- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usMonitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Reporting in the West Bank

Hearing from Middle East correspondent Taylor Luck about his recent reporting from the West Bank was bracing. Violence is spiking. Checkpoints appear overnight. Routes change abruptly: A turn down a side road spurred a farmer to yell that it was a settler-run, shoot-to-kill zone. “We turned around just in time,” says Taylor.

But Taylor noted another powerful current in Ahmed Abu Hussein, a Bedouin shepherd whose community sees daily settler attacks. Why was he so calm, Taylor asked. “He told me, ‘I am just one in a chain of generations, passing on our herd and way of life. There were troubles that threatened my ancestors too. The land will remain, and we will remain.’”

All of what Taylor shared is too good to miss. Read the full details here.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

How migrant crisis reshapes New York – and Mayor Adams

Change is a theme that runs through today’s Daily. For migrants, it can be making their way in a strange world. For older people, it’s how to live well in a new stage of life. We start by looking at how an unexpected demand on New York City Mayor Eric Adams has transformed him into a national voice on immigration.

-

By Hillary Chura Contributor

“We need help” has been New York City Mayor Eric Adams’ mantra for months, as the number of migrants coming to the Big Apple climbs. He’s called on the Biden administration to provide more aid to the city and work authorization for asylum-seekers.

On Thursday, Mr. Adams’ administration announced plans for 5% budget cuts to all city agencies in response to the cost of supporting new migrants. Further cuts are anticipated.

None of this was part of Mr. Adams’ plan.

When the former police officer and centrist Democrat ran for mayor in 2021, the largest metropolis in the United States was experiencing problems with crime, homelessness, and lack of affordable housing. But Mr. Adams was soon faced with an urgent situation: migrants arriving in New York needing beds, which the city guarantees. City officials say 142,000 migrants have arrived since April 2022 and about half of them remain in the city’s care.

The situation has unexpectedly turned Mr. Adams into a leading national voice for Democrats on immigration. He could also influence how New Yorkers and other Americans view President Joe Biden’s handling of the record-setting numbers of people crossing the U.S.-Mexico border.

“Everything about New York gets magnified,” says Joseph Viteritti, public policy professor at New York City’s Hunter College.

How migrant crisis reshapes New York – and Mayor Adams

New York City Mayor Eric Adams strides alongside a chain-link fence in front of a shelter tent for migrant families, erected at a former naval air base in Brooklyn. In a video posted by his office, he notes that each tent holds 500 people.

“This is not, you know, the best conditions,” concludes Mayor Adams at the end of the video, posted on X, formerly Twitter, on Nov. 12. “But we’re managing a crisis, and we cannot say it any better that we need help.”

“We need help” has been Mr. Adams’ mantra for months, as the number of migrants coming to New York City climbs. He’s persistently called on the Biden administration to provide more aid to the city and accelerate work authorization for asylum-seekers. On Thursday, New York City officials announced plans for 5% budget cuts to all city agencies, including the police and fire departments, in response to the cost of supporting new migrants. Further cuts are anticipated.

None of this was part of Mr. Adams’ plan.

When the former police officer and centrist Democrat ran for New York City mayor in 2021, he was auditioning for arguably second-toughest elected job in the United States. The nation’s largest metropolis was experiencing problems with crime, homelessness, and lack of affordable housing and child care.

