- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- Asylum-seeker caravan: What not to miss about the Mexico factor

- Democrats rake in big bucks from small donors, but effect is unpredictable

- Rent control on ballot as California seeks a fix for housing costs

- Why Americans are talking less and less about ‘love’ and ‘kindness’

- Affordable apartments, good books included? A Chicago experiment.

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

America’s crisis of misunderstanding

Mark Sappenfield

Mark Sappenfield

Today was as good a day as any for us all to have a Howard Beale moment from the 1975 movie “Network” – to get mad and not to take it anymore. Start with the conversation around the migrant caravan moving through Mexico toward America.

This presents a difficult set of choices. Should a nation with comparative abundance turn its back on those in need – on people whose daughters and granddaughters, data show, would likely expand American wealth, innovation, and growth? Or should a nation be compelled to accept those who come to its borders uninvited even when it has ample problems of its own? There can be no single right answer to questions so complex and ethically fraught.

Yet the state of the debate on cable news and beyond is often rigidly self-convinced along partisan lines. One result is reckless or willful misunderstanding of the other side. The unwillingness to understand others leads to the too convenient solution of demonization and delegitimization. The apparent mail bombs sent to CNN, Barack Obama, and Hillary Clinton Wednesday are only the latest examples of where this mental toxin leads.

As much as immigration or transgender rights or the Supreme Court, the acceptance of willful misunderstanding is a crisis because it makes honest, constructive discussion on those issues impossible. Fortunately, the solution lies not in Washington but in our own conscience – and what that prods us to ask of one another, from Facebook friends to politicians.

Now on to our five stories. Today we examine what a surge of online donations says about American politics, why the words of spirituality are being heard less often, and how the best way to tackle a problem in Chicago was to make it even bigger.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Asylum-seeker caravan: What not to miss about the Mexico factor

Amid the American debate over the migrant caravan, Mexico’s own struggles to deal with the situation are often overlooked. But they are substantial and point to a country trying to balance different needs.

-

By Louisa Reynolds Correspondent

-

Whitney Eulich Correspondent

This week, as President Trump demanded that countries stop a caravan of migrants attempting to reach the United States, Mexico appeared to take heed. Officials deployed some 400 federal police to its border with Guatemala and broadcast information about migrants’ options as well as repercussions for crossing borders illegally. But Mexico’s incoming president, Andrés Manuel López Obrador, may shift course after his inauguration in December. The president-elect campaigned on promises not to kowtow to the United States and has said he wants people in the caravan to know “they can count on us.” Mr. López Obrador has criticized officials’ and criminals’ abuse of migrants – one of the dangers that motivates caravans to travel together – and has signaled willingness to issue temporary work visas. Some doubt AMLO, as the president-elect is known, will be able to implement any new policy. He may have “good intentions,” says Sister Magdalena Silva, who runs a migrant shelter in Mexico City. But “there isn’t much margin for change.”

Asylum-seeker caravan: What not to miss about the Mexico factor

“Sí se pudo! Sí se pudo!” some 4,000 Hondurans chanted last Friday, as they crossed the bridge above the Suchiate River dividing Guatemala and Mexico. We did it!

The jubilation was short-lived, as the migrants and refugees were stopped after a week-long journey by a row of Mexican riot police. As the crowd pressed forward on the bridge, tearing down barriers that blocked entrance into Mexico, the police responded with tear gas. For a moment, amid the pressing bodies and swaying bridge, a stampede seemed inevitable.

By Tuesday, Mexico was processing 2,727 asylum requests related to the caravan, officials said. The government says it will let in groups of 150-200 asylum-seekers per day. Another several thousand, frustrated and sometimes scared by the long wait, took their chances by swimming, or hiring rafts, to get across. Those entering illegally will be deported, officials have warned, but by the end of the weekend, caravan members who had already crossed into Mexico voted to continue moving north regardless.

The caravan, which has since grown to an estimated 7,000 people from across Central America and Mexico, left San Pedro Sula, Honduras, on Oct. 12. Like the many, much smaller caravans before it, its aim was to create safety in numbers as migrants crossed Guatemala and Mexico toward the US southern border.

In a series of tweets this week, US President Trump called the caravan a national emergency and reiterated criticisms of El Salvador, Honduras, Guatemala, and Mexico for not halting the flow at their borders. He’s threatened to pull US funding for countries that allow migrants and asylum-seekers north.

Mexico appeared to take heed, deploying some 400 federal police to its border late last week and putting out statements about who can qualify for asylum in Mexico. They also broadcast the repercussions for crossing the border illegally, and called on the United Nations’ Refugee Agency for help with the influx.

Mexico’s preemptive moves are unprecedented, observers say – like the immense size of the caravan itself. Although Mexico has appeared eager to appease the United States, cracking down on lax migration on its border with Guatemala since 2014, it’s also on the cusp of a potentially new immigration policy under incoming President Andrés Manuel López Obrador, who campaigned on promises not to kowtow to the US. The new administration has signaled willingness to issue temporary work visas to Central American migrants, and Mr. López Obrador said in a speech in the southern state of Chiapas this week that he wants people in the caravan to know “they can count on us.”

“Mexico is in a difficult situation,” says Néstor Rodríguez, an immigration expert at the University of Texas at Austin. “They don’t have the strongest posture until the new president comes on board [and] they are pressured by the migrants as well as the US.”

'A better place where there's no crime'

Images of the caravan – stretching more than a mile on rural roads in Guatemala; filling the vast border-crossing bridge leading into Mexico; and its crowds huddled in plazas, trying to decide how to proceed – are reminders of the widespread violence, economic instability, poverty, and government repression many Central Americans are trying to escape.

Heidy Marleny Castro waited on the bridge over the weekend, weighing her options: stay in line without food or water, possibly for days, until she can speak to a Mexican official; or cross the river without registering, in order to continue. She’s traveling with her two youngest children, 8 and 13 years old. Her two oldest sons were killed by gangs in Honduras in 2015.

“We live in a scary country,” she says, raising her voice above the din of the crowd, and keeping a watchful eye on her kids amid the chaos. “We’re making this sacrifice for our children because we want a better life for them.”

With 3,791 murders in 2017, Honduras has a per capita homicide rate of 42.8 violent deaths per 100,000 inhabitants, making it one of the most violent countries in the world.

Malena Soto, a young mother, says she joined the caravan because she can’t afford to feed her two children on the $6 per day she earns selling food on the street in Honduras. According to the World Bank, nearly 61 percent of Hondurans live below the poverty line.

Several unaccompanied minors joined the caravan without their parents’ permission. Among them is Jonathan Losán Cruz. At the age of 14, he’s been mugged twice at gunpoint, and fears gang recruitment in his crime-ridden neighborhood in coastal Honduras. He wants to travel all the way through to the US, a country he imagines as “a better place where there’s no crime.”

