- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 10 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- Election 2020’s fundamental question: ‘What defines America?’

- Understanding polarization

- Pandemic politics? In Jordan, it has leveled the playing field.

- Virginia showdown: What 5th District race says about 2020

- Two families, two babies, and one – thinning – hope for a new Zimbabwe

- The quiet powerhouse fighting racism in one of America’s whitest states

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Election Day (finally) arrives

At long last, it’s here: the week Americans finish casting their votes and then wait – with the world – to learn who will inhabit the Oval Office in January.

Emotions are swirling. Plywood is going up on storefronts. The New York Times remarked on “an urgency never seen before.” Axios news advised that we all “do our part to minimize the drama.” Historian Simon Schama explained what the riotous year 1965 could teach us, and why he “succumbs to optimism.”

For Monitor journalists, it’s been a long stretch of shoe-leather reporting and navigating a breathtaking array of perspectives. And also of recording those lighter moments that happily punctuate the seriousness.

Peter Grier, who’s covered politics for decades, says he realized things were truly different this year when, in Maine, he saw a boat parade – on land. A large pickup was towing a commercial lobster boat flying a very large Trump flag.

Linda Feldmann, another campaign veteran, enjoyed learning a little about Colombian folk music during a Miami car caravan for Joe Biden. Noah Robertson, new to the political game, recalls taking notes on his phone at a press conference when a text popped onto his screen. “I think I’m watching the back of your head on TV,” his proud mother shared.

For Story Hinckley, grocery store parking lots – urban and rural, fancy and modest – tell an important story. The many voters she's buttonholed in them may differ on policies, she notes. But in the end there’s one thing they have in common: “They want good jobs, to feel safe, a promising future for their children.”

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Democracy under strain

Election 2020’s fundamental question: ‘What defines America?’

The rise of toxic partisanship has made political combat in the United States much fiercer, with both parties at risk of losing faith in the fairness of the country's political rules. But tumultuous periods can open the door for national reform efforts, as happened after Watergate.

Both supporters and critics of President Donald Trump agree he’s been a norm-busting president. His supporters often say he was elected in 2016 to shake up the status quo. Complaints about the threat he poses to the existing order are simply liberal pearl-clutching, in this view.

But the past four years have damaged not just political norms, but the underlying values they represent: tolerance of opponents, forbearance in the use of power, belief in the power of voting.

It’s these values that really need defending, say experts on democratic rise and decline. If they decay too much, the parties may think the game of democracy is in fact no longer worth playing, and become locked in a downward spiral of mutually abusive hardball tactics.

The good news is that this is far from foreordained. After all, the ability to change and correct course is fundamental to democracy, says Sheri Berman, a professor of political science at Barnard College.

In the short run, Professor Berman says she’s worried about the 2020 vote and the possibility of a crisis instigated by fraud charges and court intervention. But for the long run she’s more hopeful.

“I’m an optimist about democracies’ ability to shift course and remedy mistakes,” she says.

Election 2020’s fundamental question: ‘What defines America?’

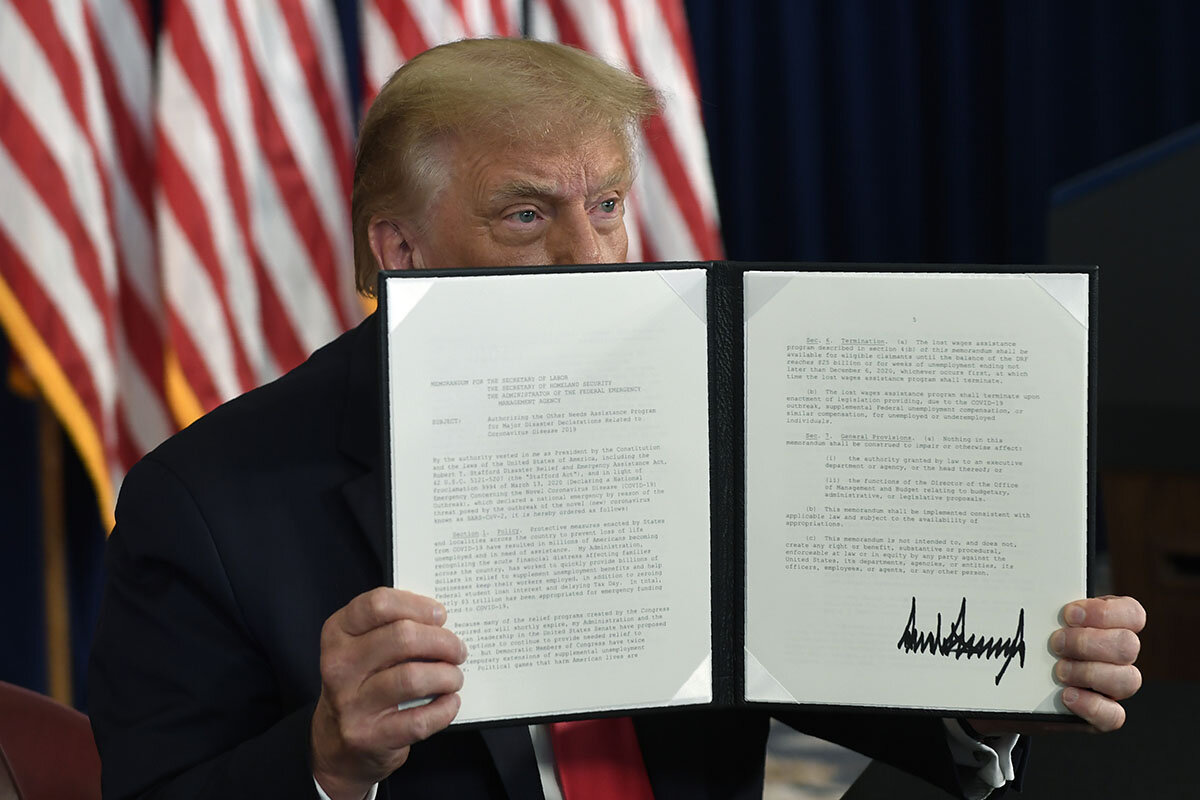

President Donald Trump has spent much of the past four years pushing boundaries and breaking through norms and traditions that have long defined American democracy.

He’s declined to sever ties with his businesses while in office, saying “the president can’t have a conflict of interest.” During a summit with the Japanese prime minister, the president’s Mar-a-Lago club charged the government $3 for Mr. Trump’s own glass of water.

He’s tried to harness the powers of U.S. justice for his own benefit, publicly pushing his attorney general to jail political adversaries such as former President Barack Obama for unsubstantiated “treasonous” actions.

He’s attacked in advance the outcome of the upcoming presidential election, falsely saying mail-in balloting is inherently fraudulent. He tells his supporters that Democrats can win only if voting is “rigged.”

In many ways President Trump may simply be the apotheosis of long-standing strains and problems with the great machinery of democratic governance established by the Constitution in 1788. The rise of toxic, tribal partisanship has made the nation’s political combat much fiercer. Both parties are beginning to regard the other as not just opponents, but perhaps enemies. Both may be beginning to lose faith in the fairness of the rules of the U.S. political system.

