- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- Hope in a harrowing time: California fire survivors grapple with what’s next

- After Florida recount, ballot signature issue remains a concern

- As US courts recede, Americans busy defining the right to vote

- How Texas wants to save football from concussions

- Move over, phones! Make room for books that fit in a back pocket.

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Weighing consumerism’s long throw

Happy #BuyNothingDay, or #OptOutside Day!

Or, yes – as your inbox has relentlessly suggested for weeks – Black Friday.

That retailpalooza would be a boring recurrence by now except that it keeps mutating. China’s version, now called Double 11 for its Nov. 11 date, pulled in $30 billion in sales this year.

In the United States, Instagram “influencers” again marketed lifestyles that demand new goods. Walmart used virtual reality to train greeters to manage crowds. A cottage industry in “line sitting” has shopping-line placeholders making up to $35 an hour.

At a time when debates run to extremes, you might expect hyperconsumers and voluntary simplicity types to be engaged in open war. But there’s lots of crossover behavior in the middle. You can lament the loss of a whale this week off Indonesia to 13 lbs. of ingested plastic and still rely on the material, even if reluctantly, for some near-term needs.

Collectively, though, we may be looking away less and thinking more.

Ask a college kid about plastiglomerate, the rocklike substance that will be a legacy of the Anthropocene age. Share a nice read about a family-run emporium in Pennsylvania that uses hot chocolate, not hot deals, to draw no-tech browsers seeking throwback fashions. And don’t let Black Friday “news” black out news about consequences, like today’s government report about human impact on climate change. Thought shifts? Those seem worth shopping for.

Now to our five stories for your Friday. We look at pushes for needed progress in two states’ voting processes, at another state’s effort to preserve a signature sport, and at a tiny innovation in reading.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Hope in a harrowing time: California fire survivors grapple with what’s next

This report looks at the persistent sense of agency among those affected by US West Coast wildfires of record-setting ferocity – and at many residents’ refusal to be defined by tragedy.

As they wait in evacuation centers and other temporary shelters, residents of Paradise, Calif., the town of 27,000 that was mostly destroyed by the Camp fire, are now facing hard choices about their future. Is it worth it to return home and rebuild, not knowing when jobs will return, schools will reopen, and basic services will resume? Or are the fires a sign to pull up stakes and start fresh? The dilemma pits the head against the heart as residents weigh the prospect of future wildfires with the emotional pull of home. “I want to go back,” says one third-generation resident of a settlement that borders Paradise. “This is home. If it burns 10 more times, we’ll rebuild 10 more times.” Others see the blaze as the opportunity for a new beginning. “It’s a clean slate is the way I’m trying to look at it,” says a Marine veteran who moved to Paradise two years ago. “I’ve wanted to live out East for a long time. This might be my chance to do it.”

Hope in a harrowing time: California fire survivors grapple with what’s next

Carmen Chalfant moved to Paradise in 1999. But it might be more fitting to say Paradise moved her.

The Northern California town of 27,000, nestled among towering pines and shimmering lakes in the foothills of the Sierra Nevada, charmed her from the start. She knew after her first visit she would retire there. She loved the unrushed pace as much as the pastoral setting, and she never tired of telling friends, “I live in Paradise!”

Two weeks ago, when the deadliest and most destructive wildfire in California’s history ripped through the city, Ms. Chalfant lost her personal Eden. The flames incinerated her house, her car, and her sense of place.

“Everything — it’s gone,” she says, standing in the gym of the East Ave Church in Chico, 15 miles west of Paradise, which has served as an evacuation center for residents forced to flee their homes. As Chalfant tries to regain control of her life, one aspect of her future has become clear in recent days as rains wash away the fire’s acrid haze. “I’m done with Paradise,” she says, shaking her head. “I won’t go through something like this again.”

Lorraine Sampson arrived at the church with her husband and their three young children on the same apocalyptic day as Chalfant. The family, along with Ms. Sampson’s mother, another relative, and two dogs, jammed into a car and drove toward Chico as smoke blackened the morning sky and ash fell like snow.

A third-generation resident of Magalia, an unincorporated town bordering Paradise, Ms. Sampson escaped with little besides a handful of family photos and the urn that holds the ashes of her infant daughter who died last year. The loss of her house has deepened her resolve to remain in the area.

“I want to go back,” she says, one arm around her eldest daughter, Hailey, who hugged her waist. “This is home. If it burns 10 more times, we’ll rebuild 10 more times.”

The differing perspectives on whether to leave or stay illuminates the thorny choice confronting the estimated 52,000 residents displaced by the so-called Camp Fire that by Friday had been 95 percent contained. Beyond the blaze’s staggering toll to date — 84 people dead and 560 missing, almost 14,000 homes razed, some 153,000 acres scorched — they must answer the question of where to begin again.

The dilemma pits the head against the heart as residents weigh the prospect of future wildfires and the emotional pull of home. The breadth of devastation complicates their decision. The fire has leveled more than 500 commercial buildings and 4,200 other structures, and nobody knows when businesses will return, schools will reopen, or basic services will resume. Given that uncertainty, they wonder if the area will recapture its communal spirit, the essence of the place that made it their own.

“It’s going to take a long, long time for Paradise to recover, if it ever will,” David Bravot says. A retired musician staying at the church, he had learned a day earlier that the fire spared his house, a turn of fortune he describes as “a gentle miracle.”

“What’s left? How long will it take for companies to rebuild? Will people get their jobs back? Who’s going to live there? There’s no way to have any idea right now.”

Pondering what comes next

Wildfires gutted 200 homes in and around Paradise in 2008 and forced the evacuation of thousands of residents from Butte County before firefighting crews could subdue the flames. The Camp Fire showed less restraint.

The blaze roared to life Nov. 8 — the cause is under investigation — and devoured tinder-dry vegetation across a landscape choked by drought as winds gusted above 50 mph. By the time Paradise officials ordered a full evacuation shortly after 9 a.m., the fire had reached the city.

Chalfant found herself trapped in the confusion of a mass exodus as vehicles clogged the four routes out of town and smoke smothered the sun. She abandoned her car after hearing someone yell that people should board an evacuation bus.

But after traveling a mile, the bus stopped as flames crowded the road, and Chalfant and the others stepped out. As she struggled to walk back to her car — at one point falling down and injuring her knee — a couple offered her a ride. They drove out of the burning city in the sudden darkness amid the explosions of propane tanks, fuel pumps, and parked cars.

The wildfires a decade ago worried Chalfant, a retired nurse, yet she had faith that city officials would follow safety suggestions laid out in a grand jury report on the blazes that called for improving the area’s warning systems and evacuation plans. She thinks now that her trust was misplaced, and she intends to move to Port Orchard, Wash., where her two children live with their families. The decision has restored a measure of her self-reliance.

“It’s not like we didn’t know what could happen,” says Chalfant, who could grab only her laptop, cell phone, and medications before fleeing her house. “I’m not going to wait to see if it’s better next time; I almost died this time.”

