- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- Trump’s final days: A transition unlike any other in U.S. history

- Destination 2021: What we’ll do differently next year

- Poor countries avert worst of pandemic, but not its economic fallout

- In tourist-free Bethlehem, a tranquil Christmas focused on family

- The other 2020: 274 ways the world got better this year

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

A better 2021

Mark Sappenfield

Mark Sappenfield

Yesterday morning, I received a holiday card. “Let’s never do that again,” it read. The sentiment is understandable. This year has been one of tribulation. But this week I also came across The Economist magazine’s “country of the year,” which looks at where things went right.

Among the honorable mentions: Taiwan and New Zealand, for showing that good government and the pandemic were not mutually exclusive. Bolivia, for finding a peaceful presidential transition amid unrest. Even the United States, where the judiciary universally rejected partisanship to thwart an attempt to overthrow the presidential election.

The winner: Malawi, the only country where democracy and respect for human rights improved in 2020, according to Freedom House. Malawi also saw its judges “turn down suitcases of bribes” and annul a blatantly corrupt election, leading to a legitimately elected president.

But there’s a broader lesson here. Today, the Monitor Daily is running a summary of the 274 points of progress we chronicled this year. They paint a picture of a different 2020. Even in the bleakest years, the march forward never stops. And the seed of a better 2021 begins with acknowledging the progress made in 2020 and building on it.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Trump’s final days: A transition unlike any other in U.S. history

This has been a presidential transition unlike any other in United States history. President Trump’s actions show his determination to bend reality to his advantage.

Twenty-eight days before Inauguration Day, a presidency like no other has morphed into a transition like no other.

President Donald Trump still insists he won the Nov. 3 election, and has been meeting with conspiracy theorists and other allies promoting unrealistic and in some cases seditious ideas aimed at overturning the results. On Wednesday, he vetoed the National Defense Authorization Act – which had passed the House and Senate with veto-proof majorities. Yesterday, after announcing 20 pardons and commutations, he upended a bipartisan congressional agreement on pandemic relief payments, demanding in a tweeted video that they be raised from $600 a person to $2,000.

For Mr. Trump, the last-minute maneuver reflected not only a populist view of government spending but also a love of the spotlight. He used the opportunity to insist – again – that he might be headed for a second term.

Beneath the daily turmoil lurks the perpetual question: Does Mr. Trump really think the election was stolen from him, despite the lack of concrete evidence? Or is he simply keeping his supporters fired up so he can possibly run for president again in 2024?

“He’s livid,” says a source close to Mr. Trump’s orbit. “In his head, everyone was out to get him. And it’s the media coverage that’s eating at him more than anything.”

Trump’s final days: A transition unlike any other in U.S. history

Twenty-eight days before Inauguration Day, a presidency like no other has morphed into a transition like no other – at once eye-poppingly dramatic and utterly predictable.

President Donald Trump still insists he won the Nov. 3 election, and has been meeting with conspiracy theorists, controversial former aides, and congressional allies promoting unrealistic and in some cases seditious ideas aimed at overturning the results. In other ways he is also behaving like a more typical American president about to leave office, with the announcement on Tuesday evening of 20 pardons and commutations – albeit some of them highly controversial.

“It’s absolutely business as usual,” says Trump biographer Gwenda Blair. “Refusing to acknowledge reality, bending reality – he’s done it for 50 years. Why would he change now?”

Within minutes of issuing the clemency memo, President Trump also upended a hard-fought, bipartisan congressional agreement on pandemic relief payments, demanding in a tweeted video that they be raised from $600 a person to $2,000. The “or else” – a presidential veto – was implied. Wednesday morning, congressional leaders scrambled to save the deal, which includes government funding that would prevent a shutdown later this month.

For Mr. Trump, the last-minute maneuver reflected not only a populist view of government spending that runs counter to the stance of GOP congressional leaders but also a love of the spotlight. He used the opportunity to insist – yet again – that he might be headed for a second term, asking Congress to “send me a suitable bill, or else the next administration will have to deliver a COVID relief package, and maybe that administration will be me.”

Today, he followed up by vetoing the National Defense Authorization Act – funding the military – which had passed the House and Senate with veto-proof majorities.

Beneath the daily turmoil lurks the perpetual question: What does Mr. Trump actually believe? Does he really think the election was stolen from him, despite the lack of any concrete evidence? Or does he know he lost, and is simply keeping his supporters fired up so he can hold sway over the GOP and possibly run for president again in 2024?

“He’s livid,” says a source close to Mr. Trump’s orbit. “In his head, everyone was out to get him. And it’s the media coverage that’s eating at him more than anything.”

The president, according to this source, has seen a post-election survey by his pollster, McLaughlin & Associates, that reportedly shows he would have won reelection if more voters had been aware of the foreign business dealings of President-elect Joe Biden’s son Hunter.

Mr. Trump has blamed his attorney general, William Barr, for keeping quiet about a federal probe into Hunter Biden’s financial dealings during the campaign. At his final news conference Monday, Attorney General Barr refused to support the appointment of a special counsel to investigate the younger Mr. Biden. He also declined to back the federal seizure of voting machines, an effort some Trump allies have been pushing for arguing it would show evidence of manipulation. Mr. Barr, once a strong defender of Mr. Trump, announced his resignation last week.

As the endgame has neared, Mr. Trump has spent time with fringe figures, including former campaign lawyer Sidney Powell, who has outlined extensive conspiracy theories, and former National Security Adviser Michael Flynn, who has suggested seizing voting machines and deploying troops to key states to force a rerun of the election.

On Monday, Mr. Trump met with sympathetic members of Congress, including GOP Rep.-elect Marjorie Taylor Greene of Georgia, who has expressed support for the QAnon conspiracy theory. Ms. Greene says there’s growing support in the House and Senate to challenge Mr. Biden’s 306-232 victory in the Electoral College when both chambers meet on Jan. 6.

All of this year’s post-election machinations are a far cry from the usual. But then, Mr. Trump is “unprecedented in American history in so many ways,” says Robert C. Smith, a professor of political science at San Francisco State University.

Still, while the turmoil of 2020 may be unprecedented in the modern era, historians say it isn’t the most tumultuous election this nation has seen.

“We started out on the wee hours of election night with comparisons to 1960 and 2000, but, unfortunately, they proved too tame,” writes presidential historian David Pietrusza in an email. “So we have traveled on to 1876 and the ultra-contentious Hayes-Tilden matchup.”

Then, Democrat Samuel Tilden led in the popular vote over Republican Rutherford Hayes, but the electoral votes from several states were disputed. Lacking a constitutional remedy for the impasse, Congress convened a commission. In the so-called compromise of 1877, Mr. Hayes became president and Democrats effectively won the end of Reconstruction.

“Our Constitution does not actually say what should happen if there are disputes about who carried a particular state,” says Eric Foner, emeritus professor of history at Columbia University. “It lays out what happens if nobody wins the majority of the Electoral College: It goes to the House. But that assumes that everyone agrees on the Electoral College results. If people don’t, then you’re sort of in uncharted waters.”

Today, the Electoral College has already voted for Mr. Biden, and Mr. Trump’s effort to overturn the results in several states seems quixotic at best. When the joint session of Congress convenes on Jan. 6 to formally count the votes of the Electoral College, at least one member each from the House and Senate is expected to raise objections to Mr. Biden’s victory. But there’s no chance the effort to overturn the results goes anywhere.

So why would Mr. Trump encourage such an effort? He wants to “exhaust every avenue” and if he’s going down, go down fighting, says one Trump watcher. That never-say-die approach is part of his brand and boosts him as a post-presidential “influencer” and party leader, if not a candidate for 2024.

“What’s Trump after? God knows,” says Professor Foner, who notes “he has certainly picked up a lot of money” in political contributions during this post-election period. In addition, “he’s forced most Republicans to line up behind him, which reinforced his status as leader of the party.”

