- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- Why Brexit compromise hasn’t defused political tensions in Britain

- Democrats’ reliance on seniority clashes with enthusiasm for fresh faces

- As US wrestles with definition of ‘sex,’ pushback against trans protections

- Fertilize by drone, till by text: Making tech work for Africa’s farmers

- In refugee flow, Canada finds a surprising solution to a labor shortage

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Helping one another to confront a malaise

The action seems to be picking up along a continuum that runs from disgruntlement to despair. We hear terms like “collective trauma.”

A recent mass shooting feels long ago, partly because of an impatient news cycle – watch for our take on how to avoid normalization of such violence – and partly because that event has been overlaid with others that contribute to a sense of malaise.

Hundreds of residents remain unaccounted for in California’s wildfire zone. We see news of victim-blaming in Ireland and of human rights perhaps imperiled inside the US-Saudi-Turkey triangle. Another fraught election plays out – still – in Florida. Charges mount that Facebook, a virtual second home for so many, failed to protect its digital citizens from bad actors peddling influence.

Where is the counterforce? In real community, some offer. It was door-knocking neighbors and local officials with bullhorns, for example, who warned many to flee ahead of fast-moving fires.

What hope for those who feel overwhelmed? A Highline story by Jason Cherkis this week explains how simple, undemanding outreach – by letter, by text – can subvert the “seductive logic” of suicidal thoughts for those who feel pushed that far down. One young caregiver, Ursula Whiteside, studied patients’ treatment histories and confirmed a recurring need. “Each one, she felt, was desperate for any form of help or kindness.”

The newsletter Daily Good offered another balm this morning. “Showing respect to individuals,” one source declared, “has a kind of healing power.”

Now to our five stories for your Friday, including a look at expanding long-held social definitions in the US, at reframing agricultural innovation in Ghana, and at harnessing the power of migration in Canada.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Why Brexit compromise hasn’t defused political tensions in Britain

Theresa May’s deal on Brexit sought to balance national sovereignty and economic interdependence. Reactions to it raise a question: Is that even possible in today’s Britain?

It has been more than two years since British voters chose in a referendum to leave the European Union. This week, the government unveiled the Brexit deal it has negotiated with its EU partners, but the agreement has only exacerbated the bitter discord that has long dominated domestic debate over Britain’s relationship with Europe. Brexiters say they want to “take back control” of British affairs from EU bureaucrats in Brussels and to restore sovereignty to Parliament at Westminster. But the economic consequences of a complete break from the EU, after 45 years of union, would be disastrous, almost everyone agrees. Prime Minister Theresa May says that her compromise deal wins back as much sovereignty as possible while maintaining the country’s economic equilibrium. But her “half-in-half-out” deal with Brussels has satisfied nobody in the UK, neither those who want to leave the EU nor those who would rather stay. Tensions between a desire for political sovereignty and the strength of Britain’s economic ties with the EU are no closer to being resolved.

Why Brexit compromise hasn’t defused political tensions in Britain

Two years after Britain voted in a highly charged referendum to leave the European Union, its government this week agreed to a draft treaty with the EU to make that choice happen. But the deal has still not resolved deep divisions here over what Brexit could, or should mean.

This week’s political chaos in London, replete with ministerial resignations, has exposed the tensions between full-throated calls for unfettered British sovereignty and the reality of Britain’s economic dependence on the EU, which is its closest and largest trading partner.

On Wednesday, as Theresa May urged her reluctant cabinet to back the agreement, scores of noisy protesters gathered near 10 Downing Street, the Georgian townhouse that is the seat of executive power and a symbol of Britain’s historic reach across the globe.

Ms. May’s half-in, half-out Brexit is designed to blunt Brexit’s economic blow to Britain. But that’s not what Sarah Mayall, holding aloft a white placard reading “Leave Means Leave,” says she wanted in 2016 when she ticked the box to leave the EU. “It’s not an economic goal. It’s a sovereignty goal,” she says.

To Ms. Mayall, the UK-EU agreement is a betrayal. She is appalled that it would leave Britain in a transitional customs union with the EU after its formal exit from the union next March. That is designed to avoid a rupture in cross-border trade and a crash in business confidence, but it will prevent London from negotiating its own sovereign trade deals with the US and other major economies.

The question of sovereignty, and where Britain stands in relation to the rest of Europe, casts a long shadow in this proud island nation. The way that Britain has ceded legal and regulatory powers to the EU in return for access to the world’s largest trading bloc has long rankled some. But a rising tide of prosperity dampened much of the criticism until the 2008-09 recession unleashed a populist wave that found its target in EU membership and European immigration.

Squaring the circle

Now Ms. May, who has a slim majority in parliament, is struggling to strike a balance between a return of British sovereignty and defending British prosperity. But the compromise accord she presented to parliament on Thursday is unlikely to square this circle, says Helen Thompson, a professor of political economy at Cambridge University.

“The difficulty we’re now in goes back to the difficulty when Britain joined [in 1973]. It’s very difficult to deal with a constitutional question,” she says.

A strong current of euroskepticism courses through May’s center-right Conservative Party. For decades, anti-EU politicians argued that Britain should leave the Union and reassert its national sovereignty, even if less trade with the EU made Britain poorer. In recent years, however, this argument for democratic control has been embellished with another claim, that Britain could strike better trade deals outside the EU, and grow richer.

MP’s who “saw this as a governance issue as much as anything else” have been superseded by “a kind of Conservative euroskeptic who puts equal weight on trade,” says Ms. Thompson.

As they campaigned for the 2016 referendum, anti-EU politicians knew they couldn’t rely just on the minority of voters who prized sovereignty over the benefits of trade integration.

So they made attractive promises. One of the top reasons to vote “Leave”, they claimed in campaign literature, was that “We'll be free to trade with the whole world.… We'll be free to seize new opportunities, which means more jobs.”

This political messaging sowed the seeds of the current impasse over an orderly EU exit, says Alex White, a partner at Flint Global, a financial advisory firm. “To win a referendum they had to win different constituencies, and they had to make an economic case,” he says.

“I think it was always inevitable.... It was going to be very difficult to meet the demands of all these different [political] tribes.”

‘Brit-politics’ dilemma

That challenge was underlined Thursday by the resignation of Dominic Raab, the Brexit secretary, and other cabinet members. Parliament must approve the withdrawal agreement with the EU, and a rebellion in May’s own ranks now makes that hard, if not impossible, to achieve without votes from the opposition Labour Party.

