- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- How these workers turned the ‘Great Resignation’ into better careers

- Is China ensnaring poor countries by building their infrastructure?

- Rwanda keeps the peace in Mozambique. Why?

- Reading, writing, and cybersecurity: Education for the digital age

- Amid species loss, the ‘oh my’ mammals that are doing better

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Forgoing the blame game

It was an eye-catching headline amid the current flood of news: “Americans overwhelmingly do not blame God for the pandemic, or any suffering.”

The article that followed summarized a new Pew Research Center survey of how Americans – 91% of whom believe in God as described in the Bible or a higher power – have thought about life in a difficult year that has also seen destructive wildfires, flooding, and tornadoes.

Pew conducted the survey to solicit “views on why terrible things happen.” About 70% of respondents, religiously affiliated or not, supported the idea that people’s own actions as well as our institutions play a role. But 61% also said hard times present “an opportunity for people to come out stronger,” and majorities indicated that troubling events made them more grateful for the good in their lives and more compassionate toward those who were struggling.

Pew then homed in on the 91% – a number that remains high, despite the rise of religiously unaffiliated people – and asked about the effect of hard times on spiritual faith. Some 15% said that suffering indeed raised questions about God’s all-power or love. But far more said that “‘only a little’ (22%) or ‘none at all’ (46%) of the suffering in the world is punishment from God.”

For David Lamberth, a Harvard Divinity School professor who helped design the survey, it reinforces the idea that the dominant religious view among people “is of God as comforter or source of salvation from suffering in the long run.”

As one Mormon said, “God has not promised us that we will not have hard or difficult times in our life. He HAS promised us that He will ALWAYS be with us.”

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

How these workers turned the ‘Great Resignation’ into better careers

The pandemic has prompted many people to leave the job market. It could be a golden opportunity to upgrade skills that boost career opportunities. But many are not taking it – the result of a complex array of factors that could have long-term impact.

The pandemic has created a worker shortage and opened up opportunities to change jobs or careers. The number of workers quitting their jobs hit a record high in September, and October was not far behind, according to federal data that stretches back to 2000.

Yet relatively few U.S. adults are using the current period for training in new skills. And in some ways that’s surprising, since education can be a key to securing better pay or a more fulfilling career. In fact, if nothing changes, community colleges – the schools of choice for many adults looking to upgrade skills – will see the sharpest two-year enrollment drop in at least 50 years.

Some workers, however, are opting for new training – and seeing it pay off.

“I was thinking of a career change,” says Rayang Bouda, who had a payments-processing job near St. Louis. She found a six-month professional development program for women. And a couple of weeks ago, she was hired by Pfizer as an inspector.

She says she loves the new work, and it comes with a pay increase of $5 an hour. “I really love doing something that impacts other people positively.”

How these workers turned the ‘Great Resignation’ into better careers

When the pandemic hit in early 2020, Angie Champion Holland’s career in hotel construction sales fizzled. With travel severely restricted, building projects got canceled. By May, she was out of a job.

She could have stayed home. A 40-something mother of four, with three other stepchildren and two grandchildren, she had plenty to do. Instead, Ms. Holland went back to school.

Although based in the Atlanta area, she started with two online courses from Southern New Hampshire University – the normal course load. In her next semester, she moved to three classes per semester, and a month ago she graduated summa cum laude with degrees in psychology and sociology.

“I wasn’t happy in construction,” Ms. Holland says. “The type of company that I can work for has definitely changed. I can work in these fields where I have a personal interest” – social justice; diversity, equity, and inclusion; and addiction recovery.

Ms. Holland is an exception. The pandemic has created a worker shortage and opened up opportunities to change jobs or careers, yet relatively few U.S. adults are using the current period to train for new skills. And in some ways that’s surprising, since education can be a key to securing better pay or a more fulfilling career.

In fact, among adults above age 24 who have education plans, nearly half have seen those plans canceled or disrupted, according to a survey by Strada Education Network, a social impact organization based in Indianapolis and focused on paths from education to employment.

If nothing changes, community colleges – the schools of choice for many adults looking to upgrade skills – will see the sharpest two-year enrollment drop in at least 50 years, according to the National Student Clearinghouse Research Center.

Many factors have contributed to the drop in enrollments. “It’s hard to put your finger on any one thing,” says Russ Deaton, executive vice chancellor of the Tennessee Board of Regents, which has seen enrollment of adult learners fall 20% across the state’s 40 community and tech colleges over the past two years.

Why enrollment dips

One reason for the decline is, paradoxically, the strength of the economy. Worker training typically falls when the economy is humming and employers are hiking pay and offering sign-up bonuses. It’s when jobs are scarce that employed adults go back to school.

“Workers [are] going from one job to another job, looking for better pay,” says Andrew Weaver, labor economist at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. “You’re not going to see a lot of people upskilling.”

Yet upgrading skills is key to upward mobility, especially among low-income workers. Only 4 in 10 of these workers leave low-paying jobs over a decade, according to a Brookings study this summer. And the longer they work in those jobs, the less chance they have of moving up. By year 10, only 1 in 100 transition to better pay.

Other factors also play a role in the training trends. The same fear of contagion that has kept people from going back to a job has also prevented them from attending an in-person classroom. The lack of child care is another big barrier, keeping parents from returning to either the job market or the classroom. “For many people, it’s been a serious binding constraint for their work lives,” says Greg Wright, a fellow at the Brookings Institution, a Washington think tank.

Then “there is this question whether people are generally changing their attitudes toward their work lives,” says Mr. Wright. “That’s still a bit of a mystery.”

For example: The number of workers quitting their jobs hit a record high in September, and October was not far behind, according to Bureau of Labor Statistics data that stretches back to 2000. Are people quitting because they’re taking new jobs for better pay – or because of something else? Some workers may want to adjust their work-life balance to spend more time with friends and family.

Others want more meaningful work. And some of them are, in fact, opting for new training as a transitional step amid the pandemic.

A boost in pay

“I was thinking of a career change,” says Rayang Bouda, who moved with her husband to the United States from Burkina Faso in West Africa 10 years ago. “I really love doing something that impacts other people positively. So anything that is social or related is something that I have a passion for.”