Another election that may hold some currency for Mr. Trump is the contest of 1824. Andrew Jackson won a plurality of both the popular and electoral votes, but when the election was thrown into the House, John Quincy Adams emerged victorious.

“Like Trump today, Jackson felt the election was illegitimate and corrupt, but he did not quite have the media outlets that Trump does to explain all this,” says Professor Foner.

Four years later, in a rematch, Jackson beat President Adams. A portrait of Jackson hangs on the wall of Mr. Trump’s Oval Office.

With a month still to go, the Trump-Biden transition has observers – including White House aides – on the edge of their seats. What else might Mr. Trump do, either domestically or in foreign policy, that could tie Mr. Biden’s hands? Will he pardon himself or family members? What will he do on Inauguration Day?

The pardons and commutations announced Tuesday evening caused an uproar, particularly those of three disgraced former members of Congress and four military contractors convicted of war crimes in Iraq. But Mr. Trump is still president, and by all accounts, enjoys flexing the executive power that comes with the office.

Whether a future Congress will try to rein in those powers is a discussion for another day. But for the next 28 days, it’s his to use.

A deeper look

Destination 2021: What we’ll do differently next year

Monitor staffers weigh in on lessons from a year in isolation – and what they yearn to do most coming out of the pandemic.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 21 Min. )

-

By Monitor staffers

As 2020 shudders to an end, many of us will be eager to move on, hoping that 2021 shows a path out of a pandemic that has upended our way of life. In that spirit, we asked Monitor writers and editors, near and far, to reflect on what COVID-19 has taken away and what, paradoxically, it has given us. It’s a journey into what we yearn to experience again and what we have come to appreciate most, to the point where we may no longer feel the urge to revert to old ways when the risk recedes.

For some writers, it comes down to habitual pleasures denied, to friendships and family ties put on hold. For others, the pandemic has forced a deeper rethink of what is and isn’t important, from communal gatherings to ritual greetings. Whether these individual aspirations and insights are profound or poignant, all are deeply human impulses grounded in the sense of disruption that an unusual year in world history has wrought. We share them with you as glimpses of what, we hope, will be a brighter future. – Simon Montlake / Staff writer

Destination 2021: What we’ll do differently next year

As 2020 shudders to an end, many of us will be eager to move on, hoping that 2021 shows a path out of a pandemic that has upended our way of life. In that spirit, we asked Monitor writers and editors, near and far, to reflect on what COVID-19 has taken away and what, paradoxically, it has given us. It’s a journey into what we yearn to experience again and what we have come to appreciate most, to the point where we may no longer feel the urge to revert to old ways when the risk recedes.

For some writers, it comes down to habitual pleasures denied, to friendships and family ties put on hold. For others, the pandemic has forced a deeper rethink of what is and isn’t important, from communal gatherings to ritual greetings. Whether these individual aspirations and insights are profound or poignant, all are deeply human impulses grounded in the sense of disruption that an unusual year in world history has wrought. We share them with you as glimpses of what, we hope, will be a brighter future.

– Simon Montlake / Staff writer

Parental nonguidance suggested

Northampton, Mass.

I look forward to significantly lowering my standards when it comes to parenting. Actually, I plan to toss out the verb “parenting” altogether – that anxiety-laden transformation of a noun into an activity that comes with ideologies, debates, comparisons, success markers. During the pandemic, intensive “family-ing” has pushed intensive parenting out the window at our house.

And I think that’s good.

Intensive parents know – because we have read all about it, in our quest to be the best caregivers possible – that pouring unprecedented time, resources, and attention into our children may not have been doing them (or us) many favors. It is relentless, exhausting, and, according to many experts, ill prepares children for realities ranging from boredom to adulthood to laundry.

The pandemic has shifted my focus. My girls do more chores, and they know that I must actually work – and occasionally zone out to “The Home Edit.” They know they can amuse themselves. They know they are part of a family and that means responsibility as well as security. They know they are loved beyond words. After the pandemic I want to keep this approach, with no stressing about extracurriculars, play dates, missing a school day, or “preparing for the future.” I want to stay committed to family-ing.

– Stephanie Hanes / Correspondent

Harmonic convergence

Toronto

It turns out the activity that I loved the most in Toronto is probably the worst thing you should do in a pandemic – crowd together in a windowless room at the back of a pub, belting out everything from David Bowie to the Beatles. Choir!Choir!Choir!, a weekly drop-in choral group started by two Canadians in 2011, drew me in from the first session I attended in the summer of 2018. It was probably my weakness for “Get Lucky” by Daft Punk.

I hardly ever socialized – I came and sang and took the subway home – but the sense of community, of creating harmony with perfect strangers, left me feeling more connected to Toronto than any banter on the street ever did. When I return, it will be with a keener sense of what that experience really means. Heck, I might even try to strike up a conversation with an alto.

– Sara Llana Miller / Staff writer

Driving Mr. Collins

Hamilton, Mass.

Maybe you’re not a car person. The crunch of tires on a gravel drive? The harmonics of an aftermarket tailpipe? Nah, you sputter. Driving’s a drag, conveyance by appliance.

Joy ride? That’s just a guilt trip with a combustion engine.

Let me drop you off right here.

First of all, what’s a car but a pod of imperturbability, pandemic isolation in motion?

I love the driving that I can still sneak in during the coronavirus: the quick spin – top down, heat on, mask up, scattering leaves through the twisties close to home. There’s driving I miss: the road trip, planned or serendipitous, not worrying about whether the rest stops are quarantine clean.

Then there’s the driving I did pre-pandemic: stuck in a ruby river of brake lights, grateful – not smug – in a hybrid, but still grinding through a commute to get to an office and break out the same laptop I’d been using to do the same work at home. (Thanks, Zoom. You even sound like a word for proper driving.)

Regular road-roving is an act of privilege. Trains can be better. Bikes work. Car guy here; just get me started. The best days of driving are just around the bend.

– Clay Collins / Director of editorial innovation

Croissants and conversation

Paris

The hardwood counter at Chez Mémé is always cluttered. Emptied coffee cups pile up. Croissant crumbs litter plates. Neighbors-turned-friends stand elbow to elbow, chatting about the latest political gaffe or the incessantly cloudy Parisian skies.

I was starting to finally feel a part of France’s cafe culture. Marie, the owner, knew my name. She knew I’d order a café allongé and eventually cave for a flaky pain au chocolat, my laptop open, pretending to look like I was working on something important.

Then the pandemic hit. Cafes and restaurants closed. Now, the four white walls of my living room – my de facto workspace – are enough to make my eyes bleed. The silence is deafening. I miss the clanking dishes as Marie rushes around the cafe and the assortment of characters I meet – Richard with his belly laughs, Laetitia always lounging against the counter, George studiously reading the free copy of Le Parisien.

It’s hard to find community in a city of 2 million people. Sometimes, now, I’ll see Marie out for a walk in the neighborhood, both of us calling out “bonjour,” with knowing smiles of what we’re missing.

– Colette Davidson / Correspondent

Hollywood in the driveway

Hingham, Mass.

I live at the end of a street where you can pass the salt between houses. We watch out for each other, take newcomers to dinner, share garden vegetables. Some of us used to hit the movies together – but then theaters closed. So we built our own – and laid the foundation for a deeper connection in our already closely woven neighborhood.

On the surface, it looks like this: We go to Peter and Kathy’s driveway, where PVC pipe and fabric form a screen over the garage door. We bring our own popcorn and seating. Atmospherics include a full moon, neighbors strolling by, the occasional coyote howl.

But look deeper. Movie selections are chosen by a democratic vote. After the showing, we discuss what we saw – the influence, likely, of the teachers in the neighborhood. As the final credits roll, we smile, bid each other warm good nights, and lug our chairs home, utterly satisfied.

