- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 15 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- Why the Republican Party’s future may be decided in Arizona

- Target practice in space: NASA aims to knock an asteroid off course

- They are Black. They are Italians. And they are changing their country.

- Responsible or reckless? India brings back the long-lost cheetah.

- Tracing the cycles of Black empowerment, white backlash

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Pond life: Shoebert the seal and the delights of a New England vacation

Sometimes you just have to get away from daily life. You’re desperate to be somewhere new and exciting.

Even if you’re a seal, and your exotic getaway is a pond next to a parking lot in suburban Boston.

Enter Shoebert. The 4-year-old gray seal apparently crawled up a drainage pipe from the ocean, into a restful resort in Beverly, Massachusetts, named Shoe Pond.

Entranced locals loved him. They quickly dubbed him Shoebert. That’s better than the scientific name for his species, which translates from the Latin as “hooked-nose pig of the sea.”

A T-shirt store started selling Shoebert merchandise. An ice cream shop concocted a special dish in his honor. City Council Chair Julie Flowers announced at a meeting that Shoebert had “brought Beverly together in an exciting way.”

But vacations don’t last forever. Particularly when your natural habitat is rocky saltwater shores. Animal control officials began trying to corral Shoebert late last week. They wanted him out of the pond before it freezes.

They couldn’t catch him. Perhaps he wasn’t ready for the party to end.

Then Friday he crawled out and slithered about 300 yards over a lawn and an asphalt lot to the Beverly police station.

“Thank you Shoebert for having faith in the BPD,” said the Beverly Police Department in a Facebook post.

The gray seal was corralled in an animal carrier without incident and transported to Mystic Aquarium in Connecticut. Researchers there discovered he had been rescued and tagged once before, for facial injuries.

His future plans are unknown. Likely he’ll be returned to the cold waters of the North Atlantic. Then perhaps he’ll work on a memoir. Doesn’t he sound like a children’s book?

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

A deeper look

Why the Republican Party’s future may be decided in Arizona

Once a GOP stronghold, Arizona is now purple – and a battleground between traditional and MAGA Republicans. This conservative divide could shape the future of the Republican Party and the coming elections.

Among the prickly pear and wispy paloverde trees of the Goldwater Memorial in Paradise Valley near Phoenix, one can’t help but wonder what its namesake would think if he focused his lens on Arizona’s Republican Party today.

Barry Goldwater was famously trounced as the GOP presidential nominee in the 1964 contest against President Lyndon B. Johnson. But his conservative ideals set the stage for another proponent of small government – Ronald Reagan. And the five-term senator put his state on a rightward path that would span decades, with mavericks like the late Sen. John McCain later taking up his mantle.

Yet in 2020, Arizona tipped narrowly to Joe Biden, and is now represented in the U.S. Senate by two Democrats.

After so many years of dominance, the GOP’s slippage here has led to furious finger-pointing. The Trump wing puts the blame squarely on “RINO” politicians, who they say have failed to uphold both conservative ideals and election security. The Republican establishment sees the Trump wing and its unsupported claims of voter fraud as dangerous.

November’s elections, which both parties are framing as a fight against tyranny, will also be a pivot point in what independent pollster Mike Noble describes as the “battle for the soul of the GOP.”

Why the Republican Party’s future may be decided in Arizona

In a desert garden of prickly pear and wispy paloverde trees, a larger-than-life statue of Barry Goldwater gazes into a scorching Arizona sky. The Republican titan – deemed by many the father of modern conservatism – holds in one hand a cowboy hat, a nod to his roots in the American West and his commitment to self-reliance. The other hand rests on a camera case.

Senator Goldwater loved taking photographs. He captured more than 15,000 images of the Arizona desert and Native Americans, using his mother’s Brownie box camera when just a boy. His friend, the great landscape photographer Ansel Adams, called him “a fine and eager amateur” who compiled a pictorial record of “historical and interpretive significance.”

Visiting the Goldwater Memorial in Paradise Valley near Phoenix, one can’t help but wonder what the former presidential candidate would think if he focused his lens on Arizona’s Republican Party today.

He was famously trounced as the GOP presidential nominee in the 1964 contest against President Lyndon B. Johnson. But his conservative ideals set the stage for another proponent of small government – Ronald Reagan. And the five-term senator put his state on a rightward path that would span decades, with mavericks like the late Sen. John McCain taking up his mantle.

In recent years, however, the Grand Canyon State has turned from Sedona red to sunset purple, becoming a must-win swing state for both parties. It tipped narrowly to Joe Biden in 2020 and is now represented in the U.S. Senate by two Democrats.

That Republican erosion has ignited an existential “battle for the soul of the GOP,” says independent Arizona pollster Mike Noble.

In many ways it’s the same battle that’s been playing out across the nation ever since Donald Trump burst onto the political scene – but perhaps nowhere as intensely as in Arizona. After so many years of dominance, the GOP’s slippage here has led to furious finger-pointing, as well as a sense of disbelief. The Trump wing puts the blame squarely on “RINO” politicians, who they say have failed to uphold both conservative ideals and election security. The Republican establishment sees the Trump wing and its unsupported claims of voter fraud as dangerous and likely to be rejected by the state’s changing electorate – potentially putting the party on a path to marginalization.

So far, one side seems to have the upper hand. In August’s primaries, four Republican candidates endorsed by former President Trump – for governor, U.S. Senate, state attorney general, and secretary of state – all won handily, despite being significantly outspent by their rivals. All campaigned on a message that the 2020 election was fraudulent – a claim that was tested and refuted by hand counts, forensic tests, and an outside audit. Republican gubernatorial nominee Kari Lake, a charismatic former TV news anchor, has allied herself so closely with Mr. Trump in her campaign that some are now speculating if she wins in November – and polling shows her currently in a dead heat against Democrat Katie Hobbs – the former president could tap her as a potential running mate.

November’s elections, which both parties are framing as a fight against tyranny, will not only be a pivot point in the GOP identity struggle, but will also bear significantly on control of the U.S. Senate, and in 2024, the presidency.

“Arizona Republicans are at a crossroads, in a state where they’ve had unequivocal dominance to now being a battleground,” says Mr. Noble. While the Trump wing appears ascendant, he adds, the real test will come in November, when candidates face a broader swath of voters. “Winning the primary is great, but can you win the general election? Because if not, there is going to be a short life span for this movement.”

Revolution at the grassroots

To understand the forces shaping today’s GOP, new party activist Tommy Andrews recommends watching “2000 Mules” and “Selection Code.”

These films, claiming to show the 2020 election was fraudulent, have been criticized by experts for using misleading data points to draw false conclusions. But they’ve stoked enormous outrage on the right. And as Mr. Andrews points out, it’s not just conservatives who distrust the voting system – other recent films, such as “Kill Chain: The Cyber War on America’s Elections” and “Rigged: The Voter Suppression Playbook,” have highlighted vulnerabilities in America’s elections from more left-leaning perspectives.

“There is tremendous concern over election integrity,” says Mr. Andrews, a businessman who lives in Scottsdale. A well-to-do city of golf courses and spas bordering Phoenix, Scottsdale is part of vast, politically determinative Maricopa County – site of Arizona’s 2020 election recount and audit.

Mr. Andrews grew up in a Republican household and has always valued personal responsibility and small government. But he only recently became involved in politics, adding “precinct captain” to his list of activities outside work, along with cycling and swimming. He’s part of a nationwide grassroots strategy spearheaded by former Trump aide Steve Bannon and Arizona attorney Daniel Schultz to take control of the Republican Party from the bottom up, by filling hundreds of thousands of vacant party committee positions in voting precincts.

