- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Monitor Daily Intro for December 13, 2017

Today was a big news day – and we’ll dig into the Alabama Senate race and hearings before the House Judiciary Committee in just a minute.

But first, here's a different issue that is confounding cities and towns across the world.

We all know we’re texting a lot. But we’re increasingly texting and walking – into another person, into fountains, into traffic. The results range from rudeness to embarrassment to life-threatening encounters. The battle is now engaged against the world’s “smartphone zombies.”

Come Monday in Tokyo, for example, three companies will test a messaging system on the subway that connects pregnant women hoping to snag a seat with people happy to offer one but oblivious to everything but their devices.

In Honolulu, pedestrians who screen-gaze while crossing the street will pay up to $99 if caught. A bill in Boston would boost jaywalking fines if mobile devices and headphones are involved. Seoul, South Korea, the world’s most connected city, has experimented with warning signs embedded in the pavement. (Few have noticed them.) A town outside Amsterdam has laid down LED strips whose color changes in sync with traffic signals.

Some say the root problem is a society where work and leisure blur, where expectations drive constant attention to smartphones. For now, the best step may be a simple New Year’s resolution: Just look up.

Now to those other stories I mentioned – including ones that examine how policy changes can drive behavioral changes in everything from education to savings.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

What Doug Jones’s win means for Democrats

In the wake of Alabama's deeply contentious election, signals may be growing of voter interest in candidates who don't have sharp elbows.

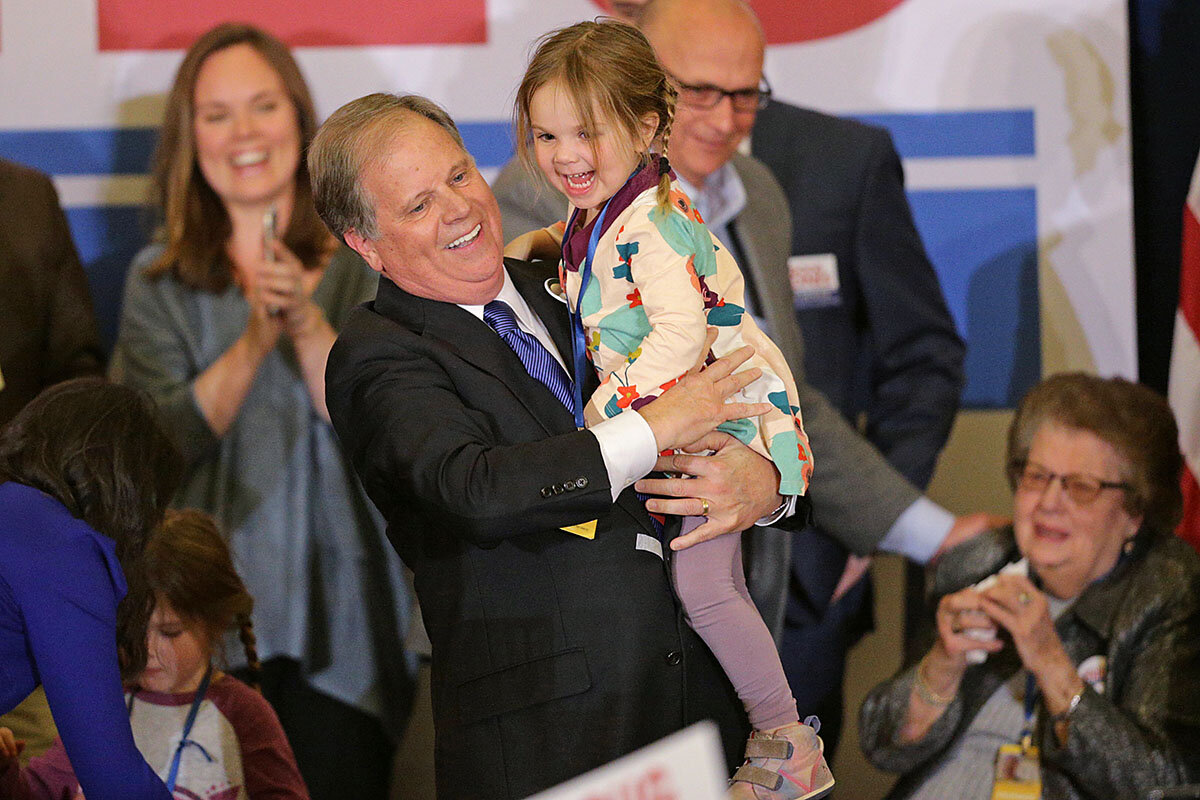

The Alabama Senate race, to most Americans, was almost entirely about Roy Moore. But now the focus shifts to Democrat Doug Jones, who pulled out a narrow win Tuesday in a deeply red state. Democrats are buoyed by his victory, seeing a potential path to retaking control of the Senate next year. And they are hopeful they can move Republicans to a more moderate agenda, given that the GOP will be down to a single-seat majority when Mr. Jones takes office in January. “It means that things are looking good for us,” said Sen. Charles Schumer, the Democratic minority leader, speaking of the election outcome Wednesday morning. But this outlook also comes with caveats. The race in Alabama had a singular quality to it, defined by a seriously flawed candidate. And Jones, if he wants to stay in office beyond 2020, when he would next be up for reelection, will have to please his conservative constituents. Indeed, Jones campaigned as a political bridge-builder, saying he hoped to work with Republicans and President Trump.

What Doug Jones’s win means for Democrats

Doug Jones, the Democratic lawyer who snatched a historic Senate win in Alabama on Tuesday, is a man of high ideals.

In 1977, when he was still in law school, the young Alabamian skipped contracts class with a friend to watch then-Alabama Attorney General Bill Baxley prosecute the first trial of the 1963 bombing of the 16th St. Baptist Church in Birmingham. The dynamite blast killed four African-American girls, a seminal event in the turbulent civil rights era.

