- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usMonitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Cricket just beyond the backyard

Earlier this summer, I watched a construction crew in the field behind our house in Cambridge, Massachusetts. A mechanical digger removed a strip of grass in the middle of the field, and a eureka moment came.

“They’re building a crease,” I told my wife.

She was mystified. But I was elated. A crease is the centerpiece of a cricket pitch. It’s where batters at either end defend their wicket against bowlers. It’s the equivalent of the pitcher’s mound and home plate in baseball, with fielders arrayed around it in 360 degrees. So, when you see a crease on a field, you expect to see cricketers.

I grew up playing cricket in London and it reminds me of home. Today the biggest cricket audience is in South Asia, where big matches can bring cities to a standstill. The sport is also popular in the Caribbean, Australia, and New Zealand.

In the United States, cricket has yet to find a home. But cricket-loving immigrants are trying to change that. On Thursday, the first ball will be bowled in Major League Cricket, a fledgling professional league that’s holding its first tournament. Six teams will compete in 19 matches, played mostly at a former baseball stadium in Dallas. Indian American investors have stumped up the seed money for the competition.

Several U.S. cities already have amateur cricket leagues supported by immigrant communities. Our local field now hosts weekend matches between all-Indian teams. Their cries, and the thwack of balls and bats, fill the morning air. My son watches, intrigued by a novel sport. But he’s sticking to baseball, for now.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Democrats prep shadow presidential campaigns

Some ambitious Democratic governors appear to be laying the groundwork for presidential campaigns in case President Joe Biden can’t run or decides to drop out.

The 2024 Democratic presidential primary race officially features just President Joe Biden and two long shots, lawyer and vaccine skeptic Robert F. Kennedy Jr. and self-help author Marianne Williamson.

But mainstream Democrats with evident presidential aspirations are positioning themselves to run, either in 2024 – in case the octogenarian Mr. Biden can’t run or decides to drop out – or in 2028. This shadow presidential field features mostly popular governors, from California’s Gavin Newsom to Michigan’s Gretchen Whitmer, who have been busy fundraising for Democratic candidates, building national databases of supporters, and raising their profiles.

In some ways, Mr. Biden has only himself to blame for the speculation that he could change his mind on running for reelection. After all, during the 2020 presidential campaign he referred to himself as a “bridge” to a new “generation of leaders” and was generally noncommittal about whether, if elected, he would seek a second term.

As long as Mr. Biden is in the race, “it’s a campaign that has to stay in the shadows,” says veteran political analyst Charlie Cook. “But they have to be ready to pop out of the shadows if the circumstances change.”

Democrats prep shadow presidential campaigns

Gavin Newsom, the Democratic governor of California, is hardly subtle.

He’s been traveling the country – especially red states – stumping for President Joe Biden, helping Democrats raise money, and highlighting liberal values on hot-button topics such as abortion and gay rights.

He’s plowed $10 million into a political action committee to support Democrats. He sparred with Fox News prime-time TV host Sean Hannity for an hour last month. He’s building a national database of supporters. And he’s been attacking top Republicans, from the 2024 primary front-runner, former President Donald Trump, to Florida Gov. (and presidential candidate) Ron DeSantis and Texas Gov. Greg Abbott.

But Governor Newsom insists he’s not running for president himself.

Gretchen Whitmer, the Democratic governor of Michigan, also says she’s not running for president. She, too, has launched a political action committee to help other Democrats, though unlike Mr. Newsom, she’s been sticking close to home. A national co-chair of President Biden’s reelection campaign, she’s attracting attention as if she is a presidential prospect, including a buzzy recent profile in Politico.

Then there’s J.B. Pritzker. The billionaire Democratic governor of Illinois helped Chicago secure the 2024 Democratic National Convention. If Mr. Biden were to suddenly drop out of the race, Governor Pritzker would certainly be seen as a possible contender – though a source close to Governor Pritzker’s team suggests he probably wouldn’t run, out of deference to Vice President Kamala Harris.

Such is the state of the 2024 Democratic presidential primary race – officially featuring just Mr. Biden and two long shots, lawyer and vaccine skeptic Robert F. Kennedy Jr. and self-help author Marianne Williamson.

But mainstream Democrats with evident presidential aspirations are positioning themselves to run, either in 2024 – in case the octogenarian Mr. Biden can’t run or decides to drop out – or in 2028. The “shadow presidential field,” populated by people now in their 50s, is coming into view.

As long as Mr. Biden is in the race, “it’s a campaign that has to stay in the shadows,” says veteran political analyst Charlie Cook. “But they have to be ready to pop out of the shadows if the circumstances change.”

“Newsom is the most blatant,” he adds.

Mr. Newsom, of course, isn’t every Democrat’s cup of tea, with the slick California vibe and an embarrassing pandemic-era episode he may never live down: dining out at the exclusive French Laundry restaurant right after warning Californians not to gather for the holidays.

