- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Monitor Daily Intro for October 6, 2017

The choice of a Nobel Peace Prize winner can be pointed. It can also be poignant.

In the run-up to Friday’s announcement there were rumors that some of the architects of the Iran nuclear deal might be named this year. On Thursday the White House had made noises about decertifying that deal.

But the Norwegian Nobel Committee in Oslo instead awarded a coalition of nongovernmental organizations, the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons (ICAN). It’s not common for organizations to win.

“We’re not kicking anyone in the legs with this prize,” said the committee’s chairwoman. Still, the award was, as one report put it, a “blunt rejoinder” to recent geopolitical posturing from several quarters.

Said Beatrice Fihn, ICAN’s executive director: “The laws of war say that we can’t target civilians. Nuclear weapons are meant to … wipe out entire cities. That’s unacceptable and nuclear weapons no longer get an excuse.”

It’s an aspirational message reflecting a fundamental value: respect for human life. Can it be as persuasive as the plaintive case-making that led to treaties banning chemical and biological weapons, cluster bombs, and land mines?

Now to our five stories for your Friday, highlighting grit, collective purpose, and optimism in action.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

In San Juan, pitching in and building back up

There's no glossing over Puerto Rico’s devastation. But a report from the capital – as our writer prepares to push into more-remote regions – finds a remarkable community spirit now stirring.

More than two weeks after the one-two punch of hurricanes Irma and Maria, almost 90 percent of Puerto Ricans remain without power. Just over half have running water. Most schools will remain closed until at least Oct. 23, as many continue to serve as shelters for those left homeless. But Puerto Rican society is starting to mirror in some degree the island’s jarring post-Maria landscape, where the gray-brown of denuded tropical trees is already being overtaken by the iridescent green of emphatic new growth. In San Juan, the capital, more lights are back on every day. Restaurants still shuttered a week ago are bustling again, serving up inviting platters of food. At the once lush campus of the University of Puerto Rico, the 2,500 volunteers assembled to clean up were just one example of what some say is a new community spirit. “This college is really the only place I can call home, so it’s important to me that it is repaired and starts working again,” says Paula Paulino, an art history major. “We want to feel like we’re part of putting back together something we love.”

In San Juan, pitching in and building back up

When Paula Paulino saw the destruction that hurricane Maria left in its wake at the once-lush Rio Piedras main campus of the University of Puerto Rico, she felt empty and lost.

But then the art history major picked up a rake. She joined an army of students, parents, alumni, and faculty helping to clear fallen trees and gather the debris of the 100-year storm that walloped the university as it did the entire island.

And suddenly she found herself feeling hopeful, that maybe everything wasn’t lost after all.

“This college is really the only place I can call home, so it’s important to me that it is repaired and starts working again,” says Ms. Paulino, sporting a t-shirt reading “mi casa, mi iupi” – roughly “my house, my university.”

“I think if so many students and others came out to help,” she adds, “it’s because we want to feel like we’re part of putting back together something we love.”

There can be no varnishing over of Puerto Rico’s broken state.

More than two weeks after the unprecedented one-two punch of hurricanes Irma and Maria, almost 90 percent of Puerto Ricans remain without power. Just over half the population now has running water. Thousands of homes were destroyed, while thousands more lost roofs and windows.

Most schools will remain closed until at least Oct. 23, as many schools continue to serve as shelters for those left homeless. And an already anemic economy will likely take a $40 billion gut punch from Maria, economists estimate, as thousands of businesses from mom-and-pops to large enterprises remain closed indefinitely.

Even many of the disaster-hardened recovery professionals operating out the FEMA command post at San Juan’s convention center say they’ve never seen anything quite like Puerto Rico, post-Maria.

“This is a unique situation, one I can tell you I’ve never experienced,” says a member of the Arizona National Guard’s famed Copperheads, who requested anonymity since he was not authorized to speak for his unit.

“You had two hurricanes one right after the other, and almost a third until it veered off, and all that made for very complicated logistics as units got in place but then had to shelter to be able to respond when it was all over,” says the airman, one of the 11,500 personnel the Department of Defense and FEMA have assembled here. “I don’t think people understand that this is an effort that’s been going on for a month.”

New growth

Or as Puerto Rico’s governor, Ricardo Rosselló, said Thursday when asked for the millionth time if the island wasn’t indeed “paralyzed” and if the recovery effort hasn’t fallen short, “Do we need to do more? Yes we do. And will we continue to improve our response and do more, yes we will.”

He then added, “Let’s not forget, we had two category 4 and 5 hurricanes within a span of two weeks.”

Surely none of the 3.4 million American citizens of this United States territory is at risk of forgetting any time soon.

But at the same time, Puerto Rican society is starting to mirror in some degree the island’s jarring post-Maria natural landscape, where the ghostly gray-brown of wind-slashed and denuded tropical trees is already being overtaken by the iridescent green of emphatic new growth.

In San Juan, more lights are back on every day, as it is here, in the capital, that the 10.7 percent of island residents with power are clustered. Restaurants still shuttered a week ago are bustling again, serving up platters of roasted chicken, yucca, plantain, and dirty rice.

Community spirit

The 2,500 volunteers who assembled to clean up the University of Puerto Rico were just one example of the community spirit that some here say they’ve seen grow since calamity hit.

“I know there are people like President Trump who say the people here just want everything to be done for them, but I feel like it’s the citizens, and a lot of them young people, who are getting out and getting the recovery done,” says Natalie Sierra, a drama major working alongside Ms. Paulino. “We feel like Puerto Rico has given us a lot, and we want to give back.”

The island’s ports are now running at about 60 percent of capacity, with Mr. Rosselló pledging to reach 80 percent of capacity by the end of the month. More offloaded containers mean that more products like electrical generators can come to the rescue of an island that isn’t likely to see power fully restored until sometime next year.

And to the relief of almost everyone, lines for gasoline have shrunk, and more banks and ATMs are open in what has largely reverted to being a cash economy, as credit card terminals remain down.

