- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Monitor Daily Intro for September 11, 2017

Mark Sappenfield

Mark Sappenfield

This week, Australians will begin voting on whether to legalize same-sex marriage. The vote is peculiar – it’s by mail and won’t be binding. But it’s intended to show what Australians want. Polls suggest it will pass, though the vote-by-mail element adds unpredictability.

Basically, no one likes this solution. Opponents of same-sex marriage worry that the vote might succeed, while supporters note that parliament could settle the issue on its own – and meanwhile, the campaign is disparaging lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people. What’s the point? they ask.

That becomes clearer in a television ad by the “no” campaign. At one point, a mother says, “School told my son he could wear a dress next year if he felt like it.” The claim has nothing to do with same-sex marriage. But it speaks to a deep sense of cultural insecurity. Advocates for same-sex marriage will wonder what is taking Australia so long, but attitudes toward marriage and homosexuality there, as in the United States, have reversed astonishingly fast – in little more than a decade. In that way, a vote no one likes represents a country still struggling to find its footing amid seismic change.

Here is our take today on stories that examine perseverance, moral leadership, and innovation.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

In post-Harvey school recovery, lessons from Katrina

In the wake of hurricanes Harvey and Irma, one need is to keep kids from feeling like spare parts as they're passed from place to place as cities repair damaged schools. That means protecting them from a sense of upheaval, experts say.

-

Henry Gass Staff writer

Today is the first day of school for many students in the Houston Independent School District, the largest district in Texas and the seventh largest in the nation. With the return to sharpened pencils and homework comes the question of how to support students and staff in the wake of a hurricane. While the post-Harvey educational context differs from New Orleans – which experienced a mandatory evacuation, major loss of life, and a state takeover of the school system – some of the insights gained as Katrina kids have grown up can help guide school officials in both the flooded Texas districts and the districts welcoming displaced students. Lori Peek, co-author of “Children of Katrina” and a sociology professor at the University of Colorado-Boulder says there were “some really creative things that receiving schools did in evacuee communities,… trying to treat the child in this more holistic manner so the child could learn.” HISD has implemented rolling start dates, relaxed uniform rules, and is even offering meals to all students. “They’re being more lenient,” says Lakshmi Kothun, whose son is an HISD student.

In post-Harvey school recovery, lessons from Katrina

Bryan McMillian was supposed to start college Aug. 28 at Prairie View A&M University, near Houston. Now, the apartment he had lined up in nearby Cypress, Texas, is flooded, and he’s trying to figure out if he can take online classes for a semester while he stays with some family in Austin.

Harvey wasn’t the first hurricane to disrupt his educational journey. Katrina hit on what would have been his first day of first grade in New Orleans. His family spent two years in Houston before they made their way back to Louisiana.

Now, six schools and innumerable life lessons later, this is what he’d say to a child displaced in Texas or, now, Florida: “Don’t let it get you down…. I know that this hurricane has caused damage…, but use this as the fuel to send you to even higher thinking and higher learning.”

He and the many adults tasked with helping children through the aftermath of disaster know that’s easier said than done. In Houston, some schools are reopening this week, while others are trying to figure out how to assist the students whose schools won’t be inhabitable anytime soon.

Staggered start dates

Houston Independent School District (HISD), the seventh-largest school district in the country and the largest district in Texas, has about 280 schools serving some 215,000 students. Given the devastation from hurricane Harvey, the district has implemented rolling start dates for many campuses, with a majority of schools starting today, and several dozen more starting next week and the week after. Included among those are seven schools that will have to have classes in alternative locations due to damage.

“To ask that kid [affected by a disaster] to show up ready to learn is a pretty big ask. Adults … have a huge responsibility to acknowledge and understand the different psychological, cognitive, and emotional effects of a disaster on students,” says Jessy Cuddy, director of culture and connections for Communities in Schools, a national network that works directly in public schools to coordinate local resources to assist at-risk students.

While the post-Harvey educational context differs from New Orleans – which experienced a mandatory evacuation, major loss of life, and a state takeover of the school system – some of the insights gained as Katrina kids have grown up can help guide school officials in both the flooded Texas districts and the districts welcoming displaced students.

For one, the number of moves a student has to make can chip away at educational progress. A report five years after Katrina noted that 34 percent of the affected middle- and high-school students were at least one grade level behind in school, compared to 19 percent of all children in the South.

They were also 4.5 times more likely than their peers nationwide to have symptoms consistent with serious emotional disturbance, according to the study, by the Children’s Health Fund, Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health, and the National Center for Disaster Preparedness.

Out of struggle, creative solutions

Many Katrina evacuees attending schools in Houston faced both academic and social struggles, such as being bullied because of the stigma attached to New Orleans when images in the media contributed to a false narrative of rampant violence and looting after the storm, says Lori Peek, co-author of “Children of Katrina” and a sociology professor who runs the Natural Hazards Center at the University of Colorado-Boulder.

On the other hand, she says, there were “some really creative things that receiving schools did in evacuee communities,… trying to treat the child in this more holistic manner so the child could learn.” Some set up buddy systems, for instance, where they matched a New Orleans newcomer with a child familiar with the school.

HISD is taking other steps, besides the rolling start dates, to make the back-to-school process easier on families. Schools will offer free breakfast and lunch to students until at least Sept. 30, as well as free dinner, but are asking parents and guardians to still apply. The school uniform policy has also been relaxed until January 2018. Students also aren’t expected to have all the necessary school supplies.

On Saturday, parents stood in line outside the Denver Harbor Multi-Service Center in north Houston for free school uniforms. One volunteer helping with the distribution, Lakshmi Kothun, says the steps HISD has taken are helping both students and parents.

“They’re being more lenient,” says Ms. Kothun, whose son is an HISD student. “I don’t think there’s any pressure on the kids’ side, [they are] just to have fun.”

“They don’t want to stay at home,” she adds. “They want to go [to school] and find out how their friends are.”

And she continues: “It gives parents time to clean up, too.”

But while HISD is taking steps to make back-to-school as easy as possible, many families are still facing an uncertain start to the school year.

Sitting on a cot in the emergency shelter at the NRG Center, a convention center, in downtown Houston last Thursday, Maria Barrios breastfeeds one of her children while admitting that she doesn’t know where her two elementary school-aged children will be going to school.

She’s registered them both for the new year, but it is unlikely she’ll be able to move back to her north Houston home any time soon. The NRG Center is miles from where her children went to school.

“Their school is so far away, they’re likely going to have to go somewhere else,” says Ms. Barrios, through a translator. “I’m really not sure just yet.”

A mixture of hardship and hope

The key for helping with transitions, says Professor Peek, is to not stereotype children as totally vulnerable or as totally resilient; they can be some of each, she says. But “they’re not like little red rubber balls. They’re not just going to bounce back without proper protections and support.”

Mr. McMillian’s story reflects that mixture of hardship and hope. He started school in Houston several months into the school year, after his family transitioned from a missionary shelter to a house.

“Most of the kids … were already learning things you would probably learn in second-, third-, or fourth-grade at home, so I was trying to catch up,” McMillian says of those early days transitioning into a first grade class. In New Orleans, he says, “I would slack off a lot and not put much effort into [school work]. But after seeing how those kids worked … I couldn’t do those things anymore. I had to learn that education is my one and only way out…. I never took my education for granted after that.”

