- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 10 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- No badges. No guns. Violence interrupters patrol Minneapolis streets.

- Vaccine mandates: Colleges juggle ethics and enrollment dilemmas

- Can Britain mine coal while it’s going green? It’s complicated.

- Why compassion is key to stopping procrastination

- How is a sonnet like the suburbs? Both are places of possibility.

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

This Ramadan, a call to embrace reason, dignity, and tolerance

April Austin

April Austin

As Muslims celebrate the start of Ramadan this week, they draw closer to their faith through prayers and fasting. But the holy month also means tighter enforcement of piety laws in some countries, with authorities doling out harsh punishments to people accused of a range of offenses, from blasphemy to failing to observe the fast.

Author Mustafa Akyol wants to convince his fellow Muslims that such punitive laws “grew out of historical interpretations and do not represent the unchangeable divine core of the faith.” In his new book, “Reopening Muslim Minds: A Return to Reason, Freedom, and Tolerance,” he makes the case that in Islamic history, the values of justice, mercy, and human dignity were emphasized alongside obedience to God’s commands.

During the Islamic Golden Age, from the eighth to the 14th centuries, Muslims were on the cutting edge of science, mathematics, and philosophy. “If there had been Nobel Prizes, they would have won all of them,” Mr. Akyol says in an interview. He wants to see a Muslim Enlightenment, similar to what occurred in 18th-century Europe, that would encourage discussions about questions of theology and ethics.

But “there are powerful orthodoxies” in the contemporary Muslim world that have become a rallying point for those who “would use coercion to advance and protect Islam,” he says. Hence laws that emphasize outward compliance over inner transformation – a phenomenon that also exists in fundamentalist branches of Christianity and Judaism.

Mr. Akyol wants to reintroduce the ideas of early Muslim philosophers who “believed that human dignity and reason were important in and of themselves.”

He’s under no illusion that change will happen quickly. But he is hopeful. “In parts of the Muslim world, you have young people who are fed up” with rigid laws meant to enforce piety. “They’re saying, ‘There must be a way out of this.’”

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

A deeper look

No badges. No guns. Violence interrupters patrol Minneapolis streets.

Is violence something that can be cured? A Minneapolis program sends out unarmed residents, rather than police, to de-escalate situations.

Six nights a week, groups of 20 unarmed residents – including former felons and gang members – “patrol” Minneapolis’ high-crime zones. These violence interrupters’ approach to deterring conflict relies on quick thinking, calm persuasion, and a credibility that derives, in part, from who they aren’t – law enforcement.

“Their job is not to punish people,” says Sasha Cotton, director of the Office of Violence Prevention. “It’s about saving them.”

The work has gained urgency as Minneapolis braces for the outcome of Derek Chauvin’s trial in the death of George Floyd. Tensions in the city climbed this week after a police officer in a suburb shot and killed Daunte Wright during a traffic stop Sunday, igniting clashes between protesters and officers. As the unrest continued Monday, Minnesota Gov. Tim Walz imposed an overnight curfew on much of the Twin Cities, and Minneapolis Mayor Jacob Frey declared a state of emergency.

Antonio Williams, who joins the group for its nightly rounds after pulling his daily shift in a packing warehouse, tolerates the hardships of long hours and variable weather for the safety of fellow residents.

“This is my neighborhood, my community,” he says, “and what we’re trying to be is a buffer between order and chaos.”

No badges. No guns. Violence interrupters patrol Minneapolis streets.

A group of 20 men and women huddled outside a convenience store as steam rose from their paper coffee cups and the evening temperature dipped toward freezing. They greeted the occasional customer as they stood watch over the parking lot and nearby area, seeking to avert potential bloodshed without the aid of badges and guns.

Known as violence interrupters, the team stops by the store six nights a week during a five-hour “patrol” of Lake Street, a busy commercial and cultural corridor in south Minneapolis. Their approach to deterring conflict relies on quick thinking, calm persuasion, and a credibility that derives, in part, from who they aren’t.

“If we looked and acted like cops, people would right away blow us off,” says Muhammad Abdul-Ahad, the team’s leader and a longtime street outreach worker. The differences extend to uniforms. He opened his jacket to reveal a bright orange T-shirt bearing an outline of the city’s skyline above the word “MinneapolUS,” a one-word synopsis of the team’s ethos.

“We can relate to people because we live here, too,” he says. “We listen to them, and from showing them that empathy, they’re willing to listen to us.”

Minneapolis has endured a spike in homicides, shootings, and other violent crimes since police killed George Floyd last May. The video of Officer Derek Chauvin kneeling on his neck for nine minutes set off weeks of protests and deepened distrust within communities of color of the mostly white police force.

The Office of Violence Prevention established the interrupters program under the MinneapolUS banner last fall as part of the city’s evolving efforts to reimagine public safety and reduce dependency on traditional policing.

