- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 9 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usMonitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

The kids on the bus

Welcome to your Monitor Daily. Today’s stories explore Pete Buttigieg‘s brand of folksy intellectualism, a proactive approach to wildfire prevention, the struggle for peace in Ukraine, a political collision over “granny flats,” and an artistic revival of a traditional Islamic document.

But first, consider the old adage: Look at the big picture. When you do, the results can sometimes be astonishing.

Take Boston, where kids are soon headed back to school. Two years ago, the school system led the nation in costs per pupil for the 25,000 who qualify for bus transportation. Children were often late, despite the annual devotion of about 10 people for a solid month to mapping each school’s bus routes.

Officials decided they needed to look at things differently. So, as Route Fifty reports, they issued a challenge to the Boston community: make it more efficient and cheaper, while still addressing everything from students’ mobility needs to different school start times to very narrow roads.

Two Ph.D. candidates at MIT stepped up, devoting hundreds of hours to the “bold and unusual” request. And their resulting algorithm literally changed the perspective, swapping a focus from each school’s individual routing needs to a more fluid routing system. Routes became 20% more efficient. That meant 50 fewer buses, 1 million fewer miles of driving, 20,000 fewer pounds of CO2 emissions daily, and $5 million more for classrooms. Bonus: Walking and riding times didn’t increase.

There’s another old adage: It takes a village to raise a child. In this case, the village grew out of a commitment to “reinvest in schools and improve the student experience.” And the kids were the winners.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

A deeper look

In Iowa, Buttigieg seeks Trump voters. He may need more Democrats.

In southeastern Iowa, Pete Buttigieg’s combination of smarts and folksiness is resonating, with many voters saying they want a presidential candidate who will “look out for the common man.”

A son of the heartland and a graduate of Harvard, Mayor Pete Buttigieg of South Bend, Indiana, combines a folksy manner with intellectual firepower that elicits chuckles and cheers. Since bursting out of the gate this spring with a flood of media attention after a town hall appearance went viral, he has lately been polling in the single digits. But he has been highly successful at fundraising, which means he has the resources to make a strong showing in the crucial Iowa caucuses.

Last week, he made a swing through half a dozen Iowa counties that had voted in favor of Barack Obama, but flipped to support Donald Trump in 2016. Mr. Buttigieg, the gay Midwestern wunderkind, would like to woo those voters back.

Perhaps what most sets him apart from the large Democratic field is the way he invokes values like faith, freedom, and patriotism that have come to be seen as the province of conservatives. “American values ... are not values that belong to one party,” he tells a crowd in Ottumwa. ”They’re values that belong to all of us – but that I also believe point in a very progressive direction when we take them seriously.”

In Iowa, Buttigieg seeks Trump voters. He may need more Democrats.

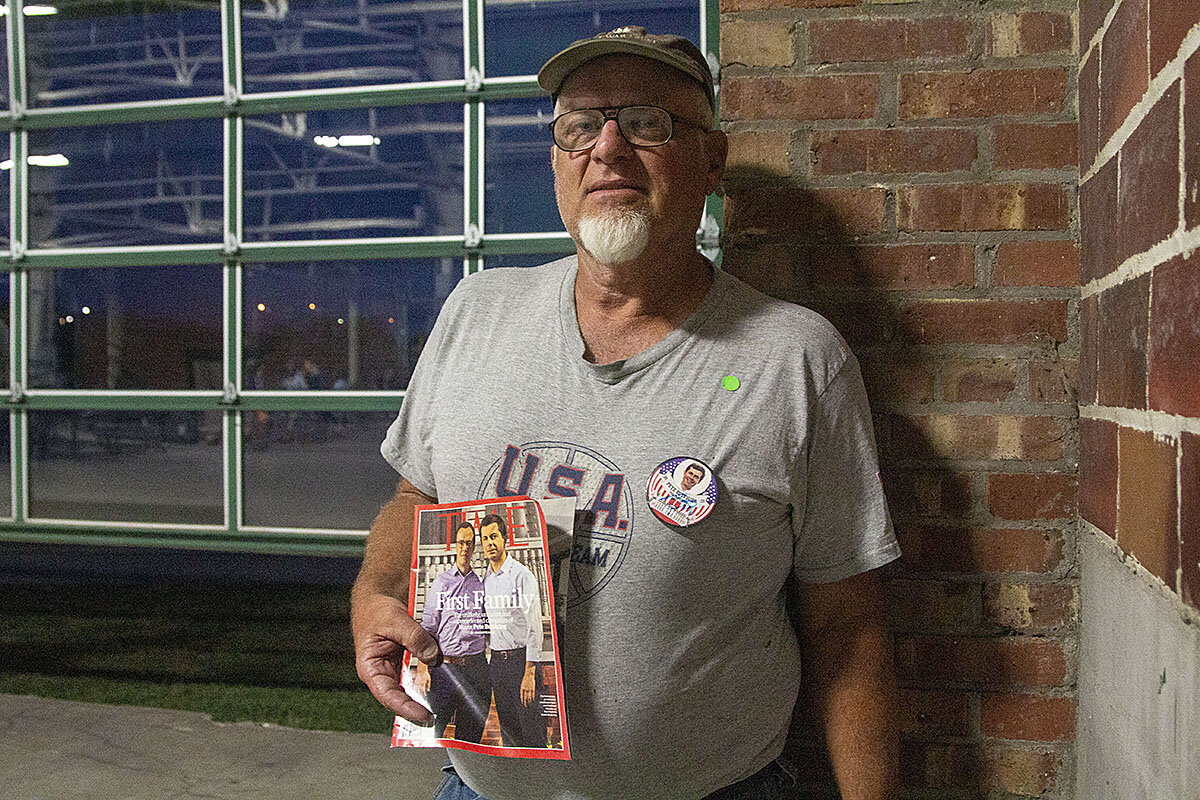

Gary Kupferschmid managed to snag the autographs of five presidential candidates in just three hours at the Iowa State Fair this month, adding to a hefty collection that includes Jimmy Carter, George W. Bush, Barack Obama, Hillary Clinton, and Donald Trump – the last of whom got his vote in 2016.

Now Mr. Kupferschmid is back in his hometown, standing on the dimly lit porch of the Port of Burlington as the Mississippi River flows by, waiting for a signature from the latest candidate to roll through.

But Mayor Pete Buttigieg is hard to get to. He is mobbed everywhere he goes in Iowa. Supporters press in, standing almost nose to nose with him, waiting for their turn to exchange a few words.

