- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Why Yuri Gagarin’s brave spaceflight resonates 60 years later

On April 12, 1961, cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin launched skyward in a rocket, orbited the Earth once, and returned safely. That 108-minute journey made him the first human to travel into outer space, a source of national pride for the Soviet Union and a spur to the U.S. space program. Weeks later, President John F. Kennedy declared the American goal of landing a man on the moon by the end of the decade.

Back then, at the height of the Cold War, U.S.-Soviet competition in space was fierce. But, as Kennan Institute Director Matthew Rojansky points out, space soon became an arena for cooperation. There’s the Apollo-Soyuz project in the 1970s, the International Space Station in more recent years, and NASA’s reliance on Russia to ferry U.S. astronauts to the space station after the United States canceled its shuttle program in 2011.

“Whether this kind of cooperation has kept relations here on Earth from going off the rails is harder to say,” Mr. Rojansky, who will host a webcast Tuesday on the Gagarin legacy, writes in an email. “But it has certainly been a positive factor, and one we should seek to continue in the years ahead, despite disagreements in other areas.”

Indeed, 60 years after Gagarin’s brave flight, citizens the world over can celebrate this achievement. And when the National Air and Space Museum in Washington reopens, visitors can view perhaps the ultimate symbol of U.S.-Russian cosmic friendship: spacesuits of both Gagarin and John Glenn – the first American to orbit the Earth – displayed side by side.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

As Myanmar protests continue, a glimmer of greater unity

Signs are growing that Myanmar’s coup and brutal military crackdown are forging common cause between ethnic minorities and the majority Bamar population, as old animosities give way to new political imperatives.

Since Myanmar’s military coup on Feb. 1, nationwide protests have erupted against the junta, prompting a brutal crackdown. More than 600 people have been killed in the crackdown and nearly 3,000 detained, including civilian leader Aung San Suu Kyi and other senior officials.

For the first time, experts say, military cruelty has been laid bare for Myanmar’s young protesters from the dominant Bamar ethnic group – allowing them to understand the long-standing suffering of minorities such as the Karen, Rohingya, and others. Armed groups from many of the communities have been fighting the Tatmadaw, as Myanmar’s military is known, for years.

That newfound shared sympathy could help foster support, experts say, for the country’s deposed civilian leadership to forge a new federal government and army with ethnic minority representatives.

“You have ethnic Bamar saying, ‘We heard all these years the ethnic minority groups like the Rohingya complain about the military brutalizing them. We tended to dismiss it to some extent. Now we’re feeling it and we’re sorry we didn’t speak up sooner on your behalf,’” said Scot Marciel, former U.S. ambassador to Myanmar, speaking in an unofficial capacity at a World Affairs Council event this month.

As Myanmar protests continue, a glimmer of greater unity

Like her mother and grandmother before her, Paw knows what it is like to flee assaults from Myanmar’s military – running from thatched-roof village huts into the jungle to huddle without food or warmth, yet afraid to make a fire lest it alert soldiers to their whereabouts.

“Not long ago, the military used planes and airstrikes and dropped bombs in the Karen area,” says Paw, a member of Myanmar’s Karen ethnic minority and a relief worker who now helps thousands of displaced people. “You can’t find anyone in the villages now. They are all in the jungle or digging trenches to hide in,” she says by phone from the Thailand-Myanmar border.

For decades, Myanmar’s military has been battling Karen fighters and a slew of other ethnic armed groups around the country that seek greater autonomy, promised but never realized after the country’s independence in 1948. But despite the military’s recent escalation of attacks on Karen villages, today Paw sees a glimmer of hope – mainly because a far broader swath of Myanmar’s population is now confronting the military’s wrath and so can empathize.

“They know the Burmese military treats the Karen and other ethnic minority groups cruelly. ... They know that now, because the military also treats them badly,” says Paw, who asked to withhold her real name for her protection.

“Now they know we are suffering for more than 70 years, that we had to flee since our grandparents until now,” she says. “So we are a little bit happy.”

Since Myanmar’s generals overthrew the elected civilian government in a Feb. 1 coup, nationwide protests have erupted against the military junta. In response, the Tatmadaw, as the military is officially known, has launched a brutal crackdown. For the first time, experts say, the Tatmadaw’s cruelty has been laid bare for Myanmar’s young protesters – allowing them to understand the long-standing suffering of ethnic minorities such as the Karen, Rohingya, and others.

“The coup ... was the catalyst for a change in perspective and mindset, because now the regime isn’t just killing Rohingya children and burning them alive. They are actually doing that to their own people,” says Steve Gumaer, president of Partners Relief & Development, which has worked in Myanmar for 27 years.

This shared sympathy, in turn, helps foster support for the uphill political push by the remnants of Myanmar’s deposed civilian leadership to forge a new federal government and army with ethnic minority representatives and their armed wings – a framework that, if successful, some analysts argue could help prevent a drawn-out civil war or failed state.

If mounting pressure on the Tatmadaw starts to shake it, “you really need to have something to step in and fill that gap,” says Jason Tower, country director for the United States Institute of Peace.

Otherwise, “you have a scenario where you potentially end up with four or even five fronts of ethnic armed groups combating the Tatmadaw from all directions,” he says. “That’s where things get really ugly.”

Rethinking the threat

For years, Tatmadaw propaganda has promoted Buddhist nationalism among Myanmar’s dominant Bamar ethnic group, which makes up two-thirds of the population, while fueling divisions with ethnic minorities that inhabit border areas.

When the military waged a campaign against Myanmar’s Muslim Rohingya minority in 2017, forcing around 800,000 to flee to Bangladesh in what the United Nations called a “textbook example of ethnic cleansing,” many Bamar believed propaganda labeling the Rohingya as a threat.

But post-coup, Myanmar’s public sees the military as the real threat, experts say. “It shocks me how quickly it’s being dismantled – the racism and the nationalism,” says Mr. Gumaer. “I think it’s because the military took their gloves off and applied the same tactics – tactics that they apply in the minority states ... to their own people,” he says, referring to the Bamar. More than 600 people have been killed in the crackdown and nearly 3,000 detained, including civilian leader Aung San Suu Kyi and other senior officials.

