- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- Ukraine battles another Russian threat: misinformation

- How updating a 135-year-old law could help save US democracy

- For Arab Israelis left out of tech jobs, a new code: Inclusion

- ‘You are not alone’: Love For Our Elders offers embrace via letters

- Five romance novels celebrate belonging, friendship, and food

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Watching for wins that bring new hope

Some Super Bowl fans – especially in Cincinnati – were hoping their team would end a 33-year dry spell on Sunday. Instead, pro football’s Cincinnati Bengals lost a close one to the Los Angeles Rams.

But for viewers looking closely, the Super Bowl venue in Inglewood, California, still showcased a small win – for climate action. While all big stadiums require a lot of pavement for parking, SoFi Stadium’s green urban landscape also includes a 5.5-acre lake that collects rainwater.

And while one promising (and costly) structure won’t shift society to a mindset of hope on climate change mitigation, it might begin to address a kind of anxiety that can be immobilizing.

“Future industrial development is on track to be cleaner than past industrial development,” writes journalist Matthew Yglesias, “even without any new policy changes or technological breakthroughs.”

And a study on “positive tipping points,” unpacked last week in The Guardian, looked at how “small interventions” by “small groups” can build and deliver social change as they gather critical mass and start delivering economies of scale.

“I wanted to show that, if you understand the complexity,” said a professor who worked on the study, “it can open up windows of opportunity to actually change things.”

Consider inroads by electric cars, or plant-based meat alternatives. Consider stadiums with lakes or gardens. The new becomes the norm. As Mr. Yglesias writes, “It’s worth trying to dispel the sense of helplessness.”

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Ukraine battles another Russian threat: misinformation

Ukraine isn’t dealing just with Russian troops on its borders. It also faces a constant misinformation campaign targeting the hearts and minds of Ukrainians that it is struggling to manage.

With international tensions running high around the possibility of a Russian invasion of Ukraine, the country’s counter-misinformation efforts have a renewed sense of urgency. For even as Russian troops amass along Ukraine’s borders, Moscow is laying out a propagandist case to win over Ukrainians, via persuasion or misinformation, Western experts say.

Russia’s strategy in Ukraine is best summed up as “hybrid warfare.” The toolkit is varied, mixing conventional warfare with propaganda, disinformation, misinformation, fakes, front political movements and parties, and cyberattacks.

“The military part is actually a very small part of Russia’s hybrid war,” says Alya Shandra, editor-in-chief of the Euromaidan Press newspaper. “The main battle space is not on the ground. It’s in the mind. All these troop movements aim to create a picture in our minds, so we think a certain way and then behave a certain way.”

It seems to have had some success in persuading Ukrainians. A December poll found that 30.3% of respondents in Ukraine wish to do away with the country’s “external governance” by the West, and 25% wish to restore economic ties with Russia.

Ukraine battles another Russian threat: misinformation

The United States worries a false flag attack against Russia, supposedly by Ukraine, will be used by Moscow to justify an invasion. British intelligence frets over a coup plot that would put a pro-Kremlin government in Kyiv.

For those on the front lines of Ukraine’s information war with Russia, these tropes are deeply familiar. They go back to when Russia annexed Crimea and Moscow began a multipronged campaign against Ukraine.

“Russia propaganda tries to persuade the world and their own population that Ukraine is preparing an offensive against Donbass [the pro-Russian rebel regions in eastern Ukraine] or against Russia, and that Russia has a legal and moral right to start their own offensive in response to the actions of the Ukrainian government,” says Ruslan Deynychenko, executive director of StopFake.org, a Ukrainian fact-checking website.

“The disinformation that we observed in 2014 is pretty much the same as the one we see right now,” he says. The parallels in tone and volume of disinformation efforts then and now – buttressed both by official statements and crude “fake” videos circulated on social media – trouble Mr. Deynychenko. He and his team are working round-the-clock to promote media literacy and debunk false information circulated by pro-Kremlin media.

Russia’s strategy in Ukraine is best summed up as “hybrid warfare.” The toolkit is varied, mixing conventional warfare with propaganda, disinformation, misinformation, fakes, front political movements and parties, and cyberattacks.

With international tensions running high around the possibility of a Russian invasion of Ukraine, the country’s counter-misinformation efforts have a renewed sense of urgency. For even as Russian troops amass along Ukraine’s borders, Moscow is laying out a propagandist case to win over Ukrainians, via persuasion or misinformation, to its own way of thinking, Western experts say. And that could shape the outcome of an invasion just as much as conventional arms.

“This is all part of a broader, orchestrated campaign against Ukraine and also against the West, to show that ‘Ukraine is our sphere of influence,’” EU foreign affairs spokesperson Peter Stano says. Russian President Vladimir “Putin is escalating this. Until recently, it was only disinformation and cyberattacks, but now he is also using real military force.”

“The main battle space is not on the ground”

The threat of conflict is serious enough that civilians across Ukraine have packed emergency kits or sacrificed their weekends to train for a possible attack. NATO boosted its forces in Eastern Europe – the U.S. has ordered an additional 6,000 troops to Romania and Poland this month. That pales in comparison with the 130,000 troops Russia deployed around Ukraine.

There was not this much military posturing before the annexation of Crimea and subsequent establishment of two pro-Russian statelets in Ukraine’s Donbass region in 2014. That’s part of the reason that experts in Kyiv say such a public show of force by Russia has more complex motives.

“The military part is actually a very small part of Russia’s hybrid war,” says Alya Shandra, editor-in-chief of Euromaidan Press, an internet-based English-language newspaper named after the 2013 pro-European protests that overturned a government more closely aligned with Moscow.

“The main battle space is not on the ground,” she says. Ms. Shandra has studied thousands of Russian official communications on Ukraine that were leaked by Ukrainian hackers in 2016-17. “It’s in the mind. All these troop movements aim to create a picture in our minds, so we think a certain way and then behave a certain way.”

