- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usMonitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

How a radio station changed the world

Can music change the world, as Beethoven claimed? A new book, “Night Train to Nashville,” chronicles how a radio station did just that. In 1946, radio advertising salesperson Gab Blackman spotted an untapped market: Black listeners. He persuaded WLAC in Nashville, Tennessee, to begin nighttime broadcasts of “race music.”

“There were so many African Americans living in rural poverty, and this gave them ... a virtual town square,” says Mr. Blackman’s granddaughter Paula Blackman, who wrote the book.

Mr. Blackman was motivated by profit, not social justice. In his youth, he’d performed in minstrel shows in blackface. But he came to oppose segregation after daily interactions with performers such as Louis Jordan and B.B. King. The Black musicians on WLAC reached ears across the United States, including those of a young Bob Dylan.

“When it really started changing the world is when white teenagers joined that community,” says Ms. Blackman. “They were identifying with the musicians that were writing these lyrics.”

Ms. Blackman says her book isn’t a white-savior narrative. It tells a parallel story of Black businessperson Sou Bridgeforth, whose Nashville nightclub attracted the R&B stars getting airplay on WLAC. The book doesn’t shy away from his experience of Jim Crow-era bigotry.

“The heart of the book is to try and get us to better understand each other [just] as Gab and Sou learn to better understand the other’s culture and upbringing and what made them the way they were,” says the author.

In 1956, a Black college invited white students throughout Music City to a historic concert featuring Little Richard. Other biracial events followed. WLAC’s disc jockeys used coded language to tip off listeners where civil rights protests were taking place. Nashville became the first city in the South to desegregate.

“This is a true account of Nashville at that time,” says Ms. Blackman. “I hope people learn from it.”

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

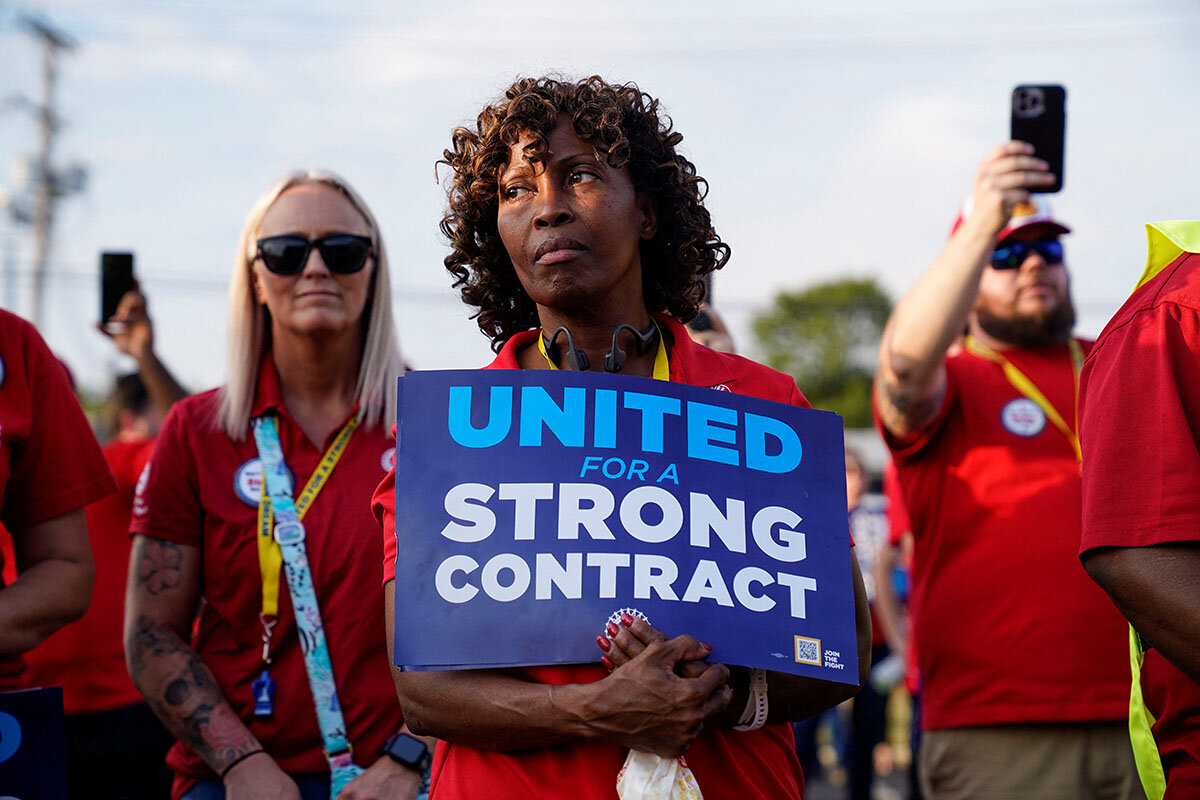

UAW strike expands amid a duel of visions

A weeklong U.S. auto strike hinges on two competing visions at a time of industry upheaval: workers focusing on fairness and companies eyeing the uncertainty of their electric transition. It’s high stakes for both.

