- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 8 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- ‘Exhausted.’ A year into pandemic, working moms see help on horizon.

- A 9/11 Commission for Jan. 6? Possible, but harder this time.

- Post-pandemic, will the world think big, or just get by?

- Syria, after 10 years of conflict: No war and no peace

- ‘Klara and the Sun’: Do androids dream of human emotions?

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

‘Clean slate laws’: Second chances for America’s ex-convicts

If you have a criminal record, it often follows you through life.

It makes it harder to get hired, rent an apartment, or get into college. If your job application includes a check mark next to “criminal record,” research shows that you are half as likely as other job seekers to get a callback from an employer.

But a growing number of states now consider such a life sentence – well beyond time served – as unjust. Next month, Michigan will begin to selectively and automatically expunge the records of some felons and those convicted of misdemeanors. It joins six other states passing “clean slate” laws making it easier for people to get a fresh start. No, this doesn’t include violent crimes such as murder and rape. And in Michigan there are still waiting periods of up to seven years after prison release before the slate can be wiped.

But in cities like Detroit, where one-third of residents have felony or misdemeanor convictions, Axios reports, expungement can pave the way to better jobs and restored dignity. One study found that on average, wages rise by more than 20% just one year after someone’s record has been cleared.

Abraham Lincoln reportedly said, “I have always found that mercy bears richer fruits than strict justice.” And this emerging bipartisan trend toward second chances suggests moral progress, and that America may be gradually embracing a higher sense of justice.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

A deeper look

‘Exhausted.’ A year into pandemic, working moms see help on horizon.

Women, especially working moms, have borne the brunt of this economic downturn. But there may be a silver lining as corporations and governments move to address long-standing problems.

The pandemic has swamped many working mothers. Already struggling to balance the demands of work and home, they were suddenly confronted last spring with having to add all-day child care and education monitoring to their long list of duties.

The result? “The first word that comes to mind is exhaustion,” says Aleka Bilan, a working mom in Bend, Oregon.

The challenges were felt so broadly that companies and politicians began to pay attention. Some corporations are reexamining their paid sick leave and flexible work policies. Business groups such as the U.S. Chamber of Commerce and the Business Roundtable want to target federal funds for child care.

The Biden administration and Republicans in Congress are pushing rival legislation that would help families pay for child care, extend or increase unemployment benefits, and provide funding to fully reopen schools.

Says Betsey Stevenson, an economic policy expert at the University of Michigan: “We're certainly having the conversation that we've needed to have for a very long time.”

‘Exhausted.’ A year into pandemic, working moms see help on horizon.

The pandemic has produced a moment of clarity in the United States about a crisis that has been building for decades: The tradeoffs many working mothers routinely face are becoming unsustainable as the lockdowns reach the end of their first year.

Already stretched thin balancing the demands of work, housework, and child care, these women now face the extra demands posed by homebound children struggling to learn via online classes and the need to care for parents or family members who may require extra support during the pandemic.

The silver lining is that working mothers’ plight, a longtime problem, is finally coming to light. The Biden administration and Republicans in Congress are pushing rival legislation that would help families pay for child care, extend or increase unemployment benefits, and provide funding to fully reopen schools. Companies are reexamining their paid sick leave and flexible work policies. Business groups such as the U.S. Chamber of Commerce and the Business Roundtable want to target federal funds for child care.

“There’s been more interest from lawmakers in the last six months than in the last 20 years,” says Sue Renner, executive director of the David & Laura Merage Foundation, which supports back-office services to child care providers in six states.

Advocates are optimistic that the attention will lead to action, in part because some companies have already made moves to be more mom-friendly, and because the interest in Congress is coming from both sides of the aisle.

“This is something where Democrats and Republicans can put behind some of the things they have been fighting over and focus on something American families need,” says Betsey Stevenson, professor of public policy and economics at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. When the pandemic first hit and schools closed, “politicians’ first question was: ‘How do we keep the airlines flying?’ ... There was just radio silence on what this whole thing means for our children. [Now] we’re certainly having the conversation that we’ve needed to have for a very long time.”

The road to this potential policy moment has been anything but easy for families, and especially for mothers.

“The first word that comes to mind is exhaustion,” says Aleka Bilan, an academic coach and mother of two from Bend, Oregon.

For Lori White, a single mom in Nashua, New Hampshire, the low point came last spring after she was furloughed from her teaching job and had to fight the bureaucracy for a month and a half before getting unemployment benefits. “It’s just one of those [situations] when you want to lean out the window and scream.”

Between February and April last year, 3.5 million adult women left the labor force and despite a growing number of jobs, two-thirds of them have yet to return. That workforce erosion has been significantly greater for women than for men.

An already fragile system

In fact, a smaller share of women are now working or looking for work than at any time since 1988, according to a new report from the National Women’s Law Center in Washington. And the recovery has been slower for mothers. A new study from the National Bureau of Economic Research finds that if women with school-age children had experienced a recovery similar to women without children, 700,000 more of them would now be part of the labor force.

The reason for all this is that the pandemic’s economic storm has battered the already fragile infrastructure that allowed women to work and care for children in the first place.

For starters, the lockdown-induced recession decimated jobs. Previous downturns were hardest on goods-producing industries, where men predominate, but last spring’s lockdowns affected service industries the most, especially sectors where women predominate, such as leisure and hospitality.

“So many of those service jobs were the first to go,” says Brent Orrell, a resident fellow at the right-leaning American Enterprise Institute (AEI). “And they’ll be among the last to really come back. And there’s some question if they’ll ever come back.”

Another piece of the working-mom infrastructure hit hard by the pandemic is child care. Last spring’s lockdowns temporarily closed a third of day care centers, and by December there were still 13% fewer open than a year earlier, according to a new report by Child Care Aware of America, an advocacy group. The challenge is that these operations, often poorly financed, are now struggling with higher disinfecting and other costs and lower attendance. Over half of those open are losing money, according to a December survey by the National Association for the Education of Young Children. Four in 10 operations have taken on debt to make ends meet.

