- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- ‘It is not feasible.’ High interest rates weigh on young workers.

- Decade under Maduro strains Venezuela’s civil society

- Relay race: How ‘zanjeros’ get Colorado River water to California farms

- Emad Hajjaj challenges ISIS and strongmen – with laughter

- Laws with teeth: Slowing shark loss and new coal mines

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

When banks falter, financial stability takes priority

Silicon Valley Bank wasn’t huge enough to be considered a “systemically important” financial institution that warrants extra scrutiny from regulators.

But we are learning that it was big enough to cause plenty of consternation when it failed.

The key explanation: Financial markets are all about confidence. One bank failure can stir wider questions, notably, “Could my bank be next?” Fear can spread. Risks that in theory shouldn’t be called systemic suddenly get treated that way.

A second large bank failed Sunday: Signature Bank, which at $100 billion in assets is about half the size of Silicon Valley Bank. Some other banks – but at present a relative few – are also facing serious investor and depositor worries.

All this explains why federal officials are doing their utmost to contain any panic.

“Your deposits will be there when you need them,” President Joe Biden told Americans Monday.

On Sunday night, federal regulators took an emergency action to make it so: They said depositors at both shuttered banks will be able to access their funds, even if the amounts are above the $250,000 that qualifies for protection by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp.

The efforts, seen by many economists as necessary, bore immediate fruit: Despite a bumpy ride for some banks, the overall stock market held steady in Monday’s trading.

But the move also comes at a price. It’s true that there’s no direct infusion of taxpayer dollars. But in effect a risky bet by the bank, and by extension its wealthiest depositors, is getting a rescue – in the name of containing spillover to the wider financial system.

“Let me get this straight,” tweeted financial expert Aaron Klein of the Brookings Institution. “The Fed regulates SVB, allows it to blow up its balance sheet with uninsured deposits, buy low interest rate mortgages unhedged ... and then when it fails screams systemic risk and bails out their creditors.”

Yes, that doesn’t seem fair. But it’s also understandable that officials safeguard the system in times of stress. So a key challenge is figuring out how to avert financial panics today without sowing the seeds of irresponsible risk-taking tomorrow. That’s not a new problem. But it has just gained fresh urgency.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

‘It is not feasible.’ High interest rates weigh on young workers.

Persistent inflation has pushed America into an era of rising interest rates that millions of American workers have never experienced before. Consumers have been showing resilience, but also some signs of strain.

-

Sara Lang Staff writer

Since 2021 consumers have been burdened by fast-rising prices for groceries, rent, and more. Now add rising interest rates – boosted by the Federal Reserve in a bid to contain that inflation. Young workers in particular are feeling the pinch, as they experience a spike in borrowing costs unlike anything that has happened in their lifetimes.

It’s visible from mortgages to car loans. Credit card interest rates have risen higher and faster than anyone in Generation Z has ever seen. If the Fed continues to raise interest rates this year, a wider swath of households, young and old alike, could reach a breaking point. So far, however, consumers have proved remarkably resilient, largely because jobs have remained plentiful.

Businesses are affected too: In the past week, two U.S. banks have failed: one of them in part because rising rates caused the value of its long-term credit investments to plunge. That’s sparking questions about whether the Fed will continue raising rates.

“I am not in a very sustainable situation,” says Alex Baker, a Gen Zer in Birmingham, Alabama, despite working as a paralegal at a local law firm and holding down a second job as a barista at Frothy Monkey, an all-day café. He’s looking for a new, higher-paying job.

‘It is not feasible.’ High interest rates weigh on young workers.

For Max Egan, an MBA student at the University of Alabama, the idea of buying a home after graduate school was never his first option. Now, it’s not an option at all.

“It is definitely out of the question right now with interest rates so high,” he says. Even in Kansas City, Missouri, where he’s got a job lined up after graduation, housing costs are high. “They’re higher than I would expect,” Mr. Egan says.

The combination of high inflation and rising interest rates is increasingly straining the resources of U.S. consumers. Young workers in particular are feeling the pinch, and experiencing a spike in borrowing costs unlike anything that has happened in their lifetimes. Everything from car loans to mortgages and home equity lines of credit has become more onerous. Credit card interest rates have risen higher and faster than anyone in Generation Z has ever seen.

If the Federal Reserve continues to raise interest rates to combat inflation, a wider swath of households, young and old alike, could reach a breaking point. Businesses, too, are being affected as rising interest rates make it costlier to borrow for big projects or smaller needs. In the past week, two U.S. banks have failed: one of them in part because rising rates caused the value of its long-term credit investments to plunge.

Those failures, although they were met with prompt federal efforts to prevent a banking panic, are sparking new questions about whether the Fed will continue raising rates and whether banks will make fewer loans in this period of uncertainty. So far, however, consumers have proved remarkably resilient – buoyed by plentiful jobs and by their own efforts to cut expenses and trim back expectations.

“With just regular finances, I would say it’s fine at the current rate,” says Natasha Szulczewski, in Franklin, Tennessee. “If we go up to [buying] a car, it would be pressing it, it’s a little tight. And if we go up one more step with a house, it is not feasible,” says Ms. Szulczewski, a junior Web developer.

The housing market has hit Americans looking to buy their first home especially hard. The double-whammy of rising home prices and then rising mortgage rates has pushed homeownership far beyond their means. Applications for mortgages fell to a 28-year low a couple of weeks ago. And while they have risen a little since then, the normally busy spring buying season could take a hit until rates moderate, Bob Broeksmit, president of the Mortgage Bankers Association, has warned.

Applications for home equity loans are also far below year-ago levels. Many homeowners have used these lines of credit to consolidate their other debt, which is a good move unless it prompts more credit card use, warns Anastasiya Ghosh, a University of Arizona marketing professor. The debt didn’t disappear, but “it creates this false sense that ‘I’m doing well financially.’”

Car loans have proved particularly vexing. In the last three months of 2022, nearly 16% of new-car buyers who financed their vehicle committed to pay $1,000 or more a month for that loan, according to Edmunds, an auto-market research firm. The average now stands at over $700 a month.

“Even if you do make a decent income, that’s still a lot of money just going towards a car,” says Jessica Caldwell, Edmunds’ executive director of Insights. Worse for some consumers, as interest rates have risen, car prices have been dropping as supply chain problems have eased. The result is that the owners of 1 in 6 new vehicles sold last quarter (with a trade-in) now owe more on their cars than the cars themselves are worth.

One big factor behind the increase in debt is young people. Credit card debt overall reached a new record last quarter, surging 18.5% to nearly $1 trillion compared with the same period a year ago. But credit card debt for Generation Z – born in 1997 or later – rose 64% during the same period, according to a report last month by TransUnion. Nearly half of millennials – the next-youngest generation (born 1981 to 1996) – carry credit card balances that are larger than their savings or emergency funds, according to a report released last month by Bankrate. The high cost of living is one reason young people are so indebted.

“I am not in a very sustainable situation,” says Alex Baker, a Gen Zer in Birmingham, Alabama. Despite working as a paralegal at a local law firm and holding down a second job as a barista at Frothy Monkey, an all-day café, “I barely have enough money to put money in savings on top of day-to-day” expenses, he says.

He’s looking for a new job in hopes of a better salary.