'Unprecedented' challenge

Over the past two decades, many caravans have begun the trek north, with people assuming it’s safer than traveling on their own across Mexico: a journey that carries great risk of extortion, violence, kidnapping, and abuse by officials or organized criminals. It is also a chance to save money, as human smugglers can charge a migrant more than $5,000.

“In practice, this number of people is hard for any government to manage,” says Maureen Meyer, the director for Mexico and migrant rights at the Washington Office on Latin America, a research and advocacy organization. She calls the size of this caravan “unprecedented.”

Previous caravans have often shrunk dramatically as they progress – routes across Mexico toward the US border can cover more than 2,000 miles – with people deciding to turn back or stay put along the way. Last spring, for example, one group that had reached 1,500 migrants dwindled dramatically: 401 requested asylum in the US, and another 122 were apprehended trying to enter illegally. (Of the current caravan’s travelers, more than 1,000 Hondurans are estimated to have already returned home.)

Mexico has increased enforcement on its southern border in recent years, “not just in response to the US, but for clearer control of people and goods,” Ms. Meyer says. Mexico’s preliminary response of communicating with the caravan, trying to process the group in an orderly fashion, and calling for reinforcements from the United Nations was positive, she said. But reports of police violence on Friday need to be investigated, she adds.

In southern Mexico, police have shadowed the caravan, but have not blocked its movement. But there are outstanding concerns. “How do you really monitor and control that many people traveling together?” Meyer asks, noting the possibility for traffickers or other threatening individuals to infiltrate the group. It’s something “Mexican authorities need to be on the watch for now.”

AMLO's first test?

Expectations are high for Mexico’s new president, often referred to by his initials, AMLO. Yet there are few clues as to what changes he can or will implement in practice.

AMLO, who will be inaugurated in December, may have “good intentions” on changing Mexico’s approach to migration, says Sister Magdalena Silva, who runs a migrant shelter in Mexico City. But “there isn’t much margin for change.”

“If AMLO says something and Trump doesn’t like it, he can just threaten Mexico with NAFTA or other resources,” she says in her crowded office, fielding calls and taking messages about the approaching caravan.

The president-elect has criticized migrants’ abuse, and has called for a “zero-tolerance” policy toward abuse by federal and local agents, citizens, and organized criminals, Meyers says.

Although Mexico has deported more Central Americans than the US since 2015, it has also seen a sharp uptick in the number of asylum applications it has received – and approved – in recent years. The fact that it has been able to absorb a few thousand refugees each year in recent years gives some observers hope for a change in migratory flows.

“Anything Mexico can do will be very helpful not just to keep the migrants out of the US, but for the migrants’ sake themselves,” says Professor Rodríguez.

Democrats rake in big bucks from small donors, but effect is unpredictable

Ahead of the US midterm elections, online donations are rewarding more liberal candidates and potentially making them more accountable to voters. Is this a voter revolution or just an expensive way to vent?

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

For opponents of big money in politics, 2018 feels like the rumblings of revolution. If Rep. Beto O’Rourke – the Democratic nominee running an unlikely campaign against GOP Sen. Ted Cruz in Texas – can raise $38 million in three months without the help of a super PAC, then the possibilities are endless. Suddenly anyone with charisma and an internet connection can run a viable campaign. More importantly, advocates say, average Americans can begin to wield power in politics again because candidates who rely on smaller contributions will be more accountable to those donors than to megacorporations with shadowy agendas. Skeptics, on the other hand, point out that a lot of these donations go to progressive candidates, who by standard political measures are running improbable races at best, as opposed to those competing in expensive races in swing districts. “Uncoordinated donations are a pretty unstrategic way of going about trying to retake the House or the Senate,” says Adam Hilton, a politics professor at Mount Holyoke College. “If all that enthusiasm whipped up is ultimately going to not result in the outcome that people want – like shifting the balance of power in Congress – you might end up deflating people.”

Democrats rake in big bucks from small donors, but effect is unpredictable

Two weeks before voters head to the polls, the 2018 campaign season continues to shatter records. Candidates are set to break the $5 billion mark by Election Day, putting this cycle on track to becoming the most expensive congressional election season in US history.

The fundraising figures, which favor Democratic candidates, support one prevailing narrative of 2018: that political winds, fanned by anti-Trump fervor, are sweeping Democrats forward in races across the board. From Texas to New York, progressive challengers are outraising established incumbents and upending conventional wisdom about money in major elections.

For opponents of big money in politics, this feels like the rumblings of revolution. If Rep. Beto O’Rourke – the Democratic nominee running an unlikely campaign against GOP Sen. Ted Cruz in Texas – can raise $38 million in three months without the help of a super PAC, then the possibilities are endless. Suddenly anyone with charisma and an internet connection can run a viable campaign.

That could have the effect of reorienting the party towards the kind of left-leaning candidates that seem to appeal most to small-dollar donors, advocates say. More importantly, average Americans can begin to wield real power in politics again, because once in office, candidates who relied on smaller contributions will be more accountable to those donors than to mega-corporations with shadowy agendas.

At least, that’s the theory. Some political analysts wonder whether, in the end, the flood of money will actually help Democrats as much as it seems. A lot of these small-dollar donations are going to candidates who, by standard political measures, are running improbable races at best. If Democrats wind up underperforming, the results of Nov. 6 could cause a reassessing of the value of fundraising as a measure of grassroots appeal – and even discourage would-be donors in the future.

And the latest set of campaign financial disclosures showed Republican national party committees and top GOP super PACs with more cash on hand than their Democratic counterparts going into the final leg of the cycle. The late-game advantage could help the GOP invest more strategically in candidates who are low on cash but still in competitive races.

“Online giving has probably revolutionized political campaigning. Democrats in particular have really capitalized [on the trend],” says Sarah Bryner, research director at the Center for Responsive Politics (CRP), which tracks money in elections. “But donors often have a more optimistic view of change than the demographics of a region suggest,” she adds. “It ultimately is up to constituents.”

Banking political power

Back in August, when the fight to confirm then-nominee Brett Kavanaugh to the Supreme Court was just beginning to crest, the progressive Be A Hero Fund started a campaign on the crowdsourcing site Crowdpac. Organizers asked donors to make “pledges” against Republican Sen. Susan Collins of Maine, who was seen as one of the key swing votes. If she voted against Judge Kavanaugh, donors wouldn’t be charged. But if she voted for him, the money raised would go to her Democratic challenger in 2020 – whomever he or she may be.

