- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- Myanmar protesters bridge religious divides to counter military rule

- How Colorado residents grapple with legacy of mass shootings

- Delays at Census spell trouble for redistricting – and the 2022 election

- First step: Threaten to ban Twitter. Next: A separate Russian internet?

- Cacao without deforestation? Land reform in Brazil bears fruit.

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

How a Dvořák symphony set back Black American classical composers

April Austin

April Austin

The classical music world is wrestling with how to build awareness of Black American contributions and foster greater diversity. For one scholar, that involves deeply exploring the legacy of a composer who was not even American.

Douglas Shadle of Vanderbilt University has written the book “Antonín Dvořák’s ‘New World’ Symphony,” which looks at a staple of the orchestral repertoire. Dvořák, a European composer, arrived in the United States from Prague in 1892 to teach. When he heard African American work songs and spirituals such as “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot,” he worked melodic ideas from them into his 1893 “New World” Symphony.

Critics praised the symphony, but they ignored the composer’s own statements about gaining inspiration from Black musical sources. Some Black musicians applauded Dvořák, but others saw his attempts as “a flattening out of the African American experience,” as Professor Shadle describes it in an interview. Dvořák had captured the sounds, but not the spirit, of the music.

The composer also perpetuated the stereotyping of Black American classical music – that it could only include spirituals and traditional songs. This erased the history of 18th- and 19th-century Black composers who had trained in the European style. It also negated orchestras that were formed by Black musicians before the Civil War in cities like New Orleans.

Today, many audiences expect music by Black American composers to sound like spirituals and gospel tunes, or ragtime and jazz. And, of course, there are fine composers working in those genres. But to change limited expectations will take commitment on the part of orchestras. “Diversity is not just checking off a box,” says Professor Shadle, “but thinking about it within and across [the categories of Black music] to round out the picture.”

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Myanmar protesters bridge religious divides to counter military rule

Religion has long been a divider in Myanmar – most tragically, in the persecution of the Rohingya. But the urgency of opposing a military coup has brought activists from different faiths together, protesters say.

Since the Feb. 1 military coup in Myanmar, thousands of protesters have taken to the streets to oppose the junta, often risking their lives.

Among them are many Buddhist monks – but also Christians and Muslims, banding together in a country where religion has long been a divider. Majority-Buddhist Myanmar has a history of discrimination and violence against Muslims, particularly the Rohingya. But today in the streets, people are showing a powerful solidarity, activists say.

New networks pooling resources “have the confidence to say democracy is for all of us,” says Aye, a Christian activist in Yangon.

Religious unity is particularly threatening to the generals who led the coup because of the close relationship between Buddhism and the state. But the coup has undermined the military’s efforts to cast itself as the guardian of the nation and Buddhism.

Mandalar, a Buddhist monk, exemplifies the younger generation of monks who are wholeheartedly backing the protesters against the coup.

“When the people are suffering, how could we live in a peaceful way?” he asks, his voice rising with emotion. “No one should live under threat, in danger, in fear – not now and not in the future!”

Myanmar protesters bridge religious divides to counter military rule

Peter, a young father, looked out at the sea of tens of thousands of peaceful protesters surrounding him in a sit-in at a market in his hometown of Mandalay, their bright red and yellow posters condemning the Feb. 1 military coup in Myanmar.

Moments later, security forces assaulted the crowd, firing tear gas and live rounds. “They arrived as early as possible and start brutally cracking down, shooting, beating, even firing on the street,” says Peter, using a pseudonym for his protection. “A few of our friends died, and a lot were arrested.”

EDITOR'S NOTE: This story has been updated with the toll from violence on Saturday.

Peter is Muslim. The friends he lost in the protest earlier this month were Buddhist. Despite Myanmar’s long history of discrimination and violence against Muslims by the Buddhist majority – tensions and fears the military junta seeks to exploit – today on Myanmar’s streets people are showing a powerful solidarity, activists say.

After the coup, different religious groups “are more unified than ever,” Peter says, speaking by phone from Mandalay.

In diverse and deeply pious Myanmar, protests by religious groups have deep resonance in challenging the legitimacy of those who hold power. Today’s cooperation among different faiths in backing a broader, youth-led protest movement against the junta reflects a decade of efforts at interfaith peace building since the country’s opening to semi-democratic, civilian rule, experts say.

It has been challenging work in a country suffering devastating interreligious conflict, including a military campaign of killing, arson, and rape against Myanmar’s Muslim Rohingya ethnic minority that since 2017 has forced more than 730,000 Rohingya to flee into Bangladesh.

That crisis was fueled, in part, by Buddhist nationalists. Now, activists worry that the military will try to provoke further religious conflict to win support from the majority Bamar ethnic people, who practice Buddhism.

“Myanmar is a country with so many complexities and so much history of identity politics,” says Aye, a Christian activist in Yangon, who for protection asked to use a pseudonym and the gender-neutral pronoun “they.” “It’s so easy to say this Muslim person has raped this Buddhist woman or something that triggers mob violence. [The military has] done that really, really well over the years,” they add.

But today, “there is a much more open conversation on what it actually means to be Muslim, what it actually means to be Christian, what it actually means to be Hindu and Buddhist and Sikh,” Aye says.

Coming together

New networks involving Buddhists, Muslims, Christians, and other faithful are pooling resources and coordinating support for the protests in different parts of the country, Aye says. “They have the confidence to say democracy is for all of us.”

“The military miscalculated the strength and the groundwork that had already been laid, and didn’t think the people would be confident enough to come out against them so strongly,” Aye says by phone from Yangon, where they are active in protests.

Myanmar’s strong culture of giving – it is the second-most charitable country in the world after the United States – has seen an outpouring of donations to support informal health clinics and local markets, as the civil disobedience movement halts public services and businesses.

Christians are playing a bigger role than in past protests, says David Moe, a Ph.D. candidate at Asbury Theological Seminary, who grew up in Myanmar’s majority-Christian Chin state. “The coup is clearly unjust for the majority of Christian groups, even though in the beginning of the movement some people were hesitant,” he says. The Burmese Christian refugee community in the United States is actively raising funds to help support striking government employees, he says.

