- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- With federal agents off the streets, Portland protesters refocus

- Karen Bass on women, politics, and this moment in history

- In Israel, coronavirus brings out a new generation of protesters

- Who’s really inside America’s jails? (audio)

- Embattled TikTok: Behind the dance-duels, a platform for youth activism

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

British father takes gardening to new heights with a giant sunflower

As the lockdowns started in March, Douglas Smith’s 4-year-old son had a request: Let’s grow a sunflower as “big as our house.”

You may already know that pandemic gardening is a thing. You know this because your neighbor keeps leaving zucchini the size of scuba tanks on your doorstep.

This past spring in the Northern Hemisphere, about the time that toilet paper became scarce, a new backyard farming movement began. It started as a hedge against food shortages. Burpee Seeds was so swamped that it halted orders for a few days in April to catch up. Nurseries and garden centers are still doing a booming business. But sales have gone way beyond the apocalyptic preppers.

Gardening has emerged as the ideal break from Zoom meetings. Weeding is therapeutic. The raised bed has replaced the day spa as a source of solace and rhapsodic contentment. “I found love in my garden and I honestly never expected it to get like this, but I’m so blessed. It’s so rewarding,” first-time gardener Nyajai Ellison told ABC News in Chicago.

Meanwhile, in the village of Stanstead Abbotts, England, Mr. Smith took his son’s request to heart. He ordered sunflower seeds, and started watering – twice a day. He now has a 21-foot-tall sunflower towering over his two-story house, reports SouthWest Farmer.

How big is a father’s love for his son? As big as a house.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

With federal agents off the streets, Portland protesters refocus

Our reporter offers vignettes of the protesters in Portland, Oregon – where they’re from, what they want, and the values and ideals motivating them to continue now that federal agents have been withdrawn.

As federal agents pull back in Portland, protesters say it’s the end of a distracting standoff over the federal use of force – but one that, for some, underscored their sense that they can bring change.

Violence escalated sharply after the Trump administration deployed tactical teams of federal agents to Portland in early July to protect federal property from damage by protesters. Since Oregon officials negotiated a phased withdrawal, however, there has been an easing of tensions and reduction in violence.

With the chaos receded, Saturday’s protest drew a diverse crowd of locals and out-of-towners, young and old, veterans, blue-collar workers, teachers, artists, mothers, and families – with a range of political persuasions from anti-fascists and communists to mainstream Democrats. In addition to demanding an end to systemic racism, they called to shift funds and responsibilities from the police to community services.

Quan Walters, an illustrator with the Portland Street Art Alliance, paints a mural near the courthouse where protesters and federal agents faced off. He’s joined street marches, but prefers to protest through art.

“It’s like chess pieces,” he says. “Everyone has their own position on the game board, and mine happens to be art and imagery.”

With federal agents off the streets, Portland protesters refocus

With federal agents, tear gas, and other crowd-control munitions notably absent from around Mark O. Hatfield U.S. Courthouse in downtown Portland, protesters here are celebrating what they hope is the end of a distracting standoff over the federal use of force.

Several successive nights of peaceful demonstrations drawing thousands of people signal a welcome turning point in the Portland movement and an opportunity to refocus on issues of racial justice and police reform, they say – relieved, but also motivated, by the agents’ pullback.

“The focus was taken away from the real thing, which is supposed to be Black Lives Matter,” says Carolyn Welty-Fick, a fifth-grade teacher from Hood River, Oregon, holding a large sign saying “RESIST” in bold letters under a black fist, as people all around her chant “Black lives!” The contrast on Saturday night was striking, she says. “It’s great. It’s a lot more peaceful. Last week there was a lot more tension in the air,” she says. “We were in full combat gear – helmets and that sort of thing, there was gas coming.”

At the same time, protesters say the aggressive tactics of federal agents without insignia, who injured some people with crowd-control munitions and dragged protesters into unmarked cars, generated widespread outrage and a media spotlight that has energized support for their movement.

“It got people more angry,” says Matt Robbins, a Portland security officer who acts as a medic during the protests. Demonstrations were “dying down,” with just 300 or 400 people a night, but “as soon as the Feds came it was a few thousand. Last weekend we had 11,000 people.”

Furthermore, protesters can now claim the withdrawal of those agents from the Hatfield courthouse as a tangible victory – and a sign that their activism can produce concrete change.

“It’s a small victory,” says Mike, an organizer dressed in black clothes and boots, who like many protesters declined to give his last name to protect his privacy. “That’s proof this works. That’s proof that being out here and occupying space and showing them ‘we are not afraid of your police brutality’ … and we will fight until we get change – works.”

Summer of protest

As Portland’s demonstrations enter their 10th week, protesters say they will continue to press forward. Protests against police brutality erupted in Portland May 29 as unrest swept many U.S. cities after Minneapolis police killed George Floyd. That night, a peaceful vigil by thousands later devolved into what police declared a riot, as some protesters broke windows of a jail and set fires inside. Early that morning, Mayor Ted Wheeler declared a state of emergency.

The following weeks saw a mix of large, peaceful marches and unrest targeting government buildings, with Portland police firing tear gas and other munitions and protesters hurling rocks, bottles, and commercial grade fireworks and setting fires, injuring officers, according to the police.

“As a Black man and a public servant, I have a unique perspective,” Chuck Lovell, chief of the Portland Police Bureau, wrote in an Aug. 3 New York Times op-ed, stressing he is committed to leading police reforms. “This violence is doing nothing to further the Black Lives Matter movement.”