So far, young consumers have been able to take on more debt because they’ve enjoyed healthy pay raises since the pandemic. As long as that pay continues to rise at the same rate or faster than their debts, Gen Z and millennials should be able to service their loans, economists say. But various surveys of the economy suggest that last year’s robust pay growth is slowing a bit in 2023.

Employment will also play a key role in determining how many consumers get pushed to the financial breaking point. It’s a key factor in whether debts get repaid. “The best predictor of whether people will pay their bills is their unemployment status,” Michele Raneri, vice president of research and consulting at TransUnion, said in a recent podcast.

Like consumers, the job market has been showing resilience. On Friday, the Labor Department reported that employers added 311,000 jobs in February, more than expected, although unemployment ticked up slightly.

Still, pressures are mounting.

“As a college student, I am on a pretty tight budget that I can’t alter for inflation,” says Amanda Bugos, a senior at the University of Alabama in Tuscaloosa. “Things on the job front have been really hard, too.”

To make ends meet, Ms. Bugos has started tutoring some 15 hours a week. She’s also searching for a full-time job in marketing after graduation. “It doesn’t seem like as many companies are hiring,” she adds. “I’ve been looking for jobs since August and there aren’t a lot of things popping up every week. So it’s been really difficult.”

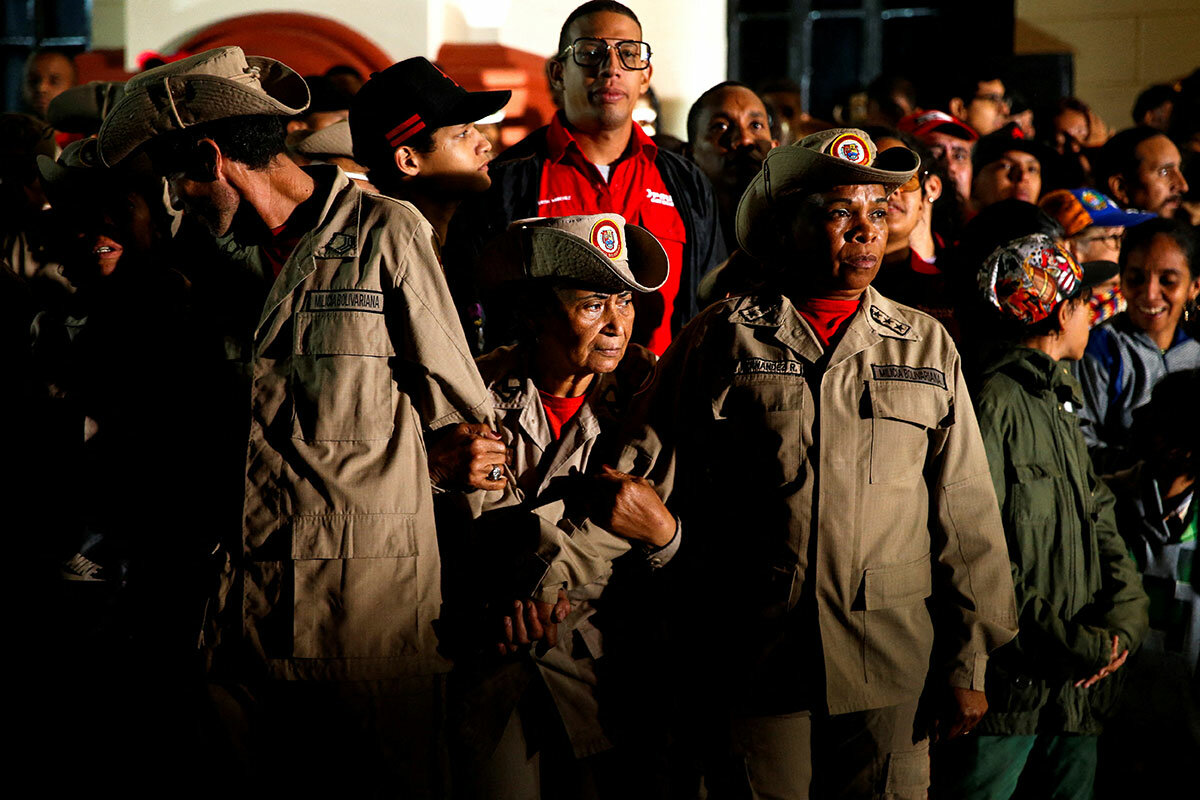

Decade under Maduro strains Venezuela’s civil society

Venezuela is proposing to codify crackdowns on freedom of expression in the lead-up to a presidential vote. Will determination be enough to keep civil society intact?

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

-

By Mie Hoejris Dahl Contributor

After a decade in power, Venezuela’s Nicolás Maduro has proved his staying power – not via the charisma or broad social spending that defined the popularity of his predecessor Hugo Chávez, but by leaning into authoritarian governing tools like repression and censorship.

His approach is on full display as Venezuela pushes a proposal experts say could shatter the remaining vestiges of democratic society by targeting nongovernmental organizations and independent media.

NGOs “are conspiring against the country,” said Diosdado Cabello, vice president of the ruling party.

The timing of the push isn’t surprising to José Ignacio Hernandez, a law professor at the Central University of Venezuela. Through this law, “Maduro is making sure to create an obstacle for the organization of [presidential] primaries,” he says.

“Maduro does not need a special law to silence NGOs. ... He can exercise repression,” whenever he pleases, Mr. Hernandez says. What he seeks is to halt competition in the vote in a way that comes off as legitimate under the law. For that, this crackdown on NGOs – which are “key to accountability” – will be vital, he says.

But members of civil society say they won’t go quietly, providing support for Venezuelans from outside the country and using nontraditional methods to disseminate human rights information.

Decade under Maduro strains Venezuela’s civil society

Ten years ago, Venezuela underwent a seismic shift with the death of President Hugo Chávez. His hand-picked successor, Nicolás Maduro, has successfully held on to power, despite the tanking economy, jaw-dropping inflation, and international sanctions over human rights violations that have defined the past decade in Venezuela.

Mr. Maduro, a former bus driver and union organizer who lacks the charisma of his predecessor, has endured in large part by leaning into repressing and censoring opponents, experts say. Now his government is pushing a proposal that could shutter the remaining vestiges of democratic society in the lead-up to a 2024 presidential vote.

The proposed law, which passed the first of two rounds in the National Assembly in late January, targets nongovernmental organizations and independent media outlets. Despite serious threats, NGOs are pushing back. From exchanging tactics with organizations that have faced similar repression in places like Nicaragua and Cuba, to providing support for Venezuelans from outside the country’s borders, to using nontraditional methods like songs to disseminate vital information to the public, civil society is adapting and sending a message to the Maduro government that they won’t go quietly.

“Authoritarian governments see the presence of scrutiny as a threat to their own existence,” says Marta Valiñas, chair of the United Nations Fact-Finding Mission on Venezuela. In a 2022 U.N. report, her team documented how dissenting voices in Venezuela face arbitrary detentions, threats, physical and verbal aggression, and even torture.

“Civil society is crucial for democratic and civic dialogue,” Ms. Valiñas says, which is why, she believes, Mr. Maduro is once again cracking down.

“Much, much, much worse”

Over the past decade, 1 in 5 Venezuelans have migrated or sought asylum abroad. Political parties have been obliterated, opposition politicians have been imprisoned or expelled from the Andean nation, independent media have been shuttered and harassed, and the judicial system has been gutted, bending to the will of the president and his allies.