It’s pandemic-driven viewing. I hope it lasts long beyond this moment.

– Amelia Newcomb / Managing editor

Neon fonts and hiking jaunts

Laguna Beach, Calif.

Like Disneyland’s old Adventure Thru Inner Space, in which riders shrunk to less than the size of an atom while their surroundings exploded in size, my reduced pandemic orbit has somehow expanded my experience. I don’t feel reduced. I feel enabled. And I like it.

My planned weekslong trip to Asia in 2021 has evaporated – a 20-hour flight cozied up with hundreds of passengers is now unappetizingly inconceivable. In my new pandemic horizons, I’ve put 10,000 miles on my car in cross-country trips I might otherwise have missed: permission and time granted to follow unexpected byways and stop and stare at the neon font on an abandoned midcentury motel.

My perfect – triple-movie – weekend is over. But I’ve doubled my viewing pleasure, streaming in the comfort of a chair that isn’t a public health menace.

Jaw-clenching places-to-go-and-people-to-meet schedules and commutes ... gone. And with no other place – or pace – to go, I’m hiking. Averaging 30 miles of deep thought a week, I regularly choke up at rosy California sunsets, exquisite blooms, and the fleeting gleam in the eye of a roadrunner crossing my path.

– Clara Germani / Staff editor

A globe-trotter revels in nesting

Remigny, France

I have led a peripatetic life as a foreign correspondent, and the coronavirus pandemic, because of the travel restrictions it imposed, was always going to cramp my style. But when COVID-19 put me in the hospital last March, and nearly took my life, I was truly grounded.

As soon as I was well enough to travel, we left Paris and sought refuge in my wife’s family home. I have been here ever since, in a secluded Burgundy village (decimated by plague in 1751 but untouched by COVID-19), learning to appreciate the unexpected pleasures of a long pause and the value of a sense of place.

The house has been in Edith’s family for many generations. Each has lent the home its patina of furniture and decoration; now we are doing the same. It is imbued with the rhythms of continuity and security that I had shunned for most of my career, but now find deeply reassuring.

I had feared I would feel trapped in my rural retreat. Instead I am restored, ready to roam again when the opportunity returns.

– Peter Ford / International news editor

The church universal

Swampscott, Mass.

For people of faith like myself, the pandemic initially seemed to threaten our sense of church. After all, what’s a congregation that can’t congregate? But going online to worship and minister to one another has actually expanded and enhanced who we are.

Being together online enables sharing of faith stories and growing alongside people from places and cultures we’d never engage otherwise. Church not only draws more people now. It’s also more interesting, exciting, and challenging than it used to be. We will never go back to gathering as “just us.” After in-person gatherings resume, we’ll keep allowing people to engage remotely by feeling loved, making meaningful commitments, and taking risks that are the grist of spiritual transformation. Talking heads on screens will be a lasting presence not only in worship but also in small groups and mission activities. Powered by technology and the tireless Holy Spirit, we see the ancient vision of a church universal materializing.

– G. Jeffrey MacDonald / Religion correspondent

Intimacy at a great distance

Ipswich, Mass.

It seemed a poor substitute, but it was the only option: The memorial service for a longtime friend would have to be held via teleconference rather than in person in Portland, Maine. But when we logged in, it soon became obvious that something unexpected and special was happening. You can attend a Zoom meeting from anywhere, and our friend had a wide circle of friends, many of whom were now encountering one another for the first time. Participants from as far away as Honolulu and London were present.

On Zoom, you look directly into the eyes of every speaker. You’re virtually seated right across from everyone attending. We were all equals: no in-person vs. on-video guests. Some expressed surprise to discover the breadth of our friend’s network.

The experience changed my mind: At first, a Zoom memorial seemed too easy, even undignified. Now I’m persuaded that the reach and very nature of such a service (and everyone’s increasing familiarity with the medium) can provide remarkable intimacy, connection, and solace – even discovery. A smaller, in-person group would have been good. But as it was, many more of us met face-to-face and heart-to-heart over the internet.

– Owen Thomas / The Home Forum editor

Going with the crowd

Hingham, Mass.

Remember crowds? I do. I remember them more fondly than I might have guessed if you’d asked me a year ago. And I don’t mean just intentional crowds, like inside the arena where I last saw that spectacular Radiohead show, or that incredible Boston Celtics game. I mean ad hoc crowds, accidental crowds, inevitable but unorganized crowds on subway platforms, in department stores during the holidays, among the human tides that swamp the streets after big events – all of us talking, knocking shoulders, window-shopping for an available restaurant table.

I remember how crowds sounded. I remember how crowds felt.

And, sure, I know life won’t be re-crowded this winter. But come fall, say? Come next Thanksgiving? Crowds just might be back. And when they are, well, you won’t need to wonder where to find me.

I’ll be adding to their number.

– Michael S. Hopkins / Correspondent

A wedding anniversary among the masses

Holliston, Mass.

As spring burst forth this year, my wife and I dearly missed celebrating our wedding anniversary with a jaunt to New York City, something we try to do annually. With careful planning we can jam three Broadway shows, an intriguing museum exhibition, and a morning pilgrimage to Central Park to spot migrating birds into three days (and two expensive hotel nights).

We’re looking forward to when we’ll again be able to cram onto an Amtrak train, emerge into the pandemonium of Grand Central Terminal, transfer to a packed subway car, and huddle together in a crowded cafe for an afternoon treat. We’ll cap the day by wading through the waves of humanity at Times Square, marveling at their sheer enormity and diversity.

We may be just two more anonymous out-of-towners, but for a short while we belong to the city. We breathe its air and become part of its throng, the thousands of individuals who en masse tell a vast and varied story.

– Greg Lamb / Correspondent

Book marked

Washington

As a child, I was a voracious reader. At a certain age, my parents bought a lamp to clip onto my bed frame and said I could read as late as I liked, but they were soon forced to set a reading curfew. With that memory in mind, I made a New Year’s resolution for 2020: read 12 fiction books, one per month. I consume political news articles for hours each day, but I’ve stopped reading for fun over the past few years.

That’s because as a 27-year-old in a big city, I never considered reading to be an ideal way to spend my Friday nights. Instead, when a friend would text me to get dinner, or suggest that we stop by another friend’s apartment, I’d always say yes. By the end of March, I was 0 for 3 in my book resolution.

But then COVID-19 upended our lives. Soon I had no choice but to spend my Friday evenings chipping away at the stack of overdue library books on my nightstand. I remembered how wonderful it was to resist turning out the lights as a book’s plot unfolded.

One recent Friday, I finished book No. 13.

– Story Hinckley / Staff writer

Opening Studio K

Milton, Mass.

After working out for months in my living room and then the kitchen when the local pool closed, something had to change. I needed to create a space for myself instead of exercising in shared spaces. So I turned a dark corner of the basement into my private gym on a DIY budget. I painted the drywall bright yellow, bought interlocking floor mats, strung up fairy lights, and mounted a smart TV to stream workouts. My family calls it “Studio K.”

I also convinced four friends who live across the country to sign up for the same workout program so we could train “together.” I used to get up at 5 a.m., head to the pool, hustle home to change, and then rush to catch an 8 a.m. train. But now I have no commute and can work out with friends virtually anytime. I love Studio K so much it will take effort to get back to the pool when it reopens.

– Kendra Nordin Beato / Staff writer

The pub as a community hearth

Berlin

Round the corner and up the hill toward the water tower sits a German pub that has been owned by the same family for more than a century. Opened the year before World War I began, amid a landscape still populated with windmills, the pub now nestles inside one of Berlin’s most densely packed neighborhoods.

