- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- ‘I’m exhausted by him.’ Why Trump resistance is fizzling.

- Today’s news briefs

- Moody chickens? Playful bumblebees? Science decodes the rich inner lives of animals.

- Recurring blackouts have roiled Cuba. What’s behind the crisis?

- In the race to attract students, historically Black colleges sprint out front

- Our food writer serves up a holiday’s history and hits

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Talk with the animals?

You’ve probably wondered at one time or another about how animals think. What motivates a dog to cajole us to play, or to protect us from a danger we may not perceive? Do cows think only about chewing their cud when out in the field? How do the many creatures we see every day, in cities and in the wild, experience the world?

It’s a question that occupies a growing number of scientists studying animal consciousness. They’re painting, as writer Stephanie Hanes reports in her fascinating story today, an increasingly complex portrait of how nonhuman creatures from goats to bumblebees interact with their environment. It’s work that may inform all sorts of human activity, from where we build roads to what we eat. It may change your perspective.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

‘I’m exhausted by him.’ Why Trump resistance is fizzling.

The first election of Donald Trump fueled major protests, including the Women’s March. This time around, the self-dubbed “resistance” movement looks less energized.

When Donald Trump won the presidency in 2016, narrowly defeating Democrat Hillary Clinton, it landed like a “gut punch” to Kim Whittaker, a party activist and fundraiser.

This year’s electoral defeat, while upsetting, didn’t feel quite as shocking, she says – though she believes the consequences could be greater. And unlike in 2016, Ms. Whittaker isn’t taking to the streets. Like many on the left, she’s asking, what’s the point?

A presidential loss always packs a punch. But the second election of Mr. Trump, and his triumph over Vice President Kamala Harris, is rippling outward in a more profound and debilitating way among some of the women who championed resistance to his first presidency.

What had seemed like an aberration – a one-term president who twice lost the popular vote – now feels like a grim reality, one that no flurry of online or real-life protests can shake loose.

Some participants in the 2017 Women’s March, which in total included more than 4 million people nationwide, are organizing a “People’s March” in Washington on Jan. 18, two days before Mr. Trump’s second inauguration. Their permit application is for up to 50,000 people, far fewer than the half a million participants who showed up on the National Mall in 2017.

‘I’m exhausted by him.’ Why Trump resistance is fizzling.

When Donald Trump won the presidency in 2016, narrowly defeating Democrat Hillary Clinton, it landed like a “gut punch” to Kim Whittaker, a party activist and fundraiser. To see her candidate lose to a man who boasted of groping women and promised to end federal protections on abortion rights was devastating.

Soon after, she began organizing a protest march in Boston against President-elect Trump that drew more than 100,000 people, part of an unprecedented show of defiance led by women across the country.

This year’s electoral defeat, while upsetting, didn’t feel quite as shocking, she says – though she believes the consequences could be greater. And unlike in 2016, Ms. Whittaker isn’t taking to the streets. Like many on the left, she’s asking, what’s the point?

The January 2017 Women’s March was “a once-in-a-lifetime moment,” she says. “Anything that we tried to do coming on the heels of that would just fall short, and what is the purpose of that? If it’s to show strength in numbers, I don’t think we’re going to get the same numbers.”

A presidential loss always packs a punch. But the second election of Mr. Trump, and his triumph over Vice President Kamala Harris, is rippling outward in a more profound and debilitating way among women who championed resistance to his first presidency. What had seemed like an aberration – a one-term president who twice lost the popular vote – now feels like a grim reality, one that no flurry of online or real-life protests can shake loose.

“There is definitely a camp of people that say, ‘I need to withdraw right now. Like, I can’t listen to the news. I can’t talk about this guy anymore. I am exhausted by him,’” says Ms. Whittaker, an events organizer in Winchester, Massachusetts.

A “People’s March” up next

Some participants in the 2017 Women’s March – which in total included more than 4 million people in towns and cities nationwide, making it the largest single-day protest in U.S. history – are now organizing a “People’s March” in Washington on Jan. 18, two days before Mr. Trump’s second inauguration. But their permit application is for up to 50,000 people, far fewer than the half a million participants in 2017, when the National Mall became a sea of women wearing knitted pink hats.

Organizers say they expect marches to happen in other cities on the same day. The president of the Women’s March Foundation in Los Angeles, however, has said that her organization – a separate group – doesn’t want to allocate its resources toward a large-scale protest and has no plans to mobilize for a march. In 2017, around 750,000 people marched to City Hall in Los Angeles.

The groundswell after Mr. Trump’s first election was driven not just by seasoned political activists but by first-time participants reacting to what they saw as a political earthquake, says Lisa Mueller, an associate professor of political science at Macalester College. “It was a uniquely galvanizing moment for people who don’t normally participate in street protests. We don’t have the shock and novelty this time,” she says.

President-elect Trump, who won the popular vote this time, appears far better prepared to implement his agenda in his second term, given his sway over a Republican Party that will control both chambers of Congress, and a conservative majority on the Supreme Court. In the face of what seems to many like an impending juggernaut of conservative policy enactments, there’s far less optimism about the power of hashtags, petitions, and protests to push back.

Expansive coalition, vague agenda

This sense of futility isn’t universal. Organizations like Planned Parenthood, the American Civil Liberties Union, and others are asking donors to support them as they prepare to challenge the next administration’s policies, including on abortion access and immigrant rights.

But the rush to the barricades that accompanied much of Mr. Trump’s first term, from the first Women’s March to the racial justice protests in the summer of 2020, has given way to soul-searching about what activism can actually accomplish. Similar doubts were raised in the wake of the Occupy Wall Street movement in 2011, which popularized the slogan, “We are the 99%,” and, like the Women’s March, inspired protests in cities around the world.

What both of those grassroots movements had in common was a diffuse set of demands that didn’t cohere into a single political agenda, says Professor Mueller, who studies social movements and is the author of “The New Science of Social Change: A Modern Handbook for Activists.” “It’s really difficult to point to any concrete outcome of either of these movements,” she says.

Standing on the Mall in January 2017, she saw signs for reproductive rights alongside others for environmental protection and transgender inclusion. That expansive coalition, and the appeal to participants who didn’t think of themselves as activists, was in some ways a strength. But it also meant the Women’s March lacked the singular focus of a social movement like the March for Life, an annual antiabortion event that began more than 50 years ago to oppose Roe v. Wade, says Professor Mueller. “There’s no mistaking their demand.”

