- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usMonitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Monitor Daily Intro for June 5, 2017

Mark Sappenfield

Mark Sappenfield

When anti-fascist left-wing extremists showed up in Portland, Ore., Sunday to counter a “Donald Trump free speech protest” by right-wing extremists, both sides were ready for a fight. One picture of what police confiscated included bricks, knives, hammers, clubs, a wrench, a hatchet, and tear gas. While most Americans might condemn such an approach to protest, the national conversation of today is often little more civilized than a set of brass knuckles. The Portland Police cache is not unrelated to that broader trend.

But there was no large-scale violence, and there was a different snapshot, too. One pro-Trump protester spent most of the day sitting amid the left-wingers, not hurling bricks but asking honest questions. The protester told The Oregonian newspaper that he likes to keep an open mind, trying to change people’s opinions and seeing if they can change his.

“There [were] a lot more intelligent people than I thought,” he said. A liberal protester acknowledged: “You certainly have humanized a fair number of your allies.”

That was a very different kind of conversation.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Responding to terrorism: how communities overcome fear

The London attacks Saturday left the world with a familiar question: How to move forward after terror. Many of our staff have seen this unfold firsthand as they have reported around the world. We asked them to share their stories about how cities have healed before.

-

Scott Peterson Staff writer

-

Christa Case Bryant Staff writer

What’s the best way to respond to terrorism and the fear it tries to instill? That’s a question we, as foreign correspondents for the Monitor, have asked ourselves – and watched civilians grapple with, from Jerusalem to Istanbul to Paris. “The purpose of its perpetrators is to frighten you, terrorize you, and try to make you change the way you live your life,” says Scott Peterson, who has reported from war zones all over the world and was in London when Saturday’s attack occurred. What we’ve found is that humor, faith, and unity have helped communities emerge resilient – if also more alert. As politicians or media have propagated fear amid a rising number of attacks in recent years, Europeans have countered it with their best jokes. They’ve also shown communal strength, as in Parisians’ “Tous au Bistro” (Everyone to the Bistro), refusing to change their lifestyles out of fear. And in Jerusalem, many find solace in faith, such as a yeshiva student who told Christa Case Bryant after an attack: “We turn to prayer as our comforter.”

Responding to terrorism: how communities overcome fear

What’s the best way to respond to terrorism and the fear it tries to instill? As foreign correspondents for the Monitor with more than 40 years’ experience between us, that’s a question we’ve asked ourselves – and watched civilians grapple with, from Jerusalem to Istanbul to Paris.

“The purpose of its perpetrators is to frighten you, terrorize you, and try to make you change the way you live your life,” says Scott, who has reported from war zones all over the world and was in London Saturday night, when a trio of men rammed their van into pedestrians on London Bridge and then went on a knife-wielding rampage through a popular nightlife area nearby, killing seven and leaving nearly two dozen in critical condition.

What we’ve found is that humor, faith, and unity have helped communities emerge resilient – if also more alert. And we’re already seeing signs of that from London, from hotels opening up spare rooms to those stranded by the attack to residents putting up posters that read, “Dare to keep on loving.”

There’s been some talk in London about whether to delay the election scheduled for later this week. But in a reflection of Londoners’ defiant standing up to these attackers, we saw a tweet to the effect that the last time the United Kingdom delayed an election, the Germans were poised to attack England.

“We will never let these cowards win, and we will never be cowed by terrorism,” tweeted London’s mayor, Sadiq Khan. In an opinion piece for the Evening Standard, Mayor Khan – a self-described “proud and patriotic” British Muslim – denounced the perpetrators’ “sick and wicked ideology” and added, “They cannot win if we don’t let them…. That’s why Thursday’s general election will go ahead as planned, because to postpone it would be to play into the hands of those who want to undermine our democracy.”

Very dangerous couscous!

Since the Bataclan attack in Paris in November 2015, which marked the start of a series of attacks inspired by the so-called Islamic State across Europe, one of the defining reactions has been humor. As politicians or media reports have propagated fear – intentionally or unwittingly – residents across Europe have countered with their best jokes.

After Fox News did a television report about “no-go zones” in Paris after the terrorist attack on the Bataclan, describing dangerous, Muslim-only communities of impunity, Sara says, "those of us living in Paris and reporting in some of those neighborhoods scratched our heads because it didn’t match up with the Paris we know."

So when a television comedy show aired a satire of two on-air reporters at the scene of an imaginary “no-go zone,” Sara says it felt like a collective statement that helped knit people together who might not usually laugh at the same jokes. “Oh … couscous!” one of the “reporters” reacted, as the headline COUSCOUS ATTACK IN PARIS appeared on the screen. “Very dangerous couscous in Paris.”

Yesterday, as CNN reported quiet streets on Sunday morning, a man who goes by @Scottieboy shot back with British wit on Twitter: “Woman on CNN talking about London’s streets being eerily quiet. Mate, it’s Sunday. They’re not cowering in fear, they’re having a lie in.” (A lie-in is a Britishism for sleeping in.)

And when Sara was in Brussels reporting during a citywide lockdown, as authorities hunted for a ringleader of the Paris attack and asked residents not to report on their movements, Belgians took to social media with pictures of cats instead, in every variety of pose.

It’s just one sign of the communal strength that has emerged in the past 2-1/2 years – some of it organized, most of it organic. After the attack on the Paris-based satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo in January 2015, 44 global leaders linked arms and marched down a main boulevard of Paris, right in front of Sara’s house. It’s left an enduring impression, reminding her, “We are in this all together.”

After the attack on the Bataclan, a soccer stadium, and cafes around Paris less than a year later, Parisians organized “Tous au Bistro,” or everyone to the bistro – refusing to change their lifestyles out of fear.

That defiance was best captured this weekend by Richard Angell, a patron in the restaurant in Borough Market that was attacked over the weekend. He returned on Sunday to pay his bill as well as give a much deserved tip to the staff, he told media.

Empathy and faith

To be sure, some Londoners are shaken by the uptick in attacks in their city, which until now had been relatively free from terrorism since the 7/7 attacks in 2005. But even as those concerns are addressed and officials take concrete steps to crack down on extremist activities, it’s important to not let fears exaggerate the scope of the problem.

“There’s a danger of focusing on and being too obsessed with the visceral imagery of the attack or killings or bombing without putting it in a broader context,” says Scott, a foreign correspondent since 1989 and also a professional photographer. “Often what gets lost in that very, very focused view, which can appear overwhelming, is that 99.999 percent of the human beings in that town or city went about their daily lives perfectly normally, perfectly safely that day.”

On the other hand, dealing with terrorist attacks closer to home can inspire greater empathy for Middle Eastern cities that have been dealing with terrorism on a far greater scale for years.

