- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 8 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- Ukraine: In bid to create ‘Russian World,’ education was weaponized

- Remaking the draft: Northern Europe infuses conscription with values

- ‘Do something small’: One journalist sees solutions for world’s oceans

- New views: What makes a top US college, and the significance of Timbuktu

- Keepsakes and memories: Finding, in the clutter, a life well lived

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Ford accelerates toward an electric vehicle future

The future of the automobile is electric.

If there was any doubt about that statement, the Ford Motor Company is forcing the issue. Ford CEO Jim Farley recently issued an ultimatum to his U.S. dealerships: You’re in or you’re out.

Ford dealers have until Oct. 31 to commit to selling the company’s line of electric vehicles (EVs) or they won’t get any Ford EVs to sell.

And there’s more. A Ford dealer’s commitment to sell EVs includes a certification process that, among other things, requires installation of fast charging stations (at an estimated cost of $100,000-$200,000).

Ford only has three EV models now: the F-150 Lightning, Mustang Mach-E, and e-Transit commercial van. But the company plans to spend $50 billion to expand its line and has a goal to sell 2 million EVs a year by 2026 (or about half their total sales last year).

Ford will also require dealers to post prices and sell its EVs online. “We’ve been studying Tesla closely,” Ford’s CEO told reporters last month. Tesla boldly launched without a dealer network, selling vehicles exclusively online. So far this year, Tesla reports selling more than 908,000 electric vehicles. But Tesla’s sales approach in Norway (where 86% of all new cars sold in August were plug-ins) is evolving. In Norway, Tesla has “dealer-like facilities and we think that’s the direction they’ll go as they scale their operations in the United States,” said Mr. Farley.

In other words, Tesla is becoming more like Ford – and vice versa. The EV revolution is accelerating.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

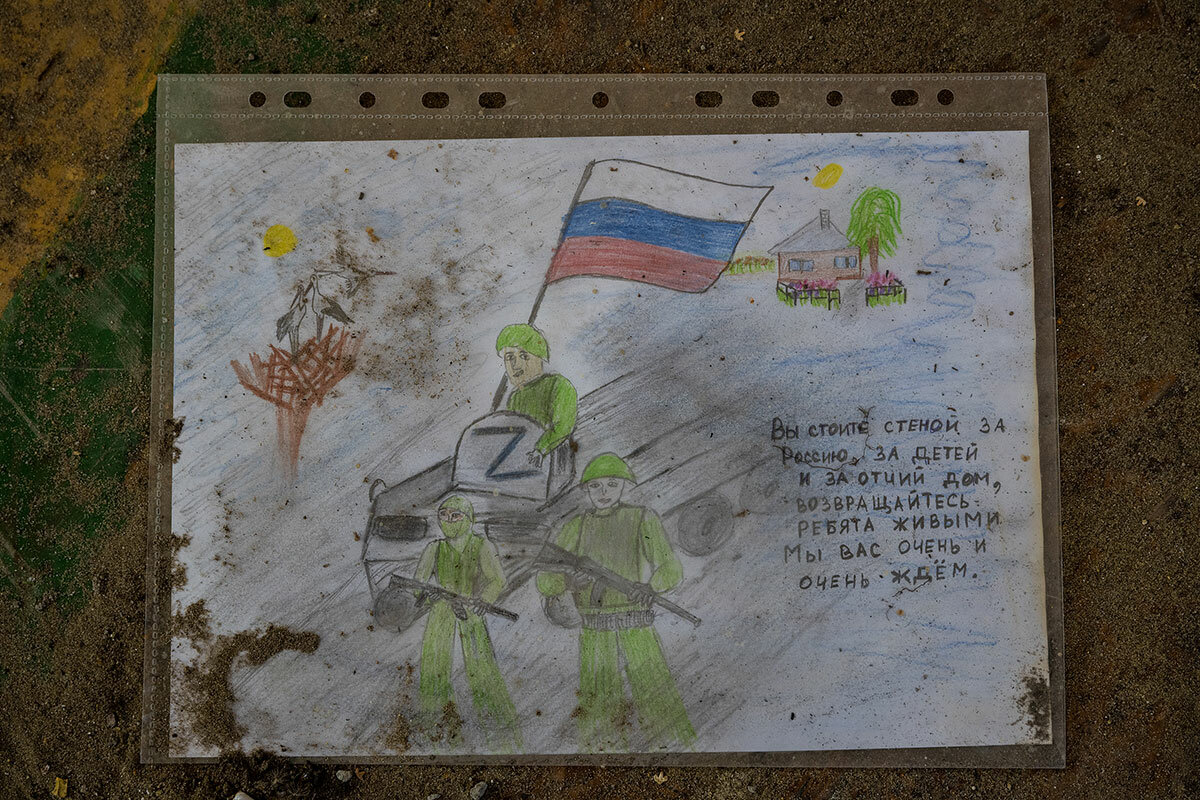

Ukraine: In bid to create ‘Russian World,’ education was weaponized

The Russian occupation of Ukraine includes a hearts-and-minds campaign in schools. Our reporter looks at one Ukraine community where distrust of Russian propaganda ran high, but found some takers.

Ukrainians widely scoff at Moscow’s “Russian World” project, and often use the term derisively when describing the wholesale destruction wrought by Russia’s invasion of their country. Still education – and the teachers that shape the next generation of citizens – remains key to the fight for both sides.

Russian propaganda newspapers handed out across the Kharkiv region, for example, highlight the “crucial step” of gaining accreditation for schools to raise them to a “Russian standard.” Ukraine has classified teachers who work with the Russians as “collaborators” who face prosecution.

Russia’s forced retreat from thousands of square miles of northeastern Ukraine is now revealing the scale of Moscow’s aims, as well as the haphazard efforts to create an idealized Russian World that were frequently undermined by the brutal realities of the occupation.

“Schools are the most important thing, the top priority of this brain war,” says Hennadii Kovzunovich, when asked why the Kyiv-based emergency services unit he commands was sent to Izium with the primary task of clearing rubble from destroyed schools.

