- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Monitor Daily Intro for March 7, 2018

Hark back to the era that produced International Women’s Day, which the world observes tomorrow, and you’ll hear familiar echoes.

For one thing, women were on the march. Some 15,000 rallied in New York in 1908 for shorter work hours, better pay – and the vote. By 1911, International Women’s Day was born with celebrations in Europe. By 1917, March 8 was its birthday, marking the day Russian women went on a wartime strike for bread, peace – and the vote.

Fast forward a century. In many countries, women are reminding leaders they can deploy that very hard-won vote as they once again fill the streets, last year and this, over issues like pay, gender-based harassment and violence, and equal rights.

That’s what spurred our series, “Reaching for Equity,” which concludes today. In their reporting, our correspondents found controversial initiatives – using quotas in politics – and some counterproductive ones: turning too much of a Western lens on how to move forward. But they also surfaced a common thread: The growing refusal to settle for “we’ll get to that later,” or to remain silent about offensive or criminal behavior.

And there’s a common tone: optimism. That's seen in this year’s theme, #pressforprogress, which is grounded in the overwhelming evidence that when women do well, the world does well.

Now to our five stories, including some that show how a collective sense of good and a willingness to abandon entrenched assumptions strengthens resilience and fosters progress.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

After tax-cut love, business and Trump clash on trade

The resignation of Gary Cohn, President Trump's economic adviser, shook markets already on edge over the sudden prospect of tariffs. The jumpiness underscored Wall Street's distaste for anything that might be seen as brinkmanship.

-

Laurent Belsie Staff writer

Ed Yardeni is an economist and investment strategist who understands very well why Wall Street got rattled overnight due to the departure of Gary Cohn as President Trump’s top economic adviser. The concern, Mr. Yardeni says, is that “there will be less of a voice for free markets and free trade.” For now global investors and corporations are feeling concern rather than panic. Many agree with Mr. Trump that US firms are victims of unfair trade practices. But their instincts are toward caution and multilateral engagement, whereas Trump’s “Art of the Deal” includes provocation as a path toward victory. Trump raises the risk of an economy-damaging trade war if his moves prompt retaliation and rising protectionism. Businesses don’t like the uncertainty. And although they scored a win with Trump on tax cuts, they now feel a bit out in the cold. They saw Mr. Cohn as an ally, and his resignation came after he failed to steer the president away from a major confrontation with trading partners over steel and aluminum. Tariffs appear to be on the way.

After tax-cut love, business and Trump clash on trade

The departure of President Trump’s chief economic adviser Tuesday sent the after-hours stock market plunging, rattled foreign capitals, and raised the risk that the United States, after 70 years of cheerleading free trade, is turning its back on the idea.

Until now, nations and companies have brushed aside the president’s support of aggressive trade barriers, reasoning that business-minded advisers would moderate any harsh moves by a divided administration. That changed with the resignation of Gary Cohn, the highest-ranking free-trader inside the White House.

No one can avoid Mr. Trump’s tough trade talk anymore. It now seems a given that he will announce broad tariffs against imported steel and aluminum. And given the reaction from trading partners, it also appears likely they will retaliate with similarly sized tariffs against US goods.

The big question is what happens after that. So far, the market reaction reflects a sense of heightened risk, rather than panic. And many CEOs don’t disagree with Trump that foreign trade partners often take advantage of America. But where Trump sees provocation as a tool toward fairer trade, corporate America sees uncertainty and hazard. Whether it’s a Republican or Democrat in the White House, businesses often prefer caution and global engagement to brinkmanship when it comes to trade.

“The fact that you can paint so many scenarios is not a positive thing,” says Mark Zandi, chief economist of Moody's Analytics, a risk-management subsidiary of Moody’s Corp. in New York. “Business people get awfully nervous when they don’t know the rules of the game and how those rules may change. Investors, the same way.”

Gains from tax cuts 'could be erased'

On Wednesday, the Dow Jones Industrial Average seesawed dramatically before closing down 0.33 percent, following a down day in Asia but a rise in several European markets.

Some specific companies and labor unions have cheered Trump’s willingness to pressure trade partners by putting up tariffs and other trade barriers.

But the US Chamber Commerce warned in January against letting the North American Free Trade Agreement fall apart, let alone risking a wider trade war.

“The economic gains we’re seeing from regulatory relief and tax reform could be erased if we do not stand up for and protect free, fair, and reciprocal trade around the world,” Thomas Donohue, the Chamber president, said in a statement after Trump’s State of the Union address. “It’s clear that if the US isn’t leading on trade, we’re falling behind.”

A question is whether Trump accepts that notion, and whether any advisers can sell him on it. In the 1990s, Wall Street types like Robert Rubin and Lawrence Summers had President Bill Clinton’s ear, sometimes to the consternation of organized labor. More recently, George W. Bush surrounded himself with former Fortune 500 CEOs, and President Barack Obama leaned on Mr. Summers and others who were more globalist than America-first in mind-set.

Now, with Cohn departing, Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin (like Cohn a Goldman Sachs alum) remains as a prominent Trump official who is more attuned to concerns of Wall Street and corporate boardrooms.

Trump himself, though a New York business person, seems closely aligned with the get-tough trade views of other advisers including Peter Navarro on the White House staff, US Trade Representative Robert Lighthizer, and Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross.

If multinational firms have scored wins with Trump on tax cuts and deregulation, the trade issue is turning into a trouble spot, or at least a wild card. Many CEOs are aware of history, that a trade battle can as easily turn into an era of protectionism as a quick victory.

“Businesses by the nature of them tend to be multilateral” in outlook, says Ed Yardeni, who heads an investment strategy firm near New York. “They have interests all around the world and have to deal with politicians all around the world.”

Private sector wondering, which scenario?

Traders and foreign policymakers are looking at three possible scenarios:

- Trump backs down from broad-based tariffs on steel and aluminum and, instead, targets them at China and other nations that are helping it dump steel. This is the least disruptive scenario, because it lessens the risk of an all-out trade war, but it is also highly unlikely, analysts say.

- The president follows through on broad-based tariffs and affected nations either don’t respond or retaliate with similar-sized tariffs on US goods. Either way, the White House declares victory and the dispute doesn’t widen. Analysts say that relative to the size of the economies of the nations involved, it would have only a small economic impact. The steel and aluminum tariffs would cost other nations $14.2 billion per year in trade losses, with Canada ($3.2 billion) and the European Union ($2.6 billion) feeling the biggest pinch, according to Chad Bown, a senior fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics. That’s a drop in the bucket for them. If all the affected nations retaliate proportionally, hitting, say, blue jeans or agricultural products, the net job loss in the US could be 100,000 to 150,000 jobs, estimates Mr. Zandi. In an economy used to creating 200,000 jobs in a month, such losses are manageable, he added, speaking on a conference call with reporters Wednesday.

- The trade dispute over steel and aluminum escalates into a full-blown trade war. This is the big risk, and it could happen, for example, if Trump responds to European Union tariffs with new tariffs on cars. Even if he doesn’t, some analysts and, increasingly, corporations and investors, worry that this is just the first step toward a much more protectionist stance by the US and possibly other nations. That could involve much larger losses of sales and jobs for economies around the world.

