- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- ‘Taken hostage’: the ethics of the US government shutdown

- Farmers have a beef with plant- or lab-grown meat. Should you care?

- Low on gas, high on hope, Mexicans back leader’s war on fuel thieves

- What really happens behind bars? Insiders make videos to show you.

- In ticking of ‘The Clock,’ a parallel to Brexit’s relentless grind

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

When the good news on the bad news is the pushback

Reading the releases of the organization Human Rights Watch is like scanning a police blotter of the world’s toughest neighborhoods.

Consider these from overnight: protests quashed in Sudan, asylum-seekers detained in Libya, garment workers’ rights again trampled in Pakistan.

It’s not as though you couldn’t also find small embers of optimism and amazement to fan this week – a week in which US leaders got coldly personal and punitive as federal workers languished (more on that in a minute).

There were feats of perseverance. A woman named Dhanya Sanal summited a 6,100-foot mountain in India’s Kerala state that had been restricted, by custom, to men. British ultrarunner Jasmin Paris crushed a 268-mile course in the Scottish borderlands in about 83 hours, beating a mixed-gender field (and stopping to express breast milk).

Even more notable, perhaps: That dire drumbeat from Human Rights Watch also held a surprise burst of promise yesterday. Amid all the crises, the organization chose to cite as the year’s most important trend the rising global pushback against authoritarians.

Yes, autocrats seek to impose the worst form of human hierarchy, using oppression to advance false forms of populism. But “[t]he same populists who spread hatred and intolerance are fueling a resistance that keeps winning battles,” said agency director Kenneth Roth. “Important battles are being won, re-energizing the global defense of human rights.”

Now to our five stories for your Friday, including ones from where the arts intersect with prison life and with Brexit politics.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

‘Taken hostage’: the ethics of the US government shutdown

Compelling people to work without pay is fast becoming more than a legal issue for the federal government. Viewed as a social compact, it raises serious ethical questions too.

It’s a foundation of economic life going back at least to Bible times: When employer and employee agree on a wage, they stick to it. And US federal law says employers have to pay for work performed. So how come many federal employees have to work without pay? It’s a countervailing tradition that says vital federal workers must stay on the job even when there’s no money to pay them. Workers are battling back with lawsuits that some legal scholars believe have merit. While the Trump administration is trying to force more federal workers back to work, pressure to pay them is building. On Thursday, some 18,000 federal workers petitioned to end the shutdown. Also, California Gov. Gavin Newsom told airport-security workers he thinks his state can allow working federal employees to receive unemployment benefits. The parties may disagree over priorities and the size of the government, but a shutdown isn’t a practical way to solve that, says University of Illinois law professor Michael LeRoy. “We should all strive to find better solutions than throwing people out of work.”

‘Taken hostage’: the ethics of the US government shutdown

Hector Dias, one of some 400,000 federal employees who are being asked to work without pay, has a blunt message about the government’s partial shutdown.

“We should not be taken hostage of the political atmosphere,” says Mr. Dias, a Department of Transportation worker in Washington, echoing the concerns of legions of employees deemed too essential to be furloughed. “It’s no fair that we are going through this.”

It’s one thing to miss a paycheck or maybe two. But with each new week in what’s become the longest US-government shutdown, an ethical and legal question has been moving steadily toward the forefront: Is it fair or lawful for government employees to be told to keep working while they are not being paid?

A foundation of economic life, going back at least as far as the biblical parable of the vineyard laborers, is the idea of employer and employee agreeing on a wage and sticking to it. The obligation of employers to pay for work performed is enshrined in federal law, but now it’s running up against a countervailing tradition that calls on vital federal workers to stay on the job even when there’s no money to pay them.

Federal workers faced a setback this week when a US district judge refused to order an immediate resumption of paychecks. But lawsuits on behalf of workers will move forward, and the stakes of the shutdown could rise for both the workers and the American public the longer the political impasse goes on.

Some legal scholars believe the workers have a strong case.

“These lawsuits look to be valid,” says Michael LeRoy, a University of Illinois law professor who focuses on employment matters. “The immediate issue is compliance with the Fair Labor Standards Act. That's a law that all of us recognize – in fact if not in name – as our minimum-wage, overtime, and time-records law. It applies to the federal government.”

So why is this even coming up?

Justification for work without pay

First, of course, is the funding impasse. Portions of the government have been funded by Congress, but others haven’t, as congressional Republicans and Democrats dig in on opposing sides over President Trump’s demand that any new plan to fund the government include at least $5.7 billion for new steel barriers against illegal immigration on the southern border.

But the next part of the story is where the work without pay comes in. Such an impasse results in a shutdown of federal operations, with employees told not to come to work because there’s no money to pay them. Yet the same law that guides such a shutdown, the Antideficiency Act first enacted in the late 1800s, also provides a potentially large exemption from the rule.

Federal workers can be “excepted” in cases of emergency involving the safety of human life or the protection of property. So far in the current shutdown, that has included most workers for the Coast Guard, the FBI, and air-traffic controllers at the Department of Transportation.

With Mr. Trump facing the risk of a public backlash the more key government services are curtailed, his administration has been seeking to reduce the hardship imposed on average Americans. The result is some widening in the definitions of who can be excepted. The Trump administration hopes the pool will include Agriculture Department workers who help farmers get loans and Internal Revenue Service staff who help taxpayers get refunds.

