- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 8 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Justice watch: Bringing an end to the blue bystander

In 2006, when Buffalo Police Officer Cariol Horne saw a white officer using a chokehold on a handcuffed Black suspect, she intervened. But that act ended her 19-year career. She was fired a year shy of getting her full pension.

Ms. Horne’s actions stand in stark contrast to the passivity of three Minneapolis police officers, who watched as then-Officer Derek Chauvin knelt on the neck of George Floyd last May. At Mr. Chauvin’s ongoing trial, two bystanders testified they pleaded with the officers to help Mr. Floyd. All three officers face charges of aiding and abetting in the killing of Mr. Floyd.

In New York on Tuesday, after a 14-year legal battle, a judge annulled Ms. Horne’s dismissal and ruled she is entitled to her full pension, benefits, and back pay. In the 11-page ruling, New York Supreme Court Judge Dennis Ward wrote, “The time is always right to do right,” paraphrasing the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

The ruling is an overdue vindication for Ms. Horne. But the more enduring victory came last October when the mayor of Buffalo signed Cariol’s Law, requiring officers to step in when one of their own uses excessive force. Since Mr. Floyd's death, similar “duty to intervene” laws have been passed in Colorado, Connecticut, Massachusetts, Nevada, and New Jersey.

The Buffalo case suggests law enforcement norms are finally catching up to Ms. Horne’s moral standards, and that justice sometimes comes slowly. But with persistence, it comes.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

A deeper look

How voting bills put GOP and corporations on opposing sides

Corporate stands on cultural issues, such as LGBTQ rights, have grown in recent years. But we wondered why CEOs now see the integrity of voting rights as a core value to be protected.

Just a year ago, the right to vote was not a highly contentious, polarized political issue. Then came an extraordinary period in American history: A president, without hard evidence, claimed an election was “rigged.” His supporters, egged on by his words, rose in insurrection and bashed their way into the U.S. Capitol.

Now Republican lawmakers in many states are pushing “voting integrity” bills that they say are necessary to restore confidence in election machinery. Yet the courts, election officials, some Trump appointees, and even Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell of Kentucky say that much evidence shows the 2020 elections were clean and fair. Democrats say that “election integrity” really means making it more difficult for Democratic constituencies, including Black voters, to cast ballots.

Ballot access controversy is thus exploding in many states – and corporations are finding it is an issue that is hard for them to ignore. After Georgia passed a voting bill, Major League Baseball yanked the All-Star Game out of Atlanta, infuriating the Georgia GOP and launching calls for a retaliatory baseball boycott.

In short, no longer do most CEOs heed Michael Jordan’s famous admonition that “Republicans wear sneakers, too.”

Business and politics have always mixed, of course. So have sports and boycotts.

How voting bills put GOP and corporations on opposing sides

When Ronnie Chatterji dug deep into motivations for corporate CEOs to take public stands on hot-button social and cultural issues, he tracked levels of public polling support for issues from marijuana legalization to pay equality.

In hindsight, he admits he made a glaring omission from that list: voting rights.

“Voting rights weren’t even on the chart in 2018,” says Professor Chatterji, who studies corporate activism at Duke University’s Fuqua School of Business in Durham, North Carolina. “Now they are so salient that CEOs must respond.”

He can perhaps be forgiven for the oversight.

Just a year ago, the right to vote was not a highly contentious, polarized political issue. Then came an extraordinary period in American history: A president, without hard evidence, claimed an election was “rigged.” His supporters, egged on by his words, rose in insurrection and bashed their way into the U.S. Capitol.

Now Republican lawmakers in many states are pushing “voting integrity” bills that they say are necessary to restore confidence in election machinery. Yet the courts, election officials, some Trump appointees, and even Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell of Kentucky say that much evidence shows the 2020 elections were clean and fair. Democrats – and some in the GOP – say that “election integrity” really means making it more difficult for Democratic constituencies, including Black voters and other minorities, to cast ballots.

Ballot access controversy is thus exploding in many states – and corporations are finding it is an issue that is hard for them to ignore. After Georgia passed a voting bill, Major League Baseball yanked the All-Star Game out of Atlanta, infuriating the Georgia GOP and launching calls for a retaliatory baseball boycott.

Coca-Cola and Delta, big companies located in the state, publicly condemned the new legislation. Hundreds of firms, including Amazon and Google, signed onto a general statement released Wednesday opposing “discriminatory legislation” that makes it harder to vote.

Sensing that bottom lines are likely safe, and keen to express diversity values to recruits, employees, and customers, corporations are increasingly willing to go chest-to-chest with Republican leadership over questions of rights and justice. Here in Atlanta, it reflects a broader regional reckoning around voting rights and whether political uproar and tweaking of democratic norms will cool corporate enthusiasm for the New South.

“This is a tough call for corporate leaders, because, in fact, they can’t win,” says Richie Zweigenhaft, a professor emeritus of psychology at Guilford College in Greensboro, North Carolina, who studies the impacts of sports-based activism on society. “CEOs know that if you’ve got a country split 51-49 in terms of politics, they’re going to offend some customers if they do something or if they don’t do anything.”

Business and politics have always mixed, of course. Corporate lobbying has been a major influence in American politics since at least the Gilded Age of the late 1800s. Corporate-linked campaign contributions have filled candidate and party treasuries for decades, primarily for lower tax, less regulation-oriented Republicans.

But in recent years some state legislation has pulled corporations into taking stands that oppose conservative social issues. A 2015 Indiana law that allowed businesses to deny service to same-sex couples; North Carolina’s 2016 “bathroom bill,” a now-sunsetted law that required transgender people to use public facilities that correspond to their sex assigned at birth; and a 2018 Georgia law banning abortion after doctors can detect a so-called fetal heartbeat are among the items that have sparked corporations and sports leagues to react.