“I have heard some of my British friends, who have a good understanding of certain communities in the Middle East say, ‘Wow, now we’re beginning to get a small taste of what it must be like to be in Baghdad or Yemen or Syria or Afghanistan – so many places in the Middle East where you have substantial attacks that are aimed at civilians and are measured by the dozen, or even 100s of deaths, if they’re really big,” says Scott. “We often forget what kind of stress those people are under on a day-to-day basis because they’ve been under those stresses for years.”

While religion is often blamed as a catalyst for this region’s conflicts, it can also be a solace for those affected by violence.

“If we trust God and everything is in His hands, we don’t have to worry about it,” a young yeshiva student told Christa amid an uptick in attacks against Israelis in 2014 – almost the same words that a Muslim mother had shared with her the week before after her son was killed. “We just turn to prayer as our comforter.”

During the same spate of violence, Christa showed up at a synagogue in West Jerusalem, where Palestinians had killed four rabbis at prayer the morning before, to find a young father and mother emerging with their infant son.

Despite the attack, they had gone forward with the traditional circumcision ceremony they had planned to hold there. “We decided to do it today to show we’re not running away,” said the father, posing with his wife and son for photos with bullet holes and policemen in the background.

“This whole thing of rebirth is a constant in the Jewish history,” the baby’s grandfather, Yosef Sorotzkin, told Christa. “It’s in our belief, culture, religion, that we push forward.”

Share this article

Link copied.

Can nations find unity on protecting the seas?

Big environmental conferences can seem a dime a dozen these days. One this week in New York highlights new threats to oceans, but it also shows how these events are often about more than just gauzy mission statements. They can be engines of innovation.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Leaders from 193 nations convene in New York this week for the United Nations’ first Ocean Conference. Advocates hope the conference will be a fruitful forum for important policy changes and announcements about protected zones or other significant measures. But, perhaps equally important, is the summit’s potential to raise awareness of the challenges facing the world’s oceans – and the measures to address them that have already shown promise, staff writer Amanda Paulson reports. Organizations will be sharing ideas and solutions, both big and small. In Fiji, for instance, the tiny subsistence fishing village of Ucunivanua (pop. 338) became a model for rebuilding depleted fish stocks for nearly 500 villages. Since, 20 other countries have successfully adopted a similar model. As Jamison Ervin, manager of the UN’s Nature for Development program, puts it, “These appear to be local, artisanal, boutique, but when you start to advocate for them, you realize how much power they have.”

Can nations find unity on protecting the seas?

Depending who you talk to – and which threat you’re discussing – the challenges facing Earth’s oceans are either among the most daunting or the most solvable.

Overfishing and depleted fish stocks? The answers are relatively clear, and in many places, we’re already headed in the right direction.

Marine pollution and plastics? Trickier, and we’re farther from enacting solutions.

Warming seas and increased acidification? Complex, daunting, and impossible to solve without addressing climate change itself.

This week, the United Nations is hosting its first-ever Ocean Conference, dedicated to addressing these and other challenges for the seas. Some 5,000 people – including several heads of state, prime ministers, and other top officials from the 193 UN-participating countries – will converge on New York to share ideas, make voluntary commitments, participate in dialogues, and issue a “call for action.”

Ocean advocates say such a visible and high-level conference is an opportunity to bring attention to a critical and often overlooked conservation issue. But beyond raising awareness, it's also likely to be a forum for important policy changes and announcements about new protected zones or other significant measures.

“Is it the final word? No, but it is a great launching point to move forward with the global community to recognize that the health of the ocean is critical to everyone,” says Karen Sack, managing director of Ocean Unite, an advocacy group for ocean issues.

Oceans, say advocates, are often considered an “orphaned” environmental issue – away from most people, out of our sight, largely outside of national borders. Yet increasingly, scientists are aware of just how much the changes in oceans affect humanity, and buzzwords like “blue economy” – using the sea sustainably – are getting tossed about with increased frequency.

“Every second breath you take comes from ocean-produced oxygen. Without a healthy ocean, we’re in deep trouble. Whether it's food, whether it’s our climate, we have to have integrity for the ocean, the source of life,” said Peter Thomson, president of the UN General Assembly, at a press conference Thursday.

A focus on fisheries

One of the issues getting a lot of attention this week will be fisheries. Fish are a critical food source for much of the world’s population, especially in developing countries, and about 80 percent of the world’s fish stocks are reported as being fished at unsustainable levels. Illegal and unregulated fishing is rampant in many areas.

At the same time, there have been success stories, including a comeback for US fisheries. Scientists say solutions are relatively clear, and fish populations rebound on a short time scale when given a chance to recover.

“The fisheries problem is not a wicked problem,” says Daniel Pauly, a marine biologist and fisheries expert at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, referring to the public-policy term for problems that are impossible to solve.

With decent national fisheries management, stocks can rebound fairly quickly, as they have with some US fish stocks, like mid-Atlantic bluefish, New England scallops, and albacore in the North Atlantic. Since 2000, 41 US fish stocks have been rebuilt, according to the latest report by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

“For the narrowly defined fisheries problem, I’m a potential optimist,” says Pauly. “They’re fixable, and where you decide to fix them, you can fix them.”

What’s needed: scientifically set quotas, protected nursery and spawning habitats, and reduced bycatch (unwanted fish caught unintentionally). “It works anywhere you do it,” says Andy Sharpless, the chief executive of Oceana, a nonprofit that works to protect oceans and combat overfishing. “And in five to 10 years, very often you see big rebounds.”

Small successes bring big gains

While much of the focus at this week’s conference will be on high-profile partnership dialogues and national-scale commitments, many of the voluntary commitments recorded (currently more than 700, with the number expected to rise through the week) are from nonprofits and smaller communities.

And those community-level actions can play an important role in solutions, say experts, particularly when it comes to solutions in developing countries that help protect oceans even as they improve people’s livelihoods and alleviate poverty.

Fiji's first locally managed marine area started in the tiny subsistence fishing village of Ucunivanua, population 338, in 1997. But its success, both in rebuilding depleted fish stocks and in improving local incomes, quickly led to replication, says Jamison Ervin, manager of the United Nations Development Programme’s Nature for Development program.

Nearly 500 villages in Fiji – together managing about 80 percent of the country’s fishing areas – now have similar local management systems, and the model has been replicated in 20 countries.

“This tiny story of how one community conserved an area in one remote area of Fiji is reaching the world,” says Dr. Ervin. Her program is bringing representatives from that project, along with representatives from 13 other communities who have made significant contributions to oceans conservation, to the conference this week, and giving them communications training and a platform to share their stories.

“These appear to be local, artisanal, boutique, but when you start to advocate for them, you realize how much power they have,” says Ervin.

Plastic pollution: A more persistent problem

Still, if the attitude this week is one of optimism and solutions, oceans advocates say that some of the problems the seas are facing are deep-seated and intractable.

Pollution and trash – most of it plastics – is rapidly filling up the oceans, with more than 8 million metric tons of plastic going in each year. Recent photos showed the trash-strewn beaches of a tiny, remote, uninhabited island in the Pacific that has the highest recorded density of trash anywhere in the world. The waste threatens and kills marine mammals, seabirds, turtles, and fish.