His advice to teachers trying to help displaced students: Find something they really like doing. “It will cause them to open up more. When it comes to things they enjoy doing, it’s kind of like a safe haven or a peaceful place.”

For him, that was flag football. A Houston teacher found that out and “introduced me to the coach [for a nearby team], and he also handed me a book,” McMillian says. The book, by brothers Tiki and Ronde Barber, who both played in the NFL, “teaches you never to give up and to always keep pushing forward.”

Remember the teachers, too

In the wake of disaster, teachers need support, too, says Ms. Cuddy of Communities in Schools. “The biggest lesson out of Katrina: We asked teaches and school-support personnel and principals to go back to work the minute schools opened, and we expected them, without any processing or mental health support, to support the kids in their care…. Frankly, that’s irresponsible.”

In a question and answer section on it's website, HISD suggests that its plan for emotional support does include teachers: "HISD will have services available at schools to support the emotional needs of students and staff when they return. We are coordinating with other school districts across the region and country to help us in this effort, as we know many staff in our own district have been personally impacted by the storm."

With four siblings and a mom who had a hard time finding a job after Katrina, McMillian says, “there were some times where … in my head I would be like, this isn’t fair, my friends have this and I don’t…. Sometimes you have to go through struggles to really find the light within those.”

At school, he says, friends would help just as he was on the verge of giving up.

He returned to Louisiana and eventually to New Orleans, where he attended several schools before graduating from Landry-Walker High School earlier this year. The Urban League’s Project Ready program there enabled him to earn an electrical certificate through dual enrollment in the high school and a community college. He also helped his aunt build a community center in New Orleans, sparking his desire to study electrical engineering.

An image from the book “Esperanza Rising,” by Pam Muñoz Ryan, has stuck with him – the symbolism of the stitching of a quilt. “Our lives are the needle and the string that’s going through,” he says. “And Harvey is basically us going through and down. But you have to pick yourself back up, and go through, over and up.”

Share this article

Link copied.

How North Korea plays into China’s global ambitions

China is increasingly talking as if it wants to be a world leader – but what kind? To much of the world, China's permissive approach to North Korea represents a failure of leadership. China has a different view

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

-

Michael Holtz Staff writer

Gone are the days when China followed the dictum promoted by former leader Deng Xiaoping: “Hide your strength, bide your time.” President Xi Jinping “has moved China into a very different strategic posture” over the past five years, as one researcher in Hong Kong says. Mr. Xi now talks openly of “guiding” the international community. But there’s a glaring exception to this trend, in the view of many in other countries: the kid-glove approach that China takes toward its tempestuous neighbor, North Korea. US President Trump has publicly chastened Beijing for its hesitancy, and China’s caution risks undermining its growing reputation as a decisive player on the world stage. But that apparent weakness is a price that its rulers seem willing to pay now, in return for longer-term leadership dividends. Kim Jong-un may be a humiliating thorn in China’s side, but Beijing still sees North Korea as more of an asset than a liability for its overriding purpose: to take America’s old mantle as the unchallenged power in Asia. For now, it seems, China is setting its own rules, charting its own path to a bigger global role.

How North Korea plays into China’s global ambitions

Is China’s courage failing?

Exasperated and embarrassed by North Korea’s nuclear and missile tests, Beijing is nonetheless shrinking from using all the influence it has to stop them. China reportedly refused to back US proposals for an oil embargo against Pyongyang, for example, forcing Washington to soften the UN Security Council resolution debated on Monday.

US President Trump has publicly chastened Beijing on Twitter for its hesitancy, and China’s caution risks undermining its growing reputation as a decisive player on the world stage. But that apparent weakness is a price that its rulers seem willing to pay now, in return for longer-term leadership dividends.

Stronger sanctions could throttle Kim Jong-un’s regime. And though the young dictator is a humiliating thorn in China’s side, Beijing still sees North Korea as more of an asset than a liability for its overriding purpose: to take America’s old mantle as the unchallenged power in Asia.

“If you are a major global power you are expected to step up at a time of crisis,” says David Shambaugh, an expert in Chinese politics at George Washington University in Washington, D.C. “China is not doing that.”

Instead, China is setting its own rules, and charting its own path to a bigger global role. Chinese President Xi Jinping is not vacillating, Prof. Shambaugh adds. He is simply pursuing interests very different from, even diametrically opposed to, the goals that the United States and its allies have set. “It’s a rational position,” he says.

Revamped leadership

Where once Beijing worked with Washington to find a common stance on North Korea, “their approach to the problem now is quite different from the US, South Korea’s, or Japan’s,” says Susan Shirk, a former US deputy assistant secretary of State for Asia. “We’ve gone back to the cold war era” when Russia and China routinely opposed Washington’s international policies.

Gone are the days when China followed the dictum promulgated by former paramount leader Deng Xiaoping, “hide your strength, bide your time.” Mr. Xi “has moved China into a very different strategic posture” over the past five years, says Zhang Baohui, who teaches international relations at Lingnan University in Hong Kong. He now talks openly of “guiding” the international community.

If Beijing is taking the lead on global issues such as the defense of free trade and the Paris accord to limit climate change, it is partly because the United States is abdicating the responsibilities it once took in these fields. But China also sees clear self-interest in such policies.

Self-interest also drives Xi’s trademark “Belt and Road Initiative,” an ambitious trade and development strategy designed to link China with Central Asia and Europe as it takes a larger role in world affairs. With growth slowing at home, China is looking to open new markets for Chinese goods and find new projects for its heavy industries.

And Beijing’s assertiveness in laying claim to, building up, and then militarizing a string of reefs and shoals in the South China Sea has illustrated its view of the region as rightfully a Chinese domain.

These territorial forays have earned China the reputation of being a bully among its neighbors – a striking contrast to the kid-glove approach that the regional behemoth has taken to tiny, impoverished North Korea.

Beijing's limits

Some observers see unexpected weakness in this behavior. “China has all the points of leverage over North Korea but seems terrified of doing anything,” says Kerry Brown, a professor of Chinese politics at King’s College in London.

If Beijing were able to use its influence to defuse the crisis, such a coup would burnish its international reputation as a constructive player on the global stage. “That would be a very significant sign of China demonstrating much more clout [and] effective diplomacy,” points out Amy King, who teaches defense studies at Australian National University in Canberra.

But the way it is currently dealing with the crisis, Dr. King adds, “shows the limits of China’s power and sway.”

China appears to have accepted North Korea’s de facto status as a nuclear power. Condemning recent belligerent US comments, Chinese Ambassador to the United Nations Liu Jieyi said last week that Beijing would “never allow chaos and war on the peninsula.” That formulation, later repeated by Foreign Ministry spokesmen in Beijing, made no reference to China’s traditional insistence on denuclearization of the Korean peninsula.

North Korea as a nuclear power would appear to pose obstacles to China’s regional leadership ambitions.

“Since the end of the cold war, China’s main goal in Asia has been to deter the influence of the United States in the region,” points out Zhu Feng, a professor of international relations at Nanjing University in China.

“We are not ready to abandon the DPRK politically and economically,” he adds, using the abbreviation for the country’s official name, “but the situation is getting less controllable. The DPRK is increasingly explosive.”

Long-term goals

The drawbacks for China are clear: The Korea crisis sucks the United States back into China’s backyard; it strengthens Washington’s alliances with Japan and South Korea (setting up THAAD anti-missile defenses around Seoul that China fears can see into its own territory, for example); and it encourages its rival Japan to strengthen its own military defenses.