Corporate boycotts of particular states are effective in that they do send messages to other states that controversial laws do have a monetary cost, say experts. In short, no longer do all CEOs heed basketball star Michael Jordan’s famous admonition to boycott-seeking activists that “Republicans wear sneakers, too.”

As corporate activism has stepped up, it has forced Republicans in some ways to choose between a conservative voter base that is angry about an American culture it believes increasingly leans left, and the need to ally with customers and employees who want to defend against what they see as attacks on core American values, like voting.

Call it corporate activism 2.0, says Professor Chatterji. That’s perhaps the dynamic sweeping through boardrooms at the moment and pushing business executives to talk about changes in electoral procedures.

“I do not know if CEOs would be talking about these issues if they weren’t elevated from ... [a national] conversation about race and discussions around the 2020 election, including the false narrative that it was stolen,” says Professor Chatterji. “That’s how you get the connection between these laws in Georgia and Texas and the stolen election narrative and race.”

From the corporate point of view there is much to be gained from speaking out clearly on cultural values. The risks of consumers angered by their stances organizing a costly boycott of their products is fairly low. The benefits are more tangible, especially when it comes to recruiting younger workers, says Professor Chatterji, co-author of a 2018 Harvard Business Review article on the subject. About half of all millennials say they are willing to make consumer and employment choices based on corporate values, he says.

In general, the social and cultural stances of public corporations have leaned left. They have supported the progressive side of LGBTQ rights, immigration, and racial justice. Conservative activism chiefly comes from privately held, family-owned corporations, such as Chick-fil-A, whose founder S. Truett Cathy was a devout Southern Baptist.

Georgia as test case

Still, there are risks for CEOs.

“There is ... a risk that you’re seeing in Georgia, which is backlash from legislators who feel companies are not occupying their correct role in civic discourse, so they’re [threatening to revoke] tax incentives or increasing the heat of rhetoric,” says Professor Chatterji.

In Georgia some Republican lawmakers feel they were misled. The GOP met with corporate leaders when they were crafting the bill, and didn’t hear strong objections. Some of the most controversial parts of the original legislation were discarded as too incendiary, including a proposed ban on Sunday voting, which would have disproportionately affected Black church “Souls to the Polls” events.

It was only after the bill’s passage that Georgia-headquartered firms like Delta and Coca-Cola made stronger statements. Then MLB moved quickly to pull the All-Star Game plug. Actor Will Smith has also said he will pull his production company out of Georgia.

“Republican leadership may well have thought that they had watered down the bill sufficiently and ... that they wouldn’t get blowback from business,” says veteran Georgia watcher Charles Bullock, a professor emeritus at the University of Georgia in Athens.

But the new law still contained provisions that Democrats say are directly aimed at suppressing the turnout of Black voters, such as a ban on giving refreshments to voters waiting in long lines, which are prevalent in many lower-income communities.

“It was a bad move strategically for Republicans to put in criminalizing water and snacks. ... It just comes off as mean-spirited,” says Professor Bullock.

Meanwhile, Georgia Gov. Brian Kemp, a Republican, has criticized “woke” corporations and the media for labeling the new law as racist. He says that some provisions actually expand voting rights, and that the new law makes it “hard to cheat” in Georgia elections. Audits run after the 2020 Georgia vote detected no widespread cheating.

Former President Donald Trump and Minority Leader McConnell have both issued sharply worded statements telling corporations, in essence, to butt out of the controversy. In Texas, GOP Gov. Greg Abbott backed out of throwing the first pitch at the Texas Rangers home opener, in protest of MLB’s All-Star Game switch.

These moves reflect the reality that polls show Republican voters generally believe former President Trump’s false statements about fraud in the 2020 election. GOP trust in elections plummeted.

“I think the Republicans – with both legislation and political messaging – have created a real different perspective on voting, so it’s become a political issue in a different way than it used to be,” says Professor Zweigenhaft, at Guilford College.

Jim Crow’s legacy

There’s a good reason Atlanta is at the center of this storm. It embodies the “New South” ideal of a place where corporations partnered with political leaders to build a new Southern economy. An implicit part of this deal was that politicians would reject the state’s racist legacy. Beginning in the 1960s, one Atlanta slogan was that it was “the city too busy to hate.”

The success of this business/political partnership helped power the South’s revival from its long post-Reconstruction economic slide, leaving Georgia as a relatively diverse and vibrant Southern state, with Atlanta as its flag-waving capital.

This legacy is a reason why even some Democrats in Georgia bristled when President Joe Biden called the new law “Jim Crow in the 21st century.” The real “Jim Crow,” the system of laws and informal rules backed by violence that separated the races after Reconstruction, was much, much worse, they say.

“Saying that this is racism, it’s turning back the clock to Reconstruction; if you look at the facts you can’t sustain that. But it plays well,” says Dr. Bullock at UGA. “Democrats are beating their drum because it works. But Republicans are doing the same thing.”

How fallout from the voting bill affects Georgia in the future will have an important effect on the South and national politics as a whole. The state narrowly went to Joe Biden in 2020, then elected two Democratic senators in a January 2021 runoff clouded by Mr. Trump’s continued false statements about fraud.

Is Georgia now a purple state? Or is it still a red state where Democrats triumphed due to a confluence of unusual circumstances? The answer could influence the outcome of the 2022 midterms and determine the 2024 presidential election.

The Georgia GOP did well in state races in 2020 and is poised to turn the state back into solid Republican territory, says Jay Williams, a Republican strategist in Alpharetta. The new election law will be part of that recovery, he says.

“It feels like a tipping point where you have to stop indicting white people for all the problems in the world,” says Mr. Williams. “You can’t say that because the governor is white he is passing a law that’s Jim Crow or racist. People just don’t want to listen to it anymore.”

Others have a different, perhaps nuanced, view.