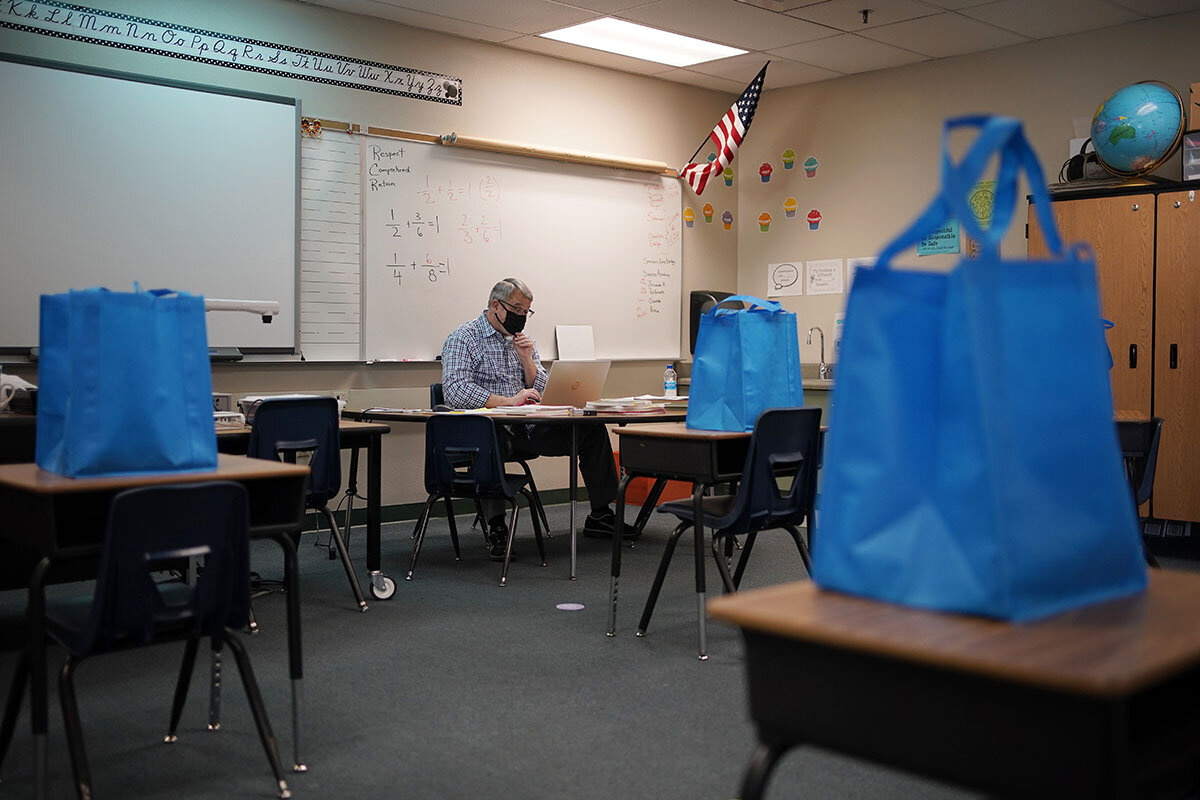

The closing of schools also hurt working parents, because suddenly a parent had to be home and supervising online learning. Most often that burden fell to mothers. When Ms. Bilan had some appointments with one of her children last year, she asked her husband to work from home and supervise the other child. “He lasted a day,” she recalls. “He’s wonderful and he’s great. ... [But] he was just like: ‘Oh no! I can’t do that again.’”

“I didn’t have a choice”

The younger the child, the more intensive the supervision had to be.

Online preschool “is a joke,” says Lindsey Dillon, a mother of two in Norwood, Massachusetts, and senior marketing manager for a sustainability nonprofit. Children competed with each other to make the loudest noise over the computer or the silliest face, she says. “It’s not conducive to working from home. Unfortunately, I didn’t have a choice.”

During the pandemic, everything got more complicated. Ms. Dillon gave birth to her second child, took maternity leave, came back to work just as her new daughter started day care, and had to find a new preschool for her 3-year-old son because of behavioral issues. That was her low point.

“I know I’m lucky and I have to keep reminding myself that a lot of people have it far worse,” she says. But “you can’t ignore the need for parents to have adequate child care. It’s imperative to have that addressed in order to get the economy back up to where it was.”

The pandemic has been particularly hard on women of color. “The racial implications of the economic downturn are really clear,” says C. Nicole Mason, the first Black president and chief executive officer of the Institute for Women’s Policy Research, a Washington think tank. “I’m a single mother and have 11-year-old twins who just began middle school and I work full time. It’s been really tough to manage virtual learning and a 40- to 50-hour work week. But I feel very fortunate. ... I didn’t have to leave the workforce. But many other women did.”

Wide gaps by race and occupation

An estimated 22% of Black mothers left their jobs during the pandemic, closely followed by Asian mothers at 20%, and Hispanic mothers at 19%, according to a survey of more than 1,500 mothers by The Mom Project’s research arm, WerkLabs. By comparison, only 12% of white mothers reported leaving the workforce.

One reason for that gap is that Black and Hispanic women are more likely than their white counterparts to hold front-line jobs that can’t be performed at home. They’re also more likely to be single moms. Twice as many Black moms reported doing more than 90% of household work compared with white and Asian moms, the WerkLabs survey found.

The time away from work will mean lower lifetime earnings and, potentially, reduced opportunities for advancement for mothers. For Linda Overbay, a Seattle mother with two teens, it has meant a year delay in starting her new business. In January 2020, just as the first U.S. coronavirus case was confirmed in Washington state, she coincidentally gave notice at her physical therapy job to start out on her own. Soon after, concerns over the virus put a stop to that and she became a nonworking mom while her husband, an architect, worked from home.

She had to increase her vigilance, she says. “I was monitoring the websites of the school, news, communications from the schools and clubs; I was monitoring the workload of the kids. ... I definitely learned to monitor my own needs better. In the past I might work myself to exhaustion and then look for support. [After the pandemic hit] I left more space in my own workload and I allowed myself to decompress a lot more.” She plans to open her business this spring.

New support on the way?

In the nationwide search for solutions, reopening schools has taken on rising urgency for policymakers and citizens alike in recent months – although the trend toward hybrid or partial reopenings so far hasn’t provided much of a fix.

Child care is one area where Democrats and Republicans both want to commit federal funds. This weekend, the House passed the Biden administration’s $1.9 trillion rescue package, which includes $15 billion in block grants so states can help low-income families make child care payments. It also would expand the child tax credit and offer aid directly to child care providers.

The bill’s shape is being guided by Democrats, but some GOP senators have been seeking to put a focus on the issue. Ten of them have supported offering $20 billion for low-income families with children up to age 12 to help pay for child care expenses. Utah Sen. Mitt Romney, a Republican, is proposing sending all but the richest families a monthly payment of $250 to $350 per child under 18, leaving parents to decide how to spend the money.

“Let people self-manage this with some extra resources,” says AEI’s Mr. Orrell, whose own proposal would expand current programs that allow states to give monthly payments to the unemployed to help them train for new and better jobs. “Maybe they have other needs that are not training: car repairs, transportation. Maybe they need child care.”

