- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 9 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- Can Roberts steer Supreme Court safely through abortion case crisis?

- Lebanese vote shows demand for change. But enough to build on?

- Are US elections fraud-filled? One Georgia dispute is a window.

- Van life: How I’ve managed to let my son graduate with his class

- Green energy from sewage, and furniture from plastic waste

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

On Taiwan, Biden and his team introduce a different kind of ambiguity

President Joe Biden has this funny habit: He says what he thinks, even if he contradicts his own government’s policy. It happened again yesterday in Tokyo, when a reporter asked if he was “willing to get involved militarily to defend Taiwan, if it comes to that.” The question has fresh salience, given Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

“Yes,” the president replied. “That’s the commitment we made.”

For decades, U.S. policy on the China-Taiwan question has been one of “strategic ambiguity” – keep Beijing guessing on how the U.S. would react if China tried to take over the island it already considers its own. President Biden seemed to leave little doubt.

It’s the third time he’s responded to that question in this way. Each time, the White House has quickly asserted that policy hasn’t changed. Mr. Biden and his team performed this two-step on another matter twice in March. First, he called Russian President Vladimir Putin a “war criminal,” a term with legal implications. The spin: He was just “speaking from the heart.” Days later, he said Mr. Putin “cannot remain in power.” Not a call for regime change, the White House said.

As a senator, Mr. Biden was famous for gaffes. And remember in 2012, as vice president, when he scooped the boss and said he favored same-sex marriage? The issues today are literally life and death, and Mr. Biden is still telling us what he thinks. But now he’s commander in chief; the buck stops with him.

It may be that Mr. Biden still thinks like a senator, and has suggested as much. But as president, the off-script moments can make for an awkward dance that seems to undercut his authority.

“Presumably” these clarifications are done “with his permission or at least his acquiescence,” writes Peter Baker of The New York Times.

It’s also possible that there’s a benefit to operating this way, allowing the administration to say things out of both sides of its mouth. We’d like to know more about how this all works behind the scenes. In the meantime, our ears are peeled for more such moments.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

A deeper look

Can Roberts steer Supreme Court safely through abortion case crisis?

During his tenure, the chief justice has built a track record – though not a flawless one – of coherence and consensus. It’s being tested now as never before.

In his 17 years on the Supreme Court, Chief Justice John Roberts says he’s learned that “unanimous means 7 to 2.”

He made the darkly humorous quip at a judicial conference this month. Days earlier, a draft ruling overturning the right to abortion had leaked – the kind of ruling Chief Justice Roberts has spent much of his career trying to avoid.

The Supreme Court has marched steadily rightward during his tenure. Voting rights have narrowed, gun rights have expanded, and campaign finance laws have loosened, to name just a few jurisprudential trends. Almost every year since he joined the court, the question has been how Chief Justice Roberts protects its integrity amid crisis “X” or “Y“ – crises often tied to controversial cases.

No crisis has yet had long-term consequences for the court’s reputation, judging by polls at least. The court has, broadly speaking, kept moving under the speed limit and on the correct side of the road, thanks, in important moments, to the chief justice.

Overturning the right to abortion would be another matter entirely. And it is the greatest test to date of Chief Justice Roberts’ consensus-building bona fides.

“If you’re the chief justice, you’re remembered for what happened while you were chief justice,” says Kimberly Mutcherson, co-dean of Rutgers Law School. “We’re in very uncharted territory.”

Can Roberts steer Supreme Court safely through abortion case crisis?

What can a chief justice bring to the U.S. Supreme Court that an associate justice cannot?

In September 2005, John Roberts, then a nominee for that position, answered that he would “try to bring about a greater degree of coherence and consensus in the opinions of the court.”

“We’re not benefited by having six different opinions in a case,” he added. “The court should be as united behind an opinion of the court as it possibly can.”

The theory goes that a more united court earns more respect and deference from the public. Crafting an opinion that nine individuals can all agree on is also likely to result in a judicial consistency that won’t shift with changing political tides, or hare off too far and fast in a particular direction.

That should be a concern for all the justices, Chief Justice Roberts said in 2005. But the chief “has a greater scope for authority to exercise in that area,” he added, “and perhaps over time can develop greater persuasive authority to make the point.”

Over time, this doesn’t seem to have proved the case for him. In his 17 years on the court, Chief Justice Roberts says he’s learned that “unanimous means 7 to 2.”

He made the quip at a judicial conference earlier this month, The Washington Post reported, and it was a joke of the dark humor variety. Days earlier, a draft ruling overturning the right to abortion had leaked to the public – the kind of ruling Chief Justice Roberts has spent much of his career trying to avoid.

The Supreme Court has marched steadily rightward during his tenure. Voting rights have narrowed, gun rights have expanded, and campaign finance laws have loosened, to name just a few jurisprudential trends. Almost every year since he joined the court, the question has been how Chief Justice Roberts protects its integrity amid crisis “X” or “Y” – crises often tied to controversial cases and rulings.

None has yet had long-term consequences for the court’s reputation, judging by polls at least. The court has, broadly speaking, kept moving under the speed limit and on the correct side of the road, thanks, in important moments, to the chief justice. Recent examples include the Supreme Court’s decision affirming Congress’ right to investigate the president and that a sitting president is not immune to criminal investigation.

Overturning the right to abortion would be another matter entirely, however. And it is the greatest test to date of Chief Justice Roberts’ consensus-building bona fides.

“If you’re the chief justice, you’re remembered for what happened while you were chief justice,” says Kimberly Mutcherson, co-dean of Rutgers Law School in New Jersey. “We’re in very uncharted territory.”

The importance of private deliberations

The court is central to one of the three branches of government, albeit one that is unelected and with lifetime appointments, and as such, it’s important for institutionalists like Chief Justice Roberts that the court’s rulings don’t appear political. The best way to achieve that is to have as many justices as possible agree on an outcome.

That is not always possible, especially in complex and high-profile cases, but the chief justice has built a track record – though not a flawless one – of the coherence and consensus he identified during his confirmation.

Two years ago, for example, in the midst of the Trump presidency, Chief Justice Roberts wrote the majority opinion in two cases concerning the president: one affirming Congress’ power to investigate the president, and one regarding criminal investigations of a sitting president. In both, six justices joined his opinions. A year earlier, he authored a unanimous, albeit fragmented, ruling that blocked the addition of a citizenship question to the 2020 census.

In all those cases, it’s critical that these private deliberations remained private, experts say.

Behind each Supreme Court ruling are months of cloistered deliberations between justices and their clerks and between the justices themselves. Draft opinions, like the one leaked, and concurrences are circulated between the justices. Arguments might be adjusted, language tweaked, and, occasionally, votes switched.