In recent weeks, many within the Bamar community have been voicing regrets for their past indifference or animosity toward the Rohingya and other ethnic groups. Meanwhile, members of ethnic minority groups – including the Rohingya in refugee camps in Bangladesh – are joining or cheering on the anti-coup protesters.

“One positive that’s come out of this is that you have ... the beginning of a national dialogue about how should we treat people from different communities – that’s long overdue,” says Scot Marciel, who served as U.S. ambassador to Myanmar from 2016 to last year.

“You have ethnic Bamar saying, ‘We heard all these years the ethnic minority groups like the Rohingya complain about the military brutalizing them. We tended to dismiss it to some extent. Now we’re feeling it and we’re sorry we didn’t speak up sooner on your behalf,’” said Ambassador Marciel, a visiting scholar at the Walter H. Shorenstein Asia-Pacific Research Center, speaking in an unofficial capacity at a World Affairs Council event this month.

Push to cooperate

At the national level, this shift in sentiment is propelling an alignment of political goals between ethnic groups that have been fighting for self-determination, and the broader public’s overarching desire to oust the military junta.

Talks are ongoing between leaders of ethnic communities and a group of elected lawmakers who avoided detention and are working in hiding, known as the CRPH.

Last week the CRPH announced the abolishment of Myanmar’s 2008 Constitution, which guaranteed the military significant powers, including control over key ministries and a quarter of seats in parliament. In its place, the representatives adopted a charter with the goal of creating a “Federal Democracy Union” that would eradicate dictatorship, bring peace, and grant “equal rights and self-determination” to all ethnic nationalities.

Organizations representing Myanmar’s main ethnic groups, including the Shan, Karen, and Rakhine, are seizing the opportunity to overcome differences and work with the CRPH to create a new federal constitution.

Public support for a federal system is surging since the coup, Sai Leik, spokesman for the Shan Nationalities League for Democracy, told the Myanmar Now news outlet this week. “When a lot of people in Myanmar’s mainland come to understand that federalism is not separatism and it can lead to greater unity, we should push the idea harder.”

Thaik, a member of the Shan people who works in Shan state, says he’s witnessed an important shift toward “more unity between Shan and Bamar and among different ethnic groups.” “People are talking a lot about federal democracy,” says Thaik, who asked to withhold his real name for his protection.

Attitude shift

Some major ethnic armed organizations – such as the Karen National Union – have also signaled a willingness to join forces in creating a federal army.

Together, the ethnic armies have an estimated more than 100,000 soldiers, compared with the Tatmadaw’s 350,000. “It would definitely cause a recalibration of the Tatmadaw thinking if the EAOs [ethnic armed organizations] unify,” says Jonathan Liljeblad, a Myanmar native who has taught and consulted about human rights and civil society in Yangon and ethnic areas since 2014.

To be sure, mistrust is unlikely to end overnight, but a federal government and army could begin with a few key players and build from there, says Mr. Tower of the U.S. Institute of Peace. Indeed, scattered reports from inside Myanmar indicate the ethnic armies are attracting unusual support and recruits, with some protesters leaving the cities to take refuge, receive military training, and enlist with ethnic forces.

By drawing troops away from urban areas, “the ethnic armed groups are sort of easing the burden on the young people protesting,” one activist, who requested anonymity, told the Monitor by phone from Yangon recently.

“There’s now a new appreciation for both the suffering that a lot of the ethnic members of the population have been through, as well as an appreciation for the steps the Karen and other groups are taking to offer space, to offer protection, and to fight back,” Mr. Tower says.

For Paw, this marks a welcome, 180-degree shift in attitudes toward minorities.

In the past, she says, Bamar people believed “ethnic groups were like terrorists and rebels,” but now, “they say they were blindfolded by the military terrorists.” As the Bamar realize the ethnic minorities were acting in self-defense, “they feel sorry and feel like they don’t have the right to ask for forgiveness,” she says, “but they will help us in the future.”

The Explainer

Are vaccine passports legal in the US? Five questions.

Vaccine passports have become the latest question to divide the U.S., raising charged legal and ethical questions. The law is clear. The ethics are not.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

The desire to revive the economy and cultural life of the country safely is coming into conflict with privacy and civil liberties concerns.

With about a quarter of the U.S. having been vaccinated, some states, businesses, and schools are considering tools to track individuals’ status – also known as “vaccine passports.” Supporters say it would help schools and businesses reopen safely. Critics say it infringes on individuals’ health choices.

A 1905 Supreme Court case ruled that state governments may mandate vaccinations to protect public health. But the current high court has shown a particular concern for infringements on religious freedom, including on pandemic-related restrictions on religious services. If there are mandates without clear exemptions for sincere religious beliefs, it wouldn’t be surprising to see the justices step in.

And some facts are different this time. The FDA had never granted emergency use authorization for a vaccine for an entire population until this pandemic, for example. Two lawsuits filed so far make that central to their arguments.

“Reasonable minds can differ I think on whether a mandate would be appropriate” for an emergency vaccine, says Dr. Eric Feldman, a professor of medical ethics and health policy. “It’s an issue on which we have no precedent.”

Are vaccine passports legal in the US? Five questions.

It’s become the latest question dividing the United States, pitting desires to revive the economy and cultural life of the country safely against privacy and civil liberties concerns.

With about 20% of the U.S. having been vaccinated to date, some states, businesses, and schools are considering tools to track individuals’ status – also known as “vaccine passports.” Supporters say it would help schools and businesses reopen safely. Critics say it infringes on individuals’ health choices. Israel has implemented them, and many European nations are looking to do the same as summer approaches.

Here in the U.S., the law is relatively clear. The ethics are not.

Can the government do this?

Legally, with proper exemptions, it seems so. In terms of the federal government, however, the Biden administration flatly dismissed the idea this week.

“There’ll be no federal vaccinations database and no federal mandate requiring everyone to obtain a single vaccination credential,” said Jen Psaki, the White House press secretary, at a Tuesday press conference.

State governments have more legal latitude to implement such programs owing to Jacobson v. Massachusetts, a 1905 Supreme Court case. Massachusetts could mandate smallpox vaccinations to protect public health, the court ruled then, striking a balance between individual liberty and the common good that has been broadly upheld ever since.

“Jacobson says, yes we have that right [to civil liberties], but it’s not an unlimited right,” says Eric Feldman, a professor of medical ethics and health policy at the University of Pennsylvania Carey Law School.

