- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- As US cases soar, ‘coronavirus detectives’ face new strain

- Why Iranians, rattled by suicides, point a finger at leaders

- Trump hosts Mexican president in meeting of populism and pragmatism

- Addiction, hope, and recovery in the time of COVID-19

- Home theater: With sports on hold, it’s films for the win (video)

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Is the pipeline spigot being turned off?

Over the past few days, three different fossil fuel pipeline projects have, in effect, been shut down at least for now. The details vary, but each case connects to years of effort by local citizens and others pushing for consideration of environmental risks.

On Sunday, Duke Energy and Dominion Energy canceled their planned Atlantic Coast Pipeline for transporting natural gas into North Carolina and Virginia, as opposition and lawsuits pushed up the project’s cost.

On Monday, a federal judge ruled that the Dakota Access Pipeline must shut down until a new environmental review is completed. The Monitor’s Henry Gass covered efforts by Native Americans to prevent this conduit for oil in 2016. Also on Monday, the U.S. Supreme Court rejected the Trump administration’s effort to continue construction of the Keystone XL oil pipeline from Canada to Nebraska. The final outcome of these two pipelines remains to be determined, probably after the coming presidential election.

Even as this moment shows the power of determined individuals, it may also reveal an economic shift. The costs of greenhouse gas emissions to human livelihoods and the planet’s climate are gaining recognition. Meanwhile in a state like North Carolina, solar power can compete with natural gas as an efficient energy source.

Dallas Goldtooth, a Lower Sioux tribe member who helped lead opposition to the Dakota pipeline, on Tuesday retweeted a comment from Andrew McDowell, an official at the European Investment Bank: “Investing in new fossil fuel infrastructure,” Mr. McDowell said, “is increasingly an economically unsound decision.”

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

As US cases soar, ‘coronavirus detectives’ face new strain

Officials call for an army of public health workers who can find, contact, and support those thought to have been exposed to the coronavirus. Some states aren’t prepared.

Since the novel coronavirus began to spread in the United States in February, health departments across the country have recruited and trained armies of contact tracers, workers who locate and speak with people who have been exposed to the virus.

Contact tracing is a tried-and-tested method for quashing outbreaks, but, as cases surge across the South and West, the capacity is buckling, sending a stark warning to other states that were bracing for a fall wave of infections.

In Florida, the state health department has about 1,600 contact tracers, and has contracted a company to provide 600 more. But by one estimation, the state ought to have 33,000 contact tracers. Texas has around 2,800 contract tracers, well below the goal of 4,000 that the state’s governor set in April as a metric for reopening.

“Contact tracing for COVID is primarily going to work well before you get into a huge spike of cases. Right now, with the daily case count [in Florida] it’s unlikely that any health department is going to keep up,” says Marissa Levine, a former state health commissioner in Virginia.

As US cases soar, ‘coronavirus detectives’ face new strain

When a novel coronavirus first began to spread in February, U.S. public health officials reached for a tried-and-tested method: contact tracing. By isolating potential spreaders and finding out who else they may have infected, “coronavirus detectives” try to tamp down outbreaks.

In hard-hit cities like New York and Boston, contact tracers were quickly overwhelmed by the growth in cases, and politicians turned instead to lockdowns to slow transmission and lessen the pressure on hospitals.

Since then, health departments across the country have built up their tracing capacity, training a corps of workers, including students and volunteers, in how to contact people who have been exposed to the virus, and to monitor and support those who isolate themselves.

But as cases surge across the South and West, this capacity is buckling, sending a stark warning to other states that were bracing for a fall wave of COVID-19 infections. Far from quashing outbreaks, tracers in states like Texas and Arizona are playing catch-up, stymied by social norms, political discord, and the dizzying rate of post-lockdown infections. Even California, which has trained thousands of new contact tracers since May, has been caught flat-footed.

Editor’s note: As a public service, all our coronavirus coverage is free. No paywall.

Perhaps nowhere is this tension more acute than in Florida, where a surge in positive cases is blamed on young revelers flocking to bars and beaches and partying with friends and strangers.

“Contact tracing for COVID is primarily going to work well before you get into a huge spike of cases. Right now, with the daily case count [in Florida] it’s unlikely that any health department is going to keep up,” says Marissa Levine, a former state health commissioner in Virginia.

Florida’s state health department has about 1,600 people working on contact tracing and has contracted a company to provide 600 more. In a state of 21 million people, that’s roughly two-thirds of a recommended baseline of 15 tracers per 100,000 people. But when adjusted for Florida’s COVID-19 case count, that ratio rises to 156 per 100,000, or more than 33,000 tracers, according to an online contact tracing workforce estimator at George Washington University.

Texas has around 2,800 contract tracers, compared with a goal of 4,000 that Gov. Greg Abbott set in April as a metric for reopening. That workforce has declined in recent weeks as state workers were deployed to other COVID-19 response jobs, The Texas Tribune reported.

“Not about surveillance”

Ideally, contact tracers will both locate people exposed to an infectious disease and plot the chain of infection back to the source, says Dr. Levine, who directs the Center for Leadership in Public Health Practice at the University of South Florida. “The whole idea is to identify places where people have been congregating and it has been spreading.”

Nationally, the U.S. now has between 27,000 and 28,000 contact tracers, Robert Redfield, the director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, said last month. Some experts have concluded that at least 100,000 tracers are required, and pointed to the success of countries like South Korea and Germany in deploying rapid testing and tracing to contain COVID-19.

In April, Congress allocated $631 million for contact tracing, testing, and surveillance efforts at local health departments, which some have used to train staff or volunteers who can then be called up when cases spike. Others have tapped state workers idled during lockdowns.