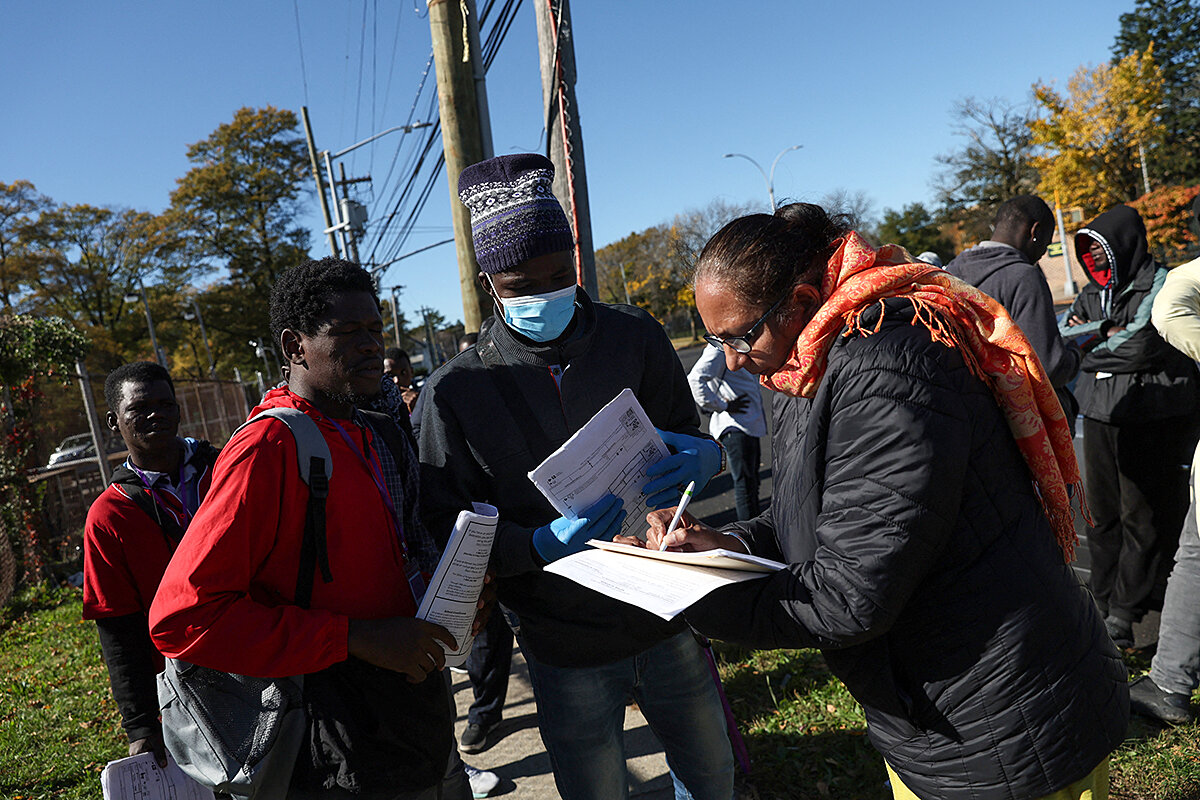

But before making a big dent on campaign promises, Mr. Adams was faced with an urgent, multibillion-dollar jam: tens of thousands of migrants from around the world, transiting from the southern border of the U.S. and arriving in New York needing beds, which the city guarantees to those who ask. City officials say 142,000 migrants have arrived since April 2022, and about half of them remain in the city’s care.

For Mr. Adams, the situation means he’s unexpectedly become a leading national voice for Democrats on immigration. He could also influence how New Yorkers and other Americans view President Joe Biden’s handling of the record-setting numbers of people crossing the U.S.-Mexico border.

“If people come to the conclusion that [the migrant issue] will have a major impact on the city, which it can, that’s a big story. New York has a way of becoming the example for a lot of things, whether they be positive or negative. Everything about New York gets magnified,” says Joseph Viteritti, public policy professor at New York City’s Hunter College. “It’s not the same thing as if something happens in Corpus Christi or San Antonio.”

Mr. Adams appears to think similarly.

“The way goes New York, goes America. If we don’t get it right in New York City, we’re not going to get it right in America,” he said at a rally in August calling for expedited work authorization for asylum-seekers.

“Bring us your tired” ... for how long?

Supporting migrants will cost New York City $11 billion over the next two fiscal years, officials say, largely because of a unique right-to-shelter pact between the city and the state. The city agreed more than 40 years ago to provide housing for anyone who asks, to address homelessness.

Discussions over the shelter agreement ramped up in 2022 when Texas started publicly busing migrants to New York. Thousands more found their own way to the Big Apple. The factors motivating global movement – economic problems, conflict, and climate change – are unlikely to abate anytime soon, according to the Migration Policy Institute.

