- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 10 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- How overturning Roe will reverberate through America

- Ukraine’s candidacy for EU sends a signal. Now the hard part begins.

- Jan. 6 panel holds up public officials as ‘backbone of democracy’

- After high court ruling, is it tremors or earthquakes for public education?

- Congress acts on guns, with military vets among the vocal backers

- Party favor or art? Preserving the craft of the piñata.

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

The smell of victory after a long hunt

Bloodhounds are models of perseverance. Once they begin tracking a scent, other odors don’t distract them. They’ve been known to follow a trail for 130 miles.

So perhaps it’s fitting that it took them over 140 years to win the canine Super Bowl, the Westminster Kennel Club Dog Show. Trumpet, a big and noble bloodhound so wrinkled that his jowls have jowls of their own, took best in show at Westminster on Wednesday night.

He triumphed over Winston, a smiley French bulldog, and crowd favorite Striker, an immaculate and personable Samoyed, among others.

His handler and co-owner Heather Helmer said she was “shocked” at Trumpet’s win.

“I feel like sometimes a bloodhound might be a little bit of an underdog,” she said.

Bloodhounds have been at the Westminster Kennel Club since 1878. They’ve won the hound group of the club’s show 22 times since 1941. But they’ve never walked away with top honors before.

If “best nose” were a category, they’d have an unbroken winning streak. They can distinguish smells at least a thousand times better than humans, and far better than other dogs, even scent hounds like beagles.

Owners say they are sweet and loving companions. But the nose rules their life. They can’t be walked off leash. If a rabbit stirs a county over, they might be off.

They’re big. They need exercise. There is drool.

Underneath all that loose skin, though, there is charm. Take Trumpet. Outside the ring “he has a lot of attitude, and he’s a little crazy,” said Ms. Helmer.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

A deeper look

How overturning Roe will reverberate through America

After almost half a century, Roe v. Wade is no more. The United States will be grappling with the implications for years, if not decades, to come.

-

Henry Gass Staff writer

-

Story Hinckley Staff writer

-

Sara Miller Llana Staff writer

In overturning Roe v. Wade, the Supreme Court has taken the momentous step of ending a federal right to abortion that has existed since 1973, a decision likely to reverberate in American life, politics, and law.

At the start it is almost certain to divide the nation into zones, with about half the states enacting total bans on abortion, and others allowing it.

The decision’s long-term legal implications remain unclear. Justice Samuel Alito emphasized that abortion is a unique case in that it terminates a life or potential life, and thus the court’s action would not threaten other rights based on reasoning similar to Roe’s. But Justice Clarence Thomas appeared to differ, writing that the court should now reconsider past rulings that protect same-sex marriage, same-sex relationships, and access to contraception.

At the least, the ruling thrusts the Supreme Court directly into the maelstrom of the nation’s polarized politics with a definitive ruling on a highly contested issue, perhaps affecting how millions of citizens view the court’s role in the unique U.S. system of separated institutions that share and compete for power.

“Unprecedented is really the only way to describe it. ... It’s breathtaking. It’s hard to overstate how significant this is,” says Steven Schwinn, a professor at the University of Illinois Chicago School of Law.

How overturning Roe will reverberate through America

In overturning Roe v. Wade, the Supreme Court has taken the momentous step of ending a federal right to abortion that has existed since 1973, a decision likely to reverberate in American life, politics, and law in unpredictable ways for years, if not decades, to come.

At the start it is almost certain to divide the nation into zones, with about half the states enacting total bans on abortion, and others allowing it. Some blue states, such as California, are already planning how to deal with out-of-state travelers in search of the procedure.

The decision’s long-term legal implications remain unclear. Justice Samuel Alito, writing for the majority, emphasized that abortion is a unique case in that it terminates a life or potential life, and thus the court’s action would not threaten other rights that have been based on reasoning similar to Roe’s. But Justice Clarence Thomas, in a concurrence, appeared to differ, writing that the court should now reconsider past rulings that protect same-sex marriage, same-sex relationships, and access to contraception.

At the least, the ruling thrusts the Supreme Court directly into the maelstrom of the nation’s polarized politics with a definitive ruling on a highly contested issue, perhaps affecting how millions of citizens view the court’s role in the unique U.S. system of separated institutions that share and compete for power.

“Unprecedented is really the only way to describe it. ... It’s breathtaking. It’s hard to overstate how significant this is,” says Steven Schwinn, a professor at the University of Illinois Chicago School of Law.

The ruling in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health, a Mississippi abortion case, broke along the Supreme Court’s ideological fault lines, albeit with some disagreement within the court’s conservative majority.

Justice Alito wrote the majority opinion – as he wrote the draft opinion leaked in early May – and there seems very little difference between the two. Like the leaked draft, Friday’s opinion overturns the constitutional right to abortion, and as with the leaked draft, Justice Alito emphasizes that the elimination of the right to abortion doesn’t endanger other unenumerated constitutional rights.

“We hold that Roe and Casey must be overruled,” he wrote, referring to the 1992 case, Planned Parenthood v. Casey, that affirmed Roe while allowing states to impose limits for the health of the woman or fetus. “The Constitution makes no reference to abortion, and no such right is implicitly protected by any constitutional provision.”

Abortion is not outlawed in America, Justice Alito stressed, but it is not a constitutional right.

The Supreme Court has never overturned a recognized constitutional right, however. And Chief Justice John Roberts, in a solo concurrence, said that the court should have continued to show that restraint.

“I would take a more measured course” than the majority, he wrote.

Roe and Casey are flawed, he added, but the court should not have overturned the right to abortion when it could have simply upheld the Mississippi law in question, which bans abortion 15 weeks into a pregnancy.

“Surely we should adhere closely to principles of judicial restraint here,” he wrote.

“We dissent”

Typically written by one justice and “joined” by others, the dissent in Dobbs eschewed that tradition, with the three members of the court’s liberal wing – Justices Stephen Breyer, Elena Kagan, and Sonia Sotomayor – sharing authorship.

“When the majority says that we must read our foundational charter as viewed at the time of ratification (except that we may also check it against the Dark Ages), it consigns women to second-class citizenship,” they wrote. “Today, the Court ... says that from the very moment of fertilization, a woman has no rights to speak of.”

Saying the majority opinion rested on the “proclivities of individuals” rather than on the law, they foresaw a loss of respect for the court as well as a devaluing of women’s rights and health in the United States.

“With sorrow – for this Court, but more, for the many millions of American women who have today lost a fundamental constitutional protection – we dissent.”

The Supreme Court’s ruling in Dobbs may only be the beginning, the dissent warned.

The right to abortion was protected by the due process clause of the 14th Amendment. The clause – that no state shall “deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law” – has been interpreted over the decades to protect a number of rights not explicitly mentioned in the Constitution, including the right to interracial and same-sex marriage and the right to contraception and abortion.

Those due process rights “are all interwoven – all part of the fabric of our constitutional law,” wrote the dissenting justices.

“Faced with all these connections,” they added, “the majority tells everyone not to worry. It can (so it says) neatly extract the right to choose from the constitutional edifice without affecting any associated rights.”

“Should the audience for these too-much-repeated protestations be duly satisfied?” they ask. “We think not.”

Regardless of how the court handles questions arising from Friday’s ruling, the decision in Dobbs marks an unprecedented shift in constitutional law. The nature of that shift, according to Justice Alito, is that the Supreme Court should defer to the people – at least when it comes to abortion.

“In my judgment, on the issue of abortion, the Constitution is neither pro-life nor pro-choice. The Constitution is neutral, and this Court likewise must be scrupulously neutral,” he wrote.

“The Court today properly heeds the constitutional principle of judicial neutrality and returns the issue of abortion to the people and their elected representatives in the democratic process.”

The leak of the draft opinion by Justice Alito in early May, which made it clear that overturning Roe was a likely result of Dobbs v. Jackson, set the stage for Friday’s release of the final ruling. Both sides in the debate were poised for explosive news.

A victory decades in the making

Anti-abortion activists were overjoyed at what they saw as a long-sought victory that had been won by years of hard step-by-step effort. To them the high court has made a moral choice to support life.

“This is a monumental expansion of human rights and an excellent step forward towards creating a culture of life and a society that respects life,” says Herb Geraghty, executive director of Rehumanize International, an anti-abortion group based in Pittsburgh that follows a “consistent life ethic” and is opposed to violence of any kind.

