- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

The personal acts of love that counter racism

It’s another week in which the national conversation will swivel between public health and social justice, against a backdrop of political drama.

What have been some personal approaches to fighting racism?

Some go all in. Last week, when NBA players were working through how to balance their careers with social justice advocacy, a few observers suggested that attention might also be paid to Maya Moore, a star who decided, pre-pandemic, to sit out the WNBA season to pursue criminal justice reform.

Some assist others’ growth. Jeremiah Swift and Ryun King, tattoo artists in Murray, Kentucky, recently began offering a free body-art modification service to patrons who wore inked expressions – symbols, slogans – that no longer reflected who they were.

“Having anything hate related is completely unacceptable,” Mr. King told CNN. “We just want to make sure everybody has a chance to change.”

Conversations about race are useful, and are now more frequent. But all of us can do more than just talk, says Rhonda Magee, a law professor trained in sociology. In her 2019 book “The Inner Work of Racial Justice,” she prescribes “[staying] in our discomfort long enough to deepen insight,” to bring transformation and healing.

“We can do better,” she tells Daily Good. “The invitation to mindfully turn toward those things we’ve been trained to think we can’t handle, with confidence and compassion, is how we’ll get there.”

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Will focus on racial justice give Black candidates a boost?

A rising challenge to the status quo that cuts across America’s racial, generational, and ideological lines provides a lift for some Black congressional candidates. How will shifts in thought affect voting in a number of districts tomorrow?

As protests for racial justice continue to sweep the nation, many Black congressional candidates are seeing their campaigns surge as voters head to polling places for primaries on Tuesday.

In New York’s 16th District, former Bronx middle school principal Jamaal Bowman has found himself suddenly in the spotlight in his bid to oust longtime Rep. Eliot Engel, one of the most powerful Democrats in the House. In Kentucky’s Democratic primary for the U.S. Senate, Charles Booker, the youngest Black legislator in the Kentucky House of Representatives, was found by one recent poll to be ahead of Amy McGrath, the former Marine fighter pilot favored by most Democratic officials to take on Majority Leader Mitch McConnell.

Voters have also begun to single out racial justice issues as among the most pressing problems facing the nation – ahead of the coronavirus crisis, and comparable to the economy, jobs, and cost of living.

“The focus on Black Lives Matter, and the sense that there needs to be more representation by Black Americans in our systems of government, has helped create the tail winds behind some of these candidates,” says Theodore R. Johnson, senior fellow at the Brennan Center for Justice at New York University.

Will focus on racial justice give Black candidates a boost?

At the end of May, when hundreds of thousands of Americans around the country started marching in protest over the death of George Floyd, many observed that this time the protests felt different.

Not only was there a greater urgency – punctuated at times by violence, looting, and aggressive responses from local police – but the Black Lives Matter banner now included hosts of white Americans, in numbers not seen previously.

Since then, a number of young Black congressional candidates have seen their campaigns surge. Once considered long shots as they mounted primary challenges to Democratic incumbents or other establishment-backed candidates, Black progressives running in New York, Kentucky, and Virginia appear to have the wind at their backs as voters head to polling places Tuesday in the midst of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic.

In New York’s 16th District, former Bronx middle school principal Jamaal Bowman has found himself in the spotlight in his bid to oust Rep. Eliot Engel, a 16-term incumbent and one of the most powerful Democrats in the House. First-time candidate Mondaire Jones is battling a crowded field of candidates for an open seat in New York’s 17th District. Like Mr. Bowman, he is backed by leaders of the left or progressive wing in Congress, including Sen. Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts, Sen. Bernie Sanders of Vermont, and Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez of New York.

In Kentucky’s Democratic primary for the U.S. Senate, Charles Booker, a progressive candidate and the youngest Black legislator in the Kentucky House of Representatives, was found by one recent poll to be running ahead of Amy McGrath, the former Marine fighter pilot favored by most Democratic officials to take on Sen. Mitch McConnell, arguably the most powerful legislator in all of Congress.

“We’re on probably week three or four of daily protests in most major cities around the country – protests that are multiracial, multigenerational, and across the ideological and party spectrum,” says Theodore R. Johnson, senior fellow at the Brennan Center for Justice at New York University. “There’s no doubt that the focus on Black Lives Matter and the sense that there needs to be more representation by Black Americans in our systems of government has helped create the tail winds behind some of these candidates.”

Indeed in a number of polls, voters have begun to single out racial justice issues as among the most pressing problems facing the nation, even ahead of the coronavirus crisis, and comparable to the economy, jobs, and cost of living.

“It’s now becoming an issue that has gotten to the top of the agenda,” says Gayle Alberda, professor of politics and public administration at Fairfield University in Connecticut. “It’s now surpassed health care, it’s surpassed other things like foreign affairs. Now we’re looking at conversations surrounding criminal justice, policing, and other sorts of issues concerning racial relations.”

Already a trend

In some ways, the surge by Black progressives this election cycle was already part of a wider trend, experts say. Since 2018, a number of Black women have taken the executive reins of major American cities, including London Breed in San Francisco, Lori Lightfoot in Chicago, and LaToya Cantrell in New Orleans.

Even high-profile Black candidates who were not successful in 2018, such as Democratic gubernatorial nominees Stacey Abrams in Georgia and Andrew Gillum in Florida, likely helped pave the way for some of the candidates who followed.

“I do think those candidates provided a roadmap for newer Black politicians seeking office, and answered some questions about the kinds of coalitions they could build,” says Mr. Johnson. “How do you get Black voters, who actually tend to be more moderate, and white voters in Democratic primaries, who tend to be more liberal, all on the same team behind the same candidate?”

“I think what Black progressives are able to do is make the ideological policy appeals to white liberals while also making the sort of descriptive representation that appeals to Black voters,” he says.

Generational shifts

In taking on Mr. Engel, the chairman of the House Foreign Affairs Committee, Mr. Bowman hopes to follow the playbook of fellow New Yorker Ms. Ocasio-Cortez, the self-described Democratic Socialist who pulled off a surprise 2018 primary victory against former Rep. Joe Crowley, a powerful kingmaker in Queens and a ranking member in the House’s Democratic leadership team. Rep. Ayanna Pressley in Massachusetts is another progressive woman of color who defeated a 10-term Democratic incumbent in 2018.

“There is a really strong bench of young people coming up, and in many cases they are challenging those who are seen as insiders, moderates, or part of the existing leadership,” says Jeanne Zaino, a professor of political science at Iona University in New Rochelle, New York.

The question, however, is whether white voters will indeed embrace candidates such as Mr. Bowman, who has also accepted the “socialist” label. Ms. Ocasio-Cortez won in a district in which half the residents are Hispanic, 18% are white, and 11% are Black. The district now represented by Mr. Engel includes some suburbs in Westchester county: A third of its residents are white, a third are Black, and a quarter are Hispanic.

In Virginia, 36-year-old physician and Black progressive Cameron Webb has made headway in a four-candidate race to become the Democratic nominee in the state’s 5th Congressional District, which includes Charlottesville. Though Republican-leaning overall, the district ousted incumbent Republican Rep. Denver Riggleman in a “drive-thru convention” earlier this month. A conservative Trump supporter, Mr. Riggleman appeared to lose party support after he officiated at a same-sex wedding. The open seat could now be more competitive in November.