But in the long run, argues Dr. Shirk, who now runs the 21st Century China Center at the University of California San Diego, a nuclear-armed North Korea capable of destroying US cities would be well-placed to undermine America’s alliances with Japan and South Korea, the two key pillars of Washington’s military presence in Asia.

“We would have a harder time making our commitment to our allies credible,” she suggests. “They would be uncertain that we would take the risk of defending them against North Korea if that meant putting our homeland at risk.”

If China has “the sense that the US presence in Asia is a bigger problem than the North Korean threat,” Shirk worries, “it could be that China wants to maintain that threat so as to de-couple the US from its allies.

“Their government is motivated not just by a fear of the collapse of North Korea, but by the larger geostrategic benefit that China sees,” she argues.

“The United States is the only country that can get in the way of China’s goals in the region,” adds Valerie Niquet, a China expert at the Foundation for Strategic Research, a think tank in Paris. “In that context, where the main concern is its rivalry with the US, China still believes that North Korea is a strategic asset.”

And there are domestic considerations too, Shambaugh points out. North Korea regards its nuclear program as an existential guarantee of survival. The pressure required to persuade the government to give up its nuclear ambitions would also likely bring it down.

Deliberately destroying a fraternal socialist government, at the behest of the United States, would raise questions about the legitimacy of Communist Party rule in China.

China is not acting as forcefully as it might “for very rational reasons,” Shambaugh says. “It’s the perceived potential instability the Communist Party feels about its own system. It does not want regime collapse in Pyongyang.”

For those fleeing Irma, relief, gratitude, and sometimes guilt

Just as hurricane Harvey showed Americans’ incredible capacity to help, hurricane Irma showed their capacity to cope, with millions of people fleeing south Florida for hotels, makeshift camping sites, and Alabama peanut festivals.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

-

Warren Richey Staff writer

More than 6 million Floridians and Georgians fled hurricane Irma – perhaps the biggest mass evacuation in US history. Millions ended up in hotel rooms and friends’ houses in cities like Birmingham and Atlanta, where the Atlanta Braves treated evacuees to free tickets on Saturday night. But Russ Fisher, a Wal-Mart employee, was one of the disaster’s thousands of wanderers, landing, like a windblown butterfly, at the National Peanut Festival grounds here in Dothan, Ala. Finding it impossible to find a hotel room and with friends too far away, the evacuees braved Irma on the highways, bringing whole kennels, horses, elderly people, and babies on a harrowing escape. As they watch the skies, Irma’s itinerants also bear witness to a deep resiliency in the United States. As in Houston, Americans' spirit of generosity has rushed in to fill the void. Evacuees talk about being given food, shelter, and money for gas as they fled the storm. For many, the only belongings with them are important papers and ice chests. “I've just got me and my bike and felt I had to go,” says Tampa filmmaker Timothy Abbott, who left with less than $100 in his pocket. Strangers gave him another $100 for gas, and the promise of a place to stay in Mississippi. “I left my parents and my granddad back there with God.”

For those fleeing Irma, relief, gratitude, and sometimes guilt

This story was updated on September 11 at 3:30 p.m.

If all else fails, Russ Fisher joked, his Audi A-4 is rumored to float.

The retired New Hampshire man says his mobile home park back in Crescent City, Fla., is 50 years old “and no hurricane has ever touched it.” But he and his bug-eyed pup, Betty Boop, decided to take off, racing in a tiny car ahead of a massive hurricane. Of his vehicle, he says, “One thing I’ve realized: That thing is not comfortable to sleep in.”

Lesson from meteorologists: Hope for the best, prepare for the worst. The lesson was borne out by the track of hurricane Irma migrating 150 miles westward by Sunday morning. That westward movement shifted ground zero in the hurricane from Miami-Ft. Lauderdale to the westward end of the Florida Keys.

It also put evacuees, who had fled north ahead of the storm, which was a Category 4 when it hit the Florida Keys Sunday, directly in its path.

More than 6 million Floridians and Georgians fled hurricane Irma – perhaps the biggest mass evacuation in United States history, dwarfing the 1 million who fled Louisiana and Mississippi ahead of hurricane Katrina in 2005.

Millions ended up in hotel rooms and friends’ houses in cities like Birmingham and Atlanta, where throngs took to restaurants and lounges and where the Atlanta Braves treated evacuees to free tickets on Saturday night.

But Mr. Fisher, a Walmart employee, was one of the disaster’s thousands of wanderers, landing, like a wind-blown butterfly, at the National Peanut Festival grounds here in Dothan. Hundreds of RVs and cars pulled in on Saturday only to pack up again Sunday as the National Hurricane Center, once again, tweaked the storm’s track to the northwest, its sights this time on Dothan.

Finding it impossible to find a hotel room and with friends too far away, the evacuees braved Irma on the highways, bringing whole kennels, horses, the elderly, and babies on a harrowing escape ahead of Irma’s spinning top.

To a person, they say they are battling fear and personal uncertainty, along with the dread of what will happen to their homesteads. Many also talk about a darker sense of survivor’s guilt, and worry about many of those whom they begged to leave.

"I've just got me and my bike and felt I had to go," says Tampa filmmaker Timothy Abbott, who left with less than $100 in his pocket. Strangers gave him another $100 for gas money, and he has the promise of a place to stay in Mississippi. "I left my parents and my granddad back there with God."

As they watch the skies, Irma’s itinerants also bear witness to a deep resiliency in the US, given back-to-back hurricanes and wildfires out West. As in Houston, Americans' spirit of generosity and philanthropy have rushed in to fill the void. Evacuees talk about being given, food, shelter, and money for gas as they fled the storm.

“We have top-down institutions like FEMA and law enforcement, but then we have bottom-up phenomenon too, like the market and civic engagement, so people can flee feeling secure that they can find a hotel room, that there will be a church that can help, or friends will reach out, even if they’re dealing with survivor’s guilt,” says Daniel Aldrich, author of “The Power of the People” and a political scientist at Northeastern University in Boston. “Hopefully we are going to see that places like Florida and Georgia are resilient to this kind of shock.”

Although the most damaging and dangerous forces were near the eye of Irma, bands of rain squalls and strong winds completely swallowed Florida.

Generally, damage in and around Miami appeared to be far less than what residents on Florida’s West Coast and Northeast corner were enduring. Jacksonville was hit Monday by record flooding. Officials also described widespread damage to Marco Island and the Florida Keys as the possible site of a humanitarian crisis.

More than 7 million Floridians were reported to have lost power Monday. While 38 people were killed during Irma’s charge through the Caribbean, so far fewer than 10 deaths have been reported in Florida. That number, officials warn, could rise.

Many on Florida’s southeast coast, who by Sunday afternoon had long ago lost power and were listening to the news on battery-operated radios, were grateful that ultimately the center of hurricane Irma did not come to the region. But theirs was a gratitude tempered with prayer for those in the storm’s path.

Dennis Wolke and Mike Murphy, who have been partners for 37 years, realized three days ago that their home at Riverview near Tampa would likely see a massive storm surge. “It won’t be there when we get back,” Mr. Wolke predicts, grimly. They have wandered the Southern lowlands for three days, their cats, Alex and Dexter, in the backseat of their sedan.