People from Latin America have long crossed the U.S.-Mexico border, quietly dispersing across the country to work. But this round of migration is unique with more families, asylum-seekers, and nationalities represented, analysts say.

Perhaps to show that the city had a bigger heart than the Lone Star State, Mr. Adams at first personally greeted new arrivals.

“This is a place where the Statue of Liberty sits in the harbor and says, ‘Bring us your tired, those who are yearning to be free.’ That’s what these asylum-seekers are doing,” the mayor said in August 2022.

Mr. Adams grew up poor in Queens, as the son of a house cleaner and a butcher. Some who know him attribute his inclusive attitude to his upbringing, including attending a small, close-knit storefront church.

“Coming out of that background, you don’t forget those who are the neediest,” says the retired Rev. Herbert Daughtry of Brooklyn, a well-known civil rights leader and one of Mr. Adams’ early mentors.

In recent months, the mayor’s speeches about migrants have evolved, after first welcoming them with “open arms.” This summer he said, “Our hearts are big, but our resources are not endless.” In a fall town hall meeting, he said the migrant issue was a problem that he “didn’t see an end to” and called it an “issue that will destroy New York.”

Mr. Adams still believes in supporting migrants, many of whom are asylum-seekers. But he thinks the federal government should play a bigger role with faster work authorization and more aid, say his associates.

The mayor “believes we have to accept and take care of these people – it’s not just New York. ... It’s a national problem that the federal government and many of the states, to their shame, have not taken part in [or] done anything about,” says Sid Davidoff, a longtime lobbyist and former aide to midcentury Mayor John V. Lindsay. He says he’s been friends with Mr. Adams for a decade.

The mayor’s office did not respond to queries.

Earlier this month, Mr. Adams also learned the FBI is investigating his campaign finances. He has not been charged and denies any wrongdoing.

Looking for solutions

Though the mayor said more than a year ago that the city was “nearing its breaking point,” it continued to set up more than 200 shelters and lodge people in hotels.

Mr. Adams has declared a state of emergency, pleaded for money from Washington and Albany, and tried to send migrants to other New York communities. He traveled to Mexico, Ecuador, and Colombia last month, telling asylum-seekers that New York loved them but was full – and that they should go elsewhere. But to no avail.

With no letup in arrivals, the city started ratcheting back services. Agencies expanded a program offering migrants one-way tickets out of town, began to limit time in shelters, and stopped guaranteeing beds. The city, for the first time, also launched a legal challenge to suspend the shelter agreement itself.

Voiding the measure won’t reduce city homelessness or the migrant influx and will just move shelter residents onto the street, says Edward Josephson, supervising attorney at the Legal Aid Society, which is fighting the city’s challenge.

With two years before reelection, the city’s 110th mayor is talking up how he’s brought workers back to the office, reduced gun violence, and is working toward more affordable housing. While the mayor polls better than President Biden, his favorability numbers among New York City voters have slipped along with public support for migrants, according to Siena College polls.

Even though his actions during the migrant crisis have proved unpopular, he has been well placed for reelection as an incumbent, says Alyssa Katz, executive editor of The City, an online news site. She says the FBI investigation may hinder a second term should evidence emerge of wrongdoing. She notes New York City mayors are no stranger to corruption probes. Every mayoral administration for the past 45 years has been investigated, though no mayor has been charged, according to The City.

Undermining President Biden?

Mayor Adams’ harshest critics maintain he’s bolstering the GOP. They say that his comments about high crime and his statement that the migrant crisis will “destroy” New York City are fueling right-wing rhetoric and putting President Biden’s reelection at risk.

“He said he’s the future of the Democratic Party,” says Susan Kang, associate professor of political science at John Jay College of Criminal Justice. “But he openly criticizes Biden for failing to [help New York City]. It shows he doesn’t care about Biden’s election chances.”