Mr. Baxley faced a defense lawyer who was the son of a Birmingham city mayor – two titans going at it. “Baxley was masterful,” recalls Mr. Jones’s friend, Richard Mauk. “We were so impressed with that, and Doug was like, ‘That’s who I want to be, fighting for truth and justice.’ ”

Jones eventually fulfilled that dream as a US attorney in Alabama, reopening the Birmingham case and convicting Klansmen responsible for the bombing.

Now he’s about to live out another dream as the state’s next US senator – a goal with roots in a stint after law school as staff counsel to former Alabama Sen. Howell Heflin (D). Jones calls the late Senator Heflin “a gracious gentleman of impeccable character” who remains his role model today.

Since allegations of sexual harassment against Republican Roy Moore surfaced in November, the Alabama Senate race, to most Americans, has been almost entirely about Judge Moore – the renegade justice twice removed from the state Supreme Court for not following federal rulings.

But now the focus shifts to Jones, the lesser-known victor who pulled out a narrow win in a deeply red state. Democrats are buoyed by his victory, seeing a potential path to retaking control of the Senate next year. And they are hopeful they can move Republicans to a more moderate agenda, given that the GOP will be down to a single-seat majority when Jones takes office in January.

“It means that things are looking good for us,” said a happy Sen. Charles Schumer, the Democratic minority leader in the Senate, speaking of the election outcome Wednesday morning. The New Yorker sees in Alabama “seeds” of the Democrats’ strong showing in Virginia’s statewide elections last month, when their energized base, Millennials, and suburban voters – particularly women – handed them the governorship and significant gains in the state legislature.

But this outlook also comes with caveats. The race in Alabama had a singular quality to it, defined by a seriously flawed candidate. And Jones, if he wants to stay in office beyond 2020, when he would next be up for reelection, will have to please his conservative constituents. Indeed, Jones campaigned as a political bridge-builder, saying he hoped to work with Republicans and President Trump. On Wednesday, the president called Jones to congratulate him and invited him to the White House.

“Jones is probably not going to be the most reliable Democratic vote on a lot of things, and Schumer is going to have to give him a pass on some things,” says Jennifer Duffy, a close watcher of the Senate at the independent Cook Political Report.

Flipping control 'mathematically possible'

Nevertheless, analysts such as Ms. Duffy now see a Democratic takeover of the Senate as a possibility in the 2018 midterms – albeit a slim one.

Democrats would have to hold all of their seats and take two more if they want to crack the tie-breaking advantage of Vice President Mike Pence. The map works against them: Ten Democrats are facing reelection next year in states that Mr. Trump won. Republicans look vulnerable in just three states: Arizona, Nevada, and Tennessee.

“It’s mathematically possible to put the majority in play,” says Duffy, adding: “I’m not saying they’re going to win.”

Jones, however, could provide a model on how to win in a red state.

He kept a disciplined focus on “kitchen-table” issues: health care, education, jobs, while blasting Moore as an “embarrassment” to Alabama. He also campaigned hard – on a recent Sunday, visiting nine black churches in one morning – and flooded the airwaves with ads, having vastly outraised his opponent.

And he stuck to his message as someone who came from a working-class family and will seek common ground – including with Trump – for more productive politics. That he is bland as sand made no difference – and in fact, may have proved an advantage among voters wearying of flame-throwing candidates and looking for a steadier hand.

“At the end of the day, this entire race has been about dignity and respect,” Jones told an ebullient victory crowd in Birmingham Tuesday night. “We’ve tried to make sure that this campaign was about finding common ground and reaching across and actually getting things done for the people.”

Whether that will actually happen as a result of having an Alabama Democrat in the Senate – for the first time in a quarter century – is hard to foresee. Senator Schumer called on Republicans Wednesday to hit “pause” on tax reform, wait for the seating of the senator-elect, and rework the plan in a bipartisan manner.

Full speed ahead

That call was a whistle in the wind. Republicans are rushing to move their tax cuts to a final vote next week, announcing on Wednesday an agreement in principle between their House and Senate versions. Schumer said the plan, unpopular in public opinion polls, will “clobber” suburban voters because it does not retain full state and local taxes as a deduction.

The tax plan will come back to bite Republicans in the midterms, Schumer predicted. So could other issues, such as health care, internet access, and Trump himself.

Looking ahead, the White House has indicated that next it wants to tackle infrastructure – traditionally a bipartisan issue. But it all depends on the details. Jones would be unlikely to support it if it meant cutting social safety net programs such as Medicare, Medicaid, and Social Security – as Hill Republicans are now signaling. That would not go down well in a state with one of the highest poverty rates in the country.

In the mold of red-state Democrats such as Sen. Heidi Heitkamp of North Dakota or Sen. Joe Manchin of West Virginia, Jones might join Republicans from time to time on legislation specifically beneficial to his state. But neither of those two supported conservative goals like repealing the Affordable Care Act, or a tax cut plan that heavily favors corporations and the wealthy.

“He would be like Joe Manchin,” says Wayne Flynt, professor emeritus of history at Alabama's Auburn University. In practice, that might mean working to fix Obamacare, not do away with it.

As with anything bipartisan, it takes two to tango. Mark Meadows (R) of North Carolina, chairman of the House Freedom Caucus, told reporters Wednesday that conservatives such as himself will not be tacking to the center.

“We’ve been legislating to the middle for two decades, and that hasn’t gotten us too far,” he said, cautioning that “you can’t draw any conclusion from one race in Alabama.”

Still, that’s what pundits and politicians do best, and the elections in Virginia and Alabama at least hint at the possibility of more Democratic inroads in the South. On the flip side, there may be some Republican inroads coming in the north – for instance, if a Republican were to win resigning Democratic Sen. Al Franken’s seat in Minnesota in 2018.

Perhaps, says Duffy, “but the parties would have to tolerate it.” They would have to accept more moderates in their midst.

Correction: After Doug Jones's win, Democrats need two additional Senate seats to take the majority.

Share this article

Link copied.

Investigating the investigators: What happens when facts are politicized?