Others argue that affordable, high-quality child care is a right that all families should have access to. “Some of the lawmakers are looking at providing child care and the support to child care for only the poorest, and we say: ‘Wait a second, the majority of this country is middle class,’” says David Merage, the founder of the Merage Foundation. He urges a public-private partnership that would make child care available to everyone.

Corporations have a role to play, says Kristin Rowe-Finkbeiner, chief executive of MomsRising, a policy and activist group. “Employers are changing their policies [for working women] not only because it’s the right thing to do but also because it’s the smart thing to do.” Research shows it increases employee retention and makes it easier to recruit top female talent.

“Employers like Microsoft and Google have great policies,” Ms. Rowe-Finkbeiner says. “But a lot of people don’t work at Microsoft or Google.”

That’s why she is pushing for more government support of child care. A new bill in Massachusetts, which would provide child care at the state level for families with less than half the median income, is garnering support from business groups.

Paid sick leave is another top demand of working mothers’ advocates. The pandemic caused Congress last year to pass legislation mandating that even small companies offer paid sick leave for workers who were diagnosed with COVID-19, were caring for family members diagnosed with COVID-19, or were taking care of children whose child care was no longer available or whose school had closed. But the law had a sunset provision for the end of 2020.

Some large companies, like Levi Strauss, have started offering paid sick leave. Other employers will need a nudge from federal legislation to begin offering it, says Ms. Mason of the Institute for Women’s Policy Research. She’s optimistic that Washington, having become aware of the crisis, will act.

“This is a moment unlike many others,” she says. “All engines are firing at 100%. There’s great momentum at the federal level.”

A deeper look

A 9/11 Commission for Jan. 6? Possible, but harder this time.

Amid diverging narratives about the attack on the U.S. Capitol, five key players from the bipartisan 9/11 Commission told us that their experience offers relevant lessons for how to establish facts and win public trust.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 8 Min. )

Two months after rioters breached the U.S. Capitol, many questions about the Jan. 6 attack remain unanswered. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi has called for “an outside, independent 9/11-type Commission” to determine the facts and causes of the attack.

The 9/11 Commission, against significant odds, produced a unanimous report and saw nearly all of its 41 recommendations implemented, including a massive reorganization of U.S. national security. So far, the prospects for establishing a similarly bipartisan commission to investigate Jan. 6 appear even more daunting, with Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell throwing cold water on the idea and Speaker Pelosi initially proposing an 11-member commission with only four Republicans.

Still, five people who worked on the 9/11 Commission say it’s possible to replicate that model. The key is finding people who will put country above party.

“People tell me, ‘You can’t find 10 people who would put the country first.’ It’s nonsense,” says former New Jersey Gov. Tom Kean, who chaired the commission. “It’s a huge country and as long as the appointing authorities are looking for those type of people, I’m sure they’d find many, many of them – many of whom would be anxious to serve their country.”

A 9/11 Commission for Jan. 6? Possible, but harder this time.

When the 9/11 commissioners first got together for dinner, amid lingering partisan bitterness in the wake of the 2000 Bush-Gore recount, the chairman arranged the seating so it went Democrat, Republican, Democrat, Republican.

Jamie Gorelick, the former No. 2 in the Clinton Justice Department, found herself sitting next to Slade Gorton, who had served as a Republican senator and attorney general of Washington state.

After the two lawyers talked for a while, Ms. Gorelick told Senator Gorton that her Democratic friends had warned her to watch out for him, because he was highly partisan. “Funny,” she recalls the late senator responding. “My Republican friends told me the same thing about you.”

“And that was the beginning of a really good friendship,” says Ms. Gorelick in a phone interview. Mirroring the leadership of Chairman Tom Kean and Vice Chairman Lee Hamilton, they became a backbone of bipartisan cooperation on the commission, which went on to produce a unanimous report and saw nearly all of its 41 recommendations implemented.

Now that commission is being held up as a model for an investigation into the Jan. 6 attack on the U.S. Capitol. On Feb. 15, after the Senate acquitted former President Donald Trump of inciting the riot as Congress met to certify the Electoral College results, House Speaker Nancy Pelosi announced that Democrats’ next step would be to establish “an outside, independent 9/11-type Commission” to report on the facts and causes of the attack.

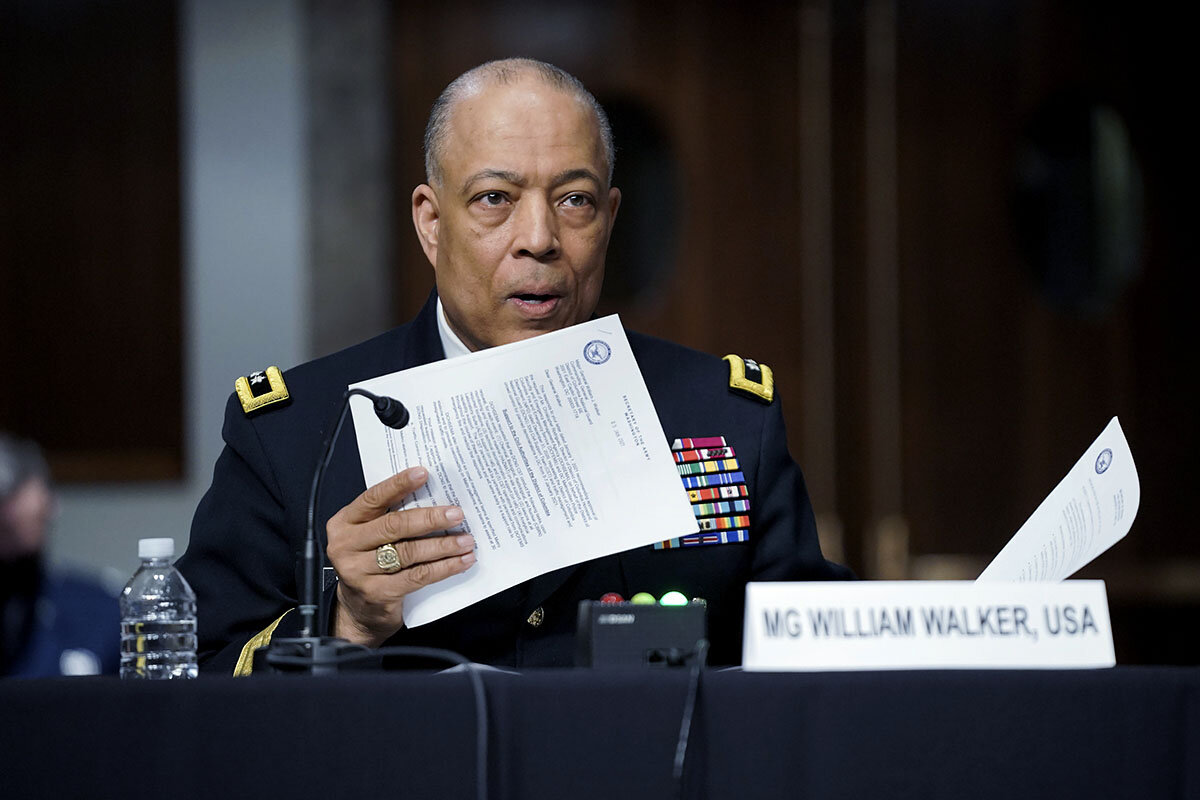

Many facts relating to the events of Jan. 6 remain unclear, with not a single Capitol Police media briefing to date and relatively little public information from the FBI or other law enforcement agencies. A joint Senate committee last week questioned top leaders in charge of Capitol security, who resigned in the wake of the attack, and the committee met again on Wednesday to hear from top officials from the FBI and the Department of Homeland Security.