The most likely scenario, according to many analysts, is some version of No. 2, although Trump isn’t likely to stop pushing on trade.

“I think he's going to push forward on trying to get fairer deals,” says Mr. Yardeni, an economist. “He's not wrong about foreigners taking advantage of us. The question is whether these violations are significant enough to warrant risking a trade war.”

The president himself has played down those risks. Last week, he tweeted: “When a country (USA) is losing many billions of dollars on trade with virtually every country it does business with, trade wars are good, and easy to win.”

What might be stoking his confidence?

For one thing, the stakes in the current dispute are relatively small: both in terms of trade and jobs. The economy won’t come to a sudden halt over steel and aluminum tariffs.

Less to lose in a trade war, but

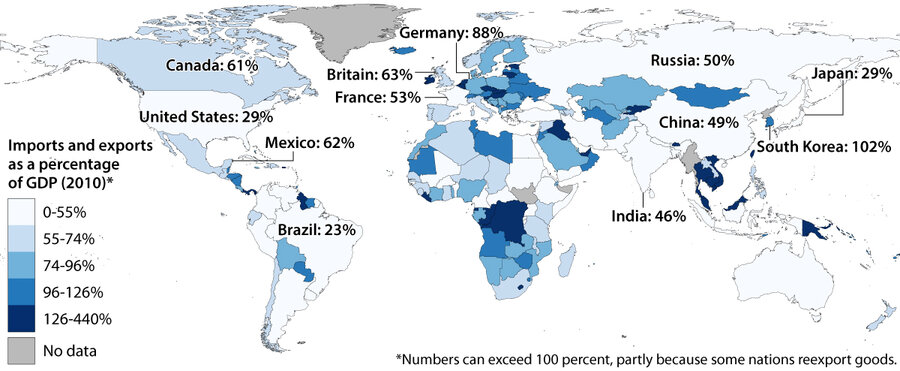

For another, the US has less to lose in a trade war. Of all the major trading nations, the US economy is one of the least reliant on foreign trade. Imports and exports make up only 29 percent of its GDP, only slightly higher than Brazil and similar to Japan, according to 2010 data compiled by the St. Louis Federal Reserve Bank. Almost every other major power is much more reliant on trade, including all of Europe, Canada, Mexico, China, Russia, and South Korea.

The administration may be gambling that those nations will come to terms on trade because they have more to lose.

“When Trump says trade wars are easy to win, he's basically flexing his muscle,” says Yardeni. He may now be staking out aggressive positions for negotiations to come.

But nations don’t always behave rationally.

“Things unravel,” says Zandi of Moody's Analytics. “There are political dynamics involved. We went down this path in the early '30s with Smoot-Hawley [the tariff act endorsed by President Herbert Hoover] and it didn’t work very well for anybody. Hopefully, we’ve learned that historical lesson.”

Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis

Share this article

Link copied.

Reaching for equity

Bull by the horns: Teaching men how to treat women better

Can you really uproot entrenched behavior? Numerous programs target men who routinely interact disrespectfully or violently with women. They've found the most promising starting point is willingness to admit they can change – and that life will be better if they do.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 11 Min. )

-

Ryan Lenora Brown Staff writer

-

Jessica Mendoza Staff writer

-

Michael Holtz Staff writer

-

Whitney Eulich Correspondent

Women around the world have been finding their voice in recent months, accusing men – generally, powerful men – of sexual harassment ranging from knee fondling to rape. High-profile cases have made men more aware of the scale of the problem, and programs are popping up in many countries to help those suffering from “toxic masculinity.” In South Africa, men attend workshops to try to change the way they interact with the women in their lives – amid a community where sexual assault and domestic violence are an open secret. In Mill Valley, Calif., a production company is moving beyond corporate sexual harassment training videos that do no more than provide legal cover, and instead creating videos that reflect real-life situations women face at work. Activists in Japan are working to highlight the problem of men groping women and girls on crowded trains – using attention-grabbing badges and colorful cartoons for potential victims to wear. And in Mexico City, men struggle to rein in the violent side of Latin America’s machismo culture, which has resulted in the region being among the deadliest for women.

Bull by the horns: Teaching men how to treat women better

Women around the world have been finding their voice in recent months, accusing men – generally powerful men – of sexual harassment ranging from knee fondling to rape. High profile cases have made men more aware of the scale of the problem, and programs are popping up in many countries to help those suffering from “toxic masculinity.”

In this article, Monitor correspondents look at all kinds of ways of teaching men how to treat women with respect and redress the gender power imbalance, from anger management classes in Mexico to lapel badges on Japanese schoolgirls’ coats.

-Peter Ford

SOSHANGUVE, SOUTH AFRICA - On a recent summer morning, in the courtyard of a squat brick house in this township outside Pretoria, Tumelo Mabena leans over a white board and scrawls a short phrase in block letters.

ACT LIKE A MAN.

He taps his pen against the board. “What do you think when you hear these words?” he asks the group of about 15 men slumped in plastic chairs in front of him.

“It’s something that when a woman says it, you feel offended,” pipes up one man. “It means you’re showing too much emotion.”

“It means you must be man enough to kill a snake if a woman asks you to do it,” offers another, and the group explodes in laughter.

Mr. Mabena cracks a smile too. “We are laughing, but this is what we are here to talk about, in a serious way,” he says.

It’s the first day of a five-day training he conducts regularly in Soshanguve, a low-slung, sandy township, for men trying to change the way they interact with the women in their lives. Some are estranged from their families. Many have children they rarely see. And others simply want to control their anger.

The idea, says Pule Goqo, who manages the Soshanguve workshops, is to get men talking among themselves about one of the community’s most poisonous open secrets – sexual assault and domestic violence.

“All your life, you hear couples fighting next door, the woman screaming, and you see no one do anything about it,” Mr. Goqo says. “So you think that is normal life.”

This is true across South Africa. In Diepsloot, a township about 40 miles away, over half of men questioned in a recent survey admitted to having been physically or sexually violent with women in the previous year.

That violence has historical roots. For black men belittled daily by the apartheid system, control over their wives was often the last remaining shred of power they had.

Today it is unemployment that emasculates many men. “Guys feel helpless when they have to ask their wives or girlfriends for money,” says Mabena.

The men who come to his workshops realize that violence is destructive in their lives, and they’re looking for a way out, he adds.

He knows the story well: as a boy he often hid while his father beat his mother, and when he began dating himself, “I had a lot of anger. I would beat the girls whenever we would fight.” And sex came by force too. “When I wanted it, I took it,” he says. “I didn’t ask.”

Then he became a father, and around the same time he met Mr. Goqo, who began inviting him to Sunday breakfast and taking him to church with his family. For the first time, Mabena says, he saw an example of a man who was powerful in a very different way than the men he had known growing up.

It was not long before he was leading the workshops himself, speaking to other men about the importance of setting new examples of masculinity in the township.

Back in the courtyard in Soshanguve, he’s asking the men to think about who their role models are and why.