But on top of these existing problems, Mr. Trump has piled an “extraordinary rhetorical audacity and recklessness” that has had “severe costs,” in the words of Obama White House counsel Bob Bauer. This may have damaged not just political norms, but the underlying values they represent: tolerance of opponents, forbearance in the use of power, belief in the power of voting.

It’s these values, not norms and traditions per se, that really need defending, say experts on democratic rise and decline. If they decay too much, the parties may think the game of democracy is in fact no longer worth playing, and become locked in a downward spiral of mutually abusive hardball tactics.

The good news is that this is far from foreordained. For instance, Mr. Bauer and co-author Jack Goldsmith, a top Justice Department official under President George W. Bush, in “After Trump: Reconstructing the Presidency,” have compiled a list of more than 50 proposed legislative and executive changes that could plug and patch over holes and faults exposed by the president during the past four years.

Others, including Democrats in Congress, have begun similar efforts. Their point is to have a national reform effort for democracy following Mr. Trump’s exit, whenever that is. The model is the post-Watergate era, when there was at least something of a bipartisan national consensus that things had gone badly wrong and needed to be fixed.

After all, the ability to change and correct course is fundamental to democracy, says Sheri Berman, a professor of political science at Barnard College and author of “Democracy and Dictatorship in Europe: From the Ancien Régime to the Present Day.”

Democratic elections can be break points that push national politics in a transformative direction, as they did in the U.S. following Watergate or the onset of the Great Depression.

In the short run, Professor Berman says she’s worried about the 2020 vote and the possibility of a crisis instigated by fraud charges and court intervention. But for the long run she’s more hopeful.

“I’m an optimist about democracies’ ability to shift course and remedy mistakes,” she says.

How to break a vicious cycle

Not all Americans share that optimism. In fact, many are pessimistic or worried about the state of the nation’s democracy and government, according to polls.

According to recent Pew Research Center figures, 59% of Americans are “not satisfied” with the way democracy is working in the country. By way of contrast, the same figure among Canadian citizens is 33%.

Only 46% of Americans agree that the nation is “run for the benefit of all,” according to Pew. That’s down from 65% who agreed with that statement in 2002. And only a quarter of U.S. citizens believe America’s system of democracy is getting stronger, according to a Democracy Project survey. Sixty-eight percent think democracy is getting weaker.

“Confidence in our governing institutions has been weakening over many years, and key pillars of our democracy, including the rule of law and freedom of the press, are under strain,” concludes a special report of The Democracy Project, a joint venture of Freedom House, the Penn Biden Center, and the George W. Bush Institute at Southern Methodist University.

One way to understand what’s happening to American democracy is to think of it as a game in which both sides want to keep playing for an infinite number of rounds, say experts. It’s important that neither side is ever permanently defeated, or becomes so angry and demoralized that it wants to stop playing.

Two key unwritten democratic norms underlie this system, write Harvard University government professors Steven Levitsky and Daniel Ziblatt in their 2018 book, “How Democracies Die.” The first is mutual toleration, in which each side accepts the other as legitimate. The second is forbearance, in which politicians resist the temptation to use temporary control of political institutions to maximum advantage.

Both have eroded in recent years, says Professor Levitsky in an interview.

“It’s definitely gotten worse,” he says. “It was an especially speedy effect.”

The obvious example for this is the partisan struggle over Supreme Court nominations. The GOP-controlled Senate denied Democratic Supreme Court nominee Merrick Garland a hearing in President Barack Obama’s last year in office, then turned around and pushed through Trump nominee Amy Coney Barrett under similar circumstances.

Republicans, for their part, cite what they perceive to be harsh Democratic treatment of other nominees, including Justice Brett Kavanaugh in 2018 and the failed nomination of Robert Bork in 1987, as partial justification for their tough tactics. They also point out that the party that controls the Senate can do what it likes.

In response, some Democrats are now calling for an expansion of the Supreme Court if Joe Biden is elected president and the party wins the Senate, along with a possible end to the Senate filibuster.

“There is much greater pressure in at least a wing of the Democratic Party for hardball moves. Even at the rank and file level,” says Professor Levitsky.

He and co-author Professor Ziblatt support some sort of Democratic response to what they characterize as minority rule in the United States, in which the party that wins the popular vote can still lose in the Electoral College. That response might include ending the Senate filibuster, and extending statehood to Puerto Rico and Washington, D.C.

Other experts worry that this sort of thing in other countries has tended to further ignite a tit-for-tat cycle. If a Democratic Party in control of Congress and the White House names two new states, what would happen the next time the GOP is in the same position? Division of states to add yet more senators? It’s easy for parties to take short-term gains, while believing against evidence that they’ll be able to temper the long-term cost when the other party is in power.

“Once you get into this sort of vicious cycle, it is very hard to break,” says Professor Berman of Barnard College.

“This is not a recipe for democratic health”

President Trump’s supporters often say he was elected in 2016 to shake up the status quo, and that breaking norms and old traditions is just what they expected him to do. Complaints about the threat he poses to the existing order is simply liberal pearl-clutching, in this view.

In addition, he has just taken advantage of existing trends, they say. He’s built and expanded on things that were already happening.

But that’s something that truly authoritarian leaders often do, says Valerie Jane Bunce, a professor of government at Cornell University who specializes in the rise and fall of democracies. Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban and others have exploited existing institutional weaknesses to carry out anti-democratic agendas, Professor Bunce says.

“Trump is unique in how far he has gone in this direction and how easy it was for him to do so as a result of both political polarization ... and the decline of U.S. political institutions,” she says in an email.

The partisan polarization of America long predates the Trump era. For decades, American social identity has gradually been aligning with political identity, producing parties that are not only ideologically different – liberal versus conservative – but racially, educationally, and religiously distinct as well. The result: an increasingly powerful “my team” effect, to the point where members of both parties hold highly unfavorable views of their opponents.

Polarization is what protected President Trump after he was impeached for improperly pressuring the president of Ukraine to open an investigation into former Vice President Biden and his son Hunter Biden. The trial vote in the Senate was a virtually straight party affair, with all but one Republican, Sen. Mitt Romney of Utah, voting to acquit.

Polarization is what’s kept Senate Republicans in general lockstep behind President Trump since, given his hold on their party’s base and lawmakers’ fear of being challenged in a primary by a more pro-Trump supporter, or belittled by a Trump tweet for being insufficiently supportive.

Polarization will also likely exist long after President Trump has left the stage, says Jeffrey Stonecash, professor emeritus of political science at Syracuse University. To understand it, we need to examine the ideas and values that drive it – which groups embrace some ideas and not others, and how those groups politically align, he argues.

At the heart of all this is a question, Professor Stonecash says: What defines America?

“A fundamental argument coming out of the Democratic Party is that things are not fair,” he says. “You have a Republican Party making a moral argument that’s fundamentally different ... that it’s not about ‘fairness,’ it’s about who’s more deserving.”

As for the decline of U.S. political institutions, President Trump has benefited from the gridlock that has overtaken Congress in recent decades, weakening its ability to counter the executive branch. The presidency, meanwhile, has been correspondingly gaining in power. Presidents George W. Bush and Obama both made aggressive moves with executive orders, after all; both ignored Congress on war powers when it suited them. In that sense, with executive orders that have mandated big changes in U.S. immigration policy, the raiding of Pentagon accounts to fund the southern border wall, and the assassination of a leader of the Iranian Revolutionary Guard, President Trump is simply taking precedent and dialing it up several notches.