Volunteer precinct committee members are the building blocks of the party – they work to get out the vote, set rules, vote on policy positions, and send delegates to the presidential nominating convention.

Before the 2020 election, Mr. Andrews didn’t know what precinct he lived in, let alone what a precinct captain does. But after watching the election results come in with his wife, Kathy, he decided to find out. Both were immediately skeptical when Fox News called Arizona early for Mr. Biden: “We said, ‘That does not feel right.’”

When Mr. Andrews looked into the GOP precinct committee system, he discovered only two out of 15 committee slots in his Del Joya precinct were filled. He had lunch with the chair, got appointed and later elected, and set about finding “like-minded” people for the rest of the slots. As he explains from the cool and airy living room of his Spanish-style home, he vetted possible candidates by asking about their views on the 2020 election, border security, pandemic mandates, and their news sources.

“There is a faction of the Republican Party here that is very unhappy with the establishment,” says Mr. Andrews. He and his team have now filled all the remaining slots and have already changed the rules to do away with proxy voting on the precinct committee, which previously allowed just a few active committee members to hold sway.

Many issues motivate Mr. Andrews and his fellow conservatives (he uses that label deliberately): open borders, critical race theory in education, gender ideology, the administration’s handling of the economy. More recently, he’s been upset by the Aug. 8 FBI search of former President Trump’s Palm Beach, Florida, estate and President Biden’s Sept. 1 speech calling MAGA Republicans a threat to the republic.

But foremost among concerns is the matter of election integrity. While the GOP-backed audit in Arizona officially reaffirmed President Biden’s victory, it also found “significant issues,” explains the precinct captain.

Mr. Andrews served as an observer and then a worker for the audit conducted by Cyber Ninjas, hired by the Arizona Senate. The firm had no previous election auditing experience, and is no longer in business. Mr. Andrews says he personally saw half a dozen boxes of ballots where tally sheets did not match the contents. He extrapolates from his experience a 20% error rate, and more conservatively from the experience of other workers, a 5% mismatch rate. An error rate of 1% is acceptable under Arizona recount law.

Benny White, a Republican data analyst for the Arizona GOP for more than 10 years, was part of a team of experts who reviewed the Cyber Ninjas data and found its audit to be “meaningless” because it was so riddled with problems.

Mr. Andrews may have observed tally mismatches, says Mr. White, but generalizing from that is a mistake. Boxes of ballots are not “widgets coming down an assembly line.” Each is unique, he explains. “You have to look at the whole story, not just at one marble and decide that half the marbles are black.”

But Mr. Andrews is resolute. This November, he predicts, election integrity concerns and a backlash against President Biden will propel “a red wave like none you have seen before.”

Alienated Republicans

Mr. Andrews’ precinct activism is a “snapshot” of what’s happening more broadly in Arizona, according to Tyler Montague, a GOP consultant based in Mesa, which is also in Maricopa County. Since 2018, the MAGA wing of the party has been trying “to purge the party of ‘heretics,’” he says, an effort that’s intensified since the last presidential election.

Mesa is home to a lot of “traditional” Republicans, says Mr. Montague – including many members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, such as himself, who have historical roots there. Many of these Republicans are deeply troubled by the Trump wing’s policy positions on issues from trade to immigration – as well as what Mr. Montague describes as its anti-democratic tactics.

“They are ‘burn it all down’ people. Institution wreckers,” he says. Many “at the top” know their claims of a stolen election are a lie, he says, and yet they have convinced rank-and-file Republicans to believe it. “What’s more critical than our elections, free and fair elections that inspire confidence?”

Mr. Montague did his missionary work in Chile, and as a Boy Scout leader back in Arizona had several “Dreamers” – children whose families brought them to the United States illegally – in his troop. In 2011, he led a successful effort to recall state Senate leader Russell Pearce, the main sponsor of a controversial anti-illegal immigration law.

“People in my neighborhood like immigrants. They don’t like the white nationalist, anti-immigration people,” he says in a phone interview.

The grassroots battle within Arizona’s GOP has been going on for years. In 2016, Tyler Bowyer was the Republican chairman of Maricopa County, and a staunch Trump supporter. He moved to Mr. Montague’s neighborhood and Mr. Montague says he prevented Mr. Bowyer from becoming a precinct committeeman – and from being reelected county chair – by successfully recruiting others to fill the positions.

And yet Mr. Bowyer, also a Mormon, has continued to rise in the party. A leader in Turning Point USA, which organizes conservatives on college campuses, he’s a loyal ally of Ms. Lake and Arizona GOP Chair Kelli Ward, who has been subpoenaed by the Justice Department over a slate of “fake electors” whom Trump supporters planned to send to Congress on Jan. 6, 2021.

All this has made Mr. Montague feel alienated from his own party. And while he says he’s still in this for the long run, others like him have “become disenchanted.” It didn’t help when Ms. Lake, after winning her primary bid, crowed that “we drove a stake through the heart of the McCain machine.”

One friend, Yasser Sanchez, a fellow Mormon and immigration lawyer in Mesa, left the GOP to become an independent. Mr. Sanchez says he recently had lunch with a loyal Republican who won’t vote for Ms. Lake and isn’t sure what to do.

GOP consultant Sean Noble notes that 60,000 Arizona voters abstained from choosing a presidential candidate in 2020, while selecting candidates for other offices. “That’s a uniquely Trumpian problem.”

Mr. Sanchez, for his part, is not on the fence. “I wrote out a check to Katie Hobbs, and I called her and said, ‘Hey, let’s get working. I’m independent.’” He was hoping the GOP primary would produce a candidate he could vote for. Instead, they’ve “all kissed the ring of Trump and the big lie of the stolen election.” That, he says, is “dangerous.”

Kari Lake: Can she broaden her appeal?

A Kari Lake ad about border control shows some Barry Goldwater attitude. She strides toward the camera in her dusty cowboy boots and jeans, defiant and direct in her Arizona independence. But there’s far more of President Trump – she promises as governor to declare an invasion at the border, finish his wall, blow up drug cartel tunnels, and send in the National Guard to halt illegal immigration. The ad ends with his endorsement.

Ms. Lake herself is authoritative, convincing, and completely at ease speaking directly to the camera, which she did for two decades as a news anchor at the local Fox affiliate in Phoenix.

“She’s trying her best to meld themes that were present in the Arizona Republican Party with Goldwater, and again McCain and that maverick streak, with an adherence to the prime tenets of a Trumpist ideology,” says historian Brooks Simpson, at Arizona State University.

Her maverick streak resonates with Richard Truelick, one of Mr. Andrews’ new precinct committeemen who lives across the lake from him in a gated community of active retirees. He’s a genial man, formerly a VP with Beatrice Foods, who chats with neighbors when he walks his dogs, Lilly and Max. “The thing I like about her, she’s not a politician. She has no obligation to anyone on anything.”

Mr. Noble, the pollster, says Ms. Lake’s immediate task is to unify her party, which he describes as being in a state of “civil war.” His research shows stark differences between Trump supporters and “party” supporters, primarily over whether the election was stolen (82% of Trump supporters say it was, but only 50% of party supporters do). After that, she needs to reach for the independents – about a third of the electorate, he says. The last two elections underscore this necessity, he points out.