Backlash is building

On Thursday, the National Treasury Employees Union, which represents IRS workers among others, delivered to Senate leadership a petition signed by 17,820 federal employees calling for an end to the shutdown.

“NTEU is also challenging the administration’s ability to require employees to work during the shutdown even if their jobs are not related to protecting human life and property,” it said in announcing the petition Thursday.

While awaiting a resolution, one thing the affected workers can’t do is go on strike (illegal for federal employees).

And a Labor Department official, citing guidance the department gave in a 2013 shutdown, has also ruled out unemployment benefits in general for those who are working without pay. But on Thursday, California Gov. Gavin Newsom defied that view, telling airport-security workers he sees legal footing for his state to allow the benefits. (Federal employees not working due to the shutdown already can file for unemployment.)

“We should be reciprocated for our time and efforts” during the shutdown, says one Department of Justice employee who says she can rely on savings for now but may seek forbearance from creditors if the period of unpaid work persists.

Once a shutdown ends, back pay should start flowing promptly. But workers “may not be able to repair their lives so easily at that point,” says Ruben Garcia, co-director of the workplace law program at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas.

Damages, too?

There’s precedent as recently as 2013 for workers to receive not only their back pay but also to win damages in court to compensate for the delay they experienced.

“It's a sound claim that the federal workers have,” Professor Garcia says, although he adds that the gears of the justice system can grind slowly.

Added to the mix, for now at least, is the desire of the judicial branch to avoid any appearance of putting its thumb on the scale of a dispute involving the two other branches of the federal government.

“The judiciary is not ... leverage in the internal struggle between the branches of government,” District Judge Richard Leon said Tuesday in Washington. He said that to grant the request of the NTEU and other federal employees would “create chaos and confusion.”

So far, the shutdown and its effects have drawn a mixed response from the public. Many Americans voice sympathy for the affected workers and support for those in Congress who are seeking bipartisan steps to fund the government. Another sizable chunk of the electorate shows solidarity with Trump’s insistence on fresh steps for border security, or even for the view that the shutdown itself may strike a blow for the conservative cause of smaller government.

“We already see conflicting views,” says Professor LeRoy in Illinois. “We do have federal workers literally marching and protesting. On the other side we have some people [in the private sector] saying ‘Welcome to my world. I got laid off.’ ”

Spreading impact

One irony, he says, is that the longer the shutdown runs, the more unfairness may also spread to include every taxpayer. Average Americans will be paying out money to the US Treasury – through paycheck withholding – without getting back the full services they’re paying for.

Other inefficiencies of the shutdown process would also take their toll. Once a shutdown ends, taxpayers could be on the hook for damages to the “essential” workers and to provide back pay to furloughed employees who weren’t working. They’ll also have to cover the costs of operational hiccups as shuttered agencies reopen.

The two political parties may have legitimate disagreements over the focus and size of the government, but finance experts widely agree that a shutdown isn’t a practical way to resolve those. It neither cuts costs nor restructures federal bureaucracies. And for now it’s taking a human toll in the form of unexpected furloughs or unpaid work.

“We should all strive to find better solutions than throwing people out of work,” LeRoy says.

Farmers have a beef with plant- or lab-grown meat. Should you care?

How we speak says a lot about how we think – and can influence how we spend. Consider a rancher-led battle over food labels. Is ‘plant-based meat’ an oxymoron or cutting-edge Earth-friendly cuisine?

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Ever since the dairy industry won limits on margarine a century ago, new food technologies have had to battle over what they’ll be labeled. The big contest today is over the word “meat.” It’s revving up as farmers seek to defend their market against alternative proteins. One threat is genetic technology that’s allowing start-up companies to mimic red meat and poultry in a lab without all the time and trouble of raising cows, pigs, and chickens. Missouri last year passed a law defining “meat” as “any edible portion of livestock or poultry carcass or part thereof.” Nebraska may be up next, but ultimately a federal rule is expected to preempt state laws. All this comes with high stakes for the environment. Farming and ranching already account for up to 30 percent of global greenhouse-gas emissions. “We want to solve what we think is probably the transcendent challenge of our generation,” says Todd Boyman of Hungry Planet, which makes plant-based foods. The goal, he says, is to “to give people the taste and the textures of what they love” but in a more sustainable way.

Farmers have a beef with plant- or lab-grown meat. Should you care?

It seems almost silly. Farmers and ranchers are pushing state legislatures to define “meat.”

Missouri last year became the first state to oblige, passing a law saying it was “any edible portion of livestock or poultry carcass or part thereof.” Nebraska may be up next, considering legislation with similar language, and efforts are also under way in Virginia. North Dakota, Wyoming, Tennessee, New Mexico, Colorado, and Indiana.

Why all the fuss? Money and fear. The conventional meat industry is worried that as competitors mimic the taste and texture of their products using vegetable proteins, they will cut into sales. Even more concerning: Start-up companies are mimicking their products in the lab, using genes to grow red meat and poultry without all the time and trouble of raising cows, pigs, and chickens.

Such competition, comprising only about 1 percent of the meat industry, is growing fast. And it comes at an especially sensitive time, because the conventional industry is under attack for its detrimental impact on the environment, from greenhouse gases to water use. This week, a huge study published in The Lancet, a British medical journal, called for a radical transformation in agricultural production and diets, including more than halving the world’s intake of red meat.

If the plant-based and cell-based companies can show that their products avoid these environmental costs, they may well steal away customers, even perhaps overcoming the “Ewww” factor of eating meat produced in a lab.