On days off from her payments-processing work at a bank, the St. Louis-area resident began looking online. She found a local program called Rung for Women, which aims to help women achieve sustained independence. She signed up for the organization’s six-month program with a personal coach who helped her define her career goals before she started training, which included practical classes like career fundamentals and advanced professional skills. A couple of weeks ago, right before she finished the program, she was hired by Pfizer as an inspector.

Ms. Bouda says in an email that she loves her new job and feels blessed to work for a company that positively changes patients’ lives. An added bonus: She’s earning $5 more an hour than at her previous job.

Given the obstacles to advancement facing women of color, Ms. Bouda’s upward mobility is rare. For every 5 job changes that Black women make, only 2 on average lead to better-paying jobs, according to the Brookings study. For white and Asian men, 3 in 5 job changes lead to better pay. And higher income can be a strong motivator for many people.

Seeking job security

Mahafuzur Rahman was a dentist in Bangladesh before he, his wife, and two children emigrated to the U.S. in October 2019. In Boston, he strung together part-time jobs to keep food on the table – security, sales, cashier – working 72 hours a week, sometimes more. When the pandemic hit, he lost his jobs at the pizza parlor and fast-fashion retailer Primark. Whole Foods reduced his hours.

“Then I decided that I needed to do something where I cannot lose anything,” he says. Friends had told him how biotech in Boston was booming and seemed unaffected by the ups and downs of the economy. So he signed up for a five-month biology and chemistry boot camp at Jewish Vocational Services (JVS), a local adult workforce development organization. Then he signed up for the next phase of the program: 10 months of hands-on training at a local community college to learn lab skills and get certified for work at a biotech firm. He graduates from Quincy College this month.

“Maybe I’ll get a job in December,” Mr. Rahman says. The last time he applied for a biotech job, the pay offered was twice what he was earning at most of his part-time gigs.

While many adult learners say the pandemic had little effect on their decision-making, in many cases it has had an indirect impact. When shutdowns forced community colleges and worker-development programs to switch to online teaching, these institutions were able to reach a new class of online students who might not be able to make classes in person.

“The reason I started thinking about going to college is that I heard about JVS and their evening and online classes,” says Puja Phuyal, a mother of two in suburban Boston who had spent 16 years working in banking. “It’s easier to get jobs from biotech than any other area.” And friends were telling her about how well paid they were. She has just finished the same biotech course at JVS that Mr. Rahman completed and will start the follow-up training at local Quincy College next month. Had the training not been online, she might not have come to JVS.

“That would be a long commute and I am working,” she says.

Is China ensnaring poor countries by building their infrastructure?

China is often depicted as a predatory lender. But when it comes to infrastructure, that narrative doesn’t capture the full view – and risks casting nations as victims when they aren’t necessarily.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

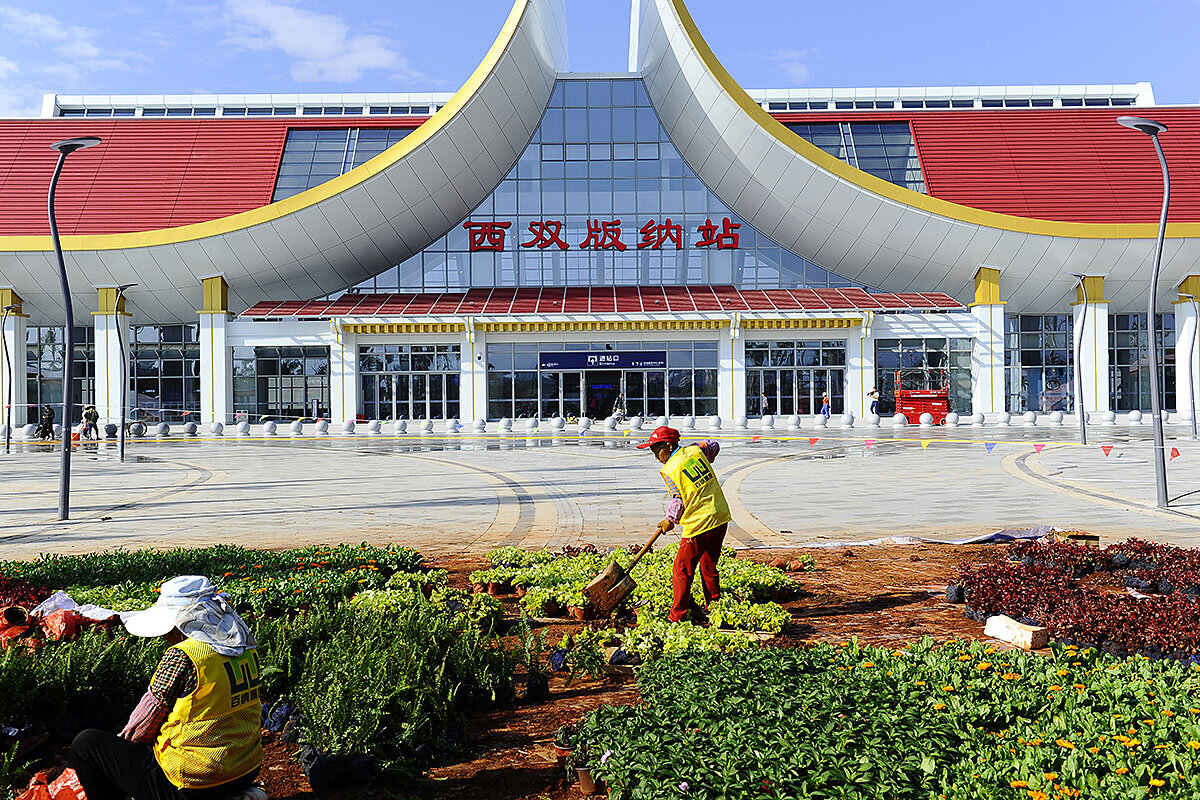

Southeast Asian nations have long held a vision of building railroads to connect their economies, and today China is creating that network with its Belt and Road Initiative. This month a key link came together with the opening of the China-Laos railway. The BRI is a massive program – estimated at $1 trillion – launched in 2014 to build a network of ports, railways, and roads linking China more closely with the rest of Asia, Africa, and Europe.