But in his attacks on leading Republicans – including going after Governor DeSantis for flying migrants to California – Mr. Newsom is demonstrating that he’s a fighter, a quality that voters often like.

“Gavin Newsom has figured out that, in addition to potentially helping his national prospects, it’s a very helpful way of rallying his base back home,” says Dan Schnur, a former Republican strategist based in California. “Not all Democrats here agree on the best solution for housing or education or climate change, but they all agree that they can’t stand Ron DeSantis.”

Still, Governor Whitmer of battleground Michigan may be running a more effective shadow presidential campaign by being less obvious, Mr. Cook says. Her reelection sweep last November, ushering in total Democratic control of her state’s government for the first time since 1983 – and aided by a ballot measure securing statewide abortion rights – may be the best advertisement of her political skill.

Ms. Whitmer, too, may have earned some toughness points, after the FBI cracked a plot in 2020 by a Michigan militia group planning to kidnap her and overthrow the state government.

In some ways, Mr. Biden has only himself to blame for the speculation that he could change his mind on running for reelection. After all, during the 2020 presidential campaign he referred to himself as a “bridge” to a new “generation of leaders” and was generally noncommittal about whether, if elected, he would seek a second term.

One longtime Democratic strategist, speaking anonymously in order to be candid, says that for prominent Democrats, “it’s a smart move to keep longer-term options open” – i.e., lay the groundwork for 2028. As for a 2024 scenario in which Mr. Biden ends up not running, “Vice President Harris would presumably lead the ticket,” this strategist says. “Others should defer to her.”

But many outside observers aren’t so sure, seeing a long list of potential Democratic presidential prospects who might choose to run in a Biden-less 2024, including senators and others who ran for the 2020 nomination – as well as some fresh faces, such as the new governor of Pennsylvania, Josh Shapiro.

Mr. Cook, for one, doesn’t see ambitious Democrats deferring to Ms. Harris in the event Mr. Biden ends up not running. “I don’t think she’s a pushover, but I don’t see many staying out because of her,” he says.

Ms. Harris’ early struggles as vice president have been well documented, some of her own making, and some not. Supporters say she faced a steep learning curve, with a portfolio of tough issues, including the southern border, and extra scrutiny as a woman of color.

But Mr. Biden has stuck by Ms. Harris, making her his administration’s lead advocate on reproductive rights – an issue she knows well and that is highly energizing for Democrats – and featuring her prominently in his reelection launch video. Key supporters, too, are swinging into action. The group Emily’s List, which helps elect women in favor of abortion rights, has launched a $10 million campaign to boost Ms. Harris’ public standing.

The vice president is already popular with Black voters, a core Democratic constituency, at 64% approval in a recent Economist/YouGov poll.

Overall, though, Ms. Harris – like Mr. Biden – suffers from low job approval ratings. Both are at around 40%.

“Part of the problem is that the vice presidency is a terrible job,” says Chris Galdieri, a political scientist at Saint Anselm College in Goffstown, New Hampshire. “When the president is unpopular, the vice president is unpopular.”

Beyond the low job approval, Ms. Harris also has high negatives. A recent NBC News poll found her with 32% positive and 49% negative ratings among registered voters, for a net negative of 17 percentage points – a record for that poll.

Add to that the fact that Ms. Harris is the understudy to an older president who at times can appear less than physically robust. Republicans are certain to go after her as the 2024 race heats up, essentially arguing that reelecting Mr. Biden risks winding up with President Harris.

The good news for Democrats heading into 2024 is that party leaders are united around the Biden-Harris ticket. It’s the Republicans who have a big, messy primary field, with a highly controversial front-runner, Mr. Trump. Usually, the saying goes, it’s the Republicans who fall in line.

Democrats are also demonstrating that they have a “bench.” Not only are there alternate candidates seemingly ready to go for 2024; if need be, there’s a growing list of prospects for 2028, including Governor Shapiro and Gov. Wes Moore of Maryland, the nation’s only Black governor.

