- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Monitor Daily Intro for December 8, 2017

This was a week of more reckoning, and small signs of paths forward.

On Thursday Rep. Trent Franks (R) of Arizona became the third congressman to step down within days amid charges of sexual impropriety. Gender relations could not be more fraught as male power projectors are serially held to account.

Will public attitudes support a climate that favors more such justice? A new Pew poll on perceptions around masculinity and femininity shows that while opinions break in perhaps expected ways by gender and political leanings, a majority of Americans say more should be done “to encourage girls to be leaders and to stand up for themselves.”

Justice and hope also flashed through a realm that has mostly dropped from the news cycle: race. In South Carolina, the white former police officer who shot and killed Walter Scott, a 50-year-old black man, during a traffic stop in 2015, drew a prison sentence Thursday for second-degree murder and obstruction of justice.

According to a report from the courtroom, the ex-officer, Michael Slager, turned to Mr. Scott’s mother and mouthed, “I’m sorry.” She replied: “I know.”

Will healing attitudes on race broaden, too? There’s hope in the popularity of an uplifting New York Times feature on a black 22-year-old Harlem rapper who befriended a white 81-year-old woman from Florida by way of the online game Words with Friends. Their online conversation had become about life.

The two recently met in person and embraced. Said the young man, Spencer Sleyon: “A lot of people I saw online said, ‘I needed a story like this.’ ”

Check CSMonitor.com for early takes on the "Brexit" story and other news. Now, here are our five stories for your Friday, chosen to highlight adjustment, compassion, and creativity in action.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

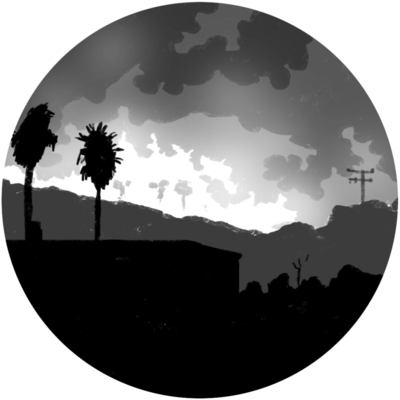

Epic Los Angeles blazes force a rethink over living with fire

When the snowflakes of ash stop falling in tinder-dry southern California, the work will turn to recovery – and then, if experts are heeded, to smart adaptation.

The wildfires ripping through southern California mark a destructive end to a year already considered the state’s worst fire season on record. Some 5,700 firefighters are battling six blazes amid Santa Ana winds. Nearly 200,000 people have been forced from their homes. This latest spate of fires is a dramatic demonstration of what scientists and fire practitioners in the region have been saying for years: that long-term trends tied to climate change coupled with increased populations in high fire risk areas could lead to more extreme fire events that affect more people than ever. Local and federal officials have in recent years sought to improve coordination among various government agencies. “We have to work better to maximize our resources and create the best working agreements we can,” says former Ventura County Fire Chief Bob Roper. But engagement with the public is equally important. He adds, “If you live in the wildland area, you have a personal responsibility to be part of the solution.”

Epic Los Angeles blazes force a rethink over living with fire

On the morning of Dec. 6, Laura Lenk woke to the sound of sirens.

She had parked for the night at a lot at the Leo Baeck Temple, a synagogue tucked into the hills of northwest Los Angeles that provides free, safe parking for people who live in their vehicles. As fire trucks whizzed by early that morning, Ms. Lenk thought there must have been an accident on the nearby 405 freeway.

Then she pulled down the sunshade she’d placed on her windshield and saw the flames.

“It looked like the whole hillside was on fire,” Lenk says, sitting at the evacuation center in Arleta, Calif., where she ended up seeking shelter. “It seemed like it was right in my face. I literally threw my cat in the carrier and drove out of there.”

The Skirball fire, which Lenk narrowly escaped, started around 5 a.m. Wednesday and burned through 475 acres in the hills near Bel Air. The blaze destroyed four homes, damaged 11 others, and forced 46,000 residents to evacuate.

It was one of six major wildfires to ignite across Southern California this week, burning 141,000 acres and causing at least 190,000 people to have to evacuate their homes, according to Cal Fire officials.

- The Thomas fire burned 115,000 acres across Ventura County, just north of Los Angeles.

- The Rye fire torched about 7,000 acres in Santa Clarita

- The Creek fire spread through 12,600 acres in the Angeles National Forest and drove 100,000 people out of their homes.

- Two new fires Thursday, the Lilac fire near San Diego and the Liberty fire, complicated efforts by some 5,700 firefighters to contain the blazes amid Santa Ana winds.

The wildfires mark a destructive end to a year already considered the state’s worst fire season on record. They’re also a dramatic demonstration of what scientists and fire practitioners in the region have been saying for years: that long-term trends tied to climate change coupled with increased populations in high fire risk areas could lead to more extreme fire events that affect more people than ever. If communities are to survive – and thrive – in these new conditions, they say, government, practitioners, and residents are all going to have to reexamine what it means to live with fire.

“We have to work better to maximize our resources and create the best working agreements we can,” says former Ventura County fire chief Bob Roper, who helped develop programs around fire prevention and response across the region and nationwide. “But the public has to be a key partner in whatever we do.”