But secondments aren’t a substitute for a standing army, says Mike Reid, an assistant professor of medicine at the University of California, San Francisco who has trained more than 4,000 tracers for California’s health departments. In San Francisco “many of our contact tracers are librarians and city attorneys and environmental scientists. Some of them are feeling the pressure to go back to their day jobs,” he says.

For now, San Francisco has told city workers to keep working on contact tracing amid a surge in positive cases in Los Angeles following the lifting of a statewide lockdown in May. Gov. Gavin Newsom said Monday that young adults who believed themselves “invincible” were catching and spreading the virus.

The Bay Area’s caseload has risen more slowly, and tracers are reaching most of those who test positive, but Dr. Reid is watching other hot spots warily. “If the numbers continue to grow we’re going to have to continue to train more people [to contact trace], and that will require greater investment,” he says.

Nearly half of the tracers hired for the Bay Area are Spanish speakers, a reflection of its demographics and of the disease’s unequal toll on minorities. Contact tracers must navigate cultural and linguistic barriers, and build a rapport with people who equate tracing with immigration enforcement and for whom self-isolation could be a crushing burden.

One way to do that, says Joia Mukherjee, the chief medical officer at Partners in Health, a global health nonprofit in Boston, is to ensure you can properly support those whom you ask to isolate, such as finding temporary housing or supplying baby formula. “Contact tracing is about care. It’s not about surveillance,” she says.

A marathon, not a sprint

In Massachusetts, Partners in Health has worked with Gov. Charlie Baker who committed $44 million to build a central COVID-19 tracing force to supplement local health departments. After hitting a peak of 1,900 people, this force has fallen to 400 as the state’s caseload has declined to fewer than 200 a day, but it can scale up again quickly when needed, says Dr. Mukherjee.

Partners in Health is supporting contact tracing at health departments in several other states, including in at-risk communities of color, including agricultural workers in Immokalee, Florida.

Dr. Mukherjee, who has worked for decades on infectious diseases in developing countries, says social trust is always a challenge. What is “uniquely American” in tackling the pandemic “is the erosion of a belief in science and an erosion of trust in government.”

In Palm Beach, contact tracers are only reaching 72% of people who tested positive. (Massachusetts has averaged 90%.) Of their close contacts whose details were shared, tracers were able to contact about half, the county health director said last month, adding that many of the people who were infected had refused to tell tracers where they worked.

As the virus surges in Sun Belt cities, others are only now starting to ramp up contact tracing. In Illinois, Cook County last week unveiled a $41 million initiative for Chicago’s suburbs that would expand its tracing team from 25 to 400 staff, working with universities and community-based organizations. The first cohort is expected to start work in early August, said a spokeswoman for the county department of public health.

That timeline may seem leisurely, as states reopen and COVID-19 hot spots flare across the South and West. Epidemiologists say building tracing capacity and getting the message out to at-risk communities is simpler and more effective during lockdowns than after, when social interactions multiply.

Still, Dr. Mukherjee says it’s never too late to start. Pandemics are marathons not sprints, and when tracers and health systems are put in place, “we can jump on outbreaks much more rapidly,” she says.

Editor’s note: As a public service, all our coronavirus coverage is free. No paywall.

Why Iranians, rattled by suicides, point a finger at leaders

The reasons for suicide are complicated, but something is driving an increase in the number of Iranians who take their own lives. Many see rising despair as an indictment of the political establishment.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Decades after the 1979 Islamic Revolution seized power in the name of “social justice” for the poor and “oppressed,” Iran is battling a surge of suicides seen as a barometer of the ever-widening gap between the political leadership and society.

Accelerating a long-term trend, attempted suicides have leaped 23% in the past three months. Calls to action have been galvanized by recent cases that appear designed to send dramatic messages of the need to ease despair. Within days last month, for example, three very public suicides gripped Iran, with graphic images going viral on social media.

“Hopelessness is the driving force behind almost all the attempted suicides I have been dealing with,” says a social worker in western Iran who is trained to help people with suicidal thoughts. “The important point here is that the new cases are mostly meant to send a message of revenge against someone or something,” says the social worker. “They represent macroscopic situations of desperation, which are increasingly crippling certain sections of the society.

“It is becoming an epidemic because those who follow suit feel like, ‘Yes, we can send the same message. ... At least we do something this way.’”

Why Iranians, rattled by suicides, point a finger at leaders

First the wounded veteran, then the unpaid security guard, then the hungry child.

The powerful images of hopelessness came one after another, creating mounting waves of shock for Iranians who may have thought themselves inured to tales of desperation, destitution, and political angst.

Yet decades after Iran’s 1979 Islamic Revolution seized power in the name of “social justice” for the poor and “oppressed,” and amid deepening economic collapse, Iran is battling a surge of suicides seen as a barometer of the ever-widening gap between the political leadership and society.

Accelerating a long-term trend, attempted suicides have leaped 23% in the past three months, marked by “chain suicides” and “more horrifying methods [carried out] before the public eye,” wrote sociologist Mohammad Reza Mahboubfar in the conservative Jahan-e Sanat newspaper.

Authorities say official statistics are only the “tip of the iceberg.” But calls to action have been galvanized by recent cases that appear designed to send dramatic messages of the need to ease despair.

Within days last month, for example, three very public suicides gripped Iran, with graphic images going viral on social media as they added to the most recent annual toll of more than 5,000 Iranians taking their own lives.

In a dispute over a small loan, Jahangir Azadi, a wounded veteran of the 1980s Iran-Iraq War – an almost sacred category of citizens in the Islamic Republic – set himself alight in front of the offices of the Foundation of Martyrs and Veterans Affairs in western Iran.