In 2016, Rep. Martha McSally moved right to win the GOP primary for the U.S. Senate – and stayed there for the general election. She lost to Democrat Kyrsten Sinema (Arizona’s first Democratic senator in three decades). In 2020, Ms. McSally again stuck firmly to then-President Trump, and lost her second Senate bid to Democrat Mark Kelly.

In recent polls, Senator Kelly is comfortably leading his Trump-endorsed opponent, Blake Masters, one of several GOP candidates to whom Senate leader Mitch McConnell may have been referring when he lamented that “candidate quality” may prevent Republicans from taking control of the Senate in November.

“That’s the problem with the base-only strategy,” concludes Mr. Noble.

Ms. Lake is one of four GOP swing-state gubernatorial candidates – the others are in Pennsylvania, Michigan, and Wisconsin – who say that Mr. Biden was not fairly elected. Had she been governor at the time, she has said, she would not have certified the 2020 election.

While this stance encourages some voters, it scares others – who perceive a militancy in her tone. In a statement after the FBI’s search of Mar-a-Lago, Ms. Lake described the government as “tyrants [who] will stop at nothing to silence the Patriots who are working hard to save America,” adding, “We will not accept it.” She later agreed on a podcast with Steven Crowder that Republicans should “disband the FBI.”

Arizona’s long slide from Goldwater

Arizona has always been a conservative state, says Professor Simpson, but Goldwater did not embrace deep-state conspiracy theories, and once considered doing a whistle-stop debate tour across America with President John F. Kennedy. He fought vigorously for conservative values on the economy and foreign policy – but was not nearly as interested in culture war issues such as abortion. The senator was one of three GOP members of Congress who went to the White House to tell Richard Nixon he did not have the votes to survive impeachment. President Nixon resigned the next day.

Today’s Arizona Republican Party is far different from that of Goldwater. Demographically, it’s got fewer college-educated white people and more Hispanics and working-class voters. Matt Salmon, a former Arizona congressman who pulled out of the GOP race for governor, told the Monitor that when he was first elected in 1994, “it was all about ideas” – with Republicans running on the Contract With America. “Now it’s personality-driven.”

The state GOP has been “drifting rightward in more militant ways” since the 1990s, observes Professor Simpson. “This isn’t something that Donald Trump created. The party’s been sliding in this direction for quite some time.” He cites the nearly 25-year tenure of Maricopa County Sheriff Joe Arpaio as an example.

The state’s establishment Republican leadership has called for party unity, with former Gov. Jan Brewer invoking Goldwater’s concession speech, according to an attendee at a GOP victory rally in Surprise, another Phoenix suburb. Just after the primary, the former governor told The New York Times that Ms. Lake had gone “so far to the right that I don’t know if she can recover,” and said she hoped she would tell voters the truth about the 2020 election.

But Latino voters could help Ms. Lake. Mr. Trump made inroads with Hispanics in 2020, and economic conditions could drive them to the polls this time around, says Republican Lea Márquez Peterson, the chairwoman of the Arizona Corporation Commission – and the first Latina elected to a statewide position.

Many Hispanics in Arizona are small-business owners and workers, she explains, and their desire for lower taxes, less regulation, and small government aligns with the Republican Party. Latino businesses acutely feel the effects of inflation and are still reeling from the pandemic and supply chain disruptions, says Ms. Márquez Peterson, who used to head up the Tucson Hispanic Chamber of Commerce and ran a chain of gas stations and convenience stores.

But both parties have some work to do. “I haven’t heard a lot of excitement yet,” she says, lamenting the “divisiveness” of the primary. While she did not support Ms. Lake in the primary, she is urging Latinos to vote the GOP ticket. “I do not want to see key races lost to Democrats.”

It’s important to remember that every election is a choice, says Mr. Noble, the pollster – a dynamic that could work to Ms. Lake’s advantage. He says Democrats made “a very big mistake” by nominating Ms. Hobbs, who has declined to debate Ms. Lake and who comes across as “meek and weak.” “From a personality or charisma perspective, those two candidates couldn’t be more different,” he says.

For Democrats, a fight for democracy

Here’s what Ms. Hobbs says Arizona voters are worried about: reproductive freedom, public education, the dwindling Colorado River and ensuing water crisis, and of course, the price of everything – from groceries to housing. But, she says, there’s also an overarching concern: democracy.

As Arizona’s secretary of state, Ms. Hobbs was in the thick of the 2020 dispute. She has maintained consistently that the election was fair. The sample hand recount in Maricopa County, for example, found a 100% match with the machine ballot count.

Arizonans are tired of endlessly litigating the 2020 election and want leaders who will tackle real issues, says Ms. Hobbs, in an interview at a Phoenix cafe. “This race is not about Democrats or Republicans; it’s about sanity versus chaos.” She characterizes the November election as a choice between who will move the state forward and who will “drag us backwards to the Civil War.”

(The Monitor’s request to interview Ms. Lake was turned down. Questions sent to the campaign office, at her spokesperson’s direction, went unanswered.)

Ms. Hobbs warns about a better-coordinated Republican effort to overturn elections this year and in 2024. The Trump-endorsed candidate vying for her current job, Mark Finchem, says the 2020 election was stolen and has called for Ms. Hobbs’ arrest.

All of this is of grave concern to Daniel Martineau and his wife, Laura Medved, neighbors to Mr. Truelick, one of the new GOP precinct committeemen in Scottsdale. Mr. Martineau plays golf with the Truelicks and they are all friendly, even if their political views differ. The couple, who both work in real estate and will soon be new grandparents, are registered Democrats but consider themselves centrists and have voted on both sides of the aisle. Two years ago, they put out the lone Biden sign in their gated neighborhood.

“I worry about all future elections,” says Ms. Medved, at their kitchen table. Her husband warns of “fascism” in a GOP that no longer allows dissenting views. But Mr. Martineau is also worried about Ms. Hobbs’ ability to pull out a victory. He laments that she lacks the charisma and positive message of a candidate like Barack Obama. He notices his Democratic friends tuning out politics – though his wife says the Supreme Court ruling on abortion could help turn out the vote.

For his part, Mr. Truelick sees Goldwater conservatism in Mr. Trump’s “America First” approach. He quotes from Goldwater’s nomination acceptance speech: “Extremism in defense of liberty is no vice.” Still, he also wonders if today’s GOP in Arizona will be able to hang together.

“There’s a lot of energy in our party here. I hope it doesn’t come apart.”

Target practice in space: NASA aims to knock an asteroid off course

By colliding into a distant asteroid that poses no threat, NASA’s DART mission is tapping scientific ingenuity to test the idea of deflecting space rocks for planetary defense.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Monday night, NASA hopes to complete a mission that could someday help save the planet.

If all goes well, NASA’s DART probe will smash into an asteroid nearly 7 million miles from Earth, knocking the space rock onto a new path.

The asteroid, called Dimorphos, is no threat to Earth. But that is why NASA is using it for target practice. If the space agency can successfully nudge Dimorphos onto a new track, it can learn crucial lessons about how to defend Earth if a more dire situation were to occur.

The public can join scientists in a long-distance viewing of the collision tonight (at 7:14 p.m. ET) via NASA’s website. Measuring the outcome may take a week or so. Telescopes on Earth will observe how much the collision slowed Dimorphos in its orbit around an adjacent larger asteroid.

It has taken years of planning and scientific collaboration to get to this point.