For its part, the military junta is working to sow divisions within the protest movement, Peter says, such as by claiming the National League for Democracy, the political party of civilian leader Aung San Suu Kyi that won a landslide election victory in November, was funded by overseas Muslim groups to promote Islam in Myanmar. Soon after the coup, the military raided the Muslim quarter of Mandalay, claiming to be hunting terrorists, he adds.

But such timeworn scapegoating tactics are proving ineffective, Peter believes. “People are more united, and they see the coup as the main problem,” he says.

Religion and state

Religious unity is particularly threatening to the generals who led the coup, because of the historically symbiotic relationship in Myanmar between Buddhism and the state.

“The health of each is thought to be dependent on the other,” says Susan Hayward, an expert in peace building and Myanmar at Harvard Divinity School. “So the state provides for the monastic community’s health and well-being, provides economic resources, helps to … oversee conflicts within the sangha [community of monks], and in return, the sangha provides forms of moral legitimacy, spiritual power, and religious legitimacy to the state.”

Some monks, especially in the older generation, side with the military. “They really believe they are the protectors of the country,” says Somboon Chungprampree, a Thai social activist and executive secretary of the International Network of Engaged Buddhists in Bangkok.

But the coup has undermined the military’s effort to cast itself as the guardian of the nation and Buddhism, especially as the public grows weary of strident nationalism and religious discrimination and identity politics.

“Today when we say … this person is a nationalist, it’s much more negative than positive,” says Aye.

In a potentially ominous development for the military, Myanmar’s influential, state-appointed Buddhist monks’ association, the State Sangha Maha Nayaka Committee, last week called on the military to halt its violence against the protesters, foreshadowing a possible break with the regime, according to a leaked document reported by the online news outlet Myanmar Now.

“That’s huge actually, because the Maha Nayaka … has tended historically to be very conservative and not issue statements or take actions that are oppositional to the state,” says Ms. Hayward. For example, it did not support the 2007 Saffron Revolution led by Buddhist monks.

If this powerful Buddhist association “is considering participating in the civil disobedience movement and breaks with the state military, that would be a historical anomaly,” she says. “It would send a very strong moral message to the military that has tried very hard to present itself as having Buddhist legitimacy.”

Protesting monks have drawn on religious symbolism to spiritually exile the military, turning over their alms bowls to signal they cannot accrue good karma by making donations, and that the monks will no longer perform Buddhist rites for them.

Taking risks

Mandalar, a Buddhist monk in Mandalay, exemplifies the younger generation of monks who are wholeheartedly backing the protesters against the coup.

Depending on the day, Mandalar may be helping to carry injured protesters to makeshift hospitals in monasteries, or seeking donations to pay for medicine, food, and water.

“Even last night, they were shooting machine guns and killed and injured many people,” he says on a call from Mandalay. “We have martial law. If you go outside, they will shoot. It’s a bad situation.”

Activists in Myanmar reported that as of Friday more than 300 people had been killed by the government since the Feb. 1 coup and nearly 3,000 had been arrested. In widespread clashes Saturday, Myanmar's Armed Forces Day, the Associated Press reported that dozens more had been killed in what appears to have been the deadliest day since the coup. It cited an independent researcher in Yangon and Myanmar Now as saying the toll in more than two dozen cities and towns exceeded 100 dead by nightfall.

For Mandalar, his Buddhist faith and his activism complement each other – reflecting the strong connection in Myanmar between religion and community.

“When the people are suffering, how could we live in a peaceful way?” he asks, his voice rising with emotion. “We have to help the people get their rights and freedom. We don’t want to live in fear and danger. We are also part of the country and the family. If we deny the situation and don’t [get] involved, it’s a shame.

“No one should live under threat, in danger, in fear,” he says. “Not now, and not in the future!”

How Colorado residents grapple with legacy of mass shootings

For Colorado survivors of mass shootings, Monday’s attack – and the immediate choosing of sides in the gun control debate – were sadly familiar. Healing is an individual journey, they say. For some, activism helps. For others, it adds trauma.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

-

By Grant Stringer Correspondent

Colorado is best known as an outdoor enthusiast’s paradise of grandiose mountain peaks, rich in Western history. But over the past two decades it also has become synonymous with that particularly American tragedy: the mass shooting. It’s not that Colorado is home to the most shootings – it ranks eighth – but that it has endured so many high-profile ones. And that legacy is something that more Coloradans, particularly survivors, are wrestling with.

Columbine High survivor Evan Todd is watching the renewed tension from his home in suburban Denver. He’s an outspoken proponent of guns as a deterrent to mass shootings. But he is concerned that survivors of Monday’s King Soopers massacre will suddenly find themselves thrust into the fierce debate about gun control.

They’ll quickly be asked to pick sides, he says, in a way that can be detrimental to their own healing journey. He remembers having microphones and cameras thrust in his face as a teenage survivor.

“Be careful taking time and taking care of yourself,” he says. “You’re not alone. There’s people out there, whether it’s in schools, families, churches, police officers – there’s always someone you can turn to when you’re going through difficult times, whatever it is.”

How Colorado residents grapple with legacy of mass shootings

Sammie Lawrence IV was hungry on Monday before his shift as a marijuana trimmer in Boulder. Around 2:30 p.m., he was perusing the deli section of a local King Soopers grocery store when he heard several pops.

“Then I saw people running,” he says.

Mr. Lawrence realized what was happening: A shooter had entered the store to kill employees and grocery shoppers in what would become the country’s deadliest mass shooting of the year to date. Police now suspect Ahmad Al Aliwi Alissa of killing 10 people, including police officer Eric Talley, before he surrendered almost an hour later. A motive isn’t clear.

Mr. Lawrence says he joined others running to the back of the store, away from the shots. He helped escort an older man in a walker and others down a loading dock and to safety. Mr. Lawrence says he then roamed the strip mall around the grocery store, and when the shooting ended, he began to comfort traumatized survivors who, unlike him, had witnessed deaths.

Mr. Lawrence now has another struggle: grappling with his firsthand experience of surviving a mass shooting in his own community.

