- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- US ambassador’s chair at UN sits empty: Here’s who loses.

- ‘All hands on deck’: Can public-private solutions solve Calif. housing crisis?

- Baffled by Brexit? You’re not alone. Two Britons hash it out in texts.

- Pondering a presidential run, Sherrod Brown stops by for breakfast

- This ex-Marine leaves no veteran behind in after-war counseling

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

A ‘wanted man,’ and the power of public outcry

Interpol’s reputation has taken a drubbing in recent months. Its president disappeared last November, only to turn up in jail in his native China accused of corruption. And then a top Russian security official came close to replacing him, which would have raised further doubts about the neutrality of the international police network.

But today there was some good news on the “wanted man” front. Hakeem al-Araibi, a dissident Bahraini soccer player, returned to his home in Australia, where he is a refugee, after nearly three months as a prisoner in Thailand, where he had gone on honeymoon.

The Bahraini government had used Interpol to issue an international “red notice” demanding his arrest and extradition. Several other authoritarian governments are notorious for hounding dissidents through Interpol in this way – among them Russia, Turkey, China, and Venezuela.

This time, though, Mr. al-Araibi’s friends and family organized a campaign to free him that went viral around the world. In the face of international outrage, Bahrain withdrew the extradition request it had lodged with Thailand.

Interpol says it tries to weed out illegitimate red notices that are issued for political purposes, but it doesn’t always succeed. Hakeem al-Araibi’s case shows that a public outcry can set international affairs on a truer path. And it should prompt Interpol to redouble its efforts to thwart those governments who would abuse it.

Here are our five stories for today.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

US ambassador’s chair at UN sits empty: Here’s who loses.

Does President Trump want anything from the United Nations? Judging from the slow pace at which the administration is moving to replace Ambassador Nikki Haley, experts say, not much.

President Trump announced in early December he would nominate State Department spokesperson Heather Nauert to replace Nikki Haley as US ambassador to the United Nations. But two months later, the White House has yet to formally submit the nomination to Congress.

In the meantime, the US mission is being run quietly by acting permanent representative Jonathan Cohen. That’s in contrast to Ambassador Haley, who arrived at the UN saying the US would be “taking names” and making a list of who was on America’s side and who was not. The “no rush” approach, some experts say, reflects the White House’s disregard for the world’s preeminent multilateral institution. UN officials, meanwhile, say the UN is “conducting its affairs as usual.”

“It’s more about what doesn’t happen … the issues that aren’t presented for public airing and international pressure,” says Michael Doyle, director of Columbia University’s Global Policy Initiative. “Leaving the chair vacant for what’s now months really signifies how little a priority the UN and multilateral cooperation are to this administration,” Doyle says. So will the international community be there if the US needs its cooperation? At the UN, that seems to be an open question.

US ambassador’s chair at UN sits empty: Here’s who loses.

On a recent day at the United Nations, the Security Council debated the impact of organized crime at sea and aired international steps to reduce pirating in the world’s maritime trade corridors.

Secretary-General António Guterres announced his agenda for last weekend’s Africa Union summit in Ethiopia, laying out his priorities for helping leaders meet Africa’s challenges and stoke the continent’s remarkable economic and development progress.

And the UN Population Fund, better known as UNFPA, together with the European Union and other European countries, launched a new campaign to end female genital mutilation, a scourge that is still inflicted upon hundreds of thousands of girls annually.

In other words, it was a typical day at the UN.

Except that it all took place without the presence and participation of an ambassador from the United States.

President Trump announced in early December that he would be nominating State Department spokesperson and former Fox News program host Heather Nauert to replace Nikki Haley as the permanent US representative to the world body.

But two months later, Ms. Nauert is nowhere in sight. And no Senate confirmation hearing has been set, perhaps because the White House has yet to formally submit the president’s nomination to Congress.

In the meantime, the US mission to the UN is being run quietly by acting permanent representative Jonathan Cohen. That’s in contrast to Ambassador Haley, who arrived at the UN early in Mr. Trump’s term with guns blazing, saying the US would be “taking names” and making a list of who was on America’s side at the UN and who was not.

The “no rush” approach to replacing Haley reflects the disregard and even disdain of the White House for the world’s preeminent multilateral institution, some foreign-policy experts say. They point in particular to national security adviser John Bolton, a former UN ambassador himself who once famously quipped that the UN’s iconic East River headquarters high-rise could lose 10 floors and no one would know the difference.

Less attention to US issues

UN officials profess to be unfazed by the absence of an ambassador from the organization’s host country, and one of just five permanent members of the Security Council. The UN’s work does not hinge on the level of representation from just one member state, they say, no matter how powerful that country might be.

“Different countries sometimes take a while to fill a vacancy at the top of their delegation, but from our standpoint, as long as the work’s being done, that’s what matters,” says Farhan Haq, deputy spokesman for the secretary-general’s office. “The activities of the Security Council have not been disrupted, the UN is conducting its affairs as usual.”

If anyone is affected by the lack of an ambassador at the head of the sizable US mission to the UN, Mr. Haq says, it’s probably the US itself. “If the question is how it affects the US and its dealings with other countries, then yes,” he adds, “that can have an impact.”

Indeed, others with long experience at the UN say leaving the ambassador’s chair vacant for so long really hurts the US – by lowering the US voice, for example, and diminishing international attention to the kinds of issues the US traditionally has cared about – more than it throws sticks into the UN’s turning wheels.

“It’s more about what doesn’t happen when the US lowers its profile, how it matters is in the issues that aren’t presented for public airing and international pressure,” says Michael Doyle, director of Columbia University’s Global Policy Initiative and a past special adviser to former UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan.

As examples, he points to a lack of attention to the treatment of China’s Uyghur Muslim minority – an absence Dr. Doyle says China is all too happy to see – or the scant advocacy around humanitarian crises such as those in Yemen and Syria.

“The question is more how the agenda is shaped rather than how the agenda is managed,” Doyle says. Citing Syria, he says that without a skilled and imposing figure at the head of the US delegation to the UN, “the chances increase that the Syrian people will be left out of the equation as the Russians are pretty much free to work things out with [Syrian President Bashar al-] Assad.”

Pompeo attended Venezuela session

Officials in Washington say the US is not disregarding the important role the UN can play in putting critical issues on the international stage. They note that Secretary of State Mike Pompeo recently attended a Security Council session on Venezuela to underscore the international community’s role in helping to end that crisis.

Moreover, they point to the administration’s close work with the UN on priorities from aiding refugees near their home countries so they are not driven to migrate farther afield, to addressing HIV/AIDS, primarily in Africa.

