- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usMonitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Bush and the personal connection

After President George H.W. Bush’s passing, the Monitor’s Howard LaFranchi messaged me. Like several Monitor staffers, he had a memory to share about Mr. Bush’s well-known love for letter-writing and personal connection.

It revolved around Houston’s Buffalo Bayou, which Howard wrote about in 1988. The story mentioned that two decades earlier, then-Congressman Bush backed an effort to protect the river. Soon, Howard received a letter from a preservationist he had interviewed. She enclosed a letter from now-Vice President Bush, who’d seen the article and written that he remembered fondly her good works for Houston.

“I remember thinking, ‘Wow, this guy is VP, and he takes the time to write,’ ” says Howard. “I’ve never forgotten it.”

Then Bush became president. Senior Washington writer Peter Grier recalls witnessing Bush’s connection with troops he visited during the Gulf War. “He started throwing presidential pins and cufflinks into the crowd with a left-handed sling motion, so much like the Yale baseball player from long ago. He was smiling – and the troops loved it.”

And then there was Bush’s failed bid for a second term. Retired Monitor political writer John Dillin recalls interviewing Bush at the White House. When it emerged John was from Florida, Bush asked how he was doing there. “Pretty well with most of my family,” John replied, “but not my mother.” Bush asked for her number and picked up the phone. “She wouldn’t budge,” John recalls, chuckling, but the effort was impressive.

Now to our five stories, including an appreciation of President Bush’s long career and an editorial about public service.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Trump and Xi step back from trade war, but for how long?

The US-China cease-fire was the headline of the G20 summit. But there's another story worth watching as well: China's President Xi presenting himself as the new champion of multilateralism.

The dinner meeting that stole the show at the G20 summit in Buenos Aires concluded with a deal: a cease-fire in the intensifying US-China trade war. Yet while the agreement reached between Presidents Trump and Xi Jinping produced an almost audible global sigh of relief, experts foresee an arduous road ahead in addressing the broader confrontation between a retreating global superpower and a China that is rising rapidly. “They’ve kicked the can down the road for 90 days,” says Joel Trachtman, a professor at Tufts University’s Fletcher School. “But I don’t think [the agreement] deals with the fundamentals of the strategic-position conflict.” China’s rise as a global power was on display at the two-day summit. What bothers some about a US retreat from global leadership is that it risks ceding ground to the very illiberal and authoritarian forces the US-led system aimed to hold in check. For some, the exuberant high-five fist grab between Vladimir Putin and Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman – two leaders seen to have dissidents’ blood on their hands – represented a kind of secret handshake of the world’s increasingly unleashed authoritarians.

Trump and Xi step back from trade war, but for how long?

When President Trump sat down to his much-anticipated Buenos Aires dinner with Xi Jinping Saturday night, he praised the personal relationship he’s developed with the Chinese leader and predicted it would lead to good things for both countries.

“The relationship is very special … that I have with President Xi,” Mr. Trump said, flanked by Treasury Secretary Steve Mnuchin and other senior aides, and seated directly across from a smiling Xi. Indeed, that special relationship was the “primary reason,” Trump added, that he expected the two of them would agree on something “that would be good for China and good for the United States.”

Two-and-a-half hours later, the dinner meeting that stole the show at the weekend’s G20 summit concluded with a deal: a suspension of the intensifying trade war between the world’s two largest economies that international economists have said is beginning to threaten global economic growth.

Trump agreed not to follow through on plans to more than double on Jan. 1 the 10 percent tariffs the US has already imposed on $200 billion in Chinese goods, while Xi agreed to boost purchases of American farm goods and other products. Indeed, Trump said the Chinese would be cutting tariffs and “buying massive amounts of products from us.”

Both countries agreed to a fresh round of trade talks, to commence this month and stretch into next spring, that are intended to reach beyond questions of tariffs to discord over China’s state-based industrial policy and intellectual property protections.

And in what White House press secretary Sarah Sanders called a “wonderful humanitarian gesture,” China agreed to designate Fentanyl as a controlled substance. Chinese Fentanyl is a major contributor to the US opioid crisis.

Yet while the agreement reached between the two leaders produced an almost audible global sigh of relief, it is widely seen as little more than a cease-fire in the unresolved trade conflict between the world’s two economic giants.

“There may be temporary cease-fires along the way, but those will do little more than put off the broader issues at the heart of the intensifying competition between China and the United States,” says Roberto Bouzas, professor of international economics at Universidad de San Andres in Buenos Aires.

Moreover, while the accord postpones the threat of a deepening trade war, experts foresee an arduous road ahead in addressing the broader geopolitical confrontation between a retreating global superpower and a China that is rising rapidly to grasp at global leadership. At stake: not just trade and state-directed versus private-enterprise economic models, but also issues ranging from Asian security to regional development models.

“They’ve kicked the can down the road for 90 days, a period of time in which they pledge to take up not just tariffs but things like forced technology transfer [for American companies seeking to enter the Chinese market] and IP [intellectual property] protections,” says Joel Trachtman, professor of international law at Tufts University’s Fletcher School in Medford, Mass. “But I don’t think it deals with the fundamentals of the strategic-position conflict. To address that, China has got to stop growing and adding technological prowess,” he adds, “and that’s not going to happen.”

As Professor Bouzas notes, the difference between the US and Chinese economies has shrunk. As recently as 2000, the US economy was more than eight times larger than China's. By 2016, the US economy only stood at about one and a half times larger than China's.

China's rise on display

China’s rise as a global power was on display at the two-day G20 summit of the world’s major economies, while an uncharacteristically subdued and withdrawn Trump symbolized for some the US retreat from its once-hyper-dominant position in global economic affairs and the advent of a multipolar – some say leaderless – world.

Xi presented himself as a champion of multilateralism, attending a number of side meetings with groups of leaders on multilateral issues – such as one with French President Emmanuel Macron and United Nations Secretary General Antonio Guterres on advancing the Paris climate accords.

Trump, who has made clear his disdain for large international gatherings and multilateral diplomacy, emphasized his preferred bilateral diplomatic approach – and even then either canceled or downgraded a number of his planned bilateral meetings. He canceled his anticipated sit-down with Russian President Vladimir Putin, for example, citing Russia’s seizure late last month of Ukrainian vessels and sailors. He downgraded planned meetings with South Korea’s Moon Jae-in and Turkey’s Recep Tayyip Erdoğan to brief stand-up chats.