The fact that current vaccines have only been approved for emergency use represents a new legal wrinkle, experts say, but so far more states – including Texas and Florida – have preemptively banned vaccine passports than have developed them. New York’s “Excelsior Pass,” a voluntary program developed with IBM, is the only vaccine pass to be rolled out so far.

What about private businesses then?

They’ve long been able to place requirements on entry, so long as they’re nondiscriminatory and allow certain exemptions. (See: “No shirt, no shoes, no service.”) We’ve seen many flex this muscle during the pandemic with mask requirements. Vaccine requirements would raise more questions, however.

It’s “clearly lawful” for businesses to require proof of vaccination for employees, and they could probably do the same for customers, says Lawrence Gostin, a public health law expert at the Georgetown University Law Center, in an email.

“I foresee a lot of vaccine mandates for employees, but less so for customers,” he adds. “There are cases where it would be crucial to require customers to vaccinate, such as on cruise ships.”

The Equal Employment Opportunity Commission has laid out guidelines for what employers can require and what they must exempt.

If a disability or a sincerely held religious belief prevents an employee from getting vaccinated, and the company cannot make an accommodation, the agency said, “then it would be lawful for the employer to exclude the employee from the workplace.”

Wait, so someone might not be able to go to work unless they’ve been vaccinated?

Yes, and this is where the ethical and equity questions around vaccine passports get particularly thorny – particularly while vaccines still only have emergency use authorization from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

When you factor in the context that Black and Hispanic people have been vaccinated at lower rates, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention – due in part to both access and hesitancy problems – it gets especially complicated.

“Requiring vaccination as the price of admission is likely to inflame that set of concerns [and] harden vaccine hesitancy and skepticism,” says Dr. Feldman.

“Multiplying the harm of limited access to vaccines by then limiting access to other things would strike many as appropriately concerning,” he adds.

At least 17 public and private passport initiatives are being developed, The Washington Post reported, and as more roll out, those feelings of coercion and hesitancy could intensify, says Jenin Younes, an appellate public defender in New York City.

“It incentivizes people to get a vaccine. But it’s not a good incentive,” she adds. “It creates pressure to get the vaccine. … Public trust [is lost] when people feel coerced.”

Schools already require students to have certain vaccinations, right? How are they approaching this?

Requirements vary by state, but yes, public school systems around the country require students to have some vaccines. (While a majority of states allow religious exemptions, states including California, New York, and Maine do not.) No vaccine has received emergency approval yet for children under 16, but when they do, school districts will likely incorporate it into their mandates, says Professor Gostin.

At schools with strong teachers unions in particular, there will likely be “overwhelming pressure to require the kids coming into schools to be vaccinated,” adds Dr. Feldman.

As for other places of “public accommodation,” like public parks, libraries, and museums, proof of vaccination could be required. Anyone with a disability preventing them from getting a vaccine would be exempt, however.

Could this end up at the Supreme Court? If so, what should we expect?

It’s very possible. The high court has shown a particular concern for infringements on religious freedom in recent years, including on pandemic-related restrictions on religious services. If there are vaccine mandates without clear exemptions for sincere religious beliefs, it wouldn’t be surprising to see the justices step in.

It’s also possible the current court could take a different view of a state’s power to mandate vaccinations than the Jacobson court did in 1905. Some facts are different here than in past cases. The FDA had never granted emergency use authorization (EUA) for a vaccine for an entire population until this pandemic, for example.

Two lawsuits filed so far – one by a corrections officer in New Mexico and one by employees of the Los Angeles Unified School District – make the EUA central to their arguments challenging vaccine mandates.

“Reasonable minds can differ I think on whether a mandate would be appropriate” for an emergency vaccine, says Dr. Feldman. “It’s an issue on which we have no precedent.”

Staff writer Stephen Humphries contributed to this report.

‘An enormous waste’: How stimulus checks play in red-state America

Many conservatives see the relief bill as padded with unnecessary items, further ballooning the national debt even as the economic outlook is improving.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

-

Nick Roll Staff writer

As stimulus checks from President Joe Biden’s $1.9 trillion COVID-19 relief bill make their way to 160 million American households, many Republican voters are showing little enthusiasm for the extra money.

This marks the third time in a little over 12 months that Americans making less than $75,000 are receiving payments from the federal government. Last year, the $2.2 trillion CARES Act passed with near-unanimous support in Congress in the early weeks of the pandemic, winning approval from 79% of Republican and Democratic voters, according to a Gallup Poll.

By contrast, the American Rescue Plan Act, signed last month, garnered no Republican votes in Congress, and Gallup finds only 18% of Republicans nationwide approve of the measure.

To some extent, the growing resistance on the right to the flood of government spending may reflect the fact that it’s now coming from a Democratic, rather than Republican, administration. But with states across the country ramping up vaccination programs and relaxing restrictions, many Americans have also come to feel that the crisis is waning, making federal aid less necessary.

“I got [a check]. I didn’t need it,” says Dave Lannigan, a retiree in Covington, Kentucky. “I think there’s a lot of waste there.”

‘An enormous waste’: How stimulus checks play in red-state America

Oneonta is the kind of place where an extra $1,400 could make a big difference. More than 16% of residents in Blount County live in poverty – a higher rate than the state of Alabama as a whole, which already registers as one of the nation’s poorest.

But as stimulus checks from President Joe Biden’s $1.9 trillion COVID-19 relief bill make their way to 160 million American households, voters here are showing little enthusiasm for the extra money.

“These stimulus checks are just a way of making more people dependent on the government,” says Virginia Russell, who owns the Look of Xcellence hair salon in Oneonta. It’s a view that’s echoed across this conservative county, where former President Donald Trump won 90% of the vote last November, and where tattered Trump 2020 flags still line the central highway.

Ms. Russell admits she felt differently last year, when President Trump signed the $2.2 trillion CARES Act into law. Passed with near-unanimous support in Congress in the early weeks of the pandemic, that relief bill won approval from 79% of Republican and Democratic voters, according to a Gallup Poll. To Ms. Russell and the other women in the Look of Xcellence, it was a necessary measure in an unprecedented time.

By contrast, President Biden’s American Rescue Plan Act, signed last month, garnered no Republican votes in Congress. And while it initially seemed to be popular among both Democratic and Republican voters, Gallup now finds that only 18% of Republicans nationwide approve of the bill.

