- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usMonitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

What do you do with a million free avocados?

Yesterday, Philadelphia embraced the start of “Avogeddon.”

A nonprofit named Sharing Excess is giving away 1 million free avocados through Friday in Philly’s FDR Park. First come, first served. Bring your own tortilla chips or plates of toast.

The event is the single largest giveaway by the nonprofit, which delivers 120,000 pounds of food to Philadelphia hunger relief organizations each week. Its motto: “Using surplus as a solution to scarcity.”

Sharing Excess was launched by a college student. Six years ago, Evan Ehlers fretted that the remaining unused credit on his and other student meal cards at the city’s Drexel University would go to waste. He purchased 50 to-go boxes from the cafeteria and delivered the meals to those in need.

“It was actually one of the most meaningful days of my life,” Mr. Ehlers told Philadelphia magazine in 2021. “In a small way I felt like I was making this connection and solving a problem.”

The nonprofit that he and his roommate founded still collects surplus meal credits from students. But its main operation offers a local solution to a much larger problem in the United States.

Each year, over 40% of all food – 108 billion pounds – is wasted, according to the nonprofit Feeding America. When unwanted food degrades, it produces methane. The Environmental Protection Agency estimates that uneaten food produces emissions “equal to the annual CO2 emissions of 42 coal-fired power plants.”

Mr. Ehlers realized that some farmers, wholesalers, and grocery stores don’t have the time or resources to deliver leftovers to food banks. So his organization drives its vans to them. Since 2018, it has rescued fresh food with a total retail value of over $19 million.

Yet Sharing Excess has never dealt with anything like the sudden glut of avocados from South America. It was too much even for the local food banks. The giveaway at FDR Park – featuring Mr. Ehlers in an avocado costume – attracted wait lines of over an hour.

“The word really got out there,” Mr. Ehlers told a local news outlet. “We’ve never had a distribution event like this.”

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Patterns

Next prime minister’s challenge: Regaining Britons’ trust

The deeper challenge facing Britain has less to do with the fortunes of individual politicians – or even one party – than the health of Britain’s democracy, and the sense of connection between the politicians and those they’re elected to serve.

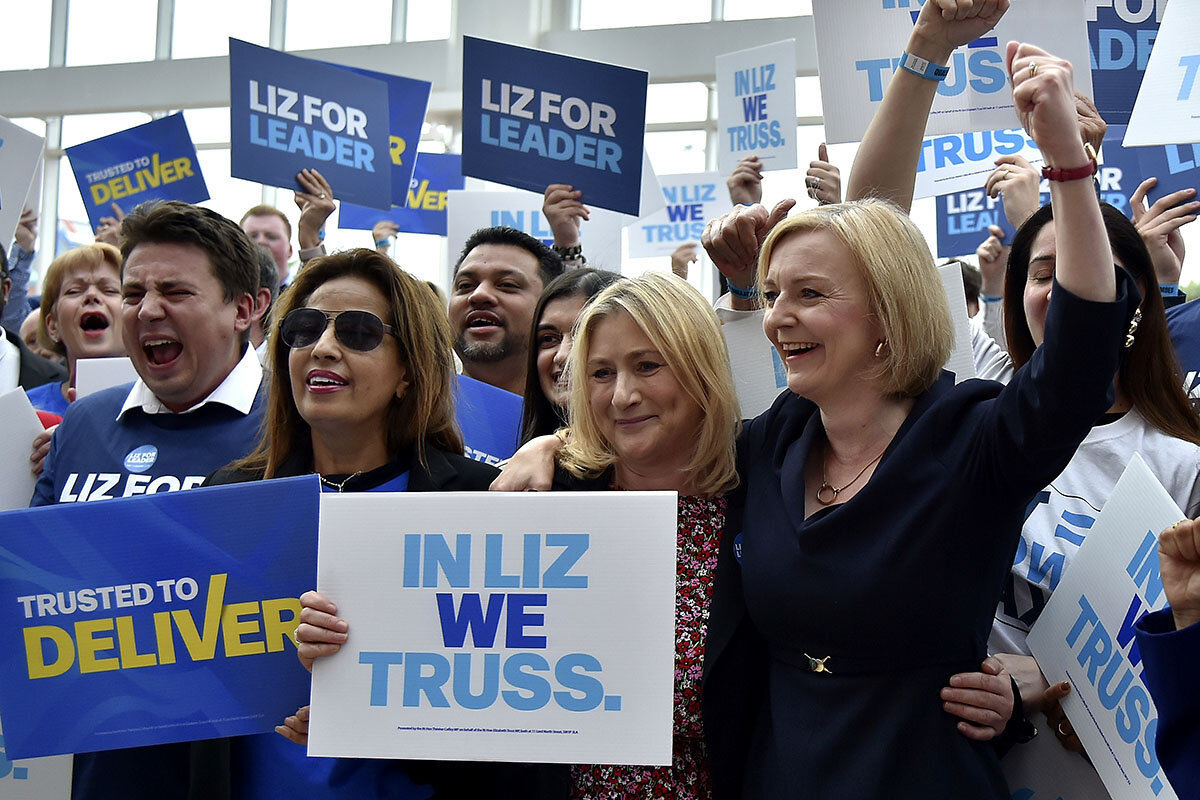

British Prime Minister Liz Truss’ departure will leave her Conservative Party – and the country – facing a political challenge with no obvious, early resolution. And it’s best understood by looking not at how Ms. Truss’ tenure is ending, but at how it began.

As Ms. Truss settled into Downing Street in September, the country came together in an extraordinary outpouring of grief, admiration, appreciation, and respect for the late Queen Elizabeth II – a demonstration of a gentle, caring, unifying sense of community vanishingly rare in most 21st-century democracies.