“We have collided with things before, but not with the intent of moving them,” says Thomas Statler, DART program manager at NASA. “We are moving an asteroid. We are changing the motion of a natural celestial body in space. Humanity has never done that before.”

Target practice in space: NASA aims to knock an asteroid off course

Hollywood comes to life Monday night, as NASA attempts to smash a small spacecraft into an asteroid nearly 7 million miles from Earth, and knock the space rock onto a new path.

It’s a mission that could someday help save the planet.

The asteroid, called Dimorphos, is not heading toward Earth. In fact, it is no threat to Earth at all. But that is why NASA is using it for target practice. If the space agency can successfully nudge Dimorphos onto a new track, it can learn crucial lessons about how to defend Earth if a more dire situation were to occur in the future.

By science fiction standards, the mission might appear a bit mundane – no nuclear explosions or roughnecks in space. The DART craft will simply crash into the asteroid. But unlike Hollywood movies, this story is advancing a real-life plotline of safeguarding Earth. There’s a real-life planetary defense officer involved. And in place of special effects, scientific hurdles are being cleared by real-life innovators.

“We have collided with things before, but not with the intent of moving them,” says Thomas Statler, DART program manager at NASA. “We are moving an asteroid. We are changing the motion of a natural celestial body in space. Humanity has never done that before,” he said in a Sept. 22 press briefing.

The mission itself will be successful if DART collides with the asteroid.

“It’s really hard to hit a very little object in space and we are going to do it,” says Elena Adams, the mission systems engineer on the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory management team, which has developed and led the project for NASA.

While the goal is straightforward, the road to Monday was no simple one. And the mission’s work won’t end with the crash.

“There’s a lot of stuff going on,” NASA’s Dr. Statler explains in an interview. “There are the astronomical observations. There’s the physical computer simulations of the impact. There’s what happens to the spacecraft. And the more you start digging into this from the science side, the more intricate each one of these things becomes.”

A smashing success?

One early task for mission scientists was locating the right rocky object in space.

They found it in Dimorphos, one of two asteroids that move together in what’s called a binary asteroid system. (Hence the name DART, which stands for Double Asteroid Redirection Test). Dimorphos orbits the larger Didymos in a system that was first spotted in 1996.

By hitting Dimorphos, scientists will be able to observe how much that orbit changes.

A second challenge is the collision’s physics: changing the course of a large object with a much smaller one. One everyday example of redirection is any time one moving billiard ball hits another moving one – but in this case the two objects aren’t similar in size. The core of the DART probe is about the size of a refrigerator. Dimorphos is about 525 feet in diameter.

What DART has going for it is speed. By having DART collide with the asteroid at an expected 4 miles per second (15,000 miles per hour), the goal is an impact that reduces Dimorphos’ speed by a fraction of 1%.

That could be enough to prove this concept of asteroid redirection for future planetary defense. In other words, if a Dimorphos-size asteroid were heading toward Earth, that would be a real threat. And slowing it just a fraction when it is still far away would be enough to avert a catastrophic impact.

Staying on target

Mission engineers have developed targeting algorithms for the craft to guide itself and ensure it hits Dimorphos, not Didymos. A large solar array will help the craft build velocity, powering an electric propulsion engine.

“A lot of new technologies have been tested on this spacecraft ... the new solar panels, new propulsion making the spacecraft more autonomous to be able to actually do this right,” says Jay McMahon, an aerospace engineer at the University of Colorado Boulder who is helping analyze the mission. “We can’t have humans operating a joystick because things are happening so fast, so the spacecraft has to make its own decisions.”

The most challenging aspect might be the steering. Largely on its own, the spacecraft will have to hit a relatively small mass of unknown shape. “A huge piece of what the DART piece is demonstrating is, do we have what it takes to autonomously navigate our spacecraft to autonomously crash into this small body?” says mission scientist Mallory DeCoster, who will help investigate the impact.

Calculating the results from Earth

One of the big tests for researchers won’t come until after tonight’s collision: measuring what happened.

Dimorphos orbits once every 11 hours and 55 minutes. The goal is to slow Dimorphos’ orbit by as much as 10 minutes. Scientists will confirm whether they were successful with Earth-based telescopes, measuring the variations in brightness that happen as Dimorphos orbits the larger asteroid. Definitive results won’t be available for a week or more.

Glimpsing changes in a relatively small object 7 million miles away isn’t easy, which made this part of the mission a hurdle.

“I think it became a challenge for the team to kind of circle back and say, OK, how do we combine all of these different pieces of understanding to wind up with a measurement ... that’s definitive,” Dr. Statler says. “And I think that took quite a long time and quite a lot of development of workflow and information flow.”

Journey began long before launch

The road to DART began in 2005, when Congress tasked NASA to test and confirm a method to protect Earth in case of an asteroid impact. The years since have been spent figuring out how to do it, with the mission formally starting in 2015 and the spacecraft launch last November.

“We do things because they’re hard,” says DART Program Manager Ed Reynolds, who is thrilled the efforts are finally coming to fruition. “We are at the point where technology is emerging so that we can use these emerging technologies to protect ourselves against these threats.”

NASA scientists – and the public – will get a front-row seat to the collision, thanks to an onboard camera named DRACO (Didymos Reconnaissance and Asteroid Camera for Optical navigation) and a live feed.

Rallying to save the planet from asteroids – or failing to do so – has for decades seeped into public thought through movies such as “Armageddon” and the more recent “Don’t Look Up.” But the job is a real one.

And for one night at least, the DART mission has scientists and amateur asteroid watchers alike thinking “Do look up.”

John Stoffel is an avid sci-fi reader and one of those excited watchers. “It’s such an interesting mission,” he says. “And since we’ve only visited a handful of asteroids, each one tells us more about the solar system and what we can maybe expect to find there as we explore more.”

The collision is scheduled to occur at 7:14 p.m. ET Monday. You can watch it here, live.

They are Black. They are Italians. And they are changing their country.

It’s not easy for Black Italians to grow up feeling Italian when significant portions of Italy treat them as outsiders. But legally, artistically, and socially, Black Italians are staking their claim to Italy.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 8 Min. )

Even as a new, far-right government comes into office in Italy after Sunday’s elections, Black and multicultural Italians are asserting their place in their country’s society.

By pushing for legal changes to systemically racist citizenship laws, providing support for Black Italians who feel isolated, or using media like Italian fashion to bridge divides, they are staking their claim in a country that sometimes tells them they’re not wanted.

Black Italians include people who were born and raised in Italy, but not only. The mix encompasses people who feel Italian but also hold a pride in their Blackness and a broader sense of connection to a Black diaspora, says Camilla Hawthorne, who studies migration and citizenship.

Italy does not collect racial data in its population census, so it is hard to estimate the number of Black Italians. But citizenship rights activists put children born and raised in Italy but lacking citizenship at about 1 million.

“For this generation of young people who were born and raised in Italy ... they see themselves as totally Italian,” says Dr. Hawthorne. “But there is always this moment that happens ... where they realize that even though they feel totally Italian, they are not viewed by the rest of the world as Italian.”

They are Black. They are Italians. And they are changing their country.

Michelle Ngonmo fights for inclusion. Her weapon is fashion; her battleground is the catwalks and showrooms of multicultural Milan.

“We are in a society where everything is imagined and imaged as all white,” says Ms. Ngonmo, sitting in a white suit in an office where the corners are reserved for clothes racks loaded with the outfits for Afro Fashion Week. “And there is a real struggle between the people-of-color Italians and [white] Italian society. Asian Italians, Black Italians are really struggling to be accepted as Italians.”