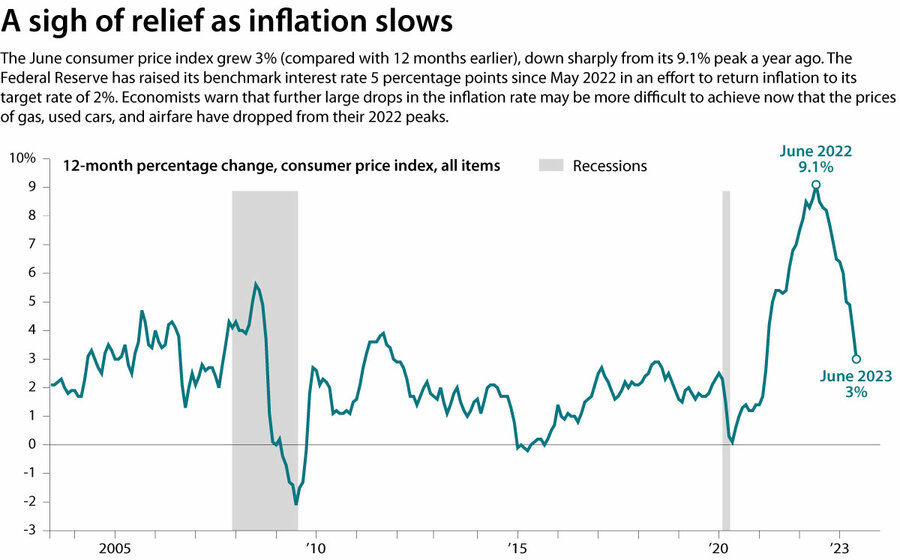

Graphic

US consumers get welcome news

Inflation, long a sore spot for U.S. consumers, showed signs of improvement in the latest Department of Labor report. We have a chart by Jacob Turcotte that puts the progress in context.

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics

African tech workers press social media giants for better conditions

Tech giants like Facebook and YouTube have been accused of taking advantage of weaker labor laws in Africa. Now content moderators are using legal avenues to win fair pay and support.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

As a quality analyst for ChatGPT, Mophat Okinyi read hundreds of descriptions of pedophilia and incest every day, in order to filter them from the artificial intelligence website. He earned $1.50 an hour.

This work left him so traumatized that he eventually separated from his wife. “If you put so much dirty content in your mind, it changes you,” he says.

Mr. Okinyi is among 200 Kenyan content moderators working for tech powerhouses, including Facebook and TikTok, who hope to form a union. Their key goal is to force tech corporations to provide adequate mental health care and fair pay for everyone who works for them – including employees like them, who are outsourced in countries like Kenya that supply quality labor at cheap prices.

Tech giants have long been criticized by workers undertaking this grueling job. Facebook’s parent company, Meta, faces lawsuits brought by content moderators in Kenya accusing it of union busting and insufficient psychological support, among other infringements. Meta is currently appealing a decision that it is the content moderators’ “true employer” and therefore liable.

“If Facebook is held the true employer of these workers, then the days of hiding behind outsourcing to avoid responsibility for your critical safety workers are over,” says Cori Crider of FoxGlove, a London-based legal nonprofit that’s supporting the moderators in one of the cases.

African tech workers press social media giants for better conditions

Mophat Okinyi hates remembering the job he used to do for ChatGPT.

For about $1.50 an hour, he read hundreds of descriptions of pedophilia and incest for the artificial intelligence platform every day. As a quality analyst, his job was to confirm that his subordinates had read and classified potentially harmful content correctly.

"Some of these things are very shocking," says Mr. Okinyi. "We shouldn’t even talk about some of these texts."

The work left him so traumatized, he says, that he drifted apart from his family and eventually separated from his wife. “If you put so much dirty content in your mind, it changes you,” he says.

