dreams did I think this could ever, ever happen to Hezbollah. All the [big] talk, all the cause, all the strength, all the missiles, all the military, all the training, the [elite] Radwan Brigade. ... ‘We will go into Galilee.’ None of that.”

After Hezbollah’s strike on the Israeli dining hall, “People breathed a deep sigh of relief: Hezbollah still exists,” he says, recounting the scene: “One hundred of them watching one TV, with bad reception, staying up until morning. ‘Did they really do that?’ they asked. Another man: ‘Oh, they still have it; they still have it! Let’s give them another week.’ ...

“My brother jumped up [from the TV] and said, ‘I told you, they can’t be finished that fast: 40 years of training, 40 years of depositing missiles all over the country, 40 years of education, engineers sent all over the world to learn how to fire missiles, how to train special forces. ... They cannot be over in 10 days.’”

“People are tired”

Israel says it has destroyed half of Hezbollah’s missile arsenal and has uncovered elaborate fortified tunnel networks along the border. Hezbollah announces daily rocket attacks against Israeli military formations and communities in northern Israel – and says it is slowing Israel’s ground incursion – but those efforts inflict few casualties.

“Really, the bombing of the last one or two weeks is not enough to satisfy the bloodlust of people, who are waiting to see the reaction after the death of Nasrallah,” says another Shiite from southern Lebanon, who asks not to use his name, because of the sensitivity of criticizing Hezbollah.

“People are still on the streets,” he says. “I was a supporter before. What Hezbollah promised the people [to support them], they should fulfill, because people are tired. They are given a bit of help here and there. But if we [only] eat and drink water, is that what you call life? What kind of living is that?”

He says the party can still restore its reputation, despite the blows from Israel.

“It’s possible. We can see Hezbollah now breathing better, acting better, performing better. They are escalating,” he says. “They should make painful hits to the Israelis. For the people to change their minds – they have to hit real hard. Hit your enemy hard, hurt your enemy hard, make people come home.

“When we see victory, we forget how homeless we are – and we support Hezbollah again,” he says.

