- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- In a Trump-country squeaker, some Democrats see a blueprint

- A surge in displaced Afghans challenges West’s narrative on gains

- In blue states, 'tax the rich' isn't so simple anymore

- A cross-border shooting, and a trial that could touch US conduct abroad

- A thinker who pushed at the limits of human thought

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Monitor Daily Intro for March 14, 2018

It might be time to flip an old saying – “stop acting like a child” – on its head.

In this case, they’re not really children but young people. Across the United States today, many walked out of school for 17 minutes to protest gun violence – one minute for each victim of the Stoneman Douglas High School shooting on Feb. 14 – through everything from speeches to “lie-ins.”

At a time when civics education sometimes falls short, students are augmenting the curriculum, studying rights, how bills are shaped, how different constituencies get heard. They’re talking up voting. While many have responded to #NationalWalkoutDay, others have focused on #walkupnotout, which encourages students to reach out to loners and people who don't share their views.

At Ronald Reagan High School in San Antonio, the Monitor’s Henry Gass spoke with members of the girls’ track team who were practicing during spring break. One wanted better safeguards against students going “off the rails.” Another’s class wrote to their representative. One noted a rise in exchanges with friends and neighbors. One wanted more security drills.

Few students are suggesting pat solutions. Instead, they’re saying their engagement is here to stay. And adults are listening. At a town hall meeting near me, questions from two students about how to engage constructively – they didn’t share their politics – generated a cheer. The crowd seemed to be thinking it was time to start acting like a child.

Now to our five stories, including ones that remind us to address very human needs on the ground and encourage us to think beyond conventional confines.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

In a Trump-country squeaker, some Democrats see a blueprint

Democrats are busy absorbing lessons learned from their candidate's likely win in Pennsylvania's 18th District as they look to November. But one in particular may stand out. As former speaker of the House Tip O'Neill was fond of saying, "all politics is local."

National Republicans scrambled to regroup Wednesday after apparently losing a hotly contested special House election in western Pennsylvania by fewer than 700 votes. Behind closed doors, House Speaker Paul Ryan called the race a “wake-up call,” according to sources who were in the room. Democrat Conor Lamb’s narrow victory in a district that President Trump had won by almost 20 points shows that there’s a way for the party to win back white, working-class voters: by championing their issues. Workers’ rights, wages, and protecting pensions, Social Security, and Medicare all played to Mr. Lamb’s advantage against Republican state Rep. Rick Saccone. Lamb was also “conservative enough” on social issues such as guns and abortion to prevail (although, as of this writing, Mr. Saccone had not conceded). And it didn’t hurt that he’s a young telegenic former US Marine and former federal prosecutor running for office for the first time – the face of change. “Here’s the takeaway: Candidates matter. Campaigns matter,” says Joe DiSarro, chairman of the political science department at Washington & Jefferson College in Washington, Pa., and a member of the Republican State Committee.

In a Trump-country squeaker, some Democrats see a blueprint

President Trump’s surprise victory in the rust belt – and thus the presidential election – 16 months ago left many Democrats despondent that they had “lost” white working-class America.

But in politics, the world never sits still. Democrat Conor Lamb’s apparent narrow win Tuesday in a special House election in western Pennsylvania, in a district that Mr. Trump had won by almost 20 points, shows that there’s a way for the party to win those voters back: Champion their issues.

Workers’ rights, wages, and protecting pensions, Social Security, and Medicare – all played to Mr. Lamb’s advantage against Republican state Rep. Rick Saccone. And, analysts say, Lamb was “conservative enough” on social issues such as guns and abortion to prevail (although, as of this writing, Mr. Saccone had not conceded and the GOP was considering a recount).

“Here’s the takeaway: Candidates matter. Campaigns matter,” says Joe DiSarro, chairman of the political science department at Washington & Jefferson College in Washington, Pa., and a member of the Republican State Committee.

“You have to be pragmatic,” Mr. DiSarro adds. “You cannot ignore 25 percent of the constituency, which is labor, and expect to win.”

In short, to boost the chances of success, a candidate should “match” the district. Unlike the Republican congressman who resigned from the 18th district House seat last October amid scandal, Saccone has taken conservative positions that labor unions oppose.

“A lot of people here are non-ideological,” said former Rep. Melissa Hart (R) of Pennsylvania, who represented a nearby district, over lunch last week in Carnegie, Pa. “This district isn’t hard right.”

Indeed, it is a district of contrasts. The wealthier, more populated, close-in Pittsburgh suburbs went strongly for Lamb, while Saccone prevailed in the further-out, more rural areas.

Long lines were reported in suburban Allegheny County – in some cases, longer than those in the 2016 general election.

“I’ve never seen so many young voters,” said Lori, a 50-something resident of Upper St. Clair who has lived in the area for more than 20 years. “Usually I’m the youngest one in line.”

‘A wake-up call’

National Republicans scrambled to regroup Wednesday, after a long night that ended with Lamb ahead by fewer than 700 votes, or two-tenths of a percent. Behind closed doors, House Speaker Paul Ryan called the Pennsylvania race a “wake-up call,” according to sources who were in the room.

Publicly, Mr. Ryan pointed to the Pennsylvania Democrats’ ability to hand-pick a “conservative” candidate, and avoid a primary dominated by activists who may have selected a more liberal nominee. During the campaign, the GOP had fought hard to turn Lamb into a “Nancy Pelosi Democrat,” referring to the House minority leader – but to no avail. Lamb disavowed Ms. Pelosi early on, saying he would not vote for her as leader.

Pennsylvania Republicans, too, selected their candidate in a state party committee vote, but wound up with someone who ended up running what was widely seen as an ineffective campaign. Saccone didn’t raise much money, forcing outside Republicans to funnel money (more than $10 million) into the race – money that now can’t be deployed in the midterms.

Democratic candidates across the country, regardless of ideology, have embraced Lamb, and are fundraising off his success. It doesn’t hurt that he’s a young, telegenic former Marine and former federal prosecutor running for office for the first time – the face of “change.”

Saccone is a generation older, and boasts an impressive career in the Air Force, diplomacy, academia, business, and now four terms in the state legislature. But to some voters, he’s part of the Harrisburg “swamp” – despite trying to wrap himself in the outsider mantle of Trump.

Six days before the election, Saccone knew he might have a problem.

“This time of year, half the people I talk to from my district are in Florida right now,” the genial Republican said in an interview at his Greensburg, Pa., field office last week. “My gosh, half of them. I’ll say, ‘Did you remember to vote absentee?’ A lot did, but a lot didn’t.”

Organized labor’s clout

Aside from Lamb, a big winner coming out of Tuesday is organized labor. In 2016, labor made the same mistake as Hillary Clinton’s presidential campaign: relying too heavily on big data, and focusing too narrowly on a small universe of undecided voters, instead of doing aggressive, widespread outreach.

This time, in the Pennsylvania race, organized labor was “focused and unified,” says Tim Waters, national political director of the Pittsburgh-based United Steelworkers, which worked alongside carpenters, painters, steamfitters, laborers, and other unions.

