- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 15 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

When getting the story right is hard

Mark Sappenfield

Mark Sappenfield

Sometimes, a story comes together with kinetic beauty. An idea emerges, and with a minimum of fuss, it is done. Today’s lead article was not one of those stories.

That’s not criticism. Rather, it is a product of the subject: the roots of violence. American conversations about gun violence – particularly mass shootings – often revolve around gun laws and mental health.

But the closer we looked, the more we saw something else. There is no single “gun violence problem” in the United States, but different challenges in different places. And within these trends, one sticks out for its clarity and constancy: The American South has dramatically higher levels of violence. Why?

In traveling to Nashville, Tennessee, and Alexander City, Alabama, Noah Robertson and Patrik Jonsson sought to show different faces of violence in the South, in large cities and rural hamlets, without falling into stereotypes or shallow narratives. To ensure he got the story right, Patrik went back a second time.

What we found was a portrait not of policies or legislative bills, but of an underlying mental landscape and how that has led to higher rates of violence. But that same rule applies to all regions – in the U.S. and around the world. The roots of violence everywhere are as much mental as political, influenced by culture and values. Finding answers will be impossible without understanding those deeper forces. And that takes a lot of work.

Today’s lead story, as arduous as it was, is an attempt to do that – to understand an important part of America just a little bit better, to help open the door to progress for all.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Untangling roots of violence: Lessons from the South

Beneath the South’s reputation for comfort food and a friendly welcome lie deep roots of violence. Can untangling them help uproot them?

-

Patrik Jonsson Staff writer

-

Alfredo Sosa Staff photographer

-

Melanie Stetson Freeman Staff photographer

America is the most homicidal rich country in the world, and from its founding, the South has been the country’s most violent region.

Over time, academics developed two broad theories. One is that Southern violence comes from Southern culture. That includes racism and “honor culture,” defending one’s reputation through violence. The other theory is that Southern violence comes from the region’s weak institutions, such as poor education, employment, or policing.

But there’s no separating the two theories. Culture shapes institutions. Institutions shape culture. In the South, both have always bordered violence.

Most clearly, these two forces collide in slavery. But even after emancipation, white Southerners kept using violence to intimidate former slaves. Some 4,400 lynchings took place from 1877 to 1950.

But there are signs of progress. One of them is Ron Johnson. Born and raised in Memphis, he grew up all too familiar with Southern violence, but as Nashville’s first community safety director, his job is to help reduce violence. And one of the tools he plans to use is a swimming pool near two of the city’s housing projects, where the median income can be as low as one-tenth that of the county average.

In 1961, Nashville closed all 22 of the city’s pools after an attempt to integrate one. Eventually, all but one reopened. Now the same city is helping keep a pool open year-round in a mostly Black neighborhood. That’s a message, says Mr. Johnson.

Like any resource, a pool keeps people from feeling ignored, he adds. “Literally, without a doubt, I believe it will save lives.”

Untangling roots of violence: Lessons from the South

The meeting adjourned soon after the shouting started.

A dozen or so people had come to the city council meeting on a Monday night in late April 2016. And everyone was angry. Tony Goss, a councilman, had called the mayor a “dictator” for firing the city finance director. Mayor Charles Shaw said the director hadn’t done her job.

An audit firm, meanwhile, was discussing the city budget – which was really the problem. The city council was fighting about money because there wasn’t much money to fight about.

Alexander City – this rural town an hour outside Montgomery, Alabama – was collapsing.

There were the mounting lawsuits: for allegedly running a debtor’s prison, for a cop who shot and killed an unarmed Black man, for a police chief – also Black – who said he was unfairly fired.

Then there was the mill, the Russell Athletic mill, which for some 110 years had anchored the local economy. A century ago, its founder, Benjamin Russell, helped bring Tallapoosa County telephone lines, electricity, and its defining geographic feature – Lake Martin, a 64-square-mile reservoir filled by a 1926 dam. People at the time called Alexander City “Benjamin Russell’s town.”

But in 2013, after years of decline and the loss of thousands of jobs, the town’s mill closed. With it went the last few hundred Russell jobs, the core of the middle class, and much of what made Alexander City a town.

So now, in their downtown chambers, there wasn’t much for Mr. Goss, Mayor Shaw, and the city council to do but argue. And argue they did, until arguments became a shouting match, and the shouting match ended in a fight. As Mr. Shaw left, he says he heard a “cuss” at his wife from Mr. Goss.

And Mr. Shaw swung.

He landed several punches before being pulled away. A photo shows him being dragged back by the neck, over folding chairs and a blue carpet.

The next day, Mr. Shaw and his wife, Laverne, who had joined in the fight, turned themselves in to the police. The local paper ran their mugshots in jailhouse stripes, which became an image of the town’s decline. A few months later, the mayor was convicted of third-degree assault and given a year’s probation with a suspended 30-day jail sentence. His wife was acquitted on the same charge.

“I did what any real man would do after being called a dictator and a liar and someone talking to my wife that way,” says Mr. Shaw. “I grew up in the South and was taught to always, always take care of your family, your property, your people.”

Mr. Shaw isn’t a violent man. That night, he says, was the first time he’d thrown a punch in his life, then 72 years.

But he comes from a violent culture. Amid its chaos, Alexander City was the 18th-most violent small town in America in 2018, according to FBI statistics. Nearly every year, Alabama has one of the top three homicide rates in the country. The South is and almost always has been America’s most violent region.

That violence appears in seemingly random murders and brawls, like Mr. Shaw’s. It appears in regionwide organized crime. It shows up in the rural South and the urban South, the mid-South and the Deep South. Perhaps most importantly, it shows up across time.

Over 400 years, experts say, the South has reinvented itself more than any other region in America, from slavery to the Civil War to the Civil Rights Movement. It’s gone from a lawless Colonial frontier to the country’s fastest-growing region. And yet, despite its constant change, the South has always stayed violent.

Think of it like an unchecked habit. The American South was built around an economy of violence in slavery, which then made it harder to develop the institutions that deter violence, such as strong schools and courts. Over time, a tendency toward violence became part of Southern culture, consistent even as the region changed.

America has a violence problem. There’s almost no better sign than its mass shootings, such as the recent ones in Nashville, Tennessee, and Dadeville, Alabama – just 15 miles from Alexander City. The repetition has left many Americans feeling resigned to the fact that America is a violent country. But it’s the South that shows how deep the roots of its violence go, and how hard it is to pull them out.

America is the most homicidal rich country in the world, and from its founding, the South has been America’s most violent region.

Colonial Virginia’s murder rates were often more than double those in New England, where homicides have always been rarest in the country. By the 1820s, the murder rate in many slaveholding states was more than twice that of the North’s most dangerous areas – cities like Boston and Philadelphia. Those distinctions survive.

