- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- Kavanaugh hearings: Amid new charges, a call for humanity, open minds

- Why Rouhani, facing political storm in Iran, is secure in face of US threats

- Afghans, Iraqis who aided US troops see a welcome mat removed

- With an eye on rising rents, cities start to regulate the gig economy

- Community, in harmony: behind a wave of ad hoc choirs

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

A new view of marriage

Mark Sappenfield

Mark Sappenfield

Marriage has been subject to many revisions over the years. For millennia, it offered stability (and sometimes love) but essentially enshrined inequality. With the 20th century came the baby boomer divorce spike and then, in this century, the rise of same-sex marriage. But a new report on marriage suggests a different kind of change is now taking shape that may be subtler than these past convulsions but perhaps even more profound.

The divorce rate in the United States declined 18 percent from 2008 to 2016, according to University of Maryland sociologist Philip Cohen. The reason is essentially twofold: First, younger Americans are getting divorced less than their boomer parents. And second, Americans with less than a college education – the group most prone to divorce – are cohabiting more and marrying less.

The first trend is good; the second isn’t. Cohabiting is not as stable as marriage, and broken relationships point to many negative outcomes for families and society. Yet within both trends is a single thread: a greater appreciation of the higher and deeper reasons for marriage.

The clear yearning is for a stability based on equality, responsibility, and mutual respect, not merely romantic love or financial necessity. Mr. Cohen’s data show not only that this is possible but where our focus is most needed to spread this stability more widely.

Now, on to our five stories for today, including insight into Iran’s resilience to sanctions, a different view national service, and the joy of singing together.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Kavanaugh hearings: Amid new charges, a call for humanity, open minds

As explosive new allegations emerged against US Supreme Court nominee Brett Kavanaugh, there are signs that many Americans don't trust either side’s narrative. They’re trying to decide for themselves.

Even before today’s revelations of a third woman accusing Supreme Court nominee Brett Kavanaugh of sexual misconduct as a teen, 60 percent of Americans said they planned to watch Thursday’s planned Senate Judiciary Committee hearing with Mr. Kavanaugh and the first woman to accuse him of assault, Christine Blasey Ford. Both sides are accusing the other of playing partisan politics and toying with people’s lives in the name of brinkmanship. The outcome remains uncertain, and the political risks for both sides could not be higher, with both the balance of the Supreme Court and the looming midterms. Arizona Republican Sen. Jeff Flake, a “never Trumper” who sometimes serves as the conscience of conservatism in the Senate, spoke on the Senate floor of the humanity of the two witnesses scheduled to appear at Thursday’s high-stakes hearing – both of whom have received death threats, as has Senator Flake. “We sometimes seem intent on stripping people of their humanity so that we might more easily denigrate or defame them…. We seem sometimes even to enjoy it,” he said. He urged his colleagues to have “open minds,” listen, and “seek the truth in good faith.”

Kavanaugh hearings: Amid new charges, a call for humanity, open minds

Over the past week and a half, the course of Judge Brett Kavanaugh’s Supreme Court nomination has gone from a glide path to something that resembles a roller coaster.

Wednesday morning, that roller coaster went into a vertical drop.

Michael Avenatti – the lawyer best known for representing adult film star Stormy Daniels in her suit against President Trump – released a sworn affidavit from a woman alleging that she saw Mr. Kavanaugh and other boys “spike the punch” with drugs or grain alcohol at house parties in the 1980s so that girls could be “gang raped” by a “train” of boys. The woman, Julie Swetnick, says she has a “firm recollection” of Kavanaugh and other teenage boys “lined up outside rooms at many of these parties waiting for their ‘turn’ with a girl.” She says she herself was “gang raped” at such a party where Kavanaugh was present, after being drugged, she believes, with Quaaludes or something similar.

Kavanaugh called the allegations “ridiculous and from ‘The Twilight Zone.’ ” In a statement, he said: “I don’t know who this is, and this never happened.”

Even before Wednesday’s revelations, 58 percent of Americans said they planned to watch Thursday’s planned Senate Judiciary Committee hearing with Kavanaugh and the first woman to accuse him of sexual misconduct as a teen, Christine Blasey Ford. As of this morning, more Americans were unsure whom to believe – 42 percent – than the roughly one-third who believe Dr. Ford and the quarter who believe Kavanaugh, according to a new poll from NPR, “PBS NewsHour,” and Marist University. Both Republicans and Democrats are accusing the other of playing partisan politics and toying with people’s lives in the name of brinkmanship. The outcome remains uncertain, and the political risks for both sides could not be higher, with both the balance of the Supreme Court and the looming midterm elections.

In the Senate, the tension is palpable.

On Wednesday morning, reporters swarmed around Senate Judiciary Committee member Orrin Hatch (R) of Utah, eager to ask him about the latest confirmation bombshell.

Senator Hatch’s spokesman kept trying to move the towering octogenarian along, telling him he was late, as reporters peppered him with questions. “Everybody shut up!” Hatch barked, standing still to speak with the reporters. Then adding, “I’m not in a good mood.”

Later, Arizona Republican Sen. Jeff Flake, a fellow Mormon and “never Trumper” who sometimes serves as the conscience of conservatism in the Senate, cut through the tense atmosphere. In a speech on the Senate floor, he reminded senators of the humanity of the two witnesses who are scheduled to appear at Thursday’s high-stakes confirmation hearing – both of whom have received death threats, along with Senator Flake.

“We sometimes seem intent on stripping people of their humanity so that we might more easily denigrate or defame them, or put them through the grinder that our politics requires. We seem sometimes even to enjoy it,” he said. He urged his colleagues to have “open minds,” listen, and “seek the truth in good faith.”

But he did not go so far as to call for an investigation of allegations, which now include three women, nor did he suggest postponing Thursday’s hearing or even withdrawing the nomination of Kavanaugh – all of which Democrats demanded in light of snowballing accusations against Kavanaugh in his high school and college years.

Ms. Swetnick’s statement does not implicate Kavanaugh in her own alleged rape. She writes that, at more than 10 parties between 1981 to 1983, she observed Kavanaugh and his friend, Mark Judge, “drink excessively and engage in highly inappropriate behavior, including being overly aggressive with girls and not taking 'No' for an answer. This included the fondling and grabbing of girls without consent.”