But some still described their victory as limited. The court ruling bans a federal right to abortion, but it returns the issue to the states for their consideration and decisions. Thirteen states have trigger laws that will take effect within days, now that Roe is no longer in force. Another seven will likely enact a ban within weeks or months.

Guttmacher Institute

Beyond that, many predominantly blue states will retain or even bolster their rights to abortion. For many in the anti-abortion movement, a national ban is their ultimate goal.

The fact that abortion will only be expanded in some places is “extremely concerning,” says Geraghty.

Abortion-rights activists said they would continue to work to protect what they see as a fundamental right for women.

The first thing Jeni Keller, an activist in Mason, Ohio, did was call her local Planned Parenthood chapter and make an appointment for her 16-year-old to get an IUD. Ohio is one of the states preparing to ban or severely restrict abortion.

It’s “unbelievable that a 16-year-old would be forced to give birth against their will. ... That they’d be forced to carry a pregnancy to term because the government says so is absolutely horrifying,” Ms. Keller says.

Elaina Ramsey, executive director of Faith Choice Ohio, says, “We are not surprised by this ruling. But we still feel the gravity and grief of the moment. We lament the court’s decision.”

Ms. Ramsey says that as a woman and a woman of color, she has watched as the court slowly chipped away at some of her fundamental rights.

“Black folks, brown folks have always had to make a way, seek our own survival. And now, unfortunately, a lot of white folks are understanding that their rights also are being taken away,” she says.

Unsettling “settled law”

To many legal experts, one of the most notable aspects of the Dobbs decision was that it overturned a precedent long described as “settled law,” even by some of the justices who voted in the majority to scrap Roe.

Stare decisis, the legal principle of using precedent to determine the outcomes of litigation, does not always rule the day. But the Supreme Court has never before overturned precedent to take away a right, says Lawrence Gostin, faculty director of the O’Neill Institute for National and Global Health Law at Georgetown University Law Center.

“All the other times that the court has overturned long-standing settled precedent, it was to grant a right, like the right to interracial marriage or the right to gay marriage,” says Professor Gostin.

Some experts think the Dobbs decision may herald the loss of other settled rights in the future. Roe was based on an unenumerated (unwritten in the Constitution) right to privacy. But if one unenumerated right can be reversed, so might others, such as same-sex marriage, that are similarly rooted in a perception that the nation’s founding documents guarantee its citizens a zone of personal autonomy.

“This court I think will jump at opportunities to overturn cases like Griswold, dealing with the right to contraception; Lawrence v. Texas, dealing with the right to consensual adult sexual conduct; and even Obergefell,” which established the right to same-sex marriage, says Professor Schwinn of the University of Illinois Chicago School of Law.

Justice Alito wrote explicitly in today’s Dobbs ruling that this was not the case, and that the majority’s reasoning applied only to abortion. Abortion is inherently different from marriage, or procreation, because it involves the termination of life or potential life, he wrote.

“Nothing in this opinion should be understood to cast doubt on precedents that do not concern abortion,” says the Dobbs opinion.

But Justice Thomas, writing in a concurrence, said otherwise. He wrote that in future cases the court should now reconsider all of its “substantive due process precedents,” including Griswold, Lawrence and Obergefell.

It is not entirely clear what the full implications of this position are, and whether other justices would be reluctant to sign onto it, says Professor Schwinn.

But Justice Alito simply saying that Dobbs is only about abortion does not necessarily make it so, he says.

“There’s plenty in the Alito opinion that lays the groundwork for overturning other rights,” says Professor Schwinn.

Conservative scholars point out that Justice Thomas couldn’t get any other justices to sign on to his concurrence, meaning those other rights may not come under immediate scrutiny.

“Several members of the court went out of their way to say that nothing in today’s decision threatens or casts doubt on those other cases,” said Allyson Ho, partner at Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher LLP, in a webinar hosted by the Federalist Society. “With only Justice Thomas’ concurrence – and no other justice joining it ... probably the smart money will be on it being quite a while before there are four votes to [hear] a case to undertake that analysis.”

“This is just the beginning”

Hannah Sellars walks toward the Bell Tower outside the Virginia statehouse, where abortion-rights activists gathered in protest just hours after the Supreme Court released its decision. In Virginia, one of the states where abortion is still legal, recently elected Republican Gov. Glenn Youngkin announced that he will now seek to ban most abortions after 15 weeks of pregnancy.

“My first thought was that this is just the beginning of women’s rights getting taken away,” says Ms. Sellars, who owns a studio nearby.

She can’t help but think about the abortion she had a decade earlier – when she was a teenager, and “just didn’t have her life together.” Anti-abortion activists assume that women treat abortions like birth control, getting them “willy-nilly,” says Ms. Sellars. But she says that’s not the case, and it was an incredibly difficult decision.

“If I didn’t have an abortion, I wouldn’t have my business now,” she says. “I wouldn’t have had the chance to build my life.”

When Leslie Rubio and Tara Morand heard the news, they left the Richmond office where they work in real estate. They stood on the sidewalk and screamed.

“We’re both mothers,” says Ms. Rubio. She pauses, before adding, “I’ve had an abortion. I’m not ashamed of it. It feels awful, but sometimes it’s necessary.”

“My entire body is reacting right now,” says Ms. Morand, holding a pink Planned Parenthood poster.

“I’ve passed that time in my life,” she adds, before she starts to cry and covers her mouth. “But for young girls today, their lives ...” Ms. Morand trails off before breaking into more tears.

“Double down with compassion”

Meanwhile, the Rev. Samuel Rodriguez, pastor of New Season Church in Sacramento, California, and president of the National Hispanic Leadership Conference, says anti-abortion activists need to “put the same energy into demonstrating mercy and compassion as we have our activism.”

Mr. Rodriguez says he wants to see the largest adoption movement in American history.

“My concern has always been this unbridled advocacy while the baby is in the womb. We need to be very holistic. We need to be pro-life from the womb to the tomb,” he says via phone. “Now we have this victory.

“We must double down with compassion, come alongside women who are making very difficult decisions ... show empathy toward women who have had [abortions] and women that have difficult decisions to make, especially those because of their social economic reality.”

Guttmacher Institute

Ukraine’s candidacy for EU sends a signal. Now the hard part begins.

European Union leaders granted Ukraine candidacy to be a member of the bloc, bolstering Ukrainian morale and EU solidarity. But the practical difference could be a decade or more away.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

On Thursday, the European Union officially made Ukraine a candidate for membership in the bloc, in a striking show of unity widely seen as a rebuke to Russia for waging a brutal war to keep the former Soviet republic under its control.

“Ukraine is going through hell for a simple reason: its desire to join the EU,” European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen tweeted on the eve of the announcement. She later added that it would serve as a signal “to the world that the EU is united and strong in the face of external threats.”

But while the move to candidate status happened in record time, becoming a member is itself an arduous process that can take more than a decade – sometimes more than two. It entails meeting exacting requirements to, among other things, tackle the sort of deep-seated corruption that has long plagued Ukraine and other candidate countries.

And the obligations cut both ways. The EU “has not been good at rewarding countries who have carried out reforms,” says Rosa Balfour of Carnegie Europe. It must ensure that in five years’ time, Ukrainians “don’t find themselves in a situation of disappointment and disillusion.”

Ukraine’s candidacy for EU sends a signal. Now the hard part begins.

Until last week, Ukraine’s candidacy for membership in the European Union was far from a foregone conclusion.

French President Emmanuel Macron and German Chancellor Olaf Scholz, for starters, made no secret of their lack of enthusiasm for the idea, with Mr. Macron suggesting that perhaps a lower-tier, non-member political alliance was the best way to go.

But after visiting Ukraine last week – surveying wreckage and graffiti that, reporters on the scene noted, implored “Make Europe, not war” – the leaders announced, in the face of political pressure and a desire, perhaps, to be on the right side of history, their support. And on Thursday, the bloc made Ukraine’s candidacy official, in a striking show of unity widely seen as a rebuke to Russia for waging a brutal war to keep the former Soviet republic under its control.

“Ukraine is going through hell for a simple reason: its desire to join the EU,” European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen tweeted on the eve of the announcement. She later added that it would serve as a signal “to the world that the EU is united and strong in the face of external threats.”

But while the move to candidate status happened in record time, becoming a member is itself an arduous process that can take more than a decade – sometimes more than two. It entails meeting exacting requirements to, among other things, tackle the sort of deep-seated corruption that has long plagued Ukraine and other candidate countries.