Points of Progress

Transformed playgrounds, and a bridge between art and science

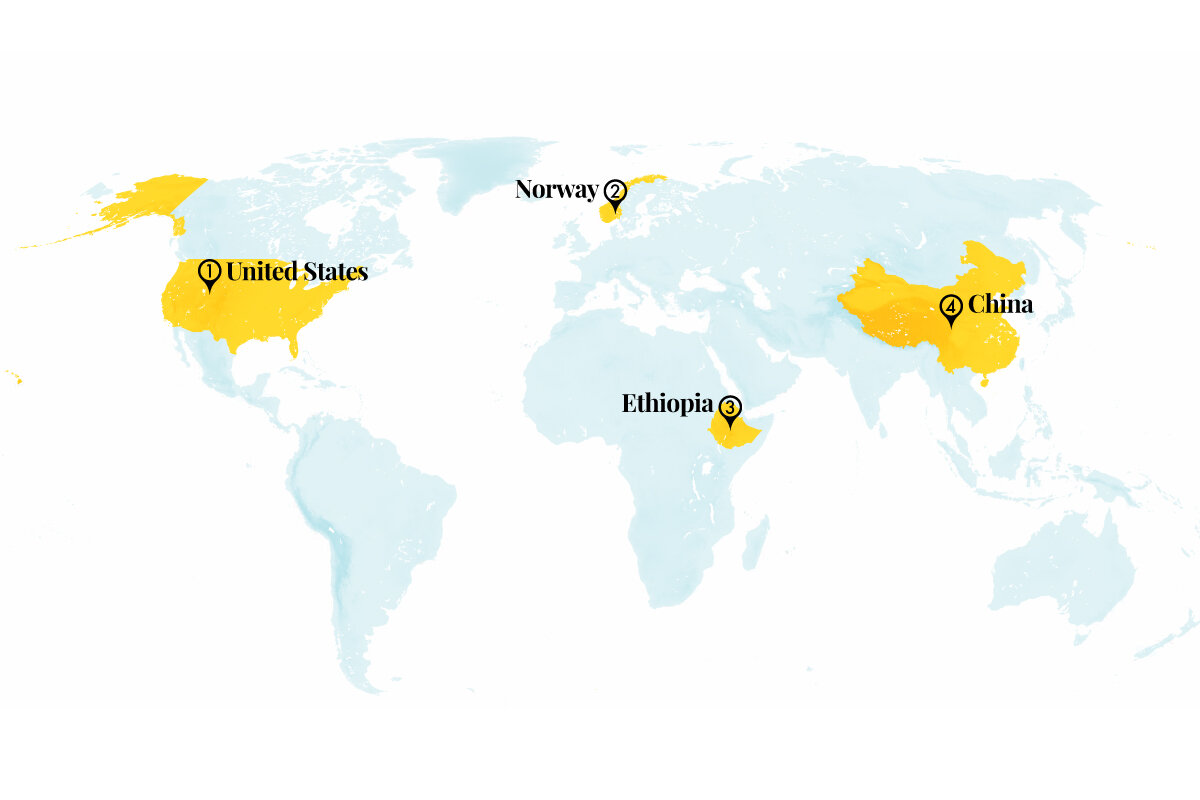

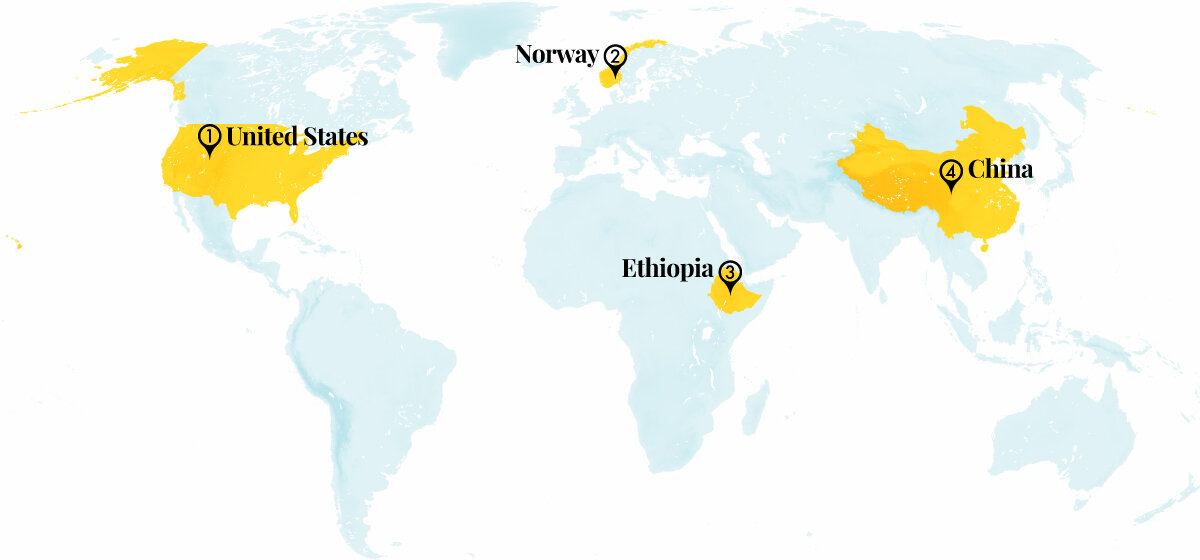

Broad approaches to solve multiple challenges yield results in our progress roundup. In Denver, greener playgrounds satisfied children’s needs and made the air cleaner. In universities worldwide, new galleries spark creativity by showcasing disciplines that rarely share space.

