- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 8 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Monitor Daily Intro for February 21, 2018

Yvonne Zipp

Yvonne Zipp

The Rev. Billy Graham was so widely admired he was known as “America’s pastor.”

His was a gentler form of evangelism, which refused to speak ill of other belief systems, G. Jeffrey MacDonald writes in a Monitor appreciation of the renowned preacher, who received every honor from the Congressional Gold Medal to a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame.

“He would say, ‘I’m here to talk about Jesus,’ ” said biographer Grant Wacker.

And while Mr. Graham counseled presidents from Harry Truman to Bill Clinton – becoming the most frequent visitor to the Lincoln Bedroom – he eschewed politics.

“He was never involved in the religious right or the Moral Majority,” said biographer Larry Eskridge. “He had bigger fish to fry, in his mind, and felt that getting involved in politics hurt his attempt to get the message out.”

In the 1950s, the son of a North Carolina dairy farmer found a passion for crossing boundaries: He broke the law in 1953 by removing the ropes that separated black and white worshipers at a Chattanooga revival.

Graham was the first evangelist to speak behind the Iron Curtain. He preached to millions with the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., and during apartheid, he refused to visit South Africa until the government allowed integrated seating at his events.

As Jeff writes, “being a breaker of boundaries and friend of the scorned certainly didn’t hurt his stature in the legacy of Christendom.”

Jeff was interviewed about Graham today on SiriusXM. Here’s a brief clip from the interview sharing one insight into the late preacher’s popularity.

Now, here are our five stories of the day, highlighting overcoming limitations, the business case for workplace equality, and the nurturing qualities of insects.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

After Parkland, a new generation finds its voice

Henry Charman says he will never forget the day he heard about the Sandy Hook shooting. His social studies teacher broke down in tears in front of the class. Now, the Parkland shootings have caused the senior to rethink his views of guns. “It’s really hard for me to say, because I am sort of a stereotypical Montanan,” he says. “I own guns and I hunt. But if giving up my guns meant there would be no more school shootings, I would do it in an instant.”

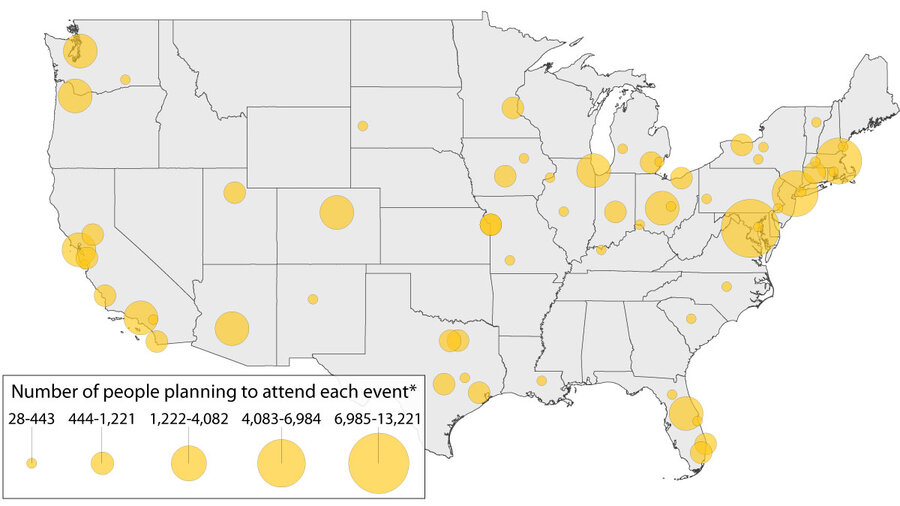

After the Valentine’s Day shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School changed their lives, many of the surviving students have described a kind of awakening, or a proverbial political coming of age. Suddenly, the generation born just after Columbine has begun to mobilize, planning a nationwide march for next month and this week taking a bus to the state Legislature to argue for changes in Florida’s gun laws. Across the country, too, thousands of mostly 17- and 18-year-old high school students are doing the same. Though the impact of their actions remains to be seen, the solidarity has given many their own strange sense of generational identity – and a growing anger at those who came before them. “It’s kind of ridiculous that at this point it is up to kids, who aren't even of legal age to reform the country, so we can feel safe,” says Casey Sherman, a 17-year-old junior from Stoneman Douglas. “I absolutely think there should have been so much reform in all of the years past, since Columbine.”

After Parkland, a new generation finds its voice

On a bus to Tallahassee on Florida’s State Road 91 on Tuesday, Drew Schwartz sits with a scrum of fellow students planning the logistics of their march on the state capital, just hours away.

“Right now it’s all hands on deck,” says Drew, a 17-year-old junior at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Fla., site of the nation’s most recent mass shooting and where 14 of these students’ fellow classmates died. “We divide the work the best we can, and then divide the work based on who is best at what,” he says in a phone interview with the Monitor from the bus. “This march will be crucial to the core campaign.”

But even amid the furious scramble of these determined student activists, Drew can only take a breath and reflect on the maelstrom that began last week on Valentine’s Day. As a student board member, he was bringing carnations to classrooms when the first shots rang out, and the course of his life was suddenly altered.

“This is a really new thing for me,” says Drew, mentioning how strange it feels to have gone from a kid who liked to hang out with friends, go to the movies, or plan homecoming and prom activities with others, to a committed activist. “Before this I had my opinions, but I was never involved. It's really sad that something like this has to happen for us to really open our eyes and fight for change.”

Across the country, too, thousands of mostly 17- and 18-year-old high school students are saying the same. The Parkland mass shooting, and especially the immediate and emotionally resonating response of the Stoneman Douglas students, has sparked something, they say, something akin to an awakening or a proverbial political coming of age. And many point to the dramatic speech of senior Emma González on Saturday. “We are going to be the last mass shooting,” she proclaimed, brandishing her AP Government notes.

“Something that's been in my brain, something that I've been thinking about since this started, is that I feel like people underestimate the power of students when it comes to change like this,” says Evie Wybenga, a senior at Andover High School in Massachusetts.