“The Russians are trying to come to schools to produce this [pro-Russia] patriotism from the earliest age,” he says. “They are trying to brainwash kids, so it is important to re-start schools as soon as possible.”

Ukraine: In bid to create ‘Russian World,’ education was weaponized

Ukrainian emergency workers were surprised when they first entered the white-painted school in Izium, after a Ukrainian counteroffensive swept away Russian troops.

From the outside, Lyceum No. 6 appears unscathed by more than six months of Russian occupation, and ready to welcome students for the new academic year.

In fact, Russian authorities intended to showcase it as a model for teaching a new Russian curriculum, centerpiece of a hearts-and-minds effort based on shared affinity for the Russian language and culture that Moscow affectionately calls “Russkiy Mir,” or Russian World.

But inside, something was missing – and not just the Ukrainian textbooks, which had been carted away to help pave the way for what Russia claimed would become a transformed Ukrainian society.

“The Russians came to this school and took all the cutlery and knives, and left the cheap, plastic ones,” says Hennadii Kovzunovich, the heavyset commander of a Ukrainian emergency services unit temporarily based at the school.

“Dishes? Really?” he asks with a tone of incredulity.

Ukrainians widely scoff at the Russian World project, and often use the term derisively when describing the wholesale destruction wrought by Russia’s invasion of their country – destruction that is increasingly evident as a Ukrainian counteroffensive recaptures swaths of occupied territory.

Still, education – and the teachers who shape the next generation of citizens – remain key to the fight for both sides.

Russian propaganda newspapers handed out across the Kharkiv region, for example, highlight the “crucial step” of gaining official Russian accreditation for schools in “liberated” areas, to raise them to a “Russian standard.”

The Ukrainian government has even classified teachers who work with the Russians as “collaborators.” On the eve of the school year, a top Ukrainian education official warned that such actions “fall under the Criminal Code of Ukraine” and would be prosecuted.

Schools as “top priority”

The forced Russian retreat from thousands of square miles of northeast Ukraine after half a year is now revealing the scale of Russian aims, as well as the haphazard and often ham-fisted efforts to create an idealized Russian World that were frequently undermined by the brutal realities of Russia’s own occupation.

“Schools are the most important thing, the top priority of this brain war,” says Mr. Kovzunovich, when asked why his emergency services unit, based in Kyiv, was sent to Izium with the primary task of clearing rubble from destroyed schools. In cities across the region, Russians set up military bases in school compounds, which were then further damaged when targeted by Ukraine in its lightning counteroffensive.

“The Russians are trying to come to schools to produce this [pro-Russia] patriotism from the earliest age,” says Mr. Kovzunovich. “They are trying to brainwash kids, so it is important to restart schools as soon as possible.”

Izium first responders who stayed behind to help local populations after the invasion recount what they say were unnecessary threats from Russian commanders to force their cooperation. Indeed, apart from the education efforts – and limited humanitarian aid, which locals say in the first deliveries appeared to actually be stolen Ukrainian goods – almost nothing appeared to be done by the Russians to win Ukrainian hearts and minds over to Russian World.

“I studied in Moscow. I know the Russians well, but I don’t recognize them now; they have been zombified by [President Vladimir] Putin,” Mr. Kovzunovich says.

As he speaks, as if on cue, an explosion sounds outside – a leftover Russian mine with a self-destruction mechanism detonating itself. Five cluster bomblets were left outside the back of the school, too, which had to be dispatched with a shotgun.

“Against my ideology”

The looted cutlery and dangerous detritus left by the Russians are no surprise to Natalia Filonova, a teacher of Ukrainian and world history at Lyceum No. 6, who is also head specialist for the Ministry of Education in Izium.

Before the war, some 600 teachers taught in Izium’s 11 schools, says Ms. Filonova, a veteran teacher of 26 years, who says she refused to work in the Russian system because it was “against my ideology.”

These days, her busy department office is a constant flow of students and parents, often emotional, asking about issuing diplomas, and even replacing documents burned in the war. An upstairs room is full of random boxes of supplies sent from Russia and meant for classrooms: no textbooks, but piles of Russian-language toys and games, and pens and coloring books.

With the prevailing expectation that Russian occupation would be permanent, roughly 20% of teachers accepted Russian offers of new curriculum training in Russian cities, Ms. Filonova says.

The Russians “wanted to show they could start a normal life,” she notes.

“In reality, it was impossible for them to start the school year. How can you group children together when there is shelling? You must stop the war,” she says. “It is impossible to imagine teaching students when it is so dangerous outside.”

Such a challenge was on top of the lack of electricity, water, mobile phone signals, or even natural gas for heat – never mind the obligatory Russian curriculum.

“All teachers – me as well – wanted to start working and to teach. But as soon as I saw the new program, I don’t know how these people could agree” to collaborate, says Ms. Filonova. “For a doctor or emergency services, it is one thing. But for a teacher, it is very important what you are teaching to children.”

Those who stayed, those who left

Indeed, the majority of teachers left or stayed home, rather than serve as a tool for a Russian World, says Leonid Naumenko, a lawyer for the education department. Like Ms. Filonova, he was asked to work by a colleague, and said no.

“Russian World has gone the way of the Russian warship,” says Mr. Naumenko, referring to an episode early in the war when Ukrainian soldiers on a small Black Sea island rejected, in colorful language, an order to surrender from a Russian warship.

Teachers who traveled to Russia for training have not shown up to teach now. “Information spreads fast, so they probably know that no one will work with them here,” he says. “How will they look into their students’ eyes?”

In Izium, teachers say there was little pushback by Russian occupiers against those who refused to cooperate. But elsewhere, the penalty could be severe.

Head teacher Lidiya Tina, an educator with 40 years’ experience from another Kharkiv village, reportedly was detained for 19 days for refusing to set up a Russian school.

“A car pulled up and three masked men with assault rifles got out,” Ms. Tina told the BBC last week. “They put a gun to my throat and ripped up my teaching diploma in front of my face.”

One teacher in Balakliia, 25 miles northwest of Izium, was ordered to destroy thousands of Ukrainian textbooks but managed to hide them instead, the BBC reported.

