- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- ‘Hang on. Hold on.’ Surfside grief met with flood of solace.

- Afghans’ choice as US departs: Weak government or hated Taliban

- Can French law rein in cyberbullying? A court case may tell.

- Happy birthday, America, from a village in Bangladesh

- ‘Summer of Soul’ captures the music, and unity, of 1969 Harlem festival

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Biden-DeSantis in Florida: When politics takes a break

President Joe Biden visited South Florida yesterday for the most somber of reasons – to thank first responders and meet with grieving families after last week’s collapse of a condo building in the town of Surfside.

The trip wasn’t political, but politics loomed nonetheless. Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis, a Trump acolyte, has often been harshly critical of the Biden administration. There’s even speculation that President Biden and Governor DeSantis, a rising GOP star, could face each other on the ballot in 2024. Their interaction Thursday could easily have been rife with partisan tension.

So it was all the more striking to see, instead, a forthright display of common purpose and bipartisan unity. At a briefing, the two seated side by side, Mr. DeSantis praised the federal response and Mr. Biden in particular for being “very supportive.”

“You guys have not only been supportive at the federal level, but we’ve had no bureaucracy,” Mr. DeSantis said.

“I promise you,” the president replied, “there will be none.”

Putting his hand on Mr. DeSantis’ arm, Mr. Biden said the governor and Surfside mayor have been “completely open with me,” and that he’d boost federal coverage of Florida’s emergency response costs to 100%.

The Democratic mayor of Miami-Dade County, Daniella Levine Cava, also praised the Republican governor. “You’ve been a steady, calming, reassuring, but forceful voice every step of the way,” she said. “And it’s been a pleasure to partner with you, truly.”

Heading into July Fourth weekend, the scene was a welcome reminder that it’s possible, still, to be “united” states.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

‘Hang on. Hold on.’ Surfside grief met with flood of solace.

The Surfside building collapse has brought people from across Florida and beyond to help, to mourn, and to support those grieving and in need.

The makeshift memorial wall on Harding Avenue is where people come to see the faces of the missing. Family members and friends have posted photos of the 140 still missing and the 18 confirmed dead on a chain-link fence two blocks from where Champlain Towers South collapsed.

But the memorial has seen faces, too. Like Jimmy Blair, the 103-year-old resident who came to pray for a dear friend from the collapsed tower. Or Alex Calarino, who drove his motorcycle here from an hour away. “I just had to be here,” he said. Or the rescue workers and support staff still pulling at the rubble two blocks away. “I never thought I’d see anything like this,” says one.

The grief is like a black hole, President Joe Biden said Thursday as he visited with families. But the wall has also borne witness to the deeply human instinct to fill that hole.

For one entrepreneur who was about to open accommodations as an alternative to hotels for travelers, that has meant taking in 15 of the families that lost their homes. “We felt that we had a moral obligation to act,” he says, “and not sit on the sidelines and watch.”

‘Hang on. Hold on.’ Surfside grief met with flood of solace.

Felicia Roll is nearing tears as she approaches the makeshift memorial wall on Harding Avenue. The chain-link fence ahead is where family members and friends have posted photos of the missing, just two blocks from where Champlain Towers South collapsed last week.

She’s the caregiver for Jimmy Blair, a 103-year-old resident in another high-rise building near the ocean on Miami Beach, and as she pushes his wheelchair along the sumptuous array of flowers, together they look for the photo of one of Mr. Blair’s dearest family friends. He knew the woman from their days living in Brooklyn as members of a tightknit Orthodox Jewish community.

Mr. Blair hadn’t left his apartment for months, but even though it’s a cloudy, rainy day, he felt compelled to come. When they find the woman’s photo, Ms. Roll kneels next to him, takes his hand, and raises her other arm and begins to pray and weep.

“I was praying for those workers over there,” says Ms. Roll, who travels an hour each way to care for Mr. Blair. “Please, let them find at least one survivor.”

Mr. Blair, wearing a yarmulke, beckons a stranger near him. “What to do? What to do?” he says, his voice rasped with age and grief. “Everyone comes into this world, comes up against the world, and then leaves it. But God is great, and he blesses us, forever and ever. Amen.”

With more than 140 still missing under the rubble of tangled concrete and debris and 18 confirmed dead, it remains a time of grief and mourning in Surfside, Florida, as well as much of the nation.

“The waiting, the waiting is unbearable,” President Joe Biden told the families on Thursday, after he and the first lady, Jill Biden, placed a wreath of white flowers at the memorial fence and spent time speaking privately with family members.

In the midst of such numbing moments of despair, there’s also a deep-seated human instinct to find solace by gathering, and as the community here confronts such a sudden eruption of chaos and loss, many come to offer the smallest of gestures of beauty and hope.

“I just had to be here”

Alex Calarino, a mechanic who also lives an hour away, rode his motorcycle down on Wednesday. “I just had to be here,” he said at the memorial wall. “I just wanted to pay my respects.”

The president, who lost his first wife and a daughter after an automobile accident in 1972, and then his oldest son to illness in 2015, told family members how maddening it can be when others, meaning well, attempt to say they know what grieving families feel.

“No matter what the outcome, the people you love, the people you may have lost, they’re going to be with you always – part of your soul, part of who you are,” the president said in a video posted by family members.

“Be patient with one another. Hang on. Hold on,” he said. “I don’t want you to feel like you’re being sucked into a black hole in your chest; there’s no way out. But there is.”

