- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usMonitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

One state’s strong leadership in pandemic fight

West Virginia and pharmaceuticals have a dark association. The state sits at the epicenter of America’s cruelly persistent opioid epidemic, with an unwelcome top ranking in overdose death rate.

Victimhood can be an easy narrative to extend. West Virginia anchors a region that’s often cast as “uniquely tragic and toxic,” as Elizabeth Catte wrote in her 2018 book, “What You Are Getting Wrong About Appalachia.”

But as she and others point out, it’s a story that’s sorely incomplete.

We reported in 2017 on how one West Virginia city paired law enforcement with compassionate outreach to attack the cycle of hopelessness that fuels addiction.

Now, with worldwide responses to a coronavirus pandemic ranging from disjointed to stunningly ad hoc, West Virginians are applying a spirit of self-determination to making sure COVID-19 vaccines get to those who want them.

Last week it rolled out a tech partnership that curbs waste by alerting eligible vaccine-seekers when no-shows make doses available. Before that, the state chose to lean on its small, independent pharmacies, more nimble and arguably more incentivized than the big, sometimes understaffed chains other states use.

“As my uncle always told me,” one West Virginia pharmacist told the AP, “these people aren’t your customers, they’re your friends and neighbors.”

Among U.S. states, West Virginia was first to meet initial needs in its nursing-care facilities. That’s a welcome top ranking in responsiveness and humanity, and a clear sign of agency.

“Our album is filled with images of people who suffered,” writes Ms. Catte, “but also people who fought.”

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Reopen public schools? How Chicago became ground zero for debate.

As uncertainty about COVID-19 and the limits of online learning muddy disputes between city officials and teachers unions about reopening, the clear reveal is systemic inequality.

Escalating brinkmanship between Chicago and the teachers union over whether children can return to school is wearing out families. “I feel like a pawn in a chess game,” says Miles Galfer, a father of two Chicago Public Schools students. “Don’t tell me we’re opening until we’re opening.”

It’s been tough, he adds, because virtually all his neighbors’ children in his upscale, majority-white neighborhood have been attending private school in person. “We’re getting tired of the union calling all the shots,” he adds.

Growing evidence shows that online instruction is falling short while multiple studies indicate that schools are not major transmitters of COVID-19. Combined with rising political pressure to reopen, it threatens to turn public opinion against the unions. But there’s a complicating factor: The health risks of reopening schools vary by community and are higher in low-income and African American and Latino majority neighborhoods.

“There are no good options here,” says Thomas Dee, a professor at the Stanford Graduate School of Education. On the one hand, “we have leading evidence that parents and children are suffering under school closures.” On the other hand, political leaders are asking teachers to bear the risks caused by the country’s failure to contain the pandemic.

Reopen public schools? How Chicago became ground zero for debate.

Chicago has become the epicenter of a widespread debate over whether to reopen public schools.

On Sunday evening, Mayor Lori Lightfoot, a Democrat, ordered teachers to return to the classroom on Monday and invited kindergarten through eighth grade students wanting to return to report to school the following day. “Our schools are safe,” she said at a news conference. “We know that because we have studied what’s happened in other school systems in our city,” referring to Roman Catholic, charter, and other schools that have opened since the pandemic. Some 5,000 prekindergarten as well as special education students have been attending public school since Jan. 11.

The Chicago Teachers Union has told its members to continue teaching remotely and said it would strike if teachers are punished for not returning.

For parents, the escalating brinkmanship between the city and the union has grown wearying. “I feel like a pawn in a chess game,” says Miles Galfer, a father of a second grader and kindergartner in the Chicago schools, whose wife is a school administrator. “Don’t tell me we’re opening until we’re opening.”

It’s been tough, he says by phone, because virtually all his neighbors’ children in his upscale, majority-white neighborhood have been attending private school in person. One private school has even begun using the playground at his children’s public school. “We’re getting tired of the union calling all the shots,” he adds.

This parent fatigue – if it grows – represents a major threat for teachers and their unions. Growing evidence shows that online instruction is falling short while multiple studies indicate that schools are not major transmitters of COVID-19. Combined with rising political pressure to reopen from the Biden administration and state and local officials, this threatens to turn public opinion against the unions and weaken their leverage. But there’s a complicating factor: The health risks of reopening schools vary by community and are higher in low-income and African American and Latino neighborhoods.

“There are no good options here,” says Thomas Dee, a professor at the Stanford Graduate School of Education in California. On the one hand, “we have leading evidence that parents and children are suffering under school closures.” Between April and October 2020, the share of emergency-department visits for mental health reasons rose 24% for children ages 5 to 11 and 31% for those 12 to 17, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). On the other hand, some political leaders are asking teachers to bear the risks caused by the country’s failure to counter and contain the pandemic.

Schools have reopened in patchwork fashion around the country. Four states – Arkansas, Florida, Iowa, and Texas – have ordered public schools to open, according to data compiled by Education Week. Six others have ordered partial closings in areas where infections are high. The rest of the states have left it up to local school districts.

It’s telling that union-administrator tensions have flared in public school districts with high concentrations of people of color:

- In Fort Lauderdale, Florida, and surrounding Broward County (where roughly three-quarters of the students are Black or Hispanic), the teachers union sued the school system when administrators began forcing teachers diagnosed with illness to return to the classroom. A mediator agreed with the administration that 600 seriously ill teachers deserved special accommodation, not the 1,100 that the union claimed.

- In Virginia’s Fairfax County, with a high concentration of Hispanic students, parent groups have criticized the school superintendent for repeatedly pushing back the scheduled reopening.

- In California, where some 70% of public school students are people of color, the governor’s plans to begin a phased reopening starting Feb. 15 is foundering because of union opposition.

The outlook on reopening schools varies by race. According to a survey of 858 parents this past summer quoted by the CDC, 62% of non-Hispanic white parents said school should open this past fall, while only 46% of non-Hispanic Black parents and 50% of Hispanic parents agreed. A more recent survey of Chicago parents by the union has also found a similar racial disparity.

“There’s much more skepticism in Black and brown communities about whether or not we can reopen schools safely,” says Randi Weingarten, president of the American Federation of Teachers, whose Chicago local union is fighting the reopening of schools. “We are fighting fear as much as we are fighting COVID.”

That fear has created a paradox: Low-income families and families of color, who have suffered the most in terms of exposure to the pandemic and its financial and educational effects, are also the most reluctant to open the schools – even knowing it will affect their own careers.

“As a Black woman who cares a lot about children of color, these children are getting less and less educated” the longer that remote learning goes on, says Yolande Beckles, a community educator in Los Angeles.

Up to now, the pandemic has helped boost teachers’ reputations in the public eye. “One of the things the pandemic has shown us is how critical they are,” says Katharine Strunk, an education professor at Michigan State University in Lansing. “Teachers are not only educators, in the sense of teaching math and science, but teachers are also social workers, they’re also first responders.”

Teachers unions may also have gotten a public relations boost. Between May 2019 and November 2020, the positive perception of teachers unions edged up from 42% to 46%, according to a survey by Education Next.

But the unions’ stance risks being undercut as teacher vaccinations expand and research shows that schools are safer than many believe. An article last week in JAMA, a journal from the American Medical Association, found that schools were not big transmitters of the virus if safety protocols are followed.

That’s a pretty big if, especially in low-income neighborhoods, where crowded dilapidated schools have inadequate ventilation and make it difficult to maintain social distancing, says Becky Pringle, president of the National Education Association, the nation’s largest teachers union. “Our Black and brown and Indigenous kids have been going to school in these dilapidated buildings that were unsafe. ... [Their teachers] are saying, ‘We can’t go back to school safely without the resources’” to fix these things.