Since 2017, Beijing has faced criticism from foreign officials and academics for using its financing and infrastructure projects to ensnare poor countries with heavy debt loads and thereby win strategic leverage. They call it “debt-trap diplomacy.” But some analysts question whether this narrative tells the whole story, saying instead that it oversimplifies and distorts the motivations, risks, and relationships between China and the countries accepting BRI projects.

“We have to ascribe the agency to countries around China – they’re not just victims,” says David Lampton, a China expert and senior fellow at the School of Advanced International Studies at Johns Hopkins University.

Is China ensnaring poor countries by building their infrastructure?

Snaking around rugged mountains and over deep river valleys, a train raced along a $5.9 billion Chinese-built railway connecting Laos and China this month, its inaugural run marking the debut of China’s first international rail network.

For Laos, a landlocked nation of 7 million, the 257-mile line from the Laotian capital of Vientiane north to China’s border creates a link to global supply chains that could help Laos attract investment and trade, create jobs, and fuel economic growth. For China, the project is the first phase of an ambitious strategy to expand its rail network through Laos, Thailand, and Malaysia to Singapore.

Yet the debt generated by the venture is a source of concern not just for Laos but also China, experts say, as the economic benefits could take years to realize. And the worries on both sides underscore a growing debate over Chinese leader Xi Jinping’s signature Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), of which the China-Laos railway is a key regional link, and whether it amounts to “debt-trap diplomacy.”

The BRI is a massive program – estimated at $1 trillion – launched in 2014 to build a network of ports, railways, and roads linking China more closely with the rest of Asia, Africa, and Europe. Since 2017, Beijing has faced criticism from foreign officials and academics for using its financing and infrastructure projects to ensnare poor countries with heavy debt loads and thereby win strategic leverage. But some analysts question whether this narrative tells the whole story, saying instead that it oversimplifies and distorts the motivations, risks, and relationships between China and the countries accepting BRI projects.

“It’s much more a creditor trap than a debt trap at this point,” says Deborah Brautigam, professor of International Political Economy at the School of Advanced International Studies (SAIS) at Johns Hopkins University.

An infrastructure gap

To be sure, there are cautionary cases – such as the often-cited granting by Sri Lanka of a 99-year lease on its Hambantota port to a Chinese company in 2017 to help relieve its debt woes. But Dr. Brautigam and other experts see Beijing less as a predatory lender seeking to force defaults on vulnerable developing countries and more as a new player in international construction learning by trial and error – “crossing the river by feeling the stones,” as the Chinese saying goes.

Another key factor – downplayed in the debt-trap analysis that casts borrowing countries as victims, experts say – is that borrowers also have leverage and agency and can inflict costs on China. “The Chinese are lending to countries … in an over-exuberant way and getting burned,” says Dr. Brautigam. In 2018, for example, China had to restructure a loan to Ethiopia for a $4 billion railway linking its capital of Addis Ababa with Djibouti, extending the debt 20 years and taking a significant loss. Beijing has also restructured debt in Cameroon and Mozambique for projects that needed longer timelines to generate revenue.

The debate over Chinese lending is significant because developing countries face a huge shortfall in paying for the infrastructure they need. According to the Global Infrastructure Hub, the world will face a $15 trillion gap between projected and needed global infrastructure by 2040. While China’s investments are driven by its national interests, they also have potential to benefit the rest of the world, experts say.

And as China’s growth slows and debt at home threatens to cause economic instability, Beijing has signaled new limits on investments. At a symposium on the BRI last month, Mr. Xi called for China to strengthen its “early warning and assessment of the risks of overseas projects.”

Indeed, Beijing’s increasingly risk-averse posture will likely lead it to make more selective investments in the future, as it seeks a better balance between domestic and overseas lending, says David Lampton, a China expert and senior fellow at SAIS who has studied the BRI. Beijing also seeks to cooperate with other creditor countries and multilateral lenders to share the burden, he says.

“There are two sides to this story,” he says. “The Chinese view, at least in many quarters, is … we’re loaning to risky places. They can’t repay us. And we’re getting trapped with dubious assets.”

Often the push for Chinese investment comes from the recipient countries – as with the Southeast Asian railway project that the China-Laos line is part of, says Dr. Lampton, co-author with Selina Ho and Cheng-Chwee Kuik of “Rivers of Iron: Railroads and Chinese Power in Southeast Asia.”

Whose risk is it?

Southeast Asian nations have long held a vision of expanding and modernizing railroads to connect their economies and sought China’s help 20 years ago, only to be rebuffed then because Beijing was busy building its own road and rail infrastructure. “We have to ascribe the agency to countries around China – they’re not just victims,” says Dr. Lampton.

Today, China not only has the financing and technology to build the Southeast Asian rail network, but it also faces little competition for the business, he says. “It’s the lack of [comparable] alternatives for these countries that created dependence on China.”

In landlocked Laos, excluded from the maritime transport network that handles more than 80% of Southeast Asian trade with China, officials see the railway as the country’s best shot at fostering development.

Still, the risk of the China-Laos rail project is significant. Laos is already a heavily indebted country, with a public debt-to-GDP ratio estimated at 55% – with China’s share of that exceeding 10%. Last year, international credit rating agencies downgraded Laos to one notch above a rating of debt default, making it harder to borrow internationally.

If Laos can’t repay the $480 million loan for the project that it borrowed from China, which has a 70% stake in the railway venture, it is likely Beijing will have to absorb the loss, experts say. Beijing is willing to accept the risk of the Laos leg of the railway because it is the best pathway to the rapidly modernizing, middle-class economies of Thailand and Malaysia, experts say.

One tool China uses to mitigate the risks is to negotiate alternative revenue streams with host governments – for example revenue from mines and banana plantations in Laos, or the rights to commercial development along the railway, they say. China has struck similar deals in African countries including Kenya, where a tax on imports is used to help pay for a China-built railway, says Dr. Brautigam, director of the China Africa Research Initiative. “I see this as really creative [financing] rather than nefarious,” she says.

“Many of these projects are good ideas, but they may not be good in a short and strictly commercial time period,” she adds. “Some of them may be true white elephants,” but others “will be big contributors.”

Rwanda keeps the peace in Mozambique. Why?