Rapid response

A day after the Creek fire started burning, the Branford Recreation Center in Arleta was a picture of competence: Volunteers set up sleep stations and helped families settle in as the work day came to a close. Rows of cots lined the gymnasium floor. Supplies sat on tables and filled boxes. In some ways the scene epitomized the maturity of the crisis response system in a disaster-prone, dense urban area like Los Angeles.

“This is the first time I’ve had to evacuate. I really dislike it ... but I slept good last night,” says Collin Chamberlain, a Korean war veteran who made for Branford after having to leave his home in Sunland on Tuesday. “These blankets are excellent.”

“We have diapers, milk, toys, food,” adds Nancy Rodriguez, a former Red Cross staffer turned volunteer. “There’s a massive warehouse in L.A. where there are thousands of cots and blankets.”

The California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection, or Cal Fire, is also well equipped. The agency has about 5,000 professional and volunteer firefighters on staff and more than 50 firefighting aircraft in its fleet. The state’s various agencies and departments have also signed an agreement that ensures everyone participates in rescue, relief, evacuation, and recovery efforts in the event of a disaster.

But resources alone aren’t enough to combat California’s increasingly nasty wildfires, says Cal Fire information officer Scott McLean.

'Like a blowtorch'

Extreme climate conditions, including five years of drought, has led to an excess of dry vegetation that has made parts of the state more flammable than ever. In Southern California’s case, the yearly Santa Ana winds that blow in from the Great Basin in Nevada have gusted through the coast at speeds of up to 80 miles per hour for nearly a week. Those winds, combined with the lack of rainfall in the region, make for erratic fire behavior that’s difficult to contain, Mr. McLean says.

“We’re dealing with fire that’s like a blowtorch,” he says.

It doesn’t help that, as cities grow denser and the cost of living rises, more people are moving into fire-prone areas. Heath Hockenberry, fire weather program manager at the National Weather Service, points out that places like Idaho and Montana are also seeing longer concentrations of high-intensity fires.

“But those are communities of about 50, 100 people, as opposed to millions in California,” Mr. Hockenberry says. “It is a population correlation that really brings the conversation up nationally.”

Confronting a new reality together

Fire practitioners, nonprofits, and government agencies have begun to recognize this new reality. Through the early 2000s, Congress authored laws meant to catalyze fire preparedness efforts across the country. In 2013, practitioners in the West founded the Fire Adapted Communities Learning Network, which connected communities that had for years been working to address local fire issues on their own. A year later, the Obama administration released a national cohesive strategy that called on stakeholders from all levels of government and the community to address wildland fires.

There have also been efforts to more efficiently disseminate information before, during, and after fire events. Early Tuesday morning, for instance, hundreds of thousands of Ventura County residents received an emergency alert on their phones warning them that the Thomas fire was spreading. “I think that’s a dissemination victory,” Hockenberry says. “It definitely got the word out and superseded all jurisdictions.”

He adds that researchers are working to improve their ability to predict fires, especially in densely populated areas. “Hurricane warnings are designed with people and structures in mind,” he says. “We’re beginning to look at those societal impacts with fire in mind, as well.”

Still, the success of any strategy relies on continuous public participation, experts say. That means building homes that are up to code, keeping driveways and gutters free of flammable debris like dry leaves and firewood, and paying attention to changes in weather conditions.

“If you live in the wildland area, you have a personal responsibility to be part of the solution,” says Mr. Roper, the former fire chief.

Share this article

Link copied.

In Yemen, ex-dictator’s killing makes ending war harder, more urgent

Yemen is about as complicated as crises get. Mideast editor Ken Kaplan spent some quality time with this story. “Lots of ‘buts,’ ‘yets,’ and ‘howevers,’ ” Ken says. “But that’s Yemen.” Sometimes obscured by the granularity of the power game there: It’s also the site of the world’s largest food-security emergency.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

-

By Taylor Luck Correspondent

Saudi Arabia may have thought it had a face-saving way to get out of its disastrous war in Yemen. Days before he was killed, former Yemen dictator Ali Abdullah Saleh indicated he was breaking ties with Houthi rebels and was ready for dialogue with the Saudi-led coalition. But his death dashed hopes for a political deal, and the Saudis are vowing to intensify their fight. Experts warn that could exacerbate an already dire humanitarian crisis, and that neither the Houthis nor the Saudi coalition have the resources to tip the scales in the conflict. One country has been quietly leading the drive for talks: Yemen’s neighbor Oman, known for its ties to both Iran and the Saudis. It has mediated talks to implement a peace plan championed by the United Nations, but its efforts to encourage parties to lay down their arms lack powerful support. Says a Yemen expert at Oxford: “We really need to think about the grass-roots political processes that are required inside Yemen to start mending the fences…. This actually stands the chance of stopping the fighting on the ground.”

In Yemen, ex-dictator’s killing makes ending war harder, more urgent

With the killing of deposed dictator Ali Abdullah Saleh, the warring sides in Yemen have lost their main exit strategy and interlocuter, with experts warning that the parties must be brought to the negotiation table before the conflict spirals further out of control.

Days before his death, Mr. Saleh, who ruled Yemen for more than three decades, appeared to offer Saudi leaders and their allies a glimmer of hope that they could wind down their costly and much criticized war in Yemen without looking defeated in front of their publics.