Refusing to teach was not just a question of collaboration, but also of content, says a Russian-language teacher in Balakliia who only gave her first name, Marina.

“I realized that to cooperate, I would definitely have to tell kids that Ukraine doesn’t exist, that the Ukrainian language is small and nothing compared to the Russian language,” Marina told the Monitor.

“The majority of teachers evacuated from here because they did not want to cooperate with Russians,” says Marina. Of those who stayed, she says, “I know two were very pro-Russian before the aggression. Of course, they were willing to teach. And a third decided it was better to work, to not suffer hunger.”

A school director’s choice

That was a tough calculation for many teachers, including apparently Lubov Gozha, director of Comprehensive School No. 11 in Izium. Hers was one of just two out of 92 schools in the region that received an official Russian certificate of accreditation, according to the occupation newspaper Kharkiv Z.

Amid advertisements for patriotic summer camp in Russia, and offers of free university tuition, Kharkiv Z reported that the Russian Education Ministry promised to take “under our wings” and equip with “appropriate infrastructure” all schools, to teach a “normal program” to children.

Today, Comprehensive School No. 11 is still intact. The only obvious sign of the former Russian military presence – aside from copies of the Red Star newspaper read by Russian soldiers, and discarded ration packs – was two anti-tank mines thrown into the outdoor toilet.

“I’m not surprised they collaborated,” says Ukrainian soldier Anton, noting that his unit found a photograph from 2009 that showed students posing in Soviet-style “Pioneer Youth” neckerchiefs.

“I lived in the Soviet Union and was a Pioneer,” says another soldier, Volodymyr. “When I saw that, I had a flashback.”

Neighbors of the school chatting on the street grow tearful when asked about the director, Ms. Gozha, who was depicted in Kharkiv Z handing out diplomas at a mid-August ceremony in Izium. Ukrainian authorities had asked about her also, they say.

“Hey, we all thought that [the Russian presence] is going to be forever,” says a young man called Sasha. “What should she do? We thought the Russians would be here for decades.”

Fellow teachers say Ms. Gozha has been arrested. Those who know her say she was a professional and experienced school administrator who spoke mostly Ukrainian.

“She was definitely not pro-Russian,” says Ms. Filonova, the education ministry specialist, who knew Ms. Gozha. “The Russians succeeded in convincing her, so she agreed to this accreditation. I think after she started this process, she couldn’t step back.”

Igor Ishchuk supported reporting for this article.

Remaking the draft: Northern Europe infuses conscription with values

With Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Nordic and Baltic states are taking military service, including conscription, more seriously. Our reporter looks at how Finland and Estonia have made that service a cultural norm with a generation that cherishes gender equality and personal freedom.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

The military draft has largely fallen out of favor in Western democracies. But due to their geography and history, the Baltic and Nordic countries have more keenly felt threats to their national security. Some never did away with conscription, while others paused the draft only to bring it back following the jolt of Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014.

Now, with the war in Ukraine, many are renewing calls for required military service, with an eye toward modernizing a much-criticized institution whose very tenet – forced service – seemingly conflicts with social progress and individual freedoms.

“Conscription is not simply a tool for staffing military organizations,” says postdoctoral researcher Sanna Strand. “It’s embedded in broader society and societal transformation.

“When an institution that was so broadly criticized as economically inefficient but also basically unjust is supposed to come back again for reasons of a worsening security situation, it’s not enough to simply say ‘Okay, we need it.’ We also need to explain how this actually makes sense in today’s society, and how it could be seen as in line with gender equality politics or neoliberal public governance.”

Remaking the draft: Northern Europe infuses conscription with values

Algirts Vilkoitis has gone “into the forest” many times over the last decade.

With the trees of the Riga forest stretching skyward around him, Mr. Vilkoitis, a second-class lieutenant with Latvia’s National Guard, runs time trials, hefting 45-pound sandbags onto a wall and then throwing them down. He then grips a sandbag while sprinting down a long, wooded trail, as fellow guard members wait their turn. Later they’ll don full military gear, including guns and helmets, to practice mile-long runs.

The experience of “going into the forest” – slang for military training – has intensified in the wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Latvia is a former Soviet Republic that shares a 130-mile border with Russia. Its government is joining a chorus of Nordic and Baltic states that have reintroduced or are beefing up the draft in the name of an age-old national security argument, but with a modern twist: a focus on individual development and personal growth.

On the personal benefits of “going into the forest,” Mr. Vilkoitis is a walking advertisement. He’s now trained in everything from first aid and compass navigation to managing weapons systems and working alongside colleagues in both urban and forested environments. It’s tactical training that’s not only useful in wartime, but also in civilian life.

“You have a clear vision of what you’re going to do in any crisis situation,” says Mr. Vilkoitis, a former roofer turned furniture entrepreneur who joined the National Guard nearly 10 years ago. He’s also fitter than ever, both mentally and physically. “I’ve also become part of a big family, and we see each other in civilian life also. This communal feeling is really, really powerful.”

The military draft has largely fallen out of favor in Western democracies, with America’s military becoming all-volunteer in 1973, France’s in 1996, and Germany’s in 2011. But due to their geography and history, the Baltic and Nordic countries have more keenly felt threats to their national security. Some never did away with conscription, while others paused the draft only to bring it back following the jolt of Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014. Now, with the war in Ukraine, many are renewing calls for required military service, with an eye toward modernizing a much-criticized institution whose very tenet – forced service – seemingly conflicts with social progress and individual freedoms.

“Conscription is not simply a tool for staffing military organizations – it’s embedded in broader society and societal transformation,” says Sanna Strand, a postdoctoral researcher at the Austrian Institute for International Affairs. “When an institution that was so broadly criticized as economically inefficient but also basically unjust is supposed to come back again for reasons of a worsening security situation, it’s not enough to simply say, ‘Okay, we need it.’ We also need to explain how this actually makes sense in today’s society, and how it could be seen as in line with gender equality politics or neoliberal public governance.”

No more “glorious soldiers”

Two hundred years ago, European conscription policies were crafted around the idea of grooming young men into patriotic and productive citizens for the good of the national collective. In modern times, these nationalistic arguments have lost favor, especially after the Cold War ended.