The US did agree to sign on to the summit final communique – something Argentine organizers had fretted about after Trump memorably refused to sign on to the statement issued by leaders at last June’s G7 summit in Canada.

But even in the communique the US stood apart from the rest, insisting on a paragraph noting its withdrawal from the Paris climate accords – which all other summit participants reconfirmed as a vital part of global cooperation and action.

Trump administration officials also cited as a success language in the statement that underscores a need for reform and “improvement” of the global trading system and specifically the World Trade Organization.

But some experts said the language stating that the global trading system “is currently falling short of its objectives” could hardly be objectionable to anyone.

Moreover, it hardly reflects the harshest of Trump administration criticisms of China’s trade practices – including that China fuels its economic rise in part through stealing American intellectual property, or forcing American companies to turn over their proprietary technologies as part of securing joint-ventures with Chinese companies.

Global patience with US?

In a particularly damning report last March, US Trade Representative Robert Lighthizer concluded that China seeks to dominate future technologies. More recently. Mr. Lighthizer, one of the administration’s China hawks, said China has not altered its deceptive activities despite US pressure.

The Fletcher School’s Professor Trachtman says the language in the G20 communique falls far short of Trump’s past attacks on the WTO – which have included threats to bow out of the global trade organization.

Instead, what Trachtman sees in the communique’s WTO language and reference to US objections to the Paris accords is a kind of accommodation of current US leadership that seeks to limit deeper damage to the international system of governance.

“I think we’re seeing expressions of a new strategic patience on the part of the rest of the world,” says Trachtman, “with other leaders saying, ‘We’re not going to turn away from the Paris climate accords, we’re not going to turn away from the WTO, but we’ll let the US take this divergent path for now, and we’ll wait for a more amenable negotiating partner in managing the global trade system and other multilateral efforts.’ ”

One White House official, speaking to journalists on condition of anonymity, said the communique included “some of the United States’ biggest objectives.” Those included the separate paragraph noting US withdrawal from the Paris accords, and removal of draft language on multilateralism and protectionism.

Perhaps most notable to the more than 2,500 journalists from around the world assembled at the summit was Trump’s cancellation of his planned press conference at the G20’s conclusion. As one European journalist who had witnessed Trump’s feisty and confrontational performance at last June’s NATO summit wondered, “Where’s the Trump who makes a show out of press conferences and loves to bash allies?”

White House officials said the press conference was canceled out of respect for the late President George H. W. Bush, who passed on Friday. And as for allies, Trump did honor a planned meeting with German Chancellor Angela Merkel, calling her a “friend” and praised their “great working relationship.”

Authoritarian handshake

Still, some summit participants saw reflection of a larger US global withdrawal in Trump’s toned-down participation. And what bothers some about a US retreat from global leadership is that it risks ceding ground to the very illiberal and authoritarian forces the US-led system has aimed to hold in check.

For some, the exuberant greetings exchanged by Mr. Putin and Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman represented a kind of secret handshake of the world’s growing and increasingly unleashed authoritarians.

Argentine President Mauricio Macri hailed the summit as a resounding success for “global consensus,” but some Argentine observers worried publicly that the iconic image of this G20 summit will be of the hybrid high-five fist-grab between Putin and the crown prince Mohammed bin Salman – two leaders widely seen to have the blood of domestic dissidents on their hands.

The CIA has determined with high confidence that the crown prince authorized the killing of Saudi journalist and US resident Jamal Khashoggi, while British intelligence concluded that Putin signed off on the poisoning of a dissident former Russian spy and his daughter living in Britain.

Noting the absence at the summit of a robust US leadership role, some analysts said the two leaders’ high-five would live on to symbolize the free path the US has ceded to advancing strongman rule.

Remembering George H.W. Bush, a calm hand in a turbulent time

As the United States pays tribute to President George Herbert Walker Bush, who died Friday, many are recalling a long résumé of public service that profoundly shaped his tenure in the White House.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 9 Min. )

When George H.W. Bush was elected president in 1988, he’d already been a party official, a member of Congress, an ambassador, a spy, and a veep. Detractors saw his presidency as detached and overly cautious; supporters lauded his humanity and prudence as just what the nation needed during a time of tremendous geopolitical change. President Bush lost his reelection bid in 1992, in part due to his decision to break a campaign pledge and raise taxes with a recession looming on the horizon. His own advisers admitted that domestic policy was not his strongest area, despite wide knowledge of issues gained during eight years of service as Ronald Reagan’s vice president. His great successes were his skillful handling of the Gulf War, which ousted Iraq’s Saddam Hussein from Kuwait, and his leadership of the noncommunist world through the tumult and danger of its final face-off with the Soviet empire. “We have only learned in recent years what an incredible job he did keeping the cold war from turning hot,” says Jeffrey Engel, director of the Center for Presidential History at Southern Methodist University.

Remembering George H.W. Bush, a calm hand in a turbulent time

At approximately 3 o’clock in the afternoon of Nov. 9, 1989, National Security Advisor Brent Scowcroft walked into the Oval Office to tell President George H.W. Bush stunning news: The Berlin Wall was open. East Germans were joyfully entering the West, and vice versa. A long stasis enforced by cold war barriers was beginning to break down.

Press Secretary Marlin Fitzwater pushed for Mr. Bush to talk to reporters, or at least issue a statement. It was too important a moment to keep quiet, he said. The White House press corps was screaming for a presidential comment. There wasn’t time for the US to wait and figure out exactly what was going on.

But Bush, backed by General Scowcroft, was reluctant. Was this a local event or something approved by the East German government? More importantly, how would the Soviet Union react? Would US gloating goad them into an armed response?

Eventually Bush allowed a press pool into the Oval. He talked for half an hour and basically said nothing. At the end, CBS reporter Leslie Stahl said, “You don’t seem very happy about this. Isn’t this the fundamental breakthrough in the cold war?”

“Well, I’m not an excitable kind of guy,” Bush replied.