Still, for some experts the clearest signal sent by the lack of a rush to get a US ambassador to the UN is a broad disregard for international institutions and working with large groups of countries on global issues.

“Leaving the chair vacant for what’s now months really signifies how little a priority the UN and multilateral cooperation are to this administration,” Doyle says. “You’d nominate and get somebody of stature up here pretty quickly if having a person to pursue US interests at the UN were important to you.”

Doyle notes that the George W. Bush administration neglected to name a permanent representative to the UN for about nine months after entering office. Then 9/11 happened, and very quickly the Bush White House got John Negroponte confirmed and up to New York.

What that signified, he adds, is that the Bush administration suddenly got the value to the US, superpower though it may be, of having the international community on its side. And indeed the UN, from the Security Council on down through many of its agencies, stepped up as a partner as the US went to war in Afghanistan to root out the perpetrators of the attacks.

Will world be there for US?

For some, that raises the question: If the US shows a lack of interest in and even disdain for the UN and multilateral diplomacy more broadly, will the international community be there if the US needs its cooperation?

That seems to remain an open question in the hallways of the UN.

But in the meantime, Haq says that at any rate relations between the secretary-general’s office and the US mission across First Avenue from the UN remain strong. And he says Mr. Guterres, who has met several times with Trump, senses he has a good relationship with the administration.

And as for the absent ambassador, Haq says UN officials are well aware that Trump has left other key agency positions unfilled or has taken more than the usual time to name replacements and get them confirmed when officials, up to and including cabinet members, have stepped down.

“So really,” Haq says, “we don’t feel singled out.”

‘All hands on deck’: Can public-private solutions solve Calif. housing crisis?

California sees a chance to solve its housing shortage, in the form of a $21 billion surplus, resolve from the new governor, and tech and foundation money. Can a regional approach to problem-solving overcome NIMBYism?

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

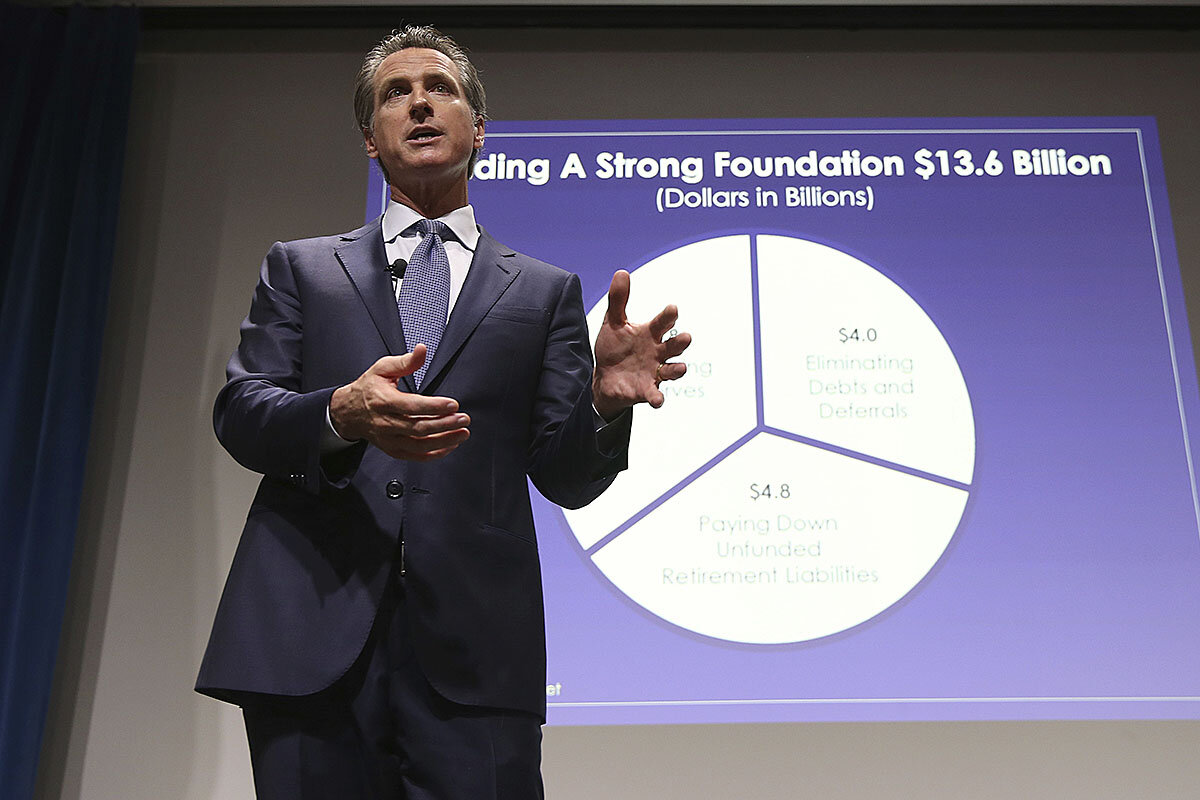

California Gov. Gavin Newsom, who was to give the State of the State speech Tuesday, has called the housing crisis “an existential threat to our state’s future.”

Silicon Valley tech companies and philanthropic groups have launched a $500 million investment fund for affordable housing in the San Francisco Bay Area. The Partnership for the Bay’s Future, bankrolled by Facebook, Genentech, and the San Francisco Foundation, among others, plans to produce 8,000 low-income housing units and preserve another 175,000 over the next decade. The campaign will seek to nudge cities in the region to look past geographic boundaries and collaborate with each other.

“What the partnership can do is get cities to see they’re part of a bigger effort,” says Assemblyman David Chiu, a Democrat from San Francisco. “We need every city and county to contribute.”

The partnership has enlisted religious leaders, community activists, and city and state officials to promote the importance of a regional response to the housing shortage. “Everyone is affected by the lack of low-income housing,” says Fred Blackwell, chief executive officer of the San Francisco Foundation, “and all of us benefit when there’s more of it.”

‘All hands on deck’: Can public-private solutions solve Calif. housing crisis?

In his inaugural address last month, California Gov. Gavin Newsom vowed to create “a Marshall Plan” to alleviate the state’s housing shortage. If the analogy sounded fanciful, he soon backed up his rhetoric, inserting $1.75 billion for affordable housing production into his state budget proposal. His actions heartened housing advocates frustrated by what they considered his predecessor’s inertia.

“We have to move past Jerry Brown, whose approach was, ‘The housing problem is too hard, let’s leave it to God,’ ” Matt Schwartz says.