On Wednesday, Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn goaded May in Parliament over the “backstop” in the agreement to maintain an open border between Ireland, an EU member, and Northern Ireland, which is part of the UK. He drew attention to the fact that the deal would not safeguard “the sovereign right of any UK parliament to unilaterally withdraw from any backstop” without EU approval, a concern that resonates with Brexit supporters in the ruling Conservative Party.

May insisted that the backstop would be temporary. She told lawmakers they had a choice between backing her treaty or facing economic chaos. “The choice is clear. We can choose to leave with no deal, we can risk no Brexit at all, or we can choose to unite and support the best deal that can be negotiated,” she said.

The divisions in the ruling Conservative Party over Europe are mirrored across the aisle. Labour accuses the government of doing a bad job of negotiating Brexit terms, yet the opposition has been short on concrete proposals, leading many to believe that its strategy is to hasten a political crisis and an election that it can win. Most Labour MPs, including some who campaigned to stay in the EU, represent districts that voted to leave and where sovereignty and borders remain potent issues.

“That’s the dilemma for Brit-politics. Brexit has cut across both of the main parties’ constituencies,” says Matthew Goodwin, professor of politics at the University of Kent and coauthor of National Populism: The Revolt Against Liberal Democracy.”

Mayall, the protester, agrees with euroskeptic MPs who prefer that Britain simply leave the EU and revert to World Trade Organization terms of trade. It’s a scenario that alarms her employer, an asset management firm, she says. Most financial services companies are aghast at the idea, and some have already moved jobs elsewhere in Europe.

But Mayall says she prefers this solution to Britain’s agonizing and continuing battle over EU membership. “If we don’t leave and make a clean break, this issue won’t go away,” she says.

Democrats’ reliance on seniority clashes with enthusiasm for fresh faces

This piece looks at a paradox: Democratic voters skew younger, and the party prides itself on its young up-and-comers, but its leadership on Capitol Hill is long entrenched. That may be about balancing faith in experience with trust in new players.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

On the Republican side, House members can advance quickly in committees because their chairmanships are subject to term limits. It’s what helped Paul Ryan grab the Budget Committee gavel when he was in his mid-40s and then become the youngest House speaker in more than a century. In contrast, Democrats rely on seniority – and Americans are about to see some senior Democrats take over, including octogenarians Maxine Waters of California, expected to become the next chairperson of the Finance Committee, and Nita Lowey of New York, expected to head the powerful Appropriations Committee. Yet a growing chorus of Democratic voices are calling for fresh leadership even as the caucus looks set to elect the same trio of septuagenarian leaders, including Nancy Pelosi in the top position, when they return from Thanksgiving recess. The challenge is that the upper rungs of the ladder have been filled for so long that no one comes close to matching Ms. Pelosi’s experience. “I’d like to see more younger, newer members at the table,” says Rep. Eric Swalwell (D) of California. “But as I see it, right now, we’re in the ninth inning, it’s a tight game, we want our best in there.”

Democrats’ reliance on seniority clashes with enthusiasm for fresh faces

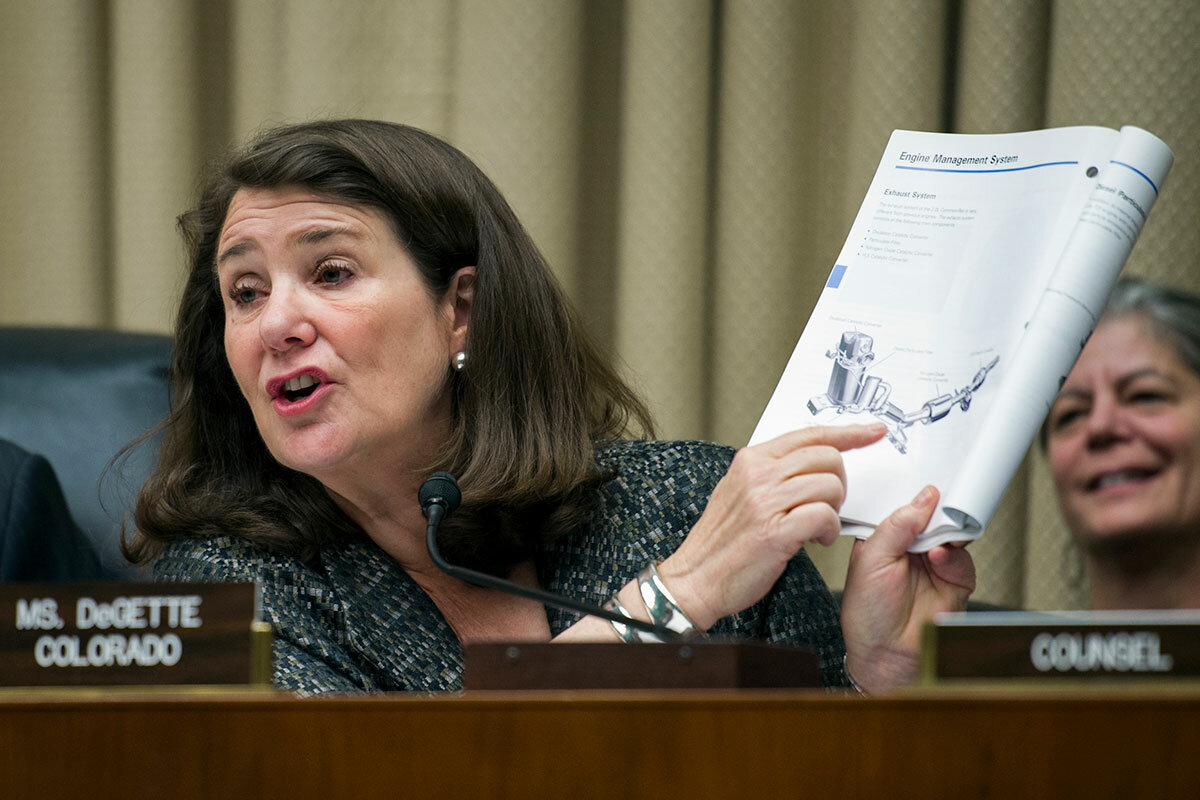

Rep. Diana DeGette, Democrat from Colorado, is done with waiting.

For “probably” 12 years, she says, she’s aspired to one of the top three jobs in the Democratic leadership. But these positions have been occupied by the same three people – all of them now in their late 70s – for more than a decade.