African countries usually turn to the U.N. or to their former colonizers to help put down rebellions. Rwanda’s success in Mozambique offers a novel solution, but its motives are unclear.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

African governments facing rebellion generally turn to their former colonizers, or to the United Nations, for help in restoring peace. But Mozambique took an unusual path earlier this year: It asked Rwanda to put down an Islamist uprising.

The intervention worked, prompting some observers to see a new model of inter-African cooperation on the peacekeeping front; Rwandan President Paul Kagame cited African solidarity as the main driver for his involvement.

There is no doubt that Rwandan forces are well trained and experienced. But doubts about their government’s motivations have surfaced. The soldiers are deployed around gas-field installations operated by Total, a French energy company, prompting suspicion that Rwanda is protecting French commercial interests in return for a fresh injection of development aid.

Rwandan soldiers who joined the civil war in Congo 20 years ago were widely accused of looting minerals and timber; Mr. Kagame could have his eye on Mozambique’s vast natural gas reserves, it is suggested.

Peace has returned to northern Mozambique, and local residents displaced by the violence are returning home. But it remains to be seen whether there is more to Rwanda’s military intervention than meets the eye.

Rwanda keeps the peace in Mozambique. Why?

When rebels attacked her village in northern Mozambique last December, Safia Shawal and her three sons fled into the bush, beating a path through remote plantations in search of safety. By the time the family staggered into a camp for displaced people five days later, Ms. Shawal had had to leave behind the body of her 5-year-old son, Assane.

He was one more victim of an increasingly brutal insurgency that had trapped residents of Mozambique’s far north between rebels and the national army.

Earlier this year though, the situation suddenly changed. Town by town, rebel-held areas were liberated, and returning residents cheered the soldiers who had arrived so unexpectedly.

The troops turning the situation around did not belong to any of the superpowers that have so often stepped in to restore order in their former African colonies. Instead, they came mostly from Rwanda, a tiny East African nation with big – and, critics say, suspect – peacekeeping goals.

Over the course of two weeks in July, a 1,000-strong Rwandan detachment made more headway than Mozambique’s own army and foreign mercenaries had achieved in four years, wresting back key infrastructure that had been under rebel control for two years.

Last month, for the first time since Ms. Shawal became one of more than 800,000 people displaced by the insurgency, she felt hopeful again.

“We’re going to return home,” she said in the local Emakwa dialect.

Mozambique’s pivot to an African ally could be a blueprint for other countries battling their own insurgencies, where the necessary troops and firepower have traditionally come from former colonizers or other Western nations. Rwandan President Paul Kagame has been quick to play up his country’s battlefield success, crediting African solidarity as the main driver for his involvement.

But critics fear he might be giving cover to Western powers seeking to exert influence at arm’s length and secure their interests in resource-rich trouble spots without putting their soldiers in the line of fire. Analysts suggest that France might be behind Rwanda’s push into Mozambique, as it seeks to protect a $20 billion gas field investment by French energy giant Total.

Human rights activists also accuse President Kagame, in power for nearly three decades, of using his role in the conflict to whitewash his human rights record at home, where his opponents are routinely jailed.

Success on the battlefield could position Mr. Kagame as a reliable solution for troubled African countries in a region feared to be the next global insurgency battleground. But some wonder what he will seek in return for Rwandan assistance.

“This support is not free to Mozambique,” warns Borges Nhamirre, a researcher at South Africa’s Institute for Security Studies. “What we don’t know is when and how Mozambique will have to pay for Rwandan support.”

The run-up to Rwanda’s intervention

Five years ago, youths in Cabo Delgado, a resource-rich province on Mozambique’s northeastern coast, launched an uprising against the government. The region’s vast ruby and gold fields have swelled state coffers in the capital, Maputo, 2,400 kilometers (about 1,500 miles) away, while Cabo Delgado remains impoverished. Untapped gas fields have drawn massive investments from the U.S.’s ExxonMobil and Total, but few locals have benefited.

Frustrated, young people in the predominantly Muslim region seeking jobs and government services lit the fires of an insurgency that simmered for four years, largely out of the international spotlight.

In 2019, the insurgents pledged allegiance to Islamic State, marking the first Islamist-linked conflict in southern Africa and alarming the world. The nature of their relationship is uncertain, but last March the fighters launched a brutal attack on the port town of Palma, close to the gas projects, that left dozens dead. By April, the militants controlled a significant chunk of territory in four of the north’s five provinces.

Total announced it would suspend work on its sites – and that 65 trillion cubic feet of gas would stay underground until the area was secure. Mozambique now had a reason to solicit international military assistance.

French forces, experienced in fighting Islamist insurgencies in Africa, might have seemed an obvious choice for Mozambique, but Paris is already tiring of its battle with jihadis in former colonies Mali, Chad, and Burkina Faso. Enter Rwanda.

Some experts suspect that France, seeking to protect its corporate interests militarily as it has done elsewhere in Africa, could be bankrolling Rwandan troops to protect the gas concessions. “RDF [Rwanda Defence Forces] are only concerned about the gas sites via France’s interests,” says Jasmine Opperman, a security consultant who follows the Mozambican conflict closely.

Sources in Cabo Delgado confirmed to the Monitor that RDF troops are specifically protecting the gas sites in the area.

Mr. Kagame denies third-party involvement however. “We are using our means,” he said in an interview aired on Sept. 5 by the Rwanda Broadcasting Agency. “Nobody sponsored us.”

A fresh start with France

Until recently, Franco-Rwandan relations had been frosty; Mr. Kagame has long accused France of backing the Hutu rebels who killed nearly a million Tutsis in the 1994 genocide.

Then in March this year, a commission established by French President Emmanuel Macron concluded that France had been blinded by its colonial attitude to events leading up to the genocide and bore “serious and overwhelming” responsibility.

President Macron later visited the Rwandan capital, Kigali, made up with his Rwandan counterpart, and announced 370 million euros in fresh development aid.

Although one of the smallest countries on the continent, Rwanda plays an outsize role in United Nations-run peacekeeping operations in Africa, sending over 5,000 troops on such missions. The RDF are well trained, well equipped, and experienced in fighting rebels in East and Central Africa.

But details of their deployment to Mozambique remain shrouded in mystery. The terms of the arrangement between the two countries have never been made public; nor has the exact number of Rwandan soldiers, how long the mission will last, or how it is being funded. The Mozambican Parliament has been left in the dark, with lawmakers saying they were sidelined in the arrangement between President Filipe Nyusi and President Kagame.