“I’m so nervous. You’re such a rock star,” gushes one woman. A man sporting a BOOT EDGE EDGE T-shirt that doubles as a pronunciation guide urges the mild-mannered mayor from South Bend, Indiana, to “do a Kamala Harris” in the next debate, referring to the California senator’s more combative approach. “Stand out!”

In the middle of it all, a little girl looks up at the youngest of the presidential candidates and says: “I hope you get to be president.”

“I hope so, too,” he responds, bending down toward her on a swing through more than half a dozen mostly rural counties after an appearance at the Iowa State Fair last week. All but one of those counties share a common characteristic: They voted in favor of Mr. Obama, but flipped to support Mr. Trump in 2016. Mr. Buttigieg, the gay Midwestern wunderkind, would like to woo them back.

“We lost an election in ’16 because, I believe, we didn’t hear that very clear message from rural people,” says Democrat Patty Judge, a former lieutenant governor and secretary of agriculture for Iowa. “They thought that Donald Trump was change, was an opportunity for them – of course that was not true. They are going again to be looking for that opportunity and change.”

She hasn’t endorsed a candidate yet, but calls Mr. Buttigieg’s new plan for rural America “very strong.” And indeed, he is positioning himself as a son of the heartland, who’s on a mission to reclaim quintessential American values like faith, freedom, and patriotism as not solely the province of the GOP. At the same time, he is deliberately redefining those values in progressive ways. He refers to Trump voters as “our friends,” and speaks of the pain of rural America and the importance of seeing it as part of the solution on everything from the economy to climate change.

Since bursting out of the gate this spring with a flood of media attention after a town hall appearance went viral, Mr. Buttigieg has lately been polling in the single digits. But he has been highly successful on the fundraising front, which means he has the resources to lay the groundwork for a strong showing in the crucial Iowa caucuses six months from now. His campaign sees southeastern Iowa as especially fertile territory, says senior communications advisor Lis Smith. They are hoping to convert Trump voters like Mr. Kupferschmid.

The message is essentially, “Look, Donald Trump talked a good game. He said he was going to go out there and fight for you, but he hasn’t,” says Ms. Smith, following the Buttigieg media mob at the state fair as he heads over to flip pork chops with the Iowa Pork Queen. “It’s not about saying that they’re complicit in a crime or that they’re horrible people for voting for him. It’s just saying, now is your chance and we will actually fight for you.”

‘Who is he?’

But first, he has to get on more people’s radar screens. Despite the intense cohort of fans who seem to follow him everywhere, plenty of Iowans still who have no idea who he is. As Mr. Buttigieg and his entourage stroll around the fairgrounds in Des Moines, they leave in their wake many puzzled expressions.

“Who is that?” asks one onlooker.

“Pete Buttigieg,” replies someone nearby.

“And who is he?” asks a third, looking confused.

“I have no clue who that is!” says a boy.

“No clue,” agrees a woman next to him.

“Go Trump!” yells someone else.

From the bowels of the beer tent, someone recognizes him, yelling, “I got your book!” One supporter offers him half a plastic cup of beer. (An aide says no thanks; it’s only mid-afternoon.) Another insists on handing him a limp chocolate chip cookie. (A staffer discreetly throws it in the next trash can.)

Mr. Buttigieg, dressed in a white shirt and jeans, takes it all in stride, never seeming ruffled or impatient. No matter what the question – Antifa, Brexit, climate change, the Hong Kong protests, Israel’s annexation of the Golan Heights, tensions in Kashmir, or his favorite subject in grade school (English) – he delivers an articulate answer with almost machine-like precision.

After traipsing all over the fairgrounds, he honors a promise made to a mother who asked him during the Q&A of his soapbox talk, “Will you ride the slide with my son?” “Of course I’ll ride the slide with your son!” he told her. “I don’t know what it means, but I’ll do it.”

And he does, high-fiving the little boy at the bottom. Then, fortified by all manner of pork, he heads off to Trump country.

“Trump is not the answer”

Burlington, Iowa, has been dubbed the Backhoe Capital of the World, and when Shearer’s is making chocolate chip cookies, the whole city smells amazing. It boasts its own Minor League baseball team, the Burlington Bees, and was the hometown of conservationist Aldo Leopold and astronaut Jim Kelley. It features hilltop Victorian mansions that can be purchased for $225,000.

But shootings are up and the population is down – the lowest it’s been in nearly a century. Employers complain that they can’t find good help. The rate of kids on free and reduced-price lunches has risen from just a few percent to more than 50% in the past few decades.

Though Burlington itself narrowly supported Mrs. Clinton, the county as a whole went for Mr. Trump. Up the river in Muscatine, it’s a similar story. Mayor Diana Broderson, sitting in the front row of an outdoor house party waiting for Mr. Buttigieg to arrive, says she wants “someone that’s looking out for the common man.”

Last time around, some supporters of Sen. Bernie Sanders – upset that he had lost the nomination to Mrs. Clinton – backed Mr. Trump instead. “I’m hoping that everybody has learned that our party has to be united,” says Ms. Broderson. “A great number of people in our community agree that Trump is not the answer.”

Kelcey Brackett, the Democratic chairman in Muscatine County, says he believes some Trump voters could go for Senator Sanders if he became the Democratic nominee. Other candidates, such as Sens. Cory Booker of New Jersey and Amy Klobuchar of Minnesota, could also win them over by setting a tone of bipartisanship. “I do think that’s important,” says Mr. Brackett, adding that there is also high enthusiasm for Mr. Buttigieg, who drew 225 people to the Muscatine house party on a weekday afternoon. “Otherwise the pendulum is just going to swing harder.”

In the lush backyard, Mr. Buttigieg is introduced as being, among other things, Maltese-American, left-handed, and a didgeridoo player. As at nearly every campaign stop, he receives a standing ovation before he even opens his mouth. A Harvard graduate and Rhodes scholar, “Mayor Pete” combines intellectual firepower with a folksy manner that elicits chuckles and cheers over even the driest topics.

“Basically, I want to Marie Kondo the bureaucratic process,” he says, referring to the bestselling Japanese decluttering expert who has encouraged millions to empty their closets of anything that doesn’t “spark joy.”

Tongue in cheek, he describes his own memoir, “Shortest Way Home,” featuring “a daring young mayor who has a vision for the future of his community.” “It’s sorta how we’re paying off the wedding bill, so I’d be very grateful if you’d pick one up,” says Mr. Buttigieg, who married his husband last summer, and carries household student debt in the six figures. Forbes recently ranked him as the poorest presidential candidate, with a net worth of $100,000. But he has 23 billionaires backing his campaign, the most of any candidate. He has 60 full-time staffers in Iowa.