“Charlottesville is a good area for Cameron Webb,” says Mr. Johnson. “Not only is it well-educated and with a very prestigious university there – which tends to signal a populace that leans on the liberal side – but also [given] the events of Charlottesville from a couple years ago and the ongoing Confederate statue debates the state’s having. Even though the area doesn’t have a large Black population, I think white liberals here are certainly more open to supporting a Black candidate.”

Still, all of these races on Tuesday have local idiosyncrasies. Dr. Zaino notes the adage that all politics are local.

“A lot of the so-called establishment candidates have also themselves done a good deal for progressive causes,” she says. “Nobody can accuse Eliot Engel of not being a friend of the teachers, for instance, even though Bowman’s obviously had such a long history with education.”

“But Engel is part of the leadership. He’s been in Washington for 30 years. He’s older,” Dr. Zaino continues. “I think we’re seeing just a huge amount of support going to younger progressives, and this is really being buttressed by this money that’s coming in from the left. Particularly when you’re talking about primaries, where turnout is usually smaller, the people who do turn out really care about those endorsements from Sanders, Warren, and Ocasio-Cortez.”

At the same time, white liberals continue to be energized by racial justice issues, Mr. Johnson says.

“The question is how much of these new tail winds are substantial and will endure,” he says. “People are looking like they want to do something, and supporting Black politicians is a good way to exercise their Black Lives Matter protests in a more traditional sense.”

Voicing ‘solidarity’ against US racism, Arabs expose scourge at home

Sometimes it takes events abroad to make a society confront its own flaws. Our Middle East correspondent shows how a regional urge to support U.S. racial justice protesters has stirred such an awakening.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

The Arab world has experienced invasion, colonialism, and oppression. Yet in the aftermath of George Floyd’s killing has come a growing awareness that the region is not immune to colorism and racism. The debate here was kicked off not by police brutality, but by tone-deaf attempts to express “solidarity” with the Black Lives Matter movement that have reinforced racial stereotypes.

In just one example, an Algerian singer posted a photo of herself in complete blackface, the word “solidarity” written across. The result has been a backlash on Arab social media. “People, don’t overdo this ‘solidarity,’” says Maryam Abu Khaled, a Black Palestinian actress, in a viral video seen by over 2 million, “because that itself is racism.”

A shift in attitudes is slowly taking shape. After 13 years of campaigning against institutional inequality, African Iraqis, a minority of 500,000, are finally receiving media attention to their cause by drawing parallels between the killing of Mr. Floyd and the 2013 assassination of their community leader in his hometown of Basra.

Tunisian malls and clothing lines have dropped Arab models and stars that recently used blackface. Joseph Fahim, an Arab film critic, says there has been “a growing awareness that no, this is not right.”

Voicing ‘solidarity’ against US racism, Arabs expose scourge at home

Abu Yahya watches protests in Minneapolis rage on his mobile and shakes his head in amazement.

“Here they say, ‘We aren’t racist,’ that we are all Arabs and Muslims, until they see my skin,” says the Sudanese refugee in Amman, Jordan. “Then they call me ‘slave.’”

“Just as there’s an awakening in America, it’s time for our society to wake up.”

The protests following the police killing of George Floyd that are shifting perceptions in the United States have also sparked a growing awareness that even here – in a region that has experienced invasion, colonialism, oppression, and war – there is a need to come to terms with its own past of colorism and racism.

Yet the growing debate in the Arab world about attitudes toward race was kicked off not by police brutality or historically tainted statues, but by ham-fisted and tone-deaf attempts to express “solidarity” with the Black Lives Matter movement.

In recent weeks, several Arab stars, singers, and actors sparked a backlash by posting online statements that inherently reinforced racial stereotypes.

One Algerian singer posted a photo of herself in complete blackface, the word “solidarity” written across, and the sentence: “Just because we are black on the outside doesn’t mean we are black on the inside.”

A Lebanese actress posted a digitally altered photo of herself in blackface with an Afro, saying, “I wish I was Black,” while other media stars denounced the violence against Black Americans while voicing casual colorism and racism, such as, “It’s not their fault, that is the way God made them.”

“People, don’t overdo this ‘solidarity,’” Maryam Abu Khaled, a Black Palestinian actress says in a viral video seen by over 2 million, “because that itself is racism.”

History

Analysts say part of the Arab world’s struggle to acknowledge racial inequality, racism, and a culture of colorism stems from a refusal to acknowledge a muddled history with Black populations.

“The George Floyd protests have opened an opportunity for us, but we still live in societies that are in denial about our very existence,” says Khawla Ksiksi, a Black Tunisian activist who leads a collective demanding the rights of Black Tunisians, an estimated 10% to 15% of the country’s population.

With the Arab world acting as a link between Africa, Asia, and Europe, there is a range of skin colors among Arabs – white, olive, tan, brown, and black – sometimes within the same tribe.

But there has long been a bias for white or fair-skinned actors, models, and potential brides and grooms, and an inherent prejudice against Black Arabs with origins in Africa – a colorism activists say is rooted in slavery.

From the ninth to 19th centuries, Arab merchants and rulers played a role in the trans-Saharan slave trade and the Indian Ocean slave trade, with merchants selling Black Africans either on to the West, or to be used as laborers and servants in the Persian Gulf and in Arab cities.

In addition to employing indentured servants and slaves, the Arab world absorbed a migration of African workers, merchants, and traders from modern-day Zanzibar, Ethiopia, and Eritrea. Black Arabs from Sudan also settled permanent communities in the Arab world and Iran.

Ottoman, French, and British colonial powers barred these communities from receiving services and filling positions of power.

By the 20th century, post-independence Arab nationalist leaders eager to depict the “utopia” of a united nation papered over marginalized and impoverished Black communities, deleting them from their country’s past and present.

Activists today point to chronic inequality in access to education, employment, and housing, and cycles of poverty stretching centuries. Worse still is representation in government; most Arab countries have yet to appoint a Black government minister.

“Dictators erased us and made us invisible, preventing us from even speaking or appearing in public,” says Ms. Ksiksi.

“To this day we do not know how many Black Tunisians exist in Tunisia. Until we accept and embrace Black communities, we are a long way from working towards equality.”

Media lens

The debate over race has opened what Arab citizens and activists are calling a long overdue discussion of Black people’s representation – or lack thereof – in Arab media.

The use of blackface on Arab television and in film has sparked a backlash on Arab social media, with citizens calling out the hypocrisy of actors and filmmakers declaring solidarity for Black Lives Matter in America while wearing blackface at home.

“People are starting to become conscious that blackface is a problem that goes beyond cultural appropriation or exoticizing; it is a message that we look down upon Black people and that we perceive black as ugly,” says Joseph Fahim, an Arab film critic and writer. In the past few days, he says, there has been “a growing awareness that no, this is not right.”

People have been reposting clips of Egyptian and Gulf television comedians decked out in blackface mocking Sudanese and Africans by acting lazy, dumb, rowdy, and even “primitive” – some scenes as recent as 2019.

Meanwhile, activists in Egypt, Tunisia, Algeria, and elsewhere point to the lack of Black media presenters, anchors, television hosts, and interviewees on the airwaves.

“The problem is not just misrepresentation in television and film; it is a complete lack of representation. Africans and Blacks are not present on screen,” says Mr. Fahim. “In most cases they simply don’t exist.”