At issue in an expanding worker strike against major U.S.-based automakers are two visions of the future: one forward-looking that emphasizes innovation, one backward-looking that emphasizes fairness.

Both visions rest on underlying truths. Both are uncertain and therefore risky.

For the automakers, the challenge is the costly transition to electric vehicles, which is occurring without a clear sense of how fast consumer adoption will occur or how profitable the EVs will become. The workers, for their part, say they bore concessions and hardships to help the Detroit automakers survive the Great Recession, and that restorative boosts in pay and benefits are long overdue.

The bargaining impasse took a somewhat hopeful turn Friday. Although the United Auto Workers union decided to expand its strike against General Motors and Stellantis from two plants to 38, it pointedly did not expand its strike against Ford, citing for the first time progress in talks.

UAW members are watching closely to see if the leadership’s novel strategy works. So are nonunion workers in battery plants that are popping up in the Midwest and the South. If the UAW can show that unionization means much better pay and benefits, these nonunion workers will be more likely to sign up.

Toby Higbie, a labor historian, says, “If they really want to have a chance of organizing in these new industries, [the union] has to show that it can bring home the goods for the workers.”

UAW strike expands amid a duel of visions

At issue in an expanding worker strike against major U.S.-based automakers are two visions of the future: one forward-looking that emphasizes innovation, one backward-looking that emphasizes fairness.

Both visions rest on underlying truths. Both are uncertain and therefore risky. And the stakes for both sides are huge.

For the automakers, the challenge is the costly transition to electric vehicles, which is occurring without a clear sense of how fast consumer adoption will occur or how profitable the EVs will become. The workers, for their part, say they bore concessions and hardships to help the Detroit automakers survive the Great Recession, and that restorative boosts in pay and benefits are long overdue.

The bargaining impasse took a more hopeful turn Friday. Although the United Auto Workers union decided to expand its strike against General Motors and Stellantis from two plants to 38, it pointedly did not expand its strike against Ford, citing for the first time progress in talks. In a statement, Ford confirmed the progress but added there were “significant gaps to close on the key economic issues.”

The auto industry is changing fast. Prodded by federal subsidies and state mandates, carmakers in the United States are committing massive EV investments to help the world curb emissions of heat-trapping gases in Earth’s atmosphere. Their global rivals are doing the same.

Companies like Ford and General Motors face two problems. First, they’re currently losing money on every EV they sell, and the only way to solve that appears to be to scale up massively. Second, American drivers aren’t embracing the technology with the same verve as the automakers – at least not given the vehicle choices and recharging options currently available.

“The companies and the government are ahead of where the public would like to be in this transition,” says Marick Masters, a business professor at Wayne State University in Detroit who follows labor and the auto industry.

For instance, Ford, the No. 2 EV carmaker in the U.S. behind Tesla, cited slow consumer adoption this summer when it pushed back its target to produce 600,000 EVs worldwide in 2023, now saying that won’t happen until 2024.

A long strike that curtails the automakers’ production, especially at plants that produce conventional cars, which still produce big profits, would create an additional challenge for the companies.

On the labor side, a new populist wind is blowing. Autoworkers made humiliating concessions during the Great Recession, when the federal government bailed out two of the three Detroit automakers (Chrysler, now owned by Stellantis, and GM). Now they are determined to win back what they lost, especially in the face of big profits for the automakers and soaring compensation for their CEOs. The union is demanding a 36% rise in income and the elimination of two-tier pay and temporary worker status that at present keep new UAW members from being compensated as well as their longtime counterparts.

But the union is also asking for much more, including the restoration of health care benefits for retirees, traditional pensions that new workers lost, and a program of extended pay and benefits for laid-off workers. And it’s asking for a new perk: 40 hours of pay for 32 hours of work.

“There is a very different kind of spirit right now” in the UAW, says Tod Rutherford, a geography and environment professor who studies labor and the auto industry at Syracuse University in New York. “People are just saying, ‘That’s enough. We’ve got to do something, make a stand.’”

The stakes are especially high for the union leadership. Narrowly elected in an unusual direct vote six months ago, following a corruption scandal at the union, dissident Shawn Fain has taken a much more confrontational approach to bargaining than the traditional leaders who ran the union for decades. He’s also adopted a novel strategy more reminiscent of the 1930s than of more recent times. Instead of striking one automaker and using the contract as a model to settle with the other two, the union has struck a single plant at all three automakers and is bargaining with all three simultaneously.

As long as the strike is short and limited to a few plants, Mr. Fain’s strategy helps the union conserve its $825 million strike fund. The UAW pays striking members about $500 a week. But if the strike drags on and escalates to include most of the plants at all three automakers, the fund will quickly dwindle.