The campaign collected $1.3 million in one month, enough to match the cash Senator Collins had on hand. Twice the site crashed because too many people were rushing to contribute: First when Collins announced in early October that she would be supporting Kavanaugh, and again when she voted to confirm him. This week, the campaign hit its $4 million goal in total donations both through Crowdpac and other sources, says Be A Hero spokesperson Liz Jaff.

Critics would note that’s $4 million Democrats can’t tap for current down-to-the-wire races that could very well determine control of the Senate. “Those donations are more ideologically driven than rational, cool, strategic,” says Adam Hilton, a professor of comparative and historical politics at Mount Holyoke College. “That could have ripple effects through the party.”

To Ms. Jaff, that’s the point: funding an as-yet-unidentified candidate shows that voters are in charge. She calls it “rage donating” – a way of channeling anger at the system by putting money exactly where donors want it to go, not to an organization that’s going to do the choosing for them. The Be A Hero campaign has already reshaped the Maine 2020 Senate race, she says. And it could prove the power of “conditional fundraising” for issues like health care, the tax bill, and even immigration in legislatures nationwide.

Jesse Thomas, head of strategy and marketing at Crowdpac, says donors are “banking their political power” in a way that’s never been done before.

Existing candidates have also benefited from this combination of voter outrage and user-friendly technology. Democrats have raised a total of $205 million in donations of $200 or less in 2018 – three times more than Republicans, according to The Washington Post. Crowdpac’s user base has quadrupled since 2016, Mr. Thomas says, and contributions through the site rose 77 percent between 2017 and 2018.

ActBlue, a nonprofit online fundraising service that caters to Democrats and progressives, has processed $1.5 billion in donations since 2016. That’s double the total amount the company has raised since it was founded in 2004, says executive director Erin Hill. “And they’re coming in amounts of $30, $40 dollars. I don’t think we’ve seen this kind of engagement across the board.”

Advocates of campaign finance reform have been thrilled. They see this election as a chance to prove that candidates can run and win without the influence of “dark money” – funds donated to groups that can spend unlimited amounts on political campaigns without disclosing where the money came from. That could, in turn, shift the balance of power in Congress from big corporate donors to actual voters, they say.

“There’s a huge difference between tens of thousands of people giving $15 and 1,500 people giving $10,000,” says Tiffany Muller, president of End Citizens United, a political action committee working to reverse the 2010 Supreme Court ruling that opened the door for unlimited political spending by corporations and unions. “That changes who you’re accountable to as a member of Congress. It changes which voters you are fighting for.”

Over the past decade – and especially since the Citizens United ruling – the Democratic Party has flagged in donations for candidates who aren’t running for president. Strategists say one-click contributions could grease the gears for potential donors who before might have hesitated to use cash to engage in politics.

“If you make it easy for a person to get involved, they will,” says Taryn Rosenkranz, founder and chief executive of New Blue Interactive, a Democratic digital strategies firm. “At any moment, when I feel emotionally invested – boom, I can do something about it. I can purchase that hat or yard sign,” or send $20 to a candidate halfway across the country.

Uncoordinated donations

Of course, if most of a candidate’s donors are from outside his or her state or district, then the amount raised from small-dollar donations is not necessarily a reliable indicator of support. Missouri Sen. Claire McCaskill, widely considered one of the most endangered Democrats in the Senate, has raised more than $30 million – with $4 million coming from outside spending groups – against Republican challenger Josh Hawley. But that hasn’t kept her race from being perilously close, with polls showing a slight advantage going to Mr. Hawley.

Congressman O’Rourke, despite receiving 60 percent of his funding from in-state donors, has trailed Senator Cruz in most major polls. (Real Clear Politics had Cruz ahead by an average of 7 points in the first two weeks of October.)

Progressive candidates this cycle have tended to generate more excitement, and dollars, than moderate ones. Which means the candidates who need money the most – many of whom are running expensive races in swing districts or states that went to President Trump in 2016 – may not be getting the support they need. “If you were a donor inclined to give to Bernie Sanders, you’re probably not as inclined to give to Claire McCaskill,” says CRP’s Ms. Bryner. “You just don’t see the connection.”

“Uncoordinated donations are a pretty unstrategic way of going about trying to retake the House or the Senate,” Professor Hilton adds. “If all that enthusiasm whipped up is ultimately going to not result in the outcome that people want – like shifting the balance of power in Congress – you might end up deflating people.”

For some activists, though, the “wait-and-see” attitude misses the point. Whatever happens on Nov. 6, they say, the important thing is that people – mostly Democrats in this cycle – were willing and able to engage in the political process. Most donors know that one small contribution isn’t going to make or break a high-stakes contest like the Texas Senate race. But it might make a candidate more competitive, and it empowers average folks to see their money go somewhere they care about.

Sometimes, that’s enough.

“If you were to ask the Supreme Court, they’re just speaking very loudly,” Bryner adds, half joking. “That is what a lot of donors are doing. They’re expressing themselves.”

Rent control on ballot as California seeks a fix for housing costs

Everyone agrees that California needs more affordable housing, and fast. The question is whether a ballot initiative to strengthen rent control helps or hurts.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 8 Min. )

Some 3 million tenants in California meet the federal definition of “rent-burdened,” based on the share of income spent on housing. Meanwhile, the state needs an estimated 3.5 million new housing units by 2025 to satisfy demand. That’s the backdrop for Proposition 10, a ballot initiative that would let cities create stronger rent control policies than the state has permitted since 1995. Supporters say it would curb soaring rents in California, where the median is $2,440 a month. “The state doesn’t do anything for renters. It does everything for owners and developers,” says Zev Yaroslavsky, a former Los Angeles city official. Critics of Prop. 10, including industry groups, say rent control stymies new projects; they favor easing regulations to spur more building. “If my costs keep going up on the development side but I can’t charge more for rent, I’m out of business,” says developer Denton Kelley in Sacramento. Some analysts say the real need is more public funding to promote affordable housing. Still, boosters see Prop. 10 as providing a degree of help. “Without rent control,” says tenant Elsa Stevens, “it’s a free-for-all for landlords.”

Rent control on ballot as California seeks a fix for housing costs

The startling dimensions of California’s housing crisis take shape through numbers. More than 134,000 people lack permanent shelter, accounting for a quarter of the country’s homeless population. Some 3 million tenants – more than half the statewide total – meet the federal definition of “rent-burdened,” spending at least a third of their income on housing. The state needs to add an estimated 3.5 million new housing units by 2025 to satisfy demand as the population grows.

The problem appears obvious. The proposed solutions, on the other hand, elicit conflicting opinions as reflected by the expensive fight over a ballot measure to remove restrictions on rent control that California voters will decide Nov. 6.