Of the country’s 10 most homicidal states per capita in 2021, six were in the former Confederacy. Four of those were in the top five, some with homicide rates more than 10 times some states in New England.

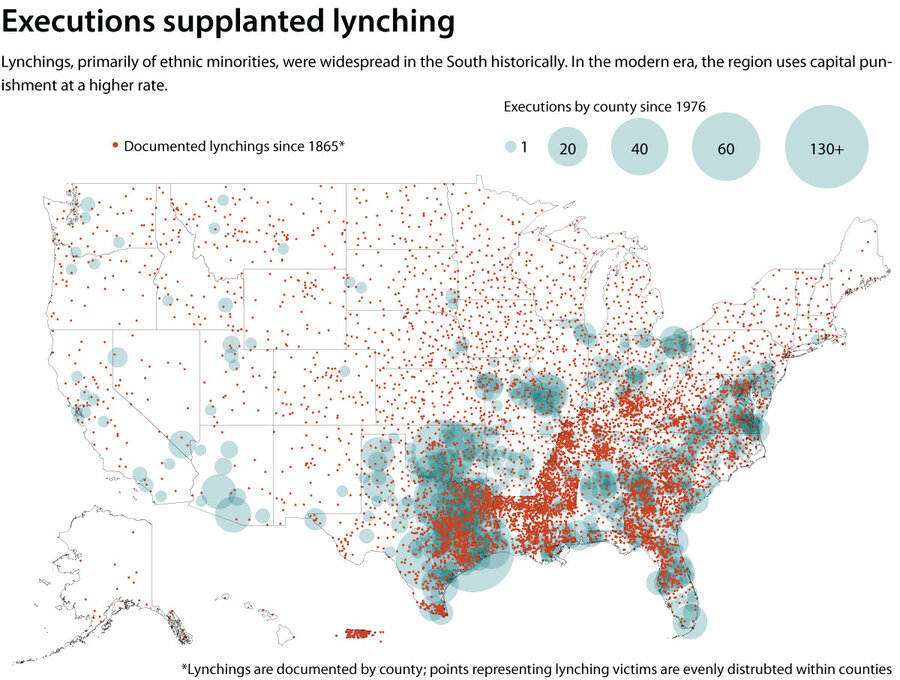

Nearly every Southern state has a stand-your-ground law, which allows people to legally use force – even deadly force – to defend themselves in public. All but one state in the region permits the death penalty. Seven of the 10 states with the highest execution rates between 1976 and 2020 were in the former Confederacy.

The South’s violence “extends across geography, class, race, and politics,” says Ed Ayers, a historian at the University of Richmond. “But it’s also extended across time to a remarkable extent.”

Over time, academics developed two broad theories. One is that Southern violence comes from Southern culture. That includes racism and “honor culture,” defending one’s reputation through violence – similar to Mr. Shaw’s fight. The other theory is that Southern violence comes from the region’s weak institutions, such as poor education, employment, or policing.

But there’s no separating the two theories. Culture shapes institutions. Institutions shape culture. In the South, both have always bordered violence.

Most clearly, these two forces collide in slavery. Some 12.5 million enslaved Africans traveled the Middle Passage to the New World. Around 4 million enslaved people lived in the South at the start of the Civil War. And there was no more violent, no more influential part of the South’s past than slavery.

In the Deep South, enslaved people worked crops that required sharp, heavy tools that could easily become weapons. Heavily outnumbered slave owners maintained their authority through violence: beatings, starvation, sexual violence, sometimes even execution.

After the Civil War and emancipation, white Southerners kept using violence to intimidate former slaves. Farm labor was restricted to the sharecropping system, which resembled slavery. Over decades, county sheriffs rounded up thousands of Black men with phony charges and trapped them in the convict leasing system – whose chain gangs were often run by former slave drivers.

“The violence that we see after slavery is an extension of the violence of slavery,” says Kidada Williams, a historian at Wayne State University.

Some 4,400 lynchings took place from 1877 to 1950, according to the Equal Justice Initiative, which includes in its count racial massacres. Those lynchings peak in the 1890s and fall after Southern states institute segregation and disenfranchisement.

“The people who create segregation are people at the top, and from their point of view, they are managing race relations by replacing violence with law,” says Professor Ayers.

The legacy of this violence can be measured today.

Areas of the South where lynchings were more common now have higher rates of capital punishment, white-on-Black homicide, and prison admission. States that permitted slavery in 1860 now execute more prisoners. Between 1977 and 2005, some 90% of all executions occurred in former slave states.

CSDE Lynching Database; “National Crimes: A New National Data Set of Lynchings in the United States, 1883 to 1941” by Charles Seguin and David Rigby; Death Penalty Information Center

One of the things criminologists know about violence is that proximity is often prophecy. The more you grow up around it, the more likely you are to commit it. In some cities, three-fourths of all violent criminals have lengthy criminal backgrounds, says Richard Rosenfeld, an emeritus criminologist at the University of Missouri–St. Louis.

Call it the Southern cycle. The culture and weak institutions expose the region’s people to violence. A higher exposure to violence makes people – especially young men – more likely to commit it themselves.

On the cusp of the Deep South beside the Mississippi River, Memphis has always been violent. In 1866, it had one of the worst racial massacres in American history. Surrounding Shelby County had the highest rate of lynching in Tennessee. By the 1960s, the city had become known as the “murder capital of the world.”

This is where Ron Johnson grew up, the fifth of 10 boys, in a city housing project.

In 1968, at the age of 5, he watched tanks roll outside his window after the mayor declared martial law. When Martin Luther King Jr. was killed downtown, just a few miles away, he saw his father, who worked in law enforcement, come home and get a gun and leave without a word. He returned two days later to cry in his wife’s arms.

Senior year of high school, Mr. Johnson cradled his best friend as he died after being stabbed 15 times.

In moments like this, Mr. Johnson turned to his mother, nicknamed Duke – a gospel singer known to worship with such force that she would sometimes pass out on stage.

Duke knew how Memphis shaped her sons, especially Ron. He was a fighter. In pickup basketball games at the community center, if someone fouled him hard, he would swing back – kicking out their legs and punching so fast he started calling his hands “lightning.”

She stopped letting Mr. Johnson go there alone, making him bring a brother to supervise. She let him play sports, especially football, where as a free safety he could hit people within the rules of the game. She never let him see her angry.

His senior year, a girl signed his yearbook, “Most likely to be dead before he’s 25.” Mr. Johnson knew who it was by the handwriting – a classmate he’d bullied – and wanted to confront her. Duke told him the same thing as always.

“Don’t worry, baby. She don’t know you like that.”

Mr. Johnson let it go. Soon he left for college on a football scholarship to Tennessee State University, in Nashville. He knew that if he had his mom, everything would be all right.