UAW members are watching closely to see how Mr. Fain and his new strategy work. So are nonunion workers in battery plants that are popping up in the Midwest and the South, where “right-to-work” laws make it harder to unionize. If the UAW can show that unionization means much better pay and benefits, these nonunion workers will be more likely to sign up.

“This is about whether or not the union is going to be able to organize those workers in those industries,” says Toby Higbie, professor of history and labor studies at the University of California, Los Angeles. “If they really want to have a chance of organizing in these new industries, [the union] has to show that it can bring home the goods for the workers.”

EV batteries represent an existential threat for the union, a threat on par with the assembly plants foreign automakers set up in the nonunion South starting in the 1980s, says Professor Masters at Wayne State. The shift toward batteries could replace an estimated 30,000 to 40,000 UAW members, mainly those who make engines and transmissions for conventional cars. The Detroit automakers employ some 146,000 UAW workers.

The Explainer

Why China’s ‘miracle’ growth has slowed

Decades of rapid economic growth have made China a central player in the global economy. Now, the tide appears to be turning, but experts say the challenges China faces aren’t that new – nor are they insurmountable.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

While inflation continues to weigh on much of the world, China is facing the opposite problem: deflation. Prices are falling amid an economic slowdown and low consumer spending. The real estate sector is at the center of the slump. Property developers are heavily indebted, major firms have defaulted, and dozens more are on the brink. In the past, China has responded to economic turmoil by lending more money for infrastructure and real estate, a strategy now made difficult by heavy debt.

Meanwhile, local governments are struggling to pay civil servants, and the youth unemployment rate reached 21% before the government stopped publishing the number.

Economists warn of a downward spiral of confidence that could be perilous for the global economy. But not everyone foresees a systemic meltdown.

“There are some real problems in China, but the media observations of what’s been going on are in some ways misplaced,” says Yukon Huang, a senior fellow with Carnegie’s Asia Program. He says the property market is going through an expected period of adjustment, and he sees “huge growth potential” if China can address structural issues, such as amending its household registration system to allow migrant workers in large cities to buy homes.

Why China’s ‘miracle’ growth has slowed

Since opening its economy in the late 1970s, China has achieved impressive levels of economic growth. What’s often referred to as its economic “miracle” lifted over 800 million people from poverty and transformed the lower-income nation into an upper-middle-income powerhouse, making up close to one-fifth of the world’s economic output.

So recent warnings of serious economic troubles in China have caught the world’s attention. In the United States, which was already working to “de-risk” its economy from China’s, President Joe Biden called China a “ticking time bomb.”

Despite alarm bells, economists say China is likely not on the verge of collapse, but this could be a turning point.

What’s happening in China’s economy?

While inflation continues to weigh on much of the world, China is facing the opposite problem: deflation. Prices are falling amid an economic slowdown and low consumer spending. The real estate sector is at the center of the slump: property developers are heavily indebted, major firms have defaulted, and dozens more are on the brink. Prices for existing homes have slid 14% in two years.

Business investment is down, and in July, exports experienced their sharpest decline in three years. Meanwhile, local governments are struggling to pay civil servants, and the youth unemployment rate reached 21% before the government stopped publishing the number.

Economists warn of a downward spiral of confidence that could be perilous for the global economy. But not everyone foresees a systemic meltdown.

“There are some real problems in China, but the media observations of what’s been going on are in some ways misplaced,” says Yukon Huang, a senior fellow with Carnegie’s Asia Program. He says the property market is going through a period of adjustment, given that urbanization has nearly peaked and China’s population is no longer growing. Expectations that consumer spending would rebound as it has in the West post-pandemic are unrealistic, he adds, without the same sorts of stimulus packages.

China’s economy is still expected to grow 4.5% this year, nearly twice the projected global rate.

How did we get here?

The underlying problems hampering China’s economy are not new. The first three decades of China’s so-called economic miracle saw a yearly average growth rate of 10%. Productivity soared thanks to a dynamic environment of “bottom-up” decision-making, says Loren Brandt, an economist at the University of Toronto who specializes in China.

That’s changed since the turn of the century, when China began to re-centralize its economy, a process that has intensified under leader Xi Jinping. Productivity has dropped as local economic decisions are made according to national priorities, especially security and self-sufficiency. “They’re often not based on where the capabilities or returns are,” says Dr. Brandt. Confidence in the government’s ability to make the best economic decisions has waned.

In the past, China has responded to economic turmoil by lending more money for infrastructure and real estate, a strategy now made difficult by heavy debt. The government has cut interest rates slightly, eased borrowing restrictions, and lowered the minimum down payment on homes. Many economists say these measures aren’t enough to correct course.

What does this all mean, for China and the rest of the world?

For the world, it means some slowdown in overall growth, amid lower Chinese manufacturing and import activity. Japan saw exports drop in July for the first time in over two years, as purchases of cars and chips by China, its biggest trading partner, fell. More positively, deflation in China may ease inflation globally by pulling down oil prices and the cost of imports from China.