Baseball diamonds in history have been places where players have had to field both ground balls and racism. The Atlanta Braves great Hank Aaron, who died in January, was known for the hitting prowess that made him baseball’s all-time home-run king, and his unrelenting work on behalf of civil rights.

Perhaps that is why the moving of the Atlanta All-Star Game to Colorado seemed to strike a particularly sensitive place in Georgia. Governor Kemp called it “an attack on our state.”

“What happens in sports has a lot of resonance,” says Bruce Adelson, author of “Brushing Back Jim Crow: The Integration of Minor League Baseball in the American South.”

That means the empty Atlanta stadium at baseball’s annual All-Star break in midsummer may stand as a powerful symbol.

“These players who broke the color line had a real sense of what was happening around them,” says Mr. Adelson of the men he interviewed for his book. “They told me, ‘We understood the times and we knew what our role was in moving forward.’

“I think the same would hold true now,” he says.

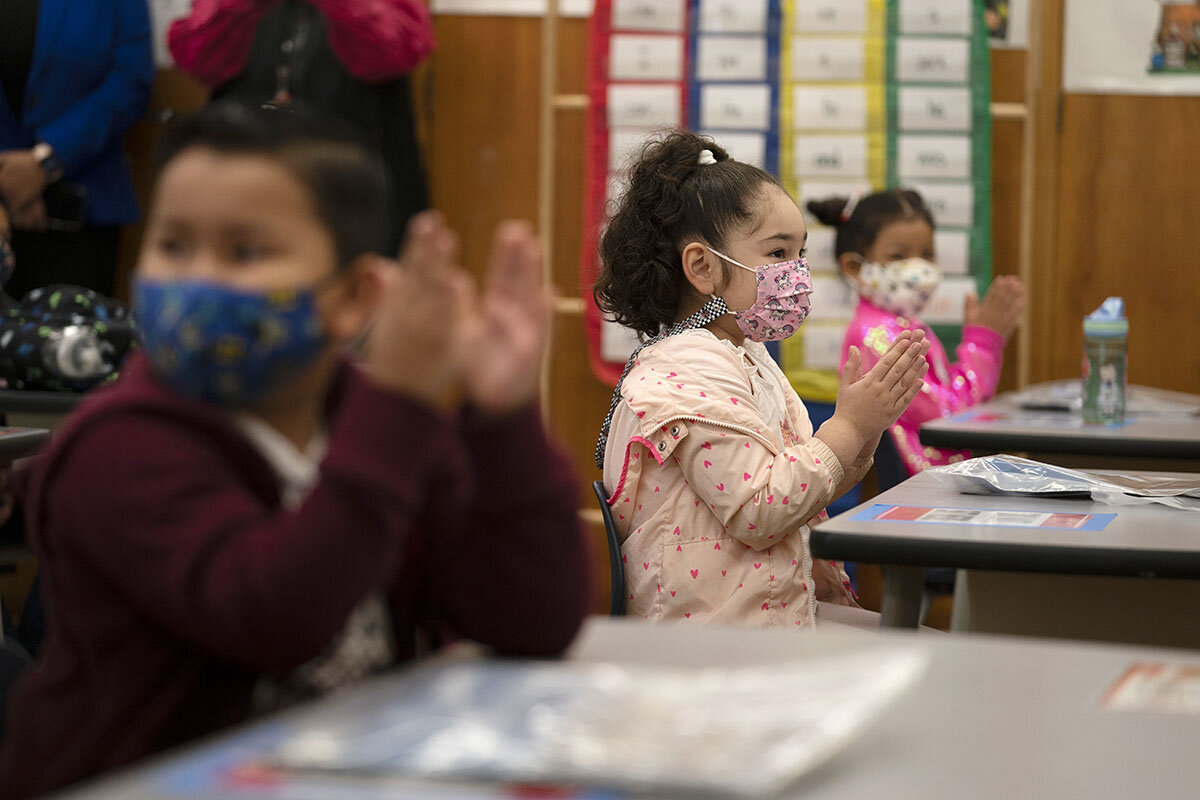

Pandemic learning gains: Resilience. Responsibility. Lunch.

Yes, some U.S. students, in some skills, have fallen behind this year. But we spoke to parents and teachers who say other skills and qualities have been developed and strengthened this year.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

As deputy chief of academics at Tulsa Public Schools in Oklahoma, Danielle Neves has seen the challenges of distance learning firsthand. And while there are plenty of concerns over academic skills, “I think our students have gained a lot of other things,” she says. “They’ve learned a different kind of resilience in this year.”

To illustrate, Ms. Neves points to examples of student growth in independence and technology skills. She’s also seen more social engagement from students over the country’s reckoning with racism.

Parents are seeing gains as well. Outside Atlanta, Alisha Thomas Morgan says her eighth grade daughter’s confidence and organizational skills have grown. And she’s hearing the same from others in her network. “Education in the pandemic has helped our children develop as good humans and become more responsible young people,” Ms. Morgan says.

That doesn’t mean there’s not some ground to make up. Initial research indicates that, academically, students are behind where they would usually be at this point in the year. Even so, experts are recommending an upbeat approach to closing the gap.

As Ms. Neves puts it, “We made a conscious effort to focus on ‘unfinished learning’ rather than ‘learning loss.’”

Pandemic learning gains: Resilience. Responsibility. Lunch.

Lakisha Young, a mother and community activist in Oakland, California, is determined to prove that children in her city don't have to be permanently harmed by pandemic disruptions to their learning.

She and colleagues at Oakland REACH, a parent group advocating for better education for Black and Latino children, formed a Virtual Family Hub last June that provides one-on-one tutoring, small-group instruction, and classes like martial arts, creative writing, and cooking. Children who participated saw measurable learning gains: Sixty percent of students in the hub’s literacy program rose two or more reading levels (different from grade levels) by the end of the summer.