Four teams of 20 to 30 members, whose ranks include former felons and gang members, walk the streets in high-crime zones. Unarmed and lacking arrest authority, they stay alert for disputes between residents – young men in particular – and attempt to intervene before verbal taunts give way to fists or firearms.

“Their job is not to punish people,” says Sasha Cotton, the office’s director since its inception in 2019. “It’s about saving them.”

The work has gained greater urgency as Minneapolis braces for the outcome of Mr. Chauvin’s trial on charges of second- and third-degree murder and manslaughter. Tensions in the city climbed this week after a white police officer in the adjoining suburb of Brooklyn Center shot and killed a Black man, Daunte Wright, during a traffic stop Sunday, igniting clashes between protesters and officers.

As the unrest continued Monday, Minnesota Gov. Tim Walz imposed an overnight curfew on much of the Twin Cities, and Minneapolis Mayor Jacob Frey declared a state of emergency. The officer, Kim Potter, and Brooklyn Center Police Chief Tim Gannon resigned Tuesday.

For the members of Mr. Abdul-Ahad’s team, most of whom hold day jobs, the patrols represent a chance to sow goodwill as their city struggles to recover from the upheaval over Mr. Floyd’s death. Antonio Williams, who joins the group for its nightly rounds after pulling his daily shift in a packing warehouse, regards the late hours and variable weather as hardships worth tolerating for the safety of fellow residents.

“This is my neighborhood, my community,” he says, “and what we’re trying to be is a buffer between order and chaos.”

Violence as public health crisis

Members of the Minneapolis City Council pledged to “end policing as we know it” last spring in the aftermath of officers killing Mr. Floyd. The council later cut $8 million from the police budget to boost spending on public safety alternatives, and funding for the Office of Violence Prevention almost tripled, from $2.5 million to $7.4 million.

The infusion of resources enabled the office to bolster existing initiatives to counter youth and gang violence and launch the interrupters program. The growing emphasis on prevention strategies has occurred as city officials reassess a police department whose officers are seven times more likely to use force against Black residents than against white residents.

“We often ask law enforcement agents to be everything,” Ms. Cotton says. The teams of interrupters, by defusing conflicts before they explode, could ease the burden on officers and, in turn, lower the incidence of police violence. “We’ve got to create a system that allows law enforcement to focus on things they’re really good at. They do de-escalation, but it may not be their strongest skill.”

The funding for her office amounts to less than 5% of the $170 million police budget. The interrupters earn $25 an hour, and the city has committed $2.5 million to the program, with plans to expand and refine its operations this year.

City Council Member Phillipe Cunningham, who prodded his colleagues to form the violence prevention office two years ago, advocated for the interrupters program as shootings and homicides rose across Minneapolis last summer. He describes the teams as essential to teaching residents to view violence as a public health crisis that requires preventive remedies.

“When we talk about safety, folks tend to think that adding more officers is the only way to solve the problem,” he says. “Violence is a disease that spreads through communities, and it can be cured. But to do that, we have to look at solutions other than policing.”

The city has worked with Cure Violence to develop its interrupters program. Dr. Gary Slutkin founded the Chicago-based organization as CeaseFire in 1995, and in assisting dozens of cities to form similar programs that have yielded encouraging results, he has preached the merits of preemptive action.

“What usually leads up to violence – somebody owes someone $10, somebody insults someone at a party – is retaliation,” he says. “That doesn’t lend itself to doing something afterward. You have to do something before.”

Dr. Slutkin, an epidemiologist by training, helped direct the medical response to AIDS and other global epidemics during his time with the World Health Organization in the 1980s and ’90s. The Cure Violence model applies lessons from his experience.

In the context of public safety, he explains, the interrupters serve as contact tracers. They draw on their past exposure to and understanding of violence – as perpetrator, victim, or witness – to detect conflict and coax people back from the brink.

“The interrupters have credibility and connections in the community. They can talk people out of what they’re thinking of doing and get them to cool down,” he says. “And they can do that because people respect them.”

“Change is possible”

Mr. Abdul-Ahad and his team shuffled in place to stay warm outside the Lake Street convenience store on a recent evening. They had walked several blocks west and returned, finding the sidewalks almost deserted. The cold spring weather, a parting shot from winter, had interrupted violence for the night.

The lull provided opportunity for Mr. Abdul-Ahad to recount a less sedate evening last fall. A man pulled into the shop’s parking lot and stepped from his car. He pointed a handgun at another man standing on the sidewalk and began yelling about a woman they both knew.

The team’s members swarmed into action. In line with their de-escalation training, they moved into the space between the two men. Half of them faced the gunman and urged him to consider the lasting costs if he squeezed the trigger. The other interrupters shepherded the second man around the corner and ordered him an Uber ride.

The gunman soon relented. The crisis receded. Nobody called the cops.

“You can’t tell people what to do if you’re not meeting them at the same level,” says Mr. Abdul-Ahad, whose time in prison on drug and money-laundering charges a decade ago informs his approach. He now runs an auto-parts delivery service, and his charisma and devotion to street outreach have earned him the nickname “Mobama,” a reference to the former president. “You got to respect people for them to respect you.”