The long-term concern for China is stagnation. While it’s normal for advanced economies to see growth slow over time, China cannot afford a prolonged slowdown with a gross domestic product per capita of $13,700, less than a fifth of that of the U.S.

“A China which grows at 3% is not able to finance its needs,” says Dr. Huang, referring to social spending, research and development, and security interests. “China needs to grow at something closer to 5%.” He sees “huge growth potential” for China if it can address structural issues, such as amending the hukou (household registration) system to allow migrant workers in large cities to buy homes.

Reliable data on China’s economy can be scarce. But over the years, Dr. Brandt has learned to let China surprise him. “We’ve seen this kind of resiliency ... this ability to solve these problems and move forward,” he says. “I never want to sell them short.”

Native culture on the menu at this Minnesota food lab

For many, traditional recipes offer a way of honoring one’s heritage. Meet the Native chefs helping restore that sense of cultural memory at a new food lab in Minnesota.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Part restaurant and part training center, Minneapolis’ Indigenous Food Lab hopes to provide outreach beyond Native American communities and to strengthen cultural ties within them by reclaiming their cultural ancestry and empowering them to become more self-sustainable. Plans are already in the works for ventures in Montana and South Dakota.

Corn is a staple item, used in tortillas and as part of grain bowls rich with squash, beans, wild greens, and a choice of bison, whitefish, or turkey. The majority of ingredients are sourced from Indigenous communities, and only dishes free from products brought to North America during colonization are served. That means no pork, chicken eggs, wheat, or dairy.

It’s all part of the vision created by Sean Sherman, an Oglala Lakota chef. Mr. Sherman is part of a wave of Native chefs who believe that reclaiming traditional cuisine can help revitalize Indigenous culture. Helping others cook food with ties to their ancestral heritage not only is healthier, they believe, but also can help nourish people’s sense of identity.

“Food is such a cultural identifier. We want to carry our philosophy and values forward of making healthy food and preserving knowledge as much as we can,” says Mr. Sherman, a James Beard Award winner.

Native culture on the menu at this Minnesota food lab

Streams of pearl vapor swirl upward from a rectangular vat in an open kitchen at the Indigenous Food Lab, where Ismael Popoca Aguilar is stirring a mixture of limestone, water, and corn with a thick wooden spoon. The nixtamal preparation has to be just right in order to make hominy – and the perfect tortilla.

“You see? This water is more cloudy. It increases the pH, and the skin of the corn dissolves,” says Mr. Popoca Aguilar, who is Mexican Mestizo and culinary program manager at the Indigenous Food Lab, which opened in June in Minneapolis. “It’s easier to make the dough that way.”

Corn is a staple item on the menu here, used not just for tortillas but also as part of grain bowls rich with squash, beans, wild greens, and a choice of bison, whitefish, or turkey. The majority of ingredients are sourced from Indigenous communities in the United States, and only dishes free from products brought to North America during colonization are served. That means no pork, chicken eggs, wheat, or dairy.

It’s all part of the vision created by Sean Sherman, an Oglala Lakota award-winning chef. Mr. Sherman is part of a wave of Native chefs who believe that reclaiming traditional cuisine can help revitalize Indigenous culture. Helping others cook food with ties to their ancestral heritage not only is healthier, they believe, but also can help nourish people’s sense of identity.

The Indigenous Food Lab, located inside the Midtown Global Market, an indoor multicultural food and crafts market, operates in tandem with the Indigenous-run nonprofit North American Traditional Indigenous Food Systems, which Mr. Sherman created with Dana Thompson.

Part restaurant and part training center, the Indigenous Food Lab hopes to provide outreach beyond Native communities and to strengthen cultural ties within them by reclaiming their cultural ancestry and empowering them to become more self-sustainable. Plans are already in the works for similar ventures in Montana and South Dakota.

“We’re creating a whole new generation of chefs, who can test things out and be role models. We’re not trying to be like the past,” says Mr. Sherman, who also runs the James Beard-awarded Owamni restaurant in Minneapolis. “Food is such a cultural identifier. We want to carry our philosophy and values forward of making healthy food and preserving knowledge as much as we can.”

Stepping in to help

Minnesota’s Twin Cities of Minneapolis and St. Paul have one of the largest urban populations of Native Americans in the U.S. More than any other racial or ethnic group in Minnesota, Native Americans suffer from the highest rates of poverty, which is compounded by injustices in the food system.

Inequalities were heightened during the pandemic as well as in the aftermath of George Floyd’s murder by Minneapolis police officers in May 2020, which saw small businesses around the Midtown Global Market destroyed by fire and riots.

“There are lots of great programs to address food sovereignty, but we continue to struggle with food deserts in urban areas and getting healthy, fresh foods to [Native] communities,” says Mary LaGarde, executive director of the Minneapolis American Indian Center. “There’s a problem of proximity to major grocery retailers. If you have to take public transportation or shop with your kids, it can be really difficult. You’re not going to find those healthier foods at the corner store.”