Equally concerning to civil society activists in Mozambique is Mr. Kagame’s reputation. “Rwanda isn’t by far an example of good governance in terms of democracy, freedom, or civic space,” worries Americo Maluana of Mozambique’s Center for Democracy and Development.

Rwandan forces joined the civil war in Congo on the rebels’ side in 1998, and their involvement was notable for allegations that they extracted payment by looting minerals and timber. Mr. Kagame’s intervention in Mozambique could see him profit from the country’s gas too, when it comes online.

At the same time, the Rwandan government is widely believed to be behind a string of assassinations of its political opponents abroad, suggesting another possible motive for its intervention in Mozambique. In the past three years, three Rwandan opposition members who fled to Mozambique have died or disappeared.

“If I were a part of that community” of exiled opposition figures in Mozambique, says Michela Wrong, who has written about the assassinations, “I would be very worried.”

Amade Abubacar contributed reporting from Pemba, Mozambique, to this article.

Reading, writing, and cybersecurity: Education for the digital age

Students are at home in the digital world, but know little about keeping that space secure. With online security threats evolving, schools are considering more ways to give young people the foundational understanding and tools they need.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

In recent years, schools in the United States have had to cancel classes or deal with data breaches because of cyberattacks. Last year, 50 ransomware incidents against public K-12 schools were reported, up from 11 in 2018.

Realizing how vulnerable they are has caused districts to look more closely at how prepared students are to navigate – and defend themselves – online. For some educators, teaching cybersecurity formally is essential, and more districts are starting to agree. The training also potentially offers a pipeline for an industry in need of applicants.

“The ransomware attacks that were happening in the K-12 systems were absolutely that light bulb moment for districts and, even state departments of education, to open their eyes up” to teaching cybersecurity to students, says Kevin Nolten, director of academic outreach for CYBER.ORG.

At South County High School in Lorton, Virginia, Christopher Long teaches a course called Cybersecurity Fundamentals. Now in its fourth year, the class includes training in the perils of phishing attacks, the basics of software programming, and other practical knowledge for cybersecurity jobs.

Mr. Long envisions such courses evolving from electives to requirements, the same way personal finance courses eventually did. “It’s going to become required knowledge,” he says.

Reading, writing, and cybersecurity: Education for the digital age

Listening to Christopher Long describe teaching his subject makes parts of it sound like a breezy outdoor summer camp, not training for one of the most highly sought after, yet undertaught, skillsets in the country.

Capture the flag competitions and scavenger hunts are examples of what the fourth-year teacher of the course Cybersecurity Fundamentals calls “gamification” of his subject. But Mr. Long, a former network administrator who switched to teaching at South County High School in Lorton, Virginia, six years ago, knows that cybersecurity itself is no game.

“The tasks that they have to accomplish are things that if they get a job in cybersecurity, they’ll do all the time,” he says.

His district in Fairfax County, Virginia, outside of Washington, D.C., was the target last year of a cyberattack, one of 50 ransomware incidents against public K-12 schools reported across the United States in 2020 – up from 11 in 2018. Mr. Long suggests that cybersecurity courses may become academic requirements in the years ahead and says this type of education is “desperately needed.” Some school districts are starting to agree, both for their defense and for their students’ futures.

“The ransomware attacks that were happening in the K-12 systems were absolutely that light bulb moment for districts and, even state departments of education, to open their eyes up” to teaching cybersecurity to students, says Kevin Nolten, director of academic outreach for CYBER.ORG, a Department of Homeland Security-backed organization, whose mission is to bolster K-12 cyber education.

“Long-term solution”

The urgency is being felt across the country. Districts like Haverhill Public Schools, north of Boston, and Baltimore County Public Schools in Maryland, have had to cancel classes due to cyber attacks in recent years.

The Government Accountability Office called on the U.S. Department of Education this fall to take additional steps to help protect K-12 schools from cyber threats, but its recommendations were not pedagogical. They were geared toward getting the department’s leadership to prepare for the years ahead.

“This is a really hard challenge from a federal level because the federal government has very little role in education,” says Laura Bate, a senior director of the Cyberspace Solarium Commission, a group tasked by Congress to devise a strategy to defend the United States in cyberspace.

Ms. Bate calls education a “long-term solution” to cybersecurity problems. “We need to be able to teach this [subject] to our kids,” she says.

The number of high schools offering computer science has gone from 35% in 2018 to more than half of America’s high schools (51%) in 2021. But only 4.7% of high school students are enrolled in a foundational computer science course, a subject to which cybersecurity is a subfield, according to a recent report from Code.org.

In Florida, Broward County Public Schools, the target of a ransomware attack earlier this year, worked with CYBER.ORG to create K-12 cybersecurity standards for students and plans to offer specific training to teachers tied to these standards later this school year. Other states and localities will have the option to incorporate the new standards into their curricula.

Monika Moorman, a fourth grade teacher at Broward County’s Central Park Elementary in Plantation, Florida, who worked on the national team of educators to craft the standards, understands their importance for the students in her classroom.

“Students who are exposed to cybersecurity learning standards become better versed at navigating the online realm,” the district’s 2021 teacher of the year says, in an email to the Monitor. “They learn to understand the ramifications of their digital footprint which guides them in a responsible online behavior.”

Taking steps in Virginia

In Fairfax County, only about 2% of the district’s nearly 60,000 high schoolers take the elective class that Mr. Long teaches, where students learn both the ethics of the emerging area and the technical knowledge, such as how to run a command line on a Linux operating system.

“People hear a lot of things about ‘you shouldn’t do this, you should do that,’ but don’t really know why,” says Mr. Long, in an interview last month, sitting at his desk after a full day of teaching. “And honestly, a lot of the kids don’t care too much until they actually see the why.”

The students’ training doesn’t start with how to stop a ransomware attack. It starts with how to be a good digital citizen. One of the first lessons that Mr. Long teaches is cybersecurity ethics. The class explores, for example, intellectual property issues and the bootlegging or downloading of materials illegally.

The students are “growing up in a generation where [bootlegging] is so mainstream that they’ve never even considered the ethical issues,” Mr. Long says. “There’s a lot of people whose livelihoods depend on some of these services being paid and if you’re hacking to get free service, you’re potentially threatening the very service that you want to use.”