The test now for Britain’s Conservatives will be to find some way of tapping into that reservoir of community, to reconnect with voters increasingly mistrustful not just of the party, but the institutions of government.

The Conservatives’ immediate task is daunting enough: to settle on an agreed successor. Never in the party’s recent history has it been so riven by personal and ideological rivalries.

Yet the deeper challenge lies beyond the Westminster bubble. Can any party somehow animate and nurture the sense of community so dramatically brought to the surface by the response of millions of Britons to the passing of a 96-year-old monarch almost none of them had ever met?

Next prime minister’s challenge: Regaining Britons’ trust

None but the most hardhearted critics of British Prime Minister Liz Truss could have wished on her the manner of her departure: a terse, humiliating resignation statement on Thursday in front of the famous door of No. 10 Downing St. – almost exactly 24 hours after telling Parliament, “I’m a fighter, and not a quitter!”

But if her personal agony is drawing to an end, her departure next week will leave her ruling Conservative Party – and the country – facing a political challenge with no obvious, early resolution.

The Conservatives’ immediate task is daunting enough – to settle on an agreed successor. Never in the party’s recent history has it been so riven by personal and ideological rivalries.

Yet the deeper challenge lies beyond the Westminster bubble. And it’s best understood by looking not at how Ms. Truss’ tenure is ending, but at how it began.

Not at what her departure means for individual politicians, but what it means for the health of Britain’s democracy, and the sense of connection between the politicians and those they’re elected to serve.

Ms. Truss took office in early September following her traditional audience with the British monarch, in what turned out to be Queen Elizabeth II’s last public engagement.

As Ms. Truss settled into Downing Street, the country came together in an extraordinary outpouring of grief, admiration, appreciation, and respect for the late queen – a demonstration of a gentle, caring, unifying sense of community vanishingly rare in most 21st-century democracies.

The test now for Britain’s Conservatives will be to find some way of tapping into that reservoir of community, to reconnect – after a dozen years in power under four different prime ministers – with voters increasingly mistrustful not just of the party, but the institutions of government.

Ms. Truss’ six weeks in power, the shortest tenure of any British prime minister, have made such a reconnection both more urgent and more difficult.

By launching a new economic policy with tax cuts for business and wealthy individuals funded by billions of pounds’ worth of additional government debt, she unsettled the financial markets. The result was to push mortgage rates and inflation higher, and drive down the value of the British pound. With the economic effects of the war in Ukraine already squeezing family budgets, her government suddenly made things worse.

Yet the sense of grassroots alienation her successor will have to address goes beyond economic issues.

It’s rooted in a profound change in the Conservative Party since the 2016 referendum that ended Britain’s decadeslong membership of the European Union.

The Conservative prime minister at the time, David Cameron, wanted to stay in the EU. So did most of the party’s members of Parliament. But from that point on, a party that had dominated British politics for decades with a mix of traditional center-right policies and pragmatism made a single ideological issue, Brexit, a litmus test for advancement.

Mr. Cameron’s successor, Theresa May, had backed staying in the EU. So had Ms. Truss. But both became prime minister as converts to Brexit. The leader who Ms. Truss succeeded, Boris Johnson, was not only a Brexit backer, but also the leader of the campaign to leave the EU.

The Brexit issue itself hasn’t necessarily hurt the Conservatives. Like former President Donald Trump’s appeal to working-class voters in America, Mr. Johnson used Brexit’s populist “take back control” appeal to capture constituencies long held by the opposition Labour Party in a landslide election victory three years ago.

What has eroded the connection with voters has been a more general sense that a narrowly focused ideological fixation on Brexit has become almost a Conservative parlor game in Westminster, crowding out concern for the real-life needs and priorities of voters.

Mr. Johnson was forced out of office this summer by a similar kind of remoteness: He broke the pandemic rules he had imposed on the rest of the country by partying in Downing Street. For Ms. Truss, it was her ultimately harmful “post-Brexit” economic plan – rooted in a vision of buccaneering Britain, freed from European rules and regulations, outgrowing its former partners.

Whoever now takes over – and there have been reports that Mr. Johnson himself is contemplating a comeback – will now have to reckon with polls that give the long-struggling Labour Party a lead of more than 30 percentage points.

The new prime minister may get a slight bump in the polls. But since he or she will be the second successive prime minister to be chosen by the ruling party, not by British voters, they will be under strong pressure to call fresh elections.

That’s why the need to reconnect with voters will matter at least as much as the identity of the next party leader, or even any specific policies.

Ultimately, what will matter is not how the Conservatives or the Labour Party lead Britain over the next few years.

It goes deeper. Can either party somehow animate and nurture the sense of community so dramatically brought to the surface by the response of millions of Britons to the passing of a 96-year-old monarch almost none of them had ever met?

Belarus may be set for war with Ukraine. But at what cost to itself?

Belarus looks like it may be planning to enter the war in Ukraine. But that could endanger its own independence, if it hastens its integration with Russia.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Belarus appears to be edging toward directly joining in the war in Ukraine, under pressure from Moscow. At a meeting this month, Belarusian President Alexander Lukashenko and Russian President Vladimir Putin agreed to create a joint “regional group of forces” to augment Belarus’ 70,000-strong army with about 9,000 Russian troops.

The existence of a credible striking force hovering in the north will be a continuing worry for Kyiv. But experts say Belarus may also be hastening its own absorption by Russia.

Mr. Lukashenko has long resisted full integration with and political subordination to Russia. To do so, he has played a complicated game of ceding to the bare minimum of Moscow’s demands while flirting with the West and keeping the levers of local control firmly in his own hands.

But the insertion of Russian troops into the country is a new move and suggests that a permanent merger of the two security establishments is in the offing.