Now that Democrats have won the majority in the House, Congresswoman DeGette is making her move – challenging a powerful member of the troika for the No. 3 slot, the “whip,” or chief vote counter. DeGette has been on her party’s whip team since she arrived in Congress more than 20 years ago, and before that when she was in the Colorado legislature.

“What I love to do is whip,” she tells a clutch of reporters, describing the satisfaction of building coalitions and rounding up members to get bills passed. “I’ve been known to whip a dinner party!”

DeGette reflects an eagerness for change and opportunity among Democrats, even as the caucus looks set to elect the same trio of septuagenarians to the top three positions when they return from their Thanksgiving recess: Nancy Pelosi of California, Steny Hoyer of Maryland, and James Clyburn of South Carolina. The desire for fresh leadership is most vocally expressed by a faction seeking to block minority leader Pelosi from becoming speaker. Their motivations vary, from fulfilling campaign promises not to back the vilified Californian to complaints about how the caucus and the House are run.

But underneath it all is the matter of generational change. Even the pro-Pelosi camp recognizes that the public face of the party doesn’t match that of young voters who turned out in numbers not seen for at least 25 years in a midterm election. And Ms. Pelosi herself is promising to be a “transitional” speaker to a new generation of Democratic leaders – though she hasn’t specified a time frame.

“If a voter looks at the Republican party and says, ‘Those leaders are my parents’ age,’ and they look at the Democratic party and they say, ‘Those leaders are my grandparents’ age,’ that’s not the best image to present to younger voters,” says Matthew Green, an expert on the speakership at Catholic University in Washington.

Other Democrats are qualified for the job of speaker, Professor Green says. But the top rungs of the ladder have been filled for so long, including Pelosi as leader for 16 years, that no one comes close to matching Pelosi’s experience – her legislative chops, her previous role as speaker under Presidents Obama and Bush, and her time negotiating with President Trump.

To date, no one has declared an intention to run against her.

“I’d like to see more younger, newer members at the table,” says Rep. Eric Swalwell of California, who is the youngest member of the broader leadership team. “But as I see it, right now, we’re in the ninth inning, it’s a tight game – we want our best in there.”

Ask Pelosi about preparing the next generation to assume positions of authority, and she says she’s always done that, and that Democrats have a “whole new brigade” who will make their mark in committees and elsewhere. She points to her record of appointing women, people of color, LGBTQ people.

“Nobody mentions the fact that right away I made Eric Swalwell, in his thirties, in the top leadership as co-chair of the Steering and Policy Committee” – a powerful panel that sets the policy agenda and nominates members to committees. “I’m proud of my record in that regard. I know how to do it, and now that we have the majority and we have more capacity, we can do more,” she says, hustling along a corridor, a trail of reporters following her.

Two years ago, when Pelosi faced an uprising in her ranks and 63 members backed Rep. Tim Ryan of Ohio for minority leader instead of her, she created a slew of new leadership positions, reserving some for younger members. Those jobs have given visibility and some influence to rising stars like Hakeem Jeffries of New York, and Cheri Bustos of Illinois. Both are using their positions as a springboard to launch campaigns for other top jobs in the Nov. 28 Democratic caucus elections.

But Rep. Marcia Fudge of Ohio, who is in the “Never Nancy” camp and is herself considering challenging Pelosi for speaker, scoffs at those efforts to give leadership experience to fresh talent.

“You don’t do it by just creating more and more and more positions that really have no real authority. I think what you have to do is give young people authority,” Congresswoman Fudge, a former chair of the Congressional Black Caucus, told reporters earlier this week. “We have a lot of very bright young people in this caucus, and everybody knows it. But it’s very difficult to move up in an environment where the same people run everything all the time.”

In the Republican House caucus, newer members have a chance to advance in committees because the chairmanships are subject to term limits. It’s what helped outgoing Speaker Paul Ryan of Wisconsin grab the Budget Committee gavel when he was in his mid-40s, and then go on to become the youngest House speaker since 1869.

In contrast, Democrats rely on seniority – and Americans are about to see some senior Democrats take over, including octogenarians Maxine Waters of California, expected to become the next chairperson of the Finance Committee, and Nita Lowey of New York, expected to head the powerful Appropriations Committee.

The seniority system has been vigorously defended by the Congressional Black Caucus, and observers say it would be very tough to change. But some members say the party needs to find a “sweet spot” between term limits and seniority.

Outgoing Democrat Michelle Lujan Grisham – soon to be sworn in as New Mexico’s next governor – says she has seen the advantages and disadvantages of both: seniority provides experience, but blocks the funnel to leadership; term limits provide opportunity, but can result in a deficit of experience. This year, term limits tangibly hurt Republicans by creating an incentive for lawmakers whose committee chairmanships were expiring to retire.

“Somewhere [in between] is a happy medium,” says Congresswoman Lujan Grisham.

Meanwhile, Pelosi is trying to fend off a potential challenge, meeting with various caucuses, hosting the newcomers and their spouses at a private dinner in the Capitol’s Statuary Hall, and asking Democratic luminaries to call members-elect on her behalf (she is meeting privately with them as well).

Her opponents say they have 17 signatures on a letter opposing her, and even more commitments beyond that – enough, they say, to deny her the 218 votes she will need for the speakership when the entire House votes on Jan. 3. Some reportedly have indicated it would help if they knew how long she planned to hold the speakership (only until the next election?) and what exactly her transition plan is.

One complicating factor: Democrats in the bipartisan Problem Solvers caucus who are demanding rules changes to foster bipartisanship in exchange for their support. Pelosi and the Problem Solvers met and seem to be moving in the same direction, with the group waiting for a written response from her. The Republican co-chair of the group, Rep. Tom Reed of New York, has said he and some other Republicans will cast votes for Pelosi for speaker if she meets the Problem Solvers’ demands.

Never flinching, Pelosi, at least publicly, exudes supreme confidence that she will indeed be the next speaker. Part of her strategy seems to be to give the naysayers every opportunity to publicly voice their opposition. Former House historian Ray Smock says that could include going into rounds of extra balloting on the floor – not unprecedented – if need be.

“Some of this is about giving people the space to make a U-turn,” says a senior Democratic aide.

And while the internal division may trouble some Democrats, others view it as healthy – for the party and the House.

“The positive side of this tussle over leadership is that we’re on the verge of seeing fundamental reform in rules that will open up the process,” says former Democratic Rep. Steve Israel of New York, who retired from Democratic leadership to pursue a career as a writer.