Throughout the protests, some demonstrators have also voiced concern and disagreement over the movement’s tactics, and argued that the original focus on racism and policing have been overshadowed.

Violence escalated sharply after the Trump administration deployed tactical teams of federal agents to Portland in early July in order to protect federal property from damage by protesters. But there has been little violence since Oregon officials negotiated a phased withdrawal of the federal teams beginning last week. Portland police are investigating the stabbing of a victim on Monday, reportedly a female protester attacked in Lownsdale Square.

While waning in other urban areas, the protests have been sustained in Portland – a city of 655,000 that is more than 70% white – fueled by activists with eclectic viewpoints and tactics, but united around the core goals of ending racism and promoting more humane policing.

“Killing Black Americans for no reason has got to stop,” says David Anthony, an iron worker at Western Group, who quit his union job to take part in the Portland protests from Day 1.

Raising awareness among the general population is the first step toward ultimately ending U.S. police brutality, he says, which leads not only to deaths, but to “suppressing Black people, and silencing them.”

Toward that end, Mr. Anthony now spends all day barbecuing donated food to feed the Portland movement. “Right now, it’s about people being aware of what’s going on,” he says, as he hands out free chicken wings to hungry demonstrators at a corner stand with a huge Black Lives Matter sign. “We just barbecue with love and send that out,” he says, welcoming Saturday’s more relaxed atmosphere. “Keeping people fed is ground zero to keeping people calmer.”

Indeed, with the chaos receded, Saturday’s peaceful protest drew a large, racially diverse crowd of locals and out-of-towners, young and old, veterans, blue-collar workers, teachers, artists, mothers, and families – with some school-aged children leading chants. They also included self-identified anti-fascists clad in black and people of many political persuasions, ranging from communists to mainstream Democrats. In addition to demanding an end to systemic racism, they called to shift funds from the Portland Police Bureau to community services, transferring some police work to social workers and mental health care providers.

Many stories, one protest

Still, the protesters who gather nightly across from the courthouse in Portland’s shady Lownsdale Square are loosely organized at best. Activists who occupied a section of Seattle’s Capitol Hill neighborhood called the CHOP in June have recently fanned out to Portland and other cities to offer help.

“They helped us organize a medical supply tent, a propaganda supply tent, and … are helping us get started with a council and assembly,” says Jared, a software developer and Portland protest leader, leaning against a tree trunk with his guitar. “Most of the organization has come from Seattle, and the street fighting has come from Portland,” he says.

Mike, an anti-fascist organizer who arrived in Portland from Seattle six weeks ago, says he helps provide security and “intelligence” to the protesters by monitoring police scanners, flight logs, and license plates, as well as right-wing groups such as the Proud Boys, Three Percenters, and others who have shown up during protests.

Yet mainly the protests are made up of disparate individuals contributing as they see fit to a common cause.

Near the courthouse, Quan Walters, an illustrator with the Portland Street Art Alliance, paints a huge mural of the cartoon character Huey with a raised fist symbolizing empowerment. Mr. Walters says his art is “a testament to where we are in history and where we want to go.” He has joined street marches, but prefers to protest through art. “It’s like chess pieces,” he says. “Everyone has their own position on the game board, and mine happens to be art and imagery.”

Vietnam-era veterans have formed “walls” in solidarity with the protesters, while urging the police and federal agents, generally much younger, to reject orders to use force. “I stepped forward to tell them why I was here,” says Mike Hastie, a member of Veterans for Peace who served with an Army cavalry unit in the Central Highlands of Vietnam. But as he spoke passionately of Vietnam atrocities to a line of federal agents outside the Portland courthouse in late July, one of them pepper-sprayed him in the face, an incident captured on a video that went viral.

“If we end the militarization [of police], we can have a dialogue,” says another Army veteran, Maurice Martin. “Police dogs, overwhelming force, tear gas – they don’t even use that in the real fighting,” he says. “We … sure should not use it in the streets on unarmed civilians.”

One sign the protests will continue is that they bring together newly energized protesters and those for whom racism has been a life-long struggle. Ms. Welty-Fick, the teacher, says she recently took a class on white privilege at her church, and realized she had been a passive “non-racist,” rather than actively “anti-racist,” and needed to speak out for people of color.

Haseena, a recent college graduate who sells Black Lives Matter T-shirts at the protests, says she is gratified to see so many people advocating for Black lives. “Since I was young, I have seen Black people die and be killed over nothing,” she says. “Change is way over past due.”

Interview

Karen Bass on women, politics, and this moment in history

In our exclusive interview with the five-term congresswoman (and possible Joe Biden running mate), Rep. Karen Bass is encouraged by the growing ranks of women in leadership roles, and offers lessons on the power of relationship-building. Part of our special 100th anniversary edition on women winning the right to vote.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

When she was 14, Karen Bass signed her mother up to be a precinct captain in the 1968 presidential campaign, then did all the door-knocking herself. The congresswoman from Los Angeles attributes that motivation to her father – watching the news with him, trying to understand the civil rights movement, civil disobedience, and the brutal attacks on Black people.

While voting in her family was considered “a ritual that was absolutely a must,” she says, neither of her parents wanted her to become involved in politics. It was an age of political violence and assassination, and they feared she would get hurt.

But “I saw all those other people doing it. You know, when you’re young, you’re invincible. I felt it was my obligation.”