The members of his hand-picked team have endured their share of adversity, including prison, homelessness, drug addiction, domestic abuse, and childhood trauma. The experiences animate their compassion for the people they encounter.

Charles Andrews ran away from his Minneapolis home as a teenager to escape physical abuse. He drifted between the streets and the houses of friends for the next two years, and he recognizes the insidious forces – poverty, drugs, gangs – that can lure a young person toward the abyss of violence.

“Change is possible. I know that because I lived it,” says Mr. Andrews, who works for a demolition company. He credits a friend’s mother for pointing him toward a new future more than two decades ago. “Sometimes people just need a chance to stop and think. That’s why we’re out here – to create that pause and plant that seed.”

A shift in thinking

An analysis in 2017 revealed that less than 10% of the Minneapolis police force lived in the city. None of the four former officers charged in Mr. Floyd’s death lived here at the time of their firing last May.

The members of Mr. Abdul-Ahad’s team take pride in their Minneapolis addresses, and their familiarity with the city breeds a familiarity with residents. They walk the beat in a manner once associated with cops, and passersby greet them with waves, elbow bumps, and car honks. The response contrasts with the frayed relations between police and communities of color.

“I see the interrupters out there in their orange shirts and I’m grateful,” says D.A. Bullock, an activist and filmmaker who lives on the city’s north side. “Cops are always showing up after a shooting. There needs to be stronger engagement with young people to head off shootings.”

The rise in violent crime has coincided with the departure of about one-fourth of the police force in the past year. In the aftermath of Mr. Floyd’s death, when protesters rallied against police brutality and rioters set fire to the 3rd Precinct station, some 200 of the department’s 850 officers retired, resigned, or took extended leaves.

The loss of personnel has contributed to the department’s homicide solve rate plunging below 50%. The wave of violence has magnified scrutiny of the interrupters program and other public safety initiatives, says James Densley, a professor of criminal justice at Metropolitan State University in St. Paul.

“There is real pressure for the city to not just get it right but get it right quickly, because if they don’t, people of color and communities of color will suffer the hardest consequences,” he says. As the city weighs multiple proposals to reform or replace the police department, he adds, residents inhabit an uneasy limbo.

“The problem is, until we have legitimately funded public safety programs, we have this void where you don’t have full-strength policing and you don’t have full-strength alternatives.”

A poll last summer found that three-fourths of residents support shifting a portion of police funding to anti-violence programs and social services. The same survey showed that a majority of residents oppose or remain uncertain about reducing the number of officers in the department. Mr. Densley suggests that their ambivalence arises from a misperception about the city’s options.

“It’s a false dichotomy to say that you have to defund the police to afford the community initiatives people are calling for,” he says. “You can have both well-funded public safety programs and police. What it requires is a shift in thinking about how to prevent violence.”

The CeaseFire program earned praise for reducing gun violence in Chicago after its launch a quarter century ago. But local and state officials slashed its funding in 2015 after police questioned the hiring of former gang members to curb crime and blamed the interrupters for inflaming community suspicion of officers.

The city’s homicide toll soared to 769 last year, its second-highest total in the past two decades, and the pace of killings has continued so far in 2021. Reform advocates fault local officials for failing to provide more funding for interrupters and other public safety initiatives amid the bloodshed.

“You have to have the same commitment to these programs as you’ve had to police,” Dr. Slutkin says. “That’s what will lead to change.”

A mother’s resolve

A light rail station on Lake Street marks the start of the route that Mr. Abdul-Ahad’s team patrols each night. One evening last month, as the interrupters neared the building, they noticed a man punching a woman.

A few of the men stepped between the couple. Yulonda Royster placed an arm around the sobbing woman and guided her away to talk in private.

The woman’s anguish and fear reminded Ms. Royster of her own while trapped in an abusive relationship several years ago. Memories surfaced of the struggle to exhale, to think, to imagine a way out.

“You’re wondering what you did to deserve this, and you feel like there’s nowhere to go,” says Ms. Royster, who grew up near the intersection where police killed Mr. Floyd. She consoled the woman before ordering an Uber to return her to the domestic violence shelter where she had stayed the past few weeks. “The hope is that maybe we can help break that cycle.”

Ms. Royster brings a mother’s resolve to her work as an interrupter. The oldest of her five children is in prison for his role in a gang-related shooting, and she wants to spare other young men his fate.

So six evenings a week she slips on her orange MinneapolUS shirt and heads to Lake Street. She joins the team to walk the beat as they seek to reclaim the city one block and one person at a time.

“It’s important for people just to see us, to know we’re out here,” she says. “Especially right now, when everybody’s on edge. We want them to know their community cares about them.”