Transformed playgrounds, and a bridge between art and science

The benefits of greening Denver’s schoolyards have rippled outward

Landscape architect Lois Brink began thinking more about the impact of playgrounds after seeing the bleak yard at her children’s school. Between 2000 and 2012, she helped Denver Public Schools transform 99 schoolyards into vibrant, green spaces that prioritize physical activity, creative play, and outdoor learning.

A recent report commissioned by the Children & Nature Network found that these greener yards reduce average ambient temperatures in the summer, sequester carbon and remove pollutants from the air, and improve students’ academic performance and well-being. Given gains in high school graduation rates and community health, the analysis estimates the improvements could return $3 to a community for every $1 invested.

Denver voters twice approved ballot measures to fund transformations that cost an average of $630,000 – which were also aided by pro bono services, volunteers, nonprofits, and the city.

Green schoolyards are “a multifaceted solution,” said Priya Cook of the Children & Nature Network. “Markets tend to underinvest in strategies that produce broad benefits to society. ...We have to think differently to pick multi-solving interventions.”

Sources: Grist, Children & Nature Network

Oslo’s Climate Budget is making it easier for the city to meet its climate goals

Created in 2016 after Norway signed the 2015 Paris Agreement, the Climate Budget puts a limit on citywide emissions, tracks progress, and recommends new interventions. As a fiscal tool, it is integrated into the budgeting process affecting all municipal departments.

The budget is helping the city transition to electric vehicles, create net-zero construction sites, expand cycling lanes by 100 kilometers (62 miles), and install carbon-capture technology. Since 2016, the city has reduced greenhouse gas emissions by 28% and is on track to reach 65% by 2030. Cycling has increased by 51%.

“Our politicians got tired of climate action plans that they ... sent out into the bureaucracy, but then it was never really followed up,” said Heidi Sørensen, director of the Oslo Climate Agency. “They needed a governance system.” The framework has inspired 200 other Norwegian municipalities to follow suit.

Source: World Resources Institute

Ethiopia has dramatically reduced the threat of tuberculosis

While largely controlled in some parts of the world, TB continues to be a leading cause of death across Africa. Ethiopia had the world’s highest mortality rate from TB in 1980, with 394 deaths per 100,000 individuals. Following decades of public health initiatives, the East African country has reduced that rate sixfold, outpacing the progress made by countries facing the same problem.

In high-income nations, fewer than 1 in 100,000 people die from the disease each year. Still, life expectancy overall has increased across eastern sub-Saharan Africa, more than in any other region in recent decades, largely due to efforts in addressing TB and other prominent diseases.

Sources: Our World In Data, Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation

Lavender oil can be used to make mosquito-repellent fabric

Traditional synthetic repellents protect against mosquitoes and the diseases they carry but can cause their own health issues. Lavender oil is a natural alternative, but its compounds break down quickly in normal conditions. Textile engineers Zeeshan Tariq and Xiaoqin Wang at Soochow University in China discovered a way to prolong the effect.

Their team mixed lavender oil into a warm solution of fibroin, a flexible protein made by silkworms, and gum arabic, a substance from acacia trees that helps stabilize materials. When stirred, the mixture forms tiny lavender oil capsules that can be embedded in cotton fabric. Tests showed that gloves made from this fabric significantly reduced mosquito landings compared with regular gloves. Even after 40 washes, the treated fabric remained effective.

Source: The Economist

A new type of gallery is bridging the gap between art and science

In some educational systems, the arts and sciences are treated as entirely separate disciplines with little room for overlap. The Science Gallery aims to “[ignite] creativity and discovery where science and art collide” at its locations in Ireland, the United States, Australia, Britain, Germany, Mexico, and now India.

The latest addition in Bengaluru, also known as the Silicon Valley of India, features an exhibition, “Carbon,” that illustrates the human body by displaying varying sizes of jars filled with charcoal powder corresponding to the amount of carbon in each body part. The museum also hosts workshops, lectures, and performances and is planning an exhibition on the workings of quantum physics for next year.

Commentators have noted the importance of this sort of space in a place like India, where, despite a growing number of universities, multidisciplinary institutes are uncommon, and scientific output lags behind those of other large economies.

