- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- ‘Where’s the middle?’ In closely divided US, a country waits.

- Cooperative rivals: Biden seeks novel relationship with China

- In Egypt and beyond, a climate crisis as close as one’s water tap

- Farming fog for water? Canary Islands tap a new reservoir.

- Spielberg offers a portrait of his youth in ‘The Fabelmans’

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Decades after fleeing Iran, a family is riveted by protests

Around the world, countless members of Iran’s diaspora have been riveted by the protests that erupted in September after 22-year-old Mahsa Amini, detained in Tehran for wearing her head covering too loosely, died in custody. Razieh Javaheri is one of them. She and her husband, Tanin Persa, who fled Iran in the early 1980s, are watching news “24/7.” These protests, she says, of those they’ve observed over decades, feel different.

“In past protests, people wanted to make the system better, to promote reform,” says Mrs. Javaheri, a retired molecular biologist who has lived in the United States for about four decades. Now, “young people are saying enough; we don’t want you [the government] anymore.”

She and Mr. Persa have watched as Iranian women, men standing with them, have demanded more rights, burning headscarves, going on strike, tearing down gender-separation barriers at universities, staging sit-ins. Hundreds of people have been killed, rights groups say; on Tuesday, parliament supported the death penalty for thousands of detained protesters.

Yet protests persist, nearly two months on, and women – the frequent target of so-called morality police under the hard-line Raisi government – have remained in the forefront.

That’s inspired Mrs. Javaheri. She and her husband have regularly joined thousands of people marching in solidarity on the National Mall. It’s inspired her daughter as well, for whom a sense of distance from events in the country she last saw at age 5 began to dissipate as she too joined in. “If you attend these demonstrations, you will see that ... they’re marching for a democratic system. This is what people want,” she says.

“I’m so humbled by how brave [Iran’s protesters] are, and how much we take for granted here [in the U.S.]” And, she adds, “I’m not surprised – my parents told me about Iranian women’s outspokenness” and education.

Mrs. Javaheri says fellow marchers on the mall aim to “remain as one,” even as many likely have different hopes for the future. To her, the uprising is about something much deeper than issues like the high unemployment and limited opportunity that cause many young Iranians to despair. The protest “is not because of housing or money,” she says. “It’s because of freedom.”

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

‘Where’s the middle?’ In closely divided US, a country waits.

Democrats overcame historical trends and poor economic conditions in a number of key races, though the full picture is still emerging. Voters in particular seemed to reject statewide candidates who denied the 2020 results.

-

Story Hinckley Staff writer

-

Patrik Jonsson Staff writer

-

Sophie Hills Staff writer

-

Noah Robertson Staff writer

Why did the predicted red wave turn into a ripple?

Some key races in the 2022 midterm elections have not yet been decided, but the vote’s bottom line seems clear: Republicans did not do as well as they had hoped, and Democrats did better than expected.

If there is a message from the razor-thin midterms, it could be: American voters care about democracy. Candidates who echoed former President Donald Trump’s false claims about the 2020 election lost every governor’s race except in Arizona, which remained too close to call Wednesday. And polls pointed to weak Republican candidates in some important races.

“Even though there is a lot of latent dissatisfaction about the way the country is going and the state of the economy and the performance of the president, there just isn’t an enthusiasm for the alternative,” says David Hopkins, a political scientist at Boston College.

As of this writing, control of the Senate was in the balance, and could remain so until a December runoff in Georgia. The GOP appeared to be in a better position to gain a majority in the House.

Voters interviewed in three key states – Pennsylvania, Georgia, and Arizona – were not necessarily delighted with their choices.

“They both seem so extreme. Where’s the middle?” asked Helene Dunn, a Pennsylvania voter.

‘Where’s the middle?’ In closely divided US, a country waits.

Why did the predicted red wave lap onto the beach as a relative ripple?

Some key races in the 2022 midterm elections have not yet been decided, but the vote’s bottom line seems clear: Republicans did not do as well as they hoped. Democrats showed unexpected strength, given the political fundamentals of President Joe Biden’s unpopularity and voters’ widespread economic concerns.

If there is a message from the razor-thin midterms, it could be: American voters care about democracy. Candidates who echoed former President Donald Trump’s false claims about the 2020 election lost every governor’s race except in Arizona, which remained too close to call Wednesday.

Other immediate takeaways: Candidate quality still matters, with polls pointing to weak Republican candidates in some important Senate and gubernatorial races. And in a post-Roe America, abortion is a driver at the ballot, with voters in five states – Michigan, Vermont, Kentucky, Montana, and California – all voting in favor of abortion rights.

“Even though there is a lot of latent dissatisfaction about the way the country is going and the state of the economy and the performance of the president, there just isn’t an enthusiasm for the alternative,” says David Hopkins, a political scientist at Boston College.

As of this writing, control of both houses of Congress remained undetermined – although the GOP appeared to be in a better position to gain a majority in the House of Representatives. That could presage two years of bitter conflict, with a Republican House launching a wide range of investigations into Biden administration activities.