When political investigations become exercises in mutual distrust, they eat away further at trust in government.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

The Republican congressman was blunt. The members of special counsel Robert Mueller’s team investigating Russian meddling in the presidential election might as well wear uniforms, he said. Democratic uniforms: donkeys, or maybe shirts saying, “I’m with Hillary.” Speaking at a Wednesday House Judiciary Committee hearing, Rep. Steve Chabot from Ohio expressed a sentiment increasingly heard among Republicans on Capitol Hill: The Mueller probe is biased, and should be investigated by a second special counsel. These members point to text messages between former members of Mr. Mueller’s team that expressed anti-Trump feelings prior to the election. But Democrats and other critics point out Mueller is a registered Republican appointed by a Republican deputy attorney general who was appointed by President Trump. Furthermore, reducing Justice Department attorneys, or any government worker, to a “D” or an “R” denigrates their professional ability. Should FBI Director Christopher Wray investigate only Republicans, since he’s a member of the GOP who donated to GOP candidates? The White House and allies are trying to distract from Mueller’s indictments and recruitment of former national security adviser Michael Flynn as a government witness, critics say. It’s part of a larger effort to depict the FBI and the Justice Department as “corrupt” and “useless” – in “tatters,” as Mr. Trump has tweeted. “It’s that constant degradation of major American institutions that play an incredibly important role in the legitimacy of the government that is really frightening,” says Jennifer Victor, a political scientist at George Mason University.

Investigating the investigators: What happens when facts are politicized?

Taking their cue from President Trump, some congressional Republicans are intensifying charges that special counsel Robert Mueller’s investigation into the 2016 presidential election is suspect because it is laced with pro-Democratic political bias.

On Wednesday GOP lawmakers at a House Judiciary Committee hearing hammered Deputy Attorney General Rod Rosenstein on this issue. They cited text messages between two former Mueller team members that expressed deep anti-Trump sentiment prior to last November’s vote.

At one point Rep. Steve Chabot (R) of Ohio suggested that investigators on the Russia probe might as well wear uniforms. “The Mueller team overwhelming ought to be attired with Democratic donkeys or ‘I’m with Hillary’ [shirts], certainly not ‘Make America Great Again,’ ” Representative Chabot said.

Democrats and other critics say this charge is essentially diversionary. It’s meant to distract from Mueller’s indictments and the flipping of former National Security Advisor Michael Flynn into a witness for the prosecution, they say, and reduce the impact of any further developments from the Russia investigation.

Furthermore, Justice Department lawyers – indeed, all government workers – are more than an “R” or a “D”, say critics. To strip them down to a partisan identity is overly reductive and unworkable. FBI Director Christopher Wray is a Republican who has donated lots of money to GOP candidates. Does that mean he can only investigate suspects from his own party?

If the Trump White House and its allies are using this approach to make it possible to fire Mueller, they are playing a dangerous game, says Ryan Goodman, a professor at the New York University School of Law and national security legal expert.

“Especially with all the national security threats and other top priorities in foreign policy we are facing, it would throw the country into turmoil,” he says.

The belief among some in the GOP that the Mueller probe is out to get Mr. Trump was on full display Wednesday at the House Judiciary grilling of Mr. Rosenstein. Republican after Republican cited text messages released on Tuesday between a top counterintelligence agent, Peter Strzok, and another senior FBI lawyer named Lisa Page.

“This man cannot be president,” wrote Ms. Page at one point, referring to Mr. Trump.

“Maybe you’re meant to stay where you are because you’re meant to protect the country from that menace,” Page also wrote.

“I can protect our country at many levels, not sure that helps,” Mr. Strzok replied.

Strzok was one of Mueller’s top investigators, until Mueller last summer became aware of the texts, and transferred him to another FBI post. Page worked briefly for Mueller’s team but is no longer employed there.

At the Judiciary Committee on Wednesday some GOP members insisted that it is time for another special counsel to investigate the current special counsel’s possible political conflicts of interest.

“The country thinks we need a second special counsel,” said Rep. Jim Jordon (R) of Ohio.

Trump’s personal lawyer, Jay Sekulow, this week has also called for the naming of a second special counsel. Mr. Sekulow cited a different reason: a Fox News report that a senior Justice Department official named Bruce Ohr was demoted for not revealing meetings with officials of Fusion GPS, the investigative research company that produced the so-called “dossier” of opposition intelligence on the 2016 Trump campaign.

Rosenstein on Wednesday deflected the issue of another special counsel by pointing out that the Justice Department Inspector General is already looking into these matters. Others pointed out that special counsels are generally reserved for criminal, not civil, investigations.

In any case, it is untrue that the country wants a second investigation, says William Galston, a senior fellow in governance studies at the Brookings Institution. Mueller is doing well in the court of public opinion, Mr. Galston says, with poll ratings generally reflecting 60 percent or so support of his efforts.

“I haven’t seen any evidence that the American people have turned against him or his investigation,” says Galston.

Surveys taken by the legal security blog Lawfare have generally shown that Mueller’s ratings go up following action, such as an indictment. On Wednesday the blog published results of a poll that measured respondents' confidence in the FBI on a scale of 1 to 5, with 5 being the highest. The average score was 3.34, which compares favorably to all other institutions, with the exception of the military, which rates at 3.7.

“Support for the Bureau appears very strong,” according to Lawfare’s Mieke Eoyang, Ben Freeman, and Benjamin Wittes. “If he’s going to defend himself by tearing down the FBI, Trump has his work cut out for him.”

View of investigation depends on party

However, like so many issues in today’s politically polarized America, this overall judgment of support needs to be accompanied by a caveat. Republicans and Democrats are so split as to be almost in different worlds on this issue.

According to a Pew Research Center poll released in early December, only 44 percent of Republican and Republican leaning respondents are at least somewhat confident that Mueller will conduct a fair investigation into Russia’s involvement in the 2016 election. The corresponding figure for Democrats is 68 percent.

Nineteen percent of Republicans view the Mueller effort as “very important.” Seventy-one percent of Democrats feel that way.

The implication of this split is that the results of Mueller’s investigation, whatever they are, are unlikely to unify the country.

“In this hyperpolarized situation it would be astonishing if Mueller’s report didn’t generate a storm of controversy. Of course it will,” says Galston.