“This is not a recipe for democratic health,” says Professor Berman.

Recipe for Washington reform?

If President Trump wins the 2020 election, his norm-breaking and stretching of Oval Office powers – things his opponents often label abuse of power – will undoubtedly continue. He will likely see reelection as voter acceptance of his behavior.

It might even accelerate, given that the president has over the past four years steadily weeded out top officials who try to block some of his efforts. For instance, Attorney General Barr has so far ignored Mr. Trump’s public insistence that he arrest former President Obama, Hillary Clinton, and Joe Biden on unsubstantiated charges that they have launched a “coup.” Could the president possibly find a new attorney general who would carry out such incendiary action?

Mr. Trump to this point in his presidency has not actually acted in an unfettered manner, says Harvard Law School professor Jack Goldsmith. He has faced some pushback from government institutions. He was impeached by the House earlier this year, after all.

Courts have blocked or forced major changes to his travel ban and other administration efforts. Aides have sat on or refused requests they deemed controversial or illegal, such as Mr. Trump’s insistence in 2017 that special counsel Robert Mueller be fired.

Thus at least some of the guardrails of American democracy remain in place.

“Norms can work,” says Professor Goldsmith.

If Mr. Biden is elected president and Democrats win a majority in both the Senate and House, however, Washington is likely to see a major effort to produce a package of democracy reforms intended to repair and rebuild the norms and traditions shattered in recent years.

The analogy may be to the 1970s, when following the turmoil of Vietnam and the Nixon era, Congress reformed the civil service and presidential record-keeping and transparency while passing major laws such as the War Powers Act, the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act, the Privacy Act, the Inspector General Act, and other open government bills.

“If Biden wins, I suspect there will be an attempt to engage in reforms kind of like after Watergate,” says Professor Berman of Barnard College.

House Democrats have already begun drawing up a list of reforms, which includes among other things a mechanism to enforce the Constitutional ban on presidents accepting things of value from foreign nations, reassertion of congressional control of the power of the purse, a requirement that political campaigns report suspicious foreign contacts to the FBI, and limits on presidential emergency powers.

Mr. Bauer and Professor Goldsmith, who served a Democratic and a Republican administration respectively, have fleshed out an extensive blueprint of possible overhauls in their “After Trump” book.

“The proposals are based on the assumption that there may be more Trumps in the future,” says Professor Goldsmith. “The goal is to put constraints in place.”

Addressing financial conflicts of interest should be one reform priority, they urge. They recommend writing in law a requirement that presidents and vice presidents and candidates for those offices disclose their annual tax returns. They also urge that Congress bar presidents from active or supervisory roles in the oversight of any business, even if such a role is informal.

Ensuring Justice Department independence is another priority, the pair say. That means amending internal department rules and guidance to emphasize ethical principles insulating law enforcement decisions from improper partisan political considerations.

They would also prohibit presidents from pardoning themselves and change bribery laws to make clear that it is illegal to dangle pardons to bribe witnesses or obstruct justice.

The point is not to cut down the presidency. America needs a powerful chief executive to ensure effective national governing. The point is to ensure that voters retain confidence that presidents – of either party – can’t go too far.

“You can’t stop future Trumps if you think this is only behavior a Republican president would engage in,” says Professor Goldsmith.

Graphic

Understanding polarization

What – or who – can best tell the story of America’s political polarization? If you’re pointing to Washington’s halls of power, you might want to reconsider.

If you were to reduce the past 30 years of American elections down to a single word, it might well be one you’d never think of: “sorting.” The dominant trend in American politics during that time has been polarization, but that word alone doesn’t capture what’s going on. America is not just becoming more liberal and more conservative. It is sorting into two distinct identities based on partisan ideology.

Consider the 1960s, for instance. America went through dramatic social change, but Congress was still able to cooperate and pass legislation. Why? One big reason is that, back then, there were liberal Republicans and conservative Democrats. Both tended to pull their parties toward the center, which is where legislation and compromise was born.

Today, that diversity within parties is gone. American voters are increasingly defining themselves by their partisan identity, which now often correlates with everything from religion to race to age to education. For example, the Democratic Party is becoming steadily less religious, more racially diverse, younger, and better educated. The Republican Party is moving in precisely the opposite direction. The result is two clear camps, one liberal and one conservative, with almost nothing in between. The trend is even more pronounced among the most politically active voters, adding to the growing pull toward the extremes.

That puts a different light on these elections, where a record 94 million Americans have already voted. How can an increasingly “sorted” republic find the common ground to govern? Voters will get their say tomorrow. – Mark Sappenfield, editor

Pew Research Center, Voteview.com, Common Ground Committee

Pandemic politics? In Jordan, it has leveled the playing field.

Few Americans would say the coronavirus has benefited this election season. But in Jordan, pandemic restrictions have played the role of equalizer, opening the door to new candidates, and perhaps more democracy.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

As Jordanians prepare to vote for Parliament next week, social restrictions imposed by the pandemic are acting as a catalyst, shaking up an electoral culture built on blood ties, vote-buying, and tribal peer pressure.

In the past, wealthy tribal sheikhs and businessmen would erect tents, hosting hundreds of relatives, neighbors, and undecided voters for banquets that offered sweets, coffee, and promises of jobs.

But the pandemic has pushed Jordanian politics and politicking out of the tents and into the world of online human engagement.

“I am Googling candidates’ [backgrounds and qualifications] before the Facebook rally starts,” says Khaled Saud, a community organizer, as he squints at his smartphone. “Times change, and so must we.”

More broadly, the restrictions are an equalizer, allowing candidates with new platforms but fewer resources to enter the fray. A record 364 female candidates are running, up 44% from 2016, as are 30% more candidates under the age of 40.

“Unlike the rest of the world, elections in Jordan were a social event rather than political,” says Jehad al Momani, spokesman for Jordan’s Independent Electoral Commission. “Now with the socializing taken away, candidates are faced with the fact that you have to have a political program, too.”

Pandemic politics? In Jordan, it has leveled the playing field.

Lamb feasts, mass gatherings, concerts, and cash. Elections in Jordan were long synonymous with extravagance and socializing: heavy on cholesterol, light on politics.

Yet with the COVID-19 pandemic raging throughout the country, this November’s parliamentary elections are looking very different for Jordanian voters like Khaled Saud who are long accustomed to being wooed in person.

In elections past, wealthy tribal sheikhs and businessmen would erect tents and, in a festival-like atmosphere, host hundreds of relatives, neighbors, and undecided voters for nightly banquets, including sweets, coffee, and promises of jobs – even cash.

But more than ever before, the pandemic has pushed Jordanian politics and politicking out of the tents and into the world of online human engagement.

“I am Googling candidates’ [backgrounds and qualifications] before the Facebook rally starts,” says Mr. Saud, a community organizer, as he squints at his smartphone in Rashidiya, in southern Jordan. “Times change, and so must we.”

The pandemic has posed challenges for campaigning and voting in an established democracy like the United States.

But in Jordan, the social restrictions are acting as a catalyst, shaking up an electoral culture built on blood ties, vote-buying, and tribal peer pressure that put clan above personal choice at the ballot box.

More broadly, the restrictions are becoming a great equalizer, allowing candidates with fewer financial resources and new political platforms, including women and young people, to enter the fray.