At the site of the collapse, officials ordered rescue workers to halt their efforts much of the day during the president’s visit, after concerns that parts of the building still standing might crumble. Rescue teams, including specialists from other states, as well as nations including Israel and Mexico, resumed their work late Thursday.

Moments of strength and weakness

Removing the concrete debris, piece by piece, even while still searching for survivors and human remains, is emotionally straining work – akin to soldiers who experienced the ravages of war, President Biden said.

“It’s so surreal,” says Brock Simmons, an intern with Hurst Jaws of Life in Shelby, North Carolina, which provides specialized tools for rescue workers. “I never thought I’d see anything like this.”

Mr. Simmons was on a sales trip with colleagues last week, hoping to observe and get some experience. But the trip was cut short and he and another Hurst employee rushed to Surfside after the complex collapsed. Now they are helping to supply new cutter and spreader tools used by Jacksonville Fire and Rescue, and providing service and repair for the older tools being used on what workers call “the pile.”

The team from Jacksonville had just completed a 12-hour shift on the pile from midnight to noon and were sleeping in the workers’ camp. “They’re all just exhausted – you can see how hard it is on them,” he says.

“Sometimes all you can do is find a small, quiet corner and just cry for a little while, and let out some of that pressure that you’ve got building up,” Margarita Castro, a member of the Miami-Dade search and rescue team, told The Miami Herald. “We each have our moments of strength. We each have our moments of weakness.”

“A moment for all of us”

At the same time, amid such loss and devastation, there is also a deep-seated human instinct to help, and thousands of Miami residents and others around the country have felt impelled to offer what help they can give.

The partial collapse of Champlain Towers South last week was an intensely personal experience for Andreas King-Geovanis, and almost immediately he felt determined to do whatever he could to offer help for the surviving families who suddenly lost their homes.

A millennial entrepreneur and the CEO of Sextant Stays, which provides spacious accommodations for travelers as an alternative to hotels, Mr. King-Geovanis was born and raised in the New York borough of Manhattan. He was 11 years old on Sept. 11, 2001, living just a few blocks from the World Trade Center in Battery Park City.

“When that happened, we couldn’t go back to our home, just like these families,” he says. “My entire neighborhood was fenced off by the National Guard, and it was just such a chaotic scene. We spent the next month living in hotels or in friends’ houses on their sofas.”

His company was just about to open a new property in Sunny Isles Beach, a few miles north of Surfside. “We felt that we had a moral obligation to act and not sit on the sidelines, and watch and not just tweet out thoughts and prayers,” he says. “We knew that we were in a position to make a real impact.”

His company, which lists “empathy” and “community engagement” among its seven core values, is now hosting 15 of the families that lived in the partially collapsed complex.

He’s been overwhelmed, too, by the larger response of the community. Sports celebrities and others have helped provide over $10,000 in gift cards for the families, and each unit has been fully stocked with food and necessities. Anonymous donations of household items continue to be sent to his company’s warehouse.

“It hasn’t just been a singular effort, and though we were in a position to help, that’s not the focus,” Mr. King-Geovanis says. “This is a moment for all of us, and that’s why it has been so easy to rally everybody around one goal.”

Afghans’ choice as US departs: Weak government or hated Taliban

In whom can Afghans place their faith? The hated Taliban will not win any popularity contests, but neither will the government, faulted for corruption and a disconnect from the forces that would support it.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

As the Taliban have gobbled up territory at an accelerated pace, Afghan journalist Bilal Sarwary has monitored the predicament of Afghan officers and intelligence operatives from his native Kunar province. “Sadly, everywhere in Afghanistan is a front line now,” he says. Afghans are experiencing “psychological turbulence. People are terrified.”

That pressure grew today, as the United States and NATO declared that they had vacated the Bagram air base north of Kabul, the epicenter of Western military involvement in Afghanistan since 2001.

Afghans know Taliban tactics – blackmail and intimidation, spiked with explosive violence – and the insurgents would never win a popularity contest. But exposed also like never before is the widespread lack of faith in Afghan President Ashraf Ghani and his government, with its institutions eroded by corruption and its disconnect with ordinary Afghans laid bare, despite a 20-year investment of billions of dollars in Western aid.

“The government is weak because it really lost the connection with the people,” says Orzala Nemat, a Kabul-based analyst. “Although theoretically the president has always been talking about a ‘social contract,’ in practice he failed to deliver on that. ... As much as people hate the Taliban, they got fed up with very corrupt officials, and did not much bother about or support the government.”

Afghans’ choice as US departs: Weak government or hated Taliban

Every night, journalist Bilal Sarwary gets on the phone from his home in Kabul, checking in with friends stuck at Afghan military bases around the country as they fight advancing Taliban insurgents.

With the Taliban seizing control of one district after another, building momentum on the battlefield as American troops depart after nearly 20 years, these Afghans reach out to Kabul officials for leadership and support – and even extraction. But they rarely get a response.

“Soldiers and commandos are asking for food, water, and ammunition; they are asking to be evacuated,” says Mr. Sarwary, referring to the predicament of Afghan officers and intelligence operatives he knows who are from his native Kunar province.

“Sadly, everywhere in Afghanistan is a front line now. The fighting is at the doorstep of Afghans,” he says. Afghans are now experiencing “psychological turbulence. People are terrified.”

That pressure grew today, as the United States and NATO declared that they had vacated the Bagram air base north of Kabul, the epicenter of Western military involvement in Afghanistan since 2001.