Yet there are far greater hurdles to establishing a 9/11-style commission today – first and foremost being the intensified partisan atmosphere. The domestic nature of the Jan. 6 attack, in contrast with a foreign Al Qaeda plot, could also make it harder to create a unified approach. Since it occurred at the Capitol, party leaders themselves could be blamed for not ensuring better security, making the political stakes much higher. Indeed, while there was always the likelihood that the 9/11 Commission could reflect badly on the Bush administration, detailing how it failed to foresee and forestall Al Qaeda’s plot, House Democrats have already impeached former President Trump for inciting the Jan. 6 attack.

And early maneuvering has not indicated as strong a commitment to bipartisan investigation as with the 9/11 Commission, half of whose members were Democratic appointees and half Republican. Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell has thrown cold water on the whole idea. Speaker Pelosi has proposed a commission of 11 members, just four of whom would be Republicans. Other Democrats in Congress have called for a more balanced partisan representation.

Still, despite all the apparent obstacles, five key players from the 9/11 Commission interviewed by the Monitor each said they believed it would be possible to establish a similarly effective bipartisan group to investigate the Jan. 6 attack and establish a factual accounting.

The commission would need to have a clear mandate and limited scope, focus on fact-finding, and be given the time and resources to do a thorough job. The most important thing, they emphasized, would be finding the right people. People with sterling reputations. People who will respect each other. People who are looking for solutions.

“If there’s even one person on the commission ... who isn’t willing to put country above party, it’s not going to work,” says former New Jersey Governor Kean, the Republican who chaired the 10-member commission.

“There are all kinds of commissions in Washington; they form them every day,” adds Mr. Hamilton, the former Indiana congressman who was the commission’s vice chair. “But the ones that really have impact are ones that are genuinely bipartisan.”

A slow start

To be sure, the 9/11 Commission was not without its controversies. Despite the collective shock of 9/11, and the national push for answers and accountability, it took more than a year for Congress to pass a bill establishing the commission. Some involved were criticized for perceived conflicts of interest. Its work was slow, culminating nearly three years after the attacks.

Governor Kean was perhaps an unorthodox choice to chair the group. The Republican had comparatively little experience in the realm of intelligence and national security. But he knew something about bipartisanship. When he became New Jersey governor, both chambers of the state Legislature were controlled by Democrats. He had also chaired a national wetlands commission, bringing parties ranging from oil interests to environmental groups into agreement.

Mr. Hamilton, the vice chairman, had led the House Committee on Foreign Affairs for years. Mr. Kean told him right off the bat that everything they did, they would do together.

When “Meet the Press” host Tim Russert called the new chairman and invited him on his show the following week, Mr. Kean agreed, but said he’d appreciate it if Mr. Hamilton could join him. He recalls Mr. Russert responding that guests don’t pick guests in Washington. “I said, ‘OK, then get somebody else.’”

Shortly thereafter, Mr. Kean got a call back inviting both men to come on the show.

On the first day the commission met, the Democrats were huddled in one corner and Republicans in the other – like a fourth-grade square dance, says Alvin Felzenberg, a former Kean deputy who became the commission’s spokesperson. There wasn’t a lot of optimism that they would be able to work together effectively.

“The expectations were: Either the commission would deadlock, or it would be so watered down that it wouldn’t be worth very much,” Mr. Felzenberg says.

Notably, the commission hired a nonpartisan staff, selecting staffers for their expertise and reputations as good co-workers rather than for their political ties. They also worked for the commission as a whole, rather than for individuals, to avoid creating partisan fiefdoms.

Mr. Hamilton said he looked for similar qualities in potential commissioners, over whose appointment he had indirect influence. Pragmatism and flexibility were key, as was an understanding of the importance of unanimity.

“I think they also understood the converse of that – if we split all over the place, the recommendations would not have any force,” he says.

An indication of the commission’s cohesiveness came in the second month of hearings, when then-Attorney General John Ashcroft declassified a memo Ms. Gorelick had written while at the Department of Justice and accused her of establishing a policy that restricted intelligence sharing, thus preventing agencies from foreseeing the 9/11 attacks. Ms. Gorelick and her allies, who characterized the memo as simply a clarification of long-standing DOJ policy, saw the attack on her as an attack on the commission as a whole. Senator Gorton, the Republican from Washington state who had sat next to her at that first dinner, was the first to jump to her defense.

“I knew at that point that the commission was one,” says Governor Kean.

Still, there were heated discussions. “You can’t force unanimity,” says Mr. Hamilton. “If it comes at all on controversial topics, it comes after a lot of discussion.”

Chris Kojm, the deputy executive director of the commission, recalls a discussion about a draft chapter involving the bombing of the USS Cole in the fall of 2000. Seventeen sailors had died, and neither the Clinton nor the Bush administrations had responded militarily. The commissioners came to agreement by stripping it down to a bare-bones description of the chronology of events.

“It is noun, verb, description of action. No adjectives, no characterization,” says Professor Kojm, who now teaches U.S. foreign policy and national security at George Washington University’s Elliott School of International Affairs. “That frankly became the editorial tone of the commission report. ... It studiously avoided assigning blame. You’ll never find a sentence that says it was Bush’s fault or Clinton’s fault. There was a very careful dedication to the factual record.”

Despite the careful laying of a bipartisan groundwork and the patience to talk through policy differences, Mr. Hamilton recalls driving home to Northern Virginia on several occasions at 3 or 4 a.m., thinking that they would never reach an agreement. Mr. Kean says it wasn’t until the last week that it became clear they would produce a unanimous report.

A 537-page bestseller

The report came out in July 2004 as the presidential race was heating up. Unlike other reports produced by various Washington commissions over the years, the 537-page tome debuted as the No. 2 book on a paperback bestseller list. People read it on the subway and in airports while waiting for their flights.