Now Oakland REACH is partnering with the Oakland Unified School District to offer hub programming after school, and more than 400 students are signed up. The district recently announced plans to expand its partnership to up to 1,000 students by this summer.

“We see this as an opportunity not just to mitigate learning loss, but to take our kids further and beyond,” says Ms. Young.

Whether in reading or cooking, many students are making progress despite the pandemic. Recognizing this, some parents and teachers are trying to broaden the discussion around learning loss to include recognition of what students are learning – such as problem-solving and resilience, as well as literacy and math through programs like the hub. By focusing on students’ strengths and what they’ve learned inside and outside the classroom, some believe it will be easier to address gaps in their education.

“A different kind of resilience”

“I think a lot of the narrative about learning loss tends to be narrowly focused on academic or cognitive skills. What are the math units we didn’t get to? What depth of knowledge around social studies topics have we missed?” says Danielle Neves, deputy chief of academics at Tulsa Public Schools in Oklahoma, where 81% of students are economically disadvantaged. “I think our students have gained a lot of other things. Children are incredibly resilient human beings, and I think they’ve learned a different kind of resilience in this year.”

Measuring exactly what children have or haven’t learned over the past year isn’t easy. Initial research suggests many students are behind on core academic skills, particularly in math at all grade levels and reading in the earliest grades. Students who attend schools serving primarily Black or Latino students or those located in lower-income ZIP codes are falling furthest behind on grade-level academic standards.

At the same time, some educators and parents, from across the spectrum of income levels and races, believe the pandemic has strengthened students’ soft skills, which they say are also crucial for future success.

“We believe our task is to prepare students for the college or career that they choose, and that’s made up of cognitive skills and the critical thinking skills of communication, collaboration, problem-solving,” says Ms. Neves. “They are woven together. A student doesn’t become college- and career-ready simply because they read the most books or solved the most problems.”

Ms. Neves points to examples of student growth in independence and technology skills. She’s proud when she overhears her child’s classmates problem-solve by giving each other tips on fixing tech issues with Zoom. She’s also seen more social engagement from students over the country’s reckoning with racism.

In Tulsa and districts around the country, educators plan to build upon the positive skills that students have developed this year, while adding extra mental health and social and emotional support for students struggling with trauma or anxiety. In addition, academic aid will come in a variety of forms, like free summer school or small-group instruction.

Soft skills and future planning

Some parents note that their children’s response to remote learning has varied widely by age, with most reporting that older students have fared better than younger ones.

Victoria Bradley, a high school senior in Detroit, traded public school for home schooling this year and keeps herself on schedule with her curriculum. “Being organized and staying on track, that’s the part I learned and took value in,” she says. She completed a variety of courses through the online platform Outschool that helped her decide she wants to pursue forensic psychology for a career.

Crystal Bryce, associate director of research at the Center for the Advanced Study and Practice of Hope at Arizona State University, found a similar forward-looking focus in her study of 800 middle and high school students at a rural school district in Arizona. The preliminary results show that many students thought the pandemic gave them time to prepare and plan for their future.

“It might be contrary to what we might think, but it’s so great to see those responses because it shows that, even when things are hard, we can still have hope, and that’s something that can be sustained,” Dr. Bryce says.

Others have seen more immediate, concrete gains among students. Alisha Thomas Morgan, a parent and educational consultant outside Atlanta, says her eighth grade daughter’s confidence and organizational skills have grown. And she’s not alone in that. As Ms. Morgan talks with others in her network, she’s “blown away by the soft skills that have developed” among their children, like proactively emailing teachers or remembering to make their own lunches.

“Education in the pandemic has helped our children develop as good humans and become more responsible young people,” she says. “I think it’s equally important, as we make sure students are developing academically, that we also measure and value the personal development that they’ve experienced.”

Amanda Miller from Wallingford, Pennsylvania, says her high school junior flourished, enrolling in more honors classes than ever before and thriving with the independence of remote learning. But her younger son struggled without the structure of his regular school routine and entered therapy for anxiety. He’s happier now that his fourth grade class has resumed in-person learning.

Aaron Chuquimarca, a sixth grade student from Lowell, Massachusetts, falls somewhere in the middle. Still learning remotely, he’s excited about science class, where he’s studying chromosomes, and he’s had more time to do his chores. But he says he also gets “really distracted” at home.

“Unfinished learning”

Given a wide range of responses to learning during the pandemic, some school leaders encourage staff and students to approach upcoming teaching and learning with a growth mindset, made popular by Professor Carol Dweck at Stanford University, whose research finds that students achieve more when they believe intelligence isn’t fixed, but can grow.

“We made a conscious effort to focus on ‘unfinished learning’ rather than ‘learning loss,’ says Ms. Neves in Tulsa. “In a lot of ways, they can be similar in meaning ... but we wanted to make a choice to remove the onus of that from the students.”

Dr. Bryce, from Arizona State, underscores the importance of a positive outlook. “Research has shown that high hope is good for everything, but especially it helps with academics. Students with high hope are more engaged in school.”

Ms. Young, the community organizer in Oakland, is hopeful about the strong academic results of the parent-founded learning hub and its expanding partnership with the school district.

“If kids are actually doing better in subjects that they’ve struggled in, that goes a lot toward self-esteem and self-confidence,” she says. “The kids are feeling like, ‘I can learn and I can learn well.’”

How the far-right has shifted France’s political center of gravity

Two French presidential candidates are moving toward right-of-center policies. But it’s not clear that French voters find either of the shifts credible.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

As next year’s presidential elections in France approach, the two front-runners are trying on each other’s clothes.

Marine Le Pen, traditionally a candidate of the extreme right, is seeking more moderate voters by steering her party, the National Rally, toward the middle ground of French politics. More surprisingly, perhaps, President Emmanuel Macron is veering sharply rightward, shocking many of his supporters and raising questions about the boundaries of acceptable political discourse.