Today, Representative Bass is serving her fifth term and heads the Congressional Black Caucus. As someone who has spent 15 years in elected office, Ms. Bass describes political power as “absolutely critical for change to happen.” And the best way to build power, she says, is through relationships and helping others, rather than “walking over other people.”

Karen Bass on women, politics, and this moment in history

When California Rep. Karen Bass was growing up in Los Angeles in the 1950s and ’60s, her father didn’t talk about his earlier life experiences with Jim Crow Texas. It was too traumatic. But through his actions, the mail carrier taught her one way to counter that ugly injustice.

“Voting was a must. That is a ritual that was absolutely a must,” says Representative Bass, who now heads the Congressional Black Caucus. When she became a parent, she regularly took her daughter to the voting booth, and has pictures of the first time her daughter voted.

In an in-depth phone interview from her home district in Los Angeles last month, Ms. Bass shared her thoughts about the centennial of the women’s vote, how Democrats should use their power should they win the presidency, and where African Americans fit in this constellation.

It’s a universe in which she has become a star in her own right, rising above barriers to become the first Black female speaker of the California Assembly (and of any state legislature). She has been mentioned as a possible future speaker of the U.S. House.

In recent weeks, she has become one of the most-talked-about candidates under consideration as a running mate for Joe Biden. Ms. Bass referred all queries about the VP search to Mr. Biden’s campaign. But she answered a question about whether he needs to tap an African American woman, given the mass protests nationwide over racial justice.

“I don’t think it’s right to say he needs to,” she comments. “Do I want him to do that? Of course.”

More broadly, she speaks to the importance of African American women holding top leadership positions in the United States.

“Women who do the work should be given the authority to lead, and I think that’s true across the board for all women,” she says. Black women “have always done the work behind the scenes.”

While Ms. Bass sees the 100th anniversary of the women’s vote as a “very important landmark, a historic day,” she also believes there is a “ways to go” for women in politics. Rwanda has the highest representation of women in the world, notes Ms. Bass – more than 60% in its lower house of parliament. She also chairs the House subcommittee on Africa, global health, and human rights. In the United States, women make up only about a quarter of Congress, and they’re overwhelmingly Democrats such as herself.

Women “are in no way, shape, or form at parity,” she says. On the other hand, “our voting ability and our ability to make a difference in elections has certainly been recognized, which is why everybody courts the women’s vote.”

Exhibit A: the 2018 midterm elections, which flipped the House to Democrats on a blue wave of women voters and candidates. Ms. Bass is particularly excited about the growing prominence of African American women in Congress and in state and local offices – particularly Black women mayors, who are being featured all over cable news.

“I felt it was my obligation”

Ms. Bass got her start in politics at a young age. When she was 14, she signed her mother up to be a precinct captain for Robert Kennedy’s 1968 presidential campaign, then did all the door-knocking herself. She attributes her motivation to her father – watching the news with him, trying to understand the civil rights movement, civil disobedience, and the brutal attacks on Black people.

“My father was very patient in explaining it to me,” she remembers, though neither of her parents ever wanted her to become involved in politics. It was an age of political violence and assassination, and they feared she would get hurt. But “I saw all those other people doing it. You know, when you’re young, you’re invincible. I felt it was my obligation.”

She became a physician assistant and took her passion to the front lines, founding a nonprofit to fight crack cocaine and gang violence in Los Angeles. She was elected to the state Assembly in 2004, becoming speaker just in time for a budget crisis, when she had to work out painful cuts with her fellow lawmakers and Republican Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger. She was elected to the U.S. Congress in 2010.

In looking toward the November elections, she believes Black people will “turn out in big numbers.” The last three and a half years under President Donald Trump have been a strong motivator for Black voters, she says, pointing especially to the “extremely disproportionate rate” of COVID-19 deaths among people of color.

Still, she says, Democrats can’t be complacent about getting out the vote. She expresses deep concern about voter suppression, particularly in the South. In 2016, she says, many voters took it for granted that Hillary Clinton would win.

“She was running against somebody who was so extreme that nobody believed he would win,” she says. “When he announced his candidacy, I was happy because I thought, ‘Well, for sure, we’ll be fine.’ And what a mistake I made.”

Power in relationships

Ms. Bass notes that the U.S. is still behind much of the world in that it has not had a female president.

A record-breaking six women ran for the presidency this primary season, including an African American, but all of them lost. The congresswoman says there’s no single reason, but adds: “I do believe that women candidates are viewed harsher, picked over, and examined under a microscope in a different way.”

She remembers the California press referring to her as a “mother bear” when she was speaker because she spent so much time with members as they wrestled with a fiscal crisis. She saw the term as pejorative, because if she’d been a man, “they would have said I was collaborative and inclusive.”

As someone who has spent 15 years in elected office, Ms. Bass describes political power as “absolutely critical for change to happen.” The best way to build power, she says, is through relationships and helping others, rather than “walking over other people.”

The independent Cook Political Report recently suggested a Democratic “tsunami” may be on the horizon in the fall. If Democrats get a trifecta this November – winning the House, the Senate, and the White House – how should they use their power?

“The number one thing we have to do is heal this nation” – both physically, from COVID-19 and a president “in denial” about the disease, and in every other way. She hopes a President Biden will move quickly to “clean up the wreckage” in the various government agencies, and call back government workers who were “run out by the Trump administration or couldn’t take it anymore.”

She’s also looking for healing on the race front, and is encouraged by polls showing white and Black Americans for the first time holding similar views about police brutality. When it comes to issues affecting marginalized people, “you have to have the outside pushing the inside.”