Both President George W. Bush and Democratic nominee John Kerry endorsed the report’s findings and recommendations, which included creating a new Department of Homeland Security and a director of national intelligence, to whom all the intelligence agencies would report – a move the agencies resisted.

That reconfiguration would also require a redistribution of oversight among congressional committees, meaning that some members of Congress who had spent 15 or 20 years building seniority would suddenly be stripped of some of their oversight powers.

In the end, nearly all members of Congress supported the commission’s 41 recommendations. A 10-year report card co-chaired by Mr. Kean and Mr. Hamilton identified only three recommendations as unfulfilled, with half a dozen needing improvement.

Families who lost loved ones in the attack were crucial in pressuring both the intelligence agencies and members of Congress to accept the changes, says former Rep. Chris Shays, a Connecticut Republican who had 70 constituents killed in the 9/11 attacks and co-chaired the congressional caucus that pushed for the commission’s establishment and built support for its recommendations. The relatives held vigils, rallies, and press conferences; visited members of Congress; and faxed endless letters to them.

“You had the families say, ‘OK, Congress, you may not want to give up some of your activities and oversight, but we need to make sure there is a Department of Homeland Security,’” says Mr. Shays, who went to many of the funerals, where he repeatedly heard from relatives who wanted to see something positive come out of the attacks. “Without the families, I don’t know if you would have seen the kind of success we saw.”

Indeed, a number of those interviewed say it is unclear whether such pressure could be brought on Congress to investigate the Jan. 6 attack, which has been blamed for the deaths of five people, though the circumstances of some of those deaths remain unclear.

Mary Fetchet, who lost her son Brad in the twin towers and was one of the most prominent relatives advocating for the 9/11 Commission and Congress’s approval and funding of its recommendations, says there should be a similar national demand for accountability in the wake of Jan. 6.

“I think as a country we should be as horrified by the attacks on the Capitol as we were about 9/11,” says Ms. Fetchet, executive director, Voices Center for Resilience (formerly Voices of September 11th). “It’s critical to be just as concerned about domestic terrorism as we are about the attacks on 9/11. ... And so I’m hoping that there is a campaign to really create a 9/11 Commission-like body. But they have to work in a bipartisan manner.”

Patterns

Post-pandemic, will the world think big, or just get by?

With a recovery nearing, our London columnist explores the pandemic’s role as global change agent as businesses and schools reopen, and climate change continues.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

When we are finally free of COVID-19, will we have learned lessons that will make the world a better place?

The economy, education, and the environment will offer litmus tests by which governments will be judged. As they implement recovery plans, will they take the same old pre-pandemic policy approaches they are familiar with? Or will the challenge of rebuilding inspire far greater policy ambition, bolstered by the political will needed to see it through?

Governments are being buffeted by two countervailing forces. On the one hand, people (newly connected worldwide) are aware as they never have been before of just how grave the situation is, and how much action will be needed to remedy it. At the same time, governments are under pressure to address immediate economic needs and simply get their countries up and running again.

One early sign of deeper policy changes, if they are forthcoming, could appear on climate change. If the world could agree on an enforceable path to lower carbon emissions, it would have taken a big step toward “building back better.”

Post-pandemic, will the world think big, or just get by?

Few ideas have become as familiar in the year since the pandemic erupted than this one: that when it’s over, we will all have learned lessons that will serve to build a new and better world.

With governments poised to spend record sums on recovery, we’re about to find out how true that is.

A trio of core issues that might be called the three E’s – economy, education, ecology – offer litmus tests. Will governments resort to the old, familiar, incremental policy toolbox, or will they adopt a wholly different mindset? In other words, will the challenge of rebuilding inspire far greater policy ambition, bolstered by the political will needed to see it through?

It’s still too early to say which way the balance will tilt. Yet it’s already clear decision-makers are being buffeted by two countervailing forces.

One offers good news for those seeking transformational change: the uniquely seismic effect of the pandemic. It's not just the enormous human and economic costs – the greatest peacetime toll since the flu epidemic of a century ago – nor the global reach, but the fact it's been happening in a world interconnected, in real time, as never before.

The result: unprecedentedly wide awareness of the major policy challenges laid bare by the pandemic, and the breadth of policy changes needed to tackle them.

Yet on the other side of the scale is a major practical obstacle: the difficulty of securing concerted international action when the pandemic has reinforced nationalism and protectionism. There are also shorter-term policy impediments, more in keeping with pre-pandemic politics-as-usual. Chief among them is the imperative to address immediate economic needs and simply get countries up and running again.

On each of the three E’s, the pandemic has acted as a combination of unforgiving stress test and high-powered searchlight. It has brought to the fore deeply rooted problems masked, or ignored, as the world rebounded from the financial crisis of a decade ago.

Economically, for instance, the shutdowns of the past year have highlighted how precarious hundreds of millions of jobs are. Informal laborers in the developing world and gig workers in richer countries, especially those from ethnic minorities, have paid the price.

When it comes to the second E – education – the closure of schools and the spread of remote learning have revealed cracks in the system. In poorer countries, the shutdowns have closed off a vital conduit for advancement, especially for girls. The shift to remote classes has disproportionately caused less advantaged pupils to fall behind or drop out altogether. But the disruptions have also forced a rethink of widespread reliance on rote learning and testing.

On the third E – ecology – the pandemic has dramatically raised awareness. It has reminded us of our dependence on the natural world, while dramatic falls in air pollution as a result of the global economic slowdown have brought home the effect of human behavior on nature. All that amid a series of extreme climate events – most recently, the devastating freeze in Texas – that emphasized the effects of climate change.

As governments around the world plan how to respond, business has begun to send powerful post-pandemic signals that it is preparing for major change.

The U.S. automobile giant, General Motors, has announced it will phase out production of gas and diesel vehicles by 2035. In Europe, Volvo and Volkswagen have set even more ambitious timelines.

Even as U.S. President Joe Biden struggles to raise America’s minimum wage to $15 an hour, Costco, the world’s second-largest retail chain, last week said it would pay its employees a minimum of $16. And some schools and educators have responded to pandemic disruptions by advocating major changes to how they teach, prepare, and care for students.

The question remains whether governments will answer with a step-change in their policies. Will they, for example, follow the advice of many education specialists and rethink schooling and apprenticeship programs to equip young people with the skills required for 21st -century high-tech jobs?

Two major recovery plans – in the U.S. and Britain – have made headlines in recent days. They are both geared largely to ensuring short-term support for pandemic-affected workers and businesses.

Yet one early sign of whether there will be deeper policy changes could come on climate change.

President Biden has pledged a national infrastructure upgrade emphasizing green energy projects. The 27-nation European Union and Britain have also put green initiatives at the heart of their recovery programs.