Dealing with the issue, say conservationists, will necessitate major changes on the part of both companies and consumers.

And oceans are also one of the parts of the world most intricately linked to climate change: They absorb about 30 percent of human carbon dioxide emissions and the vast majority of the Earth’s excess heat energy. Sea-level rise – threatening numerous coastal cities and communities – is one of the biggest likely consequences of climate change in the coming century. And steadily warming and acidifying waters, both direct results of climate change, are having big effects on marine life and coral reefs, many of which are rapidly dying.

“We can fix overfishing,” says Mr. Sharpless of Oceana. “We can even beat some big polluters. But we have not come up with an independent solution to the damage that is being done to the oceans from climate change.”

Dr. Pauly, the fisheries biologist, also views those challenges as massive and daunting, but says that asking about optimism or pessimism is the wrong way to frame the question.

“We fight against these things not because we know we’re going to win, but because we have no alternative,” he says, citing other seemingly “lost causes,” like the Civil Rights movement or the harm inflicted by Big Tobacco. “One day, if you’re lucky, you win.”

Suburbia as melting pot: making diversity work

Issues of diversity and integration are coming to the surface from the United States to Europe. But a Houston suburb shows how progress needs to be about more than street addresses. It's about forging a different sense of community.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 13 Min. )

Like many cities, Houston remains divided by race and ethnicity, and by wealth and poverty. But its suburbs are rapidly becoming a kaleidoscope in which no majority exists, a sign of where much of America is headed. Nowhere is the transformation more evident than in Pearland, on Houston’s southern edge. Its diversification is largely a result of the inexorable sprawl of this city, where residents keep moving farther out: Houston’s nine-county metropolitan area is larger than Massachusetts. Yet living in the same subdivision doesn’t necessarily mean living together. For old-timers in Pearland who remember a slower pace of life, the influx of newcomers sometimes feels like an intrusion. A gap has already opened up between the younger, multicultural arrivals and the mostly white homeowners near the city’s old center. Underlying the changing sociology of America’s suburbs looms a fundamental question: Does their diversification represent a new kind of integration, or a bunch of groups coexisting side by side in their own enclaves – a tossed salad rather than a melting pot? “We’re not threatened by each other,” says Stephen Klineberg, a sociologist at Rice University in Houston. “But we also don’t get to know each other.”

Suburbia as melting pot: making diversity work

The sun has already set by the time Quentin Wiltz – oil industry executive and political candidate – approaches the last ranch house in a subdivision of this Houston suburb. A Latino man stands on his front lawn, a hose at his feet. In the fading light, he has the glazed look of someone relieved to be home from work.

Mr. Wiltz, an African-American in gray slacks and a green polo shirt, goes into his spiel: I’m running for mayor and I’d like your support. The homeowner, Efren Lara, says he didn’t know there was an election coming up. Wiltz edges in closer and reminds him when polling stations will be open. “What time can you make it?” he asks, pressing the man to vote. Mr. Lara says he works long hours at an Exxon refinery. Wiltz, who works for a company that makes pipelines, smiles and raises an arm. “Ah! You’re in the downstream and I’m in the upstream,” he says.

“We want to make some changes, OK?” Wiltz adds, talking about what he’d do as mayor. He takes down Lara’s phone number, then waves goodbye.

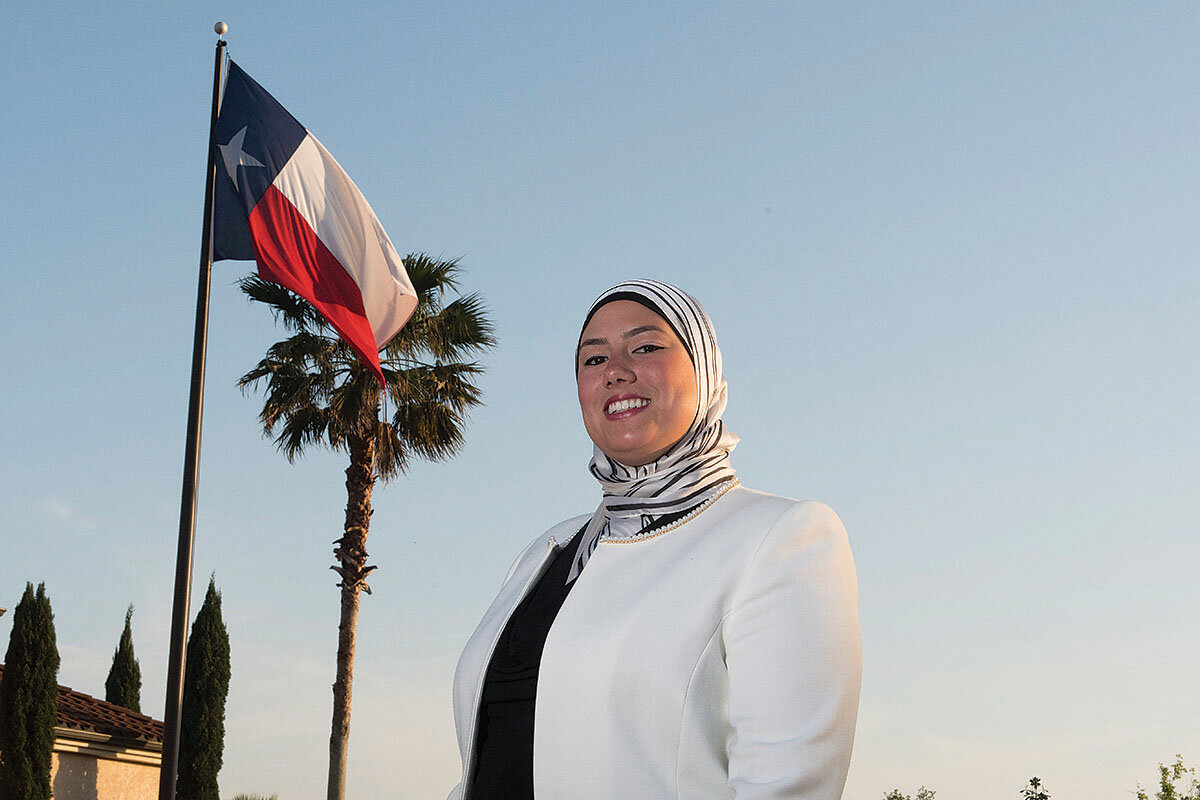

Two miles west, in a newer subdivision of brick facades and double garages, Dalia Kasseb rings another doorbell, pamphlets in hand. Ms. Kasseb, an Egyptian-born pharmacist, wears a patterned blue headscarf and carries a yellow Coach purse over her shoulder. A middle-aged black woman opens the door; three young kids spill out onto the lawn. “Hi! I’m running for city council to be a voice for all,” Kasseb begins. Then she launches into her political pitch.