Campaign finance is “one of my favorites,” he says in response to a question, boiling the issue down to a simple equation: It’s not a democracy, he says, if dollars can outvote people. If Citizens United, the landmark 2010 Supreme Court decision, can’t be overturned, he adds, Congress should pass a constitutional amendment to “tune up our democracy.”

And speaking of democracy, he suggests counting up all the votes in a presidential election and letting the person with the most win. With such seductive logic, he doesn’t need to even mention the Electoral College or get into a messy debate over how and why the framers of the Constitution sought to prevent America from devolving into a tyranny of the majority. Everyone is already cheering.

Reclaiming – and redefining – American values

But perhaps what most sets Mr. Buttigieg apart from the large Democratic field is the way he invokes values that have come to be seen as the province of conservatives.

“I believe in American values that are not values that belong to one party – they’re values that belong to all of us, but that I also believe point in a very progressive direction when we take them seriously,” he tells a crowd in Ottumwa.

Take liberty, he says. It’s not just about freedom from regulations or onerous taxes. It’s about freedom to choose how to live – freedom for women to choose (one of his biggest applause lines), to get quality health care, or to marry whomever you want, regardless of what a county clerk thinks.

He and his supporters know such positions can be a hard sell in Iowa, where religious conservatives hold significant sway. “When I enthuse about you, people say, ‘America isn’t ready to elect a gay man president,’” a man tells Mr. Buttigieg at a campaign stop. Ireland has a gay prime minister and South Bend seems to have gotten over it, he continues. How can I convince them?

Mr. Buttigieg responds by sharing his own decision to come out after serving as a Navy Reserves intelligence officer in Afghanistan and returning to his job as mayor. He won reelection several months later with 80% of the vote.

“God does not belong to a political party,” he is fond of saying, adding that the Bible shouldn’t be used as a cudgel to tell people they don’t belong. He cites Scripture about feeding the hungry and caring for the stranger, and accuses the Trump administration of violating such tenets. He hopes, he tells the crowd in Muscatine, to make it “OK for those who are guided by faith to know that they don’t have to be pushed into the arms of the religious right – whose latest political decisions betray not only our values but also their own.”

And what about those whose deeply held convictions – religious or otherwise – do differ from his? He would like to persuade them, he says, but acknowledges that, “I won’t convince everybody, and that’s OK.” He adds, however, “that people who think a lot about freedom – conservatives and libertarians – should pause at a moment like this ... and ask if this isn’t a chance for resetting the entire spectrum in a way that will make Americans better off.”

Back in Burlington, as the last of some 500 attendees trickle out, someone with the Buttigieg campaign approaches Mr. Kupferschmid to return the baseball he had hoped Mayor Pete would sign.

“Hi Gary, I apologize profusely,” says the young man. “That’s OK, it’s better than Kamala Harris,” says Mr. Kupferschmid, who at least got his “Pete Buttigieg for President” button signed. “And he seems more genuine.”

He says, though, that with a lot of his money in the stock market, he’ll probably vote for Mr. Trump again next year if it keeps doing well. But he implies that calculus could still change.

As he ambles into the warm summer night, he peers into a trash can and pulls out a Pete sign.

In war on wildfire, California turns to military

California's sharp shift in combating the threats of drought and fire is also serving to highlight emerging common ground between forest conservationists and the timber industry.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

Wildfires killed more than 100 people and burned 1.8 million acres in California last year – a pair of grim state records. This year, Gov. Gavin Newsom has assigned about 100 soldiers with the National Guard to assist with prevention efforts to protect 200 vulnerable communities.

In the town of Colfax, where soldiers are creating a firebreak in the surrounding woodlands, residents welcome the Guard’s presence. “We need as many boots on the ground as we can get,” says Marnie Mendoza, the mayor pro tem.

Factors contributing to California’s megafires range from fire suppression and forest overgrowth to climate change. “We didn’t reach this point with fires overnight,” says Mike Mohler, a state fire official. “So we look at what we’re doing at these sites as the beginning.”

The devastation has prompted environmental groups to reassess the potential benefits of thinning and prescribed burns to heal ailing forests. “The old approaches haven’t got us to where we want to be,” says David Edelson with the Nature Conservancy.

The renewed emphasis on sustainable forestry has led to a cautious truce between conservationists and loggers. “The industry has sometimes had a hard time explaining what it does for the environment,” says Rich Gordon, head of the state’s forestry association. “But [the governor is] showing that it’s part of the solution.”

In war on wildfire, California turns to military

James Nelson deployed to Iraq in 2004 as an artilleryman with the Army. He saw fierce fighting and lost close friends during his one-year tour, and when he reflects on the experience, he wonders what the war achieved.

Fifteen years later, Mr. Nelson, now a sergeant first class in the California National Guard, has deployed to the Sierra Nevada foothills about 50 miles north of the state capital of Sacramento. Beneath a canopy of ponderosa and sugar pines, Douglas firs, and black oaks, he and 20 other soldiers work to remove underbrush and dead trees, assisting state crews to thin forests of the fuel that feeds wildfires. He describes the mission as more purposeful than his combat tour.

“Over there in Iraq, you’re protecting each other, but it’s hard to see where you’re making a difference,” Mr. Nelson says. “Here you can see cause and effect. It feels like we’re accomplishing something.”

He talked on a recent morning over the high whine of chainsaws and a wood chipper’s guttural thudding. On a leaf-strewn slope in front of him, soldiers clad in yellow and red safety gear cleared shrubs, bushes, and small trees; behind him rose another hillside where they had thinned the undergrowth in previous weeks.

Across the country, the National Guard typically arrives in communities during or after natural disasters, whether wildfires in the West, hurricanes in the South, or floods in the Midwest.

California Gov. Gavin Newsom has chosen a different tack, ordering about 100 members of the Guard to aid the state’s preventive efforts to reduce the risk of and devastation caused by wildfires. His strategy underscores the severity of the threat and, in a broader sense, illuminates an emerging cooperation between environmental groups and timber interests to restore forests.

Six of the 10 most destructive fires in California history occurred in the past two years, including the state’s deadliest blaze in and around the town of Paradise last fall. The Camp fire claimed 86 lives and almost 19,000 homes, businesses, and other structures. Smoke and ash from the inferno blanketed cities as far away as San Francisco, 170 miles to the south.

California will spend $1 billion over the next five years to bolster its fight against fires intensified by climate change and years of withering drought – a fight complicated by the deep penetration of home and commercial development into woodlands.