“Is it about Nancy Pelosi? For some it is. But for others, it’s about whoever leads the House and will open the process.”

A deeper look

As US wrestles with definition of ‘sex,’ pushback against trans protections

Questions about personal liberty and self-determination abound on both sides of this argument – for transgender people and for those who believe that gender is inherently binary and fixed at birth.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 11 Min. )

-

Harry Bruinius Staff writer

It’s been in many ways a remarkable past few years for transgender people, and much of American society seems to be inching toward inclusion. At least 20 states explicitly prohibit discrimination on the basis of gender identity, and on Election Day, 68 percent of Massachusetts residents chose to keep its civil rights protections in place. The Trump administration, however, has pushed back. In a memo, the administration proposed a legal definition of sex in federal civil rights laws that was in many ways the precise opposite. A person’s identity as a male or female is rooted in “immutable biological traits,” the administration said, and proven by the sex marker assigned on a person’s birth certificate. In many ways, the word “immutable” underlies much of the national conversation about transgender and gender nonconforming people today. To supporters of transgender rights, the idea of immutable biological sex is something bound to evolve, just as views of homosexuality did a decade ago. For conservatives, the immutability of sex has deep roots in Western ideas of an ordered reality. As those two views clash, US society is struggling to find common ground. “There is a very large cultural anxiety around gender fluidity,” says Kyle Velte, professor at the University of Kansas School of Law in Lawrence. “But where does that cultural anxiety come from? Why are we so scared of gender fluidity?”

As US wrestles with definition of ‘sex,’ pushback against trans protections

Aleksandra Burger-Roy was genuinely shocked when she first heard about Question 3 on the Massachusetts ballot. The initiative asked voters if Massachusetts’ law preventing discrimination in public places should continue to include transgender people.

She’s been harassed and called gender-based slurs since she moved to Boston to study chemical engineering, but she generally considers it a safe place to be transgender, especially compared with the small town in Maine where she grew up.

“I continued to be shocked when the polls said that it’s close,” says Ms. Burger-Roy, a student at Northeastern University. She trusted Massachusetts voters to keep the law, but it concerns her that the group behind the ballot question was able to collect more than 50,000 signatures to put it on the ballot in the first place.

It’s been in many ways a remarkable past few years for transgender people, and much of American society seems to be inching toward inclusion. At least 20 states explicitly prohibit discrimination on the basis of gender identity – and on Election Day, 68 percent of Massachusetts residents chose to keep its civil rights protections in place. In Vermont, while Christine Hallquist lost, she made history as the first transgender candidate for governor nominated by a major party. From Virginia to California, more transgender candidates are being elected to statehouses and city councils.

The nation’s top businesses, too, have begun to make transgender-inclusive health care a standard part of the benefits they offer. Today more than 750 major US employers offer such coverage, compared with 49 companies in 2009, according to the D.C.-based Human Rights Campaign, which advocates for LGBTQ rights.

The Trump administration, however, has pushed back. It has been recalibrating how it enforces the nation’s civil rights laws, rolling back Obama-era directives that stated the core civil rights category of “sex” included gender identity and expression, even if those traits don’t align with someone’s sex assigned at birth.

In a memo made public last month, the administration proposed a legal definition of sex in federal civil rights laws that was in many ways the precise opposite. A person’s identity as a male or female is rooted in “immutable biological traits,” the administration said, and definitively proven by the sex marker assigned on a person’s birth certificate.

In many ways, the word “immutable” underlies much of the national conversation about transgender and gender nonconforming people today. To supporters of transgender rights, the idea of immutable biological sex is something bound to evolve, just as views of homosexuality did a decade ago. For conservatives, the immutability of sex has deep roots in Western ideas of an ordered reality, both as a theological attribute of God and as a description of the laws of nature.

As those two views clash, US society is struggling to find some common ground from which to craft transgender law and policy. And the 32 percent “No” vote Nov. 6 in liberal Massachusetts – the first state to legalize same-sex marriage – shows that ferment is not yet near resolution.

“There is a very large cultural anxiety around gender fluidity,” says Kyle Velte, professor at the University of Kansas School of Law in Lawrence. “But where does that cultural anxiety come from? Why are we so scared of gender fluidity?" Professor Velte asks, saying part of the answer stems from fear of a state of chaos.

“And I think that’s a really complicated question.”

“It could start with something as simple as, you know, ‘If I don’t have this [male-female] binary to define myself, then what does that say about me as a man?’ ” says Professor Velte, who studies the intersection of sexuality, gender, and the law. “What does it say about power? What does it say about gender discrimination? Masculinity is constructed in such a narrow way today, as is femininity, so that I think it scares people to think about a gender continuum, which is really the reality out there.”

For some scholars, this is a question of personal liberties – both for transgender people and for those who believe that gender is inherently binary, fixed, and based on the sex assigned at birth.

“Our minds and senses function properly when they reveal reality to us and lead us to knowledge of truth,” writes bioethicist and political philosopher Ryan Anderson in his book, “When Harry Became Sally: Responding to the Transgender Moment.” “And we flourish as human beings when we embrace the truth and live in accordance with it. A person might find some subjective satisfaction in believing and living out a falsehood, but that person would not be objectively well off.”

He argues that numerous lives have been “irreparably harmed” by medical transitions, citing the voices of those who “detransitioned,” or tried to reverse medical changes to their bodies and return to living as their sex assigned at birth. He also explores the rates of “desistance,” especially in children who eventually grow out of gender nonconforming behaviors and gender dysphoria.

Still, as a senior research fellow at the Heritage Foundation in Washington, Mr. Anderson also places a high value on personal autonomy and liberty. He thinks transgender people should be able to live their lives as they see fit, and should be treated with dignity and respect.

“But there are two things to separate here,” Anderson says in a Monitor interview. “The one is, should people be free to live out their gender identity as they understand it? The answer is, yes. If Bruce wants to live as Caitlyn, it’s a free country and adults are free to live how they want.”

“The second question is, however, should our antidiscrimination laws coerce other people into affirming that Caitlyn is a woman?” he continues. “Or will freedom be a two-way street?”

‘Dear Colleague’

In 2016, the Obama administration issued a “Dear Colleague” letter to federally-assisted schools and instructed them to respect the gender identity of all students and to address them with their preferred pronouns, even if official records listed them otherwise.

And in a move that outraged conservatives, the Obama administration also required that schools allow transgender students to participate on the sports teams and use bathrooms and locker rooms that aligned with their gender identity.