Republicans have been quick to point out that her lawyer, Mr. Avenatti, has political motivations. “Seems to me he wants to protect people involved in pornography, and he’s running for president,” Sen. Chuck Grassley, the chair of the Judiciary Committee, commented.

But Senator Grassley went on to say that what’s important here isn’t the lawyer, but “the woman who says she’s been harmed.”

“We have had accusation after accusation. Very few of them, if any, corroborated,” Grassley told reporters. “Our lawyers are on [this latest allegation] right now, our staff investigators. I can’t say anything until they get done.”

On Wednesday evening, President Trump called the allegations against Kavanaugh “a big, fat con job” in a press conference, praising Kavanaugh as “one of the highest-quality people that I’ve ever met.” Of the accusations, he said, “These are all false to me.... These are all false accusations in certain cases. What they’ve done to this man is incredible.” He added that he remained open to “changing my mind” depending on the testimony Thursday.

The challenge, of course, is that Republicans are looking at a ticking clock. The Supreme Court begins its term Monday, and Republicans had originally hoped to seat Kavanaugh by then. Grassley had planned a committee vote for Friday morning, after Thursday’s scheduled hearing – then a vote of the full Senate early next week.

But each new allegation imperils that schedule, and perhaps the nomination itself – potentially causing the holy grail of a majority-conservative court to slip through Republicans’ hands.

In a narrowly divided 51-to-49 Senate, where Republicans have only the barest majority, each new accusation makes it difficult for any Democrat to support Kavanaugh, says Nathan Gonzales, editor and publisher of the independent Inside Elections. That puts the focus on Republicans, who have very little room for error. Republican Sens. Flake, Susan Collins of Maine, and Lisa Murkowski of Alaska are undecided.

On Monday, Senator Murkowski told The New York Times that the issue was no longer whether Kavanaugh was qualified, but “whether or not a woman who has been a victim at some point in her life is to be believed.” In her home state, the governor, lieutenant governor, and the Alaska Federation of Natives have all declared against Kavanaugh.

There’s risk to plowing ahead, notes Mr. Gonzales, “but some Republicans believe that the short-term risk is worth the long-term benefit of having someone with his philosophy on the court for a lifetime.”

But Democrats, too, carry a risk. Sens. Heidi Heitkamp of North Dakota, Joe Manchin of West Virginia, and Joe Donnelly of Indiana – who all voted to confirm Mr. Trump’s first Supreme Court nominee, Neil Gorsuch – are all endangered Democrats seeking reelection in states that Trump won handily. “As long as the president is supportive of Kavanaugh … they are at some risk,” Gonzales says.

That’s not how Dianne Bystrom sees it. The sexual-assault allegations “really do give cover to those Democrats in red states,” says the director emerita of the Carrie Chapman Catt Center for Women and Politics at Iowa State University in Ames, Iowa.

These allegations are coming at the time of the #MeToo movement, bringing with it heightened sensitivity to sexual harassment and assault. That was underscored in a week in which comedian Bill Cosby was sentenced to prison for sexual assault.

Take Kathleen Harlow, a music professor at Berklee College of Music in Boston, who remembers the Anita Hill hearings and has been watching the Kavanaugh nomination process closely. The #MeToo movement is putting pressure on institutions, including her own, to tackle a culture of sexual harassment that had been brushed under the carpet, she says. Berklee said last year it had fired 11 faculty members for assault and harassment, a fact it initially kept quiet.

Society hasn’t fully reckoned with the issue of sexual abuse, says Professor Harlow, speaking before Wednesday's fresh round of allegations. “The demand for it has. But I think that it is one of the conversations that will define this country at this point.”

Women voters are expected to make the difference in this year’s midterm elections, Ms. Bystrom says, and she expects them to be even more energized by the Kavanaugh nomination. A pattern is beginning to emerge in the allegations that many women will recognize, she says. “These stories are consistent with someone who drank too much and participated in behavior that many young men participated in at that time.”

Other analysts say it’s simply impossible to know how the allegations and the Kavanaugh nomination will play out politically. The news cycle is now so compressed, it’s hard to know what will be salient weeks from now, when voters go to the polls.

“Is this the defining thing in early November? I just don’t know,” says Kyle Kondik, managing editor of Sabato’s Crystal Ball.

The uncertainty – and the enormous political stakes – are the reason for the tense atmosphere in the Senate. Will Kavanaugh survive? Will Democrats retake the Senate? Will Republicans have to try with a new nominee in the lame duck session?

No one knows. But Flake stated the obvious on the Senate floor: However the vote goes, “I’m confident in saying it will forever be steeped in doubt.”

Staff writer Rebecca Asoulin contributed to this report from Boston.

Why Rouhani, facing political storm in Iran, is secure in face of US threats

The US sanctions on Iran are intended to create a domestic crisis, and they will cause hardship. But the Iranian regime is well versed in managing internal strife.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Iran’s president, Hassan Rouhani, was first elected by promising to engage the West, lift nuclear sanctions, and improve the economy. Signing the 2015 nuclear deal with the United States and its partners was a signature accomplishment, but Mr. Rouhani has since faced rumblings of discontent that the promised benefits were never realized. Now, after President Trump withdrew from the deal this past spring and reimposed economic sanctions, those grumblings have morphed into a storm of political discontent. Rouhani, who addressed the United Nations on Tuesday, is facing criticism from all sides at home, including his own party. But whether he is vulnerable to US pressure remains to be seen. “Rouhani knows well that there is not an alternative to him,” says Nasser Hadian, a political scientist at Tehran University. “Not the conservatives, not the supreme leader, not the reformists, and surely not the pragmatists of his camp. They all know they don’t have a better alternative. Society is very much upset; they have a lot of legitimate concerns. But I think they are not sure of the alternative,” he says, adding that talk of “regime change” among some US officials is just “wishful thinking.”

Why Rouhani, facing political storm in Iran, is secure in face of US threats

President Hassan Rouhani of Iran stood before the United Nations this week under intensified pressure from the United States, which is seeking to isolate the Islamic Republic and leverage the pain of increased sanctions and antigovernment anger to curb what it says are Iran’s “malign activities” in the Middle East.