“Our independent judiciary ... has to be insulated from public scrutiny of the decision-making process in individual cases,” says Roman Martinez, a partner at Latham & Watkins and a former clerk to Chief Justice Roberts.

If it isn’t, he adds, it “inevitably frays the degree of candor [justices] have when sharing ideas in deliberating a case. It increases suspicions.”

Of all the issues the Supreme Court considers, in the modern era the right to abortion has been the most fraught. But in the wake of a succession of leaks concerning the current abortion case, Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health, it’s possible that the court’s deliberative process has been damaged.

The leaks include a full draft opinion published by Politico, revealing that there are at least five votes among the justices to overturn the half-century-old constitutional right to abortion. It also revealed that the chief justice was not in the majority.

In a statement confirming the authenticity of the leaked draft, Chief Justice Roberts added that it “does not represent a decision by the Court or the final position of any member on the issues in the case.” No new drafts have been circulated since the leaked Feb. 10 draft written by Justice Samuel Alito, Politico reported.

But that could be because the justices are being more secretive around Dobbs, experts say.

“I’m thinking that there are revisions going around, but they’re not going to everybody,” says David Garrow, a court historian.

Bonds of personal affection

Since Justice Amy Coney Barrett joined the court in October 2020, cementing a conservative supermajority, court watchers have looked for evidence of strained relationships. But from the outside at least, normal service has resumed since the draft opinion leaked.

On Monday the court issued two opinions: a unanimous ruling in a technical employment arbitration case, and a 6-3 ruling – along ideological lines – that eliminated an avenue of appeal for death penalty inmates on the grounds of inadequate representation. The latter ruling continued a Roberts Court trend of favoring the government over criminal defendants. That tendency was also evident last week when, in another 6-3 ruling along ideological lines, the court further loosened campaign finance regulations.

There have been spiky opinions and dissents this term, particularly from the three Democrat-appointed justices, and particularly concerning the court’s increasingly active use of its emergency, or shadow, docket. And some court watchers believe a distance may have grown between the justices in recent years that won’t aid Chief Justice Roberts’ consensus-building efforts.

“The ordinary everyday interactions through which the justices build trust and knit together an institution have not been happening,” says Aziz Huq, a professor at the University of Chicago Law School and a former clerk to Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg. The court has been closed to the public since the pandemic began, for example, and the justices spent all of last term hearing oral arguments remotely.

When he clerked on the court in 2003-04, “the two most important friendships on the court” were between ideologically opposed justices, he notes: Justices Ginsburg and Antonin Scalia, and Justices Clarence Thomas and John Paul Stevens, respectively.

“I just don’t know if there are anything like those friendships on the court today,” he adds.

For evidence to the contrary, Mr. Garrow points to the court’s last oral argument session of the term, when Chief Justice Roberts paid emotional tribute to the retiring Justice Stephen Breyer.

“I doubt ever in Supreme Court history has a chief justice come that close to crying on the bench,” he says.

“To me that was powerful, powerful evidence [of] the bonds of personal affection that grow amongst them, completely apart from if they agree or angrily disagree with each other in case X or Y,” he adds.

“The biggest event ... since Brown”

Since Chief Justice Roberts joined the court, disapproval of the court has mostly hovered between 30% and 45%, according to Gallup – with a public approval rating far higher than Congress’. But recently that has begun to change. Last September, around the time the court let a controversial Texas abortion law stand with a short, unsigned opinion, disapproval of the court ticked up to 53%, Gallup found. From August 2019 to January this year, the court’s favorability rating dropped by 14 points, according to Pew. More recently, a May tracking poll by Politico and Morning Consult found that just 14% of respondents had a lot of confidence in the Supreme Court, with 16% having no confidence in the institution.

Whether the leak has harmed deliberations between the justices, or even harmed how the public views the court, experts say that what really separates this moment from previous legitimacy crises the court has faced is the Dobbs opinion itself.

When the Supreme Court established the right to abortion in Roe v. Wade in 1973 in a 7-2 ruling, it immediately ranked among the court’s most historic opinions. If the final Dobbs opinion overturns Roe, it will be equally, if not more, significant.

“If Dobbs comes out more or less where the Alito first draft was, this is the biggest event in the court’s history since Brown,” says Mr. Garrow, referring to Brown v. Board of Education, the case in which the Supreme Court banned segregation in public schools.

Famously, thanks to the intense charm offensive of Chief Justice Earl Warren, the Brown ruling in 1954 was unanimous, with no separate concurrences or dissents. In that vein, Chief Justice Roberts has talked about the institutional strength the court builds when it speaks with one voice, acting as “a Court – not simply an assemblage of justices.”

When the justices meet to discuss cases at weekly conferences, he reportedly lets the meetings run longer so there can be more debate. As the great Supreme Court advocate of his time, according to his colleague Justice Elena Kagan, he can make persuasive arguments to his fellow justices.

He has led by example, regularly writing fewer separate opinions than his colleagues each term. He has also often sought to avoid sudden, significant change in many areas of the law, including abortion.

Indeed, he is a conservative jurist, but Chief Justice Roberts’ institutionalist leanings have made him one of the few justices to change their vote in abortion cases. In 2016 he dissented from a ruling that struck down a restrictive Texas abortion law, but four years later he voted to strike down a similar Louisiana regulation. “I ... continue to believe that [Texas] case was wrongly decided,” but because that decision is now precedent, he wrote, the Louisiana law “cannot stand.”

Like many high-profile decisions during his tenure, that Louisiana ruling was 5-4. Big cases involving the Affordable Care Act, campaign finance, same-sex marriage, partisan gerrymandering, and the Trump-era travel ban have all been decided by one vote – and often with the chief justice in the majority.

“To do anything momentous by 5-4 leaves you in a vulnerable position, institutionally, moving forward,” says Mr. Garrow.

Overturning half a century of precedent, and eliminating a constitutional right that women have retained for generations, qualifies as momentous.

If Justice Alito’s draft opinion in Dobbs becomes the final opinion, it would transform the country overnight and immediately rank among the court’s most significant decisions of the postwar era. Would Chief Justice Roberts be satisfied being in the minority for such a ruling? Would he have a choice?

“Whatever vision he has about the legacy he wants to leave on this court, I think it has really slipped through his fingers,” says Professor Mutcherson.

The reaction, she adds, “is not going to be just, ‘I think this is a terrible opinion’; it’s going to be, ‘This is a terrible court.’”