It also helps to elect more women, she says. On that front, she’s again encouraged. The next generation is going to do “so much better” in part because many programs have been established to help them run for office.

“That’s going to make a huge, huge difference.”

In Israel, coronavirus brings out a new generation of protesters

Our reporter finds an awakening among young Israelis, who have been seen as politically apathetic. Street protests are fueled by a loss of trust and a newfound desire for integrity in leadership. Is this a generational shift?

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

-

By Dina Kraft Correspondent

Israel’s once-lauded handling of the coronavirus pandemic has been marred by a rushed and sloppy reopening. Infection rates have soared. Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu reportedly dismissed expert medical guidance, preferring to make the calls himself.

Now tens of thousands of younger Israelis have been gathering alongside older protesters across the country to denounce the policies and Mr. Netanyahu. In recent years, younger Jewish Israelis were the demographic most visibly absent from demonstrations. Older Israelis called them out as apathetic, seemingly content to put their energies into what felt like a world of opportunities. But in the COVID-19 era that world has vanished, replaced by record unemployment and a growing belief that Mr. Netanyahu has forsaken them and the country.

Merav Ferziger, 24, was bruised the first night police turned on the water cannons in Jerusalem. She was also arrested that night for the first time. “I’m here because I want to create a better future,” she says. “I feel like our leadership is just so rotten and unable to unite us.”

Getting arrested cemented why she wants to be part of this new struggle. “It made me realize what reality we are living in,” she says. “It changed my perspective.”

In Israel, coronavirus brings out a new generation of protesters

It’s a song for another season, one borrowed from the Hanukkah holiday and citing a need to bring light to banish the winter darkness.

But for a new generation of Israelis finding their own political voice as they protest the government’s handling of the coronavirus pandemic this summer, it has become something of an anthem.

Amid the beating of drums and blowing of plastic horns at the epicenter of the protest movement, thousands of young people filling the street facing Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s official residence last Thursday raised their fists and shouted the lyrics.

Their voices reverberated like a roar, even through masks:

“Though the night is cold and dark.

In our soul, there lies a spark.

Each of us, is one small light.

All together, we shine bright.”

For the past month, tens of thousands of Israelis, many in their 20s and 30s, have been gathering alongside older protesters across the country. Their steadily swelling numbers produced a crowd Saturday night in Jerusalem that police estimated to be nearly 17,000 people and some activists to be twice that.

In recent years, these younger Jewish Israelis were the demographic most visibly absent from demonstrations. Fairly or not, older generations called them out as apathetic and seemingly content to put their energies less into politics and more into what felt like a world of opportunities – like post-army international travel and plentiful work in high-tech and creative fields.

But in the COVID-19 era that world has vanished, replaced by record unemployment, what is largely seen as a botched government response to the virus, and a growing belief that Mr. Netanyahu, who has been in power for most of their lives, has forsaken them and the country. He is more occupied, they say, with quashing his ongoing trial for multiple corruption charges, trying to annex the West Bank, and painting them as traitors and agitators.

“I feel the country has lost its way morally. It’s all hatred and division – a divide-and-conquer approach. That’s Bibi [Netanyahu], that’s his role. It’s how he wins,” says Achinoam Cohen, 31, who grew up in a religious, right-wing home. “I feel like he’s betrayed me. ... I feel like my generation has woken up and is talking about change and wanting to be part of decision-making.”

Israel’s policies, once seen as an example of sober, smart handling of the virus, are now a cautionary tale of a rushed and sloppy reopening. Infection rates soared. Mr. Netanyahu reportedly dismissed expert medical guidance, preferring to make the calls himself.

Some moves made him appear out of touch. With almost a million unemployed, the Knesset approved a tax exemption for him worth an estimated $145,000 to cover renovations to his private home. A close political ally crudely dismissed people’s claims they had no food at home. The young, many of whom work as freelancers and are not eligible for some government grants, have been hit disproportionately hard.

A July 12 poll by the Israel Democracy Institute found 29.5% of respondents trust Mr. Netanyahu’s handling of the crisis, down from 57.5% in April and 47% in June.

What has changed: economics

The protesters say they are looking for someone they can trust. One who will not, they say, trample on democracy and threaten their future as part of his bid to remain in power. The protests are motivated by multiple causes but share one goal, to force Mr. Netanyahu out.

“I’m here because our government is corrupt, our prime minister is corrupt,” says Hagar Dotan, 21. “I was aware of what was going on in the country, but not active until now.”

She came to Thursday night’s demonstration with her friend Noa Noy, also 21, who notes, “there are people out there who don’t have enough to eat.”

According to Neta Kligler-Vilenchik, a professor of communications at The Hebrew University of Jerusalem whose research has focused on youth political participation in the digital age, young Israelis are more engaged in politics than some of their peers abroad when it comes to voting rates and political interest and knowledge.

But what has changed in bringing people to the streets, she says, is mostly economics, which has the clearest impact on their lives.

“The energy is partially driven by that anger but also over their concern for the future of the country. They are saying, ‘We have these ideals we care about, and we are now worried about them,’” says Professor Kligler-Vilenchik.

In normal times “it’s easier for the public to ignore what is happening among politicians. It feels like a sphere unrelated to everyday life,” she adds. “But at the moment we cannot remove politics from everyday life.”

Violence against protesters

A rough police response to the protests seems only to have fueled demonstrators’ determination. The use of water cannons to disperse nonviolent protesters and the manhandling of others being arrested has left people bruised and injured.