Few doubted that the Taliban would push their advantage, or even aim for military victory, as they boasted of defeating the American superpower. Afghans know Taliban tactics, including blackmail, intimidation, and coercion, spiked with explosive violence and bloodshed; the insurgents would never win a popularity contest. So as America steps away from Afghanistan, raising the specter of civil war, the question emerges: When anti-Taliban sentiment is so strong, why is the Afghan government so weak – and distrusted?

The crisis has exposed as never before the widespread lack of faith in Afghan President Ashraf Ghani and his government, with its institutions eroded by corruption and political infighting, and its disconnect with ordinary Afghans laid bare, despite a 20-year investment of billions of dollars in Western aid and nation building.

“The government is weak because it really lost the connection with the people,” says Orzala Nemat, a veteran Kabul-based Afghan analyst. “Although theoretically the president has always been talking about a ‘social contract,’ in practice he failed to deliver on that, by concentrating – and overconcentrating – all government affairs into the palace.

“That’s why, as much as people hate the Taliban,” she says, “they got fed up with very corrupt officials, and did not much bother about or support the government.”

When will the last American troops exit?

It is not yet clear when the handful of remaining U.S. troops will leave, formally ending America’s longest-ever war.

The low-profile American departure, two months ahead of President Joe Biden’s Sept. 11 withdrawal deadline, comes as President Ghani’s government grapples with an unprecedented Taliban onslaught. In recent weeks, that advance brought scores of the country’s district centers under jihadi control – often without a shot being fired, as embattled Afghan troops surrender with promises of safe passage home.

Afghanistan ranked 165 out of 180 countries in Transparency International’s 2020 Corruption Perceptions Index. Indeed, a report today by the Afghanistan Analysts Network (AAN) pointed to government “neglect and incompetence” as much as “Taliban strength,” as a reason for the insurgents’ recent lightning advances.

Widespread Taliban attacks as the U.S. withdrew were “expected, but the scale of and speed of the [Afghan security force] collapse was not,” AAN reported.

President Biden’s April announcement of an unconditional, swift U.S. troop withdrawal “shifted the balance and nature of the conflict suddenly and decisively” in the Taliban’s favor, the AAN report said.

Unafraid now of once-devastating American airstrikes, the Taliban are engaging in scorched-earth tactics, which range from burning harvests and seeding orchards with land mines to destroying bridges and bulldozing roads.

When Mr. Ghani visited the White House a week ago, President Biden promised continued U.S. support, including a request of $3.3 billion for security assistance next year, which would include training and technical support from outside the country.

But is time running out for such plans?

On Tuesday, the U.S. commander in Afghanistan, Gen. Austin Miller, said, “Civil war is certainly a path that can be visualized if this continues on the trajectory it’s on right now.” That view was reinforced by a U.S. intelligence assessment, which warned last week that the Kabul government could fall within six months after Americans leave.

“The truth is, today the survival, security, and unity of Afghanistan is in danger,” Abdullah Abdullah, the government’s reconciliation envoy, said in recent days. “There is no better way than peace.”

But peace between the Kabul government and insurgents has not come, despite a U.S.-Taliban withdrawal agreement signed in early 2020, and intra-Afghan peace talks that began last September in Doha, Qatar.

At the same time, says Mr. Sarwary, the journalist, the government and the forces that would support it are experiencing a worsening “disconnect.”

The result of government weakness is clear to the Afghan security force members from Kunar who are followed by Mr. Sarwary, whose pleas for help go unanswered by officials in Kabul.

“President Ghani, from the get-go, failed to bring political cohesion, failed to gather everyone around the same table,” he says, referring to disunity that included dueling presidential inaugurations last year for Mr. Ghani and Mr. Abdullah, his longtime rival.

“Ghani might be fluent, he might be eloquent, he might have a lot of appeal in English, but his guys lack roots in the society,” says Mr. Sarwary. “Suddenly you had people with two passports – I call them ‘political tourists’ – and some guys who could not even speak Dari or Pashto, in parliament.”

That has led to the disconnect between Kabul – with its “bravado and empty statements, [where] people like painting a rosy picture,” he says – and frontline commanders, who “have been badly let down.”

“A lot of these [officials] have not picked up a coffin ... have not gone to a funeral,” says Mr. Sarwary. “A lot of them don’t feel that pain; they are detached from the consequences, from the reality. For some in the government – I stress, some – it means they are not aware.”

A lack of consistency

Frequent changes in the Cabinet and security top brass have added to command-and-control confusion and lack of consistency, as the Taliban have escalated violence.

“I wonder if it’s not so much about Taliban success, but more about this alienation of the Afghan people, and what drove this alienation so that people are so indifferent to the fate of this government,” says Ibraheem Bahiss, an Afghanistan analyst with the International Crisis Group.

He cites government lack of accountability, due to extensive funding by Western donors with different agendas, as well as endless political wrangling in Kabul.

Another factor has been U.S. and NATO troops who were “so unaware” of local dynamics – from village to valley to hamlet – that they were often used in local vendettas, with one side accusing another of being pro-Taliban, thereby turning entire areas against the government.

“Despite 20 years of massive military intervention, there hasn’t been a day of peace in Afghanistan, really,” says Ms. Nemat, the Afghan analyst.

“The majority of people know the Taliban are not Robin Hoods of Afghanistan, they are not the saviors,” says Ms. Nemat. “The Taliban leadership is also corrupt, and fighting for others’ interests.”

