- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 8 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- Tight race tests Americans’ trust in system – and each other

- Huge turnout, close race: The day-after lessons of Election 2020

- As remote learning spreads, so have cyberattacks. Schools get ready.

- Joining an anti-racist book club? Don’t get too comfortable in that armchair.

- Want to prevent wildfires? Try getting someone's goat.

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Lessons from Pooh Corner: Can America be patient?

Election Day has come and gone. But the recounts and legal battles may take weeks to resolve.

In the land of instant gratification, Instagram, and same-day Amazon delivery, our patience with the democratic process is being tested.

One of the lessons of this election may be that America hasn’t changed much since 2016. The political and moral divides are deeply etched. Each side will be tempted to feel justified in declaring victory. If Joe Biden wins, it may be hard for President Donald Trump’s supporters not to feel the election was rigged: Their candidate said so. If Mr. Trump wins, the shadow of the 2000 Gore-Bush race looms large: Nice guys finish last.

That’s why at least 16 states have the National Guard on standby.

But patience is a virtue often associated with maturity. It’s the ability to wait and to hold our impulses in check. It’s about self-government. Yes, freedom of speech and protest are basic democratic tenets. But so is the rule of law. This period of post-election uncertainty is a time to pause, and trust the process, even if we don’t trust the other side. (See our story below.)

In “The House at Pooh Corner,” A.A. Milne describes a stream that has grown into a river. “Being a grown-up, it ... moved more slowly. For it knew now where it was going, and it said to itself, ‘There is no hurry. We shall get there some day.’”

It’s river time, America.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Tight race tests Americans’ trust in system – and each other

After an election that’s produced record engagement, our reporters look at why American voters are wrestling with confidence in the integrity of the process and with trusting their political neighbors.

-

Story Hinckley Staff writer

-

Noah Robertson Staff writer

How strong is Americans’ trust in the U.S. electoral system? That’s the test the country faces in the coming days and possibly weeks, as election officials and potentially courts work to determine the winner of this year’s presidential election.

Amid one of the most logistically challenging and tightly contested elections in years, voters across the country are worried about everything from ballots getting lost to deceptive robocalls that told people to stay home on Election Day. But in dozens of Monitor interviews from Salem, New Hampshire, to Santa Clarita, California, perhaps the clearest refrain was: We don’t trust the other side to accept the results.

A 2019 Pew survey found that while 53% of Americans express confidence that their fellow citizens will accept election results no matter who wins, 47% said they have “not too much” or “no confidence at all.”

“It’s important that the next president be a statesman and appeal to our better angels and try ... [to] make it possible for us to talk to each other again, regard each other with goodwill again, because democracy is going to be weakened the further we stray from that ideal,” says David Greenberg, a presidential historian at Rutgers University.

Tight race tests Americans’ trust in system – and each other

Amid one of the most logistically challenging and tightly contested elections in years, voters across the country are worried about everything from ballots getting lost to deceptive robocalls that told people to stay home on Election Day. But for many, their greatest fears have less to do with machines or mechanisms than with their fellow Americans.

“I think that Trump supporters will be more supportive if Biden wins than Biden supporters if Trump wins,” says Tabitha McQuait, standing in a field across from a brick church in Goldsboro, Pennsylvania, where dozens of voters have parked haphazardly in the grass.

“Sadly, I agree,” says her mom, Julie McQuait, echoing concerns voiced by Democrats as well. “Whichever candidate wins, I think the other party is going to take it poorly.”

“My question is ... why don’t they have an auditing firm like Deloitte or somebody that comes in and oversees us?” asks the elder Ms. McQuait, who works at a local Fortune 500 company. “They oversee the lottery, why shouldn’t they oversee something as important as our country?”

With the presidential race far closer than polls had predicted, and likely to hinge on a few narrowly contested swing states still tallying their ballots, the wait for an official result could test Americans’ trust in the system – and each other – like never before.

In the two decades since the Supreme Court intervened to resolve Florida’s hanging chad controversy and put George W. Bush in the White House, increased political polarization has frayed the nation’s collective sense of trust and goodwill. Amid declining faith in institutions, the media, pollsters, and each other, the possibility of a disputed electoral outcome may only fuel Americans’ sense of suspicion and cynicism.

“One of the things that allows people to accept laws that are made and to accept the decisions made by their leaders is the acceptance that those leaders are there legitimately, whether they voted for them or not,” says Ryan Enos, a professor of government at Harvard University. “It’s really hard for society to function peacefully and for people to trust one another and many other things when they don’t believe that the people that are making laws for them are legitimate.”

As of Wednesday afternoon, both candidates had a potential path to victory. But with outstanding votes in several key states expected to be heavily Democratic, Mr. Biden was seen as in a stronger position to win the needed 270 Electoral College votes, especially after swing state Wisconsin was called for him mid-afternoon. President Donald Trump, who has for months been sowing doubt about the reliability of mass mail-in voting, vowed in a speech in the wee hours of the morning to contest the results in the Supreme Court. (Any legal challenge would have to start in a lower court and be appealed to be considered by the nation’s highest court.)