Both the candidates and the residents they are wooing symbolize the new face of suburban Texas – and, to a certain extent, the rest of the United States. Once synonymous with middle-class whites, suburbs are now becoming America’s new melting pots. From Atlanta to Sacramento, suburban communities are rapidly diversifying as families of all different racial and ethnic groups move in search of better schools and their version of a white-picket-fence lifestyle.

While diversity has long been written into the code of cities, suburbs are now challenging them as the new source of social and ethnic dynamism. Indeed, between 2000 and 2010, nonwhites accounted for nearly all of the suburban population growth in 78 of the top 100 cities, according to William Frey, a demographer at the Brookings Institution in Washington. Today more Latinos and African-Americans live in suburbs than in urban cores.

“Suburbs are changing very rapidly in terms of their racial and ethnic composition – and their affluence,” says Daniel Lichter, director of the Institute for the Social Sciences at Cornell University in Ithaca, N.Y.

Like many cities, Houston remains divided by race and ethnicity, and by wealth and poverty. But its middle-income suburbs are rapidly becoming a kaleidoscope in which no majority exists, a sign of where much of America is headed. (Texas, like California, is a majority-minority state.)

Nowhere is the transformation more evident than in Pearland, a dumbbell-shaped suburb on Houston’s southern edge. Its diversification is largely a result of the inexorable sprawl of this city, where residents keep moving farther out in search of lower-density living. Houston’s nine-county metropolitan area is larger than Massachusetts.

In 2000, Pearland had a population of 37,600. Today, it is the country’s eighth fastest-growing city, with 120,000 people. Along with the growth has come a reversal from a majority-white community to one where newcomers look more like Wiltz and Kasseb than the incumbents they are challenging.

Yet living in the same subdivision doesn’t necessarily mean living together. For old-timers in Pearland who remember a slower pace of life, the diversity and influx of newcomers sometimes feels like an intrusion. A gap has already opened up between the younger, multicultural new arrivals and the mostly white homeowners near the city’s old center.

Underlying the changing sociology – and politics – of America’s suburbs looms a fundamental question: Does their diversification represent a new kind of integration, or just a bunch of diverse groups coexisting side by side in their own enclaves – a tossed salad rather than a melting pot?

“We’re not threatened by each other,” says Stephen Klineberg, a sociologist at Rice University in Houston, of the area’s new diversity. “But we also don’t get to know each other.”

Pears are no longer farmed in Pearland, but horses and cattle still graze behind the housing subdivisions named for the ranches they replaced. The town was founded in 1892 by a Polish aristocrat who bought 2,560 acres of land near a railroad junction. Pearland slowly filled up with farming families, built schools and roads, and diversified into growing figs and rice. Oil derricks bobbed nearby. By 1960, a year after its incorporation, it had 1,497 residents.

Mayor Tom Reid, a World War II Navy pilot, moved to Pearland in 1965. He wanted to be closer to his work as project manager at the Johnson Space Center, 12 miles down what was then a country road. “I could go to work and my wife would say, ‘How was the drive?’ I’d say, ‘I saw a couple of guys and we waved to each other,’ ” he says.

The proximity to the Space Center attracted other aerospace families, and Pearland began to build better roads and sewer lines, anticipating future growth. Then in the 1990s, as Houston’s oil economy revved up, Pearland’s population doubled. The expansion of State Highway 288, a six-lane road to Houston, opened up the community to commuters, and new housing projects spread across the landscape.

Part of Pearland’s growth, like that of many suburbs, is rooted in the perennial movement of people out of city cores. For all the hype of an urban renaissance, Americans continue to migrate to the low-density suburbs of car-dependent urban areas. Rich and childless whites cling to city centers, as do many new immigrants. But young families move outward where housing is cheaper and schools are often better.

As they do, they bring more diversity to suburbia, since nonwhite minorities now make up 44 percent of Americans ages 18 to 34. For African-Americans, a suburban home is a choice that their parents and grandparents were frequently denied. For immigrant families from Asia, spacious suburbs are among the reasons they moved to the US.

Not all suburbs are seeing racial mixing – or embracing the trend. Demographers point to a new form of “white flight” as older white families leave behind multicultural cities and suburbs for new exurbs, particularly in areas between the two coasts. “You can have increasing diversity and increasing segregation at the same time,” says Richard Wright, a geographer at Dartmouth College in Hanover, N.H.

From 1990 to 2010, Pearland went from being one of Houston’s most homogeneous suburbs to its second most diverse, a city where whites are outnumbered by Latinos, African-Americans, Asians, and other minorities. As many as 75 languages are now spoken in local schools.

“It’s a very dynamic and diverse place,” says Clay Pearson, the city manager, who moved here from Michigan in 2014. “At some level, you realize that’s part of the now and the future. For myself and a lot of people I’ve talked to, that’s an attraction.”

Mayor Reid is now 91. His office at City Hall, near the old center, faces west toward the newer subdivisions, past a tangle of traffic. Framed pictures from NASA space missions line his wall. In the corner stands a gleaming chrome shovel, a reminder that his job as mayor – a near-unbroken run since 1978 – is largely ceremonial; Mr. Pearson is the chief executive. Being mayor is also a part-time job, though Reid, who has crisp white hair, blue eyes, and jug ears, says he usually puts in a full workweek, even while he’s running for reelection.

“I’m retired and I’m doing something I love,” he says, switching into campaign mode. “My job is building a city, and I’m not through yet.”

As the demographics of many suburbs change, their politics are shifting, too – though often more slowly and subtly. Many suburban communities, including Pearland, are seeing more diverse slates of candidates run for local offices and new issues surface.

Yet traditional voting patterns endure. It’s often easier to target and win over diligent retirement-age voters than it is to woo new families with frenetic schedules. That’s why, on a midweek evening, Wiltz and Kasseb join other candidates who sit behind four trestle tables in a carpeted events room at a residential clubhouse for “active adults.” A scattering of older men and women, all white, fill three rows of seats. At the front sits Wiltz’s wife, Monique, and his eldest son. Kasseb’s husband sits facing her.

The rest of the lineup – Reid and eight candidates for council seats – are white. Only one of them is a woman.

Wiltz, dressed in a jacket and striped tie, sits next to Reid, who is all smiles as they shake hands. It’s the first meeting between the two since Wiltz told the mayor in January that he was running against him, after two unsuccessful bids for city council. When Wiltz gets to his feet, after Reid’s opening remarks, he holds up a finger and turns to the moderator.

“I want to clarify one thing,” he says. “Mayor Reid is not an opponent, he’s a friend.” (Reid, cast as Caesar, stares at his Brutus, impassively.)

Wiltz, who is in his mid-30s, grew up in Louisiana and attended a historically black college in Baton Rouge. He tells the forum that after he moved to Pearland in 2007, Reid wrote a recommendation letter for him to join the parks board. “And that’s where my career in service leadership started,” he says.