A big part of these products’ consumer appeal will depend on what they’re called.

Take, for example, a sausage made with chicken produced from cells in a lab. “If I was required to call that chicken-flavored sausage with test-tube grown chicken cells, I'm not putting any of my money into the success of that product,” says Stuart Pape, chairman of the Food and Drug Administration practice at the law firm Polsinelli in Washington. “It's not an accident that some of the conventional-meat folks want the name not to be ‘cell-based’ or ‘cultured’ meat, but ‘lab-grown’ meat.”

The battle is already joined, no matter what the dictionary says. (Webster's New World College Dictionary leads with “the flesh of animals used as food,” supplanting the broader archaic definition “food.”)

“It is meat, but it’s just produced in a different way,” says Nicole Manu, a staff attorney with the Good Food Institute, a nonprofit advancing plant-based and cell-based meat. [Editor's note: This paragraph was corrected to make clear GFI's legal status.]

“Lab-grown fake meat products should not be permitted to use the term ‘beef’ and any associated nomenclature,” Danielle Beck, senior director of government affairs for the National Cattlemen’s Beef Association, counters in a statement to the Monitor. “NCBA is committed to protecting consumers and preserving an even playing field for real beef products.”

At the end of this month, the group will hold its annual convention in New Orleans and further refine its strategy for what it calls a top priority.

It’s happened before

Ever since the dairy industry defended butter by imposing limits on margarine a century ago, new food technologies have had to battle over what they’ll be labeled. In the late 20th century, genetically modified crops faced fierce opposition from environmental and other groups that wanted them labeled as such. For 20 years, the dairy industry has been fighting to convince regulators to force soy, rice, almond, and other producers to stop calling their liquid beverages milk.

Last month, the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals ruled in favor of Blue Diamond Growers, saying a reasonable consumer would not expect the company’s almond milk to be nutritionally equal to milk. Still, the Food and Drug Administration is looking into the matter, with Jan. 25 the deadline for comments before it rules.

In the case of meat, the US Department of Agriculture will determine, with FDA input, what the meat alternatives will be called. Its decision will preempt the state laws now being considered.

The substitute meat companies have an incentive to show that they’re different from conventional meat so they can win over customers, Mr. Pape says.

Convergence of palate and planet

“We formulated this because we want to solve what we think is probably the transcendent challenge of our generation,” says Todd Boyman, co-founder of St. Louis-based Hungry Planet, which makes products trademarked Match Meats. “And that is: How do you bend the curve on human and planetary health? And the way that you're going to do that is to give people the taste and the textures of what they love and what is absolutely a craveable food. But we're going to do it in a much more responsible way.”

That’s the point that the Lancet study makes, which reflects earlier research: Farming and ranching already use about 40 percent of the world’s land and 70 percent of its fresh water, and they are responsible for up to 30 percent of global greenhouse-gas emissions. With the world population reaching about 10 billion people by 2050, expecting to feed them a Western-style diet will stretch and perhaps exceed the world’s food-growing capacity.

“Because much of the world’s population is inadequately nourished and many environmental systems and processes are pushed beyond safe boundaries by food production, a global transformation of the food system is urgently needed,” the report says.

A view from rolling grasslands

But the idea that the solution is replacing livestock with vegetables, fruits, and other healthy foods is too simplistic, argues Nicolette Hahn Niman, an environmental attorney, rancher, vegetarian, and author of “Defending Beef: The Case for Sustainable Meat Production.” Much of the pastureland that grazing animals use can’t be used for growing crops, anyway. So taking beef and other grazing animals out of production simply decreases the food supply.

The key transformation is to move from grain-fed to grass-fed livestock, she says. That would allow the millions of acres of corn and soybeans to go to create plant-based foods rather than feeding animals. Indeed, evidence is accumulating that allowing livestock to graze pastureland actually improves soil health.

“It’s not the cow,” Ms. Niman says. “It’s the how.”

The American Grassfed Association, which advocates for grass-feeding farmers and ranchers, hasn’t yet taken a position on cell-based meat. But President Will Harris, who is awaiting test results that should show his farm is carbon neutral or near carbon neutral, is adamant about plant-based meat companies labeling their product.

“I would go to war to defend their right to enter the marketplace,” he says. But “the fact is meat is animal protein and I don't see how you can call nonanimal protein ‘meat.’ ... ‘Plant-based protein’ is fine.”

Low on gas, high on hope, Mexicans back leader’s war on fuel thieves

Politicians’ vows to fight corruption, crime, and impunity are usually crowd-pleasers. But when the campaign runs into real-life complications, what price is the public prepared to pay?

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Mexico’s new president, Andrés Manuel López Obrador, begins most mornings with an hour-long press conference, peppered with his trademark folksy turns of phrase. And lately, lots of those talks have dealt with gas. Fuel has long been a hot-button issue here, and illegal tapping of state-owned gas pipelines cost Mexico roughly $3 billion in 2017. AMLO, as the president is known, entered office vowing to battle corruption and impunity. But his campaign against fuel theft, which has closed down key pipelines and brought on major fuel distribution problems in many regions, has left people with hours-long waits at the pump. Yet AMLO’s approval ratings have actually increased, and a vast majority support his gas campaign, according to a poll by a Mexican daily. Some observers say it’s AMLO’s accessibility – like those hour-long talks – that leaves many Mexicans willing to wait out the challenges. But the campaign also melds central themes AMLO underscored in his historic presidential victory: an end to fraud and impunity, working to help the “everyman,” and a more secure and safer Mexico.