Vaccine mandates: Colleges juggle ethics and enrollment dilemmas

A sense of safety is key for getting students back on campus. Colleges are juggling ethics and politics as they decide how far to go in encouraging COVID-19 vaccines.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

An increasing number of colleges – public and private, large and small – are mandating COVID-19 vaccinations for students and employees returning to campus this fall.

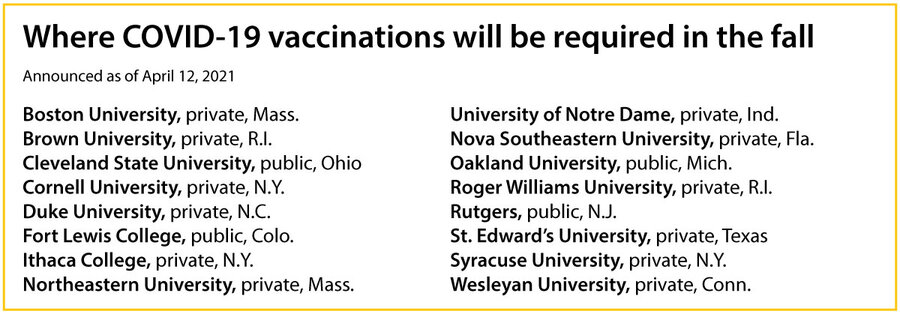

At least 16 schools had announced fall vaccination mandates as of April 12.

But as higher education leaders, hoping to reverse the pandemic dip in enrollment nationally, weigh the ethics of mandating the measure to further safe reopening, political and legal challenges may complicate these plans.

“I suspect that there will be these divisions along partisan lines – in the way that we have seen with mask mandates, with social distancing, when states decided to reopen – that will influence decisions by colleges and universities,” says Lynn Pasquerella, president of the Association of American Colleges and Universities.

All states have school vaccination requirements, and some include higher education. Though exemptions vary, all states must exempt people medically unfit to receive vaccinations, says James Hodge, health law professor at the Sandra Day O’Connor College of Law at Arizona State University. “Universities use vaccine mandates all the time. … The expectation is you fulfill those, or else you don’t get to show up and study, or matriculate.”

Nevertheless, colleges will face complications in considering the mandates – like employment law and equitable access, says Dr. Pasquerella.

Vaccine mandates: Colleges juggle ethics and enrollment dilemmas

Hoping to attract students back into the classroom for a more normal fall semester, colleges and universities are starting to require COVID-19 vaccinations for in-person attendance.

At least 16 U.S. colleges and universities – a mix of public and private, large and small – have announced the requirement for the fall, with more announcements expected. Others are incentivizing compliance by offering campus employees a cash bonus to do so or offering vaccinated students and staff the option of going maskless this spring.

But as college leaders weigh the ethics of mandating the measure to further safe reopening, political and legal challenges may complicate these plans.

“I suspect that there will be these divisions along partisan lines – in the way that we have seen with mask mandates, with social distancing, when states decided to reopen – that will influence decisions by colleges and universities,” says Lynn Pasquerella, president of the Association of American Colleges and Universities.

All states have school vaccination requirements, and some include higher education. Though exemptions vary, all states must exempt people medically unfit to receive vaccinations, says James Hodge, health law professor at the Sandra Day O’Connor College of Law at Arizona State University.

“Universities use vaccine mandates all the time,” says Professor Hodge. “The expectation is you fulfill those, or else you don’t get to show up and study, or matriculate.”

Some experts say the lack of full U.S. Food and Drug Administration approval of COVID-19 vaccines could invite legal challenges. All three vaccines available in the U.S., so far, have emergency use authorization (EUA), not full approval.

Nonetheless, says Sten Vermund, dean of Yale School of Public Health, “This particular set of vaccines for [the novel coronavirus is] remarkably safe and remarkably effective.” But, adds the epidemiologist, “How American universities are going to set policy is going to be a balance between their view of social obligation versus individual liberty.”

(On April 13, after Dr. Vermund's remarks to the Monitor, the federal government recommended pausing the use of the Johnson & Johnson vaccine “out of an abundance of caution” as it undergoes more review.)

Equal access implications

Colleges will face complications in considering the mandates – like employment law and equitable access, says Dr. Pasquerella.

For example, she notes, “If the most vulnerable students are having to worry about whether the person sitting next to them is a COVID carrier, they’re not going to have access to equal opportunity and learning.”

Cornell University student Bianca Garcia supports her school’s plan to require the vaccines for students, and trusts the private New York institution will respect medical and religious exemptions.

“I’m looking forward to just being able to expand my social circles and explore this place disease-free, guilt-free,” says the sophomore.

Some students oppose the measure.

“I am not anti-vax. I am extremely anti-mandate,” says Sara Razi, a junior at Rutgers, a public university in New Jersey among the first to announce a mandate for students in late March. Like the pandemic, the vaccine has “been politicized,” she adds.

In Florida, the private nonprofit Nova Southeastern University with over 20,000 students is requiring COVID-19 vaccinations for students and employees returning in person this fall, though a remote option will remain available.

