- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- 20 years after Columbine: one parent’s reflection

- Tangle of church and state roils Ukraine’s Orthodox parishes

- Should the census ask about citizenship? Supreme Court to weigh in.

- How to defy apartheid? For journalist Juby Mayet, with pen in hand.

- In Jordan, a place for animals to forget the trauma of war

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Rising focus on the uneven geography of opportunity

Opportunity zones are an old idea with a good motive – to leave no community behind on jobs and well-being. Back in the 1980s, Republican Jack Kemp urged this concept of geographically targeted tax breaks to revive downtrodden communities. Now the idea is gaining fresh life.

Why now? One new report from the Hamilton Project in Washington puts it this way: “For much of the 20th century, the large gaps between regions were closing as poorer places grew faster, converging with higher income locations. Since around 1980, though, that convergence has stopped, leaving sizable gaps in economic outcomes across places.”

The challenge is seen in ailing rural towns, urban neighborhoods that have become job deserts, and the way some large cities lag behind others in vitality. On the flip side, it’s visible in the controversy generated when tax breaks are targeted toward the already successful – like Amazon and its foray into New York and the ensuing about-face.

Done right, localized tax incentives have bipartisan appeal. President Donald Trump touted an opportunity zone feature of his tax-cut law at an event today in Washington. “That’s bread on the table. That’s meat in somebody’s kitchen,” said Democratic Mayor George Flaggs of Vicksburg, Mississippi. The measure helped repurpose one old factory in his city.

More broadly, both liberals and conservatives are exploring “place-based” solutions that can range from government investments in infrastructure or education to local leaders redefining their community’s niche in the wider economy. Sometimes philanthropy is a lever of change, as the Monitor’s Simon Montlake has reported from Tulsa, Oklahoma. Don’t miss the finale of his series tomorrow.

Now to our stories for today, including how church is being drawn into the Russia-Ukraine conflict, a journalist who changed perceptions in South Africa, and help for animals caught up in war.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

20 years after Columbine: one parent’s reflection

Twenty years after the Columbine massacre, a Monitor reporter reflects on that day and how it has changed society from her perspective as a former Colorado high school teacher, an education reporter, and a parent.

Like most of the country, I was horrified when I first learned of the shooting at Columbine High School in Colorado. In those days, I was a Colorado high school teacher and couldn’t help but picture my students in the place of the students who were gunned down.

Thinking back to Columbine today, two decades later, I’m filled with a profound sadness not just for the students and teachers who were killed and injured that day, but also for the era that it began.

In my years as a Monitor staff writer I have written about many school shootings, each time struggling to find fresh angles apart from the awful specifics that made each event, and the individuals involved, unique.

But perhaps the biggest challenge of the post-Columbine world has been trying to help my children process this era that seems so very different from the one in which I was raised.

The solution that I have found has been to focus on the good. I’d be lying if I said I don’t experience pangs of fear as a parent, wondering what kind of world I’ve brought my children into. But I don’t want that fear to govern my life or theirs.

20 years after Columbine: one parent’s reflection

When news of the Columbine shooting broke, I was sitting in a restaurant in Moab, Utah, on spring break from the Colorado high school where I was teaching that year.

I was horrified: The event seemed unimaginable, unspeakable, and I pictured my students in the place of the students who were gunned down.

When I returned to campus – an alternative residential high school in Estes Park – a few days later, we held a moment of silence for Columbine High School during the first all-school gathering. It’s a tradition that continues at the school, at every morning gathering, to this day.

What I didn’t realize 20 years ago was that that horrific event was ushering in a new era in which mass shootings would come to seem, if not commonplace, at least somewhat familiar, following a script we all had to learn. In my years as a Monitor staff writer – many of them on the education beat – I wrote about school shootings in Red Lake, Minnesota; in Sandy Hook, Connecticut; in Sparks, Nevada; on the Virginia Tech campus.

Together with my editors I worked to find new angles, apart from the awful specifics that made each event, and the individuals involved, unique. There were school safety debates: metal detectors? Lockdown drills? Gun-control emerged as a major issue: Would eliminating the “gun-show loophole” that allowed people to bypass normal background checks help? What about child access prevention laws? And there were the constant efforts to find a “why” – bullying or mental illness or some sort of reason that could explain such a terrible action.

Columbine was always a touchpoint. It certainly was not the first school shooting, but when it occurred it was the most deadly in the modern era. And it was the first time that it entered our national consciousness that schools were not a haven. In several subsequent shootings, there were signs the perpetrators were inspired by the two Columbine shooters.

And, of course, it wasn’t just schools that were no longer seen as safe. Mass shootings occurred in a movie theater and a nightclub, in churches and synagogues and mosques.

We’ve labeled those born since 1999 the “Columbine Generation,” children who have never lived in a world where school shootings – and mass shootings more broadly – weren’t seen as a danger. These children integrated lockdown and shooter drills into their school routine the way past generations did with the more banal fire and tornado drills. Last year, when a shooter at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School killed 17 people in Parkland, Florida, it shouldn’t have been surprising that many of the students there became a powerful voice for change, refusing to accept this constant threat of violence as a new normal.

As a student of the 1980s and ’90s, I grew up seeing schools as safe territory. But I became a parent in a new era. When the Sandy Hook shooting happened, taking the lives of 20 first graders and six adults, it was the first time I ever asked my editor not to travel for an assignment. I covered aspects of the story from afar, but as a mother whose daughter was the same age as those students I didn’t think I could go into that town and experience the anguish there firsthand and write dispassionately.

My children have lockdown drills, now required by Colorado law. When the shootings occurred in the Orlando nightclub and the Las Vegas concert and in Parkland, they heard about them on the radio and I had to decide how to talk about them, how to explain the inexplicable.

This week, I had to let them know that their school – along with hundreds of others in the entire Denver metro area – was closed Wednesday due to an armed 18-year-old from Florida who was at large and apparently had an “infatuation” with the Columbine shooting. She was eventually found dead by police late Wednesday morning.

My Facebook page Wednesday was filled with anguished parents worried not just about the threat of the shooter, but also how to explain the closure to their elementary-age children.

The solution that I’ve found in these situations has been to focus on the good. I’d be lying if I said I don’t experience pangs of fear as a parent, wondering what kind of world I’ve brought my children into. But I don’t want that fear to govern my life or theirs.