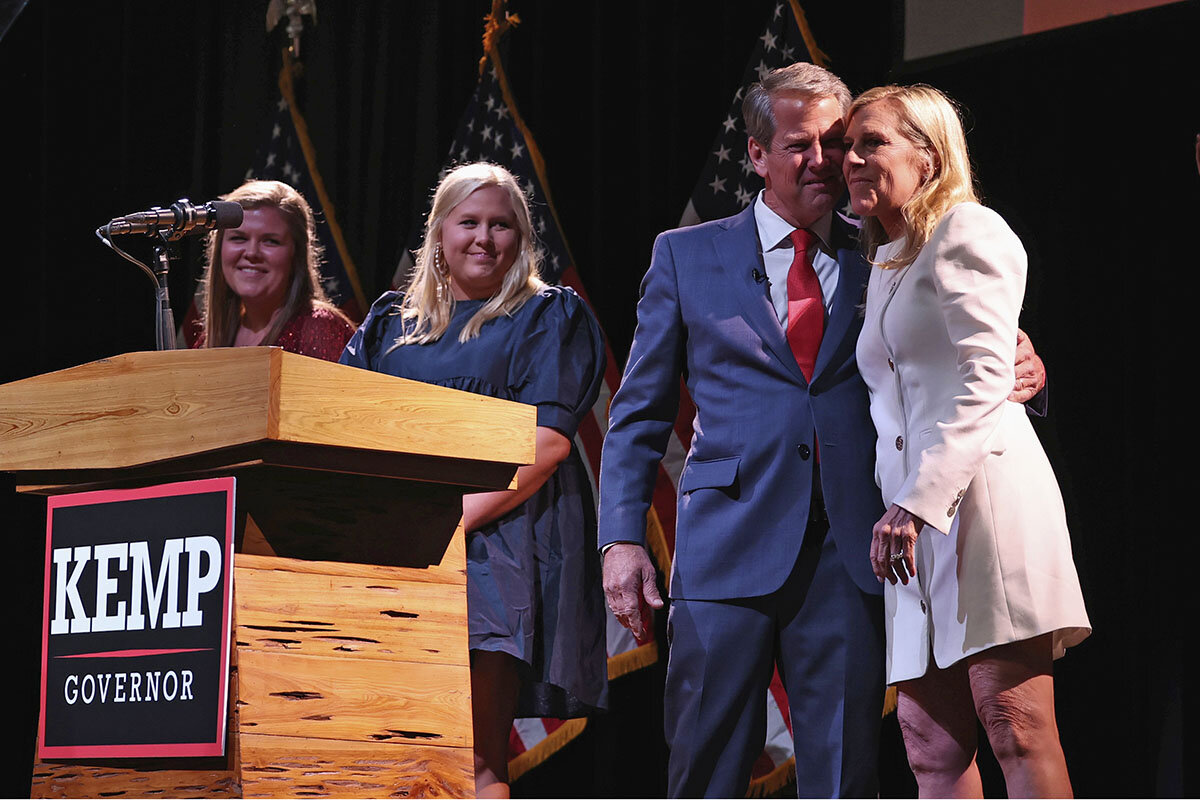

Control of the Senate is also unclear, and may remain so until a Dec. 6 runoff in Georgia between Democratic incumbent Sen. Raphael Warnock and GOP challenger Herschel Walker. Mr. Walker, a former football star endorsed by former President Trump, ran well behind other Republicans in the state, especially Gov. Brian Kemp, who handily won reelection. Other weak Trump-endorsed candidates may have cost the GOP Senate seats in Pennsylvania and New Hampshire.

Meanwhile, suburban House seats outside Philadelphia, Chicago, Atlanta, and other cities that used to be solid red but turned purple during the Trump presidency went for the Democrats on Tuesday.

It was not a good election for Mr. Trump, and his grip on the party may have been weakened, says Gary Jacobson, emeritus professor of political science at the University of California, San Diego.

“He’s the greatest mobilizer the Democrats have,” says Professor Jacobson.

Pennsylvania swings blue

In Pennsylvania, now one of America’s most contested battleground states, Mr. Trump’s preferred candidates did poorly. Trump-endorsed television personality Dr. Mehmet Oz lost a Senate race to Lt. Gov. John Fetterman. The former president’s gubernatorial endorsee, Doug Mastriano, who has denied President Biden was duly elected and who was present at the Jan. 6 insurrection at the U.S. Capitol, lost to Attorney General Josh Shapiro.

For some Pennsylvania voters, Mr. Trump’s endorsement was a negative.

Tom McDonald, a retired high school teacher interviewed outside a polling place on the Haverford College campus, says that he formerly registered as a Republican and often voted split tickets. But now he is a registered Democrat, and “the fact that the Republican Party has moved off the rails to the right” has pushed his vote to the left.

This year he voted straight Democratic, and says the issues he was most motivated by include protecting voting and abortion rights.

Meanwhile, Helene Dunn, who works for a local water authority, voted a straight Republican ticket.

Standing outside Central Bucks South High School in Warrington, Pennsylvania, Ms. Dunn says, “I am horrified that with the worst economy, an absolutely frightening border crisis, and crime through the roof, the only thing people care about is abortion.”

That does not mean Ms. Dunn was satisfied with her choices. She says they were the worst she’s ever seen, on both sides.

“They both seem so extreme. Where’s the middle?” she says.

Bourne Ruthrauff, a lawyer from Bryn Mawr, Pennsylvania, also voted Republican – except he did not vote for governor or lieutenant governor.

Recent presidents have all overstepped their power with executive orders, says Mr. Ruthrauff. We need a “responsible” Congress, he adds.

“The Republicans have to put Mr. Trump in the rearview mirror, and that goes back to the rule of law,” he says.

The view from Georgia’s Liberty County

Georgia could be the state on which control of the Senate will turn. Democratic Senator Warnock had a slight lead over GOP challenger Mr. Walker, but did not reach 50% of votes cast. Under state law that means the pair will face off again in a runoff, set for Dec. 6.

But not every part of the state may be hotly anticipating that coming choice.

Georgia’s Liberty County is a largely rural area south of Savannah. Divided equally between Black and white residents, it is home to the massive Fort Stewart Army base, the largest U.S. military installation by land mass east of the Mississippi River. It leans blue for the most part, though in past years it went for Ronald Reagan and George H.W. Bush.

Interviewed outside their polling place, Natalia and Larry Carmichael, both Army combat veterans, say Liberty County represents a rural outpost struggling to do right by its citizens. Mr. Carmichael bemoans how there’s no shade on the few basketball courts available for young players.

“Politicians say what they want you to hear, and then they go and do whatever they’re going to do,” he says. “That’s both parties.”

Ms. Carmichael says she was no fan of Mr. Trump, but he did catch her attention with how he tried to remind Americans of the nation’s inherent greatness.

“We have to regain some of the values that we’ve lost. We have to be a place where we can be proud of who we are,” she says.

Linda McKnight, a former government employee, does see larger American stakes in her vote. She voted for Democratic candidate Ms. Abrams – who lost to Governor Kemp – because of Ms. Abrams’ work to bolster voting rights.

“She walks the talk,” says Ms. McKnight.

Arizona independents now choose a camp

While much of the midterm vote appears to have proceeded smoothly, it remains possible that charges of voter fraud could roil some states. Arizona is one place where that might happen.