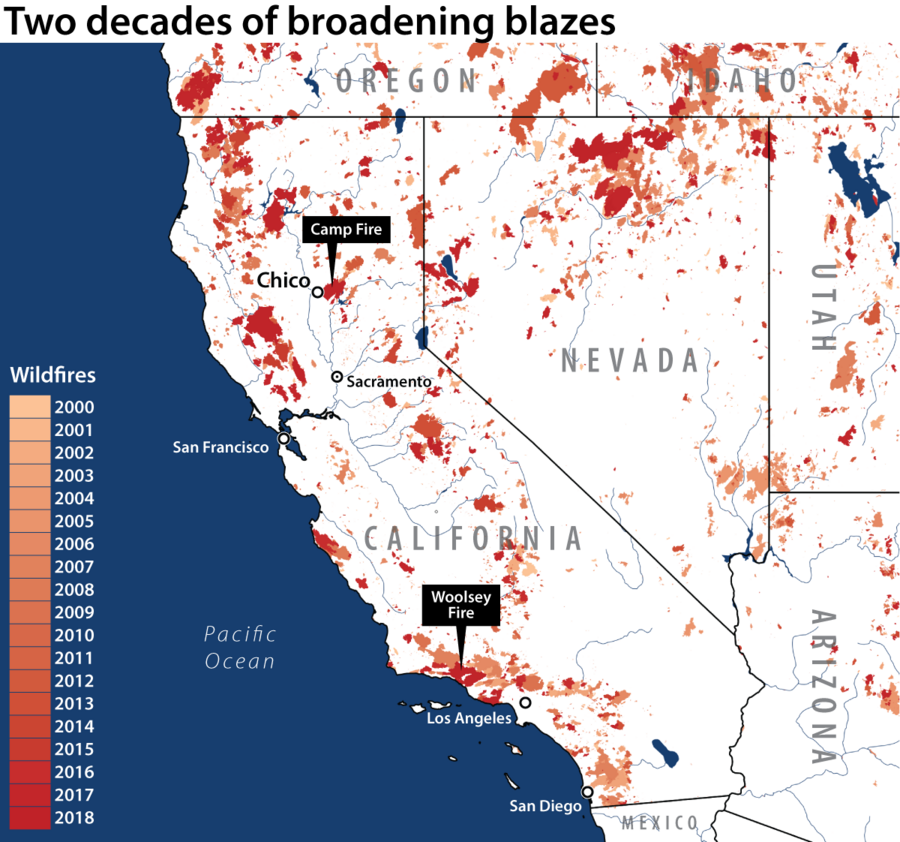

The Camp Fire ignited on the same day as a sprawling blaze in Southern California that killed three people, and both began less than two months after crews extinguished the largest wildfire in California history. The Mendocino Complex Fire charred nearly 460,000 acres, and so far in 2018, more than 1.6 million acres have burned statewide, the highest total in a decade.

The destruction follows a punishing year of wildfires that caused $12 billion in damage as California, besieged by higher temperatures, lack of rain, and population growth, attempts to adapt to the reality of a year-round fire season.

More than 250 people affected by the Camp Fire wound up at East Ave Church, one of several shelters set up in the area to aid evacuees. They sleep on cots and air mattresses, wear donated clothes and shoes, and ponder whether to resurrect their former lives or start anew elsewhere.

Aaron Anderson, a Marine veteran who moved to Paradise two years ago, saw the flames approaching his cottage and ran to check on an elderly woman who lived next door. The pair escaped in Mr. Anderson’s car, and while the fire claimed his home, he feels a sense of freedom about the future.

“It’s a clean slate, is the way I’m trying to look at it,” says Mr. Anderson, who left behind his three cats in the chaos. “I’ve wanted to live out East for a long time. This might be my chance to do it.”

‘A message from God’

A quarter of Paradise’s residents are 65 and older, and dozens showed up at the church within a day of the fire. The hardship of the past two weeks foretells the adversity that awaits them when they emerge from the limbo into which the blaze has cast them.

“I am still numb,” says Carla Brawt, whose apartment building burned down. “I live in Paradise, but there is no more Paradise. So I don’t know what I’ll do.”

A few miles from the church, the Federal Emergency Management Agency operates an assistance center in a vacant Sears store at the Chico Mall. The line on this weekday afternoon curls out the door and down the sidewalk as hundreds of people wait to apply for housing aid.

Betty Garver and her husband lived in Paradise for 30 years before the Camp Fire reduced their home to ash and rubble. The retired couple will need time to decide whether to return for a fourth decade.

“We don’t know if we’ll rebuild,” says Ms. Garver, leaning on a walker as she leaves the center. “There’s nothing there now except vacant lots, mostly. So we don’t know what the town will look like — or when it will look like a town again.”

Federal and state officials have toured devastated areas of Butte County, including President Trump, Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke, and California Gov. Jerry Brown. Brock Long, the administrator of FEMA, told reporters last week that the region’s recovery would take “several years.”

“You’re not going to be able to rebuild Paradise the way it was,” he added.

The fire has brought into focus what Governor Brown refers to as “the new abnormal” for California — larger wildfires fueled, in part, by climate change. Despite the evident risks, Sampson, the mother of three, views the calamity as a test of character and a chance for residents to prove their resiliency.

“Paradise was close-knit before the fire,” she says. “This will make us 10 times stronger.” She sits in the room that the church has set aside for families, and nearby, her two youngest children watch the animated movie “Up” on a flat-screen TV. “If we give up and don’t rebuild what we had, what does that teach our children? I want to teach my kids to fight.”

As Sampson thinks about the next generation, her mother, Tamantha Delgado, believes the family owes previous generations the honor of returning to Magalia.

“We got 30 family members who are buried in the cemetery there, and we’re not leaving them behind,” Ms. Delgado says. “This is a message from God to do things the right way from now on. It’s a new beginning.”

What remains unknown is when that new beginning will arrive.

US Geological Survey

After Florida recount, ballot signature issue remains a concern

Here’s a look at a 2018 midterms issue that’s clearly also a 2020 look-ahead. The nation’s largest swing state is looking at the constitutionality of one its ballot validation practices.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

Two days after the polls closed in Florida, lawyers for incumbent Sen. Bill Nelson (D) and the Florida Democratic Party filed a lawsuit to try to get the state to count as valid some 5,600 votes that had been declared invalid because of a signature mismatch. And while Senator Nelson ultimately lost to Republican Gov. Rick Scott by more than 10,000 votes, the lawsuit over signature mismatches on Florida ballots is continuing. The litigation is seen by many analysts as an attempt to shape the electoral landscape in the nation’s most important swing state in advance of the 2020 election. At issue is whether Florida’s system of disqualifying ballot signatures varies so greatly from one county to another that it violates the Constitution’s requirement of equal protection and equal treatment. In addition, the court is poised to examine whether Florida allows voters with disputed signatures enough time to address the discrepancy. “Some counties were doing more outreach to voters and others weren’t,” says Amber McReynolds, executive director of the National Vote at Home Institute. “That is the kind of inconsistency you don’t want to see in a statewide race.”

After Florida recount, ballot signature issue remains a concern

When Grace Hidalgo went to the polls in Florida’s Broward County on Election Day, everything seemed routine.

“I was basically in and out,” she says. “I was thinking my vote went through.”

She was wrong. At the very end of the voting process, instead of feeding her ballot into an electronic tabulator at her precinct, an election official placed her ballot in an envelope and asked her to sign her name across the sealed flap.

Ms. Hidalgo didn’t know it at the time, but that little bit of hasty penmanship would end up disqualifying her vote.

