- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- The case that could breach the wall between church and state

- How charging parents in a school shooting could change the conversation

- Can neighborliness fight off pandemic polarization? Vermont says yes.

- Asteroid blasting and moon dust mitigation: You can major in that

- Another year in the books: Best reads of 2021

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Finding the hidden gems among the stacks

April Austin

April Austin

Monitor readers are book lovers. From the time I became the books editor in 2019, I’ve been eager to seek out thought-provoking books that inform and inspire our readers.

Each December, a daunting task awaits: determining the best books of the year, which you’ll find in this issue. The list is the product of nearly 12 months of reviews, author Q&As, and insights, which, this year, involved 36 reviewers assessing almost 250 books; we published reviews of about 150 of those titles.

What drives those initial selections? Each month, as I sift through early reviews in trade magazines, I look for books that embody Monitor values such as courage, tenacity, authenticity, and deep humanity. Once I’ve narrowed my list to 20 or so candidates, I assign reviewers to assess the books based on those values.

Literature can be a great driver of empathy and understanding. I look for three-dimensional characters that demonstrate agency in their lives and a willingness to seek growth. I hope to identify authors who possess what Monitor Editor Mark Sappenfield calls “an unshakeable conviction that love and grace are accessible and active in every human condition.”

I also look for books by a diverse group of authors and for stories that bring readers into corners of the world and into lives they might not otherwise encounter. Such literature helps us understand where people are coming from and creates opportunities to discover commonalities with people who might seem quite different.

When you read our reviews, sign up for the free weekly books newsletter, or join our Books Beat Facebook group, you’re part of a community of Monitor readers seeking books that have the power to enlarge and enrich our lives. Thank you for being part of our community.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

The case that could breach the wall between church and state

What happens when what had been a bedrock principle changes? Carson v. Makin shows the Supreme Court’s evolution of thought in recent decades on the separation of church and state.

-

Chelsea Sheasley Staff writer

So much of Amy Carson’s life in rural Maine has centered around the small Evangelical school she attended nearly 30 years ago.

She met her husband, David, there when she was in eighth grade, and their daughter Olivia attended from kindergarten through high school. Their hometown of Glenburn doesn’t have a public high school.

In order to provide students with a free public education, as the state constitution requires, Maine offers families a taxpayer-funded tuition assistance program. But sectarian private schools like the Carsons’ alma mater are not approved.

On Wednesday, the Supreme Court will hear oral arguments in Carson v. Makin, in which the Carsons joined other families to sue the state’s Department of Education. They argue that by excluding religious schools, the state of Maine violated the United States Constitution, unfairly discriminating against religious parents.

The case is part of what has been a series of Supreme Court decisions over the past few decades that have, in general, permitted more and more public funds to flow to religious schools via voucher programs or even some forms of direct aid to religious institutions. Behind these cases, however, lurks a larger question about the nature of American pluralism in the modern era.

The case that could breach the wall between church and state

So much of Amy Carson’s life in rural Maine has centered around the small Evangelical school she attended nearly 30 years ago.

She met her husband, David, there when she was in eighth grade, and both of them had siblings there as well. Some family members used to teach at the conservative Christian school, and their daughter Olivia, a recent graduate, attended from kindergarten through high school.

“It’s a small school, it’s college prep education, it’s close-knit, so everybody knows everybody,” says Ms. Carson, who lives with her family in Glenburn, Maine, a town of about 4,500 residents in a district that doesn’t have a public high school. She says it’s always been important for her family to be part of a community that instills the beliefs and biblical worldview they share at home.

Like the Carsons, the families of nearly 5,000 of Maine’s 180,000 students live in school districts in which the state does not operate a public secondary school. In order to provide these students with a free public education, as the state constitution requires, Maine offers families a taxpayer-funded tuition assistance program, which allows them to send their children to a public school outside their district or an approved private school.

Olivia’s parents could have used the assistance to send her to one of eight high schools, three of which were private, Ms. Carson recalls. But their alma mater, Bangor Christian Schools, does not qualify for the tuition assistance program, since the state excludes “sectarian” schools that inculcate students with a particular faith tradition.

On Wednesday, the Supreme Court will hear oral arguments in their namesake case, Carson v. Makin, in which Ms. Carson and her husband joined other Maine families to sue the state’s Department of Education. They argue that by excluding religious schools like Bangor, the state of Maine violated the United States Constitution, unfairly discriminating against religious parents like them.

The case is part of what has been a series of Supreme Court decisions over the past few decades that have, in general, permitted more and more public funds to flow to religious schools via voucher programs or even some forms of direct aid to religious institutions.

“The really big-picture view is that there has been this evolution ... from the idea that the religion clauses, and particularly the establishment clause of the First Amendment, prevented government from giving direct financial assistance to sectarian religious entities,” says Jessie Hill, professor of law at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland.

“That was kind of a bedrock principle before, but it has slowly evolved toward an idea that not only is it permissible for direct financial aid to flow to these institutions, but it might even be required in some circumstances,” Professor Hill says.

Behind these cases, however, lurks a larger question about the nature of American pluralism in the modern era. For those who maintain traditional religious views of marriage and human sexuality, they believe their sincerely held religious beliefs should continue to be protected from certain nondiscrimination laws in order for them to express their faith freely.

At the same time, many religious institutions and people of faith have battled to be treated like any other group, able to participate fully in public benefit programs – like Maine’s tuition assistance program.

“At some level pluralism demands that we tolerate views that we don’t like. A lot of religions have views that I disagree with, and I’m able, I hope, to accept that,” says Nicole Stelle Garnett, professor of law at the University of Notre Dame in Indiana. “But should these religious schools, or religious entities more broadly, be permitted to hold views that are not popular? I’m a Catholic, so I’m sensitive to this, because certainly my church has long held views that were considered antithetical to American democracy.”

Indeed, the origins of so-called Blaine Amendments in many state constitutions were rooted in anti-Catholic bigotry, scholars point out, and designed to keep public funds away from the denomination’s growing network of schools, which often served the nation’s poor people.

From Everson v. Board of Education to today

In 1947, the Supreme Court articulated what was understood as a kind of bedrock principle, that “no tax in any amount, large or small, can be levied to support any religious activities or institutions, whatever they may be called, or whatever form they may adopt to teach or practice religion.” The case, Everson v. Board of Education, in some ways affirmed the Jeffersonian interpretation of the establishment clause as a “wall of separation” between church and state.

In a 5-to-4 decision in 2002, however, the nation’s high court declared in Zelman v. Simmons-Harris that an Ohio voucher program did not violate this principle because tax funds were not distributed to support a religious establishment, but the free choices of parents – a kind of constitutional circuit breaker.

“When you’re dealing with a program like [Maine’s] that provides aid to individuals and provides them with a private choice over where to use that aid, the Supreme Court has made it clear, this severs that link between church and state, and therefore a program like this one is unquestionably constitutional under the establishment clause, even if it includes religious options,” says Michael Bindas, senior attorney for the Institute for Justice and lead counsel for the Carson case before the Supreme Court Wednesday.

In 2004, however, the Supreme Court suggested that there was a difference between public funds directed toward schools with a religious “status” and programs with an explicit religious “use.” In Locke v. Davey, the high court upheld a state scholarship program in Washington that excluded those studying theology. In 2017, the Supreme Court in Trinity Lutheran v. Comer employed this use-versus-status distinction to declare that the state of Missouri violated the free exercise clause of the First Amendment when it used its Blaine Amendment to exclude a church that applied for a public grant to resurface its playground.