Perhaps most of all, people are grateful for the relatively low mortality for such a monstrous calamity, a factor Mr. Trump highlighted when he visited the island Tuesday. On Friday Rosselló put the storm’s toll at 36.

Even in capital, signs of distress

Still, one doesn’t have to leave the capital to find sign of distress. This week the residents of San Juan’s Playita neighborhood made the news when they hung banners from adjacent expressway overpasses crying, “SOS, Playita needs food and water.”

But clearly conditions worsen the farther one goes from San Juan’s restored lights.

In the town of Naguabo, about 60 miles from the capital on the island’s eastern edge, a steady stream of residents stop to fill jugs and repurposed liter soda bottles at a stand pipe installed by the local water authority.

“We get a different story every day about why we still don’t have water in our neighborhood, but the latest one we heard is that they don’t have the diesel to run the generators to get the pumps going again,” says Vidar Arroyo, who is standing by as his wife and daughter fill one bottle after another at the pipe. “I guess they’re doing what they can,” he adds, “but it seems like it’s taking a long time for things to improve.”

The unemployed used car salesman says that he depends on food stamps, like many in his area, but he worries that none of the nearby markets are able to process the debit cards that the government issues to provide food assistance.

Depending on one another

In the absence of government services, from water to schools and food stamps, Mr. Arroyo says people are turning to and depending more on one another.

“There is a spirit of ‘We are in this together’; I know in our neighborhood everyone pitched in to cut down fallen trees and clear the roads,” he says. “And that’s been great, but there are things we can’t do – like put back the electric lines or make the water pumps work.”

Another type of spirit – the entrepreneurial variety – is on display down the road, where Richard Felix and his young son Richardy are busy selling large plastic containers to passers-by.

Mr. Felix has seen his work at a steel and plastics company reduced to 20 hours a week in the wake of Maria, so he decided to try making up for lost income by buying and then selling at a profit the containers sitting unsold at his place of employment.

“When things get rough like they are now, you have to find ways to get by,” he says.

Fear of rising emigration

Felix says that so far he’s making enough to hold on and see if what he considers to be a slow recovery pace starts to pick up steam. But Rosselló says he worries that Maria will turn what was already a rising emigration from the island to Florida and other states into a stampede.

“The problem of the exodus could accelerate as a result of this situation, and it could become a serious issue, not just for Puerto Rico but for the United States,” the governor says.

Indeed Puerto Rico’s population fell from almost 3.8 million in 2007 to 3.4 million last year, with some demographers projecting another 100,000 or more leaving this year – perhaps a third of those the result of Maria.

Back at the Naguabo water pipe, Amelia and Angel Gravlau say they know well the push and pull of their island’s relationship with the US – all five of their children now live in the States.

“After this hurricane they all said, ‘Now you really must come over here to live,’ but how can we,” says Amelia, filling a jug. “We have our home here.”

Share this article

Link copied.

Big Tech, misinformation, and calls for a new era of oversight

As social media and tech giants confront the manipulation of their political content, they’re finding that their cold, algorithm-driven approach may need to be tempered by social responsibility.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

For the internet’s giant social platforms, this is a moment of reckoning. Facebook is drawing scrutiny for the way Russian efforts to sway US voters found wide dissemination in 2016. So is Twitter. And Google, as a venue where people search for news, has recently come under fire for a different reason – for promoting a report that falsely identified the Las Vegas mass shooter and alleged his liberal politics were a motivation. As such challenges become clearer, solutions aren’t easy. Improved algorithms? Hiring more humans at these firms to keep watch? What role should government oversight play, and what steps would help web users keep their own mental guards up? All that will be up for discussion, including at a coming public congressional hearing for executives from these firms. “There is nothing unethical about companies delivering a product or service consumers demand,” says Daniel Castro of the Information Technology and Innovation Foundation. “But that does not mean that we cannot instill more ethics in how users share content,” or crack down on foreign influence in elections, he says.

Big Tech, misinformation, and calls for a new era of oversight

The day after the 2016 presidential election, Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg was asked whether social media had contributed to Donald Trump’s win.

“A pretty crazy idea,” he responded at the time. But after months of internal sleuthing by media organizations, congressional investigations, and Facebook itself, the idea doesn’t look so far-fetched.

“Calling that crazy was dismissive and I regret it,” Mr. Zuckerberg wrote in a Facebook post last week. “We will do our part to defend against nation states attempting to spread misinformation and subvert elections. We'll keep working to ensure the integrity of free and fair elections around the world, and to ensure our community is a platform for all ideas and force for good in democracy.”

It is a startling turnabout. After years of defending themselves as communications networks, whose sole aim is to foster dialogue, social media companies like Facebook and Twitter are under increasing pressure to take responsibility for the content they carry. Search-engine giant Google is under similar pressure to reform after it, too, has promoted fake news stories, including extreme right-wing posts misidentifying the Las Vegas shooter and calling him a left-winger.

The proliferation of fake news is forcing these companies to rethink their role in society, their reliance on cheap algorithms rather than expensive employees, and their engineer-driven, data-dependent culture in an era when they are increasingly curating and delivering news.

“This is definitely a crisis moment for them,” says Cliff Lampe, a professor and social media expert in the School of Information at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. “They’re just trying to do their business. What they don’t understand is that in the huge panoply of humankind, people are going to try to manipulate that business for their own ends.”

Ads linked to Russian group

It’s clear that Facebook was aware that something was afoot with fake campaign stories as early as June 2016, when it detected a Russian espionage operation on its network and alerted the FBI, according to a Washington Post report. More hints of Russian activity popped up in the following weeks. Facebook's lengthy internal investigations have hit some paydirt, after the firm decided to narrow its search rather than try to be comprehensive.

This week, Facebook handed over to congressional investigators more than 3,000 ads that ran between 2015 and 2017 linked to the Internet Research Agency, a Russian social media trolling group.

Some of the ads are drawing particular interest because they targeted pivotal voting groups in Michigan and Wisconsin, where Mr. Trump won narrowly. Investigators will probe to see if the Trump campaign played any role in helping the Russians target those ads.