“None of the parties won the hearts of the people. ... The people are feeling they are hostage to two parties fighting each other,” she says. “The winner here is the one that will deliver peace, stability, and resources, but those are neither coming from the Taliban or the government.

“Of course, everyone will stand next to the [Ghani] government, because they are not ready for the nightmare of the Taliban to return,” says Ms. Nemat. “They will try to stand, but they are not happy with the government, because of their actions, because of their corruption.”

Can French law rein in cyberbullying? A court case may tell.

The trial of 13 people who harassed online a French teen who condemned Islam could indicate how the country will punish cyberbullying, an often overlooked and hidden crime.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Last year, Mila, a French teen, became the center of a cultural and political firestorm after she posted condemnations of Islam on social media. Though the right to blaspheme is legal in France, she quickly became the target of online harassment for her words, drawing around 100,000 hateful messages including death and rape threats.

Now, 13 people who threatened her are on trial for cyberbullying in what looks to be a landmark criminal case about online harassment. Under the law, it’s a crime to post comments that intentionally participate in mob bullying against a single victim.

France has seen an uptick in online harassment over the past decade – especially during the COVID-19 pandemic, when cyber harassment rose by 30% among young people during France’s first lockdown. According to the Institut Montaigne, a think tank, more than half of French people ages 11 to 20 have been victims of cyber harassment, while just 9% of parents thought their children were affected.

“I hope this affair opens people’s eyes, especially the government’s, to all the victims out there and the need for more training,” says Magali Chavanne of the anti-harassment nonprofit Cybhar’so. “Laws are great, but they need to be understood at all levels of the chain and then applied.”

Can French law rein in cyberbullying? A court case may tell.

In January 2020, Mila, a French teen, had just dyed her hair a pale mauve tint and wanted to show it off to her some 10,000 followers on photo-sharing social media platform Instagram. As she did so, she chatted about her likes and dislikes, before leaving a “Stories” video, where she stated that she hated all religion.

“The Quran is a religion of hate, Islam is” trash, said the Lyon high school student, who is a lesbian. “I’m not racist… you can’t be racist towards a religion. I’ve said what I think, I have the total right to do so. I don’t regret it at all.” She repeated her criticism of Islam in a November 2020 TikTok video that she posted after the jihadist killing of teacher Samuel Paty.

Her comments caused a social media firestorm – around 100,000 hateful messages including homophobic comments, death and rape threats, and the publication of her personal details online.

Mila, as she is identified publicly, was forced to drop out of school and has been put under police protection. And what might have remained online rants by an angst-filled teen quickly spawned a media blitz that lasted more than a year, and turned into political dynamite, with voices across the political spectrum debating Islamophobia versus freedom of expression.

Now, because blasphemy is protected by law in France and punishment for cyber harassment is in a fledgling state, the “Mila Affair” has turned into a test case for the definition, and potential consequences, of online bullying. Last week, 13 people ages 18 to 30 went to trial for their online remarks directed at the French teen, in what looks to be a landmark criminal case about online harassment.

“It’s horrible what happened to Mila but she’s become a kind of symbol of cyber harassment,” says Justine Atlan, general director of Association e-Enfance, a nonprofit that has set up a national helpline for victims of internet abuse. “This case has been important pedagogically, to show people how to become more responsible. Sending a message or tweet can seem like nothing, but you can end up in court for doing it.”

Finding a balance

Soon after Mila’s controversial video went viral, a legal complaint was brought against her for incitement to racial hatred, which was later dropped. The right to blasphemy is protected under an 1881 law and Mila has always maintained that she was criticizing a religion, not individuals.

Meanwhile, 13 people who attacked her online after her November TikTok video – ranging from a psychology student to an aspiring police officer – are being tried in the first high profile case using a 2018 law on cyber harassment. Under that law, it is a crime to post comments that intentionally participate in mob bullying against a single victim.

The new law helps take some of the guesswork out of defining what kind of language constitutes cyber harassment, as social media networks struggle to find a balance between freedom of expression and controlling hate speech.

“Before, you had to show why a certain comment was harassment. Now, we have something innovative in the law,” says Gérard Haas, a Paris-based lawyer who specializes in new technologies and cybersecurity. “It’s the repetitive act that is key. People can no longer participate in an online lynching of one person. I think it’s a good thing to scare people who are trying to scare others.”

France has seen an uptick in online harassment over the past decade – especially during the COVID-19 pandemic, when incidents of cyberbullying rose by 30% among young people during France’s first lockdown.

The phenomenon affects people of all ages, but especially young people, and calls for help to Association e-Enfance rose by 54% in 2020 from the year before. According to an April 2020 study by the Institut Montaigne, a Paris-based think tank, more than half of French people ages 11 to 20 have been victims of cyber harassment, while just 9% of parents thought their children were affected. Many parents don’t monitor their children’s phones or computers once they reach high school.

Sexting and revenge porn – the dissemination of sexually explicit messages or photos online – is a particular problem for girls and women. This past March, Alisha, a 14-year old French girl was found dead in the Seine after having been violently beaten by two classmates. It was later discovered that her phone had been hacked, and intimate photos of her had been widely spread on social media platform Snapchat.

Since 2013, the government has organized a competition between schools for the best PSA announcement about harassment, and in 2016, Education Minister Najat Vallaud-Belkacem made tackling cyberbullying one of her top priorities.