Americans tend to tie violence to places like Memphis: urban, Democratic, often heavily Black, places where troubles rise to the point of cliché.

Then there are places like Alexander City – called Alex City by locals. The town of roughly 14,600 is rural and nearly two-thirds white. Just over 71% of Tallapoosa County voted for Donald Trump in 2020.

And yet, only two years before, the violent crime rate in Alex City had risen to a level about five times higher than the national average – including cities like Chicago, New York, and Los Angeles.

“Here’s a small, rural, conservative town: What the [expletive] happened?” says Jay Shipp, who runs a local roofing firm.

Alex City is not as much of an outlier as it seems. Over the last 21 years, states that voted for Donald Trump in 2020 – mostly rural and almost all of the South – had far higher homicide rates than states that voted for Joe Biden, according to a report from Third Way, a center-left think tank.

Even when rural and urban areas have similar homicide rates, it’s easier to ignore violence when people are more spread out. In cities, one homicide in a neighborhood could make thousands of people feel unsafe. In the country, neighborhoods are far less dense and people often feel less connected to the violence that occurs.

That is, until it overwhelms a town, as it did with Alex City.

Crime began dominating local headlines: A man survived being shot in the head during a home invasion by three men wielding shotguns who stole $2, a resident was killed while mowing his lawn, a reality TV star shot someone after a pool game.

It became for many an identity crisis. In Alex City, strangers introduce themselves when you sit next to them at lunch. Downtown is small and quaint, where hunters come to sing karaoke on Wednesday nights and a yearly jazz fest makes the town feel like Bourbon Street.

To Mr. Shaw, the former mayor, Alex City had been the safest place he knew. At a certain point, he accepted that was no longer true.

“A way of life ended,” says Todd Ford, who grew up near the town’s old mill.

In fact, violence here goes back centuries. Four known lynchings took place in Alex City. Its namesake, Edward Porter Alexander, who brought rail service to the town, was a Confederate officer considered a hero at the Battle of Gettysburg.

That violence continues to appear in people’s lives.

Fifteen years ago, Cordero Robbins was at a convenience store when he was hit with crossfire during a shooting. It cost him a full college scholarship to play basketball and months of recovery.

After exiting the hospital and recovering at his mother’s house, Mr. Robbins was stopped by a sheriff’s deputy – apparently he fit the profile of an armed robber who had stolen from the sheriff’s daughter. It took five hearings for Mr. Robbins to be declared innocent.

“People see this violence and just shrug it off, like, ‘that’s crazy,’” says Mr. Robbins, now a local diesel mechanic in his mid-30s. “But it isn’t crazy. It’s reality.”

The too-common outcome of violence breeding violence hasn’t been Mr. Robbins’ reality, though. Sitting in jail after his arrest, he never felt so angry he wanted revenge, he says. But he did ask God, why me?

“It took some years,” he says, to figure out what really had happened. But in court when his assailant offered an embrace in apology, Mr. Robbins, though caught off guard, went ahead and accepted it.

In the South, violence is neither an urban problem nor a rural problem. It’s neither an old problem nor a new problem. It’s just a problem, in need of a solution.

FBI Uniform Crime Reports

Days after his family visited to watch him play football his junior year of college, Mr. Johnson was finishing drills on the field when his coach drove up nearby. “Spiderman,” the coach yelled out, using Mr. Johnson’s nickname. “I need you to ride down to the office with me.”

After fidgeting on the way over, Mr. Johnson picked up the office phone and heard his brother’s voice.

“She’s gone, man,” he heard. “She’s gone.”

His mother had just been shot and killed, an accidental target of a shooting near their home. “I just dropped the phone,” he says. Mr. Johnson walked laps in the gymnasium with a teammate who held him up. “I just talked to her,” he kept thinking.

Mr. Johnson fell into the drug trade, then prison, where he spent four years rebuilding his life. He later returned to Nashville and became a group counselor who urged young men away from gang violence. Two years ago, he became the city’s first community safety director.

In mid-March, he walks down the hallway, speckled like Fruity Pebbles cereal, in Napier Community Center, 2 miles south of downtown. Through a set of doors, he enters the building’s pool, the blue water made brighter by his clashing red suit.

Last year, the city paid to install a heater in this pool, allowing it to stay open year round. “Literally, without a doubt, I believe it will save lives,” he says.

This neighborhood is near two of the city’s largest housing projects – both hot spots for violence – where the median income can be as low as one-tenth that of the county average. A pool here, like any resource, keeps people from feeling ignored, says Mr. Johnson, who grabs a handful of mints. They’re Life Savers.

Nashville is a relatively safe city, but its murders are climbing. Since 2020, the city’s homicides have been above 100 each year – around double the yearly numbers 10 years ago. Among midsize counties, Davidson ranked 16th in the nation for gun-related deaths, according to a 2022 study.

The money spent to improve Napier’s pool is part of a $300,000 investment in the area, improving lighting, adding speed bumps to stop drag races, and funding the library.

“We’ve had that support, we’ve had that advocacy and it’s been great,” says Jemeka Usher, who lives nearby. “But we haven’t always had it.”

Mr. Johnson’s job is to help reduce violence, and also to convince people like Ms. Usher, whose two youngest children are in high school, that help is here to stay.

In 1961, Nashville closed all 22 of the city’s pools after an attempt to integrate one near Centennial Park. The others later reopened, but that one was filled with cement and covered with grass, as though it never existed. Now the same city is helping keep a pool open year-round in a mostly Black neighborhood. That’s a message, says Mr. Johnson.

“There’s roots, and you’ve got to dig the roots up,” he says.

After the 2016 fight, Alex City’s local government turned over. Many sitting members didn’t seek reelection. That November, an almost entirely new city council took office, along with a new mayor.

Scott Hardy is one of those members. He decided to run, like some of his other colleagues, after hearing about the fight.

“We had become a joke,” he says.

The new city council began diversifying the local economy, trying to prevent another case of economic free-fall. The town will likely benefit from a project to mine graphite, which sits plentifully underfoot and was recently declared a mineral of national importance for its role in batteries.

In the last several years, as locals began to trust their government again, violence has begun to fall – even as it rose elsewhere across the country during the pandemic.

“It’s been a struggle at times,” says Mr. Hardy. “But there’s been a conscious effort to raise the bar for what Alex City is going to be.”

An hour southwest, Bryan Stevenson hopes the same thing for the rest of the South.

Mr. Stevenson is executive director of the Equal Justice Initiative, a civil rights organization based in Montgomery. Among its projects, EJI places memorials for victims of lynching in the United States. Its goal is to put up a historical marker at every lynching site in the country. EJI has done so in 100 communities so far, including Memphis and Nashville. It’s an attempt at historical remembrance, similar to efforts in post-Nazi Germany and post-apartheid South Africa.