The challenge for Kyiv in the months and years to come, analysts say, will be embarking on transformative reforms to enshrine human rights, a sustainable market economy, and rule of law throughout the country while fighting a war.

The challenge for the EU will be how to assure other candidate countries – including those who have suffered democratic backsliding in the midst of their yearslong efforts to join the union without success – that an offer to join the union is not an empty promise.

A big deal for Ukraine

In the Orange Revolution of 2004, Ukrainians took to the streets in a wave of civil resistance, protesting massive presidential election fraud and voter intimidation.

Europe was watching as the country ushered in changes in presidential election law and constitutional reform as Viktor Yushchenko – who survived a near-fatal poisoning while campaigning against the Kremlin-backed candidate – went on to serve as president from 2005 to 2010.

It was the beginning of talk about possible membership in the EU “in a serious way,” says Rosa Balfour, director of the think tank Carnegie Europe in Brussels.

A decade later, the Euromaidan revolution was sparked by then-President Viktor Yanukovych’s refusal, due to Russian pressure, to sign a widely popular free trade agreement with the EU.

It was the final straw for protestors angered by, among other things, government corruption and the influence of oligarchs. They occupied Independence Square in Kyiv and battled security forces, ultimately ousting Mr. Yanukovych.

Given this history, EU candidate status is “a big deal politically and symbolically for Ukraine,” says Bruno Lété, senior fellow at the German Marshall Fund of the United States in Brussels.

“It’s saying, ‘Look, we want to reward you for years and years of reforms you’ve been undergoing since [Euromaidan] revolution.”

That said, it’s just the beginning of what promises to be, by most estimates, at least a decade-long process.

“I think often for people outside the EU, their view is, ‘What’s the big deal to join the EU?’ as if it’s like any other multilateral organization,” says Max Bergmann, director of the Europe Program at the Center for Strategic and International Studies. “But it’s like if Mexico decides to become part of the United States.”

Countries who join – Croatia most recently became the 28th member nation in 2013 – must tackle a massive to-do list that includes everything from judicial system reform to precisely what statistical parameters must be implemented when carrying out censuses.

Obligations for the EU

And while there’s broad backing within the EU for giving Ukraine candidate status, there’s no unanimity when it comes to support for actually making many candidate countries into members, says Mr. Lété.

EU rules require unanimity on major policy decisions. This has led to embarrassing roadblocks due to the objections of a single member state.

“The EU is still structured the way it was structured when it had 12 member states,” Mr. Lété says. “It can’t function efficiently anymore.”

Today, five countries – Albania, Montenegro, North Macedonia, Serbia, and Turkey – are candidates to join the EU. But many have concerns about how the addition of these countries’ people – and now Ukraine’s 40 million citizens too – could change the EU, with its 447 million inhabitants, from within, Mr. Lété adds.

For this reason and others – including failure to enact required reforms – movement on the candidate applications has been slow. In the interim, some candidate nations have experienced significant backsliding on basic democratic principles like rule of law.

“The challenge that countries, especially in the Balkans, have found is that once it became clear to them that actual membership wasn’t really in the cards anytime soon, the reform process starts to suffer,” Mr. Bergmann says.

Turkey, which obtained its candidate status in 1999, is a notable example. North Macedonia has a leader who has made “very brave” decisions in recent years, but, “We should find a way that this bravery isn’t disappointed,” German Chancellor Scholz recently warned.

The EU “has not been good at rewarding countries who have carried out reforms,” Dr. Balfour of Carnegie Europe adds.

As a result, candidate status for Ukraine and Moldova – which also received the offer this week – raises questions about what to say to countries that have been working towards membership for years and are becoming increasingly frustrated about the slow pace of accession.

The EU must ensure that in five years’ time, Ukraine and Moldova “don’t find themselves in a situation of disappointment and disillusion,” Dr. Balfour says. She adds that this could happen if the countries “don’t see prospects of joining the EU as a goal, as a real anchor.”

Still, after being accused for years of enlargement fatigue, the EU’s unanimous vote this week “is testimony that the door is still open,” Mr. Lété says.

It is also a vote for unity that will give beleaguered Ukrainians a vital morale boost that will serve as a mobilizing force, Mr. Bergmann says.

“Are you fighting for a country that’s going to be perpetually wedged between the EU and Russia, always in a halfway house?” he asks. “Or are you fighting for a future?”

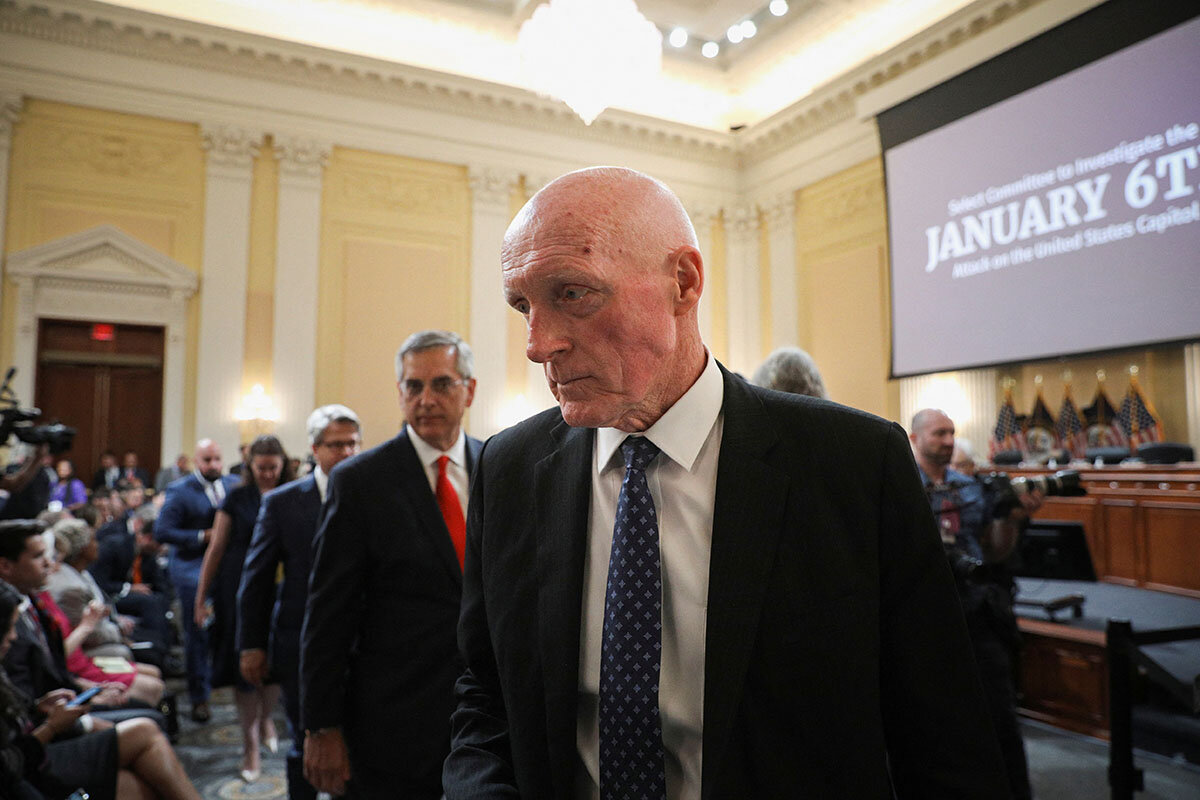

Jan. 6 panel holds up public officials as ‘backbone of democracy’

Relying mainly on Republican witnesses, some with heart-wrenching personal stories, the Jan. 6 committee explored the role that election officials play in safeguarding democracy – with a resonance beyond 2020.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

-

By Christa Case Bryant Staff writer

In congressional hearings this week, the Jan. 6 committee highlighted public officials from local election workers to the government’s top lawyers as integral to preserving the American republic.

One by one, these witnesses explained why they had resisted then-President Donald Trump’s entreaties to declare the 2020 election fraudulent – and the blowback they and their families have faced as a result. Nearly all of them had voted for Mr. Trump and/or worked in his administration, from Arizona House Speaker Rusty Bowers to Jeffrey Rosen, a Trump appointee who served as acting attorney general in the weeks leading up to Jan. 6.