Mr. Netanyahu has tried to delegitimize the protesters by labeling them anarchists or leftists (a derogatory term for many in right-leaning Israel), while offering only mild condemnations of far-right activists accused of physically attacking, even stabbing, demonstrators in Tel Aviv and elsewhere.

Merav Ferziger, 24, was bruised the first night the police turned on the water cannons in Jerusalem three weeks ago. She was also arrested that night for the first time. Since then she has not left the city; she moved into an encampment of young people at nearby Independence Park. She and her friends there see their role as helping create a spiritual support center for dialogue and connection among the demonstrators.

“I’m here because I want to create a better future. I feel like our leadership is just so rotten and unable to unite us. They prefer to talk about what separates us. I feel like my place in this is to be someone who connects and creates space for other people.”

Getting arrested cemented why she wants to be part of this new struggle, she says.

“It made me realize what reality we are living in,” she says, still surprised nonviolent protest would be met with what some are calling police brutality. “It changed my perspective.”

Where some young Israelis in the past may have felt more of an impetus to rebel by just leaving the country, decamping for cities like New York or Berlin, Ms. Ferziger says her friends want to stake their claim instead: “I feel like we are understanding how much this place is important to us, how much we want to be here and live here and enjoy this place.”

Professor Kligler-Vilenchik says research on political movements and youth show that such moments can shape a generation’s future political identity.

“For young people, finding voice and protesting can have a mark on them ... If over time they feel they have achieved something, to have had their voices heard and have some kind of outcome – it will increase their sense of political efficacy.”

Rumbles from the right

The demonstrations in Jerusalem – a city known for its predominantly religious and right-wing population – are attracting participants from constituencies that are normally more supportive of the prime minister.

Though the majority of the protesters are secular Jews of European descent, the socioeconomic message of the protests has appeal among both working-class Israelis who are a mainstay of Mr. Netanyahu’s Likud party and national religious Jews.

Matan Barak, an 18-year-old graduate of an Orthodox Jewish high school in Jerusalem, participated in one of the protests and says he was bruised after being roughed up by policemen.

“What I liked about Balfour [the demonstrations outside Mr. Netanyahu’s residence] is that there wasn’t one kind of people there. I spoke to [ultra-Orthodox] Haredim there, and I spoke to Arabs there. There were secular and religious participants, right wing and left wing,” says Mr. Barak, who sees the government’s economic response to the pandemic as inconsistent and insensitive.

“If they just cared a bit more, the situation wouldn’t be this bad. Stupid decisions. Bibi puts his own needs before the country.”

Mr. Barak’s father, Mitchell, is a public opinion expert who says Mr. Netanyahu is vulnerable because many of his loyal supporters are susceptible to the economic shock caused by the pandemic.

“It’s not just a leftist thing going on here. Likud voters normally push aside their own interests and look for a strong foreign policy leader who stands up to the world,” says the elder Mr. Barak. “But now they are hurting, and they’ve lost their jobs. These are people who don’t have money for food.”

Correspondent Joshua Mitnick contributed reporting from Tel Aviv.

Editor’s note: As a public service, all our coronavirus coverage is free. No paywall.