Words count

The Black Lives Matter movement has also spurred an online debate over the use of the Arabic equivalent of the N-word in daily conversation and even in newspapers, as well as the casual use of abed, or slave.

The firestorm has spread to the dessert menu.

Even as American companies reevaluate racially insensitive brand names, a culture war has erupted in the Arab world over Ras Al Abed – a round, chocolate-covered marshmallow sweet popular in Jordan, Syria, and Lebanon and among Palestinians whose name translates as “slave’s head.”

Activists online have been posting photos of Ras Al Abed packages with a smiling character in cartoon blackface, with blinding white teeth and eyes, and wearing African garbs, stating, “How is this not racist as well?”

Already in Jordan, one chocolate company dropped the name of the controversial sweet, posting “we heard you!” on social media in response to campaigners.

But some Arabs have pushed back online and in the broadsheets against the charges of racism. Such words are used in jest, they say, not part of a systemic racism or an ideology of racial superiority.

“I wanted to answer people who say, ‘Maryam, you can’t compare racism in America to racism in the Arab world. At least we don’t kill,’ ” says Ms. Abu Khaled, the Black Palestinian actress, in another viral video.

In a lighthearted tone, she describes hearing mothers telling their children, “Quit playing in the sun, or else you will burn and become like Maryam,” and swimming in a pool while other patrons openly debate whether her skin color will “run off” in the water.

“Do you know that the things you say ‘as a joke’ can break the spirit of the person in front of you and shatter their self-esteem?” Ms. Abu Khaled says.

Shift in attitudes

But a change in discussion – and a shift in attitudes – is slowly taking shape.

Tunisian malls and clothing lines have dropped Arab models and stars that recently used blackface, and pressure campaigns continue in Egypt to do the same.

After 13 years of campaigning against institutional inequality, African Iraqis, a minority of 500,000, are finally receiving media attention to their cause by drawing parallels between the killing of Mr. Floyd and the 2013 assassination of their community leader, Jalal Diab, in his hometown of Basra.

Tunisians have held multiple protests in solidarity with Black Lives Matter to draw attention to racism in Tunisia, pressuring the government to enforce a 2018 anti-racial discrimination law, the first of its kind in the region.

“This is an opportunity to put the campaign against racism in the spotlight and have that uncomfortable conversation Arab societies have been avoiding for decades,” says Ms. Ksiksi, the Tunisian activist.

“We can still teach the new generation a different way,” Ms. Abu Khaled says in a video. “We can explain that people are different, with all honesty. ... Children’s hearts are pure, so let’s teach them what’s right from a young age.”

As Russia reopens, Putin takes a back seat to local leaders

Here’s another perspective story: Russia’s grappling with the push-pull on how fast to reopen as COVID-19 lingers looks familiar to onlookers from other nations. What’s become clearer in this case: cracks in the political power structure.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Moscow’s emergence from its three-month coronavirus shutdown will feature images that look familiar to Americans. But Russia’s political discontents are distinctly different. The crisis has exposed social fault lines, and at least temporarily, it has altered the division of powers between Moscow and the country’s far-flung regions.

The Russian government’s plan to stimulate the economy with social spending, announced early this year, has also been thrown into disarray and been hastily replaced by a $70 billion “recovery program.” The program’s level of success may spell the difference between social stability and unrest over the next year.

Mr. Putin’s public approval rating has fallen to a “historic low” of 59% amid the crisis, with the ratings of other leaders, including Prime Minister Mikhail Mishustin and Moscow Mayor Sergei Sobyanin, rising significantly. That is almost certainly due to Mr. Putin’s decision to step back and leave the coronavirus heavy lifting to local governors and Mr. Mishustin’s team of technocrats.

“The crisis of 2020 has been very tough, and there may be some shocks yet to come,” says Vladimir Klimanov, an expert at a civil service academy. “It has been a totally new situation for Russia.”

As Russia reopens, Putin takes a back seat to local leaders

Any news report about Moscow’s current, tentative emergence from its draconian three-month coronavirus shutdown will feature images that look thoroughly familiar to Americans.

They include shops reopening with strange new rules about social distancing and clerks who serve customers through plexiglass shields; people thronging into the streets again, but mostly wearing alien-looking face masks and gloves; and thousands of people ignoring all the new rules to picnic in summery urban parks or just bask in (unaccustomed, for Moscow) June sunshine.

The news covers tense warnings from medical experts and opposition politicians that restrictions are being eased too fast, too soon, and that it risks triggering a devastating second wave of infections. Some business leaders, whose livelihoods have been pummeled over the past months, insist that normalization isn’t coming fast enough.

Editor’s note: As a public service, all our coronavirus coverage is free. No paywall.

And even a few outliers can be heard on TV, claiming the whole thing was a hoax and that Russians were imprisoned for months in their own homes for nothing.

But Russia’s political discontents are distinctly different. There are no mass eruptions in the streets, yet the crisis has nevertheless exposed social fault lines. It has also forced the Kremlin to recalculate the ambitious plan it floated at the start of 2020 to revamp Russia’s political system, change the constitution, and perhaps keep Vladimir Putin in power for two more terms. And at least temporarily, it has altered the division of powers between long-authoritative Moscow and the country’s far-flung regions.

Reopening too fast?

One of the most bitter political gripes making Russian social media rounds is that Mr. Putin is rushing to end the lockdowns so that he can stage the annual Victory Day parade, Russia’s most important patriotic holiday, after it had to be postponed from May 9 amid the crisis. Another important political event, a national referendum to approve the sweeping package of constitutional changes, is now slated for July 1.

“There are obvious political considerations behind the decision to quickly lift the lockdowns, and these have nothing to do with public health,” says Georgy Satarov, a Yeltsin-era Kremlin official who heads the independent INDEM Foundation. “They have not estimated the risks with the right priorities.”

Yet many, particularly in Moscow’s beleaguered small-business community, are welcoming it.

“The numbers of new coronavirus cases in Moscow has been steadily falling. The situation in hospitals is manageable and stable. This is the right time to start unwinding the restrictions,” says Dmitry Orlov, head of the pro-Kremlin Agency of Political and Economic Communications. “Other regions may have different situations, and they have been given the freedom to move at their own speeds.”

The Russian government’s plan to stimulate the economy with social spending, announced early this year, has also been thrown into disarray and been hastily replaced by a $70 billion “recovery program.” The program’s level of success may spell the difference between social stability and unrest over the next year, as Russian businesses struggle to revive themselves and average Russians battle soaring household debt, high levels of unemployment, and declining faith in government.

“Russia has taken some bad hits,” says Ruben Enikolopov, rector of the New Economic School in Moscow. “It’s not just all the losses from the pandemic and the costs imposed during the lockdown. We simultaneously saw a massive drop in oil and gas prices, which is a huge shock. Official figures suggest at least a 5% drop in GDP, even without all the uncertainty of whether there will be a second wave of the pandemic. This is already the worst crisis Russia’s been through since the 1990s.”

Some economists say the post-COVID-19 slump is likely to be more than 8% of GDP, and the Kremlin is not using the crisis as an opportunity to advance reform. Without major initiatives to stimulate small business and diversify the economy, state assistance programs will just end up moving state money through state banks to benefit state corporations, says Alexei Vedev, an expert with the Gaidar Institute in Moscow.