Low on gas, high on hope, Mexicans back leader’s war on fuel thieves

Editor’s note: In news that broke after this story was published, more than 60 people are reported dead and more are missing or injured in a fuel-pipeline explosion Jan. 18 in the town of Tlahuelilpan, in the state of Hidalgo north of Mexico City. Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador has pledged to investigate the incident, which is initially being attributed to an illegal pipeline tap. “I believe in the people, I trust in the people, and I know that with these painful, lamentable lessons, the people will also distance themselves from these practices,” he said according to an Associated Press report.

Vittoria Romero and her daughter Celia were celebrating with high-fives and big smiles on a bright but chilly morning this week: They’d successfully filled their compact car’s gas tank after less than 30 minutes in line.

Across Mexico, people like the Romeros have been contending with hours-long bumper-to-bumper waits at the pumps, reduced bus transportation, and other daily inconveniences for the past two weeks. The fuel distribution problems began after President Andrés Manuel López Obrador ordered the closure of key pipelines in late December in an effort to curtail rampant fuel theft. Illegal taps in state-owned pipelines cost Mexico roughly $3 billion in 2017. Between January and November last year an estimated 65,000 barrels of fuel were stolen per day, according to the state-owned petroleum company, Pemex.

Gas has long been a hot-button issue here, from its nationalization in 1938 to a price hike in 2017 that led to weeks-long, sometimes violent protests. But despite plenty of grumbling over the daily effects of the pipeline cuts and distribution challenges, AMLO, as the president is often called, has maintained widespread support. According to a Monday poll published in the Mexican daily El Financiero, 89 percent support the president’s offensive against fuel theft. His overall approval ratings have even increased slightly, to roughly 76 percent support.

Amid so much frustration, support for the president comes down to a sense of hopefulness – well-founded or not – that Mr. López Obrador is making tangible changes for good. Unlike previous leaders, López Obrador is governing in a way that’s more visible to the public. Fuel shortages have consistently headlined his daily, livestreamed press conferences. The fight against theft in many ways melds central themes AMLO underscored in his historic presidential victory: an end to fraud and impunity, working to help the “everyman,” and a more secure and safer Mexico. Fraud and impunity have gone essentially unimpeded for decades, and many reason that dealing with gas shortages is worth it – to an extent.

“I’ve waited for close to two hours before,” says the younger Ms. Romero, a masseuse who relies on her mother’s car to get to many of her clients. “It’s a pain, and I hope it doesn’t go on much longer. But, at the end of the day, it’s worth it if it’s for the good of the country.”

A present president

López Obrador spends roughly an hour every weekday morning speaking to reporters and the public in press conferences that stream online. His announcements often come off as unplanned or off the cuff, peppered with trademark folksy turns of phrase. And although he frequently skirts questions (Mexican magazine Nexos tracked how often he responded in December, putting it at about 71 percent of time), his public presence is a 180-degree turn from his predecessor, Enrique Peña Nieto, who rarely took questions from the press and led at arm’s length.

“When you’re not out there talking to the press and not talking to the public, you’re simply not there. That’s what happened with Peña Nieto; he was an absent president,” says Alejandro Schtulmann, president and head of research at the Emerging Markets Political Risk Analysis consulting firm in Mexico City. He thinks support continues for AMLO despite the daily impact of the fuel cuts because he’s governing out loud and so publicly compared with past leaders.

“López Obrador is a really good communicator. He may lie or not actually give any information when he answers a question, but at least he’s there. And people believe by being present he’s there for them,” Mr. Schtulmann says.

Rosa Diana, a housekeeper in Mexico City, says she’s had to wait longer for the bus in the morning since fewer appear to be running the past few weeks. She voted for AMLO, but is growing frustrated with her commute and the lack of concrete plans for fuel distribution.

“I think people are supporting AMLO through it all because they think he’s going to increase benefits,” she says, referring to his promises to boost pensions for the elderly and scholarships for impoverished youth, among other social programs. “They don’t like what the gas situation has done in their daily lives, but they are willing to be patient because they think he will help them in other ways.”

Unmapped road

More than 5,000 security officials have been deployed to protect the most important pipelines this month. While lines are closed, fuel is moved by tankers, a slower – and costly – form of transportation, contributing to shortages in parts of the country.

Oil theft is a real challenge that few leaders have tried to tackle in the past. Illegally tapping pipelines is carried out not only by transnational criminal groups, but also by communities near pipelines which rely on black-market oil income to stay afloat. Government employees, private security, and Pemex officials have also been implicated in oil-theft-related corruption.

Although ending fuel theft is important, analysts worry that there isn’t an actual plan other than these short-term cuts. “The purpose of the policy is not really clear,” says Schtulmann, adding that tankers aren’t a long-term solution and fully guarding hundreds of miles of pipelines isn’t realistic. “Eventually we’ll return to the pipelines, so it’s unclear what [the president] is doing that is going to be different.”

Others are more optimistic.

“It will be difficult to say ‘the problem has been eradicated,’ but I foresee small yet important steps coming out of this, like reclaiming government territory from criminal networks and exposing corrupt officials,” says Pedro Isnardo de la Cruz, a political scientist and expert on security at the National Autonomous University of Mexico. The government’s announcement Monday that three top Pemex officials will be tried for fuel theft is promising, he says. More than 1,500 other individual investigations are under way, according to the attorney general’s office.