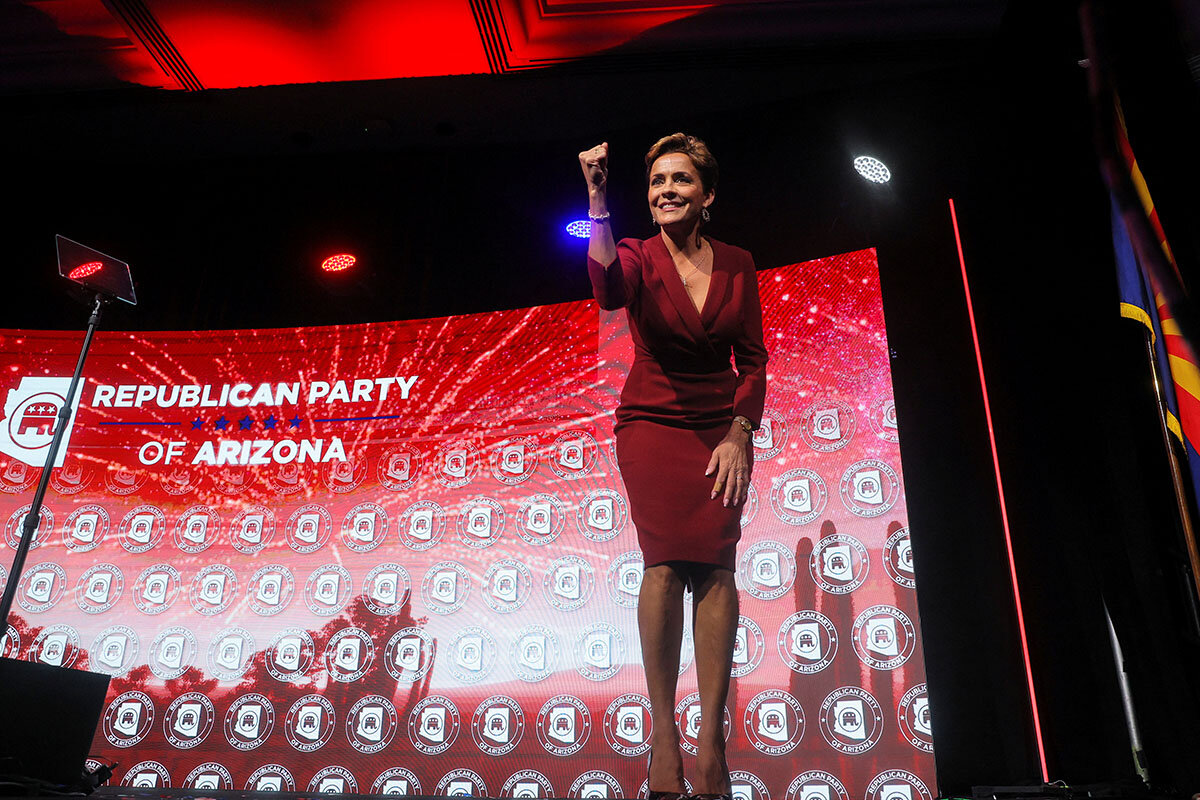

GOP gubernatorial nominee Kari Lake has amplified Mr. Trump’s false claim that he won the 2020 election. She is trailing narrowly in her own election, and has implied she has doubts about the counting.

“We need honest elections and we’re going to bring them to you, Arizona,” Ms. Lake said Tuesday night in a speech to supporters. The midterms are “Groundhog Day” repeating the 2020 alleged widespread fraud, she said.

Arizona is a state where voters who once may have been independents now seem firmly entrenched in partisan views.

James Northcroft is a warehouse worker who lives in Tempe. A former Obama and Clinton voter, he voted for Republicans this year, he says.

“The inflation, the need for law and order, is really bad. Not so much around here, but in New York City criminals get out [of jail] the next day after they do something,” he says in an interview outside his Tempe polling place.

Mr. Northcroft says he only watches the conservative site Newsmax, or late-night Fox News, because everything else is “fake news,” as Mr. Trump continually repeats.

“I think voting is really important – I wish it was 2024 because I want to get Trump or [Florida Gov. Ron] DeSantis back in there. Someone has got to start fighting this radical socialism,” he says.

Carrie Mendoza, an office account manager, has a far different take on the politics of 2022.

“Our democracy really is at stake in this election, and that’s huge,” she says, walking to her car outside the polling place.

A registered Democrat, she says she votes down the middle. In the past she marked a ballot for GOP Sen. John McCain. But she won’t even consider voting for Republicans now.

“And it’s not because the Democrats have it all right. It’s because I can’t take the chance of a Republican winning and have them not believe in our election system, or wanting people to be afraid.”

Ms. Lake may still prevail in her Arizona race. She was one of about 370 Republican candidates in the midterms who questioned the validity of the 2020 election, in one way or another.

At least 168 of those candidates won. Eighty-seven lost, as of Wednesday afternoon.

But many of those who won were running for legislative seats or other offices without direct election responsibilities. Some of the deniers who would have been best positioned to affect election results, such as Mr. Mastriano in Pennsylvania’s gubernatorial race, lost.

Twelve deniers or questioners of the 2020 vote ran for state elections chief, according to CNN fact-checker Daniel Dale. Six lost, including candidates in Michigan, Minnesota, and Vermont. Four won, including candidates in Wyoming and Alabama. Two have yet to be determined.

“We’re in really unusual times in the United States now, and our battles are not normal politics. They’re not about public policy. ... Instead, what the battle is about now is democracy itself,” says Suzanne Mettler, the John L. Senior professor of American institutions at Cornell University.

It’s heartening that many Americans who are worried about democracy turned out to vote on that issue, says Professor Mettler. But many election deniers will be in office as the political clock ticks toward the 2024 presidential election.

“We’re not out of the woods,” she says.

Patterns

Cooperative rivals: Biden seeks novel relationship with China

At his first meeting with Xi Jinping next week, President Joe Biden will be navigating his interest in starting to uncouple the U.S. and Chinese economies without threatening the whole edifice of their trade relationship.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

U.S. President Joe Biden and actress Gwyneth Paltrow would seem to have little in common. But Ms. Paltrow’s description of her separation from her former husband as “conscious uncoupling” must resonate with Mr. Biden as he prepares to meet Chinese leader Xi Jinping for the first time next week.

Ms. Paltrow and her husband sought to avoid too much collateral damage to each other, their family, and friends. The U.S. president is hoping he can recalibrate Washington’s relationship with Beijing – which has long been a major trade partner but which has now emerged as America’s main economic, political, and security rival – while avoiding a messy divorce.

Mr. Biden would like to maintain communications and even cooperation with China in areas of mutual interest, such as climate change, even while the two countries exercise their rivalry. That approach has had mixed results so far.

The trickiest aspect is that an across-the-board uncoupling could do the U.S. economy, and the world, a good deal of damage, especially at a time of global economic uncertainty. The U.S.-China trade relationship is worth $655 billion a year, after all.

That poses the question Mr. Biden must answer: Can the United States step back from this relationship without falling off a cliff?