“I’m getting better one day at a time,” Mr. Lawrence says two days after the shooting. “I know I’m forever changed by this incident. I know I am.”

He joins the ranks of many Coloradans who have a personal link to a mass shooting, beginning with the Columbine High School massacre in 1999, who are forever changed, too.

Colorado is best known as an outdoor enthusiast’s paradise of grandiose mountain peaks, rich in Western history. But over the past two decades it also has become synonymous with that particularly American tragedy: the mass shooting. It’s not that Colorado is home to the most shootings – it ranks eighth among U.S. states, according to criminologist Jillian Peterson – but that it has endured so many high-profile ones. And that legacy is something that more Coloradans, particularly survivors, are wrestling with.

Recent elections have also solidified its transition from a purple state to a Democratic stronghold. That evolution has fueled political polarization that makes tackling societal problems like mass shootings even more divisive.

Thirteen victims died at Columbine in 1999 in a tragedy that brought school shootings to the national consciousness. Coloradans again watched the news horrified in 2012, when 12 victims died and 70 more were injured in the Aurora movie theater shooting. Both massacres rocked the country. Since Columbine, the state has had to grapple with a series of additional shootings, including at the New Life Church and a Planned Parenthood in Colorado Springs, at a Thornton Walmart in 2017, and the death of student Kendrick Castillo in a 2019 school shooting in another Denver suburb.

Now Boulder joins the infamous list.

But the tragedy Monday also tore open political animosities between mass shooting survivors. Some told the Monitor they’re gearing up for renewed political battles to prevent the next tragedy, while others see history repeating itself in blame games and calls for gun control.

Denver resident Sara Grossman says she was already reeling when she heard about Boulder’s mass shooting. A gunman had killed eight people in Atlanta just days before.

Mass shootings renew personal grief for Ms. Grossman. Five years ago, she lost a close friend in the Pulse nightclub massacre in Orlando, Florida. She says she used to frequent that club before she moved to Colorado.

“I had no idea why, but the first couple of times I tried to go grocery shopping after I returned from [my friend’s] funeral in Orlando, I had such anxiety about going into large, enclosed spaces,” Ms. Grossman says. “It’s even harder when the thing that you’re actually anxious about comes through.”

From tragedy to activism

Jane Dougherty still remembers picking up her children from another school near Columbine High School on the day of the massacre, more than 20 years ago. Unfortunately, she would only become more tied to mass shootings as time wore on. She says she was raised in Aurora, a community turned on its head after the 2012 theater shooting. Later that year, Ms. Dougherty’s sister Mary Sherlach was killed in Connecticut’s Sandy Hook shooting.

“It’s surrounding me,” Ms. Dougherty says of gun violence.

She says she understands why Coloradans feel emotionally weary after so many tragedies.

Today, Ms. Dougherty is an activist with Everytown for Gun Safety, a group that has identified gun control as the avenue to limit gun violence. She channeled her grief after the death of her sister into determination, lobbying to push through historic gun control efforts in Colorado’s state legislature.

That included 2013 laws establishing universal background checks for residents buying firearms and limiting magazine capacities. They’re still on the books.

In the wake of the fierce political debate that year, voters removed two Democratic state senators from office in a recall election spearheaded by gun rights activists – an indication that Coloradans remained divided about mass shootings and gun controls.

But unlike those in Congress, Democrats in the state General Assembly continued to see more success enacting gun control legislation.

They passed a so-called red flag law in 2019 that allows authorities to seize firearms from people deemed dangerous to themselves or others. State Rep. Tom Sullivan, whose son Alex died in the Aurora theater shooting, sponsored the bill.

Capitalizing on a tragedy?

Gun rights activists framed the shooting Monday as the nail in the coffin for Colorado’s gun controls. And the longtime arguments about the nature of mass shootings have flared up again.

Several activists quickly noted this week that the red flag law didn’t stop Mr. Alissa from legally buying an assault weapon six days before the Boulder shooting, according to the Associated Press, despite his reported history of violence and instability. Neither did the mandated background check or other rules. Gun control activists, meanwhile, point out that a judge blocked Boulder’s 2018 ban on the sale of assault-style weapons and large-capacity magazines just this month.

Taylor Rhodes, executive director of Rocky Mountain Gun Owners, says liberal activists have once again moved to capitalize on a tragedy and strip gun rights from legal gun owners.

“The corpses were not even cold before they started calling for gun control,” he says.

For her part, Ms. Dougherty isn’t deterred. She says her resolve to pass new gun control laws is only strengthened.

“You can either crawl back into your hole, or you get back up and keep working,” she says.

Top state Democrats may introduce an assault-style weapons ban during the ongoing legislative session, according to media reports. Currently, they have enough votes to pass laws without the assent of Republicans, who have generally opposed gun controls.

“You’re not alone”

Columbine survivor Evan Todd is watching the renewed tension from his home in suburban Denver. He’s an outspoken proponent of guns as a deterrent to mass shootings, and he’s generally opposed to politicians revoking gun rights.

But he is concerned that survivors of the King Soopers massacre will suddenly find themselves thrust into the fierce debate about gun control.

They’ll quickly be asked to pick sides, he says, in a way that can be detrimental to their own healing journey. He remembers having microphones and cameras thrust in his face as a teenage survivor of a nightmarish mass shooting.

“Be careful taking time and taking care of yourself,” he says, as if speaking directly to survivors. “You’re not alone. There’s people out there, whether it’s in schools, families, churches, police officers – there’s always someone you can turn to when you’re going through difficult times, whatever it is.”

Ms. Grossman says political advocacy became a core part of her own healing process after losing her dear friend five years ago. But she cautions that the healing process can be “completely different” for individuals. “People deal with their own grief and their own anguish in totally different ways,” she says.

In Boulder, Mr. Lawrence becomes emotional when recalling his experiences inside the King Soopers Monday.

His immediate plans are to get himself into therapy. His mother flew out from Ohio to surprise him and help support him as he starts to heal. He’s beginning to cope with it all.

“I now understand what it was like for the kids in Aurora and Columbine,” Mr. Lawrence says. “I get it. And I wish I didn’t.”