“There are some people who the stimulus package really helps, sure. But the people who work,” says Ms. Russell, motioning to herself and the other nodding stylists in the salon, many of whom say they have already received their checks, “we are going to be the ones paying for it.”

This marks the third time in a little over 12 months that Americans making less than $75,000 are receiving payments from the federal government: $1,200 from the CARES Act last spring, another $600 from a COVID-19 relief bill in December, and now $1,400. All the stimulus checks have been framed as an effort to boost the economy and help Americans hurt by the pandemic and its impact.

To some extent, the growing resistance on the right to the flood of government spending may reflect the fact that it’s now coming from a Democratic, rather than Republican, administration.

But with states across the country ramping up vaccination programs and relaxing restrictions, many Americans have also come to feel that the crisis is waning, making federal aid less necessary. Either way, the lackluster or even negative responses by many Republican voters to extra money in their bank accounts may be an early indication of the resistance President Biden will face as he tries to win passage of a $2 trillion infrastructure bill and other priorities down the line.

“Some people really need [the money], and you can’t deny them that,” says Dave Lannigan, a retiree who voted for Mr. Trump, standing outside his house in Covington, Kentucky. “But I think there’s a lot of waste there.”

Like Oneonta, Covington is a struggling area in a struggling state: More than 23% of people here live in poverty.

“I got [a check]. I didn’t need it,” says Mr. Lannigan with a shrug. “But I took it.”

Back when Mr. Biden was campaigning for the American Rescue Plan’s passage in late February, he implored congressional Republicans to vote in favor of the bill, citing its widespread support among voters. And he wasn’t entirely wrong. A Quinnipiac poll from Feb. 3 found more than one-third of Republicans supported the relief bill, and more than 60% supported the $1,400 checks.

The ensuing debate about whether to include a national $15 minimum wage in the bill may have led to some souring among Republicans. But after the bill passed, conservative media attacked it in earnest as a “Democratic wish list” masquerading as pandemic relief.

In addition to the stimulus checks and extending unemployment benefits, the relief bill also included payments to parents, $1 billion for Head Start, housing assistance for homeless populations, and more.

“The child care credit, the expansion of the Affordable Care Act – it clearly became a bill that was a train for Democratic priorities in addition to immediate rescue priorities, and that made it much more political, especially in the mind of a lot of voters,” says Maya MacGuineas, president of the nonpartisan Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget.

A stylist at the Look of Xcellence salon compares the stimulus checks to “hush money,” saying they allowed Democrats to “usher other stuff in this bill.”

While some conservative voters may have had mixed feelings about last year’s payments as well, many justified Mr. Trump’s stimulus checks out of a mixture of party loyalty and the scale of the health crisis back then. But today, they say, America is in a different place.

“I feel like the coronavirus is pretty much under control now, and people still are using [COVID-19] as an excuse not to go back to work,” says Alex Lenhoff, a server at the Cock & Bull Public House in Covington. “It’s also creating problems in the job market.”

Steve Locke, who owns Covington’s Zazou Grill and Pub, says he’s having trouble filling open positions at his restaurant. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, nearly 1 million jobs were added in March.

“Every place is short-handed,” agrees Ms. Lenhoff. “We’re short-handed.”

A Trump supporter, Ms. Lenhoff has remained employed throughout the pandemic, but says she received all three stimulus checks.

“I mean, yeah, it was a help. I’ve used it to buy some stuff for my kids and things like that, pay some bills,” she says. “But most of it’s sitting in the bank still.”

“There’s people that need that stimulus check,” says Mr. Locke. “But all of us didn’t need it.”

In recent weeks, President Biden, Vice President Kamala Harris, and their spouses have been touring the nation to tout the relief bill to the American public, in what they’re calling the “Help Is Here” tour. Today, first lady Jill Biden is scheduled to visit Birmingham, Alabama, to explain how it will help alleviate child poverty.

GOP Rep. Gary Palmer, who represents Alabama’s 6th Congressional District, which includes Blount County, voted in favor of the CARES Act in 2020 but against the American Rescue Plan – despite the fact that it designates more than $4 billion for his state.

“I know it sounds partisan but it’s not,” says Congressman Palmer. Mr. Trump’s two relief bills were “focused and transparent,” he says, but Mr. Biden’s “takes advantage of the pandemic and of people to [do] things that they otherwise wouldn’t do on a more transparent piece of legislation.”

“I think it’s an enormous waste of money,” he concludes.

When is a grocery store not a grocery store? When it’s a palace.

Muscovites have fond memories of Eliseevsky, an ornate grocery store famous for full shelves in the shortage-plagued Soviet Union. Its closure underscores how different the consumer world is in modern Russia.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

An iconic Moscow landmark is closing its doors this weekend, and local residents are indulging in some Soviet nostalgia.

Although the Eliseevsky grocery store was internationally famous for its lavish baroque decoration – think gold leaf, marble columns, and crystal chandeliers – locals loved the shop during Soviet times because in a land of perpetual shortages, Eliseevsky was a gastronomic Aladdin’s cave.

The Kremlin kept it that way, as a showcase for visitors of the city’s purportedly excellent provisioning. Since the fall of the Soviet Union, Eliseevsky struggled to reinvent itself as a regular grocery store. But even its lavish interior could not compete with the lower prices and free parking at the new hypermarkets that have sprung up in Moscow’s suburbs, veritable cornucopias of 21st-century consumer capitalism.

Nobody knows what the future holds now for Eliseevsky, its premises and trademark caught up in legal tangles. But “Eliseevsky is an extraordinary place, which holds a lot of historical meaning,” says Irina Levina, a Moscow tour guide. “So there need to be some extraordinary decisions taken about what to do with it.

“It’s hard to imagine the city without it,” she adds.

When is a grocery store not a grocery store? When it’s a palace.

This weekend one of Moscow’s most iconic landmarks, the Eliseevsky luxury grocery store, will close its doors forever, bowing after 120 years to the forces of 21st-century consumer capitalism.

Muscovites have been thronging to the old storefront, a stone’s throw from the Kremlin, for one last look. Some are stepping inside for a selfie against the shop’s extraordinary background of magnificent colonnaded walls, lavish vaulted ceiling, crystal chandeliers, and wood-paneled shelves.