Even when progressives rally behind a single cause, success isn’t guaranteed. Student-led protests that roiled campuses across the country earlier this year had little or no effect on U.S. support for Israel’s war in Gaza under a Democratic administration. President-elect Trump has meanwhile offered full-throated support for Israel’s military and said he would use military force at home to suppress civil unrest, something he talked about doing during the 2020 racial justice protests.

In general, governments around the world have become hardened against social movements that challenge their authority; nonviolent civil protests today are more likely to fail than they were a generation ago, according to an influential Harvard study. This trend cuts across different types of government but is more pronounced under authoritarian states.

“This election felt different”

When the election results came in this year, Vanessa Wruble, who helped organize the first Women’s March, was sitting in her living room in Southern California watching with friends. As Mr. Trump’s victory became clear, it felt to her “like something really deep has been lost. It just got very, very morose in the room, and basically everyone just stood up and left.”

That’s similar to how she felt in 2016. But this time, she’s not calling fellow progressives to mobilize in response. She has stepped back from full-time activism, having left New York City during the pandemic and set up an animal sanctuary and art space in a desert community. She also now keeps her distance from the Women’s March, which she left in 2017 amid internal divisions. Ms. Wruble, who is Jewish, faced what she considered antisemitism from other leaders – who have since drawn criticism from others on the left – further splintering the organization and dimming its appeal.

“This [election] felt different. The reaction was different,” she says. “I think people feel sad and people feel despair. But I don’t think that’s an unnatural response or even a bad response.”

She adds, “Right now is really a time for reflection, for diagnosing the problem rather than jumping into an action that I don’t think would be particularly effective.”

To Ms. Wruble, President-elect Trump’s victory this month doesn’t negate the successes of the movement she helped start. It led to more women running for political office, helped seed new grassroots groups like Indivisible, and contributed to a blue wave in the 2018 midterms and Joe Biden’s win in 2020. That energy and commitment were real and lasting, she says.

Indivisible, which was founded by two Democrats in 2016 who wrote a guidebook on how to pressure Congress, has urged supporters to come together locally and to think broadly about resistance to Mr. Trump’s agenda, including at state and local levels. Their message: Stay focused on the 2026 midterms and on building communities. “Trump wants us to believe that the presidency is all-powerful. It ain’t true,” the group’s founders wrote in a guide to “democracy on the brink.”

Ms. Whittaker is also thinking ahead, conserving her energy for what she expects to be a tumultuous political era. Progressives have to pick their battles, she says. “We need to be smart and effective.... The authoritarian playbook is to celebrate apathy. I think we need to shake off that momentary feeling of despair and resist apathy, and people will reengage.”

News Briefs

Today’s news briefs

• New threat to Ukraine: NATO and Ukraine will hold emergency talks Nov. 26 after Russia attacked a central city with a hypersonic ballistic missile.

• Attorney general nominee: President-elect Donald Trump has named Pam Bondi, the former attorney general of Florida, to lead the United States Justice Department after Matt Gaetz withdrew.

• Climate deal falls flat: The COP29 climate summit ran into overtime after a draft deal that proposed developed nations take the lead in providing $250 billion per year by 2035 to help poorer nations drew criticism from all sides.

• Gift for North Korea: South Korea said Russia has provided the North with anti-air missiles and air defense equipment in return for sending troops to support Moscow in its war against Ukraine.

• Coup attempt fallout: Police indicted Brazil’s former President Jair Bolsonaro and 36 other people on Nov. 21 for allegedly attempting a coup to keep the leader in office after his defeat in the 2022 elections.

• Trump hush money case postponed: President-elect Donald Trump won’t be sentenced this month, but Judge Juan Merchan set a schedule for prosecutors and lawyers to expand on ideas about what to do next.

A deeper look

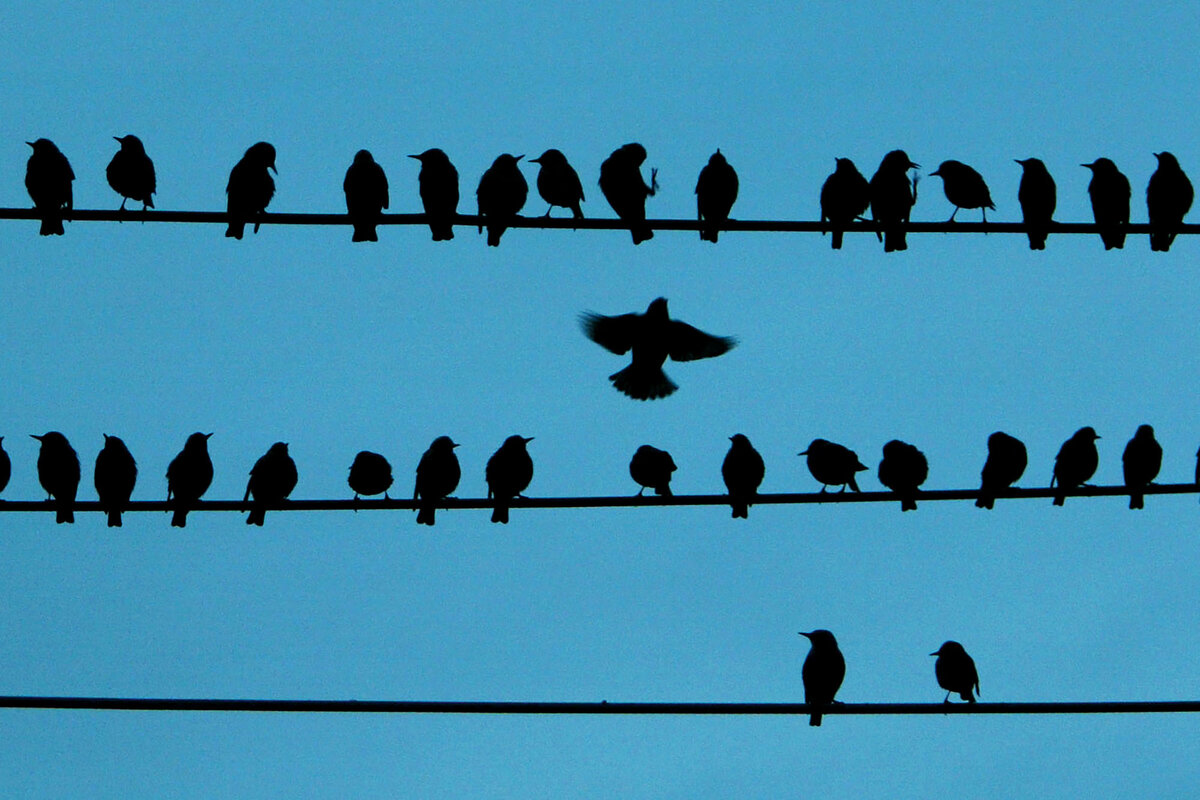

Moody chickens? Playful bumblebees? Science decodes the rich inner lives of animals.