“In the more blue-collar towns, even if Lamb didn’t win but improved the Democratic vote significantly, it shows that unions have clout,” says Mike Mikus, a Democratic consultant who lives in Pennsylvania’s 18th district.

Then there’s the suburbs. “If the Republicans are going to stop the bleeding in wealthier, highly-educated communities, they’re going to have to create some distance from Trump,” Mr. Mikus says. “I don’t know if they’re willing.”

For now, Mikus is cautiously optimistic about a Democratic “wave” in the midterms.

"It’s a long way to the election, but all signs point to that,” he says. “If I’m a Republican running in the Philadelphia suburbs, I’m thinking of a possible graceful exit from the stage so I don’t get embarrassed in November.”

Staff writer Francine Kiefer contributed to this report.

Share this article

Link copied.

A surge in displaced Afghans challenges West’s narrative on gains

Last year, Afghanistan lost its UN designation as a "post-conflict" society. What's at stake now is trust in the longstanding argument that the country could sustain a drive toward social, political, and educational progress.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

After four decades of conflict, more than 1.5 million Afghans – roughly 4 percent of the population – are internally displaced. Some 448,000 were added to the rolls in 2017. Another 30,000 have joined them this year. The dominant narrative of social and political progress, pushed for years by the United States and other Western countries, is fading into memory. There are many reasons Afghans are fleeing in such numbers. Among them: the expansion of Taliban-held territory since the US and NATO withdrew the bulk of their forces, and a surge in US bombing missions that has dramatically increased civilian casualties. Relief agencies are scrambling to keep up. “For us it’s a sign that the country is much less secure. People feel a lot less safe and certain,” says an official with the Norwegian Refugee Council in Kabul, Afghanistan. Civilians are fleeing both violence and fear of retribution. “If you put up your hand and said, ‘I’m your friend. I will be your district governor,’ ” says another Western official, “and then in 2014 you have 100,000 foreign troops leave, all of a sudden [you] have to start packing [your] bags.”

A surge in displaced Afghans challenges West’s narrative on gains

Her body shaking and tears flowing, Maghul is the epitome of what it means to be among the latest crop of war victims in Afghanistan.

Taliban militants came to her town in central Wardak province in mid-2017, and during battle with the Afghan police, burned her home and killed her husband, a farmer who was out “doing his daily routine,” she says.

So Maghul had no choice but to escape with her two grown sons and join the ranks of nearly half a million internally displaced people (IDPs) who fled their homes in 2017 alone. The upheaval adds to an astonishing metric of the scale of on-going war, 16 years after American troops first arrived to oust the Taliban.

One son now begs on the streets of Kabul, coming home long after dark, despite the constant risk of car bombs.

“I tell him, ‘Don’t come late or the Taliban will kill you like they killed your father,’” says Maghul, sobbing on the floor of a threadbare room on a distant, western fringe of the Afghan capital.

“He replies, ‘It’s better that they kill me, rather than live in these conditions,’” the mother recounts, resigned. “He says, ‘Death is better than this life.’”

This shattered family is hardly alone, their experience just one result of a growing multitude of causes for the recent surge of displacement across the country. With more than 1.5 million Afghans – roughly 4 percent of the population – displaced after four decades of conflict, and 448,000 added in 2017 alone, relief agencies are scrambling to provide help as the dominant narrative of Afghan social and political progress, pushed for years by US and Western governments, fades into memory.

“For us it’s a sign that the country is much less secure, people feel a lot less safe and certain,” says William Carter, the program head for the Norwegian Refugee Council (NRC) in Kabul, one of the largest nongovernmental organizations in the country, which handles emergency shelters, food, and water and reaches 300,000 Afghans a year.

“Regardless of the other metrics, people feel forced to leave their homes, which is a pretty telling indicator of the temperature here,” says Mr. Carter. The latest UN figures indicate that more than 30,000 Afghans have already been displaced this year, one-third of them in “hard to reach areas.”

There are many reasons why, at this stage of Afghanistan’s long-burning war, Afghans are fleeing their homes in such large numbers, analysts and relief experts say.

One strategic reason is that the Taliban have expanded their territory, to controlling or contesting 44 percent of the country today, since US and NATO withdrew the bulk of their forces in 2014.

Fear of retribution

That has meant more on-the-ground battles, often to seize or defend population centers. And even though the Taliban have adjusted their tactics in some places – behaving in a more acceptable manner to locals, for example, to win their support – in many other places, like Maghul’s village, they have attacked those they saw as supportive of the government.

The UN last year changed its category of Afghanistan from a post-conflict country to a country in conflict. The risks were made plain by a late 2017 decision by the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), which works fearlessly on front lines around the world, to substantially cut back in Afghanistan after three separate, lethal incidents.

Ironically, some note that the Taliban expansion has also meant relative peace in some areas – a fragile calm that could be disrupted by an influx of several thousand new US troops deployed by President Trump with orders to “fight and win.”

But more often, civilians are fleeing both the violence and in fear that a change in local rule could bring retribution against those who threw in with Kabul.

The surge in IDPs “shows the escalation of the conflict continues, [and] how more winners and losers are emerging” as the Taliban takes more and more territory, says a Western official in Kabul, who asked not to be named.

Many Afghans were “really incentivized and coerced” to align themselves with the government across the country, when US and NATO forces controlled most of it, and asked: Who’s our friend?

“If you put up your hand and said, ‘I’m your friend, I will be your district governor, or I will volunteer my sons to be part of the Afghan local police’ … and then in 2014 you have 100,000 foreign troops leave, all of a sudden those people who put up their hands have to start packing their bags,” says the Western official.

Stepped up US bombing

The sharp rise in US airstrikes that began last year also makes a difference, when Afghans in front-line areas are making a decision whether to stay or go.

“From our point of view, we see that change in the conflict, where the previous unequal balance of power is now more equal and more territory is fought over and more people are being displaced,” says Carter.

At the same time, a surge in the number of bombs falling near your home “is one of the most decisive factors that it’s time to go,” he says.

So while headlines focus on high-profile attacks on Afghan security forces, one crisis largely hidden from view is of populations still being forced to move. The numbers have grown dramatically, reaching 630,000 in 2016 – with 200,000 of those from the temporary fall of the northern provincial capital of Kunduz to the Taliban.

The impact on those displaced is clear and evolves “over time due to exhaustion of coping mechanisms and only basic emergency assistance provided,” notes the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, which tracks conflict displacement with an interactive map. “Inadequate shelter, food insecurity, insufficient access to sanitation and health facilities, as well as a lack of protection, often result in precarious living conditions.”

The NRC, for one, has had to change its strategy accordingly, first by reversing a planned downsizing in 2015, which was partly predicated on fewer displaced Afghans. Instead, it has tripled its budget to perhaps $30 million for 2018, largely to accommodate the surge, says Carter.