But if Western nations clean up their economies simply by outsourcing carbon-intensive jobs to countries like China, that does not do the planet any good.

The solution, or so Britain hopes as it prepares to chair a major climate summit later this year to strengthen the Paris climate agreement, would be to secure international agreement on an enforceable path to lower emissions worldwide.

In today’s geopolitical environment, that could prove a tall order.

Yet if it could be achieved, it would pass the test set by another familiar refrain from this pandemic year, “Building Back Better.”

The Explainer

Syria, after 10 years of conflict: No war and no peace

The war may be over, but Syria remains a nation riven by a variety of occupying forces locked in an uneasy stalemate. What’s the path forward?

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

Viewed from afar, the Syrian conflict marking its 10th anniversary March 11 has ground to a stalemate. President Bashar al-Assad has neither completely won, nor lost. Despite Russian and Iranian backing, sizable parts of his country remain beyond his reach.

But the situation on the ground is not static. Everywhere the humanitarian toll mounts. After 400,000 dead, the Syrian people are confronting the tabulation of war crimes that include more than 300 documented uses of chemical weapons, torture, and indiscriminate attacks on cities and hospitals.

Syria’s battlefields are largely quiet, but years of United Nations peace efforts have made no headway. The United States told the Security Council in December that Damascus was preparing “to carry out a sham presidential election in 2021 and wash its hands of the U.N.-facilitated political process.”

The human cost is almost immeasurable. Nearly 60% of Syrians are “food insecure,” the World Food Program reported last month. And the reckoning is far from over. In a bid to hold Mr. Assad and his inner circle accountable, a complaint was filed in France with a special war crimes unit this week focusing on the August 2013 chemical weapons attacks in eastern Ghouta that left 1,400 dead.

Syria, after 10 years of conflict: No war and no peace

Viewed from afar, the Syrian conflict marking its 10-year milestone March 11 has ground to a stalemate. President Bashar al-Assad has neither completely won, nor lost. He is in charge, with Russian and Iranian backing, though sizable parts of his country remain out of the reach of his exhausted forces and allies.

But on the ground, the situation overall is not static. In the east, Islamic State remnants are waging a lethal guerrilla campaign, and everywhere the humanitarian costs continue to mount. After 400,000 dead, the Syrian people are confronting a collapsed economy, deepening food insecurity, and the tabulation of war crimes that include more than 300 documented uses of chemical weapons, torture, and indiscriminate attacks on cities and hospitals.

Is there still a war?

The battlefield itself has been largely quiet for a year. A Russian-Turkish cease-fire has mostly held since Turkish military intervention prevented Syrian troops – supported by Russian air power – from recapturing rebel-held Idlib province in northwestern Syria. The enclave is home to 3 million civilians and a host of jihadi actors that include 10,000 armed militants – most of whom washed up in Idlib as part of previous surrender agreements elsewhere in the country.

Years of United Nations peace efforts have made no headway, including Security Council Resolution 2254, which in December 2015 laid out a political road map meant to establish “credible, inclusive and non-sectarian governance” within six months, and a new constitution.

If anything, those aspirations have been marked only by their breach. Damascus, for example, reluctantly sent a delegation to Geneva to take part in nonbinding, U.N.-facilitated efforts to write an inclusive constitution that finally began in October 2019.

But by late January this year, after the fifth session in 16 months, delegates had failed to even start composing a draft. When the government side rejected the latest proposals, U.N. Special Envoy Geir Pedersen expressed his frustration, saying, “We can’t continue like this.”

Chances are slim Mr. Assad will accept negotiating away his grip on power to opponents he deems “terrorists.” He has not recaptured “every inch” of Syria, as he once vowed, but nevertheless is preparing for elections this spring.

The United States told the Security Council in December it was “increasingly apparent” that Damascus “is delaying the [constitution] Committee’s work to buy time as it prepares to carry out a sham presidential election in 2021 and wash its hands of the U.N.-facilitated political process.”

Who is in Syria?

The short answer: Nearly everyone who has battled in this proxy war is still on the ground, ensuring that Syria remains physically split into different areas of control.

Iran, which was among the first to come to Mr. Assad’s side, enlisted the powerful fighting capabilities of Lebanon’s Hezbollah, and later marshaled Shiite militias from Iraq and Afghanistan. The U.S., Turkey, and their Persian Gulf allies made halfhearted efforts to support anti-government rebels, but the regime in Damascus was kept on life support by Iran until Russia intervened with air power in September 2015. Moscow irreversibly turned the tide of the war in Mr. Assad’s favor.

Yet today, Turkey has roughly 12,000 troops in northwest Syria, ostensibly to create a “safe zone” for refugees and to defend Idlib. The Turks also aim to prevent an exodus of more Syrians (and jihadi militants) across the border into Turkey, where some 3.6 million registered refugees already reside, as well as to check Kurdish forces it deems a security threat.

And in the oil-rich northeast, several hundred U.S. troops – left over from the yearslong fight against Islamic State in Syria and Iraq – support a Syrian Kurdish paramilitary force of more than 100,000 fighters that deprives Damascus of one-quarter of its territory and 80% of its resources.

What is the human cost?

In terms of the damaged social fabric and wrecked economy, almost immeasurable. Syria’s currency has collapsed and inflation is skyrocketing, with the price of cooking oil alone quintupling in the past year.

Some 12.6 million Syrians have been displaced from their homes – many forced to move multiple times – and 6.6 million of those have fled the country. Physicians for Human Rights has documented nearly 600 regime attacks on medical facilities since 2011, 90% of them by regime forces.

And the International Rescue Committee, in a survey of several hundred Syrians and 74 health workers released March 3, deplored how the regime “war strategy has turned hospitals from safe havens into no-go zones where Syrian civilians now fear for their lives.”

Indeed, Mr. Assad now presides over a wasteland in which a record 12.4 million people – nearly 60% of Syria’s population – are “food insecure,” according to a report by the U.N.’s World Food Program last month. In the past year alone, the number of Syrians the U.N. deems “severely food insecure,” such that they can’t survive without assistance, has doubled to 1.8 million.

“The situation has never been worse,” said WFP’s Syria Director Sean O’Brien.

And the reckoning is far from over. In a bid to hold Mr. Assad and his inner circle accountable, a complaint was filed in France with a special war crimes unit this week, focusing on the August 2013 chemical weapons attacks in eastern Ghouta that left 1,400 dead. A similar complaint was filed in Germany in October.

Book review

‘Klara and the Sun’: Do androids dream of human emotions?