In the Dobbs oral argument, Chief Justice Roberts proposed a compromise solution in which a Mississippi law banning abortion after 15 weeks of pregnancy is upheld without overturning Roe. Neither party has argued that in the case, and as of February at least, the date of the leaked draft opinion, there wasn’t much support for such a ruling among the justices.

“Multiple judges and justices have made it clear they think [Roe] should be got rid of,” says Ilya Somin, a professor at George Mason University’s Antonin Scalia Law School.

“It’s harder to shift minds on this issue than others because of how strong feelings are,” he adds. “But he’s a better judicial statesman than I, so he might be able to find a way.”

Lebanese vote shows demand for change. But enough to build on?

Changing an entrenched system requires energy. While some in Lebanon voted last week to break with the past, most still voted for sectarian parties, an indication of fear and fatigue.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

In Lebanese elections last week, pro-change candidates won a dozen or more seats in Parliament, and Hezbollah and its allies lost their majority. The result was lauded as a “breakthrough” by some Lebanese media, but it also showed the challenges of changing the political system when people facing chronic food and fuel shortages are worn down by the demands of survival.

Official voter turnout barely topped 49%, and some 90% of those who voted still chose traditional sectarian parties.

“A lot of people just didn’t vote, and that’s very sad,” says Nisrine Hammoud, who was among hundreds of thousands on the streets during Lebanon’s “October Revolution” in 2019. “When you know how much people are struggling ... it’s like, ‘Why ... didn’t you go vote?’” says Ms. Hammoud, now in her mid-20s and working in Beirut.

“Winding this back is going to take a long time,” says Maha Yahya, director of the Carnegie Middle East Center in Beirut. “In a deeply polarized country, you are going to have people vote for their sectarian leadership, even if they are unhappy with them, because fear-mongering works.”

Still, support for change candidates was nearly twice what had been predicted. “The numbers ... tell us there is a shift,” says Dr. Yahya. “The question is, will we build on it?”

Lebanese vote shows demand for change. But enough to build on?

With a Lebanese flag draped over her shoulders, and optimism for political change filling her heart, Nisrine Hammoud joined hundreds of thousands of her fellow citizens on the streets during Lebanon’s “October Revolution” in 2019.

“We feel like we are alive again,” she told the Monitor late one night at Beirut’s Martyrs’ Square back then, as protesters demanded the toppling of a political class renowned for corruption, and a total uprooting of the entrenched sectarian system that was leading to state collapse.

An election was the “only chance” to make such change, Ms. Hammoud said. “It’s up to us. It’s up to the people to decide if they are going to go back to their old ways, or we are going to go forward.”

That election finally came May 15, but with mixed results for activists like Ms. Hammoud. Pro-change candidates won a dozen or more of the 128 seats in Parliament, and Iran-backed Hezbollah and its allies lost their majority, dropping from 71 to 58 seats.

The result outstripped modest predictions for anti-establishment candidates, and so was lauded as a “breakthrough” by some Lebanese media. But it also showed the challenges of changing the country’s baked-in sectarian system at a time when people are worn down by the demands of survival.

Indeed, popular disgruntlement has grown even more widespread following the Beirut port explosion in August 2020, and the further disintegration of the economy and services that has now left more than 70% of Lebanese living below the poverty line.

The self-declared October Revolution and its street protests dissipated long ago, squelched by the COVID-19 pandemic, and then day-to-day preoccupations like coping with the lack of electricity, and chronic food and fuel shortages, activists say.

And yet, some 90% of those who voted last week still chose traditional sectarian parties, whose politicians – often political kingmakers for decades, who had emerged as warlords during Lebanon’s 1975-1990 civil war – have brought the nation to this state of collapse.

“The results are somehow shocking, because it’s not just about people who voted for the wrong people – a lot of people just didn’t vote,” says Ms. Hammoud, now in her mid-20s, about the low 49% turnout. “We needed people to actually take action. And that election was our only ticket ... to vote for people who are really going to represent us.”

A divided opposition

Though Lebanon’s chronic crises have caused deep despondency, analysts say, that did not translate into much support for change candidates, who were diverse and divided.

“They literally undermined each other, so anybody who wanted to vote for change ... didn’t have an address to go to,” says Maha Yahya, director of the Carnegie Middle East Center in Beirut.

She notes that 11 separate lists of anti-establishment candidates competed against each other in the northern Sunni Muslim-majority city of Tripoli, one of Lebanon’s poorest. An analysis by the Lebanon Broadcasting Corporation International found that, had the opposition been unified nationwide, it likely would have doubled its seats in Parliament.

Still, the dozen or so seats that change candidates captured are nearly twice the number that many had predicted before election day.

“There is a shift and a change,” says Dr. Yahya. “Now, how profound, and whether this is the beginning of genuine change that we can build on. The question is, will we build on it?”

Lebanon has been ruled for decades under a formula that shares seats of political power among parties linked to different religious groups, and citizens tend to vote along religious lines. “Winding this back is going to take a long time,” she says.

“If you are scared that Hezbollah is going to attack you, you run and vote for [Christian] Lebanese Forces, because you think they are the ones who will be able to stand up” and protect you, Dr. Yahya explains. “You are not going to overhaul a system like the Lebanese one overnight.”

The chief elections observer for the European Union, György Hölvényi, said the elections were “overshadowed by widespread practices of vote-buying and clientelism, which distorted the level playing field.” Observers from the Lebanese Association for Democratic Elections recorded 3,600 “flagrant violations” on election day, and said partisans of the two main Shiite parties, Hezbollah and Amal, attacked their observers.

The wrangling ahead

The impact of the vote will become clearer in the coming months. Parliament will first choose a new speaker – almost certain to be Amal leader Nabih Berri, who has held the post for 30 years already. Then it will face the much harder task of electing a government, whose top priority will be laws and changes required to comply with International Monetary Fund conditions for massive bailout funds.

“That means you really want to have a seat at the table – the stakes are much higher,” says Heiko Wimmen, a political analyst with the International Crisis Group in Beirut. Finding a win-win formula for all will be “extremely difficult,” he predicts.

On paper, the new cadre of change MPs “potentially could be kingmakers, but that would require a cohesive parliamentary bloc” and a common platform, which seems a distant prospect, Mr. Wimmen says.

He notes that an assumption made throughout Lebanon’s multiple crises has proved wrong. Many observers had believed that the situation for average Lebanese citizens would become so dire that the political elite would be compelled to change its behavior or risk a popular uprising.

In fact, politicians flaunt their wealth and power as brazenly as ever, and as people have grown more desperate and despondent, they “are less able to organize any kind of resistance,” Mr. Wimmen says.

Fatigued voters

And they are exhausted, Ms. Hammoud points out.