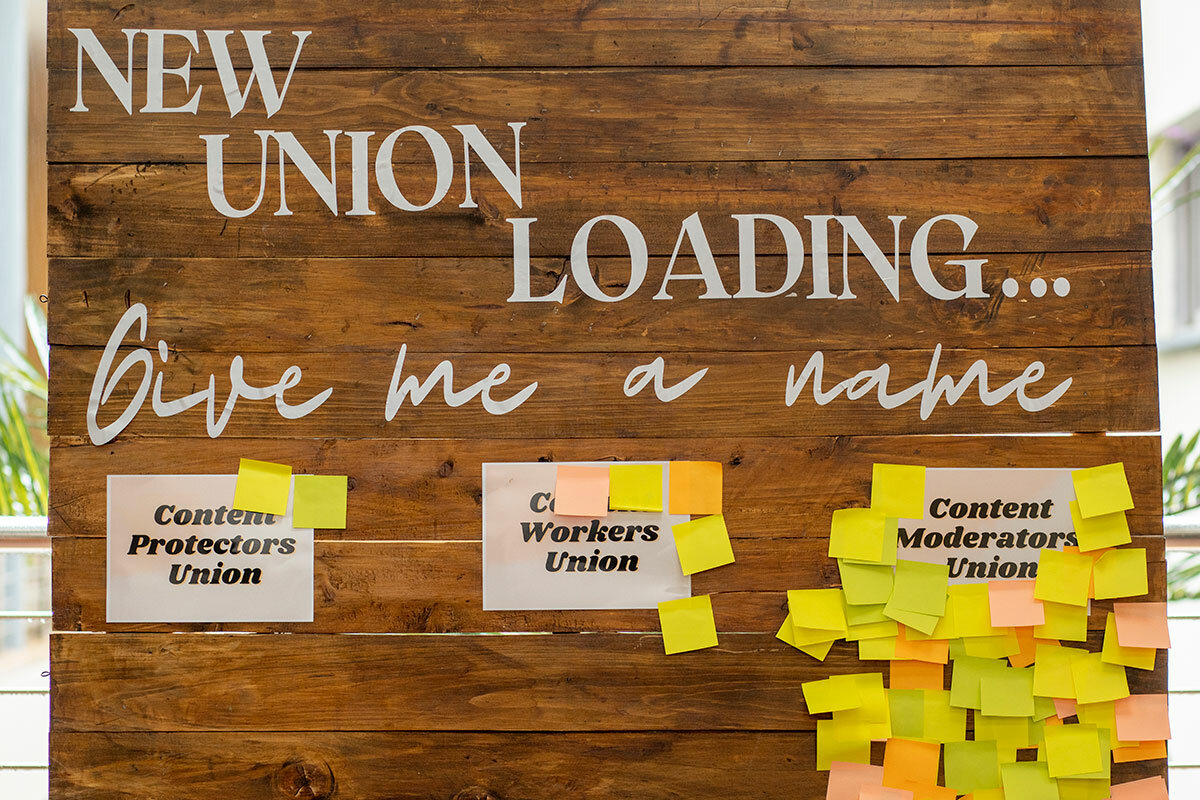

Now, Mr. Okinyi and some 150 other content moderators working for tech powerhouses, including Facebook and TikTok, hope to form a union to improve their pay and working conditions.

“We're trying to make this job safe for those who will do it in future and those who are doing it right now,” says Mr. Okinyi.

Their decision to unionize shines a spotlight on the way tech giants use human labor in Africa where, through outsourcing, they hire hundreds of people to remove harmful content from their platforms. African content moderators hope to force tech corporations to provide adequate mental health care and fair pay for everyone who works for them – including non-traditional employees such as themselves.

“Unionization signals that gig work rights are labor rights, and workers deserve the protections provided by law in this field,” says Nanjira Sambuli, a Nairobi-based tech and international affairs fellow at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

Since last year, Facebook’s parent company, Meta, has been facing lawsuits brought by content moderators in Kenya accusing it of union busting, wrongful terminations and insufficient psychological support, among other infringements. In one case, Meta claimed it was not the moderators’ employer, and was therefore not liable. The court ruled Meta was the “true employer” and the “owner of the digital work of content moderation.”

“That’s the most significant labour rights decision about content moderation I have seen from any court anywhere,” says Cori Crider, co-founder and director of Foxglove, a London-based non-profit that’s providing legal advice to the moderators. “If Facebook is held the true employer of these workers, then the days of hiding behind outsourcing to avoid responsibility for your critical safety workers are over.”

But the decision isn’t set in stone yet, as Meta awaits the outcome of an appeal.

Outsourcing responsibility

For years, tech platforms have faced intense criticism around the world for failing to filter divisive content. In Africa, Facebook came under fire last year for alleged inaction over hateful material that eventually incited violence during the war in northern Ethiopia. A study last month by Global Witness found extreme and hate-filled ads were approved by YouTube, Facebook and TikTok in South Africa, where xenophobic violence has flared up in recent years.

As a result, tech powerhouses have invested heavily in removing material including hate speech, misinformation and incitement to violence from their platforms. Many of the workers who undertake this vital but gruelling task are hired through outsourcing companies and are based in countries like Kenya, India and the Philippines, which supply quality labor at cheap prices.

In Nairobi, a regional tech hub, outsourcing companies bring talent from numerous African countries to moderate work in different African languages. They include Sama, a San Francisco-headquartered company, which has contracted workers for Facebook and ChatGPT. Majorel, headquartered in Luxembourg, hires labor for Facebook and TikTok.

Global tech companies believe that by outsourcing, they can escape responsibility, says Odanga Madung, a senior researcher at the Mozilla Foundation in Nairobi, whose work focuses on the impact of tech platforms in Africa.

“Irresponsibility has always been good business in the capitalist contexts," he says. “Taking care of people is expensive, more so if you're exposing them to graphic content on behalf of your users.”

Accusations of exploitation of content moderators are not unique to Africa. Moderators in the US and Ireland have in the past sued Facebook for mental health issues related to their work. In Germany, a Berlin-based trade union called Verdi has recently been helping content moderators for TikTok and Facebook to unionize.

But the move by African workers to form a union is a novel approach outside the West. At the top of members’ list is having regular, professional mental health checkups, and having their pay standardized with those of their peers across the world.

After graduating from university, Mr. Okinyi joined Sama in Nairobi in 2019 for his first job. He worked on various projects for different foreign tech companies, doing data labeling, product classification and other tasks. But it was his content moderation work for ChatGPT, starting in 2021, that affected him in unforeseen ways.

ChatGPT is a chatbot that takes in a user’s question then, using a language model created from words from the web, provides an answer. Critics say its reliance on mining the internet makes it vulnerable to toxic material.

For the six months that he worked on ChatGPT, Mr. Okinyi’s work began early, ended late, and left him emotionally drained.

Every day at work, he read some 700 texts about child sexual abuse and flagged them according to their severity. Over eight-hour shifts of reading and labeling this material, he enabled ChatGPT to filter out harmful requests.

Although Sama provided counselors, Mr. Okinyi says, productivity demands at work meant he and other workers barely had time to see them.