Countering Russia’s mind games is as essential as countering its military moves, she argues. And not just for the sake of Ukraine, as many tactics the Kremlin tests on its neighbor are later used against the West.

Many believe the short-term goal of the buildup is to get concessions from the government in Kyiv and from NATO, the Western military alliance that Ukraine would like to join. All the saber rattling has certainly been terrible for Ukraine’s economy. The long game is bringing Ukraine back under the control of Moscow.

“It’s not a conventional war like the wars of the 19th or 18th century where a country would just invade and occupy a part of another country,” adds Ms. Shandra. “It’s something larger that has the ultimate goal of drawing Ukraine back into the Russian sphere of influence, by force, by trickery, by coercion, by persuasion, by different means.”

These strategies took shape during the Soviet Union when the goal in Moscow was to spread communism across the world. Because the Soviet Union was weaker than the West, it had to rely on trickery, she argues. That context spawned “reflexive control theory,” a term coined by Vladimir Lefebvre. The Soviet equivalent of game theory, reflexive control theory is, at its essence, the art of manipulating opponents into acting in your (or in this case, Russia’s) best interest.

“It takes just five minutes to produce a fake”

Russia has already “succeeded” in getting some of what it has wanted, Ms. Shandra says. Its power posturing around Ukraine allowed it to secure a meeting with U.S. President Joe Biden and demand an end to NATO’s expansion of the last few decades.

And it has presented a real threat to Ukraine, which the West must take seriously. “We shouldn’t underestimate the possibility for Putin to intervene [in Ukraine],” says Olexiy Haran, professor of comparative politics at the National University of Kyiv-Mohyla Academy. “Putin is testing the West, to see to what extent the West will be firm.”

It also appears to have had some success in winning over Ukrainians to its perspective. A December poll found that 30.3% of respondents in Ukraine wish to do away with the country’s “external governance” by the West and 25% wish to restore economic ties with Russia.

“Putin is saying, ‘Let’s make Ukraine neutral, non-bloc,’” points out Mr. Haran. “We were non-bloc before 2014. Nevertheless, Putin attacked us.”

That makes Ukrainian defenses all the more important.

Some of those are virtual. Serhiy Prokopenko, head of the National Coordination Center for Cybersecurity at the National Security and Defense Council Staff of Ukraine, says there has been increased Russian-suspected cyberactivity since October. While not all of them become public, cyberattacks have become larger, more targeted, and more complex. The Russian threat “is constant” as these cyber operations are an integral part of Russia’s hybrid war, but Ukraine has learned from experience.

“The cyber operations that they conduct are driven by the goals of information operations,” he says. Depending on the target and type of attack, the message could be as simple as NATO is weak, or the government is unable to protect citizens’ data.

And Kremlin-linked misinformation remains a critical problem for organizations like StopFake.org and EUvsDisinfo, the flagship project of a task force set up by the European Commission to counter Russia’s disinformation campaigns.

About 40% (some 5,200 of 13,500) of the cases identified and debunked since EUvsDisinfo’s creation in 2015 concern Ukraine. The tempo picked up in March 2021, when Russian military movements also triggered a war scare.

“It takes just five minutes to produce a fake,” says Mr. Deynychenko of StopFake.org. “Sometimes it takes weeks or even months to debunk that fake.

“In the business of creating fakes, the limit is your fantasy. You can say anything. To find the truth and find persuasive evidence of true facts is sometimes very difficult.”

How updating a 135-year-old law could help save US democracy

Reforming the process for counting electoral votes has bipartisan support, but still faces hurdles. Lawmakers must balance federal and state power, and guard against creating new vulnerabilities.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

-

Noah Robertson Staff writer

Key members of Congress from both parties are at work on a serious effort to reform the Electoral Count Act, which governs the official counting of Electoral College votes and naming of the new president-elect. Poorly written and vague in important spots, the 1887 law was tested by then-President Donald Trump with his post-vote efforts to overturn Joe Biden’s legitimate victory.

Some reforms already appear to be supported by many of the lawmakers working on the effort. The role of the vice president in opening and “counting” votes needs to be clearly defined. Raising the threshold for congressional objection to a state’s votes is another obvious fix.

Beyond that, things get complicated. The obvious changes deal with Congress. But what about the states? Each sets rules for its own certification of Electoral College votes. If Congress’ hands become more tied, will that make it easier for states to manipulate the process?

“Solving this problem inherently requires trade-offs,” says Matthew Seligman, a fellow at Yale Law School who has studied the Electoral Count Act for years. “Different people are going to make different judgments about what the most important risks are.”

How updating a 135-year-old law could help save US democracy

One of America’s last-ditch defenses against attempts to subvert presidential elections is a rickety 135-year-old antique.

This ancient structure – an 1887 law called the Electoral Count Act – governs the official counting of Electoral College votes and the naming of the new president-elect. But it’s poorly written and vague in important spots. Then-President Donald Trump tested its strength with his post-vote efforts to overturn Joe Biden’s legitimate victory.

Now key members of Congress from both parties are at work on a serious effort to reinforce and perhaps expand the law. Sen. Joe Manchin, the centrist West Virginia Democrat whose opposition blocked broad voting rights legislation earlier this year, says he backs electoral count reform and that it will “absolutely” attract enough GOP support to pass the Senate.

Mr. Trump’s attempts to exploit Electoral Count Act “ambiguities” were “what caused the insurrection” at the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021, Senator Manchin said in a broadcast interview last week.

At least two key hurdles remain, however. One is politics. If Democrats try to use this reform to pass parts of their defunct voting bill, they could lose GOP support needed to overcome a Senate filibuster. Or if Mr. Trump hammers the bill enough, it’s possible he could intimidate key Republicans into backing away.

Another, perhaps deeper, problem is getting the balance in Electoral Count Act reform right. At issue is the inherent tension between federal and state power in the American system. Both Congress and the states play key roles in the post-vote counting and certification of presidential winners. Tightening rules on only one side of this equation may leave holes on the other, or even create new vulnerabilities.