Iranians have felt the American surge of anti-Iran hostility since President Trump withdrew from the 2015 nuclear deal last spring and began restoring crippling sanctions, which analysts say hastened the plunge of Iran’s currency and helped make prices soar.

But for Mr. Rouhani, White House threats over Iran’s “aggression” barely register. Even as he faces his own perfect storm at home of political infighting and widespread discontent, analysts say, his position is secure.

To be sure, Iranians say they are disillusioned with their politics and politicians like never before, using the term “hopeless” repeatedly as they speak of the scale of corruption and mismanagement that corrodes their daily lives, and their fear of more sanctions.

Yet even though Rouhani has become a favorite target inside Iran – as well as from within his own centrist “Hope” faction – the roots of popular dissatisfaction are diverse, often longstanding, and, Iranians say, very unlikely to lead to his downfall.

“Rouhani knows well that there is not an alternative to him,” says Nasser Hadian, a political scientist at Tehran University. “Not the conservatives, not the supreme leader, not the reformists, and surely not the pragmatists of his camp. They all know they don’t have a better alternative.

“Society is very much upset, they have a lot of legitimate concerns. But I think they are not sure of the alternative,” says Mr. Hadian, adding that talk of “regime change” among some US officials is just “wishful thinking.”

He says that two assumptions about Iran made by some in the White House are incorrect: that the Iranian state is weak, and that Iranians are ready to remove it. Instead, he says the state “is fully in charge, fully in control, and can easily suppress.”

“Rouhani is confident that this perfect storm may not be all that perfect,” says Hadian. “He thinks if he can survive a few months … that pressure will be substantially less.”

Fear about the future

The optics in Iran have given a different impression, when weeks of protests swept across the country at the start of the year. Ever since, frequent industrial strikes and other protests have taken place, as layoffs spread, the economy tumbled, and many of Rouhani’s election promises failed to materialize.

“People here are very uncertain about their future. And how long can this drag on?” asks a former journalist who asked not to be named.

“Politicians … have no answers for such questions,” he says. “When there was a war with Iraq, we knew, one way or another, it was going to end. But what about now? Is the US going to no longer be a superpower? I don’t think so.”

“Everybody understands this, and it puts a lot of negative psychological pressure on people,” he says.

Coping has been hard, especially after the high expectations for prosperity created by the nuclear deal, which Iran has adhered to. And even as Rouhani has been attacked from all points of Iran’s political spectrum, there has been infighting within both conservative and reformist wings.

Exhibit A is a biting critique from within the president’s own “Hope” faction. In a blistering speech to parliament this month, lawmaker Parvaneh Salahshouri laid down a host of criticisms of government performance, charging that Rouhani was denying Iran was in crisis when “everyone knows” otherwise.

Ms. Salahshouri said she wanted to complain to clerics “about the oppression against our people,” but found they were more worried about women covering their hair and biking, “rather than focusing on corruption, poverty, and the reasons why young people escape from religion.”

In an interview, Salahshouri, who has a PhD in sociology, says, “People had expectations much higher than what Rouhani could deliver.” Despite a chorus of criticism over her speech – as well as much support – she says institutions such as the Guardian Council, which vets candidates running for office, have already begun to react to her recommendations.

“This is the beginning … it was a wake-up call so that they would be more responsive,” says Salahshouri. Iran is dynamic and in a state of “continuous reform,” she says, so there is optimism despite what she calls “mega-challenges.”

“We’re living in a society where people may seem to be hopeless or losing hope,” she says, “but even little things like my speech give them this excitement and reason to live on and still fight to make it better.”

Overcoming mistrust

Some Iranians say the current lack of trust is decades in the making and will be hard to overcome.

“This is an accumulation of all the bad things this ruling system has done to people, to women, to students, to artists, to filmmakers, including sending basiji [militias] into the streets” to crack down on post-election protests in 2009, says a veteran analyst, who also asked not to be named.

“All this was depriving people of even the smallest thing to let people be happy,” says the analyst.

Yet he adds that the same arguments about whether Iran’s revolutionary rulers could solve Iran’s problems were raised 10, 20, and 30 years ago, during moments of crisis. He dismisses chances of an uprising.

“This has happened before, and at the last moment this regime has found an ability to be flexible,” he says, citing the 1988 end of the Iran-Iraq war; the 1997 election of the reformist President Mohammad Khatami; and the nuclear deal, which witnessed Iranian officials shake hands and negotiate with its American arch-foe – all of them unexpected events that helped relieve popular discontent.

The next round of US sanctions is due to begin Nov. 4, aimed at stopping Iranian oil sales. They “definitely will cause protests and dissatisfaction,” says Hossein Shariatmadari, the editor of the hard-line Kayhan newspaper.

“This is very normal when people feel inflation, they become stressed and worry,” says Mr. Shariatmadari. But he says it is also a “good thing that Trump and [national security adviser John] Bolton keep threatening us: People realize the aggression comes from that side, so the reaction is toward them, and not the government.”

Need for transparency

And yet Iran’s social divide remains wide, and appears to be fracturing further, as economic and social pressures mount.

“Our own experience is, if there is a difference between the government and the people, we will be defeated,” says Mahdi Rahmanian, managing director of the reformist Shargh newspaper, adding that, “we should have the people behind the ruling system [Islamic Republic].”

The only way forward for the government, he says, “is to talk transparently with people and fight corruption. This has started.”

One professional, who asks not to be named, says Iranians in the past 20 years had both reformist and hard-line presidents, and now a centrist who had also “failed” and was the “end of the line.”

“There is no alternative, and Iranians don’t know what they want,” says the professional. He says his father cheered the protests earlier this year, safely at home in front of his TV. But when the son said he wanted to go out, his father tried to stop him.

“Ninety-five percent of Iranians want to be alive to see the future,” says the professional. In Tehran, at least, the protests were limited to a very small area, he recalls. Just ten strides away from the protesters, across the street, young couples could be found flirting with each other on park benches.

“What revolution happens when just 20 or 30 meters of the street is on fire, and the rest of the city is living like normal?” he asks. “Which revolution?”