OpenAI, ChatGPT’s developer, didn’t respond to a request for comment.

The situation was equally appalling for Facebook content moderators at Sama. Kauna Ibrahim, a Nigerian, spent four years watching hundreds of horrific videos every day at work, including sexual abuse and beheadings. For roughly three dollars an hour, she assessed whether the videos were in violation of Facebook’s policies.

During her first year of work, she began suffering panic attacks.

“Some of the images never leave you. You find yourself unable to sleep. Sometimes you dream of what you have seen,” says Ms. Ibrahim, who was a graduate student in clinical psychology at the time. “But because you do it every day, you just survive.”

Sama’s therapists weren’t qualified and didn’t provide enough psychological support, Ms. Ibrahim says. So she resorted to seeking her own therapist.

Sama says it provides “qualified and licensed” professionals to provide therapy for its workers, and that it uses an “internationally-recognized” methodology to set wages for its workers, making its pay “internationally comparable and locally specific.”

Meta declined to comment because of the ongoing lawsuits.

Ms. Ibrahim was among 260 workers whose contracts were terminated in March 2023 after Sama stopped doing work for Facebook. Sama’s work for ChatGPT ended in March 2022, and Mr. Okinyi later moved to Majoral to do customer service work for a European e-commerce company.

On Labor Day this year, both Mr. Okinyi and Ms. Ibrahim sat alongside about 150 other content moderators for Facebook, TikTok and ChatGPT in a Nairobi hotel, and voted to unionize. Mr. Okinyi understands the fight may not be over, but he’s willing to keep pushing with his colleagues to ensure their voices are heard.

“We want to be united because if we're united, we become strong,” he says.

The Explainer

In with a bang: The James Webb Space Telescope after one year

From its first images, the James Webb Space Telescope has delivered breathtaking views of our universe. The range and precision of its observations are also transforming science.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

The pictures have amazed the world. They are also expanding the horizons of science. NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) is special because it is larger and more powerful than its predecessors. It can excel at spectroscopy, the measurement of light wavelengths, which helps reveal physical details like a celestial object’s temperature, age, and speed – and even what the object is made of.

“The joke in the community ... is that a picture says a thousand words, but a spectrum is worth a thousand pictures,” says Massimo Stiavelli, mission leader for the telescope.

Perhaps the greatest surprise so far is that the earliest galaxies were bigger, brighter, and hotter than scientists had predicted.

In addition to viewing distant galaxies, the JWST is also adept at observing planets outside of our solar system, called exoplanets, seen as key to the search for other life in the universe. The telescope’s capacity to observe infrared light can unveil properties of exoplanet atmospheres.

“Is JWST going to give us a definitive ‘No, we’re not alone’? I don’t know,” says Cornell University astronomer Nikole Lewis. “But it’s certainly going to teach us a lot about how to look for life beyond our solar system.”

In with a bang: The James Webb Space Telescope after one year

On the evening of July 11, 2022, U.S. President Joe Biden tweeted a photo. Points of orange, blue, and gold light sparkled and swirled against the black vacuum of space. It was our universe viewed through a new lens.

The image was the first from NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), which has been heralded as a major step in the study of the cosmos.

“The first image from the Webb Space Telescope represents a historic moment for science and technology. For astronomy and space exploration,” Mr. Biden’s tweet read. “And for America and all humanity.”

That photo was soon followed by countless more, each as enthralling as the last. But the photos alone, though dazzling, don’t capture the scientific advances that this successor to the Hubble Space Telescope has already enabled in its first year – or those on the horizon.

“It’s transformational,” John Mather, a senior astrophysicist at NASA, says. “We expect that every page of the new astronomy textbooks will be different because of what we’ve found.”

How does the JWST enable new views of space?

This is a larger, more powerful telescope than its predecessors.

While the Hubble was primarily an imaging telescope, the JWST has a size that allows it to specialize in spectroscopy – the measurement of light in terms of its wavelength. When it comes to astronomy, spectroscopy can reveal many physical details about a celestial object: its temperature, its age, what it’s made of, and how fast it’s moving, for instance.

“The joke in the community ... is that a picture says a thousand words, but a spectrum is worth a thousand pictures,” says Massimo Stiavelli, mission leader for the telescope, which NASA developed with contributions from the European and Canadian space agencies.

Another distinctive feature of the telescope is its capacity to observe light in the infrared range. As a result, it can see objects that are more distant, those obscured by dust clouds, or those that emit only infrared radiation.

A predecessor, Spitzer, was also primarily an infrared telescope, but the much greater size of the JWST means that it can see farther and produce a sharper resolution. This, paired with its spectroscopy prowess, “makes it a completely different machine,” Dr. Stiavelli says.

The impressive size of the JWST’s mirror – with a light-collecting area six times that of the Hubble’s – is made possible by a unique design: It is actually made of 18 smaller mirrors that unfurl to form a monolithic mirror after the telescope’s launch.

What have been its biggest Year 1 discoveries?