“If we’re talking about protection, we want everyone to have as much protection as possible,” says Harry Moon, executive vice president and chief operating officer.

Political pushback?

The day after Nova Southeastern’s April 1 announcement, however, Republican Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis signed an executive order banning government entities from issuing and businesses from requiring “vaccine passports.”

“We respect the governor very much,” says Dr. Moon, whose school is reviewing the order. “We have a fair amount of time to develop the policies and procedures to accomplish the goals that we’re seeking.”

Other early signs of political reckoning are emerging.

Following a COVID-19 vaccine mandate for students and employees announced by a private Austin university March 29, Republican Gov. Greg Abbott of Texas signed an April 5 executive order barring government agencies – along with public and private entities receiving public funds – from creating COVID-19 requirements for services. St. Edward’s University has since stated that its policy squares with state law, because it allows “exemption pathways.”

A Democratic state lawmaker in Rhode Island introduced a bill in February that would make vaccination status a protected class shielded from discrimination. At least two private universities in the state have announced COVID-19 vaccine mandates this spring.

As access to vaccines expands – with all adults expected to be eligible by April 19 – several schools have turned their campuses into vaccination sites.

Some are incentivizing the shots, like Johnson County Community College in Kansas, which is offering $250 to employees who get vaccinated, the Shawnee Mission Post reports.

At public Dickinson State University in North Dakota, with under 1,500 students, fully vaccinated students and employees can opt out of a mask mandate this spring, which is set to expire in the fall. Individuals can receive buttons or wristbands that signal they’re allowed to go maskless.

“We really want to hope that we can incentivize the vaccine, while still allowing people to make individual decisions,” says Dickinson president Steve Easton. “We prefer that we do everything we can to fight this disease without mandated medical treatments.”

Can Britain mine coal while it’s going green? It’s complicated.

A special kind of coal still plays a big role in steelmaking. Does that justify a new mine, during an era of transition away from fossil fuels?

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Of all the fossil fuels, coal is known as the dirtiest, and Britain was a founding member of the Powering Past Coal Alliance, a body dedicated to eradicating its use in energy generation. Yet now England’s northwest coast is the proposed venue for something not seen in 30 years: a new British coal mine.

This is stirring up controversy – and a pending public inquiry by the national government – as Britain prepares to host a global conference on climate change action this fall.

Boosters of the mine say it would yield the so-called coking coal now relied on for making steel, not coal to be burned for electricity. An estimated 2,000 direct and indirect jobs are seen as a benefit by many businesses near to the proposed development, says Julian Whittle, business engagement manager at the Cumbria Chamber of Commerce.

But, he adds, in the wider region nearby, many businesses “in the hospitality and tourism sectors, in the Lake District for example ... would look askance at this, thinking it’s tarnishing our green and pleasant image.”

Can Britain mine coal while it’s going green? It’s complicated.

Along England’s northwest coast, the Haig coal mine for 70 years supplied the local economy around Whitehaven with jobs until it closed in the 1980s. Its muscular winding engine, which used to haul the coal and several thousand workers up from the depths, still towers over the site, a relic of this proud but also danger-filled past.

Now, many people in the region have a surprising hope: that the phrase “bygone era” will prove premature.

They see Whitehaven as a promising site for a new coal mine, even though the world is entering an era focused on how to steer toward zero carbon emissions.

The company West Cumbria Mining has been pitching its idea for several years now. But in recent weeks the proposal has escalated into a national controversy, as clean-economy advocates seek to quash the planned mine amid Britain’s preparations to host this year’s United Nations conference on global warming.

The underlying question is, can you be serious about responding to climate change and also approve a new coal mine?

“Unfortunately, when you mention the word ‘coal,’ people form an impression right away,” says Mike Starkie, mayor of Copeland, the Cumbrian district set to host the proposed mine, and an ardent supporter of the project. “But there are different kinds.”

Coal’s role in steelmaking

Beneath the seabed near Whitehaven lie deposits of the kind of high-quality coal that currently plays a vital role in most steelmaking. Advocates for the project say Britain currently imports this kind of metallurgical or “coking” coal from other continents, and that demand for steel will grow in part because of the need for structures like wind turbines for a greener future economy.

Foes of the project argue that none of this justifies an investment in a form of energy that should be phased out, and which will do relatively little for job creation in the Cumbria region.

“For a coal mine to be worth the investment, you’re talking about a long-term future,” says Bob Ward, policy director of the Centre for Climate Change Economics and Policy, a collaboration between the University of Leeds and the London School of Economics and Political Science. And although coking coal will still be relied on for some time to produce chemical reactions in steelmaking, he views its demise as all but inevitable.

“The pressure on the steel industry to [become greener] is so intense, that while we’re not there yet, everybody’s racing to get there,” Mr. Ward says.

Approving a coal mine “looks terrible”

Indeed, of all the fossil fuels, coal is regarded as the dirtiest, and Britain was one of the founding members of the Powering Past Coal Alliance, a body dedicated to eradicating its use in energy generation.