It is a fundamental shift that experts say is on a par with scrapping the Electoral College in the U.S.

“Unlike the rest of the world, elections in Jordan were a social event rather than political,” says Jehad al Momani, spokesman for Jordan’s Independent Electoral Commission. “Now with the socializing taken away, candidates are faced with the fact that you have to have a political program, too.”

Politics made affordable

Tribes and businessmen have long dominated Jordan’s Parliament, the kingdom’s lawmaking body, overwhelming purely political groups that have splintered into 48 mostly ineffective parties in a country of 6.5 million citizens.

Outside Amman, large tribes would agree on a candidate, expecting their followers to fall in line; smaller tribes were promised “benefits.” Candidates barely spoke a word. It was more of a coronation than a campaign.

But this year Jordan’s government has imposed strict measures for the elections Nov. 10, banning gatherings of more than 20 people, imposing weekend lockdowns and nighttime curfews, and making tent campaigning all but impossible. A five-day lockdown is set for Nov. 11.

The ban on social gatherings has also made competing in Jordanian elections affordable and, candidates say, accessible.

The average campaign once cost tens of thousands of dollars; now all that is needed is the $700 registration fee, leveling the playing field for women and youth candidates who would otherwise be unable to compete with deep-pocketed sheikhs and businessmen.

This has led to a record 364 women candidates, up 44% from 2016, and a 30% rise in candidates under the age of 40.

Samiha Sarayreh, a former school principal in Karak, in southern Jordan, is one of the dozens of women running for Parliament for the first time.

She uses Facebook, Zoom, and WhatsApp to reach her base of women and former colleagues – showcasing her trademark brutal honesty and commonsense outrage, and addressing issues such as distance learning, unemployment, and corruption.

“Give the women a chance”

“I decided to run this year because I have the chance to reach voters directly, and they can decide who will speak for them, not what their tribe says or who has the most money,” Mrs. Sarayreh says as she meets with three masked voters in her home in Karak. She says she is tapping into growing frustration with male-dominated parliaments and a broader push by King Abdullah to have more women in leadership positions.

“There is a sense that we have tried men and have gotten the same disappointing results. Why not give the women a chance?” she says.

“The low cost of elections has created an opening for women and young people this year,” says Wafa Yousif Tarawneh, who this year formed Jordan’s first all-women electoral list, Nishmiyat Haya, and is competing against relatives, much to the outrage of her tribe. She has inspired three additional all-women electoral lists across the country.

“In a time of pandemic, people are looking for policies and solutions, and there is a sense that women are more trustworthy and able to provide that,” Ms. Tarawneh says.

While long given a free pass, tribes and businessmen have been put on their heels by the crisis, with citizens demanding solutions to the health crisis, education, and job creation in a country that has seen 23% nationwide unemployment and jobless rates reach 50% outside the capital.

“People are demanding solutions,” says Hussein Mahadin, dean of the school of sociology at the University of Mutah, who served as a moderator for candidate debates. “The tribe’s monopoly on politics and society is being broken, and women and independents are finally breaking through.”

With social pressures defanged by social distancing, citizens have felt freer to register and run in the elections without the green light from their elders.

In Karak, Jordan’s political heartland, tribes that once strategically fielded one or two candidates suddenly have eight or more members running for Parliament, all running on different platforms but splitting the familial vote.

The main road leading to the city and through outlying villages is plastered with posters of different faces with the same family name, one posted on top of the other as if in competition.

“Tribes are being divided; I have my cousin, my uncle, and brother-in-law running. Which one am I supposed to choose?” says Khaled, an English teacher who long voted the tribal consensus.

“This may be my one chance to make a free individual choice, because it is impossible to satisfy a divided tribe.”

With the field divided, and unable to count on their generosity or peer pressure to secure votes, tribesmen and businessmen are being forced to campaign virtually and compete for undecided voters and persons they have never met.

“Before, a candidate would only address people they knew or were related to, so their speech was limited to the issues facing their relatives and village, if they ever spoke at all,” says Mr. Mahadin, the sociologist.

“Now candidates are forced to go beyond their tribe; they have to address a larger segment of society. They have to focus on broader, inclusive social issues facing citizens across the country.”

Platforms and issues

It’s easier said than done. Facebook Live and Zoom rallies by uncharismatic candidates used to a “coronation” have struggled, sputtered, and are panned on social media.

Money is still filtering into Jordan’s elections; flush candidates are spending tens of thousands of dollars on Facebook advertising. More creative candidates have tried to get around strict election laws by offering weekend getaways at four-star beachside hotels at rock-bottom prices for voters chafing at weekend lockdowns.

Yet again, COVID-19 is proving to be the great equalizer.

The virus has ravaged many electoral lists, forcing candidates off the campaign trail and even into the hospital in the election’s final days. One positive test can doom an entire list built on tribal name recognition.

“People are learning the hard way: If you don’t have a political platform and your candidate gets sick, you’re stuck,” says Badi Al Rafiya, campaign manager for the Islamist-leaning Islah coalition, which has had several candidates contract the coronavirus.

“If you focus on issues and not names and personalities, you can still find ways to succeed without face-to-face campaigning. A person can get ill, but the platform continues to resonate.”

These changes are expected to continue long after COVID-19 subsides; multiple women’s coalitions are set to form Jordan’s first all-women political parties, and debates via social media are now the norm.

But political veterans say there will always be room for a little glad-handing in Jordan’s elections.

“Facebook debates and Zoom campaigning may be the future, but as even America shows,” Mr. Rafiya says, “nothing beats a rally.”

Virginia showdown: What 5th District race says about 2020

Are all politics truly local? We visited Virginia’s once reliably Republican 5th District, where the race is testing the limits of that old adage.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

In 18 of the last 20 years, Virginia’s 5th Congressional District has elected a Republican representative. In 2016, it voted for President Donald Trump by 11 percentage points.

This year, the congressional race here is rated one of the most competitive in the country.

Bob Good, the Republican candidate, is a former county official and fundraiser at Liberty University who describes himself as a “bright-red biblical conservative.” In the primary he defeated a one-term GOP incumbent criticized for officiating at a same-sex wedding.

The Democrat, Cameron Webb, is a physician and director of health policy and equity at the University of Virginia’s School of Medicine. He has styled his candidacy as one of unity and healing, and often promises a return to bipartisanship.

Whether Democrats can expand their majority in the U.S. House Tuesday could well depend on races like this one, and whether Republicans vote the whole party ballot.

Says Quentin Kidd, an expert on Virginia politics at Christopher Newport University: “The idea that we’re talking about a district like the 5th as potentially shifting from ‘R’ to ‘D,’ I think gives you a sense of how widespread the reaction to Trump has penetrated.”

Virginia showdown: What 5th District race says about 2020

Like many residents of Main Street in Sperryville, Virginia, Kevin Reid prefers to let his lawn do the talking.

Among Halloween inflatables, a “Blue Lives Matter” flag flown on his truck, and wood saws buzzing through a home renovation, Mr. Reid displays three large signs: Trump 2020, Daniel Gade for Senate, and Bob Good for Congress.

All three are Republicans, and all three will soon receive Mr. Reid’s vote – even if as regards Mr. Good, who defeated the incumbent in the primary, Mr. Reid doesn’t know much about them.