Gender equality and personal freedoms – sometimes over the collective good – are an indelible part of democratic governance today. Also changed is modern warfare, which is more technologically advanced and requires more engineering know-how.

“War is far, far away from the romantic wars of the 19th century,” says Deniss Hanovs, a cultural history professor at Riga Stradiņš University who opposes conscription and believes that a well-trained professional army is the better option. “Young males today are in a prolonged teenage period. They’re not ready for army at 18. To conscript a young male into a massive army and create a ‘glorious soldier,’ it’s a thing of the past.”

In short, should a national military need more soldiers, a World War I era approach won’t work.

Modern conscription in the seven Baltic and Nordic states near the Baltic Sea is (or will be, when Latvia implements its draft next year) essentially a rotating call to service of a few hundred to tens of thousands of young people each year. For anywhere from a few months to a year, the conscripted men, and sometimes women, will receive pay to undergo basic and specialized training. After the mandatory service period, they’ll enter reserves with the understanding that they’ll come back for refresher training, or report for wartime service if ever needed.

NATO, Government agencies

Generally, they return to civilian life, though some might apply to join the full-time military. Over time, as Ukraine has now seen after bringing back the draft in 2014 following a brief hiatus, the result can be a body of well-trained military professionals and reservists ready at a moment’s notice.

When Sweden brought back the draft in 2017, leaders felt compelled to reiterate it would be a modernized and re-imagined institution. Not only would women be included, mirroring Norway’s gender-neutral lead a few years earlier, but Swedish conscription would also be selective and competitive. In this way, it would have the appearance of calling only on those who “demonstrated willingness,” says Dr. Strand.

“It was a ‘We will try to listen to you as much as possible’ message, in contrast to the 1900s, when notions of having duties, being obedient, and submitting to the state [were] more idealized and less controversial,” says Dr. Strand.

Finland, which like Sweden only acceded to NATO this year, trains 27,000 conscripts each year. Its messaging includes promises to reduce health risks, minimize environmental impacts, and also be “motivating.” In a model that’s studied by other governments, Finland offers a menu of service options, including basic training for about half a year, or more specialized service in, say, health care, education, or environmental protection for a year.

Finnish conscription is widely regarded as a success, with three-quarters of the public supporting the draft and 900,000 trained reservists at the ready. The Finns have also made service a social expectation, and it’s considered shameful not to report. (About 80% do.)

The Estonian government, whose model is also studied as a success, will call up greater numbers of conscripts in coming years. “I know many Estonians and they tell me, ‘Sorry, I can’t make this meeting because I have to go into the forest,’” says Māris Andžāns, director of the Center for Geopolitical Studies Riga. “Devoting a year to defense of the state is basically a way of life, part of the social contract.”

Indeed, the Baltic and Nordic governments are riding a wave of public support for mandatory military service.

“Solidarity is back. Promotion of military service and reminding people about the quality of life, about values is back,” says Zdzislaw Sliwa, a retired colonel and dean of the Baltic Defense College. “What is uniting us is values, democracy, respect for human rights, respect for people’s lives, respect for government and institutions,” he says.

To be a hedgehog

Yet, governments must be careful not to squander public goodwill, as the war in Ukraine grinds into its eighth month.

After all, it’s tempting to revert to old models in times of need. Latvian Defense Minister Artis Pabriks says he most fears the “black-day scenario” of Russia invading Latvia with zero warning. Russian President Vladimir Putin’s armies took months to amass on the Ukrainian border, but they could enter tiny Latvia with far less preparation.

“If someone invades us, we understand they might overwhelm us with might,” says Mr. Pabriks, who is overseeing Latvia’s conscription plan, which will eventually double the country’s ranks to about 50,000 professionals and reservists. “We want to be like a small hedgehog, with many needles. So if you touch us, you will bleed a lot as well.”

Mr. Pabriks’ approach has plenty of critics, such as Dr. Hanovs, who charges that he’s hopped “onto a time machine back into the 19th century.” Yet Latvia’s foreign minister has publicly trumpeted that motivation is important, as is a meaningful personal experience.

Indeed, individual rights must be protected as conscription goes forward, say experts. The Soviet army, which utilized a brutal form of hazing called dedovshchina, is a not-too-distant memory for the Baltic States.

Bullying, degrading treatment, and discrimination against various groups are also too prevalent in military culture, notes Grazvydas Jasutis, a post-Soviet security expert at the Geneva Graduate Institute.

“Political leaders must pay significant attention to this. Violations of the rights of members of the military can undermine national security,” says Dr. Jasutis.

In Norway, nearly a third of women report experiencing sexual harassment. The numbers bear out the impact of unsafe working environments; although a third of conscripts are women, they make up less than 20% of full-time military employees. In other words, they fall out of the pipeline.

Yet, conscription done right, says Dr. Jasutis, presents a golden opportunity to strengthen the bridge between state and society. “This makes the states stronger, not only physically but also ideologically.”

Indeed, in countries such as Latvia, where researchers have long documented societal divides between the Russian-speaking minority and Latvian-speaking majority, training side by side can bring together disparate ethnic groups.

Service, says Otto Tabuns, director of the Baltic Security Foundation, is a way for them to “coexist peacefully, to work together for a common goal.”

NATO, Government agencies

Q&A

‘Do something small’: One journalist sees solutions for world’s oceans

The scale of the problems in the world’s oceans is daunting. But a Q&A with journalist Ian Urbina leaves readers with a path to individual agency and hope.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

When it comes to the array of challenges facing the world’s oceans, journalist Ian Urbina says, “I’m going to double down on this.” One way he’s doing that is with a new podcast, produced by his Outlaw Ocean Project with the Los Angeles Times and CBC Podcasts.

In an interview with the Monitor, Mr. Urbina describes why oceans need humanity’s attention. Often out of sight and out of mind, oceans have big effects on the global environment, food systems, and human rights for legions of maritime workers.