Mr. Macron campaigned as a fresh, young reformist progressive for the 2017 presidential elections. But his government has, in recent months, adopted harsher rhetoric on hot-button issues such as Islamism, secularism, and law and order, positioning itself as the guardian of traditional French values.

Meanwhile, Ms. Le Pen has continued her push to give her party a more moderate image. She no longer advocates leaving the European Union or its currency union; she has moderated her opposition to the free flow of European citizens around the Continent, and she has even presented herself as an environmentalist.

“We are seeing [National Rally] ideas have become normalized and a structural part of mainstream debate,” says political scientist Gilles Ivaldi. “That is a reality.”

How the far-right has shifted France’s political center of gravity

As next year’s presidential elections in France approach, the two front-runners are trying on each other’s clothes.

Marine Le Pen, traditionally a candidate of the extreme right, is seeking more moderate voters by steering her party, the National Rally, toward the middle ground of French politics. More surprisingly, perhaps, President Emmanuel Macron is veering sharply rightward, shocking many of his supporters and raising questions about the boundaries of acceptable political discourse.

“We are seeing [National Rally] ideas have become normalized and a structural part of mainstream debate,” says Gilles Ivaldi, who teaches at Sciences Po and the French National Centre for Scientific Research in Paris. “That is a reality.”

Two incidents in recent weeks have crystallized the new tone of Mr. Macron’s government, which he has always characterized as neither right- nor left-wing.

In a broadcast debate with Ms. Le Pen, Interior Minister Gérald Darmanin accused her of being “soft” on radical Islam, vaunting the muscular legislation on Islamist “separatism” that he presented to Parliament on Feb. 1.

A few days later, another minister called for an investigation into “Islamo-leftism” in French universities, using a phrase commonly heard only in extreme right-wing circles, which she said was “poisoning society.”

“The government is courting public opinion in some pretty nauseating places,” said the president of the Sorbonne University, Jean Chambaz. “They should be managing the [COVID-19] crisis instead of preparing for the elections.”

Borrowing from the far-right

Almost since Ms. Le Pen’s father, the Holocaust-denying Jean-Marie Le Pen, founded the National Front (since renamed the National Rally), mainstream politicians in France have been borrowing the far-right’s rhetoric on its key issues, immigration and law and order.

In 1990 President François Mitterrand, a Socialist, said France had gone beyond “the threshold of tolerance” on immigration. A year later his center-right rival, former President Valéry Giscard d’Estaing, warned of a foreign “invasion.”

Another center-right former president, Nicolas Sarkozy (to whom Mr. Macron is known to turn regularly for advice), wanted to ban Muslim women from wearing their veils in public, and a Socialist interior minister, Manuel Valls, once called for the expulsion of all Roma from France.

World events have also played their part in the normalization of attitudes that were once beyond the pale, suggests Thomas Guénolé, a political analyst.

“After World War II, it was impossible to imagine a far-right party after France’s participation in the Holocaust. No one tolerated extremism,” he says. “But the nationalist movement was always present, and the Sept. 11 attacks created a new anti-Muslim paranoia. It became acceptable to invite extreme voices onto French TV and in politics. The general atmosphere completely changed.”

Though Mr. Macron campaigned as a fresh, young reformist progressive for the 2017 presidential elections, he has lost much of his bloom, worn down by the protests of the Yellow Vest social movement in 2018-19 and then by his awkward handling of the pandemic.

His government has, in recent months, adopted harsher rhetoric on hot-button issues such as Islamism, secularism, and law and order, positioning itself as the guardian of traditional French values.

The so-called global security law, still before Parliament, offers police much greater powers of mass surveillance than they currently enjoy, including the use of facial-recognition software, and would also outlaw the “provocative identification” of police officers in photos or video, even those exceeding their authority, so as to protect their “physical and psychic integrity.”

Another draft law, designed to “strengthen republican principles” according to its title, is aimed at “Islamist separatists,” banning home schooling, giving the state more control over religious organizations’ funding, and allowing the authorities to close or remove the leadership of mosques. Critics complain that the law stigmatizes France’s 5 million-strong Muslim community.

Some observers suggest that Mr. Macron is concentrating on such issues as a way to distract attention from his political difficulties. But such tactics have broader implications, says Emiliano Grossman, a political analyst. “Once you make far-right arguments acceptable, they stay acceptable,” he says. “So even if it is a short-term [electoral] strategy, it has long-term effects.”

The “majority of French people share our ideas”

As Mr. Macron seeks votes across the aisle, Ms. Le Pen has continued her push to give her party a more moderate image by rebranding it under a new name and logo, hiring a younger and more diverse staff, and publicly shunning her father in a bid to shake off the neo-fascist image the party had projected.

She has also abandoned some key planks of the former National Front’s platform, recognizing that they were widely unpopular. She no longer advocates leaving the European Union, nor its common currency, the euro; she has moderated her opposition to the free flow of European citizens around the Continent. Ms. Le Pen has even presented herself as an environmentalist, in what observers see as an effort to appeal to Green party voters disillusioned with the president.

Her efforts have borne fruit, up to a point. In a March poll for the Journal du Dimanche weekly, 43% of respondents said they agreed with her political program, but only 28% said they shared the party’s values.

She has been more successful, it seems, in helping to move the center of gravity of French politics closer to her outlook. Even Mr. Macron, elected as a wholehearted supporter of globalization, now proposes the sort of “regulation of globalization and economic patriotism” that Ms. Le Pen claimed as the heart of her ideology recently at a meeting with the Anglo-American Press Association in Paris.

“The immense majority of French people share our ideas, which are perfectly reasonable,” she said. “So our political opponents are having trouble today not stepping into our territory.”