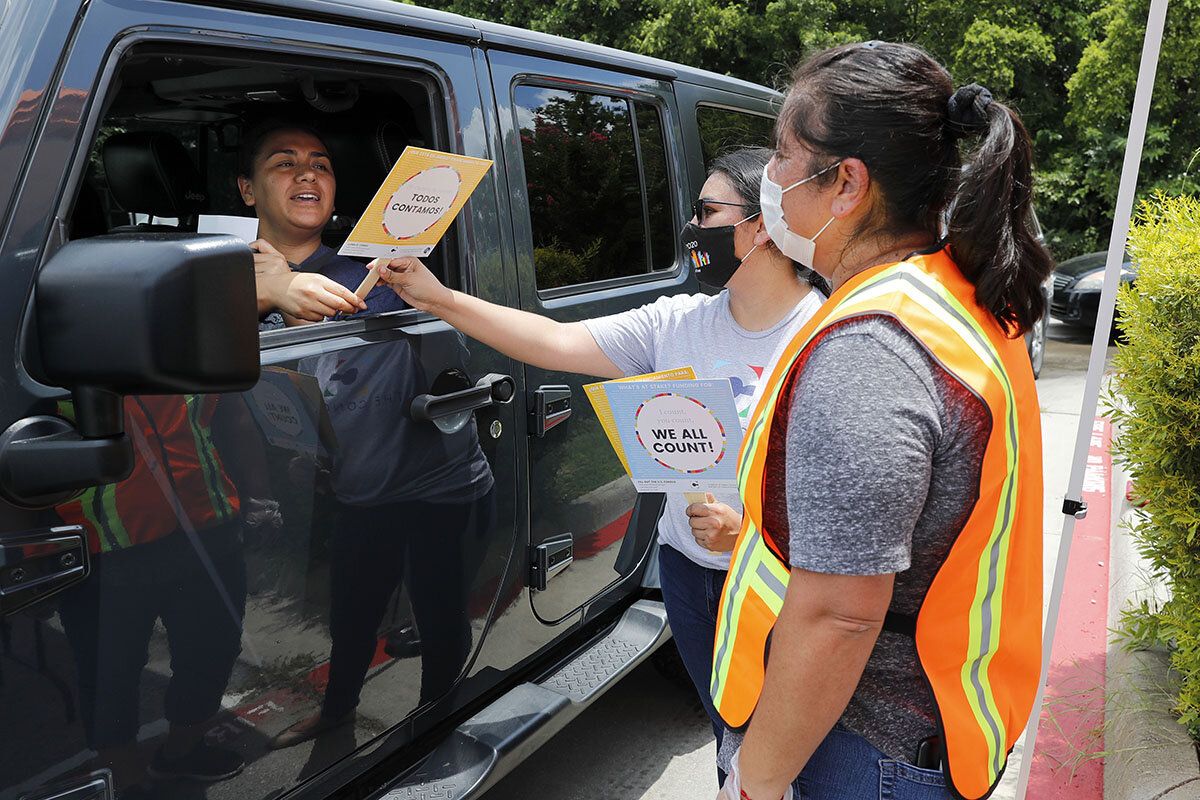

Delays at Census spell trouble for redistricting – and the 2022 election

Census delays are creating hurdles this year for steps that are basic democracy: drawing new political maps, vetting their fairness in courts, and giving potential candidates time to mobilize for the next election.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

When the pandemic disrupted the 2020 census, it set off a chain of delays that now poses a challenge for U.S. politics. The Census Bureau recently said states won’t get their data for redistricting until the end of September – six months later than planned.

Each decade, the apportionment of congressional districts among states is adjusted based on census counts. Even states keeping the same number of House seats must reset their maps based on shifts in population within their borders.

Amid the tightened calendar, watchdogs worry that politicians will rush out new district maps drawn to favor one party, without the usual level of oversight against gerrymandering.

“Everything is at a standstill,” says Kelly Blackburn, Democratic Party chair for Ellis County, Texas, where her party’s hopes could hinge on whether more Dallas-area suburbs are included in the 6th District.

Potential candidates can’t launch campaigns if they don’t know what district they will represent. Amanda Litman, executive director of the political group Run for Something, says “it creates a lot of uncertainty. … Your side of the street could be cut out of the district you are planning to run in.”

Delays at Census spell trouble for redistricting – and the 2022 election

Just once a decade America’s political boundary lines get redrawn – and this year there’s an extra plot twist.

The problem: The pandemic happened to coincide almost precisely with the census timetable for counting America’s population, which determines each state’s share of the 435 seats in the U.S. House of Representatives.

On March 11, 2020, the same day the U.S. Census Bureau published a press release announcing that its survey of households was getting underway, the World Health Organization declared COVID-19 a pandemic. Not three weeks later, the Census Bureau announced that it would be delaying its field operations (a vital part of the process in which census workers follow up with hard-to-reach communities) to reduce the spread of COVID-19.

At an already fraught time, amid deep political rifts and with control of Congress closely divided, the coronavirus pandemic is severely delaying the arrival of new population data to the states. The result could be delays in drawing district maps, potentially threatening normal routines such as candidates deciding to enter primary races for the 2022 elections.

Although the bureau eventually finished its count in the fall, it recently announced that states can expect to receive their data by the end of September – six months later than planned.

In some states with redistricting deadlines written into law, delay is more than just inconvenient – it’s illegal. Ohio’s Constitution, for example, mandates that the state Legislature agree on new districts by Sept. 30, the day the data is slated for release. At least two states – Ohio and Alabama – have already filed lawsuits against the U.S. Census Bureau for the delay.

With states scrambling to redraw maps on a tightened calendar, the process could potentially blow past filing deadlines for congressional primaries in almost every state. Watchdogs worry that politicians will rush out new maps drawn to favor their party, without the usual level of oversight against gerrymandering.

“There will be less time for challenges, and it’s likely that that will encourage some redistricting bodies to get greedy,” says Justin Levitt, a law professor at Loyola University who has written several papers on redistricting and manages the website All About Redistricting.

While the challenges are formidable, he is hopeful states can avoid a political train wreck. “I don’t think [the delay] has to be the disaster that some people have made it out to be,” says Mr. Levitt.