Perception Gaps

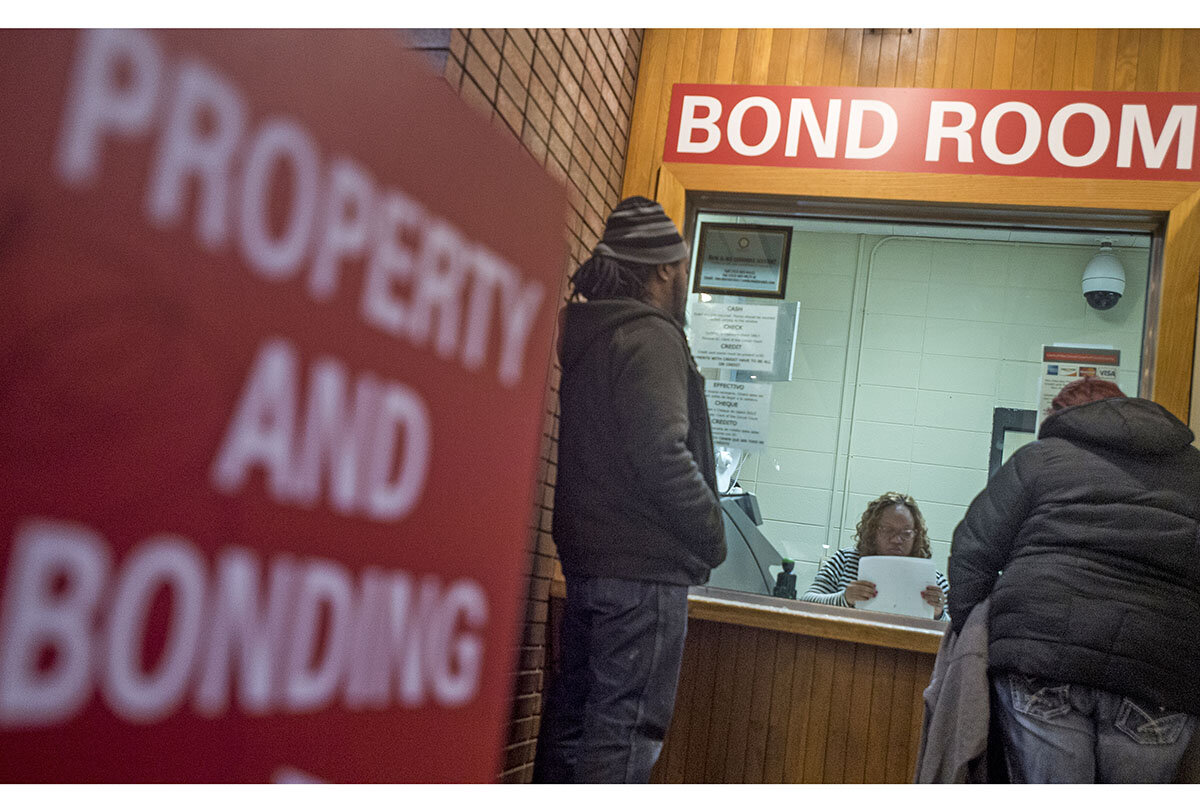

Who’s really inside America’s jails? (audio)

Did you know that most people in jail have not been convicted of a crime? Many Americans are unaware of how the criminal justice system actually works. Our new season of the “Perception Gaps” podcast sheds light on some of these misconceptions.

According to a 2020 report by the Prison Policy Initiative, 74% of people in American jails have not been convicted of a crime. Sometimes this is because they’re considered a flight risk or danger to society, but the majority of individuals in jail are there because they can’t afford bail. And while inside, they’re often given a choice: plead guilty and get released, or stay in jail until a trial is scheduled, and hope they’re proven innocent.

Most people take the plea bargain.

The idea that individuals are innocent until proven guilty is supposed to be at the heart of our criminal justice system. But in reality, it’s not, says Alexandra Natapoff, a professor of law at Harvard University. “We are letting the pressures of the criminal system decide who will sustain a conviction,” she says. “So we are already committed, in some terrible sense, to punishing the innocent.”

In Episode 1 of “Perception Gaps: Locked up,” our reporters explore the history of mass incarceration and the long-reaching effects it has on communities.

Note: This is Episode 1 of Season 2. To listen to the other episodes and sign up for the newsletter, please visit the season landing page.

This audio story was designed to be heard. We strongly encourage you to experience it with your ears, but we understand that is not an option for everybody. For those who are unable to listen, we have provided a transcript of the story here.

America Behind Bars

Embattled TikTok: Behind the dance-duels, a platform for youth activism

Here’s another story about emerging activism. We look at how TikTok went from an apolitical app for teen dance videos to a platform for battling racism and a threat to national security, according to Trump officials.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

-

Noah Robertson Staff writer

TikTok, the Chinese-owned video-sharing network that has taken the world by storm during quarantine, has quickly transformed from a way of sharing 15-second lip-sync clips to a powerful youth political platform in the United States. Across the country, young people have used the app to artificially inflate the expected attendance of Trump rallies and to organize Black Lives Matter demonstrations.

The White House is making threats against the app, out of what it says are concerns that the app’s parent company could censor content or steal users’ sensitive data for the Chinese government. The Trump administration recently threatened to ban the app if its Chinese parent company doesn’t divest ownership to an American firm.

Young activists say their message will find an outlet, with or without a ban.

“TikTok was not the place for activism, but we got creative and turned it into that,” says TikTok user Alyssa Bigbee. “That just shows that that can happen in any space they enter, even if this app was gone.”

Embattled TikTok: Behind the dance-duels, a platform for youth activism

Alyssa Bigbee, an acrobatics instructor in Philadelphia, downloaded TikTok last December to post videos of her students performing. For her – like its millions of other users – the app was something of an internet playground, filled with endless videos offering 15-second fun.

But that would soon change.

During the George Floyd protests at the start of the summer, Ms. Bigbee had noticed countless Americans asking how to be a white ally. She had an answer, so she posted it on TikTok. More than 150,000 people watched it.

“I never thought I would get 10,000 followers from talking about racism,” she says.

This year, millions of people around the world took to social media for entertainment during lockdowns, helping video platform TikTok become one of 2020’s most downloaded apps. In months, it has gone from an apolitical teen utopia to an emerging activist platform and possible security threat – with the Trump administration recently threatening to ban the app if its Chinese parent company doesn’t divest ownership to an American firm.

As its users and owners race to adjust to the White House’s threats, social media experts say TikTok’s dramatic shift is another example of cyberspace colliding with the real world.

“When young people see the organizing that they do online can have an impact on what’s happening offline, then they feel more encouraged to vote and get involved in electoral politics,” says CedarBough Saeji, a visiting assistant professor of East Asian languages and cultures at Indiana University Bloomington. “This is a crucial moment for them to think about the impact of politics on their lives.”

Tuning in, tuning out

The app has begun to change as users like Ms. Bigbee started using it for activism. Ahead of President Donald Trump’s June rally in Tulsa, teens used the app to artificially inflate the expected attendance. Others are confronting white supremacy by using the app to organize demonstrations and communicate about racism.

Yet among social platforms, TikTok seems one of the least likely for political activity. It plays tailored feeds of memes, lip-syncing, dance challenges, and other bite-size diversions – most intended for its young user demographic. Often set to music, the app’s 15-second videos tend to entertain rather than inform.

Owned by Chinese parent company ByteDance, the app also has a reputation for removing controversial content. In late 2019 a teen’s account was suspended after she criticized the Chinese government for its treatment of Uyghurs in Xinjiang province. Last December, TikTok admitted that it had policies suppressing videos of people with disabilities, people with neurodiverse conditions, obese people, and members of the LGBTQ community. (These policies have changed, according to a spokesman.) Many users now say videos with #blacklivesmatter are getting targeted.