“The high seas belong to everyone and no one, and therefore jurisdictionally it’s an unusually complicated, murky space,” he says. “We’re starting to realize, oh, just because it’s big doesn’t mean it’s utterly durable.”

He says media attention is rising, on issues from overfishing and pollution to human rights abuses on commercial boats. Actions by the media, researchers, advocates, and consumers can create momentum for positive change, Mr. Urbina says.

“Don’t get demoralized,” he says. It might be as simple as making a small donation or researching what shrimp to buy. “If you just ... try to do something small on your chosen thing, it can make a difference.”

‘Do something small’: One journalist sees solutions for world’s oceans

Ian Urbina is what you might call a globe-trotting journalist, except he focuses his reporting on the oceans, not the land.

Earlier this year he was honored for his investigative writing by the Society of Professional Journalists, for stories tied to the treatment of migrants in Libya (and off its Mediterranean coast) and disruption in Gambia’s fisheries, published during 2021 in The New Yorker and The Atlantic. Another story from his Libya reporting – about Europe’s treatment of African migrants – ran here in the Monitor.

Now Mr. Urbina’s Outlaw Ocean Project is launching a podcast series based on his work, in partnership with the Los Angeles Times and CBC Podcasts.

In an interview with the Monitor’s Mark Trumbull, he discussed the issues that make oceans important and why, in his words, “I’m going to double down on this.” He also points to paths toward solutions – and hope. The comments have been edited for length.

You explore what you call the “outlaw ocean.” Why are oceans so different from land – and so difficult to police?

From the perspective of governance, you have this situation where the high seas belong to everyone and no one, and therefore jurisdictionally it’s an unusually complicated, murky space. ... The second issue is geography. The reality of the high seas is it’s so incredibly sprawling, two-thirds of the planet. ...

And then when it comes specifically to the category of abuses of crimes that pertain to people – murder on camera and slavery and abuse of stowaways and wage theft and abandonment of crew, you know, all these human rights and labor abuses – a contributing factor to that subcategory of crimes is who’s getting harmed. Most often the victims of those sorts of crimes are poor, are folks from developing nations. ... A lot of them are not literate. A lot of them have signed contracts in languages they don’t even speak. ...

And the boss of the [floating workplace] is from one country. The flag of the factory is to another. The guys working in there, getting abused, are from a third. The catch is being all loaded on a fourth. It becomes just insane.

Many of us might feel like, well, my connection with the ocean is when I buy some fish for dinner. But is it much more than that?

I mean, if you think of the planet Earth as a living organism, maybe metaphorically. It has inherent systems. It’s got lungs. The lungs of the planet – 50% of the air we breathe – are cleaned by the oceans. So the lungs of the planet are at stake. If you think of it as the commercial circulatory system, 80% of our [global] commerce gets to us cheaply and efficiently ... by ship. So not just fish, but iPhones and, you know, tennis shoes and grain and oil. ... The oceans are also a temperature stabilizer of our body, you know, of the body planet. ... They take off a lot of the heat. ...

There is this misconception that it’s ever regenerating. It’s so big, “dilution is the solution to pollution” was the mantra throughout the ’70s and ’80s. ... We’re starting to realize, oh, just because it’s big doesn’t mean it’s utterly durable.

So you have a seven-part podcast with the goal of shedding light on these varied challenges that are so often out of sight, out of mind. As we talk about that, I hope to get more positive, but does the stress on the oceans amount to a disaster in the making?

Yes, it is a disaster. But that doesn’t mean we have the luxury of being demoralized. ... Do I think it’s unsolvable? No, I think there are lots of ways in which things can be done to mitigate the disaster and better govern. And a lot of people are doing lots of things in different places, in individual fights, in individual battles.

One episode features the nonprofit group Sea Shepherd chasing down a ship on Interpol’s wanted list for illegal fishing. Does that illustrate some hope for holding the illegal fishing operators to account? [This episode was released today as Part 2 of the weekly podcast.]

Sea Shepherd said ... we’re going to go after these guys and we’re going to find them wherever they are, and we’re going to chase them and harangue them and draw a lot of media attention on them and sort of show how broken the system is. ...

And they succeeded. You know, they found the Thunder, which was at that time ranked the top worst illegal fishing vessel on the planet, $67 million worth of illicit catch. And they found these guys – nets in the water – and proceeded to chase them for 110 days all across the planet. And all sorts of dramatic stuff happened in the interim. And ultimately the Thunder – spoiler alert here – sunk itself and all the crew were rescued [off the coast of West Africa]. But they scuttled the evidence of their true bigger crimes, were rescued by Sea Shepherd, handed over to law enforcement, and the officers were prosecuted and served time. So I think there are cases like that where you see various actors make savvy use of the media and the law to try to make a difference.

On the goal of more accountability, how have things been changing and where do we need to go?

I do think there’s ... more media coverage by lots of folks, a lot of good. There’s more wind in the sails of the advocates and the academics who were in the trenches already fighting this fight. Now they’ve got more media behind them. I think you also see more market side players having an awareness that, you know, this issue isn’t going away.

Whether it’s the issue of slavery and the use of captive labor as a cost-saving tactic on fishing vessels, or intentional dumping of oil as a cost-saving tactic, or illegal fishing – meaning going places you’re not supposed to or using gear you’re not supposed to – all these things are cost-saving tactics. And who benefits from that but the companies? And the companies writ large, you know, the ship-owning companies, the insurers, the fish sellers, wholesalers, grocery stores, restaurants, all these market players are the ones who turn a blind eye. ... The decentralization of the supply chain has allowed them to say, “Well, we don’t know what’s happening.” You know, “we outsource” ... and so they can’t be held accountable. Well, I think there’s a reckoning coming on that.

Is there some overarching human value or values that these ocean issues call for?

One can argue this from a utilitarian and highly pragmatic point of view, which is like your sheer existential self-interest. You need to care about these things. And let’s not put any ethical issues in the mix. Let’s just put survival and self-interest in the mix. And you can convincingly argue that you should really care about these things, even the slavery concerns, because that stuff comes back to haunt you.