That’s one of the reasons why in 2015 she created the Afro Fashion Association, with a base in Italy and Cameroon. The organization represents 1,400 designers in Africa or the African diaspora. In Italy, it works with about 500 multicultural Italian designers. “People tend to think that Afro culture is just about wax fabric,” she says. “They think that it is the boubou or the foulard or the turban that you put on your head. And they look at it in a folkloristic way, not as something that can be really part of fashion.”

But that is slowly changing. In 2020, in collaboration with the Camera della Moda (Italy’s national fashion chamber), her association launched “We Are Made in Italy,” a fashion project highlighting the work of Italy’s five top multicultural talents. The Afro Fashion Show 2022 marked the first time that the collections of the “fab five” hit the catwalk, due to COVID-19. “Their creativity is super rich,” she says with pride. “These designers have two or three cultures inside. And the creativity is the mix of those cultures.”

The battle against racism and for equal rights for Black Italians extends far beyond the catwalks of Milan. Even as some of their fellow citizens have trouble envisioning Italians as anything other than white, Black and multicultural Italians are asserting their place in their country’s society. By pushing for legal changes to systemically racist citizenship laws, providing support for Black Italians who feel isolated, or using media like Italian fashion to bridge divides, they are staking their claim in a country that sometimes tells them they’re not wanted.

“For this generation of young people who were born and raised in Italy ... they see themselves as totally Italian,” says Camilla Hawthorne, who studies the racial politics of migration and citizenship at the University of California, Santa Cruz. “But there is always this moment that happens in school, whether it is a classmate or teacher, that pulls them out of this sense of, oh, I am just like another kid, where they realize that even though they feel totally Italian, they are not viewed by the rest of the world as Italian. They are always seen as different, as outside, as other, as immigrants.”

“They hardly ever recognize anyone like me”

Today, notions of national belonging in Italy center on whiteness, even in the country’s citizenship law. The country does not grant nationality based on being born within Italian borders, but rather on bloodline.

In practice, this means that the great grandchild of an Italian who migrated to Argentina, even if she or he does not speak Italian and has never set foot in Italy, faces fewer bureaucratic hurdles to get Italian citizenship than the child of African nationals who was born and schooled in Italy, and who speaks only Italian with a local accent to boot. Those in the latter’s situation only have a year to apply for citizenship once they turn 18, but the process is riddled with pedantic bureaucracy that many consider institutional racism.

Dr. Hawthorne, who was brought up in the United States as the child of an African American father and an Italian mother, has been grappling with what it means to be Black and Italian her whole life. She ended up writing a book on the experiences of Black people who were born and raised in Italy but struggle for citizenship. While family histories vary widely, there are some common denominators in a generation often labeled “second-generation migrants” rather than first-generation Italians, she says. She prefers to use the term Black Italians in relation to a person’s sense of identity and belonging over citizenship status.

Black Italians include people who were born and raised in Italy, but not only that. The mix encompasses people who feel Italian but also hold a pride in their Blackness and a broader sense of connection to a Black diaspora, she says. They may have roots in Africa, the Caribbean, Asia, or Latin America. Or they may be children of migrant workers who came to Italy well before the 2014-15 refugee crisis; Africans who pursued university degrees and made a home in Italy; descendants of Italians who settled in the former colonies of Eritrea, Somalia, Libya, and Ethiopia; or descendants of African-American soldiers who moved to Italy after World War II or the Cold War.

Italy does not collect racial data in its population census, so it is hard to estimate the number of Black Italians. But citizenship rights activists put children born and raised in Italy but lacking citizenship at about 1 million.

Though citizenship reforms finally got a spot on the legislative agenda under former Prime Minister Mario Draghi, the prospects of change collapsed along with his government this summer. Now, with a right-wing coalition led by a party which regularly airs racist views set to take power, political change appears off the table.

“In this country when you start talking about citizenship, it becomes a hot matter,” says Hilarry Sedu, a Napoli-based lawyer. “No one really wants to put their hands on it because part of the country is a bit racist.”

Mr. Sedu was born in Nigeria but arrived in Italy at the age of six months. Eventually, he was able to acquire Italian citizenship after proving that he had been a resident for 10 years and paid taxes for three. Today he is one of about two dozen Black lawyers out of 260,000 lawyers working in Italy and part of a broader community pushing to resolve the citizenship question for Black Italian minors whose struggles are not dissimilar to the Dreamers generation in the U.S.

“Most feel that Italian citizens are those with the white skin,” he says. “They hardly ever recognize anyone like me, a Black Italian, [as Italian], so it becomes hard to tell the voters that there is something going on, that Italian citizens are not only those who have the white skin.”

TikTok and cocktails

It is not just a matter of persuading white Italians. Ronke Oluwadare, a psychotherapist in Milan, works with Black Italians to help them work through feelings of alienation from their country and community. “Identity is one of the topics I often navigate with my patients because they don’t feel whole,” says Dr. Oluwadare, noting that African Italians hail from families not only from different countries but also varied socioeconomic classes.

“I usually use this image of a cocktail, right? Like you have different ingredients and then you use different portions to make different cocktails. ... When you are a second generation, part of your journey is deciding which cocktail you want to make.”

Today Black Italian children have comedian Khaby Lame and other influencers on TikTok to show them that they are not alone, that success is possible despite structural and everyday racism. Born in Senegal and brought to Italy as a baby, Mr. Lame shot to fame with silent but funny spoofs of “life hacks” and other social media videos. He gained international recognition as the most followed TikToker in the world, described as “from Italy.” (Though like many young Black people in Italy, he did not have Italian nationality – until recently. It was granted in August, shortly after he reached the pinnacle of TikTok.)

Whether on TV or TikTok, representation matters. But what matters more in Dr. Oluwadare’s view is education: proper discussions of Italian colonialism in the classroom, lessons on Africa that recognize the achievements and diversity within it, and better responses to racial bullying. The murder of George Floyd in the U.S. resonated in Italy for a reason.

“Before that tragedy, all these people thought they were the only one in the room, in each room,” she says. “Then they figured out, ‘Wait, we’re not.’”

“The mask shows who you are”

For Paul Roger Tanonkou, identity and migration played directly into his choice of the logo for his fashion brand: an African mask. Masks in African culture once served as passports, a manifestation of a person’s origins necessary to enter the villages of other tribes. “In Europe, the mask hides who you are,” notes Mr. Tanonkou, who grew up among the fabrics of his mother, a seamstress in Cameroon. “In Africa, the mask shows who you are. The issue of passports, identification, already existed in Africa.”

Mr. Tanonkou, whose printed silk shirts combine bright designs with soothing color palettes, sees fashion as a force with the power to celebrate difference but also create unity across cultures. “We hope to create a fashion that is inspired by Africa but that is accessible to everyone,” he says. “Sometimes I walk past someone on the street wearing one of my shirts and I just smile.”

Nigerian-born Joy Meribe went to fashion schools in Modena and Bologna after first getting an MBA in international business in Italy. Today she has her own brand. Ms. Meribe says her experience shows that being Italian and Black can go hand in hand.

Though she is fluent in Italian, she says Italians consider her Nigerian. Nigerians sometimes see her as Italian due to her penchant for dramatic hand gestures, although she is not a citizen. Her son cheers for Italy when it plays against Nigeria in soccer, and her Italy-born daughter who recently turned 18 has applied for Italian nationality.