Eyes on any 2018 trend

Of Afghanistan’s 34 provinces, as many as 32 produce IDPs, while some 30 provinces at the same time host IDPs. Roughly half of Afghanistan’s IDPs have, in fact, been displaced twice.

And yet, in some areas “the rate of worsening seems to be slowing,” says the Western official.

“Some people are talking about a flattening trend, and plateauing of the rates of violence … that can be described as a Pax Talibana, as the Taliban seize some areas and they are not contested,” he says.

“So if you are a resident of far-flung northern Helmand, or rural Oruzgan, maybe things are looking up for you, because this year you didn’t see any Americans, your poppy harvest was not slashed and burnt … the Taliban come around and collect their taxes, but only once,” says the official.

“So everyone’s going to be watching 2018 to see if these trends continue,” he adds. “There’s a risk that the arrival of more US forces will push us back into a cycle of escalating violence.”

Pockets of temporary peace where the Taliban are in control is not acceptable for the government, which has struggled to effectively impose its writ across the country and been embarrassed by a series of lethal bombings in the capital and beyond.

“Nothing is going in the right direction in Afghanistan,” laments one aid worker in Kabul, who spoke off the record.

“We’ve got elections coming up; we are bound to see a bit of the political fabric tearing a little, and there is nothing that has slowed down the insurgencies,” he says. “So the only potential is if the peace process does anything, which we always think is a low likelihood.”

Grim survival

And that unlikely prospect was not enough to prevent the exodus of Gulbakht, a mother of six with a black headscarf, who fled a Taliban night attack on her village in March 2017. Her husband, Haider, “just a simple man, a laborer,” she says, stayed behind in a bid to protect their daughter Sakina, who was paralyzed with fear and refused to move.

Haider was killed, his mutilated body recovered days later, and homes burned. Sakina survived, but since then has not said a word. Today the remaining family lives in a small shelter, built and supported by the NRC and warmed by a single wood-burning stove, in western Kabul.

“There is no good among the Taliban. If they were good, they would not kill my husband,” says Gulbakht, who only goes by one name. Most of the 300 families in their village in Ghor, central Afghanistan, fled.

In the room is a timeless scene, punctuated by the tick-tick sound of three daughters working at a rudimentary loom, making slow and tedious progress on a carpet during nine hours of winter daylight.

They rise and sleep according to calls to prayer from nearby mosques. And in several weeks they have woven just six inches, of a carpet that will one day be more than two meters long. If there are no mistakes in it, says Gulbakht, they hope to sell it for the equivalent of $85.

For these displaced Afghan survivors, there is no clock on the wall, and no other means of marking time.

In blue states, 'tax the rich' isn't so simple anymore

Are there practical limits to taxing the affluent? Democratic states' philosophical commitment to progressive tax codes could be put to the test by federal tax reform that changes the calculus for wealthy residents.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

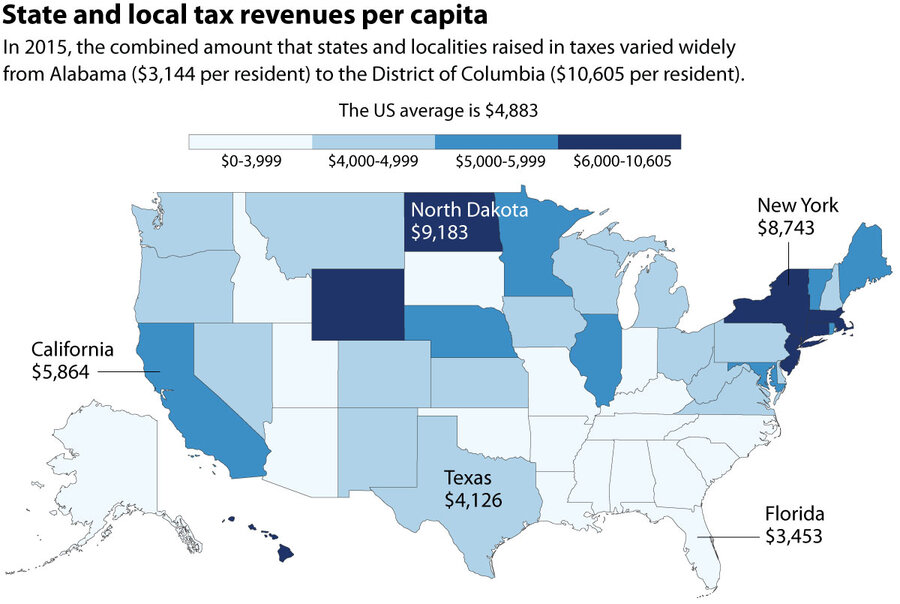

President Trump's tax cuts have put Democratic governors of high-tax states in a quandary. Do they create the perfect opening to tax the rich even more at the state level, as New Jersey’s Phil Murphy has just proposed with a millionaires tax? Or is there a reason to worry that, now that the rich can’t deduct all their state and local taxes on their federal return, they’ll move out if the state doesn’t lower the tax burden on them? Democratic politicians in several states want to make it possible and tax-deductible for residents to fund local government through charitable contributions, thus preserving deductions used by millionaires and others on federal taxes. Some research suggests that fears of a millionaire migration are overblown. Few people leave because of tax rates, especially from places like Wall Street and Silicon Valley. Still, taxes are a factor for people at all income levels. Says CarmenMarie Mangiola, who is leaving Rochester, N.Y., and moving to Virginia: State and local taxes “are quite high,” and “lots of people are fleeing New York.”

In blue states, 'tax the rich' isn't so simple anymore

On Tuesday New Jersey's new Democratic governor, Phil Murphy, broke sharply with President Trump and Congress on taxes. He used his first budget address to propose a hefty tax hike on millionaires.

In other high-tax states, Democratic politicians are emphasizing a different way to go anti-Trump. New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo, for example, is proposing workaround schemes so that upper-income residents won’t be hit so hard by one particular provision in the president’s tax-cut law – the cap on the amount of state or local taxes that can be deducted from federal returns.

Here are two Democratic leaders in two liberal states, and one is calling to tax the rich more while the other is worried about how to shelter those same taxpayers.

The two aren’t actually that far apart, but the apparent rift is noteworthy. It points toward a challenge for blue states that are poles apart from Trump politically: They want progressive tax codes and yet, as high-spending states, they’re also worried about retaining the “geese” that lay golden eggs. Politicians like Mr. Cuomo seem anxious about a tipping point where, if taxed too much, wealthy and upwardly mobile taxpayers may flee to other states.

“The cap [on deductions] is not going to immediately impact state revenues, but it does put pressure on the states,” says Frank Sammartino, a senior fellow at the Tax Policy Center, a research group in Washington. “People will feel they're no longer getting relief from some portion of their state income taxes, so there might be pressure on the states to reduce taxes and particularly taxes on higher incomes.”

Or at least not raise them too high. There used to be no cap for the state and local tax (SALT) deduction. Starting this year, a tax filer will only be able to deduct up to $10,000 per year in those taxes. If the income tax on millionaires rises in New Jersey, the federal government is no longer cushioning the blow by reducing the amount of federal tax that individual will owe.