Insiders were astonished when the mayor criticized President Biden in April, says George Arzt, a press secretary to former Mayor Ed Koch who has been friendly with Mr. Adams for years. He joked that Mr. Adams would have the “speaking slot at 3 a.m.” at the 2024 Democratic National Convention in Chicago.

As the leading Democratic voice in seeking federal help, Mr. Adams was criticized for missing meetings with other big city mayors and federal officials in Washington earlier this month after he learned about the FBI raid on a top aide’s residence and flew home.

The mayor of New York has a reach beyond the city’s 469 square miles. As the urban epicenter of the country’s migrant crisis, New York could provide a how-to guide for cities facing new migrant surges, says C. Mario Russell, executive director at the Center for Migration Studies of New York.

“Given its unique experience and understanding with migrants and asylum seekers over the last year and a half, New York City is in a particularly strong position to help lead that conversation, bringing lessons learned about how to receive migrants and ideas for [what] a coordinated response with other cities might look like,” Mr. Russell said via text.

In charts: The shifting tides of US immigration

An influx of migrants is testing the capacity of U.S. cities to respond. Yet a broader look at immigration trends tells a story more nuanced than “crisis” headlines.

Immigration has been central to the American experiment from the start. After a decline during the middle and end of the 20th century, the immigrant population in the United States is nearing the peaks of the early 1900s.

This growth is still modest – immigrants made up just under 14% of the total population last year. It’s slower than in other wealthy nations.

Gridlock in Congress has kept America’s immigration system effectively frozen in the 1990s, and this legislative impasse affects not just safety and security, experts say, but also the economic prosperity of the country as well.

“Immigrant workers are increasingly supporting our labor force growth as our population ages and birth rates lower,” says Julia Gelatt, associate director of the U.S. Immigration Policy Program at the nonpartisan Migration Policy Institute. “Our immigration pathways aren’t keeping up with the ways we want to use them today,” she adds.

While a majority of Americans think immigration is good for the country, a growing number want it curtailed, according to Gallup. Furthering negative views of immigration are the beliefs that immigrants commit more crimes than native-born residents and take jobs from them, experts say. Both are unfounded, according to decades of statistics and research.

– Henry Gass / Staff writer

Migration Policy Institute, U.S. Census Bureau, Cato Institute, United Nations, Migation Policy Institute, Pew Research Center

Why some Ukrainian refugees are risking a return now

War is a key reason people flee their homelands. What happens when you try to go home? An increasing number of Ukrainians have returned, finding both balm and new demands for resilience in a changed environment.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Though Iryna Lvovych fled Ukraine with her two children to Poland at the start of Russia’s full-scale invasion, she always anticipated returning home in time for her son’s birthday.

In May of last year, she stuck to her plan. But in some ways, that was the easy part.

Ms. Lvovych is among the more than 1 million Ukrainians who have made the intensely personal choice to return and adapt to life in a nation that is constantly under threat of Russian attacks.

Those who have returned point to the pull of home and reunification with family and friends, and the draw of jobs and a more affordable lifestyle, as well as the ability to live their lives on their own terms again, not as refugees in foreign countries. But the war and long periods of separation have also altered relationships between husbands and wives – men between 18 and 60 years old are barred from leaving Ukraine – and everyone is learning to live with loss amid the uncertainty of an ongoing war.

“I wanted to come home,” Ms. Lvovych says. “Coming back wasn’t hard. The question was how to live with this. Do you accept that a rocket can fly by? You either accept this or you don’t.”

Why some Ukrainian refugees are risking a return now

Though Iryna Lvovych fled Ukraine with her two children to Poland at the start of Russia’s full-scale invasion, she always anticipated returning home in time for her son’s birthday.

In May of last year, she stuck to her plan. But in some ways, that was the easy part.

“I wanted to come home,” she says. “Coming back wasn’t hard. The question was how to live with this. Do you accept that a rocket can fly by? You either accept this or you don’t.”

Ms. Lvovych, whom the Monitor interviewed in Poland last year, is among the more than 1 million Ukrainians who have made the intensely personal choice to return and adapt to life in a nation that is constantly under threat of Russian attacks.