“I’m not going to pretend like I know everything about Bob Good,” says Mr. Reid, a contractor, lifelong conservative, and 30-year Sperryville resident. Republicans, he says, support traditional American values and unity. And to him, “it just seems like you almost can’t really vote [other than along the] party line.”

Mr. Good’s fate Tuesday may depend on other voters in this once reliably Republican district feeling the same way – in an election that paradoxically features both hyperpartisanship and GOP concerns about the strength of President Donald Trump’s coattails.

After Democrats swept to control of the U.S. House in 2018, this November’s electoral tides may bring yet another “blue wave.” Almost certain to retain their House majority, the question now is whether Democrats can further expand their margin – and areas like Sperryville may hold part of the answer.

Cradled in the Blue Ridge Mountains, the rural town is part of Virginia’s 5th Congressional District, a vertical slice of state larger than New Jersey. In 18 of the past 20 years, the 5th has elected a Republican representative. In 2016, it voted for Mr. Trump by 11 percentage points.

A year later, one of the district’s largest cities, Charlottesville, was the scene of the deadly Unite the Right Rally, which saw violent clashes between white supremacist groups and counterprotesters. Mr. Trump’s reaction to the competing demonstrations and the killing of a counterprotester created a defining early controversy for his presidency, which former Vice President Joe Biden later said was key to his decision to run.

The district’s congressional race is widely considered a toss-up. FiveThirtyEight’s election forecast rates it one of the most competitive contests in the country. Mr. Good, a former Campbell County supervisor with ties to Liberty University, faces a spirited challenge from Democrat Cameron Webb, a physician and director of health policy and equity at the University of Virginia’s School of Medicine.

Some of the uncertainty can be chalked up to local quirks, including the unusual ousting of the incumbent. But the awkward ballet of national and local politics is also on display here. Though the president’s coattails appear flimsy this year, Democrats may need split-ticket voting to flip the seat. But in a partisan era dominated by the race for the White House, is it possible to separate the top and bottom of the ballot?

“I’ve always loved [former House Speaker] Tip O’Neill’s adage ‘All politics is local,’” says Quentin Kidd, an expert on Virginia politics at Christopher Newport University in Newport News, Virginia. “But the Trump era has challenged Tip O’Neill and his wisdom more than it’s ever been challenged.”

Convention chaos

And in a catchall district like the 5th, even local politics are complicated.

Sprawling from the North Carolina border to the Washington suburbs, the district contains multitudes – from liberal students in Charlottesville to conservative farmers in Lynchburg. While demographic change in other parts of the state have reshaped Virginia politics, much of the 5th’s electorate has remained relatively stable. Its long stretches of rural, Southside Virginia resemble the state’s dominant conservative past.

Still, the 5th’s competitiveness is a sign of the times for Virginia Republicans, who haven’t won a statewide race in more than a decade and hold just four of the state’s 13 seats in Congress.

It’s also a product of intraparty conflict. After receiving criticism from local Republicans for officiating at a same-sex wedding, GOP Rep. Denver Riggleman narrowly lost his party’s nomination to Mr. Good in a bitter and chaotic drive-in convention this summer. The one-term incumbent, who had been endorsed by Mr. Trump, has since chosen not to endorse or meet with Mr. Good. He hasn’t even conceded the primary.

“A lot of this race has been driven by the Republicans shooting themselves in the foot,” says Miles Coleman, associate editor of Sabato’s Crystal Ball, a nonpartisan politics newsletter published by the University of Virginia.

Mr. Good’s nomination, says Professor Kidd, continues a long-term trend of Virginia Republicans selecting candidates to the right of the electorate. Mr. Good, a former athletics fundraiser at Liberty University and self-described “bright-red biblical conservative,” seems ordered from the same menu.

“The idea that Republicans would go back to that kind of candidate suggests to me that the Republican Party itself is still fighting over what kind of party it’s going to be in Virginia,” says Professor Kidd.

National patterns

For his part, Dr. Webb cruised through the Democratic primary and has since styled his candidacy as one of unity and healing. While touring the 5th District, he often promises a return to bipartisanship, referencing his work as a doctor and as a White House fellow under both the Obama and Trump administrations.

His campaign has attracted national attention, helping him outraise Mr. Good by more than 3-to-1 in the third quarter.

In response, Mr. Good has accused his opponent of being something of a closeted socialist. In September, his campaign ran TV ads blurring images of Dr. Webb, who is Black, into scenes of urban unrest from the summer. Decried by some as racist, the ads also attempted to tie his rival to issues like defunding the police, “Medicare for All,” and the Green New Deal. Dr. Webb retorts that he does not support these programs.

Sound familiar?

Under the long shadow of partisan politics, even a district-level race like this can seem like a referendum on the top of the ticket.

Yet in an interview with the Monitor, Dr. Webb says he wants voters to think local, saying he has little stake in the race for the White House and is prepared to vote across party lines if he thinks it will help the district.

“I spend all of my time communicating about local issues,” he says. “All politics is local to me in this race.”

By contrast, Mr. Good speaks to the race’s national implications. A vote for him, he says, is a vote to advance the Trump administration’s agenda, or to oppose that of a potential President Biden.

“The 5th District race here is a federal race,” he tells the Monitor. “We are sending a representative to Washington to vote on national policy.”

Keeping it local

But if focusing on Mr. Trump giveth, it also taketh away.

As the president attempts to make up ground in the polls, local allies like Mr. Good are running on frayed coattails.

“The idea that we’re talking about a district like the 5th as potentially shifting from ‘R’ to ‘D,’ I think gives you a sense of how widely the reaction to Trump has penetrated,” says Professor Kidd.

Still, many 5th District Republicans say they aren’t worried about broader trends.

“The national environment will not be the ones casting their ballots in the 5th District,” says Melvin Adams, chair of the 5th Congressional District Republican Committee. “It will be 5th District voters.” And 5th District voters want someone who will reliably vote with the president, he says.

Mr. Adams’ counterpart, Suzanne Long, has different concerns. The Democratic Committee chair says her voters value Dr. Webb’s acumen on local issues and his medical expertise, particularly as COVID-19 cases and hospitalizations surge nationwide.

She also says locals want a candidate who listens. Dr. Webb’s campaign, which has included visits to almost every locale in the district, including Sperryville, gives her hope.

A few weeks ago, less than a mile from Mr. Reid’s house on Main Street, Dr. Webb stopped into Happy Camper, an outdoor equipment store owned by Robert Archer, a six-year resident.

Mr. Archer says he appreciated the visit, the conversation, and the few pictures they took together. He plans to vote for Dr. Webb, and hopes politics can be more collegial.

It would take a different kind of politician to bring that change, he says. But then again, a normal kind of politician wouldn’t have stopped by his small-town store.

“It would be nice,” he says “if we could see politics return to service instead of power.”

Two families, two babies, and one – thinning – hope for a new Zimbabwe

These Zimbabweans felt a surge of hope in 2017 as the birth of new family members coincided with the resignation of a hard-line president. We checked in recently to see how things look now.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

-

By Tendai Marima Correspondent

Aleeya Simbi and Meryl Mutsakani were both born on the same day in November 2017, the day that Zimbabwe finally cast off its longtime leader Robert Mugabe. His downfall raised hopes of political and economic renewal under his successor, President Emmerson Mnangagwa.