“My mother, because she was there for me even when I was in jail,” mumbles one man.

“My gogo,” says a second, using a local word for grandmother. “She raised me up right.”

Mabena nods. “Why do you think we have so few men to look up to?” he asks. The men chime in again – their dads weren’t around, they beat their mothers, they drank and didn’t work.

“But that can change with us,” he says. Slowly, like they only half believe it themselves, the men around him begin to nod.

-Ryan Lenora Brown

* * *

Life in an American corporate office is rarely as violent as it is in a South African township. But sexual harassment is aggressive too, and nearly two thirds of US women say they suffer from it in their workplace. The standard tool to reduce offensive male behavior is a training video; does that work?

MILL VALLEY, Calif. - At first glance, Janet Conley looks more like an accountant than a crusader. Her mild manner and sweater-and-slacks ensemble seem better suited to crunching numbers in her climate-controlled office here than dealing with the murky business of sexual harassment in the workplace.

But that’s what she does, writing scripts for videos meant to train employees to recognize and combat sexual harassment. Her goal: to craft stories that reflect real-life situations women face at work, and show clients of all genders how to put an end to bad behavior.

“Hopefully we can create some empathy – or at least make the point [that] this is not OK, and there will be consequences,” Ms. Conley says.

For decades, this sort of video has been standard fare at US firms; managers require their employees to watch them on the assumption that they explain what constitutes harassment – and that men will behave better towards women when they understand that.

But recent revelations of sexual harassment, assault, and abuse in workplaces across America have made it clear that this is not really happening. Around 60 percent of women still say they experience sexual harassment in the workplace, according to a 2016 report by the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC).

One big problem with sexual harassment training is that much of it was not designed principally to prevent harassment; it was mainly meant to protect companies from legal liability. Since the Supreme Court ruled in 1998 that a firm could avoid responsibility in a sexual harassment suit if it had put anti-harassment policies in place, boilerplate training videos have boomed.

“Most [companies] have installed training and grievance procedures and called it a day,” sociologists Frank Dobbin and Alexandra Kalev wrote in the Harvard Business Review. “They’re satisfied as long as the courts are. They don’t bother to ask themselves whether the programs work.”

Conley and her colleagues at Kantola Productions are well aware of the bad rap surrounding training videos. “You hear people complain about harassment training and ‘Ah, it’s hokey,’ ” says Steve Kantola, who founded the firm in 1985. “But it doesn't have to be that way.”

His aim, he says, is to produce thoughtful, high-quality videos that draw on real-life situations. Each module takes about a year to produce. And he hires legal experts and researchers to keep him up-to-date on the latest laws and studies about what makes anti-harassment training effective.

The company’s latest project, for example, encourages bystanders to intervene if they witness incidents of sexual harassment, and suggests things that employees can actually say.

“We don't want to put the pressure only on the victim,” Conley explains. “If you’re comfortable speaking up, you have every right to speak up and say something. It’s about building a sense of obligation.”

“We have seen progress,” says Conley, who recalls a time when pin-up photos of naked women hung on the walls of auto repair shops. “But this goes to pretty deep human nature, so it’s going to take time. We just have to keep working at it.”

-Jessica Mendoza

* * *

In few parts of the world do men pride themselves on their authority over women as strongly as they do in Japan. That sometimes manifests itself in grotesque ways. But schoolgirls are fighting back.

TOKYO - In much of East Asia, even talking in public about such a taboo subject as sexual assault has long seemed an impossible task. But that appears to be changing as more and more women speak out against the region’s deep-seated misogyny.

Take the “Groping Prevention Activities Center” for example. Launched in 2016 by Yayoi Matsunaga, a freelance journalist in Osaka, Japan, its mission is to help protect women from chikan, a Japanese term denoting the notorious bane that is men groping women and girls on crowded trains.

Ms. Matsunaga got the idea for the center after she heard about one of her friends’ daughters who had been regularly groped on her journey to and from school. To ward off aggressors the girl had made a card that she attached to her bag by a string. “GROPING IS A CRIME” it read. “I WONT BEAR IT SILENTLY.”

The label worked, but it made the girl feel self-conscious because no one else had one. That’s when Matsunaga stepped in. She launched a crowdfunding campaign to pay for thousands of attention-grabbing badges with similar warnings and colorful cartoons. The campaign raised more than $19,000 in three months and now the badges are available in shops near metro stations in Osaka and Tokyo.

“I believed it was wrong to let my friend’s daughter fight all by herself,” Matsunaga says. “I wanted more people to become aware of the problem.”

She has succeeded. Last year, her center held a competition to design a new badge. It drew more 1,300 entries from over 250 schools and universities and sparked a public debate about the prevalence of groping and sexual assault. The winning design features a drawing of a girl with pink hair holding a pair of gold handcuffs in front of her eyes as if they were glasses.

On a crowded shopping street in the Harajuku neighborhood of Tokyo, one of the city’s most popular destinations for young people, dozens of Matsunaga’s pins hang from the sides of souvenir stalls. Each one sells for about $5 and comes with a brochure with information about the center and police statistics about groping: 73 percent of victims are in their teens or 20s, 54 percent incidents happen on trains, and 30 percent of those incidents occur during the morning rush hour.

Aoi Osawa, a 14-year-old girl with braces and her hair pulled back in a ponytail, studies the badges warily. She says she would buy one if one of her friends did too, but she doesn’t want to be the first. She likes the idea of the badges; she’s just skeptical of how much difference wearing one would make.

“Most of my friends say they’ve been groped on the train,” Aoi says. “It’s a big problem in Japan. I’m really not sure what it would take to change men’s attitudes.”

-Michael Holtz

* * *

‘Machismo’ – it’s a Latin American word that has entered the global vocabulary, but at home it has an especially lethal meaning: Latin America is the most dangerous continent in the world to be a woman. In Mexico, a non-profit is trying to change that culture, man by individual man.

MEXICO CITY - On a chilly Tuesday evening in Mexico City, sixteen men trickle into a beige-and-mint colored meeting room. They sit down in a circle of folding plastic chairs, sharing hushed “hellos” and shy “how are yous” and wait for the clock to strike seven.

They are a mixed crowd: one man with silver hair and impeccably shined dress shoes sits across from another with paint-stained fingers and a knit hat. But they’re all here for the same reason. These men have treated their partners or spouses violently, and they want to change.

Latin America has a deadly and deserved reputation for violence against women and machismo. Seven of the ten countries in the world with the highest female murder rates are in Latin America, according to a recent international report. (Mexico ranks sixth.)

Gendes, the nongovernmental organization organizing tonight’s meeting, is working to tackle cultural attitudes towards masculinity, power, violence, and authority. At tonight’s meeting, participants will grapple with those issues up-close and personal.

Unlike the US, courts in Mexico don’t send men to therapy like this after committing acts of violence. Each man turned out tonight of his own will. Most have heard about Gendes from the women’s group to which their partner had turned for help.

The participants go around the room introducing themselves and confessing to an act of violence that they’ve committed this week. Intimacy is a key part of the program, explains Iván Salazar Mediola, who runs the counseling program known as Men Working (on themselves).