Speaking with 'moral authority'

As the country watches hundreds of groups of high-school aged students begin to organize, this emerging power of students may be changing the long stalemate in the nation’s debates over guns, some experts say. Students around the country have been spontaneously planning marches, sit ins, and class walkouts, connecting through social media and the political hashtag, #MarchForOurLives.

“They are speaking with a moral authority, and there’s nothing more damning than having adult disfunction called out by a kid,” says Jerusha Conner, professor of education and counseling at Villanova University in Pennsylvania. “That they shouldn’t have to know better than we do about what’s at stake, that they shouldn’t have to be thinking about this and filling that vacuum in national leadership.”

Still, the many hurdles that have frustrated gun-restriction advocates for decades remain, many observers say. Gun ownership is a constitutionally guaranteed right, with a long history of US Supreme Court precedents. And while states and localities have leeway to restrict the time, manner, and place in which a firearm may be carried, the interstices between government regulations and fundamental rights feature ferocious partisan battles.

“This is definitely something new [in the nation’s gun debates],” says Christopher Huff, professor of history at Beacon College in Leesburg, Fla., who has studied the protest movements of the 1960s and the rise of conservative student activism. “From my experience, when students are reacting, instead of being proactive about their activism, they don’t gain a lot of ground. An expression of frustration and anger can take it a little further, but that doesn’t always translate into, there’s something that’s going to gain traction here.”

“Are we going to see something here where the students themselves and others start a sustained movement?” Professor Huff says. “I’d be hesitant to go that far at this point, but I’m thinking that this might move the conversation forward a little bit, in some kind of direction forward rather than circular.”

On Tuesday, President Trump moved to ban the sales of “bump stocks,” which can make semi-automatic rifles fire at automatic speeds. The president also agreed to host a “listening session” on Wednesday afternoon with survivors from Stoneman Douglas, Sandy Hook, and Columbine, the White House said. Lawmakers revived interest in bipartisan legislation introduced last fall by Senators John Cornyn (R) of Texas and Chris Murphy (D) of Connecticut, a proposal that would improve the reporting process between state and local agencies to keep firearms out of the hands of dangerous people.

In Florida, open carry legislation has stalled while some lawmakers signalled that they would introduce new legislation to raise the legal age to purchase a semi-automatic rifle from 18 to 21 and institute a 3-day waiting period for such sales. Even so, on Tuesday the House rejected a proposal that would have banned certain semiautomatic rifles.

“Everything is in place for a mass movement,” says Jacob Udo-Udo Jacob, a visiting international studies scholar from Nigeria at Dickinson College in Carlisle, Pa. “There is a trigger event – the mass shooting; there is a technologically-driven mobilizing structure – social media; there is a huge national grievance – a series of mass shootings; there are many compelling personal stories.”

“But a lot will depend on the how exponential the students’ voices can become,” says Professor Jacob, who studies the practices behind social-media-fueled movements such as the #BringBackOurGirls campaign in response to the Boko Haram kidnappings in his home country. “How they challenge the power structures will be determined by their capacity to create and represent alternative values and interests. These could be values of compassion, spirituality and/or loving kindness. But they won’t make any change simply by organizing protest marches on Washington,” he says.

Compelled to speak out

Many high school juniors and seniors, however, just feel compelled to speak out. Many self-consciously see the beginnings of a new political consciousness, fueled by a frustration that has often boiled over into rage at the monotonous cliches they’ve heard after mass shooting after mass shooting.

“There was an announcement at the end of the day [of the Parkland shooting] that offered ‘thoughts and prayers’,” says Ms. Wybenga, the senior at Andover High in Massachusetts. “We are tired of only hearing 'thoughts and prayers'.”

Her outrage over the platitude, in fact, spurred her into action, she says. She and friend Charlotte Lowell had an idea: instead of ‘thoughts and prayers,’ let’s stage a sit-in. They discussed logistics, talked to some teachers, and then posted their plan onto social media that same night.

“And word spread extremely quickly,” Wybenga says. “We were not the only ones feeling this way. People were more than happy to be a part of it. By the end of the night, large numbers of people had heard about it and were active in spreading the word themselves.”

In the end, upwards of 700 high school kids in the area participated in the sit in on Friday, she says. “I was shocked. But I was incredibly impressed and I felt empowered, and I felt an incredible sense of community within in the high school, that so many people care.”

At the same time, this sense of solidarity has given many their own strange sense of generational identity – and a growing anger at those who came before them.

“It’s kind of ridiculous that at this point it is up to kids, who aren't even of legal age to reform the country, so we can feel safe,” says Casey Sherman, a 17-year-old junior at Florida's Stoneman Douglas High, in an interview with the Monitor. “I absolutely think there should have been so much reform in all of the years past, since Columbine,” she says. Instead, “they made military grade weapons available – they are slacking in that sense.”

Like so many of her peers, Casey, felt the need to spring to action after the shooting that altered her life. Casey, who was on the bus with Drew to Tallahassee, is also leading the planning for the Parkland March at the end of March. She was up late Monday night creating local Facebook, and Instagram accounts for the emerging #MarchForOurLives movement, and then woke up Tuesday and created the Twitter account. Her first tweet, in fact, was shared over 300 times in just a few hours.

Rethinking and moving forward

Henry Charman, an 18-year-old senior at Hellgate High School in Missoula, Mont., also started a Twitter account to promote local participation in a massive student-led walkout planned for noon on Wednesday nationwide called Student Walkout Against Gun Violence.

“We were talking amongst ourselves that it's messed up how normal it is now to get an alert on your phone that there's been another mass shooting,” says Mr. Charman. “That's not the future I saw when I was a kid.”

But when he was a kid, he says, he never forgot the day when he heard about the Sandy Hook Elementary School massacre of 6- and 7-year-old students and adult administrators in Newtown, Conn. His social studies teacher, he says, had gotten the news and started to cry in front of the class.

“It was something that I won't forget – how affected he was by it,” says Charman. “It just really got to him and that got to me as well."

And now, the Parkland shootings have caused him to rethink his views of guns – though he’s still not sure where he stands on possible solutions to the problem.