“I’ve come to love Italy like home,” Ms. Meribe says. “My children were born here. They are Black. But in all of their mannerisms, in their tastes, in everything they do, they are Italians.”

Responsible or reckless? India brings back the long-lost cheetah.

Advocates of India’s cheetah reintroduction project say they’re driven by a sense of national responsibility. But others argue the single-minded push to bring back the big cat is more reckless than responsible.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

-

By Bilal Kuchay Contributor

Decades after the species was declared extinct in India, eight cheetahs scurried into the Kuno National Park in Madhya Pradesh.

More will follow, but these initial eight – which were flown in from Namibia – represent a big feather in India’s cap to restore a lost treasure. They’ll be kept in an enclosed area to acclimate to the local environment before being released into the open and monitored via tracking collars.

S.P. Yadav, member secretary of the National Tiger Conservation Authority and head of the cheetah reintroduction project, says the “only mammal that has been lost in independent India is the cheetah. So it becomes our moral and ethical responsibility to bring them back.”

However, the first-of-its-kind transplant also has many critics. Some believe the $11 million project is a waste of taxpayer money, and question whether the long-extinct species can thrive beyond captivity. Others feel India’s first priority should be protecting the species that still naturally exist on the subcontinent, including its endangered grassland habitats.

For Wildlife Conservation Trust President Anish Andheria, the project’s success hinges on whether it helps raise awareness and funds to protect the grassland biome. “Otherwise, an addition of one more carnivore … is not going to solve much.”

Responsible or reckless? India brings back the long-lost cheetah.

The world’s fastest land animal is making its way back to India – slowly.

On Sept. 17, decades after the species was declared extinct on the subcontinent and 13 years after conservation efforts to reintroduce the big cat began, eight African cheetahs scurried into the Kuno National Park in Central India’s Madhya Pradesh.

More will follow, say conservationists, but these eight – five females and three males – represent a big feather in India’s cap to restore a lost treasure. However, the first-of-its-kind transplant from Namibia also has many critics. Some believe the $11 million project is a waste of taxpayer money, and question whether the long-extinct species can thrive beyond captivity.

But proponents say they have a responsibility to try.

“The only mammal that has been lost in independent India is the cheetah. So it becomes our moral and ethical responsibility to bring them back,” says S.P. Yadav, member secretary of the National Tiger Conservation Authority and head of the cheetah reintroduction project.

He hopes the project will also be an inspiration for other countries that have lost important animals.

Historic milestone

Cheetahs were declared extinct in India in 1952, only five years after the country gained independence from the British. Plans for repopulation began that same year.

There are fewer than 8,000 cheetahs left in the world today, including about a dozen Asiatic cheetahs, a slimmer subspecies that once roamed India and is now found only in Iran. In the 1970s, India attempted to get Asiatic cheetahs from Iran in exchange for Asiatic lions, but negotiations failed after the shah was deposed.

The current plan to use African cheetahs has been in the works since 2009.

The imported cats were accompanied by wildlife experts, veterinary doctors, and biologists during their transcontinental flight from Namibia to the Indian city of Gwalior, where they were transferred by helicopter to Kuno National Park, a sprawling sanctuary populated with prey such as antelope and wild boars. India’s Environment Ministry says this is the first time a large carnivore has been transported across continents in order to establish a new population.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi, who released the cheetahs into the park, called their arrival a “historic” moment for India.

Yadvendradev Jhala, dean of the Wildlife Institute of India and one of the experts tasked with this conservation initiative, says they have a permit to acquire 20 cheetahs – the eight from Namibia and 12 more from South Africa, which will arrive at Kuno National Park later this year.

The Indian government plans to introduce at least 50 cheetahs into various national parks over the next five years.

Initially, they’ll be kept in an electrified enclosed area so they can acclimate to the local environment before being released into the open. The Namibian felines have been fitted with tracking collars and will be monitored 24/7 by officials.

“India now has the economic and scientific ability … to restore our natural heritage,” Dr. Jhala says, adding that the causes of their initial extinction – mainly overhunting – have been addressed through strict laws. He expects the cheetah restoration to boost ecotourism and local livelihoods.

But not everyone is on board.

“Fatally flawed”

Indian conservationist and big cat expert Valmik Thapar says the project is “fatally flawed” because the country lacks the vast habitat or wild prey needed to sustain a significant cheetah population.

“Even in the best cheetah country, the Serengeti cheetahs are struggling,” he says. “So what is the sense in bringing them to India unless you want them in captive enclosures?”

The cheetahs are expected to remain in enclosures for three months, where food is provided. “The problem will come after three months when they are released and have to hunt forest deer, or encounter leopards and hyenas,” says Mr. Thapar.

Others believe the government’s first responsibility should be to protect the species that still naturally exist on the subcontinent, including those found in its disappearing grasslands.

Abi Tamim Vanak, a wildlife biologist, says the cheetah project has been “touted as an important opportunity” for saving India’s endangered savanna ecosystems, but organizers have yet to propose a clear plan for how they’ll conserve these biomes beyond the protected reserves.

This also throws cheetahs into an ever-shrinking habitat.

“The government has gone with the old ‘fortress’ conservation model,” he says, referring to the controversial belief that conservation is best achieved by creating separate spaces for humans and wildlife. Authorities are bringing cheetahs “into what will only remain glorified safari parks in the foreseeable future,” Dr. Vanak says.

Grassland restoration

Proponents hope the grassland restoration and cheetah repopulation will flourish in tandem.

“When the cheetah was not there, there was not much motivation to protect the grassland habitat,” says Dr. Yadav, the project’s leader. “Now that you have a charismatic species, there is a drive to protect that landscape. … I’m 100% sure that this will help revive other endangered species.”

For Wildlife Conservation Trust President Anish Andheria, the project’s success hinges on whether it leads to an increase in the country’s grassland habitats.

“If the cheetahs can be used to get funds to protect grasslands, and we can expand the grasslands in the next 10-12 years, then the cheetah [program] would have fulfilled its purpose,” he says. “But otherwise, an addition of one more carnivore … is not going to solve much.”