Other outspoken users have accused TikTok of “shadowbanning” them – or making their posts invisible to anyone outside their followers.

While TikTok’s activist culture is global, it’s found a special resonance in the U.S. during the George Floyd protests. In the past few months, politically minded young people have taken to the app, using hashtags such as #blacklivesmatter billions of times.

“Young people are really good at – I don’t want to use the word hacking – but using social media in unique and unexpected ways,” says Dhiraj Murthy, a sociologist at the University of Texas at Austin.

Those strategies include intentionally misspelling sensitive words, avoiding certain hashtags, and using symbols to sneak past censors. TikTok users have adapted their activism to the app, developing a distinct etiquette and language.

In the process, TikTok is finding a niche among other activist-oriented media, such as Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube. Its particularly arresting videos help catch the attention of today’s distracted culture, says Professor Saeji. And in a world of unlimited content, catching people’s attention can matter.

Rising voices

Ms. Bigbee, the acrobatics instructor, has seen it matter firsthand. She and a network of “virtual allies” on the app have coordinated posts about Black Lives Matter protests and spread information about the challenges faced by certain ethnic groups, such as Native Americans. Some of those efforts have reached tens of thousands of users, she says.

“I credit TikTok and a mixture of the quarantine for why BLM blew up so wide,” says Ms. Bigbee.

When it comes to raising awareness about issues related to race, the numbers on TikTok often speak for themselves – just ask Anastasia Achiaa.

Late this May, Anastasia, a high school student in Uxbridge, Massachusetts, posted a poem about her experience with stereotypes of Black women. In two months, it’s gotten more than 2 million views, and helped bring Anastasia’s account from relative obscurity to nearly a quarter of a million followers. Since then – even in the face of repeated shadowbans – Anastasia has continued posting on politically relevant issues. For her, TikTok’s adolescent activist culture is a sign that her generation is continuing the tradition of civil rights activists who came before.

“We’re a generation that’s gonna fight,” she says.

Whether it’s sharing problems while dancing to a catchy song; answering questions about race, gender, sexuality, or politics; or describing one’s culture and history, such action can take many forms and reach millions of users worldwide.

TikTok has “allowed a lot of the younger generations to really connect and spread awareness just like wildfire,” says Luana, who has 14,000 followers. Asking to go only by her first name for privacy reasons, Luana uses the app to share Hawaiian culture and history.

“It’s nice to know that my voice is actually being heard and people are starting to understand more about our culture,” she says. “That’s all we want. Even if it’s just one person, I’m happy that I was able to help them.

An “unprecedented move”

But with concerns over potential Chinese interference, TikTok activism may come with particular risks – such as improper data use or misinformation campaigns. India, once the app’s largest user base, instituted a ban in June.

The evidence for these threats is mixed, says Samm Sacks, a cybersecurity fellow at the think tank New America and a senior fellow at Yale Law School’s Paul Tsai China Center. Still, on July 31, President Trump announced he planned to ban the app from the U.S., which he said he could do through emergency powers or an executive order. Mr. Trump later relaxed his threat, saying the deal can go through if TikTok finds a buyer by Sept. 15 – but only if the U.S. government gets a cut.

Even if the app dodges a ban, for Microsoft to purchase the company under pressure from the U.S. government still represents “an unprecedented move in the way that you have state control over internet platforms,” Ms. Sacks says.

Meanwhile, TikTok U.S. General Manager Vanessa Pappas quickly responded to Mr. Trump’s proposed ban. “We’re not planning on going anywhere,” said Ms. Pappas in a minute-long video posted on the app.

But even if TikTok were banned, says Professor Murthy, its users would likely adapt.

“If the political will is there in terms of an activist momentum, it’s going to find steam in another platform if the platform is taken away from them,” he says.

Ms. Bigbee, who says she and other users are already planning to spread their activism to other sites – such as Twitter, Instagram, YouTube, or even creating their own websites – agrees: The movement is bigger than the medium.

“I just hope that everyone knows that this is not the end,” she says. “TikTok was not the place for activism, but we got creative and turned it into that. That just shows that that can happen in any space they enter, even if this app was gone.”

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Fusion’s future gets real in France

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

It’s been called the world’s largest science project. But the biggest part of its story is that it could be a solution to energy and climate problems for centuries to come. The name of this mind-boggling effort is ITER (originally known as the International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor), a megaproject that began to be assembled near Marseille, France, in August.

For decades nuclear fusion has been like a genie who refuses to come out of its bottle and grant a miracle. It entices with a new way of generating electricity, a completely different approach from today’s fission-based nuclear power plants. This project deserves attention because solutions to climate change have been slow in coming.

Bernard Bigot, director-general of ITER, remains confident that his project will produce energy. But the key question is whether it will be “simple and efficient enough that it could be industrialized,” he says.

The billions of dollars and years of work represent a tremendous investment. But the creativity, engineering, and sense of possibilities that fuel it will certainly help humanity find the long-term solution for its energy needs.

Fusion’s future gets real in France

It’s been called the world’s largest science project, the most complex engineering feat in human history. But its enormity and intricacy aren’t even the biggest part of its story. This technology could be a solution to energy and climate problems for centuries to come.