“It's really hard for me to say, because I am sort of a stereotypical Montanan,” Charman says. “I own guns and I hunt. But if giving up my guns meant there would be no more school shootings, I would do it in an instant.”

Which highlights a long-term trend that this generation’s coming-of-age, experts say, could mark a significant change. Younger Americans are already less likely to be gun owners than older generations were at the same age, and the Parkland shooting might be the defining political issue for those just now thinking about their responsibilities as voters and citizens, observers note.

“The significance of the youth movement is a turning point,” says Kris Macomber, professor of sociology at Meredith College in Raleigh, N.C., and an expert in social movements and gun violence. “After Sandy Hook, we didn't see videos of AR-15 owners destroying their guns or turning them in,” she says. “We are seeing this now. The narrative has shifted. When the narrative shifts, behaviors change.”

Drew, the junior from Stoneman Douglas, has been spending the past two days doing the work of an on-the-ground activist. With a group of fellow students, he's met with seven state senators and representatives since arriving on Tuesday, he tells the Monitor by phone on Wednesday.

The experience, he says, has been invigorating, even as events throughout the day showed these students the difficult political path that lies ahead. Not long after they arrived on Tuesday, the Florida state House blocked a measure that would have banned many semiautomatic guns, a vote that shocked and dismayed a number of his peers.

Even so, “they’ve made me more hopeful,” Drew says of his meetings with lawmakers on Wednesday. “I feel like the people we have talked to have listened to us and are taking in our perspectives. I do think there is hope, and we are moving in the right direction.”

“This trip, them listening to us – it’s all taking a step forward,” Drew says.

Story Hinckley, Noble Ingram, and Rebecca Asoulin contributed reporting from Boston.

*Event attendees estimated from Facebook event statistics

Share this article

Link copied.

The origin – and original purpose – of a Russian ‘troll farm’

The Internet Research Agency indicted by Robert Mueller last week has been covered for years by the Russian media, who started covering its tactics five years ago, when it was established as a tool for domestic disinformation. One former employee told The Washington Post: "I arrived there, and I immediately felt like a character in the book '1984' by George Orwell – a place where you have to write that white is black and black is white."

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

The “troll farm” indicted last week by special counsel Robert Mueller for allegedly meddling in US elections has not been hiding in Russia. Indeed, it has been operating in plain sight for five years in St. Petersburg, under the name “Internet Research Agency.” Moreover, it has received a good deal of critical Russian media attention for much of that time – not as a tool for meddling in US elections, but for doing so domestically. According to Russian investigative reporters, “trolls” would spend 12-hour shifts posting on various social media platforms about current events such as the war in Ukraine, the murder of Russian opposition leader Boris Nemtsov, and other controversial domestic topics. Invariably, they were instructed to adopt a pro-Kremlin tone. But while the system is run by private businesses to the benefit of the state, the origins and purpose still remain obscure. “Who are these trolls, why are they needed, who created them?” asks Olga Kryshtanovskaya, director of Kryshtanovskaya Labs. “This is not a subject we have much information about, and it's not something Russian society is discussing.”

The origin – and original purpose – of a Russian ‘troll farm’

For many Americans, last week's indictment of the Russian “troll farm” by special counsel Robert Mueller was the first time a spotlight had been shown on the enterprise that allegedly meddled in US elections.

But in Russia, the Internet Research Agency (IRA), as the organization is best known, has already been in the public eye for five years. And hiding in plain sight, it has received a good deal of critical Russian media attention for much of that time – not as a tool for meddling in US elections, but for doing so domestically.

The IRA is a well-funded “internet marketing” operation that may perform commercial functions, but has become notorious for its political activities. These include loading Russian social media with pro-Kremlin commentary, blogs, postings, and graphic content. Experts believe there are several such operations around Russia, some aimed at regional audiences.

Unlike Soviet times, when operations would have been conducted from a secret facility surrounded by barbed wire, these agencies have no obvious Kremlin fingerprints on them and are mostly staffed by mostly youthful, regular Russian computer geeks. The outsourcing of political agitation to friendly businessmen, who owe the Kremlin favors, appears to be a hallmark of the Vladimir Putin era, most analysts agree.

The IRA appears to be financed by Yevgeny Prigozhin, a food caterer who became a billionaire thanks to state contracts, also known as “Putin's chef” thanks to his lavish hosting of presidential birthday parties. Why Mr. Prigozhin's outfit decided, probably some time in 2014, to start up an “American department” to create specific English-language content for US social media consumers, appears to remain a mystery, as does its links to the Russian government and security services. Regardless of the IRA's provenance, Russian experts remain dubious about the actual impact of its messaging, even on domestic public opinion.

“I don't doubt that there were also attempts to influence elections in the US. The phrases, approaches, and intonation used in the Russian internet seem very similar to those that were used in US social media,” says Lyudmila Savchuk, a local journalist who infiltrated the IRA for a couple of months in early 2015 with the aim of reporting on its activities. “As to the actual influence of all that, well, it's very difficult to estimate.”

Sharks in cyberspace

Put to work in the Russian department, Ms. Savchuk and scores of other “trolls” would fulfill 12-hour shifts posting on Facebook, VKontakte (the Russian equivalent of Facebook), Twitter, Instagram, and LiveJournal using false identities and with masked IP addresses to meet quotas.

“It's a very big operation. I am sure that the 13 people named in the indictment is far from complete,” she says.

The trolls' main focus would be on current events like the war in Ukraine, the murder of Russian opposition leader Boris Nemtsov, and other controversial domestic topics. Invariably, they were instructed to adopt a pro-Kremlin tone.

Savchuk was a source for one of the most detailed English-language exposes of the St. Petersburg troll farm, reported for The New York Times Magazine by Adrian Chen almost three years ago. But reporting in independent Russian media has been sounding alarms about the troll farms for years, including the St. Petersburg local outlet Fontanka, the business news agency RBK, and the independent TV station Dozhd.

“Prigozhin's factory is just part of a huge system with many branches that aims to shape public opinion,” says Stanislav Belkovsky, president of the Institute of National Strategy in Moscow, an independent think tank. “There is nothing surprising in the fact that such a system exists, but it was a bit of a surprise to learn that it works not only in Russia but also outside the country.”