George Herbert Walker Bush, who died Friday, was a lanky Yale graduate and World War II hero whose résumé of public service made him perhaps the most experienced candidate elected to the White House in the modern age. Detractors saw his presidency as detached and overly cautious; supporters lauded his humanity and prudence as just what the nation needed during a time of tremendous geopolitical change.

Bush lost his reelection bid in 1992, in part due to his decision to break a campaign pledge and raise taxes with a recession looming on the horizon. His own advisers admitted that domestic policy was not his strongest area, despite wide knowledge of issues gained during eight years of service as Ronald Reagan’s vice president.

His great successes were his skillful organization and handling of the Gulf War, which ousted Iraq’s Saddam Hussein from Kuwait, and his leadership of the noncommunist world through the tumult and danger of its final face-off with the Soviet empire.

“It was one of the most fundamental changes in world history, and the fact that it took place at all, and so rapidly and almost literally without a shot being fired, is an incredible epic,” Scowcroft said years later in an oral history collected by the Miller Center of the University of Virginia.

New England upbringing

Bush was born in Milton, Mass., on June 12, 1924, into a wealthy New England family. He became the middle part of an American political dynasty, though the Bushes would probably reject that tag as self-aggrandizing.

His father, Prescott Bush, was a Wall Street banker who served as a US senator from Connecticut from 1952 to 1963. His eldest son, George W. Bush, was the 43rd president of the US. Second son Jeb was governor of Florida; Jeb’s son George P. Bush was elected Commissioner of the Texas General Land Office in 2014, extending the dynasty into a fourth generation.

“They are like the Kennedys in many ways,” says Barbara A. Perry, director of Presidential Studies at the Miller Center, of the Bush family.

Like the Kennedys, the Bushes sent their sons to Ivy League schools. Like the Kennedys, the sons of the World War II generation volunteered, not just for military service, but also for highly dangerous missions, such as John F. Kennedy’s PT boat command and George H.W. Bush’s piloting of Navy carrier aircraft.

Unlike the Kennedys, the Bushes were WASP establishment stock, and had been for generations. And, of course, all to this point have served as Republicans.

During World War II, Bush was in fact the youngest bomber pilot in the Navy. He enlisted upon graduation from Philips Andover Academy, and was commissioned an officer on June 9, 1943, three days prior to his 19th birthday. He flew torpedo bombers in the Pacific theater, reaching 58 combat missions. On Sept. 2, 1944, while attacking a Japanese radio site, his TBM Avenger was shot down by anti-aircraft fire. Bush bailed out over the ocean and was rescued by a US submarine. Two crew members were never found. The loss of his compatriots shaped Bush profoundly. “Why had I been spared and what did God have for me?” he later wrote.

Bush married Barbara Pierce on Jan. 6, 1945. He’d met her at a Christmas dance in 1941; she was wearing a pretty red-and-green dress lent by a friend of her mother’s, and he made sure to seek her out at a second dance the following evening. For both, that first meeting was all it took. They were married 73 years prior to her passing in April. It was the longest presidential marriage in US history.

Long story short, Bush graduated from Yale and moved his young family to Texas. He got an entry into the oil business via a reference from his father, and worked his way up. And he took his first step into politics, winning election as the Republican Party chairman in Harris County.

Political aspirations

He ran for US Senate and lost, ran for Congress and won (twice), ran for Senate and lost again. In Bush’s big leap to the national stage, President Richard Nixon picked him as ambassador to the United Nations. Critics said he was unqualified – not enough foreign policy experience.

Nixon moved Bush to chairmanship of the Republican National Committee in 1973 due to the latter’s upstanding reputation, something Nixon needed as Watergate burned around him. President Gerald Ford appointed Bush chief US diplomat to China – a job in which Bush made many contacts useful in later diplomacy – and then head of the CIA.

In 1980, he ran for president himself. He won the Iowa caucuses, but lost the New Hampshire primary to former California Gov. Ronald Reagan, who quickly gained the upper hand in the GOP nomination race. Bush hung on but eventually dropped out early enough to stay in Reagan’s good graces. Reagan picked him as VP, in part due to his international experience, in part due to his reputation as a moderate Republican. Bush was grateful, and always treated Reagan with respect.

When President Reagan was wounded in an assassination attempt a few months into his first term, Bush was in Texas. He hurried back to D.C. to demonstrate continuity of government. Aides suggested he helicopter from Andrews Air Force Base directly to the White House. He vetoed the idea.

“Only the president lands on the South Lawn,” he said.

Bush won the presidency in his own right in 1988. On Inauguration Day, 1989, he was waiting inside the US Capitol for the precise moment to be escorted to the swearing-in platform. It was the most important day of his life. And he noticed that outgoing president Reagan was wearing his overcoat.

The problem was, Bush wasn’t. Wearing his overcoat that is. The day was warm by Washington standards, but Bush was concerned about appearing more robust than his predecessor, according to his former personal aide Timothy McBride. Bush’s coat was locked in a limo four levels below. Mr. McBride lent him his own overcoat, which was about the right size.

“Even on that day, he’s worried about outshining President Reagan,” McBride said in his oral history of the Bush administration.

Critics called Bush Ronald Reagan’s “lapdog.”

By many measures, Bush was the most experienced person elected US president, at least in the modern age. He’d been a party official, an elected representative, an ambassador, a spy, and a veep.

His knowledge of policy was deep – certainly more detailed than his predecessor’s. At one point during the struggle over renewal of the Clear Air Act, Roger Smith, CEO of General Motors, arrived for discussions. It quickly became apparent to the White House staff that the president knew far more about the chemical components of auto emissions than did the car executive.

None of that information had been in White House briefing books prepared for the visit, according to Bobbie Greene Kilberg, the public liaison staffer who’d set the meeting up. She asked the president where the heck that stuff had come from.

“I have been vice president for eight years, thank you very much. I do read,” Bush said in reply.

Passage of amendments expanding the Clean Air Act to fight acid rain, ozone depletion, and other key atmospheric threats was one of the Bush administration’s major accomplishments in domestic policy. Another was passage of the 1990 budget deal, which prepared the way for the federal budget surpluses of the early 1990s, but may have sealed Bush’s 1992 reelection defeat. In signing it, Bush broke his “read my lips, no new taxes” pledge made at the 1988 Republican National Convention.