Governor Newsom declared a state of emergency on wildfires in March to accelerate the work. Since then, the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection, or CalFire, has targeted 35 areas for fuel reduction by next spring as officials seek to protect some 200 cities and towns considered most vulnerable to wildfires. The projects cover 90,000 acres and involve removal of dead trees, clearing undergrowth, creating firebreaks, and prescribed burning.

CalFire crews, private contractors, and the state’s conservation corps supply the bulk of the manpower. Still, for people in Colfax, a town of about 2,000 residents, the presence of Mr. Nelson and his fellow soldiers in the nearby hills provides an extra measure of reassurance.

“We don’t want Paradise happening here,” says Marnie Mendoza, Colfax’s mayor pro tem. She offered a war analogy to frame the ongoing struggle with wildfire. “We need as many boots on the ground as we can get to help save forests and save lives.”

Discarding old approaches

Fire officials and researchers ascribe California’s new era of megafires to a confluence of factors. The policy of suppression – snuffing out wildfires as quickly as possible – has prevailed nationwide on federal, state, and private lands since soon after the founding of the U.S. Forest Service in 1905.

Meanwhile, the forest service and state governments have enforced tight restrictions on tree harvesting in the West since the onset of the “timber wars” that stretched from the 1970s into the ’90s, when environmentalists clashed with the logging industry over spotted owl habitat and clear-cutting.

One legacy of those strategies exists in the form of forests choked by overgrowth and lacking natural fuel breaks to prevent the rapid spread of fire. Climate change has compounded the problem by imposing a prolonged drought that, along with a bark beetle epidemic, killed an estimated 147 million trees in California over the past decade.

The dead trees add to a surplus of fuel and contribute to a wildfire threat that state officials rate as “very high” or “extreme” across 25 million acres of woodlands and grasslands. “Whether you believe in climate change or not,” says Mike Mohler, a CalFire deputy director, “the conditions on the ground are causing fires to explode.”

He motioned toward the hillside where the soldiers worked on what will be an 850-acre fuel break, a cleared tract intended to slow a fire’s advance and give crews a chance to contain the flames. “We didn’t reach this point with fires overnight. So we look at what we’re doing at these sites as the beginning,” he says. “We have to maintain and hold this ground.”

The increased density and dryness of forests, grasslands, and shrubland has coincided with untamed residential growth in the wildland-urban interface, or WUI, the areas where development meets nature. Many wildfire researchers judge that trend – and the failure of most owners to safeguard their homes against fire – as the primary reason for the breadth of destruction.

More than a quarter of the state’s population – 11 million people – live in fire-prone areas, and from 2000 to 2013, three-quarters of the homes destroyed by wildfire in California fell within the WUI. Yet even after the recent blazes that ravaged Paradise, Santa Rosa, and other cities, a strong desire to rebuild has taken root, as homes and businesses sprout anew.

California’s wildfires yielded a pair of grim state records in 2018 by killing more than 100 people and scorching 1.8 million acres. The devastation of the past few years, amplified by manmade forces, has prompted environmental groups to reassess the potential benefits of thinning and prescribed burns to heal ailing forests.

“The old approaches haven’t got us to where we want to be,” says David Edelson, the Sierra Nevada project director for the Nature Conservancy.

Two years ago, the nonprofit joined the Tahoe-Central Sierra Initiative, an alliance formed by the state and the U.S. Forest Service that includes environmental and timber industry groups. The coalition has set out to restore 2.4 million acres of federal forestland in the Sierra Nevada through thinning, prescribed burns, and limited logging.

Mr. Edelson, a veteran of the timber wars, regards Governor Newsom’s plans at the state level as an extension of the collaborative spirit that inspired the Tahoe initiative. “The governor recognizes this is an all-hands-on-deck situation,” he says. “There is absolutely growing support for better management of our forests and better protection for our communities.”

The coalition’s partners have coordinated a 30,000-acre restoration project in a watershed west of Lake Tahoe. A wildfire ripped through the overgrown Tahoe National Forest in 2014 and loosened topsoil that heavy rains later washed into a reservoir. Dredging the clogged lake cost $5 million, and Marie Davis, a consulting geologist on the watershed project, explains that thinning the forest and conducting prescribed burns could avert a recurrence.

“We have to make a cultural shift away from both the Smokey Bear days of putting every fire out and from the anti-logging days of saying the removal of any tree is bad,” she says. “That’s giving us bigger and bigger fires.”

A cautious truce

An estimated 15 million acres of the state’s forestlands and grasslands need restoration to varying degrees. Christina Restaino, a forest ecologist at the University of Nevada, Reno, has studied whether thinning coupled with prescribed burns can improve forest health amid California’s drought and bark beetle infestation.

She has found that, in areas cleared of undergrowth and small trees, less competition for water – or “fewer straws in the cup,” in her phrasing – boosts survival rates of mature trees, which are more resistant to fire. Other research shows that thinning small trees and tall shrubs reduces the amount of so-called ladder fuels that can propel flames into the canopy, where fire moves faster and becomes harder to extinguish.

“We’re never going to realistically thin enough of our forests – they’re too vast,” Ms. Restaino says. But she asserts that underbrush removal paired with prescribed burns can resuscitate forests and lower wildfire risk. “We have to reimagine what healthy forests look like and then actively manage them. We can’t just keep doing what we’ve been doing. People are dying, not just trees.”

The renewed emphasis on sustainable forestry has led to a cautious truce between environmental groups and the logging industry. In March, a conservation trust and a lumber company brokered an $11.7 million land swap that bans development and logging in a redwood forest south of San Jose and places strict logging rules on another expanse of redwoods 40 miles away.

The California Forestry Association represents the state’s timber industry and belongs to the Tahoe initiative. Rich Gordon, the group’s president and chief executive officer, suggests that the magnitude of megafires has pushed environmentalists and loggers to find common cause.

“California was sitting on a ticking time bomb with our forests,” he says. “But we didn’t really know how big the bomb was.”

The state’s five-year wildfire prevention plan subsidizes removal of vegetation and small trees – a sweetener for companies to harvest materials with little commercial value – and loosens tree-harvesting regulations on private land. Mr. Gordon credits the governor with bringing timber interests into the public discussion of managing forests.

“The industry has sometimes had a hard time explaining itself and what it does for the environment,” Mr. Gordon says. “But he’s showing that it’s part of the solution.”

Some environmentalists remain opposed to any logging on public or private lands, and likewise, there are researchers who question the efficacy of relatively small-scale thinning projects given the size of the state’s forests. At the same time, a study last year found that most researchers generally agree on the need to clear undergrowth in connection with prescribed burning to eliminate fuel.