I was grateful, especially when they were very young, that their school explained lockdown drills as a precaution in case of mountain lions on campus. When I talk to them now about shootings, I emphasize how rare they are, even today: that it’s partly the nonstop news and the feeling of smallness to the world that makes them seem so constant.

I don’t want my children to live in an innocent bubble or think themselves invincible. And I hope they become active, engaged citizens, speaking out for change on issues they care about the way we’ve seen many Parkland students and others of that generation do. But I do want them to realize that the world isn’t all dangerous, that most people are good, that beauty and selflessness can occur alongside violence.

Thinking back to Columbine today, two decades later, I’m filled with a profound sadness not just for the students and teachers who were killed and injured that day, but also for the era that it began.

But then I think about the countless students I’ve interviewed and met over the years who have inspired me with what they’re doing to make the world a better place; my children’s friends who want to speak up and take action to combat climate change or gun violence or plastic pollution or homelessness; the Marjory Stoneman Douglas students who immediately found a voice and refused to be passive victims. We may live in an age when mass shootings are all too common, but it’s worth spending some time also celebrating the many people who are a force for good.

Tangle of church and state roils Ukraine’s Orthodox parishes

In the West, religious institutions and governments tend not to be closely aligned. But for Ukraine’s Orthodox churches, the relationship is far blurrier. And that is causing heated debates within the country’s parishes.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 10 Min. )

The idea of an independent Ukrainian church has long been a dream of Ukrainian nationalists, and it was realized just a few months ago, with the creation of the new Orthodox Church of Ukraine (OCU) in Kiev.

But the arrival of the new state-backed church has brought upheaval to Ukraine’s many Orthodox parishes, which now face a difficult, politically charged decision. They can either remain part of the traditional church, which owes spiritual allegiance to the patriarch in Moscow, or they can shift their affiliation to the OCU and break with centuries of history. The debate is forcing Ukrainians to decide which is more important: religious freedom or national identity.

“I am supposed to represent the state here, but I have no idea what to do,” says Olena Korotka, the elected head of the town council of Pylypovychi, a village divided over the fate of its church. “I don’t think this problem can solve itself. There are so many aggressive-minded people getting involved. It even causes families to quarrel. ... When people start fighting like this, nothing good comes of it.”

Tangle of church and state roils Ukraine’s Orthodox parishes

Boris Kovalchuk arrived in this small agricultural village, about 30 miles from Kiev, straight out of the Kiev Spiritual Academy 19 years ago. Since then, he has ministered to the needs of local Orthodox believers as the local priest, maintaining a spiritual tradition that has held sway on this land for centuries.

But that tradition was thrown into disarray just a few months ago, with the creation of the new Orthodox Church of Ukraine (OCU) in Kiev.

The new church, created on the basis of a charter granted by the patriarch in Constantinople and heavily backed by President Petro Poroshenko, is meant to reduce the influence of the traditional Ukrainian Orthodox Church, which owes spiritual allegiance to the patriarch in Moscow (UOC-MP). It’s an issue that is often discussed in the language of geopolitics and national aspirations, exacerbated over the past five years by Ukraine’s conflict with Russia.

But there are no Russians here in Pylypovychi, just a Ukrainian community of around 1,500 people that’s become emotionally divided over a question few here had ever thought about before, but has pitted neighbor against neighbor. Should the village’s little onion-domed church – its first since the Bolsheviks destroyed the previous one in 1932 – retain its traditional spiritual affiliation, or should it shift to the newly created one?

The debate, which is now coming to a head in communities across Ukraine, is forcing Ukrainians to decide which is more important: religious tradition and freedom, or national identity.

For Father Boris, faith wins out. “We are all citizens of the same country, Ukraine,” he says. “We want to see our country prosperous, democratic, and successful. But Christian believers do not see living in this land as their final purpose. It’s just a step on our journey to God. The present message of the Ukrainian state is that we must sacrifice God to the interests of the state.”

‘Without an independent church, the state can’t survive’

This conflict has been brewing for centuries. The idea of an autocephalous, or independent, Ukrainian church has long been a dream of Ukrainian nationalists. After Ukraine became an independent state in 1991, the local archbishop of Kiev, Metropolitan Filaret, declared an independent Ukrainian Orthodox Church with a Kiev patriarch – himself – and began to gather parishes into it, mainly in the more nationalistic west of the country.

The struggle became more intense following the Maidan Revolution, Russia’s illegal annexation of Crimea, and the Russian-backed separatist war in Ukraine’s east. Patriarch Filaret accused the UOC-MP of being a Russian fifth column and declared that his church was the only truly Ukrainian one.

Since Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014, and Moscow’s support for east Ukrainian rebels, passions have surged, with Patriarch Filaret and others arguing that it is absolutely unacceptable for any Ukrainians to belong to a church whose center is located in the “aggressor state.”

Patriarch Filaret says he now feels vindicated. His church, long unrecognized in the Orthodox world, has been made canonical, meaning legal, by the charter issued late last year by Patriarch Bartholomew of Constantinople, who is considered “first among equals” in the global Orthodox community. Last December, Patriarch Filaret agreed to fold his Ukrainian Orthodox Church [Kiev Patriarchate], which had about 5,000 parishes, into the new entity, along with another much smaller independent Orthodox Church.

The personal cost for Patriarch Filaret has been high, since the edict from Constantinople does not allow for the new Ukrainian church to have its own patriarch. He has basically stepped aside, and the new church is headed by a young associate, Metropolitan Epiphanius. But the elder leader, now styled Honorary Patriarch Filaret by members of the new church, still holds court in his lavish Kiev mansion and remains active and very combative.

“We have entered a new period, where the task is to unite all the Ukrainian Orthodox faithful into one church,” he says. “But the process is painful. There is big resistance from Moscow. But if God blessed Ukraine to become an independent state, we are sure he also gave his blessing to an independent church. Without an independent church, the state can’t survive.”

Unlike many church people on both sides of the conflict, Patriarch Filaret doesn’t mince words when it comes to the geopolitical implications of his struggle.

“Ukraine needs to remain separate from Russia,” he says. “Russia is the aggressor country. Without Ukraine, Russia will never be a strong state. Europe understands that, so does the U.S. We don’t want to return to union with Russia. We have chosen the path joining Europe, the EU, and NATO.”