In this novel, told from the perspective of a robot companion to a teenage girl, we learn what artificial intelligence can teach us about love, hope, inequality, and loneliness.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

-

By Heller McAlpin Correspondent

“Klara and the Sun” touches on a number of weighty issues, including the insidious encroachments of AI technology, the repercussions of rampant inequality, the degradation of the environment, and the prevalence of loneliness. In her dogged attempts to understand humans, Klara tries to untangle what makes them act the way they do; is it something to do with what Josie’s father calls “the human heart … in the poetic sense”?

‘Klara and the Sun’: Do androids dream of human emotions?

What makes a person “special and individual” and therefore irreplaceable? Is there something unreachable and nontransferable deep inside each of us, something uniquely human that even advanced science and artificial intelligence can’t fathom or duplicate? These are questions that Kazuo Ishiguro probes in “Klara and the Sun,” his first new novel since winning the Nobel Prize in 2017.

Like “Never Let Me Go,” Ishiguro’s discomfiting 2005 dystopian novel about clones raised to be organ donors, his latest involves science taken to sinister, ethically questionable levels. But it is also a surprisingly warm morality tale about love, heart, hope, empathy, and the idea that “there are all kinds of ways to lead a successful life.”

The book is narrated by Klara, an uncommonly observant and sympathetic solar-powered AF (artificial friend) whose mandate is to closely study her teenage charge, a girl named Josie, to better fulfill her role as Josie’s caring companion.

Like the butler in Ishiguro’s Booker Prize-winning “The Remains of the Day,” Klara has a limited purview – partly because of her subservient, low social standing in Josie’s household, but also because she isn’t human. Her manner is simple, her speech direct, and her personality is without wiles, but she’s no dummy.

Klara worships the sun, which fuels her, and she is convinced that harnessing his power (she views the sun as masculine) will make Josie, who is in poor health, well again. This idea is taken to sometimes cloying extremes, but while Klara is by design intensely focused on her charge’s well-being, this is not another Ishiguro novel whose characters are so wrapped up in the minutiae of their daily lives that they ignore the big, darker picture.

In fact, Ishiguro upends our expectations: Klara, although a technological breakthrough, is – unlike the artificial human in Ian McEwan’s 2019 novel, “Machines Like Me” – not creepy. Without giving away too much, I can say that the novel’s principal – and far creepier – ethical issue involves genetic manipulations that confer special social and educational advantages, which leads to an unfair, stratified society. These “edits” can also carry grave health risks.

Klara’s perspective – her literal point of view – is key to the novel, which opens in the city shop where she awaits purchase, along with more sophisticated, newer model AFs. When she is moved from mid-store to the front window, she revels in the extra exposure to sunlight and the expanded view: “I’d always longed to see more of the outside – and to see it in all its detail,” she says.

Ishiguro carefully limits our perspective to what Klara takes in, which means physical details in particular are often scant: Josie is thin, with an “uncertain stride”; her mother is tense and wears “high-rank office clothes.” We never learn exactly what the mother does when she drives off to work every day (lawyer, perhaps), and why she wasn’t “substituted” by AI like Josie’s absent father, a brilliant engineer, who now lives in a rough community of outliers.

Also, unlike McEwan’s fully functioning artificial man, we never learn much about Klara’s physical being. Does she have skin? How human does she look? Josie’s description of her, later quoted by Klara, is likewise limited – to a teenager’s perspective: “really cute, and really smart. Looked almost French? Short hair, quite dark, and all her clothes were like dark too and she had the kindest eyes and she was so smart.”

We do learn, however, that Klara can’t smell, which she tells Josie’s boyfriend, Rick, when he apologizes for the odor of the ramshackle house in which he lives with his disheveled mother. This household provides a troubling window into the limited prospects for the “unlifted” in this brave new world. For one thing, they do not have expensive androids, and Rick’s mother, on meeting Klara, wonders whether she’s supposed to treat her like a guest, or “like a vacuum cleaner.” Klara does not take offense, but readers feel the question’s sting.

“Klara and the Sun” touches on a number of weighty issues, including the insidious encroachments of AI technology; the repercussions of rampant inequality; the degradation of the environment (with smog that, to Klara’s dismay, blocks the sun’s benefits); and the prevalence of loneliness. In her dogged attempts to understand humans, Klara tries to untangle what makes them act the way they do; is it something to do with what Josie’s father calls “the human heart ... in the poetic sense”?

Ishiguro’s intrinsically honest narrator is limited, but she has depth. This is a character whose vision goes wonky and fractures into tiny boxes when she is overwhelmed by what she sees, yet who never stops trying to synthesize the pieces.

The book’s cinematic final scene, which underscores Ishiguro’s theme of obsolescence in the face of rapidly advancing technology, may strike readers as desolate. But Ishiguro chooses to play up its more hopeful aspects by having ever-sunny Klara use this time as an opportunity to process all she’s experienced. And his unusually likable android comes to a radiant epiphany about Josie – and by extension, other humans: “There was something very special, but it wasn’t inside Josie. It was inside those who loved her.” Corny? Well, yes. But also wise and sweet – and a pleasant subversion of what we expect from a dystopian story about the dangers of technology taken too far.

In addition to the Monitor, Heller McAlpin reviews books regularly for NPR and The Wall Street Journal, among other publications.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Alternatives to a boycott of Beijing Olympics

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

China has jailed nearly every major voice in Hong Kong opposing its efforts to crush local democratic rule in the territory. It has stepped up its harsh treatment of the Uyghur minority in Xinjiang province, leading to claims of genocide. And yet China is scheduled to host the 2022 Winter Olympics early next year. Around the world, many countries are debating whether to send a signal about these official abuses by not sending their athletes to Beijing.

For more than a century the modern games have served as an opportunity for peaceful contact and greater understanding among nations. Those who would suffer most directly from a boycott are the athletes, who often train for years for their moment in a premier competition. To them, the innate nationalism in the games should not get in the way of the sport itself.

Given a boycott’s possible damage to Olympic athletes and to the purposes of the event, could something short of a full boycott achieve the same purpose of expressing disapproval of China’s abysmal abuse of its citizens? The dazzling spotlight on the games can also shine into China’s dark corners.

Alternatives to a boycott of Beijing Olympics

China has jailed nearly every major voice in Hong Kong opposing its efforts to crush local democratic rule in the territory. It has stepped up its harsh treatment of the Uyghur minority in Xinjiang province, leading to claims of genocide. And yet China is scheduled to host the 2022 Winter Olympics early next year. Around the world, many countries are debating whether to send a signal about these official abuses by not sending their athletes to Beijing. A group of more than 180 activist groups is calling for some kind of boycott.

Some cite the decision in 1936 by Western democracies not to boycott the Summer Olympics held in Berlin that year. Instead of acting as a moderating influence on then-Nazi Germany, those games served as a propaganda triumph for Adolf Hitler’s regime.