A legacy of international leadership

But foreign policy was Bush’s main interest – and the country’s main need. The tectonic plates of geopolitics were moving. The Bush 41 (as in, “41st US president”) years constituted the most internationally complex presidency since that of Franklin Delano Roosevelt, in the opinion of Jeffrey A. Engel, director of the Center for Presidential History at Southern Methodist University and author of “When the World Seemed New: George H.W. Bush and the End of the Cold War.”

Today, the Gulf War seems as if it must have been Bush’s biggest challenge. Assembly and maintenance of a vast coalition required diplomatic deftness – within two days of the beginning of hostilities, Bush personally called 120 world leaders, many of whom he personally knew. The last World War II president felt a heavy responsibility sending US troops into combat. The speech announcing hostilities was the only address of his presidency that he wrote himself from start to finish.

But Dr. Engel and other experts – including Scowcroft and other top officials – believe that the management of the collapse of the Soviet Union was Bush’s most important test and greatest achievement.

“We have only learned in recent years what an incredible job he did keeping the cold war from turning hot,” says Engel.

Germany was the central issue (as it was for much of the 20th century). As Bush took office, the collapse of communist authority in much of Eastern Europe was beginning to threaten the Soviet Union itself. How to manage this decline without provoking Soviet hardliners, while keeping NATO united?

Initially Bush employed “Hippocratic diplomacy” – first, do no harm. This explains his hesitance to dance in victory at the fall of the Berlin Wall. History seemed to be moving in the West’s direction. No need to mess things up by attempting to speed it along.

He switched to action for the German question. Almost alone among non-Germanic Western leaders, Bush favored fast, total German reunification. The key was keeping a unified Germany in NATO. He sold this deal to France and Britain, pointing out it was the best way to keep US troops in Europe. Meanwhile, he promised the USSR’s Mikhail Gorbachev economic aid, and restraint from NATO in pushing eastward toward his border. (Subsequent presidents have ignored the “restraint moving east” part of this pledge, to Vladimir Putin’s chagrin.)

At a summit meeting in June 1990, Mr. Gorbachev off-handedly indicated that a united Germany could remain in the Western military alliance. Top Soviet officials then began arguing among themselves. At that moment, recounted Scowcroft, he knew the US had won. He stopped crossing out the line “the cold war is over” from speechwriters’ drafts.

“You know, the cold war profoundly affected all of us,” Scowcroft said in his oral history. “It infused every part of our lives. It was a pattern of thinking. It was the world that we knew.”

'This is really something to see'

George H.W. Bush was not an eloquent man himself. Ronald Reagan could move the nation with his words in the wake of the explosion of the space shuttle “Challenger.” For Bush, that would have been a difficult enterprise.

Talking about troops could choke him up. Early in his administration Bush spoke at a memorial service for sailors from the USS Iowa who had died in a turret explosion. Aides, following along on their copies, could tell that he ended the address abruptly, leaving paragraphs unread. The reason? The president of the United States was starting to cry.

Before the Gulf War started, Bush traveled to Saudi Arabia to visit US service members on Thanksgiving. He’d stonily forced his speechwriters to delete “soft stuff” from his prepared remarks – parents writing to praise their kids in uniform, saying the US was doing the right thing, and so forth.

As the day went and his appearances piled up the speeches got shorter. It wasn’t just that Bush did not want to say much. He didn’t have to.

The last event was at a forward Marine base reached only by helicopter and flatbed truck. The sun was going down. Bush used maybe 10 percent of his speech, and then walked among the soldiers, who swarmed around him, reaching out for a touch. It was a vivid and emotional moment.

“It was very kind of, ‘Wow, this is really something to see’,” White House communications director David Demarest Jr. said in his oral history. “He got up to where he was going to speak and I realized that he doesn’t have to say anything. Just him being here is amazing, and that’s the story.”

Oakland’s plan to battle homelessness: Stop it before it starts

When a city offers a model for dealing with the social impact of rising rents, it's worth taking note. In this case, the story is about Oakland, Calif., which is working to fight homelessness and gentrification before they take root.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Gentrification has swept across California’s Bay Area amid the region’s tech boom, displacing low-income tenants as the homeless population surges. In Oakland, where more than 2,700 people lack permanent shelter, officials have launched a $9 million, four-year pilot initiative to prevent homelessness before it occurs. Keep Oakland Housed combines a rapid response to renters’ financial and legal crises with long-range guidance to maintain their stability. “It’s smarter and more humane to keep people housed instead of waiting until they’re homeless to help them,” Mayor Libby Schaaf says. In its first six weeks, the program helped 150 households avert eviction, including Debra Ross and her grandson, who live in a subsidized apartment on the city’s east side. She owed $785 in back rent, and within two days of contacting Keep Oakland Housed, the program sent the payment to her landlord. “It felt like a miracle,” she says. The program also provides legal services to deter property managers looking to evict tenants as a ploy to boost the rent on units. Says Frank Martin, deputy director of the East Bay Community Law Center, “Having lawyers who will negotiate settlements with landlords or who show up in court with tenants levels the playing field.”

Oakland’s plan to battle homelessness: Stop it before it starts

The tears began falling before Debra Ross finished reading the eviction notice. She had arrived home on a June afternoon to find the piece of paper taped to the door of her apartment in Oakland, Calif., where she lives with one of her 20 grandchildren.

Ms. Ross owed $785 in back rent on her subsidized unit on the city’s east side. She and her teenage grandson survive on the $770 she receives from the state as his legal guardian, and the notice placed them in jeopardy of homelessness. She pleaded for time from the property manager, who agreed to let her defer payment until the fall. But with Ross still short on money as the Oct. 31 deadline neared, a final eviction notice appeared on her door.

With only three days to spare, while reading a friend’s Facebook page, she learned about a program called Keep Oakland Housed that had launched earlier that month.

The $9 million, four-year pilot initiative, funded by the San Francisco Foundation and Kaiser Permanente, offers emergency financial assistance, supportive services, and legal representation to low-income tenants on the brink of eviction. Ross contacted the program, and two days later, a case manager sent a payment of $785 to her landlord.

“It felt like a miracle,” she says, her voice cracking. She had ended up homeless three years ago when the city shut down the building where she then lived over code violations. “Older folks like me are really vulnerable. When we lose our homes, it’s hard to find another one. It’s the kind of thing that can kill you – literally kill you.”