Mr. Bindas was also part of the legal team who argued for the plaintiffs in 2020’s Supreme Court decision in Espinoza v. Montana Department of Revenue, in which the Supreme Court said a state could not exclude religious families from educational choice programs that allowed for private options.

The Constitution “condemns discrimination against religious schools and the families whose children attend them,” Chief Justice John Roberts wrote for another 5-to-4 majority. “They are members of the community too, and their exclusion from [Montana’s] scholarship program here is odious to our Constitution and cannot stand. ... A State need not subsidize private education. But once a State decides to do so, it cannot disqualify some private schools solely because they are religious.”

In the Carson case, however, Mr. Bindas will tell the court that the status-use distinction is constitutionally irrelevant. “What we’re arguing in this case is that you can call it discrimination based on religious use if you want, or call it discrimination based on status,” he says. “But at the end of the day, it’s discrimination based on religion.”

A federal appeals court upheld Maine’s exclusion of sectarian schools, in many ways relying on the distinction between religious status and religious use. And the state of Maine argues that it is not impinging on the free exercise of religion by denying subsidies for a sectarian religious education.

“Religious schools can and do advance their own religion to the exclusion of all others, discriminate in both the teachers they employ and the students they admit, and teach religious views inimical to what is taught in public schools,” Aaron Frey, Maine’s attorney general, said in a public statement this year. “Parents are free to send their children to such schools if they choose, but not with public dollars.”

Ms. Carson says the exclusion of conservative Christian schools like Bangor, which has been so integral to the life of her family, hurts those who want to live their faith as freely as anyone else in Maine. They’ve known “families who were having a really hard time, or had to pull their kids when they got to high school, because ... they couldn’t justify anymore paying when the town would pay for it for them to go to a different school.”

What do states need to pay for?

In its brief, the state of Maine argues that the religious worldviews of the schools in question include policies that exclude LGBTQ students and employees, as well as those from other religions in many cases.

“We’re looking at potentially another wrecking ball to the wall of separation between church and state,” Jennifer Pizer, law and policy director for Lambda Legal, told Time magazine. “The fundamental notion that none of us should be required to pay for other people’s practice of religion is about as basic as it gets, and yet we’re seeing, in these education contexts, that notion flipped on its head.”

Indeed, a number of legal scholars believe there may be a host of implications for allowing public funds to subsidize sectarian schools as these cases continue to evolve.

“The end game may very well be that the government has to in fact fund private religious schools if it is also funding public schools,” says Professor Hill at Case Western Reserve University. “That principle is lurking in there, that private schools should be entitled to the same public money to the same extent as public schools.”

How charging parents in a school shooting could change the conversation

Preventing school shootings has always taken a village. But new attention is being put on the role parents in particular play in monitoring and being responsible for student actions.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

In a year that’s seen the most school shootings in at least two decades, the search for accountability and prevention is leading to parents.

A Michigan prosecutor quickly took legal action against the mother and father of a student gunman who is accused of killing four students last week. The parents were charged with multiple counts of involuntary manslaughter, in part for issues related to supervision and access to the gun. Their 15-year-old son is being charged as an adult with terrorism and multiple counts of first-degree murder.

The rarely used tactic has generated some optimism about holding parents responsible and spurring tougher gun storage laws. Yet it may remain an atypical approach, some experts say. Thwarting future school shootings depends on a range of efforts, researchers suggest, including providing more mental health support, limiting access to guns, and helping parents know what to watch for.

The focus on the Michigan couple “brings up the question of what are the responsibilities of parents in homes where they have guns,” says Matthew Mayer, an associate professor at Rutgers University. “We have to look at the larger issues here and say how do we help educate and change the behaviors of parents nationally so that kids can’t get to the guns if they are in the home.”

How charging parents in a school shooting could change the conversation

In the days since four students were killed and seven other people were injured in a mass shooting at Oxford High School in Michigan, there’s been no shortage of questions about whether the attack could have been prevented and whom to hold accountable: the parents? The school? Both?

Charging the parents of the accused student gunman – which a Michigan prosecutor did quickly – is a rarely used tactic that has generated some optimism about holding parents more accountable and spurring tougher gun storage laws. Yet it may remain atypical for mothers and fathers to be charged, some experts say, suggesting that the measure is also more reactive than preventive. Thwarting future school shootings depends on a range of efforts, researchers suggest, including providing more mental health support and limiting access to guns.

The decision to focus on the parents in this case “brings up the question of what are the responsibilities of parents in homes where they have guns,” says Matthew Mayer, an associate professor of educational psychology at Rutgers University in New Jersey who specializes in school violence prevention. He points to studies showing that 4.6 million to 5.4 million children live in homes with access to guns.

Michigan law does not require gun owners to lock their firearms, but possession of a gun by a minor is illegal, except for some instances of hunting with a license or under supervision of an adult. In the current case, the gun was apparently a gift that the father and son Ethan bought together four days before the shooting, according to prosecutors. The 15-year-old is being charged as an adult with terrorism and multiple counts of first-degree murder; the parents have been charged with multiple counts of involuntary manslaughter.

“We have to look at the larger issues here and say how do we help educate and change the behaviors of parents nationally so that kids can’t get to the guns if they are in the home,” Dr. Mayer says. “Part of it is education, but part of it is laws and regulations. It’s not going to happen just by force. You have to convince people that it’s an important thing to do.”

Even though school shootings are still relatively uncommon, there have been 34 so far in 2021, the worst year on record since at least 1999, according to data for K-12 schools analyzed by The Washington Post.

A separate Post analysis suggests that there’s little precedent for charging parents. Of 105 school shootings perpetrated by kids under age 18 between 1999 and 2018 where the source of the weapon was known, 80% of the weapons were from the shooter’s own home or the homes of relatives or friends, the Post found. Four adults were convicted during that time for not locking their guns.

A 2021 study by the National Threat Assessment Center, run by the U.S. Secret Service, of 67 potential school shooting attacks averted between 2006 and 2018 found that the majority had unimpeded access to firearms in their home. Seven of the potential attackers were able to access safely secured guns by methods including prying the safe open, finding the key, or being given access to the safe.

Even so, there is a push for more legislation. Moms Demand Action, a gun control advocacy group, says 23 states and Washington, D.C., have some form of child access prevention, or CAP, laws that require gun owners to safely store their firearms. The group is calling for more laws and better enforcement of CAP laws and extreme risk protection orders (ERPOs), where a firearm can temporarily be removed from at-risk individuals.

“If we know where school shooters get their guns from and know they’re exhibiting warning signs, that means we can stop school shootings before they happen. We have to stop kids from getting their hands on guns in the first place, and that starts with secure gun storage,” said Shannon Watts, founder of Moms Demand Action during a press call on Dec. 2.

The National Rifle Association did not respond to a request for comment on the role of parents in preventing school shootings.

April Zeoli, an associate professor in the school of criminal justice at Michigan State University, who studies ERPO orders, says they rapidly expanded in states after the 2018 shooting in Parkland, Florida, and are now found in 19 states and Washington, D.C. In forthcoming research on ERPO laws in six states, she says she’s seen examples of law enforcement using the judge-approved petition to temporarily remove all guns from homes where a potential school shooter lives.