“If I had known, I would have made sure it looked like my driver’s license signature,” she says. “I’m shocked that it is all because of a signature that my vote didn’t count.”

Hidalgo was one of 5,686 Florida voters who cast ballots in the state’s hotly-contested 2018 midterm elections only to have their votes declared invalid because of a signature mismatch.

Although it was only a tiny fraction of the 8.2 million votes cast in Florida on Nov. 6, lawyers for incumbent Sen. Bill Nelson (D) and the Florida Democratic Party filed a lawsuit asking a federal judge in Tallahassee to order the state to count each of the 5,686 votes as valid ballots.

The lawsuit came two days after the polls closed, but at a time when Senator Nelson appeared to be closing a razor-thin gap with his Republican challenger, Gov. Rick Scott. The hope was that if the judge declared Florida’s signature verification system unconstitutional, Nelson would reap the lion’s share of those 5,600 invalidated and uncounted votes.

It didn’t happen. Instead, US District Judge Mark Walker ordered state election officials to extend the deadline to allow voters with a signature mismatch more time to “cure” their disputed ballots.

In the end, Nelson did not overtake Scott, who won the US Senate seat by more than 10,000 votes. Nonetheless, the lawsuit over signature mismatches on Florida ballots is continuing.

The litigation is seen by many analysts as an attempt to shape the electoral landscape in the most important swing state in the country in advance of the 2020 election.

At issue in the court battle is whether Florida’s system of disqualifying ballot signatures varies so greatly from one county to another that it violates the Constitution’s requirement of equal protection and equal treatment. In addition, the court is poised to examine whether Florida allows voters with disputed signatures enough time to address the discrepancy so their votes will count.

A subjective process

Deciding whether a signature is a close enough match to an on-file voter registration signature can involve a large number of subjective variables that might differ significantly from county to county.

It is a problem that starts with the voters themselves and penmanship.

“We know that people scratch out a signature at the grocery store and that may be very different from how they sign an official document, or how they signed their driver’s license, or how they sign their mail ballot,” says Amber McReynolds, executive director of the National Vote at Home Institute.

It’s not just sloppy handwriting. Some voters have had their signatures rejected because they were too careful, too precise in how they signed their vote-by-mail ballots, she says.

All 50 states allow some form of absentee voting. Twenty states require an excuse to obtain an absentee ballot, while 27 states allow any qualified voter to cast an absentee ballot upon request, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures.

Three states – Oregon, Washington, and Colorado – conduct their elections through mail-in ballots. Several other states are expanding their use of mail-in voting, which means that more officials across the country are grappling with the signature-match question.

Here in Broward County, when election officials can’t match a particular ballot signature, the disputed scrawl is sent to the county’s three-member canvassing board to make a final determination.

Members of the board receive no special training and are not permitted to consult with a handwriting expert.

“The law says that this is a determination that can be made by a layperson,” says County Judge Betsy Benson, chair of the Broward County Canvassing Board. “You take your time and you look as closely as you can, and if the majority of the board believes it is a valid signature, it is a valid signature,” she says.

More than 714,000 votes were cast in Broward County during the 2018 midterm elections. Of those, roughly 189,000 were vote-by-mail ballots.

There are three categories of ballots in Florida that involve signature-match issues: so-called absentee ballots; ballots delivered from voters overseas; and provisional ballots.

In the 2016 presidential election, Broward County received 205,174 votes requiring a potential signature match. Of those, 128 ballots were deemed invalid because of a perceived signature mismatch. That is a .06 percent rejection rate.

Ms. McReynolds served as director of elections in Denver prior to joining the Vote at Home Institute. She says based on her experience in Colorado, a rejection rate lower than one percent is viewed as acceptable.

In 2016, the statewide signature rejection rate in Florida was .23 percent – less than one-quarter of one percent, according to a Monitor analysis of data compiled by the federal Election Assistance Commission.

Susan Pynchon is chair of the Florida Fair Elections Coalition, based in Volusia County. She says it is essential that members of a county canvassing board examining signature mismatches embrace a permissive posture in which they err on the side of the voter.

“I have a wonderful video of our canvassing board looking at signatures. The care they put into it is just extraordinary,” she says. “They look for every reason to accept that vote. You can hear them say, ‘See that curlicue on the J,’ ” she says.

‘A lot of inconsistency’

Ms. Pynchon says the problem in Florida is that the state’s deadlines to certify election results fall too quickly after the election. She says that many of the signature mismatches might be cleared up by the voters themselves if they were given more time after the election to do so.

In his decision extending the deadline for certain voters to cure their mismatched signatures, Judge Walker suggested that Florida might consider adopting a provision embraced by Oregon, which allows voters two weeks after every election to cure any signature discrepancy. McReynolds says that in Colorado, voters are given up to eight days after the election to cure a signature discrepancy. In California, the period is 10 days.

“A good process is the key to this,” McReynolds says.

Ballot scrutiny is important. Discovering a mismatched signature can lead to a fraud investigation if a voter reports back that he or she did not cast a ballot. That information can be turned over to authorities for investigation.

But the process also has to be fair to the voter and reasonably consistent across the state, McReynolds adds.

“There is a lot of inconsistency county by county in Florida in terms of how that is administered,” she says. “Some counties were doing more outreach to voters and others weren’t. That is the kind of inconsistency you don’t want to see in a statewide race.”

In Colorado, officials in larger counties use a software program that helps match the ballot signature to a database of signatures from each voter. The remaining unresolved signatures are turned over to bipartisan teams that compare the ballot signature to other signatures on file with the state. “We might have 20 to 30 different signatures on file for a voter over time,” McReynolds says.

The other key to an effective signature match program is to provide immediate notification to a voter with a signature mismatch and a convenient method for that voter to cure the ballot.

In Colorado, voters are given a choice to return an affidavit with a copy of their ID via text, email, fax, or they can drop it off in person at any vote center.

Voter responsibility

Voters also share some responsibility, experts say.

“People should check their signature. If they really want to vote by mail, they need to have a consistent signature and they need to know what their signature on file at the supervisor of elections office looks like,” Pynchon says.

Signatures can change over time. And many younger voters are comfortable using a keyboard but lack a consistent handwriting style. “One of my friend’s sons is like that,” she says. “He can never vote by mail because his signature never looks the same.”

Ms. Hidalgo agrees that penmanship and an evolving signature style were a big part of her Election Day problem.

She believes that election officials converted her ballot into a provisional ballot because of a communications foul up in her precinct at the time she arrived to vote. Election officials were unable to immediately check to verify she was a registered voter so they made her ballot into a provisional ballot.

Despite this action, Hidalgo says she was never notified that there was a problem with her signature, and was never told how she could correct the signature mismatch. By the time she learned of the signature problem, the time to cure her ballot had passed. She was effectively disenfranchised.

As US courts recede, Americans busy defining the right to vote

Here’s another vote assessment saga. Cries of disenfranchisement rang out in Georgia, where more than half a million voters had been purged from rolls. But for many voters, these challenges have hardened rather than diminished their resolve.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 8 Min. )

Nola Cunningham remembers participating in the civil rights movement of the 1960s as racial tensions flared in Georgia. In the decades since, one thing remains a reminder of her civic value and her sacrifice: her vote. Last month, Ms. Cunningham’s hard-fought dignity was unexpectedly confronted when she and eight other African-American seniors were ordered by county officials to get off a bus headed to the polls. That incident appears to have been a misunderstanding. But it has highlighted voter rights issues this election season, with reports of voter names stricken from the rolls, shortages of provisional ballots, and charges of mismanagement of absentee ballots. For much of the past 50 years, changes to voting procedures in Georgia were subject to approval by the Department of Justice – a key provision of the 1965 Voting Rights Act. But a 2013 Supreme Court decision changed all that, shifting the responsibility from the judicial system to local governments, election officials, and voters themselves.