Today, the toddlers’ families are struggling to stay afloat amid the pandemic, their livelihoods upended by COVID-19 controls and an economic crash. In July, demonstrations broke out over corruption, leading to a crackdown by authorities that critics compare to Mr. Mugabe’s rule.

For Angela Simbi, whose daughter-in-law gave birth to Aleeya three years ago, the family’s economic struggles aren’t her only problem. In October, the city ordered her to demolish the rooms that they had added to their brick house to accommodate their growing family. She’s unsure how she can fight the order. “This house is mine, I have all the papers, but now they want to break it down. Where am I supposed to go?” she asks.

It’s another reminder of how precarious life can be in Zimbabwe – and how far it seems to be from delivering on the promises of 2017, when the ousting of Mr. Mugabe drew worldwide attention.

Two families, two babies, and one – thinning – hope for a new Zimbabwe

Angela Simbi squinted to read the crumpled piece of paper delivered to her by the city council in early October. Part of her family’s brick home in the suburb of Mbare was an illegal structure, the letter explained, and the family must demolish the extra rooms they’d added.

If they didn’t, the notice warned, the government would come do it for them.

Dread welled in her chest. This house had been in Ms. Simbi’s family since the 1970s, when the white minority government built a settlement of three-room houses for Black workers on the southern edge of the capital, and she and her husband had moved in.

It was the house where she’d raised her children, and where those same children had begun to raise theirs.

In April 1980, she’d walked out the front door and down the road to Rufaro Stadium to see a bookish former liberation fighter named Robert Mugabe take his oath of office as the first prime minister of an independent Zimbabwe. That night, as crowds waved the new country’s new flag, Bob Marley crooned about a Zimbabwe where “every man got a right to decide his own destiny.”

And 37 years later, on a brittle summer day in November 2017, Angela’s daughter-in-law Progress Garakara had woken up inside the same house and felt the first jolts of labor pains. By then, Mr. Mugabe had been Zimbabwe’s head of state longer than Progress had been alive. He’d become an oppressive nonagenarian who bore little resemblance to the guerrilla fighter who’d danced to Bob Marley.

But as Progress walked out of the Simbis’ house in Mbare, shuffling toward the public maternity hospital a mile away, Mr. Mugabe was, improbably, on his way out. Later that day, as she cradled her newborn daughter Aleeya, he announced his resignation.

In their little house in Mbare, the Simbis broke into celebration – for Aleeya and for the new country she’d been born into.

But now, as Angela clutched the demolition notice, she and Progress could barely remember the hope they’d felt that day. Zimbabwe was once again in crisis: its economy in free fall from mismanagement and a global pandemic, its politics every bit as repressive as under Mr. Mugabe’s watch.

“If God really kept a secret, it was of what was to come after Mugabe was gone,” says Progress, whom the Monitor first met in November 2017, a week after Aleeya was born. “We were so happy the day he stepped down and we thought life would be better.”

Instead, a pandemic had pushed an already crumbling economy to a breaking point, and pushed Zimbabweans fed up with its unkept promises into a new wave of protests. There was little sign of when, or how, things might get better.

“Most untarnished promise”

On the eastern flank of the city, in a house wedged between bulging boulders and small hills of tan clay soil in the suburb of Epworth, Joseph and Moreblessing Mutsakani also struggled to make sense of their country’s slide. Their daughter Meryl had been born the same day as Aleeya, in the same jolt of optimism and possibility.

“Welcome to all the Zimbabwean children born on this day,” Zimbabwean novelist NoViolet Bulawayo had written on Facebook hours after Mr. Mugabe resigned. “You’re our most precious, most untarnished promise, may you never see what we’ve seen, may you know, finally, a Great Zimbabwe.”

When they looked at Meryl, who was growing like a weed, tall and sturdy, with a babbling monologue that trailed constantly across their house, the Mutsakanis could still feel the echoes of that promise. But it was growing faint.

Even before the pandemic, the couple struggled each month to cobble together the $360 needed to send their four older children to school, buy groceries, and pay rent.

“We live in a very poor community where there are many things that can spoil a child’s future,” Joseph says, and he and his wife were determined not to let their children’s school fees go unpaid.

Between Joseph’s odd jobs in construction and Moreblessing’s work as a tailor, they usually had just enough to hold things together.

Then on March 30, 10 days after Zimbabwe confirmed its first case of COVID-19, the country went into a rigid lockdown. President Emmerson Mnangagwa, Mr. Mugabe’s former deputy, ordered all nonessential workers to stay home for 21 days; soldiers and police manned checkpoints into city centers to enforce the law. From March to July, they arrested tens of thousands for violating restrictions.

Overnight, the Mutsakanis’ income shriveled. Suddenly, no one was buying new clothes. “People just have no money for [it],” Moreblessing explains. Construction work slowed to a trickle.

Subsidized cornmeal for sale

In Mbare, the Simbis also watched their livelihoods dissolve.

Progress had once made her living selling used clothing brought across the border from South Africa, as did many Zimbabweans. But with the lockdown, borders had closed.

The family’s savings began to dwindle. Soon, so did the stores of food in their house.

As prices of staples surged, the family got wind of some promising news: The government was selling subsidized cornmeal – a Zimbabwean staple – at certain grocery stores.

So at 10 p.m. one night in April, Alfred and Progress escorted Angela to a nearby supermarket, where a line was already beginning to form. Angela should wait, the family reasoned, since older adults were being given priorities in the overnight queue.

But when the staff unlocked the doors the next morning, the crowd surged forward, pushing aside the older people at the front, including Angela.

The desperation shocked her. In normal times, respect for age meant something. But not in a country on an empty stomach.

Angela limped away from the commotion bruised and empty-handed. She didn’t dare return. Instead, the Simbis scraped up the money they had earned selling small sachets of milk and bottles of frozen water, and bought a sack of nonsubsidized maize meal.

All around them, Mbare had become a kind of small-scale market. Along the Simbis’ street, tottering 50 kilogram bags of cornmeal and scales appeared in several yards, so that people who couldn’t afford the 5 kilogram bag in the supermarket could at least buy enough to tide them over.

Protests and repression

Meanwhile, frustration over the government’s handling of the pandemic was boiling over. In July, the minister of Health was fired over a $60 million COVID-19 graft scandal. On the 31st of that month, demonstrations against corruption were crushed by police and the military. Activists were arrested and abducted, and a hashtag announcing the crisis, #ZimbabweanLivesMatter, lapped the globe.

“There’s so much politicization of things in Zimbabwe. There are those who profit from the suffering of others,” says Alfred. Our leaders “might talk about our other problems on TV but beneath it all there’s a lot of rot and corruption and that’s what’s killing us.”

Then, on Oct. 5, the family answered a knock at their door and were handed the city’s demolition order.

It was an echo of 2005, when six extended rooms they had added to their house were flattened as part of Mr. Mugabe’s Operation Murambatsvina, or “drive out the filth.” The demolitions displaced around 700,000 Zimbabweans in an effort to stop cities’ boom in informal growth – and, many suspected, punish the urban voters who supported the country’s main opposition party.

It took the Simbis two years to rebuild, with the help of Oxfam and other nongovernmental organizations. Now, under a new government, it was the same story.