The president of the California Housing Partnership Corporation, a nonprofit based in San Francisco that assists public and private efforts to expand low-income housing, he calls Governor Newsom’s attention to the issue “a welcome change.” Then he adds a sobering caveat about that Marshall Plan idea as Newsom attempts to fulfill a campaign pledge to build 3.5 million new housing units by 2025.

“Whatever initiatives he comes up with, they won’t be enough,” Mr. Schwartz says. His view reflects the reality that, unlike rebuilding post-war Europe, reducing the state’s housing deficit will require private funding. “We need an all-hands-on-deck approach.”

Evidence of that approach gaining momentum has emerged in California and other regions where the housing gap continues to widen. Newsom, who will give his State of the State address Tuesday, saw his cause receive a boost in January with the unveiling of a $500 million investment fund for affordable housing in the San Francisco Bay Area.

The Partnership for the Bay’s Future, bankrolled by tech companies and philanthropic groups, plans to produce 8,000 low-income housing units and preserve another 175,000 over the next decade. The campaign’s launch arrived the week after Microsoft revealed plans to invest $500 million in housing programs in the Seattle area, another region upended by the tech boom.

The list of backers includes Facebook, Genentech, the San Francisco Foundation, and the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative. Another prominent supporter, Kaiser Permanente, has announced a separate venture to form a $100 million loan fund with a national nonprofit, Enterprise Community Partners, that will nurture low-income housing growth in California and elsewhere.

The regional strategy of large corporations to address the Bay Area’s housing inequality bolsters Newsom’s crusade to ease a crisis he has labeled “an existential threat to our state’s future.” California’s affordable housing shortage of 1.5 million units accounts for a fifth of the country’s deficit of 7.2 million units, and 3 million tenants statewide spend more than one-third of their income on rent.

The depth of need exceeds what the state, even with a $21 billion budget surplus, can remedy on its own, explains Maurice Jones, the president of the Local Initiatives Support Corp., a New York-based housing nonprofit involved in the Partnership for the Bay’s Future.

“Housing is too big of an issue for only the government or only the private sector to solve,” he says. “We have to have everybody on board. That’s the only way.”

Broader solutions

The Bay Area comprises nine counties and 101 municipalities in a region with 7.6 million people. Across that many jurisdictions, each preoccupied with its own interests, disparities can remain unresolved until a crisis occurs.

Three years ago, a municipal water shortage in East Palo Alto, Calif., led city officials to impose a moratorium on new construction that halted an affordable housing complex and other projects. The problem dated to a 1984 regional water plan that resulted in the Silicon Valley enclave, whose residents are predominantly low-income and people of color, receiving less water than more affluent cities, including some with smaller populations.

The ban lasted more than a year before East Palo Alto obtained water transfers from two nearby cities with help from the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative. The philanthropic fund — formed in 2015 by Mark Zuckerberg, Facebook’s co-founder, and his wife, Dr. Priscilla Chan — provided $2 million to cover a portion of the transfer fees.

The Bay Area partnership will seek to foster that kind of collaboration for affordable housing by nudging cities to look past geographic boundaries.

“The solutions can’t just work within city or county borders,” says Amie Fishman, executive director of the Non-Profit Housing Association of Northern California. “People live, work, and drive across those borders, so we have to develop broader solutions that individual local governments don’t necessarily think about.”

The soaring housing costs and rental prices wrought by the Bay Area’s tech boom has induced a belated awakening within the industry about its responsibility. A few entrepreneurs have made attempts to atone.

The Chan Zuckerberg Initiative was the largest donor behind a pair of statewide ballot measures passed by voters last fall that will funnel a combined $6 billion into affordable housing and homeless services. Marc Benioff, the founder of Salesforce, contributed $7 million to a ballot initiative in San Francisco County that will raise an estimated $300 million for similar programs there by taxing big businesses.

A regional study last year found that, between 2010 and 2015, the Bay Area gained 617,000 jobs and added a meager 56,000 homes. The partnership will offer low-interest loans and lines of credit to developers and nonprofit groups to create, acquire, and maintain affordable housing. The infusion of financing could remove a stubborn obstacle to construction.

“One of the biggest political issues that cities face with low-income housing is [controversies over] using public money,” says the Rev. Paul Bains, co-founder of Project WeHope, a homeless shelter in East Palo Alto. “Private funding can help them get around that.”

The Bay Area campaign has enlisted religious leaders, community activists, and city and state officials to promote the importance of a regional response to the housing shortage. Their support may serve to blunt the pervasive NIMBYism that represents perhaps the strongest deterrent to new housing and persuade residents who lament the rising homeless population even as they oppose affordable housing.

“These things are connected. It’s not someone else’s problem,” says Fred Blackwell, chief executive officer of the San Francisco Foundation. “Everyone is affected by the lack of low-income housing, and all of us benefit when there’s more of it.”

Sharing the burden

A state law passed in 1967 requires California’s cities and counties to set targets every eight years for building affordable and market-rate housing in proportion to population growth. But the state has seldom enforced the guidelines, and a report in December showed more than 96 percent of California’s 539 jurisdictions lagging in production.

Newsom signaled an end to the leniency last month when he threatened to withhold state transportation funds from local governments that failed to build enough housing.

Two weeks later, the state sued Huntington Beach, accusing officials there of blocking low-income housing development. (The city has countered with two lawsuits against the state that assert the primacy of local control over housing matters.)

California has built fewer than 80,000 housing units a year since 2007, which is 100,000 short of the annual supply needed to meet demand through 2025. The sluggish output arises from complex building regulations, restrictive zoning ordinances, escalating construction costs, and local opposition to high-density housing.

The state’s suit against Huntington Beach illuminates Newsom’s intent to prod cities to share the housing burden. A spirit of cooperation has taken root in the Bay Area beyond the partnership. A coalition of housing advocates, business leaders, and labor interests has crafted a 10-point plan to tame the region’s housing crisis.

The policy proposals range from tenant protections to a streamlined process to approve certain housing projects. The group sent its plan to the Legislature a few weeks ago, and lawmakers will weigh whether to adopt the recommendations.

For Assemblyman David Chiu, a Democrat from San Francisco, the coalition’s work and that of the Bay Area partnership offer examples of the regional sensibility on housing that Newsom supports.

The chairman of the housing and community development committee, Assemblyman Chiu describes public-private alliances as “absolutely critical” to brightening the state’s housing future. He suggests the newly created investment fund will help the governor cultivate that sense of collective responsibility among cities, businesses, and residents — without litigation.

“What the partnership can do is get cities to see they’re part of a bigger effort,” he says. “We need every city and county to contribute.”

The Chat

Baffled by Brexit? You’re not alone. Two Britons hash it out in texts.