Sources: The Economist, Science Gallery

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Democracy’s gems in Botswana

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

A midsummer survey of attitudes about democracy in more than three dozen African countries captured a common desire reflected in the outcomes of elections all around the world this year. “The evidence suggests that nurturing support for democracy will require strengthening integrity in local government and official accountability,” Afrobarometer stated.

In Botswana, a surprising ballot upset revealed an important factor shaping those aspirations: a breaking down of what one African think tank called a “dependency mindset.”

The small nation in the Kalahari Desert has been one of the continent’s most stable and prosperous. But its dependence on a single natural resource, diamonds, has now left it vulnerable to tumbling prices. Joblessness has reached 28%, exacerbating income inequality. Trust has fallen, too.

Last week, voters ousted the party that has ruled the southern African nation for 58 years. The new president, Duma Boko, has promised to pursue diversification. Like the rest of Africa, Botswana is brimming with a new generation of innovators and entrepreneurs eager for opportunity.

Mr. Boko acknowledged that his election “happened in full view of every citizen of this country with their full participation and endorsement.” He may see his fellow citizens as the diamonds of a more inclusive new economy.

Democracy’s gems in Botswana

A midsummer survey of attitudes about democracy in more than three dozen African countries captured a common desire reflected in the outcomes of elections all around the world this year. “The evidence suggests that nurturing support for democracy will require strengthening integrity in local government and official accountability,” Afrobarometer stated.

In Botswana, a surprising ballot upset revealed an important factor shaping those aspirations: a breaking down of what one African think tank called a “dependency mindset.”

The small nation in the Kalahari Desert was one of the poorest in Africa when it was established in 1966, but it became over time one of the continent’s most stable and prosperous. The reason was diamonds. Unlike most countries endowed with a singular wealth-generating natural resource, Botswana avoided most of the traps of the “resource curse.” It had dependable tax rules, protections for private priority, and notably little corruption.

But also little agility. The rise of lab-grown diamonds, mostly from China, has set shocks through the industry. Prices are down 6% this year alone, according to international indexes, and are still tumbling. That has compounded conditions in Botswana, where employment has failed to keep pace with a rising new generation. Joblessness has reached 28%, exacerbating income inequality.

Trust has fallen, too. Just 30% of citizens, the Afrobarometer survey found, were satisfied with democracy in Botswana, down from 70% a decade ago.

Last week, voters showed their frustration. They ousted the party that has ruled the southern African nation for 58 years in favor of a new coalition of opposition parties led by a Harvard-educated human rights lawyer. In his first act after taking power Monday, Duma Boko nominated a young economist with an MBA from the Wharton School and a reputation for fighting corruption to be his vice president.

The abundance of a single natural resource can be ruinous. In Nigeria and the Democratic Republic of Congo, oil and cobalt have fueled rampant long-term corruption, poverty, and conflict. Some countries are striving to break such dependency. In Saudi Arabia, for example, reforms empowering women in the workplace reflect a shift in both value and values. A country made rich by a finite commodity is cultivating new wealth in a more inclusive workforce.

Mr. Boko has signaled a similar shift. “We are an economy that depends on diamonds. ... So we have to safeguard the goose that lays the golden egg and have some revenue generation while we pursue diversification” of the economy, he said Friday. Like the rest of Africa, Botswana is brimming with a new generation of innovators and entrepreneurs eager for opportunity.

Mr. Boko acknowledged that his election “happened in full view of every citizen of this country with their full participation and endorsement.” That humility and respect for his fellow citizens may enable him to see them as the diamonds of a more diverse and equitable economy.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

The awakening that heals

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 4 Min. )

-

By Scott L. Schneberger

An openness to the idea that reality isn’t necessarily what it seems to be – is spiritual, not material – brings a spiritual awareness that restores health.