But experts suspect the company has only scratched the surface. And the problem stretches beyond Facebook.

An unusual Twitter torrent

During the Republican primaries, Ron Nehring noticed something odd about his Twitter feed. The campaign spokesman for presidential hopeful Sen. Ted Cruz could go on cable television and bash any of Mr. Cruz’s rivals without any social media blowback. But when he criticized Trump, his Twitter account would be deluged by a torrent of negative and “extremely hysterical” tweets.

“The tone was always extremely hysterical, not something that I would see from typical conservative activists,” he said at a Heritage Foundation event this week.

It is tempting to say that Russia simply manipulated right-wing social media to support Trump’s candidacy. The reality is stranger than that. While a preponderance of the fake posts promoted Trump or criticized his Democratic opponent, Hillary Clinton, on websites crafted to attract right-wing voters, some of them also appeared on sites catering to left-wing causes, such as Black Lives Matter, and religious ones, such as United Muslims of America.

“The U.S. left (liberal) vs. right (conservative) political spectrum was not appropriate for much of this content,” Kate Starbird, a University of Washington professor and researcher of Twitter fake news, wrote in a blog this spring. “Instead, the major political orientation was towards anti-globalism.”

Different groups defined globalism differently, but it attracted extremists on both sides of the political spectrum.

An overt attack on trust itself?

And beyond the outcome of any specific election, Russia’s aim may be to sow divisions among Americans (and indeed citizens in other countries, especially in Eastern and Central Europe), Professor Starbird says.

In one sense, none of this is terribly new. Americans have at times been virulently divided, for example, during the American Revolution, the Civil War, and the Vietnam War. And fake news has been around since before ancient Rome. Not all of the fake material has an obvious Russian connection.

And some say the Kremlin has meddled in other nations' elections in an attempt to foster distrust in their institutions.

“Since at least 2008, Kremlin military and intelligence thinkers have been talking about information not in the familiar terms of 'persuasion,' 'public diplomacy' or even 'propaganda,' but in weaponized terms, as a tool to confuse, blackmail, demoralize, subvert and paralyze,” the Institute of Modern Russia, a nonprofit think tank in New York, concluded in a 2014 report. “The aim of this new propaganda is not to convince or persuade, but to keep the viewer hooked and distracted, passive and paranoid, rather than agitated to action.”

The social multiplier

What is new is the scale of Russian meddling and the dramatic shift of political dialogue to social networks, which until very recently clung to the idea that enabling unfettered communication by everyone was an unqualified good, even if it meant giving voice to conspiracy theorists, racists, anti-Semites, and Russian provocateurs.

The reach and speed of these networks make it easy for these ideas to spread before they can be debunked. Facebook claims to have 2 billion users, or nearly a third of humanity. During the last three months of the presidential election, the top 20 fake election news stories on Facebook generated more shares, reactions, and comments on Facebook than the top 20 pieces from major news outlets, such as The New York Times, The Washington Post, and others, according to a BuzzFeed News analysis.

Among the most popular fake news stories, one said Ms. Clinton sold weapons to the so-called Islamic State and another one claimed the pope endorsed Trump.

And the meddling continues. Sen. James Lankford (R) of Oklahoma, a member of the Senate Intelligence Committee, said Russian internet trolls last weekend sought to use a recent furor over NFL players and the anthem to further divide Americans.

Part of the challenge lies in these digital giants’ reliance on algorithms to make complex news decisions. Computer programs are cheaper than real-life editors. They also offer political cover.

Facebook has used human editors in the past. But after Gizmodo reported that former employees routinely suppressed conservative news stories from users’ trending topics, Zuckerberg met with conservative editors and moved back to algorithms.

But the algorithms are far from neutral. Until exposed by reporters, they allowed advertisers to exclude minorities from seeing ads and, until last month, target “Jew-haters.” A more subtle and endemic problem is that the algorithms are geared to support social media’s business model, which is to generate traffic and engagement.

In 2014, after protests broke out in Ferguson, Mo., over the police shooting of a black teenager, social media researcher Zeynep Tufekci, at the University of North Carolina, noticed that her unfiltered Twitter feed was full of stories about the incident. But they were nowhere on her Facebook feed. When she disabled Facebook’s algorithm, she discovered her friends were indeed talking about the issue, but the topic was not algorithm friendly.

“It’s not likable,” she told a TedSummit audience last year. “Who’s going to click on ‘Like’? It’s not even easy to comment on.” Instead of the Ferguson protests, a dominant theme in regular news coverage that week, Facebook highlighted the ALS Ice Bucket Challenge, which was far more likely to be shared, she said.

Seeking a balance on oversight

Another challenge is that even as social networks become mainstream purveyors of news, they’re still largely run by engineers who rely on data rather than editorial judgment to choose newsworthy content. That data-first mentality powers profits because it gives customers exactly what they want. But if they want fake news that supports their worldview, is it ethical to give it to them?

“There is nothing unethical about companies delivering a product or service consumers demand,” Daniel Castro, vice president at the Information Technology and Innovation Foundation, writes in an email. Major social networks have policies about hate speech and already limit some adult content. “But that does not mean that we cannot instill more ethics in how users share content, teach people to be more critical media consumers, or create digital spaces where substantiated facts have more authority than unsubstantiated opinions.”

Already, Facebook has developed a specialized data-mining tool that it deployed during the French elections this past spring, helping the company identify and disable 30,000 fake accounts. The tool was used again in last month’s German elections to help identify tens of thousands of fake profiles, which were deleted.

Last month, Zuckerberg pledged to “make political advertising more transparent” on Facebook, including identifying who pays for each political ad (as TV and newspapers already do) and ending the practice of excluding certain groups from seeing ads.

Government has a role to play, too, says Mr. Castro. “Foreign interference in elections, that's the kind of thing we should look closely at ... and prohibit.”