I often wonder, parked inside its wood-paneled walls, how its pork knuckle has evolved since 1913. I’d like to think it’s the same dish today. The pub’s few drinks on tap all pair perfectly with the Wiener schnitzel, its breaded crust fried golden-brown. My wallet is only €8 lighter for the experience, and it’s the tastiest I’ve had in Germany. Usually weak-kneed for greasy pub fries, I always opt for the fried sliced-potato version.

Tables are nearly impossible to reserve after sundown – regulars are given top priority – but the coronavirus delivered both a blessing (for us) and a curse (for them) in their hastily arranged sidewalk tent. It was nearly always empty, and open to walk-ins like me. Pre-pandemic, I’d been wishing my way toward a spot at the regulars’ table, perched by the main window. Realistically, I am a couple of decades away from being shown to that coveted spot.

– Lenora Chu / Special correspondent

Tea for two, and two for tea

Pasadena, Calif.

When I was growing up, my parents regularly invited people to tea on Sunday afternoons. Nothing fancy, just a nice pot of Earl Grey with a homemade spice cake and a view out the sliding glass doors to our garden in suburban Washington, D.C.

It was usually one or two guests, rarely more than that, since my parents wanted a meaningful visit. The sessions were a chance to get to know newcomers at church, reconnect with old friends, or have a neighbor over. I remember these afternoons as wonderfully intimate and relaxed, and carried them into my adult life.

My husband and I planned to start these up when we moved to the Los Angeles area in 2019. But just when we were ready to brew the tea and make new friends, the pandemic hit. For a short while, a neighbor organized regular “check-ins” in the middle of the street, and so we at least recognize people and give a friendly wave on our walks.

But it is as if we are frozen in time, not fully moved in, not really connected. It’s nothing that a little spice cake won’t fix, with views to our birds of paradise instead of cherry blossoms.

– Francine Kiefer / Staff writer

Virtues of subway straps

Washington

I may be crazy, but I actually look forward to riding the Metro again. Yes, Washington’s subway system has its shortcomings. Before the pandemic, breakdowns could strand riders for an hour or more. And forget 6 feet of distancing. In rush hour, 6 inches felt like a luxury. Working at home truly has had its advantages.

Yet cities promise to remain vital seedbeds of culture, politics, and business – and mass transit is a functional mainstay. All the more so in an era of global warming.

For now, the pandemic has eviscerated ridership and forced steep cuts in big-city transit budgets. Longer term, Zoom chats will have their enduring place in a low-emission future. But I’m eager to ride those rails again – to be part of the varied masses on board, to struggle to keep my balance amid the hum of the electric acceleration.

– Mark Trumbull / Economics editor

Street food with street cred

Mexico City

A black-bean tlacoyo, smothered in slimy nopales, sour cotija cheese, spicy green salsa, raw onions, and cilantro: This was my go-to order when I craved street food pre-pandemic. I’d walk around the corner to two umbrella-shaded women working a steaming griddle with precision and speed. I’d call out my order over a scrum of other hungry customers, and if my timing was right, I’d score a dining spot on an upside-down bucket, where I’d devour this blue-corn delicacy off a plastic-wrapped plate.

It’s a ritual I’ve missed terribly during the pandemic. I was just getting to the point where I felt comfortable navigating the unspoken rules of ordering street food – after all, there’s no clear line, no menus, and half of the ingredients have names in Nahuatl, a pre-Hispanic language. Dining curbside was such an important part of integrating into my adopted home. So much of life is lived outside and among neighbors in Mexico City, and losing that, even temporarily, has made me feel untethered from my community. I’m eager to get back to shared meals with strangers and a feeling of connection.

– Whitney Eulich / Special correspondent

Vanishing greetings

Amman, Jordan

When I see a friend, there is only one true way to say hello: I clasp his right hand, pull in for a one-armed hug around the back, lean my right cheek next to his, and air kiss. I then switch sides and lean onto his left cheek and plant another two kisses. If I really miss him? An extra three or four.

This is the greeting between male friends and relatives in my adopted home in Jordan and many parts of the Arab world. It is a sign of brotherly love, respect, friendship, a bond that spoke to me and led me to embrace it. In societies where body language is more important than words, much is said in a kiss-greet. I can squeeze a little harder on the hug, press my cheek to show how much I value our friendship. If his cheek does not touch mine? Then it’s probably not genuine.

Since COVID-19 hit the region, we now greet each other as instructed by government televised public service announcements: We place our hand over our chest and bow in respect from afar. For me, the physical affection and connection is lost. Yet in an era when we’re trying to care for those around us, that is in its own way a gesture of love.

– Taylor Luck / Special correspondent

Learning a new language in isolation

New York

A language school had a discount – and I had time – so I signed up for online Arabic classes. Every Thursday night since June, I follow along in pencil as my Arabic script flows right to left. The learning is slow, but our teacher is patient; someday I hope to report in Arabic. My current vocabulary may resemble a toddler’s (“He is a tall baker”), but it’s already unlocked simple joys beyond my laptop screen.

I live in New York City near “Little Egypt,” an area I’ve recently rediscovered with fresh eyes. As I walk the strip of hookah bars and halal eateries, the mystery of storefront signs has begun to melt away. Starved for connection behind a mask, I introduce myself with my favorite new word: tasharrafna (nice to meet you). I’ve learned which grocers have copies of free Arabic-language newspapers, and I visit a store that sells me kindergarten texts. “Come again when you finish,” says Sahar, an amused shopkeeper, as I exit with an alphabet workbook. I’ll be back soon.

– Sarah Matusek / Staff writer

A new slant on light

Lexington, Mass.

What I am appreciating more than I did before is light. Being forced to stay in one place for months has taught me to be a connoisseur of light, and I’m learning to savor all its permutations. With no commute, I now have time to notice the way the sun moves across the sky outside my home office windows – high and fierce in the summer and low and slanting in the winter.

I walk the same route almost every day, and I can appreciate the nuances of the sunlight hitting the bark on the trees, the filtering of morning light through the leaves, the subtle changes of the seasons. I understand better why painters return again and again to the same location, trying to capture the quality of the light. Before the pandemic, I was moving too quickly to notice how light changes everything about the day, and my mood. I expect this awareness to last beyond the months of quarantine. The other thing I have realized: My windows desperately need cleaning!

– April Austin / Weekly deputy editor and books editor

Crunch time

Amherst, Mass.

When this is over, I’d like to have the house to myself. I’ll bid my wife and two young children a wonderful time at their grandparents, the museum, or wherever they want to go as long as it’s elsewhere, and the moment they’re out of sight, I’ll open a family-size bag of Tostitos.

Then, at long last, there will be silence. Except for the crunching.

I’ll put on a film whose title is a single word and a Roman numeral. Something like “Stab II” or “Snakecano VI.” Definitely not “Caillou’s Holiday Movie.” After that, I’ll think long thoughts, the kind of profound, uninterrupted cogitation available to Hobbes, Spinoza, Kant, and all those other eminent thinkers who never married or had kids.

After a few hours, I’ll feel something I haven’t felt in ages: I’ll miss my family. When they return, we’ll embrace, and I’ll ask how their day was without already knowing the answer. Then I’ll tell them about all the philosophical problems I solved, and how I have no idea what happened to the Tostitos.

– Eoin O’Carroll / Science writer

The sounds of soccer

London

Oh how I miss my Saturday ritual, watching my beloved Arsenal Football Club from the stands. (It’s more plush seating in the stadium these days, with the bleachers gone, but the sentiment remains.) It’s not quite seeing your immediate family, but it is just as profound, magical, and full of community. I look forward to reinstating my weekend pilgrimage that involves wrapping myself in a red-and-white scarf, walking through the packed streets of North London, smelling the scent of burgers you wouldn’t dare touch, and hearing the cacophony of 60,000 people as kickoff approaches.