Proposition 10 would grant cities authority to create stronger rent stabilization policies than the state has permitted since lawmakers passed the Costa-Hawkins Rental Housing Act in 1995. Named for its legislative authors, the law prohibits cities from capping rents on properties built since early that year and gives landlords a free hand to boost rents after tenants vacate units. The law also exempts condominiums and single-family homes from rent control rules.

The tussle over Prop. 10, which would repeal Costa-Hawkins, has drawn $80 million in campaign donations and inflamed debate over the potential impact of rent control on the state’s housing shortage. Supporters contend the measure’s passage would curb soaring rents and provide low-income tenants with greater stability. Opponents claim that abolishing Costa-Hawkins would deter new construction, and they call instead for easing building regulations to speed housing projects along.

Tenant and affordable housing advocates agree in principle for the need to accelerate construction. But they emphasize that, given the gulf between the ever-deepening demand for housing and the available supply, rent control can deliver immediate relief for tenants struggling to survive.

“These are the people who are a lost job or eviction notice away from winding up on the streets,” says Zev Yaroslavsky, a senior fellow at the Luskin School of Public Affairs at the University of California, Los Angeles. He led a recent study that suggests Costa-Hawkins has contributed to Los Angeles County’s housing crisis. “What do we do about people with a bull’s-eye on their back right now?”

Yet as election day looms, public support for Prop. 10 remains tepid. A poll last month showed 36 percent of voters favor the measure while 48 percent oppose it. Perhaps more revealing, the survey by the Public Policy Institute of California found that a majority of renters would vote against the initiative.

The campaign opposing Prop. 10 has amassed $62 million in contributions and assailed rent control in TV ads as an ill-advised proposal that will widen the housing gap and inflate rents. Stephen Barton, co-author of a report from the University of California, Berkeley that details the merits of rent control, asserts that the simplified message and a general unfamiliarity with rent stabilization have tipped public opinion.

“If you listen to a discussion on rent control, you’ll hear people say, ‘Well, it has defects,’ ” says Mr. Barton, a former housing director for the city of Berkeley. “And then they’ll talk about how a well-functioning housing market can fix everything. But we don’t have a well-functioning housing market, and rent control is one of the tools that can help address the problems.”

The L.A. experience

Elizabeth Rivera lost her apartment in Los Angeles this summer when the landlord announced plans to demolish the eight-unit building. A few weeks later, her daughter, who has two young sons, had to leave her apartment after the property manager decided to more than double her $700 monthly rent.

Ms. Rivera and her daughter moved in together, renting a one-bedroom unit in Koreatown for $1,300 a month. The cost consumes about 40 percent of their combined income from Rivera’s $800 monthly Social Security check and her daughter’s minimum-wage job.

“It’s so much stress,” Rivera says. “We have trouble sleeping because we wonder if we’re going to be kicked out into the streets.”

A recent UCLA poll showed that more than a quarter of Los Angeles County’s 10.1 million residents worried about losing their home in the previous year. The figure spiked to 41 percent among tenants in a county with a median monthly rent of $2,440 and where renters occupy more than half the households.

The annual “quality of life” study found that almost three-quarters of residents favor legislation that would protect tenants from steep rent hikes while still enabling landlords to raise rents at an equitable rate.

“One of the things that’s wrong with Costa-Hawkins is that it’s a one-size-fits-all approach to rent stabilization statewide,” says Mr. Yaroslavsky, who oversaw the survey. For the former Los Angeles city councilman and county supervisor, the Prop. 10 scrum echoes a similar fracas that occurred in the city 40 years ago.

At the time, a confluence of forces – high inflation and a surge in property taxes, rental rates, and housing values – persuaded officials to enact rent control over the protests of landlords and developers.

Rulings by the US Supreme Court and California courts guarantee the rights of landlords to receive a “fair return” on rent-regulated properties. The city’s ordinance, passed in 1978, allows annual rent increases between 3 percent and 8 percent. Los Angeles officials deemed that range adequate to help property owners cover rising costs and prevent them from pricing tenants out of their homes.

But Costa-Hawkins has curtailed the city’s efforts to rein in rents. In addition to barring local officials from crafting new rent stabilization policies, the state law froze in place any such rules that cities already had established.

The restriction precludes Los Angeles – one of 15 cities in California with rent control – from enforcing rent control on properties built after 1978. Meanwhile, construction of below-market housing has ebbed. Those parallel trends, coupled with a drop in state and federal housing subsidies, have fueled gentrification and created an affordable housing gap of nearly 570,000 units across the county.

“The state doesn’t do anything for renters. It does everything for property owners and developers,” Yaroslavsky says. “If we keep this up for another generation, we’re going to have far more homelessness that we do now.”

Buffer for tenants

Construction and apartment industry groups top the list of Prop. 10 critics, who insist that loosening tax, environmental, and zoning regulations on new projects offers the best long-term answer to the housing crisis. Denton Kelley, a partner with LDK Ventures, a real estate developer in Sacramento, explains that the stubborn math of construction makes builders leery of rent control.

“If my costs keep going up on the development side but I can’t charge more for rent, I’m out of business,” he says, adding that the state should share the onus of alleviating the housing shortage.

“There’s no disagreement by anyone that there needs to be more housing and more affordable housing in California,” Mr. Kelley says. “But to bring more income-restricted housing to market, there needs to be a significant public source of funding to help cover the costs.”

An estimated 1.5 million tenants spend more than half their income on rent in California. The National Low Income Housing Coalition calculates that renters in California earn an average of $1,118 a month; the market rate for a one-bedroom apartment averages $1,355 a month.

A state report last year estimated that California stands to lose another 31,000 apartments to market-rate conversions by 2021. Barton, the former Berkeley housing director, contends that rent control policies allow cities to counter the pervasive resistance of residents to any type of new housing.

“Even market-rate apartment projects get attacked,” he says. “In most communities, you’re not going to overcome the attitude of exclusion to build enough new housing. So you have to come up with another way to help lower-income tenants.”

In the analysis of Manuel Pastor, a sociology professor at the University of Southern California, Prop. 10 would create a buffer for tenants against unemployment, illness, and other sudden misfortune. He co-authored a report published this month that found rent control enhances the odds of low-income renters remaining in their homes and, in turn, improves their financial security and overall health.

“Rent control isn’t the end-all, be-all solution,” says Mr. Pastor, director of USC’s Program for Environmental and Regional Equity. “But it’s an important tool for helping cities take the action that suits them and protecting tenants who might be vulnerable.”

The redevelopment void

The pace of housing construction in California plunged a decade ago as the country descended into a recession. The state has built an average of 80,000 units a year since 2007, less than half the supply needed to meet demand through 2025.