“I think that if there are no changes in Russia’s economic model, we will end up with stability characterized by stagnation,” he says.

Federalism, Russia-style

Mr. Putin’s public approval rating has fallen to a “historic low” of 59% amid the crisis, with the ratings of other leaders, including Prime Minister Mikhail Mishustin and Moscow Mayor Sergei Sobyanin, rising significantly. That is almost certainly due to Mr. Putin’s decision to step back from his well-cultivated image as a leader with his hands on the control panel of a monolithic “power vertical” system of authority. Instead, he has largely left the coronavirus heavy lifting to local governors and Mr. Mishustin’s team of technocrats.

That has led to at least a temporary decentralization, with more de facto authority to deal with the crisis passing to Russia’s 85 diverse and often remote provinces. They include 21 often restive ethnic republics such as those in the north Caucasus and Tatarstan, and over 60 regular regions that sprawl from the Pacific far east to the Baltic Sea exclave of Kaliningrad.

Some observers argue that Moscow’s authority could be in danger of unraveling as local officials seize more initiative. They point to a tough conversation between Mr. Mishustin and regional leaders in early April, in which the prime minister explicitly forbade establishing any “internal boundaries” to block interregional trade and travel during pandemic. At least two regions, Chechnya and Chelyabinsk, openly defied him.

“We haven’t seen anything like that since 1998, where Russian regions try to close their own internal borders,” says Vladimir Klimanov, an expert with RANEPA, a civil service academy founded by the president. “This [decentralization] was only for the period of the pandemic, though it’s possible that some local leaders, having had a taste of more power, might try to keep it.”

Another rather unprecedented example was the news last week that more than a dozen Russian cities have refused to hold local Victory Day parades on June 24, citing the fact that – unlike Moscow – the pandemic is still raging in their regions. Also surprising was the Kremlin’s response: to let it go. “They are implementing these powers because the governors, as the president has said, on the ground see better how things really are,” said Kremlin spokesman Dmitry Peskov.

“The crisis of 2020 has been very tough, and there may be some shocks yet to come,” says Mr. Klimanov. “But this isn’t like the 1990s. It was the right move to let regions handle their own pandemic responses, and generally speaking the measures taken have been effective. It has been a totally new situation for Russia – and for the whole world too.”

Editor’s note: As a public service, all our coronavirus coverage is free. No paywall.

A deeper look

In Queens, residents become the coronavirus safety net

The stories within this next story – anchored in New York’s most diverse borough – color a powerful look at mutual-aid work that’s about nothing less than the restoration of human dignity.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 9 Min. )

When Sharmila Moonga received a bag brimming with groceries last month, she says it felt like Christmas.

She’s spent the pandemic alone in her apartment in the Queens borough of New York City. Without a social safety net or access to New York City services, she says two weeks passed without a meal. Hunger forced her to try to eat blank pages from her diary.

The donations came from COVID Care Neighbor Network, a mutual aid group in central Queens – once the “epicenter of the epicenter.” The effort has been headquartered out of the garage of Nuala O’Doherty-Naranjo, a community organizer running for New York state legislature, as a stopgap for New Yorkers when city services aren’t enough.

The crisis has thrown the city’s inequality into sharp relief, she says. Over a third of the city’s food pantries and soup kitchens shuttered at the height of the outbreak.

For Ms. O’Doherty-Naranjo and fellow candidates committed to community service, the public health crisis trumped politics.

“Normally in a campaign you go to political events, you go to parades – I think my time feeding my neighbors was very well spent,” she says. “How could we not do it?”

In Queens, residents become the coronavirus safety net

When her hunger grew too great, Sharmila Moonga began to eat blank pages from her diary. Alone in her apartment this spring, she says two weeks passed without a meal.

At first she welcomed the challenge of life under lockdown, enjoying her private independence. Then her leftover rice and lentils dwindled.

The aides who oversaw her cancer treatment – and often brought her food – discontinued visits. Neighbors in her apartment building in the Queens borough of New York City became ill. Living with a disability, she found solo trips to the grocery store were practically impossible. The Sikh temple that greeted her with the occasional meal closed its doors.

“It was a combination of fear and ... well, I’m not doing so bad, because I have a roof over my head,” she says. “I don’t really have much to complain about.”

There was also the embarrassment, says Ms. Moonga, of being unable to fend for herself. She attempted to ask for free meal delivery through the city’s hotline, but the automated system failed her. Frustrated and faint, she spent days taking medicine on an empty stomach.

She found COVID Care Neighbor Network on Facebook, a mutual aid group in Queens. On May 1, a bag brimming with rice, fruit, pasta, and canned food was delivered to her building.

“It’s like Christmas – the joy of you receiving something that you so desperately need,” she says.

Editor’s note: As a public service, all our coronavirus coverage is free. No paywall.

COVID Care has fed over a thousand families in Queens, the diverse borough once home to the pandemic’s epicenter and over a fifth of the city’s “essential” workforce. The effort has been headquartered out of the garage of Nuala O’Doherty-Naranjo – a community organizer running for New York state legislature – as a stopgap for New Yorkers when city services aren’t enough.

A patchwork of collaborators have joined in, including displaced immigrant workers and repurposed campaign volunteers. For Ms. O’Doherty-Naranjo and fellow candidates committed to community service, the public health crisis trumped politics.

“I’m exhausted,” she said with a laugh Friday, four days from the June 23 primary. “Normally in a campaign you go to political events, you go to parades – I think my time feeding my neighbors was very well spent. How could we not do it?”

The crisis has thrown the city’s inequality into sharp relief, she says. As the city reels from the virus and inches toward reopening, mutual aid efforts like COVID Care help restore dignity block by block. In Ms. Moonga’s words, “They don’t pass judgment.”

“Epicenter of the epicenter”

It’s all hands on deck outside the garage. Over the next few hours, some 120 families in central Queens will receive a bag with a day’s worth of food. Hair swept back into a low ponytail, Ms. O’Doherty-Naranjo directs more than a dozen masked volunteers on a May afternoon to put this bag in that car, guided by a rainbow-rowed spreadsheet. Another car stops and pops its trunk.

“Oh great! Another donation!”

With a platform pressing education, health care, and transportation, Ms. O’Doherty-Naranjo paused her campaign for New York State Assembly on March 13 to focus on neighbors’ needs. Her outreach began with sticky notes on doors. A Facebook group emerged, as did nearly 800 volunteers.

“I have to be part of the solution,” says volunteer Cordelia Persen. “I can’t just sit at home and watch the pain of my own neighbors.”

People call into the COVID Care phone line, staffed by volunteers. For help accessing government benefits and other resources, callers pair up with social workers from nonprofit partner Together We Can Community Resource Center, which oversees fundraising. After WNYC profiled Ms. Moonga in May, COVID Care received $1,800 in donations within 24 hours.

“I want to go out of business,” said Ms. O’Doherty-Naranjo last month. Yet the effort continued through last week, with at least 1,864 donated bags of groceries, 4,015 calls, and $45,000 raised. The new focus is a just-launched food pantry that will expand outreach in the high-need neighborhood of Corona.

The first American-born of her Irish family, she and her Ecuadorian husband have lived in Jackson Heights since 2001, where her activism has ranged from education and safer streets to community gardening. She also spent over 20 years as a Manhattan prosecutor. Over Easter weekend, she helped a Nepalese Tibetan couple assign power of attorney over their children to a friend. The couple was gravely ill with COVID-19, and worried for their toddler and 18-month-old.