The name of this mind-boggling effort is ITER (originally known as the International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor), a megaproject that began to be assembled near Marseille, France, in August. For decades nuclear fusion has been like a genie who refuses to come out of its bottle and grant a miracle. It entices with a new way of generating electricity, a completely different approach from today’s fission-based nuclear power plants, which rely on splitting atoms. Using tremendous heat and pressure, nuclear fusion joins atoms together. While doing so, in theory at least, it would generate many times more energy than it takes to create the fusion process.

Its fuel would be largely hydrogen gas, available in abundant supply around the world. No country could corner the market on it. And compared with nuclear fission plants, fusion would produce very little in the way of radioactive materials, the tricky disposal of which is one of the great drawbacks of fission reactors.

This project deserves attention because solutions to climate change have been slow in coming. Conventional fossil fuels, including coal, are not being eliminated fast enough and scaling up renewable energy such as wind and sun has been challenging. Turning more to conventional nuclear powerplants brings not only the aforementioned disposal problems but also safety concerns, as highlighted by the disasters at Chernobyl and Fukushima.

Bernard Bigot, director-general of ITER, remains confident that his project will produce energy. But the key question is whether it will be “simple and efficient enough that it could be industrialized,” he says. “The world needs to know if this technology is available or not. Fusion could help deliver the energy supplies of the world for a very long time, maybe forever.”

The huge mechanism under construction requires the application of science and engineering at their most demanding. “Constructing the machine piece by piece will be like assembling a three-dimensional puzzle on an intricate timeline [and] with the precision of a Swiss watch,” Mr. Bigot says.

ITER is the product of an international effort that so far has survived disruption from the pandemic or from political tensions. The partners include the United States, China, India, Russia, South Korea, and members of the European Union.

It follows in the footsteps of other joint scientific endeavors such as the International Space Station (15 nations) and The Human Genome Project (20 institutions in six countries). The genome project, successfully concluded in 2003, was considered the largest collaborative biological project ever undertaken. The ITER effort, says Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi, is “a perfect symbol of the age-old Indian belief ... [that] the world is one family.”

The next checkpoint should arrive in 2025 when the first plasma would be produced in the fusion process. Another decade would be needed to see if the concept works in its entirety and would be commercially viable.

The billions of dollars and years of work represent a tremendous investment. But the creativity, engineering, and sense of possibilities that fuel it will certainly help humanity find the long-term solution for its energy needs.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

What’s constant in uncertain times?

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Beverly Goldsmith

In these days of lockdowns and “safer-at-home” orders around the world, it can seem hard to find a sense of normalcy. But as a woman from Melbourne, Australia, has found, God-given qualities of strength, joy, and peace are a constant in our lives, there for us to feel and express even when it seems life has been turned upside down.

What’s constant in uncertain times?

The city I live in, Melbourne, Australia, recently enacted a second “stay-at-home” citywide lockdown. The mental strain of repeating the experience of living under such circumstances can be difficult to handle. So I’ve been praying to gain a sense of peace and normalcy despite the situation.

As I’ve prayed, I’ve come to the realization that not everything that one might consider part of normal life has changed during this difficult time. There are many heartwarming, natural things that we can still do.

For instance, we can still express love for our families, offer words of appreciation to those staffing the supermarket checkouts, and smile at the delivery person at our door. We can still clap our hands in delight when something brings us joy, dance with the little ones in our household, or enjoy using technology to share comfort and encouragement with family and friends that we can’t meet up with.

The reason that we can still experience and share qualities that gladden our hearts, even in the face of difficulties, is because there is a divine Love that is tenderly embracing us as we go about our daily activities. This Love is something boundlessly good and constant: God. And God’s love is still just as present during a lockdown. This love from our heavenly Father-Mother, God, naturally sustains our well-being. It buoys our spirits and inspires us to realize that it’s not just possible but natural to feel loved, always.

And right now, we are each the expression of that divine lovingkindness, created in God’s spiritual image and likeness to express the qualities that naturally reflect the Divine (see Genesis 1:26, 27). Knowing this spiritual truth about ourselves empowers us to be the buoyant and happy individuals that exemplify how God created us. We can be courteous, considerate, kindly, and caring to others. We can continue to give encouraging support to friends and loved ones in every way possible. We can keep up individual prayer and spiritual practices, and enjoy church fellowship through online services if meeting in person is not allowed.

As I prayed with these ideas one recent morning, my thoughts were uplifted. I found my heart filling with gratitude. I felt so convinced that the goodness of God’s love is right at hand. It hasn’t gone anywhere. It is still present as it always has been in the past, and will be in the future.

This divinely impelled gratitude also led me to treasure many everyday things, including seeing my home as a haven, a place of shelter. Instead of thinking of it as a prison and resenting being told to stay at home, I now cherish where I live as a place to nurture and express God-given qualities.

As those of us around the world in various stages of lockdown patiently stay at home, daily prayer inspires me. It encourages me to remain hopeful instead of being fearful, to steadfastly trust in God’s ever-present care, and to keep a more spiritual perspective of normalcy uppermost in thought, rather than counting the days in striving to reach it. God-given qualities of strength, joy, and peace are always ours to express wherever we are. With divine Love’s help, each of us can successfully find and express that divine normalcy, even in these uncertain times.

Editor’s note: As a public service, all the Monitor’s coronavirus coverage is free, including articles from this column. There’s also a special free section of JSH-Online.com on a healing response to the global pandemic. There is no paywall for any of this coverage.

A message of love

Tragedy in Lebanon

A look ahead

Thanks for joining us. Come back tomorrow. We’re working on a story about how some U.S. playwrights are envisioning a post-pandemic world.