Book review

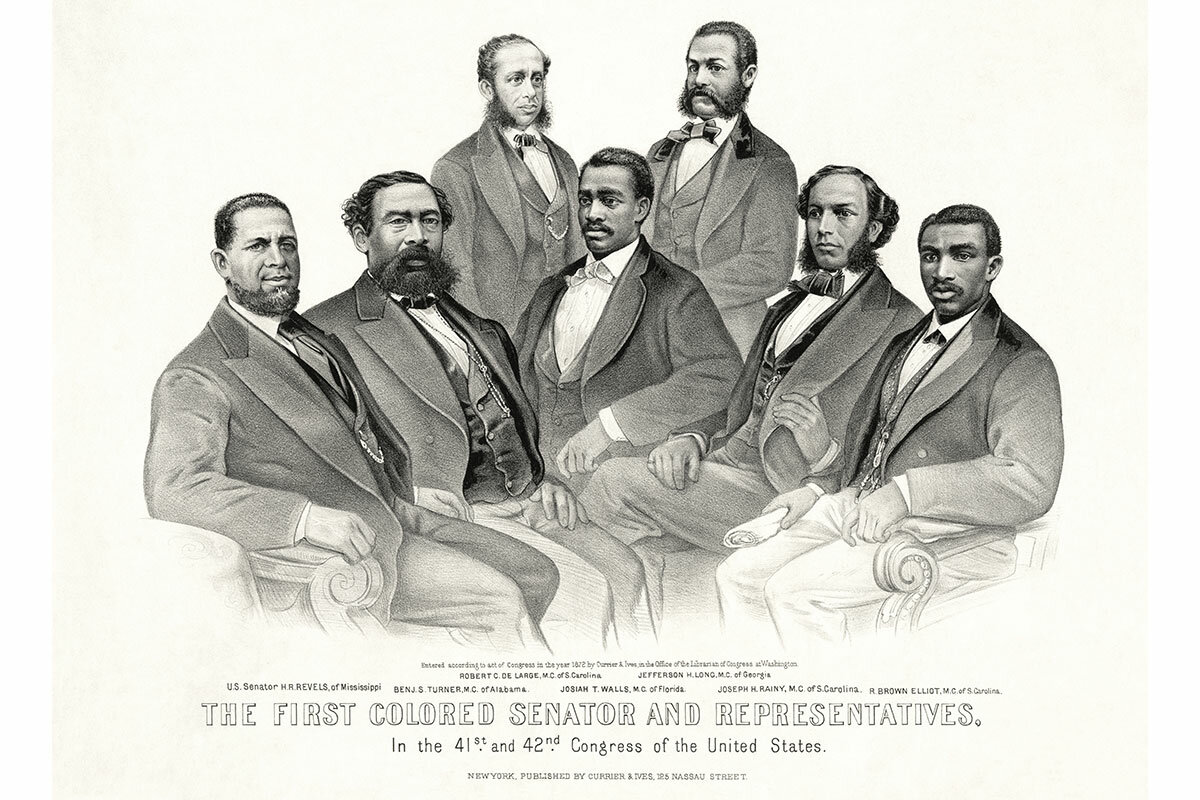

Tracing the cycles of Black empowerment, white backlash

Understanding the patterns of history gives us insights into the present day. A historian ties together three distinct eras in which Black progress was disrupted by white opposition.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

At the heart of Peniel E. Joseph’s book “The Third Reconstruction: America’s Struggle for Racial Justice in the Twenty-First Century” lies the conflict between what he calls “reconstructionists” and “redemptionists.”

Reconstructionists are described as champions of Black citizenship and Black dignity, while redemptionists “paper over racial, class, and gender hierarchies through an allegiance to white supremacy” in pursuit of a so-called colorblind society.

Joseph ties recent events, such as the Jan. 6 attack on the U.S. Capitol by supporters of former President Donald Trump, to the anti-democratic violence that stopped the post-Civil War Reconstruction in its tracks. He points out that anti-Black rhetoric and violence allowed the “denigration of Black humanity.”

“The Third Reconstruction” is as much commentary as it is based in fact. It’s a masterpiece that not only captures the last 150 years, but also paints a picture of what the future might look like.

Joseph writes, “I hope this book allows readers to take a historical journey that enables them to see America and its people through new eyes, and in so doing to understand and to retell a different story about the past, one that speaks to the present with enough grace to transform the nation’s future.”

Tracing the cycles of Black empowerment, white backlash

Conversations about the period of Reconstruction after the American Civil War are reminders of a familiar saying: “perception is reality.” Whether the discussion is about lost causes or liberation, interpretations of the period can be as divisive as the era itself.

Peniel E. Joseph’s latest book, “The Third Reconstruction: America’s Struggle for Racial Justice in the Twenty-First Century,” is as much commentary as it is based in fact. It’s a masterpiece that not only captures the last 150 years, but also paints a picture of what the future might look like.

Appreciating “The Third Reconstruction” requires some understanding of the first. For formerly enslaved people and their allies, the Emancipation Proclamation of 1863 and the Confederacy’s defeat in 1865 ushered in the hope that the United States could fulfill its moral promise of democracy, freedom, and equality. For a brief three decades after the war, about 2,000 Black men in the former Confederate states held public office.

The white backlash against Black empowerment was rapid and ferocious. Lynchings deprived Black people of their lives, while Jim Crow laws prevented them from exercising newly won freedom. And for the next century, white historians erased evidence of Black agency and resistance, and ignored the service of 179,000 Black soldiers in the Union Army. They portrayed Reconstruction, with its insistence on Black citizenship, as a debacle – a view that has been taught to generations of students.

Ultimately, Joseph’s book describes three distinct “reconstruction” periods. These were spans in which Americans seemed ready to grapple with the nation’s history of anti-Black racism and to take the first steps toward building a new, more inclusive society. The first reconstruction followed the bloody Civil War and lasted from about 1865-98; the second encompassed the Civil Rights era from 1954-68; and the third began with the election of Barack Obama in 2008 and continued through the rise of the Black Lives Matter movement.

Debt to W.E.B. Du Bois

In 1935, sociologist and historian W.E.B. Du Bois published “Black Reconstruction in America: 1860–1880,” in part as a corrective to the prevailing narrative put forward by white historians. As Joseph writes in “The Third Reconstruction,” “Du Bois viewed Reconstruction as more than just a missed opportunity, interpreting the post-Civil War decades as the nation’s second founding.”

Joseph, a professor of history at the University of Texas at Austin, uses Du Bois’ book as a point of reference as he outlines the struggle for racial justice. What makes Joseph’s book distinctive is a Du Bois trait – pointing out evidence of “duality” in the ongoing national story, in which “America remains a nation riven by cruel juxtapositions between slavery and freedom, wealth and inequality, beauty and violence.”

Duality is reflected in what Du Bois and other Black sociologists called “double consciousness,” the mindset of Black people who had been subjugated by white supremacy. At the same time that they resented racism, Black people also measured themselves in some ways by the standards of a discriminatory society.

At the heart of Joseph’s book lies the conflict between what he calls “reconstructionists” and “redemptionists.” Reconstructionists are described as champions of Black citizenship and Black dignity, while redemptionists “paper over racial, class, and gender hierarchies through an allegiance to white supremacy” in pursuit of a so-called “colorblind” society.

Joseph ties recent events, such as the Jan. 6 attack on the U.S. Capitol by supporters of former President Donald Trump, to the anti-democratic violence that stopped the first Reconstruction in its tracks. He points out that anti-Black rhetoric and violence allowed the “denigration of Black humanity.”

Joseph also uses sections of the book to explore concepts such as citizenship, dignity, backlash, leadership, and freedom. A commentary on citizenship both celebrates and criticizes Obama’s legacy. The author, who organized for the Obama campaign, calls the former president to account for “his refusal to confront the deeper history behind present-day political and racial divisions.”

Striving toward MLK’s “Beloved Community”

Malcolm X famously declared “I don’t see any American dream; I see an American nightmare.” Joseph inverts those words for the title of his introduction, “A Nightmare Is Still a Dream,” to ensure that hope accompanies America’s harsh history. He writes: “I hope this book allows readers to take a historical journey that enables them to see America and its people through new eyes, and in so doing to understand and to retell a different story about the past, one that speaks to the present with enough grace to transform the nation’s future.”

Joseph honors his mother, his Haitian American roots, and his education in a way that powerfully notes the Black experience – one that is both hopeful and harrowing. He celebrates the leadership of Black women, from Ida B. Wells and Fannie Lou Hamer to Nikole Hannah-Jones and Stacey Abrams.