The coming months of wildfire will offer a test of the state’s more aggressive tactics. In the hills near Colfax, the National Guard soldiers work eight to 10 hours a day, the buzz of their chainsaws filling the forest. Lt. Jonathan Green, the unit’s commander, observed that one measure of the project’s success would be silence.

“The irony is, if what we’re doing here works, you’ll never hear about this place,” he says. “It won’t be like Paradise. Let’s hope that’s the case.”

In Ukraine, a desire for peace. But whose peace?

Wishing for peace won’t end a war. Witness eastern Ukraine, where locals in opposing camps say they want peace, but show little inclination to soften views that help stifle its emergence.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

In Mariupol, near the front lines of Ukraine's civil war, people want peace, whether they want a future aligned with Europe or one back in Russia's familiar orbit. But their starkly different visions for what that peace would entail could prove a major obstacle for ending the conflict.

Maria Podibailo, a political scientist and activist, found that a three-quarters majority of local people supported a future as part of Ukraine, not Russia. “That’s when we knew we were on the right track,” she says. “We were not a beleaguered minority at all. We were part of the majority who want to be Ukrainian.” Her view is that the separatist republics will have to be forcibly brought to heel, and those who collaborated with “the enemy” would have to be punished, as after World War II.

Maxim Tkach, regional head of the “pro-Russian” Party of Life, disagrees. “Of course we need to negotiate directly with” the rebel republics, he says. “The task before us is to bring them back to Ukraine, and Ukraine to them. It must be accomplished through compromise and negotiation, because everyone is tired of war.”

In Ukraine, a desire for peace. But whose peace?

Almost every conversation in Ukraine these days will touch upon the grinding, seemingly endless war in the eastern region of Donbass. People speak of overwhelming feelings of pain and weariness. And they express near-universal hopes that the new president, Volodymyr Zelenskiy, will finally do something to end it.

Here in Mariupol, where the front line is a 10-minute drive from downtown, those conversations tend to be intense.

But depending on whom you talk to, the path to peace can look very different.

Much of the population around here speaks Russian, is used to having close relations with nearby Russia, and can’t imagine any peace that would impose permanent separation. Many people have family, friends, and former business associates living just a few miles away on the other side of the border. More than half of voters in the Ukrainian-controlled part of Donetsk Region, of which Mariupol is the largest city, expressed those instincts in July 21 parliamentary elections by voting for two “pro-Russian” political parties. Both of them would like to forge a peace on Moscow’s terms and return at least this part of Ukraine to its historical place as part of the Russian sphere of influence.

But there are also many who espouse an emerging Ukrainian identity, who see the 2014 Maidan “Revolution of Dignity” as a breaking point that gave Ukraine the chance to escape the grasp of autocratic Russia and embrace a European future. They want nothing to do with Russian-authored peace plans, say there is no alternative to fighting on to victory in the Donbass war, and want to quarantine Ukraine from its giant neighbor – at least until Russia changes its fundamental nature.

Despite the two groups’ shared desire for peace, their starkly different visions for what that peace would entail could prove a major obstacle for ending the war in eastern Ukraine.

Looking east, looking west

These divisions are rooted in Ukrainian history. The country’s eastern regions have been part of Russian-run states for over 300 years. Three decades of Ukrainian independence have brought little in the way of economic development or other strong reasons to embrace a Ukrainian identity. At the same time, Russia has become a far more prosperous, orderly place that exudes confidence and power since Vladimir Putin came to power. Millions of eastern Ukrainians have gone to Russia as guest workers – and more recently as war refugees. Today, the Ukrainian diaspora in Russia is by far the world’s largest.

The western regions of Ukraine, on the other hand, were part of European states like Austria-Hungary and Poland until World War II, when they were annexed by the Soviet Union. Now, people overwhelmingly speak Ukrainian as their first language, take a suspicious (and historically grounded) view of Russia, and tend to look west for their inspiration. In 1990, living standards in Ukraine and Poland were about equal. Since Poland joined the European Union in 2004, its living standards have doubled and it has become a vibrant European state. Millions of Ukrainians go to Poland and beyond as guest workers, and their impressions help to fuel the certainty that Ukraine needs to seek a European future.

Not coincidentally, the enthusiasm and conviction of western Ukrainians have disproportionately driven two pro-Western revolutions on the Maidan in Kyiv in the past 15 years, with little visible support from populations in the country’s east.

“People in the western Ukraine are different from us. It’s not just language, or anything simple like that. They took power away from a president our votes elected, and they want to rip us out of our ways, abandon our values, and become part of their agenda,” says Maxim Tkach, regional head of the Party of Life, the pro-Russian group that was the front-runner in parliamentary elections here in Mariupol.

“When they started that Maidan revolution, they said it was about things we could support, like fighting corruption and ending oligarchic rule. But none of that happened. They betrayed every single principle they had shouted about. Instead, they want us to change the names of our streets and schools, honor ‘heroes’ like Stepan Bandera that our ancestors fought against. These are things we can’t accept. ...

“If there had been no Maidan, we would still have Crimea. There would have been no war. There would be no pressure on us to change our customs, our language, or our church. It was this aggressive revolution, by just part of the country, that caused these problems,” he says. “Russia is Russia. It is acting in its own interests, but why do we need to antagonize it?”

“The majority who want to be Ukrainian”

Maria Podibailo, a political scientist at Mariupol State University and head of New Mariupol, a civil society group founded to support the Ukrainian army, offers a completely different narrative. She originally came from Ternopil in western Ukraine and has made Mariupol her home since 1991.

She says there were no separatist feelings in Mariupol, or the Donbass, until after the Maidan revolution when Russian agitators started traveling around eastern Ukraine, spreading lies and stirring up moods that had never existed before. Local pro-Russian oligarchs wielded their economic power to support separatist groups, while passive police and security forces allowed Russian-led separatists to seize public buildings and hold anti-Ukrainian protests in Mariupol. It wasn’t until the arrival of the Ukrainian army – first in the form of the volunteer Azov Battalion – that the separatists were driven out and the front line was pushed back from the city limits in 2014, she says.

“That is why we support the army, and only trust the army,” she says.

Ms. Podibailo’s university-sponsored opinion surveys in 2014, after the rebellion began, found that a three-quarters majority of local people supported a future as part of Ukraine, not Russia. That majority was subdivided into several visions of what kind of Ukraine it should be, but only 12% wanted to join Russia, and 8% wanted Donbass to be an independent republic – a point often overlooked in the simplistic pro-Russian versus pro-Western scheme in which these events are frequently portrayed.

“That’s when we knew we were on the right track,” she says. “We were not a beleaguered minority at all. We were part of the majority who want to be Ukrainian.”