As US courts recede, Americans busy defining the right to vote

Surrounded by a partial crew of her 18 grandchildren and great-grandchildren, Nola Cunningham sits in the recliner at the hearth of her humble house on Yazoo Street. The presence of her family only heightens the dignity of the septuagenarian’s authority.

Ms. Cunningham reminisces about picking butter beans as a teenager, partly for money but also to get away “from really strict parents.” Now this is her place, where country clutter mixes with memorabilia, a broken lawnmower, and a black-and-white portrait of a young Cunningham at graduation.

Seared into her memory are the 1960s protests she participated in as racial tensions flared and Georgia became the cradle of the civil rights movement. In the decades since then, she has held one thing as a constant reminder of her civic value and her sacrifice: her vote.

Last month, Cunningham’s hard-fought dignity was unexpectedly confronted when she and eight other African-American seniors – all potential voters – were ordered by county officials to get off a bus headed to the first day of early voting in Georgia, which stood on the precipice of electing its first black governor.

“Everybody was just excited about riding that big black bus,” she says.

One moment they were dancing in the parking lot to James Brown’s “Say It Loud - I’m Black And I’m Proud,” “but then someone called the commissioner” and the get-out-the-vote party was over. The ladies filed off the bus. “It was a sense of disappointment,” Cunningham says.

County officials said they believed it was a partisan event. But the group that hired the bus, Black Voters Matter, is registered with the state as a non-partisan organization. Few felt disenfranchised. Cunningham did eventually get to the polls to cast her vote, as did, she says, the other ladies on the bus. Yet, she can’t quite shake the memory of that joyous moment, a celebration of her and her companions’ rights and civic duty, getting cut short.

The incident made national news, adding a murky layer to an emerging portrait of Georgia – one voting rights experts say is not wholly inaccurate – as a state bent on disenfranchising voters of color. That image has taken on a sharper hue with reports of voters arriving at the polls to find that their names had been stricken from the rolls, shortages of provisional ballots, and charges of mismanagement of absentee ballots.

“The sorts of practices that we saw in Georgia conjure up the ghost of Jim Crow,” says Daniel Tokaji, professor of law at The Ohio State University and author of “Election Law in a Nutshell.” “And I don’t mean just for political junkies, but for ordinary people. They look at what happened in Georgia this past election and it is alarmingly familiar.”

A legacy unfolds

Voting rights have stood center stage this past election season, especially in the South, where advocates say some politicians have taken advantage of a loosening of legal restrictions meant to ensure equitable representation at the polls.

To be sure, the 15th, 19th, 24th and 26th Amendments are all in effect to protect every American’s right to vote.

But in 2013, in a case called Shelby County v. Holder, the US Supreme Court took a decisive new stance on voting rights, steering away from former Justice Thurgood Marshall’s idea of the court as an ensurer of racial equity under the law. The high court’s decision repealed a Voting Rights Act mandate that required jurisdictions where voter suppression has occurred in the past to pre-clear voting changes with the Department of Justice.

Within days, states, primarily led by Republicans, began passing new restrictions that would have previously fallen under Supreme Court oversight. In Georgia, Shelby appears to have prompted an escalation in the removal of voter registrations. According to the Brennan Center For Justice, the state purged 1.5 million voters between the 2012 and 2016 elections, double the number removed between 2008 and 2012. This past July, more than half a million voters were removed from Georgia’s rolls. In June, the Supreme Court upheld a similar purge in Ohio.

Since 2012, Georgia has closed 214 precincts, leaving one-third of counties in the state with fewer precincts than they had before the Shelby decision. The closures have been attributed to cost-saving consolidation and to a reduced need for polling stations on Election Day due to an increase in early voting. Many of those precincts were in minority-majority neighborhoods.

The issue came to a head when the architect of those changes, then-Secretary of State Brian Kemp, a “Trump conservative,” took on former House minority leader Stacey Abrams, who painted herself as the champion of the “unwanted voter,” in a neck-and-neck race for governor.

Critics say thousands were disenfranchised – perhaps enough to have swayed an election where 20,000 votes spanned the difference between a done deal and a runoff. Some 340,000 Georgians may have showed up to vote and found their names expunged, according to investigative journalist Greg Palast, who sifted through the purge lists in coordination with civil rights groups like the Southern Christian Leadership Conference.

On Friday night, Ms. Abrams acknowledged that she didn’t have the votes. Her decision to not file a lawsuit suggested that her impression of unfairness, however, likely would not hold up in court.

The US is now at a moment of gauging and calibrating where to shift the responsibility for ensuring fair elections in the wake of Shelby, voting rights experts say. Judging by Cunningham, the right itself may be as strong as ever, if not by law, by the character of its participants.

“They tell me to vote for the shoe, I’m going to vote for the boot,” chuckles Cunningham. “Nobody tells me what to do, or how to vote.”

The onus shifts

Last Friday, in a brick edifice the size and shape of a municipal pump station, Susan Gray and Natasha Mack were wiping their collective brows.

Ms. Gray, an elections superintendent, and Ms. Mack, her righthand woman, saw more than a hundred voters per day during early voting. For a county so small, it was an avalanche. “It was bigger than [Obama] in 2008 and [Trump] in 2016,” exclaims Mack.

Gray is painfully aware that Republicans believe Democrats are ready and willing to commit large-scale voter fraud. She also knows that Democrats believe Republicans are engaging in wholesale voter suppression.

“It can be hard because people tend to view the election process through who they want to get elected that particular year,” says Gray.

And she is aware that things have changed. She received two letters from then-Secretary Kemp notifying counties that the rules have changed under Shelby. But in the end, only a few votes were disputed, recounted, and added to the total, on Friday. In short, there was no evidence of disenfranchisement in Jefferson County. Quite the opposite, judging by the turnout.

But flanked by an old stand-up voting machine, Gray – who cuts the profile of a kindly but harried librarian – stands at the intersection of two monumental shifts.

Recent Supreme Court decisions – and the increasingly conservative makeup of the court – have moved the US further away from Justice Marshall’s idea that “the Negro” deserved “greater protection ... to remedy the effects of past discrimination.”

With that change, the responsibility for preserving the integrity of the electoral system has shifted from the courts to local governments, election officials like Gray, and voters themselves.

The decision to scrap the 1965 pre-clearance formula appears to have in some jurisdictions – Georgia and North Carolina particularly – unleashed impulses to game the vote through massive voter purges and other actions under the guise of protecting against voter fraud, says Gilda Daniels who served as deputy chief in the DOJ’s Civil Rights Division under Presidents Bill Clinton and George W. Bush.

Before 2013, “all the decisions in regards to polling place closures, how to count absentee ballots, how to count provisional ballots, all of those would have had to be cleared by the Department of Justice, by the attorney general of the United States,” says Professor Daniels, who now teaches law at The University of Baltimore.