Citizens who believe the election was stolen have called them traitors and tyrants. And even some who admire their sense of principle wonder what parts of the story may be missing from these hearings.

Yet the courage and fortitude highlighted by the committee resonated with other Americans not only regarding 2020, but also heading into this fall’s midterms.

“What the American people saw on Tuesday is a snapshot of what’s happening to election officials in counties and states everywhere across the country,” says Dokhi Fassihian, an advocate for election integrity at the group Issue One.

Jan. 6 panel holds up public officials as ‘backbone of democracy’

In congressional hearings this week, the Jan. 6 committee portrayed public officials as integral to preserving the American republic.

One by one, the committee brought them forward to explain why they had resisted then-President Donald Trump’s entreaties to declare the 2020 election fraudulent – and the blowback they have faced as a result. Nearly all of them were Republicans who had voted for Mr. Trump and/or worked in his administration.

There was Arizona GOP Speaker of the House Rusty Bowers, who refused to bend out of fidelity to the Constitution even as protesters surrounded his home with megaphones, disturbing his gravely ill daughter.

There was Georgia Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger, who was doxxed and his life threatened, yet refused to stand down.

And there was Richard Donoghue, the Justice Department’s No. 2, who was called unexpectedly into the Oval Office days before Jan. 6. He sat before the president in an Army T-shirt, jeans, and muddy boots and told Mr. Trump in no uncertain terms how much he had to lose if he replaced the department’s current leadership with someone prepared to declare the election fraudulent despite their investigations not having found such evidence. The president abandoned the idea.

Amid deep partisan divisions over Jan. 6 and this congressional investigation, the Democrat-led committee expressed gratitude for these officials’ integrity, courage, and fortitude.

“They represent the backbone of democracy,” said Chairman Bennie Thompson, a Mississippi Democrat. “They have earned the thanks of a grateful nation.”

To be sure, not everyone in America shares that sentiment. Citizens who believe the election was stolen have called them traitors and tyrants. And even some who admire their sense of principle wonder what parts of the story may be missing from these hearings, a tightly focused series with one clear thesis and no dissenting voices or cross-examination.

Former President Trump, for his part, has sought to delegitimize the panel. “If they had any real evidence, they’d hold real hearings with equal representation,” he said in a 12-page statement earlier this month.

Still, even as Republicans dismiss these hearings as a pointless partisan exercise, Mr. Trump recently criticized GOP leadership for withdrawing from the committee last summer after Speaker Nancy Pelosi vetoed two Republican appointees. (She also appointed two other Republicans, Vice Chair Liz Cheney and Rep. Adam Kinzinger, both of whom voted to impeach the former president for “incitement to insurrection.”)

Some interpreted Mr. Trump’s criticism as a signal that the committee’s narrative, told mainly through the testimony of Republican officials, is getting through to the American public more than the GOP had anticipated.

“Secret suitcases” and a ginger mint

This week’s first hearing, on June 21, focused on Mr. Trump’s efforts to get state officials to corroborate his claims of election fraud.

The most well-known witness was Secretary Raffensperger, whose Jan. 2 phone call resisting Mr. Trump’s request to “find” enough votes to overturn the election was recorded and released two days later. His chief operating officer, Gabriel Sterling, testified to how his team reviewed 48 hours of surveillance video that determined that the alleged “secret suitcases” in a Georgia polling center were legitimate ballot carriers packed in full view of election monitors. And Wandrea ArShaye Moss, an election worker in Fulton County, Georgia, described how she loved helping older voters, since some in her African American family had not always had the right to vote.

She would help them navigate the county’s election website, get a precinct card, or even drive an absentee ballot out to them. Then Rudy Giuliani accused her and her mother, Ruby Freeman, of tampering with election results, based on a video from the polling center Mr. Sterling had investigated.

“That was a week ago, and they’re still walking around Georgia, lying,” said Mr. Giuliani, who called for their homes to be searched. What he claimed was a USB drive they had passed between each other was in fact a ginger mint, Ms. Moss testified.

She described getting death threats to her Facebook private messages, with people saying things like, ”Be glad it’s 2020 and not 1920.”

Ms. Moss, who has since quit her job after more than a decade in it, is still afraid to go out. Her mom, Ms. Freeman, whose earlier testimony to the committee was played during the hearing, is afraid of having her name called in public – even by friends in the grocery store. She asked listeners to consider what it’s like to be targeted by the president, who is supposed to represent all Americans.

Election officials and poll workers are facing increased strain and threats – not only around 2020, which presented new challenges amid a pandemic and an incumbent president’s claims of fraud – but also heading into this fall’s midterms.

“What the American people saw on Tuesday is a snapshot of what’s happening to election officials in counties and states everywhere across the country,” says Dokhi Fassihian, deputy chief of strategy and programs at Issue One, which this week brought a bipartisan group of election officials and poll workers to lobby Congress and the White House for more funding for everything from physical protection to communications staff who can counter disinformation. Their main message: “We just need people to have our backs.”

“It is painful to have friends ... turn on me with such rancor”

Tuesday’s hearing also portrayed Mr. Trump and his team as pressuring GOP legislators in swing states.

Speaker Bowers of Arizona, a member of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, told the committee that he would not contravene the Constitution because it was a tenet of his faith that it is divinely inspired. So he resisted calls to get the Arizona legislature to appoint new electors who would declare Mr. Trump the winner instead of Joe Biden.

When he heard that his colleagues had circumvented him and assembled an alternate group of electors in Phoenix on Dec. 14, he described it as “a tragic parody.” His secretary received more than 20,000 emails and tens of thousands of voicemails and texts, making it difficult to work, he testified. And on the weekends, protesters would drive through his neighborhood with blaring loudspeakers, calling him a pedophile. The commotion was particularly disturbing to his adult daughter, who was gravely ill.

“It is painful to have friends who have been such a help to me, turn on me with such rancor,” he wrote in a journal entry from that time, which he read during the hearing. But he resolved not to respond with fear or vengeance.

“I do not want to be a winner by cheating,” he wrote. “How else will I ever approach Him in the wilderness of life, knowing that I ask this guidance only to show myself a coward in defending the course he led me to take?”

After his testimony Tuesday, well-wishers – including some Democrats – flocked to his Facebook page to praise him as a “constitutional hero” and offer condolences for the death of his daughter, Kacey Rae Bowers, shortly after Jan. 6.

“Sir, thank you for your testimony today. Deepest respect,” wrote one. “I’m sorry for what you and your family have endured. You are a shining example of what we should all aspire to be.”

“You give me hope that there are truly good republicans out there. And I was losing hope,” wrote another. “I also hope that your truth spurs more truth from more republicans.”

Holding a line at the Justice Department

This week’s second hearing, on June 23, focused on Mr. Trump’s efforts to persuade the Justice Department’s top lawyers to tell the American people that there had been enough fraud to potentially overturn the election.

It focused mainly on a contentious meeting the evening of Jan. 3, 2021, about whether to replace Mr. Rosen, the acting attorney general, with Jeffrey Clark, a Trump ally.

In the preceding days, Mr. Clark had drafted a letter that said the department had “identified significant concerns” that could change the election results. When Mr. Rosen, the acting attorney general, refused to sign the letter because none of the department’s investigations had found fraud on such a scale, Mr. Trump moved to replace him with Mr. Clark.

Mr. Rosen testified that in his mind the issue was not his personal role. The inauguration was in 17 days, so if his job ended a little earlier, it just meant a couple weeks of vacation. But what he was more concerned about, he said, was ensuring that the Justice Department stuck to the facts and the law and didn’t enter the political fray.

“When you damage our institutions, it’s not easy to repair them,” said Mr. Rosen, who told the president – as did Mr. Donoghue and assistant attorney general Steven Engel – that he would resign if the president appointed Mr. Clark.

Mr. Engel testified that he pointed out to the president that if he appointed Mr. Clark, the story would not be that the Justice Department had found election fraud but that the president had gone through three attorney generals in less than a month.

By the end of the meeting, Mr. Trump decided to abandon his plan, and the letter Mr. Clark had drafted was never sent.

The Jan. 6 committee credited the “bravery” of these lawyers, and said their willingness to put their jobs on the line narrowly prevented Mr. Trump from overturning the election results.

“If we are going to ask Americans to be willing to die in service to our country, we as leaders must at least be willing to sacrifice our political careers when integrity and our oath requires it,” said GOP Rep. Adam Kinzinger of Illinois, an Iraq veteran and member of the committee who led Thursday’s hearing. “After all, losing a job is nothing compared to losing your life.”