Internet usage in Russia has exploded over the past decade, with up to 70 percent of the population accessing it every day, says Kirill Rodin, a communications expert with the state-funded VTsIOM public opinion agency. He says it's only recently that people have become aware that cyberspace might be shark infested.

“You can meet not only friends, but also swindlers, con artists, and peddlers of fake news,” he says. “The naive time of fascination with the internet is over, and Russians are learning to take a more sober approach to news and declarations made in this space.”

He says the impact of internet trolling may be overstated. “A lot of studies done during the last Duma elections [in 2016] found that candidates who put a stake on internet advertising as their main means of agitation failed badly. Voters seem to follow more traditional means of promotion more closely. But we have few surveys on how internet information flows influence public opinion more generally. My guess is that it's minimal, and focused on very local segments,” he says.

But anecdotally, internet trolls do affect candidates themselves. “We feel the pressure,” says Igor Yakovlev, press secretary for presidential candidate and long-standing opposition politician Grigory Yavlinsky. “It is not constant, it happens from time to time, but we do suffer from troll attacks.... Sometimes these are simple insults. Sometimes it's tougher-worded reactions to our positions, particularly on foreign policy. We try to ban such accounts but when massive attacks occur, it is rather difficult to contain. When we experience a huge wave of such negative comments, it becomes clear that trolls are doing their job.

“We gradually get used to trolling as a fact of political life,” Mr. Yakovlev adds. “We do not have evidence to prove who is behind it.”

‘Who are these trolls?’

The phenomenon seems to have its roots in 2011, when Russia saw both a surge in internet use and the rise of a mass movement of protest over allegedly fraudulent Duma elections. Opposition leaders like Alexei Navalny took to social media to dramatize charges of official corruption and to organize rallies against it – something that Mr. Navalny has excelled at. (Navalny's personal blog site has currently been blockaded by Russian authorities.)

“Russian authorities seem to have initiated the creation of this system [of troll farms] for internal use several years ago, when opponents like Navalny were getting a lot of support, especially among the youth, with the help of the social nets,” says Olga Kryshtanovskaya, director of Kryshtanovskaya Labs and Russia's leading specialist in elite studies.

“The authorities didn't understand much about such things, and they were sluggish,” she says. That's when intermediaries stepped in to do the job. “Nobody really knows who Prigozhin is or the degree of influence he wields. Who are these trolls, why are they needed, who created them? This is not a subject we have much information about, and it's not something Russian society is discussing.”

The Kremlin connection to internet influence operations such as Prigozhin's may be a tenuous one, says Masha Lipman, editor of Counterpoint journal, published by the Institute for European, Russian, and Eurasian Studies at George Washington University.

“The web is an environment that's free for everyone to use. The proportion of loyalists to critics on the internet is the same as it is in Russian society at large. There are far more loyalists than critics, and they can be just as passionate,” she says.

“There is no shortage of money in Russia for funding any operation that is seen as currying favor with the Kremlin. People like Prigozhin may do this, not because they receive instructions but because they see it as pleasing to authority. And, indeed, it can't be unpleasant for Putin, or he'd put a stop to it. But the degree of government involvement is unclear, and it may never be known,” she says.

Ms. Lipman notes that some wonder why Putin, who enjoys 80 percent public approval ratings, needs to have his image constantly burnished by secretive internet trolls. “I think the answer is in the logic of super-majority rule – the impression of total social support – which is Putin's method,” she says. “You can never have enough, and you must never leave anything to chance.”

Reaching for equity

Gender equality as ‘trade secret’? Firms awaken to a long-dawning idea.

Should efforts to recruit and retain talented women be regarded as a trade secret equivalent to the formula for Coca-Cola? IBM thinks so. Behind a noncompete lawsuit that puzzled business analysts lies a growing realization at more companies: Gender equity is good for the bottom line.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

The tech giant IBM has just won a prize for its innovative programs to recruit and promote more women. A woman who helped run those programs, Lindsay-Rae McIntyre, was hired away earlier this month by Microsoft, and IBM is crying foul because she had signed a “non-compete” clause in her contract. Women’s leadership strategies, it seems, have become trade secrets like any other. That’s because female-friendly workplaces are good for both the atmosphere in the office and for the bottom line: They attract the top talent. IBM’s programs range from giving women more generous maternity leave to harnessing artificial intelligence and algorithms to track how women are hired and promoted so that no unwitting bias creeps in. Gender equity in the workplace is a long way away – only 27 of Fortune 500 CEOs are women – but more US firms are seeing equity as a valuable goal. Says Debora Bubb, IBM’s chief inclusion officer, “the business case is increasingly clear.”

Gender equality as ‘trade secret’? Firms awaken to a long-dawning idea.

In the tech industry, “non-compete” agreements are not uncommon; they prevent employees from job-hopping to rival firms and taking inside knowledge with them. But here’s a novel twist: The latest tussle of this sort is not about someone with key technical information.

It’s about a woman promoting gender equality.

When IBM lost its chief diversity officer, Lindsay-Rae McIntyre, to rival Microsoft earlier this month, Big Blue went to court to stop her working for a year.

Ms. McIntyre, IBM said in a statement, “was at the center of highly confidential and competitively sensitive information that has fueled IBM’s success" in diversity and inclusion.

It seems that ways to recruit talented women, then retain and promote them, have become proprietary business data, just like more traditional trade secrets. In the eyes of a growing number of companies such as IBM, gender equality is central, not peripheral, to their business success.

That’s because both the bottom line and the office atmosphere benefit from female-friendly workplaces, studies have found. IBM officials say they are convinced of that, and last month the company won an award from Catalyst, a global nonprofit promoting women’s leadership, for its efforts.

“Companies are going to start looking more at these types of programs,” not only to attract but also to retain workers, predicts Mary Pharris, director of business development at Fairygodboss.com, a website that serves as a forum for women to swap information about working conditions at different companies.