At a minimum, the federal tax law is casting a red-blue divide in state fiscal policy into sharper relief. Where some Republican-dominated states like Florida and Texas tout low taxes as a selling point to lure businesses and new residents, Democratic-leaning states in the Northeast or Pacific regions have both high taxes and some fiscal challenges like budget shortfalls.

High tax anxiety

“We are absolutely in a crisis mode right now,” Tom Bracken, president of the New Jersey Chamber of Commerce, said in a news conference last fall as Republicans were prepping the federal tax cuts. He welcomed the GOP goal of reducing business taxes (which the law did) but warned that New Jersey and a few other states faced adverse effects from the legislation.

“We are the highest tax state in the country,” he said, also pointing to figures showing significant outmigration. “The thing we cannot afford right now is to become less affordable, to become less competitive, and to continue to give people the incentive to leave this state or not to be attracted to this state.”

The upset that governors like Cuomo and others are voicing is understandable, says Meg Wiehe, deputy director of the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, a left-leaning research group. These states see they’re getting the short end of the stick from the federal law, and they suspect that Republican motives were at least partly political. (In a bill that largely showered tax cuts on individuals and businesses, the SALT deduction was one of the few moves designed to add some offsetting federal revenue. And it’s a deduction that most affects these blue states with high income and property taxes.) Cuomo of New York has called it an attack on his state.

At the same time, Ms. Wiehe sees irony and perhaps confusion in the Democratic response. The highest-earning taxpayers already will be big beneficiaries of the Trump tax cuts – even if they live in states like New Jersey – and now state-level Democrats are jumping through hoops trying to help them even more.

Cuomo voices worry as New York suddenly compares less favorably with other states as a place to reside. He’s proposing ways for the state to collect less of its revenue from income taxes and more in the form of payroll taxes, as well as making it possible and tax-deductible for residents to fund state government through charitable contributions.

Marginal impact?

But his concerns about migration may be overblown. Wiehe says job opportunities like those on Wall Street and in Silicon Valley will keep a big supply of high-earners in states like New York and California. And she points to academic research suggesting that few people migrate due to tax rates.

With taxes going down at the federal level, perhaps Governor Murphy’s proposed millionaire’s tax wouldn't sting so much.

“We are standing for fairness and fiscal responsibility by asking those with taxable incomes in excess of $1 million to pay a little more,” said Murphy Tuesday. “The irrefutable fact is that we have a thousand more millionaires today than we did at our pre-recession peak, and I’m sure none of them are here for the low taxes.”

Murphy, who took office two months ago, said the state needs the added revenue to cover rising needs in education and infrastructure.

His budget plan also called for some measures designed to offset the reduced SALT deduction.

Not all Democrats in the state are on board with his proposal. Since the federal law passed in December, state Senate President Stephen Sweeney has been calling tax surcharge on millionaires a “last resort,” even though he has supported such measures in the past. He’s urging a hike in business taxes instead.

As Wiehe notes, there’s considerable debate over how big a role taxes play in causing people and businesses to move from one state to another. Economists generally say a host of other factors are more important.

As Amazon ponders where to site a second headquarters – in other words, where to best locate to attract and retain an estimated 50,000 well-educated workers – it’s notable that its finalist cities include not just Austin and Nashville but also high-tax areas like New York, Chicago, and Montgomery County, Md., just outside Washington, D.C.

Still, taxes are a piece of the puzzle. New Jersey’s income ledger took a noticeable hit in 2016 because just one resident, billionaire hedge fund manager David Tepper, moved himself and his business to Florida.

Tax hit for lower incomes

It’s not just rich people who may move. It’s also people like CarmenMarie Mangiola of Rochester, N.Y. After being a stay-at-home mom and then working for years as a school teacher, she’s already downsized once, selling one home for a smaller one as costs, including taxes, got too high.

Now she’s planning to move to Virginia, because the taxes on her $100,000 home are more than $5,000 a year and rising. Now in her 60s, she’s living on a Social Security disability payment as she prepares to retire.

“It’s fine that we protect the next generation by creating good schools” and services, she says. But state and local taxes “are quite high” and “lots of people are fleeing New York.”

The squeeze of high taxes and high costs for government services affect a range of states, including four – Connecticut, New York, New Jersey, and Maryland – that are planning a lawsuit seeking to thwart the cap on SALT deductions.

The federal law “has put the ball in their court,” says Eileen Norcross at George Mason University’s Mercatus Center.

And in Maryland, the fact that a liberal-leaning electorate voted for Republican Larry Hogan as governor in 2014 symbolizes how, even without any nudge from federal policies, many blue-state voters and politicians have a wary eye on taxes and public spending levels.

In the upscale Maryland city of Bethesda, Chad Lieberman doesn't have any plans to call a moving van because of high taxes. As the proprietor of a small web-development business, he’s happy that state and local agencies provide strong schools, nice parks, and other public services.

But Mr. Lieberman is also watching to see what federal or local tax changes will mean for him. And as a self-described "small-government conservative" on fiscal issues, he says that high taxes may signal room for belt-tightening in public-sector budgets.

Tax Policy Center

A cross-border shooting, and a trial that could touch US conduct abroad

Issues around immigration and border security can get lost in abstractions. But when bullets fired by an agent on the US side of the border struck a teen in Mexico, the fallout was deeply human.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 13 Min. )

-

By Lourdes Medrano

The area around Nogales, Ariz., and Nogales, Mexico, is an expanse of tight neighborhoods and rolling hills that stretch into the desert. There’s a wall. An imposing structure of steel, it went up in 2011 – a year before a cross-border shooting involving a US agent and a 16-year-old Mexican teenager named José Antonio Elena Rodriguez. José was struck by at least 10 bullets, according to his autopsy. Lonnie Swartz, the Border Patrol agent, is the first to be prosecuted by the Department of Justice for killing someone on Mexican soil. The shooting raises tough jurisdictional issues. A federal judge cleared the way for the trial, ruling that the agent was standing on federal land when he fired. A civil case tests whether the protections that apply to a US citizen also apply to a Mexican, in Mexico, who might have been wronged by someone in the United States. Postponed seven times, the criminal trial is set for March 20 in Tucson, Ariz. It’s a case with important legal and national-security ramifications that reach far beyond this border and US-Mexican relations. It also pits the future of an agent with a difficult and dangerous job against a family seeking answers. “It’s taken so long just to get to this point, to decide if the man is guilty or innocent,” says Araceli Rodriguez, José’s mother. “The truth is that, whatever the circumstances, he killed my son.”

A cross-border shooting, and a trial that could touch US conduct abroad

Luis Contreras, a doctor who lives and works in a building just south of the border fence that separates the United States from Mexico here, was playing a game on his computer late one night when an eruption of gunfire jolted him. He quickly turned off all the lights to avoid being hit, and, once the shooting stopped, cautiously peeked through the door. On the darkened sidewalk below, he could make out the figure of a person lying face down.