New research shows that many animals exhibit signs of experiencing emotions and being self-aware. How should this affect how we see them – and ourselves?

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 15 Min. )

-

Melanie Stetson Freeman Staff photographer

Do animals have conscious experiences?

This past April, a group of biologists and philosophers unveiled The New York Declaration on Animal Consciousness at a conference at New York University in Manhattan.

The statement declared that there is “strong scientific support for attributions of conscious experience to other mammals and to birds.” It also said that empirical evidence points to “at least a realistic possibility of conscious experience” in all vertebrates and many invertebrates, including crustaceans and insects.

Researchers have found myriads of indications of perception, emotion, and self-awareness in animals. The bumblebee plays. Cuttlefish remember how they experienced past events. Crows can be trained to report what they see.

Given these findings, many believe there should be a fundamental shift in the way that humans interact with other species. Rather than people assuming that animals lack consciousness until evidence proves otherwise, researchers say, isn’t it far more ethical to make decisions with the assumption that they are sentient beings with feelings?

“All of these animals have a realistic chance of being conscious, so we should aspire to treat them compassionately,” says Jeff Sebo, director of the Center for Mind, Ethics, and Policy at New York University. “But you can accept that much and then disagree about how to flesh that out and how to translate it into policies.”

Moody chickens? Playful bumblebees? Science decodes the rich inner lives of animals.

Sasha Prasad-Shreckengast is trying to get into the mind of a chicken.

This is not the easiest of feats, even here at Farm Sanctuary in Watkins Glen, a scenic hamlet in the rolling Finger Lakes region of upstate New York. For decades the sanctuary has housed, and observed the behavior of, farm animals – like the laying hens Ms. Prasad-Shreckengast is hoping to tempt into her study.

Chickens, it turns out, have moods. Some might be eager and willing to waddle into a puzzle box to demonstrate innovative problem-solving abilities. But other chickens might just not feel like it.

Ms. Prasad-Shreckengast also knows from her research, published this fall in the Journal of Applied Animal Welfare Science, that some chickens are just more optimistic than others – although pessimistic birds seem to become more upbeat the more they learn tasks.

“We just really want to know what chickens are capable of and what chickens are motivated by when they are outside of an industrial setting,” Ms. Prasad-Shreckengast says. “They have a lot more agency and autonomy. What are they capable of, and what are they interested in?”

In other words, how do chickens really think? And how do they feel? And, to get big picture about it, what does all of that say about chicken consciousness?

In some ways, these are questions that are impossible to answer. There is no way for humans, with their own specific ways of perceiving and being in the world, to fully understand the perspective of a chicken – a dinosaur descendant that can see ultraviolet light and has a 300-degree field of vision.

Yet increasingly, scientists like Ms. Prasad-Shreckengast are trying to find answers. What they are discovering, whether in farm animals, bumblebees, dogs, or octopuses, is a complexity beyond anything acknowledged in the past.

(At least in Western culture, that is. The 17th-century philosopher René Descartes, for example, ushered in an influential idea that understood animals to be mere mechanical “automatons.” Ascribing feelings or emotions to animals, he and his many followers believed, was misguided.)

Researchers have found myriads of indications of perception, emotion, and self-awareness in animals. The bumblebee plays. Cuttlefish remember how they experienced past events. Crows can be trained to report what they see.

As a result, a growing number of scientists and philosophers believe there is at least a realistic possibility of “conscious experience” in all vertebrates, including reptiles and fishes, and many invertebrates.

Given these findings, many believe there should be a fundamental shift in the way that humans interact with other species. Rather than people assuming that animals lack consciousness until evidence proves otherwise, isn’t it far more ethical to make decisions with the assumption that they are sentient beings with feelings?

Ms. Prasad-Shreckengast’s study takes place in the wide hallway of Farm Sanctuary’s breezy chicken house. Unlike in pretty much any other chicken facility, the birds here come and go as they please from spacious pens.

Following up on her previous research, she has designed a challenge that she hopes will appeal to most of her moody chickens. It is a ground-level puzzle box, with a push option, a pull option, and a swipe option. Birds are rewarded with a blueberry when they solve a challenge.

There is also a free treat option in the puzzle box, a way for the researchers here to measure something called “contrafreeloading.” This term describes a behavior animals demonstrate when they choose to work for a reward rather than just freeloading from readily available food. (Scientists are still debating why most animals contrafreeload. They are also interested in the exception to the rule: the domesticated cat, who appears perfectly happy to take food without expending any effort.)

Team members monitor a series of gates to the puzzle block, opening them when the birds are inclined to enter and letting them out if the chickens have had enough.

The idea of consent – which is a basic, foundational principle in the study of human behavior – is also a hallmark of animal studies here at Farm Sanctuary. To the uninitiated, this might sound absurd, with images of chickens signing above the dotted line.

But it is not actually all that rare. Studies of dogs, dolphins, and primates all depend on the animals agreeing, in their own way, to participate. Behavioral data would be skewed without it. And before she came to Farm Sanctuary, Ms. Prasad-Shreckengast worked in a canine cognition lab. Few people would bring their pet dogs in for research and then force them to do things they don’t want to do, she points out.

So consent matters from both a scientific point of view and an ethical one, she says.

Do animals have conscious experiences? Evidence is strong.

A group of Biologists and philosophers this past April unveiled The New York Declaration on Animal Consciousness at a conference at New York University in Manhattan.

The statement declared that there is “strong scientific support for attributions of conscious experience to other mammals and to birds.” It also said that empirical evidence points to “at least a realistic possibility of conscious experience” in all vertebrates and many invertebrates, including crustaceans and insects. Since April, hundreds more scientists and moral thinkers around the world have added their names.

Spearheaded by Kristin Andrews, professor of philosophy and the research chair in animal minds at York University in Canada, the idea emerged from conversations she had with two colleagues, Jonathan Birch, a philosopher at the London School of Economics and Political Science, and Jeff Sebo, director of the Center for Mind, Ethics, and Policy at New York University.

The three were talking about all the new research demonstrating the complexity of animals’ inner lives. They wondered if there was a way to highlight how these studies were shifting attitudes.

“People were dimly aware that new studies were identifying new evidence for consciousness – not only in birds, but also reptiles, amphibians, fishes, and then a lot of invertebrates, too,” says Dr. Sebo. “But there was no central, authoritative place people could look for evidence that the views of mainstream scientists were shifting.”