Pressure for progress

Amidst widespread concern among women about unequal pay, less-than-generous family leave policies, and workplace harassment that helped spawn the #MeToo movement, women rarely make it to the top of American business. Only 27 Fortune 500 CEOs are women.

But there are signs that progress may be picking up speed. Already, women enter the workforce more educated than men, and employers competing to attract high-skilled workers are finding that woman-friendly and ethnically diverse workplaces give them an edge with the rising cohort of Millennials.

IBM is trying to sharpen that edge, and some of its policies are hardly rocket science. One is simply to offer generous paid family leave, bumping it up last year to 20 weeks for moms, and 12 weeks for dads, partners, and adoptive parents.

Another is a program the company calls “Elevate Tech,” providing a mix of mentoring, extra training, and networking opportunities to nurture the career development of high-potential women. The goal is to rebalance a talent pool that, here as elsewhere, grows increasingly male-heavy the higher up the company ladder you go.

Jen Jones, a new IBM worker, is a beneficiary of another program to create opportunities for women who’ve been out of the work force for two years or more; often because they’ve been looking after children.

In the fast-moving tech world, that kind of absence can really set a woman back. And women are particularly prone to drop out of jobs in the fields of science, technology, engineering, and mathematics. When they want to return to work they have talent and education, but their skills need freshening.

Luring talent back to work

The Tech Re-Entry program offered Ms. Jones a 12-week internship, with the promise that IBM would be interested in hiring her. “It allows you to cut your teeth in a safe space,” she says.

Starting at the Weather Company, an IBM subsidiary, Jones drew on her marketing background while pushing deeper into data analytics. “We were using math that nobody on our team had ever used before,” she recalls.

It served her well. She eventually got a job in IBM’s Human Resources department, using data analytics to promote more of the kind of diversity policies that she had already experienced as an intern. Her team is trying to ensure that, as IBM uses artificial intelligence to track the skills and performance of more than 300,000 employees around the world, no unwitting bias against women or racial minorities creeps into assessments.

Jones says her manager is framing the difficult task this way – to “quantify the unquantifiable.” Yet IBM thinks it is an important nut to crack. “Everybody matters,” says Jones. “You don’t want to lose anybody who ... really loves and cares about the work they do.”

Debora Bubb, IBM’s chief inclusion officer, says a diverse workforce is both a moral imperative and an important tool to recruit and retain top talent in a competitive industry. “The business case is increasingly clear,” says Ms. Bubb, whose purview includes the diversity efforts that McIntyre oversaw.

Recent research backs her up. The companies with most women on their executive teams are 21 percent more likely to make above-average profits than those with the worst gender balance, according to a new study by McKinsey, the consulting group.

And an analysis by Katharine Klein of the University of Pennsylvania's Wharton School, while reaching a more tentative conclusion, said studies show a “small but dependably positive” effect of female executives on corporate success.

But it takes a conscious effort to diversify a workforce. Companies cannot expect that “diversity and inclusion automatically happen,” Bubb says.

That message has begun to resonate throughout US boardrooms, if only because of the potential threat that a loss of trust among female workers poses. Women make up nearly half the US workforce, yet some polls find that they are less satisfied than men about a number of issues, from pay to work-life balance.

Not at every company, however. French cosmetics firm L'Oreal topped a recent gender equity ranking by Equileap, a group encouraging investment in workplace equality, partly because it has virtually no pay gap between men and women.

And when Rockwell Automation, a Wisconsin-based industrial firm, realized that white men were staying loyal to the company longer than women or people of color, management made those white men “diversity partners” in a drive to make the business more inclusive.

Workplace culture as a #MeToo solution

How responsive companies are to women’s concerns “is going to be a huge piece of their ability to retain their talent,” says Ursula Mead, founder of InHerSight.com, another online platform where women post scorecards on the firms that employ them.

“This past year has been huge and eye-opening for companies and women about the issues that still remain” to be addressed, she says. Where once the focus was on pay and parental-leave policies, now the spotlight is also on revelations of sexual assault and abusive behavior from Silicon Valley and Hollywood to halls of power in Washington.

Almost every large US employer offers training programs to counter sexual harassment in the workplace, and many impose “zero tolerance” policies too; there’s one at IBM. But some experts say the simple fact of promoting more women to high-ranking roles can reduce the prevalence of harassment.

They help cultivate an atmosphere where women feel able to speak up against a harasser, for one thing. And when a company’s leaders make a diverse work force a priority goal, that can change the attitudes of men, too, making them more likely to become allies in countering offensive behavior rather than looking the other way.

Even when a company makes a concerted effort to create a positive culture for women, though, the gains come only gradually. “We are really rewarding progress not perfection,” says Julie Nugent of Catalyst, who chairs the group’s awards committee.

Despite IBM’s stated commitment to gender equality, and the programs it has introduced over decades to broaden women’s prospects, women still make up just 26 percent of the company’s managers and executives. And that is enough to put IBM in the top 5 percent of global firms when it comes to gender equality, according to the Equileap study.

Nurturing more female executives

Sree Ratnasinghe is one of those female execs, a graduate of IBM’s program to develop female talent that she says was “just critical to me getting the job that I have today” in cloud computing.

She also credits simple human understanding for her success. When her first daughter was born prematurely, Ms. Ratnasinghe took 15 months off and her managers gave her “amazing support,” she recalls.

Ratnasinghe took six months off when her second daughter was born. “Things really ebb and flow when you're a parent when you're juggling these things,” she says, and her employer has been tolerant of that.

Now she’s not only a fan of the kind of benefits and programs that have helped her thrive, she wants to help extend them. “I would not be where I am today without the support and help of mentors,” Ratnasinghe says. “I'm looking to pay that forward.”

Part 7 of Reaching for Equity, a global series on gender and power.