Perhaps the greatest surprise so far is that the earliest galaxies were bigger, brighter, and hotter than scientists had predicted.

“We don’t know what the reason is,” Dr. Mather says. “It could be something is weird about the way stars grow. It could be that the early universe is just different enough that we have no idea we missed something. It’s even conceivable that there are weird things about the expansion [of the universe] itself.”

Observations made with the telescope have also offered hints about what Dr. Stiavelli calls “kind of the holy grail of JWST”: population III stars.

These are stars composed only of hydrogen and helium – the elements that physicists say made up the universe after the Big Bang. Population III stars, although not yet conclusively observed, have been proposed as a likely breeding ground for the formation of the other, heavier elements found in stars like our sun, in planets, and even in human beings.

Some observers have argued that they’ve seen evidence of population III stars with the JWST. “It’s very interesting that we see this” high-energy radiation, says Dr. Stiavelli. Still, he maintains a dose of skepticism, citing other possible explanations, such as black holes.

Can the JWST help find life out there?

In addition to distant galaxies, the JWST is also adept at observing planets outside of our solar system, called exoplanets, seen as key to the search for other life in the universe. In particular, the telescope has enabled scientists to analyze many more exoplanets using light in the infrared range.

“The infrared is very, very rich for studying little fingerprints of things,” says Nikole Lewis, a Cornell University astronomer who specializes in exoplanets, “like water and carbon dioxide, and methane and carbon monoxide, and various types of what we call aerosols – clouds and hazes.”

“We, the exoplanet community, are like kids in a candy shop right now,” she adds.

An especially significant discovery was the existence of carbon dioxide in “hot Jupiters,” gas giants that are warmer than those in our solar system. This was at odds with what models had predicted.

“Right now, we’re going through the process of learning about these planets and their atmospheres, and then having to rapidly adapt all of our theories, which have basically been wrong,” Dr. Lewis says. “So that’s been one of the big transformational things, I think, across the board – not only for exoplanets – JWST is really pushing the limits of our theories, and pushing them forward.”

What might come next?

First in the near future may be further discoveries that follow from the telescope’s early results.

“We are on the verge of a major step in understanding in a lot of areas,” says Dr. Stiavelli, pointing in particular to the advances already underway in galaxy and star formation.

There are still other areas where, despite a lack of major advances so far, scientists have reason to anticipate fresh fireworks.

One is “cosmological tension,” which is how scientists characterize attempts to measure the expansion rate of the universe. Different forms of measurement give different results for what’s known as the Hubble constant, the unit of measurement that aims to pin down precisely how fast the universe is expanding.

A number of researchers are using the JWST to refine their measurements of this constant. Based on whether or not it corresponds to previous measurements, a result here could provide further evidence that the tension is a genuine problem, or help resolve it.

Within the field of exoplanet research, much of the focus is on scientists who are trying to measure the atmosphere of rocky exoplanets, similar to Earth. To date, no rocky exoplanet has been confirmed to have an atmosphere.

A result in this area would be a crucial step in the search for other life-forms.

“Is JWST going to give us a definitive ‘No, we’re not alone’? I don’t know,” Dr. Lewis says. “But it’s certainly going to teach us a lot about how to look for life beyond our solar system.”

On Film

Tom Cruise vs. AI: Can last movie star defeat computer villain?

With his latest blockbuster film, Tom Cruise is once again charged with surmounting the impossible and rescuing moviegoing.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

Unlike the latest Indy movie, which overworks the nostalgia angle, or the Daniel Craig “James Bond” movies, which turned 007 into a brutal cipher, “MI” pretty much sticks to the same formula it has engineered for the past three decades: Confront the impossible, vanquish the unvanquishable, and win the day.

The one big twist this time around is that the central villain is not some person or country but a thing – a malevolent sentient artificial intelligence program dubbed “the Entity.” It can stealthily infiltrate any operating system and thereby control the world. With all the unsettling talk these days about AI, this particular species of villainy lends the film a new-style dose of pulp paranoia. Who or what is behind the AI is apparently a matter for Part Two, but the mission – or Mission – here is to head that catastrophe off at the pass.

Tom Cruise vs. AI: Can last movie star defeat computer villain?

Following last year’s smash “Top Gun” sequel, Tom Cruise was championed as the savior of the theatrical moviegoing experience. The title of his new blockbuster, “Mission: Impossible – Dead Reckoning Part One,” could therefore be interpreted literally. Can Cruise once again surmount the impossible and rescue moviegoing from its doomsday reckoning?

Actually, I think all the talk about Cruise saving Hollywood is overblown. The day he appears in a low-budget indie film and that film becomes a smash hit is the day I will believe the movie business is truly back.

But big or small, you still have to deliver the goods, as the mediocre returns for the so-so new “Indiana Jones” movie demonstrate. Directed by Christopher McQuarrie and co-written with Erik Jendresen, the new “Mission: Impossible,” while not peerless entertainment, is a much better sequel. When not bogged down by unnecessary exposition – really, who bothers to follow the plot of these movies anyway? – it’s a giddy, globe-spanning thrill ride.