Over 6 million Ukrainians fled after the start of the war on Feb. 24, 2022, and more than 3.7 million people remain displaced within Ukraine. But the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees estimates, based on International Organization for Migration data, that over 860,000 refugees have returned to their homes in Ukraine and stayed for at least three months. And another 353,000 people have returned from abroad to areas of Ukraine that are different from their former homes, according to a survey conducted between May and June.

Accurate estimates are “challenging” due to the ongoing armed conflict that has resulted in multiple displacements, a spokesperson for the U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees told the Monitor.

Those who have returned point to the pull of home and reunification with family and friends, and the draw of jobs and a more affordable lifestyle, as well as the ability to live their lives on their own terms again, not as refugees in foreign countries. But the war and long periods of separation have also altered relationships between husbands and wives – men between 18 and 60 years old are barred from leaving Ukraine – and everyone is learning to live with loss amid the uncertainty of an ongoing war.

A new chapter

Ms. Lvovych, whose apartment in Irpin (just outside Kyiv) was destroyed during Russia’s invasion, moved to her childhood hometown of Lutsk in western Ukraine, an area she felt was safer than the Kyiv region. Before returning, she worried about her son’s school, but says he has adapted and learned to go down to a shelter during air raids.

As an architect and interior designer, Ms. Lvovych is working to renovate her apartment and will decide at the end of this school year whether to move back to the city she truly considers home. She’s busy at work, as Ukrainians rebuild homes. “Shelters have become a must-have” addition, she says.

Her personal life has also seen changes. Ms. Lvovych and her husband divorced. She says amid the heightened emotions of the war, many people are taking stock of what they want in life, prompting both marriages and divorces. She sees her life as starting a new chapter.

Ms. Lvovych thinks the war could still go on for a long time. “Our losses are great. This is not a choice to fight or not to fight. ... If we stop fighting, it is the death of the Ukrainian nation,” she says.

She’s focused on “working, donating, and raising my kids as even bigger patriots and as Russophobes.” Ms. Lvovych has been seeing a psychologist regularly, something she says is “necessary” because “all of this just won’t pass on its own.”

Svitlana Shevchenko, whom the Monitor also interviewed in Poland, returned home to Zaporizhzhia with her teenage daughter, Yliia, in July, despite Russians still occupying territory in the region and Europe’s largest nuclear power plant being in harm’s way. In an email, Ms. Shevchenko says that the best part of being home is “the ability to breathe without chest pain. And in a more pragmatic sense, the ability to plan your life again.” Being at home has given her the “energy to act.”

But even as Yliia’s dream of dancing at the regional philharmonic in Zaporizhzhia came true, Ms. Shevchenko says she still worries that a Russian missile strike might “hit the philharmonic building and kill this dream and my child too.”

Reinventing relationships

Tetyana Filevska fled her home south of Kyiv the day the war began with her 3- and 6-year-old daughters, Anhelina and Khrystyna. They stayed at her grandmother’s home in western Ukraine until March and then went on to spend four months living in Slovakia before moving to London.

Ms. Filevska, who works as the creative director of the Ukrainian Institute in Kyiv, which promotes Ukrainian culture, felt by summer that the Ukrainian armed forces were getting stronger. After a year in London, they returned home in July.

“I just couldn’t be away from my husband, from my home, from my life,” she says. “I was in a very burned-out, emotional, depressed state. ... The minute I crossed the border, I started feeling better and better, and I feel like I am getting cured just by the fact that I am at home.”

Ms. Filevska and her husband, Andrii, wanted additional support and went to see a family psychologist for sessions. “It’s like a different marriage, actually. We have to reinvent our relationship. ... We had two different experiences going through this trauma and being [long] distance,” she says.

Her family agreed to follow new rules, including not attending mass events that could be targets for a Russian strike. They’ve also postponed any travel that is longer than one night away.

“The condition that we’ve all accepted returning back home, if it’s the end, it’s the end for all. We don’t want to stay apart,” she says.