Mr. Wolke, who drives tanker trucks, spent days ferrying fuel to fill the thirsty gas tanks of those evacuating Florida as Irma became a Category 5 hurricane and Gov. Rick Scott (R) warned everyone in the Florida Keys and the mandatory evacuation zones to "get out now."

Mr. Murphy, offering his partner a gas station coffee, is sanguine. The cats, which spent the first day mewling, have mellowed out. They all have each other. They’ve had other devastating losses and have persevered. “With a little prayer, we’ll all make it,” says Murphy, a McDonald's store manager.

Irma made landfall in the Florida Keys as a Category 4 storm but was downgraded to a tropical storm by Monday. More than 2 million people had lost power and several deaths were reported.

One of the recurring problems with attempted mass evacuations is that people are reluctant to leave their homes unless they can bring the family dog or cat with them. In South Florida a number of “pet friendly” shelters were set up, including a shelter for pets only in Tamarac, in Broward County. The staff was trained by the Humane Society. By Friday, they reportedly had an evacuee population of 49 dogs, 63 cats, and one probably very nervous duck.

News from the Hemingway House in Key West that all 54 famed cats were safe was cheered by Floridians. And rescue workers in Manatee County successfully saved two stranded manatees.

Hank Tester, a longtime television correspondent with CBS4 in Miami, has covered his share of hurricanes over the years. In a report on Sunday morning from Ft. Lauderdale beach, he paused to consider the implications of a major hurricane hitting the Florida Keys near Key West, for which many Floridians hold a special affection.

On the second floor of the Hemingway House there is a display featuring a plate painted by Pablo Picasso, he told listeners. Ernest Hemingway and Picasso were friends in Paris, he added. “I just hope it’s OK,” he said, referring to the plate.

The storm's size and power drove Richard Hill, the son of a Florida pioneer, to set out with his wife, two grandkids, and no particular end in mind.

Mr. Hill is a lifelong Florida resident whose dad settled Fort Lauderdale in 1906. Many in that generation of Florida founders were Michigan copper miners who helped dig the Panama Canal. They began the shaping of a mosquito-ridden swamp into the tourist haven that Florida is today. “They were tough people,” says Hill.

Hill is tough, too. He didn’t run from Wilma in 2005, nor Andrew, which tore through Homestead, just 20 miles from his house in 1992. But this time he took his two teenage grandkids and drove away in the family RV. The crew spent the night at the Peanut Festival Grounds. But once the forecast turned, it was time to move again.

“I may just drive to Kentucky,” he says. “Anything to escape a case of the nerves.”

For many, the only belongings with them are important papers and ice chests. Professor Aldrich says anti-price gouging laws and basic corporate decency have so far protected those without many resources as they make their escape.

When Lori and James McShane arrived in Dothan, for example, a police officer guided them to the Peanut Festival grounds. There, a Baptist church, which was feeding evacuees, gave them a tent and air mattresses.

“These people were so good,” Ms. McShane says. “Makes me want to move to Alabama.”

“The hurricane is like a spinning top – it goes where it wants to go,” she says. “We truly don’t know where to go from here. The only thing we can do is keep moving.”

“At least we’re learning how to camp.”

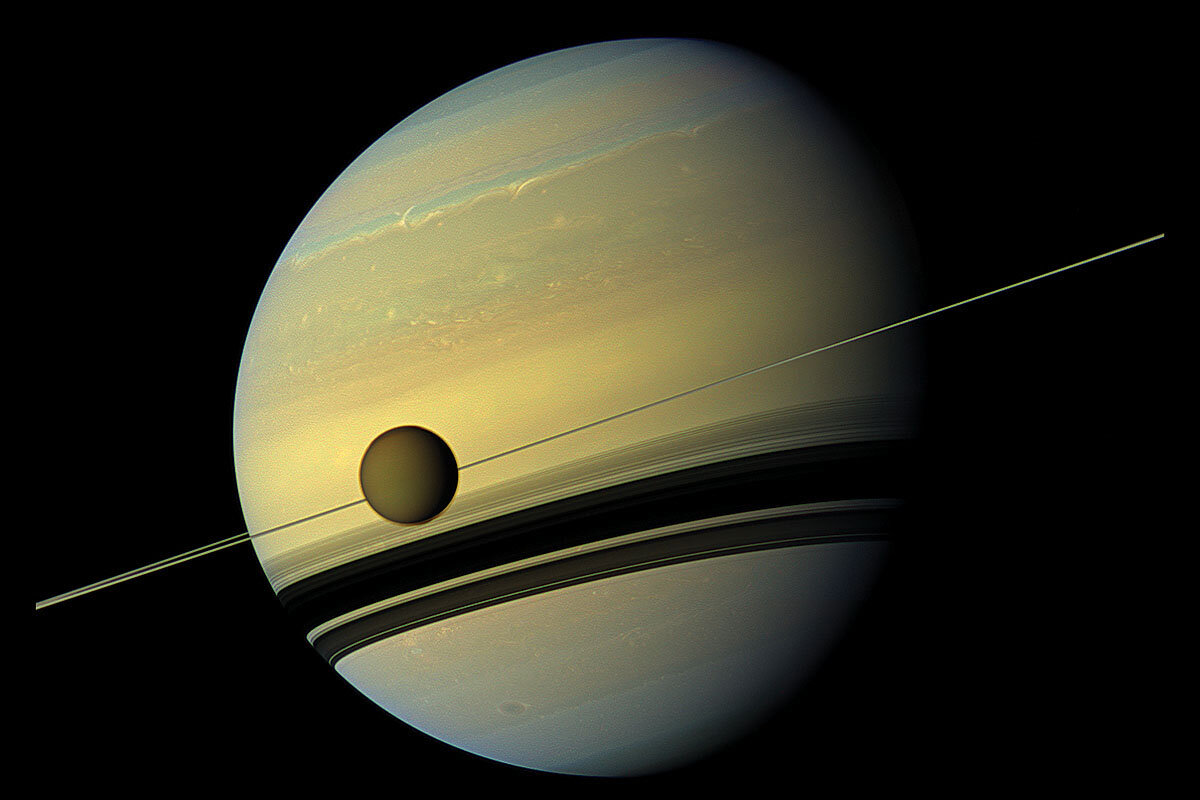

What Cassini, now in its final days, taught us about Saturn

In its 13 years, the Cassini spacecraft tasted the salty geysers of one frozen moon, sent a small probe splatting into the methane-soaked surface of another, and brushed its fingertips through the clouds of Saturn itself. This is its ecstatic epitaph.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 12 Min. )

-

Charlie Wood Staff writer

Thirteen years ago, Cassini – a nuclear-powered craft the size of a small school bus – embarked on a quest to increase our knowledge of enigmatic Saturn. Its mission has lasted longer than expected, and pulled down more information than anyone anticipated – about the physics of Saturn’s iconic rings; about the planet’s mysterious, swirling atmosphere; about the staggering variety of Saturn’s 53 confirmed moons. Perhaps most important, Cassini discovered salty geysers spewing out of one moon, containing hints that it could support life. Before Cassini burns up while plunging deep into Saturn’s atmosphere later this week, the craft may well send back more surprises. Even if it doesn’t, its legacy seems set in the annals of humans’ quest to fathom the cosmos. The Cassini mission, says one space historian, “has a pretty secure place as one of the highest performing outer solar system missions of our lifetime.”