An Olympics boycott is not new. In 1976 a number of African countries boycotted the games, protesting the inclusion of then-apartheid South Africa. In 1980 the United States, Canada, Japan, and West Germany boycotted the Moscow Summer Olympics to protest the then-Soviet Union’s invasion of Afghanistan. In retaliation the Soviets boycotted the 1984 Summer Olympics in Los Angeles.

For more than a century the modern games have served as an opportunity for peaceful contact and greater understanding among nations. Those who would suffer most directly from a boycott are the athletes, who often train for years for their moment in a premier competition. To them, the innate nationalism in the games should not get in the way of the sport itself.

The 2008 Summer Olympics, the first games held in Beijing, were seen by the West as an opportunity to moderate the behavior of China’s ruling Communist Party. Since 2012, however, party leader Xi Jinping has reversed the few political freedoms enjoyed by the Chinese.

Fearing a boycott for next year’s games, China has made it clear it will retaliate against any country that takes such action. As the world’s No. 2 economic power, it has already shown it will punish countries that challenge its policies. China has reduced exports from Australia after that country called for an international investigation into the origins of COVID-19.

Given a boycott’s possible damage to Olympic athletes and to the peaceful purposes of the event, could something short of a full boycott achieve the same purpose of expressing disapproval of China’s abysmal abuse of millions of its citizens?

Could, for example, athletes participate while delegations of government officials and sponsors stay away? Might athletes find ways during the games to distance themselves from China’s propaganda or point out the benefits of a free society? They could, for example, boycott the opening ceremonies or use press conferences and social media to speak up. Their integrity as successful athletes gives them far more credibility than a regime that punishes people for their views, religion, or ethnicity. Clever protest actions at the games would be reported in most countries and possibly slip past government censors inside China.

With the world’s best athletes in Beijing next year, the dazzling spotlight on the games can also shine into China’s dark corners, perhaps helping to achieve the noble aims of the Olympics of building a peaceful world and creating respect for universal ethical principles.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

From hope to freedom – the ongoing influence of a woman’s discovery

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 4 Min. )

-

By Dilshad Khambatta Eames

It’s Women’s History Month, and here’s an article exploring the enduring value and relevance of one woman’s contribution to the world: Mary Baker Eddy’s discovery of Christian Science, which empowers, helps, and heals.

From hope to freedom – the ongoing influence of a woman’s discovery

A few years ago, I visited First African Baptist Church in Savannah, Georgia. I was so moved by some designs engraved on the original pews, said to be messages of hope written by enslaved Black people who had taken refuge in that church in the 19th century.

Most of us have never been in the unthinkable situation those individuals were. But don’t we all hope for freedom of some kind – whether from an illness or injury, fear, anxiety, or something else? We may relate to these words in a psalm: “Why am I discouraged? Why is my heart so sad?” The verse concludes, “I will put my hope in God! I will praise him again – my Savior and my God!” (Psalms 43:5, New Living Translation).

I have found great hope, encouragement, and healing from the life and writings of the remarkable 19th- and 20th-century woman Mary Baker Eddy, who is the founder of this newspaper. She suffered from ill health and poverty in her earlier years and lived at a time when women had little voice. But she repeatedly turned to God’s love, where she found refuge, comfort, and healing.

In 1866, Mrs. Eddy fell on ice and wasn’t expected to live. She asked for her Bible to find comfort and read a Gospel account of one of Jesus’ healings. Her deep inner trust in a powerful, loving God took on a new dimension. She glimpsed that divine Spirit, God, is our only real existence, and was healed.

Mrs. Eddy had long devoted herself to searching the Scriptures for answers, particularly Jesus’ teachings and healing works, and through this healing she discovered the allness of God, infinite good, and the consequent impotence of evil. She named her discovery Christian Science, reflecting its basis in the provable divine law of God’s healing goodness, always in operation – which was the basis for Jesus’ healings.

Her book “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures” is the textbook of Christian Science, and it refers to a “universal freedom, asking a fuller acknowledgment of the rights of man as a Son of God, demanding that the fetters of sin, sickness, and death be stricken from the human mind and that its freedom be won, not through human warfare, not with bayonet and blood, but through Christ’s divine Science” (p. 226).

Decades ago, when I first learned of Christian Science, I glimpsed the healing and freeing truth of this divine revelation. I recall what it felt like to consider that we are more than mortals, we are perfect spiritual reflections of God’s nature. Science and Health weaves through its pages Bible-based synonyms for God that bring out the vastness, or, “allness” of Deity. They are Mind, Life, Truth, Love, Principle, Spirit, and Soul. Understanding God in this way, we begin to feel God’s ever-present reality and majesty, and this is a true and living communion, or prayer.

Studying this Science discovered by Mrs. Eddy has had a transformative effect on my outlook, confidence, and happiness. I’ve seen changes in every aspect of my life – home, career, health, etc. – as step by step I’ve found trust and freedom in God’s continuous, unfolding goodness, especially during hard times.

This freedom and joy didn’t come from changed human circumstances, but rather from the deep satisfaction and peace gained from a clearer understanding of God’s impartial goodness and abundant mercy – which then changed my life in tangible ways. It felt like a spiritual baptism, a submergence in the Spirit and substance of divine Love. As Mrs. Eddy writes, “Love is the liberator” (Science and Health, p. 225).

Individually and collectively, we can affirm and trust that prayer rooted in divine Love’s omnipresence is a powerful influence that lifts us to understandingly trust in God’s justice, mercy, and freedom for all. The Christ that Jesus expressed uncovered and rebuked everything unlike God, good. Thus Jesus brought to light the truth that Love is the only legitimate presence and power. It was the same Christ, divine Truth, that enabled Mrs. Eddy to overcome illness, injury, and injustices of her day, and to heal as Jesus taught.

In her sermon “The People’s Idea Of God – Its Effect on Health and Christianity,” Mrs. Eddy describes “a higher and holier love for God and man” and urges us to “behold once again the power of divine Life and Love to heal and reinstate man in God’s own image and likeness...” (p. 14). For all kinds of problems that seem to hold us captive, the teachings of Christian Science show us that Christ is still with us now, uplifting hope to a deep and liberating conviction that healing is possible.

Some more great ideas! To read or listen to an article in the weekly Christian Science Sentinel on how God heals us titled “Christian Science isn’t ‘mind over matter,’” please click through to www.JSH-Online.com. There is no paywall for this content.

A message of love

Safe at home

A look ahead

Thanks for joining us. Come back tomorrow: We’re working on a film review of a delightful documentary about the men and their dogs unearthing truffles in the forests of Italy.