“Violence doesn’t seem unacceptable because it is part of this long history,” he says. “We entered the 21st century having never really reckoned with the ways in which we have become a violent society.”

Cue the reckoning, which in partnership with the EJI is taking place in the South from Nashville to New Orleans. This work is regional therapy for many scarred by the South’s unwillingness to investigate the region’s history.

But it’s hard for history alone to stop homicides.

Mr. Johnson’s work in Nashville and Alex City’s slouch toward recovery testify to other common causes of crime: joblessness, distrust, inequality, culture. The South still has deep pockets of rural poverty and, in some areas, inept government. Those require a reckoning of their own.

On an afternoon in April, Mr. Shaw is speaking to employees in his appliance shop, founded by his uncle 90 years ago and now covered in vines. Several men languor in the sun on makeshift stools outside a garage bay. The shop is only a short drive from the old city hall, the white office building where Mr. Shaw fought.

It’s been seven years now. And with distance, he concedes that the stress of managing Alexander City’s decline made him more hostile. But that’s not an apology. He doesn’t regret what he did.

“That’s a Southern thing, but it’s also an American thing,” he says. “Would I do it again? Yes, I would.”

Debt deal reinforces Biden as consensus builder

For President Joe Biden, aiming for the political center defined his career. Achieving a debt deal in an era of hyperpolarization and divided government shows that the old ways can still work.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

There’s a reason Joe Biden won the Democratic nomination for president back in 2020: As a Washington denizen known for his decades of governing experience, he could bring the capital back to something resembling normal after a norm-busting Trump presidency, his champions asserted.

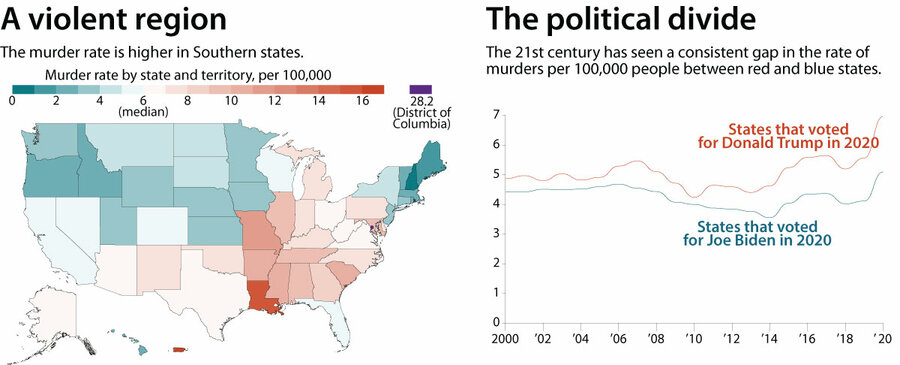

Today, that argument seems to be playing out. After weeks of high-wire negotiations and brinkmanship, strong bipartisan majorities in both houses of Congress have approved a deal that suspends the statutory limit on federal debt payments – the “debt ceiling” – until 2025 and also curbs some federal spending.

An unprecedented and catastrophic default on the national debt has been averted.

For President Biden, aiming for the political center and seeking consensus have defined his political career since his first election to the Senate from Delaware in 1972. Now, in an era of hyperpolarization and newly divided government, he’s shown that the old ways can still work.

“There’s a rhythm to governing, and I think this is the start of that rhythm,” says former seven-term GOP Rep. Tom Davis of Virginia.

Debt deal reinforces Biden as consensus builder

There’s a reason Joe Biden won the Democratic nomination for president back in 2020: As a Washington denizen known for his decades of governing experience, he could bring the capital back to something resembling normal after a norm-busting Trump presidency, his champions asserted.

Today, that argument seems to be playing out. After weeks of high-wire negotiations and brinkmanship, strong bipartisan majorities in both houses of Congress have approved a deal that suspends the statutory limit on federal debt payments – the “debt ceiling” – until 2025 and also curbs some federal spending.

An unprecedented and catastrophic default on the national debt has been averted.

For President Biden, aiming for the political center and seeking consensus have defined his political career since his first election to the Senate from Delaware in 1972. Now, in an era of hyperpolarization and newly divided government, he’s shown that the old ways can still work.

“There’s a rhythm to governing, and I think this is the start of that rhythm,” says former seven-term GOP Rep. Tom Davis of Virginia.

The former congressman sees both Mr. Biden and House Speaker Kevin McCarthy as winners, setting a precedent that could pay dividends in the future: “The trust factor gets better after this. They’re both learning how to deal with each other. This was a major test.”

Mr. Davis points to 1997 as the model. Then, Republican House Speaker Newt Gingrich and Democratic President Bill Clinton beat the odds and compromised to balance the federal budget – setting up a brief period of budget surpluses that disappeared after 2001.

“On some days you’re going to throw insults back and forth, you’re going to attack,” he says. “And on the next day you’re going to be able to cut a deal.”

Today, Speaker McCarthy’s developing relationship with President Biden is a source of fascination – “two Irish guys who don’t drink,” as one McCarthy ally put it. Both, too, have a high tolerance for political pain. In January, it took Speaker McCarthy a record 15 votes in the House to reach the chamber’s top job. Mr. Biden finally won the presidency in 2020 after multiple tries.

Both, too, have long been underestimated, which may have worked to their advantage in the debt ceiling negotiations. For the octogenarian Mr. Biden, the constant suggestions in conservative media that he’s not mentally competent may have led to false confidence among Republicans that he could be played. Mr. McCarthy is sometimes accused of not being all that bright.

But it’s Mr. Biden who, arguably, had more to lose if the nation had actually gone into default. Presidents live and die by the economy, and the buck would have stopped with him in the event of a global economic meltdown triggered by the United States.

In the end, Mr. Biden didn’t have to give up much to get a bipartisan deal, compared with original GOP demands that entailed $4.5 trillion in spending cuts over 10 years. The deal that passed Congress claws back unspent COVID-19 relief money, trims increased spending for the Internal Revenue Service, adds a work requirement to some receiving food aid, ends the pause on student loan repayments, and green-lights completion of a controversial pipeline.

The deal “showed Joe Biden being a serious person and serious president, with little drama, which is exactly why the country elected him,” says Elaine Kamarck, a former senior official in the Clinton White House. “Meanwhile, there’s Trump with one drama after another.”

Kudos for dealings with Speaker McCarthy

Mr. Biden had more good news to tout Friday, with the latest employment report showing robust growth – 339,000 new jobs in May – and dampening fears of a recession. His tumble on stage Thursday at the Air Force Academy in Colorado, where he tripped on a sandbag, created exactly the optics he doesn’t want: an elderly president looking unsteady right as his reelection bid ramps up.