“Fighting corruption is symbolic, and [López Obrador] wins big points with his words and actions around it,” says Mr. Isnardo. “In the short term he’ll continue getting a lot of support for this fight,” but if the economy starts to take a big hit or the peso falls, support could falter. He thinks this could go on for a few more months without AMLO taking a big hit.

“Right now, he has almost unconditional support.”

What really happens behind bars? Insiders make videos to show you.

The emotional process through which people behind bars must work isn’t a narrative that can accurately be told through outsiders’ depictions. This piece, from a publishing partner, goes much deeper.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

-

By Lauren Lee White Juvenile Justice Information Exchange

Each weekday morning at San Quentin State Prison, a group of men reports to the media lab and spends the day working on video projects until midafternoon. The participants are self-taught, relying on a library of film classics to help them. Their work, part of a tradition of media and arts initiatives in prisons nationwide, offers an opportunity for those involved to share what their lives are like in jail, and in some cases, to come to terms with the actions that brought them there. It gives voice to those who are incarcerated, something advocates say supports individual and community healing. Most of the films focus on one element of one man’s story – what it’s like to be an incarcerated parent, for example. Participants say their videos are meant to counter popular culture narratives that suggest that accountability isn’t a priority for them. “What we’re trying to do is … show we are responsible,” says Adnan Khan, who has been a part of FirstWatch since its inception in 2017. “We’re not denying our crimes, we’re not denying our actions, we’re not blaming people. We are understanding what we did and why we did it.”

What really happens behind bars? Insiders make videos to show you.

Against a vista of rolling hills and palm trees, a five-man film crew is setting up for a shoot. They white balance the cameras, adjust the tripods, play with composition. One man roams among them with a smaller camera, getting coverage of the shoot.

That’s not the only kind of coverage they need, though. Lt. Sam Robinson of the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR) watches over them, because they must be under the supervision, or “coverage,” of a corrections officer at all times. The men, members of a filmmaking program called FirstWatch, are incarcerated at San Quentin State Prison.

Their work, part of a tradition of media and arts initiatives in prisons nationwide, offers an opportunity for participants to share what their lives are like in jail, and in some cases, to come to terms with the actions that brought them there. It gives voice to those who are incarcerated, something advocates say supports individual and community healing.

“Film [is] what’s out there right now,” says FirstWatch participant Adnan Khan. “When it comes to incarcerated people and how incarceration is perceived … the source of information that most people get is from the news, the movies, from YouTube. We want to reclaim that narrative.”

Artmaking programs for incarcerated people have been around for decades. California’s Arts in Corrections program, for example, began in the 1970s and – having weathered budget cutbacks in the early 2000s – currently has a presence at every CDCR facility. San Quentin itself has offered filmmaking before, as featured in a 2009 Discovery Channel series titled “San Quentin Film School.”

FirstWatch began in January 2017. Participants report to the media lab each weekday morning and spend the day working on projects until midafternoon. Two of them, Lawrence Pela, 35, and Mr. Khan, 34, have been with FirstWatch from the start. Mr. Pela has served 11 years of a 46-year sentence, and Khan has served more than 15 of a 25-year-to-life sentence. Khan co-founded FirstWatch and, in October 2017, co-founded the Oakland-based nonprofit Re:store Justice with executive director Alexandra Mallick.

In contrast to those stories that highlight violence and racial tension in prisons, “We sit in conversations together about our lives, the things that we’ve done and how we should change,” Pela says. “We put ourselves in places where we’re willing to be vulnerable with each other, and that’s one thing you certainly don’t see in prison movies and shows. That happens so much here.”

Most of the films focus on one element of one man’s story: “Lumumba’s Prison Journey,” “Jeff’s Garden,” “Upu’s Story.” One of their most recent, and strongest, films is about San Quentin inmate Ralph Brown, who speaks about the pain of being an incarcerated father and missing huge parts of his son’s life.

The films run just a few minutes long, and the crew’s filmmaking skills undergo a striking evolution over time. The composition, editing, and sound design get tighter and more professional with each video posted on their site. The participants are self-taught, relying on a library of film school classics.

“We don’t have internet, we don’t have YouTube, and we don’t have a professional coming in here and teaching us,” Khan points out. “A lot of how I learn is just watching TV, watching movies and watching documentaries, literally counting how long each clip lasts.”

One FirstWatch film, titled “Accountability: Choy,” shows a man dramatically backlit, seated in a chair. Punctuated by long cuts to black, “Choy” tells the story of Doug, a man he killed, through the points of view of Doug’s family members. Watching it is something like participating in a virtual restorative justice circle, in which victims, families, those who are incarcerated, and other affected community members come together to discuss a crime and its aftermath.

“Restorative justice and FirstWatch are hand in hand,” Khan says. “Accountability is a huge piece when you come to these circle settings. So what we’re trying to do is fill that gap with these videos and show we are responsible. We’re not denying our crimes, we’re not denying our actions, we’re not blaming people. We are understanding what we did and why we did it.”

In addition to posting their work online, the FirstWatch crew is planning to work with CDCR’s Office of Victim Services to promote the accountability message through video. Mike Young, the manager of Victim Services, says, “This is one of the first times we’ve worked directly with a group of offenders, with the offenders being able to have a direct impact on the healing of the survivors.”