Afghans, Iraqis who aided US troops see a welcome mat removed

At what point does service to a country qualify that person for citizenship? A change in policy toward interpreters who worked with American troops abroad is raising that question.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

Congress created the first of three special immigration visa (SIV) programs in 2006 to enable Afghans and Iraqis who worked beside US troops and civilians to immigrate to America. The United States has since accepted more than 70,000 SIV recipients from Afghanistan and Iraq, providing them and their families an escape from the shadow of retaliation looming over interpreters, translators, and others in similar positions. But under President Donald Trump, admissions have plunged by almost half in the past two years. “The Afghan people work faithfully with the Americans at great risk to themselves, and the US has turned its back on them,” says Jawad Khawari, who served as an interpreter in Afghanistan and resettled in California in 2016. Former Army Capt. Matt Zeller, co-founder of a nonprofit that works to bring Afghan and Iraqi interpreters to America, predicts that the drop in SIV admissions will lead to fewer people in war-torn countries assisting American forces, hurting efforts to gather intelligence. “It’s going to get people killed,” he says. “And not only Afghans, Iraqis, and their families, but US troops.”

Afghans, Iraqis who aided US troops see a welcome mat removed

The bomb exploded beneath the armored truck on a dirt road in southern Afghanistan. Jawad Khawari recalls staggering from the mangled vehicle with four or five US Army soldiers. They carried one American, the truck’s gunner, clear of the wreckage. He had taken his last breath.

Mr. Khawari, an Afghan serving alongside US troops as an interpreter, suffered a concussion and temporary hearing loss in the blast in 2010. Some months later, on another mission, he was shot in the leg. He considered his injuries the cost of pursuing peace in his homeland.

He signed up for the role and the risk as a 19-year-old in 2009, eight years after American forces invaded Afghanistan and toppled the Taliban in response to the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001. A close friend’s death in a suicide bombing instilled in the teenager a sense of duty.

“I didn’t want to see any more innocent people dying like that,” says Khawari, who embedded with American troops for three years before joining the US Agency for International Development as a training specialist. “So I decided to help the US military mission and try to reduce the tragedy and violence.”

His choice imperiled loved ones. His father received a letter from the Taliban threatening to kill Khawari, his parents, and his siblings if he continued assisting the US government. Khawari persisted against his father’s wishes. Yet he realized that, for his safety, he would need to leave Afghanistan if granted the chance.

He applied for a special immigration visa (SIV) that allowed him and his wife to resettle in a suburb of Sacramento, Calif., in 2016. Congress created the first of three programs under the SIV umbrella in 2006 to enable Afghan and Iraqi citizens who worked beside US troops and civilians to immigrate to America. The visas provide an escape from the shadow of retaliation looming over interpreters, translators, security officers, and others who served in support roles.

The United States has accepted more than 70,000 SIV recipients, including the spouses and children of those who aided the US war effort in Afghanistan and Iraq. But as part of new immigration and refugee restrictions under President Trump, the program’s admissions have plunged by almost half in the past two years.

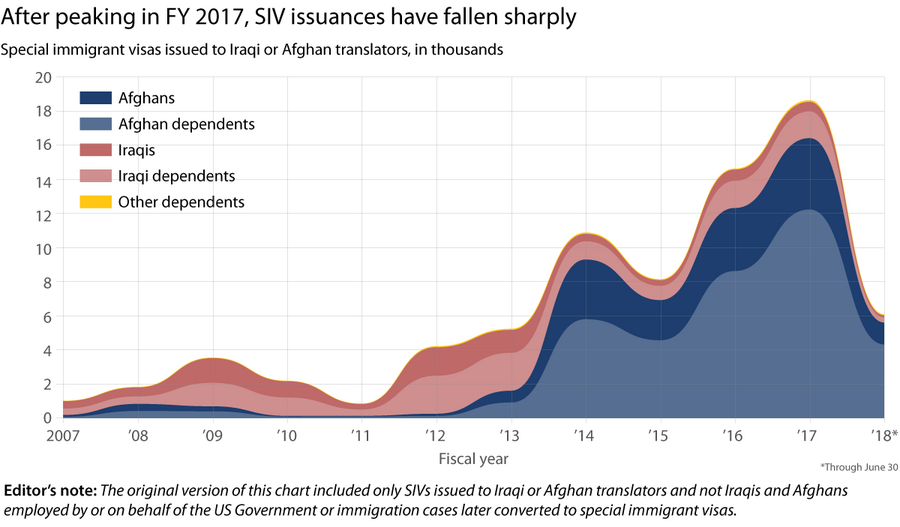

The US State Department reported that 19,321 Afghans and Iraqis arrived between October 2016 to September 2017. For the fiscal year that ends Sunday, the figure had fallen to 10,079 as of this week.

The drop dismays Khawari and other recent SIV immigrants and riles advocates who contend the administration has enacted a short-sighted strategy that will yield long-term harm. Former Army Capt. Matt Zeller, the co-founder of No One Left Behind, a nonprofit based in Virginia that works to bring Afghan and Iraqi interpreters to the United States, calls the policy change “an absolute betrayal.”

“It’s going to get people killed,” says Mr. Zeller, who credits his Afghan interpreter with saving his life during a firefight with Taliban militants in 2008. “And not only Afghans, Iraqis, and their families, but US troops.”

Trapped in SIV limbo

The decline in the number of Afghans and Iraqis settling in California under the SIV program parallels the national trend. The state accepted 3,621 Afghans and Iraqis through Sept. 24, compared with 6,738 last fiscal year.

California has welcomed 21,000 SIV holders since 2006, the most of any state, with 90 percent arriving from Afghanistan. More than a third moved to Sacramento County, making it the nation’s largest diaspora of Afghan SIV recipients.

Federal officials have linked the overall decrease to intensified vetting of immigrants and refugees. In the view of Karen Ferguson, executive director of the Northern California chapter of the International Rescue Committee (IRC), one of the country’s primary resettlement groups, the Trump administration has reneged on a moral obligation.

“The only way Afghans and Iraqis can apply for the special immigration visa is to work with US troops or civilians, and that’s how they end up a target of violence,” Ms. Ferguson says. “If we’re going to have a program that literally puts people in the crosshairs, then we should be responsible for their safety.”

Khawari and his wife traveled to California two years ago with three suitcases and a sense of hope. The uncertainty felt mild in contrast to his last years back home, when he moved every few months and limited visits to his parents to once or twice a year to avoid detection by the Taliban.