After high court ruling, is it tremors or earthquakes for public education?

The Supreme Court’s decision this week about state funds going to religious schools raises questions about the future of public education and whether more taxpayer money could eventually fuel a wide array of schooling options.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

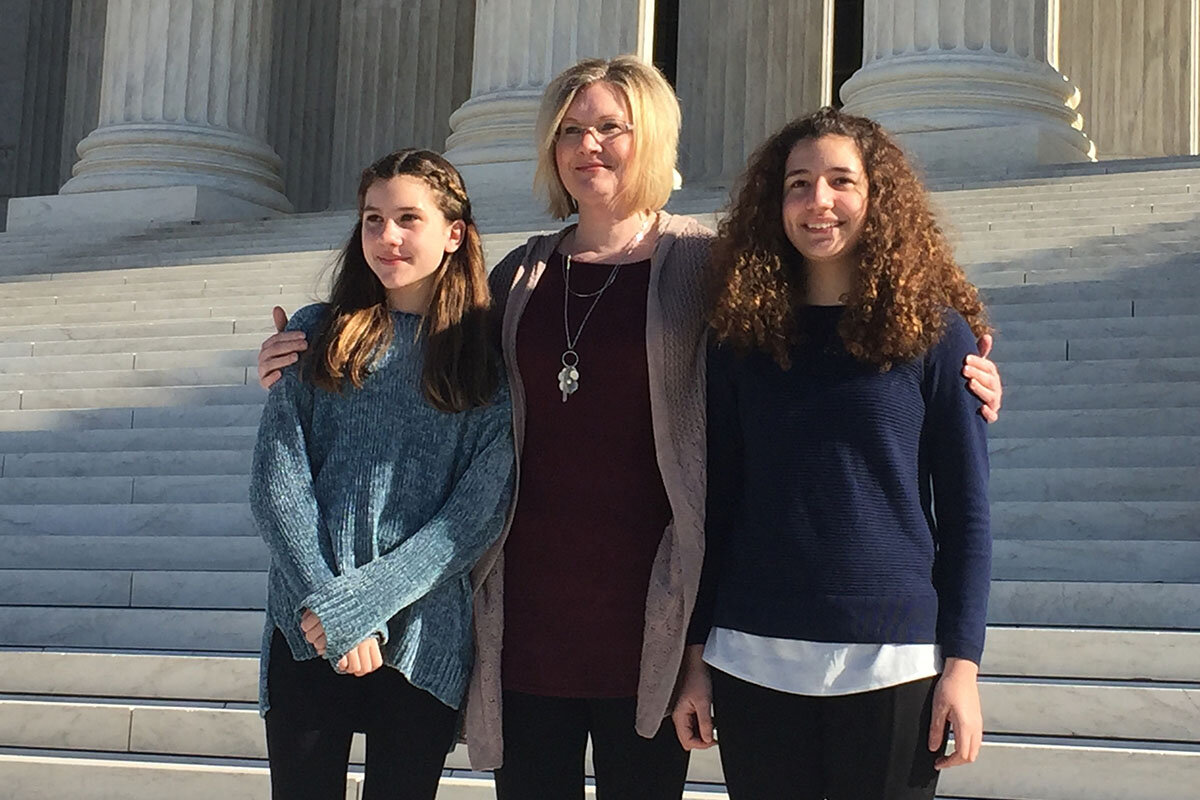

Though not as high-profile as gun and abortion cases decided by the U.S. Supreme Court this term, Tuesday’s ruling in Carson v. Makin could significantly impact public schooling in the United States over time.

In a 6-3 decision, the court ruled that Maine must include religious schools in its unique town tuitioning program, which offers public funds to families to attend schools of their choice if they live somewhere with no public schools for their students’ grade level or contracts with nearby school districts. The state had previously excluded “sectarian” religious schools until the court struck down that law, calling it “discrimination against religion.”

The decision is causing both excitement and consternation. Effects of the ruling could range from more families opting out of local schools, to more tax dollars being spent on religious education, to public schooling and a growing list of alternatives continuing to delicately coexist.

“This [case] already is a rallying cry for folks interested in defending public education and the value of public schools in American life,” says Michael Graziano, an expert on religion and education at the University of Northern Iowa. “I also think this is absolutely a huge win for the school choice movement.”

After high court ruling, is it tremors or earthquakes for public education?

Public education is navigating enrollment declines, shaky parental trust, and sizable learning losses. This week the U.S. Supreme Court added another factor to the rocky educational landscape: a ruling that permits more public funding to flow to religious schools.

Though not as high-profile as gun and abortion cases decided by the justices this term, Tuesday’s ruling in Carson v. Makin could significantly impact schooling in the United States over time.

Some believe the very nature of secular public education is in play, and that’s causing both excitement and consternation. Effects of the decision could range from more families opting out of local schools, to more tax dollars being spent on religious education, to public schooling and a growing list of alternatives continuing to delicately coexist.

“This [case] already is a rallying cry for folks interested in defending public education and the value of public schools in American life. I also think this is absolutely a huge win for the school choice movement,” says Michael Graziano, director of the Institute for Religion and Education at the University of Northern Iowa. “This continues a trend that this particular court has of trying to collapse public institutions into private ones or religious ones more particularly.”

In a 6-3 decision, the court ruled that Maine must include religious schools in its unique town tuitioning program. Maine, the most rural state in the U.S., has about 5,000 students who live in towns with no public schools for their grade level or contracts with nearby school districts. The state offers those families funds to attend public or private schools of their choice. The state had restricted the tuition funds to exclude “sectarian” religious schools until the court struck down that law.

“The State pays tuition for certain students at private schools – so long as the schools are not religious. That is discrimination against religion,” wrote Chief Justice John Roberts in the court majority opinion. The court’s three liberal justices dissented.

The decision “will hopefully open back up the opportunity for parents to choose the best school for their kids under the tuition program,” says Amy Carson, who, along with her husband David, joined the lawsuit when their daughter couldn’t use state funding to attend their private school of choice, Bangor Christian Schools.

“Next domino to fall”

The ruling leads some scholars to question whether the reasoning – based heavily on First Amendment free exercise clause rights rather than establishment clause interests – could extend to permit religious entities to run public charter schools. Or to eventually require state funding of religious education.

“The logic in this case, if extended, could be applied to [religious] charter schools, and many of us see that as the next domino to fall,” says Preston Green, a professor of educational leadership, law, and urban education at the University of Connecticut.

“This may not end with charters. It could go even beyond that,” to providing funding for religious education, says Professor Green.

It’s a point one of the justices raised as well. “This Court continues to dismantle the wall of separation between church and state that the Framers fought to build,” wrote Justice Sonia Sotomayor in her dissent to the Carson opinion.

But there’s still an important distinction between programs that allow parents to choose from a variety of options and funds provided directly from the state to religious schools, says Jonathan Butcher, an education fellow at the Heritage Foundation in Washington.

“If the money goes to the families who then decide what to do with it, then it’s not a question of the state advancing religion. If the money went straight to a school that had a religious mission and was using it for religious purposes, that then could be a question of establishing religion,” he says.

Adding to case law

The court’s decision Tuesday builds on earlier Supreme Court cases expanding the rights of religious entities in education. In the 2020 case Espinoza v. Montana Department of Revenue, for example, the court struck down a law prohibiting funds from a state tax scholarship program to go to religious schools.

In both rulings, the court made clear that states do not have to subsidize private education, “but once a State decides to do so, it cannot disqualify some private schools solely because they are religious,” as Chief Justice Roberts wrote in Espinoza, and quoted in Tuesday’s opinion.

The chief justice laid out alternatives that Maine could consider for its tuition program, such as adding more public schools and transportation, providing tutoring and remote learning, or running boarding schools.

In order to implement any of those ideas, “the state would have to be willing to fund it,” says Professor Green, who points out that states have historically underfunded education, especially in communities of color.

The decision in Carson will encourage state lawmakers to see that “there are not federal obstacles in the way” of creating means for parents to choose how and where their children learn, says Mr. Butcher at the Heritage Foundation.

He believes the ruling will boost educational savings accounts, a relatively new concept that is currently offered by eight states, according to EdChoice, a nonprofit promoting school choice.