Discovery after discovery over the past decade has illuminated an increasingly complex, communicative, and feeling world of nonhuman creatures.

For instance, trees communicate, and fungal networks send messages throughout a forest. Species such as sea turtles and bats use electromagnetic fields, a force we cannot even perceive, to guide their movements and migrations. Snakes see infrared light, birds and reindeer see ultraviolet light, and dolphins use sound waves to navigate underwater.

Author and journalist Ed Yong uses the German term umwelt to describe an organism’s unique sensory perspectives. His book “An Immense World” details the various ways animals experience their world.

He uses the metaphor of a large house with many windows looking onto a garden. Each animal has its own window. But there are other windows as well, each with a different view of the same place. We humans have our own window, our own particular umwelt. Our eyes see only certain wavelengths and frequencies of light. Our ears perceive limited ranges of sound. Our noses have limited ranges of smell.

For generations, the dominant perspective has been that the human perspective is the best view in the house, with the most complex and complete picture of reality.

But there hasn’t been a species studied over the past 20 years that hasn’t turned out to exhibit pain. There hasn’t been a species that hasn’t turned out to be more internally complicated than people expected, Dr. Andrews says.

“There hasn’t been any animal that we’ve looked at and asked, ‘Do they feel pain with the set of pain markers that are well established?’ And we’ve said, ‘Oh, yeah, there’s zero evidence,’” she says. “We don’t find any of them.

“So my view is that we’re going to be finding these kinds of indicators of cognitive behavior, of behaviors indicating animals feel pain or feel pleasure, in probably all animals.”

But does that mean consciousness?

“Just that word, ‘consciousness,’ is the problem,” Dr. Andrews says. “The thing that everybody in the field agrees on is that consciousness refers to feeling – ability to feel things. ... But then if you start asking people to give a real, concrete definition of consciousness, they’re not able to do it.”

What exactly IS consciousness?

The concept of consciousness has kept a small army of moralists, physicists, and theologians busy for generations. Today there is an entire field called “consciousness science,” in which academics debate the philosophical and physiological meanings of the word.

The concept, after all, can take on different tones. Anesthesiologists have one interpretation of “conscious.” Psychologists have another. Philosophers and religious scholars also have their own varying views.

An increasing number of mainstream scientists and researchers also point to a consciousness that is outside individuals, sometimes called “universal consciousness.”

For the purposes of the declaration, researchers said, they focused on what is called “phenomenal consciousness.” This is the idea that “There is something that it’s like to be a particular organism,” explains Christopher Krupenye, professor of psychological and brain sciences at Johns Hopkins University.

Phenomenal consciousness can be a bit of a hard concept to get one’s head around at first, he says. But it basically means that an animal experiences the world not as a machine, but as a being. Phenomenal consciousness is what you are experiencing right now in your body with the sight of words on a page as you read this article.

There is another type of consciousness often called “metacognition,” in which a being is aware of what’s going on in its own mind. It is recognizing, for instance, that the temperature you feel is unpleasant, and then thinking that perhaps you should turn up the thermostat. It is recognizing that the words on the page are too small and that you should grab your reading glasses.

“Theory of mind” is another connected concept. You recognize that another person reading this article is not you, but that they can have an experience similar to yours.

Current research, including Dr. Krupenye’s, suggests that both dogs and primates display all these forms of consciousness.

In one of his studies, for instance, he was able to track eye movements of chimpanzees, bonobos, and orangutans in order to gauge whether or not they expected an unseen ape to see them through a transparent barrier. He found these primates were able to assume another being was having a similar but different experience from what they were having themselves, given their own perspective on the world.

Other studies show that dogs look to their owners for assistance when they do not understand a command, and that they look for clues and more information when they are having difficulty solving a task. Researchers believe this indicates dogs recognize their own ignorance – a sign of metacognition.

But of course there’s no way to prove, or even fully understand, what dogs or apes are experiencing, Dr. Krupenye says.

“You’re identifying one of the core philosophical challenges in this area of research,” he says. “With the case of phenomenal consciousness, in humans we take it as the case that if they verbally report they feel X or Y, we agree that’s what they are feeling. With animals, we can’t ask directly for them to verbally report.”

So researchers use alternative indicators to gauge how a nonhuman animal is thinking or feeling – such as tracking eye movement. But even this gets tricky. What about an animal whose umwelt isn’t visual at all?

“My dog’s experience of the world is much more dominated by smell data and much less by sight data,” says Dr. Sebo. “Different kinds of experiences might cause them different bodily pleasure and pain, but also different emotional pleasure and pain.”

For years, researchers were cautioned not to anthropomorphize their subjects, or bestow human traits upon other animals. Most scientists still agree with many of the tenets of this.

Dogs, for instance, don’t necessarily like what humans like, and most researchers agree that it is ethically important to keep those distinctions in mind. Think here about a dressed-up poodle. Its clothing and accessories are about human preferences. But the poodle might prefer an odor on the neighbor’s lawn. That’s a dog preference. Ethicists say it is important to be aware of this distinction, and not behave as if the poodle actually loves pompoms.

Many animal researchers now say worries about anthropomorphism went too far. The human umwelt might be different from those of other animals, they say, but there is still a deeper quality of being-in-the-world that is similar.

Heather Mattila, a biologist at Wellesley College in Massachusetts, generally tries to sidestep the question of consciousness in the bees she studies – even though it’s what most interests her students.

Trying to determine consciousness leads down a complicated philosophical path, she says. It is difficult to prove anything. She is an empirical scientist, which is all about working with solid, replicable studies.

But in her personal opinion, there’s no question: Bees likely have consciousness. She watches bees map locations, share information, and dance in a way that appears excited when they have found a particularly tasty food source. (She has learned to write “vigorous” rather than “excited” in research papers to avoid sparking the critiques of reviewers.)

Other researchers have also detected play behavior in some bees. All in all, the insect’s behavior reminds her of the rescued dog she grew up with – an animal that convinced her that other species had full personalities and cognition. “In a human mind, we would just assume consciousness is involved,” Dr. Mattila says.

“We should aspire to treat them compassionately.”

But assuming consciousness in other species brings up profound moral quandaries. If it turns out that animals do have feelings, or if they do participate in this big, amorphous concept called consciousness, what would that mean for the way humans interact with the rest of the living world?

The scholars who signed the New York declaration tried to stay ambiguous on that point.