Even in its early stages, the Indigenous Food Lab stepped in to help. In January 2020, Mr. Sherman had just found a spot to set up the lab when the pandemic hit and his plans were put on hold. Determined to move forward, that June, he and his team instead focused their efforts on food relief, distributing 10,000 meals per week to tribal communities, homeless encampments, and low-income housing districts in the area.

Since opening this past June, the Indigenous Food Lab has continued its outreach, starting by confronting misconceptions about what Indigenous food and culture means.

“People want to say, this is Mexican or this is Native American, but as chefs, borders are more cultural than physical,” says Freddie Bitsoie, a Navajo chef and author, who was chosen as the Indigenous Food Lab’s inaugural chef-in-residence. “We’re trying to bring those borders down and remove the constraints that colonization has created. Our work is to let people know that there was a whole food system in place, not just picking berries.”

Turning sidewalks into gardens?

As part of its mission, the Indigenous Food Lab is also training chefs to teach others about Indigenous ingredients and how to use them. This August, the lab livestreamed its first culinary course, Edible Boulevards, from its open kitchen within the Midtown Global Market. First up? How to make wild rice and beans salad.

“We’re trying to promote turning [sidewalk] boulevards into garden spaces,” says Vern DeFoe, one of the Edible Boulevards teachers. “People are growing things but don’t know what to do with them.”

With the Indigenous Food Lab’s help, Native communities can develop the infrastructure to support a traditional food culture while also promoting healthier options than in the past.

“I witnessed it firsthand growing up,” says Mr. Sherman, who grew up on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in South Dakota and was raised on a U.S.-funded food program. While the U.S. funds the Food Distribution Program on Indian Reservations, which provides a mix of canned and frozen foods, fresh fruits and vegetables are largely absent, he says. “I didn’t realize it until later in life, until I started piecing things together on why we have a lot of obesity, heart disease, and Type 2 diabetes [in our communities].”

That has translated into swapping out some foods traditionally found in restaurants offering “Native” foods. Instead of Navajo frybread or deep-fried tacos with sour cream and cheese, there are corn tortillas and freshly cooked vegetables. Wild rice is blended seamlessly into grain bowls but isn’t a standout item. In-house herbal specialist Francesca Garcia has developed a handful of herbal teas, chaga lattes, and cocoa drinks – all caffeine-free and made with non-cane sugar sweeteners such as maple syrup.

The goal, says Mr. Sherman, is that this knowledge-sharing will inspire chefs and translate into more Native-owned and -operated food businesses on the market. Already, Ms. Garcia has plans to open her own tea business.

“Having friends and family capital gives people a lot of room to fail, but Native families generally don’t have that type of capital,” says Kit Fordham, executive director of Mni Sota Fund in Minneapolis, a Native community development financial institution in Minneapolis that provides wealth-building services to the urban Indigenous community, especially first-time business owners.

“And while they do exist, there are not a ton of success stories [of Native-run businesses] to look at,” says Mr. Fordham. “The more people see a cousin or friend starting a business, the more they build confidence and see what’s possible.”

Mni Sota Fund is launching a $10 million campaign to acquire and renovate a building on the American Indian Cultural Corridor on nearby Franklin Avenue, which will serve as an Indigenous wealth-building center and include business and credit labs. Mr. Fordham says the company has doubled in size every year for the past five years, in terms of assets and revenue – proof of a growing desire within Twin Cities Native communities to launch new business ventures.

That’s good news for Mr. Sherman and his team at the Indigenous Food Lab. Even if not everyone is looking toward branching out on their own, the lab offers plenty of learning and opportunities for growth.

Mr. DeFoe, who has been working alongside Mr. Sherman since the lab’s beginnings, says that the work he does with the Indigenous Food Lab is what he’s always wanted to do. Once a month, he joins team members to visit elders at the Little Earth community in Minneapolis – which has one of the highest densities of Native Americans in the U.S. – to serve breakfast, talk, and give back.

“I recently made wild rice porridge with blueberries and chokecherries for the community. Some people said, ‘I haven’t had this in such a long time,’” says Mr. DeFoe, who is Anishinaabe and grew up in Red Cliff, Wisconsin. “I was raised with fish and wild rice, but I have learned a lot about Native food since we started. I’m still learning.”

Video

Miyawaki: A little forest with a towering task

A Japanese method of planting fast-growing native forests is spreading worldwide. In the U.S., it has brought “grounded hope” to one of its practitioners, and nurtured a sense of community with each planting.

The tiny forest packs 900 saplings into 1,400 square feet. It’s expected to shoot up like its sister forest planted nearby a year earlier, and become self-sufficient a few years after planting. Its 50 native plant species not only sequester carbon and cool the air, but also support insects, a crucial part of the local ecosystem, says Amy Mertl, an entomologist at Lesley University in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

The forest, planted by the Cambridge city government, environmentalists, and residents, is a Miyawaki forest. First introduced in Japan, the dense, multilayered plantation of native plants aims to fully re-create growth that existed before deforestation.