“Uncomfortable social situations”

Anzhela Yeremenko has written a popular blog under the name Bad Mama for nine years, talking about her life in Kyiv and being a single mother to 9-year-old daughter Eva. Ms. Yeremenko was traveling abroad in February 2022, and then spent a year living in Berlin with her boyfriend and daughter.

“The problem was that I never planned to live abroad,” she says. “And everything that I have [is] in Ukraine – my connections, everything that I love, my books publishing ... my blog for Ukrainians.”

Following a breakup, Ms. Yeremenko left Germany, spent over a month living in Portugal, and then moved to Valencia, Spain – a place she loved. But “I had two jobs, no people, no friends. I was so isolated there.”

She decided to return to Kyiv this summer to see how she’d feel. “I just felt that I need to be here. ... I will regret in 10 years that I just sat in Spain and was afraid,” she says. She officially returned at the start of August. “Home is just people. It’s your connections; it’s the streets. ... When I came back, I found my home.”

Ms. Yeremenko is in her second year of a master’s program to become a psychologist and wants to have a talk show discussing topics including addiction, talking with people who have lost limbs, and discussing the rebuilding of Ukraine. “We will have uncomfortable social situations, and someone should talk about that.”

Hopes for the future

All the women have one dream: victory.

“I just want us to win and for Russia to collapse and to be defeated completely, so that it doesn’t threaten anyone else,” Ms. Filevska says. With winter coming, she’s stocked up on firewood and flashlights.

Surveys conducted by the U.N.’s refugee agency have shown that a large majority of Ukrainians want to return home, with 76% of Ukrainians surveyed in the European Union and Moldova reporting that they plan or hope to return permanently.

As the war passes the 20-month mark, estimates on the number of Ukrainians who will remain abroad range widely from over 1 million to over 3 million, showing that the long-term demographic question remains unclear.

“We continue to believe in goodness, despite the horrors we constantly witness,” Ms. Shevchenko says, “and that is why we desperately need the support of the world to keep this hope alive.”

Editor's note: This story has been updated to clarify the source of the U.N.'s estimate of returning Ukrainian refugees.

Aging gets a makeover at this gerontology summit

Many older people find that the later stage of life comes with new opportunities – and the burden of stereotypes and judgments. Researchers are aiming to bust through these in the interest of happier lives, free from discrimination.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

The 76 million Americans in the great baby boom demographic bulge will all be 60 to 79 years old next year. But their powerful influence is not retiring.

Outlines are emerging of how the now-older generation is expected to meet the experience of aging and reshape our culture. Its predecessors are already stretching expectations of elderhood.

So what does it mean to be “old”?

That question filled the cavernous Tampa Convention Center with researchers from all over the world last week, with hundreds of scholarly presentations at the annual meeting of the Gerontological Society of America.

The driving angle of the organization these days is reframing perceptions of aging – liberating it from misconceptions and bias. The goal ultimately is to support healthier, happier, longer lives.

The World Health Organization calls ageism the most widespread form of discrimination in the world, saying it is even more implicit and hence unchallenged than sexism or racism.

“We aren’t born ageist. We’re taught,” says Tracey Gendron, chair of the Virginia Commonwealth University’s department of gerontology. “We’re definitely making progress – awareness is on the increase.”

Aging gets a makeover at this gerontology summit

The 76 million Americans in the great baby boom demographic bulge will all be 60 to 79 years old next year. But their powerful influence on the economy, education, culture, politics, and lifestyles is not retiring.

Outlines are emerging of how the now-older generation is expected to meet the experience of aging and reshape our culture. Its immediate predecessors – members of the so-called Greatest Generation (born 1901-1924) and the Silent Generation (born 1925-1945) – are already registering record numbers of centenarians and stretching boomers’ expectations of elderhood.

So what does it mean to be “old”?

That question filled the cavernous Tampa Convention Center with researchers from all over the world last week, with room after room of more than 500 scholarly presentations at the annual meeting of the Gerontological Society of America.

The driving angle of the organization these days is reframing perceptions of aging – liberating it from misconceptions and from discrimination.