The British government announced in March that it was launching a public inquiry into the proposed mine that would be the country’s first new deep coal mine in more than three decades.

Days later, the government published a review of Britain’s role in the world, in which Prime Minister Boris Johnson stated that tackling climate change and biodiversity loss would be “the U.K.’s foremost international priority.”

This comes as Britain is just a few months away from the latest U.N. conference of parties on climate change, COP26, to be hosted in Glasgow, Scotland.

“If the U.K. wants to be seen as a climate champion,” says Andrew Grant, head of climate, energy, and industry research at Carbon Tracker, a London-based think tank, “for it to be sanctioning a coal mine in the year when it’s hosting COP looks terrible.”

The mine’s backers in Cumbria – who have received approval on three different occasions, only to have it rescinded each time so far – argue the situation is more complex.

In the realm of electric power, myriad forms of renewable energy are pushing coal-fueled power generation toward extinction. Yet in steel production, they say, the primary candidate to replace coking coal, a process that uses hydrogen, is still in its developmental stages.

A debate over jobs

The issue’s politics go beyond questions of clean energy. In Britain’s recent general election, the Conservatives boosted their majority in no small part by wresting a swath of northern constituencies from their main opposition, Labour. In an effort to retain this newfound support, the government has been promoting its “leveling-up” agenda, lavishing more attention and resources on these parts of the country that have long lagged behind London and areas of southern England.

Many Conservative parliamentary representatives of northern seats are supporting the mine, pointing to the 500 jobs it is slated to create directly, plus more than 1,500 jobs its developers predict will be created through the local supply chain.

Mayor Starkie, also a Conservative, cites such numbers as evidence that the project will “really help us drive the local economy forward.” He says that every member of the Copeland borough council, whether Labour or Conservative, supports the mine.

“When people look at Cumbria as a county,” says Karen Mitchell, CEO of Cumbria Action for Sustainability (CAFS), “they think of the Lake District national park, a very beautiful area, but they don’t realize we have pockets of very serious deprivation.”

“I really feel for the people in West Cumbria because they just want jobs, and I understand that,” continues Ms. Mitchell, “and the councils are driven by the same.”

But with concerns over the sustainability of the jobs that would come with the mine, as demand for its wares diminishes in the expected transition to “green steel,” some wonder whether it would make more sense to direct resources into supporting green jobs. A recent report commissioned by CAFS suggests that Cumbria has the potential to create 9,000 green jobs over the next 15 years.

“We do have huge potential for green energy,” says Julian Whittle, business engagement manager at the Cumbria Chamber of Commerce. And while businesses in towns near to the proposed development, such as Whitehaven and Workington, are “certainly positive” about the mine, Mr. Whittle says the picture is a little different further afield in Cumbria.

“The alternative view, which a lot of businesses outside of West Cumbria itself may hold, particularly those in the hospitality and tourism sectors, in the Lake District for example,” says Mr. Whittle, “is that they would look askance at this, thinking it’s tarnishing our green and pleasant image.”

As debate over the mine enters what may be a pivotal phase, some supporters of the mine put one other argument forward: that the Cumbrian site could be a test bed of how to mine coking coal sustainably, perhaps by linking its use to the implementation of carbon capture and storage techniques in an effort to make steelmaking emission-free.

Yet in the end, as the U.N. conference in November comes increasingly into view, the fact that the Cumbrian mine would be producing coal for steelmaking, rather than for power generation, may prove too much of a nuance to save it.

Listen

Why compassion is key to stopping procrastination

We all procrastinate sometimes. Compassion – for others and ourselves – can help us to stop making choices in the present that hurt our future selves.

One of the most amazing things about the human mind is its ability to imagine events that haven’t happened yet. To make a decision about something new – trying a new dish, picking a show to watch, and choosing a career – you have to mentally construct the experience and then predict how pleasant or unpleasant it will be.

But this simulation, say psychologists, is often distorted. Our predictions tend to exaggerate how happy or sad we’ll feel, and for how long.

“No doubt good things make us happy and bad things make us sad,” says Tim Wilson, a social psychologist at the University of Virginia. “But as a rule, not as long as we think they will.”

In the final episode of the Monitor’s six-part series “It’s About Time,” hosts Rebecca Asoulin and Eoin O’Carroll explore how thinking about our future selves can help us make better decisions in the present.

“We are always making trade-offs about things happening now versus later,” says Dorsa Amir, an evolutionary anthropologist at Boston College.

One of the most common ways that our present selves trip up our future selves is by procrastinating. But there are many ways for us to overcome the tendency to put things off, says Fuschia Sirois, a psychologist at the University of Sheffield in England. Among them: compassion. So the next time you notice yourself about to procrastinate, remind yourself that it’s OK to struggle. We’re not perfect. But we’re good enough.