As part of its pandemic relief plan, the Biden administration is calling for at least $130 billion for K-12 schools with some portion of an additional $350 billion earmarked for state and local government aid.

Determining when those safe conditions have been reached in these schools remains in the eye of the beholder. Last week, the California Teachers Association told California Gov. Gavin Newsom, a Democrat, that schools in counties with high infection rates should remain closed for 100 days.

That doesn’t sit well with Ms. Beckles, who runs the Knowledge Shop LA, a nonprofit education center for children from less privileged families in South Los Angeles. When the pandemic hit, she quickly slimmed down her enrollment and pivoted to an all-day center where working parents could drop off their kids. The children had access to robust Wi-Fi and serviceable laptops to connect with their teachers.

While private schools in the area and her business quickly figured out how to reopen with adequate safeguards, the public school system took four to five months, she points out. “That bureaucracy does what it does: nothing. [And] at the end of the day, teachers put teachers first. That’s what the teachers union is all about.”

“If the goal is to educate children in a healthy and safe environment, the answer is not: ‘No, we can’t do this,’” she adds. “The answer is there are many ways to do this.”

A deeper look

Breaking up is hard to do

The protests roiling Russia today are keyed to a dissident’s return. But deeper context matters: Broadly, Russia’s woes are still geopolitical aftershocks from the Soviet Union’s fall.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 12 Min. )

As Russia tries to redefine its place on the world stage, the Kremlin is having to come to terms with the fact that it is no longer at the center of the Soviet Union, and that it has to deal with that empire’s former republics in a new and sustainable way. That effort, it is now clear, will largely depend on whether Moscow can settle on a new approach to those once-Soviet republics now that they are independent neighbors.

A primary goal of President Vladimir Putin has been to keep nations such as Ukraine and Georgia from joining the European Union and NATO. Moscow used military force in those countries to prevent such an outcome and maintain its influence, but that undermined Mr. Putin’s hopes of being treated as an acceptable and equal partner in the West.

Today, the Russian authorities are more measured, less inclined to involve themselves in the crises that break out in what they call their “near abroad.” Is Russia really changing? “Perhaps Russia understands its limitations better,” says one analyst, Andrei Kortunov. “You can argue that Russian leaders have gained some wisdom.”

Breaking up is hard to do

Most people under 40 have seen newsreel footage, but have no personal memory of that cold December evening in 1991 when, in an act of symbolic finality, the red Soviet hammer-and-sickle flag was pulled down from Moscow’s Kremlin, and the white-blue-red Russian tricolor fluttered up to take its place. The sudden collapse of the USSR, a giant ideologically driven empire that straddled half the world for 70 years, was a seismic event that everyone learns about in school, but now seems far in the past.

Politicians and policymakers in Moscow perceive it differently. For them the Soviet collapse feels like only yesterday, and the post-imperial strains it caused remain the stuff of daily headlines. The USSR was a huge, multinational monolith that controlled a vast array of satellites and client states, and spread its geopolitical influence and ideological challenge into every corner of the world. Moscow’s planners today must contend with a post-Soviet neighborhood in which all of the USSR’s former Eastern European allies and even three of the 15 former Soviet republics have already joined the European Union and NATO, while others are threatening to do the same. Of the remaining 12 ex-Soviet republics, many have shucked off Russian influence and are gravitating into the orbit of outside powers that were once thoroughly excluded from the entire region.

In the west, Ukraine, Belarus, Georgia, and Moldova are strongly attracted to Europe, with its very different economic model and values system, and all have experienced internal eruptions aimed at curbing Russian influence. On the southern flank, Azerbaijan recently leveraged Turkish assistance to wage a successful war against Russian-allied Armenia, with the result that Turkish influence is now thoroughly ensconced in the former Soviet Caucasus region. And in former Soviet Central Asia, China competes openly with Russia for trading preferences, access to resources, and political clout.

The once solid, mighty, and unified Soviet colossus has turned into a fragmented and fractious sea of woes for the Kremlin, and one that only seems likely to breed more internal challenges and external intrusions in the future. That is surely what Russian President Vladimir Putin meant when he once described the Soviet Union’s demise as “the greatest geopolitical catastrophe of the 20th century.”

This portrait of a beleaguered Russia, which regards itself as being perpetually on the defensive, might baffle some in the West, where President Putin’s new Russia is seen as a growing threat, and one of the two main global adversaries facing the United States. From a Western viewpoint, Mr. Putin’s Russia is resurgent, angry over its loss of the USSR’s superpower status and impatient to reassert its power around the world. Western media regularly feature headlines of alleged Russian aggression, such as interfering in U.S. elections, hacking and spreading disinformation, sowing discord between NATO allies, and launching very real military incursions in places like Ukraine and Syria.

But these two views are not incompatible. As it struggles to accept the continuing disintegration of its former Eurasian empire and seeks to prevent ex-Soviet republics from defecting entirely from its perceived sphere of influence, Russia is also trying to redefine its place on the world stage. It is no longer the Soviet Union, yet it still wishes to be a global power to be respected and reckoned with. On both counts, Mr. Putin’s Russia is very much a work in progress. How it comes to terms with the conflicting aspirations of its immediate neighbors, which are all struggling to establish their post-Soviet identities, will determine whether Russia can find a new, less conflict-ridden place among the world’s big powers.

“We are still in the post-imperial stage, where Russians have not quite gotten used to the changes ushered in by the Soviet collapse, nor quite accepted that it is no longer the USSR,” says Fyodor Lukyanov, editor of Russia in Global Affairs, a leading Moscow-based foreign-policy journal. “After all, Russia has never lived within these borders before in its history.”

The former Russian Empire and the Soviet Union were both vast, multinational empires that defined themselves by ideological principles, not ethnic or national ones. Russia, stripped of empire and basically reduced to its 17th-century borders, is a newly minted nation-state – much bigger but otherwise a lot like its fellow ex-Soviet republics – that has yet to find a clear post-imperial identity.

Other newly independent states like Ukraine, Georgia, Azerbaijan, and Kyrgyzstan could reinvent themselves in terms of their own local ethnic and historical traditions. They could also galvanize public solidarity by pushing against Moscow’s continued domination and reach out to external powers in Europe and Asia for support. But none of these options was available to Russia. It was no longer the center of a great empire, yet it was still an immense nation that sprawled across two continents, possessed the world’s second-largest arsenal of nuclear weapons, and claimed to be the successor state of the Soviet Union.

“Russia was no longer the core of the former Soviet Union, but it was still a big multinational and multiconfessional state,” says Mr. Lukyanov. “You have to accept that Kaliningrad, a former German territory on the Baltic Sea, and the republics of the North Caucasus – which are mostly Muslim and non-Slavic – are part of Russia today, while Ukraine and Belarus, which are overwhelmingly Slavic and Orthodox Christian, are not part of Russia. All that takes some getting used to.”

Conservative pragmatism

When the soviet union collapsed nearly three decades ago, the news reverberated around the world. But it was mostly greeted with apathy in the streets of Moscow and other Russian cities. The end was not brought on by war or popular revolution, but by a secret deal signed by the Communist-era leaders of Russia, Ukraine, and Belarus, which declared the USSR dead and replaced by an unfamiliar new entity, the Commonwealth of Independent States. Most of those states, in the Caucasus and Central Asia especially, were not party to the arrangement and woke up the next day to discover that they were now independent nations.

“I do not regret for a moment signing that accord,” says Stanislav Shushkevich, the Belarusian leader who took part in the secret meeting and went on to become the first president of independent Belarus. “It enabled the USSR to disintegrate peacefully, without bloodshed.”