Gentrification has swept across the San Francisco Bay Area amid the region’s tech boom, displacing low-income tenants as rents rise and the homeless population surges. Oakland’s biennial homeless survey, last conducted in January 2017, showed the number of people who lacked permanent shelter had climbed to 2,761, an increase of almost 600 from two years earlier. The homeless population had risen at the same time the unemployment rate was falling.

Keep Oakland Housed represents the city’s preemptive strike against that growing problem and one potential strategy for the state – and the country – to alleviate its affordable housing shortage. Supporters describe the program as vital for protecting the most vulnerable residents as much as the city’s own identity against the forces of gentrification.

“What has made Oakland an amazing place to live is its diversity: economic, ethnic, cultural,” says Daniel Cooperman, director of programs for Bay Area Community Services, one of three nonprofits that administer the program. “The coffee shops, the yoga studios – those things are great. But there’s a cost that comes along with that, and now Oakland is almost becoming a suburb of San Francisco.”

The program attempts to stop homelessness before it starts and, as a secondary effect, to deter landlords from converting low-income units to market-rate housing. The multi-pronged approach combines a rapid response to the financial and legal crises of renters with long-range guidance to maintain their stability.

In its first six weeks, Keep Oakland Housed supplied financial support to 150 households to avert evictions and assisted 110 tenants in settling landlord disputes, according to the San Francisco Foundation. By shielding renters from unjust evictions, Oakland Mayor Libby Schaaf asserts, the city will counter the impact of redevelopment while retaining its unique character.

“Oakland has always fiercely prided itself on its diversity,” she says, “and this program is intended to help preserve that identity, that sense of community where people have their roots. We don’t want to rip them out of the place they call home.”

‘For anyone in need’

In the past year, Oakland has allocated more than $1 million in public and private funding to place dozens of prefabricated storage sheds at three sites across the city to provide temporary shelter for 240 people. The city plans to devote $4.5 million in state funding to open and operate three more shed sites for another 320 people over the next 18 months, one of several recent initiatives to address the homelessness crisis.

Almost half of Alameda County’s homeless population of 5,600 lives in Oakland and Mayor Schaaf regards the $9 million stake for Keep Oakland Housed as a chance to slow that rising tide.

“It’s smarter and more humane to keep people housed instead of waiting until they’re homeless to help them,” she says. “It’s not just about having a roof over your head. It’s about the support networks – neighbors, schools, doctors – that we all need around us.”

The city joined with Bay Area Community Services, Catholic Charities of the East Bay, and East Bay Community Law Center to create the program. Residents who earn 50 percent or less of the area’s median income can qualify for assistance – a threshold of $40,700 for one person or $58,100 for a family of four – and receive as much as $7,000 in aid. Case managers disburse the money straight to landlords or third-party vendors to cover a tenant’s lapsed payments on rent, utility bills, or other expenses.

The city’s housing advocates have long realized that intervening before landlords evict tenants offers the strongest remedy to the homelessness epidemic, explains Karen Erickson, director of housing and financial services for Catholic Charities in Oakland. They also understood that, without funding, the concept would remain a well-intentioned aspiration.

“The best way to combat homelessness is to prevent it in the first place,” Ms. Erickson says. “But there have been no prevention dollars. It has been a big deficiency.”

Unlike programs that target a specific demographic – veterans, single mothers, seniors – Keep Oakland Housed accepts anyone who meets its income criteria. The broad eligibility rules suggest a recognition of the effects of gentrification beyond tenants on a fixed income.

Erickson shares the example of a medical researcher whose employer laid her off earlier this year. The woman found work within a month, yet the loss of a couple of paychecks left her unable to cover a month’s rent. The program paid the difference, and she staved off eviction.

“Preventing homelessness isn’t just for certain classes of people,” Erickson says. “It’s for anyone in need. It’s an issue of human dignity.”

‘The place I know’

A handful of cities in California and elsewhere operate variations on Keep Oakland Housed, including San Francisco, New York, and Chicago. Beyond financial aid, the programs seek to help renters avoid a recurrence of the problems that imperiled their living situation.

Case managers in Oakland work with tenants to organize their household budgets and apply for assistance to lower their utility and phone bills. For residents in need of mental health or substance abuse counseling, job training, or education planning, the program provides in-house resources and referrals to other agencies.

“We don’t want to just be check writers,” Erickson says. “There’s usually a lot more going on, and without addressing those things, people can continue to struggle.”

Trena Burton had accrued a $6,800 utility debt over the past decade as she reassembled her life after a stint behind bars for fraud and forgery. Keep Oakland Housed covered the full amount and delivered a measure of peace for Ms. Burton, an in-home health aide who supports her adult daughter and teenage son.

“This is my community, my home, the place I know,” she says. “We need to keep everyone in mind, not just the wealthy.”

California’s affordable housing shortage of 1.5 million units accounts for a fifth of the 7.2 million units needed across the country. Meanwhile, the state’s voters rejected a ballot measure last month that would have enabled cities to enact stronger rent control policies, curbing soaring rents and acting as a check on landlords.

Two years ago, Schaaf unveiled a plan to preserve 17,000 affordable housing units and add another 17,000 in Oakland, which imposes rent control on buildings constructed before 1983. In the view of Frank Martin, deputy director of the East Bay Community Law Center, the legal services offered by Keep Oakland Housed will give pause to property managers looking to evict tenants as a ploy to boost rent.

“Generally speaking, 90 percent of landlords have lawyers and 90 percent of tenants do not,” he says. “That makes for an imbalance and leads to people losing their cases even when they have legitimate reasons for why they couldn’t pay their rent. Having lawyers who will negotiate settlements with landlords or who show up in court with tenants levels the playing field.”

For Ross, liberated from the $785 debt that brought her and her grandson to the edge of eviction, Keep Oakland Housed has freed her to dream of a new future in the town she loves.

She spends much of her time decorating blank baseball hats with sequins, beads, lace, and other materials. She sells the colorful creations to friends and acquaintances, and next year, she hopes to turn her hobby into a business. The change in her circumstance from a month ago inspires talk of divine intervention.