What Cassini, now in its final days, taught us about Saturn

It was a tense moment. The little Cassini spacecraft was hurtling through the black void of space at 54,500 miles per hour. After a seven-year journey, the probe was finally approaching its destination – Saturn – in June 2004. But the spacecraft needed to slow down for the planet’s gravity to pull it into its orbit. So project engineers were going to pump the brakes by carrying out a controlled burn. It was a planned procedure, but a risky one.

Igniting the thrusters too long could burn up much of the spacecraft’s precious fuel, cutting the multibillion-dollar mission tragically short. Not slowing it enough would leave it flinging past Saturn, lost forever in space. The plan was to fire the engine for 96 minutes. If it failed to burn for even four of those minutes, the probe would pass ignobly into oblivion.

Dozens of mission scientists and their families converged in an auditorium at Pasadena City College in California to witness the moment. Adults passed the time and soothed nerves by answering a steady stream of questions about the mission from children. As the moment neared to find out if the burn was successful, a hush fell over the crowd. Cassini project scientist Linda Spilker couldn’t relax in her seat. She stood frozen.

Then, at 9:12 in the evening local time, the radio transmission arrived from 934,431,318 miles away, blinking the result on a large auditorium screen.

“We waited and waited, and finally there’s the signal ... boom!” Dr. Spilker says, recalling that warm California night of June 30. “Right on the line [in Saturn’s orbit]. We were cheering, hugging each other.”

Thus began Cassini’s auspicious quest to increase our knowledge of Saturn – an enigmatic planet that scientists have yearned to revisit for decades and which has fascinated humans for centuries. Today, 13 years later, the craft is about to end its mission as one of the most successful planetary probes in the history of space exploration.

The mission has lasted longer than expected. Cassini has sent back more information than anyone anticipated – about the physics of Saturn’s iconic rings; about the planet’s mysterious, swirling atmosphere; about the staggering variety of Saturn’s 53 confirmed moons. Perhaps most important, Cassini discovered salty geysers spewing out of one moon, containing hints that it could support alien life.

A joint project of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration and the European Space Agency (ESA), the $3.3 billion mission to Saturn has also shown how scientists from a diverse group of 17 nations can work together to explore the heavens. And the spacecraft’s work may not be done.

A fiery end is planned for Cassini in late September. But before then, the craft may well send back more surprises before it burns up while plunging deep into Saturn’s atmosphere. Even if it doesn’t, its legacy seems set in the annals of humans’ quest to fathom the cosmos.

The Cassini mission, says Matthew Shindell, a historian of science at the National Air and Space Museum, “has a pretty secure place as one of the highest performing outer solar system missions of our lifetime.”

No one knew precisely what discoveries lay ahead when Cassini blasted off from Cape Canaveral, Fla., in the cloudy predawn hours of Oct. 15, 1997. Just getting the spacecraft to that point was something of a triumph.

Budget concerns at NASA had put a number of missions in jeopardy in the 1990s, including Cassini. But the ESA was building the Huygens probe, one of the main features of the mission, and European scientists rallied behind the project. “For the US to pull out after the Europeans had spent hundreds of millions of dollars would not have been a good example of cooperation for the future,” says Richard French, team leader for the radio science instrument on Cassini and an astronomy professor at Wellesley College in Wellesley, Mass.

Scientists connected with the project had already put in more than a decade of work and were understandably excited. Cassini is, after all, the most highly instrumented planetary probe ever put into space.

The size of a small school bus, the nuclear-powered spacecraft consists of an orbiter and a lander. The Cassini orbiter, named for Renaissance astronomer Jean-

Dominique Cassini, would explore the Saturn system while circling the planet. It would also give the ESA-built Huygens lander a ride to Titan, Saturn’s largest moon, which was discovered by Dutch astronomer Christiaan Huygens in 1655.

The goal of the Cassini-Huygens mission was simple: to wring every secret possible from Saturn, its rings, and its moons. Humanity had gotten a glimpse of the planet before, in the early 1980s, when two probes, Voyager 1 and Voyager 2, sped past Saturn on their way farther out into the solar system and beyond. But this mission was different. Cassini-Huygens wasn’t an itinerant window peeper. It would be there to stay.

It offered the promise of unlocking secrets about a planet that has been the subject of curiosity since the ancient Romans tracked it in the night sky and named it Saturnus after their god of agriculture.

But first the craft had to overcome one small challenge: travel a billion miles.

Spacefaring often borrows terms from aeronautics, but Cassini more closely resembles a skydiver than a plane. It falls more than it flies, as gravity, rather than lift, determines its path.

Journeying to the outer solar system against the gravitational pull of the sun is no simple feat, and even Cassini’s three tons of fuel wasn’t enough to chart a direct flight to Saturn. So mission engineers had to rely on a method often used to propel probes, from Pioneer 10 to Galileo to Ulysses, deep into space: a cosmic slingshot.

Cassini’s first connection happened at Venus, a year after launch. Venus careens through space at nearly 80,000 m.p.h., and as Cassini passed by, the planet’s gravity dragged the craft along for the ride and then flung it away at more than 14,000 m.p.h. faster than it had been traveling before. It would repeat this trick, known as a gravity assist, the following year again with Venus, and then Earth, getting catapulted faster and farther from the sun each time.

Even with all this help, however, when Cassini finally settled into an orbit of Saturn in 2004, the spacecraft would have only about 20 percent of its liquid fuel left. The rest had been consumed by all the maneuvers needed to get there and the controlled burn to slow it down. The propellant would turn out to be enough, however, to carry the probe on nearly 300 orbits of the planet over the next dozen years – a mission life more than three times as long as scientists planned.

Yet none of this means the mission was easy. Studying a system as vast and complex as Saturn’s meant that hundreds of scientists around the world had to communicate regularly and compromise in making decisions. Consider just the itinerary alone. In an ideal world, planetary scientists would prefer to have sent Cassini on equatorial orbits of Saturn to get closer to its moons. But ring observers favor higher, tipped orbits. So, to try to satisfy everybody, Cassini went everywhere.

Spacecraft maneuvers had to be planned months in advance. Under its original design, Cassini was be fitted with an elaborate turntable to allow instruments to point where they needed to. But this “scan platform” was ditched to save money. Instead, engineers mounted all the instruments on the side of the spacecraft. So if, say, the imaging team wanted to point a camera in a different direction, the entire spacecraft would have to turn.

“Learning how to be cooperative with other scientists when you have a competition for resources has been really eye-

opening,” says Dr. French. “For me personally, the collaborations have been the most fun part of the mission, where you acknowledge that working together brings out the best science.”

The politics of all these decisions became more routine once Cassini got down to the process of discovery. A prime target of interest right from the start was Titan.

The moon, which is about the size of Mercury, has long been enshrouded in mystery. The Voyager probes couldn’t pierce the thick smoggy veil of Titan’s nitrogen and methane atmosphere decades earlier, but scientists were intrigued by its chemical composition. The atmosphere’s makeup hinted that Titan’s surface might look remarkably like Earth’s.

“There’s nothing like having a place where you know there’s a surface under there” but you can’t see it, says Jonathan Lunine, director of the Cornell Center for Astrophysics and Planetary Science at Cornell University and a scientist on the Cassini mission. “That kind of mystery is exactly what motivates future exploration.”