Mr. Macron’s election in 2017, at the head of La République En Marche, a brand-new political organization that won votes from traditional supporters of both left-wing and right-wing parties, shattered France’s two-party system. That has left large numbers of voters without any party affiliation – a situation that both Mr. Macron and Ms. Le Pen hope to exploit.

It is not clear, however, that either of them will be able to do so by next April when the presidential election is due. Too many people who voted for Mr. Macron in the last presidential elections are too disappointed in his performance to vote for him again; too many of the moderates whom Ms. Le Pen would like to seduce are not persuaded that her new image is more than skin-deep.

That could lead to widespread abstention, some observers predict. “I’m seeing it in the latest opinion polls and hearing it all around me,” says Mr. Guénolé, the political scientist. “More people are saying that if it comes down to Macron and Le Pen in the second round [of the presidential election], they’ll just stay home.”

The Explainer

Why influx of migrants is so high – and how US can respond

We’ve asked a few basic questions about the historic levels of immigrants crossing the U.S.-Mexico border. Here’s what we found.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

The United States is facing levels of irregular immigration this year that could exceed anything seen in 20 years. Immigration officers encountered more than 170,000 migrants at the border in March, accelerating a trend that began late last year. Just under 19,000 of those arriving were unaccompanied children, almost 8,000 more than the previous monthly record set in May 2019.

Why the surge? As has been the case since 2014, a big factor is families and children fleeing Central America to escape poverty, gang violence, poor governance, and natural disasters.

Add a rebounding American economy – also affecting flows of migrants from Mexico – and the U.S. can appear like a particular land of promise. President Joe Biden has also taken a notably less harsh approach to immigration than his predecessor, Donald Trump.

The Biden administration is seeking short-term responses, including through diplomacy. Long-term solutions would involve steps such as improving a byzantine and backlogged asylum system, offering more short-term work visas, and punishing companies that exploit unauthorized migrant labor, says Irasema Coronado, director of the Arizona State University School of Transborder Studies. But substantial reform would take congressional approval, rendering it all but fanciful given the 50-50 Senate.

Why influx of migrants is so high – and how US can respond

The rapid increase in irregular immigration raises the prospect of U.S. border apprehensions and encounters this year exceeding anything seen in two decades.

A record number of unaccompanied minors arrived last month, scrambling immigration services to increase capacity. Sheltering them alone is reportedly costing more than $60 million each week.

After an initially sluggish response, President Joe Biden’s administration is seeking short- and long-term solutions to the potential humanitarian crisis, likely without the aid of a stubbornly divided Congress.

What is the current situation on the southwest border?

The past few months have been chaos.

According to monthly figures from Customs and Border Protection (CBP), immigration officers encountered more than 170,000 migrants at the border in March, accelerating a trend that began late last year. About 100,000 migrants were expelled under Title 42, permitting refusal of entry to prevent the spread of infectious disease. Just under 19,000 of those arriving were unaccompanied children, almost 8,000 more than the previous monthly record set in May 2019.

Border crossings rise and fall cyclically, increasing in the first half of the year, with warmer weather and seasonal employment, and later dropping. Unique about this year is the sheer volume of arrivals, says Jessica Bolter, an associate policy analyst at the Migration Policy Institute

During the COVID-19 pandemic, Health and Human Services reduced its shelter capacity to comply with social distancing guidelines. But even full capacity wouldn’t have been able to meet current demand. Entering an overloaded system, many children are spending weeks in temporary CBP shelters meant to house them for no more than 72 hours, without showers, programming, or the ability to contact family.

“The number of people who are coming don't constitute a crisis,” says Ms. Bolter. “But the way that the government has managed it or not managed it has led to some crisis-like conditions.”

What’s causing the increase in border crossings?

A mix of circumstance and policy change. Since 2014, irregular immigration at the southwest border has been dominated by families and children fleeing Central America to escape poverty, gang violence, poor governance, and natural disasters, says Tony Payan, director of the Center for the United States and Mexico at Rice University’s Baker Institute for Public Policy.

The same factors are at work today, he says – including two hurricanes that buffeted Guatemala and Honduras late last year and are likely causing increased emigration from the two countries. Add to those factors the rebounding American economy, and the U.S. can appear like a particular land of promise for those in Central America continuing to shoulder the economic burden of COVID-19. (That has helped fuel a resurgence in migrant numbers from Mexico, too.)

Mr. Biden has also taken a notably less harsh approach to immigration than his predecessor, Donald Trump. After facing a similar surge in 2019, the Trump administration responded with near-draconian border policies in 2020, often turning migrants away before they could even reach the U.S.

“It is clear that there are people that understood that the Biden administration would be more lenient and more generous,” says Irasema Coronado, director of the Arizona State University School of Transborder Studies.

Tangible policy change between the two administrations has come in three areas. The Biden administration is no longer expelling children under Title 42, is no longer separating families at the border, and has ended the Migrant Protection Protocol – also known as “remain in Mexico” – which forced those seeking asylum to wait in Mexico until their hearing.

Smugglers will often exaggerate policy changes to boost business, says Ms. Bolter, and it’s unclear just how informed many migrants are before they undertake the often-perilous journey north. Easing coronavirus restrictions in the Americas has also contributed to the influx, experts say.

How is the Biden administration responding?

It wasn’t until late February and early March (before Health and Human Services Secretary Xavier Becerra was confirmed) that increasing shelter capacity became a priority for the administration, says Ms. Bolter.

Since then the administration has sought to add facilities for incoming migrants and named a special envoy to the Northern Triangle, reflecting a Biden focus on diplomacy. The president also tapped Vice President Kamala Harris to lead a policy response to the issue.

Long-term solutions would involve steps like simplifying the byzantine U.S. asylum system – with more than 1.3 million cases assigned to around 460 judges – offering more short-term work visas, and punishing companies that exploit unauthorized migrant labor, says Professor Coronado. Substantial reform would take congressional approval, though, rendering it all but fanciful given the 50-50 Senate.