“People have been so distracted by other things, like getting food on the table,” she says. “For the past two years we have just been struggling to fill up our cars with gas, to be able to buy bread. We stood in queues for hours just to get things done, and now we have this electricity problem, and the Lebanese lira keeps devaluing against the dollar.”

Ms. Hammoud says that the anti-establishment candidates’ showing in last week’s elections feels to her like a pale reflection of the popular demand for change she felt on the street in 2019.

She knows she is in a minority, but she is not giving up.

Lebanon’s ruling warlord-politicians “stole our money, they stole our parents’ pension funds, and we have no electricity because of them; we have [nothing] because of them,” says Ms. Hammoud. Just keeping that reality in mind, she adds, “is always our motivation, because that’s the only way you can wake people up.”

Are US elections fraud-filled? One Georgia dispute is a window.

Elections are not exempt from human error. But wide-scale fraud in U.S. elections is exceedingly rare. A dispute in Georgia shows that.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Back in the summer of 2020, before Donald Trump ignited a national firestorm to “Stop the Steal,” a smaller conflagration consumed Long County, Georgia. A Republican probate judge lost his primary election by nine votes and sued, claiming fraud.

Local opinion was divided, according to Robert Parker, the chair of the Board of Commissioners. “Fifty percent thought the allegations were true. Fifty percent thought they weren’t,” says Mr. Parker, who works out of a windowless, wood-paneled office in Ludowici, the sleepy county seat.

But the case, which went all the way to Georgia’s Supreme Court, did not uncover any evidence of fraud. Rather, it turned up minor errors in how ballots were filled out or verified – the types of mistakes that crop up in every election. And as the protracted dispute showed, those errors can provide fertile ground for post-election challenges, which can easily snowball into allegations of fraud that undermine public trust.

“I knew what was the truth and what was not, and I wanted everyone to know,” says Mr. Parker, who is also chief of police in Long County. “Your election is your reputation. When you ruin it, you never get it back.”

Are US elections fraud-filled? One Georgia dispute is a window.

In Georgia’s Republican primary, there’s been no shortage of candidates echoing former President Donald Trump’s disproved electoral fraud claims and vowing to restore “election integrity.” Few, however, have what Jake Evans, a Trump-endorsed lawyer making his first run for Congress, is selling: direct experience litigating a 2020 election challenge.

“I contested an election in Long County, Georgia – and that revealed a lot of the widespread fraud we saw in 2020,” Mr. Evans said in a televised debate this month with his GOP primary opponents.

Mr. Evans, who is running in today’s primary for former House Speaker Newt Gingrich’s old seat in the Atlanta suburbs, represented a Republican probate court judge who sued after losing his primary election by nine votes, claiming fraud.

But contrary to the young attorney’s campaign claims, the case, which went all the way to Georgia’s Supreme Court, did not uncover any evidence of voter fraud. Rather, it turned up a handful of minor errors in how ballots were filled out or verified – the types of mistakes that crop up in every election, but that can nonetheless be used to toss out votes and potentially invalidate results in a close race.

Despite all the conspiracy theories surrounding the 2020 presidential election, multiple studies have underscored that fraud – especially on the scale required to sway a statewide or national outcome – is vanishingly rare in modern U.S. elections. President Trump’s top election and cybersecurity officials called the 2020 election the “most secure in U.S. history,” and his own attorney general concluded there was no evidence of widespread fraud. A review by The Associated Press last December of suspected 2020 voter fraud in Georgia and five other battleground states found fewer than 475 cases, of which virtually all involved individuals acting alone to cast extra ballots. Most of these ballots were spotted by clerks and not counted in vote tallies.

Yet back in the summer of 2020, before Mr. Trump and his allies ignited a national firestorm to “Stop the Steal,” a smaller conflagration consumed Long County, in southern Georgia. As the protracted dispute over its probate court race showed, clerical errors or database mismatches can provide fertile ground for post-election challenges in a close race – which can then easily snowball into vague allegations of fraud that undermine public trust in elections.

“We don’t have a problem with voter fraud in this country,” says Luke Moses, the lawyer who represented the winning candidate in the case. “What we have is a group of partisan individuals who don’t care what a voter’s intent is.”

In June 2020, Long County certified that Teresa Odum had won the Republican primary for probate judge by nine votes, beating incumbent Judge Bobby Smith. A recount turned up additional absentee ballots, but the margin of victory – and the result – remained the same. In a place where Republicans outnumber Democrats 4 to 1, that meant certain victory for Ms. Odum in November.

In response, Mr. Smith sued the county and Ms. Odum, claiming election fraud.

Robert Parker, the chair of the Board of Commissioners in Long County, says local opinion was divided on the merits of the case. “Fifty percent thought the allegations were true. Fifty percent thought they weren’t,” says Mr. Parker, who works out of a windowless, wood-paneled office in Ludowici, the sleepy county seat.

Mr. Evans, the Atlanta-based attorney who represented Mr. Smith, had a record of challenging election results. He was also a former chair of Georgia’s Ethics Commission and a young Republican activist whose father, Randy Evans, was a Trump donor who served as his ambassador to Luxembourg.

Over three days of court hearings in September, Mr. Evans formally challenged 30 votes out of 2,741 cast. Of the 30, six were found to be doubles: Voters had mailed ballots, then voted again on Election Day due to apparent confusion over which primary races in Georgia had already been held. One of the six said he voted twice intentionally. In addition, another voter had registered in the wrong county.

“We conceded that seven shouldn’t have voted,” says Mr. Moses, Ms. Odum’s attorney. “They needed to find two more.”

Mr. Evans challenged the other ballots over irregularities in ID checks and signature matches, but the court rejected all of the remaining challenges. With the exception of the intentional double voter, “there was no evidence that any of the voters or election officials knowingly acted with possible fraudulent or malicious intent,” a superior court judge wrote.

Irregularities occur in virtually all U.S. elections, because local election officials must interpret complex, shifting rules that can penalize voters if not followed precisely. In Georgia, voter registration applications must exactly match information held by state agencies; critics say this frequently leads to problems because of data entry errors or tiny differences in how names are written, such as missing hyphens.

Deciding whether legitimate ballots should be rejected over minor errors is a discretionary power that should be exercised with great caution, says Mr. Moses. He worries that minor irregularities will increasingly be used to toss out votes in other close-run elections. “If you don’t dot every ‘i’ correctly and cross every ‘t’ properly, your vote won’t count,” he says, which could further undermine faith in the electoral process.

Since 2020, a wave of election bills passed by Georgia and other Republican-run states have added new restrictions in the name of securing the vote. Republicans argue that emergency rules adopted in 2020 to facilitate voting under pandemic conditions, particularly no-excuse mail-in voting, were overly lax.