Though the Soviet Union was legally dissolved, the realities of life under it persisted. As the example of Belarus shows, most post-Soviet countries were deeply entwined by decades, in some cases centuries, of being part of the same empire. Russian remained the language of communication between the new states, and in many cases still is. Their economies had been systematically integrated by central planners in Moscow, and they are far from disentangled to this day. The free flow of people within the former Soviet Union left big diasporas of Russians in many former Soviet republics, while millions of people from those new states woke up to find themselves living in independent Russia.

“It was one thing for countries to declare themselves independent, quite another for those countries and their peoples to attain the attributes of genuine independence,” says Sergei Markedonov, an expert with MGIMO University in Moscow. “The process of unraveling the Soviet Union was much more complicated, very messy, and is still going on.”

Belarus elected a new president in 1994, Alexander Lukashenko, who stressed nostalgic Soviet-style political and economic policies. In practice, he depended heavily on Russian subsidies like cheap oil and gas to keep his regime afloat. Political leaders in Moscow, anxious to maintain influence in the former Soviet Union – what they termed the “near abroad” – gladly extended those subsidies. Thanks to those arrangements, and with the help of repeated rigged elections, Mr. Lukashenko is still in power, 26 years later. Huge numbers of Belarusians protesting in the streets in recent months are aiming to break those links to Russia and accelerate Belarus’ trajectory to full independence, but have so far failed.

Mr. Shushkevich, bitter and angry, says that the pull of Soviet-style economic and political dependency continues to thwart the aspirations of people throughout the region. “The empire was liquidated, yet it lives on,” he says. “Some leaders, like Putin and Lukashenko, are actively trying to restore it.”

Seen from Moscow, the protests in Belarus – and previous popular revolts in Georgia and Ukraine – were foreign-inspired efforts to dismember Russia’s former Soviet sphere of influence and isolate Russia. The greatest fear in Moscow is that these former Soviet republics will break ties with Russia and join the European Union and NATO, as the three former Soviet Baltic states did, thus isolating Russia completely from its own backyard.

Since Mr. Putin ascended to the Kremlin and began reversing Russia’s own post-Soviet decline, he has made halting the advance of outside powers into the former Soviet region a top priority. In 2008, a Russian army invaded Georgia to prevent pro-Western President Mikheil Saakashvili from staging a military reconquest of the breakaway Georgian territory of South Ossetia, a Russian protectorate. Had Mr. Saakashvili succeeded in reuniting his fractured country, he might have gotten much closer to his stated goal of making Georgia a viable candidate to join NATO.

Similarly in Ukraine in 2014, after a pro-Western street revolt unseated Moscow-friendly President Viktor Yanukovych, Moscow intervened militarily to annex the mainly Russian-populated Crimean Peninsula, and to back anti-Kyiv rebels in the Russian-speaking east of Ukraine.

“Rejoining Crimea to Russia was a turning point,” says Mr. Lukyanov. “For the first time Russia rewrote borders, and the internal contours of the Soviet Union ceased to exist. It also demonstrated to the West for the first time that the price of EU and NATO expansion into the post-Soviet area could be very high. Russia’s determined actions have made its point to the world: that its wishes cannot be ignored. Not so many in the West may like Russia, but few today will deny that it plays an important role.”

Russia acted forcefully to prevent what it feared would be a precipitous leap by its most important post-Soviet neighbor, Ukraine, into the Western camp. As with Georgia, those actions likely succeeded in that immediate goal. Almost nobody is talking any longer about Ukraine or Georgia joining NATO, much less the EU. But it also came at a heavy long-term cost. Ukrainians, most of whom speak Russian and feel historically close to Russia, have been alienated by Moscow’s treatment of them, and the damage may be difficult to repair.

“It simply has to be understood that no matter who might be leader of Russia, the enlargement of a hostile military bloc into our region will be viewed as a serious challenge,” says Mr. Markedonov.

But unlike the former USSR, Russia is not hidebound or completely inflexible. Most experts argue that it’s capable of learning from mistakes and reaching compromises.

“Russia’s approach might be described as conservative pragmatism,” Mr. Markedonov says. “Its behavior isn’t ruled by an ideology, but it is allergic to revolutions – especially in its own neighborhood – or attempts to break the status quo,” and could therefore be open to evolutionary changes.

Foil of convenience?

It’s hard to imagine that Russia’s Cold War-like standoff with the West will be resolved anytime soon. Mr. Putin may have achieved his goal of making Russia more respected and even feared in the world, but he is further from finding a sustainable post-Soviet place for Russia in the global order, in which it would be treated as an acceptable and equal partner, than he was when he began talking about that goal 20 years ago.

“For many in the U.S., Russia seems to be the foil of convenience,” says Andrei Kortunov, head of the Russian International Affairs Council, which is affiliated with the Foreign Ministry. “The U.S. needs an enemy. That’s how the system works. We’re competing with China for this dubious role, but it looks like we are the preferred enemy. The relationship with China is complicated, with many economic and other complexities, while it looks much easier to sanction, isolate, and blame Russia. So, there is no reason to expect any improvements, even if a new U.S. administration is coming in.”

But there may be room for Moscow to improve relations with countries in the post-Soviet neighborhood. Russia and Georgia went through a period of strained relations following their 2008 war, punctuated by trade bans and harsh diplomatic rhetoric. But tensions have since eased, trade is on the upswing, and Georgia has once again become a major destination for sunshine-starved Russian tourists.

A recent spate of political crises around the post-Soviet region has produced a much calmer and more measured response from Moscow than previous ones did. When Belarusians took to the streets last summer to protest yet another rigged election, rumors of Russian intervention to prop up the beleaguered Belarusian leader, Mr. Lukashenko, were rife. But Russian security forces remained in their barracks, and the Moscow media gave sympathetic coverage to the pro-democracy protesters in Belarus, while the Kremlin continues to pressure Mr. Lukashenko to move ahead with promised constitutional reforms that might yet ease him out of power.

Moscow appears to have been completely indifferent to a recent disorderly change of power in Kyrgyzstan. Nor did it have much to say when November elections in Moldova removed a pro-Russian president and replaced him with a pro-Western one. Most impressively, Russia refrained from extending any assistance to its nominal ally, Armenia, when neighboring Azerbaijan launched an autumn war to recover Azeri territories that had been occupied by Armenia for almost 30 years. Russia subsequently intervened to impose a cease-fire along diplomatic lines that have been advocated by the world community for years, and inserted Russian peacekeeping forces to enforce the settlement.

Even in Armenia, polls show that attitudes toward Russia remain positive. “Of course the USSR is in the past and, though older people are nostalgic, there’s no going back,” says Alexander Iskandaryan, director of the independent Caucasus Institute in Yerevan. “If Russia acts in pragmatic ways, and uses mainly soft power methods, better relations may well develop.”

Fixing the shattered relationship with Ukraine is, perhaps, Moscow’s toughest challenge. Yet despite nearly seven years of war and mutual sanctions, Russia remains one of Ukraine’s leading trade partners, and whatever they may think of each other’s governments, polls show that Ukrainians and Russians overwhelmingly still like and respect one another.

“In order to improve relations, Russia should become a more normal state and drop its imperial-like arrogance toward Ukraine. But there’s something more,” says Vadim Karasyov, director of the independent Institute of Global Strategies in Kyiv. “Russia has a chance to become a good example, a model of stability, a normal friend to Ukraine. It’s impossible to return to the past, but in this chaotic world, with the influence of the West fading, it’s possible to at least imagine a new level of mutual respect and cooperation emerging. A lot of that is up to Russia.”