City planners and housing researchers regard rent control as a safeguard from rent-gouging and unjust evictions for low-income tenants, and dispute the notion that it stymies construction. In contrast, economists claim rent stabilization harms renters by shrinking the housing supply.

Foes of Prop. 10 cite studies on rent control in San Francisco and elsewhere to bolster their case. They predict that the initiative would hamper the ability of developers to attract financing for new projects, by squeezing profit margins. They also assert it would prompt landlords to repurpose rental units into condos to maintain their rate of return. In a paper last month, Kenneth Rosen, a UC Berkeley economist, argued that “the best model for the California housing market would be to reduce barriers to construction.”

Yet the call for deregulation from the measure’s skeptics draws the disapproval of one of their own. Mike Madrid, a Republican political consultant and the founder of Grassroots Lab, a public affairs firm based in Sacramento, describes the push to lower environmental and other building requirements as misguided.

“This idea that if you only streamlined the regulatory process, everything would be hunky-dory – no,” he says. “Just letting the market do what the market will do won’t be enough to solve the problem.”

Mr. Madrid favors reviving the state redevelopment program that Gov. Jerry Brown eliminated in 2011 as California confronted a massive budget deficit. The program funneled $5.5 billion a year to local agencies for low-income housing and other urban renewal projects. Although a state audit uncovered examples of questionable spending, the funding aided affordable housing efforts statewide.

In Los Angeles County, the loss of that money and additional cuts to state and federal subsidies caused public funding for housing to plummet by almost two-thirds – from $712 million to $255 million – between 2008 and 2016. San Diego County’s funding fell from $179 million to $55 million; Sacramento County’s from $68 million to $23 million.

“When the autopsy of the housing crisis is written,” Madrid says, “killing the redevelopment agencies is going to be the No. 1 culprit.”

Governor Brown’s probable successor, Gavin Newsom, the Democratic nominee for governor who holds a double-digit lead over Republican candidate John Cox, supports resurrecting the program. (Both oppose Prop. 10.) But even if that transpires, relief for renters could take years to arrive, and the measure’s advocates view rent control as a potential remedy in the interim.

Elsa Stevens and her husband live in an apartment complex without rent control for people age 55 and older in Richmond, Calif. They survive on Social Security and disability payments and estimate they spend 40 percent of their income on rent. Ms. Stevens has volunteered for a phone bank to help the Prop. 10 campaign out of concern for fellow renters on fixed incomes.

“Without rent control, it’s a free-for-all for landlords,” she says. “If they can charge someone two or three times what they’re getting from you, they’re going to push you out. It’s scary for renters in California.”

Why Americans are talking less and less about ‘love’ and ‘kindness’

As churchgoing has declined, Americans have talked less about spiritual issues and introspection. But the curiosity is still there, leading to efforts to find a fresh place in public conversation for moral values.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

Words like “love,” “patience,” and “kindness” have each declined in use by some 50 percent or more in the modern age, researchers have found. Fewer and fewer Americans, in fact, spend much time talking about moral or spiritual matters with each other anymore. The problem is especially acute as the bonds of shared communities have also declined, says the culture and religion writer Jonathan Merritt, author of the book “Learning to Speak God from Scratch,” who has traced the decline of “God talk” across US religious traditions, even among the most devout. “What is interesting when you look at linguistics is, you will find that a community’s shared vocabulary, its language, will tend to decrease in usage as [the] speaking community gathers less and less.” Observers point to the long-term decline in religious participation in American life and the fact that the country’s largest-growing religious cohort is the so-called “nones.” “[S]eeing the numbers go down for words like ‘love’ and ‘gentleness’ and ‘kindness’ – that is equally concerning to humanists as it is for religious folks,” says Roy Speckhardt, executive director of the American Humanist Association. “So how can we get back to that?”

Why Americans are talking less and less about ‘love’ and ‘kindness’

It’s not often that Roy Speckhardt finds himself going to church to talk about how to make the world a better place.

Yet as a leader in the community of American atheists and humanists, he’s been part of a few interfaith councils, some of which meet in churches near Capitol Hill. He’s even served on boards for groups advocating religious freedom, offering a nontheistic perspective to wide-ranging interreligious dialogues. Still, it took a while, he says, for some of the denominational leaders to get used to his being around.

“When I first entered these circles, the thought was, ‘Oh, should we allow atheists in?’” says Mr. Speckhardt, executive director of the American Humanist Association in Washington. “Should we allow people who are nonreligious to be part of this essentially religious community? So there was this hesitation and even trepidation – and especially a gap in knowing each other’s language.”

Participants would refer to themselves as “people of faith,” for example. “But pretty quickly people started changing,” Speckhardt says. “They’d look over and see me, and then they’d quickly add, ‘oh, yes, and people of goodwill.’”

There’s a measure of levity in his words, since part of his role as a thinker and advocate is to keep religious language out of public affairs. And goodwill is often notoriously lacking in discussions of religion and politics, the proverbial topics that, given their long history of divisiveness, should be avoided in polite conversation, many say. There’s also the fact that most Americans still have a chilly view of atheists, ranking them near the bottom of the country’s panoply of religious perspectives in opinion polls.

“But people started realizing, ‘Oh, we can come up with words that include us all, words that describe how we’re all seeking to make this world a better place, and how we have a common interest in humanity and in spreading compassion,’” Speckhardt adds.

Fewer and fewer Americans, in fact, spend much time talking about moral or spiritual matters with each other anymore, researchers say. As the country has become more pluralistic, even the most devout have tended to avoid talking about God and moral values, even among themselves.

50 percent less ‘love’ and ‘kindness’?

Words like “love,” “patience,” and “faithfulness,” for example, as well as words like “humility,” “modesty,” and “kindness” have each declined in use by some 50 percent or more in the modern age, researchers have found as they survey the millions of books and written records that have become digitized. “Moral ideals and virtues have largely waned from the public conversation,” concluded the authors in a study in The Journal of Positive Psychology in 2012.

“Religious language was once a source of spiritual undergirding, a language for your spiritual identity, and a resource of strength for coping and dealing with life and life’s unpredictable qualities,” says Bill Leonard, professor emeritus at the School of Divinity at Wake Forest University in Winston-Salem, N.C. “But that language may be less viable and less considered now, even by religious folks.”

Professor Leonard and Speckhardt point to the long-term decline in religious participation in American life, and the fact that the country’s largest-growing religious cohort are the so-called “nones.” Led by a growing number of Millennials abandoning traditional faith, around 30 percent of adults in the United States now reject identifying with a particular religious tradition. Of the 30 percent of “nones,” 37 percent say they don’t believe in God.