But on matters of substance, Mr. Biden wins kudos for his dealings with Mr. McCarthy – even if the president got off to a bit of a shaky start.

“I was a little surprised at the outset that he wasn’t willing to negotiate earlier on,” says G. William Hoagland, senior vice president at the Bipartisan Policy Center and a former senior GOP Senate aide in the 1980s and 1990s. “I felt he was being pushed a little bit by some of his more liberal [Democratic] members to stand fast and push the Republicans to the point where they would somehow cave.”

He suspects part of Mr. Biden’s initial posture – “no negotiating” – came out of a belief that Mr. McCarthy wouldn’t be able to pass his own budget. Once that happened, a sign of the new speaker’s own unexpected strength, Mr. Biden knew it was time to deal, and his instincts as a former senator of 36 years kicked in.

“He realized he had to negotiate and work, particularly, with the House Republicans,” Mr. Hoagland adds. “By the end, it was the old Biden as I remember him.” And of course, nothing helps deal-making in Washington like a deadline.

William Galston, a domestic policy adviser in the Clinton White House, applauds the president for showing restraint during the negotiations, and in particular, for refusing to declare victory – loudly and publicly – after he had reached a deal with Mr. McCarthy, so as not to complicate the task of getting the legislation through Congress.

“All of that is the fruit of his experience” as a senator, Mr. Galston says. But his strength as a backroom negotiator is belied at times by an unwillingness to provide a public explanation, he adds. Thus, the importance of a speech Mr. Biden delivered from the Oval Office on Friday evening.

The president praised Speaker McCarthy and what he called a respectful collaboration, emphasized the importance of unity and bipartisan compromise to the nation, and said the deal protected America’s fiscal and economic strength. “No one got everything they wanted but the American people got what they needed,” President Biden said.

“He genuinely believes – and he’s one of the last people in Washington to believe – in the serious possibility of serious bipartisanship,” Mr. Galston says. And that, he adds, is important to convey to the public.

Editor’s note: A new penultimate paragraph was added to this article after President Biden’s address Friday evening.

Patterns

At 100, Henry Kissinger asks tough questions of America

Henry Kissinger, 100 last weekend, posed America’s key foreign policy conundrum 30 years ago. The U.S. can neither withdraw from the world nor dominate it. That remains unresolved.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

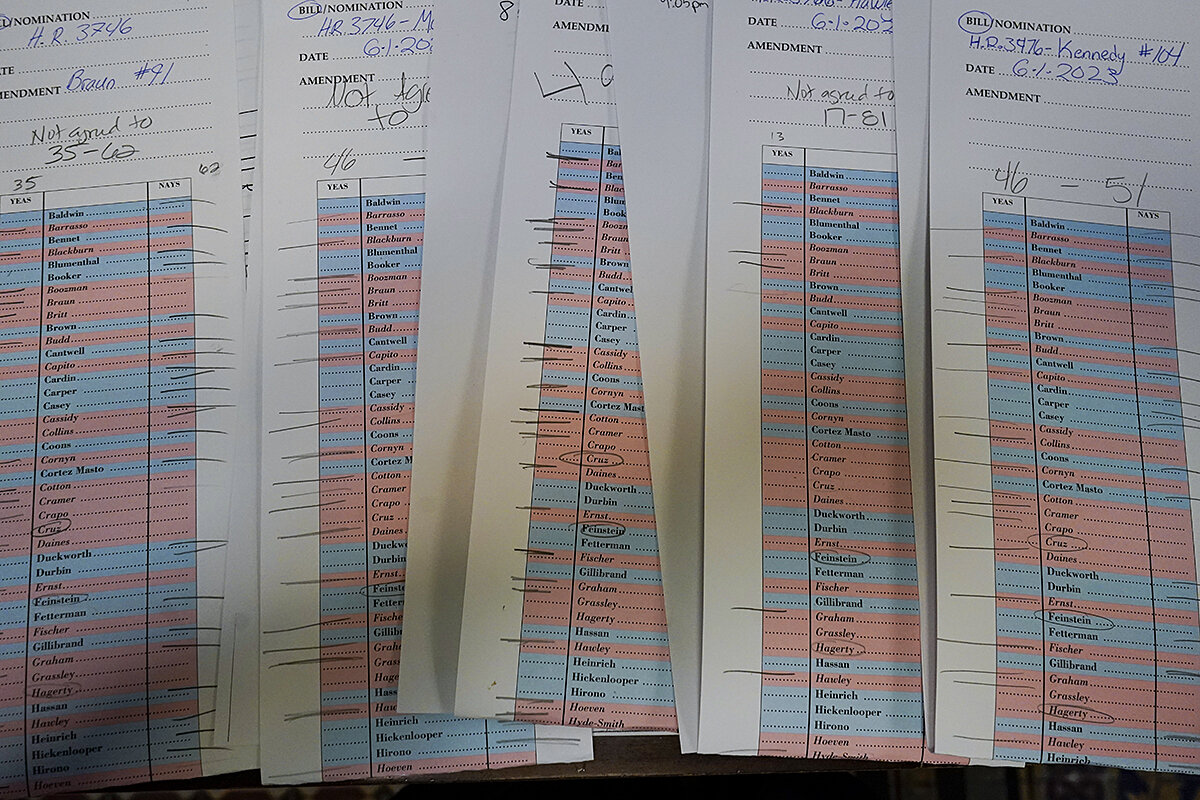

Henry Kissinger turned 100 last weekend, warning, with undimmed fervor, of two contemporary threats to an increasingly unstable world: the standoff between America and China, and the growing power of artificial intelligence.

How those challenges might be met could well hinge on a deeper question that Mr. Kissinger first flagged three decades ago: how the United States chooses to engage in a “new world order” that it can no longer design or dominate, as it did during the years following World War II.

What does America, still the leading power, want in the world? Can it break out of its “historical cycle of exuberant overextension and sulking isolationism,” as Mr. Kissinger puts it?

And, beyond dealing with inescapable crises, can any U.S. president forge and sustain a cohesive foreign policy, now that the post-World War II bipartisan consensus in Washington has collapsed?

With America’s rivals and allies all watching keenly, the U.S. has yet to resolve the core conundrum that Mr. Kissinger identified in his 1994 book “Diplomacy” – that in navigating this evolving new order, “the United States can neither withdraw from the world nor dominate it.”

Joe Biden seems to share that analysis. But it is by no means clear that his potential successor, Donald Trump, does.

At 100, Henry Kissinger asks tough questions of America

Henry Kissinger turned 100 last weekend, warning, with undimmed fervor, of two contemporary threats to an increasingly unstable world: the standoff between America and China, and the growing power of artificial intelligence.

Yet how those challenges might be met could well hinge on a deeper question that Mr. Kissinger first flagged three decades ago: how the United States chooses to engage in a “new world order” that it can no longer design or dominate, as it did during the years following World War II.