Days later, following late salary payments, Omran Roshani-Moghaddam, a security guard for an oil company, hung himself from crossbeams attached to a large metal tank in an oil field.

“I have nothing left to feed my family with, I have no bread to take home,” he had told his boss, according to co-workers in southwest Iran. The scene infuriated Iranians on social media for its stark contrast of utter poverty, explicitly juxtaposed against Iran’s immense oil wealth.

And days after that, 11-year-old Armin Moradi was buried after deliberately overdosing on drugs, pushed to the edge by “poverty, destitution, and disillusionment,” according to the Imam Ali Society of Students Against Poverty. In his home food was “basically non-existent,” with no trace of “dishes or spoons.”

“Message of revenge”

Those cases proved unsettling even for Iranians used to bad news, who have been buffeted by years of homegrown economic misrule, exacerbated by ever-more-staggering U.S. sanctions and now the disruption of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Since late 2017, waves of angry protests against low and unpaid wages, soaring prices, and corruption have become a feature of Iranian life. So have the lethal crackdowns that have left hundreds dead.

“Hopelessness is the driving force behind almost all the attempted suicides I have been dealing with,” says a social worker in western Iran who asked not to be identified.

“The important point here is that the new cases are mostly meant to send a message of revenge against someone or something,” says the social worker, who has been trained in a government program to help others cope with suicidal thoughts.

“In the [veteran’s] self-immolation, the guy probably thought, ‘Well, by doing this I am ending my life, but at least I can send a bigger message to the whole country,’” he says. “The new suicides are becoming stronger symbols. They are not simply personal files. They represent macroscopic situations of desperation, which are increasingly crippling certain sections of the society.

“It is becoming an epidemic because those who follow suit feel like, ‘Yes, we can send the same message. ... At least we do something this way,’” adds the social worker. It’s about “causing some sense of guilt in a beloved person, a parent, a boss, but more importantly – and on a larger scale – the authorities in the ruling system.”

Iranian officials appear to be getting that message, up to a point.

Prevention plan

The National Suicide Prevention Plan was announced in December by Ahmad Hajebi, a Ministry of Health director, who said it would expand research programs and reduce access to means of suicide. In February he told journalists, “We need to control the rising trend.”

Police announced last month that glass barriers would be installed on many platforms in Tehran’s sprawling subway system, to prevent people from throwing themselves in front of trains.

Already a suicide hotline – which officials credit with averting 8,500 deaths in 2017 alone – is in service. Police and other Iranian first responders also field teams trained to stop suicides, and large government charities conduct workshops on counseling tactics and suicide prevention.

But officials recorded 5,143 suicide deaths in the Iranian year that ended in March, an 8% increase over the previous year. The “growth rate over the past decade raises serious alarm” and requires action “with urgency and immediacy,” Masoud Ghadi-Pasha, a deputy director at the Legal Medicine Organization, said in late June.

In his report at that time, Mr. Mahboubfar, the sociologist, warned that “chain suicides” are a “wide-reaching tremor” that can quickly lead to “unrest more widespread than what we witnessed in recent years.”

That sentiment has echoed widely, especially amid a high-profile anti-corruption campaign that underscores for many how the Islamic Republic has strayed from its early days, when Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini declared: “Only those who have tasted poverty, deprivation, and oppression will stay with us to the end.”

The surge of poor people killing themselves over relatively small amounts of money comes “when there is talk of fraud cases in which we can’t even count the digits,” tweeted pro-reform journalist Ehsan Soltani. “Let’s keep these days in our minds, days when the call of the destitute fell on deaf ears [of leaders].”

Eroded safety nets

That growing inequality has been especially felt by veterans, who occupy an elevated status in Iran but have seen their state-supported safety nets erode for years. Last summer and fall, in four separate incidents, three veterans and the son of a war “martyr” from the shrine city of Qom burned themselves to death.

The national narrative portrays them “not just veterans of a war, but actual defenders of the revolution. So when they open up their mouths and start critiquing in the ways they do, it can be pretty damning,” says Narges Bajoghli, an Iran expert at the School for Advanced International Studies at Johns Hopkins University in Washington who notes that concerns about rising veteran suicides date back a decade or more.

“Part of it is that they don’t have the ability anymore to provide for their families,” a fact that has “created more and more anxiety and desperation,” says Ms. Bajoghli, author of “Iran Re-Framed: Anxieties of Power in the Islamic Republic.”

The result, she says, especially for disabled veterans, is there’s no choice but “to go out into the street and start begging – and that’s just not acceptable to them as a possibility, because of their role [as] defenders of the revolution.”

To Abbas Abdi, who was among the students who took American diplomats hostage in 1979, but later became a pollster and regime critic who spent time in prison, the suicides magnify a broader failure.

“There is no proper understanding of the dangerous potential as local officials are more concerned about ... fallout than tracing the roots of what led to those tragedies,” Mr. Abdi wrote in the reformist Etemad newspaper in mid-June.

He notes the irony of war veterans and “destitute laborers” committing suicide – despite a revolution carried out in the “name of the oppressed” – “at a time when others in the top echelons are abusing power and receiving whopping bribes. ... How could such a system claim lawfulness?”

That assessment is no surprise to one professional journalist in Tehran, who has recorded the deleterious impact of rising prices, and now the pandemic, on Iran’s social fabric.

“If you see a janbaz [“self-sacrificer” veteran] set himself on fire; if you see a worker hang himself in an oil and gas zone; it is a symbol of poverty and misery alongside wealth – a wealth that people believe is not spent on [them] and is sent to countries like Syria, Lebanon, and Palestine,” says the journalist.