“But seeing the numbers go down for words like ‘love’ and ‘gentleness’ and ‘kindness,’ that is equally concerning to humanists as it is for religious folks,” says Speckhardt.

“Definitely, that is not what we want to be seeing, and it is disturbing,” he continues. “So how can we get back to that?”

The problem is especially acute as the bonds of shared communities have also declined, says the culture and religion writer Jonathan Merritt, who has traced the decline of “God talk” across American religious traditions, even among the most devout.

“What is interesting when you look at linguistics is, you will find that a community’s shared vocabulary, its language, will tend to decrease in usage as [the] speaking community gathers less and less,” says Mr. Merritt, author of “Learning to Speak God from Scratch: Why Sacred Words Are Vanishing and How We Can Revive Them.”

Leonard has studied the new “sociology of Sundays,” as the traditional day of worship for Christians has become more a day for weekend and family activities – sports, nature hikes, and other pastimes, he says.

And in this particular moment of political rancor, Millennials and others have also become wary of what they perceive as the politicization of religious faith, especially among the nation’s white Evangelicals, who are overwhelmingly conservative and arguably the most powerful political force in American politics today.

All of this has contributed to the steep decline in spiritual and moral conversations, Merritt says. Even among devout Christians who attend services regularly, only about 13 percent said they had a religious or spiritual conversation at least once a week over the past year, he found in a study he commissioned from the Barna Group, a social research firm in Ventura, Calif.

Overall, Merritt found that nearly three-quarters of all Americans rarely speak of spiritual or religious matters. Of those who do, most only had a couple of conversations over the past year. As in other surveys, he found most said they avoided talking about God altogether because it created tension or heated arguments, or that religion had become too politicized.

Spiritual curiosity among Millennials

But he also found something unexpected, and even hopeful. “The data shows that there is still kind of a spiritual curiosity among Millennials,” says Merritt, who commissioned the study for his new book.

“And I found that fascinating, because you would think, oh, we’re becoming more secular, so the young are less interested in talking about these things,” he says. “But when it comes to these trends, actually you are less likely to talk about God the older you get.”

Part of the reason for this is the fact that older religious folk didn’t grow up in such a pluralistic America. “They don’t know the rules anymore, what’s appropriate to say and what’s not, what’s PC and what’s not.”

Speckhardt, too, has noticed that among his community of atheists and humanists, younger members are also expressing a new interest in discussing morality and similar topics.

“You know, there was this anger, this kind of rejection of religion that went over the top of just saying that we don’t belong to a faith, or just mark ‘none’ as an identity,” he says, noting that many people in his circles felt their former faith betrayed them, or see moral hypocrisy and corruption in the sex scandals in Catholic and Evangelical churches.

Over the past decade, many were drawn to the angry polemics of “new atheist” writers Richard Dawkins and the late Christopher Hitchens, he says.

“But I think that overreaction is fortunately something that I’m starting to see calm down a bit,” Speckhardt continues. “People are like, ‘OK, so I don’t believe. What’s next? How am I going to live my life now?’ And that question, I hope, is going to lead us to a place of more common ground where we can have those kinds of discussions.”

For him, there’s an inherent need for a social species like humans to create social rules, and a biological imperative toward empathy.

“Life’s traumas may also be the continuing places that we all share or revisit the moral and spiritual imperatives that we’ve been hesitant to talk about,” says Leonard. “It can be rooted in our common mortality, and, yes, vulnerability.”

But building a shared moral and spiritual vocabulary also requires that people re-engage with their traditions, Merritt says, and become grounded in a shared moral vocabulary – a prerequisite, in many ways, for seeking points of contact with other traditions.

“I love the idea of America being pluralistic, but that the notion that we are a melting pot in that we all just sort of coalesce together into one kind of meta community, it doesn’t really work,” Merritt says.

“And so what I’m hoping for is that you would have Muslims who are more Muslim than they have ever been, and Jews more Jewish than they have ever been, and Christians who have been more Christian than they have ever been,” he continues. “And each of those communities would be exercising the vocabulary of faith in the particularities of their own communities when they gather.”

Even though Americans have been attending church less frequently, and though those that do now attend in much shorter spans of time, a recent Democracy Fund Voter Study Group report found that religious attendance moderates political attitudes, including the polarizing issues of race, immigration, and identity.

Compared with nonreligious conservatives, far more churchgoing Trump voters said they cared about racial equality (67 percent versus 49 percent) and reducing poverty (42 percent versus 23 percent) than those who did not attend services.

In all religious traditions, regular attendance is correlated with more tolerance. “Frequent participation in religious traditions also appears to bolster more tolerant attitudes and volunteer work among Muslims, Mormons, and Buddhists,” according to a New York Times op-ed by Emily Ekins, polling director for the libertarian Cato Institute.

Define ‘neighbor’

Many of the words that have fallen into decline, Merritt notes, are traditional Christian “fruits of the spirit,” and the concept of love is embodied in Christian understandings of God’s very nature.

Merritt once went to Times Square in New York to ask people to define the word “neighbor,” an important moral concept in Christianity. Christ emphasized the command to “love your neighbor as yourself.”

Conversations grounded in the meaning of moral and spiritual words “would actually equip us to find areas of commonality with adherents of other faiths,” he says.

And people of goodwill, Speckhardt would say.

“I’ve had this repeated kind of experience in these groups where people first have the trepidation, and then the grudging acceptance, and then the, ‘Oh yeah, you’re part of us,’ and then finding ways to seek common ground and a common vocabulary,” he says.

“When we think about the question of those who aren’t religious but who are seeking a moral future,” he adds, “I mean, that is almost the definition of humanism.”

Affordable apartments, good books included? A Chicago experiment.

Sometimes problems that seem completely separate can find a common solution when looked at from a wider angle. In Chicago, that's led to a something unique: a public library with affordable housing.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

-

By Eva Fedderly Contributor

When Chicago Mayor Rahm Emanuel was considering his city’s need to both expand low-income housing and build more libraries, he had an idea. What about combining them? Two years later, the construction of three library-housing projects is nearing completion. Buildings and developments that serve more than one purpose, called mixed use, are trending around the world with the goal of bringing people together and promoting effective use of land. “Co-locating” libraries in particular is common in England and has been used previously in Chicago (with a high school) and in Los Angeles (with housing). Not all Chicagoans immediately welcomed the idea, citing concerns about safety and neighborhood destabilization. At least one developer argued, though, that without the housing, which helps the whole project qualify for tax credits and federal funding, the city lacks the resources to build the libraries alone. With the projects moving forward, other community members see the potential they offer. “Neighborhoods can be insular here,” says Kendra Mealy Wilk, a children’s librarian at the Roosevelt Branch, which is part of the initiative. “So I think this is a wonderful opportunity to bind people together across racial and economic groups.”