“Now, secretaries of State offices like Brian Kemp’s can make those decisions without ever having to think twice about having to adversely impact a particular group of voters or not,” she says. “Today there is a different illness, but it has the same impact: disenfranchisement of people of color on a wide scale.”

For Daniels – and many Georgia voters – Kemp’s decision to retain his position as secretary of State and chief election overseer while running for office was emblematic of how Shelby has emboldened some Southern politicians.

Kemp’s machinations, however, do suggest that courts still play a role in regulating partisan and racial impulses. US District Court judges have ruled against certain restrictions taken in the name of election security that would disproportionately affect voters of color.

Just days before the Nov. 6 election, US District Judge Eleanor Ross ruled against Georgia’s “exact match” law, which flagged voter registrations where the spelling of residents’ names varied between official documents. Whatever the intent of the law, the effect was that people with Africanized names were more likely to be purged.

“Maybe it is not driven by racial hatred – although we are seeing resurgence of old-fashioned racial hatred – but let’s not forget that vote suppression has always been about self-interest as much as about racial animus – the self-interest of those in power to make it more difficult for other people to vote,” says Professor Tokaji, who has argued several key voting rights cases in the last 15 years.

An electorate electrified

On the other hand, Election 2018 has reminded many Georgians that voting will perhaps forever be a hard-fought right.

All those hours Georgia voters spent waiting in the rain and dealing with poorly prepared precincts amounted to the price of the franchise, voting rights experts suggest.

“At best they are trying to game the election system for their advantage; at worst, they are trying to prevent people from voting,” says Andra Gillespie, a political scientist at Emory University, in Atlanta. Either way, “that’s wrong. That’s a problem. You can’t claim that race doesn’t have anything to do with this when party and race are so heavily correlated.”

Indeed, Michael McDonald, a political scientist at the University of Florida, has found correlations between voting restrictions and decline in participation by some voters.

At the same time, the will of the people to ensure their voices can be heard has echoed throughout the country.

Voters in Michigan fired politicians from what had become a partisan redistricting process, putting a citizens’ council in place instead to draw fair and competitive districts.

Sixty-four percent of Floridians agreed to automatically reinstate the franchise to released felons. In a state that remains evenly split between Democrats and Republicans, that result means the issue crossed partisan lines.

And more locally, after an uproar, Randolph County, Ga., in August scrapped a consultant’s plan to close seven of the county’s nine precincts just ahead of an election already shadowed by suppression charges.

In that way, says Tokaji, the enduring lesson from Georgia “is likely to be that vote suppression is a double-edged sword. It might help you win a particular election. But the backlash is likely to be much stronger than the number of voters that you’re likely to actually keep from voting in the first place.”

In that way, the post-Shelby era may be defined by an electorate electrified.

“Yes, it is a fight to vote,” says Daniels, the former voting rights deputy chief. “You have to continue to fight. And in some ways that is good. It demonstrates that participation goes beyond Election Day.”

How Texas wants to save football from concussions

Safety concerns have made high school football controversial. The view from Texas shows those challenges but also how the drive to make football safer has focused on saving the good the sport does.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 8 Min. )

To be honest, Texas doesn’t need to do too much about high school football. Participation rates across the United States might be declining, but not here, where they’ve gone up slightly. The state’s legendary Friday night lights are shining as brightly as ever. Yet things are changing. From peewee to professional, football is under enormous pressure to protect its athletes from head injuries. They could be an existential threat to the game. Not only do Texas high school coaches know this, but they also care about their kids. The result is a fundamental change in safety culture across the state. Next season, for example, Texas will become the second state to mandate concussion reporting. Challenges remain, both with foot-dragging coaches and the sport’s violent nature. But if any place is going to save football, it’s Texas. “I’ve never been into the toughness of the sport; that’s never been my motivation…. I don’t have any qualms about the [safety] changes,” says one coach. “We can put our head in the sand and say we don’t like it, but the truth is it’s here.”

How Texas wants to save football from concussions

It is 6:30 a.m. on a Monday, and the fields around this small town stir with cows, goats, and of course, the high school football team.

Nestled in the heart of Texas Hill Country, Fredericksburg could be any town in the state on this morning in early November. It’s the last week of the high school football regular season, and Lance Moffett, the Fredericksburg High School head football coach, is preparing for the make-or-break game to get his team into the playoffs.

In some ways, Mr. Moffett experienced so many mornings like this one as a high-schooler outside Dallas in the 1980s. Yet the practices he runs are far removed from his high school days. Today, he is trying to save his state’s most beloved sport.

Like in other high schools around the country at the time, Moffett was coached to lead with “the screws” of his helmet – hit head-first and hard, in other words – when tackling. He had five concussions that he’s certain about – the ones a doctor diagnosed – but it could be more.

Back then, when he got his “bell rung” he would just sit out a few plays. Now, with research linking concussions to severe brain damage and death, he is doing exactly the opposite.

From peewee to professional, football is under enormous pressure to protect its athletes from concussions and other head injuries. In some quarters, head injuries are seen as an existential threat to the game’s future. Participation in high school football has declined nationally.

But Texas is an interesting case. High school football is a core part of the state’s identity, and so perhaps more insulated from the push for change. Indeed, participation in high school football here has increased slightly in recent years. Yet having football at the heart of Texas culture adds its own pressure. Kids of all shapes and sizes will show up to play, but if they aren't protected that culture could erode.

So change is taking hold. When Moffett played in high school “it was virtuous to knock the crap out of people,” primarily by leading with your head, he says. Today, there is an increasing awareness of – and commitment to – keeping football thriving in Texas by keeping the head out of the game as much as possible.

“Can [high school football] continue to be the state jewel it has been for a very long time? Yes, I think it can be,” says Jamey Harrison, deputy director of the University Interscholastic League (UIL), the administrative body for high school sports in the state. “But what it will continue to require is to push and continuously make it as safe as we can.”

“We’re much more professional now than we certainly were 30 years ago,” says Moffett.

Practice makes improvement

Sitting in his office after practice, Moffett squirms slightly when discussing how things have changed. He doesn’t want people thinking his coaches were callous.

“The reason people like me maybe get defensive about it is because we’ve always had child safety as our No. 1 deal,” he says.

His coaches “thought it was safe [to tackle] as long as you had your head up and your spine aligned. They thought it was safe to lead with your face,” he adds. “The definition of safety has certainly changed in my career. I don’t think the concern for safety has changed.”

When Moffett played, full-contact scrimmages could last entire practices. Today, teams are restricted to eight hours of practice a week, of which a maximum of 90 minutes can be full-contact. Even at full-contact, coaches are quick to stop play right after hits, and players are told not to run through tackles or drag each other to the ground. (After head-to-head contact, the most frequent cause of concussion in football is head-to-ground.)

Fredericksburg’s coaches all got certified in concussion management several years ago, and over the summer most of them got certified in “rugby-style” safe and effective tackling, which involves using shoulders instead of heads.

Technology has also been a big game changer. Helmets are designed to distribute energy from impacts more evenly. But there are only so many new gizmos Moffett can get, and it can feel as if new technology is arriving every week.

“I’ve got to work within a budget. I’ve got to decide how much money I can spend per kid, and I’ve got to spend it on all my kids,” Moffett says. “It’s kind of the wild, wild West right now.”