Cooperative rivals: Biden seeks novel relationship with China

Here’s a phrase I never expected to write: Joe Biden will be spending the next few days channeling his inner Gwyneth Paltrow.

It was Ms. Paltrow who popularized the phrase “conscious uncoupling” to describe the careful unwinding of her 12-year marriage to British rock star Chris Martin, with the aim of avoiding collateral damage to each other, their family, and friends.

But it might well apply now to the U.S. president, who is due to meet Chinese leader Xi Jinping for the first time next week, as Mr. Biden begins the delicate task of recalibrating Washington’s relationship with Beijing at the most consequential summit of his presidency.

The meeting, at the G-20 summit on the Indonesian island of Bali, comes at a critical juncture. After decades of increasingly intertwined trade ties, China has emerged as America’s main economic, political, and security rival.

Mr. Biden will be hoping that despite this rivalry, both sides will recognize that a bitter, chaotic divorce – the geopolitical equivalent of sulking and shouting, slamming doors, and throwing dinner plates – is in neither nation’s interest.

Especially now, as the United States, China, and the world navigate a range of critical issues, such as climate change, Russia’s war on Ukraine, and the prospect of a general economic slowdown.

Since the earliest days of his presidency, Mr. Biden has made clear the political understanding on which he wants to build future ties with Beijing: that while the U.S. sees China as a competitor and rival, the countries should still be able to communicate and, where possible, cooperate on areas of mutual interest.

This approach has had mixed results so far. Washington has not found China ready to engage with it on climate policy. But on the other hand, Beijing has largely refrained from helping Moscow evade Western sanctions.

Meanwhile, an “unconscious uncoupling” has already begun – the result of a range of political and economic factors in both China and the West.

In China, Mr. Xi has sidelined figures associated with the country’s economic reform and opening to the outside world. He is focusing instead on economic self-sufficiency, especially in high-tech areas, and the projection of Chinese power abroad.

He’s also imposed a “zero-COVID” policy with lockdowns and mandatory testing for millions of Chinese citizens across the country. That has contributed to a serious slowdown in China’s economy. It has also upended the supply chains on which major businesses in America and other Western countries have come to rely.

That has been a stark reminder of the degree to which Western economies have come to depend on China. The price that Europe is now paying for its reliance on oil and gas from another autocratic regime, in Moscow, has further highlighted the risks of such an approach.

Some Western companies have been uncoupling on their own, cutting back on planned investment projects in China as a result. Even companies with major manufacturing partnerships may start recalibrating. Apple, for example, has shifted the manufacture of some iPhones to India. A COVID-19 lockdown of its main manufacturing hub in China now threatens to limit handset sales during the holiday season.

Still, unwinding reliance may prove complicated for a number of governments.

Germany’s Chancellor Olaf Scholz faced criticism not only from fellow European Union states, but his own Cabinet and security services, for flying to China last week to meet Mr. Xi. The reason he went: the importance for Germany’s automobile industry of sales in China.

Australia has no doubt about the security challenge Mr. Xi’s China poses for its Asian neighbors: It has decided to base nuclear-capable U.S. bombers on its territory. Still, despite punitive Chinese tariffs on a range of Australian goods, exports to China remain key to its economy.

The conundrum facing Mr. Biden is that both the U.S. and the wider world economy could suffer significantly from an across-the-board uncoupling. Washington is determined to impose stricter national security criteria on its trade with China. How can it do this without threatening the whole edifice of a trade relationship worth $655 billion a year, and thus damaging an already fragile economy?

Mr. Biden recently set new rules barring the sale to China of advanced microchips and chip-making technology. His aim is unequivocal: to frustrate Mr. Xi’s campaign to catch up with, and then outpace, the U.S. in high-tech innovation.

Still, in explaining the new restrictions, Alan Estevez, a senior Commerce Department official, added a dash of Gwyneth Paltrow-like consciousness. The aim was not, he said, to hold back China’s economy, nor to undermine the U.S.-China trade relationship.

At the same time, Mr. Estevez does not appear to foresee a very sophisticated future for the Chinese microchip industry. He had “no problem,” he said, with China retaining “a robust capability to make semiconductors to go into the airbags of cars.”

That is unlikely to impress Xi Jinping.

In Egypt and beyond, a climate crisis as close as one’s water tap

Water scarcity is a growing challenge in much of the world – and notably in the Middle East and North Africa region that is now hosting a global climate summit. One big tension: balancing rural and urban priorities.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 8 Min. )

Amid longer and more frequent droughts, questions that have vexed the Middle East and North Africa for decades are becoming matters of national security: Grow wheat or grow your economy? Water increasingly scorching farms or a thirsty population?

The challenges are prompting a search for fresh solutions, from creating desalination plants to preventing water leakage and evaporation from irrigation canals. At COP27, this year’s global climate action summit in Egypt, the usual headlines about how to curb heat-trapping carbon emissions are joined by a rising focus on how to adapt to climate shifts that are already being felt.

Despite water scarcity, Egypt is one of several Arab states pushing for greater local production of grains – to overcome a burgeoning food crisis.

“We are the ones that feed you,” says Samayni, an Egyptian farmer who had three straight years of no mango production due to intense heat waves and a lack of water.

Mohammed Fahim, of Egypt’s Central Laboratory for Agricultural Climate, says the way forward is “to conserve our limited water resources through advanced water-saving irrigation practices.”

In Egypt and beyond, a climate crisis as close as one’s water tap

As world leaders gather for a summit on global warming some 300 miles away, Nile Valley farmer Samayni says he has little time to think about climate change.

Standing among his date and mango groves, with the Black Pyramid of Dahshur looming above, in an area where people have farmed for millennia, as he sees it he is simply struggling to make more with a formerly abundant resource.

“Forget about climate change, rising temperatures, or the ozone – our main problem here is water,” he says, gesturing to a bone-dry irrigation canal near to his farm. While in previous years Nile water would flow down this channel each day, he and other farmers now get irrigation water once every 20 days as part of new allocation rotation.

“We are struggling to continue with less and less water, and our ability to feed ourselves as a people is in danger.”

Here in the Middle East, home to the most water-stressed countries on Earth, conserving and maximizing water in these arid lines has been a careful balancing act since antiquity.

Yet as longer and more frequent droughts, combined with higher temperatures and delayed and reduced rainfall, push many Middle East and North African states into water crises, questions that have vexed the region for decades are becoming matters of national security: Grow wheat or grow your economy? Water increasingly scorching farms or a thirsty population?