“We are moving toward the full-fledged erosion of Belarus’ military and political sovereignty at the very least,” says Artyom Shraibman, a Belarusian political scientist. “It’s becoming harder and harder for Lukashenko to play the game of keeping his autonomy while using Russian resources.”

Belarus may be set for war with Ukraine. But at what cost to itself?

Eight months ago when Russia invaded Ukraine, one of its key fronts was launched from Belarus. Since then, Russia’s only major ally has remained on the sideline of the conflict between its two neighbors.

But now, Belarus appears to be edging toward directly joining in the war, under pressure from Moscow. And experts say that by doing so, it may ultimately be hastening its own absorption by Russia.

At a meeting this month to discuss the “increasing threat level” emanating from NATO states to the west, Belarusian President Alexander Lukashenko and Russian President Vladimir Putin agreed to create a joint “regional group of forces,” to augment Belarus’ 70,000-strong army with about 9,000 Russian troops.

Social media has been full of reports of Russian troops arriving in Belarus, and also difficult-to-interpret videos apparently showing trainloads of Belarusian heavy equipment moving eastward. Experts differ as to whether this means Russia is drawing on Belarus’ large stocks of Soviet-era tanks, mobile artillery, and armored vehicles to replenish its own forces, or if the equipment is being sent for modernization in Russian factories.

The level of military cooperation, which will create at least one joint Russian-Belarusian division-sized force, is something new.

Russian troops invaded Ukraine last February from Belarusian territory, but Belarus’ own forces did not participate. Kyiv is warning that the new military grouping might be preparing to open a whole new front against Ukraine. Even if Mr. Lukashenko remains disinterested in committing his army to the war, the existence of a credible striking force hovering in the north will be a continuing worry for Kyiv.

Few options for Minsk

Minsk insists that it fears Western “provocations,” given the concentration of exiled Belarusian opposition figures in neighboring NATO countries such as Poland and Lithuania, who might try to create trouble for Russia amid the current Ukraine war turmoil through political destabilization in Belarus.

Belarus has theoretically been part of a “union state” with Russia since 1999, one that confers a lot of advantages to Minsk. But in practice, Mr. Lukashenko has resisted full integration and political subordination, playing a complicated game of ceding to the bare minimum of Moscow’s demands while flirting with the West and keeping the levers of local control firmly in his own hands.

Yet his ability to do that was deeply compromised when his rule was threatened amid mass protests two years ago. He quashed the uprising, but doing so left the West enraged at his suppression of opponents and Russia as his only source of political and economic support.

Even though Mr. Lukashenko’s rule seems more entrenched than ever, the insertion of Russian troops into the country is a new move and suggests that a permanent merger of the two security establishments is in the offing.

“We are moving toward the full-fledged erosion of Belarus’ military and political sovereignty at the very least,” says Artyom Shraibman, a Belarusian political scientist who currently lives in Ukraine. “The options for Lukashenko are narrowing. Much will depend on the results of the war. Will Russia be able to stabilize the front? How will Russia’s mobilization work out? Will Belarus get directly involved or not? What if Russia loses the war, or it reaches a stage of nuclear escalation with the West? Too many questions without answers.

“But it’s becoming harder and harder for Lukashenko to play the game of keeping his autonomy while using Russian resources,” he says. “For now, Belarusian trade with Ukraine is about zero, while sanctions have greatly reduced trade with the West. Russia is increasingly the only option for trade, finance, and political support, and the only question is how long it will take to completely absorb Belarus into Russia’s sphere. I suppose Russia might lose the war before Belarus completely loses its sovereignty, but the process right now is very alarming.”

An unpopular conflict?

Russia’s wartime exigencies may be not only accelerating the pace of Russia’s efforts to integrate Belarus, but also changing Moscow’s concept of the future Russian Federation. If Moscow wins the war in Ukraine, it will result in large parts of eastern Ukraine being permanently digested by Russia. With that process underway, Moscow’s planners may have less patience for the bureaucratic complexities of the union state, and look for more direct ways to incorporate Belarus into an expanded Russia.

“What we are seeing right now is connected with urgent military needs,” says Fyodor Lukyanov, editor of Russia in Global Affairs, a leading Moscow-based foreign policy journal. “The big new military grouping in Belarus could be used to attack Ukraine from another angle, or at least divert Ukrainian forces from other fronts. I don’t think either Putin or Lukashenko is entertaining any grand long-term thoughts.

“Lukashenko has clearly made the decision to be helpful because he has no other options but to bet on Putin and Russia,” he says. “The future of Belarus’ relationship with Russia – whether it will become part of Russia or something else – will depend on how things progress on the battlefield. If Russia fails in Ukraine, that will have huge repercussions in all areas, including Belarus.”

Most analysts doubt that Mr. Lukashenko wants to get directly involved in the conflict.

“The Belarusian army is about 70,000 men, but its combat-ready component is much smaller,” says Andrey Suzdaltsev, an independent Belarusian expert living in Moscow. “The army is really too weak to actually face the Western-armed Ukrainian forces with their fighting experience. By forming this joint grouping with Russia, Lukashenko wants to imitate participation in the special operation without actually doing anything.”

A random telephone survey of 1,000 Belarusians conducted in September by Andrei Vardomatsky, a leading Belarusian sociologist currently living abroad, found that support for Russian actions in Ukraine is roughly split, with 41.3% approving and 47.3% opposed.

But when asked about direct participation in the war, Mr. Vardomatsky says, “85% of respondents gave a negative answer, and 11% said they would react positively to it. Asked how they feel about using Belarus’ territory and military infrastructure to implement Russia’s military actions in Ukraine, more than 62% said they were against and 29% said they were positive.”