In the past 15 years four United States Courts of Appeals have ruled that transgender people are protected from employment discrimination by Title VII of the Civil Rights Act. They found that making a hiring decision because of someone’s transgender or gender nonconforming identity is discrimination on the basis of sex, referring to a 1989 Supreme Court decision that found that discrimination based on gender expression – how someone presents themselves with clothing, accessories, and behavior – was illegal.

Some conservative thinkers say the Trump administration memo is a corrective to what they see as capricious changes to the definition of sex.

“[Academics] and activists have been running around willy nilly changing the definition of sex,” wrote David Marcus at The Federalist last month. “It is farcical to think that the state can somehow keep up with such changes or pursue policies regarding sex without a workable and consistent definition.”

“In effect, [the definition] will mean that this objective standard will replace a hodgepodge of rules, regulations, and definitions of gender as it pertains to the federal government,” Mr. Marcus wrote.

From a very different point of view, the idea of an “immutable” order behind ideas of biological sex stands behind the reasoning of many transgender advocates and others.

“On one hand, our collective notions of maleness and femaleness are presumed so obvious that they need not be explained,” says Heath Fogg Davis, associate professor of political science at Temple University, and the director of its Gender, Sexuality, and Women’s Studies program. “On the other hand, the criteria for who is a woman and who is a man are so elusive that they cannot be explained without sinking into a morass of doublespeak and tautology.”

“And I am a huge advocate for gender self-determination,” says Professor Davis, author of the 2017 book “Beyond Trans: Does Gender Matter?” “Some people interpret that as, I want to get rid of gender altogether. But it’s kind of the opposite.”

“That individual autonomy, that say in who you are, in terms of who we are as a society, I think, that is so incredibly important,” he continues, critiquing the Trump administration’s efforts to define immutable biological sex.

The idea of transferring the authority to make those judgments to government agencies, especially civil servants “who will need to keep track of and inspect our genitals to designate and confirm our sex classification – this should be a hard sell, even and especially to religious conservatives,” Davis says.

Protections from Anchorage to Helena

As the visibility of transgender and nonbinary people has increased, policy has followed, says Shelby Chestnut, co-director of policy and programs at the Transgender Law Center in Oakland, Calif. Areas of the country that many wouldn’t consider progressive, such as Anchorage, Alaska, and Montana, have recently ensured that transgender people are protected from discrimination.

“There’s also been a huge movement in many states, particularly on the West Coast, around ... expanding gender markers beyond binary male and female, and real movement to explain that as a valid existence,” said Mx. Chestnut, who identifies as a transgender nonbinary person, meaning that they don’t see themselves as a man or a woman. They prefer to use the gender-neutral honorific.

Scholars often distinguish between the biological markers of “sex” and the variable cultural expressions of gender.

“Sometimes the two terms are used interchangeably, and I get that, because they’re correlated,” says Stephanie Sanders, an expert in biopsychology at Indiana University in Bloomington.

Yet even when considering the biology of sex, things aren’t necessarily simpler, Dr. Sanders says. She calls the definition of male and female a “social-medical convention.” The assertion that a sex of male or female can be universally declared based on biological features visible at birth is contrary to the current understanding of chromosomes, organs, brain structures, and genes, all of which contribute to biological sex, she says.

“Even if we’re just talking about biology, we have to acknowledge that there are these multiple dimensions, and we also have to acknowledge that we don’t know everything yet,” she says. Still, she adds, “neither sex nor gender is binary – there is a spectrum,” and words like “immutable” and “fixed” do not easily line up with current science.

Anderson, too, sees an important distinction between sex and gender, and agrees that a rigid masculine-feminine binary can be socially destructive.

“Sex is a bodily reality, and gender is how we as a society, as a culture, and as individuals give expression to that bodily reality,” he says. “But there are two kinds of errors to avoid: The one extreme would be rigid sex stereotypes where men are from Mars and women are from Venus, that boys are supposed to play with G.I. Joe and girls are supposed to play with Barbie.”

“On the other extreme would be an androgynous understanding,” he continues, “where men and women are interchangeable. There are no differences. Somewhere, a sound understanding of gender would avoid those two extremes as we try to think about, where do the sexual differences embodied as male and female make a difference for society?”

Northeastern student Burger-Roy says her own gender is “relatively simple” compared with other transgender people she knows.

Many now identify as nonbinary – including genderfluid, genderqueer, and gender nonconforming – terms used to separate oneself from a binary that’s built on biology. Burger-Roy, however, says she is a woman, plain and simple.

“People who grow up in the West know what a woman is,” she says, invoking the traditional cultural binaries that define expressions of gender. Like other students who are part of groups like Northeastern Pride, Burger Roy says one of her deepest desires is just to be able to live a comfortable and fulfilling life like anyone else.

‘Epidemic of violence’

There continues to be an “epidemic of violence” against transgender people, including bullying, harassment, and assault, according to Human Rights Campaign. This year is on track to see a record number of transgender people murdered, primarily trans women of color.

While studying in New Hampshire, Matt Storm says he was the target of a group of students who intended to do him physical harm. They did not succeed, says the D.C.-based transgender artist and photographer, but the incident made him aware of how his gender may impact his safety in different environments.

Along with violence, reports have found that many transgender people face economic and societal challenges. A study of the trans population in Washington found that 46 percent of trans people living in the city make less than $10,000 a year.

Mx. Storm hopes that the increased national conversation around transgender issues will lead to the creation of resources that benefit the community, such as medical research and educational resources for trans youth kicked out of their homes.

“We’re definitely seeing a moving social conversation, but we’re not necessarily seeing that benefit the lives of the most marginalized transgender people,” he says.

At the same time, one of the most vocalized fears is that antidiscrimination protections for transgender people will enable a man to pretend to be a transgender woman to gain access to women’s bathrooms and locker rooms, and then assault women or girls.

But researchers say that there is no evidence that any transgender person in the US has used their gender identity to gain access to a restroom to commit an assault. [Editor's note: The previous sentence has been clarified for accuracy.] And according to a new study from the Williams Institute at UCLA School of Law, there is no evidence that allowing transgender people to use public facilities aligning with their gender identity has had any effects on safety.

“What they’re articulating is that trans women are not really women, they’re just men in dresses, and they’re going to go into restrooms and they’re going to hurt and harm our precious women. So it’s based on transmisogyny and on sexism,” says Z Nicolazzo, an assistant professor for Trans* Studies and Education at University of Arizona.