Then he pivots to his campaign themes: improving transportation, creating jobs, listening to residents. “I just want to provide new ideas and leadership for where we want to be and the city we want to become,” he says. “Thank you.”

Other candidates talk about their careers, their families, their ties to Pearland. What passes for policy debate is the stuff of municipal governance, from traffic snarls to flood drainage. Kasseb talks about “smart growth” and people staying healthy and having more parks.

Only one candidate, Jude Smith, a lawyer running for a council seat, speaks directly about the demographic changes. He moved to Houston three years ago with his wife, a doctor, who is Indian. “We looked around Pearland and saw people of every color from almost every country in the world,” he says. “That’s what I want to be a part of.”

After the speeches, a middle-aged woman stands up and identifies herself as a resident on the newer west side. “I see two cities here,” she says. “And because you represent the city, how are you going to draw these two parts together that have nothing to do with each other right now?”

Reid then launches into an explanation of how he solves problems by listening to all sides. “Some people have a fixed mind on a particular issue and don’t want to consider any other alternative,” he says.

Wiltz is back on his feet. “I like to walk,” he says, pacing toward the front row. He pauses.

The divide is real, he tells the woman, noting that he lives in what he prefers to call “the historic district.” What’s missing now is engagement and new leadership. He proposes holding quarterly town hall meetings around town. “We have to be more proactive,” he says.

Nobody mentions race or ethnicity, and the discussion reverts to traffic management. Later, over pizza, Wiltz explains he has learned not to speak bluntly about social divisions lest he offend. “I’m more coded now,” he says. Growing up in St. Martinville, La., a town of 6,000 residents, he understands that people get comfortable with the way things are and unnerved by rapid change.

Should Wiltz be elected mayor, one of his tasks will be to bring together a rapidly changing city with few unifying forces. Pearland is solidly middle-class: A starter house costs $140,000, and median household income is $97,000, much higher than in Houston. But newcomers rushing to downtown jobs barely brush shoulders with the mostly white retirees who tee off on the golf course weekday mornings or the older families that work and play near home.

Shopping habits reinforce a sense of division. Pearland has three Wal-Marts spaced several miles apart; residents refer to the one on the east side as “white Wal-mart” because of who shops there – and who doesn’t.

On election night, some Trump supporters waving Confederate flags drove the city’s main drag, says Wiltz, who took this as a racist affront. Nobody should assume that Pearland’s integration is a smooth one-way street, he says. “In these times, if you cherish and appreciate this diversity, we need to reach out to people who are different from us.”

Not far from the outskirts of Pearland stands the Sri Meenakshi Temple, its cream walls and wedding-cake lintels of Hindu gods rising above the flatlands. On weekends, thousands of Indian families come to pray at its shrines. Weddings take place in a modern building on the 26-acre site that also has a library, basketball court, and walking track.

The place was much more modest in 1978 when Vatsa Kumar emigrated from Bangalore, India: An 8-by-8-foot temple stood on the site, next to a trailer home where a single priest lived. Local ranchers were happy to sell plots to Indians in Houston who wanted a place to worship on weekends. “Land was cheap 40 years ago. We could get as much as we wanted,” says Mr. Kumar.

By 1982, the imposing temple that still stands today had been built, but it served a small Indian community living in the Houston area. Now the population has caught up with the temple’s ambition. Some 125,000 Indians live in Greater Houston, many in suburbs like Pearland.

“We’re still growing,” says Kumar, a retired nuclear engineer who helps run the temple. “A lot of Indian families have moved into this area.”

One of them is Rushi Patel. In 1985, when he was 9, his family immigrated to a small town in South Carolina where his father ran a motel. They were the only Indians in a segregated community, identified as neither black nor white. “What’s your American name?” the children asked him at school.

Two years later, the family moved to Darlington, S.C. The town was bigger, had a NASCAR course, and a handful of other Indian families. Mr. Patel studied accounting in college, then moved to Houston.

Together with his sister and brother-in-law, he owns a property development company that has two hotels in Pearland. On a recent morning, he sat in the lobby of the Hampton Inn, taking calls from staff at a new hotel going up near a petrochemical plant on the coast. A yard sign for Reid stood out front (“He’s a gentleman,” says Patel.)

In 2006, Patel bought a house on Pearland’s west side where he lives with his wife, an accountant who commutes to her job in Houston, and their two daughters. His sister lives nearby. His neighbors are a microcosm of the city’s growing diversity: a black-white couple with kids, a family of Middle Eastern descent, a white-Asian family, a black couple.

John Logan, a demographer at Brown University in Providence, R.I., says most metro areas now have what he calls “global neighborhoods” where no group has an absolute majority. Nearly all began as mostly white enclaves that integrated over time, he says. He believes that nonwhite immigrants who move into majority-white cities and suburbs act as a buffer that, over time, allows African-Americans to follow suit. And, given the vexed history of racial segregation and white flight, this immigrant-lined path could prove more stable than the unilateral movement of blacks.

“Global neighborhoods are made possible by immigration,” he says. “Hispanics and Asians [are] paving the way for integration of African-Americans.”

Immigration has certainly changed Houston’s demographics. In 1990, non-Hispanic whites were in the majority here (54 percent). By 2010, that share had dropped to one-third. Now 1 in 4 residents is foreign-born, compared with 1 in 7 nationally.

But that doesn’t mean that the old color lines – black and white, Latino and white – have been erased. As in many cities, patterns of segregation continue to shape where people live. Even in the suburbs, what looks like a mixed community from afar can turn out to be, on closer inspection, a balkanized spectrum of strangers occupying the same subdivisions.

Patel admits that busy commuting families in Pearland are often cocooned from their community, making it hard to build bridges. “They live next to each other. But they don’t know how to talk to each other,” he says. He smiles wryly. “I don’t know why I’m saying ‘they.’ ”

Ask Reid, the mayor, and he’ll tell you that it simply takes time for people to settle into a new community – especially when the town is growing as fast as Pearland. When he first moved here, he still went to his doctor and dentist in Houston, and attended church there. Gradually he found a local doctor, dentist, and Presbyterian church.

“It takes a while before you become part of a community,” he says. “We’re beginning to assimilate. There’s some people that say, ‘I sure wouldn’t want to live out there.... People are disorganized. Some of them don’t even know their neighbors.’ ”

The city has recruited more minorities into its police force, convened interfaith groups, and commissioned a diversity and inclusion study for its recreational services. Christopher Orlea, director of parks and recreation, says the goal is to roll out programs “that meet the desires of a cosmopolitan community and deliver a public service that is relatable to all residents.”

On May 6, Wiltz finished narrowly behind Reid in the mayor’s race (a third candidate took 5 percent). Kasseb polled first in her six-way race for a council seat. But no candidate in these races received more than 50 percent of the votes cast. So runoff elections for both positions will be held June 10.

Should Wiltz defeat Reid, he won’t quit his job in Houston. Yet he says that Pearland eventually needs a full-time mayor, not a figurehead, if it’s to manage its rapid growth and make sure that everyone feels represented at city hall.