“He’s in the same boat with Putin”

Alexander Khramchikhin, deputy director of the Institute for Political and Military Analysis in Moscow, says he does not know the purpose of the joint force currently gathering in Belarus. But he suggests it’s probably a hedge against unexpected developments on Russia’s western flank and a bid to bolster Mr. Lukashenko’s grip on power. If it worries the Ukrainians and makes them divert forces, so much the better, Mr. Khramchikhin adds.

Russia is facing troubles around the post-Soviet region, aggravated by Western meddling, and needs to take actions to boost stability, says Vladimir Zharikhin, deputy director of the Kremlin-funded Institute of the Commonwealth of Independent States in Moscow.

“The situation is causing a more rapid consolidation of ties with friendly countries, like China and Belarus,” he says. “Lukashenko has realized that he’s in the same boat with Putin, and he faces threats from NATO. That’s why this military grouping has been formed, and the integration process in general is speeding up.”

Ian has passed. For many in Florida, the displacement lingers.

Many in southwest Florida need new places to live after Hurricane Ian. Federal and local aid gives a boost, but people are grappling with difficult choices.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Brittany Ward’s rental unit already had a crack in the roof before Hurricane Ian. The storm split it into seven more. With other damage, it wasn’t habitable.

Ms. Ward is one of the thousands of Floridians displaced by one of the strongest storms in United States history – relying on the help of their own community while also wondering whether it can still be home.

Some stay in hotels or with family or friends (Ms. Ward has done both). Some camp out in tents or mobile homes or trailers. Many face lengthy waits before their homes are rebuilt or repaired.

As of Tuesday, the Federal Emergency Management Agency has a transitional shelter program supporting 1,468 Florida households – 3,817 people. The agency also has opened 15 disaster recovery centers where Floridians can apply for aid. The Red Cross and its partners have set up 10 shelters, housing around 1,000 people.

Ms. Ward, with two children, is holding onto a job and looking for a new rental here. But she’s also thinking about a possible move to North Carolina.

“They have seasons,” says Ms. Ward. “That’s my biggest thing – I’ve always wanted my kids to have seasons.”

Ian has passed. For many in Florida, the displacement lingers.

Southwest Florida isn’t what it used to be to Brittany Ward.

She grew up in Cape Coral, a canal-filled city just across the Caloosahatchee River from Fort Myers. It had a small town feel, she says. There were skating rinks, beaches, and parks, she says. Always something to do.

By the time she became a mom, the town had grown crowded and prices had risen. The skating rinks closed. Her five kids had more fun inside anyway. But there were still beaches and barrier islands for the weekends. There was still the yacht club – the same one Ms. Ward visited as a kid.

Hurricane Ian took that away.

Wind and storm surge swept through the area, taking almost everything that – to Ms. Ward – made Cape Coral Cape Coral. The yacht club was destroyed. Bridges to the nearby barrier islands collapsed. “Our own beach is gone,” she says. “It’s gone”

Her home is too, almost. Her rental already had a crack in the roof before the storm. The storm split it into seven more. With other damage, it wasn’t habitable. Ms. Ward, who spoke to the Monitor briefly in person and again later by phone, drove her kids to Orlando and back multiple days for an available hotel. Then for a time they bunked near the damaged home with her sister, who has a husband and three kids. As of Oct. 9, Ms. Ward was looking for a new rental. Her landlord told her it would take weeks to repair the old one.

Ms. Ward is one of the thousands of Floridians displaced after the area was all but annihilated by Hurricane Ian, one of the strongest storms in United States history. The hurricane caused tens of billions of dollars in damages, including to thousands of homes. And while the area hosts many snowbirds and second-home owners, some of its permanent residents have now become temporary refugees – relying on the help of their own community while also wondering whether it can still be home.

Some stay in hotels, though it’s difficult to find vacancies. Some stay with family or friends. Some camp out in tents or mobile homes or trailers. Many face lengthy waits before their homes are rebuilt or repaired. Some, like Ms. Ward, are searching for somewhere new.

“I feel like if I don’t go now, with this, something worse could happen,” she says.

As of Tuesday, the Federal Emergency Management Agency is supporting 1,468 Florida households – 3,817 people – through its Transitional Sheltering Assistance program, says Renee Bafalis, a FEMA spokesperson. In addition, the agency has opened 15 disaster recovery centers, where Floridians can speak with representatives and apply for aid. The Red Cross and its partners have 10 shelters, housing around 1,000 people affected by the hurricane.

An escape, and a hard recovery

Two days before the storm, Ms. Ward and her children squeezed into her Chevy Malibu and drove to the Red Roof Inn in Orlando. It was the closest hotel she could find, still three hours and four minutes away.

Even where they were, she says, the storm was “petrifying.” As it passed, she began to see images of the damage. So many of the places she would take her kids were being destroyed.

But they were safe, and soon after the hurricane ended she drove back down to assess the damage. She photographed the cracks in the roof – some in the living room, some in her kids’ bedrooms. All this she sent to her landlord, she says, who wasn’t responding to her.

The next week, the family drove back and forth from Orlando, so Ms. Ward could do her job at a permitting office. Her kids, age 8 and 14, joined her.

It was a relief when her rental’s power was restored. Ms. Ward drove over and began to clean up. But a burst water heater, coupled with a septic backup that left an unbearable stench, displaced her again.

Still, Ms. Ward has been getting meals for neighbors, friends, and family at the local food bank – where she’s been going at lunchtime.

Aid like that has become common around the area – from hard-to-reach islands just off the coast to Walmart parking lots, where displaced people are camping out in RVs and tents.

Since the hurricane, Ramon Martinez has been living in a single-person tent next to the Walmart where he works. He was staying in a shelter before the storm, but it wasn’t safe for a hurricane, and he had to move from place to place before getting an offer to stay an hour away. He couldn’t take it, he says, wearing a khaki hat and T-shirt as cars pass behind him. It was too far from his job.