After more than a year without formal communication between Venezuela’s opposition and Mr. Maduro’s government, political talks kick-started again late last year. There were a handful of breakthroughs, including the signing a humanitarian agreement that would allow Venezuela access to frozen assets for humanitarian purposes. It also led to the United States easing some sanctions around oil production. The opposition, alongside the U.S. and the European Union, is demanding free and fair 2024 presidential elections; however, a date has not yet been agreed upon.

The proposed Law on Control, Regularization, Operations, and Financing of Non-Governmental and Related Organizations, popularly known as the “anti-NGO law,” could stifle what remains of civil society inside Venezuela. NGOs are relied upon to fill gaps in information the government no longer makes public, to provide medical and humanitarian support as malnutrition grows, and to share research with international watchdogs barred from entering the country.

When Mr. Maduro was tapped as Mr. Chávez’s successor, analysts at the time expected he might keep up “anti-imperialist” rhetoric at home, but become more pragmatic on the international stage.

During his 14 years in office, Mr. Chávez pushed an agenda that focused on lifting the poor through petrodollar-subsidized food and education. When world oil prices plummeted in 2014, Venezuela fell into a seemingly bottomless recession, and Mr. Maduro has coped not by making concessions, but instead by doubling down on an authoritarian approach to governance.

“Oil allowed the Chávez government to co-opt civil society,” says Steven Levitsky, director of the David Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies and author of the book “How Democracies Die.” But, “the degree of repression got much, much, much worse after Chávez’s death.”

The proposed law would prohibit NGOs from carrying out “political activities,” or work that might “threaten national stability.” It would permit the government to demand financial records without cause and limit access to international funding, a lifeline for most NGOs operating in Venezuela.

Diosdado Cabello, vice president of Venezuela’s ruling socialist party, argues the law is necessary for the nation’s future, stating that NGOs “are conspiring against the country, against the Venezuelans. ... They’re instruments of imperialism.”

Critics say the law would make organizations even more vulnerable to harassment, exposing anyone who is critical of Mr. Maduro’s political projects to threats and possibly prison.

Venezuela’s NGOs are “key to accountability,” says José Ignacio Hernandez, professor of administrative law at Universidad Central de Venezuela and visiting fellow at Harvard Growth Lab.

“By approving this law and by boycotting international aid to NGOs, Maduro is making sure to create an obstacle for the organization of the primaries,” he says.

“Maduro does not need a special law to silence NGOs and reduce their accountability, because for that he can exercise repression as has already happened,” he says. From Mr. Hernandez’s perspective, what Mr. Maduro seeks is to halt competition in upcoming votes in a way that comes off as legitimate under the law, and for that, this law will be key.

Trying to adapt

This isn’t the first time the government has attempted to muzzle its critics. There are more than a dozen laws and regulations that restrict civil society in Venezuela, according to Venezuelan NGO Access to Justice. That includes a July 2010 Supreme Court ruling that those receiving international funding could be tried for “treason.”

Currently, the government says it has more than 60 NGOs (out of an estimated 300 to 500) under review, including Provea, a human rights group that has operated for more than 30 years. Provea once worked to defend Mr. Maduro’s labor rights when he was a bus driver in Caracas before entering politics.

Venezuelan NGOs have built resilience in an ever-more-extreme political environment over the past two decades. Civil disobedience and filing international complaints have been key responses, says Rafael Uzcátegui, general coordinator of Provea. Civil society has tapped new approaches to reach the public, leaning into music, poetry, and graphic novels to inform Venezuelans about their human rights.

“We will continue to do the same work that we’ve been doing since the beginning of these threats,” insists Gabriela Buada Blondell, director and founder of Caleidoscopio Humano, a Venezuelan human rights organization. “We will raise awareness, denounce, and communicate to international bodies,” she says, despite real fear. She says the government has attempted to hack into her organization’s website and databases twice this year.

Despite a commitment to keep working, she says she often worries time is running out: “We don’t know if we’re going to be as lucky as we’ve previously been” in fighting repressive laws.

Some working in civil society have coped by leaving Venezuela behind physically – but not their dedication to human rights. Ana Karina García fled Venezuela in 2018 following government persecution for her involvement in youth politics. Her response was to launch Juntos Se Puede in her new home of Colombia. The NGO supports Venezuelan migrants and asylum-seekers in procuring legal documentation, applying for health care, and through community support, education, and job training. At the organization’s Cúcuta location, along the Colombia-Venezuela border, a group of migrants sit in a circle on a recent afternoon, discussing their reasons for fleeing home and hopes for the future. Tear-filled scenes like this one remind Ms. García she made the right decision.

“We realized that there were thousands of Venezuelans in very precarious situations,” she says. “We created a model to take care of migrants, based on our own experiences.”

Venezuelan civil society has looked to NGOs in other repressive countries for inspiration. During the pandemic, Mr. Uzcátegui connected on Zoom to discuss his work and tactics for keeping his doors open with human-rights defenders in Nicaragua and Cuba. The camaraderie eventually moved offline, with a meetup in a third country.

“We’re all convinced,” he says. We need to stay united in order “to have a much stronger impact on the defense of human rights.”

Relay race: How ‘zanjeros’ get Colorado River water to California farms

The Colorado River crisis has heightened calls for conservation. Meet one of the people responsible for delivering – and safeguarding – the river’s liquid gold.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Beginning his workday at 6 a.m. in southeastern California’s Imperial Valley, Jeff Dollente delivers Colorado River water to farms that feed the rest of the United States. He’s a “zanjero,” Spanish for ditch rider.

Strained by overuse and the effects of climate change, the river is facing critical lows, which are unlikely to reverse due to recent heavy rain and snow, experts say.

“That’s what we’re here for – trying to save the water,” Mr. Dollente says.

It’s a high-stakes relay race. From the Imperial Dam, water flows into the major All-American Canal, which feeds into three main canals, and then is directed into a series of lateral canals. Zanjeros usher that water to delivery gates at the edge of farm fields, according to how much has been ordered. At one stop, Mr. Dollente raises another type of gate a mere inch higher to adjust the flow.

“They’re the face of the district to the farmer,” says Ralph Strahm, co-owner of Strahm Farms Inc. in Holtville. “They’re the ones that save the system from breaching if there’s a problem.”

Work is often solitary for the zanjero, but Mr. Dollente is never quite alone. Coyotes pass by, roosters crow. And water sounds like gossip when it rushes through a ditch.

Relay race: How ‘zanjeros’ get Colorado River water to California farms

In the right light, Jeff Dollente seems to make the sun rise. Standing over a canal, he cranks a wheel as the sun ascends and the sky yawns off the dark.

Mr. Dollente doesn’t deliver the morning, but in southeastern California’s Imperial Valley, his job is just as big. He delivers Colorado River water – a vital resource at risk – to farms that feed the rest of the United States.

He’s a “zanjero,” Spanish for ditch rider, for the Imperial Irrigation District, the area’s public-water and energy agency. California is entitled to the largest share of Colorado River water among seven basin states, and within that, the agency has the single largest entitlement, almost all of which goes to agriculture. Upping the ante: The river is the Imperial Irrigation District’s only water source.