Thus Democrats who think that it is possible some explosive Mueller finding will close the case, and convince Republicans that Trump is unfit for office, are probably mistaken. There will not be a big news story that reveals “inexcusable collusion” such that there is a national consensus about serious consequences, says Jennifer Victor, an associate professor of political science at George Mason University in Fairfax, Va.

“Partisanship is now the sort of primary decisionmaking mechanism people are using to decide whether things are good or bad,” Dr. Victor says.

The reasons for this may be many and varied. The parties have become more ideological since conservative southern Democrats began migrating to the GOP in the 1970s. The rise of Fox News and other conservative media has sparked an ideological response with MSNBC. That is exacerbated by social media feeds. Increasingly partisans can live in a bubble where their beliefs are not only unchallenged, they are assumed to be the nation’s normal benchmark.

When president says FBI's standing is 'worst in history'

In years past, the president of the United States saying that the FBI’s standing was the “worst in history,” as Trump tweeted earlier this month, might have caused a national crisis, says Victor, especially when combined with a White House surrogate and former Speaker of the House, Newt Gingrich, saying the Justice Department has “become corrupted.”

“It’s that constant degradation of major American institutions that play an incredibly important role in the legitimacy of the government that is really frightening,” Victor says.

The irony is that Mueller may represent the president’s best chance to clear the Russia clouds from over the White House, says Goodman of New York University.

Conservatives should embrace Mueller, not criticize him, he says, since if Trump did nothing wrong that’s what Mueller will say.

“So many conservatives believe that Trump is innocent of any criminal activity, either because he didn’t do anything wrong or because certain acts are not criminal. If they are correct the best chance that the president has to clear himself is to allow Mueller to do it for him,” Goodman says.

In Zimbabwe, women must confront a legacy of Grace Mugabe

Zimbabwe's former first lady dismayed many of her fellow citizens with her aggressive grab for political power. That has complicated the quest of legitimate women politicians to be judged not by their gender but by their work.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

-

Wendy Muperi Contributor

When Robert Mugabe resigned last month, after 37 years in power, celebrations broke out across Zimbabwe. But many were just as happy to see his wife, Grace, tumble from power – a woman whose reputation for corruption and high spending, and whose own political ambitions, seemed to make her some Zimbabweans’ Enemy No. 1. “We don’t want prostitutes in politics,” some protesters chanted in the days before her husband’s resignation. “Leadership is not sexually transmitted,” signs read. On the face of it, women play a relatively prominent role in Zimbabwean politics, filling one-third of the seats in Parliament – better than the ratio in the United States, Canada, or Germany. But the deep misogyny of the insults lobbed at Ms. Mugabe is all too familiar for female politicians with more traditional résumés, as well. “No one would ever say that about men, if one of them can’t lead you should never try another,” says one human rights activist who is running for Parliament. “But somehow with women, that’s what we are being told.”

In Zimbabwe, women must confront a legacy of Grace Mugabe

During his 37 years as Zimbabwe’s prime minister and president, Robert Mugabe ordered the massacre of thousands of political opponents, ran the country’s economy into the ground, and instilled a culture of political violence and paranoia that will likely long outlast him.

But what ultimately brought down Zimbabwe’s first post-independence leader was something far smaller and more personal than any of that.

His wife, Grace.

“Robert Gabriel Mugabe’s legacy, though it was being chipped at in the end, was not being tainted by his own hand,” declared the state-owned Herald newspaper the day after Mr. Mugabe’s resignation. “But much like Adam and Samson before him, the blame falls on his partner.”

Few citizens pitied her – acerbic and nepotistic – as she tumbled from power. But for many women in Zimbabwean politics, the string of sexist insults that followed Ms. Mugabe down seemed to carry a wider warning.

Protesters calling for President Mugabe’s resignation had chanted “We don’t want prostitutes in politics” and carried signs that read “leadership is not sexually transmitted.” When Grace and her husband were put under house arrest during the military coup, the generals allegedly ordered the first lady to “stay in the kitchen.”

Ms. Mugabe’s original sin was that she wanted to be president. For three years before her husband’s ouster she had thrashed aggressively toward that goal, vaulting unspoken hierarchies of age, experience, and gender. But the sexist tone of criticism against her is all too familiar for female politicians with more traditional résumés, as well.

“The pushback against Grace is really a pushback against women in our public affairs,” says Sakhile Sifelani-Ngoma, executive director of the Women in Politics Support Unit (WiPSU), a non-governmental organization. “There is a deep level of misogyny that permeates politics in Zimbabwe.”

Tarred with Grace's brush

And it does run deep. “We discovered with [Grace] that women have got a lack of mind,” says Darlington Tsikada, who works in a copy shop in Harare. “After that I don’t think a woman can be a leader in this country.”

Mr. Tsikada is a man. But his viewpoint spans gender. “Women are selfish, the way we think is self-centered,” argues Vimbisai Matamba, a woman who sells vegetables in downtown Harare. “We cannot have a woman for president.”

Ms. Mugabe’s failure “set a bad precedent for women leaders,” says Margaret Dongo, a former member of Parliament for the ruling ZANU PF party who became a sharp critic of the government. Grace Mugabe “has given men a platform to challenge women’s leadership,” she worries. “Now they can say every woman is like that.”

“It’s really insane,” says Linda Masarira, an independent candidate for Parliament in Harare and a long-time human rights activist and trade unionist. “No one would ever say about men, if one of them can’t lead you should never try another, but somehow with women, that’s what we are being told.”

On the face of it, women play a relatively prominent role in Zimbabwean politics, filling one third of the seats in Parliament – better than the ratio in the US, Canada, or Germany.

“Zimbabwe has had good policies on gender over the years – but women in our politics are still tokenized,” says Ms. Masarira.

“There are challenges coming from both society and other members of Parliament around equality,” says Beater Nyamupinga, the former chair of the women’s legislative caucus and a ZANU PF MP since 2008.

There were the fliers tacked on walls around her neighborhood during campaign season, for example, questioning her moral character and asking where her husband was (as a diplomat, he was frequently out of the country).

Then there is the way male legislators talk to and about women, she says. During one debate, she remembers, male legislators repeatedly referred to sex workers as “whores.”