“You can master-plan a neighborhood. But you can’t master-plan a community,” he says.

Postscript: On June 10, Mayor Reid defeated Wiltz, receiving 7,960 votes compared to 5,447 cast for Wiltz. In the other runoff vote, Kasseb lost to Woody Owens, who had previously served on the city council.

In Ramadan TV twist, Arab media challenges ISIS

There is a persistent perception that Arab countries could be doing more to counter terrorism. There's truth in that. But in many ways, a new Ramadan soap opera speaks to the kind of influence that could drive deeper social change.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

-

By Taylor Luck Correspondent

The night attackers in London killed seven people and wounded dozens of others, a major Pan-Arab TV network aired an episode of a made-for-Ramadan miniseries that also showed an Islamic State (ISIS) attack on London. According to programmers, the series, “Black Crows,” a 22-episode drama, marks an important initiative in Arab popular culture. Ramadan is a month of prized primetime programming as families gather around the TV at night. This year, networks and advertisers are addressing – and challenging – terrorism. Through the eyes of families, fighters, leaders, and particularly women, “Black Crows” delves into the daily life – and horrors – in Raqqa, Syria, the capital of the proclaimed caliphate. Producers say the series targets those who acquiesce to terrorism while condemning it from afar, and a minority who may be willing to adopt terrorist ideology. By depicting the brutality of ISIS, producers say they can show how alien and extreme the movement is to the Arab and Muslim world. “It is not optional any more for media outlets to watch terrorism happen without having a say in it,” says a network spokesman.

In Ramadan TV twist, Arab media challenges ISIS

Across the Arab world, millions of Muslim families settled in Saturday night to watch the latest episode of “Black Crows,” a special-for-Ramadan miniseries meant to convey the horrors of life under the so-called Islamic State.

The night’s episode of the Saudi-produced, 22-part drama, aired on the Saudi-owned pan-Arab channel MBC, depicted an ISIS suicide bombing near a London playground.

That same night, in a grim indication of the series’ relevance, three men killed seven people and wounded dozens of others on or near London Bridge, an attack later claimed by ISIS.

According to Arab programmers, too often Arab television networks have shown scenes of chaos in the rubble-filled aftermath of a suicide bombing or bloodied victims in the streets awaiting medical help.

Yet this Ramadan, a month of prized primetime programming as families gather around the TV at night, networks and advertisers are addressing – and challenging – terrorism.

Media experts and network executives say behind the shift is a realization that after years of broadcasting the car-bombings and beheadings that terrorist groups use to reach audiences, and more than a decade after networks, such as Al Jazeera, would air speeches by Osama bin Laden in their entirety, now is the time for media outlets to go after and challenge the terrorist narratives.

The first to break the mold is “Black Crows,” which was conceived of 18 months ago and is being shown on MBC, one of the go-to channels for many Arab families during the holy month.

'We have become numb'

Through the eyes of families, fighters, leaders, and particularly women, the series delves into the daily life – and horrors – in Raqqa, Syria, the self-declared capital of the ISIS caliphate.

The creators of ‘Black Crows” say the series came as a conscious effort to reverse years of “desensitization” to violence from the nearly weekly terrorist attacks that have ravaged the Arab world.

“We have become thick-skinned, we have become numb,” says Fadi Ismail, director of group drama at O3 Productions, which created “Black Crows” and other MBC programs.

“When we hear there are 80 killed here, 40 killed there – they are just numbers. Drama is a way to humanize and make it so engaging that it is no longer farther away – it could be in your own home.”

The decision to produce “Black Crows” came after the overwhelmingly receptive response to two episodes of the Ramadan series “Selfie” in 2015, in which the main character traveled to Syria to retrieve his son, who joined ISIS.

In late 2015, the production team began researching true stories of people living in or who have fled Raqqa. The series was shot in Lebanon using a pan-Arab cast of Saudis, Egyptians, Tunisians and Syrians.

In Saturday’s episode of “Black Crows,” after the playground attack, a forlorn Raqqa baker and his son make kanaffa sweets to be distributed to ISIS commanders in celebration. “We used to bake kanaffa for happy occasions, for weddings,” the baker notes, “what does it mean for us now?”

Bleak life for women

Life is portrayed as especially bleak for women, who dominate the series.

One woman is shot for selling plates decorated with depictions of animals. Another is thrown into prison for reading the grinds at the bottom of coffee cups, a practice observed by Arab women stretching from Morocco to Iraq.

Schoolgirls who have backpacks featuring “infidel characters” such as princesses and cartoons, are forced to cover up their faces with black marker – with one schoolgirl saying black “is the only color” she now needs in her life.

At a hospital seized by the jihadists, commanders decide to behead doctors and nurses – as ISIS “takes no prisoners” – to scare and intimidate their enemies, a declaration that startles and unnerves ISIS fighters. A young boy rebuffs attempts by an ISIS emir to enroll in him the jihadists’ brigade.

Over the course of its first several episodes, fighters, both men and women, begin to have doubts about the group’s brutal tactics and actions that go against central tenets of Islam. Very quickly, those doubts turn to regret as central characters realize they are now trapped in ISIS.

According to initial figures, MBC says that up to 30 million people have been watching.

MBC says “Black Crows” targets two types of viewers: “neutrals” who adopt a “laissez faire” attitude toward terrorism and who condemn it from afar, and the fringe minority who may be willing to adopt the ideology or approaches of terrorist networks.

Producers say they hope that by depicting the brutality of ISIS through the cruel banality of daily life, particularly of women, they can show how alien and extreme the movement is to the Arab and Muslim world.

“It is not optional any more for media outlets to watch terrorism happen without having a say in it,” says Mazen Hayek, an MBC spokesman.

“It is not enough anymore to pray for Istanbul or pray for Manchester or pray for London every day, media-wise,” he continues. “With this threat, we have to be more proactive and give our opinion to change the narrative.”

Anti-terror ad

Challenging terrorism hasn’t been restricted to programming on Arab media outlets.

Some corporations are using their presence to address extremism.

Kuwait-based telecommunications giant Zain specifically targets, and challenges, extremist groups’ claims in a special Ramadan ad, titled “Lets bomb violence with mercy.”

In the ad, a suicide bomber comes face to face with his victims as he struggles to justify his act.

“You who comes in the name of death, he is the creator of life,” a passenger on a bus challenges the bomber.

In the end, dozens confront him with messages of love and mercy.

“Worship with your God with love, not terror,” Emirati pop singer Hussein Jasmi sings along with the chorus: “Be tender with your faith, tender not harsh.”

The advertisement is notable as it features real victims of terrorist attacks that have ravaged the region over the past 12 years, including Ibrahim Abdulsalam, who was wounded in a Kuwait mosque blast, Haidar Jabar Nema, who lost his son in a bombing in Iraq, and Nadia al Alami, a bride whose wedding was hit by Al Qaeda suicide bombers in Amman.