“This is the essence of what I believe the Carson decision is really speaking to, and that’s the idea that the money goes straight to a parent who can then choose from several things at the same time, [like] educational therapy, online classes, personal tutors,” says Mr. Butcher.

In Maine, parents can pick a secondary school for their children if the school is accredited by a regional body or the Maine Department of Education. Once parents select, the local school district transmits payments to the chosen school. Parents could choose religious schools until 1981, when Maine changed the law based on establishment clause concerns.

The National Coalition for Public Education, in a statement responding to Carson v. Makin, argued that the U.S. “must stop creating new private school voucher programs and end the ones that exist.”

“Public schools, which serve all students, are a cornerstone of our democracy. Our nation cannot afford to waste taxpayer money on a privately run education system, particularly one that fails to improve academic achievement,” the statement read in part.

Some uncertainty in Maine

Whether the religious schools at the heart of the Carson case will end up accepting the public tuition money they are now eligible for is unclear.

Bangor Christian Schools and Temple Academy, the two institutions that the plaintiffs in the lawsuit wanted their children to attend, admit that they “discriminate against homosexuals, individuals who are transgender, and non-Christians” in their admissions and hiring practices, according to a case brief by the state of Maine.

Last year, Maine legislators added wording to the state’s Human Rights Act that prevents employers from discriminating on the basis of gender identity. During Supreme Court arguments, the issue was raised whether the religious schools, if receiving state funds, would be exempt from Maine’s law, which already prohibits discrimination based on sexual orientation. The court opinion did not address that question.

Ms. Carson says she’s worried that after four years spent legislating the case, and the Supreme Court victory, families who want to use state funds to attend Bangor Christian still might not be able to if the schools choose not to participate.

“I do not expect any of the schools to change their policies just to be able to accept the funds, but it would be very disappointing to go through all this and have it be that the families that it would benefit could not use it,” she says.

States could consider a strategy of making private schools ensure they aren’t discriminating in order to gain public funds, says Noelle Ellerson Ng, associate executive director of advocacy and governance at the School Superintendents Association, a member of the National Coalition for Public Education.

“If you cannot do the work to serve every child that wants to come to your school, you should not get the public dollars that go with that,” says Ms. Ng.

The U.S. can have both strong traditional public schools and school choice, if states provide enough funding, says Professor Green. Even so, he says, having to provide more and more money to alternative choices could strain resources and cause issues with fulfilling state constitutional duties to provide a public education for all.

Mr. Butcher says public education and school choice programs will continue to coexist. Public schools still enroll about 50 million children, while about 600,000 kids are enrolled in school choice programs, he says.

“Carson v. Makin reinforced that we can create other options for parents and not say either/or,” he adds. “It’s not either private or public – we can have both.”

Congress acts on guns, with military vets among the vocal backers

Members of the U.S. military in some ways trend conservative. Yet they share wider public concerns about gun safety – often supporting restrictions on military-style firearms.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

In the heated debate over guns in America, military veterans are increasingly weighing in to encourage cooperation in a quest for greater safety, notably for vulnerable schoolchildren.

“Some gun manufacturers are selling the idea that we can have unfettered freedom without responsibility – but you can’t have one without the other,” says Jason Dempsey, who served as an infantry officer in Iraq and Afghanistan. Now he is part of a veterans advisory body for the group Everytown for Gun Safety.

Patterns of gun ownership and political conservatism might suggest that military service members and veterans would be more opposed to gun control measures than the average U.S. citizen. And it’s true that veterans are more likely to be supportive than nonvets of expanding civilians’ gun carrying rights, finds one recent academic study.

Yet veterans with combat experience are 78% more likely than nonvets to favor banning AR-15s and other military-style rifles and high-capacity ammunition clips. They are also more likely to favor a 14-day waiting period for all gun purchases.

For veterans who are advocating on the issue, it’s promising to see Congress pass a significant gun safety bill this week. It includes enhanced background checks for gun buyers between ages 18 and 21.

Congress acts on guns, with military vets among the vocal backers

As a Marine Corps veteran with a Facebook account, Carl Forsling saw friends of friends posting in the days after the Uvalde school shooting in Texas about how to prevent such future tragedies.

The gist was, “Arm veterans, put them in schools, problem solved,” he says – a solution endorsed by Sen. Lindsey Graham, among other policymakers. “It’s the idea of, ‘This is a hard problem – let’s have military veterans do it.’”

Mr. Forsling, who served as a company commander in Afghanistan, decided to write a piece pointing out some flaws he saw in the “good guy with a gun” proposals. Among them: that very few veterans have the sort of training in high-stress, close-quarters shooting situations that allows them to be an asset on the scene.

“It’s not like riding a bike,” he notes. Experts train for a living. “There’s a reason why special operations forces are held in such high regard.”

Upon the piece’s publication, Mr. Forsling garnered plaudits from fellow veterans but pushback from the people who love them, including responses along the lines of, “You’re wrong – veterans can do anything!” and “My cousin Kevin was in the Navy. He doesn’t have a job and would love to do this,” he recalls.

In the heated debate over guns in America, U.S. veterans are increasingly weighing in to provide reality checks on policy proposals and endeavoring to encourage cooperation and forge compromise in what is – it’s widely agreed across the political aisle – a critical quest for the safety of vulnerable schoolchildren.

In many cases, their efforts represent a change in tack to get laws enacted, even if they fall short of the bans on certain weapons many would like to see, says Jason Dempsey, who served as an infantry officer in Iraq and Afghanistan.

“When you have something that’s been argued again and again for 20 to 30 years, it’s hard to break new ground. But accepting the status quo is just unfathomable,” he says.

“What we’re trying to get at is that if we’re going to be fetishizing these military-grade weapons, then at least we can push for training, safety, and accountability,” adds Dr. Dempsey, who has a Ph.D. in political science and serves on the Everytown for Gun Safety Veterans Advisory Council.

Such efforts at compromise, from vets and others, paid off this week as Congress passed its first major gun safety legislation in a quarter century – with a Senate vote Thursday followed by House action Friday to set up an expected signature by President Joe Biden. The bill tightens up registrations for firearms dealers, makes it easier to remove guns from people convicted of domestic violence, and enhances background checks for gun buyers between ages 18 and 21 (the Uvalde shooter legally bought his assault rifle the day after he turned 18).

“If you don’t rent a car to someone under 25, because you don’t trust them, or if we don’t trust you with a beer, we probably shouldn’t trust you with some of these weapons,” Dr. Dempsey says. “Some gun manufacturers are selling the idea that we can have unfettered freedom without responsibility – but you can’t have one without the other.”

Combat experience pivotal

When Christopher Ellison, professor of sociology at the University of Texas at San Antonio, began researching the opinions of veterans on gun control, he and his colleagues were surprised how little social science there was on the topic.

“We thought, my goodness, surely somebody’s looked at this before – how combat experience and other types of military socialization may play into gun policy attitudes.”

They had not, though many have assumptions about what veterans think of gun laws – particularly given that they’re more likely to own firearms than the general population, and given the trend toward political conservatism in the ranks since the end of conscription, Dr. Ellison notes.

Such factors might suggest that military service members would be more opposed to gun control than the average U.S. citizen.

“What we found was much more nuanced,” he says.

While veterans are more likely to be supportive than nonvets of expanding civilians’ gun carrying rights – including supporting open carry laws – veterans with combat experience are 78% more likely than nonvets to favor banning AR-15s and other military-style rifles and high-capacity ammunition clips, Dr. Ellison and his colleagues concluded in their subsequent study, which was published in April in Social Science Quarterly.

They are also more likely to favor a 14-day waiting period for all gun purchases.

The opinions of military veterans without combat experience, by contrast, “were not all that different from the general population,” he notes. “I think a lot of people might have suspected that particularly combat veterans would be all gung-ho and say ‘less gun control.’”

Much of this has to do with the “demystification” of firearms that comes from combat experience, in which they are seen as a tool, rather than as an object of empowerment, Dr. Ellison and his colleagues hypothesize.

“These are people who know the most about the capacity of these firearms – and the damage they can do.”

Family safety first

As a mother and a military veteran who was a pistol instructor and captain of the crew team at the U.S. Naval Academy – later serving as a pilot – Sarah Dachos had plenty of experience with weapons.

“I had these quote-unquote credentials. I roll my eyes as I say that, but this is what people think.”