To reiterate, this seventh installment in the “MI” franchise, which began in 1996, is only Part One. That means it’s basically a glorified teaser. (Part Two reportedly comes out next summer.) But some of the teases can stand – or fly, or speed race – on their own. Whenever the movie went into full throttle, which was about half the time, I gladly settled into that comfort zone of knowing I was being well taken care of by Hollywood action filmmaking at its techno best.

Unlike the latest Indy movie, which overworks the nostalgia angle, or the Daniel Craig “James Bond” movies, which turned 007 into a brutal cipher, “MI” pretty much sticks to the same formula it has engineered for the past three decades: Confront the impossible, vanquish the unvanquishable, and win the day.

The one big twist this time around is that the central villain is not some person or country but a thing – a malevolent sentient artificial intelligence program dubbed “the Entity.” It can stealthily infiltrate any operating system and thereby control the world. With all the unsettling talk these days about AI, this particular species of villainy lends the film a new-style dose of pulp paranoia. Who or what is behind the AI is apparently a matter for Part Two, but the mission – or Mission – here is to head that catastrophe off at the pass.

Enter Cruise’s Ethan Hunt and his Impossible Missions Force (IMF) team: Luther (Ving Rhames), Benji (Simon Pegg), and – belatedly – Ilsa (Rebecca Ferguson). Luther, warning Ethan about the Entity, has the film’s best line: “You’re playing four-dimensional chess with an algorithm!”

The CIA, headed by Ethan’s former handler Kittridge (Henry Czerny), wants Ethan to claim the Entity for the home team. But since Ethan wouldn’t be Ethan without going rogue, he decides instead to destroy it. Along the way, he tangles with the empathy-free Gabriel (Esai Morales), who apparently is on intimate terms with the AI, as well as with Gabriel’s blond henchwoman Paris (Pom Klementieff). The arms dealer White Widow (Vanessa Kirby) makes a return appearance. The most welcome addition is Grace (Hayley Atwell), the ace pickpocket who pockets more than she bargained for.

She reluctantly joins the IMF team, although, as is true of practically all the “MI” movies, as opposed to, say, the Bond films, there is hardly a hint of sexual tension.

The film’s standout centerpiece, breathtakingly performed and shot, is an extended fight scene featuring cutthroat calisthenics between Ethan and Gabriel aboard a runaway Orient Express train. And yes, Cruise does his own stunts, as when he motorbikes off a 400-foot cliff and parachutes onto that train. Sure it’s impressive, but should we really be encouraging such folly? No doubt the movie studio’s insurance company is asking the same question. I shudder to think how Cruise plans to top it in Part Two.

Peter Rainer is the Monitor’s film critic. “Mission: Impossible – Dead Reckoning Part One” is rated PG-13 for intense sequences of violence and action, some language, and suggestive material.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

To fight graft, Mongolia lends an ear

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

Democracies have different ways to tap into the wisdom and virtue of their people, but nothing quite compares to Mongolia’s experience over the past seven months. The landlocked nation of 3.3 million people, squeezed between Russia and China, erupted in protests last December after a massive theft of coal by a state-owned company. Thousands of demonstrators braved freezing weather for days to demand clean governance.

On June 30, after the prime minister declared 2023 as the “year of anti-corruption,” the parliament passed major reforms that would match those in the world’s nations with the least graft. Coal exports, for example, will be sold in transparent auctions rather than via secretive contracts that invite bribery.

“Those protests changed the social environment dramatically,” Justice Minister Nyambaatar Khishgee told The Guardian, “and one thing we understood is that we need to change the relationship between business, politics, and economics.”

What makes Mongolia’s effort stand out is how much leaders now understand they should listen better in the battle against entrenched corruption. “Special attention should be paid to effective participation and effective control of citizens, civil society organizations, and media in anti-corruption activities,” said parliament Speaker Gombojav Zandanshatar.

To fight graft, Mongolia lends an ear

Democracies have different ways to tap into the wisdom and virtue of their people, but nothing quite compares to Mongolia’s experience over the past seven months. The landlocked nation of 3.3 million people, squeezed between Russia and China, erupted in protests last December after a massive theft of coal by a state-owned company. Thousands of demonstrators braved freezing weather for days to demand clean governance.

On June 30, after the prime minister declared 2023 as the “year of anti-corruption,” the parliament passed major reforms that would match those in the world’s nations with the least graft. Coal exports, for example, will be sold in transparent auctions rather than via secretive contracts that invite bribery.

“Those protests changed the social environment dramatically,” Justice Minister Nyambaatar Khishgee told The Guardian, “and one thing we understood is that we need to change the relationship between business, politics, and economics.”