“This change in the visas is painful to me. The Afghan people work faithfully with the Americans at great risk to themselves, and the US has turned its back on them,” says Khawari, who waited four years to receive his SIV. “By not giving them visas, a lot of really, really good people are being left behind. Maybe they will survive. But I know I couldn’t live in Afghanistan anymore.”

Wahidullah Rasuli echoes that worry for his friends trapped in SIV limbo. He served as an interpreter for US troops and civilians for six years starting in 2010. For 18 months after quitting, he never left his native Kabul, fearing the Taliban would hunt him down if he traveled beyond the capital. Last December, when the State Department granted his visa following a three-year delay, he immigrated with his wife and their 9-month-old daughter to Sacramento.

“My friends are in danger and their families are in danger,” says Mr. Rasuli, who works in technical support for a phone company. “They are waiting so long for visas, now they are wondering why they helped the Americans.”

The backlog of SIV applicants stranded in Afghanistan and Iraq has swelled to more than 100,000. Zeller predicts that, with the chances of acquiring a visa reduced, fewer people in those and other countries where the US military has deployed troops will choose to assist them.

The diminished cooperation will hurt efforts to gather intelligence on enemy fighters, he adds, a concern that Pentagon personnel and dozens of federal lawmakers have raised in recent weeks. Zeller has emphasized the same point in his own exchanges with officials, and he asserts that as they offer national security as a rationale for enhanced vetting, the SIV bottleneck subverts that precise aim.

“This is a national security issue in that it increases the risk for US troops,” he says. “The number of Americans who will die in ongoing and future wars because of this should haunt these people in the administration for the rest of their lives.”

‘People want to help’

Ahmad Ghory knew he needed to escape Afghanistan after Taliban militants attempted to kidnap his two young sons as they played outside one afternoon in 2011. He praises the quick actions of Kabul police officers for preventing the boys, then ages 3 and 5, from forever vanishing from his life.

Mr. Ghory had worked for the State Department as a transportation manager for almost a decade at that point. The next year, after receiving special immigration visas, he and his wife brought their children to Sacramento, where he found a job as a caseworker with the IRC.

He helps Afghan immigrants acclimate to California and navigate its bureaucratic maze, whether applying for jobs and apartments, obtaining a driver’s license, or filing tax forms. He provides advice on transportation options, grocery stores, and Afghan restaurants, and he reassures them that they will regain their emotional balance in time. The work at once sustains his bond to Afghanistan and deepens his gratitude to America.

“When you come from another country and culture, it is a big adjustment,” Ghory says. “You don’t know who to trust or how you will be treated. But it is lucky to be in California. The people here seem to understand immigrants.”

Mr. Trump has limited refugee admissions to 30,000 for the upcoming fiscal year. The figure marks the lowest total imposed by a president since the country launched a resettlement program almost 40 years ago, dropping from 45,000 this year and 85,000 in 2016.

The president’s hardline stance on immigration and the rhetoric of anti-immigration activists has led the IRC to add a tutorial for recent arrivals that explains their rights if law enforcement officials — or civilians — ask for their visa paperwork.

Amid the cultural friction and sporadic attacks on immigrants, Ferguson, with the IRC’s Northern California chapter, has seen more residents volunteering to host and assist newcomers to the country. A comparable surge has occurred at other IRC offices across the country.

“People want to help,” she says. “That’s what’s especially disheartening about the drop in admissions: It in no way reflects the overall attitude of communities.”

On a recent afternoon, Ghory talked while sitting in the tidy apartment of one of his clients, Ahmad Rashid Jamal, who lives outside Sacramento and works for the California Department of Justice. He and his wife immigrated from Afghanistan in August last year through the SIV program, two months before the birth of their first child.

Mr. Jamal held positions with a pair of US agencies in Kabul. Driving to his office on a converted military base one morning in 2014, he saw a cloud of smoke rising from near its entrance. A suicide bomber on a motorcycle had blown himself up, killing five security guards. If traffic had moved a little faster that day, Jamal realized, he would have been waiting to enter the front gate at the time of the blast.

The frequency of such attacks in Afghanistan informs his perspective on the tensions over immigration in his adopted country. “In California, there are maybe not as many problems as in some states,” Jamal says. “But even in other states, you don’t have this feeling of being afraid every day of suicide bombers and militants shooting at people. That is a different fear.”

Khawari shares a similar outlook, and while he misses his family and aspects of Afghanistan, he had grown weary of living like a hostage in his own country.

Soon after arriving in Sacramento two years ago, he went to work as a cultural adviser with the aid organization World Relief. He has felt at ease among Americans, even as he senses that some hesitate to approach immigrants out of unfamiliarity or fear.

“We know it is not perfect here and there are problems,” he says. “But you have your rights as a human and a chance to grow. This is good.”

US State Department Bureau of Consular Affairs

With an eye on rising rents, cities start to regulate the gig economy

Does the home-sharing website Airbnb feed a shortage of long-term rental housing? We look at the gig economy balance of small-business freedom and government oversight.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

-

By Elena Weissmann Staff

In barely 10 years, Airbnb has grown to be a sharing website that puts 4 million rooms, homes, and apartments worldwide onto the daily rental market. That’s more than the Marriott and Hilton hotel chains combined. But from Dublin to New Orleans, people are questioning if Airbnb is adding to a squeeze in housing affordability by shifting units off the long-term market. Boston is among those setting new rules. As of 2019, the city will ban Airbnb “investor units”: properties that people rent out daily and do not live in. City Council President Andrea Campbell voted for the plan but notes that other factors affect Boston rents, including outdated zoning laws and city-owned vacant lots. Experts say the concerns about Airbnb are overblown and note that the hotel industry is a big lobbyist for restrictions. Meanwhile, the changes could be hard on people like Sean Cummings, an artist and entrepreneur whose family’s primary income is from Airbnb. “I don’t know what’s going to happen,” he says. “I have three listings right now; I could end up with zero next year.”

With an eye on rising rents, cities start to regulate the gig economy

On a rainy September afternoon, Sean Cummings hustles to an apartment in the Fenway neighborhood of Boston, a plastic bag filled with clean sheets thrown over his shoulder. With his muddied sneakers, square black glasses, and disheveled brown hair, Mr. Cummings looks very much like the free-spirited artist he is. But he is also an Airbnb entrepreneur.