Pennsylvania – a closely contested state that last year enacted its most sweeping legislation on election administration in 80 years and overhauled voting systems in all 67 counties – could prove particularly messy. A 4-4 Supreme Court ruling on the eve of the election opened the way for the state to extend the deadline for receipt of mail-in votes to Friday, a move Republicans opposed. With recently confirmed Trump nominee Amy Coney Barrett now filling the ninth seat, a fresh case may yield a different decision.

“It’s just going to be just like back in Gore-Bush’s day, I got a feeling,” says Terry Morgan, a dock worker for a trucking company who voted for former Vice President Joe Biden in Goldsboro, Pennsylvania. “It’s going to take awhile to figure it out. One of the candidates is going to say, ‘I want this recounted.’”

In fact, the Trump campaign announced Wednesday it planned to immediately request a recount in Wisconsin, where Mr. Biden was up about 20,000 votes. The former vice president is also leading the popular vote, with more votes than any candidate in U.S. history, which would make an Electoral College win for Mr. Trump even more difficult for liberal voters to swallow.

Voting amid a pandemic

From Salem, New Hampshire, to Santa Clarita, California, many voters leaving the polls on Election Day had concerns about the U.S. electoral system in this unusual election, held amid a pandemic.

One of the top logistical problems cited was around mail-in ballots.

Eli Bomer and his wife, who both voted for Mr. Trump, say they have confidence in the election process. Still, they came in person to vote at Wiley Canyon Elementary School in Santa Clarita because last time, they say, their absentee ballots were not counted.

Although Democrats more readily embraced mail-in voting, concerns about its reliability reach across the political spectrum.

“Anything can happen in the mail,” says Yousef Murden, an African American sheet metal worker with gold sneakers and camo pants outside a Staten Island, New York, polling station where he voted for Mr. Biden. “If I actually go vote on my own, I know it’s been counted.”

In Pennsylvania, nine military ballots – all for Mr. Trump – were discarded, while up to 100 deposited in a California ballot box were damaged in an arson attempt. Then there’s the question of how many mail-in ballots might ultimately be invalidated.

Many states have signature-matching requirements, as well as postmark or arrival deadlines and other rules governing what constitutes a valid mailed ballot. Some of those laws have been challenged or changed on relatively short notice this year, in part due to concerns about in-person voting during a pandemic.

In Texas, where a legal challenge by four Republicans to toss out 127,000 ballots cast at drive-through polling sites failed in state and federal court, Austin voter Dené Cloud said her faith in the electoral process had been shaken by “people in positions of power trying to use any and every means to disqualify votes.”

Beyond concerns about the administration of the election, many voters are also worried that voters on the other side of the aisle won’t accept the results. A 2019 Pew Research Center survey found that while 53% of Americans express confidence that their fellow citizens will accept election results no matter who wins, 47% said they have “not too much” or “no confidence at all.”

“I don’t think it’s going to be very pretty if Mr. Trump wins,” says Veronica Linehan, a New Hampshire voter who says her brother disowned her after she voted for Mr. Trump in 2016. “[Democrats] just wouldn’t be able to accept it. It took four years and they still don’t accept that he’s president.”

Some experts trace that lack of faith to 2016, or President Barack Obama’s first victory in 2008, or even Mr. Bush’s 2000 win, when he captured Florida by just 537 votes after the Supreme Court halted a recount.

John, a voter in Brooklyn, who didn’t want to give his last name, says he was hoping for a landslide this year to spare confusion. But he says he believes civil unrest is inevitable no matter who wins. He voted for Mr. Trump in 2016, but says the president’s mishandling of the pandemic – in which he lost three co-workers and extended family, as well as his job – made him change his vote to Mr. Biden, whom he sees as the best candidate to unite a fractured nation. “Let’s start repairing – regardless of who wins,” he says.

When both sides think they’ve won

Twice in U.S. history, no presidential candidate received a majority of electors: the 1800 contest between Thomas Jefferson and John Adams, and the four-way runoff with Andrew Jackson and John Quincy Adams in 1824. It took months for those elections to be sorted out, says David Greenberg, a presidential historian at Rutgers University in New Jersey.

But a disputed election today comes in the context of building frustration and a widening partisan divide since the Bush versus Gore contest in 2000. The closer the election, the more ardent the claims of illegitimacy, says Professor Greenberg.

“Both sides right now are convinced they’re the rightful winners, even though they don’t know for sure,” he says. “So whichever way it breaks, people are going to be deeply, viscerally convinced that the country has been hijacked.”

Many voters interviewed by the Monitor expressed concern that the situation could spill over into civil unrest, with store owners from Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, to Portland, Oregon, preemptively boarding up their windows after a summer that saw many businesses damaged or looted amid the national protests over racial injustice.

“If you’re burning stuff down, you’re looting, you’re hurting people, that’s what’s going to divide the country. That’s what’s going to make people not accept election results,” says Steven Mosley, an African American voter wearing a Republican elephant mask outside a polling station in Alexandria, Virginia. “But if you just accept it and go, ‘OK, well I disagree. I’ll see you again in four years,’ that will unite the country.”

The narrowly contested election, with possible legal challenges and concerns about the potential for violence, puts even more pressure on the eventual winner to bring the country together.