And now – Brexit. I am British, I’m an international affairs specialist, and I live in the European Union. But I have no clearer an idea than any of our readers or listeners how – or even if – Britain will leave the European Union in six weeks’ time. So I talked to a fellow British Monitor correspondent in search of clarity. Did I end up any the wiser? You can find out by reading the full transcript of our conversation (select “deep read,” below).

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 10 Min. )

-

By Monitor Staff

Rebecca Asoulin (engagement editor, representing the 99 percent of people confused by Brexit): Hey, Simon. How’s the future?

Simon Montlake (Brexit reporter, Brit): Hi. It’s March 30th and Brexit has happened.

In the end Britain left the EU without a deal. Nothing could be agreed on time, and there was lots of finger pointing about who was to blame.

People stocked up on food and so far the day has started normally, no sign of panic, but more police on the streets. Still, life goes on.

Does that sound like a plausible future, Peter?

Click “Deep Read” (above) to dive into our conversation.

Baffled by Brexit? You’re not alone. Two Britons hash it out in texts.

Two British staffers and one confused American staffer talk Brexit in a group message.

Rebecca Asoulin (engagement editor, representing the 99 percent of people confused by Brexit): Hey, Simon. How’s the future?

Simon Montlake (Brexit reporter, Brit): Hi, it’s March 30th and Brexit has happened.

In the end Britain left the European Union without a deal. Nothing could be agreed on time, and there was lots of finger pointing about who was to blame.

People stocked up on food and so far the day has started normally, no sign of panic, but more police on the streets. Still, life goes on.

Does that sound like a plausible future, Peter?

Peter Ford (senior global correspondent, Brit): Perhaps you are being unnecessarily alarmist. Your future is quite conceivable, but there are other possible futures.

For a start, British Prime Minister Theresa May might manage to strike a last minute deal with the European Union on the terms of an exit agreement and get it through Parliament by March 29th. The prospect of Britain falling off the edge of a cliff in a ‘no deal’ Brexit might concentrate Parliament’s mind.

And there is also a strong chance that London will run out of time, as you suggest, and simply ask Brussels for more time to work out a solution. The EU would probably agree, it doesn’t want a crash out either.

Simon: The clock is ticking. Tick tock.

Rebecca: I thought March 29th was a hard deadline for Britain to leave?

Peter: By law it is, but there are always ways around things in the EU.

Simon: If you’re May then you need a hard deadline to get a deal through Parliament.

She needs approval for her deal and so far she hasn’t got it. I think she’s trying to run down the clock so that members of Parliament (MPs) panic and fall into line.

The trouble is … some of them believe, or say they believe, that Britain can do perfectly well out of a no-deal Brexit.

Peter: That is the nut of the problem. Until now, May has seemed to put those sort of hardliners (and her desire to keep them in a united Conservative Party) above the need for a reasonable deal with the EU. It strikes a lot of Europeans on the continent that she has put party above country. But there’s not a lot they can do about it.

Simon: Do we need to talk about the flavors of Brexit?

Pistachio is finished, sorry.

Peter: May risks ending up with humble pie as the only flavor on offer.

Rebecca: Wait, so Britain can leave on March 29th with or without a deal. Are people referring to that as hard or soft? (Now I want soft-serve ice cream.)

Simon: Hard and soft Brexit is really about the end destination, not just the “divorce” on the table.

Hard Brexit means a clean break: Britain would have a free trade deal with the EU, similar to Canada and other large economies. But it would no longer have to follow all the rules of the EU.

A soft Brexit comes in various textures. But it keeps Britain in a tighter embrace with its European peers.

The basic trade-off is autonomy vs. access. Does Britain want access to EU markets? Fine, then Britain has to play by the EU’s rules. Does Britain want autonomy? Fine, then the EU and Britain will have a trade deal but Britain shouldn’t expect any favors.

Rebecca: So how do we get to that destination? The EU and Britain seem to be playing a game of chicken.

Simon: Free trade chicken!

Peter: Or chlorinated chicken if it comes in a free trade deal with the USA.

Rebecca: This conversation is making me hungry, and more confused. The EU and Britain seem to be on a collision course. Who's going to give in?

Simon: That is the million-euro question.

Peter: Well, it’s the same with all negotiations. If there is going to be a deal, both sides are going to have to make compromises. Which means stopping the game of chicken, stomping on the brakes, and getting out of their cars to talk.

But May has to contend with people in her party who don’t want to talk: As far as they are concerned, going off the road is an adventure, not necessarily driving into a ditch. And on the other hand, Europe is not going to reopen talks on a deal that has already been done.

Rebecca: So it sounds like the members of Parliament need to get it together. What’s stopping them from doing that?

Simon: I blame cake. Or rather cakeism. One of the prevailing -isms that make covering Brexit something of a parallel universe.

Brexit boosters assured the British public they could have their cake and eat it, when it came to leaving the EU.

Boris Johnson, the former mayor of London, actually used this analogy. He’s not known for his precision or policy detail, but he definitely was onto something.

Since then, everyone pushing their version of Brexit in Britain has been susceptible to cakeism.

Which is how we ended up in deadlock. Because you can’t have your cake AND eat it. Sadly, for cake lovers everywhere.

Peter: There is also a special breed of cakeist known as a unicorn hunter, don’t forget. He (or she) who spends his (or her) time tracking mythical beasts, such as totally unrealistic concessions from the EU.

And to be honest, I think that there has been too much unicorn hunting, and raising of unrealistic expectations, for the British public. The way the whole Brexit negotiations have been handled over the past couple of years represents a pretty depressing failure of political leadership, and that has left voters on both sides of the debate angry and depressed.

Simon: The latest example of unicorn hunting was last week’s effort by the ruling Conservative Party to come together.

They proposed something called the Malthouse Compromise. Sounds like a bad airport novel, doesn’t it?

The compromise – named after a Conservative MP called Kit Malthouse – basically boiled down to a Brexit deal with a reworked Ireland backstop and a highly imaginative application of World Trade Organization rules.

It took about 10 minutes for the flaws to become apparent and another day for EU negotiators to let it be known that, no, sorry, that unicorn does not exist and they would not agree to the Malthouse Compromise. Just like the others before it.

Peter: OMG he mentioned the Ireland backstop. Now you’ve done it, Simon. You have to explain!!!

Simon: Oh no, the backstop.

Rebecca: It’s some sort of analogy right?

Peter: ...Deathly hush from Simon...

Simon: It’s a cricket analogy, of course. Beyond that, well...

Peter: As you say: well.