On Dec. 1, 2020, as Mr. Trump was ramping up the fight to overturn his electoral defeat in Georgia and other swing states, the court issued its verdict in Long County: Mr. Smith had failed to show evidence required to invalidate the election. Last year, Georgia’s Supreme Court upheld the decision by a 7-0 vote.

Mr. Smith declined to discuss his lawsuit. Mr. Evans didn’t respond to requests for comment.

To Mr. Parker, who is also chief of police in Long County, the outcome felt like vindication after all the mudslinging. At a time when public trust in the electoral process has been seriously undermined, he hopes rulings like this can help restore a sense of legitimacy.

“I knew what was the truth and what was not, and I wanted everyone to know,” he says. “Your election is your reputation. When you ruin it, you never get it back.”

Commentary

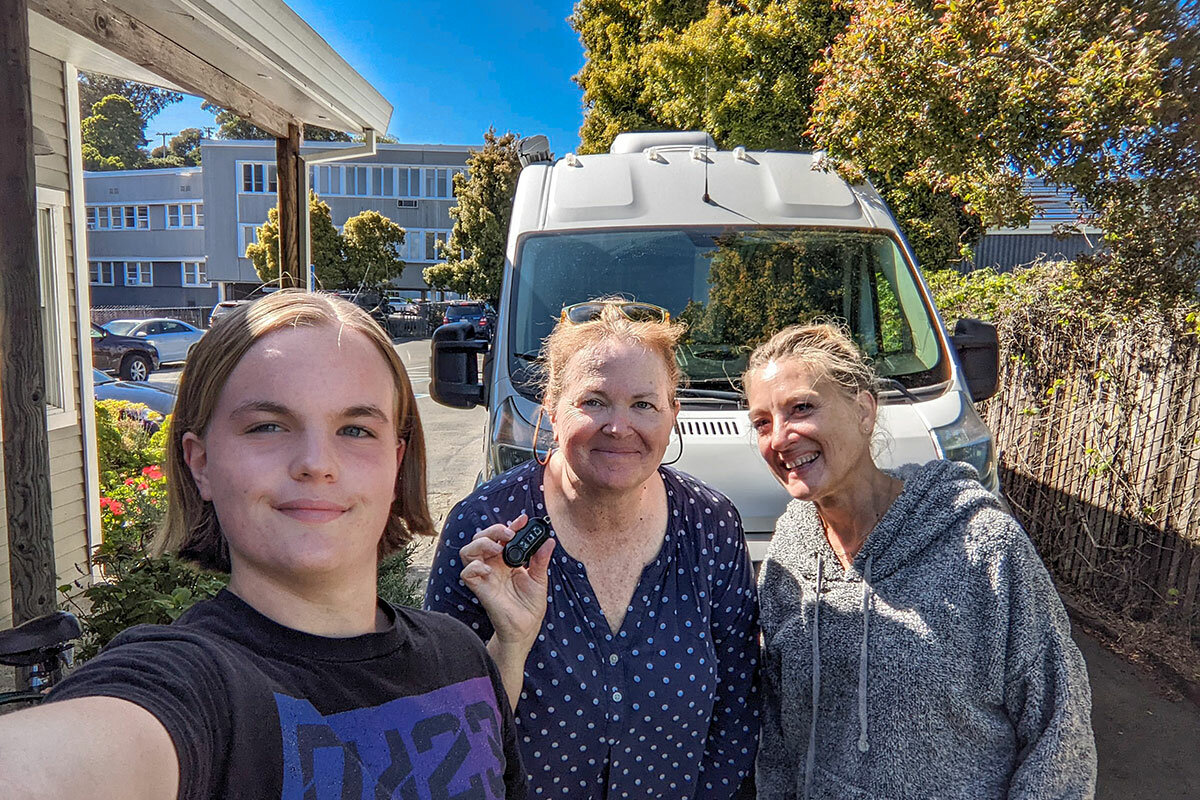

Van life: How I’ve managed to let my son graduate with his class

The affordable housing crisis in Northern California landed unexpectedly on our contributor’s doorstep. Through ingenuity, she is providing shelter for her family – and raising questions about the role of government.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

-

By Lisa Nuss Contributor

Lisa Nuss is a single mother with a 14-year-old son. Forced to move out of their rental home in Marin County, California, after the landlord died, she was unable to find affordable housing that would accept a child. In early May, she rented a van, where she and her son, Spencer, are living until the end of the school year so that he can graduate from middle school with his class.

On May 7, Ms. Nuss posted about her family’s situation on Nextdoor, an app that functions as a community bulletin board.

“We’ve been turned away from cottages and mother-in-law [places] ... because the owners won’t rent to children. ... I’ve also been trying since 2018 to get a ban on short-term rentals, but … there has been little interest in the community,” she wrote.

“I’ve been to every housing agency there is, [but] I make too much money to qualify for any assistance. ...

“I am asking for help in making [the van] warm enough to sleep in, and also asking for help in finding a place to shower. ...

“We are bearing witness to what it’s like in Marin in 2022. This is not a family-friendly environment. ... We are becoming Nomadland.”

Van life: How I’ve managed to let my son graduate with his class

Lisa Nuss is a single mother with a 14-year-old son. Forced to move out of their rental home in Marin County in California after the landlord died, she was unable to find affordable housing that would accept a child. As of early May, she and her son, Spencer, are living in a van until the end of the school year so that he can graduate from middle school with his class.

Ms. Nuss has a master’s degree in public policy and a law degree, both from the University of Washington. She has provided legal counsel for the state of Oregon and advised banks and corporations on risk management and regulatory issues. Since being laid off during the Great Recession, she has been freelancing as an analyst and writer on a variety of legal and financial topics.

Having grown up in what she describes as a “low-income family,” Ms. Nuss put herself through college and law school with the help of scholarships and loans. She has no inherited wealth.

Her words below, lightly edited for length and clarity, were posted May 7 on Nextdoor, an app that functions as a community bulletin board. (All of the locations she refers to are in Northern California.) After posting, Ms. Nuss received many offers to help make van life as comfortable as possible.

FAMILY NEEDS HELP CONVERTING A VAN INTO A SHELTER

Need help with heating – NOMADLAND HAS COME TO MARIN

Hi neighbors – Speaking of short-term rentals devastating our community, we have not been able to find a rental for $1,600 [per month] that allows children, and so we will be forced to live in a van until summer. I am asking for help in making it warm enough to sleep in, and also asking for help in finding a place to shower. There are of course already others in our community living in vans. Some are well employed like me. We need to help each other – we ARE Nomadland now.