“It’s important that the next president be a statesman and appeal to our better angels and try at least to shift our political culture and make it possible for us to talk to each other again, regard each other with goodwill again, because democracy is going to be weakened the further we stray from that ideal,” says Professor Greenberg.

For those feeling a sense of impending dread about how this all may play out, presidential historian Allan Lichtman insists that while there might be a lot of hand-wringing and maybe even some outbreaks of violence, whoever wins the Electoral College will become president – just as in the Bush versus Gore battle.

“We thought that [the system was breaking] in 2000 – and it didn’t turn out that way at all,” says Professor Lichtman, of American University. “Bush ... had all the powers and prerogatives of the president and exercised them to the full. There was some griping and groaning, but the system worked.”

Christa Case Bryant contributed reporting from New Hampshire, Story Hinckley from Pennsylvania, and Noah Robertson from Virginia. Staff writers Sarah Matusek contributed reporting from New York, Henry Gass from Texas, and Francine Kiefer from California.

Huge turnout, close race: The day-after lessons of Election 2020

Most pundits and pollsters badly miscalculated what would happen in this election. Our reporter looks at some upended expectations, false narratives, and new insights revealed by American voters on Nov. 3.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

Americans voted in astounding numbers in the 2020 election, with preliminary estimates showing the highest percentage turnout in 120 years.

But the hopes and fears that pushed so many people to cast ballots are deeply divided along partisan lines. The result seems almost certain to be a nation of warring political camps of almost equal size and power, facing a pandemic and recession that neither can fight successfully on its own.

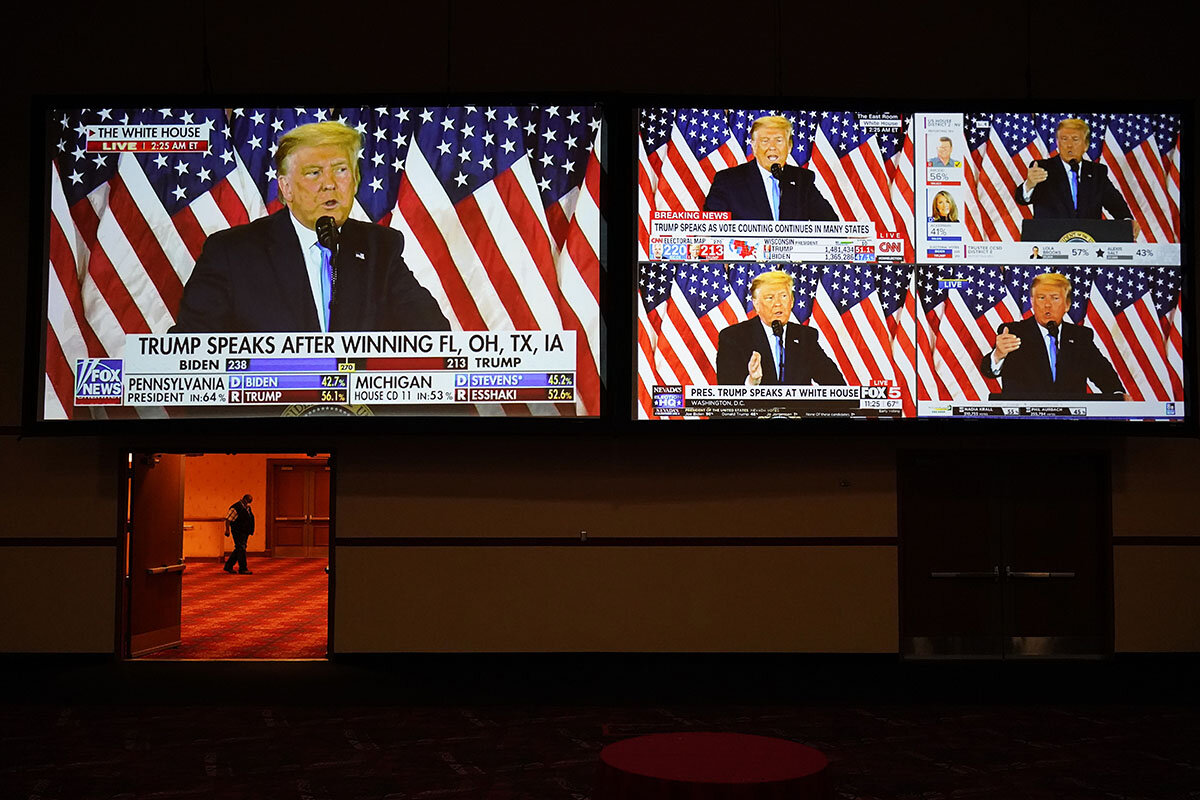

President Donald Trump deepened the tension with his false 2 a.m. Wednesday pronouncement that he had already won the election, and his unprecedented insistence that states should stop counting legally cast votes.

“That is in many ways an unprecedented undermining of the electoral process,” says Ryan Enos, a professor of government at Harvard University.

Despite this, Mr. Trump seemed likely to benefit politically from the overperformance of the Republican Party against expectations – whether he remains in the White House or not.

Though the race may not be resolved for days, Democratic candidate Joe Biden’s prospects appeared somewhat brighter than the president’s. Mr. Biden’s best path to victory involves holding onto narrow leads in Arizona, Nevada, Wisconsin, and Michigan, with a possible come-from-behind win in Pennsylvania as a backup. Mr. Trump’s best shot involves holding Georgia, Pennsylvania, and North Carolina, and flipping Arizona.