The crisis on the Colorado River, strained by overuse and the effects of climate change, is unlikely to reverse due to recent heavy rain and snow, experts say. While critical lows along the river threaten water supplies and hydropower, California hasn’t agreed with other states this year on who should conserve how much – though the Imperial Valley is a controversial target of calls for cuts.

As the federal government prepares to weigh in and high-level talks continue, so do zanjero daily duties on the ground. It takes focus and precision to safeguard each drop of liquid gold.

“We hear about it every day,” says Mr. Dollente, referring to the Colorado River. “That’s what we’re here for – trying to save the water.”

“Like a milkman”

Mr. Dollente reports for duty in the “Carrot Capital of the World,” also known as Holtville. He’s low-key but loyal to his work, arriving for an interview with two pages of typed notes.

At a division office, he’s greeted with a daily run sheet outlining his deliveries. In jeans and plaid shirt, the zanjero wears shades on the brim of his baseball cap. It’s dark outside – not yet 6 a.m. – but by the end of his eight-hour shift, the February sun will burn bright. Warmer months bring triple-digit heat.

“Live down here, you get used to it,” says the Holtville local, who joined the district out of high school in 1985.

The Imperial Irrigation District is entitled to 3.1 million acre-feet of Colorado River water a year, though it uses less. (In 2021, for example, the district reports conserving 485,709 acre-feet.) The district also has among the most senior water rights on the river; junior water rights holders are generally expected to take cuts first. Imperial Valley growers – touting their efforts in farm-based conservation – are trying to hold on to a water-intensive farming tradition that’s more than a century old.

The Ditch Riders

Stories of the U.S. West’s water woes often run from the feast-or-famine saga of snowpack to overdrawn aquifers and conflict over a resource. In this episode, the Monitor’s Mountain West writer, Sara Matusek, talks with host Clay Collins about how she found and told a story of responsibility and ingenuity, of careful stewardship and agency that brings some hope.

Greening nearly half a million acres of farmland flanked by desert, the district gets its Colorado River water from the Imperial Dam on the California-Arizona border. The water nourishes alfalfa, winter vegetables, and other crops to the west – passing through some 3,000 miles of canals and drains – and then runs off into the Salton Sea. Robert Schettler, public information officer, calls it a daily miracle.

“There’s a tremendous amount of coordination,” says Mr. Schettler.

It’s a high-stakes relay race. From the Imperial Dam, water flows into the major All-American Canal, which feeds into three main canals, and then is directed into a series of lateral canals. Zanjeros – who oversee the lateral canals 24/7 – usher that water to delivery gates at the edge of farm fields, according to how much has been ordered.

“Like a milkman,” Mr. Dollente says.

Today on the Redwood Canal, he’s tasked with delivering water measured in cubic feet per second. At one stop, he raises a gate a mere inch higher to adjust the flow.

“They’re the face of the district to the farmer,” says Ralph Strahm, co-owner of Strahm Farms Inc. in Holtville. “They’re the ones that save the system from breaching if there’s a problem.”

Some days are stressful for Mr. Dollente. But he’s never fallen in. He’ll often clean canals of trash – a tumbleweed today. One time he found a cow, another time a gun.

Coyotes, roosters, and water

The water district employs around 140 zanjeros, currently all male. An experienced zanjero can make around $85,000, according to Mr. Schettler. (As of 2021, the census put the Imperial County median household income around $49,000.)

The term comes from the word zanja, or ditch, and describes part of the irrigation practices introduced by Spanish settlers in what would become California. Zanjeros have worked for the Imperial Irrigation District since it formed in 1911, once living in houses near the waterways they tended.

“They’re very valuable,” says Benny Andrés Jr., associate professor of history at the University of North Carolina, Charlotte, who’s from the Imperial Valley. “It’s a job that no one thinks about or knows about, but it’s very important.”

The role has also evolved alongside technology like cellphones. Mr. Strahm, the farmer, works closely with zanjeros and keeps their contacts in his phone. Still, he says he’d like to see the water district adopt more automation, which is widespread but most extensive along the larger canals, to support conservation.

“We need more accurate and timely delivery of water with recording devices to alert the zanjero when the water fluctuates,” says the grower.

Water-saving measures that he favors, like sprinkler or drip irrigation, don’t work when water fluctuates, he adds. “If there’s too little, the system shuts off. And if there’s too much, it can’t be used. It just goes to waste.”

Mr. Dollente agrees that enhanced automation would help with precision and conservation, though it’s considered expensive by the district. Some low-tech traditions have endured, like the yardsticks he uses for some measurements. But zanjeros no longer survey waterways on horseback.

Instead, Mr. Dollente travels with a laptop in one of the district’s white trucks, passing other white vehicles driven by U.S. Border Patrol. The two agencies are part of a safety campaign, reports the Calexico Chronicle, to stop drownings in the All-American Canal, which runs parallel to the Mexican border.

Work is often solitary for the zanjero, but he’s never quite alone. Coyotes pass by, roosters crow. And water sounds like gossip when it rushes through a ditch.

Difference-maker

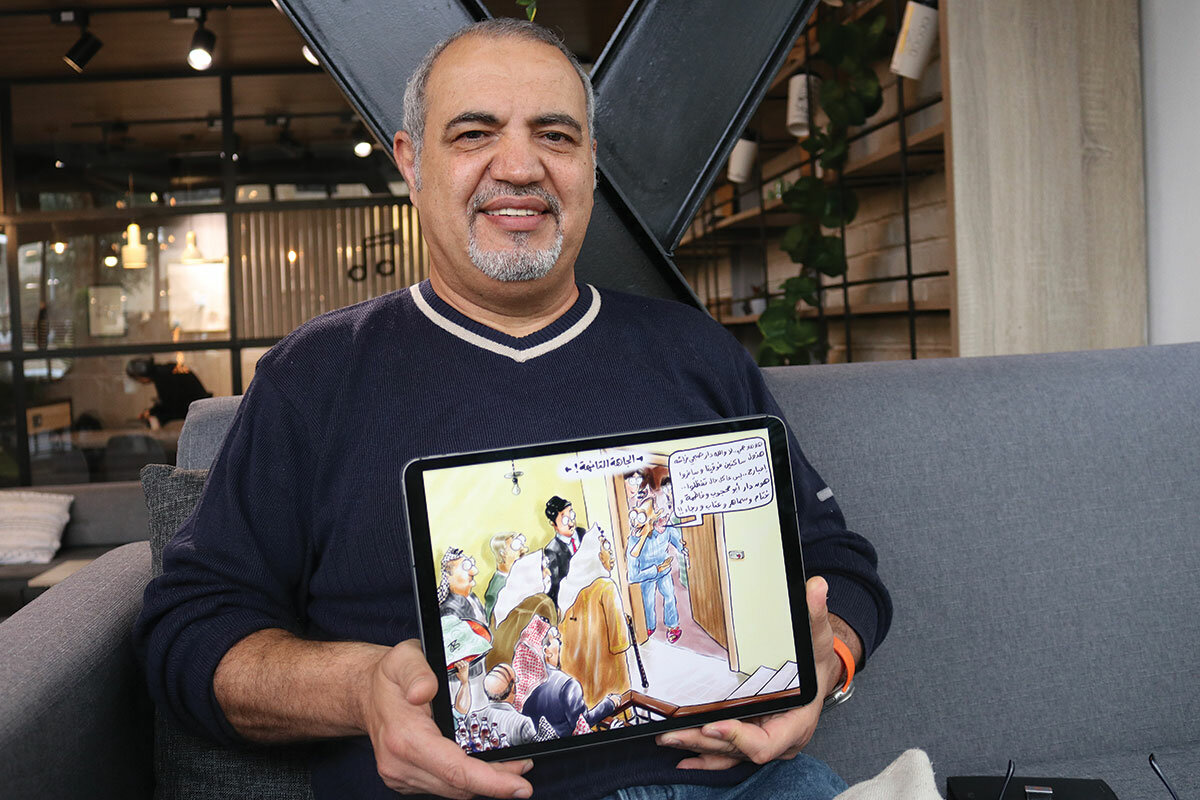

Emad Hajjaj challenges ISIS and strongmen – with laughter

It takes courage to speak truth to power. Despite risk of arrest, political cartoonist Emad Hajjaj believes holding up a mirror to Arab society is a responsibility – and a laughing matter.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Emad Hajjaj is a peddler of laughter and hard truth.