Many, many people assume there’s some place out there for us – rest assured, after months of looking, there is not. We’ve been turned away from cottages and mother-in-law [places] in Sausalito, Mill Valley, and San Rafael because the owners won’t rent to children. Affordable housing advocates tell me this is illegal and asked me for names. I haven’t done that yet, as my focus is on finding shelter for my child, not punishing others. I’ve also been trying since 2018 to get a ban on short-term rentals, but … there has been little interest in the community. …

So this is the reality in Marin. When your landlord dies, like ours did, their children ALWAYS sell the house, and there is no longer any place to house your children. Yes, we see the writing on the wall and will have to relocate this summer – the nonwealthy can’t afford to raise their children here anymore. We live on my wages alone; that is no longer enough to support a family here, without relying on inherited wealth. However, I want my son to finish the middle school he’s been at for three years and graduate with his class. He deserves that – he is one of the top grade-earners at his school and always works hard to help others.

I tell our story so people know. To make a record. To bear witness. I’ve been to every housing agency there is – I make too much money to qualify for any assistance. The motel programs are only for the unemployed. My son jokes that he hopes the homeless in Sausalito will leave us their tents when they move into the hotel rooms that we don’t qualify for. I’m not saying we are any more deserving of shelter than those in the tent camps who are being given motel rooms – I am saying that people need to know there is no help for employed families who can’t afford $2,000 for rent.

I emailed the county supervisors to ask if they can act in this crisis – doing something outside the box, like declaring a state of emergency so that funds can be used to help working families have shelter. …

The whole housing assistance “framework” imagines helping the “needy” who are mentally ill and can’t function in normal society. I told the commissioners we aren’t “needy” and we are fully functioning, but it’s the society that is no longer normal. Our only choice left, if we want my son to finish out his last months of his middle school, is to sleep in our car until the summer, after which time we will be forced to relocate out of the area. We are surrounded by some of the wealthiest, most “successful” minds in our country, and yet we have our heads in the sand about this problem.

Can’t we activate the high-tech brilliance and set up small cargo containers or tiny yurts somewhere for families who have lived here for years and are being displaced? Local news is obsessed with helping the displaced Ukrainians, but not with stopping displacement of families right here, right now. [Instead], private builders everywhere here are throwing up “luxury” apartment towers … [with] studios that start at $3,000/month.

To our local [Supervisor Dennis] Rodoni’s credit, his office responded by asking yet another housing agency to contact me. (There are a lot of county employees drawing high incomes to “help” with housing, and yet I wonder if all that staff [is] really needed, since there is no housing.) Anyway, this woman from another county housing agency called me. I explained the situation and asked if she would clarify that there is in fact no assistance or temp shelter for an employed mother and her child who can’t find a place to rent for $1,600 in Marin or Southern Sonoma. Her reply: “You gotta understand living in Marin is very expensive – you could move to another place.”

So in order to allow my son to finish his middle school, we will be sleeping in our car very soon. A nice person is going to rent us her converted van, but she doesn’t know how to make the heating system work. It’s a Dometic Brisk II installed in the ceiling and might be controlled by a digital device on the wall. … We put our things into storage months ago – anticipating moving into a house, not a van – and so our winter clothes and sleeping bags are at the bottom of the storage unit. If anyone has wool long johns or cold-temperature sleeping bags to lend or sell cheaply, that would be appreciated.

We are bearing witness to what it’s like in Marin in 2022. This is not a family-friendly environment. This is not a progressive environment. … Anyone reading this is now interacting with a family that will be sleeping in their car. … I first moved to Mill Valley in 2003, when I rented two different, wonderful mother-in-law units. They are Airbnbs now, no longer available for a family or anyone to make their home. We are becoming Nomadland, which will get worse unless the community decides to do something about it.