Huge turnout, close race: The day-after lessons of Election 2020

Mail-in, drop-off, in-person early, in-person on Election Day: Americans voted in astounding numbers in the 2020 election, with preliminary estimates showing the highest percentage turnout in 120 years.

But the hopes and fears that pushed so many people to cast ballots are deeply divided along partisan lines. The result seems almost certain to be a nation of warring political camps of almost equal size and power, both full of pent-up emotion, facing a pandemic and recession that neither can fight successfully on its own.

President Donald Trump deepened the tension with his false 2 a.m. Wednesday pronouncement that he had already won the election, and his unprecedented insistence that states should stop counting legally cast votes.

All candidates aim to project confidence, but President Trump’s accusation that tallying legitimate ballots amounts to “stealing the election” is extremely worrisome, says Ryan Enos, a professor of government at Harvard University.

“That is in many ways an unprecedented undermining of the electoral process,” says Dr. Enos.

Win or lose, Trump outperformed predictions

Despite this, Mr. Trump seemed likely to benefit politically from the overperformance of the Republican Party against expectations – whether he remains in the White House or not.

While polls indicated Mr. Trump would lose handily to former Vice President Joe Biden on election night, the race remained too close to call late Wednesday and may not be resolved for days, though Mr. Biden’s prospects appeared somewhat brighter than the president’s.

After snaring thin victories in Wisconsin and Michigan, Mr. Biden’s best path to victory involves holding onto narrow leads in Arizona and Nevada, with a possible come-from-behind win in Pennsylvania as a backup. Trump’s best shot involves holding Georgia, Pennsylvania, and North Carolina, and snagging Arizona.

The president’s strategy also appears to include aggressive legal challenges. On Wednesday his campaign announced that it was suing to temporarily stop ballot counting in Michigan and Pennsylvania on the grounds that the process was not transparent enough.

His campaign also is trying to intervene in a Pennsylvania case at the Supreme Court, on whether ballots received up to three days after the election can be counted, the Associated Press reports.

Campaign officials also said they were seeking a recount of the result in Wisconsin, which like Michigan was called for Biden Wednesday afternoon.

Meanwhile, it seems possible, if not likely, that the GOP will maintain its hold on the Senate. Pre-election polls had indicated Democrats were the favorite to win a slim majority. In the House, Republicans knocked off at least six vulnerable Democrats – instead of losing a net five to fifteen seats, as polls had predicted.

Given these results, Mr. Trump seems set to remain the dominant force in the party. If he loses it’s not hard to imagine him as the head of a sort of shadow government that unleashes a daily stream of criticism of the Biden administration through conservative media outlets.

Failing grade for pollsters

The polling industry appears to have taken another beating this election cycle. The final spread between Messrs. Trump and Biden may end up being within the margin of error of many national polls, given that millions of votes in California and other large states that aren’t close remain to be counted. But as in 2016, some state polls and surveys for individual races showed substantial errors.

Moderate Maine Republican Sen. Susan Collins’ reelection victory is one example of this. Democrats targeted Senator Collins for possible defeat over her votes to confirm Brett Kavanaugh to the Supreme Court and acquit President Trump in his impeachment trial. She faced a formidable opponent in Sara Gideon, speaker of the Maine House of Representatives. Over the past year, polling consistently showed Senator Collins behind.

She won by almost 9 percentage points.

Latino and Hispanic Americans saw their candidate preferences badly missed by polls and pundits. They were far from a united group opposed to Mr. Trump’s harsh treatment of unauthorized immigrants and appalled by his insistence on building his southern border wall.

Mr. Biden never really connected with them, and the costs of that were apparent in battleground Florida. President Trump won 55% of the state’s Cuban American vote, 30% of its Puerto Rican Americans, and 48%of “other Latinos” on his way to winning Florida’s 29 electoral votes.

One thing seems almost certain: Mr. Biden will win the popular vote, becoming the fourth Democratic candidate in a row to do so. This hasn’t been done since the four election cycles beginning in 1936, with Franklin Delano Roosevelt, followed by Harry Truman on the ballot.

As remote learning spreads, so have cyberattacks. Schools get ready.

Districts are learning lessons that will serve them after the pandemic, such as how to thwart hackers. We look at schools that are rising to the challenge and countering these new threats.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Cyberattacks this fall across the U.S. have caused school districts to delay the start of school, cancel classes, and in some cases, resulted in the release of sensitive staff and student data.

Security experts say that K-12 education is increasingly targeted by criminals who are drawn by the rich trove of sensitive data held by districts and their historically weak online defenses. In 2019, for example, public schools in the U.S. recorded 348 cybersecurity incidents, according to one report, a three-fold increase from the prior year. This year’s totals may surpass that.

The unprecedented reliance on remote learning during the pandemic has further emboldened attackers. Increased use of devices at home creates more avenues for cyberattack.

The silver lining: Schools are viewing cybersecurity as a priority. From using strong passwords and multifactor authentication to storing data in a mix of virtual and on-site secure locations, districts are taking action to thwart attacks. Says Jeff Pelzel, superintendent of the Newhall School District in Santa Clarita, California: “I tell everyone now that there are things right away that you can do.”