For the digital-native students – some of whom have been online since they were toddlers – these lessons are eye-opening, their teacher says.

The eye-opener for the district was last year’s ransomware attack. Fairfax County Public Schools hired its first director of cybersecurity after the incident, which resulted in employees’ personal information and student disciplinary records being pilfered by the hackers and held for ransom. Even so, classes continued, and Mr. Long says the attack did not have as much influence on his students as the more publicized Colonial Pipeline cyber incident, which caused gas prices to rise in the area earlier this year.

Whitney Ketchledge, Fairfax County Public Schools’ coordinator for career and technical education, says the class helps equip students for the world they’ll engage in as consumers, but also she emphasizes the preparation that the class provides for a potential career.

In addition to ethics, students in the class learn how a network operates, the perils of phishing attacks, and the basics of software programming.

“Our students are looking for ways to make things better,” says Dr. Ketchledge, in a Zoom interview. Separately, a handful of students from the district are gaining hands-on experience by interning with its department of information technology.

There are about a half a million cybersecurity job openings in the United States, President Biden said from the White House in August. He called the vacancies a “challenge” but also “a real opportunity.” Much of that opportunity though – both for cyber defense and cybersecurity education – lies in the hands of decision-makers outside of Washington.

As with personal finance classes, which started as electives and became required courses, a similar trend may be occurring with cybersecurity, Mr. Long says. “There’s a good chance that there will be at least some version of cybersecurity that will start to fall into that category,” he says. “It’s going to become required knowledge.”

Points of Progress

Amid species loss, the ‘oh my’ mammals that are doing better

Scientists showed this year that extinction of plants and animals is accelerating. But the rebounding of a few high-profile vertebrates can help emphasize that saving species is possible – with concerted efforts.

Amid species loss, the ‘oh my’ mammals that are doing better

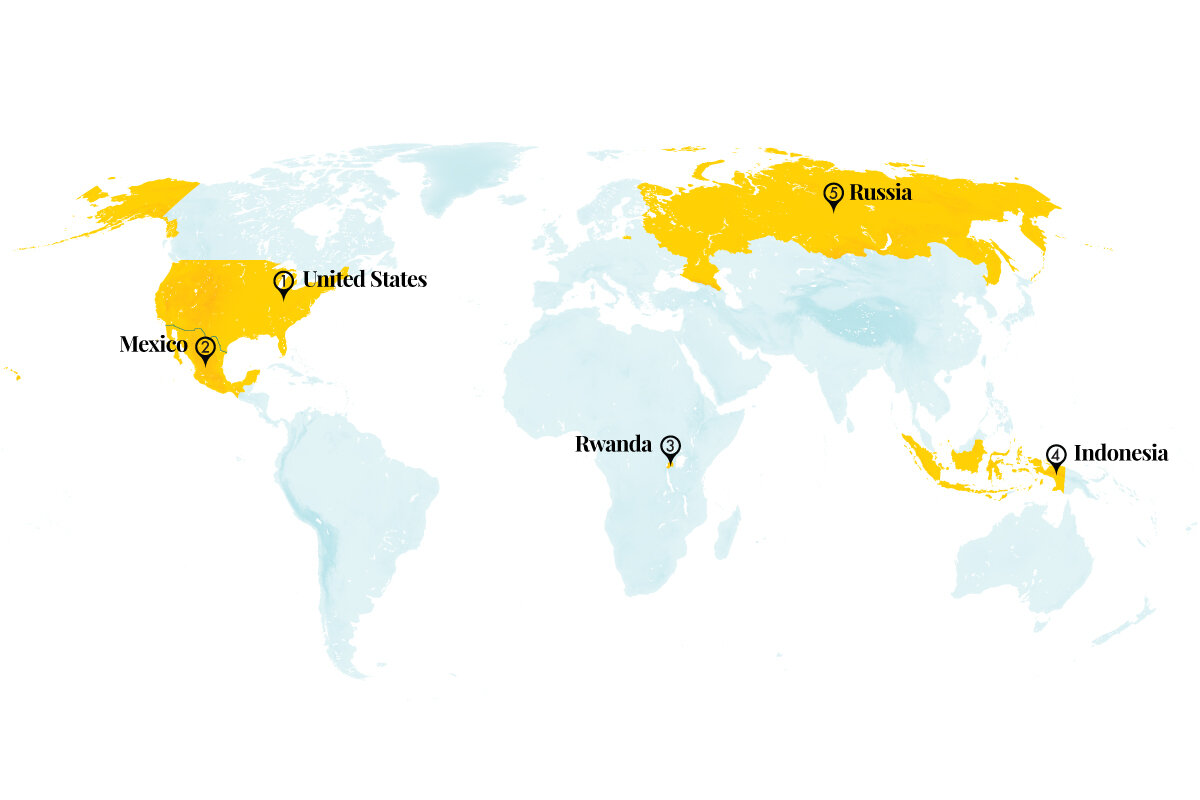

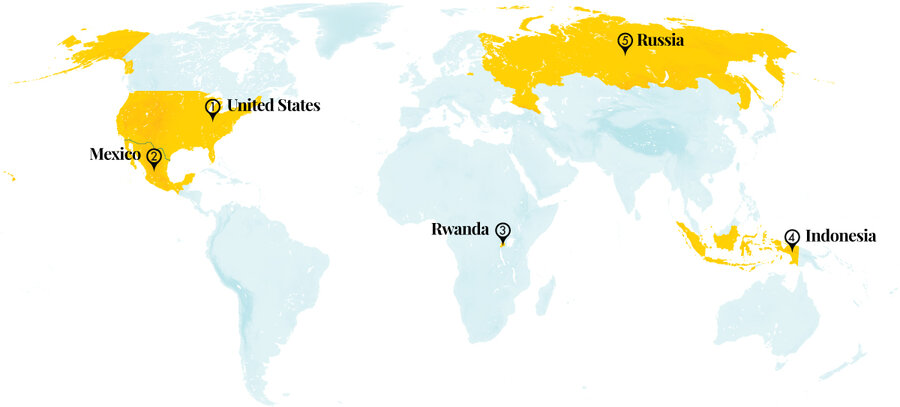

Mountain gorilla and jaguar numbers are encouraging conservationists, partly because room made for their habitats is helping to ensure survival. Meanwhile, roundabouts are also serving their intended purpose – manipulating travel for greatly increased safety.