“We had to remind them that that’s not acceptable,” she says.

Sauce for the goose?

Legislators like Ms. Nyamupinga say they must maneuver carefully to avoid criticism that women aren’t fit to lead. She doesn’t campaign in bars – a popular way for many of her male colleagues to drum up youth support – because it wouldn’t be proper for a woman, and she is careful to avoid criticizing local leaders or customs when she comments on gender equity.

Grace Mugabe, on the other hand, followed none of those rules.

Mugabe’s former mistress, who met the president while his first wife was on her deathbed, Ms. Mugabe has long been a divisive figure, known for lavish international shopping trips and strange bursts of violence.

Her political style was petty and personal, which is not unusual in Zimbabwe, but which drew special criticism coming from her.

“There’s a bit of respect we expect from women to men, especially older men. She didn’t really do it,” says Levison Muzengi, an accountant in Harare. “If men are talking to men you expect some of that kind of vulgar language, but if a woman is now challenging a man with it, it becomes something else.”

“Almost all our politicians say ridiculous things,” says Chipo Dendere, a Zimbabwean political scientist at Amherst College in Massachusetts. “And yet with the men, it’s somehow acceptable.”

Though Robert and Grace Mugabe are out of the political picture, the debate about women’s role in politics is now being played out through the new president, Emmerson Mnangagwa and his wife Auxillia Mnangagwa.

The fact that she is a member of Parliament in her own right did not stop a bishop officiating at President Mnangagwa’s inauguration from praying that Auxillia would take on a “motherly role.”

“There were suddenly lots of comments about the first lady and how she should step down from her role in politics,” says Ms. Sifelani-Ngoma. “It’s blowback against Grace, absolutely, and it’s unfair and discriminatory.”

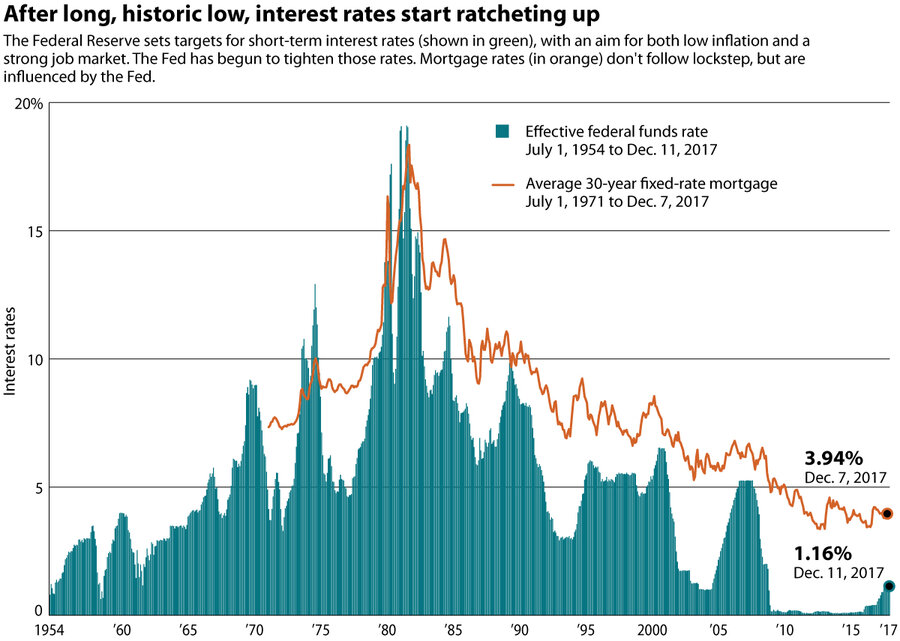

Americans face a forgotten foe: rising interest rates

Higher interest rates can hurt those with credit card debt or aspirations to enter the housing market. But they could also prompt a return to a desirable behavior: setting aside savings.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

-

Laurent Belsie Staff writer

The Federal Reserve raised its short-term interest rate for banks today, marking an increase of about a full percentage point over the past year. That's the fastest bump up in interest rates since 2006, with more hikes expected. So what does that mean, coming at a time when many Americans can barely recall meaningful rises in borrowing costs? For now the impact on pocketbooks and behavior may be muted. Stock investors and consumers appear confident. But in 2017 alone, rising interest rates cost credit card borrowers an extra $6 billion. And mortgage and auto-loan rates have also gone up somewhat since 2015. Savers may soon find money market accounts that finally can beat inflation. The cautionary note: Periods of Fed rate hikes are often followed by recessions, although economists don’t expect one next year. “I see no signs that consumers will rein in spending anytime soon,” says analyst Jill Gonzalez at WalletHub.

Americans face a forgotten foe: rising interest rates

Like a small cloud on a sunny beach, a quarter-point hike in short-term borrowing rates arrived over the economy Wednesday.

The beachgoers are unlikely to notice. The Federal Reserve has already jacked up rates and the pace of economic growth has risen not fallen. The stock and housing markets are doing splendidly. Consumer confidence is at a post-2000 high and rising.

The interest-rate horizon has been sunny for so long – nearly a decade, in fact – that Americans may have forgotten what happens when interest rates rise. But with more rate hikes predicted for next year after a full percentage point rise since last December – the fastest jump since 2006 – it’s time for consumers and investors to adjust their thinking to a new reality.

Among the likely impacts of the new period:

- Credit-card rates will rise, at a time when credit-card debt has rebounded from the Great Recession to reach record levels again and some borrowers are already showing signs of stress.

- Some holders of student debt, those who took variable-rate loans as well as students taking out new loans, will take a hit.

- Rates on auto loans and even mortgages are predicted to go up, albeit more slowly than more short-term debt. Auto loan delinquencies are on the rise.

- Savings or money-market accounts may finally start offering interest rates that come close to matching inflation. But the stock market could grow more volatile.

What’s needed in this period or rising rates is not panic but prudence, economists and consumer-finance experts say.