The third reconstruction is still a work in progress, Joseph writes. The country and world that we craft moving forward, Joseph explains, can share the vision of Rev. Martin Luther King Jr’s “Beloved Community.”

“I believe that the struggle for Black dignity and citizenship can be achieved in our lifetime. But it must continue even if it takes several lifetimes,” Joseph writes. “Americans of all backgrounds can choose love over fear, community building over anxiety, equity over racial privilege, and dignity over shame and punishment.”

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

What Iran protesters really want

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

Mass protests in Iran have started to shift their focus from public anger over strict rules on female dress – rules that resulted in the Sept. 16 death of a woman in police custody. Instead, many protesters now hold up signs challenging a theology that justifies the regime’s enforcement of such social rules, namely that one man, known as the supreme leader, has a divine mandate to control Iranian society.

“Mullah’s Days Are Over,” reads one protest sign. Another states, “Down with the Velayat-e Faqih regime,” referring to a peculiar doctrine of the late Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini that Islam requires a religious scholar to rule the nation.

Iranians have many grievances, from high inflation to bans on certain women’s attire, but they seem increasingly united in seeking a democratic alternative to Iran’s theocracy. A poll last February showed 72% of Iranians oppose the head of state being a religious authority.

In neighboring Iraq, respected Shiite clerics play a quiet role, influencing society at a spiritual level rather than dictating moral behavior. They also back democracy. With that model next door, more Iranians can easily challenge their own clerics’ claims to divine rule.

What Iran protesters really want

Mass protests in Iran over the past 10 days have started to shift their focus from public anger over strict rules on female dress – rules that resulted in the Sept. 16 death of a woman in police custody. Instead, many protesters now hold up signs challenging a theology that justifies the regime’s enforcement of such social rules, namely that one man, known as the supreme leader, has a divine mandate to control Iranian society.

“Mullah’s Days Are Over,” reads one protest sign. Another states, “Down with the Velayat-e Faqih regime,” referring to a peculiar doctrine of the late Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini that Islam requires a “guardian jurist,” or a religious scholar, to rule the nation.

Iranians have many grievances, from high inflation to bans on certain women’s attire, but they seem increasingly united in seeking a democratic alternative to Iran’s theocracy. A poll last February by a Netherlands-based research foundation showed 72% of Iranians oppose the head of state being a Shiite religious authority. More than half prefer some sort of secular rule, such as a democratic republic or constitutional monarchy.

Direct criticism of the regime’s governing pillar comes at a sensitive time. Supreme leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, who was born in 1939, appears to be maneuvering to assure his successor. Possibilities range from his son, Mojtaba Khamenei, to the current president, Ebrahim Raisi, whose win in an election last year was arranged by the supreme leader. If the public now sees no legitimacy for clerical rule, a new leader – and the regime itself – might not survive.

“Never has the system been so much in question,” wrote Tara Kangarlou, author of “The Heartbeat of Iran,” in a column published in several European newspapers. Even in Iran’s centers for Islamic study, such as the city of Qom, some scholars have questioned the Velayat-e Faqih doctrine. In 2019, one regime official, Ahmad Vaez, said, “The separation of religion from politics, or indifference [of the clergy] to social and political issues ... is a danger.”

As the protests continue, the role of clerics in Iran is now front and center. In neighboring Iraq, the most respected Shiite clerics play a quiet role, influencing society at a spiritual level rather than dictating moral behavior. They also back democracy. With that model next door, more Iranians can easily challenge their own clerics’ claims to divine rule.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Are our happiness goals ambitious enough?

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 4 Min. )

-

By Tony Lobl

When our quest for happiness starts from a selfless, spiritual basis, we – and others – are inevitably blessed.

Are our happiness goals ambitious enough?

Whether clutching contentment or ruing a lack of it, it’s helpful to know that there’s a higher, more secure happiness available. The human quest for happiness often remains on the level of seeking experiences or possessions that may or may not be attained, and if attained, are vulnerable to changing conditions.

Many of these things are wholesome and legitimate aspirations, such as home, companionship, and career. But above and beyond these, and able to help form the shape they take in our experience, is a more spiritual happiness that we can both aspire to and attain. It’s one that’s inherent in a timeless truth we can grasp and demonstrate: God is real and good, and our life is actually spiritual, drawn solely from this divine source of all goodness.

Here’s a description of this God-sourced happiness from “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures” by the discoverer of Christian Science, Mary Baker Eddy: “Happiness is spiritual, born of Truth and Love” (p. 57) – that is, born of God, divine Spirit, since, as the Bible says, God is Truth and Love.

This defines our nature, since we are each the spiritual expression of God. So, we include qualities born of Truth, such as honesty and integrity, and of Love, such as compassion and forgiveness. If such qualities are key to our happiness, this indicates that a higher happiness is one that reaches beyond a personal sense of well-being to a genuine desire to benefit others.

The sentence from Science and Health following the earlier description affirms this selfless nature of true happiness and highlights its scope: “It is unselfish; therefore it cannot exist alone, but requires all mankind to share it.” Now that’s ambitious!

What kind of happiness is it that we share with all humanity?

It’s found in the divine goodness that already belongs to all humanity, as revealed by Christ – the spiritual idea of all that Spirit, God, is and does. When we are mired in everyday problems or face deep challenges, this spiritual awareness might feel like a distant aspiration, even a false promise. But at every moment it is our God-reflecting mentality.

By contrast, the pleasures and pains of material sense, unaware of Spirit, lack truth. No matter how convincing a material sensation feels, it’s drawn from a source that is itself unreal, as Science and Health explains: “That matter is substantial or has life and sensation, is one of the false beliefs of mortals, and exists only in a supposititious mortal consciousness” (p. 278).

The master demonstrator of our true Christliness, Christ Jesus, showed that no matter how vivid the evidence of material ills or the lure of sensuality appears to be, no matter how long such evidence has endured, it must yield to a clear understanding that Life is Spirit, God. Jesus proved that there’s an infinite distance between material sensation and our spiritual identity as God’s expression. In healings such as the restored health of a man bedridden for decades and the spiritual transformation of a woman who had long lived an immoral life, he demonstrated that enduring health and joy constitute our very substance.

From the perspective of the “supposititious mortal consciousness,” such qualities are temporary, at the mercy of matter’s conditions. In the Christly view of our spiritual identity, however, they are established forever in our oneness with infinite Spirit.

While this seems to present to human consciousness two conflicting perspectives, Christ, the true idea of God, lifts us above the false concept – life in matter – to see divine Life as our sole existence. Then the lie of competing views dissolves into the truth that there is but one view: the spiritual. When healing results from this shift in thought, the happiness that ensues is neither transient nor selfish. It’s of lasting and all-blessing benefit as a breakthrough proof that God is the only true Life of all.

In this divine Life, we have happiness that’s forever pure and secure and requires no ambition to attain it. It’s a quality we forever include and exude as God’s reflection. So, in seeking happiness, we’re never truly looking to gain a personal blessing, but rather to prove a goodness that’s ours because it’s everyone’s.

So here’s to our goals always being spiritually ambitious, and to being ambitious enough to seek not only our happiness but the happiness that is universal and eternal – to understand and demonstrate the happiness that belongs to all, on behalf of all.

Adapted from an editorial published in the Sept. 26, 2022, issue of the Christian Science Sentinel.

A message of love

Mourning in Russia

A look ahead

Come back tomorrow, when we’ll have a story about how Minneapolis is trying to address a problem many cities are facing: a housing shortage.