But nonprofits say that there are still too many victims, and that efforts to counter cyberbullying are hindered by a failure of the police to fully acknowledge the problem, and by the difficulties in providing accessible legal aid to victims.

“I hope this affair opens people’s eyes, especially the government’s, to all the victims out there and the need for more training,” says Magali Chavanne, secretary and spokesperson for Cybhar’so, a nonprofit near Toulouse that works on preventing cyber harassment among young people. “There need to be more specialists to help victims. Laws are great, but they need to be understood at all levels of the chain and then applied.”

A fresh opportunity

Many observers cringe at the gigantic proportions Mila’s case has reached – as well as the months-long debate it spurred – but they agree that it has provided a fresh opportunity to raise awareness of a situation that is not getting any better despite the government’s intentions.

The Stop Fisha collective was founded last year and is trying to fight cyber harassment and cyber-sexism preemptively. More than 20 young female members scour the internet, working to close down suspicious accounts as well as support victims who are hesitant to speak out to adults.

Other nonprofits are focusing on prevention efforts, like Cybhar’so and the Amazing Kids association, both of which partner with local groups and offer workshops in schools. Mental health professionals say prevention is better than cure.

“Adolescents have an extremely high ability to hide their emotions, so it can be very difficult for parents to spot when harassment is happening,” says Catherine Verdier, a Paris-based psychologist for children and adolescents, and co-founder of Amazing Kids.

“The multiplying effect of online harassment – one piece of information can reach astounding numbers with just a few clicks – makes victims feel like the whole world sees them in a certain way. It doesn’t take long before their entire sense of self is eroded,” she adds.

On July 7, French judges will give their verdict in the case; 12 of the 13 defendants face up to six-month suspended prison sentences. During the trial, one defendant apologized for his comments; another said he was only trying to attract more online followers. One young woman said she didn’t see the difference between the freedom of expression Mila used in her posts and her own angry Twitter responses.

Mila is seeing a therapist to cope with her new situation. She’s slowly returning to social media and still says she has no regrets.

“To ask me to stop [using social media] is like asking a woman who has been raped to never go out into the street so she won’t be raped again,” said Mila during her trial. “If I had stopped, it would allow everyone to walk all over me. I just want to exist, to enjoy the time I have left.”

Commentary

Happy birthday, America, from a village in Bangladesh

As this writer in Bangladesh proved, insatiable curiosity and dogged determination can expand your experience far beyond the confines of your community.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

-

By Rezaul Karim Reza Correspondent

Twenty years ago, we had no paved roads or electricity, let alone internet, in my Bangladeshi village. But by listening to Voice of America’s “Learning English” programs on the radio, I developed my English a bit.

In 2010, our village was electrified. I bought a smartphone and connected with the internet. I opened a Facebook account and tried to reach out to Americans. A Virginian responded.

He and his kindhearted wife sent me a great many books and small gifts related to American history, culture, and literature. The books played a vital role in my life. I read “Uncle Tom’s Cabin,” which helped me learn of the American Civil War. While reading “The Grapes of Wrath,” I felt like I was moving with the Joad family to California.

By corresponding with a Texas friend, I came to know that everything is BIG in Texas through the photos he sent me.

I was unstoppable and met more Americans.

Now, from my tiny village, I can explore through the American wilderness and share my thoughts about Martin Luther King Jr.’s role during the civil rights movement.

I want to thank all these good Americans who brought their people, culture, and history to me, and “Happy birthday to you, America.”

Happy birthday, America, from a village in Bangladesh

America, I am sending you a happy birthday wish from a small Bangladeshi village. I knew nothing about you before 2001, when 9/11 shook you and turned the world around. Twenty years later, as I wish you “Happy birthday,” I know about you, your people, and their history.

I first heard about America when I was in junior high school. Our geography teacher showed us a world map, and his finger stopped on the line that read USA. “This is America,” he said. We were curious why the teacher mentioned America specifically, but he did not explain it to us any further.

Then in 2001, when I was about to finish 10th grade, we watched the horror of 9/11 on a black-and-white TV in our village, and I saw America for the first time. While watching the huge plume of smoke and the towers falling down, I saw Americans. It was the first time I heard them speak, and something compelled me to speak like them, so I started learning English.

We had no satellite television channels other than the government-run TV station. We had no paved roads or electricity, let alone internet, so learning English was tough. After I found a radio set with my uncle, I tried to connect it with some English broadcasting channels. Thus, I discovered Voice of America. By listening to VOA’s “Learning English” programs, I developed my English a bit.

I wrote a letter to VOA asking for some books. They sent me some booklets and magazines and a beautiful photo of Washington, D.C. I bought some grammar books and started reading English dailies in Bangladesh. As my English developed, I started to know about America and its people.

In 2010, our village was electrified. There were color TV sets with multiple channels. I bought a smartphone and connected with the internet provided by a phone company. I opened a Facebook account and tried to reach over to Americans. Although many of them did not respond, some were friendly and responded, including a Virginian.

My Virginia friend and his kindhearted wife sent me a great many books and small gifts. The gifts were often related to American history, culture, and literature. The books played a vital role in my life. I read “Uncle Tom’s Cabin,” which helped me learn of the American Civil War. The couple included some fine works of great American writers, including Washington Irving and John Steinbeck. While reading “The Grapes of Wrath,” I felt like I was moving with the Joad family to California. “The Grapes of Wrath” added another lesson in American history to my list, the Great Depression. I posted some of my already-learned history notes in a Facebook group and reached out to some more Americans.