Opened in 1901 in a former 18th-century palace, it served originally as a luxury food shop for pre-Revolutionary, upper-crust denizens of central Moscow. But it saw its heyday in the later Soviet period when, as “Gastronome No. 1,” it acted as a display window for visitors to the Soviet capital to showcase the city’s purportedly excellent provisioning.

In a land of perpetual shortages, Eliseevsky’s shelves were piled high with delicacies unimaginable elsewhere, such as oranges and bananas, coconuts and real coffee.

Foreign tourists usually scheduled a stop at Eliseevsky – they still do – while people from all over the Soviet Union would come to gawk at its palatial interior and snap up some impossibly rare produce to bring to the folks back home.

“My mother used to take me to Eliseevsky as a boy, and I still have the fondest memories of the place. Going there was kind of an escape,” says Mikhail Chernysh, now a researcher at the official Institute of Sociology in Moscow. “I recall a delicious kind of sausage that you just couldn’t find anywhere else. Of course, you had to stand in line for an hour or more to get some, but that doesn’t seem to tarnish the memory.”

Yes, those lychees are real

Since the collapse of the Soviet Union three decades ago, Eliseevsky has struggled to reinvent itself as a regular grocery store. Even neighborhood customers spurned it in favor of convenient supermarkets that offer lower prices and free parking.

Today the variety of goods on display in almost any village grocery shop makes Soviet-era Eliseevsky look impoverished by comparison. Hypermarkets, such as those belonging to the French Auchan chain, have sprung up in most Russian cities, and some older people admit that they still pinch themselves to be sure they are not dreaming up the spectacle of a cavernous shop with high shelves that overflow with every imaginable kind of produce.

Giant shopping malls sprawl through city suburbs too, offering a one-stop-shopping concentration of goods and services, along with enormous parking lots for automobile-obsessed, post-Soviet Russians. Some have even become popular sightseeing attractions, such as the three theme park-like “Vegas” malls on Moscow’s outskirts, one of which sports scale models of the Roman Colosseum and the Leaning Tower of Pisa.

And if you don’t want to go out shopping, web-based delivery services make it possible to order almost anything from a restaurant or supermarket and have it delivered to your door within an hour or so.

“Nowadays the food shortages we grew up with are a distant memory, and Eliseevsky’s claim to exclusivity is long gone,” says Mr. Chernysh. “It’s having enough money that’s the problem today, not the availability of things.”

An uncertain future

Eliseevsky’s woes grew as the ambitious Moscow city government embarked on a massive urban renovation project in recent years. That made driving in the city center even harder than it had been, encouraging residents of the exclusive Tverskaya Avenue neighborhood, near Eliseevsky, to sell up and move to the suburbs.

“There is now a severe shortage of parking downtown, and it’s hard to get to the Eliseevsky store even by taxi, since stopping is forbidden,” says Igor Berezin, a Moscow-based marketing consultant. “So Eliseevsky is mainly a shop for local residents, but there are far fewer of them in that area than there used to be. In fact, many luxury shops in the heart of downtown now find themselves in difficult straits.”

The store’s problems were compounded by a murky 1990’s privatization, which left the city claiming ownership of its premises, while a company that has since gone bankrupt holds the famous Eliseevsky trademark. City officials have promised to preserve the landmark in some form. But as its closure looms, no plan has been made public.

“Over the 20th century, nobody was taking care of old interiors in Moscow buildings, for various reasons,” which makes Eliseevsky a rare and valuable exception, says Alexander Frolov, a coordinator of Archnadzor, a public architectural watchdog. “The status of Eliseevsky as a historic monument stipulates that it must retain a commercial function. Something will have to be worked out.”

The building’s cachet as a tourist attraction is well established, and before the pandemic Moscow was becoming a popular tourist destination, attracting more than 20 million visitors in 2017, including 5 million foreigners. The building’s ornate interior might lend itself to an upscale store for tourists, a restaurant, or perhaps a coffee shop to serve the foot traffic along Tverskaya Avenue, which is heavy in normal times.

“Eliseevsky is an extraordinary place, which holds a lot of historical meaning,” says Irina Levina, a Moscow tour guide. “So there need to be some extraordinary decisions taken about what to do with it. It’s hard to imagine the city without it.”

Is it art? NFTs and the surge of digital ownership.

In the art world, value has traditionally been based upon scarcity. But nonfungible tokens, or NFTs, are monetizing freely available digital items by placing valuation on the idea rather than the possession of a physical object.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

-

By Stephen Humphries Staff writer

NFTs, or nonfungible tokens, are certificates of ownership of a unique digital item such as a video, recording, or cyber artwork.

These digital receipts reside on the blockchain (a digital ledger). Once an NFT has been “minted” – its code permanently woven into the blockchain’s DNA-like digital strands – it can be bought or sold with a cybercurrency. In March, an artist who calls himself Beeple auctioned a mosaic of digital images as an NFT that fetched the equivalent of more than $69 million.

Observers say that the purchase of these digital receipts is best understood as a form of patronage – a monetary appreciation for the idea and the creator behind a piece of cyber art. The value comes in having one’s name associated with the work. That has inverted the traditional model of the art market by attaching value to artworks that are ubiquitous rather than scarce. Consequently, NFTs have rapidly expanded the demand for digital art forms that haven’t always been valued as much as physical paintings, sculptures, and installations.

“Value isn’t based on scarcity anymore – it’s based on virality,” says Wade Wallerstein, co-director of TRANSFER gallery. “The more places that thing exists, the more valuable it is in our current economy.”

Is it art? NFTs and the surge of digital ownership.

In March, Kenny Schachter proclaimed that he’d auctioned off his grandmother on the internet. The digital artist had uploaded an image of his long-deceased matriarch to the web and sold the rights to it as a nonfungible token (NFT). It was a prankish test of the boundaries of a technology that has the art world abuzz.

NFTs are certificates of ownership of a unique digital item such as a video, recording, or cyber artwork. These digital receipts reside on the blockchain (a digital ledger). Once an NFT has been “minted” – its code permanently woven into the blockchain’s DNA-like digital strands – it can be bought or sold with a cybercurrency, currently Ethereum. In March, an artist who calls himself Beeple auctioned a mosaic of digital images as an NFT that fetched the equivalent of more than $69 million.