The Jordanian political cartoonist has poked fun at Arab and Western leaders, denounced wars, mocked ISIS, and memorialized the human cost of atrocities.

“Satire is a wonderful universal language that promotes awareness, laughter, and understanding,” he says.

It has also gotten him blacklisted and landed him in prison. Yet he draws on.

“To have front-line defenders continue their work like Emad Hajjaj is important, not only to the cause of press freedoms, but to people’s ability to discuss national issues,” says Nidal Mansour, director of the Amman-based Committee to Defend the Freedom of Journalists.

Mr. Hajjaj insists that he is neither a free-speech hero nor courting controversy. He says he simply wants to inspire future cartoonists.

Murad Kotkot is one of many cartoonists inspired by Mr. Hajjaj. “Emad Hajjaj taught me that cartoons were the fastest way to deliver a message,” he says. “It was a universal language that could speak to my community.”

Mr. Hajjaj’s determination to continue work after jail sent a message that “we all have a responsibility to keep drawing,” says Mr. Kotkot.

Emad Hajjaj challenges ISIS and strongmen – with laughter

Eyes locked in perfect concentration on his screen, he makes loops, curves, and squiggles that form the outline of two people and their speech bubbles, stopping only for the occasional sip of mint tea.

It is here at this corner table in a glassed, airy cafe-turned-makeshift office in West Amman where Emad Hajjaj has penned some of the most politically pointed cartoons in the Arabic press, on subjects such as abuse in Egyptian prisons, deadly Israeli raids in Jenin, and Putin’s war in Ukraine.