The Cassini spacecraft was to act as the eyes in the sky, swinging close to Titan for observation and gravity assists, while the Huygens lander would plant its feet on the ground. It would sample the surface chemistry and scour for other details. The results would be radioed back to the mother ship.

But that data almost didn’t make it back to Earth. A design flaw made Cassini’s “ear” too inflexible to receive radio waves from Huygens. Fortunately, a test by ESA communications specialist Boris Smeds uncovered the problem in early 2000, as the craft drifted through the asteroid belt. The flaw came down to one line of computer code, according to Mr. Smeds.

Nevertheless, it took a joint NASA-ESA committee a year to develop a way to solve the problem. Ultimately, an extra orbit around Saturn put Cassini on a path that would better position its ear.

At a cost of some backup fuel and a months-long detour from the painstakingly crafted tour plan, the $300 million Huygens probe finally touched down on Titan on

Jan. 14, 2005. It marked the first landing by a spacecraft in the outer solar system.

Smeds received a pair of champagne bottles for his find, but he says the real reward was salvaging the work of so many: “All these scientists, they work for this for years ... and it would have been very painful if they would have been there and everything was for nothing.”

Not all would have been lost had the Cassini receiver remained deaf to Huygens’s transmissions. Even from its vantage point in Titan’s skies, Cassini’s radar revealed rolling hydrocarbon dunes and the crinkled coastlines of methane lakes. But Huygens highlighted just how much Titan’s hydrological system resembles Earth’s own water cycle.

Indeed, the moon’s organic chemistry is thought to be much like that of Earth before life began. Liquid methane rains down on Titan, filling its lakes and rivers, and carving out gullies as it flows over the surface. Water fills that role on Earth, as it freezes, evaporates, and condenses at much higher temperatures than methane.

But water is more plentiful on Earth than methane is on Titan, which scientists say may make the moon’s climate system a good model for Earth’s climate system in the far-off future. “I like to call Titan the once and future Earth,” Dr. Lunine says.

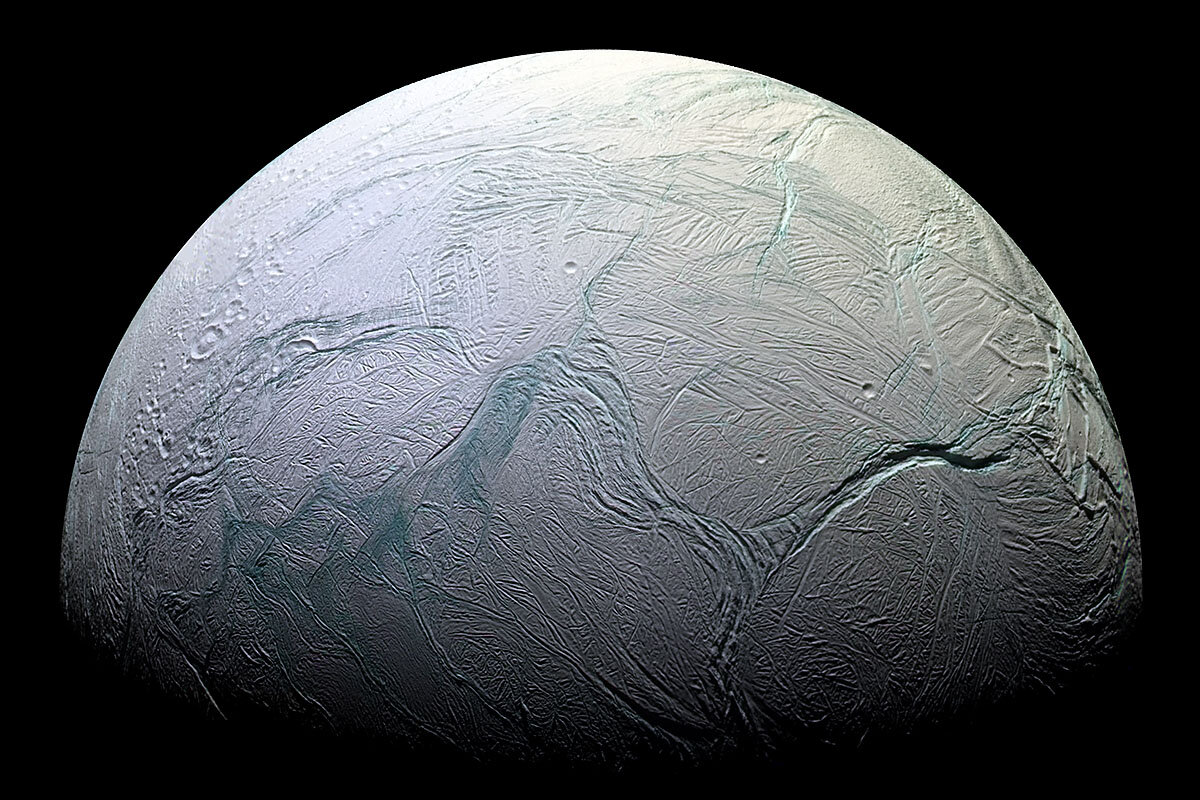

While Titan was supposed to be the marquee attraction among Saturn’s moons, another planetary satellite ended up sharing equal billing: Enceladus.

Before the mission, Enceladus was just another small moon to planetary scientists. But Cassini exposed it as a complex, dynamic world, perhaps capable of supporting life.

There were clues that some sort of activity might be happening on the surface of Enceladus before Cassini arrived. Enceladus sits in Saturn’s E ring, the planet’s second outermost ring, which is particularly tenuous and likely needs a continuous source of dust, rock, and other material to exist. Perhaps some activity on the surface of Enceladus was providing that material, some researchers thought, but others said that was unlikely for such a small, presumably dead moon.

Scientists had also noticed in Voyager images that Enceladus’s bright surface bore too few impact craters to be completely inactive, but it wasn’t until Cassini took a closer look that an explanation emerged.

“I guess there was more or less the bloody glove at the scene,” Lunine says. “But it was Cassini that discovered the perpetrator. And the perpetrator was this giant plume fed by these many jets of material coming out of the south polar region.”

The Cassini mission was initially planned to spend four years at Saturn, looking at Enceladus just a handful of times. But having made such tantalizing discoveries on the moon, and with the desire to witness seasonal changes on Saturn, NASA approved two extensions to the mission: the two-year Equinox Mission and the seven-year Solstice Mission.

“Enceladus really reshaped Cassini’s mission,” Spilker says. “Once we discovered the geysers, then it became important to go back again and again and again.”

What began as an ordinary survey of a seemingly boring moon turned into a new front in the hunt for alien life. Cassini has zipped close to Enceladus 23 times in all, with seven trips passing directly through the ice crystals spewing out into space.

The spacecraft identified a subsurface ocean as the source of the geysers. Instruments showed the ocean contains salts, carbon-bearing molecules, silica grains, nitrogen-bearing compounds, and molecular hydrogen – all conditions conducive to life.

“It was just one ‘wow’ after another,” Spilker says.

For all the excitement over Titan and Enceladus, many scientists never strayed far from the mission’s central star, Saturn, and its eye-catching rings, which have been a source of intrigue ever since Galileo first noticed them in 1610 and mistook them for a trio of celestial bodies.