Or – and I like to do the “and” – or you can argue this from a fundamental humanity, sort of a humanism point of view, which is to say, Hey, look, if I’m benefiting from something that I don’t agree with and I’m confronted by it, then I probably need to do something about that.

This reminds me, you’ve reported on fisheries in Gambia, and the role of Chinese companies on the coast there. Do you see hope for Gambia to regain more agency over its own resources?

I mean, the story of West Africa generally, more specifically Senegal, Mauritania, Gambia, and more specifically with regard to this weird thing called fishmeal, is like a textbook story. ... It’s two guys at a table discussing a contract, but they’re not on equal footing. ... And the beneficiaries of the stuff that China is extracting is you and me. You know, we’re the ones buying the stuff that China is exporting that’s getting fed by [fishmeal from Gambia]. ...

The government of Gambia has no ability to actually check whether the terms of the agreement are being complied with and a sustainable extraction is occurring or an unsustainable extraction is occurring. ... The factories that get built have very few actual Africans working in them. It’s mostly mechanized and it’s almost entirely for export. So the revenue doesn’t stay local and create other industry. ...

Aquaculture fish farming was created in the ’70s to try to slow ocean depletion. [Yet today] all this ground up bonga fish, 30 to 40% of all the biomass pulled out of the ocean, isn’t for human consumption; it’s for fishmeal. It’s to be ground up and to be fed to the high-priced shrimp, salmon, the tuna. ...

So now we’re catching wild caught fish in places like Gambia that historically was eaten by the locals and was free at the market, often, because it was so plentiful. Now the locals can’t touch the stuff because they’re priced out, because it’s all going to the factory to get ground up and exported. That’s the crazy economy we have.

What can the average person do in their own actions? What would you recommend?

First, I’d say, don’t get demoralized and don’t think that you should or can solve the war. Just think about battles, and choose which of the many battles interest you most, whether it’s sea slavery or plastic pollution or whaling or illegal fishing or murder and violence at sea or whatever. Just narrow it down, choose a bite-size thing, and then focus on that.

And then the second thing I would say is, think about yourself in a lot of different ways. Every average person has lots of hats. We are voters. We are taxpayers. We are donors. We are interlocutors; we have conversations with our kids and our partners. ... We’re buyers. ... If you think of yourself as, “I have six hats and in each of them I can do something small ... I’m going to do a little research and figure out what’s the better or worse shrimp to buy.” OK, that’s a little action as a consumer. ... If you just take it small and think of yourself in lots of different roles and try to do something small on your chosen thing, it can make a difference.

Points of Progress

New views: What makes a top US college, and the significance of Timbuktu

This week’s progress roundup includes paths to dignity, and educational and gender equity in the U.S., Mali, and India, as well as innovative ways to care for the planet.

New views: What makes a top US college, and the significance of Timbuktu

1. United States

A Texas university offers a model of affordability that is boosting economic mobility. The University of Texas Rio Grande Valley serves a student body that is 90% Hispanic and made up primarily of first-generation college students. Over 60% of students qualify for federal Pell Grants, awarded to those with high financial need. Additional funding is provided by the state, and UT Rio Grande Valley has its own program that helps cover cost gaps. The majority of students pay no tuition or fees; the average cost to attend was $917 in 2019-20, compared with $7,907 for UT Austin.

“There are a lot of institutions that aren’t featured in mainstream media that are serving students extremely well,” said Michael Itzkowitz, who wrote a recent Third Way report on higher education and economic mobility. The team studied 1,320 U.S. institutions using an index that combines factors like post-enrollment earnings, the average net price of attendance, and percentage of Pell Grant recipients.

UT Rio Grande Valley ranked among the top five schools offering economic mobility, alongside California State University, Los Angeles; California State University, Dominguez Hills; Texas A&M International University; and California State University, Bakersfield.

Source: Washington Monthly

2. Mali

Tens of thousands of precious manuscripts saved from Timbuktu are now available to all, offering a window into a rich history of African scholarship. The texts, which range from legal, spiritual, and scientific writings to travel diaries and correspondence, were smuggled out of the city when jihadis took over in 2012 and burned countless other manuscripts. Following an intensive process of preserving, categorizing, and digitizing, over 40,000 pages of the texts are now accessible to anyone via Google Arts & Culture.

The writings show that scholars from Timbuktu used mathematics before scientists on other continents and figured out that the Earth rotates around the sun in a similar time period as Galileo. “Africans knew how to write before many outside Africa did,” said Andogoly Guindo, Mali’s minister of culture. “These manuscripts can throw light on part of Africa’s past.” Few scholars have the language know-how, so only a fraction of the documents are being translated – for now.

Source: The New York Times

3. Germany

The world’s first recyclable wind turbine blades are spinning at a German wind farm. The blades of a wind turbine measure around 170 feet long and are generally designed to be replaced every 20 years. As wind energy expands, experts estimate that over 2 million tons of blade material will be decommissioned each year by 2050.

Siemens Gamesa’s recyclable blades were developed in Denmark and recently installed on turbines at a 342-megawatt wind farm in the German North Sea, off the coast of the island of Heligoland. The resin, fiberglass, wood, and other materials used to make the blades can be separated with a mild acid solution and reused for other products such as suitcases or flat-screen casings.

Sources: Electrek, Scientific American

4. India

India’s gender ratio has begun to normalize as sex selection falls. Families are less likely than before to use abortions to prevent the birth of daughters, according to new data from the country’s National Family Health Survey. The data shows a reduction in the sex ratio to 108 boys for every 100 girls, compared with the natural rate of 105 to 100. This follows a peak of 111 boys in 2011.

Sex selection became a problem in the 1980s, when prenatal gender testing became widespread and affordable. Government efforts such as a ban on prenatal sex tests and a “Save the Daughter, Educate the Daughter” (Beti Bachao Beto Padhao, or BBBP) advertising campaign begun in 2015 worked to curb a preference for boys, which is prompted by financial and cultural incentives for some families. The Ministry of Women and Child Development recently asked Parliament to shift away from ads and devote more BBBP funds to girls’ health and education.