Relief stations: Bridge to an uncertain future

Aid stations providing food, water, showers, and laundry have followed people’s needs, serving hundreds a day in different locations.

Those services helped Kitty Achors get through last week.

Ms. Achors is a 16-year resident of Siesta Bay, a neighborhood that suffered some of the worst losses – including a few lives – during the hurricane. She left just before the storm for an inland hotel, only to lose her room after a few days because emergency workers needed a place to stay.

Her son Greg drove down from Jacksonville as soon as I-75 opened, and they both went back together. There was nowhere else to go, she says.

They came back about a week later with Mr. Achors’ blue GMC Sierra and a rented mobile home hitched to the back. Her home is completely destroyed. More than six feet of water surged inside, warping the walls, flipping the king size bed, and dragging her front porch across the street.

Ms. Achors and her son parked their trailer in front of a restaurant near San Carlos Boulevard. The Walmart across the street closed its lot to anyone staying overnight, but has become a hub for different aid stations during the day.

The Achors met with a FEMA representative after waiting on hold several hours three days in a row. The federal response, to them, feels disorganized. Her house wasn’t insured anyway, and they expect the neighborhood to be condemned. As of Oct. 11, they were going back to Jacksonville – and for Ms. Achors, soon, even farther away.

She has family and a place to stay in Indiana, she says. “I just like Florida. I don’t like Indiana winter,” she says. “Now I’m going to have to learn to like it.”

Leaving a life in Florida behind?

Ms. Ward has also set her eyes out of state. Waiting to hear back about another rental, which she could move into immediately, she described her dream to move to North Carolina.

She’s visited a couple times to see friends, and spent part of her time in the Orlando hotel applying for jobs in the state. Taking care of family has, in part, kept her down south her entire life. She felt like she didn’t have a choice to leave before. Now she does.

She says she hasn’t heard back on any jobs yet. But the schools there are good, there are mountains, and there’s a better life for her children, perhaps.

“They have seasons,” says Ms. Ward. “That’s my biggest thing – I’ve always wanted my kids to have seasons”

Can Mt. Kenya’s porters get the same respect as Mt. Everest’s?

Unlike Mount Everest’s sherpas, the porters of Mount Kenya still endure low pay and little respect. Can mountaineering culture shift from gratifying Western tourists to achieving best employment practices?

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

-

By Kang-Chun Cheng Contributor

On Mount Kenya, Africa’s second-highest mountain after Kilimanjaro, porters make expeditions not only possible, but downright comfortable. They set up and take down tents, haul clients’ gear, and cook three full meals each day – before their guests even step foot into camp.

These porters are highly competent, both physically and in their knowledge of capricious mountain environments. Elsewhere, most notably the sherpas on Mount Everest, the sometimes invisible work done by local guides is finally earning rightful recognition. Yet the porters upholding East Africa’s largely informal mountaineering industry remain woefully underpaid, and face a long journey for recognition.

And the growing popularity of mountaineering in Kenya may bring fresh challenges. Rather than fostering a healthy local economy, new moves to raise standards in the sector to match global standards risk shutting out local guides who are knowledgeable and experienced, but can’t afford expensive certifications.

Guide Peter Naituli believes the flexibility of Kenya’s nascent industry is its biggest strength.

“The informal nature of the outdoors industry here allows locals to benefit from working on the mountain,” he says. “There’s a lot more freedom since it’s not as regulated as Western countries.”

Can Mt. Kenya’s porters get the same respect as Mt. Everest’s?

Only at twilight, after their clients have been fed and are taking in the expansive Afro-alpine views, do the porters finally begin cooking for themselves. And not the pasta, salads, and curries that they’ve been preparing for their clients – but Kenyan dishes. A pair of young men huddled over a sufuria (pot) stir ugali (maize meal porridge) over a charcoal fire. There’s also wet-fry beef and sauteed greens – hearty foods, perfect fuel for long days.

Here at Likii North Camp, nearly 4,000 meters (13,123 feet) high, the thin, oxygen-poor air can sometimes cause altitude sickness in the uninitiated. But to porters who come from nearby villages, these high slopes are a second home.

On Mount Kenya, Africa’s second-highest mountain after Kilimanjaro, porters make expeditions not only possible, but downright comfortable. They set up and take down tents, haul clients’ gear, and cook three full meals each day – all accomplished before their guests even step foot into camp.

These porters are highly competent, both physically and in their knowledge of capricious mountain environments. Elsewhere – the most high-profile case being sherpas on Mount Everest – the sometimes-invisible work done by local guides is finally earning rightful recognition. Yet the porters upholding East Africa’s largely informal mountaineering industry remain woefully underpaid, observers say, and face a long journey toward proper recognition.

And the growing popularity of mountaineering in Kenya may bring fresh challenges. Rather than fostering a healthy local economy, new moves to raise the sector to match global standards risk shutting out local guides who are knowledgeable and experienced, but can’t afford expensive certifications.

Culture of recognition

David Miano has provided support to hundreds of trips in his two decades working as a freelance porter. Eight years ago, he became a certified guide after training with James Kagambi, the first Kenyan national to summit Everest.

“There have been many changes over the years,” says Mr. Miano, who comes from the small town of Naromoru, a base for those ascending Mount Kenya.

Some have been for the better. Porters’ daily rates have gone up from around 50 cents when he started to roughly $8.40 today. But tipping, a vital salary component for porters, is still not compulsory. Still, Mr. Miano prefers that there’s no set day rate. “It feels more like a conversation between the porters and the client,” he says.

Conditions on the mountains also dictate client interest, trickier now that the weather has become more erratic due to increasing extreme weather events. When business is slow, Mr. Miano takes odd jobs like fixing fences for the state tourism board’s Kenya Wildlife Service.