The handmaiden of the state

There are 14 separate Orthodox communities in the world, in countries like Greece, Georgia, Bulgaria, even Poland, most of which have their own spiritual head, or patriarch. Patriarch Filaret says that when all Ukrainian believers are united in one church, Ukraine will be able to be completely independent under its own spiritual leader too.

But there are no doctrinal or theological differences between Ukraine’s various Orthodox churches. And the UOC-MP insists it is completely autonomous, having no financial or organizational links with the Russian Orthodox Church other than the spiritual recognition of the Moscow patriarch.

John Sydor, spokesperson for the new OCU – which is headquartered in Kiev’s beautiful St. Michael’s Golden-Domed Monastery – says there are three key differences between it and the UOC-MP. First, it will have its administrative center in Kiev, not Moscow. Second, the language of church services will be Ukrainian – although, he admits, temporary exceptions might have to be made in a country where almost half the population uses Russian as its first language. Third, he says, it will have a pro-Ukrainian ideology.

“An independent state should have an independent church,” says Father John. “The other church sees itself as part of the Russian World. Priests of the other church often say we are all brothers, one united people, we just believe in different states. ... As there cannot be two different states on the territory of Ukraine, there cannot be two Orthodox churches.”

This discussion may sound odd to members of other religions, who usually don’t connect their faith directly with any particular government. But the Russian Orthodox Church, historically, has been the handmaiden of the state, and Ukrainian nationalists seem to be taking a mirror-image attitude.

“In the Orthodox world, there is no pope. There is no united Orthodox center, as there is in Catholicism,” says Yevgeny Kharkovchenko, a professor of religious studies at Kiev’s Taras Shevchenko University. “In the Orthodox world, church leaders are under the leaders of the state. ... In Ukraine, the religion issue is increasingly being seen as a factor of national security. For a long time now this Moscow Patriarchate church has been discussed by patriotic intelligentsia as a kind of fifth column. It brings the idea of the Russian World into the heart of Ukrainian communities.”

Asked about that, Olena Korotka, the elected head of Pylypovychi’s town council, looks shocked. “There are no enemies in this village, and we are not going to go looking for any,” she said. “We have no questions about our priest.”

Congregation vs. community

That may not be true of everyone in the village, based on what Father Boris says.

“People are accusing us of buying bullets for separatists, taking orders from Moscow, and other absurd things,” he says. He stubbornly rejects calls to join the OCU, saying that outside political activists are trying to interfere in religious affairs. “We have nothing to do with Moscow, and we don’t go in for politics. We have always tried to be a unifying influence in this community.”

Father Boris is almost unanimously backed by the group of 27 registered parishioners, the most regular and devout church-goers, and he believes Ukrainian law supports this position. “We belong to the recognized church, the church we have always been part of. These schismatics are demanding that we pass into a new church, one that is not recognized. I see none of God’s energy in this endeavor.”

On the other side are many local people who believe that since Ukraine has now been granted the right to have its own independent church, free from the Moscow Patriarchate, their local church ought to affiliate with it. They held a meeting last month, attended by around 200 people, that voted to do just that. They also took up a petition that garnered about 250 signatures.

Father Boris’s parishioners launched a rival petition that got 210 signatures. Father Boris claims outside political forces are artificially dividing the community, and that many local people who hardly ever go to church are trying to determine spiritual life for those who have made the church the center of their lives.

The chief organizer of the public meeting that voted to transfer to the new church declined to talk to the Monitor, saying he has not had good experiences with journalists. But Ms. Korotka, the town council head, says she is completely baffled by the struggle that has erupted in her formerly quiet and peaceful community.

“I am supposed to represent the state here, but I have no idea what to do,” she says. “I don’t think this problem can solve itself. There are so many aggressive-minded people getting involved. It even causes families to quarrel. We like our priest. He’s invested so much here, and we don’t want him to leave. Maybe if some people want a new church, they should go and build one? There should be peace. When people start fighting like this, nothing good comes of it.”

‘There are no Russians here’

The administrative center of the UOC-MP is in Kiev, not Moscow. It occupies the magnificent, thousand-year-old Kiev Pechersk Lavra, also known as the Monastery of the Caves, one of the most sacred sites in Orthodoxy. Unlike local parish churches, the Lavra and other major religious sites are state property. There have already been rumblings in Ukraine’s parliament about evicting the church from this prestigious perch.

The position of the UOC-MP would appear to be commanding. It administers about 13,000 parishes across Ukraine, mainly in the center and east of the country, which is about twice as many as the OCU can lay claim to. It is headed by Metropolitan Onufriy, a Ukrainian, and insists that it is completely independent and self-governing in all but spiritual matters, where it defers to the patriarch in Moscow.

But the mood at the Lavra is beleaguered. For one thing, a law recently passed will force it to change its name to something like the Russian Orthodox Church in Ukraine, thus yielding the coveted name of “Ukrainian Orthodox Church” to the new entity.

Another worry is that Ukrainian legislators may soon clear up the ambiguity in Ukrainian law over whether the affiliation of a local church is to be decided by its core parishioners or the entire population of a community, whether they are regular church-goers or not. That holds dire implications for Father Boris in Pylypovychi, who has vowed to leave rather than switch his allegiance.

“We are looking at a situation where the 70% of people who don’t go to church will be deciding for those who do where they should go to pray,” says Alexander Bakhov, head of the UOC-MP’s legal department.

“This situation has arisen because the head of state, President Poroshenko, turned to the patriarch in Constantinople to give autocephaly to the schismatics. It’s problematic, because it is not clear that the Constantinople patriarch has the power to do this. It would be one thing if there was just one Orthodox church in the country, and they turned to Constantinople to make it canonical [legal]. But in this case, two groups of schismatics, supported by the head of state, made these moves,” Father Alexander says.

“We are the largest church in the country, yet the state initiated this issue, and is interfering in our affairs. For example, our priests are barred from ministering to soldiers in the Army. Our believers are everywhere, why are they denied their rights? The purpose here is to pin the image of an enemy upon us in order to destroy us. But this is strictly an issue between Ukrainian believers. There are no Russians here.”

Everyone agrees that the coming parish-by-parish battles for control should remain peaceful. But Patriarch Filaret says he is in no doubt about the final outcome.