New data from Cassini sets the thickness of the rings at about 30 feet – vanishingly thin compared with their 175,000-mile circular span. “People say that’s as thin as a razor blade, but it’s much, much thinner,” says Jeff Cuzzi, a ring specialist at NASA’s Ames Research Center and a scientist on the Cassini mission.

Cassini also found evidence that the particles, chunks, and boulders of ice that make up the rings are engaged in a sort of galactic dance. When Voyager swooped in for a look at the planet, its images suggested that the ring particles’ random bumping gave rise to a relatively smooth disk. But Cassini’s measurements indicate something more intricate is going on.

Gravity orchestrates the rings’ structure and motion. Saturn’s gravity keeps particles in its orbit, with the inner rings turning faster than the outer ones. As the particles circle the planet, they jostle each other in a way that makes the rings behave like a fluid.

And just as boats make waves in the ocean on Earth, the movements of Saturn’s moons trigger waves in the sheet of rings. As a result, the rings seem to dance with vibrations, ripples, and horizontal compressions that spiral tightly inside the rings.

“Our solar system that we think of as so solid and reliable,” Dr. Cuzzi says, “is actually full of dynamical surprises.”

And those surprises bring lessons with wide-reaching applications. The spiral compressions going on inside the rings have supported theories explaining the pinwheel arms of galaxies, while some of the other dynamics mirror the formation of planets early in the solar system.

Despite the trove of information already pouring in from Cassini, many questions remain to be answered. How old are the rings? How much do they weigh? What gives them their tawny color? Saturn’s rings appear redder than a typical ice cube, suggesting the presence of some mystery ingredient.

Of the multitude of riddles remaining about Saturn, a few may yet be resolved as Cassini plummets to its fiery demise. The spacecraft is running out of fuel, and mission planners didn’t want to let it keep flying right down to its last kilogram of propellant. That would risk having it crash on Titan or Enceladus and contaminate a potentially life-bearing world.

Instead, they set it on a course to plunge toward the planet. In recent months, Cassini has been going through a series of daring dives as part of what NASA calls the “Grand Finale.” It has been lunging through the wide gap between Saturn and its rings and, more recently, down into the planet’s upper atmosphere – areas never before explored.

On its final dive, Cassini will drop sideways toward Saturn’s voluminous cloud cover. Thrusters will stabilize the spacecraft as it encounters the atmosphere and keep its antenna locked on Earth so scientists can glean data down to the last second. Seven instruments will remain switched on, including an atmospheric probe.

Then, on Sept. 15, the heat of plummeting through Saturn’s thick atmosphere will become too much: It will consume the craft in a final moment of incendiary glory at 4:56 a.m. Pacific Standard Time. Spilker will be among those listening when the radio waves carrying Cassini’s final messages reach Earth, from halfway across the solar system. But, for many scientists, the end of the mission is far from the end of Cassini’s ability to convey knowledge.

“Now we have this mountain of data that we need to start working our way through,” says Cuzzi. “Cassini’s going to go on for decades, and I look forward to seeing that.”

Breakthroughs

A boom in high-tech helpmates for the visually impaired

Technology is bridging the seeing and visually impaired worlds. New apps are giving blind users a boost while also revealing to sighted people just how capable the visually impaired are.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

Like most public-transit riders, Joann Becker relies on her smartphone to keep up with bus and train schedules. Navigating Boston’s transit system can be challenging for any commuter. But for blind riders, like Ms. Becker, each stop presents a unique challenge. Now, that challenge is getting a little bit easier, thanks to a new app Becker helped develop with her colleagues at Perkins Solutions. BlindWays provides visually impaired commuters with clues and landmarks for each stop, crowdsourced from sighted users. It's just one of many new options for visually impaired people, as single-purpose assistive devices have given way to more accessible – and affordable – apps. Perhaps just as valuable is the glimpse into the capable lives of people with limited vision that such apps offer. “The reality is, most sighted people don’t know somebody [who is] blind,” Becker says. “I think these apps are enabling sighted people to see that blind people just need some simple clues to help them do any number of things in their lives.”

A boom in high-tech helpmates for the visually impaired

When asked how technology might improve the lives of people with vision impairments, Joann Becker presented a deceptively simple challenge.

“Well,” the tech specialist recalls saying, “I’d like to be able to find my bus stop.”

Navigating Boston’s transit system can be challenging for any commuter. But for blind riders, like Ms. Becker, each bus stop and train platform presents a unique challenge.

GPS technology is only accurate to within 30 feet or so – not a problem for sighted commuters, but that “last 30 feet of frustration” could mean missing the bus entirely for those who are blind or have low vision.

Funded by a $750,000 Google Grant, Becker and her colleagues at Perkins Solutions, the technology arm of the Perkins School for the Blind in Watertown, Mass., proposed BlindWays, a mobile app that provides visually impaired commuters with clues and landmarks for each stop, crowd-sourced from sighted users.

BlindWays is just one of many recent app store entries marketed toward the visually impaired. The tech industry has long offered solutions to help people with disabilities maintain their independence. But with the rise of smartphones, clunky and expensive devices designed for just one purpose have given way to more accessible – and affordable – apps.

What’s more, the near ubiquity of smartphones has made it easy for sighted users to lend a hand, making sure that apps like BlindWays stay up to date, while taking a few moments out of their day to put themselves in another person’s shoes. Since the app’s launch, volunteers have submitted some 6,000 clues for Greater Boston’s 8,000 bus stops.

Another app, Be My Eyes, which went live in 2015, establishes a direct video connection between visually impaired users and sighted volunteers. The premise is simple: Many people who are blind don’t need any actual assistance in completing their daily tasks, but merely need a little help.

A sighted volunteer might be asked to help identify which of two cans contains tomatoes. In this case, the visually impaired user can cook a meal just fine on her own – all she needs is a quick confirmation that she has the correct can. The model appears to be working; more than 540,000 volunteers and nearly 40,000 people with low vision are registered on the app.

“An elderly woman can now help a visually impaired technician set up his computer,” says founder Hans Wiberg, who has very low vision. “She doesn’t need to know a thing about computers. She only needs to read what pops up on the screen. He can do the rest.”

Early assistive technology centered on dedicated devices, which, because of the niche market, sold for hundreds or even thousands of dollars. But the smartphone, multipurpose and near-ubiquitous, has completely changed the economy of scale.

“There are larger market forces driving high-powered computation, high-quality engineering, and high-quality battery management in the smartphone market than there would be in a specialty product,” says Aaron Steinfeld, a research professor at the Robotics Institute at Carnegie Mellon University.

Cost matters when it comes to assistive technology. Only about 40 percent of adults with significant vision loss were employed in 2014, according to a report by the National Federation of the Blind, and more than 30 percent lived below the poverty line.

Perhaps just as valuable is the glimpse into the lives of people with limited vision that apps like BlindWays and Be My Eyes offer.

“The reality is, most sighted people don’t know somebody [who is] blind,” Becker says. “They think the solutions that a blind person needs are far more expansive and expensive than, it turns out, they need to be. I think these apps are enabling sighted people to see that blind people just need some simple clues to help them do any number of things in their lives.”