“We do have tools to prevent this kind of thing from happening. These tools [ERPOs] aren’t in place in every state … but there are things that we can do so school shootings don’t have to be inevitable,” Dr. Zeoli says.

More parent involvement

A more defined role for parents is emerging in public conversations about prevention. After multiple shooting incidents at or near high schools in Aurora, Colorado, the police chief specifically asked for help. “I need the parents to get involved. I need you checking phones. I need you checking rooms. I need you checking cars. And make sure that they’re taking these guns away from these kids,” said Police Chief Vanessa Wilson at a Nov. 19 press conference after three students were shot in a school parking lot.

Parents need education about how to recognize warning signs that mass shooters often show, such as visiting a website that glorifies past school shooters, an obsession with firearms, or suicidal tendencies, says Ron Avi Astor, a professor of social welfare who studies school violence prevention at the University of California, Los Angeles. And once parents have concerns, he says, there need to be clearer messages about where they can turn for help.

In the Michigan case, what the parents, James and Jennifer Crumbley, knew ahead of time may also come into play. Prosecutors say that Ms. Crumbley texted her son “LOL, I’m not mad at you. You have to learn not to get caught,” after a teacher found him searching online for ammunition the day before the attack. Hours before the shooting, the parents came to school for a meeting to review a violent picture that a teacher saw Ethan drawing in class, according to the school district superintendent. The parents reportedly refused to bring their son home, as school officials desired, and did not disclose that he had access to a firearm.

“I have tremendous compassion and empathy for parents who have children who are struggling and at risk for whatever reason. And I am, by no means, saying that an active shooter situation should always result in a criminal prosecution against parents. But the facts of this case are so egregious,” Oakland County Prosecutor Karen McDonald said in a press conference on Dec. 3, when she announced four charges of involuntary manslaughter against each of the parents. The charges carry a maximum 15-year prison sentence.

Whether or not the charges will succeed depends on whether prosecutors can convince a jury that the parents were “grossly negligent” in the way in which they maintained their gun, and what their state of mind was regarding knowledge of their son’s possible intentions to use the gun, says Larry Dubin, emeritus professor of law at the University of Detroit Mercy. “I think all of those facts, if you could think of them in the most incriminating way, could theoretically establish the crime of involuntary manslaughter,” says Mr. Dubin.

A menu for prevention

Strong gun laws are important, but aren’t the only factor for deterring violence, says Dr. Mayer, from Rutgers.

“A determined perpetrator of violence isn’t going to be stopped, and we have to think more of preventive measures and not reactive measures, and that’s something where we’ve had difficulty coming together on,” says Dr. Mayer, who notes that he doesn’t support excessive security, where teachers are armed or schools feel like fortresses.

Some researchers think preventing future school shootings should be seen as a broader public health effort. Dr. Astor and Dr. Mayer helped lead a group of scholars to publish a holistic public health plan in 2018 to prevent gun violence at schools. The document is endorsed by more than 4,000 individuals and hundreds of national organizations, and includes efforts to prevent violence by building stronger, healthier school communities and families through things like bullying prevention and threat assessments.

“What I like about that approach is it doesn’t get us stuck in this Second Amendment rights issue that everybody seems to gravitate to almost automatically, of ‘there’s nothing you can do’ or ‘eliminate all guns,’” says Dr. Astor. “There’s a lot you can do in between.”

Can neighborliness fight off pandemic polarization? Vermont says yes.

How do you maintain a sense of community despite differing views about the pandemic? Vermont’s long-standing culture of neighborliness may offer lessons for the rest of the nation.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

-

By Gareth Henderson Correspondent

From expanding statewide food distribution to making vaccines readily accessible, Vermonters have generally been unified in their approach to the pandemic, notes Mike Smith, the state’s secretary of human services.

“You’re going to have disagreements, and that’s fine, but in terms of the fundamentals of responding to this pandemic, Vermonters have really stuck together,” he says.

One sign of that unity is the state’s high vaccination rate, supported by specific outreach to Black and Indigenous people and other minorities. In addition, as of Dec. 6, Vermont had one of the nation’s lowest COVID-19 death rates.

The health of businesses has been a top concern too. In Woodstock, the Yankee Bookshop credits local support with the store’s survival. And while some closures have occurred, Vermont showed a 4.4% increase in establishments the first quarter of 2021 over the same quarter in 2020.

Though no state has entirely escaped conflict over how best to approach the pandemic, Vermont’s largely cohesive response may be an extension of its deeply rooted neighborly culture.

“You might not know the name of every one of your neighbors,” says Tom Donahue, CEO of a community action group in Rutland, “but you’re always looking out for each other.”

Can neighborliness fight off pandemic polarization? Vermont says yes.

If you’re heading home and get stuck in a snowbank in Vermont, chances are a neighbor with a truck will stop and help. And if you live nearby, you might be helping your neighbor out of a similar jam some day.

In the Green Mountain State, that’s not just an act of kindness – it’s the way Vermonters live.

“There’s a sense that patriotism isn’t just about national interest. It’s also about how you contribute to community and place,” says Paul Costello, former head of the Vermont Council on Rural Development.

For the past two decades, he was the driving force behind dozens of “community visits,” local discussions focused on turning community goals into action – examples include a new senior housing project, a youth center, and downtown revitalization efforts.

Some believe that focus on community has been the engine behind the state’s largely successful pandemic response. From expanding statewide food distribution to making vaccines accessible, Vermonters have generally been unified, notes Mike Smith, the state’s secretary of human services.

“You’re going to have disagreements, and that’s fine, but in terms of the fundamentals of responding to this pandemic, Vermonters have really stuck together,” he says.

That stands in stark contrast with other states, where the pandemic has further frayed the fabric of community that defines people as neighbors and fellow citizens, regardless of how they vote.

One sign of Vermont’s unity is the state’s high vaccination rate, supported by specific outreach to Black and Indigenous people and other minorities, as well as groups requiring special consideration, such as homebound individuals.

As of Dec. 7, 94.2% of Vermonters 12 years of age and older had received at least one dose of the COVID-19 vaccine, compared with 81.5% nationally. And 83% of Vermont residents in that age range had been fully vaccinated; that’s 13 percentage points higher than the national statistic according to state and federal data. In addition, as of Dec. 6, Vermont had one of the lowest pandemic death rates, at 1.4 per 100,000 residents over the prior seven days, 10 times lower than Wyoming’s death rate of 14, the highest in the nation on Dec. 6.

Like much of New England, Vermont saw a spike in cases in November when the weather turned colder. But despite the surge, the state still ranks among the best for COVID-19 outcomes.

Vermont’s high vaccination rates remind Mr. Smith of the all-hands-on-deck community spirit that drove rebuilding efforts after the disastrous flooding from tropical storm Irene in 2011. And, he adds, people who relocated to the state during the pandemic became part of this community culture.

“When you come to a community, you’re really embraced. ... People want to make sure that you’re taken care of in terms of your well-being,” Mr. Smith says.

Keeping businesses afloat

The health of businesses has been a top concern too. While some closures have occurred, Vermont showed a 1.6% increase in establishments in 2020 over 2019 and a 4.4% rise in the first quarter of 2021 over the same quarter in 2020, according to the Vermont Department of Labor. Preliminary data for the second quarter of this year over the same quarter last year shows a 6.1% increase.