Mr. Saleh indicated on Dec. 2 that he was formally breaking ties with the Iran-supported, Shiite Houthi rebels with whom he had most recently been allied, and instead was ready for dialogue with the Saudi-led coalition.

Saudi sources and analysts say the kingdom had been hoping the opportunistic Saleh perhaps would be able to broker an insider deal, ending the conflict in return for securing a position of power for him or his son.

The Saudis had entered the war in Yemen on behalf of Saleh’s successor, Abed Rabbo Mansour Hadi, aiming to thwart what they saw as aggressive meddling in a neighboring country by regional rival Iran. The long conflict had already transformed remote areas of impoverished Yemen into a breeding ground for Al Qaeda and, more recently, Islamic State (ISIS).

As the scope of the humanitarian disaster has worsened, however, the new Saudi leadership has been subjected to censure for what critics said was an adventurist foreign policy.

But the alleged execution of Saleh by Houthi fighters in Sanaa on Dec. 4 – two days after he indicated he was breaking ranks with the militia – dashed Saudi hopes of an exit strategy.

Pressing the attack

Rather than viewing the loss of its lone intermediary and potential key ally as a warning, however, the Saudi-led coalition appears to be using Saleh’s killing as an attempt to rally Yemenis across all groups and regions to “rise up” against the Houthis and drive them out of Sanaa.

Mr. Hadi, head of the internationally recognized government, called on forces loyal to him to “join hands to eradicate the terrorist Houthi militias and build a new, united Yemen,” while Saleh’s son, Ahmed Ali, vowed from the United Arab Emirates to “lead the battle until the last Houthi is thrown out of Yemen.”

Experts, meanwhile, say neither side of the conflict has the manpower or resources to tip the scales: Houthis will be unable to extend themselves beyond the territory they control in northern and central Yemen; and the Saudi-led coalition will be unable to turn the tide by missile strikes alone.

“Realistically what you have now is a really emboldened Houthi movement which think they have the upper hand in every sense, the Saudis unwilling to appear to lose, and you have lost one of the main interlocuters for talks,” says Peter Salisbury, senior consulting fellow at Chatham House, a Britain-based think-tank.

The cost of escalation would be staggering. Already 6 million civilians are on the brink of starvation and 11 million more are faced with a hunger crisis, while cholera has struck one million Yemenis, according to the United Nations.

Reports this week indicated that Saudi Arabia was tightening its blockade on the few fuel shipments allowed in from the Hodeida port, depriving millions of people access to cooking fuel, water pumps, and fuel for hospital generators.

Sectarian and radical shift

Experts warn that with the worsening of humanitarian conditions, and the Houthis’ loss of Saleh and his General People’s Congress as political allies, what was once an internal political conflict will become increasingly sectarian and dominated by extremist groups.

Operating alone as a Shiite Zaidi movement ruling over much of a majority Sunni country, the Houthis will play directly into the hands of groups trying to paint the war as a Sunni-Shiite conflict.

“Houthi consolidation of power in the north will most certainly extend the sectarian nature of the conflict in Yemen, and it will empower Al Qaeda and other groups that trade in sectarian rhetoric,” says Mr. Salisbury.

ISIS has already proved its potency in southern Yemen, targeting security forces, Emirati soldiers, and assassinating Salafi imams that preach a more moderate Islam.

With ISIS fighters fleeing Iraq, Syria, and parts of North Africa, there are concerns that thousands of fighters may retreat to Yemen to expand as a base to target Arab Gulf states, US interests, and Iran – three of the group’s major targets.

Experts also warn that increased fighting, missile strikes, famine, poverty, and lawlessness will drive thousands more Yemenis into the arms of Al Qaeda.

“There are a lot of angry, poor, starving people who have lost their jobs, who are out of school. It is a ripe environment for the recruitment of people that want to find a purpose in life,” says Noha Aboueldahab, a visiting fellow at the Brookings Doha Center. “I think unfortunately it is a great possibility Al Qaeda may increase its influence.”

Push for talks

The Trump administration surprised many on Wednesday by calling for the end of the Saudi-led blockade on Yemen. But calling an end to a disastrous blockade is one thing. Urging and facilitating all sides to sit down and discuss a political solution is another.

“People are less keen of talking about the political side of the process,” says Dr. Elisabeth Kendall, Yemen expert at the Pembroke College at Oxford University.

“We really need to think about the grassroots political processes that are required inside Yemen to start mending the fences, for if and when peace is finally made with the Houthis. This actually stands the chance of stopping the fighting on the ground.”

One tiny country is quietly leading the drive for peace talks in Yemen: Oman.

Traditionally known for its neutrality, non-interventionist foreign policy, and ties to both Iran and Saudi Arabia, Yemen’s neighbor emerged as a natural advocate for peace in Yemen.

Oman, which previously acted as a go-between between the US and Iran leading to the 2015 nuclear deal, has mediated a series of talks between the Hadi government and the Houthis to implement a peace plan championed by the UN, pushing for confidence-building measures such as turning over the Red Sea port of Hodeida to a neutral party, opening Sanaa airport for civilian traffic, and paying the salaries of civil servants.