Better outcomes from arts participation

The benefits of formal, structured arts-in-corrections programs are well documented. Studies consistently show that participants have fewer disciplinary infractions in prison and are less likely to violate parole, reoffend, or return to prison once released, though the size of these reductions vary by study.

“In all cases where it was studied, arts programs [in prisons] reduced recidivism among people who had participated in the programs versus people who had not,” says Mandy Gardner, coauthor of the Prison Arts Resource Project, a comprehensive list of evidence-based studies looking at arts programs in US prisons and jails. Once released, she says, participants “became not only not negative parts of the community, but positive.”

Even for those with life sentences, she saw evidence of benefits to arts programs: Fewer violent crimes behind bars make the prison environment safer for officers and others who are incarcerated. And based on the volume of evidence that found increased confidence and communications skills among arts program participants, she says, “I would surmise that a program like FirstWatch would lead to better relationships with the people who are still on the outside,” such as friends and family members.

San Quentin’s media boom

San Quentin appears to take these benefits seriously. The prison is a hub of media-making. Its media center turns out a glossy magazine called Wall City, the San Quentin News, a closed-circuit news channel, the beloved podcast “Ear Hustle,” and FirstWatch.

The decision to have this kind of programming at the prison was at first based on common sense, Mr. Robinson says. “[San Quentin warden] Ron Davis and his predecessors saw that 90 percent of people incarcerated in California end up returning to their communities. How do you want a guy to return to the community? Do you want a guy who’s been locked away and whose only opportunity has been to hone his criminalistic skills?” he asks. “Giving a person hope and a new way of looking at things is the better course of action.”

Ms. Mallick, of Re:store Justice, plans to create a similar program at the California Institution for Women, roughly 50 miles east of Los Angeles, with the hope that LA’s nearby film community will provide equipment and expertise to the women there.

Even so, replicating San Quentin’s level of programming, particularly arts programming, at other facilities would be tough. The prison is in affluent Marin County, just outside San Francisco, with all its attendant wealth and resources – FirstWatch itself was funded with a single gift to Re:store Justice from an anonymous donor, along with in-kind donations of software, computers, and other film equipment. The Bay Area is a hotbed of criminal justice reform activity, an easy commute for activists and other reformers to come teach classes.

And, as the FirstWatch crew emphasizes, the climate in the prison allows for education and self-reflection. “We’re in a very unique place in San Quentin,” says Travis Westly, one of the newer members of FirstWatch. “Because of our environment, we can let our guard down. When you put people in an institution where you provide hope, you give them the ability to change themselves. And if you give someone the opportunity to change, you never know what the results may be.”

Update: Adnan Khan was freed on Jan. 18 at a resentencing hearing, according to Alexandra Mallick, after then-Gov. Jerry Brown commuted his sentence on Dec. 12 to 15 years to life.

This story was written for the Juvenile Justice Information Exchange, a national news site that covers the issue daily. A version of the story also appears on the JJIE site.

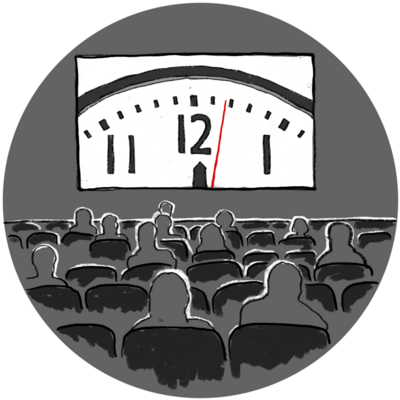

In ticking of ‘The Clock,’ a parallel to Brexit’s relentless grind

Whether you're observing from afar, reporting on it, or living it, Brexit can seem endless. The Monitor's Brexit reporter finds echoes of the experience in an exhibit not far from Westminster.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

Take the elevator to the second floor of the Tate Modern, a colossal art museum in a converted power station two miles downriver of the Houses of Parliament in London, and you will find the viewing room for “The Clock.” This 24-hour video montage eases you into a dreamscape that goes beyond normal cinematic escapism. Its creator, Christian Marclay, culled thousands of famous and obscure film clips for images of clocks – wristwatches, pocket watches, wall clocks, digital displays, sundials – that are edited to show the actual time, minute by minute, hour by hour. It’s cinematic time as real time. As a metaphor for Britain’s halting efforts to leave the European Union – will it, won’t it, didn’t we decide already? – “The Clock” is sublime. It’s the tick to Parliament’s tock, a “Groundhog Day” of temporal invention. Science fiction, spaghetti westerns, comic capers, murder mysteries, all spliced and synchronized into a compacted babel of genres and languages. Spend enough time watching “The Clock” and the loop is completed. There is no resolution. There is only past, present, and future.

In ticking of ‘The Clock,’ a parallel to Brexit’s relentless grind

This is my third reporting trip in three months to cover Brexit, the never-ending national drama over Britain’s vote to leave the European Union. Deadlines pass, politicians spar, autumn yields to winter. Nobody knows how or when it ends.

On each trip I find time to visit the Tate Modern, a colossal art museum in a converted power station two miles downriver of the Houses of Parliament, where Brexit is tied in political knots. The Tate Modern opened in 2000 and bills itself as the world’s most visited modern art museum. In 2016, it added a new 10-floor wing, a twisting lattice of inflected brick.