Loyola Law School's All About Redistricting, Wall Street Journal

Seven states gaining seats

It’s not an exaggeration to say that the nation’s constitutionally mandated population count affects virtually every aspect of Americans’ lives, including how more than $675 billion of federal funds will be distributed for things like schools, hospitals, and roads.

Although the detailed census data that states need for redistricting won’t be available until the fall, on April 30 the Census Bureau will confirm which states stand to gain or lose seats. And by December the bureau had already given population estimates hinting at what the new House makeup will look like.

Texas and Florida, which have seen the greatest population growth in the past decade, are expected to pick up three seats and two seats, respectively. Five other states will likely gain one House district (Arizona, Colorado, Montana, North Carolina, and Oregon), while 10 states, including California and several in the Midwest, will likely lose a representative.

But all states (except for those with only one at-large district) must engage in redistricting, given that populations shift within a state and districts are intended to represent equivalently sized populations. And because new district maps can favor one party or the other – ultimately affecting control of Congress – the process is far from simple. Gerrymandering, the “packing or cracking” of certain populations to increase one party’s chance of winning, has plagued redistricting throughout American history.

Voters’ understanding – and corresponding disapproval – of gerrymandering has increased in recent years, with politicians from both parties arguing for reform. Since the last congressional maps were drawn in 2010, voters in at least four states have approved ballot measures or constitutional amendments that allow for a bipartisan commission, rather than the state legislature, to draw the districts.

“There is this spark of interest from the public that redistricting has never had in the past,” says Kathay Feng, national redistricting director with the organization Common Cause.

“It’s not just that legislatures should do the right thing, it’s that regular people are demanding it and that’s totally different.”

Still, citizens and outside groups have increasingly turned to the courts to rule against gerrymandering. After the 2010 census, for example, fewer than a dozen states redistricted without any legal objection to their maps. Citizens and outside groups typically have a full six months to litigate against gerrymandering, says Michael Li, senior counsel for the Brennan Center’s Democracy Program. This year, he predicts, the time for post-redistricting litigation has shrunk to two or three months.

“Litigation about maps is sometimes the only way you get fair maps,” says Mr. Li. “It’s a much shorter time period [this year], which means it’s much more likely that discriminatory things are left in place for the 2022 election.”

The view from Texas’ 6th District

That is, if 2022 congressional elections can even happen on time.

According to the Monitor’s count, the redistricting process took an average of 13 months following the 2010 census. States will have to beat that average this year, once the data arrive on Sept. 30, or the map-drawing process will surpass the primary election filing deadlines for congressional elections in all but three states.

And until they know the new maps, local party officials and organizers don’t know where to focus their resources.

If Texas’ 6th Congressional District, for example, an area south of Fort Worth and Dallas that currently looks like a bottom-heavy number 8, is drawn to include more of the cities’ suburbs, Democrats will have a fighting chance, says Kelly Blackburn, Democratic Party chair for Ellis County, Texas.

“But everything is at a standstill,” says Ms. Blackburn.

Politicians or potential candidates can’t launch campaigns if they don’t know what district they will represent.

“It creates a lot of uncertainty, especially knowing how precisely we expect them to gerrymander,” says Amanda Litman, executive director of Run for Something, an organization that helps young progressives run for office. “Your side of the street could be cut out of the district you are planning to run in.”

And that creates a ripple effect for down-ballot races. First-time candidates may consider running for state representative, for example, if they know that their current state representative is planning on running for a congressional seat instead.

“The most successful first-time candidates are the ones who can start 18 months out,” says Ms. Litman. “The only resource in a campaign you can never get back is time.”

States could – and should – get a head start on mocking up potential district maps without the final data, say experts. In its press release announcing the delay, the Census Bureau suggested states could “begin to design” their new districts with census data published in the past two years.

And among the states with redistricting deadlines by law, officials should proactively ask local courts for a delay, says Mr. Levitt. California officials, for example, already appealed to the state’s Supreme Court and were granted an extension. And as several did for COVID-19, states should consider moving their primary filing deadlines.

Getting it right?

Even before COVID-19, last year’s count was challenging for the Census Bureau. The 2020 count featured the bureau’s first attempt at a primarily digital census, and the Trump administration’s failed attempts to include a citizenship question taxed the bureau’s staff and resources.

But COVID-19 jeopardized the fundamental purpose of the decennial census: to document where and how Americans live.

“College students moved back in with their parents; older kids moved in with the grandparents to take care of them,” says Ms. Feng with Common Cause. “All these different living situations mean that even when the bureau could restart their field operations, they weren’t looking at living conditions that one might normally be in.”

Which is why several redistricting experts say the data delay, while stressful, isn’t inherently bad. The delay ensures that the Census Bureau will do the best count possible by double-checking against duplicates. So given the circumstances, the delay is a “very, very positive thing,” says Mr. Levitt.

“When you take a picture of [the U.S. in] April 2020, that picture looks very odd,” he adds. “It’s not clear how much the delay can fix that picture, but it means they are giving it a shot.”

Loyola Law School's All About Redistricting, Wall Street Journal

First step: Threaten to ban Twitter. Next: A separate Russian internet?

When a society has been integrated with the rest of the world, even if not always comfortably, it is often unrealistic if not impossible to sever that connection.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Russian communications watchdog Roskomnadzor is threatening to shut down the Russia operations of internet giant Twitter next month, in what is widely seen as an opening gambit to impose domestic content controls on foreign-based social media platforms.

Moscow appears to have a broad design, outlined in a recent “sovereign internet” law, that would enable Russian authorities to completely disconnect the Russian digital space from the global internet, or to pick what information is allowed in. A recent exercise that saw Roskomnadzor impose a 10% slowdown on Twitter’s domestic traffic suggests that they may be working toward such a goal.

But it would come at a cost.

In Russia, 80% of the population are now regular internet users, and they increasingly depend upon it for education, commerce, and news. Roskomnadzor’s muscle-flexing not only slowed down Twitter, but caused massive collateral damage domestically, including slowing the Kremlin’s own website. A Russian cyberspace free of foreign influences would likely alienate millions who’ve grown used to unfettered access to the worldwide net.