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Redirecting Myanmar’s dominant faith to peace

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By The Monitor's Editorial Board

Many Buddhists in Myanmar (Burma) see their faith as inherently peaceful. But some also fear that it is in jeopardy, and consider Muslims to be a threat. They make little distinction between the many members of the country’s Muslim Rohingya community who espouse peace and those few who have turned to violence. A few monks, as well as the military, have fed off this prejudice to create a brand of “Buddhist nationalism” that mixes the country’s religious and civic identities. The solution, says a new report by the International Crisis Group, is for Myanmar’s civilian government to reframe the place of Buddhism in a democratic society and to set forth a “positive vision.” This means that the civilian leader, Aung San Suu Kyi, and her party must offer a higher moral alternative to young people than the path promoted by Buddhist nationalists. Such radical nationalists gain support by providing youth with “a sense of belonging and direction in a context of ... few jobs or other opportunities...,” the ICG report states. The more the government can give people control over their economic destiny, the less they will look to Buddhist nationalists or cheer suppression of the Rohingya.

Redirecting Myanmar’s dominant faith to peace

According to a global ranking, Myanmar (Burma) is one of the most generous countries in terms of donating and volunteering, a result of a type of Buddhism practiced by a majority of Burmese. Yet this expression of outsize giving is not the image of Myanmar lately portrayed by its military’s harsh treatment of the minority Muslims. Is there a way that Buddhists in Myanmar can extend their compassion to the people of another faith?

The simple answer is yes, at least according to the Dalai Lama, spiritual leader of Tibet’s Buddhists. On Sept. 8, he said those persecuting Muslims in Myanmar “should remember Buddha,” who “would definitely give help to those poor Muslims.”

Yet such advice is still not being widely heeded in Myanmar. On Sept. 11, the United Nations accused the military, which controls key parts of the civilian-led government, of carrying out “a textbook example of ethnic cleansing” against Muslims, who call themselves Rohingya. Since late August, hundreds of thousands of Rohingya have fled the country. The latest exodus is the result of an assault by the armed forces after a new militant group, the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army, attacked government outposts, killing more than 100.

Many of Myanmar’s Buddhists, who have long feared that their faith is in jeopardy, consider Muslims to be “terrorists” or a social threat. They make little distinction between the vast majority of Rohingya who espouse peace and the violent few who have lately turned to fighting discrimination and oppression. A few monks as well as the military have fed off this prejudice to create a brand of “Buddhist nationalism” that mixes the country’s religious and civic identities.

The solution, according to a new report by the International Crisis Group, is for Myanmar’s civilian government to reframe the place of Buddhism in a democratic society and to set forth a “positive vision.” This means that the civilian leader, Aung San Suu Kyi, and her National League for Democracy party, must offer a higher moral alternative to young people than that promoted by Buddhist nationalists. These radicals gain support by providing youth with “a sense of belonging and direction in a context of rapid societal change and few jobs or other opportunities...,” the ICG report states.

Many Buddhists in Myanmar see their faith as inherently peaceful and non-proselytising. But they also then see it as susceptible to oppression by more aggressive faiths, the ICG points out. This feeling is compounded by Myanmar’s colonial history and the rise of militant Islam around the world.

While Ms. Aung San Suu Kyi commands respect and support, she is widely seen as backing liberal ideas promoting minority rights without doing enough to protect the Buddhist faith. Dealing with the historical fears of Buddhists – even though they are more than 80 percent of the population – might help reduce their fears of Muslims.

“In Myanmar’s new, more democratic era, the debate over the proper place of Buddhism, and the role of political leadership in protecting it, is being recast,” the report states.

The more the government can give people control over their economic destiny, in other words, the less they will look to Buddhist nationalists or cheer military suppression of the Rohingya.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

God's guidance in the storm

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By Charlene Anne Miller

People have to make decisions with far-reaching consequences when facing storms like hurricanes Irma and Jose. To many, the vivid Bible accounts of turning to God for direction in storms and turmoil have helped them seek and find the guidance they require. For one contributor the inspiration that God protects all proved practical when after praying, she felt led to move out of her building earlier than planned. Not long after, a tree destroyed the property during a hurricane and no one was injured. She saw that a humble willingness to rely on God brought protection and is a help today for those in need.

God's guidance in the storm

Many decisions with far-reaching consequences have to be made when facing the prospect of severe weather conditions, or if trapped within them. How can we ensure we choose the right way to respond?

There are many proofs in the Bible of God’s presence and power that have been deeply inspiring to me. For example in the book of Acts, St. Paul prayed for guidance before sailing from Crete to Italy. He then urgently warned the ship’s owner and Julius, the centurion, that the voyage would be disastrous unless delayed. But the ship sailed anyway, right into a violent storm. Yet Paul’s courage and confidence in God remained indomitable. Two weeks of storms passed. Then after earnest prayer, he encouraged everyone, telling them that an angel of God, a divine message, had told him that the ship itself would be lost to the storm, but the 276 men aboard – prisoners like Paul, crew, and soldiers – would all be safe. From this point on, Julius and the others heeded Paul’s orders and survived shipwreck (see Acts 27).

In studying such healing works recorded in the Bible, Christian Science founder Mary Baker Eddy discerned a higher law of God, Spirit, that liberates us from material laws and fears. This understanding of divine law clearly shows that the divine Mind, God, is tenderly governing and embracing all and that as we humbly, obediently listen for the direction and guidance of this all-knowing Mind, our footsteps are guided.

This perception of God’s ever-present, sheltering care for each of us as His dear children has deepened in me over the years. I’ve found that the constancy of divine Love’s care is expressed in the precision of perfect Mind’s guidance.

An example of this occurred several years ago when I lived in Florida. Tropical storms and hurricanes swept through Tallahassee. As a new resident, it was unnerving to see nearby trees being whipped and lashed by the wind. But as I turned wholeheartedly to God in prayer, I remembered how Christ Jesus had been able to rebuke wind and wave, restoring calm and normalcy (see Matthew 8:26).

I affirmed that nothing and no one could be outside the order, harmony, and security of God’s perpetual care. Where ferocity and violence appeared to be holding sway, the tender power of divine Love was already there keeping us safe.

Right at the beginning of hurricane season, I was preparing to move from my rented home when the sellers of the home I was purchasing had a change of plans and moved out earlier than expected. I wondered whether I should remain where I was until the end of my lease or also move earlier than planned, so I prayed for guidance.

Quickly the answer came as a clear angel message: Move! I notified my landlady of the change in plans and she kindly encouraged me, saying that this would give her time to make some repairs before new tenants moved in.

I have to admit that this was not the path I was hoping for at the time. But the spiritual discernment that prayer gives helped me see clearly that the right step in this case was to move immediately, not stay the course.

I set aside the impulse to rely on human will and planning, and resolved to let God wisely, lovingly, and intelligently order my steps. Soon the details fell into place, and I was in my new home ahead of the original schedule.

A few days later, my former landlady called me to say that a large tree had fallen onto her rental property, and she was grateful that the home was vacant! Her insurance covered the damage, and because the home was empty, nobody had been in danger.

I was so grateful that I had listened to the angel message to move early, and I felt in awe of divine Love’s complete care for each of us. It is further proof to me that every individual is forever one with divine Love, God, and eternally under the protection of ever-operative divine law. We can seek God’s guidance and experience this right where we are.

This article was adapted from an article in the Aug. 21, 2017, issue of the Christian Science Sentinel.

A message of love

Day of remembrance

A look ahead

Thanks for reading. Tomorrow, we’ll be looking at what it takes to rehabilitate gang members in a country like El Salvador, where gang violence is endemic and deeply rooted. Along the way, evangelical churches have become one of the main actors.