As remote learning spreads, so have cyberattacks. Schools get ready.

Students in the Newhall School District in Santa Clarita, California, were just hitting a rhythm with remote learning this fall when the district suddenly had to cancel online classes in mid-September due to a cyberattack that shut down the entire district computer network.

In a typical year, such an attack would result in teachers turning off technology and shifting lessons to the classroom, but that’s not an option with remote learning, says Superintendent Jeff Pelzel.

“In this situation, the challenge was our kids didn’t get to interact with their teachers on a daily basis with live instruction,” he says. “And on the back end, we lost access to our drives. It’s never easy when you get shut down.”

Cyberattacks this fall across the U.S. have caused school districts to delay the start of school, cancel classes, and in some cases, resulted in the release of sensitive staff and student data. Cybersecurity experts say that K-12 education is increasingly targeted by criminals who are drawn by the rich trove of sensitive data held by school districts and their historically weak online defenses.

The unprecedented reliance on remote learning during the pandemic has further emboldened hackers. Increased use of student and staff devices at home creates more avenues for cyberattack. Technology leaders are making years worth of changes rapidly, sometimes leading to less secure use of new applications. They warn that schools should anticipate further attacks, but also say that incidents can be reduced by better training and investing in strong cybersecurity defenses.

“I think there’s clearly a shift,” with school superintendents and school boards viewing cybersecurity as a priority now, says Keith Krueger, CEO at the Consortium for School Networking (CoSN), a professional association for school technology leaders. “Especially with front page problems of networks failing or being attacked all around the country.”

Spike in attacks

Recent high-profile cases include one in Miami-Dade County Public Schools in Florida, where a local teenager was arrested in September on charges of launching multiple attacks that flooded the district’s online learning system with internet traffic and prevented thousands of students from logging in to class.

Clark County School District in Las Vegas refused to pay a ransomware attack on its system in August, which reportedly resulted in the release of sensitive data, including employee Social Security numbers and student mailing addresses. Ponca City Public Schools in Oklahoma and Hartford Public Schools in Connecticut delayed the start of their school years after cyberattacks.

The number and intensity of cyberattacks on school districts has increased for several years, says Doug Levin, an education consultant from Arlington, Virginia, who tracks cyberattacks on public K-12 school districts.

In 2019, Mr. Levin recorded 348 cybersecurity incidents, a three-fold increase from the prior year. This year the number of cyberattacks dwindled during the first few months of the pandemic, but have shot up since the start of the school year and, if trends continue, may surpass last year’s totals.

“It is a challenge for school districts no doubt,” says Mr. Levin. “Unfortunately the issue of cybersecurity has not been a priority by and large in schools.”

For Chris Gaines, the superintendent of Mehlville School District in St. Louis, the importance of cybersecurity best practices was reinforced this August when hackers overtook the email account of a construction company the district worked with and misdirected a $334,000 payment, according to Mr. Gaines. The district recouped most of the money, but is still working to get the last $75,000.

“It boils down to human behavior is what allows access,” says Dr. Gaines, who initiated new business office protocols after this incident and a prior one, in which an individual tried unsuccessfully to use a hacked email account to change Dr. Gaines’ personal direct deposit account.

Cybersecurity solutions

Mehlville Schools invests in cybersecurity by paying for cyberliability insurance, as well as hiring firms to deliberately conduct attacks to spot weaknesses. The district trains employees by running phishing campaigns to see if staff click on fraudulent links. Since the training, staff clicking on faulty links – one of the most common ways that cyberattacks begin – fell from 25%-30% to just 4%, says Dr. Gaines.

School districts, like other local government entities, are often attractive targets because of the likelihood they are using older technology, relying on small IT teams, and holding sensitive data.

Vicki Anderson, a special agent with the FBI in Cleveland, says the FBI released a warning this summer to school districts nationwide about cybersecurity attacks during remote learning. She recommends that districts take preventative steps like training staff and students to use strong passwords and not to click on suspect links. The FBI advises schools not to pay ransomware attacks and instead get in touch with them immediately.

Groups like CoSN, the school technology association, are helping superintendents, school boards, and technology directors with cybersecurity by providing resources such as tip sheets and training. They’re also lobbying the Federal Communications Commission to allow cybersecurity to be covered under eligible services in the $4 billion E-rate program, a major source of funding for school technology.

Mr. Krueger of CoSN says that school districts vary greatly in their ability to provide cybersecurity, with small and rural districts less likely to have the resources or expertise to enact strong policies. He also notes that the nation’s troubling digital divide extends to cybersecurity.

“We have to have the third leg of the stool, and that is secure broadband internet access,” along with enough devices and wireless connectivity for students, he says.

Back at Newhall Schools in California, the district is working with an outside forensics team to restore access to their network drives. Teachers resumed live online lessons about 10 days after the ransomware attack. No student or employee data appears to have been released.

Mr. Pelzel, the superintendent, says the experience was disconcerting for staff and families, and exhausting for the IT department working overtime. But “the silver lining out of this is you get lessons learned and things you can do to upgrade and support.” The district is reevaluating its cybersecurity and plans to take recommendations to its governing board.