This story was designed to be heard. We strongly encourage you to experience it with your ears (audio player below), but we understand that is not an option for everybody. A transcript is available here.

It’s About Time: How to Be Nicer to Future You

Books

How is a sonnet like the suburbs? Both are places of possibility.

To Craig Morgan Teicher, “poetry is a vast conversation spanning thousands of years.” For National Poetry Month, the poet shares how that poetic dialogue fits into his own life – and vice versa.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By Elizabeth Lund Correspondent

Craig Morgan Teicher knows a bit about finding beauty in the mundane. The poet and critic hopes his latest collection, “Welcome to Sonnetville, New Jersey,” will encourage readers to do the same.

“I think the experiment for me in the poems was to see if the drama of a ‘boring’ life can be brought forward. That if I could narrow the frame enough, that something as simple as staring at a bush could become a high-stakes event,” says Teicher.

Many of the sonnets in the book were written after he and his wife moved with their two children in 2015 from the borough of Brooklyn in New York to a suburb in New Jersey.

“The sonnet has these little formal checkpoints that you have to hit, the rhyme scheme and the rhythm,” he says. “I can’t help but think that that’s a little bit like what moving a family to a suburb is like. In some ways, it’s a very predictable existence, and yet you’re trying to show your children the fullness and unbridled possibility of life. Trying to do it in a way that’s safe and where they can explore without being afraid.”

How is a sonnet like the suburbs? Both are places of possibility.

Like millions of Americans, poet and critic Craig Morgan Teicher spends much of each day balancing the demands of family life and working in his home office. Teicher, who has published three previous books of poems as well as “We Begin in Gladness: How Poets Progress,” an acclaimed collection of essays, spoke recently about his new collection, “Welcome to Sonnetville, New Jersey,” and about trends in contemporary poetry.

Many of the poems in “Welcome to Sonnetville” were written after he and his wife, poet Brenda Shaughnessy, moved with their two children in 2015 from the borough of Brooklyn in New York to a suburb in New Jersey to accommodate the needs of their son, who uses a wheelchair.

While Teicher’s perspective is dark at times, the writing, which ranges from lovely to discomforting, highlights the rhythms in his family’s life and the “preciousness of tedious moments” as the adults reflect on their own suburban upbringing and the challenges and opportunities their children will face.

“I think the experiment for me in the poems was to see if the drama of a ‘boring’ life can be brought forward. That if I could narrow the frame enough, that something as simple as staring at a bush could become a high-stakes event,” says Mr. Teicher, who wrote some of the poems last year.

What surprises him now, he notes, “is that this book is really huddled around a very small cast of characters, just my family, and when I was working on it, I was very much thinking about what it was like to bring my family to this little house in this town in New Jersey. I had no idea that it was also going to be a portrait of a family in isolation during a pandemic.”

Teicher, whose second collection, “To Keep Love Blurry,” featured sonnets, had begun writing in that form again shortly after the family’s move to New Jersey.

“The sonnet has these little formal checkpoints that you have to hit, the rhyme scheme and the rhythm,” he says. “I can’t help but think that that’s a little bit like what moving a family to a suburb is like. In some ways, it’s a very predictable existence, and yet you’re trying to show your children the fullness and unbridled possibility of life. Trying to do it in a way that’s safe and where they can explore without being afraid.”

Over the course of several months, Teicher wrote 100 sonnets; roughly 20 are included in the new book.

“It’s sort of surprising to meet that guy from all that time ago,” he says.

One way poets experience their own books is by giving readings, going to other cities, and meeting people who’ve read the book. As the pandemic continues, in-person events are not possible. Teicher will give several Zoom readings instead.

Yet while poets may feel constricted in some ways, poetry continues to flourish, says Teicher, who teaches at Bennington College and New York University and is the digital director for The Paris Review.

“A poem is little and you read it and then you get to the end then and you reread it,” he says. “A poem offers a lot of restarts and the chance to enter a new consciousness in this very portable format. In the last five years, the internet has brought poetry to all kinds of people who never would have had it and has brought all kinds of poetry to people who would never have read it.”

Millennials and younger Americans have fueled that growth because they share links to websites rather than just reading books.

Amanda Gorman’s electrifying reading at President Joe Biden’s inauguration also excited people about poetry. “It was amazing after the inauguration to watch the culture at large spend a week talking about a poet,” he says.

“Gorman was the hottest cultural figure ... something that had never happened that way before, but it was possible because there was a robust culture of sharing poetry online and young people have taken control of how they consume literature.”

Teenagers today are often writing at an extremely high level, explains Teicher, who began writing at the age of 15, after the death of his mother, and with the encouragement of an English teacher.

Those experiences made it clear to him that he loved poetry more than anything. “Poetry is a vast conversation spanning thousands of years,” he says. “It’s a bunch of people talking back and forth. That’s really comforting and really exciting.”

Drop Off

Simone’s kindergarten is at the top of our street.