If players are diagnosed with a concussion, they instantly enter a protocol written into state law in 2011. They are out for a minimum of 12 days – they can’t practice for seven days, or longer if they still have symptoms, and then have to wait five more days before they can play again.

Next season the UIL will be introducing another new policy: The state’s largest schools will report every concussion incident. The information will be relayed to researchers at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center for study. It will make Texas the second state, after Michigan, to mandate concussion reporting.

A decision for parents

Of course, rules only work if they are followed.

Donna and Troy Yarbrough of Santa Fe, Texas, say that two years ago their son was scrimmaging twice a day against the varsity defensive line, even though he was on the junior varsity. When he complained of a headache and nausea, a trainer told him to sit out the next practice. He did, but the symptoms continued. A doctor diagnosed him with a concussion, adding that he’d had at least one undiagnosed concussion, perhaps more.

Today, he still gets migraines, and he hasn’t played football since. His parents have filed a civil rights lawsuit against the school district, joining a rising number of similar suits being filed around the country.

The Santa Fe school district didn’t respond to a request for comment. Sherry Chandler, a lawyer representing the Yarbroughs, says the suit is about emphasizing safety over a “win at all costs” culture.

“We’re not trying to stop all football in this country,” she adds. “It just needs to be done safer and smarter.”

Bans have been proposed. Lawmakers in five states introduced bills this year to ban youth tackle football. Bennet Omalu, the scientist who was the subject of the 2015 film “Concussion,” has called youth football “child abuse” and said that nobody under 18 should play it.

Other experts say banning high school football would be an overreaction. Uzma Samadani, a neurosurgeon and brain injury researcher at Hennepin County Medical Center in Minneapolis, says she sees similar or worse injuries in basketball and swimming. The science on how concussions affect brain function is also much less clear than is often portrayed.

There is a consensus that brain injuries have both short- and long-term consequences, but “what we don’t understand is the relationship between brain injury and all the other things going on in a person’s life,” says Dr. Samadani.

Many also point to football’s developmental benefits, such as building mental resilience and teamwork. “Children benefit far more from football than we realize,” adds Samadani. “If we eliminate it as a sport, I’d be worried that those children would find other ways to injure themselves and not have any benefits.”

Several current and former high school coaches told the Monitor they don’t see a need for kids to play tackle football before seventh grade where, in Texas at least, coaches are professionally certified.

“What parents have to decide is: are the virtues of the game more valuable than the risk?” says Moffett. “If you can teach the virtues at home, through your church,… then don’t play football. But there’s a bunch of kids that don’t get that, and this is where they get it.”

In Texas, the risk and virtues are never too far from the surface.

At an early September game against Kerrville’s Tivy High School, three Fredericksburg players got concussions. But Tivy Antlers football is precious in town. More than 4,000 people show up for home games, and Antler gear is as common a sight in town as college or pro jerseys.

“Kids want to be part of the football team,” says David Jones, Tivy’s head football coach. “So it’s our job as coaches to protect them the very best that we can.”

And while some pro players chafe against new safety rules – lamenting the lost “toughness” of the game – young kids “have never known it the other way,” says Mr. Jones. “What they know is what we’ve told them, how we’re going to do it now, and that’s all they care about.”

Friday night lights

It’s the night the Fredericksburg Battlin’ Billies have been practicing for. At 5-4, the Billies need to win to make the playoffs. The players charge onto the field through an inflatable tunnel crowned with a red billy goat led by Navy JROTCs carrying the American, Texas, and school flags. The Billies’ red helmets shine under the floodlights.

The game is away and the aluminum bleachers at Badger Field in Lampasas lean over the field just a few feet from the sidelines, crowded with spectators layered in sweaters and blankets. The game see-saws back and forth, with Fredericksburg falling behind 35-13 before an improbable comeback – including a long touchdown and a successful onside kick – brings them within two points, 49-47.

Fans on Billies’ sideline are on their feet, blankets forgotten, rattling cowbells and cheering. But on a crucial fourth down late in the game, Lampasas quarterback Ace Whitehead runs a sneak for the yard-and-a-half Lampasas needs. First down. Game over.

Minutes later, the Billies are kneeling near the halfway line. Some players are in tears. Moffett has his hat tucked under his folded arms, his playbook stuffed in his back pocket. “I love all of you,” he says.

“It’s not about winning and losing, it’s about being a team and supporting each other,” he continues. “You’re going to hurt, but you’ll be there for each other.”

There were no concussions or serious injuries in the game. There was a first-half embarrassment, a spirited comeback, and, ultimately, heartbreak.

These are the moments Texas wants to save.

“Football is one of the only avenues that you can teach a kid to get knocked down and get beat up and have to get back up,” says Jones. “It teaches you that that person next to you is a heck of a lot more important than you, and I don’t know where else you learn that.”

“I’ve never been into the toughness of the sport, that’s never been my motivation… I don’t have any qualms about the [safety] changes,” he adds. “We can put our head in the sand and say we don’t like it, but the truth is it’s here.”

Books

Move over, phones! Make room for books that fit in a back pocket.

The latest iteration of the book includes elements people love about their phones: portability and ease of use. Europeans have embraced the new format, but will it have staying power in the United States?

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Diminutive books are typically the fodder of dollhouses and bibliophiles. But an American publisher is hoping readers in the United States will take to a new format of small, horizontal books whose pages flip upward, like swiping a screen on a phone. The tiny books are already a hit in Europe, where versions of works by well-known authors such as Ian McEwan and Dan Brown have sold in the millions. The trend had gone relatively unnoticed in the US until a copy of one of the books arrived at the office of the publisher for John Green, a popular author of novels for teens. Thinking it was a good fit for US readers, she moved forward with a box set of his books, published in October. Some people aren’t sure they are ready to open their wallets, while others are clamoring for more titles. “When cuddling up at home, it is incredibly convenient that they can be held in one hand,” teacher Jessica Hauser writes in an online interview. “After I discovered John Green miniature copies, I searched high and low for others.”

Move over, phones! Make room for books that fit in a back pocket.

Maggie Van Nortwick cradles the book in her palm and flips upward through its razor-thin pages, pausing now and then to read a paragraph or two. Finally, she looks up with a smile.

“This is cute,” she says. “But kind of a curveball for me.”

The book in question, John Green’s debut novel “Looking for Alaska,” measures no more than a few inches on each side. It is cellphone-sized and, unlike regular sized books, can fit easily into a back pocket or small purse. The type is small but readable; the pages barely opaque.

Ms. Van Nortwick, 18, likes the new format, but it may take some getting used to, she says.