Let’s keep this as simple as possible, but bear in mind that the whole Brexit agreement now hinges on “backstop” arrangements on the border between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland.

The 1998 peace deal that ended the strife in Northern Ireland abolished a ‘hard’ border between the two. That was OK because both were in the same trade bloc. But on March 30th, Northern Ireland will not be in the EU anymore.

Brussels and London agree Brexit should not upset the peace deal, and if the EU and UK negotiate the free trade deal they envisage there will be no problem.

But if they don’t, the EU is insisting on a ‘backstop’ arrangement under which Northern Ireland would stay part of the EU customs union.

But if that happens, Northern Ireland would not be under the same law as the rest of the United Kingdom. Not so united. And no British government would accept that.

The only way out would be if the whole of the UK stayed in the customs union. But ‘hard’ Brexiters wont accept that. May is stuck between that rock and that hard place.

Simon: Sounds intractable, right?

Peter: Intractabilissimus.

Simon: Actually I think there are ways to fix this problem....

Peter: Make that man prime minister!

Simon: Northern Ireland stays in the customs union. Britain is out. Goods can be checked when they cross the Irish Sea.

Now the reason why that is not on the table is simple political math.

May’s government is propped up in Parliament by 10 MPs from Northern Ireland.

So what they say goes. If she wants to stay in power. And they say, “no way” to a border in the Irish Sea between Northern Ireland and Britain.

Peter: As I said: INTRACTABILISSIMUS.

Simon: I find it ironic that the US is convulsed by political fighting over building a border wall.

And the UK is convulsed by political fighting over how NOT to put up a border barrier.

“Don’t Build The Wall!”

Rebecca: But why is this issue over the Irish border called a backstop?

Simon: The backstop in cricket is like the catcher in baseball. The last man stopping the ball from going out.

Think of the backstop as an insurance policy. The backstop is there to stop the ball (i.e., Brexit) smashing the window of peace in Northern Ireland.

Peter: Make that man poet laureate!

Rebecca: So there needs to be some kind of agreement on this issue, which means there needs to be a deal right?

Peter: Rebecca, if there is no agreement on the ‘backstop’ there will be no agreement on Brexit, and Britain will crash out without a deal on March 29th, leading to all sorts of problems.

Or the British government will ask for more time, or there might be a second referendum on Brexit, or there might be elections. Lots of dramatic possibilities, but on the street, there are an awful lot of BOBs (people who are “Bored of Brexit”). Have you come across many in the UK, Simon?

Simon: Britain is BOB central. You wouldn’t know it from the news headlines but lots of people are sick of the whole thing.

Peter: On my side of the channel, in Paris, it’s hard to find many people who care much either. Partly it’s because Britain has always been a bit ‘semi detached’ from the European Union, partly it’s because continental Europeans have just got other more important things to worry about.

Rebecca: Why should people pay attention to every turn and machination? Every little detail seems really exhausting, but the consequences are so serious.

Simon: I’ve been back and forth to Britain for the last three months covering the ins and outs of Brexit so it’s easy to get caught up in the details.

Remember, Rebecca, that there are millions of EU citizens living in Britain on the basis of EU membership allowing internal migration, just as Texans move to New York.

The question of their right to remain is up in the air. And no matter how many assurances they hear from British leaders there is a lot of unease and a sense of not being as welcome as before. We don’t know how this ends.

I totally understand why Europeans are bored of British intransigence. Lots of misunderstandings and misgivings all around.

Peter: And don’t forget that a lot is hanging on this economically, too. Investment in the British car industry has fallen by EIGHTY PERCENT over the last year as a result of uncertainty over Britain’s future.

There is no getting away from the fact that if this all ends as badly as it might, Britain is simply not going to be as attractive a place to invest as it is now. Companies are going to move to the place where they sell most goods – continental Europe – and they will take a lot of jobs with them.

Rebecca: The future of Britain really is at stake both economically and the way people see it. What do you both think is the most likely way Britain will leave?

Simon: I’ll go first.

Peter: Brave man...

Simon: I don’t see any other deal on the table. May will go back to Parliament and there will be defections from the opposition that will get her over the line.

She will have to disappoint the hard Brexiters on her side. No other way to square the circle. Probably an extension of a few months will be needed to pass all the necessary legislation.

Then we move on to the negotiations for what comes next. And that is going to take years.

Peter: That means you expect her to swallow the backstop and risk being remembered as “the prime minister who destroyed the Union.” Does she have the courage for that? I agree that your scenario is the most likely, but this is going to be a cliffhanger till the very last minutes of March 29th, I suspect.

Rebecca: It seems like a slow crawl to the 29th from here.

Simon: OK Rebecca, what do you think? You’ve heard what we have to say about unicorns and cake and backstops. Where do you see Brexit going?

Rebecca: This March 29th deadline seems like an internal deadline the UK needed to kick itself into gear to agree to something. It seems like they have to agree to something, whether that means they ask the EU for more time or they somehow agree by the 29th. I can’t see them going off the cliff.

But really I don’t know.

Peter: That makes three of us. Uncertainty has been the name of this game for the past two and a half years, since the British electorate voted to leave the EU but without deciding exactly how. And I think you are right – it will stay uncertain till the end.

Rebecca: Thank you both for your time!

Simon: Great. Time for lunch.

Rebecca: Have some free trade chicken and/or soft serve, both of which I’m very much craving now.

Peter: I shall have some supper and then must run to choir practice.

Simon: Ciao, Peter.

Peter: Ciao. This has been fun. Let’s do it again sometime.

This transcript has been lightly edited for clarity and length.

Did you enjoy this conversation format? Let us know.

Monitor Breakfast

Pondering a presidential run, Sherrod Brown stops by for breakfast

The Democratic senator from the critical battleground state of Ohio would focus his campaign on the concerns of working people – and says his rumpled authenticity is a plus in the industrial Midwest. He plans to make a decision in March.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

Throughout his career in public service, Sen. Sherrod Brown says he never considered running for the White House. But now he is making a case for himself: He was the only Ohio Democrat to win statewide in 2018 (and it wasn’t close), after President Trump won the critical battleground state comfortably in 2016. That’s a sign, analysts say, that in the 2020 general election, Senator Brown could retake the “blue wall” states – Michigan, Wisconsin, and Pennsylvania – that handed Mr. Trump the presidency.

Senator Brown’s campaign would focus on the “dignity of work,” addressing the concerns of working people – wages, retirement, health care, day care.

Before the senator took questions, he made a point of calling on Trump to rein in supporters who attack the media, in response to video showing a man shoving a BBC cameraman at Trump’s rally in El Paso, Texas, Monday night. “We all are concerned that there will be something worse happening at some time in the future,” Brown said.