The awakening that heals

When I was about four years old, a very hard-hit baseball struck the bridge of my nose. Right away my parents wrapped me up in their arms and comforted me. My family had experienced the effectiveness of prayer before, so one of my parents turned to God in prayer while the other took me to a hospital, feeling that that was best at the time.

At the hospital, a doctor took an X-ray of my head and explained that there were a number of broken bone fragments. He insisted on an operation the following morning to rearrange them properly for healing. Because the surgery wasn’t scheduled until the morning, one of my parents asked a Christian Science practitioner to provide treatment through prayer.

By the next morning, through Christian Science treatment alone, I’d been completely healed. When my parents brought me back to the hospital, the same doctor took another X-ray to see if the pieces had shifted overnight. He and another doctor studied both X-rays and told my parents that they couldn’t explain it, but there was nothing there that they needed to operate on – my skull was now perfectly whole, with no signs that there had ever been any breakage.

In the years since, I’ve thought deeply about that healing, which came about overnight without any physical treatment or surgery. How was that possible?

It has made me think of a nighttime dream I once had, in which I had a severely broken arm and felt fearful and desperate. But then I experienced immediate and total relief – not by resetting bones, but simply by waking up. Although the dream-breakage had seemed very real, it wasn’t, and the “problem” and fear vanished instantly with that realization.

This has been a useful analogy as I think more deeply about how Christian Science heals. Mary Baker Eddy, the discoverer of Christian Science, wrote, “Mortal existence is a dream of pain and pleasure in matter, a dream of sin, sickness, and death; and it is like the dream we have in sleep, in which every one recognizes his condition to be wholly a state of mind” (“Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” p. 188).

This has helped me see that there is something deeper and truer than the picture of mortal existence. That something is the spiritual reality. On that basis, one can experience healing by approaching a problem as a dream, or a misperception of spiritual reality – from which one can wake up.

At the heart of that awakening are the foundational truths that God is not material, but is infinite Spirit; that God is not limited in any way, but is infinitely and eternally good and all-powerful; that God is the sole divine Mind; and that God’s creation must then consist of ideas that reflect His nature. Anything less could not be true about the all-powerful, infinite God and His creation – which includes each of us as His child. Everything God creates must be entirely spiritual, perfect, and eternal.

Where, then, does that leave sickness, injury, etc.? Those opposites of God, good, simply cannot exist in God’s realm. Certainly, they can seem very real to us – as sleeping dreams can seem real even though they are not. But such discord’s claim to legitimacy doesn’t come from the divine Mind, God, but from the counterfeit of Mind, which the Bible calls the carnal mind. This so-called mind is the dreamer, but its thoughts are never truly our thinking.

Through prayer – whether our own or that of someone else praying for us – thought is awakened to the spiritual reality of existence. As Mrs. Eddy wrote, “... awakening from this mortal dream, or illusion, will bring us into health, holiness, and immortality” (Science and Health, p. 230).

That this awakening leads to such transformation is supported by Jesus’ healing works as recorded in the Bible. Some of those healings took place instantly and without any physical contact with, or even close proximity to, the person being healed. There is a divine Science behind such healing – a Science that can be applied to any situation, by anyone. Jesus affirmed that when he said, “He that believeth on me, the works that I do shall he do also; and greater works than these shall he do” (John 14:12).

There are thousands of verified accounts of metaphysical healing published in Christian Science literature, including this column. These testimonies are accounts by people describing how they were healed of various ailments through study of the Bible and Science and Health and the prayer-based treatment taught in these Christian Science textbooks.

Christian Science prayer is indeed effective in addressing the dreamlike suggestion of sin, sickness, and death – but what’s being done is metaphysical, spiritual, divine – not physical. As I experienced after that ball hit my face and have experienced many times since, this divine Science is reliable and practical – and it’s here for anyone who wishes to apply it for themselves!

Viewfinder

Marathon moment

A look ahead

Thank you for joining us today. Please come back to CSMonitor.com tomorrow for our Election 2024 live updates blog.