“Of course we know that not all are ready to join our church. But conflicts in villages, even when they happen, are an exception. They should not happen,” he says. “People have to choose for themselves. Which church do they want to belong to? The Ukrainian Orthodox Church, or the Russian Orthodox Church in Ukraine? If they want to belong to a Russian church, they have the right. But if Ukrainians want to belong to a Ukrainian church, they need to leave that Russian one. We believe the majority of Ukrainians will make the right choice.”

The Explainer

Should the census ask about citizenship? Supreme Court to weigh in.

Some U.S. officials want the next census to give a reliable count of voting-age citizens, and of noncitizen immigrants in the country. Is a citizenship question constitutional?

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

Last year, Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross announced he would reinstate a citizenship question for the 2020 census. The U.S. Census Bureau, a nonpartisan agency, has not asked the question on the decennial census since 1950. But Mr. Ross indicated he was reinstating it after the Department of Justice said it needed “a reliable calculation of the citizen voting-age population” to better enforce the Voting Rights Act.

Several states and nonprofit groups have challenged the move and federal judges in New York, Maryland, and California have ruled in favor of those challengers. The U.S. Supreme Court will hear the case on April 23.

A striking feature of this case is that Mr. Ross decided to reinstate a citizenship question despite the Census Bureau itself recommending otherwise. Research by the bureau found that the question would decrease responses from noncitizen households by at least 5.8%, leading to an undercount of approximately 6.5 million people – about the population of Tennessee.

Although the potential consequences of having a citizenship question in the 2020 census will be a factor, ultimately the justices will be focusing on broader questions about the power of executive branch agencies and whether adding the question is constitutional.

Should the census ask about citizenship? Supreme Court to weigh in.

On April 23, the high court will weigh whether Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross acted lawfully in deciding to reinstate a citizenship question in the census.

How did we get here?

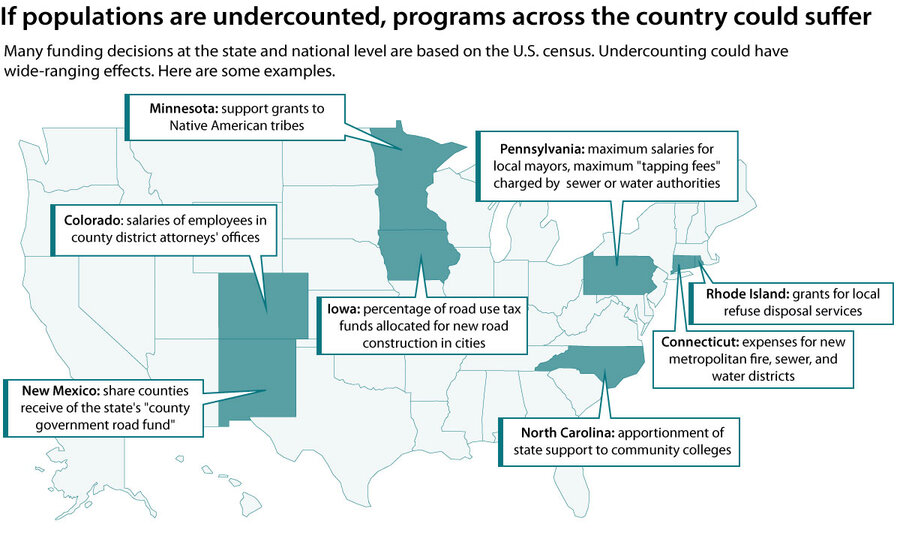

Required by the Constitution, an “enumeration” of all people living in the United States has been performed every 10 years since 1790. The data is used to calibrate most social and economic surveys in the U.S., and to determine everything from the amounts of federal funding for states to representation in Congress.