“Consumers and investors both have the first instinct of protecting and maximizing their assets,” Jill Gonzalez, an analyst at consumer-finance website WalletHub, writes in an email. “This means that if interest rates go up, consumers will increase their savings since they can receive higher rates of return, and investors will be more inclined towards maintaining a diversified portfolio to counteract the volatility over time."

Of course, interest rates have stayed so low for so long that even economists are unsure what impact the expected rate-rise will have. Borrowing costs will still be lower than historic norms. The best guess is that impacts will be muted – for both consumers and investors. The temptation to move from stocks to fixed income will be there for some, yet yields will still be nothing to write home about.

Rate hikes and recessions

But finance experts also caution against complacency. A period of Fed tightening is not just about interest rates. It’s also about how well the central bank can do at regulating the economy’s monetary spigot. Economist Gary Shilling offers a blunt outlook in a new report.

“If the Fed persists in tightening, a recession is in the cards. By our count, in 11 of 12 post-World War II attempts by the central bank to cool the economy without upsetting the apple cart, a recession resulted. The only soft landing was in the mid-1990s,” Mr. Shilling writes.

For now, economists don’t see recession as a meaningful threat for next year. But some see the risk rising in 2019 if the Fed keeps tightening as expected.

All this can create uncertainty in the stock market. It’s also a reminder that the Fed’s steering of short-term rates doesn’t necessarily determine longer-term rates like those on mortgages or Treasury bonds. Marketplace forces are key. If bond-market investors are worried about a cooling economy, long-term interest rates can go down (or go up less) even when the Fed is raising interest rates.

“On average, a one percentage point rise in the [Fed’s short-term lending rate] leads to a 0.42% rise in 10-year Treasury yields,” Shilling explains.

Home buyers may face an uptick in mortgage rates, but economists note that over the past year the borrowing costs on a fixed-rate mortgage have edged down even as short-term rates have risen.

Nevertheless, if prospective buyers see an upward trend in mortgage rates, that could push some into action to purchase a home before rates go higher still, says Chris Christopher, executive director of US and global economics at IHS Markit near Boston.

Others could be priced out of the housing market entirely, he adds, in areas like New York City or San Francisco where prices are very high.

A credit-card hit

One of the first places consumers will see the impact of rising rates is on their credit card statements. Since December 2015, the Fed has driven rates up a full percentage point from near zero (not counting Wednesday’s increase) and credit card rates have moved up in lockstep, according to a WalletHub report released this week.

WalletHub estimates that those hikes cost consumers an extra $6 billion in credit-card interest this year. Wednesday’s increase will boost consumer costs another $1.46 billion in 2018, it says.

By contrast, interest rates on savings accounts and certificates of deposit have barely nudged up at all since the Fed began raising rates.

“If interest rates go up, people will come out of stocks and go into fixed-income investments,” says Shawn Lesser, co-founder of Big Path Capital, a socially oriented investment bank. But the interest rate “is so low that even if it moves up 1 percent, I don’t know how much of an impact it would have.”

The Fed has had interest rates very low before. The effective federal funds rate (which is the actual rates banks pay each other on overnight loans) dipped below 1 percent for three months in 1954 and again in 1958. It didn’t fall that low again until 2003 for one month. But in 2008, in a bid to stave off the financial crisis, the Fed slashed it below 1 percent, where it remained for 8-½ years.

Only in May have they edged above 1 percent. And the consensus among forecasters surveyed by the National Association for Business Economics is that interest rates will be near 2 percent by the end of 2018. That’s still low by historical standards, where the average over six decades is 4.9 percent.

Troubling signals

There are already signs of strain. Although foreclosures have receded, delinquency rates among auto finance lenders are rising, especially for subprime borrowers, the Federal Reserve Bank of New York warned in a November report. Credit card delinquencies are up over the past year. College-loan troubles have been mounting along with the debt itself.

When CompareCards.com surveyed 1,000 adults about why they had accumulated credit-card debt, 42 percent said "making ends meet."

At some point, interest rates could get so high that consumers would have to change their spending habits.

“There certainly should be a tipping point,” writes Ms. Gonzalez of WalletHub. At the start of the Great Recession “in 2007, that was about $8,400 of credit card debt per household, which we're almost back to hitting again. However, since unemployment is at a 17-year low and consumer confidence is high, I see no signs that consumers will rein in spending any time soon."

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve Systems (US), Freddie Mac

A California county moves to lift more Latinos into college

It can be tempting to stick with long-standing approaches in education. But in a demographically changing America, progress comes in being willing to adapt, instead of assuming that what's already there still works.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

In California’s Riverside County, a change in educational approach is under way. Since 2014 the county has expanded student access to college counselors, improved parent engagement and bilingual services, and helped students fill out the Free Application for Federal Student Aid. As a result, graduation rates, college enrollment, and FAFSA completion rates are up across the county. It’s a strategy that education advocates say could serve as a model for chipping away at a broader issue: improving outcomes for California’s Latino students, who, despite making up the majority of the state’s student population, still face some of the greatest barriers to college enrollment and completion for any demographic, according to a new report. “We often ask [students and families] to navigate a system not designed for them, instead of meeting students where they’re at,” says Ryan Smith, director of Education Trust–West, the nonprofit behind the report. “We haven’t faced the reality that this state will succeed or not succeed by the way it treats its Latino students.”

A California county moves to lift more Latinos into college

High school senior Raymond Franco made three mistakes on his college application.

They were little things, like putting “2017” instead of “2018” as his graduation year. They probably wouldn’t have made a dent in his chances at getting into his schools of choice – the 17-year-old takes three advanced placement classes and trains with three different sports teams.

Then again, Mr. Franco says, maybe they would have. “If you mess up on one thing, it can mess up your whole application,” he says.

Which is why he was thankful that Rancho Verde High School devoted several class periods this fall to helping students fill out college and financial aid applications. Faculty and counselors were present to answer questions, explain requirements, and – as in Franco’s case – spot errors. For Franco, whose parents have little experience with college, having hands-on support in class was crucial.

“It was really helpful having the teachers there,” he says. “They check off everything.”