Cummings saw the potential to earn good income from the online platform, which enables people to rent out their homes or rooms to strangers. In 2010, as a newly minted architect with mountains of student debt, he started renting out apartments on Airbnb. By 2016, he was making six figures – enough for him and his wife to send their kids to private school while launching an art business.

“Parents told us, you can be whoever you want to be! So here we are, we’re being who we want to be,” Cummings says as he strips a queen-size bed of its sheets in a creaky studio apartment.

But all that could soon change. The Boston City Council in June passed new rules that will outlaw many of Airbnb’s entire-home listings, including “investor units” that are not owner-occupied, such as those rented by Cummings.

Boston’s move is part of a wider trend, as a range of cities weigh greater regulation of the gig economy and Airbnb in particular. This fall, city governments from Dublin to Paris, New Orleans to Baltimore, are considering rules aimed at what they see as Airbnb fallout: noisy tourists and soaring rental prices. At stake is a balance between small-business freedom and market oversight.

“You have to be careful with these regulations, thinking about how you balance all the interests,” says Geoffrey Parker, an engineering professor at Dartmouth College in Hanover, N.H., and author of “Platform Revolution.” “You’re trying to achieve a policy goal, which is a valid one, but the question is, who is going to bear that cost?”

A housing crunch

Though many factors are coming into play, the debates about Airbnb typically center on one issue: affordable housing. At $2,200 a month, the median rent in Boston is one of the highest in the country, and it continues to increase by 2 to 3 percent annually. In the extremely dense New York metropolitan area, renting space to tourists is even more contentious. The worry is that some landlords are converting long-term rentals into short-term ones, driving up housing costs for full-time residents.

But experts say the concern, while it may have validity in cities with particularly high tourist-to-population ratios, lacks solid proof.

“In cities like New York and Boston, given the high cost of residential housing, there is little or no evidence that you can actually take a unit off the longer term market, run it as an Airbnb, and make money,” says Arun Sundararajan, a professor of business at New York University and author of “The Sharing Economy,” a book that explores how on-demand platforms will change society.

Mr. Sundararajan’s recent research finds that Airbnb hosts in New York would need to rent out their units for an average 216 days a year to break even on their long-term rental costs. The average Airbnb unit is rented for 45 days a year, suggesting that the typical host is trying to make a few extra bucks here and there, not relist entire properties year round.

'Other pieces' to the puzzle?

Boston City Council President Andrea Campbell voted in favor of the regulations, but says it remains to be seen if the rules will have their intended effect.

“We’re taking action based on different assumptions ... [but] we cannot as a city guarantee that these units are (1) going to become affordable and (2) that they will go to long-term tenants,” she says. “We already have folks who are thinking of other ways to go around this regulation.”

The rules in Boston will eliminate “investor units,” or properties that people rent out on a daily basis but do not live in, starting in 2019. Owners can continue to rent out private rooms in their homes, so long as they register with the city and pay an annual fee.

Ms. Campbell believes there are other factors affecting rental prices in Boston, including outdated zoning laws and city-owned vacant lots. “There are other pieces we should be talking about and not in silos,” she says.

Hotel-industry lobbying

Here and in other cities, opposition to Airbnb may be inflamed partly by intense lobbying from the hotel industry. Over the decade since its 2007 founding, Airbnb has grown to 4 million units listed – more than Marriott and Hilton combined – and spread to nearly every country in the world.

The American Hotel and Lodging Association put together an action plan in 2017 that included lobbying politicians and funding studies to demonstrate Airbnb’s impact on rental prices, according to The New York Times. It’s uncertain how much this behavior influenced officials, though 2018 saw Boston, New York, and San Francisco pass Airbnb regulation.

“It’s clear the hotel industry is using the government to create protections for themselves,” says Louis Hyman, an associate professor of labor relations, law, and history at Cornell University in Ithaca, N.Y. He says this is typical behavior for incumbent businesses facing disruption, and governments should not necessarily listen to them.

Campbell acknowledges that hotels were involved in the City Council’s conversation, but says she made her decision based on her constituents – and that she’s open to regulatory “tweaks” in the future, depending on how the current rules play out.

For Cummings, however, the regulations most certainly spell his demise as a Boston Airbnb host.

“I don’t know what’s going to happen. I have three listings right now; I could end up with zero next year,” he says. He intends to continue listing out properties for as long as possible, and after that, turn to his side-project: a plot of land he recently bought in Vermont, on which he plans to build a set of tiny houses for skiiers and other recreationalists.

Vermont’s Airbnb laws are less strict, requiring only that hosts comply with general safety standards and pay a tax. This makes it a more fitting place for Cummings’s real estate pursuits, he explains.

“I’m just going to move my operation to another state,” he says with a faint smile and a shrug.

Community, in harmony: behind a wave of ad hoc choirs

Singing together is a millennia-old way of building community, though these days it's largely relegated to the religious and professional realms. As an open-to-all pop choir in Toronto shows, it doesn't have to be.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

Choir!Choir!Choir! is arguably the most accessible singing group around. No auditions, no competition about who gets to be section leader here. All one does is drop in, pay $5 at the door, grab a lyric sheet, and self-select as a “high,” “low,” or “mid” to sing the hits from David Bowie, Guns N’ Roses, Aretha Franklin, and Nirvana. The event's weekly sessions have become a social phenomenon, at least in Toronto, where participants range in age on any given night from 19 to 89. Started in 2011, Choir!Choir!Choir! is part of a wave of community choirs that has gathered force across North America. It’s also just old-fashioned fun, where adults who don’t know each other come together in common, musical purpose. “When we were younger, so many people were told that they should never sing because there's a right and a wrong way to do it. And if you did it wrong, then you were kind of banished from doing it," says co-founder Nobu Adilman. “And we're inviting all those people back and saying you probably can do it.”

Community, in harmony: behind a wave of ad hoc choirs

Luc Rinaldi and Steph Braithwaite lead the high-range voices through the catchy melody of the ’90s hit song “Torn” by Natalie Imbruglia. “Take a vocal rest, sip some lemon tea,” says Ms. Braithwaite from the stage when they're done.