“Russia is very much a country of the net, especially the younger generation,” says Mikhail Chernysh of Moscow’s Institute of Sociology. “Russia has more to lose by cutting those connections than it could possibly gain.”

First step: Threaten to ban Twitter. Next: A separate Russian internet?

Russian communications watchdog Roskomnadzor is threatening to shut down the Russia operations of internet giant Twitter next month, in what is widely seen as an opening gambit to impose domestic content controls on foreign-based social media platforms.

On one level it sounds familiar. Social media giants like Facebook, Twitter, and Google increasingly find themselves under attack for their role in hosting and multiplying malicious content, misinformation, and hateful messaging.

Indeed, Twitter’s recent crackdown on U.S.-focused accounts – including that of former President Donald Trump, who was banned for inciting violence around the Jan. 6 riots at the U.S. Capitol – may have emboldened Russian authorities to demand the global microblogging service take similar action against content deemed illegal or disruptive in Russia.

But Moscow appears to have a broader design, outlined in a recent “sovereign internet” law, that would enable Russian authorities to completely disconnect the Russian digital space from the global internet, or to pick and choose which information streams are allowed in. Russian authorities deny that is the intention, except in an emergency. Nonetheless, a recent exercise that saw Roskomnadzor impose a 10% slowdown on Twitter’s domestic traffic over its refusal to remove about 3,000 posts that were deemed offensive, suggests that they may be working toward such a goal.

Experts say that Russia lacks the technological might and market clout that has enabled China to construct a “Great Firewall” to filter out undesirable content at will. An attempt by Roskomnadzor two years ago to shut down the messaging app Telegram for refusing to share its encryption keys with security forces ended in humiliating defeat. Today, Telegram is the most widely used messaging service in Russia, openly employed by Kremlin officials, state media, and opposition leaders alike.

More seriously, Russia is a country in which 80% of the population are now regular internet users, and they increasingly depend upon it for their educational endeavors, commercial needs, and news consumption, as well as social networking activities. Roskomnadzor’s recent internet muscle-flexing not only slowed down Twitter, but caused massive collateral damage domestically, including slowing down the Kremlin’s own website and those of leading Russian internet companies. The idea of creating a self-sufficient Russian cyberspace free of foreign influences might appeal to Russian nationalists, but would likely alienate millions of people who’ve grown used to unfettered access to the worldwide net.

“Russia is very much a country of the net, especially the younger generation,” says Mikhail Chernysh, an expert with the Institute of Sociology at the Russian Academy of Sciences in Moscow. “The idea of a sovereign internet is mostly defensive; in case the outside world cuts Russia off, we could keep functioning. So much these days, including the financial system, trade, and almost every form of exchange, depends on digital links. Russia has more to lose by cutting those connections than it could possibly gain.”

“It’s about controlling the media feeds”

Severing Russia from the internet would also crush the ambitions of the country’s growing IT sector, whose big champions like Yandex – often called Russia’s Google – and the Facebook-like V’Kontakte have big plans to expand around the world. In the world of Russian social media, foreign platforms like Facebook and Twitter do not have much market penetration, although they do tend to attract the most educated and opposition-minded part of the population.

“The Russian government has started with Russian companies, like Yandex, V’Kontakte, Odnoklassniki, and forced them to accept some content rules,” says Alexander Isavnin, a professor at Free Moscow University, an alternative university devoted to academic freedom. “These companies now cooperate and filter content as they are told. Russian authorities want to compel foreign platforms to behave the same way in the Russian market. Mostly they want to be able to prevent opposition leaders like Alexei Navalny from being able to instantly spread their messages.

“While only about 3% of Russians use Twitter, opposition leaders use it a lot and consider it to be the last bastion of free speech,” he says. “It’s about controlling the media feeds to people, not about protecting the internet and keeping it sovereign.”

Vladimir Putin recently slammed the influx of malignant content from outside the country, referencing messages that glorify drug use, suicide, and child pornography. “We all unfortunately know what the internet is and how it’s used to spread entirely unacceptable content,” he said, arguing that it should be governed by “moral laws.”

But experts say most of Roskomnadzor’s demands on Twitter relate to the opposition’s use of the platform during the recent spate of street demonstrations in support of Mr. Navalny, and particularly appeal to minors to take part in the protests.

Since Roskomnadzor’s failure to ban Telegram, new legislation has compelled Russian servers to install special equipment, known as deep packet inspection, that enables special services to monitor content, and to block or re-route traffic as needed.

Andrei Soldatov, author of “The Red Web,” a history of the Russian internet, says the main purpose of the sovereign internet laws is to control the domestic digital space, and possibly black out regions of the country if trouble breaks out.

“Russian authorities understand that the most explosive content is generated inside the country, not outside,” he says. “And it’s not necessarily things posted by opposition activists that pose the challenge. Nowadays, if an event happens in some region like, say, mass protests, there will be huge numbers of ordinary witnesses posting content about it directly to the web. The architecture that is now in place will enable authorities to isolate that region from the rest of the Russian internet to slow the spread of such information.

“It’s not about cutting cables anymore,” says Mr. Soldatov. “The goals are much more subtle.”

Doomed to fail?

One solution to the global spread of misinformation and malicious content might be an international body that sets standards and enforces compliance across platforms, says Andrey Yablonskikh, a partner at the International Academy of Digital Communications in Moscow.

“At the moment there is no concept of global regulation of social networks,” he says. “Each country has its own laws and norms, which are different from everywhere else. So now we see these efforts to block networks or accounts on a piecemeal basis, and it’s often controversial. Until there is a global body to regulate this, social networks are going to keep experiencing these difficulties.”

In any case, Roskomnadzor’s efforts to intimidate Twitter are probably doomed to fail, say experts.

“Twitter isn’t very important in Russia, but if Roskomnadzor wants to move against other platforms, like YouTube, TikTok, or Facebook, there will be serious consequences,” says Sarkis Darbinyan, a lawyer and co-founder of Roskomsvoboda, a group that works for internet freedom.