From using strong passwords and multifactor authentication to storing data in a mix of virtual and on-site secure locations, districts are taking action to thwart attacks. “I tell everyone now that there are things right away that you can do,” Mr. Pelzel says.

Books

Joining an anti-racist book club? Don’t get too comfortable in that armchair.

In our next story, we look at the rise of anti-racist book clubs as a response to this summer’s protests. But there’s more. Readers are moving from discussion to action, as these clubs become seedbeds of social change.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

During this summer’s protests over police killings of Black men and women, sales of books about race skyrocketed. And people weren’t just reading them – they were talking about them. Book clubs focused on anti-racism formed around the country, and for many of them, the goal went beyond discussion to action.

As Dorsa Amir, an evolutionary anthropologist, explains, book clubs can act as “the beginning of community organization where, in addition to learning about the issues, there can be specific tasks and specific actions that can be taken,” like protesting, writing elected representatives, or raising funds.

Balancing talk and action has been important to Keidrick and Holly Roy, who co-led two book clubs. It’s easy to go back to “life as usual” after attending a single protest or talk, Mr. Roy notes. But “I began to think about what might happen if we kept the transformative spirit of protest alive through a forum that engages in these extended, long-term dialogues.”

Yet Mr. Roy is quick to add that more than talk is needed. Engaging in deep discussions about racism is necessary, but it’s not sufficient, he says. “At the same time, we have to go out and we have to act.”

Joining an anti-racist book club? Don’t get too comfortable in that armchair.

When George Floyd’s death while in police custody prompted protests, Keidrick Roy, who is Black, and his wife, Holly, who is white, saw an opportunity to help others grow their understanding of race in America – not by marching but by reading. In June, they organized two book clubs focused on anti-racism: one was secular and the other for members of City on a Hill Church in Somerville, Massachusetts, which they attend.

The clubs resembled academic courses, with detailed syllabuses and guided discussions. In both cases, people joined “because they had deep questions about the state of our country,” says Mr. Roy, a Ph.D. candidate in American studies at Harvard University. “Beyond learning how to interact with others, I also think folks joined to understand themselves and the history of our country.”

The Roys’ groups were not one-offs. After Mr. Floyd’s death in May, sales of bestselling books about race jumped as much as 6,900%, according to Forbes, and book clubs focused on anti-racism formed around the country – both in person and over Zoom. For many of these clubs, including the Roys, the goal went beyond discussion. “People talk about how they can apply the particular lessons we teach ... to their daily work,” says Mr. Roy. In other words, book clubs have become sites not only for education but also for action.

Zoom attendance at the Roys’ secular book club meetings ranged from 45 to 60 people, while the church book club drew between 25 and 40 people. Thanks to these groups, a middle school teacher figured out a way to address the racial antagonism she’s observed between her students. Others have taken the lessons they’ve learned to their bosses and organizations to revise hiring practices and policies. Some are bringing resources and materials to traditional book clubs they already belonged to.

Moving through angst to action

None of this is easy, though. And for white readers, the concept of white guilt makes it even harder – as does the daunting feeling of facing a massive undertaking when learning about racism, says Sara Brownson, who directs children’s programs at Holy Trinity Church in McLean, Virginia, and is a former teacher. She participates in two book clubs exploring anti-racism, one with 25 attendees and the other with five. Both clubs focus on Latasha Morrison’s “Be the Bridge: Pursuing God’s Heart for Racial Reconciliation,” which details Ms. Morrison’s experience as a Black woman at the intersection of race and faith and strives to equip readers to become ambassadors of racial reconciliation.

“One of the things I’ve really discovered is the difference between shame and guilt,” Ms. Brownson says. “Shame is the emotion … in your head, whereas guilt is more talking about the actions that you’ve [taken].” A big question, she says, is whether to wallow in that guilt, which can be all-consuming. “One thing that I feel has really helped me is just listening to other stories and then picking things that I can do that feel attainable.”

Balancing a sense of safety with the responsibility to act was important to the Roys as well. They wanted to create a space where people could engage with others without fear of making mistakes or saying the wrong thing, Mr. Roy comments. “We also wanted to prepare folks for calling out racism when they see it. … Not exercising one’s power to walk away from the struggle for racial justice [but] to engage in the long-term, community-building initiatives.”

Dorsa Amir, an Iranian American evolutionary anthropologist, emphasizes this progression from individual action to broader change, noting that book clubs are a great start because they form as collectives of interested and engaged people. “This is kind of the beginning of community organization where, in addition to learning about the issues, there can be specific tasks and specific actions that can be taken,” like protesting, writing elected representatives, or raising funds, says Dr. Amir, a postdoctoral research fellow in the Cooperation Lab at Boston College.

Prodding schools and churches to improve

In some cases, book clubs have formed purposely to prompt action. That was true for Eliza Perry, a white elementary school social studies teacher in Denver, Colorado, whose club met over the summer and focused on improving practices at her school. The nearly 30 participants chose to read “White Fragility,” “Raising White Kids,” or “Waking up White,” and some joined a task force focused on implementing systemic change in areas like admissions and professional development.