The challenges – which scientists widely attribute to climate change as well as to rising human consumption – are prompting a search for fresh solutions, from desalination plants to preventing water-source leakage and evaporation. And the concern about water supply, though varying from one region to the next, is increasingly global in scale – a fact visible in the agenda of COP27, this year’s global climate action summit in Sharm el-Sheikh, Egypt. The summit’s usual headlines about how to curb heat-trapping carbon emissions are joined by a rising focus on how to adapt to climate shifts that are already being seen and felt.

At the conference, Egypt helped announce the Sharm El-Sheikh Adaptation Agenda which, among other goals, calls for “smart, efficient and robust water systems” with a reduction of water loss through leakage and sustainable irrigation systems to be implemented across 20% of global croplands by 2030 “to preserve water availability whilst supporting yield growth.”

In the Middle East, a balancing act

Nowhere is the pressure to adapt more urgent than in Egypt and other nations in this region, as debt-burdened countries scramble to balance development needs with feeding themselves amid Ukraine war-induced grain shortages.

With over-pumping and evaporation of exposed irrigation canals and dams due to rising temperatures, Egypt now faces a water deficit of 21 billion cubic meters per year, according to the Egyptian government.

Here, 560 cubic meters (150,000 gallons) of water are available per person annually, less than a third of the amount available 50 years ago, according to Egyptian government data. Anything below 1,000 cubic meters per person is defined by the United Nations as water-scarce.

Jordan and Tunisia, which depend solely on rainwater-fed dams and underground water, are facing droughts. Tunisia has less than 400 cubic of meters of water per person annually, and Jordan, less than 90 cubic meters of water per person, making it the second most water-poor country on Earth.

Last month, leading religious authorities in both countries called for national prayers for rain. Jordan received its first full rain of the year on Tuesday.

Scarcity has sparked a debate on where and how water is spent.

In Egypt, 85% of water is reserved for agricultural irrigation, leaving only 15% of water going to urban use, industry, and tourism in the Arab world’s most populous and fastest-growing country.

Egypt is one of several Arab states that are pushing for greater production of local grains – to overcome a burgeoning food crisis and reliance on Ukraine and Russia – even as their water sources dry up.

Farmer Samayni, who had three straight years of no mango production due to intense heat waves and a lack of water, says the priorities are clear.

“You need to put agriculture first. Agriculture should steer the country. We are the ones that feed you, we are the ones that keep the nation together,” he says, “If you don’t water us, we will starve.”

Yet the priority on agriculture has meant more water shortages for villages and cities.

“You think twice about taking a shower”

In Jordan, when a town expands, authorities are often unable or unwilling to extend government-provided water, leaving new homes to rely on private wells.

Abu Tareq Al Moqdadi, imam of a local mosque next to a cave locals believe Jesus visited, and his family of seven have relied solely on trucked-in water at $50 to $80 a month since they built a home on his father’s land at the outskirts of the northern Jordanian village of Bayt Idis seven years ago.

Despite government promises and a U.N.-supported program to expand the network to reach this fast-growing neighborhood, they, like many in northern Jordan, remain without water.

“You think twice about taking a shower, doing laundry, how you do dishes,” Mr. Al Moqdadi says. “Water has become the largest cost and biggest challenge in our daily lives. It brings everything to a halt.”

In Dhiban, an agricultural town in central Jordan, 50 miles south of Amman, the 35 million cubic meter Mujib reservoir has been dry since April.

“You are constantly under climate stress because you don’t know where the next cup will come from,” says Mohammed Hameida, who works with local youths in Dhiban. He and many residents now rely on private wells. “I am afraid for my children. How will they live?”

Back in Egypt, at a small filtration plant in Dahshur, residents line up to fill large plastic containers with filtered groundwater.

With the limited Nile water and reduced water quality due to agricultural runoff, what was once an anomaly and a luxury – filtered water – has become the main source for household use in this village and many others across Egypt in recent years.

Yet these underground resources are projected to be depleted far faster than they regenerate, water experts say.

“The main principle promoted by water advocates for decades is to stop allocating water for agriculture. When you do that you can free it up for other economic sectors that have more value – whether tourism, industry, even financial services,” says Guy Jobbins, a research associate at the Climate and Sustainability Programme at ODI in London and Middle East water policy expert.

“The problem is, in these dry and hot countries water is needed for agriculture which still employs a lot of people,” Dr. Jobbins says, “If you take water out of farmlands and reallocate for cities, then all of a sudden you have real problems for rural poverty. And then there is the issue of food security.”

A rising focus on solutions

For Egypt, one answer to its water woes is an ongoing national project to line irrigation channels with cement to reduce water loss and improve water quality. Another pilot project is completely covering water canals in the Upper Nile Delta to prevent evaporation.

Since 2020, Egypt has lined more than 4,500 km (2,800 miles) of irrigation channels, with plans to line a total of 20,000 km by mid-2024, according to its Irrigation Ministry, a project projected to save up to 5 billion cubic meters in water loss annually due to seepage.

Dozens of cranes and crews dig up mud along canals running parallel to the Nile south of Cairo, expanding the project.

“The only way forward are programs to boost agricultural production on existing lands with the same amount of water and to conserve our limited water resources through advanced water-saving irrigation practices,” says Mohammed Fahim, of Egypt’s Central Laboratory for Agricultural Climate.

“But unfortunately, these measures are very costly and require advanced technology and funds. As of now, Egypt and other Arab states are relying solely on their national budgets, which cannot possibly fund these projects on their own.”

Egypt, which is holding the presidency of COP27 as host, is set to announce a water initiative next week, as the global climate conference continues.

Jordan, meanwhile, is exploring a project to build a desalination plant on its sole sea port of Aqaba to pump water 200 miles uphill to the capital Amman, where half of its citizens live. That would add 250 million to 300 million cubic meters of desalinated water a year, and would cover about half its projected annual deficit.

On Tuesday, Jordan and Israel moved closer toward a water-for-solar energy deal. Under the agreement, brokered by the UAE last year and signed by the two countries this week, Israel will provide Jordan with 200 million cubic meters of desalinated water in return for 600 megawatts of solar-generated electricity annually.

Yet Jordan, Tunisia, and Egypt are all burdened with billions in international debt and struggle to keep pace with growing demand on overstressed government services.

“The developed countries whose industrial development caused the climate change we are living with must pay reparations so that other nations can survive and adapt,” says Mr. Fahim, the Egyptian climate expert, “because the climate crisis will not stay in the borders of one country.”