Experts are divided about the significance of Russia’s new stance of tolerance toward political crises in its immediate neighborhood, even when they have anti-Moscow overtones. Is it because of Russia’s own internal problems, including the coronavirus pandemic and Mr. Putin’s recent, much-discussed relative disengagement from his duties? Or has the Kremlin relaxed because the West, preoccupied with its own problems and reeling under the erratic four-year leadership of Donald Trump, has retreated from involvements in the post-Soviet region? Or is Russia really changing?

“The case can be made that there is a learning curve in Moscow. Not a particularly steep one, but we can discern changes,” says Mr. Kortunov of the Russian International Affairs Council. “Today’s Russia knows the USSR is gone and cannot be put back together. Lately, it seems much more willing to let events in its own region take their course. Perhaps Russia understands its limitations better, after three decades of post-Soviet experience, and you can argue that Russian leaders have gained some wisdom, a realization that political changes in these countries should not be overrated.

“I mean, it really doesn’t matter who is president of Moldova, does it?”

The Explainer

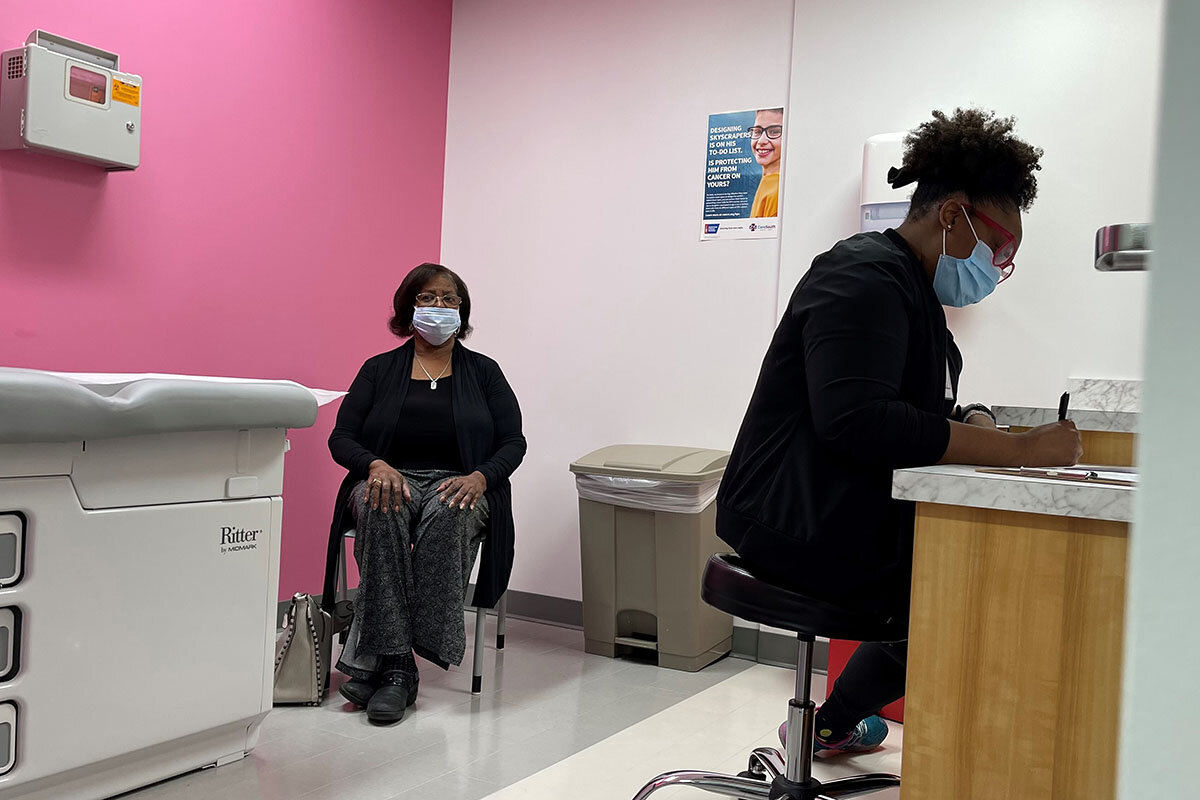

Confused by pandemic data? Here’s some help reading it.