That reality leaves the Biden administration – which recently struck deals with Mexico, Honduras, and Guatemala to increase border enforcement in their countries – in a bind, says Mr. Payan.

“It needs to be regularized. … It needs to be stopped,” he says. “But how?”

Essay

In Maine, a small secondhand bookstore soldiers on

Our essayist visits a humble yet thriving bookstore that answers this question: Is there anything more essential to life than a good book?

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By Robert Klose Correspondent

In one of Bangor, Maine’s poorest districts is a secondhand bookstore. A practical person might ponder what essential service Pro Libris Books provides to an impoverished neighborhood, which raises the question of what one considers essential.

What a wonderful, wonderful thing to have a bookstore in one’s midst in an electronic age when so many bookstores – small independents and mega-outfits alike – have evaporated. Bookseller Eric Furry has plied his trade here since 1980 and, happily, still turns a profit.

If I’m not mistaken, many patrons are here to be – and I choose this word carefully – comforted. The familiar titles and their affordability, the quirky touches (a bumper sticker announcing, “Maybe the hokey-pokey is what it’s all about”) turn me back to considering what is indeed essential.

When I broached the topic with Mr. Furry, he recalled a woman who gave him a $20 bill for a $9.50 sale and told him to keep the change, remarking, “I just don’t want you to ever go away.” Pro Libris Books is evidence that man (or woman, or child) does not live by bread alone.

In Maine, a small secondhand bookstore soldiers on

The Dutch Renaissance humanist Erasmus of Rotterdam once wrote, “When I have a little money, I buy books; and if I have any left, I buy food and clothes.”

This thought came to mind as I drove through one of Bangor, Maine’s poorest neighborhoods en route to a small, offbeat, secondhand bookstore that distinguishes an otherwise careworn street and bears the lofty moniker Pro Libris Books. A practical person might ponder what essential service a bookstore provides to an impoverished neighborhood, which raises the question of what one considers essential.

What a wonderful, wonderful thing to have a bookstore in one’s midst, especially in a place where other needs may incessantly intercede, and in an electronic age when so many bookstores – whether of the small, independent, mom and pop variety, or mega-outfits like Borders – have evaporated from our communities, seemingly overnight. Pro Libris Books is an unassuming but well-ordered cave of a shop occupying the ground floor of a peeling-paint clapboard building. Its facade is adorned with a hand-lettered sign, its entrance flanked by a funky plastic chair in the form of a hand. The owner, Eric Furry (is there a more appealing name for a bookseller?), has plied his trade since 1980 and, happily, still turns a profit.

Mr. Furry, a small septuagenarian with an outsize crop of salt-and-pepper hair, touts his business as “A Reader’s Paradise.” This seems to be enough to attract the rich variety of types I have observed there: high professionals, children, loquacious bookworms, students, college professors, and even, reflecting the neighborhood, a fair share of huddled masses yearning to read free.

When I asked Mr. Furry if anyone notable had ever visited his shop, he quietly divulged appearances by authors Stephen King, William Kotzwinkle, Lynn Flewelling, and Allen Ginsberg, but he said this with reticence, as if unwilling to rank his clientele.

As I wander the stacks, dividing my time between titles and observing the other visitors, I note the interplay between patron and proprietor. Not everyone is there to buy. If I’m not mistaken in my interpretation of body language, my impression is that many are there to be – and I choose this word carefully – comforted. The familiar titles, the affordability of the volumes, the quirky touches (a coffin-turned-bookcase from the set of a Stephen King movie; a bumper sticker announcing, “Maybe the hokey-pokey is what it’s all about”; Mr. Furry’s roaming cat) return me to the consideration of what we need, of what is indeed essential. When I am visiting Pro Libris Books, I find myself siding with celebrated author John Updike, who once said, “Bookstores are lonely forts, spilling light onto the sidewalk. They civilize their neighborhoods.”

I think Mr. Furry would agree, as would his customers. When I broached the topic of necessity with him, he recalled a woman who gave him a $20 bill for a $9.50 sale and told him to keep the change, remarking, “I just don’t want you to ever go away.” And then there was the man who sent him $80 out of the blue because he was worried about how Mr. Furry was faring during the pandemic-induced lockdown. I asked about his survival secret. The answer: “Low overhead. And a loyal clientele.”

The neighborhood might profit from, say, a supermarket, but the presence of Pro Libris Books and the community it serves is evidence that man (or woman, or child) does not live by bread alone, and that it is important to go on caring, even – and perhaps especially – in parlous and uncertain times.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Democracy’s strength: Eyes on the spies

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

President Joe Biden’s inbox on foreign affairs is quite full. China’s war jets are harassing Taiwan. Russia has amassed troops on the border with Ukraine. Iran is stepping up production of weapons-grade uranium. Yet amid all these threats, one strength that the U.S. commander in chief can count on is happening over two days of hearings this week in Congress.

America’s adversaries are amazed at – and probably watching – the twin public briefings April 14-15 by the top intelligence chiefs about the incipient global challenges for the United States. These quadrennial open-session assessments reflect core values not found in authoritarian regimes: transparency and accountability, even for secretive spy agencies.

Those values are rooted in a belief in the inherent rights of individuals, including the right to grant sovereignty to elected leaders. Autocrats believe only they bestow such rights. Fearful of their own people, they try to gain legitimacy by creating enemies and conflicts abroad.

For democracies, the best weapon against these threats is to showcase the ability of citizens to participate meaningfully in self-government. The on-camera hearings this week serve as a marvel of freedom’s strengths.