“He wasn’t moving,” Dr. Contreras recalls.

Moments later, at 11:35 p.m., a supervisor at police headquarters in Nogales, Mexico, took a call. It was someone with the US Border Patrol who said, in Spanish, that shots had been fired and rocks hurled along a stretch of the border shared with Nogales, Ariz.

“Apparently, someone is hurt on the Mexican side,” the caller said.

“How many people are there at the location?” the police supervisor asked.

“On the Mexican side, I couldn’t say,” the caller replied. “On our side, there are about five of us.”

The person on the sidewalk, José Antonio Elena Rodriguez, was 16 years old when he died that night on Oct. 10, 2012, in a hail of bullets fired, US prosecutors say, by a US Border Patrol agent from his P2000 semiautomatic pistol. At least 10 bullets struck the teen, mostly from behind, according to an autopsy conducted in Mexico.

Two years would pass before the name of the agent, Lonnie Swartz, was revealed in documents unsealed in federal court after José’s mother filed a civil lawsuit against him. The following year, a federal grand jury indicted Mr. Swartz for second-degree murder. Postponed seven times, his criminal trial is now set for March 20 in Tucson, Ariz., in a case with important legal and national security ramifications as well as implications for the future of US-Mexican relations.

Swartz is the first Border Patrol agent to be prosecuted by the US Department of Justice (DOJ) for killing someone on Mexican soil. The shooting raises complex jurisdictional issues. In the criminal case, a federal judge cleared the way for the trial with a ruling that the agent was standing on federal land when he fired his gun and thus could be prosecuted.

A parallel civil case tests whether the Constitution reaches beyond the nation’s borders – whether the same legal protections that apply to a US citizen apply to a Mexican standing in Mexico who might have been wronged by someone in the US. A ruling in this case could affect far more than border shootings: It could, for instance, influence whether civilians killed by US drone strikes in foreign lands could sue the US government.

“The legal issue of whether noncitizens who are not in the US are protected by the Constitution – that question applies to lots of other situations that are very different from [the Swartz case],” says Sarah Seo, an associate professor of law at the University of Iowa in Iowa City.

The criminal trial also comes at a time when the Trump administration wants to post thousands more agents along the southern border to stem illegal immigration and the flow of drugs into the US. However effective the growing law enforcement presence may be in curbing illegal activity, some experts say that it will likely lead to more border clashes.

To law enforcement officials, the border is already a zone of extreme danger. They portray a world in which they have to routinely deal with human traffickers and drug smugglers, many of whom are armed, not to mention legions of rock throwers. Immigrant rights groups say the Border Patrol is the villain here: They believe agents too often rough up detainees and use force – including deadly force – more frequently than they need to.

These two narratives, which in their own shadowy way are played out almost nightly somewhere along one of the world’s most porous borders, will clash in a wood-paneled courtroom in Tucson.

The border between Nogales, Ariz., and Nogales, Mexico, is an urban expanse of timeworn, densely packed neighborhoods and rolling hills stretching deep into the surrounding high desert valley. Unpretentious houses and one-story buildings line both sides of the border, just a few steps from the wall separating the two countries. The population of Nogales, Mexico, estimated at 250,000 to 300,000, dwarfs that of Nogales, Ariz., which is 20,000.

In the US, green-and-white Border Patrol SUVs constantly prowl the road along the border fence, which cuts through downtown Nogales near the official border crossing, where an abundance of people and goods flow legally every day. Floodlights, drones, ground sensors, and surveillance cameras help US authorities track illegal activity – all part of a surge in manpower and material that mostly came in after 9/11.

Indeed, one longtime lawman in the area remembers the days when just a few dozen agents guarded the largely open expanse between the two cities, known at the time as Ambos Nogales(Both Nogaleses), a name that still evokes a single community despite the wall between them. Now, some 3,700 agents roam the 262 miles of the Border Patrol’s Tucson sector, one of the country’s busiest, that includes Nogales. Nationwide, the Border Patrol grew from 9,212 agents in 2000 to a peak of 21,444 in 2011. The number has dropped slightly since then, to 19,437.

“The strong federal presence has really changed things around here,” says Tony Estrada, sheriff of Arizona’s Santa Cruz County, who has lived in the area for about 70 years.

The wall here has changed, too. It has gone from a simple chain-link fence to a solid corrugated metal barrier to what exists today: an imposing structure of steel slats topped with anticlimbing metal plates. The latest wall, which cost $11.6 million, stretches 2.8 miles and was erected in 2011, just a year before the shooting.

With a varying height of 18 to 30 feet, the barrier is meant to intimidate. Some locals believe it has helped slow down drug smuggling in the heart of the city. But it hasn’t stopped traffickers and unauthorized immigrants from trying to scale it, often successfully. Sometimes, to accomplish this feat, they rely on accomplices on the ground to distract Border Patrol agents by throwing rocks from the Mexican side.

Whether José was involved in any of these activities on that fateful night in 2012 is a matter of intense dispute. The Border Patrol, long known for its secrecy, has shed little light on what led to the shooting. Instead, incident reports from Nogales, Ariz., police officers, who help agents investigate suspicious activity along the border, offer one version of what happened before the gunshots were fired.

At about 11:15 p.m., Officer Quinardo Garcia arrived at an area along the border just west of the downtown port of entry to investigate a report of nefarious activity. He saw two men in camouflage pants and sweatshirts jump from the fence into Arizona. They had large taped bundles strapped to their backs, which he suspected was marijuana.

Garcia chased the suspects on foot but soon lost sight of the men, who vanished in between the houses that line International Street, which runs along the border wall. After Garcia called for backup, Officer John Zuñiga arrived and spotted two men – one dressed in a white shirt, the other in a blue one – struggling to climb the fence to go back into Mexico. He ordered them to get down, but they ignored him.

“I then heard several rocks start hitting the ground and I looked up and I could see the rocks flying through the air,” Zuñiga wrote in his report.

He ran for cover, then heard several shots. “I saw an agent standing near the fence,” he wrote. “I advised communications that gunshots were being fired, and I was unsure where the gunshots were coming from and who was firing them.”

Nearby, still searching for suspects, Garcia also heard the shots. He soon learned that a Border Patrol agent had shot someone who had been throwing rocks in Mexico, he wrote.

Rock attacks, the Border Patrol says, pose a significant threat to agents who must decide in a matter of seconds whether to use lethal force in tense situations that can quickly turn life-threatening. Assaults against agents have been rising in recent years. They totaled 786 in fiscal 2017, compared with 454 in fiscal 2016, according to US Customs and Border Protection (CBP), the federal agency tasked with securing the nation’s borders.

“Our jobs are dangerous, and the decisions we make every day determine if we will return home safely to our families,” the National Border Patrol Council, the union that represents agents, said in a statement after Swartz’s indictment. The group has thrown its support behind Swartz, who is on indefinite suspension from the force.