But ultimately gun violence in America convinced her to settle in the Netherlands with her Dutch husband and their two young children.

It was a wrenching decision that left her feeling like she was “abandoning” Washington, D.C. Yet it was about the safety of her family. She was seeing an increase in gun violence, and then there was a shooting incident two blocks from her home along the route where she walked her child to school.

Having lived in America for eight years, Ms. Dachos’ husband “had constantly asked me how it was possible to have such levels of gun violence in one of the most industrialized, democratized, and wealthiest countries on the planet.”

Ms. Dachos saw a connection between racism and violence, and led volunteer efforts with Moms Demand Action, a gun safety nonprofit. “We’d set up tables at conferences to talk about ‘How do you keep your gun safe? How do you talk to people who have guns when there’s a play date?’”

She found the foot traffic encouraging. “Everybody wants to be safe with their guns. Most people don’t want to kill people with their guns. So that’s a great way to engage,” she says. “It’s, ‘We’re not trying to take away your guns.’”

But after moving to the Netherlands with their two young children, where they were close to grandparents and where their children could attend schools during the closures due to the pandemic, Ms. Dachos and her husband got used to feeling safe.

“The big advantage here is that the kids are not doing shooter drills or experiencing live shooters in their schools,” she says. “At one point my husband and I looked at each other and said, ‘It’s not worth it to us to run the risk that our children will be victims of gun violence.’”

Today, when not working for a composting business, Ms. Dachos continues to write grant proposals for the TraRon Center in Washington, a nonprofit that helps children affected by gun violence work through their grief.

Ms. Dachos has been impressed by the legislative efforts of Sen. Chris Murphy and her former crew teammate from the Naval Academy, Rep. Mikie Sherrill, who have worked on compromise gun control bills, and by efforts in 19 states to enact red flag laws to prevent people who show signs of being a threat to themselves or others from buying guns.

“There’s not a lot of new stuff to come up with” when it comes to gun control legislation, Ms. Dachos says. “But maybe the fresh thinking is in ‘How do we continue to engage with those who don’t agree with us?’”

Editor's note: This article has been updated to clarify that Sarah Dachos now has a job in composting, and to more accurately describe the risk of violence she observed in her neighborhood in the U.S.

Party favor or art? Preserving the craft of the piñata.

What we’re willing to spend on something becomes a message of worth tied to the object’s creator. In expanding their art, piñata makers ask viewers to reconsider these traditional art objects – and the people who make them.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

Lower the bat, take off the blindfold, and appreciate the artistry of the piñata – a form that dates back hundreds of years. Piñata makers are pushing the limits of the party pieces, creating sculptures of wood, foam, wire, and clay for display in art galleries.

Third-generation maker Yesenia Prieto grew up crafting piñatas whose modest retail price belies hours of handiwork. While she and her team still make smashable piñatas for parties, their custom, complex pieces reflect the artistic potential of the craft. They’ve had two installations at a local Los Angeles gallery and have an upcoming show in San Diego.

“What we’re doing is trying to show you what they’d look like if they were valued more,” says Ms. Prieto. “If [people] understand how it’s made, they know it’s not machines just cranking these things out.” She and other makers hope they can both create art and bring a wider respect and dignity to a craft long viewed as cheap and disposable.

“There is a shift taking place,” she adds. She’s seeing piñatas in galleries more often. But “there’s [still] a need for us to push hard to survive.”

Party favor or art? Preserving the craft of the piñata.

Would you take a sledgehammer to the David? A flamethrower to the Mona Lisa? A shredder to the latest Banksy? (Actually, scratch that last one.)

Why then, some people are beginning to ask, would you want to pulverize a piñata?

Alfonso Hernandez, for one, wants you to lower the bat and take off the blindfold and appreciate the artistry of a form that dates back hundreds of years.

The Dallas-based artist has crafted life-size piñata sculptures of Mexican singer Vicente Fernández and Jack Skellington from “The Nightmare Before Christmas.” He wants the public to help turn an industry into art.

“Piñata makers never treated it like an art form,” he says. “They’re taught to make it fast. It doesn’t matter what it looks like, just hurry up because they’re going to break it.”

Unsatisfied with the generic mass production that has characterized their discipline for decades, piñata makers are pushing the artistic limits of the party pieces. These piñatas, bigger and more detailed, are made out of wood, foam, wire, and clay, and sculpted to look like beloved icons and life-size low-riders. Some move, some are political, and some even talk. Rihanna is a fan, as are, increasingly, art galleries.

For generations, the real cost of bargain piñatas has typically been borne by the piñata makers themselves working long, arduous hours for less than minimum wage. By proving that piñatas can be more than just clubbable party pieces, people like Mr. Hernandez hope they can both create art and bring a wider respect and dignity to a craft long viewed as cheap and disposable.

“It’s been an underappreciated art form,” says Emily Zaiden, director and lead curator of the Craft in America Center in Los Angeles.

“Piñatas are so accessible. They speak to everybody,” she adds. But there’s also a flip side. Piñatas “can be about appropriation, can be about, I think, the trivialization of a cultural tradition.”

A new generation of Hispanic artists, she continues, “see how much metaphorical potential piñatas have, and how deeply it reflects their identities.”

The piñata-making grind is familiar to Mr. Hernandez. He tried to sell the first piñatas he made for $100, only to end up accepting $40. He quickly learned the importance of speed and volume. He’s wiry and lean – the product of losing about 40 pounds during a sleepless four-year tear when he made piñatas seven days a week. And he speaks with a rattling impatience, like he needs to get his words out as quickly as he once did his piñatas.

Today, Mr. Hernandez works slower, with more care and craft, from his garage workshop in east Dallas. And across the country, other piñata makers are doing the same.

Change in purpose

There are lots of questions around where piñatas come from. They may have emerged in Europe, or China, or the Aztec era – or in all three independently. There are few preserved, written historical records on the origins of piñatas – another sign of how underappreciated the craft has been, Ms. Zaiden believes.

“A lot of this work probably hasn’t been collected or preserved in ways that other types of art have been,” she says.

“It’s all speculation and oral history really,” she adds, “but that goes hand in hand with the idea that these are ephemeral objects.”

For centuries, piñatas were used for religious ceremonies in Mexico. Typically built to resemble a seven-pointed star, symbolizing the seven deadly sins, they would decorate homes – and be smashed – during the Christmas season.

Their religious significance faded over time, and they became the popular children’s birthday party feature. But as the piñata industry commercialized, quality and craftsmanship became secondary to quantity.

Yesenia Prieto grew up in that world. A third-generation piñata maker, she watched her mother and grandmother create in her grandmother’s house in south central Los Angeles, and when she was 19 she started helping herself. It was a constant struggle to survive, she says.

“I was tired of seeing how poor we were,” she adds. “My grandma was about to lose her house. And we just needed to make more money. We needed to survive.”

She describes a week in the life of a typical piñata maker. A four-person crew makes about 60 units out of paper, water, and glue a week. Selling wholesale, they make $600 and split it between the four of them. That’s about $150 for a full week of work.

“People don’t think of piñatas as something artistic most of the time,” she says. “One of the main reasons is because the workers themselves are making so little.”

“What you’re seeing is an art form having to be mass produced and rushed because they’re getting sweatshop wages,” she adds.

Sometimes that is literally the case.

In 2012, three women alleged in a lawsuit that they were forced to make piñatas in an illegal factory in the New York City borough of Queens. Locked in an unventilated basement below a party supply store, they claimed they were forced to work 11-hour shifts for $3 per hour making about 300 piñatas a week. A federal judge ordered their bosses to pay them over $200,000 in damages, attorney’s fees, and other costs.

What the market thinks piñatas are worth

In 2012, Ms. Prieto went independent from her family, and independent from the mainstream piñata industry. She founded Piñata Design Studio and set to making custom, complex pieces that reflect the artistic potential of the craft.

They’ve created pterodactyls and stormtroopers. They’ve made a giant Nike sneaker, and an 8-foot-tall donkey for the 2019 Coachella music festival. They made a piñata of singer Rihanna for her birthday. (She kept it a whole year before finally breaking it, Ms. Prieto says.)

But the need to hustle hasn’t abated, according to Ms. Prieto. They work longer on their piñatas than most makers do – up to 16 hours in some cases – but still struggle to sell them for more than $1 an hour.

They’ve been leveraging the internet and social media – posting pictures of pieces as they’re being made, to illustrate the labor that’s involved – and they’re slowly raising their price point.