What does America, still the leading power, want in the world? Can it break out of its “historical cycle of exuberant overextension and sulking isolationism,” in Mr. Kissinger’s words?

And, beyond dealing with inescapable crises, can any U.S. president forge and sustain a cohesive foreign policy, now that the post-World War II bipartisan consensus in Washington has collapsed?

Mr. Kissinger posed all those puzzles in his 1994 book, “Diplomacy,” which I was rereading as he was blowing out his birthday candles.

He wrote it after the collapse of the Soviet Union. But the “new order” that he envisaged – messier; less tractable; in which influence is shared with China, a possibly “imperial” Russia, Europe, and India – is still being born.

And with America’s rivals and allies all watching keenly, the U.S. has yet to resolve the core conundrum that Mr. Kissinger identified in his book: that in navigating this evolving new order, “the United States can neither withdraw from the world nor dominate it.”

President Joe Biden would argue, with some justification, that – after the “exuberant overextension” of George W. Bush’s 2003 Iraq War and the “sulking isolationism” of Donald Trump – he is showing the kind of international engagement that a changing world demands.

As Exhibit A, he would probably point to Washington’s response to Vladimir Putin’s war on Ukraine – making America the indispensable leader of a policy that has been carefully coordinated, and jointly implemented, with U.S. allies in Europe and beyond.

Yet the centenarian Mr. Kissinger was right, in pre-birthday interviews, to single out two key policy challenges now posing a stress test for Mr. Biden’s foreign policy approach.

First, China. Its assertiveness, power, and influence have grown exponentially since the 1990s. Unlike the Soviet Union during the Cold War years, it is also a major world economic force, second only to America.

Under successive U.S. presidents since early this century, U.S.-China ties have been getting chillier and more confrontational.

And now, unlike U.S.-Soviet ties, they’re being hampered by a near-total absence of regular contacts between senior political and military officials in Beijing and Washington.

The challenge for Mr. Biden, especially amid rare bipartisan enthusiasm for a tougher and more protectionist economic policy toward Beijing, is to find a way to avoid leaving the world’s two major powers without sustained and trusted channels of communication.

That’s where Mr. Kissinger is right to highlight the importance of artificial intelligence – which, if unregulated and unconstrained, he fears could become the 21st-century equivalent of the nuclear weapons threat during the Cold War.

In Mr. Kissinger’s view, it’s in everyone’s interest – America’s, China’s, and the wider world’s – for Washington and Beijing to work together to try to put AI guardrails in place, as America and Russia did with nuclear agreements in the less complex geopolitical landscape of the Cold War.

Given the tension and mistrust in U.S.-China ties of late, that may not be easy. Yet, there are growing signs of concern on both sides of that divide about AI.

A number of leading Western technology industry figures this week declared that mitigating AI’s risks should be made “a global priority” on a par with preventing nuclear war. And on Tuesday Chinese leader Xi Jinping called for “dedicated efforts to safeguard ... the security governance of internet data and artificial intelligence.”

Mr. Biden does seem to share Mr. Kissinger’s view that America needs to engage with its Chinese rival, especially on issues neither can solve alone. Indeed, the U.S. president has been making that argument to Beijing as he seeks to revive communication and cooperation despite the increasingly confrontational tone of U.S.-China relations.

But whether the Biden administration’s vision of U.S. engagement in a changing world lasts could depend on one of the still-unresolved challenges Mr. Kissinger wrote about in the 1990s.

It’s the lack of the kind of domestic consensus about America’s role in the world that U.S. presidents enjoyed in the post-World War II years.

That bond was damaged by the Vietnam War. In recent years, it has been eroding further.

Repairing it is likely to prove especially hard with the approach of the 2024 U.S. presidential election. Already, some voices in the Republican Party, notably its current presidential frontrunner, Mr. Trump, have questioned America’s active support for Ukraine.

All of that has been feeding uncertainty among both allies and foes over just how durable the Biden administration’s reengagement of America in world affairs will prove.

It seems clear that Mr. Biden has broadly accepted Mr. Kissinger’s bottom-line analysis: that the United States can neither withdraw from the world nor dominate it.

But that is less obviously true of Mr. Trump, President Biden’s predecessor, and, conceivably, his successor.

Podcast

‘Woke’? Existential? A political football with young lives at its core.

Few issues are as fraught as those around medical intervention and early gender identity. Even the language is strewn with mines. For some politicians, that makes it easy to weaponize. Our reporter set out to supply some context.

How can a writer apply fairness to a debate on an issue that one side views as an urgent need, the other as delusion?

Monitor correspondent Simon Montlake headed to Missouri to take a closer look at efforts there and in other red states to restrict gender transition for minors, which is emerging as a key issue in the 2024 campaign.

“It’s clearly an animating point on the right of American politics,” he says on the Monitor’s “Why We Wrote This” podcast. At least 16 states now ban or restrict medical interventions such as puberty blockers for those under 18.

There is also a debate within the medical community on the long-term impact of such treatments – and what may be contributing to the surge of young people seeking them. Some European countries are revising their protocols to ensure adequate mental health care before opting for medical interventions.

“There is genuine concern and frustration about how quickly transgender issues seem to be pushed into the mainstream,” Simon says. “But a more strategic thought I had is that this is a great issue to campaign on. It unites the conservatives; it also divides the other side.”

But for the families of trans children, navigating this relatively new issue can be a “wrenching decision.” “I found that talking to the parents gave me a very moving insight into the dilemmas they face,” he says, “and also how they feel about their children being made into a political football.” – Gail Russell Chaddock and Jingnan Peng

You can find show notes, links, and a transcript here.

The Politics of Trans Care

What a web it weaves: ‘Spider-Verse’ spins a high-flying tale

Why go see yet another version of everyone’s friendly neighborhood wall-crawler? In addition to captivating animation, this Spider-Man understands the importance not just of responsibility, but also of consequences.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

With great power comes great responsibility.

It is the phrase that defines a character and quite possibly even a comic universe. Stan Lee and Steve Ditko’s creation of Spider-Man back in the 1960s gave us Marvel’s most relatable hero, due to his awkwardness and the adversity he regularly experienced, whether in his personal or powered-up life.

The phrase took something personal and made it aspirational. There was one unspoken rule: Great power doesn’t just come with great responsibility. It comes with great sacrifice.

The new “Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse,” wants to see just how tensile that tenet is. What results is a masterpiece – a triumph of innovation and diversity that just might be the best comic book movie I’ve ever seen.

What a web it weaves: ‘Spider-Verse’ spins a high-flying tale

With great power comes great responsibility.