It’s time for the “lows” and “mids” to learn their parts, an intricate harmony that the founders of Toronto-based Choir!Choir!Choir! have rearranged. “We’ll see you in about 30 minutes,” Mr. Rinaldi jokes.

The chorus is indeed complicated. There is a lot of standing – and then shuffling. One woman clutches a flashlight to better see the lyrics on her sheet. Some members have to take a seat – the participants range in age on any given night from 19 to 89. There is a constant urge to just belt it all out, but the singers must suppress it until everyone knows his or her part.

Two hours later – flat notes corrected, collective starts on the downbeat and crescendos perfected – a circle is formed. “Torn” might not be everyone’s favorite song – Rinaldi spends the better part of the night ribbing it as he accompanies the piece on his guitar. But after the choir cuts out from the last note, a long-held “oh” in a three-part harmony, there is single beat of silence, and then the rush.

“It is hard,” says Greg Fontaine, who has shown up weekly since 2015 to sing the hits from David Bowie, Guns N’ Roses, Aretha Franklin, and Nirvana. “You are spending all this time and mental energy trying to achieve this goal, and it is a struggle sometimes. And when you kind of do that in song, I don’t know what it is, there’s this rush like ‘yeah, we did it.’ ”

Started in 2011, Choir!Choir!Choir! is arguably the most accessible singing group around. No auditions, no competition about who gets to be section leader here. All one does is drop in, pay $5 at the door, grab a sheet of music, and self-select as a “high,” “low,” or “mid.”

It is part of a wave of community choirs that have gathered force across North America. It’s also just old-fashioned fun, where adults who don’t know each other come together in common, musical purpose. (Full disclosure: This journalist joined it when newly arrived in Toronto in August, and thinks it’s one of the best groups she has ever participated in.)

The founders of Choir!Choir!Choir!, Nobu Adilman and Daveed Goldman (who work together professionally as “DaBu”), have since gone far. Their choruses have backed up stars like Rick Astley, and they attract massive audiences for tributes when artists like David Bowie or Aretha Franklin pass. Today Mr. Adilman and Mr. Goldman travel at least a full third of the year, taking Choir!Choir!Choir!, which is part singsong and part comedy show, to anywhere from small-town Ontario to Oklahoma.

But it’s the weekly sessions that have become a social phenomenon, at least in Toronto. Ken McLeod, an associate professor of music history at the University of Toronto, says that singing together – versus alone in one’s car – forges a sense of well-being and "secular fellowship,” as he calls it, “ in an era that is increasingly defined by virtual experience and hyper-real experiences.”

Even with a pop song like “Torn” sung in the back of a tavern, where Choir!Choir!Choir! meets twice weekly, the experience is powerful.

“Anyone who has done it knows there is this intangible ‘the sum of us is larger than the individual,’ this sense of energy that resonates, and just gets amplified in a group singing experience,” he says. “There is this vibrational resonance that sonically connects you to other people.”

Adilman says that part of their goal is to draw people back to creative expression they may have been cut off from.

“When we were younger, so many people were told that they should never sing because there's a right and a wrong way to do it. And if you did it wrong, then you were kind of banished from doing it," he says. “And we're inviting all those people back and saying you probably can do it. Maybe you won’t sound great right off the top and we'll make fun of you for that, but we'll do it in a nice way and encourage you to try harder.”

Fontaine happened upon Choir!Choir!Choir! by accident one summer night while he was out on a bike ride. He heard people singing “Landslide” by Fleetwood Mac and found himself drawn into the backroom of a bar. He had never sung in his adult life and remembers feeling so uncomfortable that he basically hid behind a pillar at the back.

“I was just really maybe making noises,” he says. “I was very quiet. It was a bit of a scary experience.” But he returned, again, and again. “I always assumed I couldn’t sing. I realized at some point in the fall that I am kinda singing, that’s a passable form of singing.”

It’s not surprising to Professor McLeod that people like Fontaine get hooked.

“To entertain ourselves as individuals, we’ve been sitting around campfires and singing songs communally since we were cave people,” the professor says. “This is something probably deeply ingrained in our human experience, even if we lost touch with it, or haven’t done it since we were kids, or have never done it and are experiencing communal singing for the first time. It can be tremendously empowering.”

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

China’s faithful, under siege, can shine a light

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

Followers of the various religions in China have long felt a need to choose between compromise or confrontation whenever their beliefs were oppressed by the ruling Communist Party. Under leader Xi Jinping, the party has decided that the survival of its secular ideology depends on expelling “foreign” values, such as liberty of conscience. In the midst of this crackdown, the Vatican signed an agreement Sept. 22 with the government aimed at ending a stalemate over whether the party or the Roman Catholic Church should choose local clergy in China. The details remain secret. Some Catholics worry that the Holy See may have given too much away. But to his credit, Pope Francis released a statement that might help all religious followers in China. He said that the church simply needs to find “authentic shepherds” who are “committed to working generously in the service of God’s people, especially the poor and the most vulnerable.” Qualities of love found in most faiths can influence human thinking. For Christians, Muslims, and others in China, the choice of how to deal with oppression need not be between compromise and confrontation.

China’s faithful, under siege, can shine a light

Compromise or confront?

For decades, followers of the various religions in China have often felt a need to make such a choice whenever their beliefs or worship were oppressed by the ruling Communist Party.

In the past two years, following a few decades of leniency by the party, that oppression has grown worse. Hundreds of churches have been destroyed. Mosques have been altered. A famous Buddhist monastery was forced to fly the national flag.

In April, online sales of the Bible were banned. Thousands of Muslim children have been taken from their parents and taught to reject Islam. Officials now bar children from attending Christian services or require the singing of Communist Party songs instead of hymns.

Under leader Xi Jinping, the party has decided that its secular ideology and its long-term survival depend on expelling “foreign” values, such as liberty of conscience. It has launched an active campaign of “thought reform” among religious believers.

“We must resolutely guard against overseas infiltrations via religious means,” he said in 2016.

In the midst of this official crackdown – which includes not only religious faithful but also writers, artists, and legal activists – the Vatican signed an agreement on Sept. 22 with the government. The pact is aimed at ending a decades-long stalemate over whether the party or the Roman Catholic Church should choose local clergy in China.