West Africa’s would-be migrants find a new challenge back home

Turned back at Europe’s gates, some find themselves positioned to take frontline roles in helping to heal the root problems that led them to leave.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

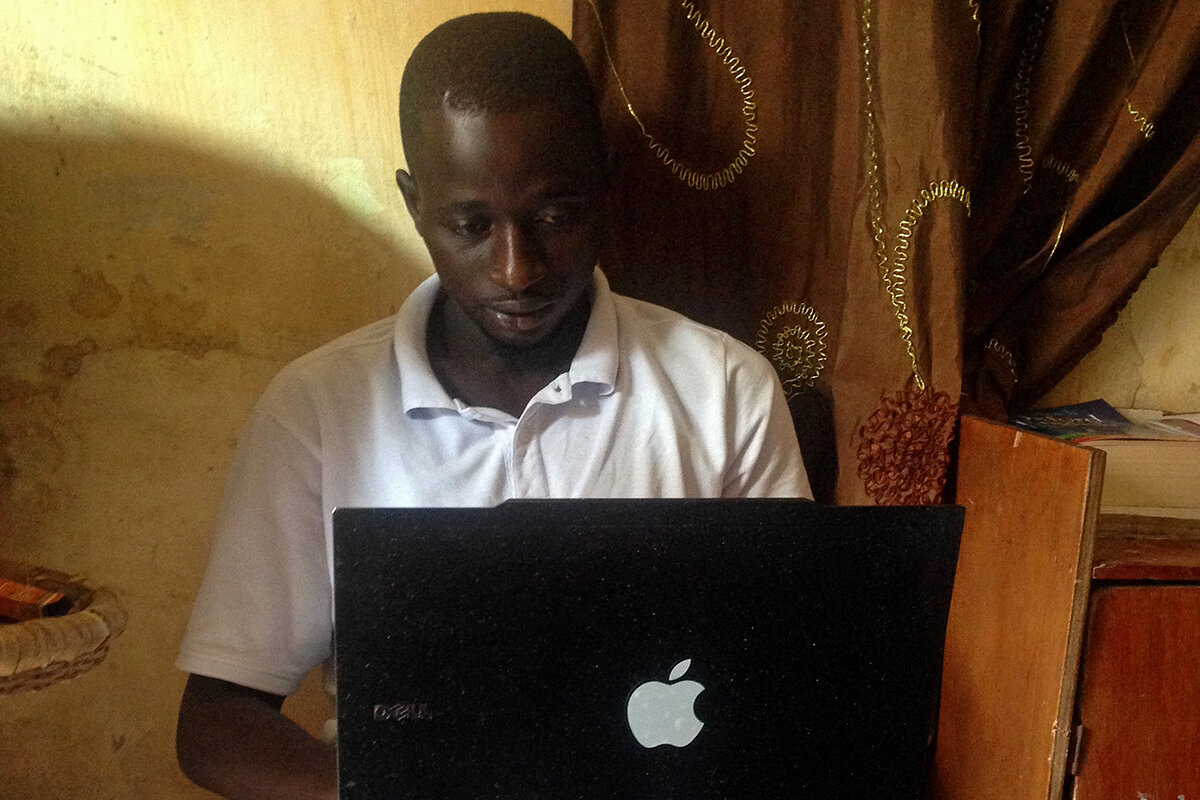

-

By James Courtright Contributor

Musa Camara spent two years trying to reach Europe. “I slept on the floor. I was hungry. I had no salary,” remembers Mr. Camara, who recently returned to his native Gambia after abandoning his dream of migration. At first, his family was happy to see him alive. But after the initial surprise wore off, they began to ask why he had come back empty-handed, while his neighbor sends money from Italy. He now lives with a friend to avoid the tension. It’s a common reaction to returned migrants, as increased barriers to Europe and increased risks along the route turn more and more back toward home, willingly or not. And it’s one reason more of them are banding together in associations. But there’s also growing recognition that returnees are uniquely poised to help solve the problems that drive migration in the first place, like youth underemployment, and educate would-be migrants about the risks ahead. “If you have a good job, you’re not hungry, and you tell people ‘Don’t migrate irregularly,’ they might not listen to you,” says one organizer. “But for us, they know that we witnessed everything.”

West Africa’s would-be migrants find a new challenge back home

Back home in The Gambia, Mustapha Sallah and Karamo Keita were strangers: the first, a computer technician; the second, a shop keeper. But like tens of thousands of other West Africans, they had a common goal: to flee grinding poverty and a lack of opportunity, find work in Europe, and send money home.

Separately, each one crossed the world’s largest desert, evaded slavers, and paid thousands of dollars to be smuggled across war-torn Libya – where they were discovered and detained by authorities, they say. The men met in a squalid Libyan detention facility in January, where they hadn’t rested, washed, or eaten properly in days.

Three months into the men’s detention, representatives of the International Organization for Migration (IOM) visited the prison and offered them tickets home. Dreams of reaching Europe had been dashed, but they had a new appreciation for their homeland. They took the tickets. And they made each other a promise: to use their experiences to illustrate the realities of irregular migration, and encourage Gambian youth to build their own country, despite the many challenges, rather than seek opportunity abroad.

Today, Mr. Sallah and Mr. Keita are the founders of Youths Against Irregular Migration (YAIM), as unauthorized immigration is called – and they’re part of a growing recognition. As Europe puts up more barriers and chaos in Libya continues, the number of migrants returning home will likely increase. Returnees face myriad challenges, from social stigma to the trauma of their difficult journeys north. But they are also uniquely equipped to help educate others about the perils of irregular migration – and have a stake in healing the root problems that led them to leave in the first place.

“This is a national issue,” says Sallah. “The youths don’t know the realities. If I had known, I wouldn’t have gone. So if we talk to the youths, even if we cannot save everybody, it will make a change.”

A lukewarm welcome

More than 2,600 people have died crossing the Mediterranean this year, according to the IOM. Even before braving the voyage, the risks are high, from sex trafficking to slave markets in Libya. The vast majority of West Africans who run this gauntlet do so because of a paucity of economic opportunity: according to the United Nations, about half of the population in Senegal and The Gambia live below the national poverty line.