“The overarching goal is to help nature regenerate more quickly than it would without our help,” says professional forest-planter Ethan Bryson, a consultant for Cambridge’s Miyawaki forest project. Hundreds of Miyawaki forests have been planted worldwide in recent years, according to Hannah Lewis, author of a book about them.

The two Miyawaki forests in Cambridge are the first in the northeastern United States, says Maya Dutta, who managed both planting projects. A software developer-turned-environmental activist, Ms. Dutta is the assistant director of regenerative projects at Biodiversity for a Livable Climate, a group that teaches people about ecological restoration. She used to fear – and avoid – environmental issues, she says, but her current work has given her “grounded hope.”

“As you do restoration on a landscape, you can start to see [beneficial] effects take place in a matter of years,” she says. “There are actual pathways to a future in which I can live and have a good life.” – Jingnan Peng, Multimedia reporter

Note: Jingnan Peng joined the Monitor’s “Why We Wrote This” podcast to talk about the creation of this video, and about his other work.

Q&A

A pianist reinvents herself in major and minor ways

Every musician brings their own experience to a composer, says Simone Dinnerstein. A yearlong sabbatical helped her reinvent her musical voice.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

How do you get to Carnegie Hall? Practice, practice, practice. In the case of classical pianist Simone Dinnerstein, you also spend thousands of dollars to rent a recital space at the famous landmark and invite classical music critics to your performance. That’s how Ms. Dinnerstein got herself on the musical map with her 2005 recording of Johann Sebastian Bach’s “Goldberg Variations.” It paid off. The classical music world embraced the previously undiscovered talent. Her 2007 album topped Billboard’s classical music album charts, as have 12 subsequent releases.

Ever searching for new creative projects, Ms. Dinnerstein has collaborated with visual artists, orchestras, and world-renowned musicians such as Renée Fleming and Philip Glass. The pianist also has her own ensemble, Baroklyn, which she directs from the keyboard.

Ms. Dinnerstein is returning to the stage following a yearlong sabbatical. On Sept. 23, she will perform in a concert presented by Emmanuel Music at Tufts University in Boston. The program will feature Bach’s Keyboard Concerto in D minor, Mozart’s Piano Concerto in C major, and Mr. Glass’ “Tirol” Concerto for Piano and Orchestra. The performance will include visuals created by artist Laurie Olinder.

Ms. Dinnerstein recently spoke with the Monitor about her creative process.

A pianist reinvents herself in major and minor ways

How do you get to Carnegie Hall? Practice, practice, practice. In the case of classical pianist Simone Dinnerstein, you also spend thousands of dollars to rent a recital space at the famous landmark and invite classical music critics to your performance. That’s how Ms. Dinnerstein got herself on the musical map with her 2005 recording of Johann Sebastian Bach’s “Goldberg Variations.” It paid off. The classical music world embraced the previously undiscovered talent. Her 2007 album topped Billboard’s classical music album charts, as have 12 subsequent releases.

Ever searching for new creative projects, Ms. Dinnerstein has collaborated with visual artists, orchestras, and world-renowned musicians such as Renée Fleming and Philip Glass. The pianist also has her own ensemble, Baroklyn, which she directs from the keyboard.

Ms. Dinnerstein is returning to the stage following a yearlong sabbatical. On Sept. 23, she will perform in a concert presented by Emmanuel Music at Tufts University in Boston. The program will feature Bach’s Keyboard Concerto in D minor, Mozart’s Piano Concerto in C major, and Mr. Glass’ “Tirol” Concerto for Piano and Orchestra. The performance will include visuals created by artist Laurie Olinder.

Ms. Dinnerstein recently spoke with the Monitor about her creative process. This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Classical conservatories and orchestras are in a moment of redefining themselves to draw in new audiences. How has this impacted your own creative expression?

With classical music, there’s this sense of an elitist feeling about it or a reputation that you have to be schooled in listening to it in order to enjoy it. What I’ve tried to do when I play in places where people may not normally be listening to classical music is I will talk to the audience before I play something about a couple of things that strike me about the music. ... Oftentimes, people find that really helpful because it gives them something to latch onto.

The recording that really made a huge impression on me was a recording of Jacques Loussier, the jazz pianist, with his trio playing the [Bach] “Goldberg Variations.” ... [His] freedom of improvisation made me think that I needed to completely rethink how I was looking at the music. I had to be much more adventurous and think about how there are lots of different aspects to the music having to do with rhythm and with breathing, and how one would sing it. I stopped thinking about, “Oh, I shouldn’t be playing ornaments this way because that’s [not] what the scholars say.” ... I have different associations with those kinds of rhythms than people would have had during [Bach’s] time. ... The music lives right now.

How does collaborating with others enrich the understanding you bring to your own solo work?