Take the elevator to the second floor and join the line to enter a dim, rectangular room of comfortable sofas. This is the viewing room for “The Clock,” a 24-hour video montage that in its audacity and simplicity eases you into a dreamscape that goes beyond normal cinematic escapism. It’s the most absorbing installation I’ve ever seen.

Its creator, Christian Marclay, culled thousands of famous and obscure film clips for images of clocks – wristwatches, pocket watches, wall clocks, digital displays, sundials – that are edited to show the actual time, minute by minute, hour by hour. It’s cinematic time as real time. No need to check your watch or phone: You’re watching an artistic timepiece.

As a metaphor for Britain’s halting efforts to leave the European Union – will it, won’t it, didn’t we decide already? – “The Clock” is sublime. It’s the tick to Parliament’s tock, a “Groundhog Day” of temporal invention. Science fiction, spaghetti westerns, comic capers, murder mysteries, all spliced and synchronized into a compacted babel of genres and languages.

You tell yourself it’s time to go. But as the hour approaches, the action speeds up. Bank robbers check their watches. Lovers on railway platforms dash past clocks. The narrative feels more urgent, the actors twitch and turn, and you wait for the release that follows.

Step outside under London’s gray skies and the Brexit impasse remains.

The Tate acquired “The Clock” in 2012 and it has been shown in art museums around the world. Since Mr. Marclay did not acquire the rights to the films he uses, “The Clock” is subject to the condition that museums do not charge to view it. That’s why it’s free to watch in London, one of the world’s priciest cities and a magnet for global capital and the ultra-rich.

After another hour spent with “The Clock,” I ride the elevator to the 10th floor to gaze at the spot-lit skyline across the river. The iconic dome of St. Paul’s Cathedral is almost lost amid the glass and metal towers of London’s financial district. New buildings are under construction, the pace of expansion seemingly unchecked by Brexit risk and political uncertainty.

A month earlier, I met a middle-aged couple at a pro-Brexit, right-wing rally that began outside a luxury hotel in Mayfair. They had driven from their small town in the Midlands to join the protest, and seemed ill at ease standing in the shadows of the glass-fronted towers where millionaires have second or third homes. “This doesn’t look like England,” the husband told me. “It’s another country.”

It’s not just London; other big cities have also shed much of the postwar drabness that I knew growing up here in the 1970s. Their pedestrianized streets of cafes and shops feel closer to continental Europe, yet are still recognizably British. When Britain voted in a referendum to join the European Community, as it was then, in 1975, its economy was sinking fast. “Goodbye Great Britain. It was nice knowing you,” wrote a Wall Street Journal columnist.

Britain’s economy has come a long way since then. But not everyone has felt the benefits, and their frustration at being written off by urban elites fed the Brexit campaign in 2016, which then set the clock ticking on Britain’s withdrawal from the EU in the name of “Taking Back Control.”

Prime Minister Theresa May’s government has no majority in Parliament for its Brexit deal, nor is it clear what kind of deal could muster a majority by a March 29 deadline, or if that deadline is firm. News channels report the dug-in arguments of all sides. Ms. May refuses to quit and insists that Brexit means Brexit. Each day feels like the last one or the one before.

Spend enough time watching “The Clock” – the Tate has held all-night weekend screenings for those curious to watch the after-hours action – and the loop is completed. There is no resolution. There is only past, present, and future.

The Tate jointly owns one of five copies of “The Clock” in public hands. Marclay stipulated that the film can’t be played simultaneously so museums must coordinate its exhibition. The Tate’s last showing in this run will be on Saturday. And so it must end. When will Brexit?

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

A bolt of integrity in a big African election

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

It’s a question that’s now playing out in the heart of Africa after a disputed election in Congo last month: How do you unrig a rigged election? The simple answer, of course, is to insist on integrity in the vote count. To many people’s surprise, the continent’s 55-nation bloc, the African Union, did just that on Thursday. The intervention by the AU is a blow for transparency and accountability in governance. And it comes at a time when Africa is expected to hold more than 20 elections in 2019 and when its level of democracy has been in decline for more than a decade. For Congo’s neighbors, the risks of postelection violence in a country the size of Western Europe may have been too high. The AU’s action also suggests even many authoritarian leaders in Africa have had enough of cross-border spillovers from political unrest. The integrity of the vote count is critical to ensure Congo can experience its first democratic transfer of power since independence in 1960. To Africa’s credit, the AU decided to try to unrig the results.

A bolt of integrity in a big African election

How do you unrig a rigged election?

The question is now playing out in the heart of Africa after a disputed election in Congo last month. The simple answer, of course, is to insist on integrity in the vote count. To many people’s surprise, the continent’s 55-nation bloc, the African Union, did just that on Thursday.

The AU expressed “serious doubts” about the provisional results of the Dec. 30 presidential election and asked Congolese officials not to declare an official winner until it can help find a solution.

In an Africa known more for fantasy democracies than real ones, the surprise intervention by the AU is a blow for transparency and accountability in governance. And it comes at a time when Africa is expected to hold more than 20 elections in 2019 and when its level of democracy has been in decline for more than a decade.

For Congo’s neighbors, the risks of postelection violence in a country the size of Western Europe may have been too high. The country saw widespread violence after disputed polls in 2006 and 2011 under outgoing President Joseph Kabila. The AU’s action also suggests even many authoritarian leaders in Africa have had enough of cross-border spillovers from political unrest.

The current pro-democracy protests in Sudan and Zimbabwe attest to the demand of young Africans for full democracy. Only about 40 percent of Africans believe their last elections were “free and fair,” according to a recent Afrobarometer survey.