“Her help was really meaningful,” says Pratima Maharjan, who recovered along with her husband. “I really trust her and love her.”

The majority of District 34’s residents are foreign-born, and 6 out of 10 are Hispanic. The district overlaps with Democratic Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez’s territory.

Ahead of Tuesday’s crowded primary, Ms. O’Doherty-Naranjo isn’t the only Democratic state assembly hopeful who pivoted to community service. Candidate Jessica González-Rojas temporarily halted her campaign March 12.

“I’m a public health person. I wouldn’t dare put my community at risk because I’m trying to win a political seat,” says Ms. González-Rojas, former executive director at the National Latina Institute for Reproductive Health.

Her team put down their clipboards and set up a phone bank to track residents’ needs. She says thousands received deliveries of groceries, medicine, and other essentials, as well as help applying to government aid. She also hosted a virtual town hall for English and Spanish speakers on public benefits.

Born to Paraguayan and Puerto Rican parents, the Latina candidate prioritizes high-quality health care for all, along with immigrant and LGBTQ rights and criminal justice reform.

Candidate Joy Chowdhury, a Bangladeshi American immigrant taxi driver and labor organizer, seeks to bolster the working class through a “Gig Worker’s New Deal.” Health care and affordable housing are also on his agenda.

“I represent a community of laborers who have been underrepresented, who have kind of no voice, no guaranteed income, no health care – I don’t have health care,” says Mr. Chowdhury, also a member of the U.S. National Guard. With family back in Bangladesh to support, he’s spent the pandemic juggling community service, the need to earn a living, and his campaign, which was “minimized to a near pause for many weeks in late March to much of April.”

Mr. Chowdhury is part of the women-led Queens Mutual Aid Network, a borough-wide initiative he says has organized grocery deliveries to over 1,000 families since late March. As a volunteer dispatcher and delivery driver, he organized special deliveries during Ramadan. The immigrant advocate also donated 10 masks to COVID Care volunteers.

According to his campaign website, white incumbent Assembly Member Michael DenDekker suspended campaigning on March 12 (the governor ultimately reduced petitioning requirements due to the pandemic). The six-term Democrat’s outreach has included distributing food and personal protective equipment, as well as helping constituents with unemployment insurance claims, a spokesman for Mr. DenDekker wrote the Monitor over email.

Hunger emergency

In a city of over 8 million people, typically 1.2 million are food insecure. Over the course of the pandemic, the city’s estimate has grown to 2.2 million.

New York City disperses some 1.5 million free meals a day via pickup sites and home deliveries – a network overseen by mayor-appointed “Food Czar” Kathryn Garcia, Department of Sanitation commissioner. While the city’s estimated 360,000 unauthorized workers are ineligible for benefits like federal stimulus checks, food stamps, or unemployment insurance, the city’s emergency food resources are offered regardless of immigration status.

“We have a commitment in this city that no New Yorker will go hungry because of this crisis,” the department’s assistant commissioner for public affairs, Joshua Goodman, told the Monitor in May. “Anyone in need should not be afraid to reach out for help.”

Ms. O’Doherty-Naranjo has called the city’s meal handouts inefficient, and favors more temporary aid that would allow unauthorized families to shop for themselves. She says the majority of COVID Care callers for weeks have been food-insecure immigrants.

“The best step is food stamps, so families can go on their own to the grocery store with dignity, buy the culturally appropriate food they want ... and cook in their own home,” she says. Due to federal coronavirus relief, every New York public school student – no matter immigration status – will receive up to $420 for food benefits.

Some New Yorkers have reported kinks in the emergency food system. Ms. Moonga says she called New York City’s 311 hotline three or four times to inquire about free meal delivery. The automated system couldn’t discern her accent as a British Indian woman, she says, so it directed her to the wrong department each time (once to “noise complaints”).

Citywide closures of food pantries and soup kitchens peaked at 39% by mid-April, according to a report published this month. Economic and social distancing constraints forced these sites to shutter, according to the findings of the city’s largest hunger-relief organization, Food Bank for New York City. The Bronx – the city’s poorest borough and current center of the outbreak – had half its emergency food programs close, followed by Queens at 38%.

Hourslong lines at food pantries also made headlines. (Mr. Goodman, the city spokesman, notes that proper social distancing leads to longer lines.) When Dudley Stewart saw lines of locals waiting for handouts at churches and schools, it spurred him to partner with COVID Care. The co-owner of Queensboro restaurant in Jackson Heights had already been donating meals to frontline heroes at an overwhelmed city-run hospital.

“We realized that as much as it was great to be able to provide meals to health care workers, it seems like there’s a lot of people whose need is far, far greater in this moment,” he says. COVID Care used Queensboro’s walk-in refrigerators and kitchen space to assemble food donations for weeks. Mr. Stewart says the eatery will soon open for sidewalk seating under the city’s “Phase 2.”

Felipe Idrovo, an Ecuadorian immigrant who supports Ms. O’Doherty-Naranjo’s campaign, started delivering for COVID Care in March. The next month, the candidate’s family and his fellow church members helped him move as he was forced to find a new apartment – while battling COVID-19.

Mr. Idrovo had a rough spring. He lost his factory job in March (by April, the city’s unemployment rate tripled). The virus canceled church and his volunteer work on the board of immigrant-rights group Make the Road New York. His brother died of COVID-19 after nine years in a nursing home.

Now recovered, Mr. Idrovo says volunteering has been a personal boon.

“I’m staying active doing what I can,” he says. “It really helps unload my pain.”

“Poverty is the real enemy”

On a bright May day at the edge of a Queens neighborhood, dozens of men stand with their backs to a fence. One steps to the curb with arm extended, a plea to drivers exiting the highway. But there are no moving jobs, no construction, no gardening gigs.

An hour passes and no one stops. The day laborers wait, as they do every day.

“There’s been no work for two months,” says Jonathan, an unauthorized immigrant from Guatemala who preferred not to print his last name.

“Many of our friends live on the street now. They could no longer pay rent,” says another, who declined to give his name for security.

COVID Care has handed out 470 bagged lunches to day laborers. Today Jonathan is one of the lucky ones. He thanks the volunteers. Clutching the brown paper bag with a sandwich inside, he’s happy, he says.

While manufacturing and construction revived June 8 under the city’s “Phase 1” reopening, Pedro Rodriguez says unauthorized workers’ families are still three months behind on rent and other utilities, which take priority over food. “Poverty is the real enemy,” he says.

Mr. Rodriguez is the executive director of La Jornada, a food pantry that has relied on mutual-aid volunteers to help deliver groceries to residents of the Corona neighborhood.

Need has exploded. In January, La Jornada served some 1,000 families a week. Now up to 6,000 families are served weekly; Mr. Rodriguez estimates a third are unauthorized. Partnered with COVID Care and Together We Can, last week it launched a new food pantry at the Queens Museum, with the goal of feeding 1,000 families a week as COVID Care ceases regular deliveries.

“Now millions of people have felt poverty and they’ve never felt that before,” he says. As those who lost jobs begin to return to work, he wonders if the past months’ economic ruin will inspire a new empathy for others.

“What will happen to their views on the poor, on the needy, on the widow, on the orphan, on immigrants ... since they were part of that group?”