“To see that eviction notice on my door, it was devastating,” Ross says. “I was so frightened. I didn’t know what to do. I feel like God was looking out for us.”

Perception Gaps

Beyond opioids: America’s overlooked epidemic

Many Americans struggle with addiction. As experts work to address everything from opioid to alcohol abuse, many say a much-needed element is empathy, which squelches shame and encourages social connections.

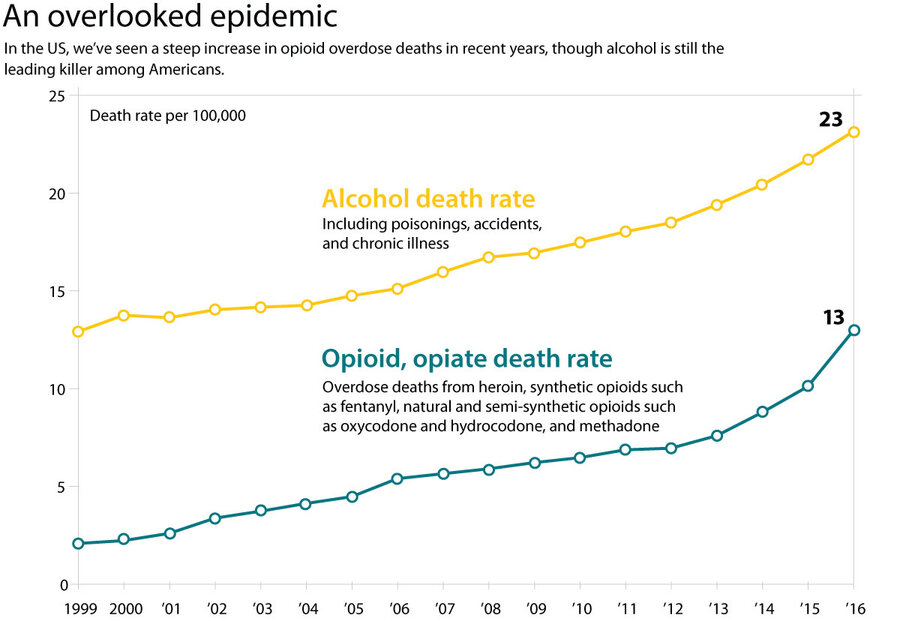

In the United States, we’ve seen a steep increase in opioid overdose deaths in recent years. More than 42,000 Americans died in 2016 from taking opioids. Last year, the Trump administration declared a national public health emergency and unveiled a five-point plan to tackle the epidemic. But if you had to guess, what drug would you say is killing the most Americans each year, totaling more than 88,000 deaths in 2016? It’s alcohol. Yes, the opioid epidemic has surged and deserves attention. But among American youths in particular, alcohol remains the primary substance abused. Addressing that use is seen as primary prevention for any drug addiction later in life. Amanda Decker, a substance use prevention specialist in Avon, Mass., says parents, teachers, and administrators are now asking her about about opioids. “They’ll notice we’re talking about tobacco, alcohol, and marijuana. … [W]e don’t talk about heroin [or opioids], but it’s because that’s not what kids are using. That’s hard for some people to believe,” says the coordinator for the Avon Coalition for Every Student. “I kind of say to people we have an addiction epidemic in our country, not an opiate epidemic. It's addiction in general. And that's been that way for years.”

US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Dissecting a hurricane: What makes a superstorm?

For centuries, hurricanes have been viewed as chaotic forces of nature. This story looks at the valuable insight we're gaining about cyclones courtesy of daring pilots and advancing technology.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Days before hurricane Michael made landfall near Mexico Beach, Fla., in October, the National Hurricane Center predicted a remarkably accurate path, highlighting just how far scientists’ understanding of the storms has come. But Michael’s intensity still caught many Floridians by surprise, as it ramped up from a Category 2 to nearly a Category 5 monster in less than 24 hours. The Atlantic hurricane season officially ended on Nov. 30, but scientists find ways to study these storms year-round. Determined to figure out how to better predict the kind of rapid intensity change that was seen with Michael, one researcher has built a “hurricane in a box” in his laboratory on Virginia Key in Miami, Fla. With the touch of a button, University of Miami professor Brian Haus can turn a calm ocean scene in the 75-foot-long tank into a roiling Category 5 hurricane, complete with wind speeds topping 200 miles per hour and powerful waves. Living in Miami, “you really see the impact of trying to get better answers,” says Professor Haus. “If we got hit really badly, everything we know could be completely changed. And that makes you really want to try to understand this better.”

Dissecting a hurricane: What makes a superstorm?

The first time a pilot intentionally flew an airplane into a cyclone, it was to settle a bet. When he emerged triumphant, he had not only proven that that the training airplanes used during World War II could survive the intensity of hurricane force winds; he had sparked an idea.

What if scientists could study a cyclone from the inside out? In the ensuing seven decades, hurricane research has taken off far beyond the dreams of those first storm chasers.

The Air Force Reserve now has a squadron dedicated to the daring trips, satellites snap spectacular images from aloft, and sensors on planes, ships, and satellites give forecasters the information they need to model a storm’s path.

That ongoing scientific investigation has fundamentally changed how we view hurricanes. The storms used to be seen as an inexplicable, destructive force of nature or an act of the gods. But now, we’ve begun to see hurricanes as something we can understand and predict.

Today meteorologists can forecast a hurricane’s track, wind speeds, rainfall, storm surge, and other details days in advance of landfall. “What we do now at five days [out], we dreamed of doing 20 years ago at two days,” says Ken Graham, director of the NOAA National Hurricane Center in Miami, Fla.

But there are still gaps in our knowledge of the details of hurricanes. And those nuances could prove crucial to making even more reliable forecasts. So even though the Atlantic hurricane season officially ended on Nov. 30., researchers find ways to study the storms year-round.

The making of a superstorm

One big question that still eludes hurricane scientists is how a hurricane goes from a disorganized tropical storm to a Category 5 monster overnight.

Such rapid intensity change was on clear display during hurricane Michael in October. The storm followed the path predicted by the National Hurricane Center several days ahead of landfall but caught people by surprise when, right before making landfall, the storm ramped up from a Category 2 to nearly a Category 5 storm in less than 24 hours.