“Russia is deeply integrated into internet commerce, and the largest Russian corporations depend on these networks for advertising,” he says. “And the social impact would be devastating. It might result in a further radicalization of Russian society, because even politically neutral people will be incensed by such measures. Russians are not ready to give up their favorite internet services.”

Points of Progress

Cacao without deforestation? Land reform in Brazil bears fruit.

Seeds of progress can take time to mature. This week’s roundup of global progress includes a decadeslong effort to restore groundfish populations in California and a breakthrough in earthquake and tsunami detection technology.

Cacao without deforestation? Land reform in Brazil bears fruit.

1. United States

Despite initial pushback, California’s aggressive fishery management regulations are proving effective as West Coast groundfish populations rebound. Three decades ago, plummeting fish populations inspired the state to push out new science-based management policies, including no-fishing zones and catch limits. It’s among the strictest programs assessed in a new University of Washington study, and initially met resistance from commercial fishing operators. But researchers say the challenges were worth it, with 9 of the 10 at-risk fish populations returning to sustainable levels. The 10th species, the yelloweye rockfish, is also on track for recovery.

Today, commercial operators are largely on board with the effort, and recreational fishermen are thrilled with the ever-improving waters. “It was difficult at the beginning of the program,” said Ken Franke, president of the Sportfishing Association of California. “But the outcome – I think everybody’s happy with how it’s evolved.”

2. Brazil

By reintroducing a traditional agroecological system and pushing for land reform, a community has turned once-abandoned cacao farms into a source of financial independence and food sovereignty. A group of farmers has reestablished the practice of cabruca, an agricultural approach that plants cacao trees amid the forest, instead of clear-cutting the land. Much of the cultivated land in Bahia state is dedicated to monocrops, preferred by the state government and major industries, but cabruca requires retention of a minimum of 50 native tree species. The farmers hope the diversity achieved through cabruca will ward off a catastrophic fungus that killed cacao trees and forced 30,000 farms into bankruptcy in the 1990s. Their efforts have paid off: Since 2008, the farmers’ income has more than doubled, and they are selling to major chocolate brands around the country.

3. United Kingdom

A social enterprise focused on creating a more sustainable food system is expanding across Scotland. Locavore has two zero-waste, organic supermarkets in Glasgow, and just launched a plan to establish eight more locations. A leader in sustainable food vending, Locavore is known for limited packaging, a focus on local producers, and famously piloting the country’s first milk vending machine, which reportedly saves about 100 plastic bottles a day.

The group expects to create 90 new jobs and become a carbon-negative company in two years. The enterprise receives support from the government’s Zero Waste Scotland initiative, and the $4 million needed for its rapid expansion will come from a combination of loans and crowdfunding.

Glasgow Times, The Herald, Huffpost UK

4. Sri Lanka

In an environmental justice win, Sri Lanka’s Forest Department started a $5 million replanting program to be paid for by the government official who was responsible for unlawfully clearing protected forestland. A court found government minister Rishad Bathiudeen liable for illegal development of part of the Wilpattu Forest Complex (WFC), upholding the “polluter pays” principle set forth by the United Nations Rio Declaration.

The ruling follows a five-year legal battle over the 3,000-acre portion of the WFC that was cleared for resettling people who were displaced after the country’s civil war. Led by the Center for Environmental Justice, lawyers successfully argued that to proceed with such a construction project, the government needed to formally rescind the protected status granted in 2012, which never happened. The courts agreed that officials had a legal and moral obligation to protect the forest as promised. Environmental activists have celebrated the Wilpattu ruling, but acknowledge the path forward is difficult, since the WFC is located in one of Sri Lanka’s driest regions, prone to long droughts, and new trees will require years of maintenance.

5. Sub-Saharan Africa

Air pollution is dropping in northern sub-Saharan Africa, despite rapid economic growth. Typically, air pollution spikes in middle- and low-income countries experiencing urbanization, but researchers found the opposite in a region stretching from Senegal to Kenya in the midst of a population boom.

Using NASA satellite data, they found there was actually a striking drop in the level of harmful nitrogen oxides, a combustion byproduct, likely because transportation and industry emissions were offset by a decline in farmers using fire to clear their land for planting. North equatorial Africa is home to about 70% of the globe’s biomass fires, which mix with urban pollutants to release toxins in the air. For countries where population is growing rapidly, the research offers hope. This study “provides an important tool for filling some of these data gaps in Africa where there is a dearth of air pollution studies at multiple levels,” said environmental researcher Andriannah Mbandi, who is based in Kenya.

World

Using an existing vast network of underwater fiber optic cables, researchers have developed a new method of detecting earthquakes and tsunamis. Most of the earth is covered in water, and because ocean bottom seismometers are expensive and challenging to maintain, experts have long sought a way to use telecommunications cables to improve warning systems.

In their study, Caltech seismologists and Google optics experts focused on the light traveling through the 6,500-mile Curie Cable, which cuts through the Pacific Ocean from Los Angeles to Valparaiso, Chile. The deep sea is a generally still and temperature-stable environment, so when plates shift or storms create massive waves, the dramatic changes in the light’s polarization stand out – turning the entire cable into a massive sensor. For an earthquake miles offshore, which can take several minutes for land-based machines to detect, the change would appear within seconds in the cable’s polarization, meaning more time for communities to prepare. Over nine months, the research team detected about 20 moderate-to-large earthquakes along the Curie Cable, although there were no confirmed tsunamis during that period. Now, the team is working on a machine learning algorithm that would root out other potential disturbances, such as a crossing crustacean or ship, improving overall readings.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

It’s comeback time for America’s pastime

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

Forget the blooming crocuses. The truest harbinger of spring in the United States must surely be Major League Baseball’s opening day, this year on April 1. That’s when 30 teams across North America begin a rhythmic marathon of games – day in, day out; week in, week out – until October yields the World Series.

Last year professional baseball almost succumbed to the pandemic altogether. But eventually an abbreviated season took place. During the offseason some stadiums were converted into vaccination centers. Now they’re about to revert to their proper use: hosting baseball games.