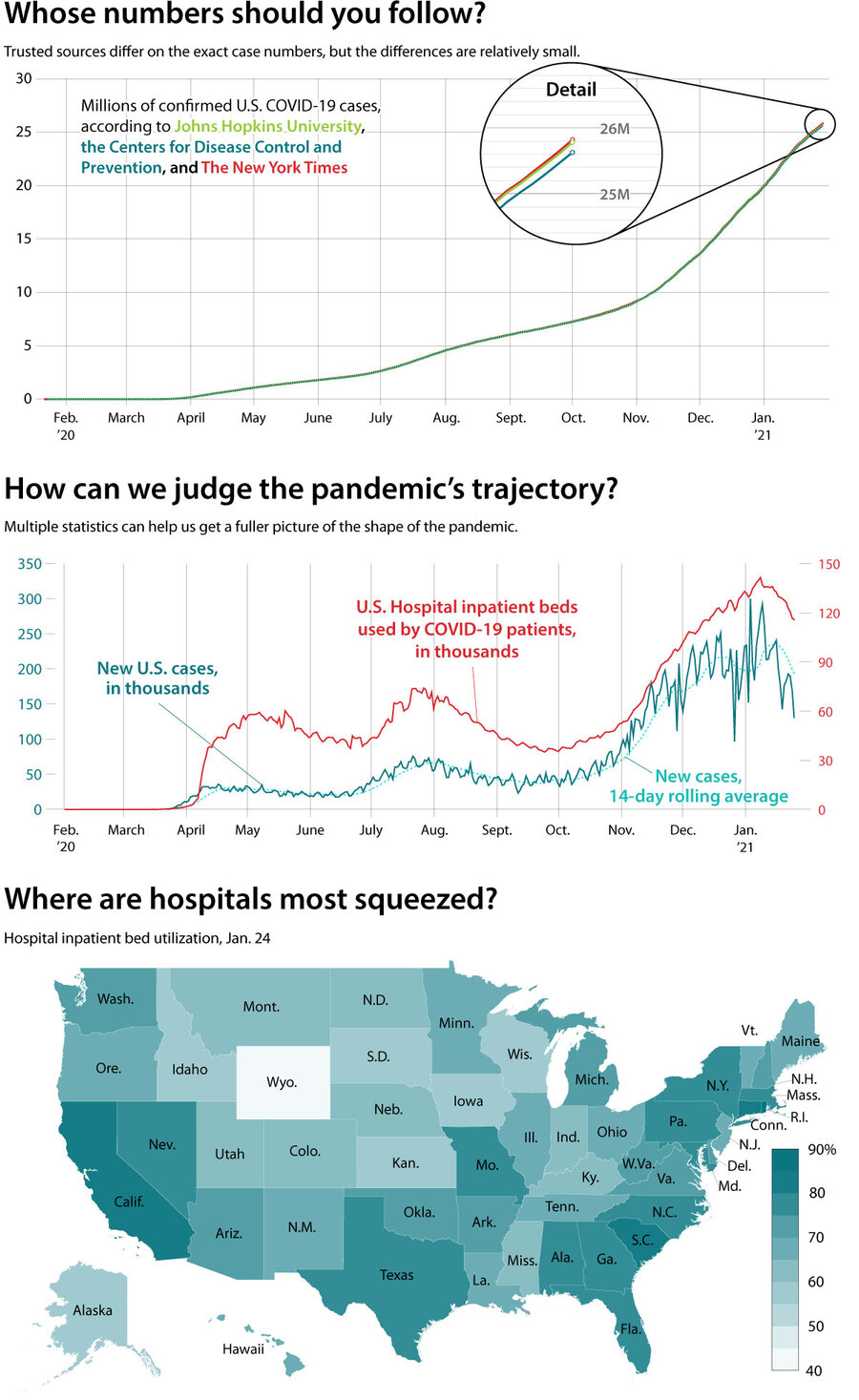

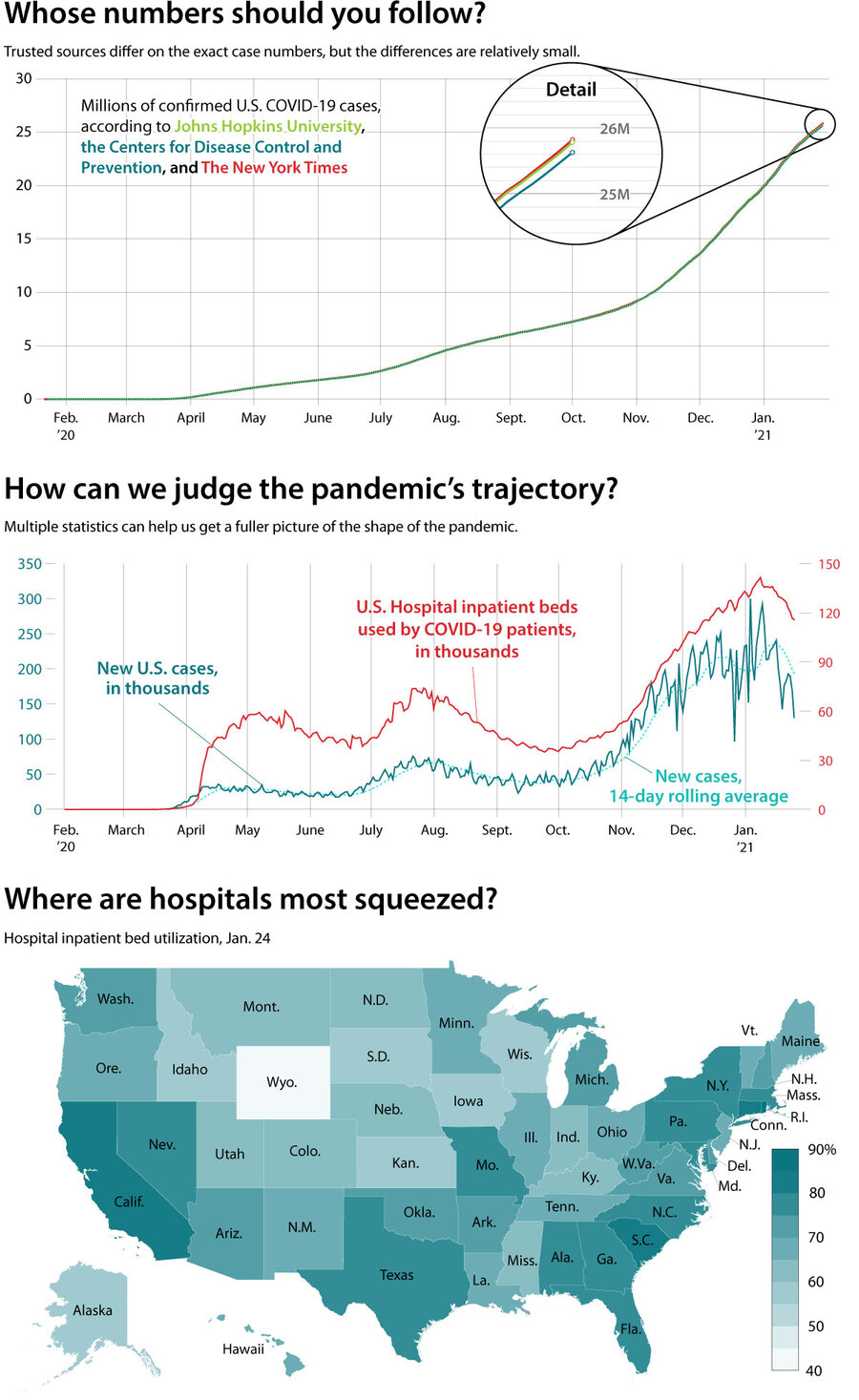

Today’s first story looked, in part, at pandemic data as a slightly moving target. We put together this visualization to show you where to get the fullest possible picture.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

Jacob Turcotte Graphics and Multimedia Director

With the rollout of vaccines, we have entered a more hopeful phase in the fight against COVID-19. But how does one make sense of the labyrinth of 14-day averages, hospitalization rates, positivity percentages, and caseloads?

People should approach the data as a “larger ecosystem,” says John Quackenbush of the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

Within that ecosystem, the fatality rate illustrates the severity of an outbreak. But since there’s usually a weekslong lag between infection and fatality, it’s also one of the least useful indicators in real time.

Hence the need for case counts and hospitalization rates, which speak more to the present. Although the number of cases in an area says little about how many people are experiencing symptoms, the trend in those cases shows whether the coronavirus is becoming more or less abundant.

In turn, hospitalization rates indicate the toll the virus is taking on the community. As a subset of that data, the number of intensive care admissions underscores the strain that an outbreak is placing on medical capacity.

Taken together each data set fills in gaps left by another, providing a fuller picture of how well a public health system is managing the outbreak.

Confused by pandemic data? Here’s some help reading it.

With the rollout of vaccines, we have entered a more hopeful phase in the fight against COVID-19. But how does one make sense of the labyrinth of 14-day averages, hospitalization rates, positivity percentages, and caseloads?

Step one is picking a reliable data source and following it throughout the pandemic.

“You need to know that [the data is] going to consistently give you the same kinds of information throughout the pandemic so that you make the right decisions when you need to,” says Lauren Ancel Meyers, professor of integrative biology at the University of Texas at Austin.

Though their numbers often vary slightly due to marginally different methodologies, The New York Times, Johns Hopkins University, and other data sources report consistent findings.

But even with a trusted data source, individual indicators of the pandemic’s severity can be difficult to parse. Case data, for example, always involves some amount of selection bias since the number of positive cases depends on the number of tests administered.

For that reason, people should approach the data as a “larger ecosystem,” says John Quackenbush, chair of biostatistics at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

Within that ecosystem, the fatality rate illustrates the severity of an outbreak. But since there’s usually a weekslong lag between infection and fatality, it’s also one of the least useful indicators in real time.

Hence the need for case counts and hospitalization rates, which speak more to the present. Although the number of cases in an area says little about how many people are experiencing symptoms, the trend in those cases shows whether the coronavirus is becoming more or less abundant.

In turn, hospitalization rates indicate the toll that virus is taking on the community. As a subset of that data, the number of intensive care admissions underscores the strain that an outbreak is placing on medical capacity.

Taken together each data set fills in gaps left by another, providing a fuller picture of how well a public health system is managing the outbreak. Watching multiple statistics at once allows a more holistic risk assessment.

SOURCES: Johns Hopkins University, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, New York Times, and Department of Health and Human Services

SOURCES: Johns Hopkins University, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, New York Times, and Department of Health and Human Services

As Ethiopia fills its Nile dam, regional rivalries overflow

A dispute over water resources in North Africa has key players posturing. What’s needed to achieve cooperation, and mutual benefit, is a shared acceptance of established facts.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

The Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam project is so important for the Horn of Africa country that it decided to finance the building of it by itself, after international lenders refused. The hydropower the Blue Nile dam will produce is critical in a country where more than half of the population is without access to electricity. But it’s not just about power of the electrical kind.

When talks about the dam broke down last month between Egypt, Sudan, and Ethiopia, it wasn’t about sharing water resources. It was a case of regional rivalries trumping understandings about science and cooperation.