In the case of Mr. Schachter, “I found myself repeating again and again that everyone and their grandmother were minting NFTs. So it occurred to me, I might as well mint mine,” he says via email. “I immortalized her in the ether, literally.”

The New York City-based artist was making a point about how NFTs have upended traditional appraisals of art. Now, he muses that the several thousand dollar sale may have been too cheap.

The monetary value of expensive fine art is often driven by scarcity and uniqueness. That’s why Parisian galleries started to limit and individually number the prints they sold in the late 19th century. But rarity isn’t an inherent quality in digital art. Cyber artworks are freely accessible online (Beeple’s pricey artwork is on his Instagram account) and infinitely replicable. Yet NFTs allow their owners to claim ownership of an intangible digital asset, which, at its core, consists of computer coding. It doesn’t mean they truly possess that combination of ones and zeros any more than someone could have dibs on 2+2=4.

So what, exactly, are NFT collectors valuing? Observers say that the purchase of these digital receipts is best understood as a form of patronage – a monetary appreciation for the idea and the creator behind a piece of cyber art. The value of the NFT itself comes in the form of bragging rights for having one’s name associated with that cyber artwork. That makes it a collectable asset. The technological innovation has inverted the traditional model of the art market by attaching value to artworks that are ubiquitous rather than scarce. Consequently, NFTs have rapidly expanded the demand for digital art forms that haven’t always been valued as much as physical paintings, sculptures, and installations.

“Value isn’t based on scarcity anymore – it’s based on virality,” says Wade Wallerstein, co-director of TRANSFER, a gallery whose new digital exhibition, “Pieces of Me,” winkingly bills itself as partaking in “the aggregate hype” of NFTs. “The more places that thing exists, the more valuable it is in our current economy.”

As an example, Mr. Wallerstein points to the $590,000 NFT for Nyan Cat. The meme of the flying feline – rendered in basic, Lego-like block form – is fairly well known. That increases its value as an NFT. The owners of such works can boast that the NFT is in their digital wallet on the blockchain. Think of it as the equivalent of the description plate next to a painting in an art museum with the name of the owner who’s loaned it to the gallery.

“A lot of art collectors, as we traditionally think of them, are not really collecting NFTs,” says Brian Droitcour, an associate editor at Art in America. “The people who are collecting NFTs are the people who own a lot of cryptocurrency. And so for them, it’s probably starting an art collection, but it’s also about building a portfolio of assets on the blockchain. We saw with the Beeple sale that that work was bought by MetaKovan [Vignesh Sundaresan], who is a Bitcoin billionaire,” and also holds a large sum of Ethereum.

Traditional, older art collectors may value things that can be displayed in a gallery. But for millennials and Generation Z who have grown up in an increasingly digitized world, ownership of physical objects isn’t necessarily a high priority. Music, movies, books, and photos live in the cloud. So they’re happy to buy NFTs of cybercreations that they carry around on their phones and view on cryptoart platforms such as Foundation.app.

“They are invested in stuff. It’s just not the physical stuff. It’s stuff that they’ve been used to working with their entire life – words and pictures and ones and zeros,” says George Fifield, director of the Boston Cyberarts Gallery and founder of the nonprofit Boston Cyberarts Inc. It goes back to the theories of French American sculptor Marcel Duchamp, says Mr. Fifield, that “art is the idea, not the thing.”

The gap between the traditional art collector and the NFT collector is slightly narrower than before. The world’s two most famous auction houses, Sotheby’s and Christie’s, are now accepting bids for NFTs. And though some famous artists such as David Hockney (who creates art on his iPad) have publicly expressed distaste for the tokens, others such as Damien Hirst have just begun selling NFTs of digital artwork.

Basketball and tweets, too

It’s not just fine artists who are minting NFTs, which are now topical enough that “Saturday Night Live” recently created a sketch explaining them. You can buy NFTs for short videos of NBA stars. (A slam dunk by LeBron James can net $200,000.) They’re the new digital version of baseball trading cards. The rock band Kings of Leon sold tokens for its latest album. Twitter CEO Jack Dorsey sold his very first tweet as an NFT for more than $2.9 million – perhaps the 21st-century equivalent of a Picasso doodle on a napkin that subsequently fetches a fortune. Consequently, some observers claim that NFTs are a speculative bubble. David Gerard, author of “Attack of the 50 Foot Blockchain: Bitcoin, Blockchain, Ethereum & Smart Contracts,” went even further by calling NFTs “fraudulent magic beans” in a blog post. That might explain how someone was able to sell a recording of his flatulence as an NFT for $85.

Part of the culture of the cryptoenthusiasts who mint NFTs has been bypassing the gatekeepers of the art world, says Mr. Schachter, the veteran digital artist and columnist for ArtNet. But now NFT brokerage houses are having to act as gatekeepers themselves. They have suddenly been deluged with requests from late-adopter artists.