As the sun sets over palm-shaded farms in the Al Qalyubia governorate north of Cairo, tenant farmers Mohamed Awadh and his wife Soumaya have plenty of worries – notably the rising costs of fertilizer and salts.

“God’s blessings,” Soumaya says over the roar of the diesel pump. “That will dictate whether we have a good harvest or not.”

But they express gratitude and satisfaction over the cleaner water provided by the Egyptian canal project. And it is making a visible difference, seen as they flood their acre plot of mint and cauliflower with Nile water pumped from a newly paved canal a few feet away.

Farming fog for water? Canary Islands tap a new reservoir.

A lack of usable water is becoming a problem in areas where it wasn’t before. But in the Canary Islands, locals are thinking creatively – and finding that fog can make up for some shortfalls.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Since 2018, when rain is in short supply in the summer months, Jonay González Pérez and Sara Rodríguez Dorta have relied solely on fog to water their 3.7 acres of farmland.

On a good day, the couple’s wall of collectors – vertical U-shaped nets cemented into the ground by metal poles – can harvest 475 gallons of water from the fog. The suspended fog droplets fall from the nets and flow through 220 yards of black tubing into a 95,000-gallon storage tank that resembles a giant waterbed.

“We’re in an area where the local authority does not supply water for agricultural use,” says Mr. González Pérez. “So without the fog collectors, our farm simply would not exist.”

As the Canary Islands and regions around the world look to combat the effects of climate change, fog collecting is becoming an increasingly viable technology for communities facing soil erosion and water supply challenges.

“Fundamentally, we depend on our groundwater in the Canary Islands, and water is always scarce,” says María Victoria Marzol Jaén, a retired climate scientist. “Fog water alone can’t supply this. ... But for rural zones, where water consumption is much lower, [fog collecting] is more than just helpful. It can be the solution to water problems.”

Farming fog for water? Canary Islands tap a new reservoir.

On a clear day, the tiny hamlet of La Vega, stacked up high on the hillsides of northern Tenerife, offers spectacular views of the rugged Atlantic coast. But this afternoon, the thick mist spiraling through Jonay González Pérez and Sara Rodríguez Dorta’s farmland sets an eerie Alfred Hitchcock filmlike scene.

Nearly ripe for fog harvesting.

“There’s almost enough fog to start collecting it,” says Mr. González Pérez, trudging through ankle-high grass in rubber galoshes as he snaps dead leaves off an artichoke plant. “But we need to wait a little longer, until the fog is at the same level as the catcher.”

Since 2018, Mr. González Pérez and his wife have relied solely on fog collecting to water their 3.7 acres of farmland – which includes lemon and plum trees, artichoke plants, and 50 chickens – when rain is in short supply in the summer months.

On a good day, the couple’s 435-yard-long wall of collectors – vertical U-shaped nets cemented into the ground by metal poles – can harvest 475 gallons of water. The suspended fog droplets fall from the nets and flow through 220 yards of black tubing, which snake down the back of their property into a 95,000-gallon storage tank that resembles a giant waterbed.

Their system – which the couple built with their bare hands over the course of a year – was entirely paid for through government subsidies, after they won a local award for the best initiative in rural farming.

But this isn’t just a pet project for small-scale farmers. In 2020, the European Commission partnered with the local government in neighboring Gran Canaria to fund the Life Nieblas fog-collecting project, which aims to reforest areas decimated by drought or forest fire. Harvested fog water meets the World Health Organization’s standards on drinking water safety and has provided isolated communities with a much needed resource for decades.

As the Canary Islands and regions around the world look to combat the effects of climate change, fog collecting is becoming an increasingly viable technology for communities facing soil erosion and water supply challenges.

“Fundamentally, we depend on our groundwater in the Canary Islands and water is always scarce,” says María Victoria Marzol Jaén, a retired climate scientist at the University of La Laguna on Tenerife and one of the pioneering researchers into fog collecting in the Canary Islands in the 1990s.

“Fog water alone can’t supply this, but it can be useful for reforestation purposes, like in the case of forest fires. But for rural zones, where water consumption is much lower, [fog collecting] is more than just helpful. It can be the solution to water problems.”

“We have a natural resource right in front of us”

The first documented experiments into fog as an alternative water resource can be traced to South Africa in the early 1900s. In 1963, Chilean physicist Carlos Espinosa’s invention of “mist traps” were patented and offered to UNESCO for free use around the world. Since then, researchers have made significant developments into the green technology, and research sites can be found in Chile, Peru, South Africa, Morocco, China, the United States, and Spain’s Canary Islands.

Due to their high altitudes and abundance of fog – in addition to their unique water supply challenges – the Canary Islands have remained at the center of fog harvesting research, particularly Tenerife and Gran Canaria.

Though there are slight variations, most fog harvesting systems follow a similar model to the one built by Mr. González Pérez and his wife, involving two or more nets that catch the fog droplets, which then drip into a waiting container.

Apart from the initial materials and building costs, fog collection is a low-energy operation, whose structures, like netting, can blend more seamlessly into natural environments than wind turbines or solar panels. Upkeep involves merely clearing away overgrown plants and cleaning the filters.

“Fog collecting doesn’t consume any energy and doesn’t affect any other natural resources,” says Ricardo Gil, a technical architect in Tenerife who runs the Nieblagua company. He has installed around 100 fog collectors across the Canary Islands, mainland Spain, and Portugal. “It also takes the pressure off extracting water from aquifers or desalinating ocean water.”

Each of Nieblagua’s catchers can withstand winds of up to 62 mph, and use four sheets of netting to collect up to 8,000 gallons of water per year in optimum conditions. In several of the Canary Islands, which benefit from around five hours of fog per day, this translates to almost one person’s entire water needs – the World Health Organization estimates that between 50 to 100 liters (13 to 26 gallons) of water is necessary for one person’s basic daily usage.

For thirsty, drought-stricken regions, that can mean the difference between survival and desertification – especially when multiple catchers are set up in one area. In Arafo on Tenerife, 12 of Nieblagua catchers provide an estimated 26,000 gallons annually to new almond tree plantations.

“It’s not a fantasy. We’re using up our natural resources all around the world,” says Mr. Gil during a coffee break in La Laguna. “Here we have a natural resource right in front of us. We need to take advantage of it.”

“Very useful on a small scale”

Fog is often referred to as “horizontal rain,” but collecting it has its limitations and relies on certain conditions to function. There has to be enough wind to push the droplets through the nets, but not too much that it knocks the whole structure down. And, of course, there has to be enough fog.