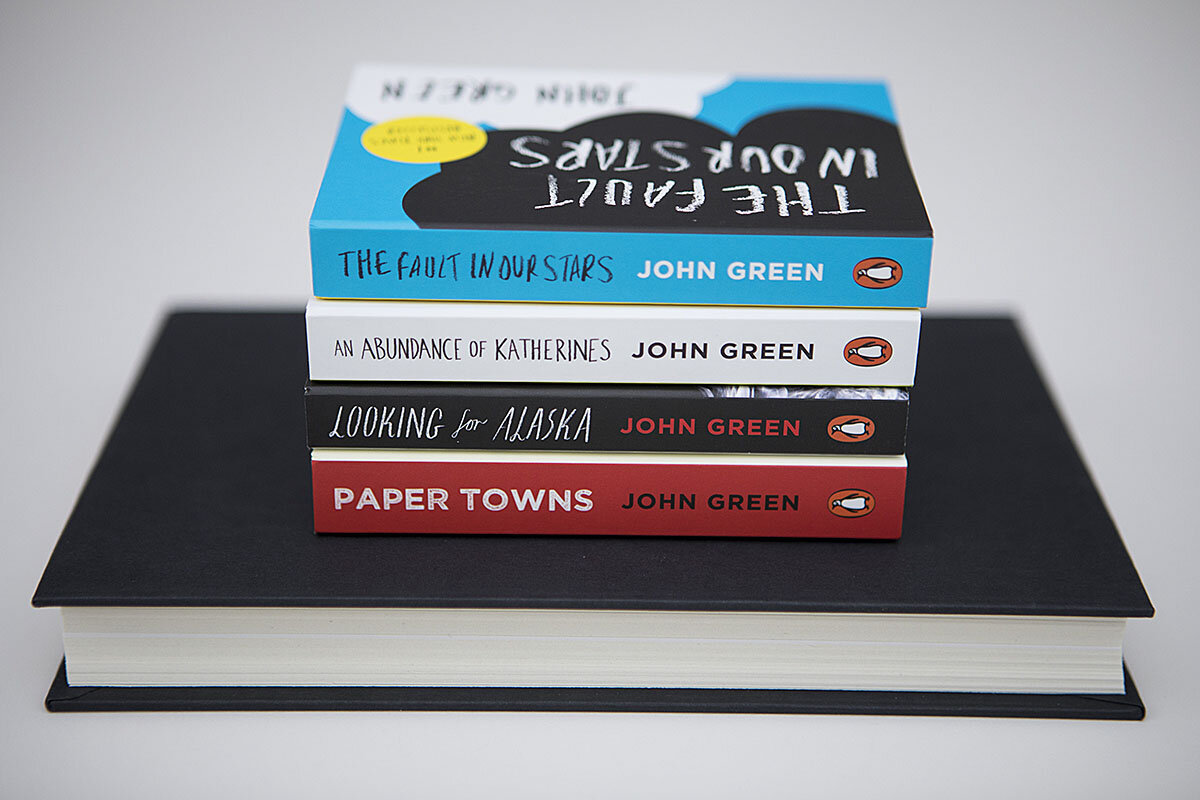

Published by Dutton Books for Young Readers, a division of Penguin Young Readers, the book comes in a box set with three other best-selling novels for teens by Mr. Green, including “The Fault in Our Stars” and “An Abundance of Katherines.” Though most of these books came out years ago – 2005 for “Looking for Alaska” – Dutton recently made the decision to reissue them in a miniature format, called “Penguin Minis.”

Since Johannes Gutenberg first invented the printing press more than 500 years ago, books have remained remarkably stable in format. They have sturdily withstood many predictions of their imminent demise, which have arrived alongside every innovation from paperbacks to ebooks. Penguin, whose orange-spined paperbacks democratized reading in the postwar era by offering classic works at a low price, has a history of disrupting the industry. It launched the mini box set this fall with a 500,000 initial print run. But the question of whether these small, horizontal books will find a life in the United States – beyond that of a passing trend – remains to be seen.

“I don’t think this is going to be the disruptor,” says Carol Jago, associate director of the California Reading and Literature Project at the University of California, Los Angeles. “For every invention and idea that does disrupt how things have been done for years, there are 10,000 others that were interesting ideas but ultimately didn’t make it.”

“But I applaud John Green for taking the chance,” she adds. “Let’s see if there are things we can do to bring kids to reading.”

Small books are nothing new, of course. Miniature books, which measure no more than 3 inches in height, were all the rage among collectors in the 1800s across the US and Europe and some of the oldest tiny tomes date back to the 16th century. Their novelty lay in the odd juxtaposition of diminutive pages containing big ideas – such as religious scripture or Dante’s complete works – that fit snugly into a pocket or a child’s hand.

A 'revelation'

This latest iteration comes from Holland, where a style of book called “Dwarsliggers,” or Flipbacks, has taken off in the past decade. Mini editions by popular authors like Ian McEwan and Dan Brown have sold there in the millions, but the printing method had gone relatively unnoticed in the US. Until, that is, Julie Strauss-Gabel, president and publisher of Dutton Books for Young Readers, received a Dutch copy of one of Green’s novels at her office.

“I picked it up and looked at it, and it was a revelation to see it for the first time,” she says. “It just seemed like something that made so much sense for me, from what I know people want.”

And so she began to gather more information about the Flipback printing process and, later on, decided to move forward with a mini-set by Green. As a popular author with several best-selling novels under his belt, he was a natural choice for the experiment, Ms. Strauss-Gabel says. His name and book covers are recognizable, she notes. Plus, he was excited about the idea from the start.

“Like a lot of writers, I’m a complete nerd for book making and the little details that make a physical book really special,” Green told The New York Times. “[Mini books] didn’t feel like a gimmick, it feels like an interesting, different way to read.”

With Green’s support, Dutton partnered with the Dutch printer Royal Jongbloed in order to produce the English editions, and, after months of careful adjustments, the four-book mini box set came out in October 2018. The books retail for $12 each, or $48 for the set of four. Green fans were delighted, Strauss-Gabel says.

Readers in the US have taken to social media to express their opinions. On Instagram, Jessica Hauser, from Spokane, Wash., wrote “Yay tiny novels!” in a caption for an image of “Looking for Alaska.”

“I really love how portable the tiny books are, but when cuddling up at home, it is incredibly convenient that they can be held in one hand,” the high school English teacher writes in an online interview. “After I discovered John Green miniature copies, I searched high and low for others. I know if Green's sell well the plan is to print others. I am hoping that comes to fruition!”

Some readers still need persuasion

While it seems intuitive that iPhone-sized books would appeal most to Millennials and Generation Z, some older readers appear to relish the concept as well.

“I love that it’s something smaller that I could carry in my back pocket and read as I go along, or sit down to rest and read,” says 80-something reader Bill Callahan as he flips through “The Fault in Our Stars.” “So yeah, I would be interested in that. Though I haven’t actually heard of John Green.”

Tiffany Galloway also likes the format, but the 30-something says she wouldn’t necessarily buy one off the rack.

“I like the traditional size of the book, because well, I’m just so used to it. But it’s not for my age, is it?” she says, “It’s for younger. It would be good for them, just not for me because I’m older and in my ways.”

Based on the success of Flipbacks in Europe, Strauss-Gabel maintains that tiny books are for anyone to enjoy, not just the iPhone generation. She plans to continue expanding the mini-book series to other popular authors, with a new wave of titles for next year.

“When people hold them for the first time, it makes such a difference. So I feel like we got it,” she says. “It has been exciting to watch a response across a very broad range of customers … and it’s just great to see people in love with print.”