“All of these animals have a realistic chance of being conscious, so we should aspire to treat them compassionately,” says Dr. Sebo at New York University. “But you can accept that much and then disagree about how to flesh that out and how to translate it into policies.”

For Dr. Mattila and others, the possibility of consciousness has meant limiting the extent to which her scientific experiments cause harm.

“I know many strict vegans would not approve of me keeping honeybees on campus, but I feel like I’m supporting them,” Dr. Mattila says. “I specifically try to do experiments that don’t cause them pain or suffering. ... I try to let them have a good life and observe how they operate within that good life.”

But it also has her thinking more broadly about how humans and other animals cross paths and interact with each other. Should the real possibility of complex animal consciousness make a difference in where we build roads? Should it guide how we “consciously” take control of ecosystems? And should it impact how, and what, we eat?

Such ethical considerations could impact an array of human activity. “It’s culturally inconvenient to think that animals are conscious,” Dr. Mattila says.

Especially farm animals. Although research on animal sentience and intelligence has expanded to include a host of different species, there is still a gap when it comes to the animals we kill for food.

The agricultural industry has long focused on animal welfare within the context of the food system, and there have been industry-wide efforts to slaughter animals in the most humane way possible.

But a group of international researchers in 2019 published a report in the journal Frontiers in Veterinary Science that found a decided lack of information on the “physico-cognitive capacities” of farm animal species.

While there has been loads of research on animal husbandry, there has not been all that much investigation into animals’ conscious experiences outside their role as food products for humans.

To Ms. Prasad-Shreckengast and others at Farm Sanctuary, there are clear reasons for this. The first is that we generally want to distance ourselves from those creatures we eat. Multiple studies have shown that meat-eaters engage in something called “cognitive dissociation” to help alleviate the discomfort that comes if one starts to learn about the emotions or physical experiences of a pig or cow or chicken.

But there are also funding issues. Most scientific research on farm animals is funded by agricultural schools focused on industrial practices or is funded by large agribusiness companies themselves. And farm animals generally live in a way that some scientists say is not conducive to understanding individual sentience.

“When you’re thinking of chickens, specifically in a barn with 30,000 chickens, you can’t see an individual,” says Ms. Prasad-Shreckengast. The study she published this October focused on the behavior of Cornish hens – usually slaughtered after they reach 6 weeks of age.

There isn’t a lot of existing information about the Cornish hen’s interior life, she says, because they aren’t usually allowed to live long enough to study as adults.

Farm Sanctuary is explicit in its promotion of a vegan diet – it was founded by a California-born animal activist named Gene Baur, whose work revealing animal cruelty at industrial farms and slaughterhouses helped lead to animal welfare laws.

Because of that, however, critics have called its animal science research biased – a charge researchers here reject.

“There’s no reason to not offer somebody the benefit of the doubt of sentience, the benefit of the doubt of consciousness, and to provide research methods that respect their agency and autonomy,” Ms. Prasad-Shreckengast says. “You can still do really good science with those ethics in place.”

On tours at Farm Sanctuary, guides introduce visitors to goats who make family groups; cows who, when no longer confined to dairy barns, prance and play and take care of their young; and pigs who, given the space, build themselves nests in a barn but go outside to relieve themselves.

It is an explicit effort to introduce humans to the individuals within other species, says Mr. Baur. The purpose is simple: to normalize empathy for fellow creatures.

“What we’re trying to achieve here are relationships of mutuality with us and other animals, where everyone benefits by the interaction, instead of relationships of extraction, where those with power take from those without,” he says.

Promoting a vegan ethic, however, isn’t the only valid way to understand the relationship between humans and farm animals – even for those convinced they have consciousness.

For Dr. Andrews, the key thinker behind the New York declaration, the question of how to live in a world of infinite consciousnesses has more to do with negotiation than with moral absolutes.

She believes it is impossible to completely avoid causing harm. The bacteria on our skin are disrupted when we wash. Animals in the wild eat other animals. When she finds flower-

eating aphids in her garden, she kills the insects to save the plants.

“It’s about acknowledging that harms are part of life, and we’re committing some harms, but we’re trying to minimize the harm that we do when we’re making our choices,” Dr. Andrews says.

It’s also recognizing that humans are not separate or unique, but part of an ecosystem with a dazzling array of individuals and understandings of the world – and a dazzling array of consciousness.

“It’s driving us to see ourselves as part of an integrated system of biology,” she says. “And that is probably better for the planet.”

The Explainer

Recurring blackouts have roiled Cuba. What’s behind the crisis?

Cubans are already living through an economic crisis that has affected the cost of basic goods. Recent recurring power outages are only exacerbating problems in the country.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

-

By Whitney Eulich Special correspondent

Blackouts have been a regular feature in Cuba for decades. But in recent months, the problem has escalated – lasting longer and occurring more frequently. Here’s a look at the factors driving outages on the island.

Recurring blackouts have roiled Cuba. What’s behind the crisis?

Blackouts have been a regular feature in Cuba for decades. But in recent months, the problem has escalated – lasting longer and occurring more frequently. Here’s a look at the factors driving outages on the island.

Why so many blackouts recently?

In October, millions of Cubans were left in the dark for several days after a major power plant failed. But even as electricity started returning to some areas of the country, it soon went out again when another “total outage” hit the national power grid, according to Cuba’s state-owned Electrical Union. At one point, the grid collapsed four times in a span of 48 hours. Next came two hurricanes in a matter of weeks, knocking out power nationwide once more. Many in western Cuba are still waiting for power to return post-Hurricane Rafael, and some eastern provinces have reported up to 20 hours a day without power this week.

The power plants, built almost entirely in the 1960s and ’70s, burn high-sulfur fuel, which is more damaging to condensers and boilers, says Jorge Piñon, a nonresident fellow at the Energy Institute at the University of Texas at Austin.

Mr. Piñon likens the system to the iconic almendrones, the 1950s-era American-made cars still rolling down Cuban streets. “Just like your automobile, [power plants] need two things: operational maintenance and capital maintenance,” he says. Such maintenance hasn’t happened for decades, which means “the infrastructure is broken, and the only option is short-term Band-Aid solutions” that are increasingly faltering. At this point, “replacing the tires” and expecting to race in the Formula One in this analogy is too late, he says.

How did Cuba get here?

The nation’s electrical system “suffers from the same problem as the rest of the economy: chronic lack of investment,” says Sebastián Arcos, interim director at the Cuban Research Institute at Florida International University. He adds that the government has made investing in tourism and hotel construction a bigger priority in recent years than investing in its grid.