“Personal reflection is always where it starts,” Ms. Perry says. But she plans to use what she has learned to inform her teaching. “As an educator at a private school, I have so much more choice in what I … teach my kids,” Ms. Perry adds.

Ms. Brownson is sharing what she’s learning as well. After joining her first book club through her church, she recognized a way to take action steps of her own and began leading an additional group. Over time, “I see people more willing to jump into conversation … and not as quick to judge,” says Ms. Brownson. “And I see people’s eyes becoming a little bit more open.”

One focus of the book club at her church is reckoning with historical racism in Christian churches in the U.S. In addition, reading “Be the Bridge” with the group has opened the door for some members to share how they have experienced racism in their church recently.

That kind of openness has the potential to develop lasting connections and, perhaps, lasting change. It’s easy to go back to “life as usual” after attending a single protest or talk, Mr. Roy notes, but “part of the point of protesting is to disrupt the ordinary, to reframe how people see the world. I began to think about what might happen if we kept the transformative spirit of protest alive through a forum that engages in these extended, long-term dialogues.”

Mr. Roy is quick to add that more than talk is needed. Engaging in deep discussions about racism is necessary, but it’s not sufficient, he says. “At the same time, we have to go out and we have to act.”

Want to prevent wildfires? Try getting someone's goat.

Sometimes the best – and the least expensive – defense against wildfires is an old-school response. Our reporter talks to a Peruvian goat herder protecting a California community, bite by bite.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

To protect their multimillion-dollar homes from the state’s ferocious wildfires, residents of Laguna Beach, California, turn to a solution that is as old as the hills: goat herding.

Goatherd Agotilio Moreno’s 300 goats play a key role in the city’s fire prevention strategy, munching on the combustible grasses that cover the hillsides of this old art colony. And he knows his trade: Mr. Moreno says he can gauge the “softness” of dirt and how unstable a hill is before cloven hooves and munching can disrupt it enough to create bare spots that could erode, or, worse, slide. He knows how steep a hill a goat can handle before taking a tumble over a precipice.

It’s a good bargain, too, says Fire Marshal James Brown, who says that the city spends $250,000 a year on the goats – about a quarter of the cost of the far-less-efficient human brush-clearing. To place a value on what the goats can do, he says half-jokingly, would be to peruse Zillow and tally up the total value of homes that haven’t burned down.

“Pound for pound,” he says, “it’s hard to beat the goats.”

Want to prevent wildfires? Try getting someone's goat.

When the balmy breezes off the Pacific turn tail before the hot Santa Ana winds that bring conditions for wildfires, Agotilio Moreno’s 300 goats become very serious – but cute – talismans of hope.

Murmurs of dread floated through this old art colony recently when the Silverado wildfire erupted 20 miles away, on the other side of the 900-foot-high wilderness area that isolates the 6-mile-long beach town from the rest of Orange County. But Mr. Moreno’s goats dotting the steep hillsides here are a cheerful part of fire defense that officials and residents take seriously: “fuel reduction” – also known as voracious grazing with nimble lips and grinding teeth.

The goats have been working nearly 24 hours a day since March, clearing 90% of the biomass wherever Mr. Moreno pens them with portable electric fencing. While the goats are aimed at grasses – wildfire kindling that combusts fast and furiously – misfires happen. They particularly love flowers, and have been known to break bonds and feast on a homeowner’s expensive landscaping.

If anything has proven helpful in fending off fires, says city Fire Marshal James Brown, goats are an important tool in fire prevention here. “When a wildland fire hits, [goat fuel reduction] can be the difference between a neighborhood surviving or not, or [firefighters’] ability to get in or not get in.”

Wildfires can spark unusual alarm because of their unpredictability and uncontrollable power. So when something as simple as a lone goatherd and his flock can eliminate what stokes those fires, it feels somehow right.

After the legendary 1993 wildfire here 27 years ago last week, says Mr. Brown, it was not lost on observers that in the area where a small herd of goats had been located, no adjacent homes were lost; but 400 homes were leveled in other areas untreated by goats.

To place a value on what the goats can do, he says half-jokingly, would be to peruse Zillow for the total value of homes in Laguna Beach – a notoriously high-price real-estate market – that have not burned down. And that, he adds, isn’t even to mention the emotional toll exacted from the residents who didn’t lose homes, but who had to flee barefoot and empty-handed.

The city spends about $250,000 a year for Mr. Moreno – a contractor from a large Basque-run sheep-and-goat ranch in Riverside – to herd his goats over about 250 acres of open land. “Pound for pound, it’s hard to beat the goats,” Mr. Brown says, noting that human brush-clearing and grass-clearing, which is not as thorough, costs the city $1 million annually.

Mr. Brown speaks the language of fire science – BTUs and flame length and geology and topography. Certain grasses are “flashy,” he says, and can “pyrolyze a burn in half a second.” In other words, it explodes; and creates flame lengths of 30 to 80 feet – the kind that can shoot out horizontally and consume a car in an instant. These grasses and mustard plants that can grow 10 feet tall in the hills here are what he hires Mr. Moreno and his goats to eliminate in areas next to homes.

Mr. Moreno, on the other hand, speaks in the calculus of experience herding in the Peruvian Andes province of Huancayo. He says he can gauge the “softness” of dirt and how unstable a hill is before cloven hooves and munching can disrupt it enough to create bare spots that could erode, or, worse, slide. He knows how steep a hill a goat can handle before taking a tumble over a precipice.