At Winter Games, a historical diversity on display

Olympics are known for their firsts – take the US women winning their first cross-country gold medal (also the first gold medal for Team USA's only mom). While athletes in the Winter Games still tend to be white and male, Olympians say the increasing diversity of faces on the podium honors the Games' original spirit.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

Hurtling yourself down icy curves at speeds in excess of 80 m.p.h. is no easy task. But convincing people that it’s fun might be even harder. US bobsledder Elana Meyers Taylor excels at both. On Wednesday, she won her third Olympic medal. But she’s also a self-appointed recruiter, bringing more fellow African-American athletes into the sport. When it comes to diversity, she says, “the progress in our sport has been tremendous.” The Winter Games have long been dominated by athletes who hail from chilly European climes, and their descendents. That’s still the case – but inclusion is expanding, whether that means Asian-American ice dancers, or a Mexican cross-country skier. And that, many athletes say, means a truer embrace of what the Olympics is all about: uniting humanity in the pursuit of excellence. “For decades upon decades, everybody just wanted to show up at [the World Championships] and say they beat Canada,” says Kyle Young, a former competitive curler from North Dakota. “Now you can look at some of these fields and say – I don’t have any idea who’s going to win.”

At Winter Games, a historical diversity on display

Viking descendants, you may be crushing the rest of the world with your impressive Olympic medal haul. But in the wake of your victories, a new crop of Winter Olympians is clicking into ski bindings, lacing up skates, and hurling themselves down ice tracks.

And some are winning medals of their own.

For the first time, an Asian athlete – Korean Yun Sung-bin – captured Olympic gold in the skeleton competition, which also included the first-ever African woman and a Ghanaian who financed his Olympic dreams by selling vacuum cleaners.

On ice, Jordan Greenway has broken a 98-year-old color barrier to become the first African-American on a USA Hockey team, and siblings Alex and Maia Shibutani on Tuesday became the first-ever ice dancers of Asian descent to win an Olympic medal.

But it’s women’s bobsledding that has really led the way in diversifying a global sporting festival that was once largely the domain of white people from cold places. And that’s not just good for the individuals. Embracing a wider spectrum of humanity than ever before strengthens the Olympic movement, says American driver and three-time Olympic medalist Elana Meyers Taylor, who won silver Wednesday with brakeman Lauren Gibbs.

“I think diversity and inclusion is very important in the Olympics. That’s part of the Olympic movement – including all the nations and, I think, giving opportunities to countries who may not otherwise have the opportunity,” says Taylor, a self-appointed recruiter who has convinced a bevy of fellow African-American athletes that it would be fun to hurtle themselves down icy curves at speeds in excess of 80 m.p.h. “The progress in our sport has been tremendous.”

The United States is leading the way, she says, but the trend is international. The Nigerian women’s bobsledding team – the first team from an African country to compete in the sport – is led by former USA team members. Having practiced in a makeshift sled, it’s not surprising they finished the first two heats at the bottom of the heap, along with Jamaica – whose pilot also started her career in the US. But top-ranked teams from Britain, Canada, and Germany all have black athletes as well. Germany took gold on Wednesday night, with one of the US teams right behind with silver, and Canada with bronze.

“It’s good to see the world finally catching up,” says Aja Evans, a track and field star from Chicago who was recruited by Meyers and has since pocketed bronze medals at the Olympics and World Championships with driver Jamie Gruebel Poser. They finished fifth on Wednesday.

Transcending nationality

To be sure, diversity at the Winter Olympics remains modest. This year’s US team is the most diverse in Winter Olympic history, but it only includes 10 African-Americans and 11 Asian-Americans out of 244 athletes. Despite having a record number of women, there’s still a significantly larger number of men (109 vs. 135). And many have celebrated the fact that Team USA sent its first openly gay athletes to Pyeongchang this year – but only two: figure skater Adam Rippon, who helped the US win a bronze in the team event; and freestyle alpine skier Gus Kenworthy, who came in 12th in the slopestyle event.

When it comes to international diversity, new countries wading into winter sports can sometimes create a two-tiered field of competition, with huge margins between the bulk of the competitors and the few at the back of the pack from countries like Ecuador, Iran, and Kenya.

But some of the strongest Olympic spirit is seen among less-experienced competitors, as seen at the finish of the men’s 15 km freestyle cross-country ski race last week. When solo Mexican competitor German Madrazo crossed the line, his fellow Olympians from low-snow countries were all waiting for him – and hoisted him up as if he were a team member.

Which, in a way, he was.

Nationalism has become a driving force for Olympic glory, but that wasn’t part of the founding vision. And in some ways these men who were admittedly less proficient on the trail may have better demonstrated what the Olympics is all about: uniting humanity in the pursuit of excellence.

Even countries that don’t have snow and ice, or that haven’t traditionally dominated in Winter Olympic disciplines, are taking the spirit and adding some skills, too.

Curling, for example, has recently seen a huge surge in the competitiveness of Asian teams. The Korean women in particular have shone here, besting all the world’s superpowers and losing only one game so far – to Japan.

“For decades upon decades, everybody just wanted to show up at [the World Championships] and say they beat Canada,” says Kyle Young, a former competitive curler from North Dakota who is here as a spectator. “Now you can look at some of these fields and say – I don’t have any idea who’s going to win.”

Creating a richer Olympic cast goes far beyond adding new countries, though. It’s also about teams and even individuals embracing their unique contributions.

That was a key for the Shibutanis, who took a long road to become ice dancing’s first Olympic medalists of Asian descent. But it goes beyond ethnicity. One of their chief challenges: being siblings in a sport better known for romantic or sensual routines.

“I’ve always believed, whether it’s figure skating or not, that diversity is really important. If you’re sitting through an event full of ice dance teams and you’re seeing the same story told over and over again, that’s not good for the growth of the sport, that’s not entertaining for the viewers at home,” said Alex Shibutani after their bronze-medal performance Tuesday. “And so having a different point of view, which we naturally have because we are coming from a different place, is something that we’ve embraced.”