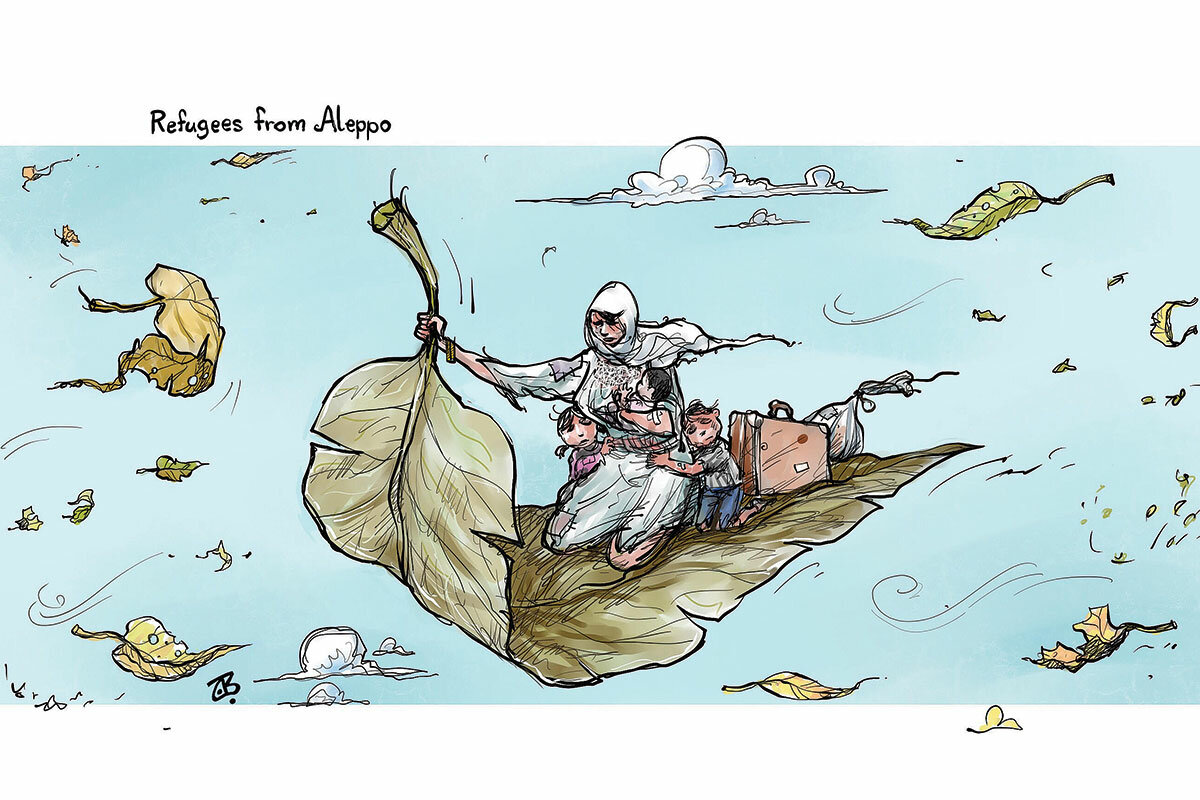

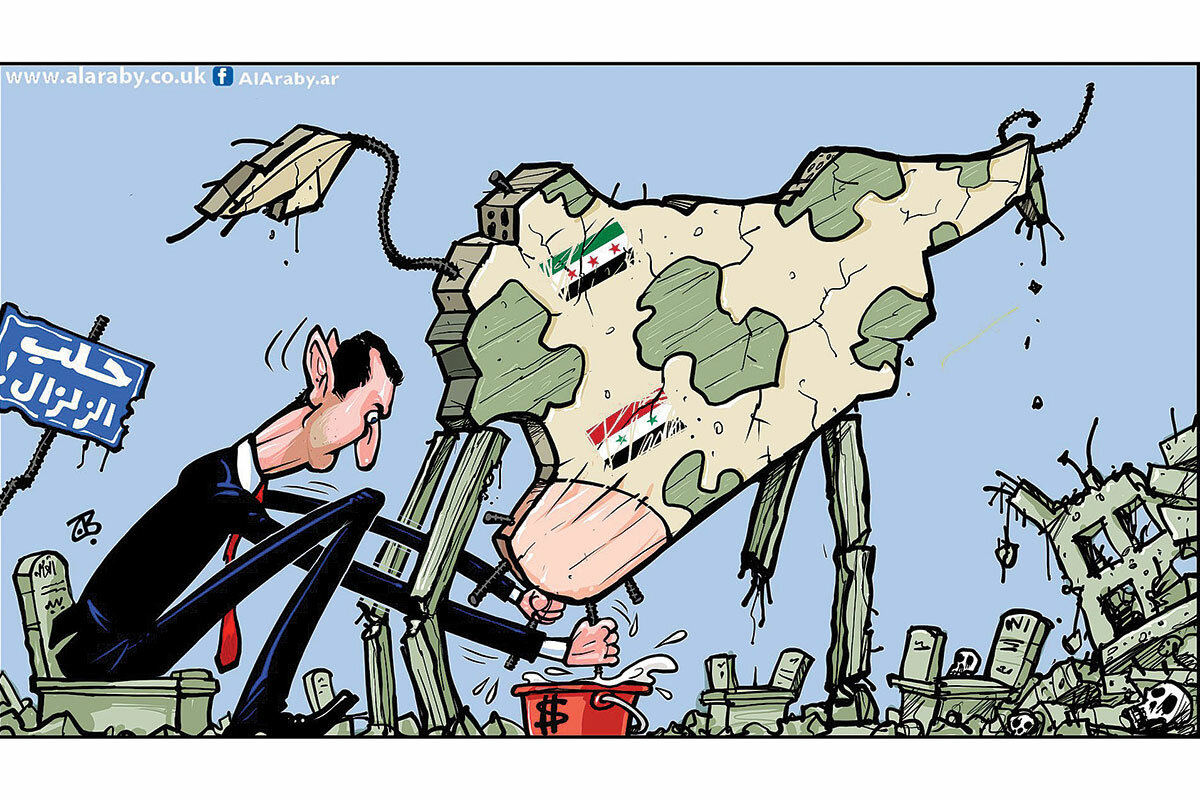

He has poked fun at Arab and Western leaders, denounced wars, mocked ISIS, and memorialized the human cost of atrocities, from 9/11 to Syria’s civil war.

At various times over the past three decades, these cartoons have cost him his job and future opportunities, gotten him blacklisted, and landed him in prison – making him a household name in Jordan and the Arab world along the way.

They have also made people laugh. Which is why he draws on, despite the threat of arrest. “Each morning I think of the person who reads the depressing news of the day: What will make him laugh, think, and inspire him to change his situation?” he says. “If there is something important and funny to say, then we have to say it.”

With the Arab world witnessing a stifling suppression of freedoms, Mr. Hajjaj remains one of the few cartoonists refusing to shy away from political issues. He champions democracy, human rights, and equality even as the governments around him actively suppress them.”

“At a time when the red lines are unclear, cartoonists and journalists who comment on political issues risk the threat of detention, a court case, prison time, huge financial penalties, and the loss of their livelihood,” says Nidal Mansour, director of the Amman-based Committee to Defend the Freedom of Journalists.

“To have front-line defenders continue their work like Emad Hajjaj is important, not only to the cause of press freedoms, but to people’s ability to discuss national issues.”

Laugh to think

When Mr. Hajjaj, fresh out of university in the early 1990s, began his career in Jordan, most Arab cartoonists focused on global issues such as the Israel-Palestinian conflict, the breakup of the Soviet Union, or American elections.

Mr. Hajjaj drew on the issues everyday Jordanians talked about, such as fuel prices, corruption, hypocritical parliamentarians, and bumbling government ministers.

“At the time no one was reflecting the concerns of the average Jordanian,” he says. “They weren’t helping people laugh and think about their situation.”

His punchy local cartoons caught on with readership, and he was appointed as a cartoonist at Al Rai, Jordan’s biggest daily.

There his most famous invention was Abu Mahjoob, a character typifying the average Jordanian, whom he employed to poke fun at and educate society, tackling protest movements, women’s rights, sexual harassment, and so-called honor crimes.

Right to dream

In the wake of 9/11, and amid a spike in global interest in the Arab and Muslim world, he increasingly published in Europe and the United States to give an insight into the way Arabs viewed the world. From 2014, many of his cartoons denounced and mocked the Islamic State, prompting death threats and placing his life at risk.

“I found a way to laugh at ISIS. I showed them for how ridiculous they were,” he says. “It was fighting back with a smile.”

But what perhaps has defined Mr. Hajjaj’s career is the 2011 Arab Spring and Arabs’ struggle for freedom, dignity, and human rights – themes he still draws on to this day.

Prior to 2011, he says, many cartoonists fell into a trap of depicting “Arabs afraid of their leaders, being left outside history.”

“And then suddenly you saw people fighting for their freedom in the streets in Tunisia and Egypt. It was beautiful.”

Inspired, he drew two to three cartoons daily on the Arab uprisings and push for democracy, often for free or to share on social media.

Even after anti-revolution forces arose and strongmen extinguished most of the lights of the popular uprisings, he has kept championing the cause of democracy and human rights in Egypt, Yemen, and Syria. Now he regularly draws cartoons mocking and denouncing populist President Kais Saied’s dismantling of democracy in Tunisia – even as other Arab journalists shy away.

His reputation as the “Arab Spring cartoonist” continues to cost him job opportunities across the Arab world, an informal blacklisting. His cartoons are now only published by London-based Arabic and Western newspapers.

“I still believe that one day we will see our societies rise up and secure our basic rights, human rights, and democracy, like any other people in the world,” says Mr. Hajjaj. “Today people may see this as idealism and not realistic, but I believe it is our right to dream about it and to keep this dream alive.”

But this commitment to honesty and comedy has gotten him into trouble. In 2020, one cartoon landed Emad Hajjaj in jail.

It was, he believed at the time, a harmless cartoon commenting on regional dynamics concerning the Abraham Accords, normalizing relations between Israel and the United Arab Emirates.

The cartoon mocked the UAE failure to secure F-35 fighter jets from the U.S., then perceived as a potential Washington “sweetener” to get Abu Dhabi to sign the accords. In the cartoon, a dove spits in the face of an Emirati man, with “F-35” written on the droplets.

Within days of publishing the cartoon, Mr. Hajjaj was arrested and transferred to a military tribunal. “I was in the same cage as the jihadists I used to draw. It would’ve been comical if it wasn’t terrifying,” he says.

The cartoon was considered to be “harming Jordan’s relations with a friendly country.” Jordan relies on Emirati aid and jobs for Jordanian expats.

He was charged under anti-terrorism legislation and faced 3-10 years in prison. After he was convicted and spent five days in prison, he was suddenly released without an explanation. Some say it was likely a royal pardon.

“We all need a smart laugh”

Mr. Hajjaj continues drawing to this day – albeit with a new daily routine. “I no longer have a chief editor. But I have a lawyer to vet all my cartoons,” he says. “Sometimes he rejects them, and those cartoons go unpublished.”

Journalist Murad Kotkot is one of many who grew up with Mr. Hajjaj’s cartoons, and was inspired to become a cartoonist himself. “Emad Hajjaj taught me that cartoons were the fastest way to deliver a message. It was a universal language that could speak to my community,” he says.

Mr. Hajjaj’s determination to continue work after jail sent a message that “we all have a responsibility to keep drawing,” says Mr. Kotkot.

“If we are discouraged and leave the profession because of red lines, then we are not political cartoonists. I learned that we lose or gain our value whether we confront and overcome these challenges and tackle these difficult issues,” Mr. Kotkot says.

Today Mr. Hajjaj insists that he is neither a free-speech hero nor courting controversy.

He says he simply wants to inspire future cartoonists, and regularly visits schools across Jordan, encouraging children who love to draw: “Study arts! The world has many doctors but needs more cartoonists.”

“Satire is a wonderful universal language that promotes awareness, laughter, and understanding,” he says, putting the final touches on an Abu Mahjoob cartoon on his iPad. “And we all need a smart laugh now more than ever.”