What makes Mongolia’s effort stand out is how much leaders now understand they should listen better in the battle against entrenched corruption. “Special attention should be paid to effective participation and effective control of citizens, civil society organizations, and media in anti-corruption activities,” parliament Speaker Gombojav Zandanshatar said after the reforms were approved. “All over the world, social norms are changing and reforming, and an anti-corruption culture is being formed. ... The government will not fight against corruption alone.”

Mongolia is already well practiced at grassroots consultations. In 2018, it was the first country to officially adopt a technique devised at Stanford University called deliberative polling. Hundreds of Mongolians were chosen at random to sit together over a few days and discuss alternative changes to the constitution. Unlike public polls, referendums, focus groups, town halls, or elections, deliberative polling nudges a wide range of people to respectfully listen to the views of experts and each other, helping to elevate shared concerns and forge a policy consensus. They are encouraged to ask questions more than give answers, to pay attention more than persuade.

Younger Mongolians already rely heavily on Facebook to engage elected officials. “Advances in social networks and technology provide new opportunities,” said Speaker Zandanshatar. “The words ‘justice’ and ‘equal opportunity’ no longer have the characteristics of slogans.”

One key reform awaits Mongolia. Prime Minister Luvsannamsrai Oyun-Erdene wants to double the number of seats in the parliament to allow citizens better access to government and to curb elite corruption. As usual, this potential change to the constitution is going through a lengthy public airing among citizens in the spirit of equality – and with the understanding that wisdom is available to each individual.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Connected with God

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Felix Dross

Our unity with God is not incomplete or conditional but is forever perfect.

Connected with God

Almost anyone who has a computer will have seen this instruction when downloading and installing updates: “Please keep your computer on.” These updates ensure protection against viruses by closing potential security gaps in the software, and they improve the functioning of applications. They can be downloaded anywhere in the world where there is an internet connection.

It occurred to me that there might be parallels between this, and my growing understanding of God and my nature as His spiritual likeness. I was fascinated by the idea that through prayer I could see my connectedness to God anywhere, and get spiritual progress, healings, divine guidance, and protection.

Eventually I recognized that we don’t really need “updates” because, as ideas of God, our divine perfection exists without beginning and without end. The first account of creation in Genesis 1 says, “And God saw every thing that he had made, and, behold, it was very good” (verse 31). In Ecclesiastes we read, “I know that, whatsoever God doeth, it shall be for ever: nothing can be put to it, nor any thing taken from it” (3:14).

If we don’t need updates, what do we need?

We need a clearer understanding of our inviolable and ongoing completeness in God.

Error, or the mistaken concept that God is not All, doesn’t have a temporary type of power that needs to be eliminated. Error is simply what the word says it is – a mistake. Mary Baker Eddy writes in the textbook of Christian Science, “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” “Error is the contradiction of Truth. Error is a belief without understanding. Error is unreal because untrue. It is that which seemeth to be and is not” (p. 472). And elsewhere in this book, “Moreover, Truth is real, and error is unreal” (p. 466).

While the five material senses want to make it seem that error is real, we must not be misled. Truth is the only thing that is true and, as a synonym for God, fills all space; therefore, only Truth exists. Error never existed, since God made all that is made and made it good. Truth destroys our belief in error. It became clear to me that I didn’t need regular updates to express divine Truth.

When Jesus healed, he saw true, spiritual man where others perceived only the physical appearance. He didn’t overlay one picture on another, the spiritual over the material. He saw only Truth and the existence of God’s spiritual idea, man.

Mrs. Eddy writes in Science and Health, “The relations of God and man, divine Principle and idea, are indestructible in Science; and Science knows no lapse from nor return to harmony, but holds the divine order or spiritual law, in which God and all that He creates are perfect and eternal, to have remained unchanged in its eternal history” (pp. 470-471). Because God is All-in-all and is always present, it doesn’t matter where we are or what situation we’re in – we are always connected to God as His reflection, the eternal expression of His divine omnipotence. There can be no security gaps in God’s all-encompassing protection.

A short time later, I benefited from this expanded recognition of divine Truth. I was skiing with my sons, when one of them fell badly. I immediately turned my thought toward God, affirming that there can be no accidents in God, and I listened for spiritual thoughts. God, divine Truth, exposes, dissolves, and destroys error as a mere belief with no power.

Suddenly it occurred to me that I needed to take the final step, and concede that Truth has all strength and power. I had to fully trust Truth to destroy belief in error. This was not just theory. It was the faith and understanding that God is ever present and all-powerful. I was completely calm and confident that Truth possesses and exercises all power to destroy the false belief of an injury. I was able to calm my son, and we joyfully continued our day of skiing. A few days later, all signs that an accident had occurred had disappeared.

We are eternally connected with God. And we can always turn to God in prayer and seek guidance.

Um diesen Artikel auf Deutsch zu lesen, klicken Sie hier.

Adapted from an article published on the website of The Herald of Christian Science, German Edition, March 20, 2023.

Viewfinder

Aftermath of a deluge

A look ahead

Thanks for joining us today. Tomorrow, Howard LaFranchi will look at NATO’s relationship with Ukraine in the wake of today’s meeting.