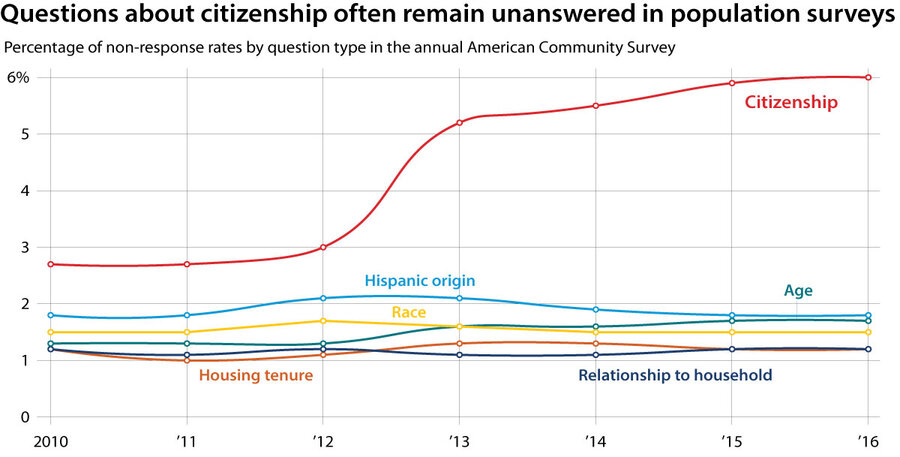

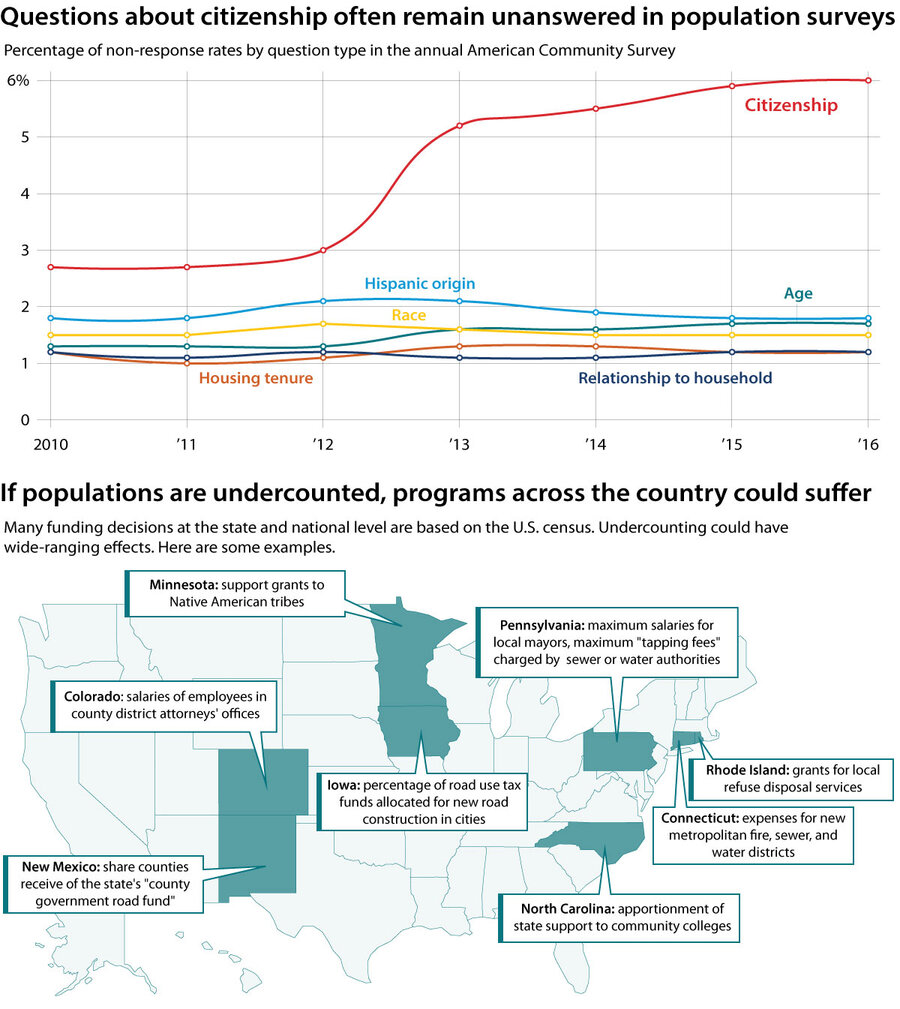

Last year, Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross announced he would reinstate a citizenship question for the 2020 census. The U.S. Census Bureau, a nonpartisan agency, has not asked the question on the decennial census since 1950 (though it has asked a small subset of the population in the annual American Community Survey). But Mr. Ross indicated he was reinstating it after the Department of Justice said it needed “a reliable calculation of the citizen voting-age population” to better enforce the Voting Rights Act.

Several states and nonprofit groups filed lawsuits challenging the move, and in mid-January a 277-page opinion from a federal judge in New York ruled that Mr. Ross had violated the Administrative Procedure Act (APA), in part by using a pretextual reason for reinstating the question. Then, in early March a federal judge in California ruled that a citizenship question was also unconstitutional. A federal judge in Maryland found the same in early April.

The Supreme Court had been set to hear a case on the citizenship question in February – regarding whether Mr. Ross could be deposed – but it was removed from the calendar after the ruling in New York. A month later, however, the case was put back on the docket. Now the justices will be deciding whether the lower court judges erred in their rulings, whether the decision to add a citizenship question is constitutional, and whether this question will be in next year’s census.

U.S. census, American Community Survey Item Allocation Rates

How would a citizenship question affect the census?

A striking feature of this case is that Mr. Ross decided to reinstate a citizenship question despite the Census Bureau itself recommending otherwise. Research by the bureau found that the question would decrease responses from noncitizen households by at least 5.8%, leading to an undercount of approximately 6.5 million people – about the population of Tennessee.

An undercount of that size could mean that a half-dozen states, including California, Texas, and Florida, would lose congressional seats and Electoral College votes. Also, it would jeopardize hundreds of billions of dollars in federal funding to states for services that are used by all, such as health care and infrastructure.

“I think people have misunderstood the likely impact,” says Justin Levitt, a professor at Loyola Law School in Los Angeles. “Immigrant and minority communities [will be affected], but so will everyone around them.”

United States District Judge Jesse M. Furman, Southern District of New York, Jan. 15, 2019

What is the Supreme Court interested in?

Although the potential consequences of having a citizenship question in the 2020 census will be a factor, ultimately the justices will be focusing on broader questions about constitutionality and the power of executive branch agencies.

Last fall, when the court issued an order halting Mr. Ross’ deposition, Justice Neil Gorsuch wrote in a partial dissent that the entire trial in New York should be halted. “There’s nothing unusual about a new Cabinet secretary coming to office inclined to favor a different policy direction,” he added.

But the trial did go ahead, with a supplemental memorandum in which Mr. Ross acknowledged that “[s]oon after [his] appointment as Secretary of Commerce,” he had begun considering “whether to reinstate a citizenship question.”

This, among other actions, amounted to “a veritable smorgasbord of classic, clear-cut APA violations,” the federal judge in New York ruled.

The court has typically been forgiving of agencies changing policies as long as they do their homework first, Professor Levitt says.

“This might be one of the rare instances where the court says the legal standards are very low,” he adds, but “the Commerce Department tripped over that low bar.”

Where does the 2020 census stand?

The Supreme Court case was fast-tracked to meet a June deadline to finalize the census form. The questionnaires will be printed this summer, and the official start of the census is set for Jan. 21 in Toksook Bay, Alaska.

Most households will be able to begin participating in mid-March, and all will have the opportunity to submit responses online.

U.S. census; American Community Survey Item Allocation Rates; United States District Judge Jesse M. Furman, Southern District of New York, Jan. 15, 2019

How to defy apartheid? For journalist Juby Mayet, with pen in hand.

Journalists do more than record the world. Sometimes, they help make it turn. In apartheid South Africa, simply writing about black communities in all their vibrance was an act of protest.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

To Juby Mayet, a South African journalist, the news hardly needed sensationalizing. Apartheid was absurd enough, she reasoned. All you had to do was write it down.

Ms. Mayet, who died Saturday, wrote for some of South Africa’s most influential publications in the 1960s and ’70s, capturing black life under apartheid in bright color. It was a simple rebellion to the regime – giving texture, shape, and joy to the very worlds apartheid was trying to flatten. It was a flattening she knew too well.

Her family was uprooted from their house in central Johannesburg and sent 20 miles south, to a newly designated Indian suburb. But Ms. Mayet wasn’t actually Indian, but Malay, and she eventually had her race formally “reclassified” to avoid being separated from her children – the ultimate absurdity for a woman who lived her entire life resisting apartheid’s categories.