It is the phrase that defines a character and quite possibly even a comic universe. Stan Lee and Steve Ditko’s creation of Spider-Man back in the 1960s gave us Marvel’s most relatable hero, due to his awkwardness and the adversity he regularly experienced, whether in his personal or powered-up life.

The phrase took something personal and made it aspirational. There was one unspoken rule: Great power doesn’t just come with great responsibility. It comes with great sacrifice.

The new “Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse,” wants to see just how tensile that tenet is. What results is a masterpiece – a triumph of innovation and diversity that just might be the best comic book movie I’ve ever seen.

My perusal of source material has been vast, from countless comic books to hours of animated series. “Spider-Man,” which aired on Fox from 1994 to 1998, was a go-to in my youth. I remember how the show masterfully spun together storytelling and larger-than-life action. At the time, it, “Batman: The Animated Series,” and “X-Men: The Animated Series,” were industry standard-bearers.

“Across the Spider-Verse,” which opened Thursday, doesn’t just challenge its most iconic phrase – it also challenges what we have seen in previous silver-screen incarnations of Spider-Man.

It picks up right where 2018’s “Into the Spider-Verse” left off, centering its story on the budding friendship between Miles Morales and Gwen Stacy. The plot moves with a teen’s pace, quickly through adolescence and puberty to the fringes of adulthood and responsibility. Both Miles and Gwen aren’t just doing battle with supervillains, but also with overbearing parents.

Saying that the movie brings the comic book to life, or that it jumps off the page, doesn’t do it justice. The Spider-Verse moves fast enough for our attention-deficit age, while also honoring the time-honored traditions of storytelling.

Now, imagine that story reinforcing itself from the perspectives of various griots, or chroniclers, or for the sake of this exercise, spinners. This is where the Spider-Verse series weaves in beautiful diversity, offering an array of Spider-types, unique in nationality, in ideology, in literal construct. The 2018 film came complete with a Spider-robot and a Spider-pig, but the sequel takes the absurdities to another level.

When I saw the legion of Spider-men and Spider-women who chase after Miles in the trailer, I thought about the strands of the Spider story that got my attention. At first, it was the notion of a nerdy kid whose superpowers turned his world upside down. Later, it was the fashion sense of our wall-crawling hero that not only inspired my favorite comic book cover, but a foreshadowing phrase: “Amid the chaos, there comes a costume.”

That versatility doesn’t just remind me of Peter Parker, but also of another famous photojournalist – Gordon Parks. There was nothing he couldn’t do, whether it was photography, writing, directing, or composing. The director of the iconic blaxploitation film, “Shaft,” also composed music for the series.

Spider-Man isn’t without its own infectious jingle. “Is he strong? / Listen, bud – he’s got radioactive blood,” goes the theme from the often-reprised 1967 Spider-Man cartoon. This movie is just as captivating, whether it’s one’s first time engaging with the old webhead, or a tried and true believer who will appreciate the vast number of Easter eggs that the film provides.

With charisma, callbacks, and culture, the movie doesn’t just inspire diversity in terms of representation. It also inspires diversity in terms of how we view choice.

“Everyone keeps telling me how my story is supposed to go,” Morales says defiantly during the trailer. “Nah. I’mma do my own thing.”

What this movie ultimately teaches us through the adaptation of an adage is that great power doesn’t just bring forth added responsibility or sacrifice. The gravity of great power shifts our focus from circumstances to consequences.

I’ve watched superhero movies succumb to the pressure of that existential burden – from the latter Matrix movies to Marvel’s Phase Four. “Across the Spider-Verse,” with all its complexities and previous Spider standards, feels free in its development and execution.

And oh, what a web it weaves.

Correction: Isaac Hayes composed both the music and lyrics for the theme song for the original “Shaft.” Gordon Parks, the director of “Shaft,” composed music for additional films in the series.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

The debt deal’s lessons in humility

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

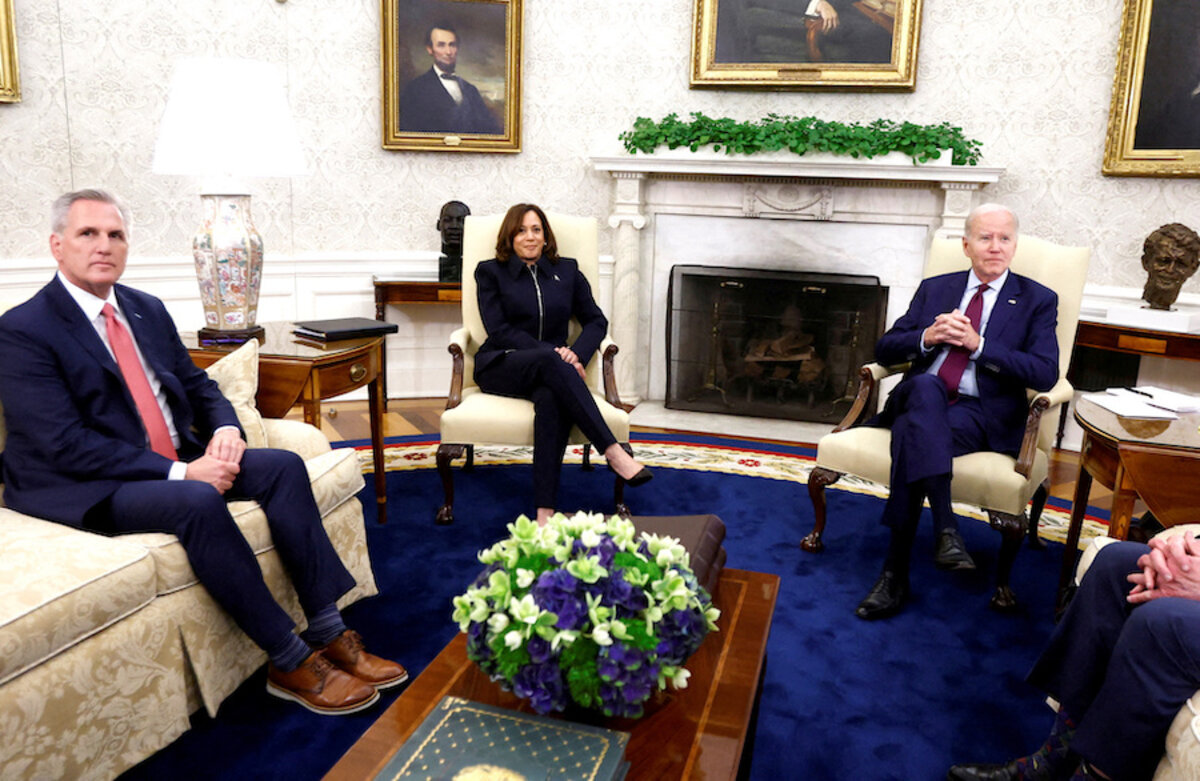

Perhaps there’s a reason the Oval Office in the White House is oval. There’s no sharp corner to retreat to, no straight wall to defend. Voices bounce better off the curved walls, forcing one to listen. How else to explain the debt-and-spending deal, struck over weeks of talks between a Republican House speaker and a Democratic president, that finally passed Congress on Thursday?