Last year pro sports were touted by some as a needed distraction from trying times. This year baseball may become more of a celebration than a distraction, a return to something approaching normalcy. The biggest change will be the presence of fans, young and old, in the stands, the return of the traditional day out at the ballpark.

Baseball 2021 is about to arrive: Play ball!

It’s comeback time for America’s pastime

Forget the blooming crocuses. For many American sports fans, spring’s arrival is announced by college basketball’s March Madness tournament, or an early April visit to the verdant fairways of the Masters golf championship in Augusta, Georgia. Yet the truest harbinger of spring must surely be Major League Baseball’s opening day, this year on April 1.

That’s when 30 teams across North America begin a rhythmic marathon of games – day in, day out; week in, week out – until October yields the World Series. Last year professional baseball almost succumbed to the pandemic altogether. But eventually an abbreviated season yielded playoffs and crowned a champion, the Los Angeles Dodgers. During the offseason some stadiums were converted into vaccination centers. Now they’re about to revert to their proper use: hosting baseball games.

If the 2021 season won’t be a total return to “normal,” it will head a good way in that direction. Last year, with fans banned from almost all games, the empty stands left every crack of the bat with a hollow ring to it. Where were the cheers?

Sports at its most fulfilling thrives on affection and joy between teams, players, and fans. This year, most baseball clubs will allow a few thousand spectators, perhaps at 10% to 25% capacity. The Texas Rangers plan to fill all their seats on opening day, much to the joy of one of their biggest fans, former President George W. Bush, and to the chagrin of those favoring a more cautious approach.

Fans will still have to wear masks (except when eating) and practice social distancing. Players will wear face masks when not on the playing field. But in general the games should have much of the comforting familiarity of life before 2020.

Last year pro sports were touted by some as a needed distraction from trying times. This year baseball may become more of a celebration than a distraction, a return to something approaching normalcy.

Fans may even resume old-fashioned baseball talk: What teams or players will delight us? Disappoint us? What new name should Cleveland's team adopt? Calling them the Cleveland Spiders would have historical roots.

Attention may turn to how to improve the game itself. In today’s baseball, batters too often either strike out, walk, or hit a home run. Those three outcomes deprive fans of seeing exciting action on the field when a ball is put into play.

As part of an effort to appeal to a younger demographic of fans who have fallen away from baseball, minor league teams will experiment with rule changes, including enlarged bases (reducing injuries from player collisions and perhaps creating more thrilling base-stealing attempts). In one minor league, defenders will not be allowed to shift their positions for each batter. (Teams now take advantage of advanced statistical analysis to predict where batters are most likely to hit the ball and place more defenders there.)

But the biggest change will be the presence of fans, young and old, in the stands, the return of the traditional day out at the ballpark.

Baseball 2021 is about to arrive: Play ball!

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Humility that empowers

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Laurie Toupin

Stung by a friend’s comment that she needed humility, a woman turned to the Bible and the writings of Mary Baker Eddy for a closer look at what it truly means to be humble – which prompted an empowering shift in her thinking.

Humility that empowers

“Do you know what you need?” a friend recently asked.

“No, what?” I replied.

“Humility,” she answered.

Ouch ... that hurt. I thought I was humble – but to say so wouldn’t have proved it!

When I got home, I considered the most humble individual I could think of: Jesus. I picked up my Bible and read how Jesus refused to personally take credit for any of his works or even words. For instance: “The Son can do nothing of himself, but what he seeth the Father do: for what things soever he doeth, these also doeth the Son likewise” (John 5:19). He credited God as the source that inspired all he said and did.

Next I looked up “humility” in the writings of Mary Baker Eddy, the discoverer of Christian Science. Two passages that stuck out to me were from “Miscellaneous Writings 1883-1896”: “Experience shows that humility is the first step in Christian Science, wherein all is controlled, not by man or laws material, but by wisdom, Truth, and Love” (p. 354), and “Humility is the stepping-stone to a higher recognition of Deity” (p. 1).

I realized that humility has a profoundly spiritual meaning that I had been missing: God-inspired action. Seen this way, humility is a recognition of God’s role as the creator who governs the universe, an understanding and appreciation of all the good and harmony God constantly imparts to everyone. When we’re letting God, rather than self, be the primary impetus for what we do and think, then we’re expressing true humility, and we experience how empowering this can be.

I decided to try to put this into practice, and an opportunity came up when I got to work. I was excited because I had done a lot of prepping for a project I was to present that day. But then a colleague mentioned that she had done some additional work on the project and began telling of her approach, which appeared to negate everything I had done.

I was indignant! I felt I had done a lot of work for nothing. And it wasn’t even her project!

Before saying anything, though, I stopped and reached out humbly to God. I listened for God’s direction. I found myself saying how much I liked her idea, and maybe we could combine the two approaches – which we did, and it came out better than either of us had planned.

There were a couple of other times that day when I noticed myself getting flustered because I felt taken advantage of, or that my time or value had not been recognized. Each time, though, I was able to recognize that anger, jealousy, or feeling put out were not from God, infinite good – therefore, they were not me. The Bible tells us that we are created in the image of God, who is Spirit. Being humble enough to acknowledge God as the creator of all we truly are as His sons and daughters enables us to overcome unhelpful feelings and replace them with loving, God-directed actions that bless both us and those we interact with.

I hadn’t realized how much this quality played in everyday life! Up until then, I had thought of humility as not bragging about how great one’s children are or how much we recycle, or even as just letting others walk all over us. But humility is so much more. It isn’t just sitting back and letting others go first, but rather it is putting God first – viewing others as God sees them and listening for God’s direction and then acting upon it. Rather than just reacting to a situation, it is saying, “Not my will, but Yours, God, be done.” It is getting opinions and biases out of the way and allowing God to work through us to bless.

We’re all capable of cultivating more humility, because it is a quality that we already possess as God’s children. It is natural for us to love, turn to, and hear our divine Father-Mother, and act accordingly.

So, my friend, thank you for telling me that I needed humility. You were so right!

A message of love

Farm team

A look ahead

Have a great weekend, and thanks for joining us today. On Monday, we’ll be kicking off a new series on the thorny challenges testing U.S. democracy, and how the country might rise up to meet them.