The men scooch their chairs together into pairs and read out pledges. “I promise to be intimate and not violent,” says one. Looking him in the eye his partner responds, “I can help you.”

Carlos is attending his second session today. He learned about Gendes from a friend at work who was worried about the increasingly heated conflicts Carlos was having with his girlfriend.

“She’s obsessed with Facebook and social media,” Carlos says. “I let my mind run wild about what she could possibly be doing on there all the time.”

He has threatened her and verbally abused her, he admits. “I’ve felt jealousy before, in past relationships,” he says. “But it’s never been like this.” So he joined this group to regain control of his emotions.

“I want to find a way to not let my anger take over,” he says.

As the two-hour session progresses, the men work their way through the coursebook, taking it in turns to read out definitions of issues such as authority or frustration, and then applying the vocabulary to their act of violence that week.

Next, one participant walks the group through his violent act from start to finish. The rest of the men listen, helping him decipher what set him off, what his reaction stemmed from, and who had been affected by the violent altercation.

Jose has been coming to these sessions for more than a year; recently he was asked to repeat the first part of the two-part course after “committing a very violent act,” he says.

“I’ve exploded violently toward so many people in my life. I grew up around violence and learned it as an effective way to express myself. I realized I needed to change for my own physical and mental health,” he explains.

“For me, this is about getting more tools to deal with a violent past and the way I feel or become when I’m overwhelmed by anger.”

Mexico and 16 other Latin American and Caribbean countries have passed laws recently to punish femicide more heavily than other murders. But sloppy police work and sexism mean few of these crimes have been punished, according to a report last year by UN Women.

“We still live in a world driven by a culture of violence,” says Salazar. “It’s not just about a new law or political proposal, but a cultural change with tangible results. That takes time and hard work.”

-Whitney Eulich

Guns, patriotism, and few shootings. Do Swiss offer a model?

Lots of guns, very little violence: That's the Swiss experience. But understanding why that's the case involves recognizing a deeply rooted social compact that values the collective good.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

Switzerland has more guns circulating per capita than any country besides the United States and Yemen. But the Swiss historic relationship to their arms as members of a standing militia, their motives for keeping them, and the regulations around them diverge from the American experience. It’s one reason the liberal circulation of arms here is not accompanied by a scourge of gun violence. Conscription is mandatory for Swiss males, and citizen soldiers store their weapons at home. Army-issued ammunition cannot be kept at home. A gun under the bed for self-protection? Impossible in Switzerland. The militia, and the culture it has fostered, is seen as part of the common good, binding a nation together in a mission of national security. That differs widely from America’s individualistic gun culture. Today, many feel satisfied with where Switzerland is on gun control. “Swiss laws give freedom to the citizen,” says Luca Filippini, president of the Swiss Shooting Sports Association, “but at the same time they attempt to reduce abuse with guns.”

Guns, patriotism, and few shootings. Do Swiss offer a model?

Marksmen fill the recreation hall of this sand-colored shooting club in the wooded hills outside Bern, capping off a weekend competition to commemorate the 1798 Battle of Grauholz in the French Revolutionary Wars.

There is no shortage of patriotism here – there is even a yodeling club dressed in traditional red-trimmed black felt jackets – and indeed, for many Swiss citizens, guns are as central to their identity as the Alps. Switzerland has one of the highest per capita rates of guns in the world. “Every Swiss village has a range just like this one,” says Renato Steffen, a top official of the Swiss Shooting Sports Association, representing the group at the event. The association counts 2,800 such clubs across the country, with a youth wing for children as young as 10.

If this seems like a scene that belongs in gun-loving America, there the similarities end. The Swiss’s historic relationship to their arms as members of a standing militia, their motives for keeping them, and the regulations around them diverge from the American experience. It’s one reason that the prevalence of arms here is not accompanied by a scourge of gun violence.

Yet Switzerland does provide clues for gun ownership in America. Here divisions also have emerged after gun tragedies and efforts to rein in use – and the story is not settled as a new gun-control directive comes from the European Union. But ultimately the two sides have found consensus, getting beyond polarization that paralyzes the American debate even after such tragedies as the school shooting in Parkland, Fla. Those who loathe guns here accept their deep-seated position in Swiss tradition as they push for more controls, while gun advocates have pushed back but ultimately accepted more rules and oversight in the past 15 years.

“We can live with the restrictions placed on us until now,” says Kaspar Jaun, president of the Battle of Grauholz association, before hurrying off to prepare for the awards ceremony for best marksman.

‘Sport and protection of country only’

There is no official count of guns in Switzerland. But according to the Geneva-based Small Arms Survey, Switzerland has more guns circulating per capita than any country besides the US and Yemen. The most recent government figures estimate about 2 million firearms in Swiss households. Conscription is mandatory for Swiss males, and citizen soldiers store their weapons at home, making up the bulk of guns in households today.

The militia, and the culture it has fostered, is seen as part of the common good, binding a nation together in a mission of national security. That differs widely from America’s individualistic gun culture. According to a Pew poll in 2017, 67 percent of those who own guns in the US cite their personal protection as a major motive.

And differences with the US don’t end at cultural ones. In Switzerland, regulations have become much more stringent since the free-wheeling days before a Weapons Act was put into place in 1999. And they have steadily tightened over the past 15 years. Military guns, once given to members after their service and passed down for generations, can now only be acquired after service with a firearms acquisition license. Since 2007, army-issued ammunition cannot be kept at home. A gun under the bed for self-protection? Impossible in Switzerland.

Loaded guns, whether military or for sport, cannot be carried on the streets here without a special permit which is rarely issued. Because of conscription, the Swiss are highly trained in weapons handling and storage. As he drives away from the shooting range Sunday, Mr. Steffen says he would never want the right to transport his army rifle loaded. “No, no,” he says, “that is crazy. For us, guns are for sport, and protection of our country, only.”

Switzerland does grapple with gun death rates higher than European neighbors, the vast majority of it suicide. Guns also play a troubling role in domestic disputes. But unlike the US, gun deaths out of self-defense are a rare phenomenon. Criminologist Martin Killias, at the University of St. Gallen's law school, built a database looking at homicides committed in self-defense over a 25-year period ending in 2014. Of 1,464 homicides, in 23 cases defenders killed victims in self-defense or under duress. In 15 of those cases, a firearm was used, nine of which were the weapons of on-duty police officers.

The homicide rate in the US is about six times that of the Swiss national average. But when comparing domestic violence that ends in death with a firearm, the ratio is just under 2 to 1, a much smaller gap of gun deaths between American and Swiss households. “It is very illustrative,” Mr. Killias says. “It’s not so much that American people are more aggressive, or Swiss are so terribly more peaceful, it’s simply that gun use in the street [in the US] is quite common,” he says. “That is why robbery quite often ends with a shooting in America, whereas in Switzerland it is practically never the case.”

Switzerland's gun debates

Nonetheless, the debate has still been divisive and bitter here. Josef Lang sits on the opposite end of the spectrum as men such as Steffen, and still receives hateful threats and messages over his role in the gun control movement in Switzerland.