“For two years I slept on the floor, I was hungry, I had no salary, I was undermined by the Arabs, and I was criminalized,” says Musa Camara, who recently returned to the Gambia, remembering his attempted journey to Europe. At first his family was happy to see him alive. But after the initial surprise wore off, they began to ask why he came back empty-handed, while his neighbor sends money from Italy. He now lives with a friend to avoid the tension at home.

It’s a common reaction. “People refuse to talk or even greet us,” says Bori Diao. Born in the southern Senegalese village of Pakour in 1978, he is slightly older than most migrants: When he started his attempt in 2015, he left his wife and three children. After a grueling journey across the Sahara in the back of a 4x4 pickup truck, he spent six months looking for work in Libya before turning around. “They tell us we were scared, that’s why we didn't continue. We used our family’s money, and we came back with nothing.”

Experiences like these, in part, drive YAIM, which seeks to end irregular migration through public awareness and increased job prospects for youth. In recent months, they have ramped up their outreach, from educational campaigns to new partnerships with the IOM, EU, and Gambian National Youth Council.

Across the border in Senegal, returnees have a longer history of organizing. Cheikh Diop, the president of the National Association of Returned Migrants, has worked with returnees for more than a decade, traveling to Niger via bus – legally – to understand the trials migrants go through. In the late 2000s, hundreds of repatriated Senegalese from Spain founded associations, he says, but interest was fleeting and many disbanded. In 2014, when migrants began coming back from Libya en masse, they began anew.

Members say they provide a comforting space. “Talking with the association helps me because they understand me,” says Adama Bah, a farmer in Saare Diallo, Senegal, who tried to cross from Morocco to Spain twice in the past decade. “When I tell others about the trip, they call us cowards. But not people in the association; they went through what I went through.”

Renewed attention

In November 2015, with the flood of irregular migration at its peak, the European Union established the Emergency Trust Fund for Africa: more than $3.6 billion pledged to build economic resilience, support good governance, and provide basic migration management – essentially, to help those on the road get home, and incentivize others to stay rather than seek their fortunes in Europe.

“There has been a growing interest in returnees since 2000,” says Marie-Laurence Flahaux, a demographer at the International Migration Institute at the University of Oxford. “But today, looking at the trust fund and all the new measures and discourses about managing migration, return has become very central.”

One of the larger initiatives funded by the Emergency Trust Fund is a 14-country program for migrant protection and reintegration. IOM already has a program in Senegal to help a handful of individual returnees start small businesses. Marise Habib, the IOM’s project manager in Senegal, says her office wants to expand the scope and utilize data already collected from interviews with returnees to provide more targeted support.

“We want to tailor the assistance that’s provided,” she says. “We also want to engage the community much more actively” in reintegration.

In Pakour, the IOM plans to provide training and start-up funding through local partners to returnees for a large-scale chicken raising business, according to Ms. Habib. The hope is that profits generated will help returnees as a whole regain social standing and provide a local example of an income-generating activity.

A positive message

International organizations can provide financial support, but when it comes to educating youth about the realities of migration, returnees themselves possess something crucial: credibility.

“If you have a good job, you’re not hungry, and you tell people ‘Don’t migrate irregularly,’ they might not listen to you,” says Sallah, of YAIM. “But for us, they know that we witnessed everything.”

And as more returnees speak out, the stigma recedes. Since he was a young boy, Trawale Balde spent every rainy season helping his family in their fields outside Pakour. He was 25 when he sneaked out in the middle of the night to go to Europe – a two-year, failed attempt that he says included being held for ransom twice and severely beaten. With more people coming back from Libya empty-handed and traumatized, he says people are beginning to understand that returning is not a personal failure.

Awareness-raising campaigns are more than graphic descriptions of the horrors migrants face. Many returnees talk about what they could have done with the time and money they spent trying to reach Europe. “Just imagine what I could have built here with the money I wasted,” laments Mr. Balde.

The Gambian Youth Empowerment Project, a joint initiative by the EU Trust Fund and the International Trade Center, is trying to harness that message. Its publicity campaigns “showcase entrepreneurs to show the alternative to irregular migration,” says project manager Raimund Moser. “Positive messaging, creating role models, and championing pride in The Gambia is very important.”

A similar approach was in action this July in Serrekunda, along the Gambian coast. Over three days, more than 80 students participated in a camp run by the nonprofit Ascend Together: three days of playing basketball, speaking with Gambian entrepreneurs, creating short skits, and hearing from YAIM returnees.

“As a Gambian, I now want to stand against irregular migration,” says camper Bintu Dambelly, age 15. “If they stay in the Gambia they can make money, have opportunities, and build our beautiful country.”

But so long as West Africans are still looking for opportunity, they will attempt the perilous voyage.

“I tried and I didn’t make it,” says Abdoulaye Bah, back in Pakour. He left home when he was 15, and didn’t return until he was 21. “But I know the world a little better, and I know I’d rather be here.”

Why world’s auto giants charge hard toward all-electrics

The pace of automotive technology is reshaping the marketplace at a rate that was not fully anticipated, and shifting thought – with some caveats – across the realm of personal transit.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

Step into any Chevy dealership, or read a headline about Tesla, and you’re likely to miss the huge shift now under way in the automobile industry. Chevy’s all-electric Bolts aren’t exactly flying off the lot. And Tesla’s vaunted Model 3 may be delayed even longer because of production glitches. Nevertheless, ever-cheaper batteries, ride-hailing companies, self-driving cars, and continued concern over climate change are pushing the staid auto industry to step up its pace toward an electric-vehicle future. General Motors is only the latest carmaker to announce that new EV models are coming beyond the Bolt and Volt. By 2025, electric drivetrains could be as cheap as internal combustion engines, according to one estimate. The move offers huge opportunities for the world’s auto companies, but also immense risk, because converting to EV car production is expensive and the timing is unpredictable. Move too nimbly and you could end up with parking lots full of unsold EVs; move too slowly and the competition will leave you in the dust.