Click the “Deep Read” button for excerpts from the breakfast conversation, lightly edited and condensed for clarity.

Pondering a presidential run, Sherrod Brown stops by for breakfast

Sen. Sherrod Brown (D) of Ohio made his first appearance at a Monitor Breakfast Tuesday, midway through a “listening tour” of early presidential primary states.

Throughout his career in public service, Senator Brown says, he never considered running for the White House. But now he is making a case for himself: He was the only Ohio Democrat to win statewide in 2018 (and it wasn’t close), after President Trump won the critical battleground state comfortably in 2016. That’s a sign, analysts say, that in the 2020 general election, Brown could retake the “blue wall” states – Michigan, Wisconsin, and Pennsylvania – that handed Mr. Trump the presidency.

Brown’s campaign would focus on the “dignity of work,” addressing the concerns of working people – wages, retirement, health care, day care.

Before the senator took questions, he made a point of calling on Trump to rein in supporters who attack the media, in response to video showing a man shoving a BBC cameraman at Trump’s rally in El Paso, Texas, Monday night.

“We all are concerned that there will be something worse happening at some time in the future,” Brown said.

(The White House issued a statement late Tuesday afternoon saying it “condemns all acts of violence against any individual or group of people – including members of the press.”)

What follows are excerpts from the breakfast conversation, lightly edited and condensed for clarity:

Q. How are you feeling about the 2020 race? Is the water warm?

I’m not ready to jump in. This was not a longtime dream of mine to be president of the United States, and I know that many candidates who’ve announced have been thinking about this for months, years, longer than that. I haven’t.

In November, I began to see more and more Democrats thinking we need to choose between talking to our progressive base and exciting the base as we do, and talking to workers about their lives, as if that’s a choice. We’ve got to do both.

We don’t win swing states like New Hampshire and Nevada and Ohio and Michigan unless Democrats talk to our progressive base, never compromising on progressive values on civil rights and LGBT rights and women’s rights and on gun issues, never compromising on those – but speaking to workers at the same time. And that’s what the “dignity of work” tour is all about. We will make that decision [about a presidential campaign] in March.

Q. What have you learned so far from your tour?

One of the most interesting things is the response on the Patriot Corporation Act [which would reward companies that keep jobs in the US and pay American workers well] and on the Corporate Freeloader Fee [which would require corporations to reimburse taxpayers if their workers receive government assistance, such as food stamps]. In rallies or house parties, they probably get the best response, because voters generally understand the importance of a tax system that actually works for workers and works for families.

Something else that’s been increasingly obvious to me is the importance of making day care a public good. I think that’s increasingly a role for government. I think the public is coming to that conclusion.

Q. Several of your colleagues and would-be opponents have endorsed various forms of Medicare for All and the Green New Deal. What’s your view of these two ideas?

I believe in universal [health care] coverage. I want to add to Obamacare, and I want to help people now. That means, if you allow voluntary buy-in [to Medicare] at 50 that’s not just practical and smart, it will help people today.

Eventually we probably get to something like Medicare for All, but we start by expanding it and helping people now.

Q. What about the Green New Deal?

Climate change is one of the most important moral issues of our times. We should be much more aggressive. But I don’t need to co-sponsor every bill that others think they need to co-sponsor to show my progressive politics. I want to get something done for people now.

Q. Will the US-Mexico-Canada Agreement, the replacement for the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), pass Congress? [Brown opposed NAFTA from the start, during his days in the House.]

I don’t see evidence that it’s going to pass. I don’t know what Republicans are going to do. I know that there are few Democrats in the Senate that support it.

[US Special Trade Representative Robert Lighthizer] thinks that he’s done the best he can, and I assume he has, but it just simply isn’t good enough for most Democrats, if not almost all of us. It’s not good enough for organized labor, it doesn’t work for workers. It doesn’t work for Mexican workers, in my mind.

Q. Hillary Clinton faced regular criticism over her voice and appearance. Do you worry that your gravelly voice and shaggy hair would make you unlikable as a presidential candidate?

That shaggy hair, as you say, and gravelly voice will work in union halls in the industrial Midwest, first of all. That was a pretty funny question.

I see what’s behind the question. It’s clear, women are judged differently, and it’s unfortunate that our society still judges women differently. A lot of the criticism of Hillary was unfair in that way, because she was held to a different standard.

This ex-Marine leaves no veteran behind in after-war counseling

After a combat deployment in Iraq, Zach Skiles faced mental trauma when he returned home. Now he draws on his experience to help fellow veterans struggling with the aftermath of war.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Researchers estimate that 11 to 20 percent of the more than 2.7 million men and women who deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan have been diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder. Zach Skiles is one of them. As a then-20-year-old Marine, Mr. Skiles took part in the US invasion of Iraq. During his nine-month tour, four of his closest friends died, two of whom he saw killed in action.

After his discharge in 2004, he drifted between jobs and school, dulling his PTSD with marijuana and alcohol. He joined The Pathway Home, a residential treatment program in northern California, where he was so moved by the support and renewed purpose he found, he decided to commit his life to helping fellow veterans.

“Pathway completely changed my life and brought me back into the world. And that’s what I’m trying to do: bring these guys back,” says Skiles. At a VA program he helped create, he uses his military background to help veterans like Anthony Allen heal from the psychological wounds of war. As Mr. Allen says of Skiles, “He saved my life.”

This ex-Marine leaves no veteran behind in after-war counseling

Zach Skiles arrived at The Pathway Home in 2010 knowing he needed help yet convinced he had his problems under control. The residential treatment program, located in northern California’s Napa Valley, provided intensive therapy to Iraq and Afghanistan combat veterans coping with mental trauma. There they began the long journey back from war.

Seven years earlier, as a 20-year-old Marine, Mr. Skiles had taken part in the US invasion of Iraq. During his nine-month tour, four of his closest friends died, two of whom he saw killed in action. After his discharge in 2004, he drifted between jobs and school in San Francisco and Los Angeles, straining to prove to others – and himself – that he had left Iraq behind.

“I was in denial that I had PTSD,” he recalls, referring to post-traumatic stress disorder. He received occasional counseling at Veterans Affairs (VA) clinics; more often, he relied on marijuana and alcohol to tame a mind still gripped by the extreme alertness required in combat. “I was kind of lost inside myself.”

At The Pathway Home, where he lived with fellow veterans in a dormlike setting akin to military barracks, Skiles learned to set down the inner burdens of war. In time, he found renewed purpose, and for the past two years, guided by that program’s ethos, he has counseled veterans of America’s 21st-century wars at a VA clinic in Martinez, Calif., on the fringes of the San Francisco Bay Area.