Affordable apartments, good books included? A Chicago experiment.

An experiment in Chicago aims to meet the needs of those in search of housing – and a good book.

The initiative pairs libraries and affordable apartments together in the same buildings. Conceived two years ago, the projects are almost complete, with the three libraries set to open at the end of the year, and the housing units – adjacent or above them – to follow in early 2019.

Buildings and developments that serve more than one purpose, called mixed-use, are trending around the world. From urban spaces where residents can simply go downstairs to reach work or food, to a mosque that serves as a community center, the architecture is focused on bringing people together and promoting effective use of land.

“It’s the innovation of the hybrid building that appealed to me,” says Ralph Johnson, design director at the Chicago office of Perkins+Will, which won the bid for one of the library-housing locations, the Northtown Branch building. “It promotes density. Instead of serving one purpose, it has three times the density of use. The buildings are unique in that sense.”

“Co-location” of public libraries is common in England, and has been used previously in Chicago (with a high school) and also in Los Angeles (with housing).

The idea of trying it with public housing apartments in Chicago came to Mayor Rahm Emanuel during a morning swim in 2016. “People were asking me for more libraries, and I knew we needed to bring affordable housing into good neighborhoods so they’re not so concentrated,” he says in a phone interview. Of combining the two, he adds, “If you can’t solve a problem, make it a bigger problem and see if you can solve it.”

The Chicago Public Library and Chicago Housing Authority soon formed an atypical partnership and identified three library locations: The Roosevelt Branch, in Little Italy on the city’s Near West Side; the Northtown Branch, which was struggling to accommodate its high visitor count, in the West Ridge neighborhood; and the Independence Branch, which had burned down, in the Irving Park neighborhood.

When the mayor’s office announced a competition to design the buildings in late 2016, the city received initial proposals from 32 firms. In addition to Mr. Johnson’s group, John Ronan Architects won the bid for the Independence branch, and Skidmore, Owings & Merrill for the Roosevelt location.

Johnson, who designs all over the world, says he loves working in the city he grew up in. “I like to … do important civic work. I’m helping the image of the city and the social purpose of architecture; it’s the notion of a building as a community.”

Although communities have been involved in discussions about the new buildings, the city received some criticism that citizens should have been included earlier in the design process. And not all residents were immediately welcoming of the idea of public housing in their neighborhoods, citing concerns about safety and destabilization.

“There has been buzz about it, some controversial,” adds Shelley McDowell, a homeschooling mom who frequents the city’s libraries. “With ‘affordable housing’ comes a stigma. Some are concerned that it won’t be good for them or their children.”

But at least one developer argued that without the housing, which helps the whole project qualify for tax credits and federal funding, the city lacks the resources to build the libraries alone. And other community members see the idea's potential for revitalization and connecting people.

“Neighborhoods can be insular here,” says Kendra Mealy Wilk, a children’s librarian at the Roosevelt Branch, which will move to its new location once completed. “So I think this is a wonderful opportunity to bind people together across racial and economic groups.”

Chicago Public Library’s director of government and public affairs, Patrick Molloy, says his office’s goal is to remove barriers for people and provide free resources they can access for the rest of their lives. The three libraries plan to offer updated programming and technology for local patrons.

“Through this process we’ve realized that the Chicago Public Library and Chicago Housing Authority’s missions are not that different,” explains Mr. Molloy. “Our mission is to democratize access.”

Mayor Emanuel says he hopes the idea can serve as a successful model for other cities. He discussed it with Houston Mayor Sylvester Turner when the two met in July.

“Mayor Turner is always curious to see if ‘best practices’ in other cities would work in Houston and this one may be part of that effort eventually,” writes Alan Bernstein, communications director for the Houston mayor’s office, in an email. He notes that Turner called the approach “admirable.”

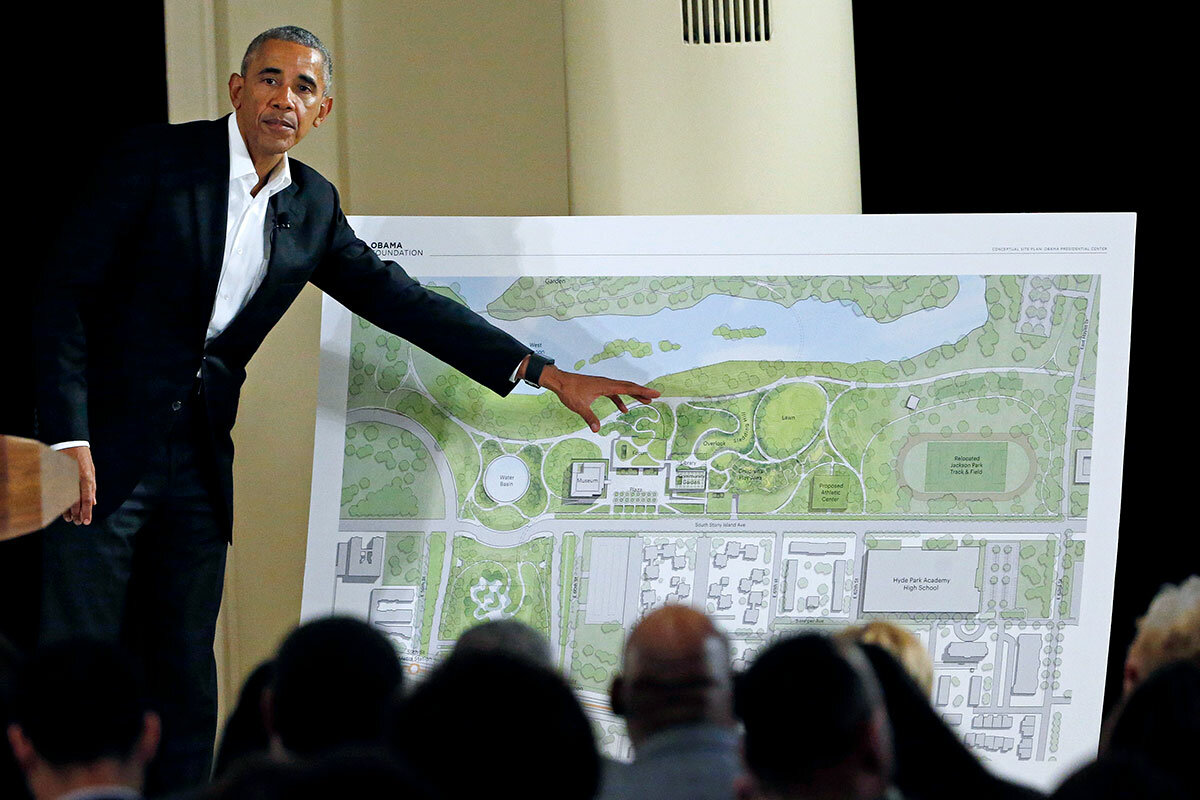

The Barack Obama Presidential Center will be the next Chicago institution to host a new public library. “Soon we’ll have three affordable housing units, one public high school, and one presidential library that will all have neighborhood libraries,” says Emanuel, a former chief of staff for President Obama.