Alex Marzano-Lesnevich, an author and professor at Bowdoin College, identifies as genderqueer. They’ve known that they did not fully relate to the gender they were assigned at birth for many years, but only came out recently after becoming more aware of nonbinary identities. “I felt grief, really, for not having language to identify what it was [that I felt],” says Mx. Marzano-Lesnevich, author of “The Fact of a Body: A Murder and a Memoir.” They first thought they must be a transgender man because they were unhappy being perceived as a woman. It was only in time, and with the help of friends and partners, that they recognized they could exist outside both of those binary identities.

Even though Burger-Roy sees herself in terms of a traditional gender binary, she thinks it’s “really cool” that so many of her peers understand their identity in a fluid and a decidedly mutable way.

“Personally, I can’t imagine my gender changing at all, it just feels so innate, so deeply rooted that I don’t – I can’t feel as if my gender would ever change, and I don’t feel it ever has,” Burger-Roy says.

“But not everyone’s experiences are the same, not everyone may feel it as a deeply rooted thing,” she continues. “The big thing is to understand that not everyone’s experiences are the same, and only they can be the person who has a say into what their gender is.”

Fertilize by drone, till by text: Making tech work for Africa’s farmers

Sometimes we talk about automation and job rates as though they’re in a zero-sum game. But successful innovation does more than develop new technology; it figures out how to boost workers, too.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

-

By Stacey Knott Contributor

Uber for tractors? That’s the premise of TROTRO Tractor, a company in Ghana. And in communities where small farms do most work manually and would struggle to buy their own vehicle, it hopes to be a game changer. Farmers in Africa tend to have access to significantly less mechanized equipment than those elsewhere. Today there is a push to change that, from TROTRO’s tractors to fertilizer drones, all of which could boost harvests and bigger-picture food security. But here, as around the world, mechanization also comes with fears about jobs being replaced by machines. Half of the continent depends on agriculture for all or part of their livelihood, according to the United Nations, and unlike in many other regions, that number is holding steady. But with the right planning, taking specific communities’ needs into account, many are hopeful that mechanization will yield better jobs and more of them. TROTRO has an ultimate aim, CEO Kamal Yakub says with a grin. “We are going to put the cutlass and hoe in the museum so that our children will come in 20 years and say, ‘What's the use of this?’ ”

Fertilize by drone, till by text: Making tech work for Africa’s farmers

Daniel Asherow eyes a large white drone as it buzzes above his rows of pineapple plants, methodically spraying fertilizer into green stems that will soon produce juicy fruits for export. The drone hovers a few feet in the air, covering in 15 minutes the same ground that usually takes five workers an hour.

Around the world, agriculture is becoming ever-more mechanized: from robot-run farms in Japan, to artificial intelligence-tracked pigs in China, to strawberry-picking machines in the United States. Here in Ghana, in rolling plains of pineapples a few hours northeast of Accra, high-tech farming innovations are still in their early days. The potential long-term gains are especially crucial for sub-Saharan Africa – but also, the prospect of short-term farming job loss is especially severe.

Half of the continent depends on agriculture for all or part of their livelihood, according to the United Nations Agriculture in Africa 2013 report. And unlike in many other regions, that number isn’t waning: agriculture has absorbed half of all new entrants to Africa’s workforce over the past 30 years. By 2050, the continent’s population is expected to grow by more than 1 billion – people who need greater food security, but also jobs. Yet nations where mechanization becomes the norm have typically seen drastic drops in agricultural employment.

But a crop of entrepreneurs are pushing to re-envision sub-Saharan Africa’s agriculture, increasing mechanization in ways that not only increase productivity and incomes, but ultimately create better jobs: not hand-tilling the fields, but flying the drones. For that to work, financing, training, infrastructure, and supportive policies are needed across the continent, with solutions that target particular communities. Not everyone needs to own the equipment, they just need to have access to it: from portable mills, to shared tractors.

Mechanization is “not only needed – it’s urgent,” says Alex Ariho, chief executive of the Ghana-based African Agribusiness Incubators Network.

Farming from above

Today, Mr. Asherow is just trying out the drone. But it comes at a good time, he says, as he’s struggled to attract new workers lately. Unlike many African countries, Ghana has already seen a drop in farm-labor supply, as a result of urbanization. In the early 1990s, agriculture was 56 percent of Ghana’s total employment; today it is 40 percent. Young people who once would have looked for farm work are now heading to urban areas, he says, where they can find jobs like driving mototaxis. He hopes that drone jobs prompt young workers to take another look at farming.

Still, some workers’ fears about being replaced by technology are justified, he says. “Those who have been working on a farm for a long time without the requisite training, it will be difficult for them to be absorbed.”

He anticipates employees coming to him with concerns over their jobs being replaced by machines. But pineapple-growing still relies on “a lot of areas for manual work – the planting and initial jobs to get the plant established.”

Much of sub-Saharan Africa’s agriculture today focuses on low-tech labor, with little post-harvest processing; most crops are sold in their raw form to local markets, or exported. Farmers here have 10 times fewer mechanized tools per farm area than farmers in other developing regions, according to the African Development Bank Group. Better technology could spur more processing, distribution, and marketing, all of which could create more jobs, agricultural experts say. But it also stands to boost food security. Africa has the world’s highest share of food waste, due in large part to problems like cold storage. Crop loss has become a significant problem in the face of climate change.

As in many parts of the world, the rise of mechanization has spurred concerns about job losses. Sheryl Hendriks, a food security expert at the University of Pretoria, says those worries are rooted in “a fear of change, rather than facts.”

“If you release labor from a very tedious, drudgery-based part of the system, you have an opportunity to create jobs elsewhere,” she says.

Back on Asherow’s farm, pilot Valentine Klutse walks along the rows of the crops, mapping out coverage. He then mixes the fertilizer with water and pours it into a tank beneath the drone’s blades. With a few simple clicks on the controller, the drone is buzzing up in the air, releasing the treatment through nozzles.

The drone belongs to AcquahMeyer Aviation, the brainchild of Ghanaian entrepreneur Eric Acquah and his wife Tracey Meyer, the company's chief operating officer. While living in Germany, the duo used to see Ghanaian produce on the shelves at their local supermarkets. But they suddenly saw a drastic decrease, linked to the European Union’s 2015 two-year ban on five Ghanaian vegetables. Farmers were not sufficiently spraying their crops, an agronomist told them, which had led to infestations. Determined to see Ghanaian exports back in European supermarkets, they launched their company in 2017.