Ms. Moonga says she offers her food to struggling neighbors in her building. She continued to receive COVID Care groceries every few weeks, along with weekly check-in calls. She recently asked the group if it were possible to find some yarn.

Thanks to a stranger’s donation, the yarn has become one more pandemic blessing. She hadn’t touched knitting since the summer of 2018, when she was diagnosed with cancer.

“It’s like heaven,” says Ms. Moonga. She gifted one volunteer a rose-colored crochet heart.

Editor’s note: This story has been updated to clarify the primary candidates’ political affiliations as Democrats. As a public service, all our coronavirus coverage is free. No paywall.

Points of Progress

Apple detectives rediscover long-lost fruits

Finally, a survey of some news with uplift. We found examples of real social progress, from a renewed push against anti-Semitism in an old Nazi refuge to architecture in Egypt that reduces the need for electricity-powered cooling. And, yes, scientists shake loose some apple diversity thought to have been lost.

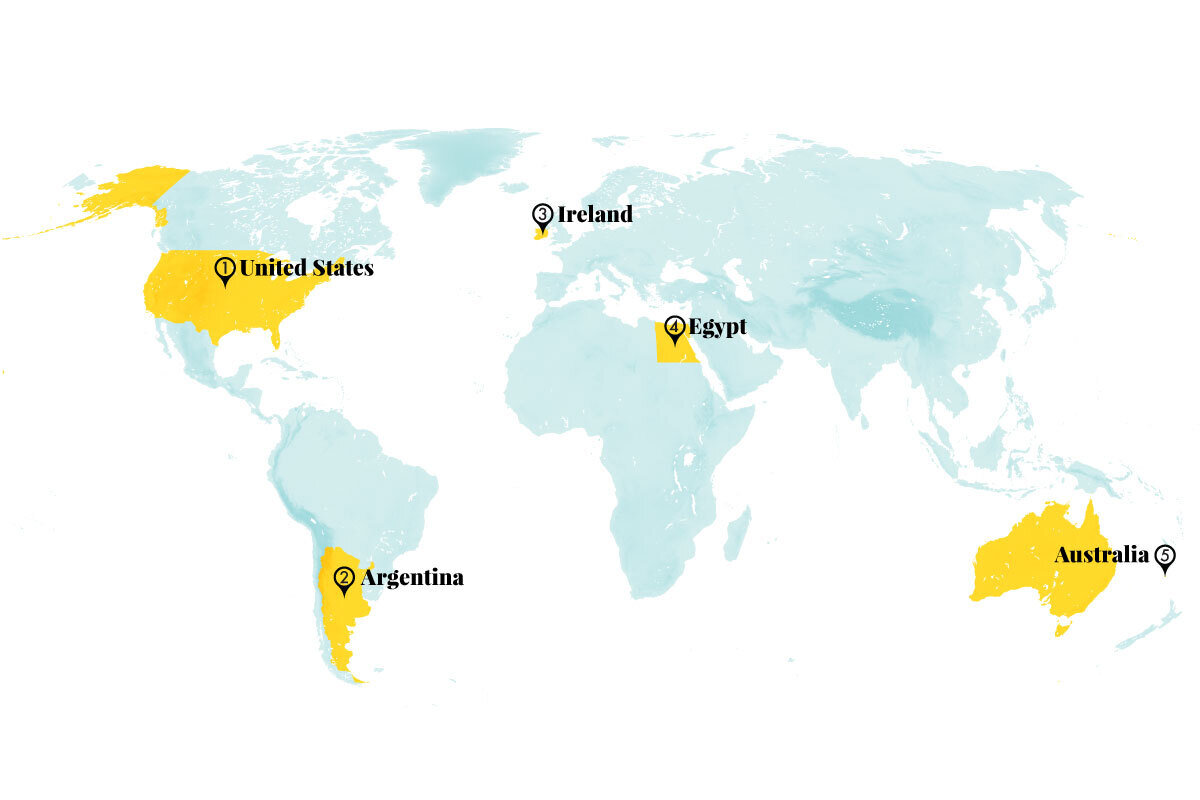

Apple detectives rediscover long-lost fruits

1. United States

A team of apple detectives has discovered 10 apple varieties thought to be extinct. North America once boasted 17,000 unique apple varieties, but only around 5,000 are confirmed to exist today. Of those, just 15 make up 90% of U.S. apple production. Recent discoveries include the ancient Sary Sinap, which originated in Turkey, and the Streaked Pippin, which could date back to 1744 in New York. E.J. Brandt and David Benscoter are the fruit sleuths behind The Lost Apple Project, a nonprofit that searches abandoned farms and orchards in the Pacific Northwest for long-forgotten apple trees. They aim to rescue both the apples and the history of the pioneer families that brought the trees out West.

Their unusually high yield this fall nearly doubled the duo’s total to 23 rediscovered apple types. The United States is the second-largest apple producer in the world after China. More choices for consumers is important, say agriculturists, to give domestic apples a competitive edge against imported fruits and to encourage genetic diversity. (The Associated Press, Smithsonian Magazine)

2. Argentina

Argentina has adopted the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance definition of anti-Semitism. In the latest move to address its history of Nazi refuge and anti-Semitic violence, its foreign ministry announced on June 7 that it would use the universal definition “to contribute to the fight of the Argentine Republic against anti-Semitism in all its forms.” More than two dozen countries have adopted the IHRA’s definition, and Argentina’s foreign minister called on public and private institutions to do the same. Argentina’s ambassador to Israel, Sergio Daniel Urribarri, who in 2011 became the first governor to require comprehensive Holocaust education for all schools in his province, said the new definition will also help to continue developing Holocaust remembrance as an official Argentine policy. (JNS, The Jerusalem Post)

3. Ireland

More than 50 Irish companies are following through on a 2015 pledge to halve their carbon footprints. The group of companies, which includes Gas Networks Ireland, Sodexo, and Tesco, promised to reduce direct greenhouse gases by 2030. The average emissions intensity reduction among participants jumped from 36% to 41% last year, according to a new study. This year, the pledge expanded to include some indirect emission sources, such as water consumption and business travel. “Ireland has a huge challenge ahead to transition to a low carbon economy but also embrace the opportunities a net-zero world will offer,” said Tomás Sercovich, chief executive of Business in the Community Ireland, one of the pledge’s coordinating partners. “Our aim for the pledge is to provide leadership, set a collective ambition and drive practical action.” (The Irish Times)

4. Egypt

In Egypt, where summer temperatures can reach 120 degrees F, architects have figured out how to cool the interior of buildings without using traditional air conditioning. Firms such as ECOnsult are using local materials and innovative designs, including heat-reflecting roofs and insulating air layers, to bring comfort to businesses and government buildings across the country. Green buildings can also help reduce carbon emissions by lessening the need for electrical-power cooling. One worker in Egypt’s Western Desert said his team’s upgraded ECOnsult buildings are cooler in the summer and warmer in the winter by 9 to 12 degrees. (Thomson Reuters Foundation)

5. Australia

For the first time in a decade, Australia’s morepork owl population on Norfolk Island has grown, thanks to the survival of two fledglings. The recent discovery is a huge boost to one of the world’s rarest owls, with an estimated population of 45 to 50. It’s not the first time the species has been close to extinction – in the 1980s the population declined to a single female. Conservationists on the remote island brought in mates from a subspecies in New Zealand, creating a hybrid line of morepork owls. Recent efforts to save the owl include building nest boxes and reducing predators. However, the owls had not bred successfully since 2011. Park manager Melinda Wilson said that discovering the chicks was one of the most special moments of her career. (BBC)