“Solving this problem inherently requires trade-offs,” says Matthew Seligman, a fellow at Yale Law School who has studied the Electoral Count Act for years. “Different people are going to make different judgments about what the most important risks are.”

“Widespread consensus” the law needs clarifying

Congress passed the original Electoral Count Act, or ECA, in response to the disputed 1876 election between Samuel Tilden and Rutherford B. Hayes. This vote, perhaps the most chaotic in U.S. history, was marred by claims and counterclaims of fraud and disputes over multiple slates of electors from key swing states.

It took 10 years to draw up the bill, given the disputes surrounding the issue, and the end result was inevitably loaded with internal contradictions, unsatisfying compromises, and dense language. Its primary section is one 830-word block of text, says Dr. Seligman. One sentence has 23 commas and two semicolons.

Parsing its meaning is difficult. And it left holes the unscrupulous might try to exploit.

“They can’t plan for everything and so there’s no question that 140-odd years later, we’re looking back and saying, well they didn’t account for this or that,” says Derek Muller, a professor of law and election law expert at the University of Iowa College of Law.

Reforming the ECA was not originally a Democratic priority. Instead, President Biden and congressional allies pushed to pass broader voting rights legislation meant to block GOP moves to tighten election rules in many states, among other things.

That didn’t pass, in part because of opposition from Democratic Sens. Manchin and Kyrsten Sinema of Arizona.

Now key Democrats have joined with Republican counterparts such as Sen. Lisa Murkowski of Alaska in a bipartisan group to deal with ECA reform – and through that, the larger problem of potential election subversion.

“I think there’s fairly widespread consensus that the Electoral Count Act needs to be clarified,” said GOP Sen. Susan Collins of Maine in a Monitor interview last week.

Jan. 6 is what lies behind that “widespread consensus.” Then-President Trump pushed then-Vice President Mike Pence to overturn the ratification of Mr. Biden’s victory, or at least refuse to certify the Electoral College votes of key swing states, due to baseless charges of fraud. Vice President Pence refused to do so.

Mr. Trump also pressed swing state governors and legislators to refuse to certify their own results, but no key officials did. Trump supporters from seven states submitted fake electoral vote certificates to Congress, to no avail.

Will that line hold next time? Imagine this scenario: the governor of a swing state refuses to certify a presidential victory in their state in 2024, citing unsupported fraud allegations. That governor certifies an alternate slate of electors instead. Then, the U.S. House of Representatives votes along party lines to accept those alternate votes. That’s all that’s needed for them to be counted under the current ECA, according to Dr. Seligman, though courts might possibly try to block the action. He called this scenario “The Swing State Governor’s Gambit” in a recent report.

Imagine further that the election is close enough that one state determines the winner, as it did in 2000.

Reforming the ECA to clearly block this or other dangerous hypothetical scenarios “could be extraordinarily helpful,” says Dr. Seligman.

“I think events of the type that we saw in 2021 are low probability and I hope it remains that way,” he says. “But it’s also something where if it went sideways, then it’s absolutely catastrophic.”

“You can’t plan for every contingency”

The first steps toward reforming the creaky ECA are straightforward and appear to be supported by many of the lawmakers working on the effort. They are designed to directly address much of the drama that swirled around the congressional certification of President Biden’s victory on Jan. 6.

For one thing, the role of the vice president in opening and “counting” votes needs to be clearly defined. Most experts believe the ECA, court interpretations, and a century of precedent already block a vice president from unilaterally overturning results or rejecting electoral counts from individual states. But the language is archaic and vague. It should be rewritten to sharpen the point that the vice president is, in essence, simply a master of ceremonies for certification.

If that had been done prior to this year it could have stopped the conservative lawyer John Eastman, Mr. Trump, and others from arguing that Mr. Pence had the power to block or delay the process.

“There would have been no question that Vice President Pence did not have any authority to alter the results of the election or halt the receipt of the counts from [the] states,” says Senator Collins.

Raising the threshold for congressional objection to a state’s Electoral College votes is another obvious fix. Currently, if one senator and one representative question a state’s slate, lawmakers are forced to debate the objection for hours. That’s a recipe for mischief and delay, say experts.

ECA reform could raise the bar for objections to a one-quarter or one-third vote of each chamber. It could set the requirement for sustaining an objection to a supermajority.

But much beyond this, things get complicated. The obvious changes deal with Congress – the ECA is basically a law that governs congressional procedures, after all. But what about the states? Each sets rules for its own certification of Electoral College votes. If Congress’ hands become more tied, will that make it easier for states to manipulate the process?

Mr. Trump’s strategy to overturn the election involved direct pressure on the states, with his phone calls to governors and other state officials. The phony elector certificates sent to Congress were not official in any way – they were basically just roundups of Trump supporters.

In another complicated scenario, what if, following a disputed election, a state has two different slates of electors claiming legitimacy – one approved by the legislature, and the other by a governor of a different party? Or what if a legislature and governor combine to simply overturn a state result neither likes?

Sen. Angus King, an independent representing Maine, has proposed that it might help to clarify that federal courts can get involved and settle such disputes before the deadline at which state certifications must be final.

Other experts have urged Congress to tweak legal language that allows state legislatures to choose electors if their state “failed” to make a choice on Election Day – making clear that something like a natural disaster that physically prevents the election would qualify, but not a dispute about fraud allegations.

Congress also should be wary of doing too much, or giving states incentives to change their own laws in ways that would allow them to get around a reformed Electoral Count Act, says Professor Muller.

America’s election system was tested in 2020, but it survived, he says. No states overturned their elected delegations. No challenges to certification in Congress succeeded.

“There are worries and concerns we might have, but you can’t plan for every contingency,” he says.

Staff writer Christa Case Bryant contributed to this report.