Points of Progress

Green energy from sewage, and furniture from plastic waste

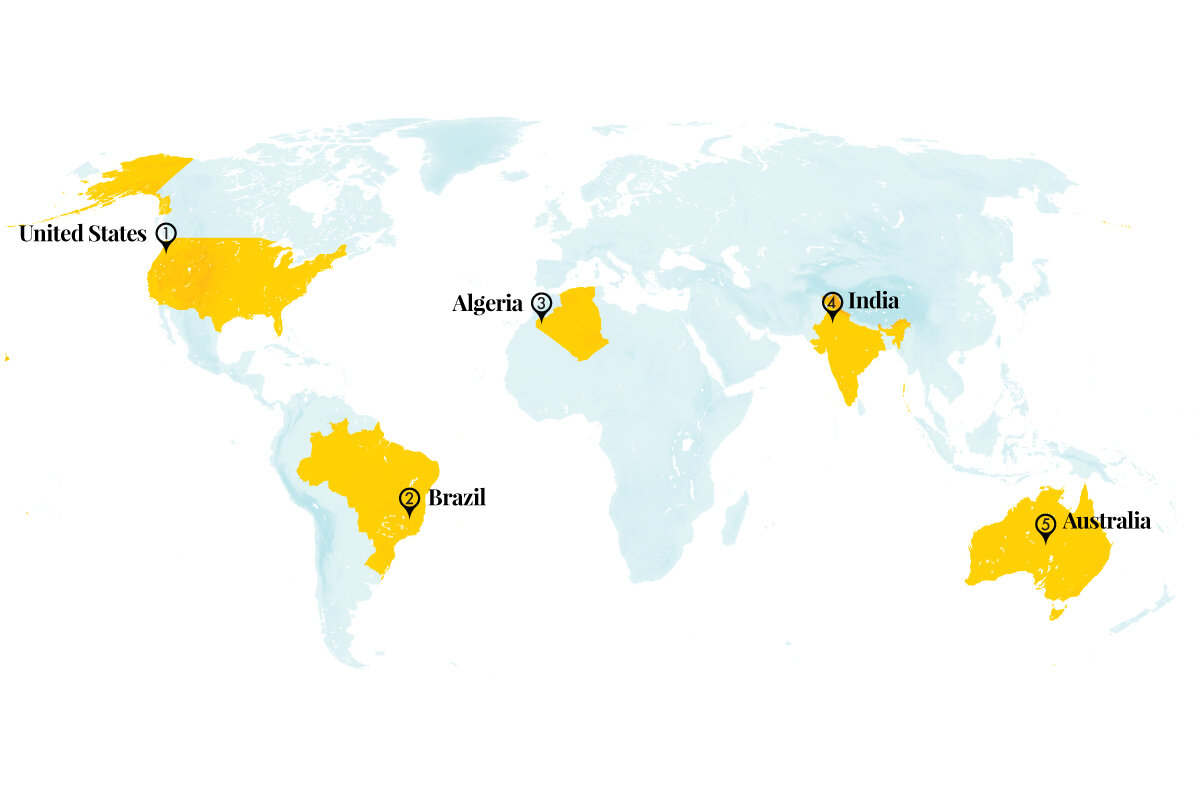

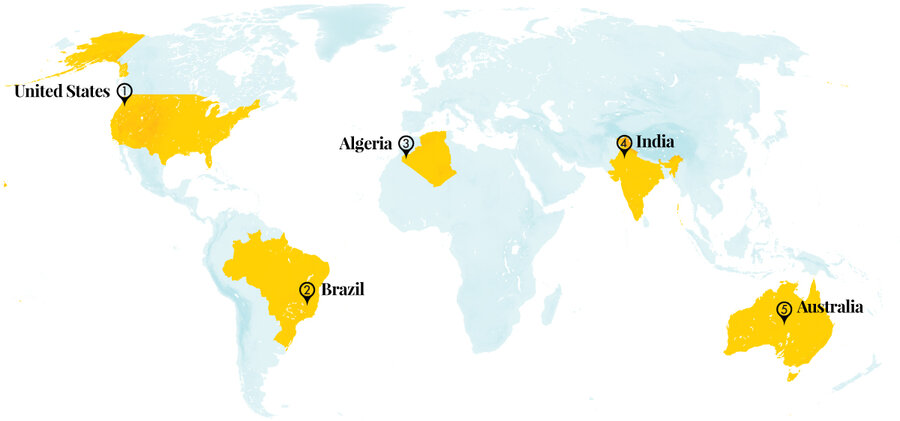

In our progress roundup, ingenuity and necessity play their parts: An Oregon community has financed a cogeneration water treatment plant for its growing population, and a Dutch nonprofit is helping refugees in Algeria manufacture sellable goods from the plastic littering their camp.

Green energy from sewage, and furniture from plastic waste

Solutions that address more than one issue at a time are happening on the local and national levels. Beyond Oregon’s Clackamas County sewage plant transformation, note how Australia’s government is funding more environmental protection with job creation for its Indigenous residents.

1. United States

An Oregon treatment plant is converting sewage into clean energy. Wastewater takes large amounts of energy to treat. But Clackamas County addressed the needs of its growing population with a system upgrade that uses human waste to make heat and electricity needed by the plant itself. The Tri-City Water Resource Recovery Facility adopted the sludge-to-energy model in August 2021. The process now heats five buildings on-site and provides half the facility’s electricity.

The wastewater is filtered and microbes break down waste to create “activated sludge.” In an anaerobic digester, microorganisms produce methane, which is transformed into heat and electricity with the help of a 600 kW lean-burn co-generation engine. Meanwhile, solids that get filtered out are used to make fertilizer for non-food crops in eastern Oregon. Providing water to 190,000 residents, the project cost the county $35 million, with support from the local public utility.

Reasons to be Cheerful

2. Brazil

Concerned citizens have planted over 2 million trees in southeastern Brazil since 2005. At first, the goal of the Conservador das Águas (Water Conservation) campaign was simple: Protect the water supply for a town of 35,000 in the state of São Paulo by restoring forest cover in watershed areas. By 2016, the efforts expanded into the Mantiqueira Conservation Plan, which has committed to a more ambitious goal of reforesting 1.5 million hectares (3.7 million acres) by 2030 across three states.

To encourage landowner engagement, the conservation plan supports local policymaking and technical training. The group was one of the first adopters of Brazil’s “payment for ecosystem services” model, whereby rural landowners are offered financial incentives to reforest land while also preserving existing forests, pastures, and soil. “If we don’t take care, the water will end in 20 or 30 years. We have to think about the future, our children and grandchildren,” said Helias Alves Cardoso, a landowner who has reforested 4 hectares of his property as part of the conservation project.

Mongabay

3. Algeria

Refugees in Algeria are designing furniture and other products out of plastic waste. Tens of thousands of Sahrawi people have lived in camps on the border between Mauritania, Morocco, and Western Sahara for much of their lives, with high levels of unemployment. So when the United Nations refugee agency called for ideas on tackling waste in the camps, Dutch nonprofit Precious Plastic offered its DIY recycling system as a way to tackle both problems.

The open-source organization supplied the necessary equipment, including machines that shred and clean the plastic before it’s melted and reshaped. “We had a few design sessions where we talked about what’s possible and how to use this plastic material,” said Joseph Klatt, managing director at Precious Plastic. “And then they were just super stoked on coming up with ideas that made sense to them [like] furniture styles that they’re used to.” Refugees who work at the recycling center plan to sell their products, including school desks, benches, chairs, and serving sets for tea, to local nongovernmental organizations. For now, the workers earn a salary from the U.N., but after the first year of operation, they will become partial owners of the facility.

Fast Company

4. India

Excluded from traditional village governance, Indian women are forming their own political assemblies. Village councils – called panchayats – are historically men’s groups. But during the height of the pandemic, more than a dozen women’s sessions took place in northern Indian villages, at first to debate the contentious issue of child marriage, and later expanding into other topics. Each meeting lays the groundwork for a charter of demands, which are submitted to local and state governments.

A recent gathering in the 10,000-person village of Mandkola led to the push for at least one high school for female students in each of the nearby districts. “I do not want my four younger sisters or the girls of this village to face what I currently face,” said Mahabali, a young woman from the village. “My only desire to participate in this program is to work for the betterment of women.”

Reasons to be Cheerful

5. Australia

Australia doubled the number of jobs available through its Indigenous ranger program. The initiative, which centers on Aboriginal land management, helps meet a wide range of “caring for Country” goals, including monitoring illegal fishing, conducting controlled burns, and protecting marine turtles. In its most recent budget, the federal government committed an additional $636 million (Australian; U.S.$460 million) to the program, first formed in 2007. One thousand rangers will be hired and 88 new ranger projects will begin around the country with the new funding, which extends until 2027. Some 800,000 Australians identify as Indigenous, about 3% of the population.

Beyond safeguarding ecosystems, the program places emphasis on economic empowerment for Indigenous communities. “We’re building the wealth of Aboriginal people and that wealth gives people the ability to plan for the future and to have the same choices as non Aboriginal people,” said Gail Reynolds-Adamson, a Nyungar woman from Western Australia, about the program. The federal budget includes separate funds to support Indigenous title holders and extend the Indigenous Home Ownership Program, alongside environmental research and protection.