Since being posted on May 27, Zain’s Ramadan ad has garnered more than 5 million views on Youtube, while tens of millions are watching the ad each night – oftentimes during ad breaks for “Black Crows.”

Zain has declined to comment on the advertisement, choosing instead for the ad to speak for itself.

Discomfort Zone

A mother’s mission to change society’s response to murder

Who deserves compassion? Does a mother of a gang member deserve society's embrace? One mother whose son was murdered by a gang says yes, and she has used that conviction to stand against violence in her hometown.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Clementina Chéry’s son, Louis, wasn’t in a gang. He was killed on his way to a Teens Against Gang Violence meeting. But even as she felt the warm embrace of her community and its leaders in the aftermath, Ms. Chéry wondered: Would the healing response to his murder – and the treatment she received – have been the same had her son been involved in a gang? That led her to explore the “stigma” put on bereaved mothers whose children were associated with illegal activity – and eventually to meet with the mother of the man who had pleaded guilty in Louis’s killing. (“We really saw each other as mothers,” she recalls.) Chéry's sense of mission guided her to found the Peace Institute in Boston. For more than two decades it has taken a holistic approach to addressing violence, working with law enforcement, developing a peace-themed school curriculum, and providing support to the incarcerated and their families.

A mother’s mission to change society’s response to murder

Fifteen-year-old Louis Brown, an aspiring engineer with a penchant for comic books and Chinese food, wasn’t in a gang. On the contrary, he was on his way to a Teens Against Gang Violence meeting when he was killed in the crossfire of a gang-related shootout.

In the days and weeks that followed, members of Louis’s family found themselves on the receiving end of a flood of support from Boston city officials and the local community. But while appreciative, his mother, Clementina Chéry, says she couldn’t help but wonder if they would have received the same treatment had the circumstances surrounding Louis’s death been different.

“What if my son was gang-involved?” she muses aloud, 24 years later. “What would happen to my family and me? Would the city really have provided us support?”

That hypothetical scenario, coupled with a desire to spread Louis’s vision for a more peaceful world, has guided the creation and development of the Louis D. Brown Peace Institute, a Boston-based organization whose goal is to “transform society’s response to homicide.” Though best known today for helping the loved ones of homicide victims, the Peace Institute has, over the course of its more than two decades in existence, adopted a holistic approach to address the roots of violence. This includes working with law enforcement agencies across the state, developing a peace-themed curriculum for local schools, and providing support to incarcerated persons and their families.

As founder and chief executive officer of the Peace Institute, Ms. Chéry – a chaplain who goes by Tina – has received widespread recognition for her work. She was named Public Citizen of the Year by the National Association of Social Workers in 2010, has addressed the National Organization for Victim Assistance’s annual conference three times, and has published research in the American Journal of Preventive Medicine.

But sitting in her office at the institute’s headquarters, tucked away on a quiet residential street in Boston’s Dorchester neighborhood, Chéry says her top priority is making a difference in her own backyard, one neighbor at a time.

“Our mission is that we’re a center of healing, teaching, and learning,” she explains. “I think when we start with families and with individuals and begin to treat people with dignity and respect, just basic human needs, then hopefully individual families, communities, society, and eventually the world will change.”

Chéry recalls that prior to the media learning that her son wasn’t involved in illegal activity, few resources were readily available to her and her family. It was only after the public learned of Louis’s clean record that “the resources came to us.” It’s thus of prime importance to Chéry and the Peace Institute that the families of all homicide victims receive the support and resources necessary to begin the healing process, regardless of circumstance.

Chéry has developed a number of tools for families, including a workbook for grieving children and the Survivors Burial and Resource Guide, which gives step-by-step information on matters such as selecting a funeral home and interacting with the police.

But the Peace Institute’s support for grieving families extends beyond practical guidance. Scattered around the institute’s headquarters are small toys and objects used in “sandplay,” a therapeutic technique in which people create a manifestation of their imagination in boxes of sand.

Some survivors, as Chéry calls them, prefer to express themselves this way. Some visit support groups to connect with fellow survivors. Others opt for one-on-one meetings.

How one mother has gotten help

When it comes to healing, there’s no single path, says Ruth Rollins, who lost a son in 2007 and visits the institute biweekly to meet with Chéry. “Everyone’s prescription ... is a little different, and you’ve got to get your own,” she says.

Ms. Rollins says she has felt – both personally and through her work as a professional domestic violence advocate – the “stigma” put on bereaved mothers whose children were associated with illegal activity. Her son, Warren Daniel Hairston, who went by Danny, was involved in gang activity at the time of his death.

“I knew my son mattered ... but [society] didn’t acknowledge it,” Rollins says. “I lost a child who may not have been a saint, but he was my child. We’re all victims when we lose a child to gun violence.”

Rollins says that Chéry and the Peace Institute have helped give her direction. “If you find a purpose, that’s half the battle,” she adds. “Tina helps you find your purpose. She supports you through your purpose.”

The Peace Institute is also known for its work with another kind of victim, even less frequently recognized: the families on the other side of homicides. These efforts, too, were born out of Chéry’s personal experience. Years after Louis’s death, she reached out to Doris Bogues, the mother of the man who pleaded guilty in the killing – in part, she says, to understand “who could raise a child that could kill.” The two met at a local bar, where they greeted each other with “silent tears and a warm embrace.”

“We really saw each other as mothers,” Chéry says. “When I saw her, I really saw me. In addition to seeing her shame, I felt her pain.”

Through support groups and partnerships with local nonprofits, the institute’s Intergenerational Justice Program aids the families of incarcerated people as they deal with that sense of pain and shame. In formulating the program, Chéry took a “do unto others”-type approach.

“I’ve always looked at, What would I want done if my son was the one who was accused or convicted of killing someone?” she says. “Both families are impacted, because none of us raise our children to kill or to be killed.”

Mother’s Day Walk for Peace

Today, Ms. Bogues is a regular volunteer at the Peace Institute. She and her son, Charles Bogues, who was paroled in 2012, have also participated in the institute’s Mother’s Day Walk for Peace, an annual march across Boston that attracts thousands of survivors and allies from around the state. At the culmination of last year’s walk, Mr. Bogues, for whom Chéry helped coordinate a reentry plan upon his release from prison, addressed the crowd at City Hall.

Despite rain in Boston this Mother’s Day, hundreds turned out for the walk, including Massachusetts Gov. Charlie Baker and Boston Mayor Martin Walsh.

Since its inception 21 years ago, the Mother’s Day Walk has been “a movement, a tradition we look forward to,” says Ayanna Pressley, Boston city councilor at large, who has worked with the Peace Institute in various capacities.

“The number of families, homicide victims, and people who are promoters or agents or advocates for peace from throughout the city who participate is inspiring,” Ms. Pressley continues. “It has everything to do with the mission of the Louis D. Brown Peace Institute, but also the leadership, the compassion, and the heart of Tina.”