In recent years, weather patterns have become more erratic due to climate change, making the quantity and quality of periods of fog more unpredictable and, thus, more unreliable when it comes to harvesting efforts.

“Fog collecting can only be done in very specific conditions. Mountain ranges are best,” says Axel Ritter Rodríguez, an agroforestry engineering professor at the University of La Laguna and a researcher with the Life Nieblas project. “I don’t think it’s the remedy to all of our water problems, but it’s very useful on a small scale.”

The Life Nieblas project has taken this scaled-down approach, but with a broader vision for the future. Project members have installed 15 of Nieblagua’s catchers in Gran Canaria with the goal of harvesting 57,000 gallons of fog water in a year to repopulate 86 acres of the Doramas Forest with 20,000 laurel trees. The area is at high risk of desertification due to forest fires.

Researchers at Life Nieblas are also developing a separate system that resembles a wind tunnel “to contribute to our fog collection knowledge,” says Dr. Ritter Rodríguez.

As the Canary Islands and the Spanish peninsula look forward, they can expect more irregular and intense periods of rain, in addition to an increase in extreme weather events such as heat waves and storms, says Jorge Olcina Cantos, a geographer at the University of Alicante. “Temperature-wise, it’s going to become less comfortable,” he says.

That has made new, energy-efficient technologies ever more important when it comes to finding water solutions. Research is also continuing into dew collection, which uses a similar system of catching condensation via horizontal nets.

The overarching goal is to stay one step ahead of the game, which means anticipating water and soil needs before they become a problem. Mr. González Pérez and Ms. Rodríguez Dorta knew that when they first got started as young farmers five years ago. Even though their soil is meant for growing apple and pear trees, they decided to plant lemon trees instead, which benefit from a more arid climate.

“We spent about a year thinking and planning this farm. When we bought the land, there had just been forest fires 100 meters [109 yards] away that had destroyed the area,” says Mr. González Pérez. “We could already see that climate change was going to affect things going forward. ... We’re in an area where the local authority does not supply water for agricultural use. So without the fog collectors, our farm simply would not exist.”

Film

Spielberg offers a portrait of his youth in ‘The Fabelmans’

With his semi-autobiographical film, “The Fabelmans,” director Steven Spielberg depicts an early life filled with turbulence and – through his passion for moviemaking – resilience.

-

By Peter Rainer Contributor

Spielberg offers a portrait of his youth in ‘The Fabelmans’

Steven Spielberg, arguably the most commercially successful filmmaker of all time, has made a semi-successful, semi-autobiographical movie about how it all began.

“The Fabelmans” begins in 1952, when little Sammy Fabelman’s parents take him to his first movie – Cecil B. DeMille’s “The Greatest Show on Earth.” We follow his progression from wide-eyed tyke to teenage wunderkind. (As a boy, he is played by Mateo Zoryon Francis-DeFord and, later, by Gabriel LaBelle). But the film is almost as much a portrait of his knockabout family as it is of Sammy. The loudest, if not the greatest, show on Earth is happening right in his own home.

Or, to be precise, his own homes. Sammy’s electrical engineer father, Burt (Paul Dano), moves his family from New Jersey to Phoenix to Northern California, and the dislocations take their toll on everybody. His wife, Mitzi (Michelle Williams), a classical pianist who put aside her musical ambitions to raise Sammy and his three sisters, is particularly affected. She comes across as a free spirit whose wings have been clipped.

By all rights, “The Fabelmans” should register as Spielberg’s most “personal” movie. (He co-wrote the script with Tony Kushner.) Whereas many of his other films, notably “E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial” and “Close Encounters of the Third Kind,” touch on wayward or absent fathers, his new film barrels right into that material. And yet, Spielberg is such a supersleek craftsman that what might have been intended as a deep dive instead comes across for the most part as a sprightly gloss.

At his best, Spielberg is a great entertainer because his showmanship, without the slightest pandering, exceeds and exalts his audience’s expectations. Here that facility functions as something of a detriment. Compared with James Gray’s recent “Armageddon Time,” which also deals with a Jewish boy’s coming-of-age amid a raucous household, Spielberg’s film strikes fewer somber chords. His showmanship operates as a safety net.

There are still pleasures to be had watching him chart, in the guise of Sammy, his own burgeoning love of moviemaking.

What most impresses Sammy about that DeMille film is its massive train wreck sequence, which he re-creates with a toy train set in his basement and then films with a home movie camera. He enlists his sisters as actors in his dinky horror flicks, wrapping the girls in toilet paper so they look like mummies. Later, as a Boy Scout, he casts his buddies in improvised Westerns and war movies. (Many of these films are re-creations of actual early Spielberg opuses.)

But Spielberg aims to do more than just show Sammy’s wonder-boy proficiency. He also wants us to regard the movie camera both as a truth-detector – Sammy accidentally films his mother dallying with Bennie (Seth Rogen), the family’s close friend – and as a portal into the beauty of life itself. For Sammy, movies act as a refuge, especially from his bickering parents and, later, from the antisemitic bullies in his California high school. (They call him Bagelman.) The problem is, as smoothly enjoyable as “The Fabelmans” often is, there’s very little movie magic to be had in it. “E.T.,” with its pure delight in the transcendent joys of fantasy, is a more “personal” work.

It’s clear from this film that Spielberg sees himself, as perhaps many of us do, as a composite of one’s parents – in his case, the artist and the engineer. Both, in their way, are dreamers. But, as LaBelle plays him, Sammy seems more of a stand-in for Spielberg than a full-fledged character. And Williams, though she gives it her all, can’t quite make sense of Mitzi, perhaps because Spielberg can’t either. I wondered why we never see any real bitterness in her toward her children for the career she likely sacrificed for them.

The surprise is that, remarkably, despite all these faults, and despite Spielberg’s legendary reputation, “The Fabelmans” never seems self-serving. It’s a humble self-portrait, and the humility is most welcome.

Peter Rainer is the Monitor’s film critic. “The Fabelmans” is rated PG-13 for some strong language, thematic elements, brief violence, and drug use.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

The sheriff of the new West

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

The capital of Ukraine was again under Russian rocket fire last week, but that didn’t deter a visit by a large delegation of the Czech government. “Our support, our help, is all the more important to strengthen Ukraine in its struggle,” Prime Minister Petr Fiala said after the two sides signed several agreements of cooperation.