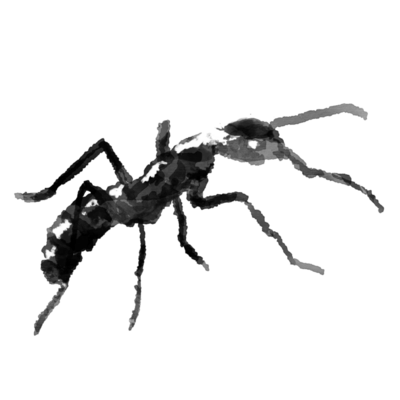

Can altruism exist without empathy? Lessons from the ant world

Our next story shows that the compulsion to help others isn't limited to humans. It also contradicts popular ideas about Darwinian evolution promoting only selfish behavior – to say nothing of the Aesop fable about ants unwilling to help a neighbor in need.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

People, being the intelligent, social mammals that we are, like to frame helping in terms of morality. But one species of ant appears to demonstrate “helping behavior without morality,” says Erik Frank, a biologist at the University of Würzburg in Germany. The Matabele ant tends to the wounds of nest mates. The only other animals that have been observed systematically treating others’ injuries are humans and some of our primate relatives. The finding informs a growing body of research aimed at fitting what we experience as moral sentiments into a larger pattern in nature. Frans de Waal, a primatologist at Emory University in Atlanta, points out that cleaning another’s injuries is a common practice among primates, and that the biological mechanisms that scientists associate with empathy in humans can be found in a variety of mammals, from chimps to prairie voles. Altruism, whether guided by principle or triggered by instinct, is even more widespread in nature, appearing in organisms as diverse as Seychelles warblers to cellular slime molds.

Can altruism exist without empathy? Lessons from the ant world

Named for a famed group of Bantu warriors, the Matabele ant is renowned as a fierce fighter. But the sub-Saharan termite-hunter also shows a caring side.

Researchers have found that Megaponera analis, as scientists call it, will tend to the wounds of nest-mates. The only other animals that have been observed systematically treating others’ injuries are humans and some of our primate relatives.

In other words, ants and humans share what biologists call a convergent trait: caring for another in need. The finding also informs a growing body of research aimed at fitting what we experience as moral sentiments into a larger pattern in nature.

That such precisely directed helping behavior, as it is known, pops up in as distant a relative as the ant belies some popular notions of Darwinian evolution, which characterize natural selection as promoting only selfish behavior. While it’s true that competition both among and within species plays a major role in shaping the evolution of biological traits, it’s not nature’s only driving force.

“I’m a biologist myself, but I’ve always hated the literature from the ’70s and ’80s on selfish genes and a dog-eat-dog world,” says Frans de Waal, a primatologist at Emory University in Atlanta who has written extensively on the evolution of morality among humans and other apes. “That’s a very dominant view.”

That view began to shift in the 1990s, as scientists began looking more closely at cooperative instincts, first in humans. “If you bring people together, the first thing they want to do is cooperate and be nice and harmonious,” says Dr. de Waal, the author of several books on morality and empathy in nonhuman animals. “Now we know from all sorts of studies, including my studies, that actually all of the mammals are a bit like that…. The first tendency is to help.”

Research reveals that a child as young as 14 months will, all else being equal, try to help a stranger correct a mistake, fetch an out-of reach object, or remove an obstacle. This kind of behavior exists in many other mammal species, even when there is no apparent reward: for instance, capuchin monkeys will rescue each other during intergroup battles, rats will free other rats from restrainers, and dolphins will help injured comrades stay afloat for air.

People, being the intelligent, social mammals that we are, like to frame helping in terms of morality. But ants appear to demonstrate “helping behavior without morality,” says Erik Frank, a biologist at the University of Würzburg in Germany who details the phenomenon in a paper published earlier this month in the Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

From an evolutionary point of view, “Morality evolved in us as a mechanism for helping behavior,” he says. “In the ants, it evolved through basic cues.”

When a termite soldier injures a Matabele ant, something that happens frequently during raids on mounds, the wounded ant releases a “help” pheromone that triggers ants nearby to come to her aid.

Injured ants are carried back to the nest, where other ants then “lick” the site of the injury with their mouth appendages, helping to ward off infection. Dr. Frank and his colleagues found that without treatment, 80 percent of injured ants died within 24 hours. Of those that received treatment, only 10 percent died.

“What’s interesting is how very simple rules and very simple cues can lead to these very complex behaviors in ants and in social insects in general,” says Frank.

Human beings do it differently. Instead of being obliged by pheromones, we are motivated by empathy, the ability to quickly and automatically represent in our own minds the mental state of another person. Evolutionary theorists see the emergence of empathy in humans and other animals as biology’s way of promoting altruism.

“We actually think that empathy in mammals started with maternal care,” says de Waal. But, he says “the whole system got co-opted in other relationships because obviously in our societies the mother-child relationship is not the only one we have.

“Empathy got extended, so to speak,” say de Waal.

De Waal points out that cleaning another’s injuries is a common practice among primates, and that the hormonal mechanisms that scientists associate with empathy in humans can be found in a variety of mammals, from chimps to prairie voles. Altruism, whether guided by principle or triggered by instinct, is even more widespread in nature appearing in organisms as diverse as Seychelles warblers to cellular slime molds.

That said, altruism is not always the same thing as pure selflessness. “This type of helping behavior could not have evolved – also our human one – if it wouldn’t have also benefited the actual helper,” says Frank. “No matter how indirect it might be.”

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

More than one way to prevent mass shootings

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By The Monitor's Editorial Board

The anger over the Feb. 14 school-shooting murders, especially among the students of Parkland, Fla., is directed mainly at elected officials and the legitimate cause of controlling access to guns, especially assault rifles. That debate should not be deflected or weakened. Yet at the same time, the United States can tackle the issue of whether better qualities of care in society – including the role of forgiveness – might help prevent a similar shooting. Perhaps one other lesson from this shooting could be that teachers need more support and resources in instilling good behavior as well as in correcting bad behavior. Schools must ensure teachers have the mental readiness to deal with the mental challenges from all students. As more schools adopt such an approach, the quality of care among those working with young people can help prevent school violence – even as legislators grapple with calls for more gun control.

More than one way to prevent mass shootings

After the 2015 shooting that killed nine people in a Charleston, S.C., church, many in the predominantly African-American congregation forgave the young white male gunman. In doing so, they hoped not only to heal the hatred they felt but the hatred in him that motivated the crime. In addition, they hoped their forgiveness might enable them to better reach others prone to violence and perhaps prevent a similar massacre.