At least some of that progress resulted from Vermonters rallying around their neighbors. Here in Woodstock, a small shire town of about 3,000 people, the Yankee Bookshop credits local support with the store’s survival. Co-owners Kari Meutsch and Kristian Preylowski saw a flood of online orders from people near and far.

“It allowed us to continue to keep the store functioning through those couple of months when we were closed,” Ms. Meutsch says. Some customers even bought gift cards just to help the store. One person asked for his gift card to be used to get books to then-shuttered senior centers and assisted living facilities.

The bookshop re-opened to in-person traffic in June 2020, and Mr. Preylowski senses an increased appreciation for buying local, not just at his shop but across all sectors.

“It means so much more to people now,” he says. And that includes newcomers.

“It’s Vermont culture for sure, but it’s also adopted by the people that joined us,” Ms. Meutsch adds.

Setting the tone

When it comes to states led by a Republican governor, Vermont is atypical. Republican governors in Texas, Missouri, Florida, and Georgia, for example, quickly came out against President Joe Biden’s vaccine mandates for federal employees and contractors, certain health care workers, and all companies employing 100 or more. However, back in the Green Mountains, Gov. Phil Scott was the rare Republican head of state to support it. That fits a pattern for the Scott administration, which has been supportive of pandemic precautions.

The governor has also consistently urged his fellow Vermonters to respect their neighbors who disagree with them.

“Let’s not make the news with screaming matches caught on video,” Governor Scott urged during a press conference earlier this year. “Let’s do things the Vermont way, by being role models and leading by example.”

A few small protests against pandemic restrictions have occurred in Vermont, with one on the Statehouse steps in Montpelier in May drawing between 50 to 100 people. But that opposition failed to gain widespread momentum, and many restrictions, including a mask mandate that Vermonters largely supported, were lifted in June after the state’s vaccination rate passed 80%. Thus far, no statewide mask mandate has been reimposed, though the Legislature did, in a special session on Nov. 22, pass a law giving municipalities the option to enact their own mask mandate if they so choose. Under the bill, that authority for municipalities expires on April 30, 2022.

Maintaining a culture

Though no state has entirely escaped conflict over how best to approach the pandemic, Vermont’s largely cohesive response may be an extension of its deeply rooted neighborly culture. Steve Perkins, executive director of the Vermont Historical Society, says the state’s difficult mountainous terrain has compelled communities to “live as their own units” for most of Vermont’s history.

“This idea of unity and helping one’s neighbor just became a part of life,” Mr. Perkins says. “You could not rely on help from outside your community; it would have to come from the community.”

Anson Tebbetts, Vermont’s agriculture secretary, can attest to that. He remembers the community coming to his family’s rescue more than once while he was growing up in Cabot.

“If we were facing a three- or four-day power outage, the neighbors would bring their generator and they’d help us milk the cows and clean the barn,” he says.

Maintaining a community-oriented culture depends on that kind of neighborly assistance, says Tom Donahue, CEO of BROC Community Action, which is based in Rutland, where Mr. Donahue grew up. And 2020 was full of examples of it, he notes, including an annual charity event that raised three times the money it usually does to support low-income families.

“You might not know the name of every one of your neighbors, but you’re always looking out for each other,” he says.

Asteroid blasting and moon dust mitigation: You can major in that

One Colorado college helps rehearse for a reality in the next frontier: space mining, and the critical questions of ethics and sustainability it raises.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 8 Min. )

Drawing on terrestrial lessons humanity dares not repeat – pillaged civilizations, environmental ruin – the Colorado School of Mines is rehearsing for a reality in the next frontier: space mining. Unlike settlers of old who stampeded this state with gold pans and picks, Mines students in a unique new academic concentration are using far-out foresight to research how humans should harness resources in space.

“If we’re going to be a space-faring society in the future, it needs to be worked on,” says Jerry Sanders, at NASA’s Space Technology Mission Directorate. Leveraging space resources – from extracting Martian oxygen to recycling space junk for construction – is critical to “enhance and sustain” human exploration on the moon, he says.

Mines offers advanced degrees and an undergraduate minor in the multidisciplinary field of space resources. Students in the program – including an aspiring asteroid-blaster, moon-dust mitigators, and an entrepreneur with a NASA contract already in hand – all want careers in sustaining life in the obsidian expanse.

“It’s a unique moment in history to do it right,” says Angel Abbud-Madrid, director of the public research university’s Center for Space Resources.

Asteroid blasting and moon dust mitigation: You can major in that

Angel Abbud-Madrid embraced the space mania of the ’60s – he drank it down with Tang. At age 8, he watched the American moonwalk from his living room in Mexico, relieved that aliens didn’t intervene.

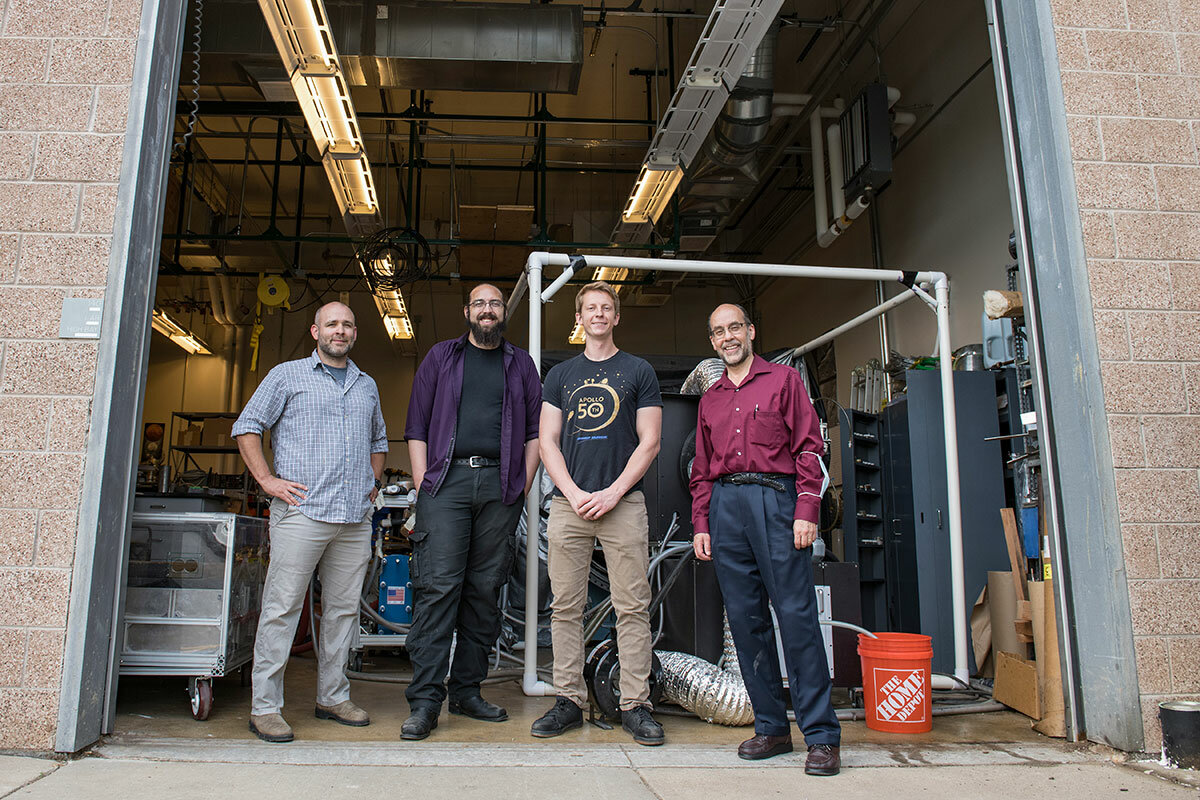

Through horn-rimmed glasses, Dr. Abbud-Madrid is still looking up. So are his students at the Colorado School of Mines – including an aspiring asteroid-blaster, moon-dust mitigators, and an entrepreneur with a NASA contract already in hand. All want careers in sustaining life in the obsidian expanse.