I corresponded with my Texas friend through Facebook Messenger. He told me about the Texas-Mexico war at the Alamo, and I came to know that everything is BIG in Texas through the photos he sent me. Rodeos, ranchos, and rattlesnakes were part of our discussion almost every day. He also sent me books, pens, and writing paper. I learned more about cowboy culture from the books, and when I hold the colorful pens, I feel a sense of my own American dream while studying, teaching, and writing stories for and about America.

Then, I moved to California virtually, when I met a friend from the “grizzly bear state.” From the Spanish settlers to the gold rush to migrants’ lives during the Depression, my California friend brought me U.S. history. Through our conversation, I also discovered a wild America, from far-away Bangladesh. He introduced me to the Giant Forest, full of sequoia trees; Death Valley National Park; roadrunners; California quail; and the sun and surf of the beaches.

I was unstoppable and met more Americans. One of them served in the U.S. Army. My Army friend brought me world history – the Vietnam War, Korean War, Gulf War, Cuban missile crisis, and more. He was stationed in Iraq during the war there. We corresponded about his experience fighting for his country, leaving everybody back on U.S. shores. It seemed the life of a soldier is very hard.

If America did not exist, I would not be who I am today. Now, from my tiny village, I can explore through the American wilderness, walk through the trails in the sequoia forest, and argue with my friends about why Native Americans are called Indians. Now I understand and can share my thoughts about Martin Luther King Jr.’s role during the civil rights movement with other people around the world.

I want to thank all these good Americans who brought America – its people, culture, and history – to me here in Bangladesh. I thank you very much, friends, and “Happy birthday to you, America.”

Rezaul Karim Reza is a substitute English teacher in Bangladesh and a freelance writer.

Film

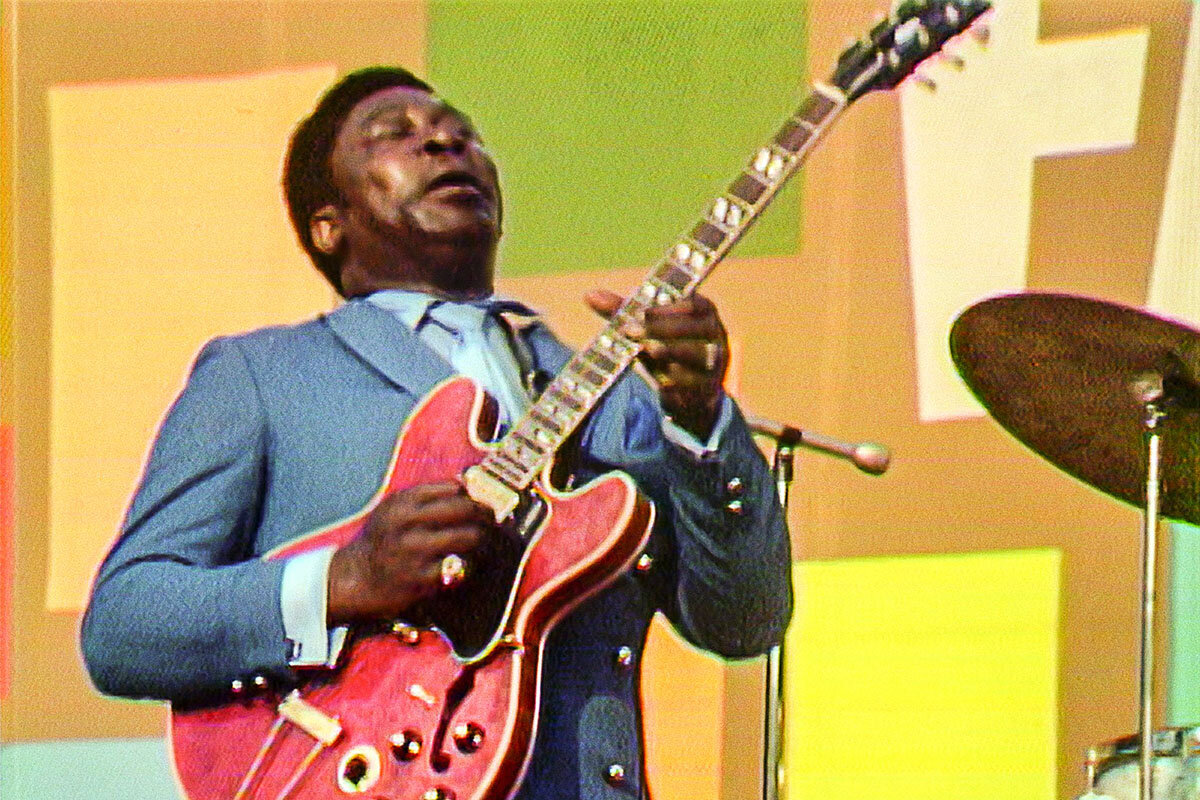

‘Summer of Soul’ captures the music, and unity, of 1969 Harlem festival

“Summer of Soul” highlights the unifying performances that took place some 50 years ago at the Harlem Cultural Festival in New York City. In a five-star review, film critic Peter Rainer calls the documentary a timeless project “of major cultural significance.”