Renson Muchuku, head of outdoor education at Savage Wilderness, East Africa’s largest guiding company, says his company has established a tipping ceremony at the end of every expedition, where the clients congregate with the porters to thank them properly.

Despite these nudges in the right direction, a culture of recognizing the crucial role of porters hasn’t taken root. It’s not uncommon for people to say, “Oh, I didn’t catch our porters’ names,” says Alex Zachrel, one of the few American mzungu (non-African) guides on Mount Kenya. “Like, what do you mean? You were with them for four days.”

As night sets in

A sharp chill sets in the moment the sun dips behind the jagged peaks surrounding the camp. Temperatures here drop as low as minus 10 degrees Celsius (14 degrees Fahrenheit) at nighttime. Students from the Nairobi-based German School bundled up past their chins waddle about, sipping hot chocolate and snacking on popcorn.

The following morning, tents are frozen over. The delicate helichrysum flowers studding the terrain seem unperturbed, twinkling in the gentle morning light. The porters are already hustling back and forth, laying out sausages, eggy toast, and fruit.

Excitement buzzes among the students; small dramas over lost gloves and homesickness are quickly placated by the necessity to forge onward.

As views of Batian emerge – at 5,199 meters (17,057 feet), the highest peak – Mr. Zachrel points toward the spires, where swirling clouds occasionally release a flurry of snow. “Peter should be up there with some clients now,” he says, “unless the weather forced him to bail.”

Peter Naituli, son of a Kenyan father and Norwegian mother, grew up in remote Nakuru County in central Kenya. He believes the flexibility of Kenya’s nascent industry is its biggest strength.

“The informal nature of the outdoors industry here allows locals to benefit from working on the mountain,” he says. “There’s a lot more freedom since it’s not as regulated as Western countries.”

But it’s a bit of a Catch-22. With more training and resulting certifications, porters and guides could charge their clients more. But to benefit locals, these courses would have to be affordable and accessible. For now, few can afford a few hundred dollars for an outdoors certification course when the typical salary in Kenya is under $600 a month.

Not everyone agrees that informality is an advantage. Mountains, after all, intrinsically have the power to kill. “You can prepare as much as possible, think of everything, and even then, there’s an element of risk that’s beyond your control,” Mr. Naituli says.

A few years ago, a guide trying to free a stuck rope died. His clients were stranded on a ledge overnight, before eventually making their way down. And in 2015, a 14-year-old called Warren Asiyo died from acute mountain sickness while on a church trip.

Warren’s mother, Connie Cheshire Asiyo, channeled her grief into increasing transparency within Kenya’s outdoor industry. She established The Warren Foundation, which partners with Kenya Wildlife Service to bolster guide and training certification to prevent such future tragedies. “Our organization has noted a decrease in accidents since 2017. It helps to be making some noise.”

Lilian Wamathai, an instructor at Savage Wilderness, is optimistic about the industry’s future as Kenyans are beginning to embrace and appreciate outdoor activities more, investing more money and time in the sector. The grassroots Porter and Guide Association is partnering with Kenya Wildlife Service to gazette regulations. For instance, they’ve determined that porters’ packing weights should not exceed 35 kg (77 pounds).

Ms. Wamathai believes professionalizing a previously informal industry will cushion and protect local employees’ interests in particular.

At Shipton’s Camp

At Shipton’s Camp, altitude 4,260 meters (13,976 feet), a stopover before Point Lenana (Mount Kenya’s third-highest peak), the students gather for a summit eve briefing: 3 a.m. wake-up, summit attempt to catch the sunrise, and then hiking back down – over 18.5 miles of walking in total.

One classmate in particular had been woozy ever since the group reached higher elevation – he’s been sitting listlessly as his friends chatter around him, barely picking at his food.

Mr. Zachrel and his team monitor the students with experienced eyes.

At 11 p.m., they opt to evacuate the student. The required number of guides with medical training and a few porters begin the long hike down in the dark. Helicopters can’t fly into Shipton at night; waiting until dawn could be fatal.

Meanwhile, the student’s classmates begin walking the other way. They trudge up the steep ridge of Lenana, the vault of stars overhead fading fast with the imminent dawn. By the time they return to camp, their classmate is back to safety, and the porters have laid out another hot, delicious breakfast for them.

This reporting was supported by the International Women’s Media Foundation’s Howard G. Buffett Fund for Women Journalists.

Essay

Wash, dry, fold, connect

Finding and joining new communities is a part of growing up. And sometimes this sense of belonging is found in an unexpected place.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By Noah Davis

I was in a new state at a new school and needed something solid to stand on: a place to feel grounded.

I also needed to do laundry, so I walked to a nearby laundromat and stuffed a machine with my clothes.

The washer did its job. The dryer did not.

“Come back again,” the female attendant called.

Her name was Sandy, I learned later, after I’d helped her stop a washer that had broken loose and was lurching across the floor.

Next time, Sandy told me dryer No. 8 was the best.

It went on like this. I’d do laundry once a week, and Sandy and I would talk while I folded.

I began to recognize others there: workers taking breaks by the door, a mother and her infant, the vending machine man who’d throw me a bag of Cheetos.

But Sandy was the center. For nearly three years, we’d talk. If one of us missed a week, there was a note of concern for the other’s absence, a note of joy at their return.

I’d found my solid place to stand.

Wash, dry, fold, connect

I didn’t want to do anything but laundry. It’d been about 10 days, and I’d worn the same pair of socks for five.

The first few weeks of grad school had been a whirlwind of classes and teaching in a constant state of never knowing where I was. The large state university I attended was as big as a small city, and it would be months before I figured out where the student health center was.

I was in a new state, at a new school, studying something I’d never formally studied before. I felt I was treading water, looking for something solid to stand on: a place or group of people where I could feel grounded outside the classrooms where I’d inevitably spend most of my time.