Blackouts occurred regularly in the 1990s after the fall of the Soviet Union, which had bolstered Cuba’s economy. In 1999, when Hugo Chávez rose to power in Venezuela, his government took care of providing fuel to Cuba at preferential prices, and the blackouts dissipated. But even as the quantity of oil imports has fallen for cash-strapped Cuba, “Now it’s not a question of fuel but generating capacity. The plants are crumbling,” says Mr. Arcos.

The U.S. embargo, now over 60 years old, also plays a role. It has limited who can trade with or invest in Cuba and how. It’s where Cuba’s government places the blame for the blackouts – and for most other economic issues haunting the island.

Although Prime Minister Manuel Marrero said in October that the main factors affecting electricity generation are “the state of the infrastructure, the lack of fuel, and the increase in demand,” President Miguel Díaz-Canel was more blunt. The main cause is the “economic war” and the “financial and energy persecution of the United States” against Cuba, he said, adding that it is “difficult to import fuel and other necessary resources for the industry.”

Many observers suspect that the grid situation could become more difficult under the new leadership of President-elect Donald Trump, who during his first term redesignated Cuba as a “state sponsor of terrorism” and reintroduced travel and business restrictions that had been lifted under the Obama administration.

How are Cubans managing?

Electricity failure affects access to clean water and the ability to store food. Cubans are already living through an economic crisis that has impacted the cost of basic goods, and the loss of precious food due to blackouts has left them scrambling.

Some street protests broke out over the recent blackouts, with the Cuban government announcing arrests in early November. But demonstrations haven’t grown to the level of July 2021, when Cuba saw some of the biggest protests – and government crackdowns – in decades over food shortages and postpandemic economic frustrations. Hundreds of people were jailed, making many Cubans fearful of protesting again, says Mr. Arcos.

Are other sources of power possible?

The grid’s problems present new opportunities, says Korey Silverman-Roati, a senior fellow at the Sabin Center for Climate Change Law at Columbia University. He co-authored a report on Cuba’s energy system, and the findings include the potential to capitalize on solar and wind power.

Although Cuba has acknowledged an interest in moving toward renewable energy, few – if any – notable strides have been made. And yet, solar energy could be distributed to the grid “in a way that doesn’t require revamping the entire transmission and generation infrastructure,” Mr. Silverman-Roati notes. “There are opportunities for renewables to plug in.”

In the race to attract students, historically Black colleges sprint out front

Declining enrollment is an issue at many campuses in the U.S. But historically Black colleges and universities have reason to revel, as some have seen record increases. What’s behind their success?

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

U.S. colleges and universities have faced a number of challenges in recent years, such as fewer students and the rocky rollout of the revamped Free Application for Federal Student Aid. Last year’s U.S. Supreme Court’s decision to ban affirmative action on campuses also changed admissions.

Freshman enrollment declined at colleges for the first time since 2020, with a 5% drop in first-year students. But the number of applicants and first-year students at historically Black colleges and universities offers a different picture. In North Carolina for example, some HBCUs are seeing increases of 20% or more in freshman classes. North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University, the largest HBCU in the country, has experienced gains for the past 11 years.

Students are attracted to the schools because of a sense of community and the freedom to be themselves, experts say – especially in the wake of the 2020 murder of George Floyd. HBCUs are also being intentional about the experiences they offer.

During homecoming season, North Carolina Central University sophomore Autumn King had already attended a talent show, the school’s coronation ball, and a gospel concert.

“I really enjoy going to things in general,” she says, “because I have a lot of family history at this school.”

In the race to attract students, historically Black colleges sprint out front

By the last Friday in October, North Carolina Central University sophomore Autumn King had attended a talent show, the school’s coronation ball, and a gospel concert – all in a matter of days. That evening, she was preparing to attend a fraternity and sorority step show in the basketball gymnasium.

October and early November are the most glorious time of the year at historically Black colleges and universities: homecoming season.

“I really enjoy going to things in general, because I have a lot of family history at this school,” says the apparel design major, originally from Charlottesville, Virginia, while at lunch with her friends on campus. “It’s just nice being around people and I wanted to be involved more than I was last year.”

Ms. King was one of tens of thousands of Black students at HBCUs reveling in the annual tradition. Her school, like many others, saw a record number of first-time enrollees for the class of 2028.

Statistics like that have HBCU admissions staffs reveling, too. The past few years have brought challenges to enrollment at colleges and universities in the United States. They have dealt with hurdles such as the rocky rollout of the revamped Free Application for Federal Student Aid. The U.S. Supreme Court’s decision to ban affirmative action in higher education also threw them a curveball in how admissions are conducted. And a declining birth rate starting with the Great Recession means there are simply fewer college-age Americans, something that has been characterized as a demographic cliff.

Freshman enrollment in college has declined for the first time since 2020, with a 5% drop in first-year students, according to the nonprofit National Student Clearinghouse Research Center. After the end of affirmative action, some U.S. campuses are showing a decline in Black and Latino students, as well. But the number of applicants and freshman class members at HBCUs offers a different picture.

“I would attribute several things to the increased enrollment, record admission totals, and increased attention at HBCUs,” says Nadrea Njoku, assistant vice president of the Frederick D. Patterson Research Institute at the United Negro College Fund. Potential students and their parents witnessed the racial reckoning that happened in the U.S. during the pandemic, she says, when George Floyd was murdered by a police officer and Breonna Taylor was killed in a police raid.

On the heels of those tragedies, some schools experienced record donations and philanthropy, which propelled research and construction. Record federal investment in HBCUs, including pandemic aid, has totaled more than $17 billion since 2021.

“Many students and their parents turned their attention to the safe spaces that HBCUs have always declared themselves to be and have proven themselves to be,” Dr. Njoku says. She adds that HBCUs are safe for interpersonal dynamics and social development, and that if marginalizing experiences happen, they don’t happen through racial objectification and exploitation.

Finding a home in North Carolina

North Carolina has the largest number of HBCU students in a single state. According to the National Center for Education Statistics, total enrollment for all 10 of North Carolina’s HBCUs was just under 40,000 students in the academic year 2022-2023. Since then, some of those schools have experienced gains. In fact, North Carolina Agricultural and Technical (A&T) State University, the largest HBCU in the United States, has experienced gains for the past 11 years.

Shaw University, located in Raleigh, reported a 36% increase in new students, which was its largest freshman class since the pandemic. North Carolina Central University welcomed 1,753 new students, the largest freshman class in its 114-year history. Elizabeth City State University also reported a 23% increase in first-time freshmen, while North Carolina A&T saw more than 47,000 applicants. Fayetteville State also saw enrollment increases, which included transfer and military students.