Watching football on television isn’t quite the same. Football has been an empty shell without its crowds. I’ll be doing what I usually do, but with more zest than before: screaming, shouting, and chanting in unison with thousands displaying the same colors. We become one, speaking a common language of desperation in loss or utter joy in victory, holding a stranger in our arms when a goal is scored, and embracing the unscripted drama that unfolds on a patch of grass under the floodlights.

– Shafi Musaddique / Correspondent

Discovering what’s already there

Brighton, Mass.

The realization set in slowly, the way the darkness tiptoes into the corners of a room. We wouldn’t be celebrating our 20th wedding anniversary in Puerto Rico, after all.

It could have been disappointing. Instead it just – was.

Here we were. Together. And that would be OK.

As our expectations narrowed, something magical happened. We started to see our home and our neighborhood through new eyes. Isolated from many of the people we care about, we got to know our avian neighbors, not just by species, but as individuals. We discovered a hidden pond and a tiny meadow, both just a 10-minute stroll away.

The irony of course is that these adventures had been waiting for us all along. We’d simply never looked because we’d always been on our way somewhere else.

Our surprise at just how much we’ve overlooked in our own neighborhood has recently given way to a new resolve to focus on the present, the here, the now. And, of course, each other.

When the post-pandemic comes and we’re able to gather and travel freely once again, that’s something we’d do well to remember.

– Noelle Swan / Weekly edition editor

My homemade mobile home

Boston

I didn’t plan on buying a car.

Like many urban millennials, I’d made it through most of my 20s eschewing car ownership in favor of public transit, ride-sharing apps, and carpooling with friends. Relying on shared resources meant I saved money and occasionally could splurge on long-distance travel – flights, hotels, and rental cars.

But with the world changing in perhaps irrevocable ways, I reassessed. A car of my own offered enticing freedom. So in May, I bought a used Toyota RAV4 – in purple, my favorite color. It’s the first car I’ve ever owned, but it’s much more than that. It’s a refuge, a mobile home-away-from-home.

With the help of plywood, a saw, and some screws, I transformed my car into a bedroom and kitchen on wheels. Stored beneath a memory foam bed, camping and hiking gear makes it a veritable adventure mobile.

During the pandemic, my car camper has helped me connect with loved ones from a safe distance. I’ve slept in my parents’ yard and made hot drinks for friends at trailheads. But it also expands my possibilities for adventure after the pandemic. Perhaps I can satisfy my wanderlust as a car owner, no flights or hotels necessary.

– Eva Botkin-Kowacki / Science writer

That first day of kindergarten

Needham, Mass.

Parenting is full of firsts – first smile, first step, first word – and parenting during a global pandemic is no different. It’s brought us another set of firsts, albeit many of them less celebratory: first remote school day, first masked foray.

But recent months have also kindled deep gratitude for the parenting adventures we’ve already had and a heartfelt expectation for those long overdue. When the masks come off and social distancing ceases, I’ll be excitedly waving as my daughter boards the school bus with her neighborhood friends for her first day of kindergarten, proudly smiling as she snakes down the waterslide at the community pool, and enthusiastically cheering her on during her first soccer game. I may even coach it!

The arrival of these milestones will be all the more joyous, though, because of the mountains we have climbed to get there – and they’ll be all the more special because of the grace, fortitude, and compassion we’ve learned along the way.

– Casey Fedde / Chief copy editor

Oceans away

New York

I have been living away from home since I was 17, when I left to study abroad and, later, to work. But it wasn’t until the pandemic that I realized how much I had taken air travel for granted, or what it really meant to be living thousands of miles away.

I used to try to make it back to Brunei at least once a year. It’s now been over a year since I’ve seen my parents in person. I miss being able to travel freely without worrying about health and quarantine. I miss sunsets on the plane – the brilliant vermilion rays casting shadows on the clouds to form otherworldly landscapes in the sky. And I miss my husband, who is in London, an ocean away.

We’ve adjusted to seeing each other through a screen for now. I call my parents more often. I am also more intentional about staying connected with friends in Asia. It is hard not knowing when I can be with my loved ones again. But I’m also reminded home isn’t where I am; it is where my heart is.

– Connie Foong / Staff writer

Global report

Poor countries avert worst of pandemic, but not its economic fallout

Most developing countries have weathered COVID-19 better than expected, health-wise. But the economic impact has been severe, and citizens are hoping for answers.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

-

Taylor Luck Special Correspondent

-

Shola Lawal Special Correspondent

-

Shafi Musaddique Correspondent

When COVID-19 began spreading worldwide back in March, experts warned that poor countries in Africa and Asia would bear the brunt of the pandemic. In fact, while the coronavirus has scoured Europe and North America, death rates in the developing countries have generally been low.

But they have not escaped the economic fallout, as the global economy has shrunk by nearly 5% this year. The economic slowdown and pandemic-induced lockdowns have thrown millions of the most vulnerable out of work; the World Bank estimates that as many as 115 million people have fallen into absolute poverty because of COVID-19.

And the problem is compounded by a slump in remittances from migrant workers who had gone to the Persian Gulf, to America, or to Europe, where the pandemic has reduced the demand for labor. Remittances totaled $550 billion in 2019, three times as much as official foreign aid budgets. For many families this year, those monthly checks wired by distant relatives have dried up.

Poor countries avert worst of pandemic, but not its economic fallout

When his furlough notice came in March, Kingsley Chukwuemeka Udeoji wasn’t too surprised. Nigeria had announced a partial COVID-19 lockdown, and the private high school in north-central Niger state where he taught math was sending students home.

The timing was awkward: Mr. Udeoji’s wife had quit her marketing job and just given birth to their first child, a daughter named Tiffany. But he thought the shutdown would be short-lived, like the one during the 2014 Ebola outbreak in West Africa that Nigeria managed to keep at bay.

It was not to be. As Nigeria braced for a pandemic that many feared could sink its patchy health care system, the government kept prolonging the lockdown and Mr. Udeoji grew desperate as he spent down his savings. “The baby had to eat. Mother had to eat. I had to eat. It got too much,” he says.

Some 2,000 miles away, Hassan Ais, a factory owner in Mansoura, Egypt, was also flailing.

Sales of his beauty products had collapsed, and he had laid off all but one of his seven workers. Nobody had much money to spare for nonessentials like shampoo. But the economic hardship in the Nile delta wasn’t simply the result of Egypt’s lockdown. The source of the trouble lay farther away in the oil-rich Persian Gulf, where millions of Egyptian migrants ply their trades.

“There are entire villages here that rely on citizens working the Gulf to send money home,” says Mr. Ais. “With their salaries cut or them being let go, purchasing power suddenly is extremely limited.”

Nigeria and Egypt are examples of developing countries that averted runaway pandemics in 2020, to the relief of health officials, only to face economic crises due to social restrictions at home and an unprecedented global collapse in trade, travel, and capital flows. This includes remittances from migrants who funnel money from better-off nations to some of the poorest.

A shrinking economy

This year the IMF says the global economy is expected to have shrunk by 4.4%, nearly three times as much as in 2009, the height of the last financial crisis. And the proportion of countries simultaneously in recession is the highest in over a century; among major economies only China, where the virus was first detected, will post economic growth.

Back in March, when COVID-19 began spreading widely, experts warned that poor countries in Asia and Africa would bear the brunt of the disease. Instead, the pandemic has scoured rich countries in Europe and North America, while many in the developing world have recorded far fewer deaths per capita. In Nigeria, a nation of 200 million, the official death toll is 1,200. Vietnam has 96 million people; only 35 of them are reported to have died of COVID-19.

But that hasn’t spared developing countries from the economic shock of COVID-19. Far from it: The number of people living in extreme poverty – on less than $1.90 a day – is thought to have risen by as many as 115 million in 2020 after declining every year for more than two decades.

Not all developing countries have dodged the health bullet: India has recorded the second highest number of confirmed cases, behind the United States. And in Latin America, rampant COVID-19 outbreaks and haphazard governance have left a trail of death and economic ruin; the region’s economy is expected to shrink nearly twice as much as the world average.