But as apartheid’s reach advanced, journalists who exposed the system’s strange rules were increasingly targeted. In 1978, Ms. Mayet was imprisoned for five months and then banned from publishing for five years. Yet her career stands as a reminder that it was possible to live a life bigger than your circumstances were supposed to allow.

How to defy apartheid? For journalist Juby Mayet, with pen in hand.

The woman wasn’t talking.

At least, that’s what the other reporters told young journalist Juby Mayet when she arrived at a Johannesburg apartment door in the late 1950s, hoping for a scoop that would impress her editors.

The woman behind the door was white. Her husband was Indian. A few days earlier, they’d been charged with breaking apartheid’s Immorality Act, which forbade romantic relationships across South Africa’s color line.

Ms. Mayet was supposed to get their story. She walked past the knot of white journalists who’d told her not to bother and knocked.

“Who is it?” asked a voice inside.

“Sharon, from Golden City Post.” Ms. Mayet offered her pen name. The door swung open, and a hand yanked her inside. Then it snapped shut against the gaggle of stunned reporters.

The woman later told Ms. Mayet she’d given her the story because she had read her reporting and knew “you wouldn’t sensationalize our situation.”

That was the way Ms. Mayet saw journalism. Apartheid was absurd enough. All you had to do to show that was to write it down.

And she did. As a reporter for some of South Africa’s most influential publications in the 1960s and ’70s, Ms. Mayet, who died Saturday, wrote stories that captured black life under apartheid in bright color. This simple rebellion was also a dangerous one – giving texture, shape, and joy to the very worlds apartheid was trying to flatten.

On the staff of the Golden City Post, Drum, and other iconic black newspapers and magazines, Ms. Mayet wrote with equal respect about jazz concerts and soup recipes, about crime and the Immorality Act, about the forced removal of millions of black South Africans from their land and, as an advice columnist, the love stories, family dramas, and personal betrayals that coursed below the surface of those big-picture stories.

“She was right there with the likes of South Africa’s great journalists at a time when journalists were really freedom activists. And on top of it she was a woman,” says Mary Papayya, a board member of the South African Broadcast Corporation and the media freedom chair for the South African National Editors Forum.

Ms. Mayet lived a life to match, one where freedom was never a distant speck on the horizon, but something you seized each day – one story, one multiracial friendship, one dark joke about apartheid at a time.

“I was never a political person,” Ms. Mayet told me in a 2011 interview. “But … in this country the mere fact that you are not white politicizes your life. You are not white so you can’t travel in that train … your children can’t go to that school. So what else can you be but political?”

What else could you be but political, either, as a woman in a world custom-built for men, where important career wisdom was shared in smoky bars, and getting the girl often seemed as important as getting the story?

But Ms. Mayet’s brand of gender equality, those who knew her say, was never about soapboxes or philosophical arguments.

She let men know she was their equal by being their equal. (And in her hard-drinking circles, she told me, that meant showing “I could also drink most of them under the table.”)

“Juby looked after herself and she had a sharp tongue for anyone who tried to stand in her way, whether it was the police or thugs she met in the road or her own colleagues,” says her friend and colleague Joe Thloloe.

Living outside the box

Ms. Mayet was born in 1937 in Fietas, a multiracial working-class neighborhood of Johannesburg before apartheid cleared those pockets of diversity off the map.

In 1957, she shocked her parents by finishing teaching college and marching straight into the offices of a popular newspaper called the Golden City Post, where she’d been covertly writing articles for months.

Like many black journalists of her generation, Ms. Mayet flouted apartheid’s rules whenever she could.

“I must tell you, that during my years as a reporter I had great fun, because it was so nice to poke fun at the system, to dodge them, to quarrel [with them], to slam doors in their faces,” Ms. Mayet told a South African talk show in 2016.

In the mid-1960s, her family was uprooted from their house in central Johannesburg and sent to live 20 miles south of the city, in a newly designated Indian suburb called Lenasia.

But Ms. Mayet wasn’t actually Indian, but Malay. After her husband died in a car crash, she had her race formally “reclassified” to avoid being separated from her children – the ultimate absurdity for a woman who lived her entire life resisting apartheid’s categories.

As apartheid’s reach advanced across the 1960s and ’70s, journalists like Ms. Mayet who exposed the system’s strange rules were increasingly targeted.

“The whites in this country never really regarded black people as fully human. They thought we … didn’t have ideas. We didn’t feel wronged [by their system],” Ms. Mayet said in 2011. “But when they started to realize that [black] people were reading the newspapers … and thinking for themselves – that’s when they started to really get nervous.”

By the mid-1970s, many of her colleagues from Drum and Golden City Post were in exile or prison. Meanwhile, she became a founding member of the first union for black journalists in the country. She worked there until 1978, when she was jailed for charges related to her activism. Released five months later, she was banned from the union and prohibited from publishing for five years.

So Ms. Mayet did the pragmatic thing for a single mother with eight children. She quit journalism and became a cleaner and a secretary, waiting out apartheid’s final decade on the fringes of the world she’d spent her career fighting for a place in. Yet her career stands as a reminder that it was possible to live a life bigger than your circumstances were supposed to allow.

“She was feisty and she was not what anyone expected her to be – I think she laid the foundation for black women journalists in South Africa,” says Khadija Patel, the editor of the Mail & Guardian newspaper. “She refused to be fitted into a box.”

In Jordan, a place for animals to forget the trauma of war

Even after violence stops, the physical and mental costs of war can endure. Well documented in people, it is true for animals as well. Our reporter visited with animals recovering from Mideast conflicts.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

-

By Taylor Luck Correspondent

At the Al Ma’wa Wildlife Reserve in Jordan, 30 miles northwest of Amman, the forgotten victims of the Middle East’s wars are being provided with a place to recover and forget. On a sleepy hill of oak and pine overlooking the olive groves and apple orchards of Jerash, pairs of large eyes gleam from the brush. Lions, tigers, and bears.

When rescued from conflict zones, the animals are often in a near-critical condition, burned, scarred, and emaciated. Special diets restore them physically. But Al Ma’wa staff also help the victims of mental trauma, including lions and bears from Aleppo, Syria, that shiver with fear in their shelters for hours at the sound of a passing plane.

Among the methods: introducing a rotation of pleasurable but unusual scents to their habitats that keep their olfactory senses engaged, and a series of new games and toys to keep their minds active. Says Saif al-Rawashdeh, lead animal keeper and supervisor at Al Ma’wa: “Our care is based on one approach: How can we get the animals to forget what they have been through?”