Outer Space

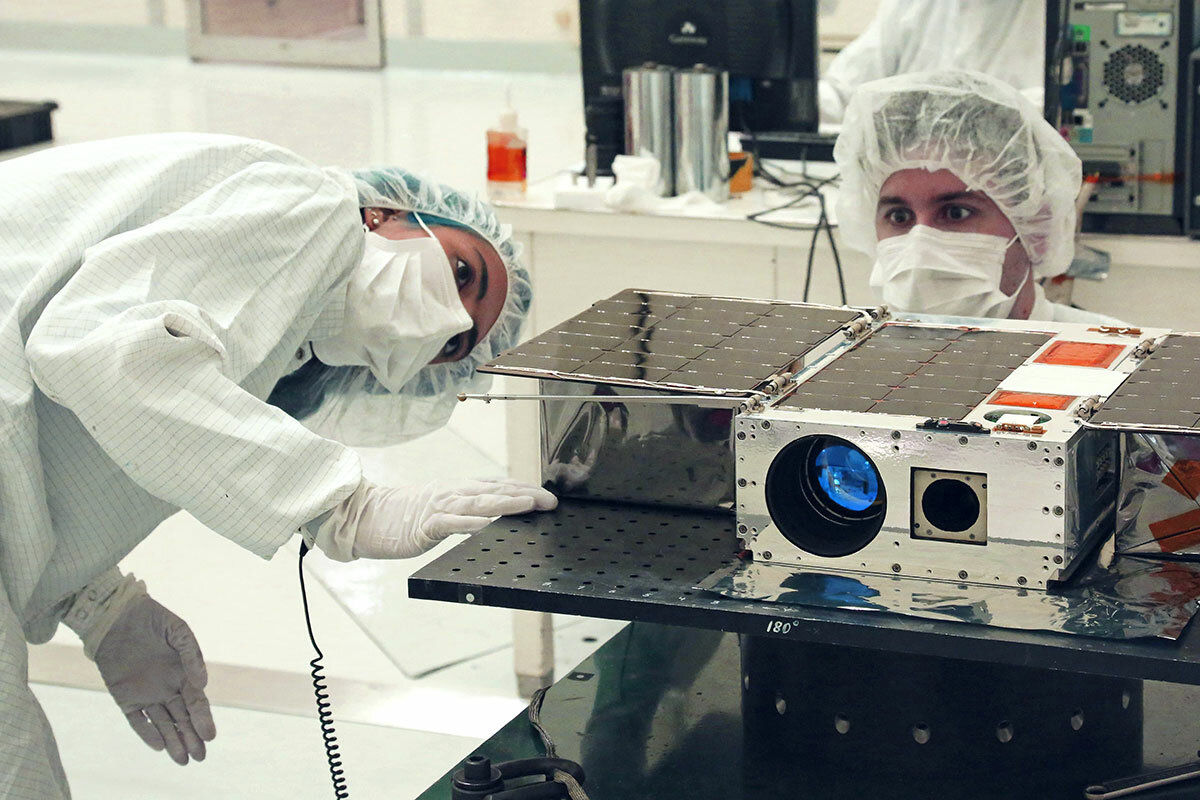

A spacecraft the size of a casserole dish has broken the record for smallest satellite to detect a planet outside the solar system, proving that modest machines can make meaningful contributions to astronomy. Asteria was part of NASA’s CubeSat program, meant to test the capabilities of tiny satellites made from privately manufactured, interlocking parts.

It spotted the raging hot “super earth” dubbed 55 Cancri e by catching dips in light as the planet passed by its host star. But this wasn’t part of Asteria’s original mission. The pioneering CubeSat satellite completed its initial task – to simply stay focused on an object for a long period of time – in 2018, and continued gathering useful data for two years before ground crews lost contact with it. Asteria’s success is good news for the CubeSat initiative, which aims to provide low-cost technology options to researchers and students around the world. (Inverse, Popular Mechanics)