1. United States

Carmel, Indiana, has created safer, more environmentally friendly road travel by embracing roundabouts. Starting in the late 1990s, Carmel has installed 140 roundabouts and counting – more than any American city. Not only have the roundabouts become a local tourist attraction, but their success has also helped push other municipalities to make the switch.

The primary benefit is safety. More than 50% of serious car crashes occur at intersections, but modern roundabouts make all crashes, injuries, and deaths less likely. A recent study by the Insurance Institute of Highway Safety found injury crashes dropped by nearly 50% at 64 roundabouts in Carmel. There’s also a climate benefit to roundabouts; since drivers don’t have to stop and idle at traffic lights, vehicles burn significantly less fuel, according to the Federal Highway Administration. Studies estimate as much as a 59% decrease in vehicle emissions compared with signaled intersections. Officials also point out that roundabouts are resilient against power outages, since they don’t need electricity to operate.

The New York Times

2. Mexico

The jaguar population grew by 20% from 2010 to 2018, according to the first two censuses of the animals in Mexico. The jaguar’s current habitat ranges from Northern Argentina through Brazil and into Central America, but for a long time, ecologists had little understanding of how many Jaguars actually lived in the Americas. The initial census in 2010 allowed researchers to develop conservation strategies that were embraced by both the government and scientists, including preserving wildlife corridors and resolving conflicts with livestock owners. Still, the National Alliance for Jaguar Conservation wasn’t expecting to see a population boost within the decade.

Using data collected from camera traps, researchers estimate there are now 4,800 jaguars in Mexico. “This [paper] is very important,” said jaguar researcher Ronaldo Gonçalves Morato, who works in Brazil, home to the largest contiguous jaguar population. “They are connecting science with conservation plans. It can be a good model for researchers – not only working with jaguars, but all the other big cats or other species that are critically endangered.”

3. Rwanda

Rwanda has reversed its mountain gorilla decline by developing conservation solutions that also help humans. In the 1960s when Dian Fossey went to the Virunga volcanoes – home to most of the world’s mountain gorillas – there were only 254 individuals left in the wild due to poaching and habitat destruction. Today, mountain gorillas are the only great ape whose numbers are growing. Rwanda has a healthy population of more than 600, and experts say poaching is no longer an issue.

Their rebound is the result of aggressive conservation and a shift in public attitudes toward gorillas. Tourism, namely the government-regulated visits to Volcanoes National Park where guests pay $1,500 to spend an hour among the gorillas, has played a critical role. Ten percent of that money goes to neighboring districts and funds new health centers, housing projects, and community business investments such as dairy cows and knitting machines – as much as $650,000 annually per community. The Dian Fossey Gorilla Fund is also employing more than 1,500 local workers, including many women, to build a new science campus. Chief park warden Prosper Uwingeli says much of his passion for gorilla conservation “comes from what they’re helping [Rwandan communities] to achieve.”

60 Minutes

4. Indonesia

With a landmark decree from the local government, the Gelek Malak Kalawilis Pasa clan in Indonesia’s West Papua province is closer to cementing its land rights. The Sorong district head recently issued a decree recognizing the community’s rights to 8,023 acres of ancestral land. This decree – a first in Sorong – is expected to strengthen the clan’s legal rights, improve its ability to manage the land, and help protect its forests from commercial exploitation. It is also an essential first step to gaining recognition from the central government.

To date, Indonesia has recognized only about 147,000 of the estimated 26 million acres of ancestral forests throughout the country, for roughly a tenth of the Indigenous communities that inhabit them. For the Kalawilis to obtain the title to its lands, the clan must request formal recognition from the Ministry of Environment and Forestry in what’s typically a costly and lengthy process. But Kalawilis head Herman Malak hopes the local decree will inspire other nearby clans to seek legal protections. “We Gelek Malak have proved that we can protect [our] customary lands and forests,” he said.

Mongabay

5. Russia

Russia’s forest protection service found Siberian tiger footprints in the Sakha republic for the first time in half a century, sparking hope for the endangered cat’s recovery. The tracks, which are about 6 inches long, were spotted by pilot Andrey Ivanov along a riverbank in southeastern Sakha, according to a video he recorded at the site in early November. The discovery comes weeks after tiger photographs were taken in the adjacent Khabarovsk region, near the village of Chumikan and also near the Shantar Islands. Experts assume the sightings were of the same animal.

Once widespread throughout northern Asia, Siberian tigers – also called Amur tigers – were nearly hunted to extinction in the 20th century. They’re now a protected species in Russia, and ongoing conservation efforts have grown the tiger population in the Far East regions from 330 in 2005 to more than 600 today. “The fact that the tigers are exploring their ancestral hunting grounds indicates that the number of the northernmost tigers is not a cause for concern,” said Victor Nikiforov from the Tigrus Conservation Fund.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Help for Afghan refugees

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

Since the fall of Kabul, Afghanistan, on Aug. 15, some 38,000 Afghan refugees have been placed in communities across 46 U.S. states. Tens of thousands more are housed on U.S. military bases, awaiting placement.

These families have fled for their lives from the Taliban. Family members had been assisting U.S. forces in Afghanistan in numerous ways, including as translators, as well as working in jobs such as humanitarian workers and women’s rights advocates.

The refugees have arrived with few possessions.

“We didn’t bring anything but ourselves,” one young male refugee told a Minnesota television station.

The government website Welcome.us offers suggestions on how ordinary Americans can help. Businesses can offer job opportunities or donate supplies such as household goods, diapers, and baby formula. Individuals can form sponsor circles in their communities. These groups help refugees with basic tasks, such as finding housing, getting children into school, and searching for employment, as well as myriad other needs.

At this season of giving, reaching out to these newest arrivals beginning the long road to citizenship seems like one of the best gifts possible.

Help for Afghan refugees

Since the fall of Kabul, Afghanistan, on Aug. 15, some 38,000 Afghan refugees have been placed in communities across 46 U.S. states. Tens of thousands more are being housed on U.S. military bases, awaiting placement.