“It’s a unique moment in history to do it right,” says Dr. Abbud-Madrid, director of the Center for Space Resources.

Living off the land in space requires dreamers on Earth. Drawing on terrestrial lessons it dares not repeat – pillaged civilizations, environmental ruin – this Colorado public research university is rehearsing for a reality in the next frontier. Unlike settlers of old who stampeded this state with gold pans and picks, Mines students use far-out foresight: How should humans harness resources in space?

“If we’re going to be a space-faring society in the future, it needs to be worked on,” says Jerry Sanders of the NASA Space Technology Mission Directorate.

Doing this right, says Dr. Abbud-Madrid and students at Mines, involves calculating a range of concerns – from logistical to ethical – ahead of a galactic gold rush.

Space-age “orediggers”

Swaddled by the foothills of the Rockies, the city of Golden was founded in 1859 and named after a miner of the same surname. A decade after California’s gold rush began, Colorado’s brought more settlers scrambling West, hastening Indigenous displacement.

Established in the 1870s, Mines is known for engineering and other STEM degrees. NASA reports providing $32 million in grants and cooperative agreements over the past two decades to the school, whose 7,100 students are nicknamed “orediggers.”

Several U.S. colleges offer space-related studies (nearby University of Colorado Boulder is known for launching the careers of several astronauts). Yet Mines, say experts interviewed about it, is believed to be the first to offer advanced degrees in the multidisciplinary field of space resources.

Given the institution’s reputation for mining and operations research, its “focus in space resources sort of is logical,” says Scott Pace, director of the George Washington University Space Policy Institute. While the field is still small, “they’re it, at the moment.”

Courses began in 2017 with an online program the following year. Most of the 128 graduate students, from five continents, study virtually. A new space-mining minor for undergrads began this fall.

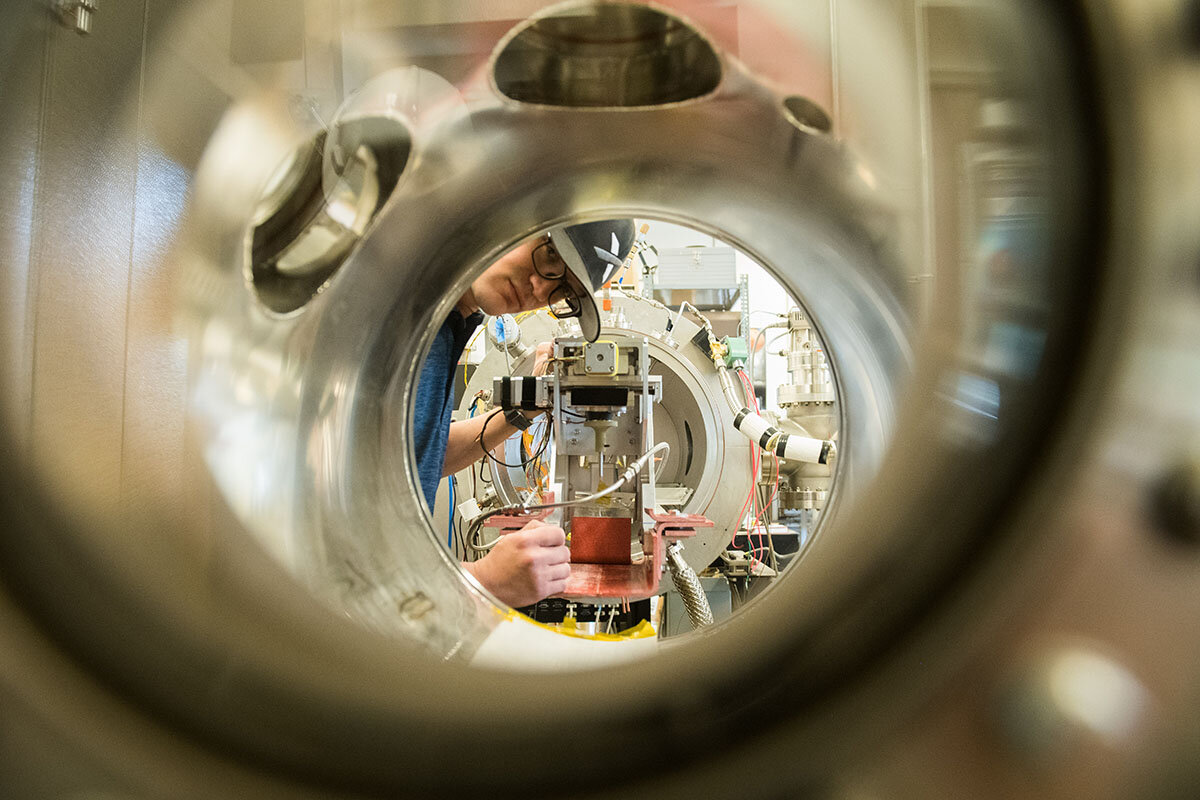

Tim Broslav is one of Golden’s postmodern pioneers. The Ph.D. student is part of a team figuring out how – in layperson’s terms – to blast water out of asteroids, those ancient space rocks that typically orbit the sun.

At the university lab, a lightbulb (substitute for solar light) illuminates a chamber holding a foot-long chunk of a rocklike homemade asteroid. Ideally, the heat from concentrated light stresses the asteroid surface to the point of breaking, producing water or other gases. Such “volatiles” could eventually be turned into rocket fuel or drinking water.

A complex project, yes. But at its core is a search for sustainability: It’s costly to schlep staples like water and fuel beyond Earth’s atmosphere; so why not get them in space?

“Space is going to push us to be even more resourceful,” says an upbeat Dr. Abbud-Madrid on an August tour of school facilities.

Space resources can be material or intangible. Think metals, minerals, ice. But also solar power, vacuum, distance. The collection, extraction, and use of resources in space is a concept called in-situ resource utilization, or ISRU.

“What we want to do is exactly what we have done on Earth for centuries,” he says. “We also have had hundreds of years to learn what not to do. I mean here, we hurt entire civilizations just by going after resources.”

From rampant deforestation to rivers running orange with toxic runoff from mines, history is likely to weigh on the consciences of ISRU advocates. Because many of their aims are still theoretical, they have time to troubleshoot potential harm.

During mining activities more than a century ago, “there was not a recognition that people would be living in those locations 100 years later,” says Jeff Graves, director of the Inactive Mine Reclamation Program at the Colorado Division of Reclamation, Mining and Safety and a Mines graduate.

He’s never seen “Star Trek”

Dr. Abbud-Madrid stoops to the pavement outside the lab and scoops up a palmful of the moon. The chalk-white “lunar” dust is actually a substitute from Greenland. It’s part of what lines a lunar test bed nearby, mimicking the moon’s abrasive terrain.