“People are not happy in Iran. They have no hope for the future,” he says. “I think this number of suicides is a message to [Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali] Khamenei, the message that says, ‘We want to have a normal life and no more.’”

The journalist recalls a conversation in a shared taxi last week, when the driver asked a young woman how she was doing.

“We are all dead,” the 21-year-old replied. “No job, no money, no fun, and no hope, so this is not life.”

Trump hosts Mexican president in meeting of populism and pragmatism

If, as a recent poll shows, Mexicans dislike Donald Trump, how can they support President Andrés Manuel López Obrador’s trip to Washington? Essentially, they like what AMLO can bring home.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Almost uniformly over the past week, Mexico’s intellectuals and media elite have lamented the spectacle of a Mexican president ingratiating himself with an American president that 7 of 10 Mexicans strongly dislike. But what many Mexicans say with a shrug is that they also know their country is better off when relations with the U.S. are good.

Which explains why a majority of Mexicans said in a poll they supported President Andrés Manuel López Obrador’s plans to meet Wednesday with President Donald Trump at the White House.

“If López Obrador tells them Mexico is better off because we now have better relations with the United States and his trip will be a sign of respect for Mexico, people say, ‘OK, López Obrador knows what he’s doing,’” says Jorge Chabat, a professor at the University of Guadalajara.

Indeed, a new pragmatism has started to take hold of a lopsided binational relationship, some analysts say.

“Over the last three years, not only have the U.S. and Mexico been de-escalating things, but they’ve actually on many levels been improving the relationship,” says Ana Quintana, an analyst at the Heritage Foundation in Washington. “That has happened because it’s in both countries’ interests.”

Trump hosts Mexican president in meeting of populism and pragmatism

In a late June poll in the Mexico City newspaper El Financiero, 70% of Mexicans said they disapproved of U.S. President Donald Trump.

No surprise there. Mr. Trump came into office denigrating Mexicans as criminals and rapists and has undertaken the building of a border wall to divide the two neighboring countries. The project injures Mexicans’ image of themselves, and for millions of Mexican families, makes connections between members living on both sides more difficult.

More surprising was another finding: Almost as many Mexicans, about 60%, supported President Andrés Manuel López Obrador’s plans to travel to the White House to meet with Mr. Trump.

After taking a commercial flight to Washington to reduce costs, Mr. López Obrador was scheduled to have his meeting in the Oval Office today, followed by a “working dinner.”

What might seem like a head-scratching discrepancy among Mexican citizens is actually a reflection of a realism about their powerful northern neighbor that has only grown as Mexico’s economic well-being has become increasingly interlinked with that of the United States.

Mexico’s intellectuals and media elite may lament – as they have almost uniformly over the past week – the spectacle of a Mexican president ingratiating himself with an American president that 7 of 10 Mexicans strongly dislike. But what many Mexicans say with a shrug is that they also know their country is better off, especially economically, when relations with the U.S. are good, no matter who is in the White House.

“I think the answer to what might seem like a glaring contradiction has to do more than anything with López Obrador himself and the fact that many people still like him despite the very bad situations of the economy and security, and the pandemic,” says Jorge Chabat, a professor of Pacific studies at the University of Guadalajara.

“For sure Mexicans don’t like Donald Trump,” he adds, “but if López Obrador tells them Mexico is better off because we now have better relations with the United States and his trip will be a sign of respect for Mexico, people say, ‘OK, López Obrador knows what he’s doing.’”

Indeed, a new pragmatism has started to take hold of a lopsided binational relationship that has never been easy but which has faced new challenges under Mr. Trump, some analysts say.

“Over the last three years, not only have the U.S. and Mexico been de-escalating things, but they’ve actually on many levels been improving the relationship,” says Ana Quintana, senior Latin America and Western Hemisphere policy analyst at the Heritage Foundation in Washington. “That has happened because it’s in both countries’ interests.”

It is with that same pragmatism that Mr. López Obrador braved harsh domestic criticism to sit down in Washington with a U.S. president who had bad-mouthed Mexico like no other. Mexico’s economy, already hurting, has been laid out flat by the pandemic. The leftist-populist leader may not like it, but he knows that the only way to an economic recovery is on the coattails of U.S. economic growth.

Campaign rally of one

Mr. López Obrador came into office in December 2018 vowing to scuttle the neoliberal economic model that had given Mexico the North American Free Trade Agreement. But there he was Wednesday joining Mr. Trump in marking the July 1 entry into force of the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement. The USMCA, as it is known, is an updated NAFTA that promises to strengthen the links among the three North American economies.

Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau was also invited to the celebration but declined, claiming previous commitments and citing the coronavirus pandemic. (Unlike the U.S., Canada has done a good job of controlling the outbreak.)

From the White House perspective, the visit by Mr. López Obrador – better known by his initials, AMLO – is an opportunity for a Trump reelection campaign rally of one. Indeed, the visit allows Mr. Trump to highlight the fact that with Mr. López Obrador, the president has got pretty much what he wanted from Mexico – especially on immigration – and at very little cost.

Mexico under AMLO has sent its National Guard to the southern border with Guatemala to impede Central Americans headed to the U.S. (Mexicans no longer make up the bulk of migrants crossing into the U.S. from Mexico.) And it has accepted to become a kind of holding pen for would-be U.S. asylum seekers.

Indeed, many Mexican migration experts say that, in effect, AMLO has given President Trump a version of the wall that candidate Trump insisted Mexico would pay for.

“Basically, Donald Trump has declared what he wants, and López Obrador has given it to him,” Professor Chabat says. “López Obrador is very afraid of Trump because he knows he can do things to really hurt Mexico.”