For Arab Israelis left out of tech jobs, a new code: Inclusion

As the Israeli tech sector took off, young Arab citizens were at a disadvantage. New moves to correct that inequity offer benefits to all: a bigger slice, and a bigger pie.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

The high-tech engine fueling Israel’s “Start-up Nation” reputation has left behind the country’s largest minority. Palestinian Arab citizens who are 21% of the population account for just 2% of workers in the tech sector.

It’s a lot to miss out on. Although the sector, which last year brought in a record $25.6 billion in investment, employs just under 10% of the Israeli workforce, it accounts for about 15% of the country’s gross domestic product.

To find jobs, connections matter. Jewish Israelis, many of whom know each other from elite tech units of the army, are linked in social and professional networks. But efforts are being made to lessen Arabs’ competitive disadvantage.

Some organizations are seeking to place Arab workers in tech jobs; others seek to bring tech companies to Arab towns. The latest national budget includes $188 million to help add Arab engineers to the sector.

While that initiative aims to increase the standard of living in the Arab community, it could also help the tech sector address a critical labor shortage that is threatening growth.

“Companies cannot grow because they cannot hire,” says Amir Mizroch, who works with tech companies and their investors. “Unless Israel manages to produce a broader base of tech talent, we will be overtaken by countries who have bigger populations and better education systems. That’s a problem.”

For Arab Israelis left out of tech jobs, a new code: Inclusion

When Wasim Abu Salem was a 14-year-old boy in Nazareth, he wanted to learn how to code more than anything. But there were no courses in his city, and he hardly knew anyone in the local Arab community who worked in computers.

Today he’s 30, with a dual degree in computer science and law. And he’s the founder of Loop, a coding academy for youth, currently serving mostly Arab kids in Israel ages 7 to 18 – a program he created for the current generation since it had not existed for his.

He’s also the co-founder of Altooro, a new startup whose platform recruits and trains software developers.

“I love the idea of creating something that provides value for people and solves problems,” says Mr. Abu Salem, sitting in a conference room in a shimmering high-rise in Tel Aviv.

The building, owned by Google, provides office space for early-stage startups. Upstairs there’s a roof-deck overlooking the city and a lounge with low couches and orange chairs.

Mr. Abu Salem is one of a tiny minority of Israeli tech workers who are Arab citizens, according to government data just 2% of the celebrated tech sector that last year brought in a record investment of $25.6 billion, and one of an even more minute number who themselves have become entrepreneurs.

Taking a quick break in the lounge with him is Ahmad Gbele, 26, a senior software developer for Altooro who went on almost 50 interviews before finally breaking into the industry six years ago.

“I didn't have the connections. I couldn't get referrals. I was not part of the ecosystem that came with being part of the tech community,” says Mr. Gbele.

Untapped resource

Israel prides itself on being referred to as “Start-up Nation,” but the high-tech engine fueling its economy has left behind the country’s largest minority: Palestinian Arab citizens who are 21% of the population. And this just as Israel faces a major shortage of computer engineers and other tech workers that may range as high as 6% of its tech workforce.

As elsewhere, connections matter in Israeli tech culture. News about jobs spreads through social and professional networks of Jewish Israelis, many of whom know each other from elite tech units of the army, military service that also gives them invaluable job experience before entering the civilian workforce.

That is beginning to change. One organization, called itworks, has brought 4,500 Arab workers into tech jobs since 2008. There have also been efforts to bring tech companies to Arab cities and towns, including by the Jewish-Arab run Tsofen organization, most of which are far from the greater Tel Aviv tech epicenter.

Notably, the budget recently passed by Israel’s inclusive new government includes $188 million for a five-year plan to add Arab engineers to the tech sector – in hopes of increasing the community’s standard of living and boosting coexistence in Israeli society as a whole.

Although the tech sector employs just under 10% of the Israeli workforce, it accounts for about 15% of the country’s GDP and 43% of exports. And sector jobs pay on average $98,000 a year, more than twice that in the economy as a whole. It’s a very big opportunity to miss out on.

A bigger piece of the pie

Meanwhile changes are afoot in Arab society, which for decades has lived mostly apart from Jewish Israelis, both geographically and socially, and often was viewed with suspicion. Recently, however, Palestinian citizens of Israel have become increasingly integrated, economically and politically, and outspoken in demanding equal rights.

It was Raam, the first Arab party in a government coalition, that demanded that funding for integrating Arabs into the tech economy be earmarked. A growing number of Arab university students are majoring in computer science and related fields, even though the community’s growing middle class has gravitated toward careers in more traditional fields, especially medicine, over what seems like the risky and less accessible tech sector.

And help is also coming from the entrepreneurial class.

“Companies just don't know how to integrate them,” says Ifat Baron, referring to Palestinian Israelis. She’s the founder of itworks, which connects companies and recent Arab graduates with tech degrees by breaking down some of the cultural and practical barriers they face.

Itworks sponsors trainings for aspiring Arab engineers, pairing their coding know-how with experience on projects to help overcome the competitive disadvantage of not having served in the army’s elite tech units. Itworks also helps improve participants’ English and Hebrew skills, and assists in resume writing and interview preparation.

Potential employers, too, are briefed on cultural differences. “In our day-to-day we Jewish Israelis don’t usually meet Arabs,” Ms. Baron says.

Coming from a more traditional, hierarchical society, for example, can lead Arab candidates to downplay their own skills and ask fewer questions during interviews.

Filling the demand

Lian Mansour, from Kaukab Abu El-Hija, an Arab village in the Galilee, is something of a cultural whisperer for itworks. She shepherds graduates as they job hunt, advising them on how to convey confidence and negotiate for a good salary, and checking in with companies for feedback after interviews.

“So many Arab graduates have the potential and the ability,” she says, but need support in order to even reach the interview stage. She’s seen graduates with top grades spend months trying to find work even though the industry is facing a looming crisis, with a fluctuating shortage of as many as 21,000 computer engineers.

Israeli companies have been outsourcing jobs to countries like Ukraine and Poland to meet the gap.