Sources: Pew Research Center, The Indian Express

5. Australia

Coral cover has reached the highest level on record in two-thirds of the Great Barrier Reef. Hard coral cover, an indication of reef health, has grown from 27% to 36% in the northern region and from 26% to 33% in the central region since 2021, the highest levels since data was first recorded 36 years ago. Home to over 5,000 species, the reef has been hit hard by periodic widespread bleaching events since 1998. But growth shows that some recovery is possible following the most intense disturbances, notably the underwater heat waves in 2016-17.

In the southern parts of the reef, however, coral cover has shrunk by 4% since last year due to a population outbreak of crown-of-thorns starfish. Peter Mumby, chief scientist of the Great Barrier Reef Foundation, and his team are working to predict how reefs respond to climate change, and how their management can “take us on a better path.”

Sources: CNBC, The Guardian, Australian Institute of Marine Science

Monitor Backstory: Mining for global progress

What goes into writing a weekly survey of where in the world things are going right? A fair assessment of what credible “progress” actually is, and a determination to present a diversity of coverage. Staff writer Erika Page talks with editor Clay Collins about the Monitor’s long-running Points of Progress feature.

Essay

Keepsakes and memories: Finding, in the clutter, a life well lived

In this essay, the author sifts through his personal paper mementos that remind him of a life of perseverance, joy, and dignity.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By Bob Brody Contributor

Last year, preparing to move to Italy, I sorted through everything in our New York apartment: clothes, toys, china, board games – you name it. I had to determine what to give away, throw out, or ship overseas.

It forced me to review, remember, and relive my past.

I found the letter President Ronald Reagan sent to my father, congratulating him for his service to the deaf community; playbills for 1960s Broadway hits my nana had taken me to see. I had rejection notes from magazine editors, a ledger tracking my meager freelance earnings, and a typed letter from my lawyer uncle counseling me to quit fooling around and get a real job. I kept Father’s Day cards and a poem to my wife on our 40th anniversary.

Paper still has a purpose, I concluded. I had tangible proof of a marriage navigated, children raised, and struggles won or lost.

I did it mostly for me. But someday my successors may happen across these keepsakes. Perhaps they’ll be drawn to explore the history only our family can claim.

As legacies go, one could do worse.

Keepsakes and memories: Finding, in the clutter, a life well lived

Last year, getting ready to move to Italy from the United States, I sorted through every possession in our New York apartment belonging to our family of four. Clothes, shoes, toys, china, silverware, handbags, board games, cosmetics – you name it. My mission was to determine what to give away, what to throw out, and what to pack and ship across the Atlantic.

This exercise forced me to review, remember, and, in some cases, relive and reevaluate my past. Some surprises awaited me. For starters, in rummaging through all the material goods accumulated over a lifetime, I rediscovered just how much I value paper.

Yes, paper. There’s the letter from President Ronald Reagan that my father received in 1983 congratulating him for his service to the deaf community; the sympathy card my wife addressed to me, saying – only half-jokingly – “Because you are so annoying, my heart goes out to you”; and all the birthday cards our son and daughter received from my late beloved mother-in-law, Antoinette.

Oh, I had plenty of paper all right: playbills for Broadway hits such as “Oliver!” from the 1960s that my nana took me to see; a 1968 brochure from the Boy Scouts about careers in journalism; narrow scrolls from a miniature teletype detailing my interview with my mother about her experiences growing up deaf. I had rejection notes from magazine editors, a ledger tracking my meager earnings as a freelancer in my 20s, and a typed letter from my uncle the lawyer counseling me to quit fooling around for crying out loud and get a full-time job.

I perused it all for hours a day, a forensic forage that took me weeks to complete. I left no page unturned.

I kept all the items mentioned above. I also set aside a college term paper on Leonardo da Vinci (for which I received an A) and an essay for a course in human relations (a C-minus, the professor scrawling “phony” on it).

I kept a note from an early boss granting me a long-awaited raise, and a later note from a different boss congratulating me on my job performance. I also retained a cherished make-believe newspaper about me that our daughter created in my honor for Father’s Day, and a poem to my wife on our 40th anniversary.

Down the rabbit hole I went, following my paper trail, the hard copy of my life.

It proved to me that paper still serves a purpose, even with life going aggressively digital and all but paperless. Flipping through records that you can feel on your fingertips is a powerful trigger for memories. To me, paper is the ultimate mnemonic device. Today’s millennials may someday feel the same twinges of recollection scrolling through old text messages and Instagram posts.

Going through these documents was an opportunity to better know myself, to recognize who I was and how I’d changed.

The bulging folders I curated are now once again within easy reach here in Italy, stored largely in a three-drawer file cabinet in our garage. I have no regrets about what I decided to save and what to jettison. Almost nothing important in my life is untraceable. Somehow I’ve managed to get just about everything in writing.

In the end, my paper chase gave me tangible, irrefutable, verifiable proof of a life lived: a marriage navigated, children raised, business transacted, and struggles long since won or lost. It’s a life lived to the fullest.

Yes, I saved these papers for my own sake, as if to keep a fire burning to warm me through my third act. But I’ve looked beyond myself, too. I’m also seeking to preserve my family archive for the potential benefit of future generations, starting with our son Michael, daughter Caroline, and 4-year-old granddaughter Lucia.

For all I know, somewhere down the line my successors will happen across these keepsakes. They’ll thumb through this pulpy, fibrous stuff called paper, the sheets creased and crinkled, stapled and paper-clipped, a stain here, a rip there. No memory stick will have to be plugged in. There will be no link to click and nothing to download. And I hope they’ll be drawn into learning a little something about the history only our family can call its own.

As legacies go, one could do worse.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Softer approaches to jihadi threats

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

Two trends in Africa have prompted a challenge to the military model of countering terrorist threats. Each trend bears watching for the global struggle against terrorism.

The first is negative. During the past decade, the United States, France, and others have spent billions of dollars helping African governments and militaries fight Islamist extremism in countries upward from the Sahara. Yet violence by these groups has continued to grow. Those developments have given momentum to a second, more encouraging trend. As national militaries and central governments falter in Africa, local leaders are stepping forward. Their efforts to rebuild their communities are redefining what countering terrorism involves.