The 17th Street Coin Laundry was four blocks from my apartment, and I had 10 bucks in quarters ready. I walked through the automatic doors and stuffed the first available machine with my clothes.

As I struggled to close the washer door, the woman working behind the counter told me to give it a good smack with the heel of my hand.

The washer did its job, yet even after an hour, the dryer I’d chosen seemed to have barely warmed my clothes. I left, having decided to air-dry them on my car in the August heat.

At least my socks would smell fresh.

“Come back again,” the female attendant called.

A month later, I learned her name was Sandy, which she told me after I’d helped her stop a washing machine from lurching across the floor. I was grading poems at a linoleum-topped table when one of the industrial washers broke loose from its brackets and skipped an inch into the air with every revolution. I sprinted to the machine and held on while she unplugged it.

“Like a bucking bull,” I said.

“Might weigh more,” she replied, smiling.

That next week, Sandy told me dryer No. 8 was the fastest.

It went on like this. I’d do laundry once a week, usually Thursday or Friday. Sandy worked Tuesday through Saturday and we’d talk small while I folded clothes. She told me about her son and his grades, the new puppy they’d just adopted. She was fascinated that I was studying poetry. She teased that it was harder making a living as a poet than as a laundromat attendant. Even then I knew she was probably right.

Over the course of my time in grad school, I formed a community within my department and on the basketball courts of the university, but the community I felt at the laundromat was the first I’d built as an adult without the scaffolding of school or sports. It was refreshing to spend an afternoon in a place where no one was asking about poetry submissions and no one cared if I missed every shot in a pickup game. The laundromat was where I was Noah, the young man who did laundry on Thursday or Friday.

But even in the quotidian cycles of laundry, there were moments of drama.

On two occasions, dryers caught fire – thankfully not No. 8. Sandy had to use the fire extinguisher, but the only casualty was a pair of underwear.

A car caught fire, too. It was in the parking lot, and the driver was sleeping at the table next to me. We had to yell “Fire!” twice before he woke up. The owner of the liquor store next door got to the scene before Sandy.

Sandy asked me why I was always there when things burst into flames. I tried to imagine the dull life I’d be living if I had a washer and dryer in my apartment.

I came to recognize others in the laundromat: the workers who took cigarette breaks by the door, the smoke wafting back into the lavender

detergent-scented air; the mother whose baby slept or wailed in its carrier while she did laundry; the vending machine man who threw me a bag of Cheetos as he replenished the empty metal spirals.

But Sandy was the pillar of my laundromat community. For nearly three years and almost every week, I’d do laundry and talk with her. We checked on each other, expected the other to be there. We asked where the other had gone when we missed a week. There was a note of concern for the other’s absence, a note of joy at their return.

I’d found a place to stand on solid ground.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

The very model of a modern major economy

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

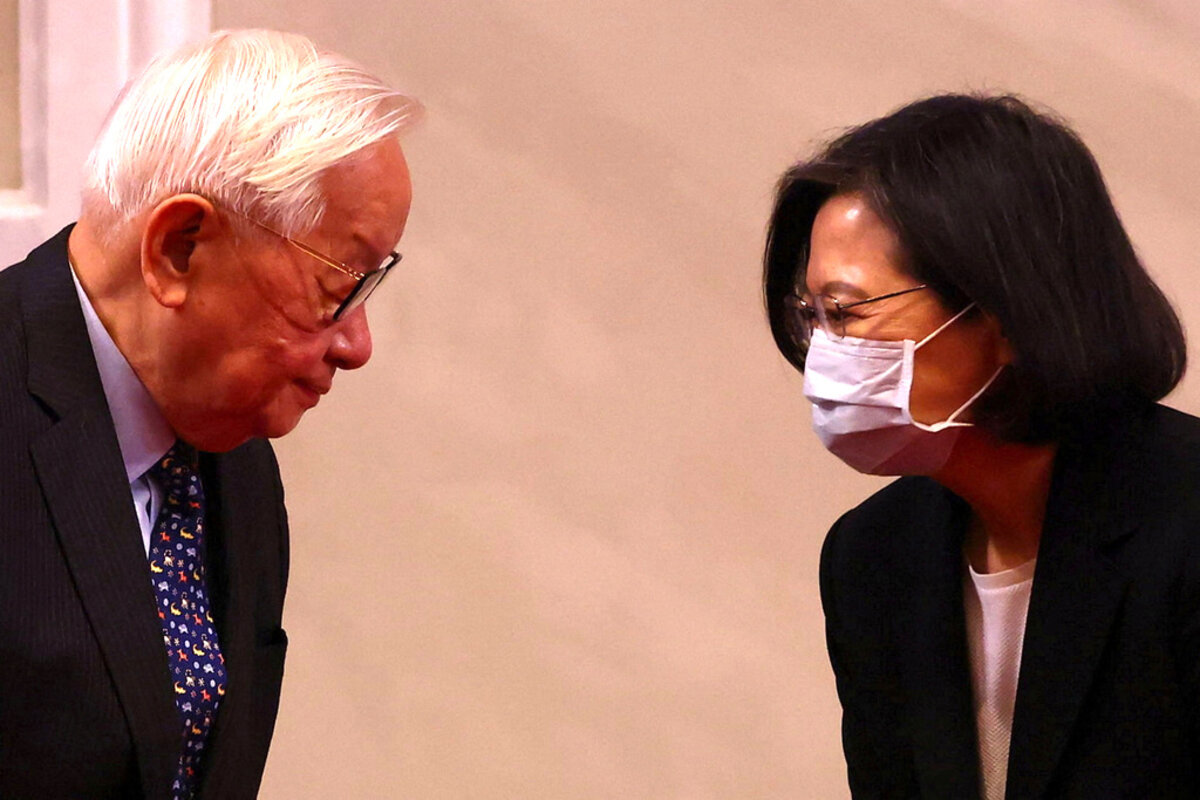

In a bit of bad news for Taiwan, the government said Thursday that export orders had dropped for the third time this year. The good news was that Taiwan released economic data at all and on time, a sign of its democratic openness.