A pacifist activist since the 1980s, Mr. Lang was a parliamentarian in 2001 in the canton of Zug when a gunman stormed the chamber. He ducked underneath the desk in time and survived, but nearly 20 years later he recounts vividly every second of the 2.5 minutes gun spree during which 14 of his colleagues around him were killed. He remembers the feeling of a bullet grazing his bushy hair.

With each incident, laws have tightened to get rid of loopholes. After the Zug massacre, gun control advocates pushed for cantonal police registries to be linked and for tighter controls for private gun sales. In 2006, after Swiss alpine skier Corinne Rey-Bellet and her brother were killed by Corinne's estranged husband with his military rifle, rules banning the storage of military ammunition at home were created. Today, military members can choose to also keep their weapons at a central arsenal.

The battle hasn’t always favored gun control. In a 2011 referendum voters would have, among other things, required military arms to be stored in a central arsenal. Fifty-six percent voted against it. Today, many feel satisfied with where Switzerland is on gun control. "Swiss laws give freedom to the citizen but at the same time they attempt to reduce abuse with guns,” says Luca Filippini, the president of the Swiss Shooting Sports Association.

Switzerland’s reform history provides a lesson for the US, argues Erin Zimmerman, an American living in Switzerland who is a former US police officer and gun owner. While the country is vastly different from the US in demographics and population, she believes it shows the possibility of consensus for sensible gun regulations.

To underline the point, a nongovernmental organization she belongs to, Action Together: Zurich, led a fundraiser for the US-based nonprofit Everytown for Gun Safety, timed to a visit to Zurich this week by former White House strategist Steve Bannon, who has resisted gun-reform efforts in the US.

While some US states have been able to pass gun reform, she says Americans in the national debate are too often only presented with “zero-sum” options. They are cast as simply pro- or anti-gun, making middle ground choices more elusive. “Switzerland has done a really good job of modeling that,” she says.

Creeping ‘Americanization’?

Now, however, the battle is heating up once more in Switzerland – and some worry about the creep of “American” mentalities. In response to the wave of terrorist attacks in Europe starting in 2015, the EU has imposed tighter gun restrictions. While Switzerland is not part of the bloc, it does belong to the passport-free Schengen area and so must adhere to EU rules.

Mr. Filippini argues the rules won't have any bearing on terrorism, which is committed by criminals using illegal weapons and methods such as trucks. Gun advocates have promised to fight it in a referendum if it’s adopted into Swiss law and in general worry this is just the beginning of interference from the outside into their gun rules.

Both sides are staking their positions as gun-owning households in Switzerland has waned, in large part because the Swiss military has reduced its size by about sixfold since the 1990s. Today, 22 percent of households say they own guns, compared to 35 percent 15 years ago. Still, Lang worries about language he hears from the hard-line gun lobby about “self-protection,” against refugees and migrants or cuts in police budgets, a concept that is largely a taboo in Swiss society. Lang calls this the “Americanization” of the Swiss mentality.

That trend is something that would be deeply unsettling to most Swiss. When it comes to guns, many sit somewhere in the middle, like Chris Völkle, who works in sales in Bern. The gun in his home would be counted in the surveys that put Switzerland at the top of global gun ownership. Having finished his military training in 2016, he still must practice shooting annually, so he keeps it at home for convenience. But following strict guidelines, the rifle is in the cellar, the firing pin is in the cupboard, and the ammunition is at a military facility. “I don’t look at it like a gun,” he says. “It’s like a long, heavy piece of metal. It’s useless.”

Mr. Völkle says he accepts the status quo here because there haven’t been widespread gun problems in his country, unlike the wrenching violence the US is living through. After Parkland, Fla., he once again looked across the Atlantic in bewilderment.

“Mostly it’s just baffling to us that nothing gets changed after something like this happens,” Völkle says. “I assure you if more people died it would very, very quickly change, and you would not be able to keep your gun at home anymore.”

How Tunisia's Sufis have withstood hard-line Islamist attack

What makes a society resilient? In Tunisia, a powerful sense of national identity has made it much more difficult for outside religious extremism to take root.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

-

By Taylor Luck Correspondent

In a bid for influence following the Arab Spring revolutions, Salafist Muslims whose puritanical strand of Islam originated in Saudi Arabia have waged an aggressive campaign across the Arab world. Seeing Sufism as an obstacle to spreading their hard-line interpretation of Islam, Salafists have systematically demolished Sufi shrines, attacked Sufi clerics, and killed Sufi prayer-goers in Egypt, Syria, and Libya. In parts of the Arab world, the voices of Salafists have become so prominent that many Sufi movements and gatherings have adopted lower profiles to prevent attacks. But in Tunisia, residents say, the Salafists miscalculated, vastly underestimating how deeply embedded the mystic and more moderate Sufism is in the country’s collective identity. Across Tunisia, neighborhoods and towns are named after Sufi saints, and most Tunisian families can trace their lineage to a Sufi saint or holy person. “Before there was a Tunisian state, there was Sufism,” says a retired engineer leaving a morning recitation at a shrine in Tunis. “We love God and we love our heritage,” says a prayer-goer at another Tunis shrine. “For some of us this is all we have. No extremist can take this away from us.”

How Tunisia's Sufis have withstood hard-line Islamist attack

“La ilaha ill-Allah, La ilaha ill-Allah,” the men, young and old, chant as they rock rhythmically, pressing wooden prayer beads through their hands.

“La ilaha ill-Allah” – There is no God but God – they repeat, every syllable rolling into the next without breath, a never-ending song of faith.

Minutes go by, hours. Such recitations, a pillar of Sufism, are reserved by some communities for special holidays but are part of the weekly, and at times daily, routine here in Tunisia.

Yet in Tunisia, a 1,000-year-old tradition of mystic Sufi orders has been under pressure by a campaign of threats, slander, and vandalism from hard-line Salafist groups seeking to take over mosques and communities since the country’s 2011 revolution.

Salafism, a strict puritanical strand of Islam originating from Saudi Arabia, rejects Sufis for their reverence for holy men and for their worldly search for divine truth in life. They see them as an obstacle to spreading their hard-line interpretation of Islam to parts of North Africa, Asia, and Europe.

In a bid for influence following Arab Spring revolutions, Gulf-backed Salafis and Salafi-inspired groups such as the so-called Islamic State (ISIS) systematically demolished Sufi shrines, kidnapped and assassinated Sufi clerics, and killed Sufi prayer-goers in Egypt, Syria, and Libya.

In parts of the Arab world, Salafis’ voices have become so prominent, many Sufi movements and gatherings have adopted lower profiles to prevent attacks.

But in Tunisia, residents say, the Salafis have failed. They miscalculated, vastly underestimating Tunisians’ historical and generational connection to Sufism. Across the country, neighborhoods and towns are named after Sufi saints, and most Tunisian families can trace their lineage to a Sufi saint or holy person.

“We love God and we love our heritage,” says Mohammed, who is unemployed, after completing a Sufi recitation at the Sidi Ibrahim Riahi shrine in Tunis. “For some of us this is all we have. No extremist can take this away from us.”