Oman also reportedly arranged talks between US officials and Houthi representatives in the sultanate in 2016 during the Obama administration, but have failed to continue talks under the Trump administration.

Lacking international backing from major actors, Oman’s efforts to encourage parties to lay down their arms have often unraveled at the eleventh hour due to escalations from the Saudi-led coalition or from the Houthis themselves.

Experts say Oman needs the backing of international players – namely of the United States and Britain, Saudi Arabia’s closest allies and biggest arms suppliers, and of Iran – to bring the parties to abandon their drive to stubbornly continue a disastrous war to “save face.”

Points of Progress

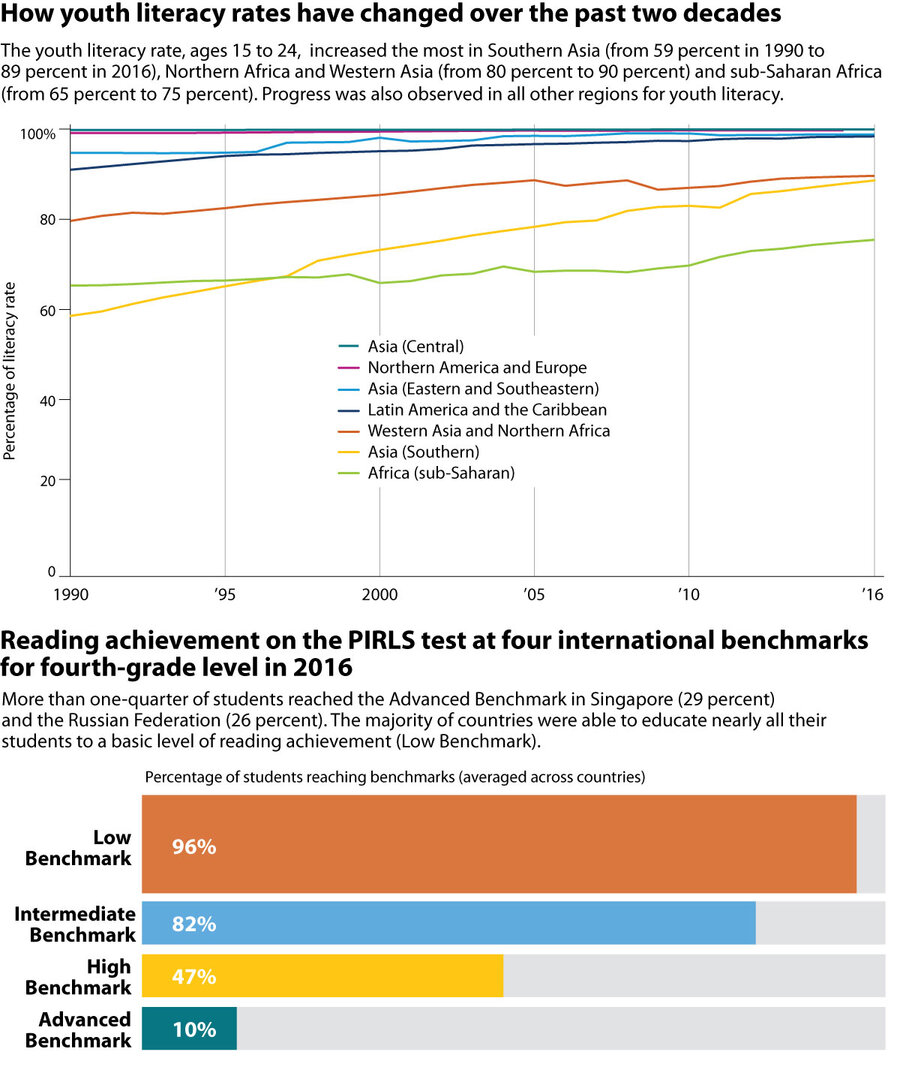

Behind a global rise in literacy

So many of the United Nations reports we’re sifting through these days outline the plight of different populations. A release on the eye-catching reading achievement among fourth-grade-age children in more than 60 educational systems – and everything that such success signals – was a welcome read.

Some good news for parents: One of the reasons literacy scores around the world are on the rise is that families are promoting reading at home from an early age. Qualified teachers help, too, as does three or more years of preschool. As newly released data from the Progress in International Reading Literacy Study (PIRLS) reveals, efforts to boost achievement are yielding results. For the first time since 2001, when the study began, 96 percent of fourth-graders from 60 educational systems across the globe are reaching the basic level for reading comprehension. Reported every five years, the study – conducted by the International Association for the Evaluation of Educational Achievement – saw countries such as Morocco and Oman make dramatic increases. Singapore and the Russian Federation, among other countries, saw average results increase by more than 40 points – with some countries decreasing as well. Girls outperformed boys, but adult women still lag in literacy overall. The United Nations tracks literacy gains for its sustainable development goals, with new data released this fall from UNESCO. In 2016, 750 million adults worldwide, two-thirds of them women, did not have basic reading and writing skills. Some 102 million people between the ages of 15 and 24 were illiterate. Still, the overall global literacy rate for adults was 86 percent, and the youth literacy rate 91 percent.