This coincides with other well-known HBCUs like Howard, Clark Atlanta, and Morehouse College, which also experienced record applications or first-year enrollments – or both – for the class of 2028.

“The bottom line is that these enrollment numbers have been trending upward since the unfortunate incidents with George Floyd and Breonna Taylor, which put a big spotlight on the inequities that exist in underserved communities where African Americans are having to live,” says Harry Williams, president of the Thurgood Marshall College Fund.

After that, Americans were looking for organizations and institutions that “were designed to lift people up and elevate. And HBCUs have been doing that for 150 years,” Dr. Williams adds. He says the changes to affirmative action are one of many factors in the current enrollment trend. “What we’re seeing, I don’t want to attribute directly to the Supreme Court, because I think it’s something that has been evolving.”

The 2023 high court decision potentially caused students to think about where the best places for them to thrive could be, suggests Dr. Njoku. She points to the upward social and economic mobility of HBCUs, which surpasses the Ivy League for Black students. She also notes that social media has made HBCU culture more accessible to curious students, who then don’t have to visit every campus.

What are HBCUs doing to attract students?

North Carolina A&T accomplished its enrollment and application gains by planning ahead, says Joseph Montgomery, the school’s associate vice provost for enrollment management. In 2011, the university released its “Preeminence 2020” plan, which tackled growing enrollment and strengthening the academic portfolio. That led to two more iterations of the plan, with the latest forecasting until 2030. Four construction projects on campus, including a dormitory with 405 beds, will be complete in two years.

“Schools have to recognize that you’re in the moment,” Mr. Montgomery says. “So we can sit back and become what I like to call benefactors of the moment,” he continues.

Specifically, HBCUs have to band together, Mr. Montgomery says. “How can we have the moment live beyond whatever its shelf life is?”

For him, he keeps in touch with enrollment officers at other HBCUs, and they share information and ideas. For instance, he says that they are all common application schools, so North Carolina A&T and other HBCUs have consortium travel – meaning they visit urban areas to recruit together. Mr. Montgomery says some HBCUs are also traveling with highly selective predominantly white institutions.

“There’s combinations of Howard University, Harvard, and Princeton, and Yale traveling together. And so we’re like, if Howard can get those schools, then could there be a combination of A&T and MIT and Cal Tech?” Mr. Montgomery asks.

He says that schools should be careful about the influx of students and make sure that in the long run, they can accommodate them. Schools have negotiated contracts to feed a certain number of students, and have capacity to house a certain number. Going over on either of those calls for renegotiating contracts or having to outsource things like housing, which, depending on the location of the arrangement, might call for shuttle services. All of that adds to the total costs, Mr. Montgomery says.

“That throws the budget off,” he adds. “Everybody thinks that if you get more students you make more money, but it’s not always the case, because your expenditures can start exceeding the money that you’re bringing in.”

“A natural community builder”

On the day of Howard University’s homecoming game against Tennessee State University last month, musings were that Vice President Kamala Harris, a Howard graduate, would make an appearance. Ms. Harris didn’t show up, but she did write a letter to the student newspaper, The Hilltop, wishing her fellow Bison a happy homecoming. They wore school paraphernalia and sweaters and shirts with her name on them as her picture loomed high on light poles. Students and alumni packed the streets and the campus during the 100th anniversary of the school’s homecoming, doing line dances, eating food, watching the game on a jumbo screen – while small children played in bouncy houses.

“I think homecoming is a natural community builder, but it’s also a community extender,” Dr. Njoku says. She likens it to being a lifetime commitment between HBCUs and their graduates, who share professional networks and affinities for their schools. “You feel like there’s an unspoken connection.”

Podcast

Our food writer serves up a holiday’s history and hits

There are the skirmishes over fresh cranberries or canned, turkey or tofu. There may be conflicting opinions about aspects of the first-Thanksgiving story or the latest political news. But from food culture’s evolution to shifting family dynamics, it all works best when gratitude gets its seat at the table.

Whether American Thanksgiving makes you think of a Norman Rockwell-style family tableau or of a small gathering of friends, it probably features some special food.

The Monitor’s Kendra Nordin Beato has it covered – literally, as a writer, and also as an accomplished cook.

“My husband’s going to be in charge of the turkey,” Kendra says on our “Why We Wrote This” podcast. “I know that we’ll have fresh cranberry relish. ... But my favorite thing ... is roasting Brussels sprouts with walnuts, and then you top it with maple syrup and dried figs, and then a little bit of Parmesan cheese.”

Kendra has made a study of American culinary traditions. She riffs authoritatively about the cultural evolution of dishes, about pumpkin versus sweet potato pie, about traditions colored by myths, about evolving family roles, and about remembering what matters most. At her table, guests of all ages like to name things for which they’re grateful.

“This has become our one tradition that we do in kind of a shifting world,” Kendra says. “Gratitude is really the best ingredient at the Thanksgiving table.” – Clayton Collins and Mackenzie Farkus

Find links to stories and a show transcript here.

A Chatty Thanksgiving Primer

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Of dogs and din

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

Amid the stress and strain over America’s presidential campaign, you may have missed a novel exercise in grassroots democracy. Boston’s Seaport neighborhood held a local election in early November. It had all the ticks of modern politics – a crowded primary, social media trolling, outside influence, allegations of voter fraud, even ballot bots.

In the end, the election officials made a tough call: The five top candidates for dog mayor – doodles Aspen and Lady, golden retrievers Bennett and Macie, and a Maltipoo called Rhubarb (Rhu for short) – would just have to share power.

“It was really clear that we were in it for the fun and just bringing joy to people at a time where people are really stressed and tensions are really high because of the real election,” said Rhu’s owner, Scarlet de Lemeny.

Seaport’s “Bark the Vote” exemplified how some communities are trying to dissolve divisions through a variety of activities that bring people together, and that offer models about the essentials of self-governance, such as trust, respect, and civility.

Such civic activities help enhance traits like civility. They also help counter one cause of today’s public discord: loneliness, or, rather, the isolation and anger associated with loneliness.

Of dogs and din

Amid the stress and strain over America’s presidential campaign, you may have missed a novel exercise in grassroots democracy. Boston’s Seaport neighborhood held a local election in early November. It had all the ticks of modern politics – a crowded primary, social media trolling, outside influence, allegations of voter fraud, even ballot bots.

In the end, the election officials made a tough call: The five top candidates for dog mayor – doodles Aspen and Lady, golden retrievers Bennett and Macie, and a Maltipoo called Rhubarb (Rhu for short) – would just have to share power.