José’s shooting compounded rising criticism over agents’ use of deadly force rather than a less lethal response in rock attacks and other confrontations. An investigation by The Arizona Republic newspaper found that CBP agents killed at least 42 people – with few repercussions – between 2005 and 2013. At least 13 were Americans. Here in Nogales, a small, hand-drawn mural along the border depicts José, another teenage boy, and four men who were standing on Mexican soil when agents shot them dead between 2010 and 2012.

“There are more than 50 people that have died since 2010 at the hands of the Border Patrol, and no one has been held accountable for it,” says Hiram Soto of the Southern Border Communities Coalition, a group of more than 60 organizations that seeks to strengthen oversight of CBP.

In May 2014, under intense pressure from outside groups, CBP, which oversees the Border Patrol, released a year-old report it had commissioned on its use-of-force policy. After reviewing 67 cases, the Police Executive Research Forum, an outside research group hired to conduct the study, criticized the agency for incidents in which agents opted to shoot at moving vehicles and rock throwers rather than avoid conflict.

The group recommended training that focuses on keeping agents out of the path of vehicles. It also said agents “should be prohibited from using deadly force against subjects throwing objects not capable of causing serious physical injury or death.”

CBP has made public revised rules that emphasize de-escalation tactics and the use of nonlethal devices. In early February, the agency released figures showing a 69 percent drop in use-of-force cases involving firearms, from 55 in 2012 to 17 in 2017.

Daylight had turned to dusk when José’s mother, Araceli Rodriguez, recently turned the corner onto Calle Internacional, the street that runs along the border wall just inside Mexico. She knelt on the sidewalk where her youngest son died, now marked by a shrine, and lit a candle. It’s something she has done on the 10th day of each month since he was killed.

On this night, family members and a dozen friends from the US joined her at the monthly vigil to sing and pray before a white metal cross with a photo of José in the center. Her hair pulled back in a ponytail, Ms. Rodriguez looked weary. Though she’s waited for more than five years for the agent accused of shooting her son to be tried, she knows justice can be elusive.

“It’s taken so long just to get to this point, to decide if the man is guilty or innocent,” says Rodriguez, a single mother. “The truth is that, whatever the circumstances, he killed my son.”

The family lives at the end of a steep cobblestone street, across from an elementary school. Growing up, José played with toy cars and followed his older brother, Diego, everywhere. The two often played basketball with friends at a church just up the hill. His grandmother, Taide Elena, says José was shooting hoops just hours before he was killed.

José was cared for by Ms. Elena and his aunts and uncles after his mother, following a separation from her husband, moved 370 miles away to Navojoa, her hometown, taking her two younger daughters with her.

The day José was shot, Elena says, the two had spent time together in the living room of the hilltop house. They chatted about a variety of topics, including his upcoming transfer to a new high school. José later walked his grandmother to the border crossing so she could return to Nogales, Ariz., where she lives. It was the last time she saw him alive.

The teen never went home that night. The next morning, searching for José, Diego and his aunt saw a photo in a newspaper of someone who’d been shot 30 feet from the border the night before. He was wearing a gray T-shirt, jeans, and gray sneakers that looked just like the ones José’s aunt had recently bought for him.

After José’s death, his mother returned to Nogales, Mexico, and stayed. Since then, she’s led marches, protests, and vigils in a call for justice. Frustrated with the silence surrounding the case, she filed the civil suit in US District Court in Tucson, initially charging the unnamed agents with using “unreasonable and excessive force.” Luis Parra, one of her lawyers on the civil case team, says the DOJ’s subsequent decision to prosecute Swartz represents a vindication for the family.

In August 2014, US and Mexican investigators swarmed the block where José was killed. They cordoned off the crime scene with yellow tape and carefully inspected the sidewalk where the youth had lain nearly two years earlier.

They also took note of the still-visible bullet marks on the walls of the abutting medical building and a nearby surveillance camera posted along the border, on the US side, that had recorded the activity on the night of the shooting.

The lawyer for Swartz says José was hurling rocks at the agents that night and was likely involved in drug smuggling. Rodriguez’s family says the youth was an innocent bystander gunned down while simply walking by, probably on his way to a convenience store.

In the area, the border wall sits on top of a small cliff, about 25 feet high. Throwing rocks over the elevated fence would require someone to make a long, arcing toss, something that supporters of the family say wouldn’t likely hurt anyone on the other side. The rocks that rained down that night hit, but didn’t injure, a dog named Tesko, according to a police report. Yet it is also possible to throw rocks through the slatted openings in the barrier. This is how the bullets were able to travel through the wall.

Witnesses on the Mexican side told DOJ investigators that José was walking down the street, and that other individuals ran past him when the shots were fired, suggesting to them that he wasn’t involved in any reckless activity. For prosecutors, the case isn’t about rock attacks or drugs but comes down to one overarching argument: that the agent wasn’t justified in using deadly force.

The defense, for its part, doesn’t deny the agent shot José, but contends he did so in self-defense. They argue that he felt threatened, and, in the tense circumstances of the moment, made a decision that was justified to protect himself.

In June 2010, a Border Patrol agent shot and killed 15-year-old Sergio Hernandez Guereca while he played with friends on the Mexican side of a culvert between Ciudad Juárez, Mexico, and El Paso, Texas. In a disputed account, Jesus Mesa Jr. said he fired his gun after being pelted with rocks. No charges were filed against him.

Sergio’s family filed a civil suit against Mr. Mesa, and the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals ruled that no legal claim could be pursued against the agent because the youth was a Mexican citizen in Mexico when he was shot. In Jose’s case, a federal judge in Tucson ruled just the opposite – that the case could go forward.

The US Supreme Court then took up the Hernandez case. In June 2017, the high court sent the Texas case back to the lower court without addressing the more profound question of whether constitutional protections extend to foreign nationals outside the US. Instead, the Supreme Court asked the lower court to consider whether the plaintiffs can rely on a landmark 1971 decision, Bivens v. Six Unknown Named Agents of Federal Bureau of Narcotics, that granted individuals whose rights were violated the right to sue federal officials. But the Bivens precedent has never been used in a case beyond US borders.

The potential implications for foreign policy and national security may be one reason the high court avoided the question of constitutional rights for people in other countries, according to Ms. Seo of the University of Iowa law school.

“The situation that a lot of law professors have written about is drone strikes,” she says. “A lot of drones are controlled in the US but are flying in Afghanistan. So if an innocent person in Afghanistan dies from a drone strike and a button was pressed in the US, can somebody in Afghanistan who’s not a US citizen, halfway around the world, sue the US government for damages?”

Paul Bender, a constitutional law professor at Arizona State University in Tempe, says a conviction in the criminal case could help Rodriguez’s civil suit. The Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals will decide if it can go forward. But “I would assume what’s going to happen is if he’s convicted, then they’ll settle the civil case,” he says.

Back at the medical building where Contreras, the doctor, tends to his patients, the bullet holes that long pockmarked the facade have now been patched. In February, a construction worker slathered a skim coat of cement on the wall. He covered the memorial cross to keep it free of debris while he worked.