The wheels of a rover prototype have traversed that simulated soil, practice for a 2022 debut on the moon. The Mobile Autonomous Prospecting Platform (MAPP) lunar rover – a small, robotic prospector – belongs to the Golden startup Lunar Outpost, whose chief executive officer Justin Cyrus is pursuing a space-resources Ph.D. at Mines.

His company, one of four NASA asked to collect lunar materials on its behalf on the moon in the near future, scored a 10-cent check from the space agency this summer – a tenth of its $1 contract. The collaboration will mark the first transfer of space-resource ownership from private companies to the U.S. government – an important precedent while regulatory frameworks mature.

Leveraging space resources – from extracting Martian oxygen to recycling space junk for construction – is critical to “enhance and sustain” human exploration on the moon, says Mr. Sanders, system capability lead for ISRU at NASA. The agency’s Artemis program aims to land the first woman as well as the first person of color on the pearly satellite, and learn lessons there that can be applied to Mars.

NASA also seeks to support the space economy while enriching innovation back on Earth, he adds. For instance, how might extracting resources in space advance safety and efficiency for mining on Earth?

Dr. Abbud-Madrid, trained as a mechanical and electrical engineer, worked at a gold and silver mine after college. In the U.S. for his graduate career, he began to study how combustion works in microgravity. That led him to research at Mines, where he helped develop fire extinguishers that work on the International Space Station in low-Earth orbit. NASA honored him in 2004 for his contributions to space flight.

Despite his out-of-this world pursuits, Dr. Abbud-Madrid says he prefers to read current research tethered to reality, otherwise history books. He’s been reading about a Spanish queen who greenlighted an exploration in 1492 – and chewing on Christopher Columbus’ current legacy as a villain.

The professor says he’s not typically attracted to sci-fi, their plots “too far away.” Voice lowered in an empty lecture hall in August, he shares a secret: “I have never seen a ‘Star Trek’ episode.”

Ethics first, launch later

As Ben Thrift reaches gloved hands into a box filled with liquid nitrogen, icy vapor rises to tickle his beard. At the lab, he’s freezing a sample of icy regolith simulant: “fake moon dirt with ice in it,” he translates later.

His graduate research is helping develop a probing instrument meant for the moon, part of NASA’s Commercial Lunar Payload Services that supports the Artemis program. The penetrometer – a space version of a terrestrial engineering tool – is slated for a 2023 uncrewed mission to the lunar south pole, a region dimpled with icy craters.

Are there negative side effects to excavating in space? At least there isn’t lunar life – yet discovered – to bother, says Curtis Purrington, another Ph.D. student nearby. Still, he’s thinking through how to keep his activities from contaminating areas miles away. That could interfere with the research of others.

“We’re trying to address the ethical questions before we even show up,” Mr. Purrington says. “Hopefully before we ever break ground, we have really good, solid environmental laws already in place.”

The former F-16 crew chief has dreamed of space mining for over a decade. “And then when you talk to other people, they’re like, ‘OK, nerd.’”

When he began studying at Mines in 2018, he says, “Suddenly it was like, Oh my God. I found my people.”

Asked whether he sees himself working in space, Mr. Purrington says he’d prefer robots go first, as expected. After all, “humans are high-maintenance.”

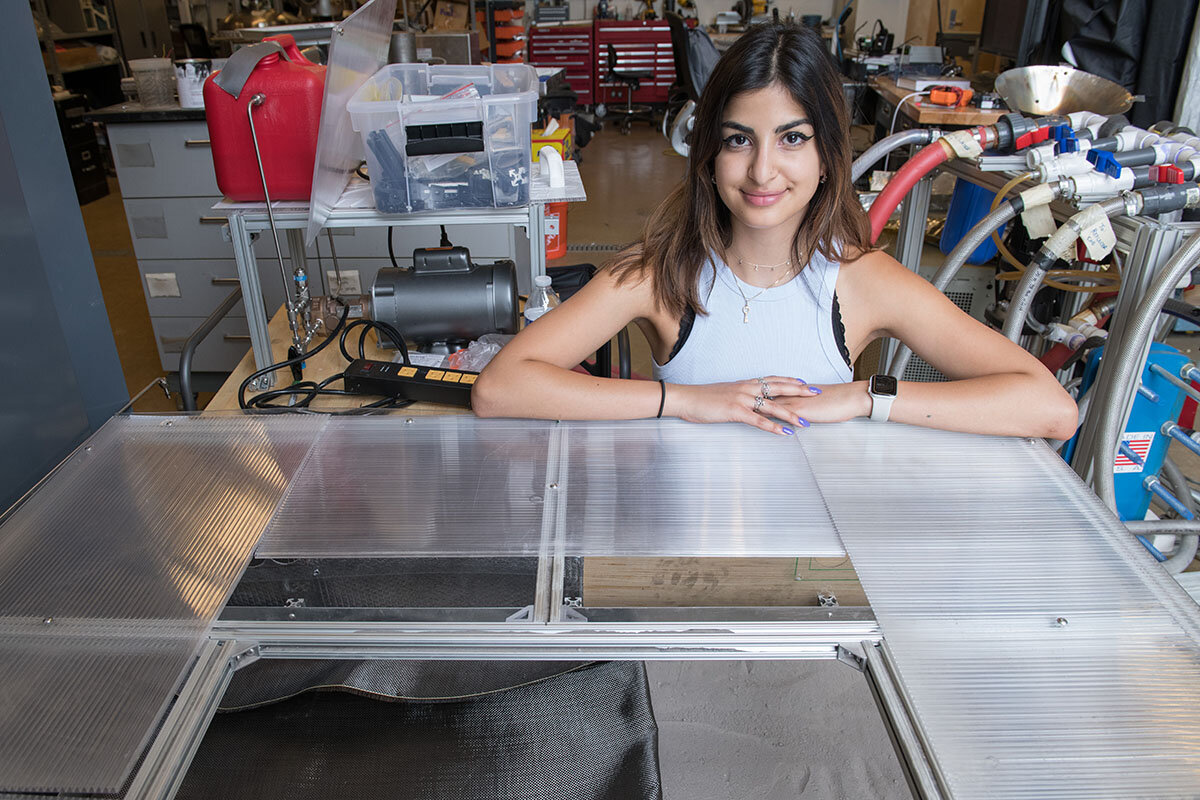

Engineering physics sophomore Parmida Mahdavi has a different take, tied to one of her biggest professional goals: solving space pollution.

“I want to be able to mitigate that from Earth,” says Ms. Mahdavi, who’s especially concerned about debris from combustions or collisions between celestial bodies and human-made machines. She interned with a Mines team on a NASA challenge focused on moon-dust mitigation. Mines, one of seven finalist teams, was honored for “best collaboration and systems engineering” in November. (Washington State University scored the top honor.)

“Once I can help my own planet as much as I can, then maybe I can travel somewhere else,” she says. “But you’ve got to fix your own home before you move houses.”

Not just a dream anymore

The lecture hall is packed for the first fall class of “Introduction to Space Exploration & Resources.” The commander, Dr. Abbud-Madrid, prompts self-reflection from his crew.

Dreamers, thinkers, and doers have all helped advance space innovation, he says, pacing at the front. “That doesn’t necessarily mean that you belong to only one category.”