“It was really clear that we were in it for the fun and just bringing joy to people at a time where people are really stressed and tensions are really high because of the real election,” Rhu’s owner, Scarlet de Lemeny, told The Berkeley Beacon, Emerson College’s student news site.

Seaport’s “Bark the Vote” exemplified how some communities are trying to dissolve divisions through a variety of activities that bring people together, and that offer models – even via four-legged creatures – about the essentials of self-governance, such as trust, respect, and civility.

Such civic activities help enhance traits like civility. They also help counter one cause of today’s public discord: loneliness, or, rather, the isolation and anger associated with loneliness. In many communities, such as California’s San Mateo County, loneliness is now officially recognized as a public health emergency.

The yearning for connection has diverse measurements. A YouGov poll conducted for The Washington Post in April found that younger people are among the top users of public libraries – people who visit them at least once a month. One big draw is social contact. “Going to the library is a decent signal of your broader engagement with society,” the Post reported.

That dovetails with studies showing Generation Z is outpacing older generations in philanthropic giving in early adult life. Gen Zers’ instinct for connection, molded and expanded by social media, has also instilled generosity. A broad survey by the Christian research group Barna found that nearly half of all members of Gen Z in the United States view supporting others as a higher motive for having money than pursuing their own individual passions.

Few things bring people together more than dogs. A growing number of churches are turning their open grounds into dog parks for the public to help draw people closer to their neighbors. It’s changing local politics, too. In October, the city of Richmond, Virginia, stepped in to help a local church keep its dog park open by leasing the property and paying the insurance. Church members manage the park as volunteers.

During the election in Boston’s Seaport, many of the dog owners refused to be riled by online bullies. In posted comments, Justine Kim (owner of Lady) praised Madilyn Emerson (owner of Macie) for her “integrity and honesty.” While the event’s social media buzzed with ugly accusations, friendships grew leash by jowl. “The initiative was meant to spread kindness and positivity,” its organizers said.

To anyone worried that democracy is going to the dogs, take heart. For many communities, amid the clamor and contest of politics, there is far more that draws people together than drives them apart.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Can we? Yes – it’s wonderfully true.

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 4 Min. )

-

By Keith Wommack

We all have the God-given ability to accomplish what we rightfully need to do.

Can we? Yes – it’s wonderfully true.

I was in the woods, squinting at 3-by-5 cards in the moonlight, attempting to familiarize myself with a speech about God, our true spiritual nature, and the profound effect prayer can have on mental and physical health. I had two days to get the speech down, while also serving as an assistant scoutmaster at my stepsons’ Boy Scout campout. I could remember half the talk, but the rest just wouldn’t stick.

All the boys were supposed to be in their tents, sleeping, but suddenly here was one of the scouts. I’ll call him Ethan. He walked up and grabbed the cards out of my hand. He said, “I’ll help!”

My heart sank. Tired, frustrated ... and now Ethan. He wouldn’t give the cards back and started pacing with me. As we paced, though, things changed. He gave hints that forced me to think deeply. The rest of the speech began to come to thought more easily.

As we worked, he remarked, “This is neat stuff.” Then he sat down on a stump and asked, “Don’t you think that the same God that gave you the ideas for this speech also gave you the ability to share it?”

“Ethan the problem” had turned into what we might call “Ethan the angel.” His words woke me up. I had that speech down before we left the campsite. And I gave that talk many times throughout North America.

Mary Baker Eddy, the founder of Christian Science, defines “angels” as “God’s thoughts passing to man; spiritual intuitions, pure and perfect; the inspiration of goodness, purity, and immortality, counteracting all evil, sensuality, and mortality” (“Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” p. 581). Angels are not people, but Ethan did express, that night, helpful or angelic qualities as he assisted me.

Whatever is required of us, we reflect God’s ability to do. Why? Because we are created in God’s image and likeness. We are not the lost, scared, and frustrated mortals we sometimes appear to be. Spirit, God, is All – all-good, true substance, and Life – including our true spiritual, immortal existence. God is the divine Life we individually reflect. He is our Mind, and we are His complete, fearless, spiritual likeness.

Spirit impels constant spiritual vitality and confidence, so Spirit’s allness, understood, empowers us to declare regarding discouragement, “That’s not me! That’s not you! Never has been.”

Our God-given spiritual sense – “a conscious, constant capacity to understand God” (Science and Health, p. 209) – enables us to accomplish what’s needed, when it’s needed. And angels, spiritual intuitions, help awaken us to our natural abilities.

Our true spiritual nature perfectly reflects our divine Father-Mother, God. When describing his ability to do God’s will, Jesus said, “The Son can do nothing of himself, but what he seeth the Father do: for what things soever he doeth, these also doeth the Son likewise” (John 5:19).

Whether we desire to lay aside shyness, pain, frustration, brokenness, lack, or any other limitation, we can turn to our Father-Mother in prayer and allow His angels to lead us out of limited, materialistic thought patterns, which are fertile ground for difficulties.

Evil, the erroneous belief in a power besides God, suggests that God’s child, His expression, is at times incapable and deficient. However, because God is our Life and Mind, we express Mind’s intelligence and are blessed by Life’s infinite capabilities and opportunities. And nothing can restrict or stop God’s work.

Jesus, filled with the Christ-power, Truth’s divine might, revealed for all of us how to overcome every deficiency or obstruction that evil suggests. Hatred toward him, which led to the cross and tomb, could not limit God’s Son. He proved evil to be unreal. He accomplished this by laying aside the belief that life is mortal and limited. He completely loved, understood, and expressed the dynamic, eternal, infinite Spirit, God.

For each of us, the understanding that all things are possible to God, and therefore to us as His offspring, is gained through studying the Bible, which teaches the absolutely reliable nature of Spirit. This scriptural study is aided by also studying Science and Health, which opens up the spiritual meaning of the Bible, helping us grow Spiritward. As we grow in this way and express selfless grace, nothing can prevent us from reflecting Him. We are all His sons and daughters.

Whether in the woods or out of them, we can accomplish what’s needed. It’s wonderfully true: “I can do all things through Christ which strengtheneth me” (Philippians 4:13).

Adapted from an editorial published in the Nov. 4, 2024, issue of the Christian Science Sentinel.

Viewfinder

Making a mark on the field

A look ahead

Thank you for joining us today, and this past week. On Monday, you can look for our reports on the increasingly energized pro-settlements movement in Israel, and on President-elect Donald Trump’s nominee for U.S. secretary of state, former Sen. Marco Rubio.