But in taking immigration measures that pleased Mr. Trump, note some experts in North American affairs, Mr. López Obrador is also keeping happy the growing number of Mexicans who see the Central Americans crossing their territory as a burden.

“At first when the Central American caravans were crossing into Mexico, AMLO sounded very much like most Mexicans, saying these are poor people and we must help them,” says Richard Feinberg, a professor of international political economy at the University of California at San Diego’s School of Global Policy and Strategy. “But then when they kept coming, the welcome started wearing thin.”

It was at that point that Mr. López Obrador started taking steps that pleased Mr. Trump, Professor Feinberg adds. “Suddenly there was a commonality between U.S. policy and Mexican national interests,” he says. (It’s also true that the White House threatened to impose stiff tariffs on Mexican goods if the waves of humanity from Central America weren’t stopped.)

Points in common

Mr. López Obrador’s “Mexico First” immigration policies are just one of the ways that the two odd amigos resemble each other, Professor Feinberg says.

Both leaders are inward-focused and appear to have little interest in the outside world, he says. “Trump gets out of international meetings every chance he can,” he notes, and for López Obrador, “this trip [to Washington] is his first out of the country.”

Moreover, Professor Feinberg says an “anti-elitist populism” runs deep in both men. Whereas Mr. López Obrador speaks frequently of “the mafias of corrupt power” – by which he means the opposition political parties – and his “adversaries” in the media, Mr. Trump rails against the “deep state” and the “enemy of the people” press, he says.

Professor Feinberg says another reason Mr. López Obrador was even able to consider visiting the White House is that Mr. Trump appears to have redirected his demonization of Mexico elsewhere. “Donald Trump always needs an enemy, but this time around it looks like China will be that enemy, not Mexico,” he says.

Yet while the two leaders may have decided they actually kind of like each other, Ms. Quintana of Heritage says she hopes for more from the U.S.-Mexico summit than just a celebratory launch of the USMCA.

She is calling for development of a North American “economic and health recovery plan” that would focus the three economies on stimulating growth to meet regional needs. In particular, she wants to see a focus on developing and strengthening health-materials supply chains so that North America is never again left at the mercy of Chinese and other producers.

“We need to sit down together and come up with a plan for how the three North American trade partners can work together to prevent the kinds of trade and supply-chain shutdowns we saw” in the early months of the outbreak, she says. “That kind of coordination should be part of a modernized trade agreement.”

Addiction, hope, and recovery in the time of COVID-19

Recovery is about reclaiming a life. Many have proved that treating an addiction is a pandemic possibility, even as they uplift their peers.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 8 Min. )

-

By Catherine McGloin Contributor

-

Sarah Matusek Staff writer

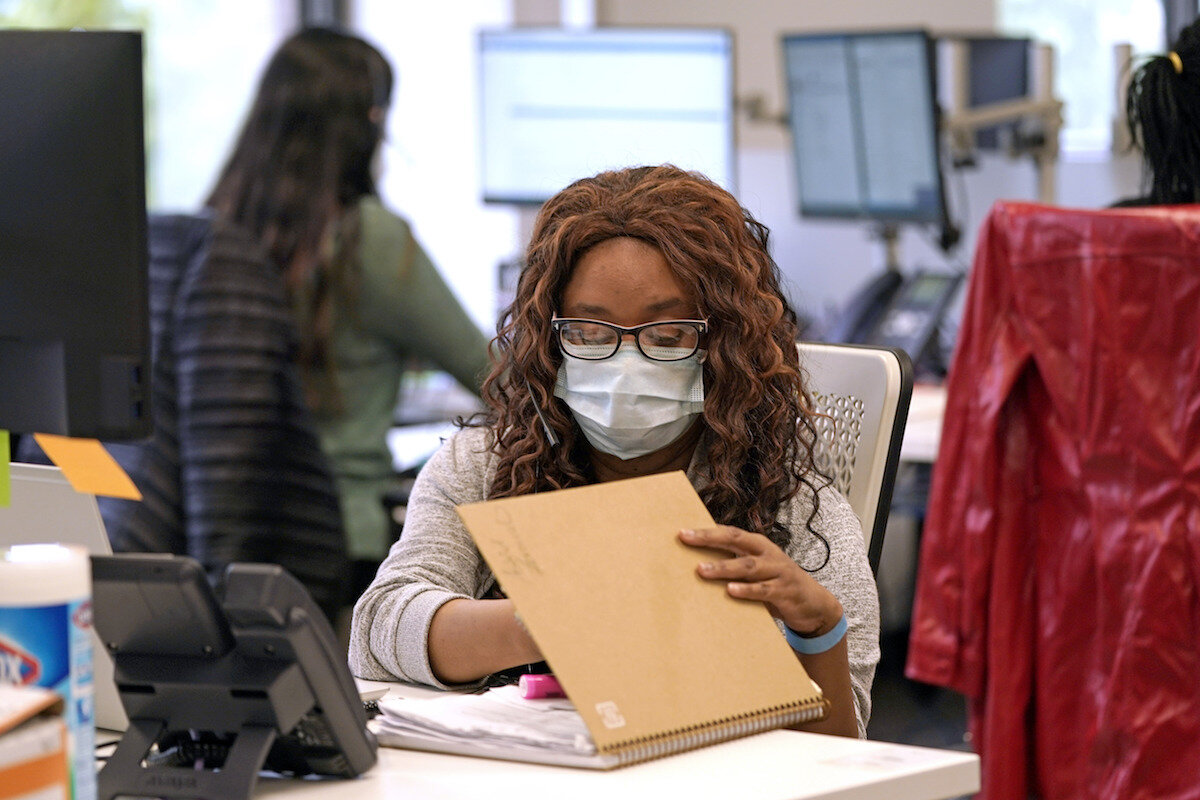

New York recovery coach Jen Cutting urges meeting people where they’re at. “I feel like the mom on the sideline, cheering for them,” she says of her “recoverees.”