Spiritual battleground

It was only natural that Tunisia, the lone success story from the Arab Spring, become a battleground between Gulf-backed Salafism and local Sufism. After toppling longtime dictator Zine el-Abidine Ben Ali, Tunisia established a modern democratic constitution guaranteeing human rights and a level of personal freedoms and transparency far exceeding other states in the region.

Taking advantage of the weakened state right after the revolution, between 2011 and 2013, hardline Salafis took control of most of the mosques in Tunisia. Salafist groups and supporters burned or desecrated 40 Sufi shrines and tombs. Hardline Islamists made inroads in marginalized communities by offering money to open small businesses, cover rent, or pay for weddings.

In many Arab states, Salafis have succeeded in spreading their influence, inciting the destruction of hundreds of Sufi shrines and tombs with little public outcry.

In Libya, Salafist Madkhalis used armed vice squads and alliances with warlords. In Egypt, Salafis are represented in parliament by a political party and their views are broadcast almost 24 hours a day on satellite networks and the radio. In Syria, Sufis have come under pressure from both Salafist groups and jihadists such as Al Qaeda and its various affiliates and ISIS.

But today Tunisians of all backgrounds between the ages of 10 and 90 file into Sufi shrines, or zawiyas, making supplications as routinely as grabbing a morning coffee or getting on the bus for the morning commute.

Out of Tunisia’s 11.5 million population there are more than 300,000 devoted members to various Sufi orders, say experts, who estimate that the vast majority of Tunisians identify with a Sufi order or saint without labeling themselves as Sufi.

“Before there was a Tunisian state, there was Sufism,” Mohammed Jayyoudi, a retired aeronautical engineer says as he leaves a morning recitation at Sidi Mahrez shrine. “We would give up our Tunisian nationality before we give up our traditions and religious practices.”

Sufis in Tunisian history

Sufism flourished in Tunisia starting around the 11th century, a millennium before the modern state, as mystic clerics opened up zawiyas, centers to search for God’s truth, and hosted regular ziker – recitations of Koranic verses, prayers, and the names of God and prophets.

These Sufi zawiyas, which taught Koranic memorization and Islamic jurisprudence, became epicenters of education in North Africa and helped Islam spread out across the continent.

Sufi holy persons also established schools, hospitals, and markets – building and fortifying towns across Tunisia, even using minarets and strategically placed shrines as a lookout for invaders. Sufi figures also became important leaders of popular and armed resistance movements against French, Italian, and British colonial occupation in the 19th and early 20th centuries across North Africa.

In Tunisia, the shrines to Sufi saints are both geographic landmarks and part of local folklore. Locals in the capital base their directions around the shrine of Sidi Mahrez – known locally as sultan of the medina, Tunis’s old city. And Sidi Bou Said Al Baji, whose tomb on a seaside clifftop overlooks a town of the same name, is believed to protect Tunisia’s coasts from invaders to this day.

And there is a bond stronger than history binding Tunisians and Sufism: blood.

Many Tunisians make annual and sometimes weekly visits to their holy Sufi ancestors’ shrines. Even secular Tunisians are proud of their Sufi lineage.

“We are related to Shadhili, others to Ben Arous and so on,” says Oussama Marassi, a self-proclaimed Marxist, naming prominent Sufi saints. “Whether you pray or not, you will stand up for your ancestor.”

“The Salafis underestimated how central Sufism and Sufi saints are to Tunisians’ identity and personal history,” Sheikh Mohammed Riahi, Sufi cleric and descendant of Sufi saint Ibrahim Riahi, said after completing prayers at his ancestor’s shrine.

“These are our ancestors. When these brazen attacks happened, Tunisians stood with Sufi orders and against extremism. Tunisians will always stand up for their own.”

Women’s role

Another wedge between Tunisians and Salafism is the latter's male-dominated theology, alien to Tunisians’ progressive attitudes toward women’s role in the workplace and worship.

Women run many Sufi shrines across Tunisia, prepare and serve food for worshipers and the needy, while women are allowed to pray and supplicate at shrines alongside men – a rarity at Islamic sites.

Women take part in joint ziker recitations in shrines and at homes; often sitting in an adjacent room, joining men at the end of the recitations for food and tea. Women even perform their own rituals, such as a weekly recitations and Islamic songs at shrines such as Sidi Abul Hassan Shadhili zawiya in south Tunis.

This more inclusive approach of Sufism in Tunisia, combined with the country’s modernist, secular path since the 1950s, leaves many Tunisians bewildered by Salafis’ harsh restrictions on women.

“The Salafis tell us to stay in the home, clean, cook, and pray there,” says Noor, a Tunisian university student who was at Sidi Riahi zawiya. “All people – men and women – have the right to ascertain truth, remember God, and express their love to God. That is true Sufism.”

While Islamic movements have become hyper-politicized in much of the Arab world, Tunisian Sufis have been largely absent from the political sphere, protecting themselves from political attacks.

“For Tunisians, we don’t think of our way of worshiping and remembering God as Sufism or mysticism, it is just Islam,” says Sheikh Mazen Cherif, president of the Islamic World Union of Sufism, and a Tunisian Sufi thinker. “Sufism here unites, it doesn’t divide.”

Community outreach

Salafist movements have largely spread their hardline interpretation of Islam throughout the Arab world through charity; Gulf oil money funds Salafist charities that feed the poor, renovate homes, pay for university tuition, and provide funds to open small businesses in the Levant and North Africa.

In Tunisia, Sufis have the Salafists beat by around 900 years. Helping the poor has been a pillar of Sufism for nearly a millennium; many zawiyas operated as halfway homes for the needy and homeless, shop stalls were donated to local entrepreneurs.

To this day, Sufi zawiyas offer meals to the needy and worshipers. In multiple shrines visited by this reporter, homeless Tunisians and African migrants took part in communal meals following ziker.

“By giving and breaking bread we are reminded of our Islamic duty to help our fellow man and woman,” Faten Mohammed says as she brings a pot of pasta into Sidi Mahrez shrine. “We don’t need Salafis for this.”

Indeed, as fervent as Salafis may be in their own orthodox beliefs, they know their path forward in Tunisia today cannot be forced.

Saber Trabelsi, an unemployed resident of a marginalized Tunis suburb, came under the influence of hardline Salafists who came to his neighborhood mosque with offers of redemption and purpose in 2012. He, and many young men like him, reject Sufi mysticism and deride the veneration of saints as “polytheism” and “heresy.”

“Sufi practices are outside Islam and Sunni doctrine. It is paganism,” Mr. Trabelsi says.

But rather than confronting Sufi adherents with threats, insults, violence or denouncing them as kafirs, infidels, like many Salafis have done in Libya and Egypt, Trabelsi instead tries to politely counter their arguments with scripture.

Trabelsi says he has learned to live with, rather than attack, Sufism – and with good reason.

“My five brothers and sisters are all Sufis,” Trabelsi says. “All I can do is pray that they change their path.”