These families have fled for their lives from the Taliban. Family members had been assisting U.S. forces in Afghanistan in numerous ways, including as translators, as well as working as humanitarian workers and women’s rights advocates. If they had not escaped, they would have lived in fear of retribution from conquering Taliban forces.

The refugees have arrived with few possessions.

“We didn’t bring anything but ourselves,” one young male refugee told a Minnesota television station. “Everything was left behind. We just come in one pair of clothes and a pair of shoes – that’s it.” So far, 438 Afghan refugees have arrived in Minnesota, including many families with children.

Americans across the United States, remembering that they live in a nation of immigrants, are stepping up to help. In Washington state, a group called Viets for Afghans is helping some of the 1,200 Afghans already arrived, with more on the way. The father of Jefferey Vu, a member of the group, fled to the U.S. from Vietnam in 1975 when U.S. troops pulled out at the end of the Vietnam War. “That history sticks with me today. It’s full circle,” Mr. Vu, an engineer at Boeing, told the Los Angeles Times. “In America, you can pay it forward. ... That’s what we hope to do.”

The U.S. government’s efforts to settle Afghan refugees are headed by Operation Allies Welcome. The website Welcome.us offers suggestions on how ordinary Americans can help. They include donating to a local resettlement organization (found by ZIP code on the website) or by giving to the Welcome Fund, which donates to community groups around the country.

Unused airline miles can be donated to cover the cost of bringing Afghan refugees to the U.S. If someone is able to supply temporary housing to a family, the site explains how to go about it.

Businesses can offer job opportunities or donate supplies such as household goods, diapers, and baby formula. Individuals are shown how they can form sponsor circles in their communities. These groups help refugees with basic tasks, such as finding housing, getting children into school, searching for employment, and myriad other needs.

Helping fulfills an important promise to an American ally, something both U.S. political parties see as vital. “The United States pledged to support those who served our mission in Afghanistan,” three GOP senators wrote in October. “Failing to do so would lead allies and adversaries alike to call into question our reliability and credibility as a partner in future conflicts.”

Many refugees are being settled in areas that have shrinking populations and labor shortages, away from major cities. “This is not only the right thing to do – it will enrich our communities and strengthen our economy,” Democratic Sen. Amy Klobuchar told The New York Times:

Qadiri, a new arrival who along with his family has been helped by Mr. Vu, is eager to get started on his new life. “Soon, I need to work,” he says. “That is the American way – work hard and good will happen.”

At this season of giving, reaching out to these newest arrivals beginning the long road to citizenship seems like one of the best gifts possible.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

When tragedy strikes

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Sandy Sandberg

God doesn’t send or cause calamity; rather, opening our hearts to God’s wholly good nature and presence inspires strength, peace of mind, and healing.

When tragedy strikes

Tragedies seem to happen all too often. For instance, recently devastating storms struck the Midwest region of the United States, resulting in injuries as well as deaths. In one case, a 5-month-old baby died when his parents’ house was destroyed. The parents survived; the baby didn’t. The news report of this loss was particularly heartbreaking.

When such tragedies have occurred, the questions are often asked, “Where was God when all this happened? It’s so unfair that such innocence would be destroyed. Was God absent? Did God allow it?”

There are no quick, easy answers, especially for those who have suffered losses like this. But as we wrestle with these kinds of questions and feel God’s love and care more tangibly, there are answers that can truly help us grow spiritually. The darkest hour is just before the dawn.

The Science of Christianity provides such answers. Mary Baker Eddy, the Discoverer and Founder of Christian Science, was well acquainted with tragedy and loss in her own life. In the depths of despair and suffering, she discovered the laws undergirding Christ Jesus’ healing mission, and she went on to share this discovery with the world in her book “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures.”

At one point in this book she wrote: “This is the doctrine of Christian Science: that divine Love cannot be deprived of its manifestation, or object; that joy cannot be turned into sorrow, for sorrow is not the master of joy; that good can never produce evil; that matter can never produce mind nor life result in death. The perfect man – governed by God, his perfect Principle – is sinless and eternal” (p. 304).

Clearly, this perfect, eternal man (a term that includes everyone) that Science and Health refers to is not a mortal, vulnerable to disaster. It’s our true, spiritual identity as God’s children. In the midst of devastation and destruction the physical senses are presenting, it’s easy to lose sight of the spiritual fact that God, Spirit, is the Life of us all. This divine Life is ever present, enabling us to recognize the permanence of Life, our inseparability from Life, which can never be lost.

This truth is what was behind Christ Jesus’ comforting words: “Peace I leave with you, my peace I give unto you: not as the world giveth, give I unto you. Let not your heart be troubled, neither let it be afraid” (John 14:27).

In this human experience, good and evil, life and death, love and fear, health and disease, appear to commingle and fight with each other for ascendancy. But Christian Science, based on the life and teachings of Christ Jesus, is here to reveal the wonderful spiritual reality that God alone is supremely powerful and ever present; that God’s nature includes only good; and that as the Bible puts it, God is “of purer eyes than to behold evil” (Habakkuk 1:13). As God’s children, made in His spiritual image, or reflection, we are inseparable from our creator.

Christian Science doesn’t promise that we won’t go through trials. But as I’ve experienced in my own life, we can rely on its promise that as we learn more of God’s true nature, and of everyone’s nature as God’s spiritual idea, we will realize more fully the peace, strength, and harmony that God has bestowed on everyone. Science and Health explains: “When we wait patiently on God and seek Truth righteously, He directs our path. Imperfect mortals grasp the ultimate of spiritual perfection slowly; but to begin aright and to continue the strife of demonstrating the great problem of being, is doing much” (p. 254).

I’ve been heartened to hear about countless people who, in the wake of disaster, have come to help their neighbors out of deep love and compassion. As we gain, through prayer, a clearer sense of God’s love, presence, and power, we find the hope, strength, and peace that come from realizing that life can never truly be lost and that divine Love prevails – and this enables us to help others who have suffered great loss find comfort, too.

A message of love

Ferried to safety

A look ahead

Thanks for joining us today. And you may have noticed that Chile is seeing a lot of change in recent months. Over the weekend, Chileans elected their youngest modern president, which you can read more about in this story. Also worth noting is our earlier story about Chile’s Indigenous people getting a seat at the table in rewriting the constitution.