The VA program bears similarities to Pathway, with a daily group session at the heart of its therapy regimen. Skiles coaxes the combat veterans to share with each other what they reveal to no one else: the nightmares and flashbacks, the rage and despair, the memories of the dead and the impulse to die.

As he seeks to shepherd them through the valley of the after-war, his military background disarms their wariness, explains Dr. Jeffrey Kixmiller, director of the clinic’s residential program.

“Zach has immediate credibility because he’s one of them,” he says. “And he has insights about them that we might never otherwise have because he knows what it’s like to be in combat.”

Researchers estimate that 11 to 20 percent of the more than 2.7 million men and women who deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan have been diagnosed with PTSD linked to their service. Skiles approaches his role with an urgency informed by his own ordeal and an awareness of that vast need – a need illuminated by Pathway’s tragic demise last year.

“Pathway completely changed my life and brought me back into the world,” he says. “And that’s what I’m trying to do: bring these guys back.”

Empathy and resilience

The Pathway Home occupied a building on the bucolic grounds of the Veterans Home of California in Yountville. The tranquil setting contrasted with the internal chaos of the veterans receiving therapy.

Albert Wong, a former Army infantryman who deployed to Afghanistan in 2011, started attending Pathway early last year. His erratic behavior led to his dismissal in February. Two weeks later, he returned to the premises and fatally shot three clinicians, one of whom was pregnant, before turning the gun on himself.

In the aftermath, Pathway’s board of directors chose to end a program that had treated some 450 veterans since 2008 and had earned national attention months earlier with the release of “Thank You for Your Service.” The feature film, based on the 2013 bestseller of the same name, dramatized one veteran’s passage through Pathway.

A week earlier, Skiles had traveled to Yountville and met with the three clinicians – Christine Loeber, Jennifer Golick, and Jennifer Gonzales Shushereba – to explore ideas for collaboration. He took them into the room where he had lived for four months, where his Iraq tour had ended at last.

At a memorial for the trio, Skiles, asked by Pathway officials to deliver an address on behalf of its graduates, fought back tears and extolled them “for giving everything in service of veterans.” Their deaths deepened his resolve to aid those who remain shadowed by war.

“Some people see what happened as a reason to turn away from veterans,” says Skiles, a doctoral student in clinical psychology at a graduate school in Berkeley, Calif. “To me, it showed exactly why these programs are important.”

Soon after Skiles had enrolled at Pathway in 2010, Fred Gusman, the program’s founder, identified in him a blend of empathy and resilience – ideal traits for a therapist. Mr. Gusman, a Vietnam veteran and former senior director with the VA’s National Center for PTSD, later invited him back as a peer counselor.

“Zach decided early on in treatment that he wanted to do more,” says Gusman, who stepped down from Pathway in 2015. “He understands what recovery takes – the work you have to put in – and he knows it’s normal to have setbacks.”

Gusman recognized that veterans tend to view PTSD as a personal flaw that violates the mythical warrior code. Living at Pathway, Skiles grew to accept that his condition represents a normal reaction to combat’s abnormal extremes. He attempts to cultivate a similar shift in thinking among the veterans he now counsels so that they might escape the emotions – self-blame, unresolved anger, survivor’s guilt – that can keep them trapped on a distant battlefield.

“We’re not changing the past,” he says. “We’re just getting perspective on it and figuring out how to live with it.”

A sense of belonging

Anthony Allen unspooled a decade after losing several friends during his tour in Iraq with the Army National Guard. He left the military following his return in 2007 and filled the ensuing years with lucrative work in the country’s oil fields and unrestrained partying when home in northern Arizona.

Two years ago, while blackout drunk, Mr. Allen was involved in a domestic dispute with his then-fiancée, who shot him in the neck. He remembers nothing of the incident that partially paralyzed one side of his body. (No charges were filed in the case.)

As Allen recovered in the hospital, a friend told him about the VA program in Martinez. He credits Skiles with giving him insight into PTSD that has eased his shame, allowing him to begin the process of forgiving himself.

“He saved my life,” says Allen, who lives in transitional housing near the clinic as he continues his physical therapy and counseling. He came to the program believing that talking about combat trauma would expose him as weak. He instead felt embraced. “I was welcomed with open arms. I had never experienced that kind of love before.”

On a recent weekday, Skiles sat in his small office, where stacks of files and bags of candy vie for table space. Immersed in the demands of the clinic and school, he has yet to map out his career direction beyond a desire to counsel former service members.

At a given time, the Martinez program works with eight to 10 veterans, who sleep two to a room and share a space where they can cook, watch movies, and shoot pool. The milieu evokes garrison living and serves to lure them out of self-isolation.

“What they’re often missing is that tribal feeling,” Skiles says. In addition to counseling sessions, he leads art therapy classes and organizes outings for them, including weekly visits to an animal rescue facility to learn to train service dogs. “We want to give them a sense of belonging.”

Most of the veterans stay four to six months, and the program assists them with obtaining VA benefits, job referrals, and other supportive services as needed. As part of their recovery, Skiles emphasizes that reintegrating into civilian life marks the final stage. The lesson draws on a principle he absorbed years ago at The Pathway Home.

“You can either let what you experienced in war hold you back or be the thing that makes you thrive,” he says. “When they leave here, we want them to know there’s a reason to live. I found it. I want to help them find it.”

Three other groups addressing trauma

UniversalGiving helps people give to and volunteer for top-performing charitable organizations around the world. All the projects below are vetted by UniversalGiving; 100 percent of each donation goes directly to the listed cause.

• Hagar USA is committed to reinstating wholeness in the lives of women and youths who have endured human rights abuses. Take action: Help provide education access for Cambodian human rights abuse survivors.

• El Pozo de Vida fights human trafficking through prevention and intervention and aims for the restoration of children, families, and communities. Take action: Financially support one trafficking survivor for a month as she works toward a better future.

• SBP, which got its start in St. Bernard Parish in Louisiana after hurricane Katrina, strives to reduce the time between disaster and recovery. Take action: Make a donation to aid people, especially those who are vulnerable, in New Jersey’s Monmouth and Ocean Counties, where SBP has superstorm Sandy operations.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Snowballing peace with North Korea

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

South Korean President Moon Jae-in calls it turning snowballs into a snowman. The idea: Think ceaselessly about small steps toward peace and end the military tension on the Korean Peninsula.