The AU’s hand may also have been forced by the fact that an accurate vote count was revealed by poll watchers of the Roman Catholic Church and by several European news organizations. The United Nations Security Council and several Western governments also expressed concerns after the electoral commission announced that a lesser-known candidate, Félix Tshisekedi, had won. That announcement was contested by Martin Fayulu, the opposition candidate widely perceived as the winner.

The integrity of the vote count is critical to ensure Congo can experience its first democratic transfer of power since independence in 1960. The country of some 85 million has suffered two major civil conflicts in the past quarter century and widespread corruption under Mr. Kabila. His reluctance to leave office without a successor in power whom he can control may be the cause of the rigged election. To Africa’s credit, the AU decided to try to unrig the results.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Freedom for all – a universal right and a universal truth

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 4 Min. )

-

By Susan Booth Mack Snipes

In light of Martin Luther King Jr. Day on Monday, today’s contributor reflects on the role of reformers in the world and how their efforts, in order to be truly effective, must be based on the universal truth that freedom is the divine right of everyone.

Freedom for all – a universal right and a universal truth

One day, when my grandson was in sixth grade, I was reading a favorite children’s chapter book aloud to him at bedtime. It was the fictional story of a boy named Johnny Tremain, who was an apprentice to a silversmith during the days leading up to the American Revolutionary War. We got to the place in the book where Johnny overhears the meeting of men such as Samuel Adams, Paul Revere, and James Otis Jr. as they make the final commitment to the Revolution and must clarify exactly why they will fight for this cause.

Otis stands up and eloquently explains that it is not enough to fight for their own personal religious and political liberties, but that everyone, even those who oppose them, must be freer because of their struggle. He declares: “We give all we have, lives, property, safety, skills ... we fight, we die, for a simple thing. Only that a man can stand up” (“Johnny Tremain,” Esther Forbes).

As I read this sentence to my grandson, my eyes filled with tears and I set the book in my lap. I was moved with a sudden awareness that, to be truly transformative and successful, every fight to relieve oppression must be based on the universal truth that freedom is a divine right for all.

My thoughts went briefly to notable reformers like Mohandas Gandhi, Martin Luther King Jr., and Nelson Mandela, and I felt that this was indeed true of these men, that they had fought for a greater sense of liberty for everyone, even those who opposed them. King, for instance, once said, as recorded in a collection of his sermons called “A Gift of Love”: “One day we shall win freedom, but not only for ourselves. We shall so appeal to your heart and conscience that we shall win you in the process, and our victory will be a double victory.”

Then my thoughts went to Christ Jesus, who initiated the greatest revolution of all time. During his three-year ministry on earth he challenged the basic acceptance that man (male and female) is material, subject to inharmony, and governed by material laws that declare the necessity of disease, discord, and death. He transformed the lives of those struggling with moral lapses and disease through the spiritual understanding that this assumption of material being is a fundamental error, and that we are indeed, as the first chapter of Genesis declares, made in the perfect image and likeness of God, Spirit. And he didn’t just do it for his followers and those that loved him – he taught: “Love your enemies, bless them that curse you, do good to them that hate you” (Matthew 5:44). Jesus’ mission was to show all humanity how to be free.

Finally, my thoughts went to a reformer, Mary Baker Eddy, whose revolutionary thoughts brought a whole new spiritual perspective to the nature of science, theology, and medicine. She glimpsed the true purpose of Jesus’ mission. She worked tirelessly to carry his message forward into this age through healing and teaching.

I could hear these words from her primary work, “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” ringing in my thought: “Truth brings the elements of liberty. On its banner is the Soul-inspired motto, ‘Slavery is abolished.’ The power of God brings deliverance to the captive. No power can withstand divine Love. What is this supposed power, which opposes itself to God? Whence cometh it? What is it that binds man with iron shackles to sin, sickness, and death? Whatever enslaves man is opposed to the divine government. Truth makes man free” (pp. 224-225).

All of this flowed through my thoughts in a minute or so, and then I looked up at my grandson, who was quietly and intently waiting to see what Grammy’s tears were about. “You’ve probably wondered,” I said, “why Grammy and others like her devote their lives to spiritual healing in Christian Science, when the currents of worldly thought oppose it and flow strongly in the direction of finding solutions in matter for every problem. Well, we do it so that even those who oppose us will be freer. We do it because there is no true freedom for anybody except the freedom that is true for everybody. We do it so that everyone may stand up to materialism and its limitations and find the kingdom of heaven, of harmony, at hand!” Now there were tears in my grandson’s eyes, too.

With Martin Luther King Jr. Day around the corner, my heart goes out in thanks to every reformer who has worked not only for his own freedom but for the freedom of us all. Each one who takes this stand is taking a stand in some measure for the divine fact that freedom is a universal right because it is a universal truth.

A message of love

Sharing a taste of home

A look ahead

Have a good weekend. We won’t publish a full Daily on Monday, Martin Luther King Jr. Day, but watch for our special offering.

On Tuesday our Washington bureau chief will look at how professional negotiators see a way past the wall/shutdown impasse – and to better governance beyond – by looking at what lies beneath the stated demands.

We’ll leave you with this bonus read celebrating the late Mary Oliver, a Pulitzer Prize-winning poet “dazzled,” as one observer noted, “by her daily experience of life.” Here's a full reading of one of her poems.