Difference-maker

For low-income youths, she brings an ocean of opportunity

This next story shows how the resource that could transform a child's life is often right under foot. You just have to make the connection by looking at the situation differently.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

-

By David Karas Correspondent

Shara Fisler’s love of research got a boost when she began working with local children as part of a university job. So in 1999 she rehabbed a 250-square-foot kayak closet on San Diego’s Mission Bay and shoehorned in a makeshift laboratory. She called her nonprofit operation Ocean Discovery, and with it began opening up new worlds for the area’s underserved youths. Her basic formula: Tap into the Pacific Ocean, the vast resource in these kids’ collective backyard. Some 10,000 children are within walking distance of the organization’s hub in City Heights. Ocean Discovery focuses on a “kid to career” timeline, with the hope that exposing young men and women to science can build the curiosity, understanding, and leadership that can foster an enduring interest. This year Ms. Fisler has doubled down on her commitment, adding a $17 million Living Lab and a 12,000-square-foot facility that includes a residency program for scientists. Alumni routinely return to share information about their careers or to mentor. “We are totally dedicated to every child’s success,” says Fisler. “Every young person we work with has the capacity to become a science and conservation leader.”

For low-income youths, she brings an ocean of opportunity

Carla Camacho grew up in the San Diego neighborhood of City Heights, in which some 30 languages and 100 dialects are spoken in the schools. Besides its diversity, however, the neighborhood is also known for high poverty rates.

Ms. Camacho, now in her mid-20s, acknowledges that, like many other City Heights youths, she was isolated. “You never really understand what else is in the world,” she says.

That all changed at the age of 14, when she joined Ocean Discovery Institute for an intensive science research project in Mexico’s Baja California. “With Ocean Discovery, they helped me to discover those things,” she says of the opportunities out there. “You’re doing awesome things like swimming with whale sharks.”

Founded in 1999 in San Diego, Ocean Discovery is a nonprofit organization that aims to open up new worlds for the area’s underserved young people. It taps into the vast resource in these youngsters’ backyard – the Pacific Ocean – and offers an array of possibilities for learning about science and engaging in research.

It’s the creation of Shara Fisler, who was inspired by research she did with young people when she was teaching at a university.

“We are totally dedicated to every child’s success, and know that they can be successful,” says Ms. Fisler, Ocean Discovery’s founder and executive director. “Every young person we work with has the capacity to become a science and conservation leader.”

When Fisler started Ocean Discovery, it was based in a rehabbed 250-square-foot kayak closet along San Diego’s Mission Bay. A makeshift laboratory was shoehorned into the tiny space, she recalls, yet it was enough space to host some meaningful experiences for youths.

Much has changed since that time, but the organization’s mission has remained constant. Ocean Discovery focuses on a “kid to career” timeline, with the hope that exposing young men and women to science can build the curiosity, understanding, and leadership that can spark a real interest in a career in science.

Today, Ocean Discovery hosts operations both at popular Pacific Beach and in City Heights. Some 10,000 children are within walking distance of the organization’s hub in City Heights.

In February, Fisler boosted the nonprofit’s commitment to that community, opening a $17 million Living Lab. The facility includes a state-of-the-art laboratory and learning space – even a residency program for scientists.

From a few hundred to room for 10,000

When Ocean Discovery launched, no more than a few hundred youths were engaged in programming each year. Today, that figure has risen to 6,000, and the Living Lab will easily allow the organization to exceed 10,000 on an annual basis.

Activities at Ocean Discovery range from dissecting a worm to learning about molecular biology. There are ample field experiences – anything from helping with habitat restoration to looking at creatures in tide pools. As the participants get older, they have more intensive opportunities involving deeper research.

“They are developing solutions that are really getting implemented around the world,” says Fisler, citing one project in which youths worked with researchers to find a way to reduce inadvertent catching of sea turtles in commercial fishing equipment. The team found that using light sticks can deter turtles from winding up in fishing nets, and the approach is being tested in Peru, Indonesia, and elsewhere.

On a recent afternoon, Fisler spoke with the Monitor in a trailer housing the nonprofit, just a short walk from the site of the soon-to-be-opened Living Lab. She shared how her interest in science education and working with underserved youths came about shortly after she earned her master’s degree in marine resource management from the University of Miami. She was then teaching as an adjunct faculty member at the University of San Diego, as well as continuing research begun during her graduate studies.

Fisler connected with an organization seeking internship placements for high-schoolers and would-be first-generation college students, and she involved a small team of those young people in her research for a summer.

“I saw what they were able to contribute to the scientific process, and I also saw their confidence just dramatically change over the course of the summer,” she says. “The way I could best tackle scientific problems was by providing opportunities for students who would otherwise not have them.”

That same spirit fuels Ocean Discovery, which now functions on a $2.2 million annual budget and has 28 staff members, including 10 AmeriCorps VISTA (Volunteers in Service to America) members. Programs are tuition-free, so the more than 350 volunteers and the combined support from government funding, foundations, individual donations, and corporate and in-kind giving are key.

How participants have succeeded

The nonprofit has celebrated success among its program participants. “We have students who are engineers, who are really excited about what they are doing, [and] we’ve got students that are incredibly passionate about fisheries,” Fisler says.

Data show that participants’ grade-point average in science classes is more than a point higher, on average, than that for nonparticipants, and state standardized test scores indicate similar gains. Some 7 in 10 participants are earning degrees in science or conservation, and students in Ocean Discovery’s after-school programs are eight times as likely to earn a college degree as are youths in the United States with a similar background.

Alumni routinely return to Ocean Discovery, Fisler says, whether it is to help teach, share information about their careers in the sciences, or mentor.

One such alumna, Camacho, has maintained her involvement with Ocean Discovery. Today, she serves as the organization’s manager of business development, and she’s worked with Fisler to explore replicating the program elsewhere – with a target to open a similar venture in Norfolk, Va.

“We found that every single community has a need for science education programs like these,” she says.

Praise from NOAA

Sarah Schoedinger, a senior program manager in the Office of Education at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, learned of Ocean Discovery in 2006 when her office provided a small grant to engage NOAA scientists in programs with young people. Since that time, the two entities have forged a deeper partnership, and NOAA has been involved in recruiting for the nonprofit’s scientist-in-residence program and in the replication of the business model in Norfolk.

“I’ve learned from first-hand observation of their programs and conversations with current and former students about myriad positive impacts they have on the kids, their families and other members of the community, and even the physical landscape in the local community,” Ms. Schoedinger says in an email interview. “Ocean Discovery Institute is a trusted partner among the City Heights community, [and] I think they have succeeded in doing so, at least in part, because they are there serving those kids year-in and year-out.”

She also speaks highly of Fisler’s leadership. “Shara definitely sets the tone of the workplace culture there for staff, volunteers and students: You’re expected to work hard, learn from mistakes, but also to have fun and celebrate successes....”

For Fisler, it’s all about inspiring youths in ways they might not have considered: “A young person will start to believe that science is something they can do,” she says, “and a scientist is something they can be.”

[This story has been updated to include news of the facility’s opening in February.]

• For more information, visit oceandiscoveryinstitute.org.