The details remain secret and the “provisional” agreement has drawn heavy criticism from Catholics who claim the Holy See has rendered too much unto Caesar. But to his credit, Pope Francis released a statement that might help all religious followers in China.

He stated that the church simply needs to find “authentic shepherds” who are “committed to working generously in the service of God’s people, especially the poor and the most vulnerable.”

The pope said the trials that Chinese Christians have long endured are a “spiritual treasury” in which God “never fails to pour out his consolations upon us and to prepare us for an even greater joy.” Chinese Catholics, he said, must be seen to have “a greater commitment to the service of the common good and the harmonious growth of society as a whole.”

Regardless of painful experiences of the past or wounds not yet healed, he said, the path to reconciliation is through fraternity, forgiveness, dialogue, and service.

He is throwing seeds on fertile ground.

A 2017 poll found 47 percent of Chinese identified “moral decline” as their chief concern. And in a remarkable essay called “Imminent Fears, Immediate Hopes” published in July, Xu Zhangrun, a professor of law at Tsinghua University in Beijing, wrote:

“People nationwide, including the entire bureaucratic elite, feel once more lost in uncertainty about the direction of the country and about their own personal security, and the rising anxiety has spread into a degree of panic throughout society.”

Professor Xu added that a nation’s maturity requires a freedom of spirit and that “attempts to silence it cannot detract from the realities of shared human ideas.”

Many Christians in China are learning how to preserve such a freedom of spirit, even if it is by simply reading the Bible alone each day. Many now meet in smaller groups and not on a Sunday. They have turned their form of worship into outward compassion toward neighbors in need.

One Christian in Zhengzhou told The Associated Press after the recent breakup of her church by officials, “The people have dispersed, but our faith has not. God’s path cannot be blocked. The more you try to control it, the more it will grow.”

Others in China facing oppression have come to similar conclusions.

A famous Tibetan Buddhist, author Tsering Woeser, wrote in a 2015 blog that her troubles with authorities were a blessing in disguise, giving her “a precious kind of spiritual freedom for which I am deeply grateful.”

And before China’s most famous political dissident, Liu Xiaobo, died in prison last year, he wrote that he holds no animosity toward his jailers or the Communist Party. “Hatred can rot away at a person’s intelligence and conscience. Enemy mentality will poison the spirit of a nation, incite cruel mortal struggles, destroy a society’s tolerance and humanity, and hinder a nation’s progress towards freedom and democracy,” he wrote.

The party’s fears of religious faith as an uncontrollable force should not be mirrored back by the faithful. Rather, qualities of love found in most faiths can influence human thinking. For Christians, Muslims, and others in China, the choice of how to deal with oppression need not be between compromise and confrontation.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Taking God’s lead

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Michelle Boccanfuso Nanouche

How can an understanding of God help us when we need to make a decision, big or small? Today’s contributor shares how a clearer sense of God’s nature has helped her listen to His guidance, rely on it, and be blessed by it.

Taking God’s lead

It’s safe to say that people generally want to be happy and successful in what they do. So, whether we’re making small decisions in our day-to-day lives or a large decision that will impact us in a big way, why might it be beneficial to one’s happiness and success to seek divine guidance and let God “take the lead”?

To take God’s lead really means to yield to good – to the divine good that is God. Christ Jesus taught that God is good, and Christian Science teaches that good isn’t merely a descriptor for God; rather, the essence, nature, and being of God is actual, concrete good.

Turning to God as infinite, unlimited good to guide, instead of relying on a limited human sense, always leads to better opportunities and ideas. Why? Because even the best-intentioned human concept has inherent limitations. Trusting divine good and listening to and following God’s guidance can circumvent the fear, doubt, rigidness, or personal will that can put an otherwise good idea at risk of failure.

God’s goodness is ever present, always accessible and available to us. But do we always see the good or feel it? Maybe not. And yet it is there, already in place and waiting for us. Oftentimes what is needed is a shift in our thought from fear to trust – from a rigid or narrow focus on a projected outcome to a yielding to the infinite possibilities or answers that are right at hand.

Guidance is found as we listen for thoughts of good that come to us from God. Monitor founder Mary Baker Eddy explained that we can recognize these inspired thoughts – which she called God’s angels – “by the love they create in our hearts.” She goes on to say, “Oh, may you feel this touch, – it is not the clasping of hands, nor a loved person present; it is more than this: it is a spiritual idea that lights your path!” (“Miscellaneous Writings 1883-1896,” p. 306). Love sifts out any limited personal agenda or mere human will.

When I have felt pushed and pulled by the wants and wishes of a personal self, I haven’t felt loved or loving. And making human plans and setting personal goals has rarely worked out well for me in the long term, leaving me disappointed. It has only been through turning from personal ego to the one Ego, God, and quietly listening for spiritual direction that I have found a way forward.

I once applied for a position I wanted but wasn’t offered the job. It was a good job that would be a blessing to many, and I felt it was a good idea to apply. But I didn’t see at the time how much I had yet to learn about not trying to go faster or further than God was leading me. I applied several more times for the same job over the course of many years. And each time the answer was no. Each no, while disappointing, compelled me to appreciate present good and to develop other opportunities.

The last time I applied – after 15 years – I asked God if I should even try again. And the intuition was that, yes, I should. But with this direction came the realization that I should also trust God’s leading of others, whose job it was to decide if I would get the job or not. I hadn’t thought of that before. My focus had always been on God guiding me – and my wanting to do it. I felt a surge of love for everyone in the decisionmaking process. I trusted them because I trusted God to guide them, just as I was being guided. I applied, and that time I got the job. In hindsight, I can see how different my circumstances were, how much better prepared I was, and how I wouldn’t have had the same rich experience in that work had I been hired any of those other times.

God’s guidance is a precious thing to seek and an invaluable thing to find. Divine good really is our best advocate. God is Love, and divine Love demands the best for us and the best of us. Letting Love take the lead is key to living a life of blessing others and a life of being blessed.

A message of love

Fan on a road trip

A look ahead

Thanks again for being with us. Tomorrow we’ll take a look at the rapidly improving field of attribution science, which seeks to add some clarity around the precise role of climate change in extreme weather events, especially hurricanes.