But while the two nearby separatist statelets, the Donetsk People’s Republic and the Lugansk People’s Republic, may be backed by Russia, they emerged from deep local roots. That is a clear observation from one of the most exhaustive studies of the war to date, Rebels Without a Cause, published last month by the International Crisis Group.

The war has done great and possibly irreparable damage to Ukraine’s economy, and the longer it continues, the harder it may be to ever reintegrate the former industrial heartland of Donbass with the rest of the country.

“We cannot talk to the leaders of these so-called republics. How could we possibly trust them?” says Ms. Podibailo. Her view is that, after victory, the population of the republics should be sorted out into those who collaborated with the enemy and those who were innocent victims, as happened after World War II.

“There is no way for this war to end other than in Ukrainian victory. I have never heard of a war that ends leaving things the same way, or just through some talks. People say it might take a long time, and the threat will last forever because we have such a neighbor.

“But we have the United States behind us, we have the West behind us, and they are attacking Russia from the other side with sanctions. We will win,” she says.

“These are our people”

Mr. Tkach, the regional party head, says the idea of victory is a dangerous chimera, and what most people around here want is peace and restoration of normal relations with Russia.

“Of course we need to negotiate directly with” the rebel republics, he says. “These are our people. We understand them. Perhaps we need a step-by-step process, in which they are granted some special status. What would be wrong with that? They have also suffered, had their homes shelled by Ukrainian forces, lost their loved ones. Trust needs to be restored, and that might take some time.”

But he is adamant that those territories need to be recovered for Ukraine. “The task before us is to bring them back to Ukraine, and Ukraine to them. It must be accomplished through compromise and negotiation, because everyone is tired of war. Once we have done this, and have peace, then we can talk about Crimea.”

One of the leaders of the Party of Life – which came in a distant second in the national parliamentary elections – is Ukrainian oligarch Viktor Medvedchuk, who has strong connections to the Kremlin and whose daughter has Mr. Putin as her godfather. Attending the St. Petersburg International Economic Forum along with Mr. Putin this spring, Mr. Medvedchuk was introduced as “a representative of the Ukraine that can make a deal.”

Mr. Tkach says so too. “We wish Zelenskiy well, but we really doubt that he can make peace happen. Our party has the connections and the right approach, and we think it will be necessary to bring us into the process.” He’s talking about dealing with the Russia that exists just across the Sea of Azov and a few miles down the road.

Ms. Podibailo will have none of that. “After victory, Crimea has to be returned. Donetsk and Lugansk have to be returned. Russia has to pay reparations. And it has to change. Russia cannot be an empire anymore,” she says.

To which Mr. Tkach retorts, “Some people think the sun might freeze over one day. But must we wait for impossible things to happen? Why can’t we try to make peace now?”

‘Granny flats’: more affordable housing. More parked cars, too.

The expansion of “granny flats” can produce a political test of clashing values. More apartments can mean lower housing costs – but also a denser population, and neighborhood change.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

The leafy Washington suburb of Maryland’s Montgomery County recently relaxed restrictions on “granny flats,” and some residents aren’t happy about it. Accessory dwelling units (ADUs) – also known as granny flats or in-law apartments – transform basements, garages, or separate backyard buildings into housing. They’re a way of increasing affordable housing in desirable areas. But they can be controversial because they increase density and often accommodate racial, economic, and other demographic change.

“It’s just that feeling: You drive into your neighborhood and all of a sudden you can’t get through your street and there’s people everywhere,” says Sam Nasios, an auto repair shop owner who opposed the granny flat change.

ADUs have proliferated on the West Coast. Portland, Oregon, loosened rules in 2009 and saw applications increase tenfold. Seattle saw a similar jump.

Now they’re moving east. Near Washington some suburban Virginia locales are increasing ADU permits to help ease a chronic housing crunch. The Montgomery County Council voted unanimously to follow suit. Members say the move will fight suburban sprawl and welcome new residents.

“It’s a more affordable way to live in a more expensive location,” says Councilman Hans Riemer, who introduced the amendment.

‘Granny flats’: more affordable housing. More parked cars, too.

Wearing a homemade shirt that spelled out – in black-and-red felt letters – her opposition to a Montgomery County zoning code amendment, Aleks Rohde parsed her fears. She doesn’t hate “granny flats,” she said. She just dislikes what they could bring to her neighborhood: density.

“The denser the neighborhood, the more the problems,” said the retired Army lawyer. “Like that study with rats, where [behavioral scientist John Calhoun] packed them in a more crowded space and they started attacking each other. It’s human nature.”

Ms. Rohde was one of two dozen protesters who showed up at the Montgomery County Council’s July 23 meeting to oppose a proposal to relax restrictions on accessory dwelling units (ADUs), basement or garage spaces also known as granny flats or “in-law apartments.”

Expansion of ADUs to accommodate housing demand has proved to be a controversial issue across the United States. Notably that’s been the case in recent months here in Maryland’s Montgomery County, a prosperous and reliably Democratic suburban enclave of Washington.

Earlier this summer, a local elected official sparked outrage by saying ADUs would turn Montgomery County “into a slum.” The protesters at the July council meeting, mainly retirees, disavowed this statement. But they do genuinely see ADUs as a harbinger of unwanted change for Montgomery neighborhoods.

Unfortunately for them, at the July 23 meeting the council voted unanimously to loosen ADU regulations, potentially allowing thousands more county residents to transform garages, basements, or detached structures into extra apartments. Council members were eager to adopt an approach pioneered by cities like Portland and Denver, which used granny flats to add affordable housing in wealthy areas. That’s something Montgomery County desperately needs, say ADU proponents, as its housing costs spike and decades of population gain strain infrastructure.

But longtime residents resist imagining suburbia as something other than a haven of single-family homes. Montgomery’s fight over granny flats was really a proxy war for opposition to the county’s population “overcrowding” and diversification, says Sam Nasios, an auto repair shop owner who opposed the amendment.

People buy homes in leafy areas such as Montgomery County to get a little peace and quiet, some separation from the craziness that otherwise surrounds them, says Mr. Nasios. Increasing density takes that away.

“It’s just that feeling: You drive into your neighborhood, and all of a sudden you can’t get through your street and there’s people everywhere,” he says.

Communities across the country are wrestling with similar problems as cities’ rising costs push more and more people into the surrounding suburbs.

Civic leaders and housing experts promote suburban densification as a way to address the nationwide housing crisis and suburban sprawl that helps drive climate change. But retrofitting these communities presents many financial, political, and technical challenges like bulking up schools or adding sewer lines.

Perhaps the trickiest problem is cultural and racial: integrating new neighbors – often people with lower incomes and different skin colors – into prosperous areas where white people have been predominant.