Democracy’s strength: Eyes on the spies

President Joe Biden’s inbox on foreign affairs is quite full. China’s war jets are harassing Taiwan. Russia has amassed troops on the border with Ukraine. Iran is nearing production of weapons-grade uranium. The Taliban appear to be winning the Afghanistan War. And who knows what North Korea is doing. Yet amid all these threats, one strength that the U.S. commander in chief can count on is happening over two days of hearings this week in Congress.

America’s adversaries are amazed at – and probably watching – the twin public briefings April 14-15 by the top intelligence chiefs about the incipient global challenges for the United States. These quadrennial open-session assessments reflect core values not found in authoritarian regimes: transparency and accountability, even for secretive spy agencies.

Lawmakers are grilling the nation’s top spooks, making sure this hidden side of government is as clear as possible about its warnings, honest about its suggestions, and open about its responsiveness to the governed.

“The American people should know as much as possible about what their intelligence agencies are doing to protect them, consistent with the need to safeguard sensitive sources and methods,” said Avril Haines, the director of national intelligence, during her confirmation hearings in January.

While the U.S. has made many mistakes in foreign conflicts, it has also gained wisdom by a commitment to open deliberation and civic participation for important decisions.

“Democracy’s strengths are the very attributes that authoritarians most fear: the inherent demand for self-examination and criticism, and the capacity for self-correction without sacrificing essential ideals,” states a report released Tuesday by Freedom House, in partnership with the Center for Strategic and International Studies and the McCain Institute.

That report recommends the U.S. and its partners increase investments in the pillars of their democratic societies: openness, accountability, inclusiveness. This means free and fair elections, vibrant news media, and active watchdog groups. All these pillars are rooted in a belief in the inherent rights of individuals, including the right to grant sovereignty to elected leaders. Autocrats believe only they bestow such rights. Fearful of their own people, they try to gain legitimacy by creating enemies and conflicts abroad.

For democracies, the best weapon against these threats is to showcase the ability of citizens to participate meaningfully in self-government. Spy agencies need to be clandestine and opaque in their daily intelligence operations. They are the “eyes and ears” for the nation’s defense. But at critical times, that secrecy bends to democratic fundamentals. The on-camera hearings this week serve as a marvel of freedom’s strengths.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Why God is relevant

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 4 Min. )

-

By Evan Mehlenbacher

Sometimes learning about God may be low in a list of pressing priorities (or absent from it altogether). But to know God’s nature and presence is to find the inspiration, love, and healing that meet our everyday needs, as a man experienced when he fell ill and feared for his life.

Why God is relevant

While attending college, I spent time wondering what to do with the rest of my life. One afternoon while entertaining career possibilities, I thought about becoming a full-time Christian Science healer. No sooner did the option pop into my mind than I thought: “You can’t do that. You would have to think about God all the time!”

Thinking about God all the time felt ludicrous. There were so many other demands to think about. The list of other things to do seemed endless.

But as I considered the scope of God as infinite and omnipresent, as I had learned from my upbringing and my study of Christian Science, I remembered that God is not a sideshow. God is the main event. God is Life. Everything good is included within God’s infinitude. It was a jolting perspective to consider.

In a material, mortal view of the world, God can start to feel remote, irrelevant, even nonexistent. But Christ Jesus came to show us that we can look to God first for life and support. When hungry people needed food, he prayed to God with spiritual understanding, and they were fed. When sick people pleaded for health, he prayed to God, and they found themselves strong and healthy. He said, “Seek the Kingdom of God above all else, and he will give you everything you need” (Luke 12:31, New Living Translation). Jesus’ understanding of health, life, and provision in God enabled him to overcome the constraints of mortality and demonstrate that human needs of all kinds can be met through the love of God.

We can prove the reality of God’s care today. The Bible documents how God has spoken to humanity over the centuries through Christ, pointing the way out of mortality to immortality. The Christian Science textbook, “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures” by Mary Baker Eddy, explains how to put the teachings of the Bible into practice and to heal as Jesus expected his followers to heal.

In Christian Science, God is not a mysterious power that is hard to relate to. God is the Principle of all existence, the Mind that orders the universe, the Life that sustains all being, the Love that unites all. God is all good. With God, one has everything necessary to stay healthy, to live abundantly, and to be happy. We all experience extreme difficulties at times but to know God’s presence is to find the inspiration, love, and support that meet the need of the moment.

Many years ago, on the night I returned to my home from a trip overseas, I became very ill. I prayed, affirming that God was present and could heal, but my health was failing fast. At a point when I was barely able to think one or two words at a time, and was afraid that if I lost consciousness I would never wake up, my thoughts landed on the single word “God.”

This word held deep meaning for me. I knew that God was my Life, and could never be threatened, sickened, or lost. With this realization, a wave of peace swept through consciousness. I lost all fear of death and felt assured that everything was going to be OK. I decided it was all right to fall asleep for rest, feeling confident that I was safe because God was caring for me. When I awoke two hours later, I felt 90 percent well, and the remaining vestige of illness was gone very soon. The healing was decisive and welcomed.

Armed with a keen awareness of the power and presence of God as our divine Parent, who created us in the spiritual image of the Divine, we can defeat suffering and maintain order and peace. Science and Health states: “Rise in the strength of Spirit to resist all that is unlike good. God has made man capable of this, and nothing can vitiate the ability and power divinely bestowed on man” (p. 393). Each of us possesses spiritual might to claim our divine right to health, to resolve conflict with love, to act without fear, and to better our experience. We are divinely empowered to feel Life’s blessings to the fullest! Each day is an opportunity to exercise this power as we grow in spiritual understanding.

There isn’t anything more important to do than to understand God. To know God is to readily recognize God’s benefits. As I glimpsed many years ago when seeking direction for my life, when you have God, you have everything.

Adapted from an article published in the March 16, 2020, issue of the Christian Science Sentinel.

A message of love

The crossing

A look ahead

Thanks for joining us. Come back tomorrow: We’re working on a story about why German priorities during the pandemic include funding for the arts.