How to take action

UniversalGiving helps people give to and volunteer for top-performing charitable organizations around the world. All the projects are vetted by UniversalGiving; 100 percent of each donation goes directly to the listed cause. Below are links to three groups encouraging conservation or learning:

EcoLogic Development Fund works with rural and indigenous peoples to protect tropical ecosystems in Central America and Mexico. Take action: Support conservation in Honduras’s Pico Bonito National Park.

Teach With Africa coordinates a reciprocal exchange of teaching and learning in Africa and the United States. Take action: Cover the expenses for a teacher to spend a summer in South Africa working with children.

Seeds of Learning fosters learning in developing communities of Central America while educating volunteers about the region. Take action: Support this organization’s Learning Resource Centers in Nicaragua.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

The opioid crisis requires anger management

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By The Monitor's Editorial Board

A federal judge in Cleveland has been tasked with mediating a settlement out of more than 180 lawsuits brought by states and others against name-brand opioid makers and drug distributors. Judge Dan Polster’s strong counsel: Ending the opioid crisis is too urgent to allow years of litigation over who is to blame. The first step in finding a solution is to reduce the anger over causes. The way forward is to admit a common interest in funding remedies. He has ordered all sides to think through the problem together. With the United States losing about 150 people a day to drug overdoses, the judge is wise to avoid a jury trial and set a tone of reconciliation. The outcome of Judge Polster’s tactics may not be known until the end of 2018. But one possible result of the talks so far was the announcement by Purdue Pharma, maker of OxyContin, that it would no longer market the drug to doctors. The company also said it would work closely with the judge’s purpose. His anger management may be working.

The opioid crisis requires anger management

For Americans looking to reverse the rise in opioid overdoses, a good place to start is the courtroom of Dan Polster, a federal judge in Cleveland. He has been tasked to mediate a legal settlement out of more than 180 lawsuits brought by states and others against name-brand opioid makers and drug distributors.

Judge Polster has offered this strong counsel to the plaintiffs and defendants: Ending the opioid crisis is too urgent to allow years of litigation over who is to blame. The first step in finding a solution is to reduce the anger over causes. The way forward is to admit a common interest in funding remedies.

He has ordered all sides to think through the problem together, “not as a fight to be won or lost,” as he told a group of law students. He has brought in experts on drug use and treatment to advise the litigants in closed-door sessions. And to reduce the temptation to raise the political temperature, he ordered the parties not to speak to the news media.

Courts, like politics or the news media, need not always be arenas solely for adversarial battles. When the United States is losing about 150 people a day to drug overdoses, the judge is wise to avoid a jury trial and set a tone of reconciliation. The opposing views and facts over the responsibility of the drug industry in marketing painkillers would take too long to sort out in court appeals, would be unpredictable in the outcome, and perhaps yield too little in money years from now.

Judges often push litigants to see the greater good in a brokered settlement. The reason is obvious. “It’s almost never productive to get the other side angry,” Polster said. “They lash out and hurt you and themselves.” Or as President Obama once put it, “We can’t move forward if all we do is tear each other down.”

The judge says he felt compelled to force a large-scale mediation effort because, as he put it, other branches of government have “punted” on solving the opioid crisis. The additional money needed by governments to prevent and treat opioid addiction is estimated to be in the billions of dollars.

The outcome of the judge’s tactics may not be known until the end of 2018. But one possible result of the talks so far was the announcement by Purdue Pharma, maker of OxyContin, that it would no longer market the drug to doctors. The company also said it would work closely with the judge’s purpose. His anger management may be working.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

The rescue of the gull

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Carmen Diaz-Bolton

In today’s column, a woman shares how an encounter with a man struggling to free a sea gull from a fishing line led to gratitude for our ability to acknowledge and feel God’s care.

The rescue of the gull

One night a little after sunset while biking on the jetty at a nearby beach, I saw a lone man about 50 feet away, peacefully fishing at the jetty’s tip. It was a picture-perfect scene.

As I dismounted my bike to more fully appreciate the surrounding beauty and fading light, I realized the man was struggling with his fishing line. He had caught not a fish, but a seagull. The tip of its wing was looped around the fishing line, and the gull, in panic mode, was making it worse. The gull didn’t let up trying to flee, especially when the man came closer to cut the line as short as he could. The gull was clearly starting to exhaust itself, and the light was dimming fast. Freedom seemed almost impossible, and ultimately the man retreated off the wet rocks and began packing his gear.

It didn’t help matters any when a man in a skiff, who had been watching this whole thing from his perspective, motored up and hollered at the fisherman for not doing better. The fisherman dejectedly turned away and saw that I too had been watching. I could almost hear him thinking, “Oh boy, here comes another reprimand.”

Instead, my heart went out to the man and the gull, and I turned to God in prayer, something I’ve found helpful so many times before. Earlier that day, I’d been reflecting on some passages in a book that has helped me love and understand the Bible, particularly the life and words of Christ Jesus. The book, “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures” by Monitor founder Mary Baker Eddy, explains the power of the Christ – the divine Truth Jesus represented. Christian Science explains that the Christ is God’s healing message of love for everyone, and that this message comes to each one of us, as it came with such healing power through Jesus. So everyone is inherently capable of feeling and expressing God’s infinite love.

The passages I had pondered refer to Christ “casting out evils” and illustrating “the coincidence, or spiritual agreement, between God and man in His image” (pp. 332-333). As God’s spiritual image, we reflect God’s infinite goodness and are completely cared for by Him, the divine Principle, which is Love. My thought was uplifted by these ideas. I saw that God’s supreme, infinite all-goodness is the spiritual reality of all that truly is, and I affirmed that it’s not chance but divine Love that governs and controls all creation. As Christ Jesus taught, even the sparrows are cared for by God (see Luke 12:6).

As I prayed, with joy I felt a sense of the fullness of the authority of God, good, and a deep conviction of the truths I was affirming.

I then felt impelled to hop onto some large boulders closer to the man. I was hearing and responding to the Christ, expressing spiritual love by cheering this man on. Although I was downwind, he heard me as I hollered out encouragement for him to continue, convinced that his noble efforts to free the gull would not be in vain.

He beamed, gave me a thumbs up, and then stepped back down onto the wet boulders close to the water’s edge where the recovering gull was perched, and redoubled his efforts. This time he was able to cut off a second portion of the line, and we were both rewarded by seeing the gull gently float away, with frayed but intact pinions, paddling toward his brother and sister birds on some nearby rocks.

Beside the joy of seeing the gull freed, the takeaway for me was a childlike, heartfelt gratitude for our ability to pray, to acknowledge – and feel – God’s care, in whatever situation we may find ourselves. The Christly inspiration such prayer brings blesses us, and others. It enables us to encourage and buoy those we encounter.

A message of love

Their light undimmed

A look ahead

Thanks for being here today. Please come back tomorrow, when West Coast correspondent Jessica Mendoza will look at the Trump administration’s lawsuit against California over sanctuary city laws. It’s using the same tactic the Obama White House used in suing North Carolina over its “bathroom bill.”