Citing the billions of dollars invested in Israeli tech last year, Amir Mizroch, a communications adviser who works with Israeli technology companies and their investors, says, “It smashed all records by far, but companies cannot grow because they cannot hire. … So the question is: How do they grow and scale?

“In the short term they look to places like Ukraine, but long term, unless Israel manages to produce a broader base of tech talent, we will be overtaken by countries who have bigger populations and better education systems. That’s a problem.”

He bemoans that Israel has been overly reliant on what he calls the “narrow funnel” of the army as the main training ground and accelerator into tech.

The Israel Innovation Authority has warned that without a surge in homegrown Israeli tech workers, “Israel's economy will reach a dead end and get stuck.”

Shifts in Arab culture

Sireen Nijeem Kayyal grew up as a student who excelled in math and science in a small Arab village near the northern seaside city of Acre. She stunned her parents when she rebuffed their plans for her to become a doctor, what they saw as the natural and socially acceptable choice for someone with her grades, and instead chose to major in engineering. At the time there were no other engineers in her village.

Her father was so upset with her decision that he refused to attend her graduation from The Technion, Israel’s equivalent of M.I.T., in nearby Haifa. Her three siblings have all gone into medicine.

“It became my challenge to prove to myself, my parents, my community that I could do this, that I could become part of Israel’s high-tech sector,” says Ms. Kayyal, now 30.

With mentoring from itworks she secured her first job and most recently a management position at a solar power firm. Her shares of stock in the company helped her and her husband buy an apartment.

Her father, she says, is now proud of her success.

Mr. Abu Salem, founder of the coding academy, says he thinks the pandemic has helped change the way Arab parents see their children’s possible future in the tech economy.

“Parents started to understand the importance of technology, that it’s part of our lives,” he says. “And they started to hear about the high-tech scene and its opportunities, including potential positions and also how much money is there.

“So they started to encourage their kids to go and study computer science and related fields. There’s been a shift in the mindset.”

Marwa Igbaria is 25, from the northern Arab town of Umm al-Fahm. She’s grateful her parents were supportive of her when she left home to study computer science at Tel Aviv University. At the time, in her class of 500 in the computer science department, there were only 10 other Arab women.

Today she’s one of the only Arabs in the Tel Aviv start-up where she’s working as a front-end developer. At first, she says, she was apprehensive about being one of the only Arab employees.

“I thought: How will I cope? But they’ve welcomed me so well, I’ve become friends with my co-workers,” she says. “I feel like I’m working with family.”

Difference-maker

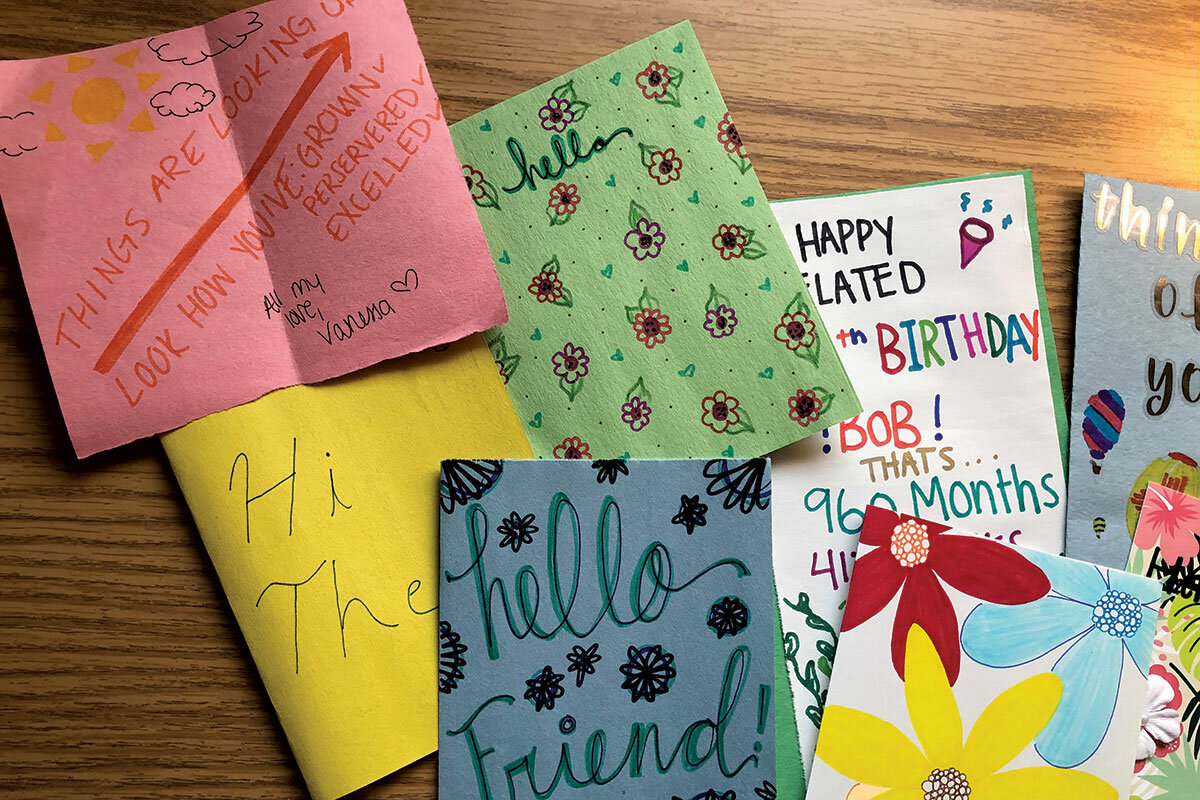

‘You are not alone’: Love For Our Elders offers embrace via letters

Older people are among the most isolated during the pandemic. Online tools to stay in touch often leave them behind. One group is using an old-fashioned way to keep them company from a safe social distance.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

In middle school, Jacob Cramer volunteered in nursing homes in the suburbs east of Cleveland, and he soon realized he was some residents’ only frequent visitor. His desire to remedy the loneliness and his fascination with the old-fashioned pen-on-paper handwritten letter meshed: He created Love For Our Elders, which advertised on the internet the opportunity to send letters to people in nursing homes.