“The places that are feeling the worst pain are seeing the worst of both worlds,” says Michael Wolf, a U.S.-based global economist at Deloitte, a business consultancy.

Even countries like Thailand and Vietnam that swiftly contained the pandemic suffered from a slump in tourism, a mainstay of their economies. “It wasn’t just about how well you were doing in terms of health outcomes, but what industries were concentrated within your borders,” says Mr. Wolf.

Rebounding in Nigeria

For Nigeria, that industry is oil, which accounts for nearly two-thirds of government income. In April, oil cargoes sat in Nigerian ports as China and other buyers suspended imports during the downturn.

By July, Mr. Udeoji was at his wits’ end. Local lockdowns had eased, but schools remained closed and the price of food had soared. Fitful government efforts to distribute food aid fell short amid accusations of corruption and hoarding.

One morning, his savings exhausted and his rent due, he turned to Twitter. “Survival has been difficult since school closure,” he tweeted, posting a photo of his family. “I need online private coaching opportunities or any job ... please help.”

Strangers responded, offering to make donations. Soon he had money to help pay the rent and buy supplies for his baby daughter.

In October, Nigeria reopened schools and Mr. Udeoji went back to work; he has started to save again. His wife is looking for a job. What worries him now is that the new uptick in coronavirus cases in Nigeria might lead the authorities to impose another lockdown.

“We have tested [lockdown] and it did not work,” he complains. “Look at the market, things are like three times what it used to be. They shouldn’t even think about it because Nigeria is not ready.”

Nigeria isn’t the only African country facing a second COVID-19 wave. In recent weeks, Kenya and South Africa have tightened social controls to curb the pandemic, and South Africa is confronting a new variant of the virus thought to be more highly transmissible.

Still, the overall trend in Africa has defied the doomsayers. The continent has 17% of the world’s population but roughly 3% of reported pandemic deaths.

Experts point to demographics – Nigeria’s median age is 18 – and climate and lifestyles as possible factors in the disease’s trajectory. Life-and-death experience with diseases like Ebola also prepared public health officials in West Africa better than health workers in many Western countries. COVID-19 data is limited by testing capacity, and some countries may be undercounting, but early and aggressive government interventions appear to have largely worked.

Migrant workers hit hard

The Middle East has not escaped so lightly; Iran has been particularly hard-hit, while wars in Syria and Yemen have decimated health systems. But just as catastrophic for the region was the crash in the price of oil at the same time that lockdowns choked local commerce. “The magnitude of these combined shocks has been quite severe,” says Daniel Lederman, deputy chief economist for the Middle East and North Africa at the World Bank.

These shocks have slashed job opportunities for the estimated 30 million migrants working in Gulf countries who send home at least $70 billion a year, according to the Gulf Research Center in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. A many as 1.2 million migrants could leave Saudi Arabia this year.

All told, global remittances from migrants were worth roughly $548 billion in 2019, three times the combined size of official foreign aid budgets. “These are private transfers that support domestic consumption, particularly for the poorest and most vulnerable families,” says Mr. Lederman.

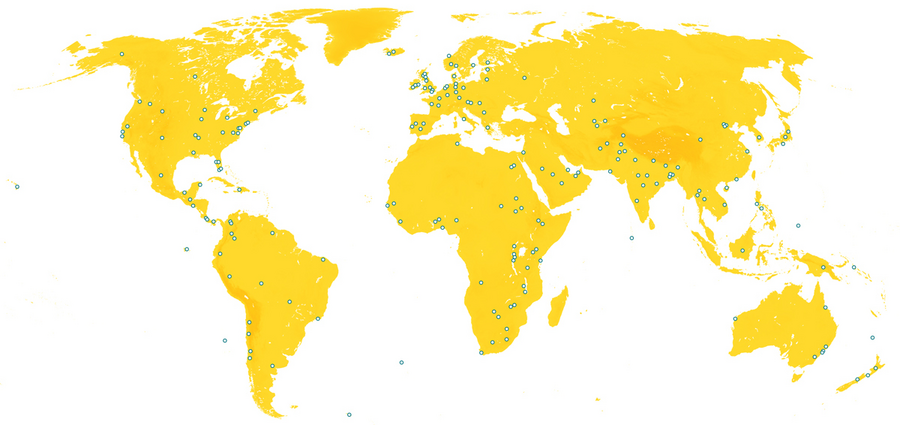

Cash transfers from Somali expatriates make up more than a third of Somalia’s economy. Wages paid in Russia flow back home to families across Central Asia. Central Americans rely on remittances from the U.S. The Philippines dispatches workers to every corner of the globe.

Dilip Ratha, the World Bank’s lead economist on migration and remittances, points to studies showing that in Sri Lanka, babies born to families receiving remittances weigh more because their mothers eat better. Migrant wages pay school fees, housing, and medical bills. “They’re a great vehicle for sharing prosperity between places,” he says. But now that vehicle’s engine is sputtering: Mr. Ratha’s research suggests that remittances to low- and middle-income countries have fallen by 7% this year, and that “the worst is not over yet,” in his words. “There is no scope for complacency.”

Replacing remittances

In countries like Egypt, where remittances normally account for nearly 7% of GDP, the COVID-19 effect is already reverberating. Mr. Ais shut his shampoo factory this month after waiting for a pickup in remittances to his customers that has not happened. The country expects as many as a million migrants, one-fifth of its overseas workforce, to return home from the Gulf this year.

Others too have lost their jobs abroad. Reba Abdul Halim worked for 15 years in a dairy factory in Amman, sending back at least $600 a month to his wife and four children in Egypt. After the factory closed this summer, he moved back to his home village. Money is tight, and his children no longer attend private schools. He complains that his life is on hold.

“You can’t climb your way out of economic hardship in a rural village in Egypt. There are no opportunities,” he says.

Opportunity is what drew Marjorie Chong, a Filipina, to the United Kingdom in 2004. In April, she was furloughed by her employer in London, and when government wage support ran out in October she took a part-time job at a migrant-rights nonprofit. She has been sending less money back this year.

She is hopeful that she can find a full-time job and start remitting more to her mother-in-law and to charities again. But for now, Ms. Chong is clinging on in London, not sure how much she can spare. “We’re all thinking about what we send,” she says. “I don’t have much here. I have to eat first.”

In tourist-free Bethlehem, a tranquil Christmas focused on family

For many residents of Bethlehem – so dependent on tourism – the pandemic has been a test of resilience. Yet a scaled-down Christmas has also offered something to cherish.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

-

By Fatima Abdulkarim Correspondent

The impact on Bethlehem from the loss of tourism and the Christmastime pilgrimage is hard to overstate: 28,000 of the 35,000 West Bank Palestinians working in tourism who lost their jobs due to the pandemic are from Bethlehem district, and 99% of tourism-related businesses in the area have closed, officials say.

But a tourism-free Christmas in the birthplace of Jesus is bringing something else in its place: Rather than a time of work, hustle, and packed streets, there’s a tranquil focus on family.

“We want to celebrate. We want to end this year with some joy in our hearts,” says Amal Yousef, selling homemade Christmas cookies to the few dozen masked visitors milling about the market.

Mary Giacaman has gone through her share of hardships this year, seeing her family’s souvenir shop in Manger Square shut down for an entire year due to the pandemic, and then contracting COVID-19 herself in October.

She says she is determined to have a special Christmas Day lunch with her family, give generously to charity, and end the year on a high note. “This was a loss and also a lesson that not everything is about work and money,” she says. “Christmas reminds us what really matters.”

In tourist-free Bethlehem, a tranquil Christmas focused on family

No tourists, no pilgrims, no large gatherings, and plenty of vacant rooms to be had, Christmas in Bethlehem this year is unlike any seen in decades.