IEA's Progress in International Reading Literacy Study – PIRLS 2016, UNESCO Institute for Statistics, July 2017

Under threat: a plan for covering gaps in children’s health care

The prioritization of federal funding is anything but an abstract exercise to citizens who manage their own money tightly. “People work hard,” says a mother whose access to a critical health-care program was ended, to tragic effect, “but you never know what situation you’re going to fall into.”

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

-

Jessica Mendoza Staff writer

When Natasha Jacob’s husband lost his job in 2016, she was locked into a part-time teaching contract. They made too much to qualify for Medicare but private health insurance was not affordable. She enrolled her son in the Children’s Health Insurance Program. “It was absolutely crucial. I don’t know what we would have done,” she says. “I imagine we would’ve paid out-of-pocket for our son and we would’ve given up coverage for ourselves.” Unexpectedly, the popular bipartisan program’s future is at stake after Congress allowed funding to lapse in September. For the past two-plus months states have been funding the joint federal-state program out of their own pockets, but they are starting to run out of money. California is facing a $280 million shortfall. Texas, which has asked Congress for $90 million in emergency funding, is trying to find ways to avoid telling parents three days before Christmas that they will be losing insurance for their children.

Under threat: a plan for covering gaps in children’s health care

Dakota Flores sees a future for her children that she never had.

Tyler and Harmonie, both in middle school in San Antonio, Texas, are flourishing. Both are honor roll students, choir singers, and musicians. And they have a shot at going to college, something Ms. Flores was not able to do.

But Flores worries that future could be derailed by their chronic health conditions. Her children’s health insurance coverage, along with the coverage for an estimated 8.9 million other children around the country, could soon disappear after Congress allowed funding for the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) to lapse at the end of September.

For the past 2-1/2 months, states have been funding the joint federal-state program out of their own pockets, but they are starting to run out of money. Most of CHIP’s funding is federal, so if Congress doesn’t reauthorize funding by the end of the year, the program will start shuttering in early 2018.

Last week, Colorado became the first state to send letters to CHIP families warning them that support might end in January. Texas has asked the federal government for $90 million to keep its program running through February. If it doesn’t get confirmation by the end of this week that the additional funds are coming, the state says it will have to send similar letters to its more than 400,000 CHIP families, with the letters arriving days before Christmas.

For Flores, a single mother of four in San Antonio, the stress and anxiety have been mounting. Tyler has been diagnosed with attention deficit disorder so severe he could not sleep at one stage. Next week she will be meeting with doctors to get a last-minute check-up for Harmonie, who has a chronic eye condition, and to discuss coverage options should CHIP fold next year. If her prescription changes and she doesn’t have insurance, she says, “I’d have no idea where we’re going to go from there.”

“I’m just a bundle of nerves, because they’ve come so far,” says the mom, who now says she’s the one who has trouble sleeping. “The way I see it is they’re the next generation, and you’re stopping our next generation from succeeding.”

Bipartisan success

Health experts say CHIP has been an unmitigated – and bipartisan – success since Congress created it in 1997.

The program provides health insurance for children and pregnant women in households that earn too much to qualify for Medicaid, but not enough to afford private insurance, covering basic care from routine checkups and doctor visits to immunizations and prescriptions. The percentage of uninsured children nationwide dropped from 15 percent in 1997 to 4.5 percent in 2015, thanks in large part to CHIP.

Funding for the program needs to be reauthorized every few years, and in the past most Republicans and Democrats have been quick to agree to do so. The high-quality and affordable care it provides makes CHIP popular on the left, and the flexibility the program allows individual states makes it popular with conservatives.

When House Republicans introduced a bill to reauthorize the program earlier this year, however, it included provisions to pay for it in ways Democrats didn’t agree with, such as taking money from the Medicare and Affordable Care Act programs. The Senate Finance Committee passed a bill to reauthorize CHIP for five years, but doesn’t yet know how it would pay for it. Since then, both chambers have been consumed by efforts to repeal the Affordable Care Act and pass a tax bill, health policy experts say.

“It’s not necessarily an issue of do they think CHIP should exist or should be funded, but it is an issue of priority,” says Mimi Garcia, director of policy and external communications at the Texas Association of Community Health Centers. “Other issues just took precedence in Congress this year.”

That funding for CHIP would be used as political leverage the way it has this year is “unprecedented,” several health policy experts say.

“For advocates, you want to save the program, but you don’t want to at the detriment of another program,” says Sonya Vazquez, chief program officer at Community Health Councils in Los Angeles. “It’s just concerning for us. That you would have a certain portion of the legislature that would play that kind of a game with children’s lives.”

One mother's story

When Devante Johnson was growing up in Houston, his family nickname was “Hollywood.” He would make small figurines and models out of papier-mâché and sell them to his friends. His mother, Tamika Scott, thought he would grow up to be an entrepreneur.

That was more than a decade ago. As a 10 year-old Devante was diagnosed with cancer. He battled the disease for years with treatment covered by CHIP. His mother says things were progressing well until paperwork mishaps and changes in eligibility rules caused him to go four months without coverage in 2006. He died seven months later.

“We went through a long road,” says Ms. Scott. “My fight is to help other families not go through the turmoil I had to go through.”

“We should be embarrassed to even have to look at [this] on the news,” she adds. “Other countries are looking at us as we fight about whether we should give kids health insurance.”