“There is a social contract in neighborhoods that you will treat one another with respect and try to do unto others as they do unto you. Be the neighbor that you want to live next to,” says Councilman Hans Riemer, who introduced the zoning amendment. “But that means different things to different people, and I think that perhaps that’s part of the challenge.”

Surviving high prices

Licensed ADUs remain a small portion of U.S. housing. But some cities and towns have found that easing the licensing process leads to a big increase in granny flat numbers.

After Portland, Oregon, loosened rules in 2009, annual ADU applications jumped tenfold, to over 600 in 2016. Santa Cruz, California, and Seattle experienced comparable increases. Los Angeles used to prohibit most ADU conversions, but in 2017 California passed a law overriding such local restrictions. Applications skyrocketed, and in 2017 LA issued over 4,000 ADU permits.

Not all ADU campaigns are successful, though. Last fall the Reno, Nevada, City Council rejected a granny flat proposal, after a wealthy historic neighborhood organized opposition.

For Montgomery County, the backdrop to the ADU conversation is its transformation from a quiet, tony, very white suburban swath into one of the country’s most diverse and bustling counties, fueled especially by a Hispanic population that has tripled over the past 30 years.

The county has remained relatively wealthy, with a median income currently hovering around $100,000. However, that statistic masks the racial and ethnic disparities. Black and Hispanic homeowners are more likely to have incomes below $50,000 than above $100,000. At that income level, finding affordable housing becomes much more difficult, particularly when average home values in the county are over $450,000.

Mr. Riemer says this reality is why he pushed for the zoning amendment.

“[ADUs] add housing in the supply and that’s helpful, but more importantly it’s a more affordable way to live in a more expensive location,” he says.

For Nuri Funes, the steep costs have pushed many of her friends out of the county.

“I feel sad because they have been in this community, in this church, and they want to stay here; they like the schools for their kids,” says Ms. Funes, a licensed child care provider originally from El Salvador. “I think about my kids: They’re young adults and they’re not going to be able to buy anything because prices are rising so much.”

She says families will often double or triple up in one house just to get by. When she first moved to Montgomery County 26 years ago, she and her husband moved in with her mother and helped pay off the mortgage. Then, when they bought their own house down the street, they rented out their basement to her sister-in-law and her husband. Ms. Funes says it’s common in her culture.

“Our culture is different,” she says. “You will never see [me] place my mother in a nursing home. I will keep her until she dies. So that adds an extra person to my family. We help each other, and maybe that’s why you see the difference in how many people live in a house.”

Population boom breeds conflict

What Ms. Funes calls culture, some others call overcrowding.

“I’m not saying this to single out the Hispanic community, I just think that because it is the most growing population, they tend to be the bigger offenders of having too many cars parked in the grass, having multiple families living in single-family homes and things like that,” says Mr. Nasios, who immigrated from Greece nearly 40 years ago.

He freely admits that the neighborhood civic association has not done the best job reaching out to the Hispanic community and wants to work to improve that. “I feel that [the Hispanic community] is not at the table when all this stuff is happening,” he says. “You cannot provide solutions unless everybody involved is [at] the table.”

He also insists his opposition stems from a genuine concern – rather than a racial bias – over how overcrowding has affected his neighborhood, particularly the excess of cars. His neighborhood of Aspen Hill has struggled to keep pedestrians safe, most notably when four teenagers were hit and injured last year, with one person sustaining brain damage.

Mr. Nasios isn’t alone in worrying about this. Overcrowding is a legitimate issue, says Mr. Riemer, and some neighborhoods bear the burden more than others.

“It is a reality that families are making it work living here by crowding into single-family housing. Turns out that people are mostly living within the law when you go to inspect,” he says. “But that is just what happens when you don’t build enough housing and a lot of your housing is set aside for single-family use.”

Similarly, Ms. Funes dislikes that cars clog up her streets and endanger her children. She recognizes she is part of the problem – all five people living in her house own cars – but what is she supposed to do when cars are necessary for jobs and life?

“If we don’t want people to travel further in their cars, then we need to have people living near things, which means more people in places that are already what many people consider to be built out,” says Alex Baca, housing program organizer for the nonprofit Greater Greater Washington.

Such a scenario troubles Ms. Rohde, the protester, who says the additional density added by ADUs will lower property values. However, there is no data to corroborate her fears, and Mr. Riemer expects a modest increase from the roughly 40 ADU permits the county gets every year.

“ADUs are tiny, a drop in the bucket,” says Ms. Baca. “This is not revolutionary by any stretch, but it does start to get at [the fact] that the form of our neighborhood is not going to work super well going forward.”

Many housing experts are raising the alarm that the suburbs are 20th-century relics and poorly equipped to handle modern challenges like climate change or the housing crisis. Transforming our society requires sacrifices, says Ms. Baca, but Montgomery County is already better prepared than most places. It has the wealth to bankroll the transformation, a progressive county council that backs it, and substantial community buy-in. Mr. Riemer says the “dozens upon dozens” of emails he received in support of the zoning amendment drowned out the opposition.

All Ms. Funes wants is a place where her friends don’t have to leave and her children can afford to stay. She’s optimistic about the county’s future.

“You see all the buildings and the new recreation center, the library, and it’s like, yeah! You feel more proud, you want to live here, stay here – your grandchildren to be here. I’m happy that more people want to come and live here. That’s good, right? If other people want to come to this community, then there’s something good here.”

Watch

One woman’s quest: Use art to bring focus to marriage

This video story looks at the universal uplift of art. When design that bolsters cultural traditions is lovingly applied to a marriage contract, the terms can take on extra meaning.

Nushmia Khan wants to make Muslim marriages more beautiful. She’s reviving the tradition of decorated nikahnamas, or stylized marriage contracts. A former wedding photographer, Ms. Khan started an online nikahnama shop in 2019.

“Islamic art has always been something where you’re making everyday objects more beautiful,” says Ms. Khan. “I was just thinking, ‘What is something that we all use that could be made more beautiful?’ And I found the nikahnama idea.”

Her work is about more than making objects that couples can hang on their walls. It’s also about giving Muslim marriages a more solid foundation. An integral part of Muslim marriages, wedding contracts make the couple’s union legal under Islamic law. It’s also a space where couples negotiate conditions for their marriage – everything from money to where to live. Ms. Khan says she sees many Muslims sign the contracts carelessly, sometimes without even reading them, missing an opportunity to keep problems from arising later.

“When we are talking about protecting the interests of women in marriage, the contract is fundamental,” says Imam Abdullah Faaruuq, of Mosque Praise Allah in Boston’s Roxbury neighborhood.