Scientists have the big picture idea of the ingredients necessary for an intense hurricane. Warm ocean water, moist air, and consistent atmospheric winds all feed monster storms. And the opposite conditions can suck energy out.

But meteorologists’ models of rapid intensity change don’t always match the evolution of real storms. In the standard models, says Brian Haus, a professor in the ocean sciences department at the University of Miami’s Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science, “there’s just not enough energy getting up into the storm.”

Scientists think the gap in their understanding is strongly tied to what they still haven’t been able to see well: what happens where the atmosphere and the sea meet.

Planes can capture data from within the clouds, and satellites have revolutionized our view of the structure of the storms from above, but the air-sea interactions below are still difficult to observe. Ending up in the right place at the right time in the vast ocean with a ship or a buoy is tricky, and objects bobbing around in a hurricane are easily destroyed.

That’s why Professor Haus built a “hurricane in a box” in his laboratory in Miami. Inside the 75-foot-long clear box, water siphoned from nearby Biscayne Bay sloshes against a makeshift metal shoreline. With the press of a button, Haus can turn the calm ocean scene into a roiling Category 5 hurricane, complete with wind speeds topping 200 miles per hour and powerful waves. Sensors and cameras cover the hurricane simulator to capture the details.

Haus thinks something seemingly small may add a lot of fuel to ramp up a hurricane’s intensity rapidly: sea spray. The tiny water particles kicked up by breaking waves could be key, he says. Some research suggests that incorporating sea spray into models might yield better rainfall predictions.

The idea is that dramatic hurricane waves kick up a lot of sea spray, and those water droplets could be evaporating and rising up into the roiling clouds above. That water vapor can inject into the heart of the storm two of the three major intensification ingredients: moisture and heat. Using the hurricane simulator, Haus is taking a closer look at the characteristics of those water droplets flying through the air.

But a human-made hurricane isn’t the same thing as a real hurricane. Researchers are still trying to pierce the haze around real-life air-sea interactions during a hurricane by deploying more and better buoys and other tools during hurricane season.

Across the street from Haus’s laboratory on Virginia Key in Miami, at NOAA’s Hurricane Research Division, scientists and engineers are developing mechanical envoys to study the characteristics of the top of the ocean. One is a remotely operated vehicle, dubbed a glider, which looks a bit like a sleek narwhal. The gliders explore the top half mile of seawater for up to a month at a time, dipping down to various depths to take temperature, salinity, and other measurements before and during a hurricane.

Warmer water provides energy for a hurricane, while colder water draws energy from the storm, explains Ricardo Domingues, an oceanographer working on the gliders, which were first deployed in 2014.

“The key is to know how much heat is stored in the upper part of the water column,” he says, and if there are layers of colder water not far below. Turbulence from a hurricane overhead can bring that cold water up from the depths and weaken the storm. But the saltiness of seawater can act as a barrier to that mixing, he adds, so that is also crucial data to input into intensity predictions.

The human factor

Scientists aren’t the only ones who see hurricanes as much more knowable than in decades past. In hurricane country, the general public doesn’t simply rely on weather forecasts. Many residents pore over data and models put out by meteorologists about developing hurricanes and share satellite images of the storms on social media. More than 1.3 million people follow the National Hurricane Center’s Facebook page, and in Miami during hurricane season, Haus says, people can be overheard talking about the models – not just the storms – on the bus on the way to work.

But there’s still work to be done to make sure public perceptions of the risk of developing hurricanes are accurate, says the National Hurricane Center’s Mr. Graham.

“We’re not going to rest in trying to make the science better,” he says, “but the communication part of this is big. How do you communicate the risk so that people take the actions needed to save their lives?”

One challenge is that people’s perceptions of the risk of a hurricane often rely on their past experiences, explains Julie Demuth, a researcher at the National Center for Atmospheric Research studying risk perception. And, she says, “the devil’s in the details.” For example, if people decided to stay put during a Category 3 hurricane and saw no damage, they might think they can ride out future storms just as safely. But storms vary, from neighborhood to neighborhood – and from hurricane to hurricane.

“Hurricanes are like people. Every one is different,” says Frank Marks, director of NOAA's Hurricane Research Division. And as a result, he says, the current categorization process can be misleading. A Category 1 storm can cause a massively devastating storm surge when it makes landfall if it passes over shallow enough bodies of water. That's what happened when hurricane Florence hit North Carolina in September. Though it had approached the coast as a Category 4 storm, by the time it made landfall it had weakened to a Category 1 but still brought record-breaking storm surge.

“We need to change the narrative,” Graham says. “We need to really focus on those impacts independent of the category.” And that’s just what the National Hurricane Center is doing. For the past two years, for example, NHC has issued storm surge forecasts separate from hurricane forecasts.

For hurricane scientists and forecasters, getting it right is personal. Many live in hurricane-prone areas like Miami.

“You really see the impact of trying to get better answers,” Haus says. “If we got hit really badly, everything we know could be completely changed. And that makes you really want to try to understand this better.”

Forecasters also feel a sense of responsibility, Graham says: “The goal here is to protect lives.”

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Bush as the necessary model of a public servant

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

If a common thread can be found in the tributes for George H.W. Bush, it is his role in elevating the dignity of public service. Or as Mr. Bush simply called it, “pitching in.” From war hero to congressman to CIA director to diplomat to vice president and president, he was a model of that honorable profession known as career government worker. Since 2000, his foundation has given awards to world leaders for “excellence in public service.” Last year he assembled other living former presidents to join in fundraising for aid relief after hurricane Harvey. Bush saw politics – despite its worst aspects – as a means for public service, not as a vehicle for money, fame, or personal power. At root, service to others is a reflection of a higher good. That good can best be seen in the civic virtues of exemplary public servants. In his tribute, President Barack Obama said the late president’s life “is a testament to the notion that public service is a noble, joyous calling.” In an era of high distrust of government and a decline in volunteering among Americans, his record should be a reminder of the need for more people to help citizens and communities with practical skills and selfless humility.

Bush as the necessary model of a public servant

If a common thread can be found in the tributes for George H.W. Bush, it is his role in elevating the dignity of public service. Policy leadership, such as the late president’s guiding hand at the end of the cold war, was almost secondary to what is termed today “servant leadership.”