Inside the building, Contreras sits at his desk. He has watched the endless legal maneuverings over the shooting closely, as have many people on both sides of the border, including in Mexico City and Washington, D.C. Mexico’s government decried José’s killing when it happened. Various authorities from Nogales, Mexico, are expected to testify at the trial – a first in a fatal cross-border shooting.

Contreras leans back in his chair and tilts his head toward the border fence. “We’ll see what kind of justice is done on the American side,” he says. ρ

A thinker who pushed at the limits of human thought

The late theoretical physicist Stephen Hawking inspired people around the globe with his refusal to accept widely accepted boundaries. One admirer from China, where Dr. Hawking was viewed with great reverence, put it this way: "He will roam across the universe and its galaxies, and in the end will again become its brightest star."

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By Amanda Paulson Staff writer

-

Eoin O'Carroll Staff writer

With the passing of Stephen Hawking Wednesday, the scientific world – and all those who are simply fascinated by the universe – lost a shining light. As a theoretical physicist, Dr. Hawking changed how we think of the cosmos. As someone who was diagnosed with a debilitating illness at a young age, he demonstrated that brilliance, curiosity, and humor can transcend physical limitations. One scientist who struggled with mobility issues as a child says that his story taught her that “It doesn’t matter how much your body is failing you. As long as your mind is working you can change the world.” As a science communicator, he brought complex ideas of the universe to a broad audience and inspired an entire generation of physicists. Hawking’s own advice stands as a lasting legacy: “Remember to look up at the stars and not down at your feet. Try to make sense of what you see and wonder about what makes the universe exist. Be curious. And however difficult life may seem, there is always something you can do and succeed at.”

A thinker who pushed at the limits of human thought

Stephen Hawking lived a life that stood in defiance of finality.

In 1963, as a graduate student at Cambridge University, he was diagnosed with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, also known as Lou Gehrig’s disease. His doctors gave him just two years to live.

Instead, Dr. Hawking spent the next half century overturning physicists’ conceptions of black holes. In 1974, drawing on general relativity, thermodynamics, and quantum physics, he found that black holes actually emit radiation at their edges, gradually evaporating over billions of years until they explode. This insight led to the realization that whatever information falls into a black hole will eventually be released. Like a terminal diagnosis, a black hole does not always have the last word.

As a theoretical physicist, Hawking, who died early Wednesday morning, changed how we think of the cosmos. As a science communicator, he brought complex ideas of the universe to a broad audience, and kindled an entire generation of physicists.

“My grandfather gave me a copy of ‘A Brief History of Time’ when I was in junior high,” says Tanya Harrison, a planetary scientist at Arizona State University in Tempe, referring to Hawking’s 1988 bestseller about the origin and evolution of the cosmos. “That solidified it.”

A year or two later, at the age of 13 or 14, she began to have trouble walking and standing. “It was starting to affect my ability to do things I had done for a long time, like dancing and sports,” she says. “Seeing Stephen Hawking pursue theoretical physics and be a professor while not being able to move – that was really inspiring for me.”

Hawking embraced his status as a role model to others with physical disabilities. According to Time magazine, wherever Hawking traveled – he visited every continent, including Antarctica – he would ask his hosts to arrange an unpublicized meeting with children with disabilities. But his influence extended far beyond the disabled community.

“I think anybody you talk to in any field of science remotely related to space or physics and people will probably cite him as one of their big inspirations,” says Dr. Harrison.

Even as he lost physical mobility, he never ceased to counsel optimism.

“Remember to look up at the stars and not down at your feet,” he famously said, in a speech marking his 70th birthday. “Try to make sense of what you see and wonder about what makes the universe exist. Be curious. And however difficult life may seem, there is always something you can do and succeed at. It matters that you don’t just give up.”

Hawking’s preoccupations extended far beyond theoretical physics. He forcefully opposed the US-led invasion of Iraq in 2003, which he labeled a “war crime,” and he championed Britain’s National Health Service, which he credited with keeping him alive.

Hawking also showed a deep concern about the long-term future of humanity, warning that ecological collapse, the rise of artificial intelligence, or even contact with hostile aliens could bring humanity to a premature end. To avoid extinction, he argued, humanity must colonize other worlds within the next 1,000 years.

“I think his biggest contribution was to show you could think boldly about things most physicists would be reluctant to tackle, partly because they seem too far out,” says retired science writer Bob Cowen, who covered science for The Christian Science Monitor for 45 years.

Hawking also enjoyed a celebrity status rare among scientists, with guest appearances on some of television’s most acclaimed series: “Futurama,” “The Simpsons,” and “Star Trek: The Next Generation.”

“It’s hard to imagine anyone who has been more successful at not only pursuing an academic research career of enormous significance but [who] also has made such an imprint on the popular understanding of science, and even through popular culture,” says former Monitor science writer Pete Spotts. “He had a zest and zeal for what he did and that, for me personally, was as inspiring as the hard science he produced.”

This vigor – traveling through the cosmos in his mind, and diving into complicated cosmological problems with the same zeal with which he embraced pop culture – flew in the face of his physical limitations.

“Watching Stephen Hawking and the fact that he was able to do so much even as his disease was getting worse – it really resonates with me,” says Harrison. “It doesn’t matter how much your body is failing you. As long as your mind is working, you can change the world.”

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Why web users are ‘norm entrepreneurs’

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By The Monitor's Editorial Board

When the inventor of the World Wide Web asks users to “work together” to prevent the internet from being “weaponized” to spread false information, he’s really asking them to become “norm entrepreneurs” and reestablish a respect for truth, transparency, and accountability. Tim Berners-Lee – who did so in a letter published Monday on the website of the World Wide Web foundation – is hardly alone. US security officials, as they try to come up with a “cyber doctrine,” also assume Americans can educate themselves about their role in discerning the truth. The more people see “heavy-handed” manipulation of news and also talk about this problem, says Army Lt. Gen. Robert Ashley, director of the Defense Intelligence Agency, “the more people may question the information that they see that’s out there.” Daniel Coats, director of national intelligence, goes even further. “Our job as an intelligence community is to inform the American people of this [issue] so that they ... exercise better judgment in terms of what is real news.” When the web’s inventor asks for help in fixing the web, he does not assume most people are dupes or victims of their own gullibility. There’s nothing fake about each person’s capability to sift fact from falsehood. Any proposed rule, regulations, or strategy about the web must start from that premise.

Why web users are ‘norm entrepreneurs’

The inventor of the World Wide Web, British computer scientist Tim Berners-Lee, issued a special plea this week on the 29th anniversary of his creation. In an open letter, he asked web users to “work together” to prevent the internet from being “weaponized” by countries or corporations and used to spread false information.

In the web’s early days, entrepreneurs like Dr. Berners-Lee set the norms of the Digital Age. They championed the web’s open access to vast knowledge. But as cyber risks have spread, such as Russian meddling in other nations’ politics, web users now face the challenge of setting the standards.

In effect, they must become “norm entrepreneurs” and reestablish a respect for truth, transparency, and accountability in each encounter on the web.