Sitting back after class wearing a baseball cap backward, Haydn Sandstrom is fired up. Sci-fi video games and “2001: A Space Odyssey” inspired the mining engineering student’s otherworldly interests. Tonight, the possibility of a space gig has leaped light-years closer to reality.

“It’s not just a dream anymore,” says the junior interested in the space-mining minor.

Though he values teaching, Dr. Abbud-Madrid admits that staking claims in a new field keeps him up some nights. He doubts he’ll journey beyond Earth in his lifetime, but his ideas already have. Those fire extinguishers he helped design are still aboard the International Space Station.

“It is protecting the life of the astronauts, and that’s an amazing feeling,” he says outside the lab. As his arm extends toward the sky, he peers past his hand. Slowly, he traces an imagined orbit some 250 miles above.

Books

Another year in the books: Best reads of 2021

A good book doesn’t leave readers where it found them. Our favorites for 2021 include stories that move readers to walk in others’ shoes, honor challenges overcome, and feel the redemptive power of friendship.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

-

By Monitor reviewers

The panorama of human struggle and persistence is reflected in the wide-ranging titles that Monitor reviewers picked as the top books of the year. The stories tell of people who challenged racial injustice and hatred, sought solace in a time of grief, and made important discoveries about the natural world.

Among the notable lives featured in biographies on our list are tennis icon Billie Jean King and the 20th century’s most celebrated artist, Pablo Picasso.

Another year in the books: Best reads of 2021

“Reading is a discount ticket to everywhere,” wrote former Chicago Tribune columnist Mary Schmich in 1998. This is especially true of our reviewers’ choices for best books of the year. Whether set in far-off lands, or next door, these fiction and nonfiction titles stood out for their humanity and inclusiveness, and for the quality of the writing.

Fiction

Things We Lost to the Water

by Eric Nguyen

This debut novel spans three decades in the lives of a Vietnamese immigrant family that escapes war and communism to settle in New Orleans without the father – who has disappeared. Eric Nguyen exquisitely captures the nostalgia of childhood, the problems facing refugees, and the search for healing when secrets rock the soul.

Libertie

by Kaitlyn Greenidge

“Libertie” follows a Black girl born free in the Reconstruction era. Her mother is a doctor who wants nothing more than for Libertie to follow in her footsteps, but Libertie has different ideas of what freedom – for herself and for her people – truly looks like.

Klara and the Sun

by Kazuo Ishiguro

In his first novel since winning the Nobel Prize in 2017, Kazuo Ishiguro explores questions about what makes humans irreplaceable. This parable about a society in which science has been taken to ethically questionable levels is, thanks to its narrator – a kind, smart, sympathetic, solar-powered Artificial Friend – a surprisingly warm morality tale about love, hope, and empathy that subverts our expectations about dystopian fiction.

Emily’s House

by Amy Belding Brown

Irish immigrant Margaret Maher works as the maid in the family home of poet Emily Dickinson, cleaning, cooking, and defending her mistress from prying eyes. Margaret’s Tipperary-tinged voice brings this captivating novel to life; it’s a perspective rife with honesty, humor, and clever observations. Upon discovering Emily’s verses, Margaret breathes, “Like sparks they were – tiny scraps of light.”

My Monticello

by Jocelyn Nicole Johnson

Jocelyn Nicole Johnson’s short-story collection aims its powerful beam on history’s proximity, racial trauma, and community survival. The title story follows a group of residents fleeing a white supremacist siege of their Charlottesville, Virginia, neighborhood. Led by Sally Hemings’ descendant Da’Naisha, the group escapes to Thomas Jefferson’s well-preserved manse.

The Phone Booth at the Edge of the World

by Laura Imai Messina

In a coastal garden in northeast Japan sits the Wind Phone, which offers visitors a place of grace for their sorrow. This quiet novel follows grieving Yui and Takeshi as they form a friendship of shared experience – and navigate the trickier shoals of a deeper relationship – in lyrical, unrushed prose.

The Elephant of Belfast

by S. Kirk Walsh

A young zookeeper caring for a motherless elephant plumbs the depths of love and loyalty in a spellbinding novel set in Belfast, Northern Ireland, in World War II. S. Kirk Walsh’s account was inspired by the true story of the “elephant angel” of the Belfast Zoo, and she provides a deeply researched backdrop for complex characters.

Yellow Wife

by Sadeqa Johnson

Sadeqa Johnson’s novel is a layered look at the journey of Pheby Brown, a multiracial woman born into slavery and, ironically, privilege. Johnson probes deeply into the roots of color, class, and gender in the 1800s. The book strips bare what it means to struggle to survive as an “owned” woman.

Bewilderment

by Richard Powers

Astrobiologist Theo Byrne is raising his troubled 9-year-old son after the death of his wife. While the genre-defying novel explores such issues as the expanding cosmos and our endangered planet, at the center of this heartbreaking but beautifully written story is the bond between a father and son. (Readers may wish to know about a disturbing plot twist.)

How Beautiful We Were

by Imbolo Mbue

Imbolo Mbue, a Cameroonian American author, tells a timely story about the people of Kosawa, a fictional African village, who struggle with the environmental devastation caused by an American oil company. She focuses on Thula, a young woman who emerges as a revolutionary when legal remedies fail and the villagers discover the power of taking a stand for what is right.

The Sentence

by Louise Erdrich

Fresh from her Pulitzer Prize win for “The Night Watchman,” Louise Erdrich offers an engaging, highly readable story that takes place in her real-life Minneapolis bookstore. Through her main character, Tookie, Erdrich traces local events from the past 18 months, seeking understanding about the murder of George Floyd, racial tensions, and the pandemic. The book is imbued with humor and a sense of urgency.

Nonfiction

American Baby

by Gabrielle Glaser

Gabrielle Glaser tells the heartbreaking story of Margaret Erle, an unwed teen coerced into surrendering her infant son to an adoption agency in 1961. The empathetic account alternates between Margaret and her son David, up through their poignant reunion, while also illuminating the disturbing history of adoption in postwar America.

On Juneteenth

by Annette Gordon-Reed

Pulitzer Prize winner Annette Gordon-Reed renders a perfectly quilted work of history seen through the eyes of an African American family in Texas. It follows the seldom-shared stories of descendants of enslaved Black people from the 1820s to their emancipation in Galveston on June 19, 1865.

Finding the Mother Tree

by Suzanne Simard

Suzanne Simard is a leading forest ecologist and a pioneer in the field of plant communication. She writes that trees are complicated, interdependent social organisms connected to one another through underground networks. This book is not just about the science, but about a deeply personal quest to understand one of the most dominant classes of species on Earth.

Fox and I

by Catherine Raven

In this thoughtful memoir, Catherine Raven finds herself out of sync with the world around her and retreats to a patch of property in rural Montana, where her job is online and her neighbors are a comfortable distance away. All neighbors, that is, except one: To Raven’s surprise, a wild fox begins visiting her regularly, and over time the two develop an unusual and touching friendship.

Plunder

by Menachem Kaiser

A master storyteller embarks on a journey to learn about his grandfather and to reclaim an apartment building that was stolen during the Holocaust. The odyssey is fascinating and thought-provoking.

How the Word Is Passed

by Clint Smith

In his debut work of nonfiction, Clint Smith embarks on a very personal tour of some key flashpoints in the history of American racism, from Louisiana’s Angola prison to Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello, which is now a bustling tourist attraction. The result is a reckoning both brilliant and unnerving.