In contrast, China decided to delay the release of the latest figures for its economy Monday. The official silence was perhaps to prevent any disappointing numbers from embarrassing Xi Jinping this week as he secures a third term as Communist Party leader. China’s gross domestic product per capita could be falling while Taiwan’s is expected to become the highest in East Asia this year.

Taiwan still struggles as a young democracy – its first direct presidential election was 24 years ago. Yet its people have strongly embraced the need for transparency and integrity in government, starting with economic data. In contrast, Mr. Xi has “reversed course from his predecessors’ emphasis on humility and openness to focus on national pride and self-sufficiency,” as The Wall Street Journal puts it.

As a model of governance, Taiwan surpasses the one touted this week by China’s ruling party. The world just needs to notice which country is releasing economic data, good or bad, and on time.

The very model of a modern major economy

In a bit of bad news for Taiwan, the government said Thursday that export orders had dropped for the third time this year. The good news was that Taiwan released economic data at all and on time, a sign of its democratic openness.

In contrast, China decided to delay the release of the latest figures for its economy – the world’s second largest – on Monday. The official silence was perhaps to prevent any disappointing numbers from embarrassing Xi Jinping this week as he secures a third term as Communist Party leader during a gathering of the party’s elite. By many estimates, China’s gross domestic product per capita could be falling while Taiwan’s is expected to become the highest in East Asia this year.

Taiwan still struggles as a young democracy – its first direct presidential election was 24 years ago. Yet its people have strongly embraced the need for transparency and integrity in government, starting with economic data. In contrast, Mr. Xi has “reversed course from his predecessors’ emphasis on humility and openness to focus on national pride and self-sufficiency,” as The Wall Street Journal puts it.

Official secrecy has been rising under Mr. Xi’s decadelong time in power. A new law heavily restricts release of government data while academic exchanges with other countries have been sharply curtailed. Party censors are more diligent in scrubbing social media of any government leaks.

Taiwan, meanwhile, has become one of Asia’s most open societies – despite China’s attempts to spread disinformation among the Taiwanese. In an Oct. 10 speech, President Tsai Ing-wen said her government will “respond with a more transparent and democratic approach” against Beijing’s “attempts at sabotage.”

Because of trust in Taiwan’s business environment, the country remains the world leader in the manufacturing of advanced computer chips. It also beats out China in global indexes on economic competitiveness, online freedom, and ease of doing business. Highly dependent on imports of Taiwan’s semiconductors for its high-tech industries, China may be hesitant to invade the island.

That so-called silicon shield relies on Taiwan’s democratic values, such as its openness to alternative politicians every election and honesty in economic information. This open-mindedness also encourages creativity in science and technology. The country ranks high in “innovation capability,” according to the Global Competitiveness Report.

A high level of confidence in government helped Taiwan cope well during the pandemic. “Because we trust the people a lot, sometimes the people trust back,” one official told the BBC.

Openness has served Taiwan. In July, the United States began talks for a free trade agreement with the island. Despite attempts by China to isolate its neighbor, Taiwan has more than 60 trading partners.

As a model of governance, Taiwan surpasses the one touted this week by China’s ruling party. The world just needs to notice which country is releasing economic data, good or bad, and on time.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Our divine right to mental health

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 2 Min. )

Sometimes mental well-being can seem subject to forces beyond our control. But we all have a God-given ability to find lasting freedom from whatever would cloud our stability, joy, and peace of mind.

Our divine right to mental health

At times, mental health and well-being can seem vulnerable. But there’s a powerful antidote to mental health issues of any kind: the recognition that we are all children of God, created to reflect the one divine Mind. This Mind is eternal, unchanging, pure good. Praying from the standpoint of these spiritual facts helps bring to light, in tangible ways, the stability, joy, and wholeness that the Divine has bestowed on all of us.

We’ve compiled some pieces from The Christian Science Publishing Society’s archives that highlight the healing power of prayer in tackling mental health issues, offering inspiration for your prayers on this topic – whether you’re struggling with your own mental well-being, caring for a loved one, or praying for our fellow men and women more generally.

The author of “Mental stability – possible for everyone” shares inspiration that brought healing and peace of mind after she started to experience frightening symptoms of a mental breakdown similar to what other members of her family had faced.

In “Mental health that’s permanent and secure,” the author shares how she found complete and permanent freedom from mental darkness and self-destructive behaviors as she learned about God as divine Mind.

“How can I think about ... self-harm?” is a podcast* in which two individuals share heartfelt stories illustrating how healing of the impulse to self-harm is possible.

“Freedom from severe anxiety and depression” conveys a woman’s journey to complete healing after decades of mental health difficulties.

In “Mental health: a new view,” a woman shares how seeing goodness as innate in every individual as God’s image consistently informed her work in a variety of positions throughout her career – whether at a psychiatric center or a prison – and can help us more effectively address and heal mental health issues.

“Support for teens’ mental health” explores how we can prayerfully stand up for all young people’s right to feel safe and confident and to know they’re not alone in thinking through tough issues.

*This podcast is from a five-part Sentinel Watch podcast series running through the month of October that offers a spiritual and healing perspective on mental health issues. You can check out the series here on JSH-Online.com.

A message of love

A chance to soar

A look ahead

Thanks for joining us today. Tomorrow we’ll return with a fresh array of stories, including a look at the legacy of John Gould’s essays in The Christian Science Monitor.