That’s good advice as President Trump and North Korean leader Kim Jong-un plan to meet for their second summit Feb. 27-28 in Vietnam. The summit comes with low expectations for big steps toward disarmament. But Mr. Moon suggests creating a mood for peace. What’s needed: a virtuous circle of trust, starting with the two Koreas.

An emerging trust between the two Koreas began in July 2017, when Moon offered to hold talks soon after becoming president. Last year, Moon and Kim met three times. The two have reduced tensions in the demilitarized zone. In August, many Korean families split by the long divide were able to meet. And this Friday, the two Koreas are expected to submit a joint bid to the International Olympic Committee to co-host the 2032 Summer Games.

Moon is not expected to be at the talks in Hanoi. But his moves may influence the negotiations. They could be the snowballs.

Snowballing peace with North Korea

One way to end the nuclear-tipped military tension on the Korean Peninsula, according to South Korean President Moon Jae-in, is to think ceaselessly about small steps toward peace. He calls this turning snowballs into a snowman. That’s good advice as President Trump and North Korean leader Kim Jong-un prepare to meet for their second summit on Feb. 27-28.

The summit, which is being held in Vietnam, comes with low expectations that Mr. Kim is ready to take concrete steps toward giving up his nuclear weapons or missiles. This is the conclusion of Mr. Trump’s own intelligence chiefs. Kim may make some concessions, as he did in last June’s meeting in Singapore. But North Korea has a long record of retreating or cheating on nuclear agreements.

Mr. Moon suggests creating a mood for peace as much as the means for peace. Threats by the US or offering economic incentives to the North can only go so far. What’s needed is a virtuous circle of trust, starting with the two Koreas. After all, it is their unresolved war from the early 1950s that must first be officially ended.

An emerging trust between the two Koreas began in July 2017, when Moon offered to hold talks soon after becoming president. At the time, the North was busy testing atomic weapons and new missiles while Mr. Trump was making threats. In December, Moon suggested the two countries field a joint team for the 2018 Winter Olympics in South Korea. Kim jumped on the idea and thus began an unprecedented era of warming cross-border relations. The opening then led to Trump agreeing to the June summit with Kim.

Last year, while Kim and Trump met once, Kim and Moon met three times. The two have reduced tensions in the demilitarized zone, through such actions as removing some guard posts and land mines. In August, many Korean families split by the long divide were able to meet. This week, a group of about 250 South Korean religious and civic leaders visited the North. And this Friday, the two Koreas are expected to submit a joint bid to the International Olympic Committee to co-host the 2032 Summer Games.

Inter-Korea reconciliation, says Moon, is now the “driving force” behind international efforts to denuclearize North Korea. Or as a former US negotiator with North Korea, Christopher Hill, put it, “I think the game has changed somewhat under Moon Jae-in.”

Moon is not expected to be at the coming talks in Hanoi. But his peace moves may very well influence the negotiations. They could be the snowballs in the room.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

At home in the heart of Paris

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 4 Min. )

-

By Myriam Betouche

Years of unsuccessfully searching for affordable housing closer to her job left today’s contributor discouraged. But considering a more spiritual view of home shifted her outlook completely, and soon she found a flat that met her needs beautifully.

At home in the heart of Paris

For years I wanted to live inside the city of Paris. But after three years of casually searching for apartments, I wasn’t finding anything suitable. The price of the market for “inside Paris” was still way too high for what I could afford despite an increase in my income.

But I felt that this move would be a progressive step. Not only would it reduce my commutes to church and work, which sometimes involved sitting in hours of traffic, but it would help educate me about how I might help address important issues affecting the heart of the city.

One night I was watching a TV program about the housing crisis in the Paris area. According to the program, with a shortage of housing for the coming years and the rising price of real estate, middle-class people were being forced to move farther away in order to find an affordable place to live.

As a student of Christian Science, I had seen that prayer can bring to any individual creative insights and inspired ideas from God. The limiting idea that people were grouped into categories and could only live in certain places did not seem consistent with this. So I looked up references to the word “category” in a book I’d found invaluable in solving problems through an understanding of God: “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures” by Mary Baker Eddy, the discoverer of Christian Science. My study of its ideas on this subject led me to such a helpful statement: “The categories of metaphysics rest on one basis, the divine Mind. Metaphysics resolves things into thoughts, and exchanges the objects of sense for the ideas of Soul” (p. 269).

Divine Soul is another name for Spirit, God, so I realized there was a solid, spiritual premise from which I could start my quest for home: thinking about the ideas I received from God. This spiritual starting point helped sweep away the doubts I had about finding housing.

I confidently returned to my search but soon found myself visiting flats that had no kitchen or parking. These visits made me feel exhausted and depressed, and I began to think back to the bleak news about housing I’d heard on TV.

But I was convinced that persistence in prayer would bring clarity. One night I casually mentioned my discouragement to a church friend. He shared an idea someone had once told him: “Your place is your individuality.”

That one simple idea meant a lot to me. It gave me a sense that the concept of place or home couldn’t be separated from me and that it was spiritual, since I understood from my study of Christian Science that the true individuality of each of us lies in our relation to Spirit, our divine creator. Instead of analyzing market trends and fretting about financial predictions, I realized, I could consider my spiritual individuality and just stay there. That is, I could find my sense of home right where I was – in my thought of God.

That night, in prayer, I began to resolve “things into thoughts” and exchange “the objects of sense for the ideas of Soul,” as that idea from Science and Health said. I began a list of qualities that express Soul, which I knew my true, spiritual individuality already included, such as God-given light, peace, tranquility.

Over the next three days I continued making my list, considering what various amenities could represent to me spiritually. For instance, a view of the sky represented a spiritual view of God’s nature as infinite, full of boundless possibilities. This helped me mentally define the uniqueness of my individuality. And it helped me acknowledge that God already had a perfect place for me.

As I was doing this, a real estate agent called me about an available flat. It had an open view to the Eiffel Tower and seemed just too good to be true. This flat had been taken by someone who’d then changed her mind, and now it was on the market again. It had everything on my list, including a garage and a kitchen. It was in a location that was perfect for me – and it was in my price range.

I quickly rented the flat. It turned out to be a very peace-filled home and neighborhood, and seeing the Eiffel Tower glitter at night always reminded me how brilliant God’s love is.

As we come to learn that the expression of beauty and Soul isn’t reserved for a few, we see more evidence of God’s love in our lives. This is God’s promise for each one of us.

Adapted from an article published in the Dec. 3, 2007, issue of the Christian Science Sentinel.

A message of love

Swiss gold

A look ahead

Come back tomorrow. We’re working on a story about the rising activism of big US outdoor brands. Can an industry that has traditionally put profit first show moral leadership?