The give and take between artists is not always done verbally. Sometimes there’s something that happens that’s just intuitive while you’re playing, and then you realize that you just created something new together that neither one of you would have done separately.

Can you give me an example?

I worked with visual artist Laurie Olinder on a fabulous project together called “The Eye Is the First Circle.” I used my [artist] father’s [Simon Dinnerstein] “Fulbright Triptych” and Charles Ives, his “Concord” Sonata, to create a kind of narrative theater piece about my own origins as an artist. [Ms. Olinder] is a very visually oriented person. ... What I’ve found working with her is that I actually have a very strong visual sense, too, and I never realized how strong until I did that project.

I understand you’re coming off a sabbatical year. What was the creative process like for you during that period?

At the very start of [my] sabbatical, I unexpectedly needed to have hand surgery, and so I wound up having three months when I couldn’t play at all. My husband and I became members of the Metropolitan Museum, and we started going there once a week and really looking at art that we had never looked at before. And I started doing all sorts of interesting body work, like yoga and Pilates and breath work. I really explored other parts of myself that I hadn’t done for a long time or ever. Once I started practicing again, I suddenly had very little time to learn all the repertoire that I had to learn for next season. It was almost like I went into a new phase of being a student again, except I was also the teacher of myself. I discovered all sorts of habits that I had that were so ridiculous, like a waste of time. I was like, why am I using those fingers [for that passage]? It doesn’t make any sense. I just had never really taken the space to consider how I was doing everything.

How do you use creativity to deal with fear in performing or fear of making a mistake?

Sometimes something’s happening in my life that is challenging – either personally, or there’s something in the news that’s been really upsetting, or a friend is having a hard time, or something that upsets me. What I have found is that I can often process that through music. Sometimes when I’m performing, these feelings I have apart from the piano, I take them to the performance. As long as I don’t let them completely take over, I can really bring something different to a performance. Sometimes adversity outside of the concert hall can make the concert more intense. I’m always playing at different pianos, and sometimes I’ll find an instrument [at a performance], and I am not feeling like we are friends. Sometimes those concerts are my best concerts. I have to figure out how to make that piano sing the way I want it to.

J.S. Bach is known for his sacred works, and yet today so few people seem drawn to church. What are the timeless elements of Bach that could be useful for this time?

All of Bach’s music was sacred. Everything that he did was connected to his faith because that was the center of how he would have thought about the world. I am not a religious person, but I definitely feel that. ... I think there’s more to [life] than just living each day one at a time and then we die. I think that there’s some kind of unifying force or feeling or there is some beauty or awe of the world around us – the awe of nature and space and time and history and all these things that we can wonder at. I think that Bach’s music accesses that.

What are you hoping audiences will take away from your upcoming concert?

I think that this concert is going to be very interesting because there are a few different new elements to it. It’s unusual to have a concert that’s only piano concertos. So having those three composers – Bach, Glass, and Mozart – three incredibly profound composers, there is no fluff in this program. Also, having Laurie Olinder’s video will be fascinating. I have not collaborated with her on this. She’s been given this project that she’s doing entirely on her own, so it’s going to be a complete surprise.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Big thanks for a Mideast mediator

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

Perhaps no other nation has been thanked so much this year as Oman. The Muslim country at the tip of the Arabian Peninsula has been a behind-the-scenes interlocutor for a prisoner swap between Iran and the United States as well as the release of three Europeans from a Tehran prison. It has facilitated talks that may end the war in Yemen. It helped Egypt and Saudi Arabia renew ties with Iran. And it was essential for Syria’s return to the Arab League.

For a country not seeking credit for its back-channel peacemaking, Oman received big praise from two big players in recent months. U.S. President Joe Biden and Iranian Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei each thanked Oman for its quiet mediation.

All this gratitude reflects well on the reasons that Oman is a trusted go-between, a sort of Switzerland of the Middle East that leads by listening.

“Our neutrality is not passive. It’s constructive, it’s positive, it’s proactive,” says Foreign Minister Sayyid Badr Albusaidi.

Oman’s perspective relies on the principle of mutual respect between peoples. When rivals in the region need it, Oman provides a neutral place for discreet listening and calm trust-building. Thanks are optional.

Big thanks for a Mideast mediator

Perhaps no other nation has been thanked so much this year as Oman. The Muslim country at the tip of the Arabian Peninsula has been a behind-the-scenes interlocutor for a prisoner swap between Iran and the United States as well as the release of three Europeans from a Tehran prison. It has facilitated talks that may end the war in Yemen. It helped Egypt and Saudi Arabia renew ties with Iran. And it was essential for Syria’s return to the Arab League.

For a country not seeking credit for its back-channel peacemaking, Oman received big praise from two big players in recent months. U.S. President Joe Biden and Iranian Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei each thanked Oman for its quiet mediation.

All this gratitude reflects well on the reasons that Oman is a trusted go-between, a sort of Switzerland of the Middle East that leads by listening.