Today, the organization, headquartered in his Yale dorm room, has 13 volunteers connecting 60,000 volunteer letter writers from more than 70 countries with older people around the globe. The organization has sent about 250,000 letters since 2013 and promotes Feb. 26 as National Letter to an Elder Day.

LaVonne Birge, in her 90s and isolated in her Omaha, Nebraska, nursing home, received a basket of 500 letters via the organization last Thanksgiving, filling her small room with greetings, stories, and voices. Many people wrote that they were praying for her. One woman described an ongoing battle to defend her geraniums from the neighborhood opossum. The underlying message in all the letters was the same: Mrs. Birge was not alone.

The experience has altered her perspective: “She says this absolutely, 100% has restored her faith in humanity,” says her granddaughter Beth Swierczek.

‘You are not alone’: Love For Our Elders offers embrace via letters

Beth Swierczek remembers long afternoons as a little girl when she and her grandmother, LaVonne Birge, would sit on the couch opening the letters Mrs. Birge would receive from far-flung relatives, friends, and pen pals. Passing the letters back and forth, they would smile and laugh.

Those days seemed far away last Thanksgiving. Mrs. Birge, who is in her 90s, sat alone in her nursing home in Omaha, Nebraska. It was a typical pandemic day: The nursing home was locked down, and Mrs. Birge was isolated.

Then came a knock at the door. It was Mrs. Swierczek and her daughter, Emily, allowed in briefly because they are family. They were carrying a wicker basket stuffed with letters, about 500 of them, addressed to Mrs. Birge.

The coronavirus created what AARP dubbed “an epidemic of loneliness” among older people, who have often found themselves quarantined and isolated.

However, thousands of volunteers around the world – connected through the organization Love For Our Elders – have responded with a simple but powerful gesture: writing a letter.

Puzzled at first, Mrs. Birge opened envelope after envelope, postmarked from the United States and abroad. The small room filled with greetings, stories, and voices.

Many people wrote that they were praying for her. One woman described an ongoing battle to defend her geraniums from the neighborhood opossum. Someone from Scotland sent a seed that is a symbol of good fortune.

The underlying message in all the letters was the same. Mrs. Birge was not alone.

A grandfather’s legacy

It’s a little surprising that the headquarters of the operation sending thousands of letters to hundreds of older people around the world is in the Yale dorm room of Love For Our Elders founder Jacob Cramer. What’s more surprising is that he started the operation as a junior high school student.

“It makes me really happy to help others, and I just wanted to do something that would hopefully help people smile,” he says.

Love For Our Elders, which Mr. Cramer runs with 13 other volunteers, many of them young people, connects some 60,000 volunteer letter writers from more than 70 countries with older people around the globe in need of a pick-me-up.

Love For Our Elders’ volunteers have sent about 250,000 letters since 2013, and it promotes Feb. 26 as National Letter to an Elder Day.

The idea that grew into Love For Our Elders started with Mr. Cramer’s grandfather, Marvin “Marv” Cramer. As a child, Jacob Cramer was at his grandparents’ house on all the Jewish holidays and nearly every weekend in between.

He credits his grandfather for teaching him values like gemilut hasadim, Hebrew for “acts of love and kindness”; tikkun olam, “repairing the world”; and a firm handshake.

After his grandfather died in 2010, Mr. Cramer wanted to live those values, so he started volunteering in assisted living facilities in the suburbs east of Cleveland where he lives.

As he spent more time at the nursing homes, he began to realize that he was some residents’ only frequent visitor.

“That really made me uncomfortable, and I think when you’re uncomfortable, you want to do something about it to change it,” Mr. Cramer says.

So, he did.

A P.O. box and a pandemic

A digital native raised in an era of texts and email, Mr. Cramer had always been fascinated with actual handwritten letters. Back in 2013, he combined the old art of pen on paper with new technology, advertising on the internet the chance to handwrite letters to people in nursing homes.

It took off. Within a year, he needed to buy a P.O. box to handle all the letters he was processing and delivering.

When the pandemic hit, many older people needed a connection to the outside world more than ever, but at the same time, there was a “huge increase” in the number of people who wanted to write, Mr. Cramer says.

“Being able to make a difference from home feels great because not only are you helping people feel loved, but you also don’t have to get off of the sofa ... or risk spreading the virus,” he says.

Phoebe Clark, a college student studying psychology at Loyola University Maryland, is one of those new pandemic volunteers.

Living with her parents after the pandemic closed her college, she witnessed her own grandfather’s struggles with dementia.

“My grandfather had mentioned that he feels forgotten, and that bothered me when I went back [to school],” says Ms. Clark, who joined a Love For Our Elders chapter on campus.

While older people may have become more isolated during the pandemic, their life experiences and perspective make them more resilient than most young people, says Michiko Iwasaki, a psychologist specializing in older adults at Loyola University Maryland who advises the college’s Love For Our Elders club. Still, she adds, there is no substitute for human connection.

“Human beings are very social animals,” Dr. Iwasaki says.

Love For Our Elders has been adapting to increase its human connections. It used to collect generic letters and send them in bundles to be passed out at nursing homes. Last year the organization shifted to personalized letters. It features individual elders for a month on its website. But with each recipient now averaging more than 300 letters, the organization is trying to feature more nominees each month to “spread the love.”

Faith in humanity

Lisa Campbell and Lance Lugar know better than most the value of the written word. The two met and formed a friendship while poring over historical documents at the University of Pittsburgh library archives where they worked. When Ms. Campbell moved away about a decade ago, the two kept in touch, often by mail.

“Before you had a computer and you could just backspace everything, there was a lot of emphasis on thinking about your message,” says Ms. Campbell, who is a Love For Our Elders letter writer.