The push to provide direct assistance to high school seniors applying for college is one small slice of Riverside County’s efforts to help students prepare for, enroll in, and ultimately graduate from college. Since 2014 the county has also expanded student access to college counselors, improved parent engagement and bilingual services, and helped students fill out the Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA). As a result, graduation rates, college enrollment, and FAFSA completion are up across the county. This year the California Student Aid Commission took Riverside County’s FAFSA completion challenge, called “Race to Submit,” and implemented it statewide.

County leaders say the secret is in relying on rigorous data collection and analysis to identify and address the actual needs of its students and families. In their case, that meant adapting to a student population that is two-thirds Latino and 63 percent eligible for free and reduced lunch.

It’s a strategy that education advocates say could serve as an important model for chipping away at a broader issue: improving outcomes for California’s Latino students, who despite making up the majority of the state’s student population, still face some of the greatest barriers to college enrollment and completion for any demographic, according to a report released last month.

“We often ask [students and families] to navigate a system not designed for them, instead of meeting students where they’re at,” says Ryan Smith, director of Education Trust-West, the nonprofit behind the report. “We haven’t faced the reality that this state will succeed or not succeed by the way it treats its Latino students.”

Similar stories across California

In some ways Franco’s story echoes that of millions of other Latino students across California. His parents are both Mexican immigrants – and according to Education Trust-West, about 80 percent of the state’s Latino youth are of Mexican heritage. Neither attained a bachelor’s degree, which puts them with about 90 percent of Latinos age 25 and over. Their combined annual income, meant to support a household of seven, is just under $50,000. Among all ethnic groups Latino students “are the most likely to be low-income while in college,” Education Trust reports.

But Franco’s current circumstances aren’t the sole arbiters of his future. “The data is an indictment of the system we’ve created, not a reflection of the students and families in this state,” Mr. Smith says.

In 2014, Riverside County set out to prove it. Armed with a $1.7 million grant from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, county officials formed the Riverside County Education Collaborative (RCEC) – a coalition of local district leaders, school counselors, representatives from regional colleges, and other community stakeholders. Its goals include raising FAFSA completion from 52 to 93 percent, boosting post-secondary enrollment from 52 to 65 percent, and improving college readiness using metrics provided by both the state university and community college systems.

They aim to hit those targets by June 2019 – in a region that has the lowest degree-attainment level among adults for a metro area its size.

They began with the numbers. The county asked all 23 districts to sign a data-sharing agreement that would give the RCEC leadership access to student transcripts and other information. Riverside is also a leader in the use of the National Student Clearinghouse service that tracks postsecondary enrollment, attendance, and performance for up to seven years after a student graduates from high school. The county pays to have all its high schools subscribe to the service.

The data showed them not only which students were struggling, but how, and where they needed more support. “We’re looking at every transcript, finding out what are the obstacles and barriers that are getting in their way,” says Mark LeNoir, assistant superintendent of education services for Val Verde Unified School District, which includes schools in Moreno Valley and Perris, Calif. “We felt that if we’re going to move forward, we’re going to have to look at things through the lens of systems.”

For instance, Mr. LeNoir says they found that many students couldn’t turn to their parents – who had never been to college – when filling out FAFSA and college application forms and figuring out exactly what the course requirements were for state university systems. But there also weren’t enough school counselors who were trained to answer students’ questions about those issues. So RCEC developed a counselor network that focuses on professional development and college and career training.

Today 500 counselors across the county are part of the network – the biggest such network in the state. And not only is morale up among local counselors, who typically feel overworked and undervalued, but they’re also more invested in student success, says Robin Ellison, a school counselor at Rancho Verde.

“Just to have the support, and have people see value in the work that we do, is huge for us,” she says. “That FAFSA push is something that counselors take personal now.”

Getting comfortable with data

Numbers proved when Riverside was doing it right: like when the county’s graduation rate shot up to 89 percent in 2016, making it second only to Orange County among the state’s largest counties. Or when its countywide completion rate for state university courses rose from 28 to 44 percent between 2010 and 2016. Or when 90 percent of the 2017 graduating class at Val Verde Unified successfully completed their FAFSA and California Dream Act applications, the highest rate for any school district in the nation.

But often school leaders would come into the monthly RCEC meetings with high hopes for a program they’d implemented, only to be crushed by how little they’d moved the needle.

“The difficult piece was getting comfortable with the data, when … we didn’t get the gains we expected,” says RCEC director Catalina Cifuentes. “The challenge was getting to the point where we were OK with saying, ‘We’re doing great things, but we’re not there yet.’ ”

Still, RCEC leaders say that the most important takeaway of their experiment so far is how changing systems also helps change attitudes – and vice versa. “Half of the battle is when you can get your districts to believe that the students can do it,” says Judy White, superintendent for Riverside County.

“This is a great example that if given the right support and assistance, those students will meet the expectations,” adds Smith at Education Trust. “It shows that students can achieve.”

For his part, Franco believes. The Rancho Verde student almost bristles with excitement when he talks about his AP statistics classes, the engineering courses he wants to take in college, the grants and scholarships he’s got lined up, the solar panels he hopes to someday build himself. “Technology’s booming, and there's just a bunch of stuff you can do,” he says, grinning. “I want to be a part of that.”

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

People once at odds don’t try to even the score

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By The Monitor's Editorial Board

In Colombia and Tunisia, truth commissions are working to help heal the effects of old divisions. Nepal and Sri Lanka are weighing similar moves. While any of these efforts could serve as hopeful possibilities for other countries in conflict, perhaps the best example of reconciliation is Rwanda. A University of London scholar writes In Foreign Affairs magazine of “the immense steps” that Rwanda has taken to achieve harmony between the Hutus, the ethnic majority, and the minority Tutsis since its genocide 23 years ago. Genocide suspects who confessed and showed remorse have been reintegrated into their villages. Civic education has brought the two groups together. The economic gap between them has been reduced. People once at violent odds now tend the same fields, send their children to the same schools, and often intermarry. Such daily activities tested each individual’s commitment to the community. They have created a foundation of trust. Most Rwandans, the scholar notes, “have chosen to get on with life rather than settle old scores.”