Why world’s auto giants charge hard toward all-electrics

When General Motors pledged on Oct. 2 to launch at least 20 new electric vehicles in the next six years, it was more than the usual new-product announcement. It was a sign of how the global auto industry is being pushed toward a vision of rapid and radical change.

It came, after all, just about three weeks after news that China, the world’s largest car market, is "formulating a timetable to stop production and sales of traditional energy vehicles," according to one ministry official, as quoted by the Associated Press.

That’s a prospect global carmakers can’t afford to ignore. Yet even as China’s rising influence is inescapable, that nation’s move is rooted in something more fundamental. Technology is fast resetting the outlook for what cars can do, how consumers use them, and how much an electric vehicle (EV) will cost. The stock price of Tesla, rivaling GM’s and Ford’s market value for its perceived EV leadership, is another straw in the wind.

The realm of personalized transit is on track to be massively reshaped, and possibly at a much quicker pace than industry leaders from Detroit to Tokyo could have imagined just a few years ago.

“It is revolutionary. It is a huge, fundamental change,” says Brett Smith, a technology expert at the Center for Automotive Research in Ann Arbor, Mich. “There's a much greater understating that things are happening fast.”

GM’s announcement followed a spate of other EV commitments in recent months including by Volkswagen and Volvo, which is owned by China-based Geely. And this week other carmakers have chimed in.

Ford, often seen as a laggard in the EV push, announced a big cost-cutting effort on Oct. 3, partly with the aim of ramping up battery and hybrid gas/electric vehicles. And Honda, in similar vein, announced factory overhauls, citing an industry that “is undergoing an unprecedented and significant turning point in its history.”

It’s notable that the mood of an unstoppable transformation is building among corporations that, while all about transportation, aren’t traditionally known for agility and speed. “It's an evolutionary industry,” Mr. Smith says, “not necessarily one that does revolution well.”

At the moment, EVs account for barely 1 percent of US or global sales, and even Tesla has been struggling to ramp up assembly to meet promised deliveries for its newly launched Model 3 – aiming at a mass market with base prices around $35,000. That’s proof, if nothing else, that making cars isn’t easy.

Judging on that basis, the vaunted EV revolution is little more than a sketchpad dream. This is a challenging and cost-intensive business. Aspirations like those of Britain and France to end sales of gas-powered cars by 2040 could easily be foiled, even if manufacturers try to deliver.

But here’s what’s changed.

“Technology is getting cheaper,” says Genevieve Cullen of the Electric Drive Transportation Association in Washington, a group promoting electric, hybrid, and fuel-cell vehicles.

In particular, the falling cost of lithium-ion batteries brings a tipping point into view. By 2025 or even sooner, it’s possible that electric drivetrains will have no cost disadvantage compared with internal combustion engines, according to analysis by Bloomberg New Energy Finance, an energy research group.

That’s vital, because even with consumers who are interested and governments promoting a switch over, affordability matters a lot. Auto customers, from families to businesses with fleets, need transportation that doesn’t break the bank.

When that tipping point is reached, the EV share of overall car sales could quickly skyrocket.

What makes things even wilder, for consumers and carmakers alike, is that the trend toward electric drivetrains will be coinciding with other tech-related changes. The rise of ride-sharing services like Uber and Lyft, as an alternative or supplement to personal ownership, won’t go away. Nor will the trend toward cars with growing ability to drive themselves.

Internationally, the push to dampen climate change by limiting auto and other carbon-based emissions is also demonstrating staying power.

These trends present vast opportunities. GM chief executive officer Mary Barra is eyeing a goal of “zero crashes, zero emissions, and zero congestion.”

But it also comes with risks and uncertainties.

“Nothing is inevitable in the near term,” Ms. Cullen says.

The safe thing for the auto giants is not to be caught flat-footed if and when the crossover happens. But that kind of “safe” carries lots of risk. The speed will depend on everything from pricing and consumer tastes to likely glitches as automakers face both fierce competition – including from new entrants – and the need for billion-dollar factory investments.

“Are there enough batteries?” asked Michael Liebreich, head of Bloomberg New Energy Finance, at a presentation in September. Despite abounding doubts today, he said “the answer is, there will be. There will be a huge investment in the supply chain. There's no natural limitation of availability of those elements.”

He projected that EVs will reach 54 percent of new-car sales by 2040, and soar still higher after that. Some other forecasters offer a similar outlook.

Already it’s clear that partnerships will be a path toward sharing the risks and costs. China may become not just a locus of EV demand but of production for export. But the transformation won’t necessarily be smooth or profitable, or its pace easily predictable.

“There's some balance between what consumers will accept and what regulators will require,” says Mr. Smith in Ann Arbor. If the two aren’t well enough aligned, “there can be some spectacular wipeouts here.”

Yet a shift has happened deep in the bowels of companies like GM, he says. Engineers who a few years ago didn’t see EVs as cost-competitive now seem open. “More and more people are saying it might happen.”

Dystopia redux: ‘Blade Runner’ reboot as a cultural yardstick

Futuristic fiction can reflect a society’s despair, which it can magnify even in times of human progress. But now there’s a growing argument for instead using it to urge optimism and vision.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

-

By Stephen Humphries Correspondent

Recent dystopian blockbusters, like the eagerly awaited “Blade Runner 2049,” seem to be jostling in a grim race to be the first to reach the seventh circle of hell in Dante’s “Inferno.” But some science fiction writers are tired of the sorts of pessimistic futures depicted in movies and TV shows such as “Mad Max: Fury Road,” “Black Mirror,” and “The Handmaid’s Tale.” In response, authors such as Neal Stephenson and Cory Doctorow argue that futuristic fiction should, instead, offer an inspiring outlook about mankind’s ability to shape its destiny. But do the kinds of stories we tell ourselves have a cultural impact on shaping a better tomorrow? “The utility dystopian fiction used to serve was to bring problems to our attention and seek solutions. But the danger is that these stories can become a collective act of despair in response to current events,” says Christopher Robichaud, who teaches a class at the Harvard Extension School on utopia and dystopia. Wondering whether the pessimistic outlook of his profession had contributed to a defeatist attitude and lack of ambitious vision, Mr. Stephenson cofounded Project Hieroglyph to develop science fiction stories with optimistic thought models and imaginative blueprints. The theory is that these narratives will, in turn, inspire scientists, engineers, and entrepreneurs to tackle major projects.