Dr. Lugar, who has a Ph.D. in paleobiology, says he is not lonely. He has friends from around the world he keeps in touch with, but the pandemic made it harder to see them, and he has recently needed to use a wheelchair he calls “the battleship.”

Ms. Campbell decided he was a perfect candidate for Love For Our Elders. He was featured on the website in December, and soon Ms. Campbell showed up at his door with hundreds of letters.

People write about all sorts of things, though Love For Our Elders asks writers to avoid anything political or controversial, and many focus on common experiences or an interest from the online biography. Dr. Lugar chuckles when he describes one letter covered in dinosaur stickers, a nod to his background in paleontology.

Back in Omaha, Mrs. Birge still has plenty of letters to read, but the experience has already altered her perspective: “She says this absolutely, 100% has restored her faith in humanity,” Mrs. Swierczek says of her grandmother.

Books

Five romance novels celebrate belonging, friendship, and food

Valentine’s Day isn’t just about couples or romantic love. It can also include the bonds among friends, families, and even communities. This group of novels answers the call for connection.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

-

By Stefanie Milligan Correspondent

Romance novels reflect a deeply human longing to look outside oneself, find ways to connect, and end isolation. That makes them universal, as well as popular: Romance was the second-bestselling genre of fiction after general adult fiction in 2021, and sales rose significantly during the first year of the pandemic, according to Fortune magazine.

A hand-picked quintet of novels, set in a variety of cultures, offers realistic portrayals of individuals who are sometimes in conflict, but who are always journeying toward acceptance and love. It’s also noteworthy to find many male characters represented as genuine, intelligent, and thoughtful.

And for the foodies out there, you’ve hit the jackpot – these stories revolve around everything from tantalizing donuts and spicy Indian dishes to Nigerian specialties and international delicacies. Whether this is clever cross-marketing or not, having a little something to nosh on while reading them certainly adds to the enjoyment.

Five romance novels celebrate belonging, friendship, and food

Reading a good romance novel need not be a guilty pleasure. The longings for connection, for happy endings, for overcoming loneliness and isolation are universal desires. So there’s no reason to hide that novel under a more “serious” piece of literature. And fans of this genre are legion: Romance was the second-bestselling genre of fiction after general adult fiction in 2021, and sales rose significantly during the first year of the pandemic, according to Fortune magazine. Hundreds of blogs are devoted to romantic stories, in which the genre is further subdivided into specialty audiences.

This year as we mark Valentine’s Day – which florists, chocolatiers, and greeting card companies would try to convince us is only about romantic love – we look to widen the scope to include not only couples, but also friends, families, and even whole communities.

These novels, set in a variety of cultures, offer realistic portrayals of individuals who are sometimes in conflict, but who are always journeying toward acceptance and love. It’s also noteworthy to find many male characters in these books who are represented as genuine, intelligent, and thoughtful.

And for the foodies out there, you’ve hit the jackpot – these stories revolve around everything from tantalizing donuts and spicy Indian dishes to Nigerian specialties and international delicacies. Whether this is clever cross-marketing or not, having a little something to nosh on while reading them certainly adds to the enjoyment.

Charming confection

Julie Tieu’s debut novel, “The Donut Trap,” is a sweet confection with real substance. The story, whose universality will appeal to readers nostalgic for their own youth, also takes on specificity as Tieu explores the dynamics of a Chinese Cambodian American family. The Tran family owns Sunshine Donuts, near Los Angeles. College grad Jasmine, known as Jas, feels like a failure, “back at square one, living with my parents and helping out at the shop, as if college never happened.” Her spirits are buoyed by Alex, an old college crush; the return of her brother, Pat; and putting her work dreams into action.

Tieu’s story sparkles with flirty banter (between Jas and Alex) and exasperated parent-child exchanges, until finally healing avenues of communication open up. Readers will witness what it means to be a first-generation American coping with immigrant parents. The novel, in which forgiveness is a beautifully resonant theme, evokes empathy and understanding.

Ambitious podcaster

In Uzma Jalaluddin’s “Hana Khan Carries On” – which will be adapted into film by Mindy Kaling and Amazon Studios – Hana is a smart and ambitious 20-something South Asian woman living in Toronto. Her dreams of becoming a broadcast journalist are just beginning to take flight with her anonymous podcast, “Ana’s Brown Girl Rambles.” Too busy for a boyfriend, Hana interns at a radio station and serves customers at her family’s failing halal restaurant. She is shocked when a new, hip Indian restaurant moves in nearby.

Jalaluddin successfully re-imagines the 1995 rom-com “You’ve Got Mail,” setting it within a loving Muslim community that is facing racism. Hana’s texting friendship with her loyal podcast fan, StanleyP, competes for her heart’s attention with her intriguing rival Aydin, son of the new restaurateur. Hana reaches our hearts with her desire “to tell diverse stories that made a difference, that framed personal narratives in a way that allowed people to think about the world in a whole new light.”

Love letter to two cultures

“Love, Chai, and Other Four-Letter Words,” Annika Sharma’s captivating debut in “The Chai Masala Club” series, is a stunning love letter to New York City and Indian culture told through a heartwarming, interracial love story.

Indian American biomedical engineer Kiran Mathur falls for her charming new neighbor, Nash Hawthorne, a white Tennessean and child psychologist. The two enjoy getting to know each other on adventures around the city, checking off items on their bucket lists, a tradition started by Kiran’s three best friends – who are her family in America. Kiran is mindful that her parents, who were told by village elders to disown her older sister in India for marrying outside their caste, will be vehemently opposed to her new relationship. She and Nash ultimately face ancient Indian cultural beliefs that would keep them apart. Still, she summons resourcefulness and patience to restore broken family ties. This enchanting novel feels like one beautiful soul-searching conversation.