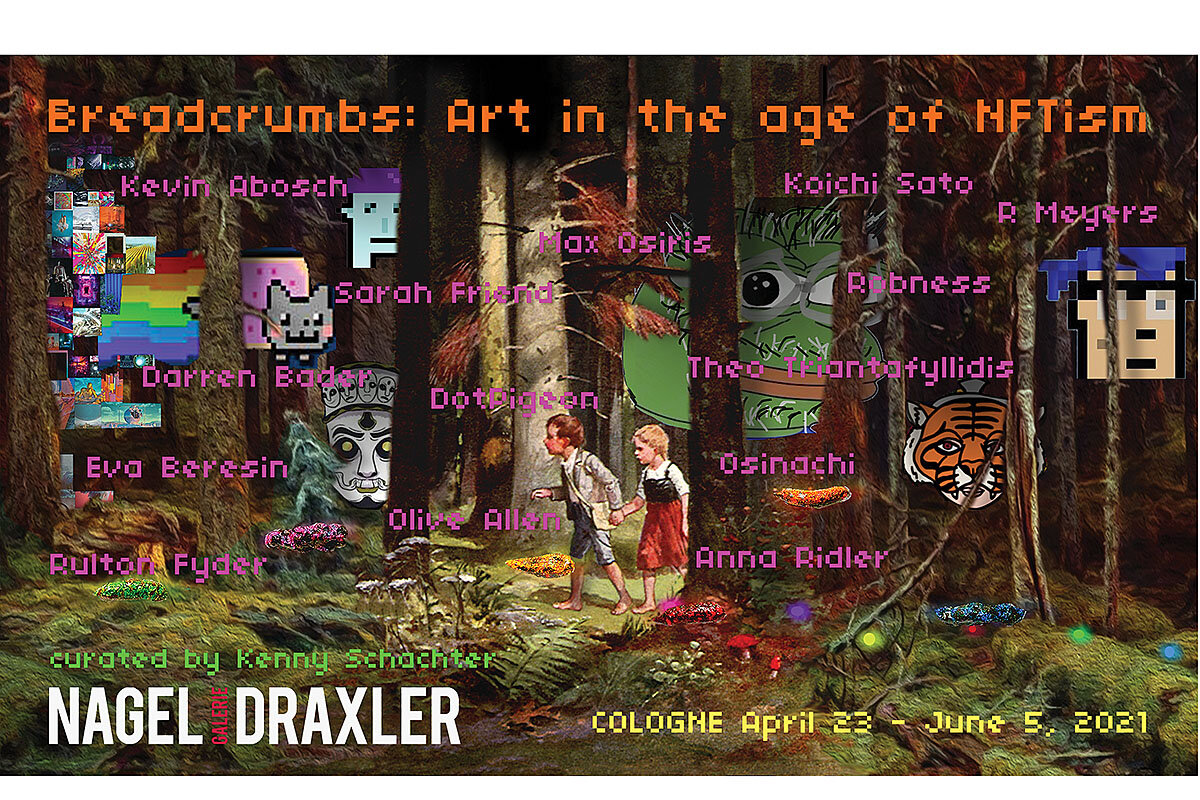

“It’s so important to me democratically, nonhierarchically speaking, that my work is disseminated to all and anyone who wants to see it,” says Mr. Schachter, who is curating an NFT exhibition called “Breadcrumbs,” opening April 23 at the Nagel Draxler gallery in Cologne, Germany. “Breadcrumbs” resembles a traditional art exhibition with physical representations in the form of computer monitors on walls, installations of text, and 3D prints made from digital files. “There’s no metaphysical difference from my art that’s on Vimeo or you buying my NFT. It’s just that you’re buying this certificate of authenticity from the blockchain, or from Nifty Gateway, or SuperRare, and that’s something that can be bought and sold and traded.”

Mr. Schachter says a lot of digital art on the NFT market looks like a screensaver, video game stills, or something painted on the back of a van. But he says that the quality of digital art is only getting better. The vast majority of NFT art is trading for between $100 to $2,000, says the artist. Importantly, the NFTs offer an opportunity for digital artists to make money.

“Our work is real”

Case in point: Longtime digital artist Auriea Harvey only started selling digital tokens for her work fairly recently. She first learned computer coding while studying traditional sculpture at the Parsons School of Design in New York City in the early 1990s. Nowadays, she creates sculptural forms on a computer, brings them into material existence with a 3D printer, and then overlays them with additional organic materials. She sells the original digital sculptures as NFTs. They’re a welcome innovation for digital artists who have often been expected to work for free, says Ms. Harvey. The tokens are a way for lovers of digital art to forge a connection with a wider community as well as the artist.

“People who are going to be the collectors – the true collectors – of digital work are the ones who are really supporting the artists, their concepts, their ideas, and not really thinking about the art objects, but thinking about ‘what is this creator doing?’” says Ms. Harvey, whose current solo show, “Year Zero,” at Bitforms gallery in New York, displays both her physical and digital work.

Like Mr. Wallerstein at the TRANSFER gallery, Ms. Harvey believes that NFTs have great potential for establishing custodial care of digital work. As part of the contract of ownership, digital creators can stipulate that owners are responsible for renewing the websites that the work resides on and that the work will be available online for perpetuity. Even so, Ms. Harvey describes ownership of art via NFTs as a mysterious belief system given that it’s impossible to truly own the original code for the work. Every time you load a browser page with a digital image on it, it’s making a copy of the JPEG, she observes.

“I’m willing to suspend my disbelief enough to like to do that if it furthers the goal, or my goal, of seeing digital art as being seen seriously as a legitimate cultural form,” says Ms. Harvey. “In some ways, it took the money for the art world to listen to what digital artists were trying to say all along, which is that our work is real.”

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

In Ethiopia’s war, a retreat worthy of African ideals

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

Over the past quarter century, Africa’s leaders have steadily erected standards to better manage their own affairs. These are meant to strengthen the rule of law through fair elections, safeguard human rights, and promote prosperity through economic cooperation and joint peacekeeping. Yet nowhere are the impediments to democratic reform in Africa more evident or consequential today than in Ethiopia.

A war in the country’s Tigray province has led to international accusations of atrocities on all sides. After denying his government’s role, the country’s young prime minster, Abiy Ahmed, has made admissions that are rare for an African leader.

“We know the destruction this war has caused,” he said, and vowed that soldiers who committed violence against civilians would be held responsible.

National elections in June will determine what impact the conflict has on Mr. Abiy’s dream of forging a new Ethiopian identity. His attempts to flush out the remnants of a repressive former regime have resulted in humanitarian harm. But on a continent where leaders have too often called for “African solutions to African problems” as a way to excuse bad behavior, Mr. Abiy’s honesty before parliament showed the courage to put Africa’s ideals into practice.

In Ethiopia’s war, a retreat worthy of African ideals

Over the past quarter century, Africa’s leaders have steadily erected standards to better manage their own affairs. These are meant to strengthen the rule of law through fair elections, safeguard human rights, and promote prosperity through economic cooperation and joint peacekeeping. The African Union, the continent’s loose alliance of nations, even established a peer review process to hold politicians accountable to their new principles.

Those efforts seeded expectations. An Afrobarometer survey across 34 countries found 68% of Africans think democracy is the best system of government. The poll showed 74% oppose one-party rule and 72% oppose military rule. But moving democracy from paper to practice remains unsteady. The same year that survey was published, 2019, the Economist Intelligence Unit found nearly half of Africa’s 54 countries were becoming less free.