Or as Mr. Bush simply called it, “pitching in.”

From war hero to congressman to CIA director to diplomat to vice president and president, he was a model of that honorable profession known as career government worker. Even in his passing, Americans were reminded about being of service to others in the photo of Sully, his service dog in later years, lying beside his coffin.

Bush chose Texas A&M University, in College Station, as the site of his presidential library in part because of its school in public administration. Since 2000, his foundation has given awards to world leaders for “excellence in public service.” Last year he assembled other living former presidents to join in fundraising for aid relief after hurricane Harvey. He also left behind a legacy of two sons with their own records as high elected officials.

Bush saw politics – despite its worst aspects – as a means for public service, not as a vehicle for money, fame, or personal power. Perhaps he was inspired by a father who volunteered to run town meetings in their community. In his tribute, President Barack Obama said the late president’s life “is a testament to the notion that public service is a noble, joyous calling.” Or as Bush himself said in 1992, “I saw a chance to help and I did.”

In an era of high distrust of government and a decline in volunteering among Americans, his record should be a reminder of the need for more people to help citizens and communities with practical skills and selfless humility. In 2017, Congress was so worried about the state of the nation’s civic health that it set up a panel called the National Commission on Military, National, and Public Service. Its 11 members are crisscrossing the United States looking for ways to inspire young people to serve the country in some way. Its recommendations are due in 2020.

In October, another notable civil servant, Paul Volcker, former chairman of the Federal Reserve, came out with a memoir, “Keeping at It: The Quest for Sound Money and Good Government.” In it he writes, “One cannot sit here in 2018 without a strong sense of concern about ... the state of public service.” He has formed a nonpartisan think tank, the Volcker Alliance, aimed at strengthening professional education for public service.

But not all is bleak. In a survey of 1,000 “rising government leaders” released earlier this year, the Volcker Alliance found about 75 percent report they intend to continue in government for the long term and that they work among trusted peers. More than 80 percent said their work requires “fostering a culture of responsive service to the public.”

At root, service to others is a reflection of a higher good. That good can best be seen in the civic virtues of exemplary public servants. Bush senior was certainly one of those. But as his wife, Barbara, might have reminded him, it is better to inspire others to such a calling than call attention to one’s own deeds.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

No longer ‘starved for reality’

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 4 Min. )

-

By Laura Lapointe

The temptation to spend time on our devices seems constant, but today’s contributor shares how she learned to be better balanced by considering what is truly satisfying and fulfilling.

No longer ‘starved for reality’

There they were again: the shoes, marching across the top of my screen in an ad on the site where I was doing some Bible research. These were the same shoes I had clicked on while scrolling through a social media site. I had actually ordered the shoes and returned them because they didn’t fit.

It was exasperating to feel that I couldn’t hide from this ubiquitous temptation to click away from where I had intended to keep my focus.

A month or so later I was listening to an episode of the TED Radio Hour on NPR about the seemingly relentless distraction of our various devices and their screens. After listing a number of ways in which social media and marketing companies attempt to keep us engaged with our devices, the speaker, Jaron Lanier, said that he didn’t feel these things were really what people found stimulating. Then he made the point, “I think that the more accurate description of modern times is that we’re starved for reality.”

Mr. Lanier’s thought-provoking statement, what one might consider an honest appeal for more substance in human life, resonated with me. Sometimes it seems that the influence of materialism touches every aspect of our lives. The internet, for example, while useful in many different ways, can also be used as an outlet to over-indulge, such as by spending too much time on online shopping!

So we need to find the right balance. No matter what form it takes, the attempt to satisfy our desires through material means leaves us feeling separated from goodness and joy – from the spiritual mindedness that the apostle Paul described as “life and peace” (Romans 8:6).

In Christian Science, “reality” is a word used to describe not just the current actual state of things but the truth of creation as the spiritual emanation of a creator who is Love itself, a creation that includes you and me. Because God, whom the Scriptures refer to as Spirit, creates only that which is spiritual, each of us is actually an idea of Spirit. Referring to this creator, the Bible says, “When you open your hand, you satisfy the hunger and thirst of every living thing” (Psalms 145:16, New Living Translation).

God is constantly supplying His ideas with spiritual inspiration. In spite of that, to consistently experience God satisfying “the hunger and thirst” we feel for spiritual reality in a material world requires persistence, prayer, and a devotion to being spiritually minded. It means being watchful about the thoughts we entertain, and rejecting those that aren’t coming to us from God, good.

Having found myself lured into spending too much time in online window-shopping, I increasingly recognized it was leaving me feeling unsatisfied and unfulfilled. Just as those shoes I ordered had been too small, the definition of myself as a profile defined by web marketing no longer fit. I realized that nothing but discovering more of what is truly real – God’s spiritual creation – would bring satisfaction to my days. Learning more about spiritual reality, I saw how fulfilling it was to express spiritual qualities such as goodness and love by looking less inward and caring more for others.

Mary Baker Eddy, the founder of The Christian Science Monitor, writes: “The infinite will not be buried in the finite; the true thought escapes from the inward to the outward, and this is the only right activity, that whereby we reach our higher nature” (“The First Church of Christ, Scientist, and Miscellany,” p. 159). The teachings of Christian Science point to the example of Christ Jesus, who showed the naturalness and joy of living entirely for others rather than being caught up in self-centered thoughts and actions. He proved that the best way to be conscious of God’s reality is to base one’s life on a love for God and man.

When I’ve struggled with feelings that can pull me into a spiral of unproductive thinking, I have gained much strength in looking to the example of Jesus and better understanding, and striving to live on, the basis of what Christian Science teaches. It reveals each of us as Christlike, naturally inclined to express the same qualities that Jesus lived.

Through seeking divine strength and lasting satisfaction, I have found release from browsing habits that drag me away from what feels most authentic and purposeful. We are all designed for a much greater purpose than being “buried in the finite,” and we all have a right to escape that limited focus and enjoy activities – online and off-line – that open our thought to living more loving lives and satisfy our natural desire for reality.

A message of love

‘Yellow Jackets’ swarm Paris

A look ahead

Thanks for starting your week with us. Tomorrow we’ll take you to North Dakota, where there’s a raging debate over wind power and a question: Do rural Americans have a right to an uncluttered view?