In Jordan, a place for animals to forget the trauma of war

Hamzeh has begun to build a new life in northern Jordan two years after fleeing his war-torn home country of Syria.

Like many of the 1.2 million Syrians who have sought refuge in Jordan since 2012, Hamzeh has been given shelter and adjusted to a new climate and cuisine. He has enjoyed the hospitality of Jordanians, who have donated food and toys, and has even made dozens of Jordanian friends.

But one thing separates Hamzeh from the hundreds of thousands of Syrians who now call Jordan home: Hamzeh is a lion.

At the Al Ma’wa Wildlife Reserve, 30 miles northwest of Amman, Jordan and wildlife advocates are providing both a home and hope for the forgotten victims of the region’s wars: endangered wildlife.

On a sleepy hill of oak and pine trees overlooking the olive groves and apple orchards of Jerash, a low rumble fills the air as pairs of large eyes gleam from the brush. Lions. Tigers. Bears. The large animals, some of them thousands of miles from their natural habitats, quickly make it known that these ancient woods popular with hikers and Friday picnickers are their home.

The sanctuary, which rescues, rehabilitates, and houses wildlife from the region’s wars, is a joint initiative by the Princess Alia Foundation, a conservation and development NGO founded by a member of the Hashemite royal family, and Four Paws, a Vienna-based international animal welfare organization.

Since 2016, Al Ma’wa staff have been healing and rehabilitating 26 animals rescued from local zoos, smugglers, and Jordan’s war-torn neighbors: lions from Aleppo, Syria; a bear from Mosul, Iraq; lion cubs from Gaza.

‘Statement’ pets

Here on a 250-acre lot donated by the Jordanian Agriculture Ministry, Al Ma’wa has built spacious habitats for the large cats and bears, allowing them acres to roam freely for the first time in their lives.

The idea of the reserve came in 2011, when the Princess Alia Foundation looked to find a home for rescued large wildlife, particularly Balou, a brown bear taken from a poorly run private zoo in Amman.

The location of the sanctuary is convenient. Jordan lies at the heart of wildlife smuggling routes, through which exotic animals from North Africa, breeders, or private zoos are sold off to wealthy individuals in neighboring Saudi Arabia who are looking for a “statement” pet.

Jordanian authorities had previously caught tiger cubs hidden in shoeboxes under the driver’s seat of a car heading to Saudi Arabia, pythons hidden in suitcases, and individuals posting lion cubs for sale on Facebook.

But with ongoing violence in Syria, Iraq, and Gaza leaving hundreds of zoo animals unfed, ill, and abandoned, Al Ma’wa also set its sights on rescuing animals, becoming the region’s first animal refugee camp.

Psychological wounds

Once Four Paws rescues the furry guests from conflict zones and transports them to Jordan, their health is often in a near-critical condition: lions and bears with burn marks and scars on their faces; skinny-bordering-on-emaciated bodies, with ribs bulging through their sagging skin; cheeks and eyes sunken into their skulls.

Al Ma’wa health experts provide the rescued animals with vitamins and special diets of lamb carcasses, fruit, and even rice and pasta to restore them physically.

But more than simply provide medical care and food, Al Ma’wa staff help the animals heal from the traumas of war.

“Our care is based on one approach: How can we get the animals to forget what they have been through?” says Saif al-Rawashdeh, lead animal keeper and supervisor at Al Ma’wa.

For weeks after their arrival, staff say, the rescued animals exhibit “aggressive” behavior, constantly screaming and howling, or throwing their bodies against the gates in protest.

Yet other trauma-induced behavior lasts longer.

When planes roared overhead, the bears and lions from Aleppo would race for cover and spend hours in their night-shelters, shivering with a fear instilled by the destruction of President Bashar al-Assad’s warplanes and barrel bombs.

It is a trauma shared by hundreds if not thousands of Syrian children, who according to refugee advocates and Jordanian school teachers, suffer similar post-traumatic stress episodes from planes for several months after arriving in Jordan.

Learning to forget

The sound of a car engine and the approach of a vehicle would also cause the animals to run in fright or become aggressive, reliving the trauma of militias’ trucks, or wildlife smugglers. The presence of a stranger would send the animals scampering.

In order to get the animals acclimated to the sanctuary’s vehicles delivering pounds of meat and fruit for their meals, reserve staff would approach the habitats slowly in their trucks, parking at progressively shorter distances – 50 meters away, 40, 30, 20, 10 – until the animals learned that the trucks were not a threat, but a sign that a meal was coming.

Another key component to their rehabilitation is a rotation of pleasurable but unusual scents in their habitats, such as cinnamon and various perfumes, keeping their olfactory senses engaged, and a series of new games and toys to keep their minds active.

“Every time we give them toys, scents, activities, and games, their minds are busy and it slowly helps them forget,” Mr. al-Rawashdeh says.

Open to the public, Al Ma’wa receives up to 1,000 visitors on guided tours each week, including dozens of schoolchildren on field trips.

This summer, the reserve is set to open an education center to teach visitors the importance of caring for wildlife and nature, in addition to a restaurant and lodges overlooking the habitats for guests wishing to spend the night.

There are many signs that after two years guests at Al Ma’wa are feeling right at home – and no longer fear the presence of humans.

Loz, a playful Asian black bear rescued from Aleppo in 2017, pops his head in and out of his night-room, playing a game of “peekaboo” with Mr. al-Rawashdeh and a reporter, opening his mouth wide in what could only be described as a mischievous smile.

Having finished her lunch, Halab, a lioness from Syria, rolls onto her back, lying belly up in the sun a few inches away from the gate for a post-meal nap – like a kitten asking to be petted.

Max, another lion, walks toward the edge of the gate, and, facing the reporter, calmly sits down without a sound, attentive and curious.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

A planeful of truth lands in Venezuela

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

In a display of truth triumphing over a lie, an airplane from the Red Cross flew 24 tons of aid to Venezuela on Tuesday. Its arrival in Caracas marked an end to years of denial by President Nicolás Maduro that his country is in a crisis and his claims that it doesn’t need such foreign aid. Just last February the embattled leader said reports of a crisis were simply a “show.”