The project is “a statement that Ethiopia is a significant, powerful country that can go at it alone and assert itself on the regional stage,” says Awol Allo, an Ethiopian analyst.

Egypt, 1,000 miles downstream and dependent on the Nile for fresh and irrigation water, views the dam as a national security threat. Sudan, which stands to benefit, is sandwiched between Egypt and Ethiopia and reluctant to anger either.

“For 50 or 60 years, Egypt was the biggest geopolitical actor” in the region, says analyst Rashid Abdi. Today, new governments “are becoming more assertive ... and acting independently,” he says. “It is a natural progression that Egypt is finding uncomfortable.”

As Ethiopia fills its Nile dam, regional rivalries overflow

When African Union-mediated talks between Ethiopia, Egypt, and Sudan over a Nile River dam broke down yet again last month, it didn’t mark a new disagreement over sharing vital water resources.

Rather, it was a case of regional rivalries trumping understandings about science and cooperation that have been laid out by African and Western mediators in multiple draft agreements.

Since then, Egypt’s media have sounded war drums, and a border territory dispute between Sudan and Ethiopia has erupted into violence.

At the center of the dispute is the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD), built by successive governments in Addis Ababa with the goal of pulling millions out of poverty.

The turbines of the dam, located near the source of the Blue Nile in northwest Ethiopia, are to generate 6,000 megawatts of hydropower – critical in a country where more than half of the population, some 50 million people, are without access to electricity, and demand for power is increasing by 30% annually.

The solution to Egypt and Sudan’s resulting water-security concerns, observers say, is simple: coordination and data-sharing.

Yet even amid indications that the revival of traditional American diplomacy could help resolve the dam dispute, observers say mediators must also confront currents stronger than the Nile itself: nationalism, territorial disputes, and a struggle over supremacy in the Horn of Africa.

Regional supremacy

For Ethiopia, the dam project promises to fuel the country’s ascendance as a geopolitical player. Even amid the struggle over the future of the country that last November erupted into war in Ethiopia’s northern Tigray region, the dam remains a cause that unites the diverse nation.

“There has been among the government and broadly the Ethiopian people a sense of unfairness, that as a poor country we have not been able to utilize a natural resource that springs out of Ethiopia,” says Awol Allo, an Ethiopian analyst and lecturer at Britain’s Keele University.

“This dam project signals the revival of the Ethiopian state after the decades of shame, poverty, and famine it has been identified with.”

A sense of personal investment and national unity around the dam solidified after the World Bank, International Monetary Fund, and other lenders refused to fund the GERD. Ethiopia in 2010 decided to go it alone, paying for it with government funds and bonds purchased by private citizens, and broke ground on the project in 2011.

“Every Ethiopian sees themselves as a stakeholder in a project that is not just about energy needs, but a statement that Ethiopia is a significant, powerful country that can go at it alone and assert itself on the regional stage,” Mr. Allo says.

Downstream drama

The draft agreements notwithstanding, the water-sharing disputes between Egypt, Sudan, and Ethiopia have only deepened since construction completed on the GERD in 2020 and Addis Ababa began filling the reservoirs in July.

Downstream countries long used to the unrestricted flow of the Nile for their farming and fresh water are alarmed by the dam’s potential impact on their water and food security.

Egypt, 1,000 miles downstream from the dam, has laid a historic claim on a lion’s share of water from the Nile and views GERD as a national security threat. Egypt currently depends on the Nile for 90% of its fresh water and the vast majority of irrigation water for crops to feed its 105 million citizens. It is also concerned with potential flooding and drought.

Egypt and Sudan decry the lack of technical studies and assessments of the dam’s environmental and social impact downstream.

Tensions are now high as Addis Ababa is set to fill the dam’s reservoir with an additional 11 billion cubic meters this year after the initial 4.9 BCM it filled in July 2020. The dam has a total capacity of 74 BCM. “The biggest problem is not knowing how Ethiopia intends to use and operate the dam, what times of year, what quantities, and what will be the impact,” says Amal Kandeel, an environmental and policy consultant and former director of the Climate Change, Environment and Security Program at the Middle East Institute. “Downstream countries can’t plan without knowing; they need clarity.

“Egypt will not benefit from the dam,” she says. “But if there is coordination, facts, evidence, and data shared transparently at the minimum, any potential harm will be reduced.”

For Egypt, a “humiliation”

Egypt’s inability to stop or influence the project has become a symbol of the government’s inward-looking focus the past decade and its withdrawal from the Arab and African stage, which domestic critics say has dramatically reduced Egypt’s geopolitical significance.

Egyptian insiders privately say the prospect of Ethiopian control over the most populous Arab country’s water and food security is viewed as “a humiliation,” driving Cairo’s hard line.

“For 50 or 60 years, Egypt was the biggest geopolitical actor, not only in the Middle East, but the northeast Horn of Africa as well,” says Horn of Africa analyst Rashid Abdi.

“Times have changed, you have new governments that are becoming more assertive on the regional and world stage and acting independently,” he says. “It is a natural progression that Egypt is finding uncomfortable.”

Egypt has pushed for intervention by the United States, its Arab allies, and the U.N. Security Council. In June, Foreign Minister Sameh Shoukry warned of conflict should the United Nations fail to intervene.

After the talks’ breakdown last month, Egyptian state-influenced media clamored for the use of “force” against Ethiopia, advocating surgical strikes on the GERD’s electricity infrastructure.

For Sudan, it’s good, but ....

Meanwhile, regional alliances and a century-old border dispute have transformed Ethiopia’s northwest neighbor from a quiet supporter of the dam to a spoiler.

Observers and experts agree: The GERD’s benefits for Sudan are many.

The dam, 20 miles from the Sudan-Ethiopia border, will reduce flooding that has devastated Sudan in the past. Blue Nile flooding destroyed one-third of cultivated farming land in the country last year, destroying 100,000 homes and killing 100 people, deepening Sudan’s economic crisis.

The reduction in flooding and sharing of irrigation water would help Sudan cultivate more than 50 million hectares of arable land abandoned due to flooding and mismanagement, a critical boost to an agricultural sector that is Sudan’s largest employer and accounts for 30% of the country’s gross domestic product.

Ethiopia has also vowed to export cheap electricity to Sudan.

“Honest people in Khartoum will tell you that the dam is a net positive from all logical, logistical, and economic perspectives. Objectively, Sudan would benefit from the dam,” says Jonas Horner, Sudan analyst and deputy director for the Horn of Africa at the International Crisis Group.

“But it is not quite as simple as that,” he says, pointing to Sudan’s need to balance regional alliances.

Khartoum – militarily close to Egypt, diplomatically indebted to Ethiopia, and financially and politically dependent on Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, who are allied with Egypt – is reluctant both to appear to support the dam, on the one hand, or come down hard on Addis Ababa, on the other.

This complicated balancing act was disrupted in December by the violent reignition of a century-old Sudan-Ethiopia border dispute.

Sudanese patrols have come under shelling allegedly at the hands of Ethiopian militias, and the Sudanese army and Ethiopian federal forces have clashed multiple times this month.

Ethiopian officials blame Cairo for stoking the tensions, alleging an Egyptian plot to prolong conflict and derail the GERD’s completion.

Traditional American diplomacy

Observers agree the dispute provides an opportunity for the Biden administration to demonstrate its vowed return to traditional American diplomacy.

The Trump administration’s few forays into the GERD dispute favored Egyptian President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi, a Trump ally. Last July the Trump administration partially suspended American assistance to Ethiopia after Addis Ababa rejected a draft agreement compiled by Washington that it saw as heavily favoring Cairo. President Donald Trump publicly warned that Cairo would “blow up that dam” should talks fail.