People once at odds don’t try to even the score

After he declared victory over Islamic State (ISIS) on Dec. 9, Iraqi Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi made an important promise. He plans to address the wide distrust between Sunnis and Shiites – which was the root cause of ISIS’s rise three years ago.

“Iraq today is for all Iraqis,” he said, citing the rare unity of military forces during the final push against ISIS.

Mr. Abadi is now the latest world leader searching for national reconciliation and a healing of social wounds after the end of an armed conflict or the collapse of an authoritarian regime.

In the West African nation of Gambia, a new president, Adama Barrow, plans to set up a truth commission to shed light on the human rights abuses committed during the two-decade rule of his dictatorial predecessor, Yahya Jammeh. “We must understand what happened under Jammeh so we never slide back,” says Abubacarr Tambadou, Gambia’s minister of Justice.

In Colombia last week, President Juan Manuel Santos took a critical step in cementing a 2016 peace deal between the government and the country’s largest guerrilla group. He formed a truth commission that will reveal the full extent of atrocities committed during a half-century of civil war. And another tribunal will administer justice for major wartime atrocities.

In Tunisia, a truth commission set up after the 2011 Arab Spring continues its work to uncover the misdeeds of a previous dictatorship. Meanwhile, Nepal and Sri Lanka are weighing similar efforts after wars in those countries.

While any of these efforts could serve as hopeful possibilities for other countries currently in conflict – Syria, Myanmar (Burma), Libya, Ukraine, Yemen, and South Sudan – perhaps the best and most recent example of reconciliation is Rwanda, 23 years after a genocide there killed 800,000.

In a new article in Foreign Affairs magazine, University of London scholar Phil Clark writes of “the immense steps” that Rwanda has taken at the individual, local, and national levels to achieve harmony between the Hutus, the ethnic majority, and the minority Tutsis.

“No other country today has so many perpetrators of mass atrocity living in such close proximity to their victims’ families,” he writes after conducting more than 1,000 interviews with everyday Rwandans over 15 years of research.

The country used community courts called gacaca between 2002 and 2012 to prosecute 400,000 genocide suspects. Those who confessed and showed remorse were shown leniency and reintegrated into their villages.

Rwanda’s leader, Paul Kagame, has used annual commemorations and civic education to bring the two ethnic groups together. The country is alert to divisive ethnic propaganda. And victims on both sides found their common suffering drew them together.

Most of all, the economic gap between Hutus and Tutsis was reduced, “helping redress some of the deep grievances that have bedeviled local communities for decades,” Mr. Clark writes.

“Many communities have … formed economic cooperatives, incorporating both Hutus and Tutsis, to pool resources such as seeds or fuel. They have started these not only out of economic necessity but also in the hope that working together will start to mend historical rifts,” he adds.

People once at violent odds with each other now tend the same fields, send their children to the same schools, sell goods to each other in the marketplace, and often intermarry. Such daily activities tested the ethics of each individual’s commitment to the community. They have created a foundation of trust.

The risk of mass violence now seems remote. While progress toward democracy has slowed, Rwanda shows how a country torn apart by war or cruel leaders can reconcile with the right mix of justice, dialogue, and socioeconomic development. Most Rwandans, concludes Clark, “have chosen to get on with life rather than settle old scores.”

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Surprise – I was judging them!

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By John Biggs

Today’s contributor has some pretty visible tattoos illustrating people, moments, and Bible passages that are meaningful to him. A while back, he was spending time with some folks who didn’t like them. And he didn’t like that they were judging him on his appearance. But he began to see that his being angry wasn’t any better than what they were doing. He was judging them! He realized that if he was going to honestly love God, then he couldn’t take a negative view of God’s children. That doesn’t mean condoning bad behavior. But it does mean seeing that what God created and supports doesn’t include anything unlike divine Love. He began to feel a spiritual love for these people as God’s children, and he quit waiting for them to love him. And that’s when their condemnation and criticism of him just melted away. Feeling God’s love and loving others for what they are spiritually brings remarkable change into our lives.

Surprise – I was judging them!

I have some pretty visible tattoos – illustrations that remind me of people, moments, and Bible passages that are meaningful to me. A while back, I was spending time with some folks who didn’t like them – and they let me know it. And I didn’t like that they were judging me on my appearance.

But I was also bothered by something else. I began to see that my anger against their judgment wasn’t any better than what they were doing. I was judging them!

I started to actively pray about the situation, which is something I’ve found helpful when there’s a problem or situation that needs healing. And I realized that if I’m going to honestly worship and love God, who I’ve learned from my study of Christian Science is all good, then I can’t cut down His creation – made in the spiritual image of God - in words or thought. That creation includes each of us.

That doesn’t mean I condone bad behavior or judgment, which isn’t in line with anyone’s true, spiritual identity. But it does mean that the way wrong gets corrected is by me getting clear first that what God created and supports doesn’t include anything negative or unlike divine Love. It means seeing my fellow man from a spiritual perspective, as innately good.

I thought about Christ Jesus’ powerful example of this. Even as he was being crucified, he said, “Father, forgive these people! They don’t know what they’re doing” (Luke 23:34, Contemporary English Version). Jesus so fully expressed his divine nature as the image, or expression, of divine Love, that he couldn’t stop loving – no matter how desperate the situation.

Of course, my circumstances weren’t anything like Jesus’ circumstances. But couldn’t I do that too? Couldn’t I let my love for others be based only on the fact that God loves me already – and loves them too?

It was as straightforward as that. I realized that the way God sees me is so much more important than the way others see me. And catching a glimpse of the way God sees all of us is healing. I began to feel a spiritual love for these people as God’s children, and I quit waiting for them to love me. And that’s when their condemnation and criticism just melted away.

Feeling God’s love and loving others for what they are spiritually brings remarkable change into our lives. Doesn’t the world need more of this?

A version of this article aired on the Nov. 28, 2017, Christian Science Daily Lift podcast.

A message of love

Castoffs from castaways

A look ahead

Thanks for reading the Daily today. Tomorrow, Howard LaFranchi will examine President Trump's often unilateral approach on foreign-policy issues from North Korea to Jerusalem – and how that squares with his vow to restore US leadership in the world.