“I just want them to be successful and happy and sober and alive.”

Amid concerns of increased anxiety and isolation during the pandemic, technology has helped many in recovery from addiction hold onto social support and treatment, through an expansion of online mutual support groups, telehealth, and apps.

Privacy and access issues remain, and more research is needed to understand the efficacy of telehealth and other digital tools. But for some who need help, their willingness to adapt underscores a message advocates have pressed all along: Recovery is possible.

“I just want to give a message of hope,” says Sarah Rollins, a Michigan social worker.

In April, West Virginia’s Office of Drug Control Policy launched its Connections app, whose features include digital cognitive behavioral therapy. An effort to roll it out failed five years ago, as the number of fatal overdoses in the state continued to rise.

As the department’s Executive Director Robert Hansen says, “It may have been because it was way ahead of its time.”

Addiction, hope, and recovery in the time of COVID-19

Four summers ago, Frederick Shegog ate a bag of donuts from a dumpster. Homeless and hungry in downtown Philadelphia, he says the sweets replaced a meal he’d have to buy with the last of his cash.

“I wanted that money to save, because I wanted to drink and hopefully I wouldn’t wake up,” he says. Living with an alcohol use disorder, Mr. Shegog had tried 20 different rehabs without success.

Passed out three days later on the street, he says a man woke him with a cup of water.

“You’re not dying today,” he recalls the stranger’s words.

Mr. Shegog celebrated four years sober last month. He graduated from Delaware County Community College in May with high honors and straight A’s. The motivational speaker credits his success to his faith in God, and the man who “saved my life” with a call to 911. Virtual resources have helped sustain his recovery during the pandemic, he says, as he joined remote 12-step meetings and therapy for the first time.

Editor’s note: As a public service, all our coronavirus coverage is free. No paywall.

“I gotta be honest – I don’t want to get back to in-person meetings,” says Mr. Shegog, who likes logging on from the comfort of home.

“I can be in a meeting in New York, and I’m in Philadelphia. … It’s opened the world up to be in places I never would’ve been in, to meet people I would’ve never met.”

Amid concerns of increased anxiety and isolation during the pandemic, technology has helped many in recovery hold onto social support and treatment through online mutual support groups, telehealth, and apps. Overcoming the disease of addiction is never easy, and relapse is common. But for some who need help, their willingness to adapt affirms advocates’ message from all along, pandemic or not: Recovery is possible.

“I just want to give a message of hope,” says Sarah Rollins, a Michigan social worker. “This is not something that has to be a life sentence.”

Need predates pandemic

Stigma persists, but substance use disorder (also called addiction, when severe) is a treatable disease. Even before the outbreak, more Americans required help for substance use than received it. An estimated 20.7 million people over the age of 11 needed treatment for substance use in 2017, according to government data. Within a year, only 4 million people received treatment.

Health experts warn the pandemic may lead to increased substance use and mental health issues.

“The concern is that we may then see an increase in overdoses, an increase in alcohol withdrawal, an increase in active substance use disorders,” Yngvild Olsen, vice president of American Society of Addiction Medicine’s board of directors, said in April. Reported spikes in opioid-related overdoses across several states confirm this concern.

The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration estimates nearly 58 million Americans were already living with a mental or substance use disorder, or both. Well Being Trust, a mental health foundation, projects the pandemic will cause up to 75,000 “deaths of despair” from alcohol, drugs, or suicide.

While for many, physical distancing has impeded access to resources, some service providers credit an expansion of telehealth – and insurance coverage of it – as lowering barriers to treatment during the pandemic. Emergency government deregulation of access to treatment medication has helped, including relaxed rules on reaching clinicians remotely.

While common, relapse doesn’t mean treatment has failed – around 40% to 60% of people with substance use disorders relapse, says the National Institute on Drug Abuse. But relapse can be dangerous. Jen Cutting, a certified recovery peer advocate in Walton, New York, says she’s lost several acquaintances to fatal overdoses in recent weeks, including “recoverees” she personally mentored.

Besides her cat, Thumbelina, Ms. Cutting has lived in lockdown alone. She says she learned to cope with isolation while incarcerated on drug charges – especially those 65 days in solitary. Ms. Cutting has spent over a decade in recovery from heroin, nearly four years from methamphetamine. Recovery has bloomed a relationship with her 8-year-old daughter, whom she had in prison.

As a recovery coach, Ms. Cutting urges her recoverees to reach out day or night.

“I love all my people. I feel like the mom on the sideline, cheering for them,” she says. “I just want them to be successful and happy and sober and alive.”

Beyond access to evidence-based treatment, “Social support is incredibly important,” says Quyen Ngo, executive director of the Butler Center for Research at the Hazelden Betty Ford Foundation. “Social support around managing cravings, managing urges, understanding that there may be triggers in the environment that individuals may not be able to get away from at this point because we’re all sheltering in place.”

Connecting with peers can help those trying to hide their addiction and use alone, says Ms. Rollins, senior social worker at University of Michigan’s Addiction Treatment Services in Ann Arbor, who has led virtual therapy during the pandemic.

“One of the biggest reasons for social support is it decreases the shame. It increases accountability,” she says. “No one gets better shaming themselves.”