-

By Peter Rainer Special correspondent

‘Summer of Soul’ captures the music, and unity, of 1969 Harlem festival

Over six weekends in the summer of 1969, the Mount Morris Park in New York’s Harlem neighborhood was thronged with over 300,000 jubilant attendees as they heard some of the greatest Black and Latino performers of the day at the peak of their musical powers. The event was put on by the Harlem Cultural Festival and unofficially dubbed “the Black Woodstock,” referencing that other music festival, some 110 miles upstate, which it overlapped.

So why, unlike Woodstock, was this event subsequently all but lost to history? The new documentary “Summer of Soul” – directed by Ahmir “Questlove” Thompson, the extraordinarily poly-talented author and co-founder of hip-hop band The Roots – is a reclamation project of major cultural significance.

The backstory is that over 40 hours of the Harlem concert were filmed by the TV producer Hal Tulchin, who wanted to fashion the footage into a feature for television and was turned down by all the major networks. When he died in 2017, the footage had been sitting in his basement for nearly 50 years. Except for some portions shown in 1969 on the local New York public television station, nothing of the filmed concert has been available for audiences to view until now.

The movie, edited by Joshua Pearson, should take its rightful place among such classic live performance documentaries as “Woodstock,” “Amazing Grace,” “Monterey Pop,” “Gospel,” “T.A.M.I. Show,” and “Wattstax.”

What differentiates it from many of those movies is the extent to which Thompson situates the performances in a larger social context. (The film’s subtitle is “... Or, When the Revolution Could Not Be Televised,” an allusion to the 1960s Black Power slogan and Gil Scott-Heron song.) The summer of 1969, a year after the civil unrest in Harlem following the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., is convincingly posited as a turning point in an era when Black style – personal, political, and musical – was becoming more forthrightly pronounced and prideful.

The party atmosphere in the park was about much more than summer fun. Thompson interviews several of the people who were in the audience for the event, and what we repeatedly hear from them is how unifying it felt to be there. Says one attendee, “We needed to feel like family.” Says another, “That concert was like a rose coming through cement.”

And what a concert it was! Each weekend was devoted to a different type of music – gospel, pop, rock, R&B, blues, Afro/Latin jazz – but Thompson overlaps the categories into a continuous stream of performance. The artists share the same almost beatific look: They know they are in the right place at the right time. B.B. King belts out “Why I Sing the Blues”; the Edwin Hawkins Singers transport the crowd with “Oh Happy Day”; 19-year-old Stevie Wonder knocks out an explosive drum solo; David Ruffin, who had recently left The Temptations, offers up a mellifluous version of “My Girl.” Nina Simone rasps out the incendiary “Backlash Blues.” The South African Hugh Masekela, and the Latin all-stars Ray Barretto and Mongo Santamaria, highlight the festival’s cultural range.

Gladys Knight, interviewed in the present, talks about how deeply good it felt for her (and the choreographically incomparable Pips) to be up on that stage. Billy Davis Jr. and Marilyn McCoo of The 5th Dimension, unfairly branded at the time as “the Black group with the white sound,” recount their fears of being rejected by the Harlem crowd. They needn’t have worried. Their number “Let the Sunshine In” is one of the film’s high points. So is the appearance of Sly and the Family Stone, doing “I Want to Take You Higher” and “Everyday People.” With a white drummer and a female trumpeter, that group, heartily embraced, represented something new.

My favorite moment in the film comes when Mavis Staples joins with Mahalia Jackson in singing “Take My Hand, Precious Lord,” Dr. King’s favorite gospel song. What these two dynamos express goes beyond elation. It’s more like transcendence. This time capsule of a movie is timeless.

Peter Rainer is the Monitor’s film critic. “Summer of Soul” (rated PG-13) opens in theaters and is available on Hulu on July 2.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

When to be humble about inflation forecasts

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

One thing is certain about America’s debate over whether harmful inflation is on the horizon in a hot economy: The agency in charge of managing inflation, the Federal Reserve, is very uncertain about what to do. And that may actually be a virtue.

In March, 11 of the top 18 officials in the U.S. central bank were predicting low inflation and thus saw no need to raise interest rates before 2024. By June that flipped: Thirteen of 18 saw a need to raise rates before 2024. Not only is the Fed divided, but its leaders are also in deep deliberation, listening for clues, alert to uncertainties, and willing to shift opinions. They perhaps know that two recent unpredicted shocks – the 2008 global financial crisis and the 2020-21 pandemic – have made economists engage in reflective self-criticism and be less prone to hubristic predictions. In the “dismal” profession of economics, a cautious bias has replaced a confidence bias.

The willingness to self-correct and listen for the deeper currents of change is long overdue. The greatest insights often come from the greatest humility.

When to be humble about inflation forecasts

One thing is certain about America’s debate over whether harmful inflation is on the horizon in a hot economy: The agency in charge of managing inflation, the Federal Reserve, is very uncertain about what to do. And that may actually be a virtue.

In March, 11 of the top 18 officials in the U.S. central bank were predicting low inflation and thus saw no need to raise interest rates before 2024. By June that flipped: Thirteen of 18 saw a need to raise rates before 2024. Not only is the Fed divided, but its leaders are also in deep deliberation, listening for clues, alert to uncertainties, and willing to shift opinions. They perhaps know that two recent unpredicted shocks – the 2008 global financial crisis and the 2020-21 pandemic – have made economists engage in reflective self-criticism and be less prone to hubristic predictions. In the “dismal” profession of economics, a cautious bias has replaced a confidence bias.