Finding self-acceptance

In Lizzie Damilola Blackburn’s “Yinka, Where Is Your Huzband?” British Nigerian Oxford graduate Yinka Oladeji is up for promotion at the investment bank where she works. But when her mum and aunties publicly humiliate her at her sister’s baby shower and during a church service by sending up “the prayer of the century,” for God to grant Yinka a “huzband,” Yinka unravels. Losing her job next, and not interested in entering the dating market, she bumps into her old boyfriend, now engaged to a woman with lighter skin than Yinka’s. Cut to Yinka throwing herself into a secret plan to find a date to an upcoming wedding by updating herself (with nods to “Bridget Jones’s Diary”). The story is packed with humor, drama, and good-hearted characters. Yinka’s genuine faith and wish to remain a virgin until marriage are refreshing. She finds success when she faces her fears and rejoices in her authentic self, truly accepting her father’s words, “Yinka, you’re beautiful. ... Remember, the midnight sky is just as beautiful as the sunrise.”

Friendship by post

Kim Fay travels back to the 1960s in “Love & Saffron: A Novel of Friendship, Food, and Love,” in which two women correspond through letters, reminiscent of “84, Charing Cross Road.” Immie lives on Camano Island, near Seattle, with her husband and writes a column for Northwest Home & Life. A younger writer and travel enthusiast named Joan sends a gift of exotic saffron to Immie, and a friendship for the ages is born. Through sisterly, often hilarious letters, they share recipes, hopes, and dreams, and lean on each other during difficult times, such as the Cuban missile crisis and John F. Kennedy’s assassination. In Immie, Joan finds a confidant when she falls in love with a widower. Delicious food, wonderful characters, and adventures abound in this delightful story that simmers with affection.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Appealing to Russia’s better nature

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

For decades, whenever Russia sought transparency on what other countries in Europe were doing with their militaries, it often turned to a little-known institution created during the Cold War. The 57 member states of the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe are bound together to keep the Continent “whole and free.” Now with a flurry of diplomatic activity to prevent a possible Russian invasion of Ukraine, the OSCE may be center stage in keeping the peace.

Last week, Ukraine asked the OSCE to discuss the issue of Russia not living up to its agreement about military transparency. As is its right under OSCE rules, Ukraine wants detailed explanations of Russia massing more than 130,000 troops along the Ukrainian border.

Ukraine’s move was a subtle move. It plays to its neighbor’s past pursuits for peace and confidence-building in Europe, whether it is transparency in military maneuvers or risk reduction through arms control pacts. Russia is more complex than the simple narrative of a bully. Appealing to its better nature could be as persuasive as threats of severe sanctions.

Appealing to Russia’s better nature

For decades, whenever Russia sought transparency on what other countries in Europe were doing with their militaries, it often turned to a little-known institution created during the Cold War. The 57 member states of the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe are bound together to keep the Continent “whole and free.” Now with a flurry of diplomatic activity to prevent a possible Russian invasion of Ukraine, the OSCE may be center stage in keeping the peace.

Last week, Ukraine asked the OSCE to discuss the issue of Russia not living up to its agreement about military transparency. As is its right under OSCE rules, Ukraine wants detailed explanations of Russia massing more than 130,000 troops along the Ukrainian border.

“If Russia is serious when it talks about the indivisibility of security in the OSCE space, it must fulfill its commitment to military transparency in order to de-escalate tensions and enhance security for all,” tweeted Ukrainian Foreign Minister Dmytro Kuleba.

Russia is expected to boycott any OSCE meeting on the matter. Yet Ukraine’s move was a subtle move. It plays to its neighbor’s past pursuits for peace and confidence-building in Europe, whether it is transparency in military maneuvers or risk reduction through arms control pacts. Russia is more complex than the simple narrative of a bully. Appealing to its better nature could be as persuasive as threats of severe sanctions.

As Europe’s top security body, the OSCE may be the best forum to deal with Russia’s concerns about a possible expansion of NATO. The Vienna-based organization is one of the few bodies in which the United States and Russia are voting members. And it is already heavily involved in Ukraine. For nearly eight years, its observers have monitored a cease-fire between government forces and Russia-backed separatists in the eastern region.

An invasion of Ukraine by Russia could lead the OSCE to evict it. One reason: Members are obligated not to view any part of the OSCE region as a sphere of its influence. Eviction from the OSCE would curb, if not end, the Kremlin’s ability to shape Europe’s security by peaceful means.

On Feb. 15, the current chair of the OSCE, Polish Foreign Minister Zbigniew Rau, is scheduled to visit Moscow. His will be the latest effort to persuade President Vladimir Putin not to invade Ukraine. He may also remind Mr. Putin of his country’s history of relying on a body designed around principles that have helped keep the peace on a continent with a long history of wars.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Waltzing with Love

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 1 Min. )

-

By Moriah Early-Manchester

We can never be separated from the graceful, empowering rhythm of God – divine Soul, infinite Love itself – that moves in us, as this poem conveys.

Waltzing with Love

Moving in uninterrupted harmony

in Soul’s time – Soul never missing a beat, never stumbling out

of line;

in Love’s time – Love whose steady rhythm pulses through.

You are the dancer in Love’s waltz.

If you’re ever alone and watching, with wishful eyes, the dancers

swaying before you,

Love, drawn to the suffering heart, beckons,

“Come, dance with Me.”

This hand of grace, this call of Soul, dissolves the weight

of stubborn resistance

and lifts you to your feet, gently whispering, “I lead. You follow.”

Pain released, fear absorbed,

the anxious drumbeat of the heart is stilled with the steadiness

of Soul’s rhythm.

Boldness strengthens the timidity of your steps.

Resolve quells the hesitancy of your movements.

You are Love’s dance.

You are Soul’s rhythm,

moving in uninterrupted harmony.

Originally published on sentinel.christianscience.com, Dec. 17, 2021.

A message of love

Celebration: A family affair

A look ahead

Thanks for starting your week with us. Come back tomorrow. The West has promised unprecedented sanctions against Russia should it invade Ukraine. But we’ve heard that before, and Russia has persevered. Would this time really be different? Fred Weir reports from Moscow.