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

A first step toward prison reform

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

Crime and punishment trigger conflicting emotions. Most Americans want to know that those who have shown they are a threat to society are securely locked away. They also support the ideas of equal justice and second chances. A “First Step Act” faces potential action in the US Senate before the end of this lame-duck session. The bill offers modest, practical reforms. It opens avenues for those in federal prisons to more easily obtain education and training. It aims to keep prisoners relatively close to family members. It provides for better treatment of pregnant women inmates. Judges would also have more discretion in setting sentences of nonviolent drug offenders. It might be called the “baby steps act,” since it would affect only some of the inmates housed in federal prisons. The vast majority of inmates are in state prisons, which would be unaffected. But it would provide a welcome up note for the end of year, taking a little of the sting out of an era of hyperpartisan politics by proving that working across party lines is still possible.

A first step toward prison reform

The conflicted emotions of Americans about issues of crime and punishment are reflected in the nation’s criminal justice system.

Americans want to feel safe and to know that those who have shown they are a threat to society are securely locked away. But Americans also support the idea of equal justice for everyone under the law and a willingness to give second chances to those who admit their mistakes and show that they sincerely want to change course and become constructive members of society.

A “First Step Act” now faces potential action in the US Senate before the end of the current lame-duck session. The bill seems to have carefully weighed this range of sentiments on crime and offers modest, practical reforms.

Among its provisions, it opens up avenues for those in federal prisons to more easily obtain education and training that could increase the likelihood that they lead crime-free lives after release. It also would take a small step toward cutting the immense cost of the nation’s massive prison system and remove an inequity in prison sentencing.

A somewhat different version of the bill passed the House earlier this year by a wide margin, 360 to 59, earning broad bipartisan support.

The Senate version would likely gain similar backing from both Republicans and Democrats if it reaches a vote. President Trump has signaled he would sign the legislation if it reaches his desk.

Under the proposed law, federal prisoners who participate in programs aimed at helping them stay out of prison after their release, including educational and training programs, could cut days off of their sentence. Judges would also have more discretion in setting sentences of nonviolent drug offenders.

Those imprisoned for crimes involving crack cocaine would receive sentences in line with those whose crimes involved powder cocaine, and sentences would be readjusted back to 2010. Crack cocaine crimes, more prevalent in African-American communities, have received harsher penalties than powder cocaine crimes, more prevalent white areas.

Better efforts would be made to make sure prisoners are located within 500 miles of family members. (Family support has been shown to be important in preventing recidivism.) And authorities in federal prisons would not be allowed to shackle pregnant women inmates with chains while they are in labor giving birth.

The bill might be called the “baby steps act” since it would affect only some of the inmates housed in federal prisons. The vast majority of inmates are in state prisons, which would not be affected by the legislation.

Some states have begun reform measures of their own in recent years, but most have not. A federal action, though modest in scope, might provide a powerful example that causes more states to act.

Among the senators supporting the bill is Amy Klobuchar (D) of Minnesota, who has called it “an effective balance between keeping our communities safe and ensuring the fair administration of justice.” It has also won support from major police organizations “because they know this legislation keeps significant penalties in place for violent offenders,” Senator Klobuchar says.

Sen. Charles Grassley (R) of Iowa, a cosponsor of the bill, points out that the last days of the current Congress provide the optimum moment for passage. In January, the new Congress will feature a Democratic majority in the House, which will bring with it a long list of new priorities. It might wish to alter or add to the bill in ways that would prevent passage in the Republican-held Senate.

The “First Step Act” would also provide a welcome up note for the end of year, taking a little of the sting out of an era of hyperpartisan politics by proving that working across party lines is still possible.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Gratitude heals

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Michelle Boccanfuso Nanouche

Today’s contributor shares how a spirit of gratitude replaced the “poor me” discouragement she’d been feeling about a lingering illness with a tangible sense of God’s presence, and healing quickly followed.

Gratitude heals

Settling into my airplane seat on the next leg of a long business trip, I heard a man say to his seat companion behind me, “I am so happy we live here. I love our home. I love our neighbors.” I didn’t really want to eavesdrop, but the sincerity in his voice drew me in. Next I heard, “I am grateful for our friends and for my work here. I am grateful for you!”

This flight was a year ago, yet I still remember his words clearly. Why? Because his list of heartfelt gratitude made me feel grateful, too. I considered the good in my life and all around me, and a fatigue that had accompanied me onto the flight dropped away completely, allowing me to arrive at my next stop joyful and energetic.

More than just positive thinking, gratitude can be a powerful, spiritual force for good, rendering one receptive to healing. I once found myself in desperate straits, and gratitude was key to my turnaround. I had been ill for some time and became very discouraged. The list of what was wrong seemed to grow every hour, and I was very tired of it all.

Seeking inspiration, I opened my Bible to Habakkuk, a book that was rather unfamiliar to me. As I began to read, I noted a lot of “woe is this” and “woe is that,” and oh, my, could I ever relate! But as I continued reading, I was struck by a sudden corrective to the negative flow: “But the Lord is in his holy temple: let all the earth keep silence before him” (2:20).

To me, this was like a big “Shut up!” to the list of woes stirring around in my own thoughts. In the 1932 “Christian Science Hymnal” there is a verse I love:

“A grateful heart a temple is,

A shrine so pure and white,

Where angels of His presence keep

Calm watch by day or night.”

(Ethel Wasgatt Dennis, No. 3, © CSBD)

I considered how the antidote to any woe could be found in the holy “temple” of gratitude, of acknowledging God as abundant, divine good. The good that comes from God, who knows only peace and harmony, is more powerful than any evil, because it is unlimited.

These ideas stirred a change in me. I began to more consciously dwell in that temple of gratitude, considering the evidence of good from God in my life.

As I did this, I learned that it is impossible to be discouraged and truly grateful at the same time. Genuine gratitude is a manifestation of God’s goodness reflected in us. Such gratitude isn’t of human origin. It is a divine attribute, reflected in each one of us as God’s creation. This means no one can be shut out of the temple of gratitude – everyone is capable of feeling grateful, no matter what the human circumstance may be.

This doesn’t mean simply forgetting about or ignoring bad things. On the contrary, acknowledging the supremacy of God, good, equips us to overcome challenges. It magnifies God’s goodness in tangible ways. As we acknowledge the presence of spiritual good for all, gratitude expands in our consciousness and displaces mental darkness, doubt, and discouragement.

In my case, gratitude cut off the “poor me” discouragement that distracted me from knowing, hearing, and feeling God’s presence, or healing Christ – God’s message of love for each and every one of us, which Jesus expressed so fully. And I began to recover quickly from the illness. In fact, within a very short time, I was completely well.

In the United States, Thanksgiving Day is celebrated in late November, but a spirit of gratitude is a healthy mental state every day of the year. Here is the whole of the hymn mentioned earlier, which reminds us of what a grateful heart is and does for us all:

“A grateful heart a garden is,

Where there is always room

For every lovely, Godlike grace

To come to perfect bloom.A grateful heart a fortress is,

A staunch and rugged tower,

Where God’s omnipotence, revealed,

Girds man with mighty power.A grateful heart a temple is,

A shrine so pure and white,

Where angels of His presence keep

Calm watch by day or night.Grant then, dear Father-Mother, God,

Whatever else befall,

This largess of a grateful heart

That loves and blesses all.”

A message of love

A little less lean

A look ahead

Thanks again for being with us. Come back Monday. In the next installment of our migration series, On the Move, Ryan Lenora Brown reports from Gambia on how European Union-funded job creation programs in that tiny African country seek to redefine the “Gambian Dream” so that its citizens will feel more confident that they can make it there rather than leaving home.