So what is her advice to parents whose children could lose their CHIP coverage in the next few months?

“Go and demand assistance. Do not wait,” she says. “Don’t put your kids’ lives in someone else’s hands.”

State search for funding

States are now searching for creative ways to keep their CHIP programs afloat. Agencies in Texas, which is required by state law to shut down its program if federal funding stops, are considering a Medicaid-related “accounting trick” to dig up some temporary funds. Oregon is spending $35 million in state funds to keep its program running for the nearly 140,000 children and pregnant women who use it.

In California, where more than 2 million children and pregnant women are enrolled, CHIP funding is rolled into MediCal, the state’s version of Medicaid, which means children insured through the program are guaranteed coverage until 2019. But while that provision has allowed the state to hold off sending warning letters to families, officials worry about the estimated $280 million hole that the end of CHIP could blow in the state budget

Natasha Jacobs' son went on CHIP in early 2016 while she was locked into a part-time teaching contract and her husband was unemployed.

“It was absolutely crucial. I don’t know what we would have done,” she says. “I imagine we would’ve paid out-of-pocket for our son and we would’ve given up coverage for ourselves.”

“We’re not lazy,” Jacobs adds. “I just happened to be stuck in this contract where I couldn’t add more hours, and he just couldn’t find work.”

'People work hard'

Indeed, there appears to be a growing perception that CHIP recipients are mooching off of taxpayers.

Sen. Orrin Hatch (R) of Utah, who helped create the program with Democratic Sen. Edward Kennedy in 1997, said in a speech last week on the Senate floor that while it has done a “terrific job for people who really need the help,” he has “a rough time wanting to spend billions and billions and trillions of dollars to help people who won’t help themselves, won’t lift a finger, and expect the federal government to do everything.”

Scott says she herself had that perception. She had always been self-reliant, even working multiple jobs through high school, but when she was first applying for government assistance she had to make three trips to the local office before she could bring herself to fill out the forms.

“To go in there asking for help … it was difficult, but it was something I as a mother had to do,” she says. “Now when I talk to people I’m more compassionate, I can empathize with them… I can see myself in their situation.”

“Everybody is not just looking for a handout,” she adds. “People work hard, but you never know what situation you’re going to fall into.”

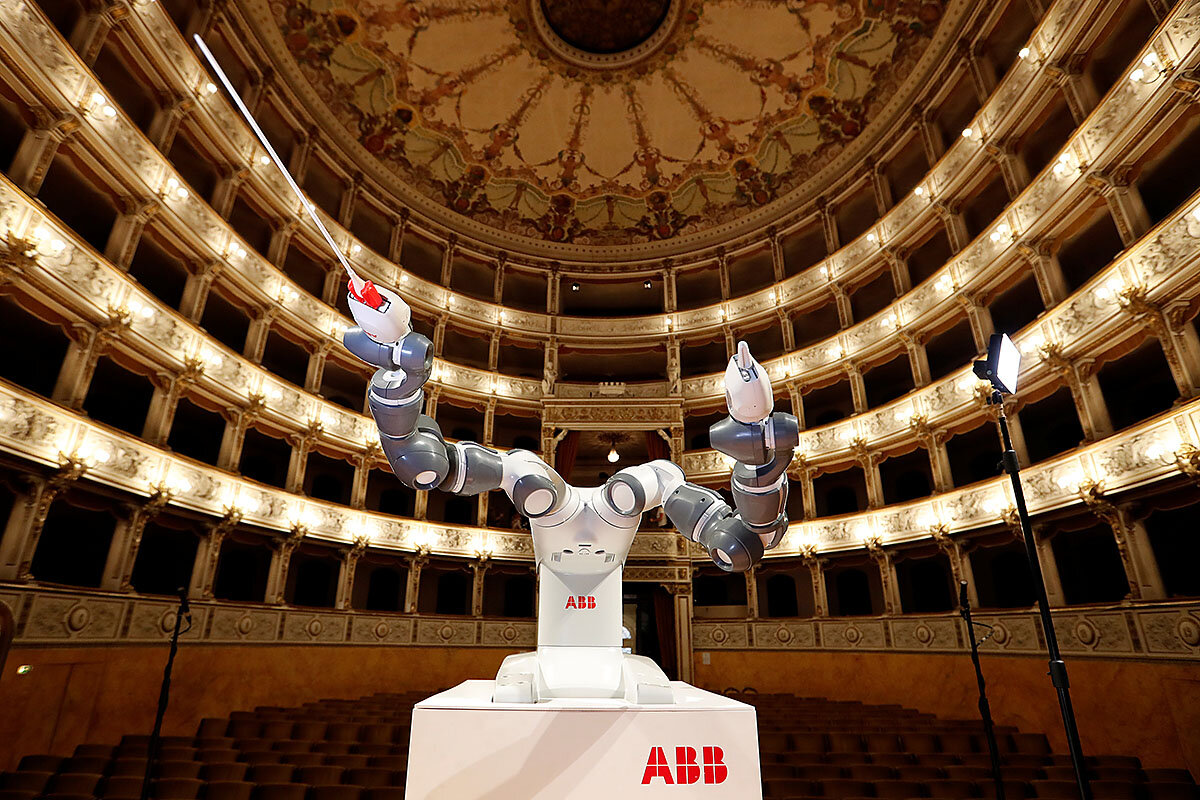

Rise of the machines: Are they coming next for the arts?