The world still relies on meeting violence with violence in responding to terrorism. Yet after more than two decades since 9/11, the wisdom of softer approaches may be gaining ground. Africa serves as a test case.

Softer approaches to jihadi threats

Two trends in Africa have prompted a challenge to the military model of countering terrorist threats. Each trend bears watching for the global struggle against terrorism.

The first is negative. During the past decade, the United States, France, and others have spent billions of dollars helping African governments and militaries fight Islamist extremism in countries upward from the Sahara. Yet violence by these groups has continued to grow. In addition, six countries in the region have seen attempted or successful military coups since 2020. Last Friday, Burkina Faso had its second putsch this year. That instability has prompted France to step back and reassess its military strategy in the region.

Those developments have given momentum to a second, more encouraging trend. As national militaries and central governments falter in Africa, local leaders are stepping forward. Their efforts to rebuild their communities are redefining what countering terrorism involves. Instead of waging war, they are battling corruption, breaking down traditional norms that perpetuate social inequality, and building trust between jihadis and villagers.

“The mediation of local conflicts will contribute to rethinking the paths to peace,” wrote Senegalese historian Mamadou Diouf in a preface to a recent study on reconciliation in the Sahel by the Geneva-based Centre for Humanitarian Dialogue. That involves, for example, local approaches to reconciliation and traditional justice, as well as upending practices that fuel economic grievance – like norms that sideline women and favor first-born sons over their younger siblings.

African countries “are gradually recognising the limitations of an overly centralized and securitised approach to addressing a threat that has become more localized than ever,” a new United Nations study of local counterterrorism responses noted last month. In its place, a “whole-of-society” approach, recognizing “the importance of local and non-security actors and the need to address the drivers and not simply the manifestations of extremist violence – has begun to gain traction, albeit gradually.”

It also signals the use of empathy and mercy to help soften the hard approaches to violent jihadis. One example is in Australia’s plan to repatriate more than 60 widows and children of slain Islamic State fighters. The women, who have Australian citizenship and were enticed or coerced to join the jihadi group, have been held in detention camps in Syria for years.

The move partly reflects a change in government in Canberra. Until a few months ago, Australia regarded the women as a potential security threat. But that view is increasingly out of sync with global attitudes. The European Court of Human Rights, for example, condemned France last month for refusing to repatriate its own nationals in similar positions. In the first-ever decision of its kind, the court found that denying a request for protection “made on the basis of the fundamental values” of democratic societies by vulnerable citizens to their own government was “incompatible with respect for human dignity.”

The world still relies on meeting violence with violence in responding to terrorism. Yet after more than two decades since 9/11, the wisdom of softer approaches may be gaining ground. Africa serves as a test case.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Finding my unbreakable relation to God

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Renate Lohl

We are all inherently capable of discerning our true, spiritual nature as God’s children – and experiencing the protection and healing this brings.

Finding my unbreakable relation to God

When I was growing up, I had the feeling that somehow other people had a more direct connection to God than I did. Inspiration seemed to come to them more easily, and they seemed to understand God better. I had had clear proofs of the effects of divine Love (which is another name for God), but I had the impression that my access to the Divine was less well developed.

I got the idea of simply asking God for better access to Him. Step by step, I received the answer, and it unfolded in a way that was completely natural.

I began by writing out spiritual descriptions for both bigger and smaller things that I was doing. Mary Baker Eddy writes in “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” “Metaphysics resolves things into thoughts, and exchanges the objects of sense for the ideas of Soul” (p. 269). So, I was resolving “things into thoughts,” or looking more closely at the qualities that these activities stood for.

When I graduated from Christian Science Sunday School, I decided that it would be good and right to read the Bible and all of Mrs. Eddy’s writings. Doing this taught me a lot about the Science Christ Jesus proved. Mrs. Eddy’s definition of Christian Science as the law of God made a deep impression on me. The complete quotation reads: “How would you define Christian Science? As the law of God, the law of good, interpreting and demonstrating the divine Principle and rule of universal harmony” (“Rudimental Divine Science,” p. 1).

Thoughts I’d had of a deficient relation to God disappeared in the joy I was now feeling for the logic and depth of divine Science and its immediate relevance to life. And so I finally did feel a direct connection to God!

Here is an example from that time. When I finished my time as a teacher’s aide in a preschool, I was looking forward to a cycling tour in Ireland, where I would enjoy the environment, the peace and quiet, and my conscious relation to God. I had prepared spiritually for the trip, claiming the divine protection that comes from the fact that everyone is guided by God’s love.

On the second day of the tour, I was taking a break in a field when a red car stopped. A man got out and came toward me. There was no one else to be seen anywhere around. There also weren’t any other cars on the country road.

After a short moment of extreme fright, I felt God’s presence become palpable, and my fear disappeared. I walked toward the road, which meant walking toward the man. From his look, I could tell that he wanted something from me that I most certainly didn’t want, and he smelled of liquor. He gripped my arms.

Nevertheless, I slowly continued in the direction of the road. I spoke to him quietly and firmly. The man released his hold on me, got into his car, and drove off. I continued riding on the route I had planned, thanking God all the way.

Despite this incident, I was able to continue enjoying my tour. For a couple of days, I had a bad feeling whenever a red car passed me. But this fear left as I prayed to understand that one of God’s divine ideas cannot force itself on another idea. This turned out to be one of the most beautiful trips I’ve ever taken, and I look back on it happily.

When I prayed for closeness to God, I learned that I am God’s individual reflection, no more and no less. Speaking metaphorically, it was as if I were no longer looking across a river to see other people – those with direct access to God – but had gotten over to the other side where they were. Everyone has this living, unbreakable, fully valid relation to God. Any argument to the contrary vanishes in the face of God’s love.

Originally published in German on the website of The Herald of Christian Science, German Edition, March 17, 2022.

A message of love

At the helm in space

A look ahead

Thanks for joining us. Come back tomorrow: We’re prepping a story about British poet Raymond Antrobus, whose new spoken-word album explores the experiences of deafness and perseverance.