While they are still in their first year of business, demand is booming.

“It's something that the agriculture industry was waiting for. We came in at the right time with the right technology,” Mr. Acquah says.

The company has also sprayed pesticides, preventing rapid crop loss.

“The manual sprayers will need five days; half the farm will be gone by the time you complete it,” Acquah adds. “When we come in with a two-acre farm we can spray it in 15 minutes and kill the insect before they kill the farm.”

While sprayers’ jobs might be lost due to the drones, higher yields could yield new positions in processing, transport, packaging, and selling. The company has plans of employing close to 2,000 people across Ghana. Drones are currently designed and made in Germany, but Acquah wants to build a factory in Ghana to assemble them.

Tractor by text-message

Hire, rent, or share technology – don’t buy. That’s the premise of Acquah's drone operation, as well as Ghana’s TROTRO Tractor. The Uber-like service links farmers with tractor owners via mobile phones.

“It's more of removing the tedious nature of work and bringing in more people to enter into the business so it's not taking away jobs, it's creating more jobs,” says chief executive Kamal Yakub, who adds he has trained or employed around 250 people in Ghana to operate the tractors.

This year, with funding from the NGO Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa, they have focused on Ghana’s Upper West Region, a poor area along the northern border with Burkina Faso. He noticed the service could be a game-changer for women in particular, who run their households while farming with a simple cutlass and hoe. For about $50, women could plow a two-acre farm with a tractor, saving around a week’s labor.

It seemed like the first time many of them had been offered access to a tractor, he says, and suggests patriarchal beliefs were at play. But when someone requests a tractor via text message, you “don't know who is there – it’s first come, first served.”

The company has an ultimate aim, Mr. Yakub says with a grin. “We are going to put the cutlass and hoe in the museum so that our children will come in 20 years and say, ‘What's the use of this?’ ”

In refugee flow, Canada finds a surprising solution to a labor shortage

Yes, refugees need help, but sometimes they also can lend a helping hand. A program that places skilled refugees in jobs in Canada helps resettle uprooted people and may help fill a labor shortage there.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Nagham Abu Issa is a Syrian refugee. She is also a valuable employee. She has a degree from Damascus University in English literature, and she has big dreams: to become a chief operating officer or even start her own company one day. She hopes to pursue that dream in Canada through Talent Beyond Boundaries (TBB), an American NGO that has started pilots in Canada and Australia to match a small number of refugees based in Lebanon and Jordan with employment opportunities abroad. Its goal: to forge new pathways for refugees to be recognized for what they can bring to a country, not for the state of the countries they were forced to leave. Heather Segal, a Toronto immigration lawyer, is working pro bono with TBB because she says too many skilled refugees stagnate while nations like Canada face labor shortages. “Why are we obviating a group of educated, skilled people because their country fell apart?” she asks. “There is a gap here that needs to be addressed…. We need creative solutions for the refugee system in the 21st century.”

In refugee flow, Canada finds a surprising solution to a labor shortage

Nagham Abu Issa was working as an executive assistant in a cement factory in Damascus when the civil war started in Syria. Her family fled to Lebanon. But with no job prospects there, her siblings left on the risky passage to Europe. Ms. Abu Issa, the eldest daughter, stayed behind with her mother.

She is a refugee. She is also a valuable employee. She has a degree from Damascus University in English literature and has studied human resources. As she worked her way up in her job, she had big dreams – to become a chief operating officer or even start her own company one day.

“My communication skills are my strongest asset, both internally and externally,” she says in an interview over Skype.

Now she hopes to take that savvy to Canada, not through resettlement but to fill the country’s labor gaps. She has interviewed with Talent Beyond Boundaries (TBB), an international NGO that has started pilots in Canada and Australia to match a small number of refugees based in Lebanon and Jordan with employment opportunities abroad.

The experiment so far is tiny, but it’s aiming high: to forge a new pathway for refugees to be recognized for what they can bring to a country, not for the state of the countries they were forced to leave. In so doing, TBB hopes to shift attitudes about refugees among Western nations and their immigration systems, some of which are under assault by the rise of populism and nativism.

Bruce Cohen, co-founder of TBB and former chief counsel and staff director for the US Senate Judiciary Committee, says that when they began at the height of the refugee crisis in Europe in 2014 and 2015, he was often told there were no talented refugees left. So his group created a searchable database for displaced jobseekers in Lebanon and Jordan that today holds more than 11,000 resumes. “Everyone from engineers to nurses, and also the skilled trades, carpenters, welders, plumbers, butchers, chefs, you name it, it probably is represented in the refugee community,” he says. “It is really getting rid of this image of refugees as unskilled, poor, pitiful.”

Building support systems

Their effort comes amid a much larger conversation about adapting the global refugee system, built after World War II, to the realities of long-term conflict. In 2017, 68.5 million people were forced to leave their homes, with 25.4 million becoming refugees outside their home countries. The vast majority are in countries that border conflict, such as Jordan, Lebanon, or Turkey. The global system currently envisions that refugees will voluntarily return when conflict ends, integrate where they first land, or be resettled elsewhere, an option limited to the most vulnerable.

By the end of the year, United Nations members are expected to endorse the Global Compact on Refugees, an international agreement that envisions more solidarity between countries hosting the majority of refugees on issues like resettlement and other pathways to third countries, which is where a program such as TBB would fit.

The group is not alone in grappling with how to put refugees to work. In the United States, the Tent Partnership for Refugees works with businesses to facilitate refugee hires, both in countries to which they first flee and where they are ultimately resettled.

Tent Partnership’s leaders argue that it is not just the right thing to do, it makes both strategic and business sense. A report released by Tent and the Fiscal Policy Institute in May, for example, showed higher retention rates and resilience among the refugee workforce in the US market. “Our key principle is that businesses can and should be doing more to support refugees,” says Gideon Maltz, the executive director of Tent Partnership for Refugees, who supports the TBB model as an additional option.

In Canada jobs are plentiful. The government recently announced it will take in 350,000 immigrants in 2021, or 40,000 more than it expects to admit this year. Canadian employers have also expressed interest in hiring refugees.

The Fairmont Chateau Whistler in British Columbia is just one example. The hotel offered jobs and housing to 12 refugees overseas who are now in the process of entering Canada as privately sponsored refugees. Four have already arrived. “The limitation is not on the jobs,” says Laurie Cooper, a private sponsor who helped facilitate the arrangement. She says she wishes the process were faster.