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

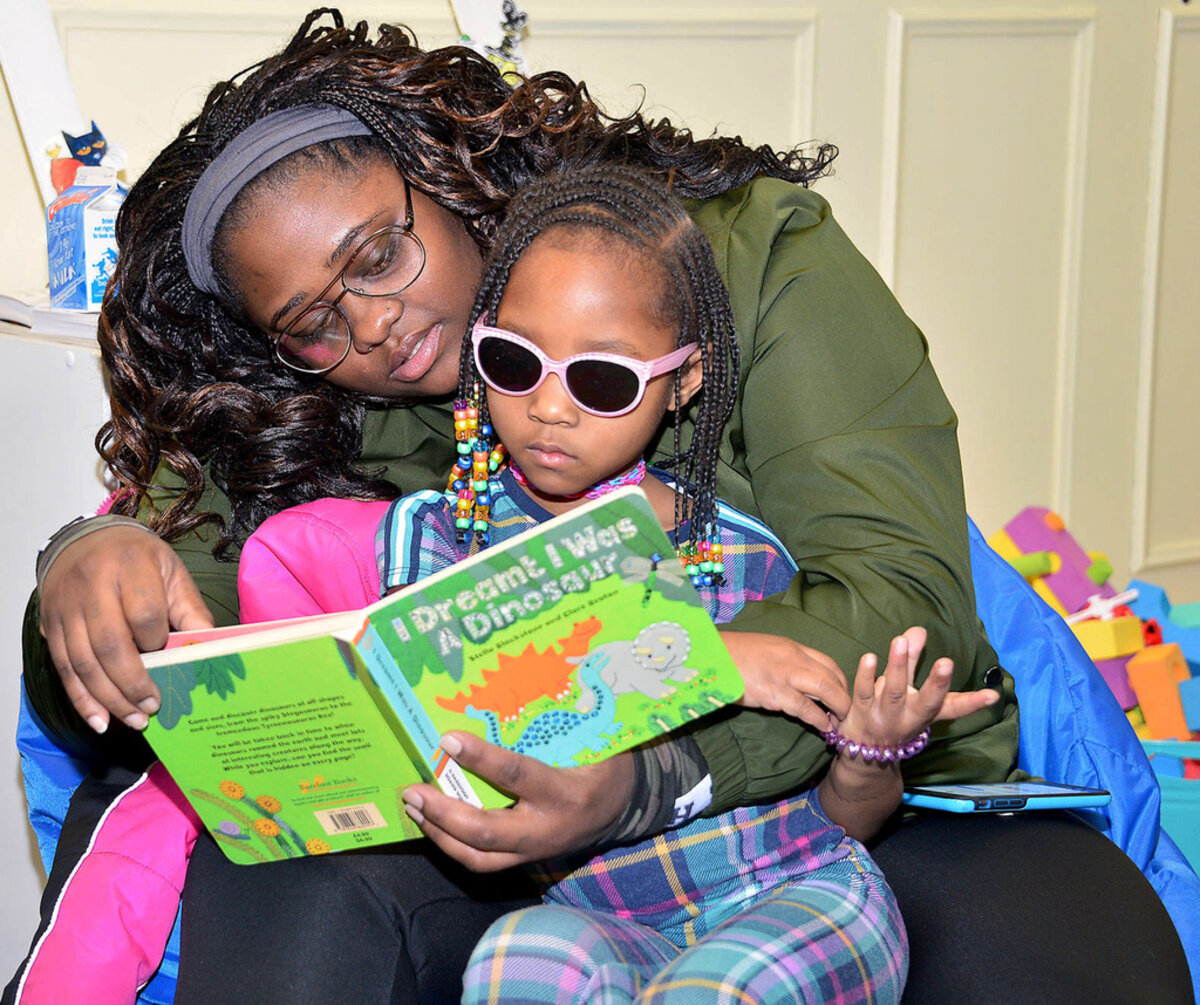

The lockdown’s lesson in reading books aloud

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

For teachers around the world, one of the unexpected lessons of the COVID-19 lockdown has been that schoolchildren stuck at home in virtual learning love to hear books read aloud. Kids missed the close interaction with classmates and teachers. Whether in hearing books read to them or in reading books together over a video link, younger students felt the bonds of belonging. That lesson in learning is now playing out during the summer break and perhaps the next school year.

This summer, for example, West Virginia plans to distribute 200,000 books to children entering first or second grade while also providing an online reading of the books. Numerous authors have relaxed copyright permissions for teachers to read their books online. Libraries have created YouTube channels for book readings. The importance of these innovations cannot be overstated. In the United States, the latest survey shows the average reading scores for fourth and eighth graders have dropped since 2017.

Book reading helps prepare a child for mental liberation from ignorance, fear, and falsehood. With their hunger to listen to books during the pandemic, students have taught educators a valuable lesson.

The lockdown’s lesson in reading books aloud

For teachers around the world, one of the unexpected lessons of the COVID-19 lockdown has been that schoolchildren stuck at home in virtual learning love to hear books read aloud. With no physical classrooms for the last nine or so weeks of the school year, kids missed the close interaction with classmates and teachers. Whether in hearing books read to them or in reading books together over a video link, younger students felt the bonds of belonging and the magic of spoken literature.

That lesson in learning is now playing out during the summer break and perhaps the next school year.

This summer, for example, West Virginia plans to distribute 200,000 books to children entering first and second grade while also providing an online reading of the books. Numerous authors have relaxed copyright permissions for teachers to read their books online. Libraries have created YouTube channels for book readings. And many popular authors of children’s books have posted read-alouds online.

The importance of these innovations cannot be overstated. In the United States, the latest survey shows the average reading scores for fourth and eighth graders have dropped since 2017. Children’s literacy should not suffer during what is called the “COVID-19 slide” in education. In Florida, the governor has announced an additional $64 million in spending for teaching reading skills with the goal of having 90% of students be proficient readers by 2024.

Reading is often viewed as a solitary exercise. But for children, the reading of books aloud is an intimate social experience. Its effect on later success is now widely recognized. The percentage of parents reading aloud during a child’s first three months is up nearly 50% since 2014, according to Scholastic’s latest Kids & Family Reading Report.

Books are “imaginative rehearsals for living,” stated novelist George Santayana. They are also a great equalizer in a diverse society. Book reading helps prepare a child for mental liberation from ignorance, fear, and falsehood. With their hunger to listen to books during the pandemic, students have taught educators a valuable lesson.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Progress that’s always in motion

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 4 Min. )

-

By Elizabeth Mata

It can be discouraging when progress seems to be at a standstill. But as a woman experienced when faced with an unrelenting skin condition, the power of God to heal and lead us forward is unstoppable.

Progress that’s always in motion

At this moment, many aspects of life have been postponed or are at a complete standstill on account of the pandemic. We may wonder when things will get better in regard to such things as health, the economy, and employment.

Everyone wants progress, and rightfully so. I have been thinking about what it means to move ahead, to grow, to progress even when things don’t look so great.

There are so many examples in nature of progress going on unseen to the human eye. For instance, in winter certain plants are actively rooting underground, resulting in beautiful flowers in the spring. The idea that progress can take place where least expected shines through in this Bible verse: “The wilderness and the dry land shall be glad; the desert shall rejoice and blossom like the crocus” (Isaiah 35:1, English Standard Version).

So what can we do when we feel we are in the middle of dry, barren land, a far cry from flourishing in the way we would like to? When I have found myself in situations that didn’t seem to be getting better (and there have been a number over the decades), I have relied on prayer in Christian Science, praying to the one all-powerful God who loves and cares for me and everyone at all times and in all circumstances.

A few years back I experienced a distressing itchy skin condition. Although it wasn’t visible to others, there were times when I couldn’t focus on anything else.

I was praying with the help of a Christian Science practitioner to understand that my real identity was completely spiritual and good because God, our creator, is Spirit and all good. I was striving to truly feel at the core of my being that because God only gives us peace and joy, this was all I could express as God’s deeply loved child. I prayed to understand with greater conviction that because this was the truth about my spiritual identity, it was the authority or spiritual law that governed me every moment.

From my prayers, I frequently felt a sense of peace, the mental sign that healing is taking place. This made God’s presence and power more tangible to me. But I was still distracted by the unpleasant condition. Frankly, I was discouraged because nothing seemed to have changed physically for months.

I have often found such rock-bottom moments turn into wonderful spiritual breakthroughs. Even a momentary glimpse of the futility and limitations of what the Bible calls the carnal mind, or thinking that opposes God’s supremacy and goodness, opens the path forward to healing. Then we are ready to accept God’s, divine Love’s, tender message of our pure spirituality and goodness. This is the ever-present Christ message that animated Jesus and empowered his healing works, which threw off limitations people had been living with, sometimes for many years.

Mary Baker Eddy, the discoverer of Christian Science, wrote, “Progress, legitimate to the human race, pours the healing balm of Truth and Love into every wound” (“No and Yes,” p. 44). How comforting to know that right where frustration and discouragement seem to be screaming, the power of the healing presence of God, divine Truth and Love, is here – the only certain reality for each of us. God as infinite Life is inexhaustible in His outpouring of abundant good for everyone.

This is the basis for true, spiritual progress – evidenced in harmonized, transformed, and healed lives.

That’s what I experienced with the skin condition. One day when I was praying to just feel God’s presence, I had the thought that I did not need to submit to the mental demand, or pull, to define myself as fundamentally material, not spiritual. I saw that this demand was not from God, Spirit, and was therefore mistaken. I could say an unequivocal “no” to it. God as divine Love and Life is always gently impelling us to welcome and live – with divine authority – our true, spiritual nature, expressed in purity and peace.

I suddenly felt my thought moving in a different direction: toward the spiritual foundation of existence, which includes no element of materiality. At that moment, the recurring mental pull to check on, wonder about, or worry over when the condition would change stopped.

How grateful I was for that pivotal point of progress that freed my thought. And soon the condition was completely healed, with no return of it.

As we’re willing to make our God-given goodness our reference point for thinking and living, we will see progress – more evidence of peace and health in our lives.

A message of love

Out of the mist

A look ahead

Come back tomorrow. We’ll look at a pair of trends triggered by the pandemic – farms dumping food, and record levels of hunger – and highlight the ingenuity and heart being applied to addressing both problems at once.

Also, a reminder: To see some fast-moving stories that we’re following, visit our regularly updated First Look page.