The formal scholarly presentations had new takes on care for the caregivers of elders, the effects of war in early life on aging, the double grip of ageism plus race or gender discrimination, aging education starting in grade school, how hearing aids may avert dementia, third-act careers, hoarding as decision-making avoidance, “driving cessation” (aka taking the car keys away from Dad), robot companions, elder tech literacy, and so on.

In other scholarly work, young researchers from all over the world – their studies sometimes too fresh or unformed to have scored spots in formal symposiums – stood in a maze of “poster” slots 400-deep across an exhibition hall. They explained their work on a poster to passing professionals in what amounted to earnest elevator pitches.

Cynthia McDowell stood in front of charts showing her slice of a larger research project on how social singing can reduce the stigma and isolation of people with dementia and their care partners. The University of Victoria Ph.D. student’s work focuses on the care partners. Self-evaluations over two four-month periods of choir participation revealed that “distress” dropped precipitously. She calls it a “quiet intervention” – a nonpharmacological alternative to treating distress. This may sound intuitively obvious, but a study like hers gives the theory evidence that can be built upon to generate other theories, and ultimately programs to help.

Such a meander through the foundations of age-related research – behavioral, sociological, medical, spiritual – is largely not for a consumer but is more of an expert’s candy shop visit. But some of the most important outcomes of this annual gathering come from “nuggets of evidence around different topics,” said Robyn Stone, an aging and long-term care expert in the Clinton administration who is now with the nonprofit LeadingAge. Those nuggets will end up affecting you, the public, in the form of policy, programs, or advice. The goal is to support healthier, happier, longer lives.

The buzz in the conference rooms, flowing partly from recent research, was often about basic reframing:

- Watching out for ageist language that can sow institutional discrimination and self-imposed ageism.

- Understanding that aging is not a disease, but an experience that starts at birth.

- Recognizing the evidence that people over age 65, now a fifth of the American population, are not a burden on society or a drain on scarce resources.

Lacing through almost every discussion on any topic was the constant mental check for ageism. The World Health Organization calls ageism the most widespread form of discrimination in the world, saying it is even more implicit and hence unchallenged than sexism or racism.

“We didn’t really start addressing ageism until five, 10 years ago,” says Tracey Gendron, chair of the Virginia Commonwealth University’s department of gerontology, who spoke to a session of the Gerontological Society’s journalism fellows. “We’re definitely making progress – awareness is on the increase.”

But, adds Dr. Gendron, the author of the recent book “Ageism Unmasked,” “we aren’t born ageist. We’re taught. ... It’s all of these messages that we’ve had – the characters in fairy tales, the very earliest books that we are reading to our children, are really rife with these stereotypes and caricatures.”

Indeed, there was professional preoccupation here with ageism building on the American political scene – with presidential front-runners Joe Biden, turning 81 next Monday, and Donald Trump, 77.

“If Joe Biden or Donald Trump fall, it’s big news. But I think the big news should be, well, what happened after the fall?” said Steven Austad, a biology professor at the University of Alabama in Birmingham and author of “Methuselah’s Zoo: What Nature Can Teach Us About Living Longer, Healthier Lives.” He was referring to President Biden’s fall while cycling last June: “The bike fell. He scraped himself, got up, and he was fine.”

One of Dr. Gendron’s observations about ageism may dog anyone who heard it well past the conference. “Ageism lives within compliments like, ‘You haven’t aged a bit. You look great for your age. ... That haircut makes you look younger.’ It is ageism. And if you answer, ‘Thank you,’” she says, that’s ageism too.

This article was written with the support of a journalism fellowship from the Gerontological Society of America, the Journalists Network on Generations, and the Silver Century Foundation.

How Cleopatra got caught up in a culture war

Here’s a question: When it comes to ancient kingdoms and cultures, who has legitimate claim to use that history to define themselves today? And who, if anyone, are history’s gatekeepers?

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

The Dutch National Museum of Antiquities was intent this summer on celebrating the inspiration that scores of Black artists have drawn from ancient Egypt.