Dystopia redux: ‘Blade Runner’ reboot as a cultural yardstick

In “Blade Runner 2049,” which opens Friday, post eco-disaster Los Angeles has built a massive coastline wall to fend off rising ocean levels. Few of the overpopulated city’s human or android occupants have ever seen a tree or a real animal. The incessant rain is as dour as Harrison Ford’s facial expressions. Worst of all? One character bemoans the fact that there’s no more cheese in the world.

Recent dystopian blockbusters seem to be jostling in a grim race to be the first to reach the seventh circle of hell in Dante’s “Inferno.” But some science-fiction writers are tired of the sorts of pessimistic futures depicted in movies and TV shows such as “The Hunger Games,” “Mad Max: Fury Road,” “Black Mirror,” and “The Handmaid’s Tale.”

In response, influential authors Neal Stephenson, Cory Doctorow, David Brin, and Kim Stanley Robinson argue that futuristic fiction should, instead, offer an inspiring outlook about mankind’s ability to shape its destiny. But do the kinds of stories we tell ourselves have a cultural impact on shaping a better tomorrow?

“I want to nod at something that Jill Lepore wrote in The New Yorker about the dangers of drowning ourselves in dystopian stories,” says Christopher Robichaud, who teaches a class at Harvard Extension School on Utopia and Dystopia in fiction and philosophy. “The utility dystopian fiction used to serve was to bring problems to our attention and seek solutions. But the danger is that these stories can become a collective act of despair in response to current events.”

The long-awaited sequel to the original “Blade Runner” certainly seems inspired by present-day concerns. It’s eerily in sync with Space X and Tesla founder Elon Musk’s claim that artificial intelligence will come to view humanity as an inferior species and destroy us. “Blade Runner 2049” also predicts bad outcomes from genetic editing, neurotechnology, surveillance technology, and energy use. The future’s only bright spot, it seems, is for umbrella manufacturers.

That sort of thinking made Mr. Stephenson wonder whether the pessimistic outlook of his profession had contributed to a defeatist attitude and lack of ambitious vision among scientists. So, in 2011, the author of classics such as “Snow Crash” cofounded the Hieroglyph project with the Center for Science and the Imagination at Arizona State University. The big idea: Develop science fiction stories with optimistic thought models and imaginative blueprints. The theory is that these narratives will, in turn, inspire scientists, engineers, and entrepreneurs to tackle major projects such as designing crewed spacecraft or finding viable alternatives to fossil fuels.

“When most people think of the future today, they think of the great dystopian narratives, especially through Hollywood and popular culture,” says Ed Finn, co-editor of the project’s 2014 anthology, “Hieroglyph: Stories and Visions for a Better Future.” “We started to ask how we can use storytelling to create more optimistic futures that are more empowering to people.”

'No such thing as defeating the technology'

But some science-fiction writers, including Ramez Naam (“Nexus”) and Daniel H. Wilson (“Robogenesis”), counter that dystopian tales can be just as valuable in shifting thought paradigms. Case in point: Mr. Wilson’s “Robopocalypse,” a story about a machine uprising so terrifying that readers may decide to leash their Roombas.

“I used that meme as a red cape to get the bulls to chase me,” says Mr. Wilson. “My goal was to subvert that theme. What I wanted people to take away from ‘Robopocalypse’ is that there is no such thing as defeating the technology. We are technology. We don’t survive without technology.”

And while novels such as Emily St. John Mandel’s “Station Eleven,” Maja Lunde’s “The History of Bees,” and Ernest Cline’s “Ready Player One” offer little respite from apocalypse, they’ve won both critical and popular acclaim.

Science fiction often plays on fears of technology’s unintended consequences. It’s a trope as old as Mary Shelley’s “Frankenstein.” Virginia Postrel, author of “The Future and Its Enemies: The Growing Conflict over Creativity, Enterprise, and Progress,” argues that optimistic science fiction stories don’t create a belief in technological progress. Rather, they reflect an existing, broader cultural outlook.

“If you think that the present is better than the past because of science and technology, then you are much more likely to find optimistic science fiction about the future to be plausible,” says Ms. Postrel. “If you think that science and technology have done nothing but destroy the planet and ruin our health, you will be drawn to pessimistic science fiction.”

Indeed, one puzzling aspect of dystopian science fiction is why stories about dismal futures are so popular during an era of unprecedented human progress. Global poverty is declining, infant mortality rates are falling, and life expectancy is rising.

“People refer to the Golden Age of sci-fi, which was a time of [Robert] Heinlein and ‘Star Trek’ and ‘The Jetsons,’ which reflected a fairly robust belief in the possibility of progress and that things will get better in the future,” says Ron Bailey, author of “The End of Doom: Environmental Renewal in the 21st Century.” But, he says, the new wave of science fiction after the mid-1960s reflected fears of nuclear annihilation, the loss of faith in institutions following the Vietnam War and “a relentless dystopian campaign by ideological environmentalists.”

'The importance of hope'

But perhaps the debate over utopian versus dystopian fiction should be reframed. A more helpful distinction might be the difference between nihilism and existentialism in science fiction. Amid doom-and-gloom scenarios, does the hero or heroine have agency and an ability to win the day?

“Dystopian fiction is pleasurable because we can enter from the side of the hero and track the hero’s journey and their statement,” says William Warner, a professor of English and Comparative Literature at the University of California, Santa Barbara.