With beautiful designs, Ms. Khan hopes to draw couples’ attention to the contract and the negotiation of the bride’s and groom’s rights and responsibilities.

“It’s better than photos even sometimes,” she says, “It’s what they actually signed and touched, and agreed upon.” – Husna Haq, video by Jingnan Peng

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Why corporations redefine progress

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

In a statement, the top executives of leading companies in the United States tried to redefine progress in the business world. Instead of a sole focus on maximizing profits, stated the Business Roundtable, corporations must now deliver value to a range of constituencies.

This is not the first time the Roundtable has changed its view on the purpose of a corporation. And it may not be the last. Almost any company must continually seek ways to measure success against the rising expectations of those inside and outside the firm.

Almost as a rule, progress entails frequent improvements in the statistical yardsticks for determining progress. The search itself suggests a motive to forge a consensus on ways to better serve others as well as one’s own interests.

At the global level, the definition of progress has been in rapid churn. One reason is a desire to move beyond a common measure of a nation’s success: growth in gross domestic product. Many groups try to put numbers on concepts such as “well-being.” Yet the point is not so much to find the holy grail of one or more numbers. The pursuit itself is to elevate the idea of progress for all.

Why corporations redefine progress

The top executives of nearly 200 leading companies in the U.S. issued a statement Monday that tries to redefine progress in the business world. Instead of a sole focus on maximizing profits and share prices, stated the influential Business Roundtable, corporations must now deliver value to a range of constituencies, such as employees, local communities, and society writ large, not just the owners who have risked their money.

“Each of our stakeholders is essential,” said the statement. The Roundtable also proposed a broad vision of protecting the environment, investing in workers, and dealing ethically with suppliers.

In other words, instead of corporations being merely value driven – as in the legal obligation for financial returns to investors – they must also be values driven, for example in being accountable for their actions to a wider range of interests. The twin goals reflect a sophisticated balancing of what are often seen as competing forces.

This is not the first time the Roundtable has changed its view on the purpose of a corporation. And it may not be the last. Almost any company must continually seek ways to measure success against the shifting demands and rising expectations of those inside and outside the firm. One sign of a recent shift: A July survey for Fortune magazine found nearly two-thirds of Americans say a company’s “primary purpose” should include “making the world better.”

Almost as a rule, progress entails frequent improvements in the statistical yardsticks for determining progress. The search itself suggests a motive to forge a consensus on ways to better serve others as well as one’s own interests.

At the global level, the definition of progress has been in rapid churn over recent decades. One reason is a general desire to move beyond a common measure of a nation’s success: growth in gross domestic product. That single statistic, first devised in 1941, is seen as too narrow. Both governments and academics have struggled to go beyond merely measuring material progress and prosperity.

The United Nations has devised a “human development index.” In 2009, France gathered top thinkers to come up with statistical tools for calculating social goals, such as income equality and happiness. The European Union has proposed “sustainable development indicators.” The club of wealthy nations known as the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development has an ongoing project to measure “the progress of societies.”

The search continues to put numbers on concepts such as “well-being,” “sustainable development,” or “scientific advancement.” Yet the point is not so much to find the holy grail of one or more numbers. The pursuit itself is to elevate the idea of progress for all. Like today’s corporations, the vision just needs to be expanded to include everyone.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Harmony in the classroom

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Kathryn Jones Dunton

For one special education teacher, what she’d learned about the real nature of God and His children empowered her to respond to challenges in the classroom with patience, compassion, and calm.

Harmony in the classroom

When I was in college, I transformed from being an unhappy, discontented person into a more joyful, loving individual. It wasn’t an easy road, but the change naturally took place through what I was learning in Christian Science. I came to understand God as Love itself, who created everyone in His image. This brought a fuller love for God, for my fellow man, and for myself.

This desire to express God’s love toward others later led me to become a special education teacher. It wasn’t always easy to maintain a happy and harmonious classroom, but I’d seen in my college experience how an understanding of the real nature of God and of man can make a meaningful difference.

So every day as I entered the classroom, I saw my students as having a deeper individuality than appeared on the surface, and I refused to accept disruptive behavior as a depiction of their true identity. In “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” Mary Baker Eddy, the discoverer of Christian Science, explains: “Jesus beheld in Science the perfect man, who appeared to him where sinning mortal man appears to mortals. In this perfect man the Saviour saw God’s own likeness, and this correct view of man healed the sick” (pp. 476-477). Because everyone, in their true identity, is made in the spiritual image and likeness of God, any aberrant, inappropriate behavior is not a part of anyone’s true, spiritual nature.

Mentally embracing God’s view of these dear students helped in tangible ways. For example, one day a student (let’s call him Andrew) stormed into my classroom and slammed his open cup of soft drink on the floor. I knew that what he needed was love, understanding, and guidance, not anger. In that moment I thought of Andrew’s true spiritual nature as not an angry teenage boy, but a calm, satisfied, loving, peaceful, and productive (not destructive) spiritual idea – God’s loved son.

This calmed my fear and shock at that startling event, enabling me to respond with patience and compassion. Andrew calmed down and was even able to complete assignments during the class session. And during Andrew’s tenure in my classroom, he expressed greater and greater joy and dominion over disruptive, angry behavior. Those who had known him before commented on the great progress they were witnessing. And later, after Andrew had transferred to another school, he came back to visit me and expressed gratitude for the loving, encouraging environment he had felt in our classroom.

Whether or not we’re teachers, each of us has a choice concerning how we respond in any encounter. We can react with anger and impulsiveness, or we can hold calmly to the truth of each individual’s spiritual nature. Time and again I’ve seen that it’s the latter that brings forth the most meaningful improvement on the human scene.

Not only is seeing others in this spiritual light beneficial, but it’s also important to view ourselves the same way. We can recognize that our capacity to help others is ours from God, whose love is expressed in all of us, bringing comfort and guidance. And we can be willing to let go of any tendency to ruminate about past conflicts; instead, we can approach each day as a new opportunity to see ourselves and others the way God sees and loves us. This lifts fear, frustration, and resentment – and opens the way for healing.

We can trust God to lead us forward in harmony every new day. As the Bible says, “It is of the Lord’s mercies that we are not consumed, because his compassions fail not. They are new every morning” (Lamentations 3:22, 23).

A message of love

What is the air-speed velocity of an unladen swallow?

A look ahead

Thanks for starting your week with us. Come back tomorrow, when global correspondent Peter Ford will introduce us to the all-female Uganda Women Birders group. They bring a special sensibility to their work with tourists – and are finding a sense of independence for themselves.