Many local change-agent groups, she notes, have been created and developed with the “generous” support and mentorship of Chéry and the Peace Institute.

One such organization in the works is helmed by Rollins – We Are Better Together: Warren Daniel Hairston Project. The initiative, which Rollins is set to formally launch in June, will “educate, support, and serve families on both sides of gun violence in order to break cycles of violence and victimization.”

Throughout the development process, Rollins says, Chéry has been her “biggest cheerleader,” offering both emotional support and practical guidance. But even as Rollins continues to grow her own initiative and help others, she doesn’t foresee a time in the near future when Chéry and the Peace Institute won’t be a part of her life.

“That work takes a toll on you, and it becomes emotional,” she says. “I know when I go to the Peace Institute, I don’t have to be strong. I can breathe. I’ve got support. I’ve got family.”

• For more, visit ldbpeaceinstitute.org.

How to take action

UniversalGiving helps people give to and volunteer for top-performing charitable organizations around the world. All the projects are vetted by UniversalGiving; 100 percent of each donation goes directly to the listed cause. Below are links to three groups aiding children:

Plan International USA is part of a global network that works side by side with communities in 50 developing countries to end the cycle of poverty for children. Take action: Help provide proof of identity to those without birth certificates.

Supporting Kids in Peru helps disadvantaged children realize their right to an education. Take action: Be a volunteer coordinator for this program.

Foundation for International Medical Relief of Children aims to improve pediatric and maternal health in the developing world. Take action: Volunteer for this organization in Nicaragua.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

The other target in London Bridge attacks

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By The Monitor's Editorial Board

Terrorists aim not only to kill but also to destroy social order. Britain’s response to the June 3 attack shows how societies must bond – like a bridge – against this threat. Like most terrorist attacks, this one – the third in Britain in the past three months – failed to shake the social order that allows people from diverse backgrounds to share common purposes and values in peaceful ways. In fact, it renewed Britain’s trust in it. Prime Minister Theresa May emphasized this point in her response, saying that terrorism “will only be defeated when we turn people’s minds away from this violence and make them understand that our values – pluralistic British values – are superior to anything offered by the preachers and supporters of hate.” The attack should not split British society apart, especially in raising suspicions about the Muslim minority. The best response after a terrorist strike is to build more bridges.

The other target in London Bridge attacks

When terrorists attacked a crowd on London Bridge June 3, they may have also tried to attack a part of the social order. Bridges help bond people from diverse backgrounds, allowing them to share common purposes and values in peaceful ways. Like most terrorist attacks, this one – the third in Britain in the past three months – failed to shake that social order. In fact, it renewed Britain’s trust in it.

Prime Minister Theresa May emphasized this point in her response, saying terrorism cannot be defeated alone by military intervention or other counter-terrorism operations. “It will only be defeated when we turn people’s minds away from this violence and make them understand that our values – pluralistic British values – are superior to anything offered by the preachers and supporters of hate,” she said.

Like bridges, free and fair elections are also part of the social order. Ms. May was wise to say the attack would not delay parliamentary elections set for June 8. The attack should not split British society apart, especially in raising suspicions about the Muslim minority. “[T]he whole of our country needs to come together to take on this extremism, and we need to live our lives not in a series of separated, segregated communities, but as one truly United Kingdom,” she said.

Similar statements were heard in Afghanistan in recent days after terrorists killed some 117 people in the capital, Kabul, with bomb blasts. The Afghan government said such actions go “against the values of humanity as well as values of peaceful Afghans.” A former vice president and leader of the Islamic Unity Party, Mohammad Karim Khalili, went even further, saying the bombings also violate Islamic values.

In both Britain and Afghanistan, the common call was for unity, not just against extremist ideology but to join in ensuring safety and renewing civic life built on such values as freedom and individual rights. In Afghanistan, hundreds of people took to the streets to demand a unified government, or at least one less factionalized than the one under President Ashraf Ghani.

Social order is best built from the people up, relying on shared ideals of peace and respect rather than an over-reliance on surveillance from government. Compliance with security measures – such as airport screenings – are more accepted when people understand the common good is at stake.

The best response after a terrorist strike is to build more bridges that bond people.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Education that guarantees success

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By Barbara Vining

For some, graduation marks the start of an exciting new stage in life; for those who are uncertain about what the future holds, it can be disconcerting. But regardless of where we are in life, we can trust that God, divine Mind, has given each of us the capacity to grow, learn, and succeed. Education that leads to higher and higher mental development and achievement is available to everyone. Contributor Barbara Vining has seen this in her own life, despite her college education being cut short by family responsibilities: What she learned in Christian Science about our infinite potential as God’s children inspired a deeper understanding of education that has opened up an ever-expanding and fulfilling career of meaningful service.

Education that guarantees success

Graduation can be an especially happy time for graduates who know what is coming next and are looking forward to it with eagerness and confidence. But graduation can also bring trepidation about one’s future – perhaps because of student loans to repay, having no job pinned down, or some other factor.

In order to find answers to such concerns, it helps to realize that though academic graduations are important milestones, real progress in any situation comes when education is understood as a form of lifetime development. And looking at education as a spiritual pursuit can make all the difference in the world in how a person graduates, if you will, from both the minor and major challenges that come up in every human being’s experience.

My study of Christian Science has helped me understand that no one is, or ever can be, stuck in a thwarted state of educational development. Based on the teachings of the Bible, Christian Science defines God as the divine Mind. This Mind is infinite and is everyone’s true source of intelligence. Because of this, there is nothing to stop anyone from being led to higher and higher mental development and achievement. True education is actually a leading out of the infinite possibilities already within each individual as God’s spiritual image and likeness.

This leading out has certainly been true in my own experience. Having curtailed my college education to marry and raise a family, I often felt at a disadvantage educationally.

But wow! – I can remember the exact moment when I realized I had infinite possibilities within me as God’s image, and that true education was in letting the divine Mind draw out those possibilities. Then, I knew there were no limits to what I could accomplish if I would just be receptive to God’s guidance day by day.

So, without aspiring to any particular goal other than to learn from God each day and to be of service to others, I began writing for the Christian Science periodicals.

Gradually, through the years my writing skills have increased, and – to my surprise – I have been tapped for editorial positions, speaking assignments, and managerial responsibilities for which I have had no formal training. The work has always seemed natural to me, and I remain on a joyous and surprising journey of learning from God what I am capable of as His reflection.

Every challenge we face is an opportunity to graduate to a higher understanding and demonstration of our unlimited spiritual capacities. And this growth serves to expand our opportunities for higher and higher service and productivity in our experience as we move forward spiritually.

Adapted from "Education, graduations, and lifetime milestones," in the May 15 issue of the Christian Science Sentinel.

A message of love

Moving forward in Manchester

A look ahead

Thank you for reading today. Be sure to watch your inbox nightly. We have a number of good pieces under way this week, including a look at some of the broader issues underlying the Trump administration’s push to privatize the US air-traffic-control system.