Here’s a talker for your weekend. Ultimately, intelligence can no more be contained by a circuit board than it can by a prefrontal cortex. What happens when its high-flying, flourish-making cousin, creativity, is attempted by robots?

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

Could a computer write a novel that is, well, novel? Rapid advancements in artificial intelligence have opened the door for machines to enter the world of the arts. In 2015, a computer-generated poem was accepted for publication in The Archive, a student-run literary journal at Duke University and one of the oldest literary magazines in the United States. In August, a program named Amper released “I AM AI,” the first music album composed and produced entirely by an artificial intelligence. But is that creativity? Is the birth of a song or a poem always art? Not necessarily. But the definition of art is both subjective and somewhat elastic. Just as Andy Warhol and Philip Glass have stretched the boundaries of what art can be, the rise of intelligent machines could expand the way we approach creative work.

Rise of the machines: Are they coming next for the arts?

Any novel idea can become an invention, but for a computer to truly be creative it has to innovate.

“Creativity consists of innovations,” says David Galenson, a University of Chicago economist who studies art markets and human creativity. “It changes the way people do things. The question is, will machines be capable of doing new things that are actually used?”

Professor Galenson says that creativity comes in two types: conceptual, which tends to be spontaneous, and experimental, which comes from years of practice. Orson Welles was only 25 when he directed his first feature film – “Citizen Kane,” now widely considered the best film ever made – but Alfred Hitchcock directed 68 films before finally achieving his magnum opus, “Vertigo,” at age 58.

Most AIs take the Hitchcockian approach to creative work. Because they can process information much faster than humans can, they can experiment with new combinations of data in a fraction of the time. This brute-force approach to creativity has already produced surprisingly human results.

Jack Hopkins, a former University of Cambridge researcher, has programmed a software that can be tuned to compose poetry in a specific rhythm with a specific theme. The system was trained on more than 7 million words of 20th-century English poetry, and some of its efforts have passed a Turing test – fooling readers into thinking they’re reading the words of a human.

His poetry bot is by no means the first to do that. In 2015, a computer-generated poem was accepted for publication in The Archive, a student-run literary journal at Duke University and one of the oldest literary magazines in the United States.

Meanwhile, website-building tools such as Firedrop and The Grid have employed AI assistants to simplify or even automate web design. In August, a program named Amper released “I AM AI,” the first music album composed and produced entirely by an artificial intelligence.

But conceptual innovation presents a deeper challenge.

Spontaneous bursts of creativity arise from the heuristic and sometimes nonsensical logic of the human thought. AIs are fundamentally data-driven. As a result, many of these programs provide “passable” solutions derived from common patterns, rather than entirely new creative works. Indeed, early adopters of AI-assisted design tools have complained of repetitive, “template-like” results. Amper’s debut single, “Break Free” is well-composed but ultimately forgettable.

While people can usually appreciate “goodness” on an intuitive level, a computer needs parameters to reach a conclusion. This poses a significant conceptual challenge to AI researchers: How does one articulate a nebulous concept like “good,” to a machine?

“Machine learning is good at generating and evaluating variations,” says Ranjitha Kumar, a computer science professor at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. “[But] you don’t really understand the problem definition, the constraints, or the criteria for goodness until you’ve built a bunch of things and tried them out. It’s hard to imagine an AI doing all that on its own anytime soon.”

But that future might not be so far off. In 2009, Canadian scientists developed a portrait-painting algorithm with an “automatic fitness function” to produce human-like artistic choices. Without prompting, the AI “rediscovered” certain techniques used by famous artists, such as using brush strokes to lead the viewer’s eye toward the eyes of the portrait’s subject.

“This is something that Rembrandt did but this was not ‘hand-coded’ into the computer program,” says co-author Liane Gabora, an assistant professor of psychology at the University of British Columbia-Okanagan. “It figured this out for itself.”

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Taiwan lets go a symbol of ancient days

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By The Monitor's Editorial Board

A new law in Taiwan calls for removing landmarks honoring former dictator Chiang Kai-shek. The law, coming 30 years after Taiwan moved toward democracy, shows how far a people will go to free themselves from a cultural legacy that may hinder progress in individual rights and equality before the law. The measure said that authoritarian rule should be “stripped of legitimacy.” Chiang’s harsh rule of Taiwan was based on Confucian-style autocracy, a belief that only a natural social hierarchy with a strong ruler can bring stability. Today, Taiwan is a thriving democracy. Most of its 23 million people now see themselves as Taiwanese, not Chinese. Taiwan’s move is a statement to the world that outdated ways of thinking can be let go. It sends a signal across the Taiwan Strait to China that real stability lies in honoring individual rights, not the presumed right of a few to rule.

Taiwan lets go a symbol of ancient days

On Dec. 6, lawmakers in Taiwan voted to rid the island of a prominent symbol of the country’s past. They approved a law requiring the removal of public statues honoring Chiang Kai-shek, a dictator who governed from the late 1940s until his death in 1975. In addition, Chiang’s name will be replaced on many schools and roads.