That is where TBB is attempting to make a difference, though their work is slow too, as they attempt to create a new pathway. In Canada, TBB has so far only secured 7 formal offers. The program works with federal and provincial governments on visas and connects employers to refugee talent. It helps businesses overcome legal barriers refugees face that traditional economic migrants would not, such as a lack of passports or access to education records.

Creative solutions for the refugee system

Susan Fratzke, policy analyst at the Migration Policy Institute, says TBB could scale up in Canada or Australia because of their robust economic migration systems. And other countries may look to economic migration for refugees as a model. “If you look at conversations about resettlement or asylum in Europe, there is a lot of concern about how people will be integrated, how they will find jobs,” Ms. Fratzke says. “If you are providing a pathway for people coming with an offer of work, that addresses some of those issues.”

Abu Issa says that one of her brothers, now a refugee in Sweden, applied for family reunification, but the claim was rejected. So she and her mother are still in Lebanon, more than five years after they first arrived, where work has been precarious and sexual harassment a constant concern. She has been in contact with international organizations that offer refugees the chance to study. “But I’m not a student. I’m a graduate,” she says. “My dream is to move with a job, to prove myself because of my work.”

Labor pathways for refugees have faced criticism by those who see it as a neoliberal overlay onto the refugee system. Mr. Cohen, the TBB co-founder, says it is meant to complement the current system, not take away from it. It is designed to reach skilled refugees who aren’t “vulnerable enough” to qualify for resettlement, he says. “[This program] is to say you can move based on your skills and abilities,” he says. “You move to a job that benefits from your skills. And that is a way back to self-reliance.”

Heather Segal, founder of Segal Immigration Law in Toronto, is working pro-bono with TBB because she says too many skilled refugees stagnate while nations like Canada face labor shortages. “Why are we obviating a group of educated, skilled people because their country fell apart?” she says. “There is a gap here that needs to be addressed…. We need creative solutions for the refugee system in the 21st century.”

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

A legal takedown of genocide

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

A United Nations-backed court established on Friday that the Khmer Rouge had indeed committed genocide in Cambodia during its reign. Two surviving leaders of the group were convicted of mass killings committed in the late 1970s. The verdict should ring loudly everywhere as a reminder to prevent more genocide. For many, that future is now. In Myanmar, the regime has continued a campaign of genocide against Rohingya Muslims. In Iraq and Syria, the Islamic State was defeated only last year after trying to eliminate the Yazidi minority. In China, members of the Uyghur community say Beijing is committing “cultural genocide,” detaining tens of thousands of the minority Muslims. Verdicts like those against the Khmer Rouge leaders are rare. Yet they help affirm progress in holding people accountable for violations of human rights. More than 80,000 Cambodians attended the trials of the Khmer Rouge leaders over four years, bearing witness to the application of a law that holds true far beyond their borders. This latest affirmation of that law can now more easily help protect other peoples facing genocide. It might also make leaders tempted to commit mass slaughter think twice.

A legal takedown of genocide

Despite a four-decade delay in justice, a United Nations-backed court established on Friday that the Khmer Rouge had indeed committed genocide in Cambodia during its reign. The two most senior and surviving leaders of the radical group, Nuon Chea and Khieu Samphan, were convicted of the most heinous of crimes – the killing of innocent minority groups en mass in the late 1970s.

The verdict may further assist Cambodians in coming to terms with their “killing field” past. It might also reduce impunity in a country still ruled by a former lower-level Khmer Rouge figure, Hun Sen. Yet it should also ring loudly everywhere as a reminder to prevent genocide in the future.

For many, that future is now. In Myanmar, the regime has continued a campaign of genocide against Rohingya Muslims who remain in the country, according to UN investigators. In Iraq and Syria, the Islamic State was defeated only last year after trying to eliminate the Yazidi minority. In China, some members of the Uyghur community say Beijing is committing “cultural genocide” by detaining tens of thousands of the minority Muslims in “reeducation” camps.

Genocide is difficult to prove in court. Prosecutors must prove intent. Verdicts like those against the Khmer Rouge leaders are rare. Yet they help affirm the progress over recent decades in holding people accountable for gross violations of human rights.

“Overall there is less violence and fewer human rights violations in the world than there were in the past,” writes human-rights scholar Kathryn Sikkink of Harvard University in her latest book, “Evidence for Hope: Making Human Rights Work in the 21st Century,” based on extensive review of historical data.

Most countries now accept treaties on human rights even if they do not always enforce them. And since the 1994 Rwandan genocide, the UN has set up more international courts like the one for Cambodia to try perpetrators under the idea that human rights are universal. The result, says Ms. Sikkink, is a steady decline in genocide.

More than 80,000 Cambodians attended the long trials of the Khmer Rouge leaders over four years. The courtroom crowd was witness to the application of a law that holds true far beyond their borders. This latest affirmation of that law can now more easily help protect other peoples facing genocide or similar crimes. It might also make leaders tempted to commit mass slaughter think twice.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Reaching

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 1 Min. )

-

By Paula Jackson

At a time when questions of identity are front and center, today’s column is a poem that offers a deeper, spiritual sense of what we all are as God’s eternally loved children.

Reaching

Reach out to God

Right where you are

And as you are

He is right there

With you

Loving you completely,

Impartially,

Seeing you as His perfect,

Precious child.

Reach within

For the higher, truer thoughts

Of your identity,

They lift you above

The clamor of matter’s lies

And help you realize

Your spiritual being.

Reaching for the Truth,

The Christ-power, Leads you to the “Horeb height,”*

The consciousness of

Spirit’s supremacy,

Of God as the only Life

And you as the man

Of God’s creating.

* Mary Baker Eddy, “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” p. 241

Originally published in the March 2016 issue of The Christian Science Journal.

A message of love

A festival of refreshment

A look ahead

Have a good weekend, and come back Monday. On the Move, our series about migration, continues from Niger. We’ll look at the progress and pitfalls of the European Union’s effort to tempt people away from the migrant trade through operations at its source.

Also, if I say “welcome to the bundle,” a few thousand of you will know what I mean. Now that you’re reading the digital Daily to supplement your print Weekly, consider a neat shortcut: Read here about how to quickly add a home-screen bookmark to your iPhone or Android phone. Puts you a thumb tap away from the current Daily (even before the email notification goes out).