Though nothing fully replicates meeting in person, stay-at-home orders have made mutual support groups like Alcoholics Anonymous proliferate online. SMART Recovery, a secular abstinence-oriented alternative to 12-Step programs like AA, has also continued meetings remotely.

Gerardo Matamoros, volunteer executive director of SMART Recovery NYC, launched the national organization’s first online Spanish-language meeting during the outbreak after mulling the idea for six years. He says the ease of facilitating Zoom meetings in English, despite a slight decline in local attendance, inspired him to commit.

“I’m telling you – silver lining,” says Mr. Matamoros. “It’s been very exciting to start that, and to grow despite what’s happening.”

These groups aren’t subject to health regulations, however, and privacy issues have surfaced over apps that are insecure. In Philadelphia, Mr. Shegog has witnessed multiple Zoom-bombers invade meetings that weren’t password-protected.

“Why would you not prepare when you know people are in here sharing their deepest, darkest, most painful things they’ve ever been through in their life?” he says.

In response to the pandemic, treatment provider Hazelden Betty Ford sped up its rollout of RecoveryGo early this year to reach more clients with mobility issues or in remote areas. The health-privacy-law-compliant platform is currently used for virtual intensive outpatient and mental health programs in nine states.

Attendance spiked when the remote offering was introduced, “due to the concerns of elevated anxiety and boredom and isolationism,” says addiction practitioner Terry Gerlach in Naples, Florida, who leads virtual counseling sessions on the app. “We’re probably talking a lot more about relapse prevention strategies.”

Still, there are success stories. Ms. Rollins, who runs therapy sessions for adolescents and adults, says it’s been “incredible” watching several maintain sobriety during the outbreak, especially while navigating graduations and job hunts.

“Fully present”

Outside Tacoma, Washington, Clarissa Heneghen relies on her Instagram sober community to stay on track – even as she mutes a mounting number of alcohol-related posts that she finds triggering.

COVID-19 has prompted her to check in more frequently with other friends in recovery she’s met on the app. She says those connections promote accountability and remind her of her progress: one year sober.

Her sobriety has allowed her to better address the emotional needs of her three children – all under the age of 10 – as the crisis adds new stressors to home life.

“I feel like if I had been drinking during this, I would have been more annoyed and frustrated” with the kids, says Ms. Heneghen.

“Now we can have conversations. I can be fully present.”

Certain apps have been developed and rolled out with more urgency during the pandemic, while meditation and mindfulness apps already on the market and designed to help ease anxiety – like Headspace and Calm – are offering some of their content for free.

West Virginia’s Office of Drug Control Policy has been working with app developers CHESS Health, launching the Connections app in April. The evidence-based app provides digital cognitive behavioral therapy, moderated peer discussions, classes, and motivational content for people in recovery.

“We kept thinking, what can we do during the pandemic, and part of recovery is connectedness and social interaction,” said Robert Hansen, the department’s executive director.

They tried to launch a similar service about five years ago, as the number of fatal overdoses continued to rise in the state, the biggest spike being in fentanyl-related deaths. “It just never took hold,” says Mr. Hansen. “It may have been because it was way ahead of its time.”

The time may just be right during a pandemic. Recently released to treatment providers, Mr. Hansen hopes to have the app available in popular app stores for anyone to download.

“It’s not a replacement for group therapy and in-person treatment, but it’s another positive,” says Mr. Hansen.

Limited research on telehealth, which predates the pandemic but has significantly expanded since, suggests benefits like better addiction treatment retention. Experts say more evaluation is needed to gauge what virtual resources have worked.

“As with many telehealth innovations, growth may occur before the evidence base is strong,” comment authors in the Journal of American Medical Association Network.

Still, not everyone has a computer, cellphone, or internet connection to engage, much less stable housing. Access to technology “is an issue for many communities, including rural communities where there are also a number of health disparities because of access to good health care of even proximal health care,” said Dr. Ngo.

With limited internet connection and access to technology, Mr. Hansen similarly struggles to reach people in rural West Virginia and worries about the efficacy of technology-based aids to recovery. “There is no easy answer,” he says.

In whatever way connection is possible, Ms. Cutting in New York urges meeting people where they’re at. “Sometimes it’s just seeing a friendly face, or sharing a joke,” she says.

“You can share something that might save someone else’s life.”

If you or someone you know is struggling with substance use, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration offers a range of resources. You can also call the national hotline at 1-800-662-HELP (4357).

Watch

Home theater: With sports on hold, it’s films for the win (video)

Americans are still awaiting the return of home runs and field goals in stadiums. In the meantime, film critic Peter Rainer shares his top picks for films that capture athletic drama. As he puts it, “Movies and sports were made for each other.”

Top 5 sports films to watch while social distancing

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

New flag, new beginning

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

During the past six weeks of protest marches across the United States over police brutality and racism, statues of Confederate generals and politicians have fallen. All the while, Black people in America cling to a fragile hope. They wonder, will anything really change this time?

One answer may have come from the unlikeliest of places: Mississippi.

On July 1 the Magnolia State retired the last state flag to include the Confederate battle emblem in its design. A commission will develop a new flag in time for voters to consider it on the November ballot. Seldom will the creation of a new symbol carry so much healing potential. In a state stained by the country’s darkest threads of slavery, segregation, and racist violence, the people of Mississippi have an opportunity to weave in cloth a new statement of equality, liberty, and democracy.

Mississippi hoisted its newly retired state flag 30 years after the Civil War, in 1894. It was for Black Mississippians a symbol both of terror and economic suppression. As the United States moves through a difficult summer of struggle over racism, Mississippi’s step may provide a measure of the nation’s ability to find atonement and reconciliation.