That point was made this week by three prominent experts during an Aspen Institute session and in a recent joint paper. Robert Rubin, a former treasury secretary; Peter Orszag, a former head of the Office of Management and Budget; and Joseph Stiglitz, a Nobel Prize-winning economist – who all differ in ideologies – argue that current economic debates should “be informed by copious amounts of humility, particularly given the role of impossible-to-predict events (including pandemics, wars, and [market] bubbles).”

They contend bad economic and fiscal projections in the past have made a case for humility. Policymakers can no longer hope that their “confidence would itself instill confidence,” as the paper stated. Last year, the United States experienced a rare service-sector downturn. Globalization may now be in reverse. Despite a recession in 2020, household savings went up while credit card debt declined. Uncertainty is pervasive, they say.

They do not argue for policymakers to do nothing. Instead, they warn that traditional top-down “anchors” in economic policies may no longer work. And the Fed’s internal debate over inflation and interest rates reflects this reality. “One of the arguments for humility is that economists have been very bad at forecasting,” said Mr. Stiglitz.

The three do propose a solution. They call it decluttering. Congress should set up “automatic stabilizers” for parts of the economy in which there is little policy disagreement and “we know what works,” such as tying jobless benefits to a recession or triggering road-building projects to boost income. “Stimulus measures, such as state and local aid, should be automatically tied to the state of the economy,” they write.

That would then free up politicians to engage in democratic deliberation over what is truly unusual and needs consensus building. “The uncertainties policymakers face are myriad and deep – not just about the course of interest rates but also about possible global macroeconomic shocks, rapid changes in the geopolitical environment, and climate change. We cannot even ascertain the probabilities of such events.”

True to form, the three admit they may be wrong. “Perhaps the world will turn out to be more certain,” they state. Yet the willingness to self-correct and listen for the deeper currents of change is long overdue. The greatest insights often come from the greatest humility.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Finding true freedom

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Larissa Snorek

It can seem that there are all kinds of things that would limit us – illness, age, history, for instance. But recognizing our true nature as God’s children brings healing and freedom from limitations.

Finding true freedom

As many countries open travel and business once again, some people are feeling liberated, while others are reluctant to emerge too quickly. But all of us can look beyond what is restricted or allowed and seek something more than just returning to bustling cafés and gridlocked traffic. True freedom is much greater.

The discoverer of Christian Science, Mary Baker Eddy, goes to the heart of true freedom when she says, “God’s being is infinity, freedom, harmony, and boundless bliss” (“Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” p. 481). God, Spirit, is the real source and essence of freedom – fearless and limitless Life. You and I are inseparable from God, and are inherently free because God, as Life, is so.

I’ve been a runner most of my life. I’ve also loved climbing mountains and flying down ski slopes at high speed. There’s definitely a sense of exhilaration that comes from pushing past physical limits. But we can never feel – or be – more free than when we become fully conscious for even a moment of divine Truth, God, as the whole of our life. This Truth destroys limiting beliefs about ourselves we’ve accepted as fact. These beliefs must change to allow healing to happen and to show us our innate spiritual freedom.

Freedom isn’t something we obtain, but something we reflect and can freely admit today because we are each God’s divine likeness. Accepting life as fundamentally mortal carries with it a persistent sense of being imprisoned, whereas spiritual thinking that begins with God, good, divine Life, always confers freedom. Healing is the result of knowing we are subject only to God, infinite Truth, Life, and Love. Then, limits begin to disappear and are replaced by the beauty and divine goodness of God’s creation as the reality of being, and we experience increased freedom and healing.

Christ Jesus, the greatest example of someone living a life of true freedom, unfettered by the confines of matter, promised those who followed his teachings, “You shall know the truth, and the truth shall make you free” (John 8:32, New King James Version). More than a freedom from something, Jesus taught the freedom to do or be something by accepting our real nature as a child of God, inseparable from God. Freedom is living and acting from the basis of our innate, spiritual identity, which is God-given and can never be taken from us.

Even when someone didn’t appear to be free, Jesus showed them that freedom was their divine right. One such man, who had been ill for 38 years and felt helpless, sat by the side of a special pool said to bring healing to the first one who touched it after an angel was believed to stir the water (see John 5:2-9). He was waiting for someone to bring him his freedom by putting him into the water. He believed health and liberty were possible but rare, and dependent on unique circumstances, whereas Jesus showed him that freedom was right at hand, universally available.

The more we understand and seek God, the more Truth dawns in consciousness and shows limitations to be false. The more we observe and pay attention to the thoughts that are guiding our actions, the more we can change them. The spiritual truth of what we are supersedes beliefs about what we are not. We are not our beliefs about ourselves – we are the clear-thinking, peaceful, compassionate, innovative, pure expressions of God, and include freedom and boundless bliss.

And so, we discover this as our beliefs change, and we find we can live as the full and completely free expression of Spirit, God.

Adapted from an editorial published in the July 5, 2021, issue of the Christian Science Sentinel.

Looking for more timely inspiration like this? Sign up for the free weekly newsletters for this column or the Christian Science Sentinel, a sister publication of the Monitor.

A message of love

Soaring silhouette

A look ahead

Thank you for joining us. We don’t publish a Daily on Monday, a federal holiday marking Independence Day in the U.S., but watch for a special email from us. We’ll provide a selection of our stories that explore different facets of liberty today.

Speaking of which, here’s a bonus read: our roundup of books on the American Revolution and its ongoing meaning.