In contrast, the killing of 17 people at the high school in Parkland, Fla., has yet to reveal much forgiveness toward the shooter. The anger over the murders, especially among Parkland students, is directed mainly at elected officials and the cause of controlling access to guns, especially assault rifles. That debate should not be deflected or weakened. Yet at the same time, the United States can tackle the issue of whether better qualities of care in society – including the role of forgiveness – might help prevent a similar shooting.

A good example of this approach is what came after the 2012 killing of 20 first-graders and six adults at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown, Conn. A special commission set up by the governor urged “adoption of a new model of care, one that emphasizes wellness while effectively and compassionately addressing illness; that places positive child development and healthy families front and center; and that breaks down existing silos to provide holistic and continuous care across the population.”

In addition to enacting stricter gun laws, Connecticut has raised the level of community care for young people. In many states, the events at Sandy Hook led to an increase in spending on mental health programs for all students.

The point is not to associate mass violence with mental illness. Such a stigma must be avoided, especially as those with emotional issues rarely resort to violence against others. Instead those dealing with young people – parents, teachers, coaches, school administrators, and others – should be encouraged and trained to assist all children in adopting habits of empathy, self-governance, and mastery over emotional vulnerabilities. The goal is to improve mental health for all so as to better deal with mental illness in the few.

Schools, for example, need to focus as much attention on each student’s qualities of character as they do on academics. They must question the widespread use of suspension and expulsion for what amounts to minor infractions. They must better coordinate with professional counselors, police, and state officials when handling kids who disrupt the school environment. And they must remove the stigma on students who seek care for personal problems.

In the case of the Parkland shooter, “We missed the signs,” Beam Furr, mayor of Broward County, told the Miami Herald. “We should have seen some of the signs.” The Florida Department of Children and Families, for example, found the young man to be a “low level of risk” in 2016.

Perhaps one lesson from this shooting could be that teachers need more support and resources in instilling good behavior as well as in correcting bad behavior. Schools must ensure teachers have the mental readiness to deal with the mental challenges from all students – rather than simply sending a child to the principal’s office or to the school psychologist. By that point, children will see themselves as tagged with “issues.”

The US has steadily improved support of character building in students. This struggle is not new. After one of the earliest cases of campus violence – the 1966 shootings by a student from a tower at the University of Texas – a special task force set the goal to provide care for all students, not just those in trouble. “We should not insist that a student has to be in difficulty to qualify for attention,” wrote the school regent, Rabbi Levi Olan.

As more schools adopt such an approach, the quality of care among those working with young people can help prevent school violence – even as legislators grapple with calls for more gun control.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

The fullness of God’s love, enough to meet our needs

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Jeannie Ferber

In today’s column, a woman shares how she prayed when her well was nearly empty – offering practical ideas for experiencing God’s inexhaustible goodness.

The fullness of God’s love, enough to meet our needs

News of rain in Cape Town earlier this month made my heart sing. As I read a BBC story about it, I was struck by the statement in the first sentence that the people rejoiced and thanked God (“Drought-hit Cape Town rejoices at rainfall,” Feb. 10, 2018). I understood what they felt, remembering well the drought New England experienced last year, though far less severe than the one South Africa is experiencing.

By summer’s end, our streams and ponds had dried up, endangering the wildlife, and people’s wells had begun to go dry. One day I turned on the faucet to find the water full of silt. According to news reports, this was a sign that a well was almost dry.

I had been praying daily about the drought, but not in the sense that “if I prayed enough” my prayers might change the weather. Rather, Christian Science has shown me that prayer is God-impelled, a result of divine influence: God lifting our thought above material impressions, enabling us to see beyond the material picture to something more – His present, spiritual creation. Despite appearances to the contrary, this spiritual reality makes all the difference in our experience when we understand its substance. For example, a number is an idea. You write down a figure, or see it on a computer screen, but that doesn’t make a number material. Its substance is still the idea behind what you’re seeing.

Similarly, through prayer, God has given us the capacity to know and understand the whole of His creation – including ourselves – as His spiritual ideas, governed by divine Mind (another name for God). It was Christ Jesus’ understanding of creation as wholly spiritual and good that enabled him to heal. He understood God’s spiritual ideas as having actual substance and life, as the present reality of being, despite the material senses’ inability to see this. What Jesus knew, our thought awakens to each time we pray and turn trustingly to God for help. And while a limited material sense of things can’t conceive of creation as spiritual, that can’t keep God from manifesting His goodness practically.

One day when it finally became impossible to bathe or drink the water, I determined not to go to bed that night until what was causing my fear was healed. At its root, it was not really the prospect of a dry well that was causing the fear, but the awful feeling that we’re dependent on material conditions, rather than God, for our well-being. To heal that fear, I needed a better understanding of God, which I knew prayer and Bible study would give me, as the Bible is the story of God’s endless love and care for us.

That night, humble and persistent prayer brought inspiration and even joy. I began to feel more convinced of the realness of God’s love than concerned about the material conditions. I opened to these words in the Christian Science textbook, “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures” by Monitor founder Mary Baker Eddy: “Creation is ever appearing, and must ever continue to appear from the nature of its inexhaustible source” (p. 507). Suddenly, not only was this passage comforting, but it made sense. Because God is Spirit – that is, infinite – there can never be a point when God’s love or care runs out. Joyfully, I was able to accept the fact that God is the inexhaustible source of good, which no apparent material conditions can limit.

The next day, even though there had been no rain, my husband felt compelled to check our well. When he did, the water level was just below the top. In a few days all the silt was gone. Neither our well nor our neighbors’ ran dry before rains came several weeks later.

Despite all that seems to defy the presence of God, when we turn to Him with all our heart, we can prove our inseparability from His infinite goodness. The fullness of God’s love is just that: full.

A message of love

A New Delhi oasis

A look ahead

Thanks so much for spending time with us. Come back tomorrow. We're working on a story about how to preserve a shared sense of truth when technology is making facts indistinguishable from propaganda.