In contrast, President Joe Biden’s secretary of state, Antony Blinken, vowed in his confirmation hearing last month to conduct “active engagement” to address a rise in tensions that “has the potential to be destabilizing throughout the Horn of Africa,” indicating that he is considering appointing a special U.S. envoy for the Horn of Africa.

But observers caution that the Biden administration must untangle the web of regional politics, nationalist fervor, and power plays in order to get the three states back to the basics: water.

“The war in Tigray has created instability in the Ethiopian state, and now you have the border issue with Sudan that is clearly linked to the GERD issue. You have domestic actors in each of these countries lobbying external actors to advance their interests,” says Mr. Allo.

“It will be difficult for any U.S. administration with all the goodwill in the world to mend things.”

Difference-maker

He grew up wanting for nothing. Now he gives other students a leg up.

You may know young adults who practice deep introspection about privilege. Meet one who’s actively shifting perceptions about people experiencing homelessness.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

-

By Chandra Thomas Whitfield Correspondent

Helping the Homeless Colorado helped raise more than $130,000 for basic necessities. And who was behind it?

Teens.

The nonprofit began as a group of friends passing out care packages on the weekend. And during the pandemic, they’ve pivoted to focus on education, supporting students living in poverty – particularly those in unstable housing. For the teens behind the initiative, it’s personal.

“In my calculus class of 30 [students] senior year, there very well could have been four or five students who were either going to be sleeping in a car, going to a shelter, or staying with a friend, just because they didn’t have a home of their own,” says Matine Khalighi, a 19-year-old who has helped spearhead the efforts for several years. “But when I’m sitting next to them, nobody knows.”

In 2019, Mr. Khalighi and many of his classmates learned that their own school’s valedictorian had experienced homelessness – which they only found out during her graduation speech.

Now, the goal is to start youth-led clubs at other schools, with an emphasis on breaking stereotypes about homelessness.

“Homelessness is not part of someone’s personality,” says Mr. Khalighi. “It’s just a phase that they’re going through. So, I like to say ‘people experiencing homelessness.’”

He grew up wanting for nothing. Now he gives other students a leg up.

Five years ago, Matine Khalighi was living a comfortable life near Denver. The son of an emergency room doctor dad and a clinical pharmacist mom, the 14-year-old honors student wanted for nothing. Like many teens, he’d found himself yearning to better understand the world, how it worked, and why certain things were the way they were.

In particular, he wondered why his life seemed so dramatically different from that of the people he’d often see asking passersby for money, food, and shelter.

He recalls riding home from cross-country running practice and seeing people asking for help. “I’m living this life where I’m going home to have dinner and there’s this person just sitting out there holding a sign,” recalls Mr. Khalighi, who turned 19 in January. “And I’m like, ‘why is that OK,’ especially in the United States, which is supposed to be one of the wealthiest and best places on earth to live, that so many people are living in poverty?”

And so, at 14, an age when many teens are preoccupied with their own experiences, he set out to better understand the circumstances of others and to explore difficult questions about privilege, access, and inequality in society.

Some of the answers he sought came when he enrolled in a community service class at Campus Middle School in Greenwood Village, Colorado, where he and his classmates raised money for children in the foster care system. Helping out felt good, he says. The project also opened up his eyes to the great need that existed among people experiencing homelessness in Colorado.

That first school project lit a fire in him and he felt that he had to do more to help. So what began as an informal group of friends passing out care packages to those in need in downtown Denver on weekends evolved in 2016 into a youth-led nonprofit, Helping the Homeless Colorado, which helped to raise more than $130,000 to provide basic necessities. More than 25,000 people engaged with the group’s 2019 #SpreadTheLove campaign, which invited Coloradoans to share, with permission, photos and videos of themselves talking with someone experiencing homelessness.

“This is truly a student-run operation and they have managed to pull this all off magnificently,” says Donald Burnes, a former Helping the Homeless Colorado board member. “They all deserve a great commendation and many cheers,” he says.

Finding focus

In the fall of 2019, Mr. Khalighi and his team of student volunteers decided to step back from their work and revamp the organization. Last June, after months of huddling in person – and later virtually due to the pandemic – to brainstorm about strategic planning, fundraising, and coalition building, they came up with a new plan. To help more young people, the team renamed the organization EEqual and shifted its focus to the educational needs of students living in poverty, particularly those in unstable housing.

The organization has since raised and distributed $15,000 in college scholarship grants for students grappling with homelessness.

There are an estimated 1.5 million homeless students in the U.S., of which about 23,000 are in Colorado. Mr. Khalighi says he and his cohorts strongly believe that investing in education is one of the most effective ways to help break the cycle of poverty.

“In my calculus class of 30 [students] senior year, there very well could have been four or five students who were either going to be sleeping in a car, going to a shelter, or staying with a friend, just because they didn’t have a home of their own,” says Mr. Khalighi. “But when I’m sitting next to them, nobody knows. Nobody talks about that because we’re all taught not to talk about money and stuff, which is understandable, but [because we don’t] it’s so easy for them to fly under the radar. I think the worst part is the stigma.”

Mr. Khalighi says he and many of his classmates were shocked to learn that the 2019 class valedictorian had been homeless, something they only found out when she shared her experience in her graduation speech.

“Afterwards, I was like, ‘Oh my gosh, we have to talk. Like, you’re literally the kind of people we’re trying to serve,’” he says. “Later, we ended up talking [about her experience] on the phone and I learned a lot.”

Valuable work

Mr. Khalighi’s efforts have earned him a long list of honors. He won the President’s Volunteer Service Award three times, and was a TEDx speaker and a leader in the global Ashoka Young Changemakers program. This past spring he was honored with the Prudential Spirit of Community award and the Gloria Barron Prize for Young Heroes, which included a combined donation of $12,500 to EEqual. Last year he was admitted to Harvard University, which he delayed by a year so he could focus on EEqual.

One EEqual college scholarship recipient, who requested that her name be withheld to protect her privacy, says she can attest that the nonprofit is living up to its mission. “The organization made a difference [in my life] by removing the stress of trying to figure out how I would pay for my tuition,” explains the student now enrolled in Arapahoe Community College in Littleton, Colorado. She says she has been living in a motel for the past few months. “[Their help] also reminded me that there are people out there who want to see someone succeed on achieving their goals as a student.”

The student communicates regularly with Mr. Khalighi by phone and email and says she is constantly amazed by the work that Mr. Khalighi and his fellow youth leaders carry out so selflessly.

“His organization is important because it brings awareness to the society we live in,” she says. “It focuses on the struggle homeless students go through, that not all homeless people are drug addicts, have mental illness, or [are] a threat. This organization helps to bring understanding that [people experiencing] homelessness come from all different backgrounds.”

Mr. Burnes, who is the co-founder of the Burnes Institute for Poverty Research at the Colorado Center on Law and Policy, praises the passion and dedication Mr. Khalighi and his peers bring to their work. “This is very, very important and valuable work, and it provides some gifted but needy students a real opportunity to overcome financial hardship and some systemic discrimination,” he says.

Looking ahead

Mr. Khalighi plans to start at Harvard in the fall. Before he goes, he hopes to have laid the foundation for the organization to begin running youth-led clubs at a handful of middle and high schools in the metro-Denver area. The aim will be to educate young people about homelessness, with an emphasis on breaking stereotypes and combating misinformation.

“Like it’s not ‘homeless people,’ because homelessness is not part of someone’s personality,” he says. “It’s just a phase that they’re going through. So, I like to say ‘people experiencing homelessness.’”

The ultimate goal is to expand EEqual programming to more schools across the Rocky Mountain state and eventually nationwide.