New flag, new beginning

During the past six weeks of protest marches across the United States over police brutality and racism, statues of Confederate generals and politicians have fallen. Countless conversations about diversity and equality have been started within companies and newsrooms. Bills have been drafted and police reforms debated.

All the while, Black people in America cling to a fragile hope. They are exhausted by the daily experience of racist behaviors, systemic inequalities, and – perhaps most of all – the constant burden to assert their right to live in a fair and just society. Will anything really change this time?

One answer may have come from an unlikely place: Mississippi.

On July 1 the Magnolia State retired the last state flag to include the Confederate states battle emblem in its design – a blue cross saltire with stars on a red background. A commission will develop a new flag in time for voters to consider it on the November ballot.

Seldom will the creation of a new symbol carry so much healing potential. In a state stained by the country’s darkest threads of slavery, segregation, racist violence, and mass incarceration of Black men, the people of Mississippi have an opportunity to weave in cloth a new statement of equality, liberty, and democracy.

Mississippi hoisted its newly retired state flag 30 years after the Civil War, in 1894, at a time when veterans of the Southern cause were dying off and two years before the Supreme Court’s Plessy v. Ferguson decision would enshrine segregation as law for decades to come.

The 1894 flag was for Black Mississippians a symbol both of terror and economic suppression. More than 500 Black men were lynched under its colors, according to the Tuskegee Institute. It waved as 18 activists were killed in the state during the Civil Rights movement of the 1950s and '60s. It flew as more than 130 Confederate monuments were erected.

The state with the highest African American population by percentage, Mississippi has ranked worst in poverty rates and educational standards among Black people year after year. Between 1920 and 1970, nearly 500,000 Black Americans born in Mississippi fled to St. Louis and Chicago, according to US Census Bureau data.

But among those who left to find better lives elsewhere, Black writers and artists nonetheless acknowledged the state’s enduring hold on them with lament and longing.

Changing a flag means reimagining the identity of the people it represents. When South Africa replaced apartheid with democracy, its new flag combined the colors of the new ruling African National Congress and those of the previous colonial powers.

Five years ago New Zealand considered adopting a new flag that would replace the Union Jack with the frond of a silver fern, a plant found only in that island nation, and long seen as a symbol of its identity. It was meant to emphasize indigenous Maori values over the colonial past. Voters opted to retain the old banner, but the national conversation was enlightening.

As the United States moves through a difficult summer of struggle over racism, Mississippi may provide a measure of the nation’s ability to find atonement and reconciliation. The state can draw on the unifying effect of its deep cultural riches, from its music and poetry to its food and football.

Through facing up to centuries of pain and division, Black and white Mississippians can forge an identity of shared affection for the natural beauty and cultural contributions of their state. Fluttering in magnolia-scented breezes, a new emblem of true fellowship would celebrate the dignity and worth of all Americans.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

‘Underlying conditions’ that heal

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 2 Min. )

-

By Kurt Hochstein

It can sometimes seem that our health is at the mercy of forces beyond our control. But the idea that we are God’s pure and whole spiritual offspring can bring renewed health and harmony into our lives.

‘Underlying conditions’ that heal

We often hear of what are described as “underlying conditions” that impact our health. It can seem that our health and lives are at the mercy of forces outside of our control, that we are susceptible to breakdown or disorder.

As I thought about this recently, the following questions popped into my thought: What truly are our underlying conditions – the foundation of our being – in the first place? Are those conditions wholly physical, or is there something more to us?

To find answers to weighty questions such as these, I’ve found it invaluable to turn to the Bible. There we read how Christ Jesus and his followers viewed man as more than what we see with our eyes.

For instance, the Apostle Paul spoke of “walk[ing] not after the flesh, but after the Spirit,” and added, “Ye are not in the flesh, but in the Spirit” (Romans 8:1, 9). Before him Christ Jesus made clear: “It is the Spirit which gives life. The flesh will not help you” (John 6:63, J. B. Phillips, “The New Testament in Modern English”).

These ideas are echoed in “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” the primary text on Christian Science by its discoverer, Mary Baker Eddy. She writes, “Think less of material conditions and more of spiritual” (p. 419).

All of this points to the idea that Spirit, God, is the only reality, the only true source of our existence and selfhood, and that we are fundamentally spiritual, not material. Matter is the counterfeit of Spirit. It is an unreliable and untrustworthy source of information about our true, spiritual condition as God’s children.

Turning to God, rather than matter, to understand our real nature was what helped me a few summers back when I experienced a persistent bruise on one of my legs. After a week, the condition had deteriorated and included an unsightly discharge of fluid.

I realized my attention was focused entirely on the appearance of the leg, whereas the way forward was to affirm what was spiritually true about myself. I knew from previous healings in Christian Science that doing so would bring harmony and healing.

I reasoned that only Spirit, God, could be trustworthy as the source of my life, because Spirit is all-powerful, all-loving, and ever present. Divine Spirit is also eternal and perfect, and the qualities of strength, love, and wholeness are expressed in us.

This brought a renewed sense of confidence, which was further bolstered by another passage in Science and Health: “God is everywhere, and nothing apart from Him is present or has power” (p. 473). The injury was clearly “apart from” God, who is entirely good, and therefore not a legitimate condition in me.

I continued praying with these ideas, and within a day or so the leg returned to its normal, healthy condition.

Each of us can experience the relief and healing that comes from recognizing that our underlying conditions are wholly spiritual, untouched by any material circumstances, and forever maintained flawlessly by our divine Father-Mother, God.

A message of love

Cocooning

A look ahead

Thanks for joining us today. Coming in tomorrow’s Daily: the efforts of one Black mom to ensure the safety of her sons.