Mr. Maduro has been reluctant to admit his socialist ideology has failed. He also did not want neutral groups like the Red Cross delivering aid directly to the people. He controls the poor by doling out basic necessities. His about-face could be explained by the expectation that the economy will shrink a further 25% this year.

In recent weeks, the United Nations was able to persuade Mr. Maduro that aid groups must be allowed to operate independently. This first shipment will be a test of the regime’s willingness to let aid be provided based on the humanitarian principle of political neutrality. Yet just as important as the aid is that Venezuelans now have seen their leader exposed in a lie.

A planeful of truth lands in Venezuela

In a display of truth triumphing over a lie, an airplane from the Red Cross flew 24 tons of emergency aid to Venezuela on Tuesday. Its arrival in Caracas marked an end to years of denial by President Nicolás Maduro that his country is in a humanitarian crisis and that it doesn’t need such foreign aid. Just last February the embattled leader said reports of a health and food crisis were simply a “show” sponsored by the United States. “We aren’t beggars,” Mr. Maduro said.

Such lies about Venezuela’s crisis were obvious to the rest of the world as well as Venezuelans, millions of whom are malnourished or have fled the country. Yet until now, Mr. Maduro has been reluctant to admit his socialist ideology has failed in a country once flush with oil wealth. He also did not want neutral groups like the Red Cross delivering aid directly to the people. He controls the poor by doling out basic necessities to ensure their loyalty.

His about-face could be explained by the expectation that the economy will shrink a further 25% this year, a result of mismanagement that has led to hyperinflation and massive blackouts. And the dire circumstances could mean more members of the military might defect to the opposition led by Juan Guaidó, who was declared president two months ago by the National Assembly. Mr. Guaidó, whose legitimacy is recognized by most Western governments, has campaigned to bring aid into Venezuela.

In recent weeks, the United Nations and the International Committee of the Red Cross were able to persuade Maduro that aid groups must be allowed to operate independently in delivering supplies. The U.N. estimates a quarter of the population needs urgent aid while other observers say the health system has “utterly collapsed.”

This first shipment from the Red Cross will be a test of the regime’s willingness to let aid be provided based on the humanitarian principle of political neutrality. Yet just as important as the aid is that Venezuelans now have seen their leader exposed in a lie.

The power of truth-telling against dictatorships is well recorded in history. The late Soviet dissident Alexander Solzhenitsyn, author of books that depicted unpleasant truths about communist rule, asked people to never knowingly support official lies. “One word of truth outweighs the whole world,” he said, while adding that truth is based on “an unchanging Higher Power above us.”

The truth about Venezuela’s needs, combined with the humanitarian impulse of the international community, has finally caught up with the Maduro regime. It arrived Tuesday on an airport tarmac.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

If you’re tempted to cheat

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Lizzie Witney

When opportunities arose to cheat on an exam, today’s contributor, who’d been struggling at school, was tempted. Instead, considering God as the source of limitless intelligence inspired her to take the honest path and ultimately find that “putting our trust in God always gives us what we need – without cheating.”

If you’re tempted to cheat

While I was in high school, my family moved from our home in England to another country for a year. This meant a change to what I was learning in school, and I found myself falling way behind, as I didn’t have the same academic background as my new schoolmates.

I worked so hard to get my grades up, but I was barely passing most classes, and a countrywide exam was coming up. Exhausted, I knew something had to change.

I began to pray, which I’d found helpful in tough situations before. One evening I came across these words that God speaks to Joshua in the Bible: “As I was with Moses, so I will be with thee: I will not fail thee, nor forsake thee” (Joshua 1:5). I thought of what I knew of the story of Moses, which included bringing the Israelites out of slavery, parting the Red Sea, and supplying food and water in the desert.

I realized that if Moses could depend on God for all that, certainly I could rely on Him too. God’s nature is infinite, which means that He provides us with all we need, including intelligence, guidance, peace, and clarity.

Before the exam, as I sat on a staircase to study, I overheard some of my peers talking about an aspect of the subject I didn’t know anything about. I asked if they could explain it to me, and they did.

After we spoke, I sat outside a classroom to study further. In the classroom were two more of my friends talking about something else I had no recollection of learning, so I asked them about it. By this time, I was pretty excited. I had been praying for God’s guidance, and here it was, coming to me in the most unexpected way. After that, I went and found another place to study and again had a similar interaction.

When I sat down to take the exam, I noticed that all of the things I’d learned just minutes before were on the test. This totally removed any fear of failure. I felt I’d glimpsed the truth of this statement by Mary Baker Eddy, the discoverer of Christian Science: “Divine Love always has met and always will meet every human need” (“Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” p. 494).

Partway through the exam, the teacher left the room. My peers started talking among themselves to try to figure out the correct answers. The thought came to me, “It’s not your fault if you overhear something you’re not meant to!” There were still a few questions I was struggling with, and I was tempted to believe that maybe this was another way God was helping me out.

However, I recalled that in Christian Science another name for God is Truth. Divine Truth could never work through dishonesty. Science and Health explains: “Honesty is spiritual power. Dishonesty is human weakness, which forfeits divine help” (p. 453). With that, the temptation to cheat left, and I made a conscious effort to tune out my classmates’ discussion.

Minutes before the exam was to end, the teacher, who had at this point returned to the classroom, offered us extra time to finish the test. Again, I recognized this as dishonest (this was a countrywide exam in which every student was supposed to be taking the exam under the same conditions), so even though I felt as if I could do with some extra time, I stood up at the end of the hour and walked out of the room, alone.

The feeling of divine Love loving me that I experienced when I left the classroom was such a sweet, powerful reassurance that I had done the right thing.

Later, I found out that I’d passed the test with a better grade than I expected. More important, though, I gained a deeper understanding of how putting our trust in God always gives us what we need – without cheating.

The strength of divine Truth supports each one of us in trusting God as the source of infinite intelligence, which we can never be separated from for a moment. God’s love will never fail us. As we come to understand this, the feeling that cheating is just “the norm” can fade, and there will be healing.

Adapted from an article published in the Q&A series of the Christian Science Sentinel’s online TeenConnect section, Nov. 3, 2016.

A message of love

Line dry

A look ahead

That’s our package for today. In our next Daily: For a cleaner New York Harbor, one recipe involves oysters and a leap of imagination – for residents to envision that progress is possible. See you tomorrow!