It was not the first time the Czech Republic has displayed unexpected moral leadership within the European Union on the Ukraine war.

A nation of only 10.5 million people, it was the first to send tanks to Ukraine’s aid. It has welcomed a large number of Ukrainian refugees and provides outsize military support. Its moral voice was perhaps loudest in September when Foreign Minister Jan Lipavský called for the immediate creation of a special international tribunal to punish war crimes in Ukraine.

Ukraine’s struggles and sacrifice “remind us of the values on which Europe stands and falls – freedom, democracy, and respect for the individual,” the Czech foreign minister wrote on the Novinky news site. That gave him and other top Czech officials the courage to travel to Kyiv despite the risk of Russian rockets.

The sheriff of the new West

The capital of Ukraine was again under Russian rocket fire last week, but that didn’t deter a visit by a large delegation of the Czech government. “Our support, our help, is all the more important to strengthen Ukraine in its struggle,” Prime Minister Petr Fiala said after the two sides signed several agreements of cooperation.

It was not the first time the Czech Republic – a Central European country that doesn’t share a border with Russia – has displayed unexpected moral leadership within the European Union on the Ukraine war.

A nation of only 10.5 million people, it was the first to send tanks to Ukraine’s aid – even though it was highly dependent on Russian gas supplies at the time. It has welcomed a large number of Ukrainian refugees and still provides outsize military support. It has promised economic support to Kyiv through 2025 to help it rebuild. And it led the EU to restrict visas for Russian tourists.

Its moral voice was perhaps loudest in September when Foreign Minister Jan Lipavsky called for the immediate creation of a special international tribunal to punish war crimes in Ukraine. That would include putting Russian President Vladimir Putin on trial for starting a war of aggression. “In the 21st century, such attacks against the civilian population are unthinkable and abhorrent,” Mr. Lipavsky said.

The Czech Republic has taken a tough stance against Moscow in part because of revelations last year that Russian secret agents were behind large explosions at Czech ammunition depots in 2014 that killed two people. The sabotage may have been aimed at preventing the ammunition from being shipped to Ukraine.

In addition, the country took over the rotating EU presidency in July. This raised not only its profile but also that of many other states of the former Soviet empire demanding a stern EU response to Russia. The crisis has helped shift the moral center of the EU away from its traditional leaders, Germany and France, and toward Eastern and Central Europe – with the Czechs out front.

Only three decades away from being under Moscow’s yoke, these countries do not take their independence for granted. Nor do they see membership in the EU as merely an economic benefit. Ukraine’s struggles and sacrifice “remind us of the values on which Europe stands and falls – freedom, democracy, and respect for the individual,” the Czech foreign minister wrote on the Novinky news site. That gave him and other top Czech officials the courage to travel to Kyiv despite the risk of Russian rockets.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Finding home wherever you are

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Ingrid Peschke

When we let God guide our interactions with friends and strangers alike, we’re yielding to the infinite Love that breaks through proverbial walls.

Finding home wherever you are

Today marks World Freedom Day, commemorating the fall of the Berlin Wall on Nov. 9, 1989. This day is especially meaningful to our family, since my husband’s father fled East Berlin with his parents after World War II, escaping Russian occupation.

This decision changed the course of their lives, including allowing them the freedom to practice Christian Science. How could my husband’s parents have foreseen that they would eventually send their son to a college in the United States to study international relations, and that as a young man he would personally experience the peaceful fall of the Berlin Wall?

My husband eventually became a US citizen, and has fully embraced his new homeland. He often refers to a line from the “Christian Science Hymnal” that has stayed with him since he first came to the States: “Pilgrim on earth, home and heaven are within thee” (P.M., No. 278, adapt. © CSBD). This idea is echoed in a passage from the Christian Science textbook: “Pilgrim on earth, thy home is heaven; stranger, thou art the guest of God” (Mary Baker Eddy, “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” p. 254).

Mary Baker Eddy’s discovery of Christian Science came from her inspired study of the Bible, which provides a wealth of insight on the subject of this heavenly home we all share. Christ Jesus’ healing ministry showed us that “we live, and move, and have our being” in God, as the Apostle Paul later said (Acts 17:28). We live in divine Spirit, where God’s love embraces and cares for each one of us impartially, with no consciousness of what language we speak or what we look like. That’s because God knows us not as mortals divided by various human labels, but in our true nature as His spiritual creation.

Through this lens, we all have the divine right, as the children of God, to experience and feel a sense of belonging, equality, and acceptance wherever we are. We can never truly be separated from God, good. From this standpoint we are not strangers to one another, but brothers and sisters in God. And we are capable of knowing and expressing our distinct identity as the very image and expression of infinite Love.

Love, God, transcends borders and communicates in the language of Spirit, reaching hearts and minds with a clarity and affection that surpasses a limited sense of love. Christian Science defines this voice as the Christ, God’s message of truth and love, which is communicated to each of us in a way we can understand. “The ‘still, small voice’ of scientific thought reaches over continent and ocean to the globe’s remotest bound,” Science and Health explains (p. 559). Christ is still very much present to inspire healing solutions to needs of all kinds.

Many years ago when I taught English to second-language learners, one of my high school students tearfully confided to me that she was being bullied by her host family, who seemed only interested in the compensation they received for housing her during her year as an exchange student.

I reached out to the student’s homestay coordinators, and prayed for a solution. As it happened, I had spent a summer in her home country and had been treated with such kindness and hospitality. I knew that these qualities of love and caring stem from divine Love and are therefore not limited by the borders of our family home, culture, language, or familiar surroundings. Rather, we are all created to feel and express these spiritual qualities.

As I prayed, it came to me to invite my student to stay at my home for the weekend, which was a helpful and happy time for all of us. The next week a new homestay family volunteered to house her for the rest of the year. She switched high schools and we lost touch – until just recently, when, after several decades, she found me on social media and thanked me for my help, sharing that she’d never forgotten how much it had meant to her.

This experience serves as a reminder to me that we can all do our part to welcome our neighbors – wherever they’re from, whatever their background may be – by striving to demonstrate more fully the divine Love that breaks through proverbial walls. “My children, our love should not be only words and talk. Our love must be true love. And we should show that love by what we do” (I John 3:18, International Children’s Bible).

A message of love

Remembering a great day for democracy

A look ahead

That’s a wrap for today. Tomorrow, we’ll look more deeply at recent Israeli elections as well as recent U.S. midterms. We’ll also look at the Philippines, where efforts are underway to safeguard firsthand accounts of the country’s martial law period.