In nearly empty Manger Square, normally bustling with visitors and pilgrims, it is easy to feel the pandemic’s impact on a city for which 50% of the economy relies on tourism – the vast bulk of it in the weeks leading up to Christmas and on the day itself.

But a tourism-free Christmas in the birthplace of Jesus this year is bringing something else in its place for residents: a tranquil focus on social bonds – a soothing balm amid a difficult holiday season and after an even tougher year.

Rather than a time of work, hustle, and packed streets, Bethlehem residents say this Christmas season is being marked by togetherness, time spent with family, and the revival of festive traditions from simpler yesteryears.

“I think that the best thing that has come out of this year is that we got to spend time with our families,” says Balqis Qoumsieh, who lost her job as a sales manager at a souvenir shop and now sells handmade resin jewelry and accessories from her home.

“I don’t see my family much this time of year because of work, but this time I’m celebrating with my family at home.”

At a scaled-back, one-day Christmas market in Bethlehem on Sunday, that was a widely held sentiment among Palestinian Christians.

“We want to celebrate. We want to end this year with some joy in our hearts,” says Amal Yousef at her stand, where she was selling homemade Christmas cookies made with dried fruits, chocolates, and even beer to the few dozen masked Palestinian visitors milling about the market.

Mary Giacaman, a mother of four, has gone through her share of hardships this year, seeing her family’s souvenir shop in Manger Square shut down for an entire year due to the pandemic, and then contracting COVID-19 herself in October.

She says she is determined to have a special Christmas Day lunch with her family to end the year on a high note.

“This was a loss and also a lesson that not everything is about work and money, and now we feel the value of togetherness and being with family,” she says.

Cutting back

The impact on Bethlehem from the loss of tourism and the Christmastime pilgrimage is hard to overstate: 28,000 of the 35,000 West Bank Palestinians working in tourism who lost their jobs due to the pandemic are from Bethlehem district, and 99% of tourism-related businesses in the area have closed, according to the Palestinian Ministry of Antiquities.

The 2019 Christmas season in Bethlehem saw 1.5 million hotel reservations, compared with zero this year, the Bethlehem Municipality says.

With so many families affected, Palestinians are cutting their budgets and planning more modest celebrations, prioritizing essentials such as food, electricity, water, and rent.

Two staples of the Palestinian Christmas shopping season being trimmed back this year are home furnishings and new outfits for the family to wear Christmas Day.

Like many Palestinians, Ms. Giacaman is putting her scaled-down holiday budget toward charity.

“It made me feel good at heart, because I now know what it is like to fall ill, to lose work, to be in isolation,” she says. “Christmas reminds us what really matters.”

In the Church of the Nativity, which holds the grotto believed to be the birthplace of Jesus, Serene Qoumsiye lights a candle to complete a pilgrimage she makes each year from nearby Beit Sahour on the last Sunday before Christmas.

She says this year’s muted holiday season makes it a perfect moment for reflection after a year of uncertainty.

“I want this year to end with some peace,” she says.

Old traditions reemerge

Many of the larger, more modern Christmas events and traditions in the Holy Land have been altered by the coronavirus.

The Christmas tree lighting in Manger Square, which kicks off the holiday season at the beginning of the month, was held via Facebook livestream rather than in front of a live audience. Weekend holiday markets were pushed to a single weekday.

Then there is the procession.

Each Christmas Eve, the Latin Patriarch of Jerusalem holds a procession from Jerusalem to Bethlehem, in more recent years passing through the separation wall checkpoint. At the entrance to Bethlehem he is met by a procession of scouts – Palestinian boys and girls in full regalia playing bagpipes and drums – who accompany him through the town to the Church of the Nativity.

This year’s procession is in doubt due to a ban on public gatherings and crowds.

And, rather than bringing the extended family of cousins, second cousins, uncles, and distant great aunts together at the family diwan, or gathering hall, Palestinian Christians are marking the holidays with their nuclear families only.

Which puts an even greater focus on the food.

Celebrating with “humility”

On Christmas Eve, most Christians, such as Olga Nasrallah, a Gazan now living in Jerusalem, will gather for a traditional mezze spread of finger foods and salads such as tabbouleh, meat-stuffed cracked-wheat kibbeh balls, hummus, stuffed grape leaves, and drinks.

Families say they will then sit together and celebrate midnight Mass at the Church of the Nativity on national television as they do every year, but for different reasons. In the past, throngs of dignitaries, clergy, tourists, and pilgrims made it difficult for locals to attend. This year it’s the curfews and bans on large gatherings.

Then, on Christmas Day, families are holding a large lunch, with each family following their own tradition.

Some, such as Alice Dueibes, a grandmother from the small Christian town of Zababdeh, serve a rice-stuffed roasted chicken, to celebrate “with a little humility,” while others will serve stuffed turkey or even lamb.

“This year we might not be happy, but we should look for the joy and live it,” Ms. Dueibes says. “We are keeping the tradition, but we are also living the changes, and what matters this holiday is that the children see the good and the joy.”

For her, this joy means preparing her signature wheat cookies stuffed with anise and dates and giving away chocolates to visiting children.

Many Palestinians are finding joy this year in baking at home, preparing the traditional Christmas sweet ghraybeh, the Levantine version of shortbread cookies – crumbly, buttery, and often decorated with a pistachio on the top.

Wissal Kheir, browsing the Bethlehem market, says that while the lack of pomp and celebrations has taken away some of the joy this holiday season, “we are still going to carry on our traditions.”

“We don’t know if there will be scouts or if there will be a lockdown or a curfew, but we will be with our sons, daughters, and close family members,” says Ms. Kheir.

“We might not be able to wear new clothes this year, but we can still gather around a meal.”

Points of Progress

The other 2020: 274 ways the world got better this year

Here it is: A summary of the 274 points of progress we found in 2020. Despite the hardship and heartache of the past year, the world took important steps forward, and that’s worth recognizing.

The other 2020: 274 ways the world got better this year

It’s more than good news. Points of progress are the moments when humanity takes another step forward. This year, we covered 274 concrete ways the world got better. That includes 29 moments the world shared together – scientific breakthroughs in outer space, heartening reports on reforestation efforts, and international commitments to defend human rights – and even more stories that were unique to specific regions, countries, or cities. In case you missed it, here’s a recap of some of the headlines that brought us hope this year.

North America

Racial justice was the top theme of progress observed in the United States this year, as communities worked to address past mistakes and combat racism today. Black Americans were appointed to higher roles in academia and the Catholic Church, and Black women in particular made gains in sports, politics, and the armed services. Symbolic gestures recognized individual Black Americans who were posthumously honored with a Pulitzer Prize, the naming of a new naval supercarrier, and the renaming of NASA headquarters in Washington.

Other marginalized groups saw progress, too. Record numbers of Native Americans, women, and LGBTQ people ran for office in 2020, and a survey by the Ruderman Family Foundation found that disability representation in media has improved since 2016. (The Christian Science Monitor, Center for American Women and Politics, NPR)

Africa

African countries achieved a wide variety of progress, from fostering peace and security to promoting sustainable agriculture. Angola’s National Demining Institute cleared about 5 acres of land mines in the first half of 2020, removing 9,982 explosive devices – relics of the decadeslong civil war – and paving the way for safer travel and development opportunities. In an international justice breakthrough, top Rwandan genocide suspect Félicien Kabuga was captured after years on the run. The urban farming movement is gaining momentum in Johannesburg, South Africa, where more than 40% of its population of 4.4 million is considered food insecure, and a new app is helping Zimbabwe’s farmers secure plots of land. (The Christian Science Monitor)

Latin America and the Caribbean

Of the 30 points we published on Latin America and the Caribbean, nearly a third dealt with the conservation of plants, insects, and animals. Marking the end of one of the world’s most successful captive reproduction programs, centenarian tortoise Diego finally returned to the Galápagos island of Española, where he will live out his retirement among hundreds of descendants.