“This house is mine, I have all the papers, but now they want to break it down. Where am I supposed to go?” Angela asks.

For the Simbis, it’s only deepened the sense that little has changed.

“There is no new Zimbabwe we have entered,” says Alfred. “We are going nowhere.”

Difference-maker

The quiet powerhouse fighting racism in one of America’s whitest states

As Vermont’s first executive director of racial equity, Xusana Davis is conducting a comprehensive review of state government. She says she's starting with something radically simple: listening.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

-

By Gareth Henderson Correspondent

In the days following George Floyd’s killing, the nation found itself in deep reflection and discussion on racial justice. Conversation, commentary, and social media posts on the topic reached a crescendo in the weeks following the incident.

But amid all the discussions on race, Xusana Davis, Vermont’s first executive director of racial equity, is focused on listening. “I always try to listen nonjudgmentally,” Ms. Davis says. “I’m really not interested in dwelling on a person’s current or past opinions. I’d rather help them get to a higher level of inquiry and action instead.”

That is the spirit Ms. Davis brought to Vermont in the summer of 2019 when she embarked on this herculean task: to conduct a comprehensive review of state government to identify systemic racism and address inequities in this New England state, which is 94% white.

Ms. Davis has helped to coordinate the translation and dissemination of public health information, assisted essential workers seeking help, and addressed gaps in data collection. Lawmakers have also passed several policing-related bills this year, including one banning chokeholds.

“The most progress being made,” however, says Ms. Davis, “is in one of the more difficult initial steps: having the conversation, and having it with sincerity.”

The quiet powerhouse fighting racism in one of America’s whitest states

In the days following George Floyd’s killing, Xusana Davis’ office in Vermont was flooded with calls and emails, as the nation suddenly found itself in deep reflection on racial justice. Ms. Davis, Vermont’s first executive director of racial equity, says a number of her colleagues in state government want to be part of the solution.

“A lot of people who ordinarily wouldn’t have reached out did reach out, and wondered whether what they were doing was enough, whether it was causing harm, and what else they could be doing,” Ms. Davis says.

Amid the discussions on race, Ms. Davis is focused on listening. She communicates with a diverse range of people, from refugees resettled in Vermont to lifelong Vermonters just learning about the impact of racism. Some people may be hesitant to talk about race in today’s climate.

“To combat this, I always try to listen nonjudgmentally,” Ms. Davis says. “I’m really not interested in dwelling on a person’s current or past opinions. I’d rather help them get to a higher level of inquiry and action instead.”

Ms. Davis officially started work in the summer of 2019 in this Cabinet-level post, after leaving a job as a top official in the New York City health department. One of her main duties in Vermont: to conduct a comprehensive review of state government to identify systemic racism and address those inequities.

Vermont, a state that is 94% white, is facing its own struggles with racism, from the intense racial harassment of lawmaker Kiah Morris, which led her to resign in 2018, to vandalism of Black Lives Matter murals painted on streets this year. More recently, Tabitha Moore, president of the Rutland Area NAACP, is moving out of her home due to continued racial harassment directed at her and her teenage daughter.

Ms. Moore is a member of a statewide Racial Equity Task Force formed this year, which Ms. Davis chairs. Ms. Moore and numerous other advocates urged lawmakers to pursue the legislation that created the state’s executive director of racial equity position.

“It’s the first real crack in the glass ceiling of government administration in Vermont related to systemic racism,” Ms. Moore says. “It’s critical; it’s beyond necessary.”

So far, Ms. Davis says she’s encountered a lot of openness to her work. After Mr. Floyd was killed in Minneapolis, she says many individuals, particularly white people, “got the message” that staying neutral was not enough, and that it is actually part of the problem.

“That neutrality really is tacit acceptance of disparate systems,” she says.

The need for racial equity has become more acute during the COVID-19 pandemic, as Vermonters of color have been disproportionately affected by the pandemic – which tracks with national trends. Ms. Davis has helped to coordinate the translation and dissemination of public health information, assisted essential workers seeking help, and addressed gaps in data collection, according to Rep. Kevin Christie, who chairs the Vermont Human Rights Commission.

“She was instrumental in keeping an eye on how well we were doing, and being that point of access for folks who didn’t know where else to go,” says Mr. Christie, who was a lead sponsor for the 2018 legislation that created the position of executive director of racial equity.

The early years

Ms. Davis was born in White Plains, New York, the first generation in her family to be born in the United States. Both of her parents are from the Dominican Republic and experienced discrimination in the U.S. due to their accents, so they were particular about how Ms. Davis and her brother learned to speak English.

“As a young child, I grew up in a predominantly African American area, and then as an adolescent moved to a predominantly white area, so I always felt different from those around me,” Ms. Davis says.

Over time, she would embrace that difference and work toward building racial equity and diversity.

Ms. Davis earned her law degree from New York Law School, with a concentration in international human rights law. There, she directed a civil liberties education program for low-income and minority youth. She didn’t trust the system, she says, “so I figured I’d go work in the system and pursue change from within.”

She eventually landed a job as the director of health and housing strategic initiatives for the New York City health department.

“It was really liaising with the program leads around the city,” Ms. Davis says.

Leading with respect

In Vermont, Ms. Davis is continuing the work of building relationships with stakeholders to address systemic racism in government. Those who work with her praise her approach. She can take strong stances on the issues while also knowing how to relate well to people and listen, Ms. Moore observes.

“One of the things I noticed first was her sense of respect for everyone in the room,” Ms. Moore says. “She commands a presence, but she’s quiet and thoughtful.”

“When she talks to people she doesn’t mince words, and she doesn’t gloss over things,” adds state Sen. Jeanette White, who chairs the Vermont Senate Government Operations Committee, which played a key role in crafting the legislation that created Ms. Davis’ position.

As Ms. Davis continues her work, the state must provide funding and resources for it, advocates emphasize.

So far, the state allocated $50,000 in its first-quarter budget for hiring data analysts for racial equity work, according to Ms. White, who says $100,000 in federal COVID-19 relief funds was also directed to the office.

Data continues to be a key focus. Ms. Davis worked with the state Health Department, which has had a deep focus on equity for years, as they recovered some race-based data regarding COVID-19’s impact. The state presented its findings in September, showing that Vermont’s population of Black and Indigenous people and other minorities, which is 6% of the state’s total population, accounted for nearly a quarter of the state’s COVID-19 cases. This shows the importance of having new eyes on this data, Ms. Moore says.

“If you look at [the data] through the same privileged lens, you’re never going to understand why the numbers are the way they are and what the true impact is,” she says.

Going forward, there’s a lot of momentum on equity issues, Mr. Christie says. Lawmakers passed several policing-related bills this year, including one banning chokeholds. Another bill directs a legislative committee to discuss improving the collection of data on how key statewide issues affect Black and Indigenous people and other minorities, according to Mr. Christie.

“What gives me hope is the number of bills that were passed that strongly address a lot of the issues that have emerged this summer,” Mr. Christie says.

Though Ms. Davis says several bills fell short of her expectations, she noticed lawmakers and state leaders discussing and taking action on racial equity.