Somebody’s Daughter

by Ashley C. Ford

Ashley C. Ford’s father was in prison during her childhood, and her memoir focuses on the twin pains of his absence and of her difficult mother’s presence. With deep empathy, Ford brings readers through her experiences growing up Black in the Midwest. From vulnerable child to independent adult, she shows the value of compassion.

All In

by Billie Jean King

The tennis champion writes about her life with self-awareness and humility, while not underplaying her role as a trailblazer for women’s rights. She gently criticizes her younger self for feeling a need to hide her sexual identity to safeguard her career, and touches on the toll that secret exacted.

Pastoral Song

by James Rebanks

English sheep farmer and writer James Rebanks offers a sustainable method for raising animals, preserving habitat, caring for the environment, and nurturing small farmers all at the same time.

A Life of Picasso

by John Richardson

The fourth volume of John Richardson’s “Life of Picasso” biography tracks the great artist through Paris in the 1930s and early ’40s. Clear and compelling, it carefully and fairly examines his life and art.

Disruption

by Aki J. Peritz

In the summer of 2006, the British security services, with the assistance of the CIA, foiled what would have been the most devastating terrorist attack since 9/11: an al-Qaida plot to detonate bombs on seven transatlantic commercial flights, which would have resulted in over 3,000 deaths. “Disruption” is Peritz’s meticulous, fascinating history of this plot, from the radicalization of the perpetrators to their sentencing in a British courtroom.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

An urgent need for relief puts a spotlight on women

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

In a little-noticed triumph last month, the United Nations decided to “graduate” Bangladesh from a list of “least developed” nations. The country’s progress on its economy and in disaster prevention means it will need less assistance. One example: Bangladesh has reduced deaths from cyclones by more than a hundredfold over the past half-century even though it is now one of the most vulnerable countries to climate change.

Lessons from “graduating” countries like Bangladesh are more important than ever because of the U.N. projection for humanitarian needs next year. In 2022, an estimated 274 million people will need urgent help, or a 17% rise from this year and a doubling in the last four years. In most of these crises, women and girls suffer the most as preexisting gender inequalities are heightened.

Which brings us back to Bangladesh as an example for success. One reason for its ability to deal with cyclones is its buildup of a preparedness program with 76,000 volunteers who send out warnings of weather disasters and help people evacuate. Half of them are women, which has greatly reduced the number of women killed in cyclones.

An urgent need for relief puts a spotlight on women

In a little-noticed triumph last month, the United Nations decided to “graduate” Bangladesh from a list of “least developed” nations in five years. The country’s progress on its economy and in disaster prevention means it will need less assistance. One example: Bangladesh has reduced deaths from cyclones by more than a hundredfold over the past half-century even though it is now one of the most vulnerable countries to flooding from climate change.

Lessons from “graduating” countries like Bangladesh are more important than ever because of the U.N. projection for humanitarian needs next year. In 2022, an estimated 274 million people will need urgent help, or a 17% rise from this year and a doubling in the last four years. If all those people were in one place, it would be the fourth most populous country.

The U.N. also says famine looms for 45 million people in 43 countries. It is asking for $41 billion in total humanitarian donations.

The main causes of this global need are violent conflicts, the pandemic, and weather disasters. The affected countries range from Ethiopia to Afghanistan to Myanmar. In most of these crises, says U.N. Undersecretary-General for Humanitarian Affairs Martin Griffiths, “women and girls suffer the most as preexisting gender inequalities and protection risks are heightened.” More than two-thirds of people facing chronic hunger are female.

The world must “put the needs of women and girls central ... to the way we go about our business,” says Mr. Griffiths.

The U.N. and many others involved in humanitarian aid have shifted their focus to gender equality. One reason is that women are often the solution during aid emergencies.

“When disaster strikes or violence breaks out and communities face intense pressure to find safe harbor,” says USAID Administrator Samantha Power, “it is most often women who lead efforts to identify those most in need, and women who direct resources most effectively.”

Which brings us back to Bangladesh as an example for success. One reason for its ability to deal with cyclones is its buildup of a preparedness program with 76,000 volunteers – half of whom are women – who send out warnings of weather disasters and help people evacuate.

“Volunteer gender parity – which has been in place since 2020 – has helped increase the safety of shelters for women,” states a report by the New Humanitarian news site. Also, shelters now have segregated spaces for men and women as well as spaces for farm animals (which encourages people to evacuate). The number of shelters has increased from 44 in 1970 to more than 14,000 today. During that same period, the ratio of female-to-male deaths from cyclones has declined from 14-to-1 to 1-to-1.

As humanitarian needs are forecast to rise next year, “The world is coming together to find solutions to these multiple crises,” says U.N. Secretary‑General António Guterres.

Or as Purnima Sadhu, a 16-year-old Bangladeshi student told the New Humanitarian:

“Our parents did not learn about disasters when they were young, but we do. Climate change will bring bigger disasters in the future, but we know we can prepare for them. We are not afraid.”

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Thank you for listening

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 2 Min. )

-

By Bobby Lewis

Wherever we may be, we can listen for divine inspiration that guides us to health, harmony, and safety.

Thank you for listening

When I was growing up, whenever I’d leave the house, my mother would say, “Thank you for listening.” She was seeing me off with the expectation and prayer that wherever I was heading – work, school, to hang out with friends, or on an adventure – I would be listening for the guidance of my divine Father-Mother, God.

The Bible says, “The Lord shall guide thee continually” (Isaiah 58:11). And, “Thine ears shall hear a word behind thee, saying, This is the way, walk ye in it, when ye turn to the right hand, and when ye turn to the left” (Isaiah 30:21). The nature of God, divine Love, is to guide, and our nature as children of God is to listen and to follow.

Human thinking may be well-intentioned; but disconnected from God, it is limited and subject to fear and ego. Spiritual consciousness – the true consciousness of all of us as God’s spiritual offspring – is connected to God and is inherently responsive to divine inspiration. When we listen spiritually and follow trustingly, our steps are purposeful and protected. This is because God, divine Mind, continuously communicates His goodness and purity throughout creation.

A friend once shared with me that he strives to practice listening to and following God even in the little things. Then, when bigger things come up, he is already in the practice of listening, yielding, and following.

While serving in the Marine Corps, I too sought to listen to God in the little things. Once, while I was on a mission, the thought came clearly to me, “Get up and move.” I was in the mind-set of listening, so it felt natural to follow this intuition. I moved, and the sergeant who was with me followed. As we sheltered in the new location, a series of mortars landed and exploded where we had been moments before, and we were both protected.

Mary Baker Eddy, the discoverer of Christian Science, wrote a poem called “‘Feed My Sheep,’” which begins, “Shepherd, show me how to go” (“Poems,” p. 14). Later it says, “I will listen for Thy voice.”

We can trust that God, our heavenly Shepherd, shows all of us how to go, and that we can listen and hear just what we need.

For an extended discussion on this topic, check out “Listen to God,” the Nov. 29, 2021, episode of the Sentinel Watch podcast on www.JSH-Online.com.

A message of love

Pearl Harbor remembered

A look ahead

Thanks for joining us today. Come back tomorrow, when we share a personal essay from a high school football coach who was inspired by his players after a big, season-ending defeat.