Nowhere are the impediments to democratic reform in Africa more evident or consequential today than in Ethiopia. The country’s young prime minster, Abiy Ahmed, rose to power three years ago vowing to transform the country from a tense federation of ethnic states into a more united multiethnic democracy. His inauguration ended the 27-year reign of a small minority from Tigray province that achieved notable economic progress but trampled on civil and political rights.

Mr. Abiy’s agenda tracked well with the principles his fellow African leaders have endorsed. He dismantled the former ruling coalition, built a new and more inclusive political party, ended a 20-year military stalemate with neighboring Eritrea, and vowed a new era based on a philosophy of “coming together.” His efforts won him the Nobel Peace Prize.

But there were perils in moving so fast. Last November the ethnic Tigrayan officials he swept from national power pushed back. They attacked a federal military installation in their province after Mr. Abiy called for a delay in a regional election due to the pandemic. He vowed to quash the rebellion and round up its leaders. Instead the conflict intensified and now threatens stability in the broader Horn of Africa. The fighting sent tens of thousands of refugees into neighboring Sudan.

The government sealed Tigray’s borders and shut off communications. Based on evidence from photos, videos, and eyewitness reports, the United States, United Nations, and Amnesty International have alleged that Tigrayan militias, the Ethiopian National Defense Force, and troops from neighboring Eritrea have committed massacres and campaigns of sexual violence against civilians. U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken called the violence ethnic cleansing.

The government initially denied the accusations. In a statement issued March 13, the Foreign Ministry claimed that “nothing during or after the end of the main law enforcement operation in Tigray can be identified or defined by any standards as a targeted, intentional ethnic cleansing against anyone in the region.” Ten days later, Mr. Abiy bowed to international pressure following a visit by U.S. Sen. Chris Coons on behalf of the Biden administration. On March 23, he admitted to parliament the facts he had steadfastly denied for months: firstly, that Eritrean troops had crossed the border and, secondly, that atrocities had occurred.

“We know the destruction this war has caused,” he said, and vowed that soldiers who committed violence against civilians would be held responsible.

Abiy’s statement was a rare public reversal. African leaders seldom admit when their policies have gone wrong or a crisis has spun beyond their control. The prime minister’s contrition, even if compelled, may mark more than a turning point in the war in Tigray.

Declaring victory prematurely in February, Mr. Abiy wrote, “Only an Ethiopia at peace, with a government bound by humane norms of conduct, can play a constructive role across the Horn of Africa and beyond.” National elections in June will determine what impact the conflict has on Abiy’s dream of forging a new Ethiopian identity of national unity. His attempts to flush out the remnants of a repressive former regime have resulted in humanitarian harm. But on a continent where leaders have too often called for “African solutions to African problems” as a way to excuse bad behavior and resist foreign influence, Abiy’s honesty before parliament showed the courage to put Africa’s ideals of democracy and accountability into practice.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Praying for our teenagers

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Elizabeth Mata

From social pressures to pandemic-related stress to specific incidents such as the ongoing violence in Belfast, Northern Ireland, it seems the world’s teenagers have a lot to deal with these days. Each of us can play a part in supporting young people through prayer affirming everyone’s inherent grace, stability, and strength as God’s child.

Praying for our teenagers

Having worked with teenagers for a number of years a while back, they hold a special place in my heart. How often I witnessed their capacity to love and forgive; to persist and transform; to show me through their transparency and innocency where my thinking needed a real perk-up (and sometimes an overhaul).

Stress in the lives of teenagers appears to have increased during the pandemic due to a halt in normal activities and social isolation. When I heard a mother on the news talk about the suicide of her teenage son, I felt impelled to pray. I am convinced that our prayers can bring a healing impress not only to what we’re confronted with individually, but also to what’s going on more broadly.

One of my favorite ways to prayerfully think about young people – and all of us, for that matter – is with a description from the Psalmist in the Bible. “Vigorous and tall as growing plants,” and “graceful beauty like the pillars of a palace wall” are terms the Psalmist used to describe the children of God in “a truly happy land” (Psalms 144:12, The Living Bible).

This lovely poetic depiction is powerful. Understanding the identity of our teenagers as nurtured by God-given qualities like vigor, grace, stability, and balance is a solid foundation from which to pray.

I had attended the Christian Science Sunday School as a toddler, but circumstances interrupted my continuing. I returned at the age of 18 thinking that maybe Christian Science could help me with what seemed like very perplexing questions about life. And it did!

At the time I started going to Sunday School again, I was dealing with anxiety about social situations and feeling really out of step with my peers. I was smoking and drinking, thinking this would help. Well, it didn’t.

I will always remember that first time back to Sunday School when the very kind teacher told me with such love that I was perfect. Whoa – perfect? I hardly felt perfect. But somehow I felt as though I had come home.

As I began to study the teachings of Christian Science, I understood more of what she meant. It wasn’t about trying to make imperfect circumstances perfect. Nor did it include perfectionism where there is angst if everything doesn’t look perfect according to some human standard.

The Bible declares, “And God saw every thing that he had made, and, behold, it was very good” (Genesis 1:31). In this spiritual creation described in the first book of the Bible, which includes not one single element of materiality, the truth of perfection is revealed with ever-unfolding vitality and an abundance of well-being.

In this spiritual creation, God created man – each of us – as “the compound idea of infinite Spirit; the spiritual image and likeness of God,” as stated in “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures” by Mary Baker Eddy, the discoverer of Christian Science (p. 591). Therefore, being perfect means being the exact likeness of the one perfect God, Spirit, where no element of good is lacking, missing, lost, or irretrievable.

That this was my only permanent and true identity started to sink in and make sense. It enabled me to relinquish feelings of anxiety and alienation to a greater degree, because I understood that they weren’t from God.

I no longer felt the need to smoke and drink. Life became happier, even as it was necessary to keep striving to bring this deeper sense of perfection to all my activities.

The Amplified Bible delineates Christ Jesus’ divine standard so beautifully: “You, therefore, will be perfect [growing into spiritual maturity both in mind and character, actively integrating godly values into your daily life], as your heavenly Father is perfect” (Matthew 5:48).

What a hopeful promise for our teenagers, and for all of us to live by as we faithfully stand by each other in difficult moments.

A message of love

‘I do.’

A look ahead

Thank you for joining us. Please come back Monday, when staff writer Scott Peterson looks at the May 1 target date for U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan and asks: What can President Joe Biden do to avert catastrophe?