“The most progress being made is in one of the more difficult initial steps: having the conversation, and having it with sincerity,” she says.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

A US election that redefines global leadership

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

Almost every U.S. presidential election is historic, but the 2020 one is unique in a special way: Both major candidates are foreign-policy doves. Each promises to end overseas wars, push allies to pay more for their defense, and be skeptical of free trade pacts. In other words, three decades after the United States became the world’s sole superpower, an election may see it choose to shed global power.

This election will thus reshape global leadership away from the U.S. and toward other nations. Many of them are already preparing for the task. More than any other place, Europe has recognized the challenge. As the U.S. alters its role, “we in Europe and especially in Germany need to take on more responsibility,” German Chancellor Angela Merkel told the Financial Times.

Here’s why this global shift is so important: Even if the U.S. partially withdraws even more after the election, the drive to reflect universal values in global governance will continue. Like a superpower, the ideals that the U.S. helped implant over the past century are now leading as much as any country or person can.

A US election that redefines global leadership

Almost every U.S. presidential election is historic, but the 2020 one is unique in a special way: Both major candidates are foreign-policy doves. Each promises to end overseas wars, push allies to pay more for their defense, and be skeptical of free trade pacts. In other words, three decades after the United States became the world’s sole superpower, an election may see it choose to shed global power.

Former Vice President Joe Biden, for example, wants to “end the forever wars in Afghanistan and the Middle East,” something President Donald Trump has tried to do for nearly four years. Each has concerns about a proposed trade deal among Pacific nations. And each wants Europe to rely less on American security forces.

To be sure, Mr. Biden would still display classic U.S. leadership on climate change, the pandemic, and a few other global issues. But his reputation in Washington is that of someone who prefers American retrenchment in order to focus on domestic issues, especially with rising concerns about racial justice and poverty. Like Mr. Trump, he reads the polls showing nearly half of Americans want to lower the number of U.S. troops in Asia, Europe, and the Middle East.

This election is thus historic in reshaping global leadership away from the U.S. and toward other nations. Many of them are already preparing for the task. Japan, for example, is trying to uphold free trade in Asia. More nations are forming regional pacts on security and the environment. Others hope to revive international bodies, such as the World Trade Organization.

More than any other place, Europe has recognized the leadership challenge. Last year, the European Commission decided that the continent must take on a strong “geopolitical” role. This includes setting up a European military force to complement NATO, defining the West’s response to China, setting privacy rules for tech giants, and lifting up African nations to slow migration.

As the U.S. alters its role, “we in Europe and especially in Germany need to take on more responsibility,” German Chancellor Angela Merkel told the Financial Times. “I’m guided by the firm conviction that the best win-win situations occur when partnerships of benefit to both sides are put into practice worldwide. This idea is under increasing pressure,” she said. Germany plans to push for reform of global institutions – such as the United Nations and WTO – that the U.S. helped set up.

Here’s why this global shift is so important: Even if the U.S. partially withdraws even more after the election, the drive to reflect universal values in global governance will continue. Like a superpower, the ideals that the U.S. helped implant over the past century are now leading as much as any country or person can.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

To win the soul of all nations

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 4 Min. )

-

By Tony Lobl

In heated political times such as these, it’s worth taking a deeper look at what constitutes the true Soul of a nation, our role in bringing it to light, and what that means for peace and progress. Adapted from an article written some time ago, this piece feels as relevant today as ever.

To win the soul of all nations

On Nov. 3, American voters will decide whether sitting President Donald Trump or former Vice President Joe Biden will be their nation’s president for the next four years. This election is generating intense interest globally, and the results will impact all corners of the planet. Among other things, it’s been said by folks on both sides that the election is a “battle for the soul of America.”

What defines the soul of America – or any nation? Policies adopted by a particular executive? Creative tension among the checks and balances of executive, legislative, and judiciary? Decisions made by Supreme Court justices? The hard-won Constitution and Bill of Rights undergirding all these? Or is it something even deeper than that?

If the soul of an individual or a nation can change, then there is no North Star to be guided by, no defining character to aspire to. If, on the other hand, the soul is changeless and enduring, then there exists an ideal that calls for increased recognition and adoption as time invites and accommodates progress and growth.

Christian Science points to the existence of such a changeless Soul – divine Soul, or God. This Science is a wholly spiritual explanation of individual and universal reality, as proved by Jesus and systematically laid out in “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures” by Mary Baker Eddy. Christian Science explains the nature of this eternal Soul as supremely good, all-blessing, and indestructible.

There is no fragility to divine Soul, and so there is no genuine Soul to anything that appears vulnerable to the vagaries of passing time and changing power structures. Where Soul is there is permanency, and its creation expresses its unfluctuating nature.

This changeless goodness – the spiritual reality of all men, women, and children – is not political or partisan. It is the spiritual expression of God’s impartial and universal love. Prayer that glimpses this truth identifies as misguided the notion that a particular political orientation could have a monopoly on Soul, and promotes the relinquishing of such views. This, in turn, enables our meek recognition of Soul’s gracious qualities, evidenced in diverse candidates and parties, and among the electorate at large.

That doesn’t mean it’s wrong for individuals to feel moved to support a particular candidate or a set of policies they feel should triumph. It will, though, temper human passions and temptations to demonize opponents, so that Soul’s sense of the dignity of all creation remains center-stage in informing attitudes and motivating action.

So, perhaps the real question is: Does Soul need to be battled for in the U.S., or in any nation facing elections?

Yes and no.

If there is resistance to all that divine Soul is and expresses, there is a need to join in battle, through prayer that seeks to understand Soul’s universally perfect ideas, so that they might come to light and take shape in the betterment of human experience.

But that battle doesn’t need to be – cannot be – joined in the name of polarities, either political or denominational. Rather, the battle is joined against the impositions of what the Bible calls “the carnal mind,” which presents as unavoidable (in oneself or others) traits such as ill-temper, greed, fear, or self-will (see Romans 8:7). This battle is fought on the basis of claiming our innate ability to see, through spiritual perception, the universal perfection that God, the divine Mind, sees.

We might find these prayers leading to certain political victories or decisions – even those of a candidate we didn’t prefer! Or Soul’s ingenuity might find myriad other ways to substantiate its claims on humanity’s attention and well-being. In Science and Health, Mary Baker Eddy wrote, “Soul has infinite resources with which to bless mankind, and happiness would be more readily attained and would be more secure in our keeping, if sought in Soul” (p. 60).

Seeking a nation’s happiness in Soul, as well as our own individual happiness, provides that North Star, a defining character to which all can aspire. In Soul we discover rich promise and satisfaction in qualities such as humility, courage, creativity, freshness, honesty, holiness, wholesomeness. A nation will express Soul more as its citizens – including candidates to elective posts – increasingly value and express these qualities and live them.

This will help to increasingly secure national and global happiness as it truly exists – for one and all.

Adapted from an article published in the Nov. 3, 2008, issue of the Christian Science Sentinel.

Some more great ideas! To hear a podcast discussion about overcoming fear of contagion during a global pandemic, please click through to the latest edition of Sentinel Watch on www.JSH-Online.com titled, “Mastering pandemic fears with spiritual truth.” There is no paywall for this podcast.

A message of love

Search for survivors

A look ahead

Thank you for starting your week with us. Tomorrow, you can meet the two Janets – a story, written by Christa Case Bryant, of college friends whose politics diverged widely over the decades. Yet their bonds are as strong as ever, even though they often vehemently disagree. I hope you’ll check it out.