In the South Atlantic Ocean, a new conservation effort is just beginning around the remote archipelago of Tristan da Cunha, where scientists are establishing the world’s fourth-largest marine sanctuary. Meanwhile, in Colombia, ex-combatants are training to help preserve the country’s biodiversity. (The Christian Science Monitor)

Europe

From Russia to Portugal, we saw communities in Europe tackling climate change with new vigor. Austria closed its last coal-fired power plant on April 17, joining a growing number of countries reducing their reliance on coal; Germany is banning single-use plastic in line with a European Union directive; and Lithuania is recycling at record levels thanks to a deposit-refund system introduced in 2016. Eco-friendly transit alternatives are emerging in the United Kingdom. Northern Scotland’s Orkney Islands became an unlikely leader in the renewable energy field by using their excess wind power to experiment with hydrogen fuel, and the U.K.’s first all-electric intercity bus route began carrying passengers between Edinburgh and Dundee this fall. (The Christian Science Monitor)

Asia

Asian countries made strides in public health, safety, and infrastructure this year. As Hong Kong’s government uses new transitional housing initiatives to help low-income families live with dignity in one of the world’s most expensive cities, The Salman Sufi Foundation in Karachi, Pakistan, established the nation’s first privately managed public restrooms.

Even better, more kinds of people can access these services safely: In March, a court in Hong Kong ruled that married same-sex couples can apply for public housing. And the Karachi project’s coordinators says their focus is on the well-being of women, transgender residents, and the disabled community. (The Christian Science Monitor)

Oceania

The global reckoning over racism has helped push Native rights and empowerment into the spotlight in Oceania. Guam launched its first publicly funded immersion program to preserve the indigenous Chamoru language in the Mariana Islands, which declined to near extinction during centuries of Spanish and American colonialism. In July, Australia appointed its first Indigenous consul-general. When Benson Saulo takes his post in the United States, he says he hopes to “connect with other Indigenous people and highlight ... the global Indigenous economy.” (The Christian Science Monitor)

Middle East

Legal reforms in the Middle East pushed countries closer to gender equality. In Afghanistan, mothers’ names will now be printed along with fathers’ on national identification cards, helping to normalize women’s presence in public life. At the same time, a growing #MeToo movement in Egypt has created online spaces for women to speak up about assault, and parliament recently approved a law granting automatic anonymity to sexual violence survivors.

Gender roles continue to expand in Saudi Arabia, as well. The kingdom’s first women’s soccer league made headlines in February, but officially kicked off in November after being delayed by the pandemic. Another change this year? Men, women, and children can now dine in the same section of a restaurant. (The Christian Science Monitor, BBC)

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Home is where the work is

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

For centuries the morning cry has been “off to work we go.” The workplace was at a distance, both physically and mentally, from our homes.

But the pandemic has left a good portion of workers – some 42% of Americans, by one estimate – doing their jobs from their homes.

In some ways society has returned to the days before the 18th-century Industrial Revolution, when working from home was the norm. Then both men and women might make brooms or shoes or weave cloth in their homes – a forerunner of today’s gig economy.

People controlled when, and for how long, they worked each day. Parents juggled child care and earning a living as needed.

Peering into 2021 it’s unclear when – or if – millions of people will return to offices. Some businesses have set goals to bring back workers by spring or summer; others aren’t even trying to project when it might happen.

In time, no doubt, many workers will drift back to rubbing elbows in offices, at least part of the time. But for others, the home and work divide has been forever breached.

Home is where the work is

For centuries the morning cry has been “off to work we go.” The workplace was at a distance, both physically and mentally, from our homes.

But the pandemic has left a good portion of workers – some 42% of Americans, by one estimate – doing their jobs from their homes. Those who don’t are largely “essential workers” whose work demands they leave home behind each day.

In some ways society has returned to the days before the 18th-century Industrial Revolution, when working from home was the norm. Then both men and women might make brooms or shoes or weave cloth in their homes, often with material supplied by an employer. (In Britain, houses had larger windows upstairs to let in sunlight where work was taking place, The Economist points out.) When these home workers turned in the finished product, they were paid not by the hour but for each piece completed – a forerunner of today’s gig economy.

Working away from home brought advantages, though, including the ability to join together with others to form labor unions that boosted wages and improved working conditions.

Still, working from home wasn’t all bad. People had control over when, and how long, they worked each day. Parents were able to juggle child care and earning a living as needed. In the United States, in fact, one set of data suggests that it wasn’t until 1914 that most people were employed outside the home.

Peering into 2021 it’s unclear when – or if – millions of people will return to offices. Some businesses have set goals to bring back workers by spring or summer; others aren’t even trying to project when it might happen.

The list of jobs possible from home keeps expanding too: The shop-at-home era created by Amazon et al. has yielded thousands of new at-home jobs filling orders for call centers. That has cushioned somewhat the huge job losses in service industries, such as restaurants and other retailers. More opportunities are needed to absorb those workers, especially in communities of color disproportionately employed in the service industries.

Many people have found they enjoy working from home. For some the time saved in commuting is being happily reinvested in more time spent with family, one study suggests. (But for workaholics, especially in management, work from home may just extend the workday.)

The concept of home as a haven of rest, shielded from the world of earning a living, is under revision.

The new generation of home-based workers is investing in equipment, furnishings, and gadgets that make their home work more enjoyable. (Noise-canceling headphones, for example, can help create an oasis of calm in a busy household.) People who’d never attended a Zoom meeting or engaged in a Slack conversation have become tech savvy much more quickly than they imagined possible.

Working from home may also mean work – and home – can exist anywhere. This opens up the possibility to help with a care situation for a family member in another city or even to try life simplified down to an Airstream trailer.

Combining work with home can also require devising new ways of structuring family life, from how to divvy up the household chores and child care to deciding who’ll get that prime spot with the morning sun or the lovely view to set up shop.

In time, no doubt, many workers will drift back to rubbing elbows in offices, at least part of the time. But the home and work divide now has been forever breached.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

‘On earth peace, good will toward men’

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 1 Min. )

Here’s a short and sweet offering that speaks to the qualities at the very heart of Christmas. The accompanying audio also includes Mary Baker Eddy’s poem “Christmas Morn” being sung.

‘On earth peace, good will toward men’

The basis of Christmas is the rock, Christ Jesus; its fruits are inspiration and spiritual understanding of joy and rejoicing, – not because of tradition, usage, or corporeal pleasures, but because of fundamental and demonstrable truth, because of the heaven within us. The basis of Christmas is love loving its enemies, returning good for evil, love that “suffereth long, and is kind.”

– Mary Baker Eddy, “The First Church of Christ, Scientist, and Miscellany,” p. 260

Glory to God in the highest, and on earth peace, good will toward men.

– Luke 2:14

Bonus content! To listen to Mrs. Eddy’s poem “Christmas Morn” being sung, click the play button on the audio player above.

“Christmas Morn”

Words by Mary Baker Eddy

Music by William V. Wallace

Performed by Rebecca Minor, voice, and Bryan Ashley, organ

From Embraced © 2018 The Christian Science Publishing Society

A message of love

Season’s greetings

A look ahead

Thank you for joining us today. Before you leave, we wanted to bring your attention to a beautiful Home Forum essay about the author’s Aunt Gertrude, who did a lot more than just make plum pudding.

Also, tomorrow, you will be receiving a Christmas Eve special send with six of our top stories from 2020, as picked by the editors. We’ll follow that up with a Christmas Day Home Forum story on Friday. And next week, we’ll mark the holiday season by sending you an audio interview each weekday with a Monitor contributor. They discuss how they “rethink the news” as Monitor journalists. The regular Daily will resume Jan. 4, 2021.