The Sydney Morning Herald, The Guardian

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

The attraction to join clubs of democracy

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

One of Ukraine’s advantages in fighting the Russian invasion is that members of the world’s strongest “club” of democracies – NATO – are supporting it with training and weapons. That support, based on shared and transcendent values that bind democracies, was not lost on Sweden and Finland. In May, both of the once-neutral states applied to join NATO.

Now something similar may be happening in Asia. China’s growing military aggression against its neighbors has emboldened a relatively new club of four democracies in the Indo-Pacific region – Japan, India, Australia, and the United States – known as the Quad. On Tuesday, this values-based group held its second in-person summit since early 2021. More importantly, the Quad’s nonmilitary initiatives – aimed at ensuring a free and secure Asia – have begun to attract other countries to possibly apply for membership.

“Our cooperation is built on the values that we share – a commitment to representative democracy, the rule of law, and the right to live in peace,” says Australia’s new prime minister, Anthony Albanese. His words are an echo of the reasons given by Sweden and Finland to decide to join NATO.

The attraction to join clubs of democracy

One of Ukraine’s advantages in fighting the Russian invasion is that members of the world’s strongest “club” of democracies – NATO – are supporting it with training and weapons. That support, based on shared and transcendent values that bind democracies, was not lost on Sweden and Finland. In May, both of the once-neutral states applied to join NATO.

Now something similar may be happening in Asia. China’s growing military aggression against its neighbors has emboldened a relatively new club of four democracies in the Indo-Pacific region – Japan, India, Australia, and the United States – known as the Quad. On Tuesday, this values-based group held its second in-person summit since early 2021. More importantly, the Quad’s nonmilitary initiatives – aimed at ensuring a free and secure Asia – have begun to attract other countries to possibly apply for membership.

South Korea’s newly elected president, Yoon Suk-yeol, has expressed interest in his country joining the Quad in some role. And New Zealand, according to a few experts, could be open to membership. The country’s prime minister, Jacinda Ardern, is on a tour of the U.S. and hopes to meet with President Joe Biden.

One key strategy for America’s defensive role in Asia is its network of alliances and partnerships with democracies. “Because these relationships are based on shared values and people-to-people ties, they provide significant advantages such as long-term mutual trust, understanding, respect, [military] interoperability, and a common commitment to a free and open Indo-Pacific,” John Aquilino, commander of U.S. Indo-Pacific Command, told Congress this spring.

With four vibrant democracies coming together to form the Quad, he added, “it would generate concern for anyone with an opposite opinion.”

The Quad, however, is not a military alliance – although its members have conducted joint military exercises. And it does not present itself as a group that is ganging up on China. Rather it takes an affirmative, positive approach to expanding freedom, rule of law, and other values. At its latest summit, for example, it initiated a plan to use satellite images to prevent illegal fishing and to track the use of unconventional maritime militias – a tactic used by China to take over small islands.

“Our cooperation is built on the values that we share – a commitment to representative democracy, the rule of law, and the right to live in peace,” says Australia’s new prime minister, Anthony Albanese. His words are an echo of the reasons given by Sweden and Finland to decide to join NATO.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

God’s gift of grace

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Gloria Preston

Nobody is ever beyond the reach of God’s healing, saving grace, as a young student experienced after being attacked by a group of bullies for race-based reasons.

God’s gift of grace

When the world seems full of unrest and disrespect, grace can seem like a quickly melting candle, flickering out in a dark night.

But Christian Science links grace with Truth, a name for God. “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures” by Mary Baker Eddy states, “Grace and Truth are potent beyond all other means and methods” (p. 67). So grace isn’t something personally manufactured. It is in operation at all times, because it is an attribute of God. Therefore it occurs naturally in God’s creation and is available to anyone.

I grew up on an island where I was a racial minority, and people of my race were often bullied. I was grateful that, even though a Caucasian, I happened to look more like one of the native islanders and could speak the local dialect. So, on my first day at a new school, when I was invited to join a group of native kids, I was delighted.

Soon, though, I found that my new friends spent a lot of time bullying those of different races. I was afraid. If they knew I was actually one of these minorities, might they terrorize me, too? Regrettably, I was silent for several weeks.

Finally, I decided to do something about it. I brought a minority friend of mine to lunch, along with a plate of cookies that I hoped would appease my group of friends. However, the cookies went flying, and threats were made. On my way to the bus after school that day, I was set upon by kids from this group, who kicked me and beat me.

I had no idea how to escape. I reached out to God as best I could. My prayer was simple. I knew that God is Love; it said so on the wall of the Christian Science Sunday School I attended. And I had learned that Jesus understood God as Love, too. So, I just thought about God as Love.

I was on the ground and covering my head when I saw relief coming – the substitute bus driver. He immediately disciplined the kids in the group, but in a way that showed that he knew them to be better than the way they were acting. They responded with remorse as well as obedience and understanding. He then made sure I was all right. I felt that this wonderful man was seeing all of us in the same loving light. This was the grace of God shining through His creation.

God’s grace, as expressed by the bus driver, healed me and made my simple prayer light up a more spiritual love in me. I was instantly freed of hatred, and I felt filled with a sense of unity with all that is good. Fears for my own well-being vanished, and my courage to feel unity with all of God’s creation blossomed into peace.

With that peace came many later opportunities to prove the efficacy of expressing grace that sees each one of us as one with God, without exception.

Grace and good deeds were embodied in the life of Christ Jesus. The book of Luke says of Jesus, “The grace of God was upon him” (2:40). In Jesus’ life, grace took many forms, from a loving touch that healed the sick or a persuasive divine view that reformed the sinner, to a firm stand against the money-changers who were corrupting the holy purpose of the temple of God (see Matthew 21:12, 13). The grace that characterized Jesus saves us from the villainy that would try to divide us, diminish the impact of our lives, and erode our faith in what is right and good.

The Bible assures us, “Whatsoever is born of God overcometh the world” (I John 5:4). “The world” could refer to anything that wars against God’s loving purpose for His creation: goodness, harmony, and fellowship. It follows that grace and its attending qualities, being born of God, are able to overcome what would claim to be destructive.

God’s abundant grace is continuously expressed in His creation, reflected in qualities such as courage, patience, strength, and temperance. The recognition and acknowledgment of grace, wherever we see it expressed, will bless us as a power and presence in our own lives for the benefit of all. We don’t have to conjure up grace; it is of God, and it overcomes the world. What a great gift!

Adapted from an article published on sentinel.christianscience.com, May 12, 2022.

A message of love

Tennis, anyone?

A look ahead

Thank you for joining us. Please come back tomorrow, when we look at consumer demand, inflation, and the possibility of a recession.