Well, the participants inside that hallowed, humbling room have reasons other than the oval architecture. President Joe Biden said that negotiating a compromise to avoid a debt default meant “not everyone gets what they want.” That hints at a willingness to see one’s blind spots, reconsider one’s importance, and expand one’s views to see alternatives. As the president put it, “That’s the responsibility of governing.”

The final compromise crafted in the Oval Office may merely be seen as a balancing of interests, a splitting of differences. Each side “got something.” Yet this rare exercise of bipartisanship in a polarized Washington also needs to be celebrated. The gentleness of oval walls may not have anything to do with it. But gentle meekness might have.

The debt deal’s lessons in humility

Perhaps there’s a reason the Oval Office in the White House is oval. There’s no sharp corner to retreat to, no straight wall to defend. Voices bounce better off the curved walls, forcing one to listen. How else to explain the debt-and-spending deal, struck over weeks of talks between a Republican House speaker and a Democratic president, that finally passed Congress on Thursday?

Well, the participants inside that hallowed, humbling room have different reasons than the oval architecture. President Joe Biden said that negotiating a compromise to avoid a debt default meant “not everyone gets what they want.” That hints at a willingness to see one’s blind spots, reconsider one’s importance, and expand one’s views to see alternatives. As the president put it, “That’s the responsibility of governing.”

The traditional dynamics of power – threats, brinkmanship, intellectual hubris – certainly played a role during the political showdown. Yet one key negotiator in the room, House Republican Patrick McHenry, experienced an open-mindedness and a presumption that the other person might hold an element of truth. “What I saw in the Oval Office ... was a willingness to engage with each other in a sincere way – air disagreements, listen,” he told Reuters.

Listening usually means self-effacement, even a letting go of the fear of being duped. Here is what Mr. Biden said of Speaker Kevin McCarthy: “I think he negotiated with me in good faith. He kept his word.” Within the House chambers, too, Democratic Minority Leader Hakeem Jeffries told the Monitor that he and the speaker “continue to have open, honest, consistent communication.”

Humility is far more than modesty. It is more than seeing one’s limits. It is being open to the possibility of shared wisdom.The final compromise crafted in the Oval Office may merely be seen as a balancing of interests, a splitting of differences. Each side “got something.” Yet this rare exercise of bipartisanship in a polarized Washington also needs to be celebrated. The gentleness of oval walls may not have anything to do with it. But gentle meekness might have.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Needed: Less ‘I’ and more God

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Bob Cochran

When we set aside self-reliance and yield to how divine Spirit is guiding what to say and do, we find greater fulfillment and success.

Needed: Less ‘I’ and more God

Sometimes it’s tempting to make a distinction between things we need God’s help for, and things we’re good at and can handle on our own. But whatever abilities or knowledge we appear to possess can’t compare to the infinite capacities possessed by God, omniscient Mind, who created all and knows all. The point is made very succinctly by Mary Baker Eddy in “The First Church of Christ, Scientist, and Miscellany,” where she writes, “Attempt nothing without God’s help” (p. 197).

I learned this lesson some years ago, when I was asked to participate in a conference. My task was to give a short talk and then lead a discussion. But when the time came to break into smaller groups, I was surrounded by a dozen empty chairs.

I hadn’t even had the chance to be boring! The same format was planned for the next day, and I dreaded another humiliation. As a student of Christian Science, I’ve found that prayer is the most effective approach to any challenge, so it was natural to turn to God for guidance.

First, I asked myself whether I honestly thought I had anything worth sharing. The answer was yes; I had experience and expertise that I’d acquired over the years, and I felt I could communicate the relevant concepts reasonably well. That’s when the lightbulb clicked on; as you may have noticed, the previous two sentences contain no less than seven “I”s! The metaphysical course correction was pretty clear: less “I” and more God was needed.

A good starting point for prayer was in Mrs. Eddy’s “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” which says, “The intercommunication is always from God to His idea, man” (p. 284). God, divine Mind, is the only Mind, and therefore the source of all ideas and the ability to communicate them. All of us, as God’s reflection, can and do participate fully in intercommunication, but God alone is the source.

There’s nothing wrong with planning, but human footsteps, while often necessary, are rarely sufficient. There are two especially striking illustrations of this in the Bible. When God tasked Moses with leading the Israelites out of Egypt, the prophet balked, claiming he was too “slow of speech” to be persuasive. God answered, “I will be with you as you speak, and I will instruct you in what to say” (Exodus 4:12, New Living Translation).

Centuries later, Christ Jesus gave similar instructions to his followers: “And when you are brought to trial in the synagogues and before rulers and authorities, don’t worry about how to defend yourself or what to say, for the Holy Spirit will teach you at that time what needs to be said” (Luke 12:11, 12, New Living Translation). My situation was hardly as momentous as the ones described in the Bible, but the same rule applied: God was the source of both the substance and style of the message.

And God would guide everyone to where they needed to be in order to hear the ideas they needed to hear. If no one showed up, well, maybe no one needed those particular ideas at that particular time. Either way, the divine Mind was in charge. My only responsibility was to be open to Mind’s direction. I prayed until I felt at peace, confident that God was truly in control.

The next afternoon, when I approached my area at the conference, I was surprised to see that all the chairs were already taken, and a similar number of people were standing behind those chairs. I spoke for 15 or 20 minutes, using some ideas I’d prepared beforehand, and some that came spontaneously. People seemed to be listening attentively; nobody wandered off.

I paused and asked if there were any questions. After a moment of silence, someone said, “You’ve answered our questions before we asked them!” There were nods and murmurs of agreement. It was very clear that the intercommunication had indeed been from Mind, God, and had included everyone.

A beautiful passage on page 89 of Science and Health says, “Mind is not necessarily dependent upon educational processes. It possesses of itself all beauty and poetry, and the power of expressing them. Spirit, God, is heard when the senses are silent. We are all capable of more than we do. The influence or action of Soul confers a freedom, which explains the phenomena of improvisation and the fervor of untutored lips.” That’s the truest approach to communication, and one we can always rely on.

Adapted from an article published on sentinel.christianscience.com, Dec. 1, 2022.

Viewfinder

Don’t worry, bee happy

A look ahead

Thank you for joining us. On Monday, our Ira Porter will look at a first-of-its-kind proposal in California. The Golden State is considering guaranteed transfer for community college students. If the plan is approved, students would finally have access to the most selective schools, including the state’s top universities in Los Angeles, Berkeley, and San Diego.