Points of Progress

Laws with teeth: Slowing shark loss and new coal mines

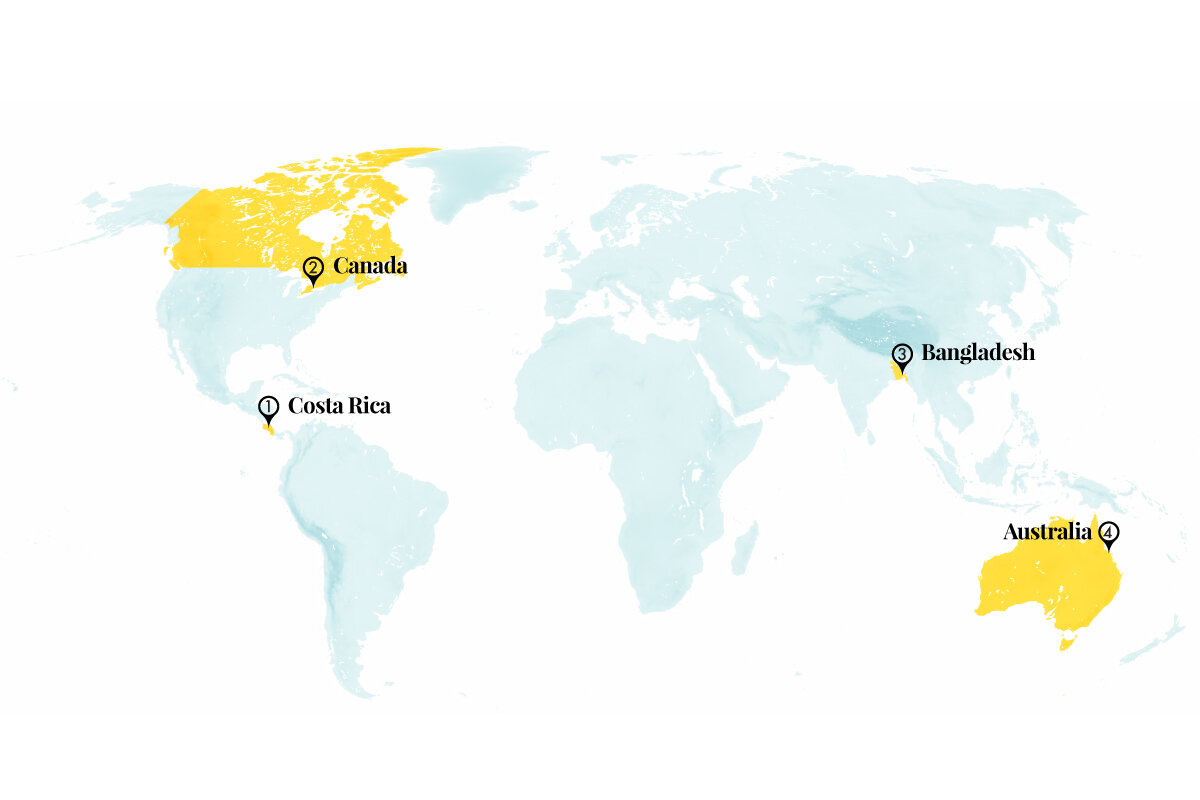

In our roundup, progress in environmental protection is made by legal means in Costa Rica and Australia. And in Bangladesh, planning for the future includes opening the capital’s first rapid transit stations.

Laws with teeth: Slowing shark loss and new coal mines

1. Costa Rica

Costa Rica has outlawed fishing of hammerhead sharks. Despite being protected since 2014 under the CITES convention, the sharks have been caught and sold in the country for years.

Local biologist Randall Arauz began raising awareness of shark finning in 2003. And since 2011, education campaigns in China have sharply lowered consumption of shark fins as a food of status and celebration, but demand has increased in other parts of Asia. For the great hammerhead shark alone, global populations have declined more than 80% over the past 70 years.

The presidential decree comes 10 years after Costa Rica itself had requested CITES protection of a hammerhead species. In 2018, the country established a hammerhead sanctuary in Golfo Dulce, a key gulf used by the sharks to reproduce. And in 2020, the Supreme Court struck down a former president’s legalization of the shark trade.

Given its mixed record on shark conservation, wildlife advocates have questioned Costa Rica’s commitment – but are hopeful that February’s decree has teeth.

Sources: Mongabay, The Goldman Environmental Prize, DeeperBlue.com, The Washington Post

2. Canada

A new helmet makes outdoor sports safer for Sikh children. Ontario resident Tina Singh, who is Sikh and an occupational therapist, designed the helmet after her children started riding bicycles, and she realized that standard helmets didn’t fit over the patkas worn by Sikh boys to cover their hair. Her design meets safety certifications for use with bicycles, skateboards, scooters, and in-line skates, and is shaped to accommodate a patka. Ms. Singh wants to expand her designs to work for hockey players and remove barriers for athletes with other needs.

Moezine Hasham, founder of the nonprofit Hockey 4 Youth, based in Toronto, said “the creation of this type of helmet is now going to create an inclusive space. It’s going to foster belonging.”

Sources: CBC, North Shore News

3. Bangladesh

Bangladesh has opened the country’s first rapid transit stations. The rail system is expected to shorten commutes in metro Dhaka, home to more than 22 million people, while also cutting carbon dioxide emissions and sound and air pollution.

The entire 13-mile line is due to be completed later this year, and five more rail lines are planned. While not heavily reliant on motorized vehicles for a city its size, unplanned roads and high population density in the fast-growing megacity contribute to congestion. In Dhaka, the average driving speed is less than 5 miles per hour, and studies suggest that drivers in Bangladesh burn 40% more fuel than necessary from time spent in traffic.

Researchers at the Bangladesh University of Engineering and Technology also note that better system integration is needed. Bus companies compete with each other for riders on more than 300 routes, lowering service quality. By 2035, buses are still expected to provide 40% of commutes. Once the first rail line is fully operational, it’s expected to cut annual CO2 emissions by 500,000 metric tons by 2050.

Sources: Context, The Daily Star

4. Australia

Australia has blocked a new coal mine, based on environmental concerns. The open-pit mine was set to be located about 6 miles from the Great Barrier Reef. “The adverse environmental impacts are simply too great,” said Environment Minister Tanya Plibersek in her announcement of the decision. “The risk of pollution and irreversible damage to the reef is very real.”

The move marks the first time the federal government has used environmental laws to block a coal mine, and it could set a precedent for 18 other coal and gas proposals under review. The project would have produced 10 million metric tons a year of both thermal and coking coal for 20 years. Dangers to local habitats included groundwater and freshwater streams that provide breeding grounds for certain fish and carry water to the largest reef system on the planet. The Great Barrier Reef faces continuing threats, including acidification and rising ocean temperatures.

Sources: BBC, Yale Environment 360

World

Women are making strides in political leadership across the globe. More than a quarter of lawmakers – 26% – at the national level are women, up from 11% in 1995, according to the Inter-Parliamentary Union. Much of the progress is attributed to gender quotas, which typically mandate parties nominate a certain percentage of women, or reserve a certain number of legislative seats.

In Japan, women hold 10% of seats, and representation is similarly lopsided at less than 10% in about two dozen countries, including Nigeria, Sri Lanka, and Qatar. Yemen has no women in the legislature.