As for Ms. McDowell, the library patron, she is optimistic about the the potential for the housing pairing. “I hope it will help people who don’t have financial security … better their circumstances,” she says. “And for the people who are more affluent, I hope it educates them about other communities and builds bridges between those different social statuses and communities.”

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

A soft way to reform global trade

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

An international meeting that began Wednesday is aimed at changing the rulebook on global trade. Neither the United States nor China, two nations locked in a trade war, was invited. As the host of the two-day confab, Canada decided that 13 “middle powers,” from Chile to Japan, can help the two giants agree to a reform of the World Trade Organization. Such mediation is urgent. The world economy is slowing in part because of trade disputes. And the WTO, founded to grease global trade and lift people out of poverty, may grind to a halt next year without some compromise. The first role of a broker in such negotiations is to help each side understand the other’s core interests and then look for solutions that neither has yet considered. Once the group now meeting in Ottawa reaches consensus on reform, it may be hard for China and the US not to follow. Reshaping the rules of commerce is not always a matter of hard bargaining. It can also entail soft listening.

A soft way to reform global trade

The world’s two largest economies, the United States and China, are currently locked in a trade war. Yet they are also ripping up the global rules on trade.

President Trump threatens to pull the US out of the World Trade Organization if it does not “shape up.” He has already gummed up the agency’s judicial process. Meanwhile, China is violating so many norms of international commerce that it is a defendant in half of all complaints before the 164-member WTO.

No wonder then that neither country was invited to a major international meeting that started Wednesday aimed at changing the rulebook on global trade.

As the host of the two-day confab, Canada decided that 13 “middle powers” from Chile to Japan can help the two giants agree to a reform of the WTO. Canada plans to build up a critical consensus from below, perhaps one that will allow China and the US to better understand each other.

Such mediation – and humble listening – is urgent. The world economy is slowing in part because of the trade disputes. And the WTO, founded nearly 24 years ago to grease global trade and lift people out of poverty, may grind to a halt next year without a compromise on the appointment of new judges to its appellate body.

“Without action to ease tensions and recommit to cooperation in trade,... the long-term economic consequences of this could be severe,” says WTO Director General Roberto Azevedo. And Christine Lagarde, managing director of the International Monetary Fund, has called for a “rapprochement” between China and the US on trade.

The first role of a broker in such negotiations is not to find compromise. Rather, it is to help each side understand the other’s core interests and then look for solutions that neither has yet considered. For starters, China and the US can agree that the world continues to need a rules-based trading system.

The “middle powers” at the Oct. 24-25 meeting in Ottawa have started the process – only without the two superpowers in attendance for now. Once that group of influential nations reaches its own consensus on WTO reform, it may be hard for China and the US not to follow. Reshaping the rules of commerce is not always a matter of hard bargaining. It can also entail soft listening.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Getting to know our spirituality

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Mark Swinney

At a time when spiritual and moral conversation has declined in the United States (see today’s Monitor Daily article on this topic) and other parts of the world, today’s column explores what it means to be spiritual and the healing effect this can have in our lives.

Getting to know our spirituality

It’s easy to feel we are defined by what people believe we are – including how they may look at us as simply a body type, an age, a cultural background, or an online profile parading all the details of our career.

It can sure seem as though we all exist exclusively in a material context. But there’s more to us than that outer crust of surface appearances. We each have a spiritual nature. And there’s more to that spiritual nature than simply an interest in spiritual-type things. I’ve learned from my study of the Bible that God, divine Spirit, is our creator. So spirituality is actually the fundamental nature of our being.

In fact, our identity isn’t truly material at all. As the Bible puts it, God “is before all things, and by him all things consist” (Colossians 1:17) – that is, God has always existed and is the source of all we are. Not just we ourselves, but all of creation consists of and reflects the beautiful, invulnerable, and entirely spiritual elements of God’s substance and nature.

Even a little knowledge of one’s spiritual identity can be helpful in very practical ways. For instance, after a friend of mine woke up feverish in the night, the first thing she did was to begin thinking deeply about her spirituality.

That might sound like a curious thing to do, but experience had shown her that being more conscious of her true nature as God’s child, or spiritual expression, always raises her thoughts into awareness of God’s presence and of what God is doing for her. God, limitless Love itself, is always loving and caring for each of us. And as my friend prayed the following morning, she realized that. And she saw that her true self is not based in materiality and limitation but in God, Spirit. Quickly, the fever completely left her.

Turning to God to learn of our spiritual identity doesn’t mean that we must clench our teeth and work hard to tune out a material version of identity. Instead, we can gratefully recognize that we have been created only as that single, valid version of ourselves that is the exclusively spiritual and perfect creation God, the divine Mind, has made and knows. “There is but one creator and one creation. This creation consists of the unfolding of spiritual ideas and their identities, which are embraced in the infinite Mind and forever reflected,” observes Christian Science Monitor founder Mary Baker Eddy in “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” her groundbreaking book about God, spirituality, and healing (pp. 502-503).

As we understand this more and more, it becomes clear that our God-given spiritual being is such a gift. Throughout the day, as we move from task to task, it is actually possible to remain in vibrant awareness of it. As my friend’s healing shows, becoming conscious of our spirituality has a healing impact in our lives. We see practical evidence of our spiritual nature in our experience, including in our ability to help others. The presence of God seen within us is evidenced in selfless, tireless love for others.

Beautiful, solid spirituality is palpably within us and all around us; and we can see it when we start looking for it. It’s never enough to be satisfied with what the world says we are. In the realm of divine Mind, we continually shine forth with the glory of God. Our identity as Mind’s spiritual idea is nothing less than glorious, immeasurably cherished by God.

It’s a great comfort to recognize that no matter what, the true identity and nature of every single one of us will remain absolutely and utterly spiritual. And we can prove that a little more each and every day as our material beliefs give way to recognizing this spiritual truth.

A message of love

A perfect slice of ice

A look ahead

Thank you for joining us today. We’re working on a story for tomorrow about the suspicious packages sent to CNN, Mr. Obama, and Mrs. Clinton. We’ll also examine how President Trump can maintain a valuable relationship with Saudi Arabia amid the outrage over the death of journalist Jamal Khashoggi.