Hieroglyph contributors and supporters Mr. Robinson (“New York 2140”) and Mr. Doctorow (“Walkaway”) have each written stories set in dystopian (and thus inherently dramatic) worlds that, paradoxically, often feel utopian. Crucially, their stories don’t leave readers feeling akin to Charlton Heston at the end of “Planet of the Apes.”

“New York 2140,” the latest book by Robinson, posits a future in which post-climate change Manhattan is partly submerged underwater. But his dystopian scenario is, in many ways, utopian. New York is flourishing as a "SuperVenice" in which, Robinson writes, “Not a few experienced an uptick in both material circumstances and quality of life.”

“Cory Doctorow likes to talk about the importance of hope – that you could hope for a better future,” says Mr. Finn. “That’s part of what differentiates our work from pure utopianism. We’re not so much focused on a perfect world. The work we do is trying to make our world better.”

Correction: The Hieroglyph project is run out of The Center for Science and the Imagination at Arizona State University.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Welcome the world’s newest welcome mat

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By The Monitor's Editorial Board

In recent weeks, Bangladesh, where a third of people live on less than $2 a day, has allowed in more than half a million Rohingya Muslims from Myanmar (Burma), people fleeing a crackdown by the Burmese military and persecution by militant Buddhist nationalists. With an estimated 4,000 to 5,000 crossing the border each day, it is the world’s fastest developing refugee crisis. Bangladesh is also one more example of a country that finds its own good in helping strangers in desperate need. Most of the world’s conflicts occur within poor countries – on the borders of other poor countries. South Sudan’s conflict, for example, has pushed a million of its people into Uganda. While Europe still sees thousands of migrants trying to reach its shores – down from the numbers two years ago – most displaced people still travel in less wealthy regions. When they are welcomed and well housed, it should be a moment of celebration.

Welcome the world’s newest welcome mat

The world has many “clubs” of nations, grouped by shared interests, but none like an unofficial one often cited by the United Nations for its generosity. It includes only a few countries, such as Uganda, Jordan, and Turkey. They have kept an open door for refugees in recent years, welcoming millions fleeing conflicts in neighboring states.

Now add Bangladesh to this “club.” In recent weeks, the South Asian country, where a third of people live on less than $2 a day, has allowed in more than half a million Rohingya Muslims from Myanmar (Burma). The refugees are fleeing a crackdown by the Burmese military and persecution by militant Buddhist nationalists. An estimated 4,000 to 5,000 are still crossing the border each day.

The sudden influx is now the world’s fastest developing refugee crisis. Bangladesh is also one more example of a country that finds its own good in helping strangers in desperate need.

Many richer countries, such as the United States, provide money for the world’s refugees. The UN, in fact, has appealed for $434 million in aid to assist the Rohingya camps in Bangladesh, where conditions remain dire. One in 5 of the refugee households is headed by a woman, and about 5 percent are headed by children. The situation awaits a diplomatic resolution with Myanmar, which faces international pressure to end abuse of its Muslims, who are a minority.

With so many people displaced around the world – an estimated 65 million, of which 22 million are refugees – the UN says the response to this problem not only requires more generosity from national governments but also more from private groups and individuals.

“The international character of refugee protection has taken on new forms – through networks of cities, civil society, private sector associations, sport entities, and other forms of collaboration stretching across borders,” says Filippo Grandi, UN High Commissioner for Refugees.

Most of the world’s conflicts occur within poor countries – on the borders of other poor countries. South Sudan’s conflict, for example, has pushed a million of its people into Uganda. While Europe still sees thousands of migrants trying to reach its shores – down from the numbers two years ago – most displaced people still travel in less wealthy regions. When they are welcomed and well housed, it should be a moment of celebration.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

The forward march of Science

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

Humanity has made tremendous advances – some of which have presented new challenges, from environmental degradation to artificial intelligence. Some say these could have catastrophic effects. Is that really our destiny? No. Mary Baker Eddy, founder of The Christian Science Monitor, championed invention – but also saw that human developments but foreshadow the divine. And thus humanity, in its march forward, would do well not to neglect religion. She wrote: “It will never do to be behind the times in things most essential, which proceed from the standard of right that regulates human destiny” (“Miscellaneous Writings 1883-1896,” p. 232).

The forward march of Science

Humanity has made tremendous advances over the past century. There is a prevalent thought, however, that in fields ranging from environmental science to technology, destructive forces are ascendant – with potentially catastrophic consequences. And it is said that at least some of these challenges are of our own making.

Is it our destiny to be doomed by our own invention, innovation, and entrepreneurship? No. Each one of those qualities, seen in a spiritual light, reflects the wisdom of God. Our tools for overcoming human challenges aren’t limited, then, to the improvement of material modes, but can come from a more spiritual view of God and His creation.

Mary Baker Eddy, the founder of The Christian Science Monitor, championed improvements in art, invention, and manufacture. But she added that humanity, in its march forward, would do well not to neglect “a more perfect and practical Christianity.”

“It will never do to be behind the times in things most essential, which proceed from the standard of right that regulates human destiny. Human skill but foreshadows what is next to appear as its divine origin,” she wrote. “Spirit is omnipotent; hence a more spiritual Christianity will be one having more power, having perfected in Science that most important of all arts, – healing” (“Miscellaneous Writings 1883-1896,” p. 232).

In the words of the Apostle Paul: “For though we walk in the flesh, we do not war after the flesh: (For the weapons of our warfare are not carnal, but mighty through God to the pulling down of strong holds;)” (II Corinthians 10:3, 4).

Surely the spiritual influences of unselfishness and love are powerful to pull down the destructive forces of greed and fear and bring healing and progress to all fields of endeavor.

A message of love

Preserving a family farm

A look ahead

Thanks for joining us today. Enjoy the weekend, and come back Monday. There's been lots of talk about the eroding role of centrists with the announced retirement of Sen. Bob Corker. If Sen. Susan Collins of Maine follows her colleague to run for governor, it will mark the departure of one of the great advocates of reaching across the aisle of the Senate. Francine Kiefer will look at the implications.