But gains have been made elsewhere. In Rwanda, women make up 61% of the national legislature. Women hold slight majorities over men in Cuba, Nicaragua, and New Zealand, while Mexico and the United Arab Emirates have a 50-50 split. Women in Iceland, Costa Rica, Sweden, and South Africa make up just less than half. The United Nations predicts gender parity in national legislative bodies won’t be reached until 2063.

Sources: Context, Inter-Parliamentary Union

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

One way to escape Russia’s orbit

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

As a young democracy eager to join the European Union, Georgia was told last year by the EU to first show more harmony and less polarization in its politics. Well it certainly did that last week. By the tens of thousands, people turned out in great diversity, from young teens to seasoned scholars, to protest a Russian-inspired bill pushed by the ruling party to muzzle journalists and civic activists – just before an election the party fears it might lose.

“They can’t erase our yearning for freedom,” one protester told Politico. The sudden burst of national unity – some 80% of Georgians want to join Western institutions – forced the Georgian Dream party to quickly shelve the measure.

Mark it up as another victory for countries near Russia – from Moldova to Mongolia – that have rejected Moscow’s autocratic methods or at least distanced themselves from Russia’s aggression in Ukraine. Attempts by President Vladimir Putin to re-create the Russian or Soviet empire are clearly up against global gains in democratic ideals, especially among youth.

Now less polarized, Georgia has found more of its civic identity. As a 15-year-old protester told Agence France-Presse, “Europe is freedom, Russia is a kind of prison.”

One way to escape Russia’s orbit

As a young democracy eager to join the European Union, Georgia was told last year by the EU to first show more harmony and less polarization in its politics. Well it certainly did that last week.

By the tens of thousands, people in the small Caucasus state turned out in great diversity, from young teens to seasoned scholars, to protest a Russian-inspired bill pushed by the ruling party to muzzle journalists and civic activists – just before an election the party fears it might lose.

“They can’t erase our yearning for freedom from our brains, they can’t rip it off our hearts,” one protester told Politico. “I’m not afraid to be arrested. No bullets, no tear gas can stop me.” The sudden burst of national unity – some 80% of Georgians want to join Western institutions – forced the Georgian Dream party to quickly shelve the measure.

Mark it up as another victory for countries near Russia – from Moldova to Mongolia – that have rejected Moscow’s autocratic methods or at least distanced themselves from Russia’s aggression in Ukraine. Attempts by President Vladimir Putin to re-create the Russian or Soviet empire are clearly up against global gains in democratic ideals, especially among youth.

“Moscow’s claims to regional hegemony were always sustained not by genuine authority, let alone respect, but a willingness to pay in blood and treasure for the appearances of empire,” writes Botakoz Kassymbekova, an assistant professor at the University of Basel in Switzerland, in Foreign Policy. “In 2023 it is no longer clear that Russia can afford this price.”

The bill that almost passed in Georgia is similar to a Russian law passed in 2012 that brands any news media or civil-society groups as “foreign agents” if they receive more than 20% of their funding from abroad. Georgia’s ruling party, which is controlled by an oligarch with business ties to Russia, perhaps hoped the measure would have blocked ballot watchers during next year’s election.

The mass protests have clearly improved the chances of Georgia becoming a formal candidate to join the EU, the country’s president, Salome Zourabishvili, told Bloomberg. “When the society is united they can defeat even the majority that is in the Parliament, and that’s what is important,” she said.

Now less polarized, Georgia has found more of its civic identity. As a 15-year-old protester told AFP, “Europe is freedom, Russia is a kind of prison.”

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Prayer can resolve economic hardship

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Martine Blackler

Even in what seem to be dire situations, leaning on God’s will instead of our own agenda leads to progress, as a woman found when her family’s business was in danger of bankruptcy.

Prayer can resolve economic hardship

My husband’s business had been struggling for a while and was now in serious financial trouble. Our competition was taking advantage of this, undercutting our prices and taking our customers. Vicious accusations were leveled against us. Furthermore, our suppliers were raising their prices, and we fell behind in our payments, causing them to close our accounts.

It seemed that nothing was going to save us from bankruptcy. Then our business faced three months of total inactivity when the Covid-19 pandemic struck, and we were in danger of losing our home.

When things began looking desperate, we asked a Christian Science practitioner to pray for us, and we began to feel the effects of his prayers. It eventually dawned on my husband and me that we needed to stop all worry and merely human efforts – which had done little to resolve matters – and to pray instead. Every day we affirmed God’s allness and endeavored to see that divine Principle, not human will, was governing every aspect of our business. With humility, we listened – really listened – for God’s “still small voice” (I Kings 19:12).

At the time, I was the First Reader of our branch Church of Christ, Scientist. During the service one Sunday, the words “Thy will be done” (Matthew 6:10) kept coming to me. This is from the Lord’s Prayer that Christ Jesus taught his disciples. After the service I had a chance to think more deeply about what it actually means to let God’s will be done. The human mind always suggests that we need to take some action in order to disentangle ourselves from a problem. But this action, when based on human reasoning or willfulness, can be misguided.

In “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” Mary Baker Eddy, the discoverer of Christian Science, writes, “Will-power is but a product of belief, and this belief commits depredations on harmony” (p. 490). “Depredation” is an act of robbing or plundering, and it occurred to me that my husband and I were actually robbing ourselves of harmony by insisting that the day-to-day affairs of our business be conducted our way. It took humility to stop the human striving, all the pushing and demanding, and let God’s will be done, trusting that our business would unfold according to the divine Mind.

As I prayed, I saw that the business was actually an idea of God and was under God’s – Mind’s – harmonious control; it reflected the uninterrupted activity and completeness of divine Life, the honesty of Truth, the integrity of Principle, the cooperation of Love (Life, Truth, Principle, and Love are synonyms for God used in Christian Science). There are no vacuums in God’s kingdom, and no holes to fill, since divine Love fills all space. And there can be no competition or jostling for position, since each of us is God’s eternally cared-for child; we all have what we need and move at God’s direction. God is the source of everyone’s good, being the one, abundant supplier, providing and maintaining an infinite and uninterrupted chain of supply.

Would-be stumbling blocks were overcome through daily prayer. Eventually, prayer inspired us to take specific steps. One by one, our customers started to trade with us again. Our competition reached out to us for assistance, and the aggression we had felt from that sector dissipated completely, leaving a harmonious working relationship that continues today.

Then, last year our province of Kwazulu Natal, South Africa, experienced severe weather and flooding, and our supply depot was destroyed. It seemed no supplies would be coming to the coastal area where we were, and the suppliers had no idea if they would ever begin to trade again. Surprisingly, we received a call from the last source I would have expected – our competition. They said we could buy the products we needed from them. How blessed we felt!

I continued to pray to know that nothing could be added to or taken away from the continuous flow of good, and soon our suppliers were back in operation, to the amazement of all.

I share this experience in the hope that it will encourage those who are struggling in these challenging economic times, as it illustrates God’s care for all of His children.

Adapted from an article published in the Feb. 6, 2023, issue of the Christian Science Sentinel.

Viewfinder

Need a lift?

A look ahead

Thanks for starting your week with us. Please come back tomorrow, when columnist Ned Temko will discuss the China-brokered renewal of Saudi-Iranian relations, and what the United States might do next.