“Our neutrality is not passive. It’s constructive, it’s positive, it’s proactive,” Foreign Minister Sayyid Badr Albusaidi told the news website Al-Monitor. “We really stick to the principle of, how do we create a sustainable environment of peace and security and stability so that our people and our generations can prosper.”

Another one of Oman’s principles is to presume all players in a negotiation operate from integrity and good intentions. Oman has generally avoided boycotts and other ways of excluding countries. Its “toolkit for peace,” as the foreign minister explains, comes from Oman’s centuries of experience in sharing water between its people.

Oman certainly has national interests, such as making sure the conflict in neighboring Yemen does not spill across the border. And like most nations in the Mideast, it needs peace to draw investors and create jobs for its restless youth. Yet its longer perspective relies on the principle of mutual respect between peoples. When rivals in the region need it, Oman provides a neutral place for discreet listening and calm trust-building. Thanks are optional.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

How can we feel safe?

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 4 Min. )

-

By Susan Tish

When confronted with the clamor of fear, we can turn to God, whose protecting power is always at hand.

How can we feel safe?

“When I have kids one day,” my 20-something son said to me, “how will I ever feel safe dropping them off at school when it seems as if every school is vulnerable to gun violence?”

What he and many others are yearning for, I realized, is relief from anxious concern that the world is an unsafe place and that there appears to be nothing we can do about it. This climate of fear is so prevalent that even a young man sitting on the porch in a quiet neighborhood in the United States was struggling with it.

While laws and other measures are typical in a civilized society seeking to protect its citizens, it’s worth asking whether these measures alone will ever be enough to reassure us completely and silence our fears. Mary Baker Eddy, who discovered a timeless law of divine care that has proved effective in freeing people from fear and protecting them from danger, posed a similar question in her book “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures”: “Are material means the only refuge from fatal chances? Is there no divine permission to conquer discord of every kind with harmony, with Truth and Love?” (p. 394).

Feeling safe and being protected from danger are dependent on something that is always right at hand: consciousness of the fact that we are the children of God and that our ever-present divine Parent is continually safeguarding each of us. God, as Spirit, is everywhere and all around us, and we are never outside of Spirit. We dwell in the permanent protecting embrace of the divine Father-Mother, whose infinite wisdom guides us intelligently and whose perfect love blankets each one in safety.

Safety is included in what we are as God’s spiritual offspring. It is a permanent element of our being rather than an externally determined condition. As we gain this spiritual understanding, not only do we feel protected and calm ourselves but our spiritual sense of God’s safeguarding of His children embraces others as well.

The practical impact of this is illustrated in the Bible’s epic story of Moses. As Moses was leading the Israelites out of Egypt, there seemed to be no end to the threats to their lives. Their fears certainly appeared justified – imagine being chased by the entire Egyptian army or facing the possibility of running out of food and water.

Yet Moses was so clear that God is the great I AM – the true Life and Mind of His children and the all-powerful Love guiding them, as Christian Science explains – that they experienced God’s protecting presence in many ways. The Israelites’ eyes were opened to supply for their needs and guidance and safe passage to their destination. God’s sustaining, safeguarding presence was shown to be a constant.

What was needed was a shift in thought – seeing beyond fear to God’s care and trusting it. The same is needed today. When confronted with the clamor of fear, we can turn to the spiritual fact that God’s protecting power is at hand.

Several years ago, our family arrived at the airport on the same day that a terrorist plot had been uncovered and thwarted. Because we were flying on a plane operated by the same airline at the same airport where the incident took place, news media personnel surrounded our family. They appeared to be looking for a sound bite about airline travel no longer being safe.

But prayer had assured me that we could feel peaceful about and comfortable with our travel plans. I calmly explained that we loved to travel and shared some of the ideas I’d been praying with. Family members made it clear that they were grateful for the peaceful, joyous outlook that enabled us all to feel safe proceeding with the flight.

While there are many things in the world today that could make us suspicious or fearful, an insistent focus on these potential dangers can lead us into a state of panic and despair where it is much harder to live our lives with the dominion and joy that are inherently ours. We, as individuals, have an opportunity to help neutralize this mental climate of fear through our own insistence on what is spiritually true. The real constant, throughout all time, is the presence and power of God, divine Life and Love, lighting our path and making our steps secure.

We’re not created by God to be fragile or vulnerable, but safe, joyful, and purposeful. With the certainty that our loving Parent is forever caring for us, we can disengage from the fears that would pull us into panic and take a firm stand on the bedrock of the proven truth that we are inherently safe, and so is everyone else.

Adapted from an article published in the Aug. 21, 2023, issue of the Christian Science Sentinel.

Viewfinder

The drive to win

A look ahead

Thanks for joining us today. On Monday, our package of stories will include a buzzy report about the challenges of beekeeping in Tunisia. Also, you can hear the Monitor’s Jingnan Peng talk about the creation of today’s Miyawaki forest video – and about his approach to videography – on this week’s “Why We Wrote This” podcast.