This morning, holding hands, we eagerly trudge

uphill. She waits in her class line while I meet

the other parents. My work won’t wait, but I’ve no grudge

against these fifteen sociable minutes. After checking phones,

we introduce ourselves, wearing our kids like name tags –

Hello I’m Alice’s; Hello I’m Simone’s –

reborn as the ones who packed their lunch bags,

hurried them – socks, now! Shoes! – into neon clothes,

stuffed pancakes and yogurt into their mouths,

and brought them to this sea-edge, where, in droves,

they embark upon the slow journey toward themselves.

It’s just like my old school – here I am across that sea,

back where I started – but I’m my mom; Simone is me.

– Craig Morgan Teicher

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Biden’s first steps on Central American migration

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

Nearly three months into his presidency, Joe Biden has taken the first concrete step to address the root causes of mass migration from Central America. His envoys secured agreements with Mexico, Honduras, and Guatemala to tighten their borders. The main goal: to prevent criminal traffickers from aiding people in making the dangerous journey to the United States.

The deals confirm the heart of President Biden’s plan for the region: strengthening the rule of law in order to tackle corruption, especially the kind between crime cartels and government officials.

“Corruption is something that affects conditions in Central America in an important way because the perception of impunity that people in powerful positions have when they commit acts of corruption has an impact: It discourages the population and contributes to the feeling that they have no future in their countries,” explains Ricardo Zúñiga, the State Department’s envoy for the Northern Triangle countries.

The universal idea of equal standing before the law, which is rooted in the dignity of each individual and the power of conscience, can take root in Central America. While more troops at the border is a first step, further measures will require addressing why people in the region want to seek a new life in the U.S.

Biden’s first steps on Central American migration

Nearly three months into his presidency, Joe Biden has taken the first concrete step to address the root causes of mass migration from Central America. His envoys secured agreements with Mexico, Honduras, and Guatemala to tighten their borders. The main goal: to prevent criminal traffickers from aiding people in making the dangerous journey to the United States.

These deals come just in time. The number of people apprehended at the U.S. southern border jumped 71% between February and March with those three countries accounting for the highest number of migrants. Border agents also apprehended a record number of unaccompanied minors.

The agreements confirm the heart of President Biden’s plan for the region: strengthening the rule of law in order to tackle corruption, especially the kind between crime cartels and government officials.

“Corruption is something that affects conditions in Central America in an important way because the perception of impunity that people in powerful positions have when they commit acts of corruption has an impact: It discourages the population and contributes to the feeling that they have no future in their countries,” explains Ricardo Zúñiga, the State Department’s envoy for the Northern Triangle countries of El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras.

In a global survey last year that measured rule of law in 113 countries, those three countries ranked among the lowest, not only in the world but also in Latin America. The rankings, done by the World Justice Project, a nonprofit group backed by the American Bar Association, showed little or no progress for Central America despite millions of dollars spent by the U.S. in the region since 2014.

The survey did note one success story. In Honduras, a civil society group, the Association for a More Just Society, uncovered serious issues with overpriced services and supplies to fight the pandemic last year. The private audit caused a senior official to resign.

As a sign of the Biden administration’s hope of channeling more money directly to corruption fighters in these countries, Mr. Zúñiga said the U.S. will donate $2 million to the International Commission against Impunity in El Salvador. He said the U.S. goal is to help Central America create “safe, prosperous, and democratic societies, where the citizens of the region can build their own lives with dignity.” Only then might irregular migration decline for the long term.

The universal idea of equal standing before the law, which is rooted in the dignity of each individual and the power of conscience, can take root in Central America. The U.S. is only one player, although a big one in supporting local civil society groups. Rule of law is not the domain of only politicians, lawyers, and judges. “Everyday issues of safety, rights, justice, and governance affect us all; everyone is a stakeholder in the rule of law,” states the World Justice Project.

While more troops at the border is a first step, further measures will require addressing why people in the region want to seek a new life in the U.S. One reason is their desire for a rule-based society.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Prayer for humility

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 1 Min. )

-

By Elizabeth Mata

Opening our hearts to God, we experience more of what it means to reflect “Spirit’s pure goodness / like a ray of the sun’s shine,” as this poem describes it.

Prayer for humility

Heart open, I reach for

humility like an artist, swept

clean of human push, poised

to catch and take in the next

perfect brushstroke or word

or chord that comes.Our God, Soul of us all, lift me

to a higher humility where we

– Your children – take on Your

cascade of joy and serenity,

glorifying You; living our

spiritual nature, allied to Yours

– reflecting Spirit’s pure goodness

like a ray of the sun’s shine.This strong, sweet humility

becomes a refuge of truth

where brazen assertions of

a selfhood apart from God

are shut out – as if darkness

could really enter where

light floods in.

A message of love

A gesture of kindness

A look ahead

Thank you for joining us today. Come back tomorrow. We’ll be exploring corporations’ increased willingness to go chest-to-chest with Republican leadership over questions of rights and justice.