“Oh, my gosh, education, it’s everything, so like, why wouldn’t we invest in it?” says Mr. Khalighi. “I think it’s the solution.”

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Why coups matter less in Myanmar

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

The last time she was put under arrest by Myanmar’s military for promoting democracy – from 1989 to 2010 – Aung San Suu Kyi found she had to learn that her enemy was not the military. “Fear is the first adversary we have to get past when we set out to battle for freedom,” she later said in a lecture. Her detention again on Feb. 1 in a military coup has once more evoked a similar spirit of strength.

She sent a message to the 54 million people of her Southeast Asian country that they should simply not “accept the coup.” She asked them to express nonviolent dissent.

The message itself shows why “the lady,” as she is widely known, remains so popular. Unlike the military’s claim that the people are morally bound to obey it, her legitimacy rests on her call for individual self-governance expressed in a pluralist democracy.

While the coup leaders claim an election will be held within a year, democracy promoters not under arrest will likely follow Ms. Aung San Suu Kyi’s advice. She asked them to rely on their “inner resources” of being free and awaken the thought of army generals.

Why coups matter less in Myanmar

The last time she was put under arrest by Myanmar’s military for promoting democracy – from 1989 to 2010 – Aung San Suu Kyi found she had to learn that her enemy was not the military. “Fear is the first adversary we have to get past when we set out to battle for freedom,” she later said in a lecture. And, as many democracy fighters have discovered, she added that “we have the right to be free from the fear.”

Her detention again on Feb. 1 in a military coup has once more evoked a similar spirit of strength. She sent a message to the 54 million people of her Southeast Asian country that they should simply not “accept the coup.” She asked them to express nonviolent dissent through street demonstrations.

The message itself shows why “the lady,” as she is widely known, remains so popular. Unlike the military’s claim that the people are morally bound to obey it, her legitimacy rests on her call for individual self-governance expressed in a pluralist democracy. Despite the military’s strong hand in government and the economy, she asks citizens to “live like free people in an unfree nation.”

Since Myanmar’s independence in 1947 – when it was known as Burma – the military has either held power or, as in recent years, controlled a limited democracy behind the scenes. It asserts the army best represents the legacy of the country’s founding father, Aung San, a general killed in 1947 while fighting for independence from Britain and the father of the woman who now casts doubt on that claim. She says the way to honor her father’s legacy is to build a “real democratic nation,” although she herself lost some of her international luster after defending the military’s violent suppression of the minority Rohingya.

The latest coup reflects Myanmar’s ongoing struggle for defining legitimacy in government – whether it is freely granted or forced by those with guns claiming to be patriotic guardians of national unity. Since 1988, when a democratic uprising began, the people have slowly shifted against the military. In parliamentary elections last November, Ms. Aung San Suu Kyi’s party, the National League for Democracy, won in a landslide in a surprise to the military. After weeks of disputing the vote count, the generals reverted to strong-arm tactics and took power by force.

While the coup leaders claim an election will be held within a year, democracy promoters not under arrest will likely follow Ms. Aung San Suu Kyi’s advice and not resort to open conflict. She asked her party members to rely on their “inner resources” of being free in their own thought and working to awaken the thought of army generals. “Whatever mistake they have made in the past, we need to give them the chance to change, instead of seeking revenge,” she once told the National League for Democracy. Even for the most hardened coup-maker, she expects a realization of self-governance.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Blessings of a no-blame mindset

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 4 Min. )

-

By Joan Bernard Bradley

Avoiding harshly blaming others not only keeps our peace from being taken from us but contributes to a more peaceful world.

Blessings of a no-blame mindset

When our well-laid plans fall apart, it can be easy to blame others for any disappointment we might feel. But is this a worthwhile approach to take?

Blaming others often includes anger – a state of thought that isn’t natural to any of us as the offspring of God, made in the image and likeness of divine Spirit. On the other hand, a state of thought that is Godlike includes forgiveness, brotherly love, and kindness – qualities that have their source in Spirit – and the Apostle Paul exclaims “to be spiritually minded is life and peace” (Romans 8:6).

The Bible has many examples of individuals who chose spiritual-mindedness over a blame mindset. One of my favorite biblical role models is Daniel, who, even in the face of a conspiracy against him that resulted in a life-threatening predicament, did not blame the individuals responsible (see Daniel 6). Instead, he focused his spiritual energies on continuing to worship God with all his heart, and therefore maintaining his innocence. He trusted deeply that God’s power and loving care were present to save him from harm, and proved that this was true.

When I worked as a team leader for a special project, my colleagues and I worked diligently to complete the assigned tasks. Despite our successes, personality conflicts surfaced frequently and caused divisiveness and unhappiness.

I prayed daily to know that God’s law of harmony was governing the entire project, yet discord persisted. Then one day, a team member told me confidentially that one individual was deliberately stoking discord and division. At that point I felt I knew what was really going on; in other words, I now knew who was to blame.

Without realizing it, I had adopted a blame mindset, which was contrary to the spiritual-mindedness that I was striving to cultivate in daily living. Since no solutions were forthcoming, I prayed that God would lead me to serve where I could be a blessing and feel blessed. When a new job opportunity presented itself, I gratefully accepted it and moved on.

Leaving the organization did not automatically result in a sense of peace, but it felt easier to pray about the blame I had been harboring. As I prayed, it became clear that blaming others meant that I was believing that there was a power opposed to the one infinite and all-good Mind, or God, that conceived and governs all creation. Also, that I was believing that I and others were merely mortal and material beings with mortal minds of our own, separate from God, and could therefore be inclined to be divisive and discordant.

Through my study of Christian Science, I knew that freedom from this false sense would come only by sincerely accepting the spiritual fact that because God created man (each one of us) as His exact reflection, then my real nature and that of everyone else was indeed spiritual and Godlike, expressing God’s.

As I pondered Mary Baker Eddy’s inspired answer to the question “What is man?” in the Christian Science textbook, “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” this line became very special to me: “Man is idea, the image, of Love; he is not physique” (p. 475). Deep contemplation of what it means to be God’s loved spiritual idea made me feel embraced in divine Love’s ever-presence.

I felt too that I had glimpsed the significance of Christ Jesus’ command to love others as ourselves (see Matthew 22:39), and so I cherished a sense of genuine brotherly love and forgiveness toward everyone. I was no longer entertaining unproductive thoughts that tended to blame others.

Some time later, I was scheduled to give a presentation in another city, and when I arrived at my destination, I learned that one of my former teammates would be attending the event. I was delighted to receive a warm welcome note from her. She even invited me to visit with her afterward. We hugged each other warmly, and shared many good memories. There was no mention of any unhappiness, and we continue to be in friendly contact today. To me, this was evidence that I was expressing a more Christlike state of thought, which was free from any unproductive thinking.

The blessings of a “no blame” mindset are truly liberating and peace-giving. This kind of thinking is an expression of spiritual-mindedness that radiates Christly love to all. It also gives the satisfaction of contributing to one of Christianity’s central purposes – that of bringing peace on earth, and goodwill toward men.

Some more great ideas! To hear a podcast discussion about the all-knowing nature of God, and what this means for our memory, our safety, and even healing, please click through to the latest edition of Sentinel Watch on www.JSH-Online.com titled “Omniscience: What God knows, you can know.” There is no paywall for this podcast.

A message of love

A leader behind bars

A look ahead

You’ve probably read a lot about last week’s seriously quirky stock market story: Small investors took on hedge fund giants who were betting against the success of a company called GameStop. To us it’s a story with some much deeper themes. Watch for that later this week.

We’re also watching Myanmar. Beyond the news, we’ll be looking at how it’s a test case for the U.S. in advancing democratic values.