The law, coming 30 years after Taiwan moved toward democracy, shows how far a people will go to free themselves from a cultural legacy that may hinder progress in individual rights and equality before the law. The measure said that authoritarian rule should be “stripped of legitimacy.”

Chiang’s harsh rule of Taiwan was based on Confucian-style autocracy, or a belief that only a natural social hierarchy with a strong ruler can bring stability. That ancient tradition saw rights as granted only by the state and not inherent in everyone.

Today, Taiwan is a thriving democracy noted for its media freedom and lively politics. And unlike a previous generation that identified as Chinese, most of its 23 million people now see themselves as Taiwanese, defined in large part by their embrace of the values of democracy and freedom.

Chiang and his Nationalist Party fled to the island after losing China’s civil war to Mao Zedong’s Communists. He brought with him some 600,000 troops and more than 1 million loyalists from the mainland, hoping someday to retake China. Today most Taiwanese, including many descendants of the mainlanders, now happily proclaim the island’s independence – and not only as a separate country.

By contrast, in China, the ruling Communist Party has become more explicit in justifying its one-party rule as rooted in Confucian doctrines and the notion that the people are not sufficiently advanced in their thinking to pick their leaders. The party’s leading political theorist, Wang Huning, has said that Chinese political culture is pervaded by a reverence for authority. In October, he was elevated into the powerful Politburo Standing Committee and often travels with President Xi Jinping.

Taiwan’s very public act of removing landmarks commemorating Chiang is not only a symbolic shift for its people but a statement to the world that outdated ways of thinking can be let go. The move also sends a strong signal across the Taiwan Strait to China that real stability lies in honoring individual rights, not the presumed right of a few to rule.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

The power of spiritual unity

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By Lyle Young

Many countries and regions around the world are experiencing a need for greater unity. But it’s not inevitable that neighbor be divided against neighbor or group against group. Today’s contributor discusses the unifying power of a spiritual understanding of God as the one infinite and supreme Mind, whose active knowing is expressed through all creation and is entirely harmonious. On these grounds, divisive thinking can be seen as unnatural, lacking a true claim to power, because it is opposed to the infinite Love that is fundamental reality. Whatever our race, religion, or nationality, the desire to see and express harmony and unity is native to what we are as children of God. That desire helps us repel divisive thinking ourselves and replace it with thoughts and actions that are loving, peaceful, and brotherly.

The power of spiritual unity

Around the world many countries and regions are experiencing a need for unity – a need to overcome divisiveness, whether caused by polarized political positions, race, religion, or even referendums. But with all the channels of communication and information available to help us know other people better, why shouldn’t countries and, indeed, all humanity be feeling a sense of unity by now?

Mary Baker Eddy, the discoverer and founder of Christian Science, keenly observed human thought and understood the mental process by which neighbor comes to be divided against neighbor or group against group. She knew the Apostle Paul’s term the “carnal mind,” which he said is “enmity against God” (Romans 8:7), characterized by selfishness, hatred, and division. But in studying the Bible’s Old and New Testaments, she also found the inspired view that there is one infinite, supreme Mind, one God, whose conscious, active knowing and loving of its spiritual creation constitutes the true mental action of the universe, unchanged and unchanging.

And here she had a profound insight. Since God and His knowing are infinite, any thinking opposed to the infinite harmony expressed in God’s creation is not only wrong, it’s actually not real in an absolute metaphysical sense. This means that divisive thinking and action, while experienced on the human level and often tragically so, don’t exist in the Mind that is God.

A bold conclusion! But one that doesn’t lead to a Pollyannaish pooh-poohing of conflict and division as mere illusion. Rather, it leads to a moral imperative to confront divisive thinking as unacceptable, lacking a true claim to power, because it is opposed to the only legitimate source of authority – infinite Love.

This was the great lesson illustrated by the life of Christ Jesus, who prevailed against all that contradicted God’s law of harmony in his healing of sin and disease and overcoming death. He emphasized the importance of becoming like little children in order to receive the kingdom of God (see Mark 10:15). Should we be surprised to learn that the key tool in overcoming division is the purity and honesty of our own hearts? Whatever our race, religion, or nationality, the desire to see and express harmony and unity is native to all that we are as children of God, at one with Him and with each other.

That inherent desire for unity helps us repel divisive thinking and replace it with thoughts and actions that are loving, peaceful, and brotherly. Divisive thinking is not actually natural to us, but comes from the carnal mind, the counterfeit of the one divine Mind. We can watch our thoughts and accept as truly ours only those that have their origin in divine Love.

Listening for thoughts from God helps us bring clarity and, if necessary, correction to our own actions, political or otherwise. It inspires our prayers, helping us to see that everyone, including every political leader, is capable of making good decisions. It brings alertness and protection from those who would exploit divisiveness for popularity and short-term gain. It leads to calm that promotes more balanced, progressive, and inclusive civic engagement and public policy.

In truth, divine Love and spiritual unity constitute the only power, a power to which we can turn to bring healing to discordant situations and circumstances of all kinds.

A message of love

The best photo books of 2017

A look ahead

Thanks, as always, for being here. For Monday we’re digging into the nuances of the Palestinian reaction, both among leadership and on the street, to the US administration’s formal recognition this week of Jerusalem as Israel’s capital.