“We’re still taking losses on certain things. But that’s the goal,” she adds. “To see our work for what it truly is. ... For this art form to survive, [and fulfill] its artistic potential.”

She’s also now reaching out to other piñata makers about forming a co-op. By working together, she hopes, piñata makers can get paid fairly, at least. Artistic quality could also improve. And as people see elaborate, custom piñatas more often, she believes, demand will grow, and pay will grow with it.

“What we’re doing is trying to show you what they’d look like if they were valued more,” says Ms. Prieto. “If [people] understand how it’s made, they know it’s not machines just cranking these things out.”

“There is a shift taking place,” she adds. She’s seeing piñatas in galleries more often. But “there’s [still] a need for us to push hard to survive. At least that’s how I’m experiencing things right now.”

Look, don’t touch

Artistic piñatas and functional (read: “smashable”) piñatas exist in very different worlds, says Ms. Zaiden. But they can affect one another.

She curated a piñata exhibit at the Craft in America Center last year – including some of Ms. Prieto’s pieces. None of the works were designed to be beaten to smithereens. A larger version of that exhibit will go on display at a museum in San Diego this fall. The piñatas conveyed messages on everything from pop culture and junk food to border policy and reproductive rights.

“People love them, and they become centers of this monumental occasion, this celebration,” she adds. “So maybe there’s a possibility that people appreciate them as something that isn’t just smashed.”

In Dallas, Mr. Hernandez has his own plans, and his own dreams.

His business, No Limit Arts and Crafts, has been blowing up since Texas Monthly profiled him in January. He’s making a giant Day of the Dead-themed Big Tex piñata for the Texas State Fair, and he’s making a piñata of Selena, the slain Tejana singer – a job that he says “terrifies” him because she’s so beloved.

But he wants to focus less on big, custom sculptures. Now he wants to sell DIY kits so kids can make their own piñatas at home. He not only wants families to get higher quality pieces for their celebrations, but also hopes to help them scratch the same artistic itch he’s had since he was in elementary school. The way Lego has fueled children’s imaginations for decades, he wants piñatas to do the same.

“One of the most important feelings that you get from this ... is, ‘Wow, this thing is amazing. I can’t break it,’” he says.

“To sell [that] feeling is what I’m looking for.”

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

South Africa’s chance for honest governance

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

South Africa’s ruling African National Congress faces a pivotal decision – and an opportunity to renew South Africa’s foundational ideals of equality and honest governance after years of ruinous graft.

On Wednesday a special commission concluded its nearly four-year probe into a wide-ranging corruption scheme under former President Jacob Zuma. Its final report, totaling more than 5,000 pages, is a stunning rebuke of the ruling party. It provides a new benchmark for judicial independence on a continent where the rule of law remains fragile.

The commission’s work may offer South Africans a needed reminder of the resilience of their democracy. In a 2019 poll by Transparency International, 57% of South Africans agreed that ordinary citizens can make a difference in the fight against corruption.

Now the corruption probe has challenged the African National Congress to reclaim the high ethical standards it once demonstrated. But the report’s real impact may be in reminding South Africans that integrity – like democracy – is renewable.

South Africa’s chance for honest governance

At the end of its probe into human rights violations committed during the apartheid era, the South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission referred about 300 cases for prosecution in 2003. That was in line with the panel’s key trade-off. Perpetrators could seek amnesty in exchange for full disclosure of politically motivated crimes. If they did not, the courts were waiting.

But the prosecutions never came. As evidence later showed, the ruling African National Congress (ANC) blocked trials of former apartheid agents to avert possible legal action against its own party cadres – some of whom had become senior government officials. That decision, critics still argue, undermined the rule of law early in the country’s new era of multiracial democracy.

Two decades later, the ANC faces a similar pivotal decision – and an opportunity to renew South Africa’s foundational ideals of equality and honest governance after years of ruinous graft.

On Wednesday a special commission concluded its nearly four-year probe into a wide-ranging corruption scheme under former President Jacob Zuma. Its final report, totaling more than 5,000 pages, is a stunning rebuke of the ruling party. It provides a new benchmark for judicial independence on a continent where the rule of law remains fragile.

“There were multiple ‘warning signs’ in the public domain, which the ANC did not act on in any meaningful way for at least five years,” the panel’s chairman, Chief Justice Raymond Zondo, wrote. “There was arguably, at least, a knowing abdication of responsibility.”

The report details how Mr. Zuma and his cronies siphoned an estimated $30 billion in public funds while undermining the integrity of the intelligence and security services, the national revenue agency, and scores of state-owned enterprises. Few senior ANC officials emerge untainted. The president now has four months to decide whether his party will once again favor its instincts for self-preservation or enable the national prosecutor’s office to clean house.

Beyond that, the commission’s work may offer South Africans a needed reminder of the resilience of their democracy at a time of sinking public confidence. The latest Afrobarometer poll in South Africa, taken a year ago, found that confidence in nearly all public institutions had fallen. Only 38% of those surveyed said they trusted the president, 27% parliament, and 43% the courts.

That pessimism is understandable. After 28 years of ANC rule, the annual growth rate is a tepid 1.9%, unemployment hovers above 30%, and access to education is uneven. Although nearly 90% of South Africans now have electricity, service is frequently interrupted due to lack of enough power.

But as Justice Minister Ronald Lamola argued in a recent speech marking the 25th anniversary of the country’s constitution, the well-being of democracy starts with the exercise of integrity by individual citizens.

“In more ways than one, this young democracy is being suffocated by corruption,” he said. “The corrective action ... lies in citizens confronting corruption directly where it arises. We can’t confront corruption by being tolerant of those amongst us who live on bribes and criminality. Criminality is the absence of humanity.”

In a 2019 poll by Transparency International, 57% of South Africans agreed that ordinary citizens can make a difference in the fight against corruption. Now the corruption probe has challenged the ANC to reclaim the high ethical standards it once demonstrated. But the report’s real impact may be in reminding South Africans that integrity – like democracy – is renewable.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Angel messages – faster than text messages?

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 2 Min. )

-

By Ginger Emden

If it feels as though we’re in over our heads with a task at hand, we can call on God for inspiration that equips us to move forward with confidence, strength, and peace of mind.

Angel messages – faster than text messages?

I vividly remember standing in the hot corridor of the storage rental facility. My husband and I were newly married and needed to store our belongings while we traveled and looked for new housing.

That day, he was clocking hours at work as a service technician, while my work was more flexible. The storage unit filled up quickly with furniture and boxes, and I muddled through feelings of frustration and abandonment. I wanted to text my husband to let him know I was in over my head.

Instead, I did something I’ve often found so helpful in trying moments: I mentally reached out to God, thinking that angel messages – uplifting inspiration from God – might be faster and more effective than text messages.

Mary Baker Eddy, the discoverer of Christian Science, describes divine communication in her book “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” which includes a Glossary of spiritual definitions for biblical terms. The definition of “angels” is: “God’s thoughts passing to man; spiritual intuitions, pure and perfect; the inspiration of goodness, purity, and immortality, counteracting all evil, sensuality, and mortality” (p. 581).

This was the turning point for me. An angel message came immediately to my thought and heart: I didn’t need to get angry to get the job done. As God’s ideas, or children, we are spiritual and reflect qualities of God, divine Spirit, including strength and intuition.

I felt reassured by this, and calmness and courage took hold.

Then, as I glanced up, I saw my husband’s work truck on the highway adjacent to the storage facility. He was already on his way! I hadn’t texted him – but he, too, had been listening for angel messages. He wanted to help on his lunch break, and we worked quickly together to finish the project.

Mrs. Eddy writes in Science and Health, “If Spirit pervades all space, it needs no material method for the transmission of messages” (p. 78).

Ideas communicated from God are quick and powerful. In addition to sending text messages, maybe we could pause more often to listen for angel messages?

Adapted from the May 16, 2022, Christian Science Daily Lift podcast.

A message of love

Telling refugees’ stories

A look ahead

Here’s a bonus read: The history of abortion in the United States is more complicated than many people realize. Our Harry Bruinius spoke to a legal scholar about the shifts in perception that have shaped public attitudes over time. You can read his Q&A here.

Come back Monday. Taylor Luck will be reporting on Saudi Arabia’s bid to begin a transition to an economy not focused on oil, and what that transformation may mean for young Saudis.