Berners-Lee is hardly alone in asking individuals to become more responsible for their thinking and actions. In the United States, the White House is under pressure from Congress to devise a grand strategy for all aspects of cyberspace. In early March, a bipartisan group of senators wrote to President Trump: “Our increased reliance on the internet has created new threats and vulnerabilities to our nation’s infrastructure and our way of life.” They demanded a “cyber doctrine” for the US.

One reason for the delay is a dispute among security officials over how and when to respond to a cyberattack. A US counteroffensive against another Russian misinformation campaign, for example, might ignite an endless string of retaliatory actions. There might be no winner in such a war.

Yet just as important, say top security officials, is that Americans educate themselves about their role in discerning the truth in what they read and share on the web. The more people see “heavy-handed” manipulation of news and also talk about this problem, says Army Lt. Gen. Robert Ashley, director of the Defense Intelligence Agency, “the more people may question the information that they see that’s out there.”

Daniel Coats, director of national intelligence, goes even further. “Our job as an intelligence community is to inform the American people of this [issue] so that they ... exercise better judgment in terms of what is real news.”

Government can do only so much, he adds, because “the democratization of cyber capabilities worldwide has enabled and emboldened a broader range of actors to pursue their malign activities against us.” It is not only states such as Russia, North Korea, and Iran that worry the US. “Nonstate actors can be just as capable now as state actors,” says Michael Sulmeyer, a cyber expert at Harvard University.

Web consumers are on the front line of protecting today’s web. “I believe the biggest risk we face as Americans is our own ability to discern reality from nonsense,” wrote Steve Huffman, co-founder of the content-sharing website Reddit, in a message this month. “I wish there was a solution as simple as banning all propaganda, but it’s not that easy.”

With so much information available, web users are being forced to better scrutinize the reputation of information sources – and do so with patience rather than speed. In a 2017 survey by the Barna Group, 39 percent of Americans said they trust news reporters as credible sources while 36 percent said they verify reports by comparing multiple sources. Nearly a third said they trust nobody, only their own instincts. And 27 percent trust family and peers to help them determine if information is reliable.

When the web’s inventor asks for widespread help in fixing the web, he does not assume most people are dupes or victims of their own gullibility. There’s nothing fake about each person’s capability to sift fact from falsehood. Any proposed rule, regulations, or strategy about the web must start from that premise.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Redeeming ‘thoughts and prayers’

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 4 Min. )

-

By Michelle Boccanfuso Nanouche

Today’s column explores how an openness to God as infinitely good can lift our “thoughts and prayers” to be more than just words – supporting and inspiring efforts to meet the world’s challenges.

Redeeming ‘thoughts and prayers’

Following recent tragic events such as the shooting in Parkland, Fla., commentary denouncing “thoughts and prayers” has spread through print, visual, and social media. Critics claim that the condolence is used by many as empty words to replace corrective action. And indeed, the phrase certainly shouldn’t be used as an excuse for inaction.

I’ve seen, however, that “thoughts and prayers” can go well beyond simple words. If that “thought” is dedicated to practical solutions, it can support and inspire action that brings tangible progress – especially when there is an openness to the boundless resources of divine intelligence and good.

Our innermost desires influence what we say and do, consciously or unconsciously. I have been learning that every thought we think, if it represents a genuine desire for good, is actually a prayer. In “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” Monitor founder Mary Baker Eddy explained: “Desire is prayer; and no loss can occur from trusting God with our desires, that they may be moulded and exalted before they take form in words and in deeds” (p. 1).

Seen in this light, every heartfelt desire for healing, comfort, peace, and safety is a noble, generous, and loving prayer. But if the truth be told, some desires can be misguided, undermined by self-interest, anger, greed, or bias, impeding progress. “The things that come out of the mouth come from the heart,” Christ Jesus once said (Matthew 15:18, International Standard Version). Jesus prayed deeply, humbly, from a pure heart – with the highest and best motives – for himself and others that all might experience God’s infinite, healing love. Today humanity still cries for the depth of thought and humility that heals.

I’ve learned through my study and practice of Christian Science that every thought, every desire, can be lifted up and exalted. Christian Science describes God as the universal divine Mind. Everything this infinite Mind knows – including each of us, in our true identity as God’s creation – is spiritual and good, because that’s the nature of God.

This radical way to think about God and each other offers a powerful basis for hope, progress, and healing. From this divine source of good flows unlimited intelligence, wisdom, and the inspiration necessary to meet even the most discouraging challenges. However it may seem on the surface, no one is excluded from this spiritual goodness. We all have the ability to humbly let divine Mind, God, lift us up. This gives courage, counters fear, and provides mental stability. It invites God’s redeeming and transforming light to penetrate and destroy thoughts of darkness, fear, or hopelessness.

When hurricanes hit Florida, Texas, and Puerto Rico in rapid succession last year, an acquaintance of mine felt overwhelmed by the news reports. She also lived far away and couldn’t see what contribution of value she could make. Seeking hope and clarity, she prayed.

She told me that her prayers brought her the assurance that divine good is present, is the spiritual reality, even in the midst of what seems to be total loss. And she realized that the comfort and peace she felt as a result of her prayers were available to every person impacted by the hurricanes too, because God is the source of unstoppable good, and God’s love is present everywhere.

Later that day, my friend had a modest but encouraging opportunity to express that love in a tangible way. She happened to notice a post on Facebook about a particular family in need. She realized that she had in her home exactly what would meet the need, and took the necessary steps to share it with the family.

To me this is a simple example of how lifting one’s thought in prayer to the fact of God’s ever-present goodness for all of us, His spiritual creation, can open the way for a spiritual sense of love, peace, and inspiration, even when we’re feeling overwhelmed by the human need. And sometimes this can include opportunities to take specific, appropriate action.

Jesus didn’t offer hollow prayers when confronted with human needs. His prayers were substantial and effective. They comforted and healed. He didn’t settle for partial progress. In the case of a blind man who appeared to be only partially healed through Jesus’ initial treatment, Jesus persisted in helping him “look up” until his sight was fully restored (see Mark 8:22-25). Underlying all of Jesus’ prayers was the universal truth that God, Mind, is the ever-present source of all good. This spiritual fact upholds healing prayer today.

A hymn in the “Christian Science Hymnal” says:

O Light of light, within us dwell,

Through us Thy radiance pour,

That word and deed Thy truths may tell,

And praise Thee evermore.

(Hymn 226, Washington Gladden)

Humility that opens our heart to God’s healing light, and a willingness to let divine wisdom lead us, can redeem our desires, thoughts, and prayers. This in turn inspires our words and deeds in ways that bless practically, while also embracing those in need in a spiritual sense of God’s ever-present care for them.

A message of love

Seeking to school Congress

A look ahead

Thanks for joining us today. Tomorrow, we'll look at how Congress is rolling back regulations in the banking industry, while in the private sector, many companies are trying to increase regulation in the name of what they call employees' "best interests."