The goatherd has lived a humble existence away from his wife and three now-adult and college-educated daughters for 21 years. He nomadically moves his trailer around the edges of neighborhoods, parking alongside homes with soaring multimillion dollar views of the ocean and canyons. And yet, while he says he savors this place, with the sounds of the ocean waves that echo up into the hills and the smell of wild sage and rosemary, he adds with palpable melancholy that he doesn’t really know anyone here.

But, ironically, he is known. Particularly now, in the pandemic that has driven everyone to outdoor extremes, hundreds of passing mountain bikers, soccer dads in Teslas taking canyon bends at high speed, power-walking moms, and nature-exploring school kids, can identify him and what he does to defend their community.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

The graft-busting uses of COVID-19 aid

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

With only a tenth of the world’s population, Latin America has seen more than a third of the deaths from COVID-19. This has put a spotlight on the region’s inability to curb the coronavirus or deal with the economic hardship. Experts say per capita income in Latin America will take longer than any other region to return to pre-pandemic levels.

The economic climb back, however, will require more than money. Outside creditors have put the region on notice that any aid to lift livelihoods must also lift financial integrity in government. Corruption cannot remain the norm.

The pandemic has worsened corruption in many countries, especially through embezzlement of money aimed at fighting the virus and restoring economic health. But big creditors can step up and tie their money to curbing graft. Honesty in governance contributes to curing COVID-19 and its impact as much as lockdowns, vaccines, and financial aid.

The graft-busting uses of COVID-19 aid

With only a tenth of the world’s population, Latin America has seen more than a third of the deaths from COVID-19. This has put a spotlight on the region’s inability to curb the coronavirus or deal with the economic hardship. Experts say per capita income in Latin America will take longer than any other region to return to pre-pandemic levels.

The economic climb back, however, will require more than money. Outside creditors have put the region on notice that any aid to lift livelihoods must also lift financial integrity in government. Corruption cannot remain the norm.

In June, for example, Guatemala received $594 million from the International Monetary Fund for emergency assistance – but only after the country’s leaders agreed to use the money “effectively, transparently, and through reinforced governance mechanisms.” Guatemala is not alone. So far this year, the IMF has disbursed $17 billion to Africa, or more than 10 times than usual. The aid comes with a string attached requiring transparency in spending the money.

A similar amount of funding has gone to 14 Middle East nations but only after assurances that they fight corruption. In all, the IMF has provided about $100 billion of emergency funds to more than 80 countries to help them cope with the pandemic’s fallout.

As one of the world’s most corrupt countries, Guatemala is a good case for outside pressure. From 2006 to 2019, it was a global example in how to fight corruption. An activist attorney general and a United Nations-backed commission against impunity were able to oust a corrupt president and dismantle some 60 criminal structures. But the effort fell apart when a new president, Jimmy Morales, came under investigation himself. Last year he eliminated the commission and forced the attorney general, Thelma Aldana, into exile.

Now a rise in corruption there has irked the Trump administration, which had largely ignored President Morales’ takedown of the anti-graft efforts. Last month, it took action against the vice president of the country’s Congress and a former congresswoman by suspending their access to the United States. The two political figures had “undermined the rule of law in Guatemala,” said U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo.

“These designations reaffirm the commitment of the United States to combating corruption in Guatemala. We stand with the Guatemalan people in this fight,” said Mr. Pompeo’s statement.

The pandemic has worsened corruption in many countries, especially through embezzlement of money aimed at fighting the virus and restoring economic health. But big creditors like the IMF and aid-giving nations like the U.S. can step up and tie their money to curbing graft. Honesty in governance contributes to curing COVID-19 and its impact as much as lockdowns, vaccines, and financial aid.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

To ‘live together in unity’

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 1 Min. )

There’s a spiritual basis for unity that empowers each and every one of us to move forward with kindness, hope, and a growing grasp of a deeper and indestructible, divine harmony.

To ‘live together in unity’

“How good and pleasant it is when God’s people live together in unity!”

– Psalms 133:1, New International Version

Jesus’ prayer for all his brethren:

Father, that they may be one,

Echoes down through all the ages,

Nor prayed he for these alone

But for all, that through all time

God’s will be done.

One the Mind and Life of all things,

For we live in God alone;

One the Love whose ever-presence

Blesses all and injures none.

Safe within this Love we find all

being one.

Day by day the understanding

Of our oneness shall increase,

Till among all men and nations

Warfare shall forever cease,

So God’s children all shall dwell

in joy and peace.

– Violet Hay, “Christian Science Hymnal,” No. 157, © CSBD

[We are all children of] “...one Father with His universal family, held in the gospel of Love.”

– Mary Baker Eddy, “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” p. 577

Some more great ideas! To read or listen to an article in the weekly Christian Science Sentinel on establishing peace in ourselves and the world titled “Christian diplomacy,” please click through to www.JSH-Online.com. There is no paywall for this content.

A message of love

Welcome to the monkey house

A look ahead

Thanks for joining us. Come back tomorrow for a little gender-bending blues: Why the electric guitar isn’t just for men anymore.