It’s been too much for the Egyptian government, whose ministry promptly declared that the Dutch museum was “falsifying history.” And it banned its archaeologists from future excavations at a UNESCO World Heritage Site in Egypt they’ve accessed since the 1970s.

At the heart of the controversy is a debate over ancient Egypt: Who should interpret it, and how? “Who writes history, from what perspective, and according to which rules?” the Dutch museum asks attendees.

Modern-day discussions about race and ethnicity didn’t exist during ancient times. The long history of colonization and the appropriation of Egyptian artifacts provides a potentially explosive backdrop for today’s explorations of race and ethnicity. And the Egyptian government is now pushing back with its own interpretations of ancient Egypt.

“There’s been centuries, millennia really, of appropriations of ancient Egyptian imagery to all kinds of ends,” says Pansee Atta, an Egyptian Canadian artist. “Some of which have been supportive of Egyptian people and their political autonomy and some which have been deeply extractive. ... But ancient Egyptian artifacts have been so well preserved and so visible that it’s been a real source of inspiration for all people, continuously for thousands of years.”

How Cleopatra got caught up in a culture war

Hollywood has long chosen people like Elizabeth Taylor to play Cleopatra. But this year, Netflix cast the Black British woman Adele James in the title role of Queen Cleopatra for its series.

A social media firestorm ensued. Egyptians, who felt that their history was being misrepresented, claimed that she was light-skinned and of Macedonian origin. Some of them launched a Change.org petition demanding that the series be canceled.

Into that simmering cauldron stepped the Dutch National Museum of Antiquities, which was intent this summer on celebrating the inspiration that scores of Black artists – from Prince and Michael Jackson to Beyoncé and Erykah Badu – have drawn from ancient Egypt.

That was too much for the Egyptian government, which declared that the Dutch museum was “falsifying history” and banned its archaeologists from future excavations at a UNESCO World Heritage Site in Egypt, where they have been working since the 1970s.

“The government’s reaction isn’t surprising for a number of reasons,” says Ali Hamdan, a political science professor at the University of Amsterdam. “Anti-Blackness does have a long history in Egypt. But the more important reasons are the history of imperialism and its connections to archaeology in Egypt.”

At the heart of the controversy is a debate over ancient Egypt: Who should interpret it, and how? “Who writes history, from what perspective, and according to which rules?” the museum exhibition asks visitors to ponder in one of its many text displays.

The long history of colonization and the appropriation of Egyptian artifacts provides a potentially explosive backdrop for today’s explorations of race and ethnicity. And the Egyptian government is now pushing back with its own interpretations of ancient Egypt.

“There have been centuries, millennia really, of appropriations of ancient Egyptian imagery to all kinds of ends,” says Pansee Atta, an Egyptian Canadian artist and scholar. Some have supported Egyptian political autonomy, she says, while others have removed monuments to the West.

“But ancient Egyptian artifacts have been so well preserved and so visible that they have been a real source of inspiration for all people, continuously for thousands of years,” she points out.

Culture, politics, and Egypt

In Leiden, dozens of museumgoers paused before exhibits at “Kemet: Egypt in Hip-hop, Jazz, Soul & Funk,” as the music of Prince, Erykah Badu, and Nina Simone played, accompanying various images including a statue of the American rapper Lil Nas X as King Tut, and the Afrofuturism pioneer Sun Ra’s interpretation of himself as a pharaoh.

All that was just fine for Erica van Leeuwen, who visited the exhibition out of curiosity and says anyone should be able to draw their own interpretations of history. “History is ages, ages ago; it’s ancient. The artists who identify with the old Egyptian culture, it’s how they feel and get inspired,” she says. “I mean, who am I to say you are not allowed to declare yourself part of my culture?”

Yet Egyptians are sensitive to this question of historical interpretation, says Dr. Hamdan, after 150 years in which colonial archaeologists from Europe have been “not just extracting artifacts, but telling Egyptians how they’re supposed to make sense of these things.”

And the government, led by President Abdel Fatteh al-Sisi, is making political capital out of the Netflix controversy, Dr. Hamdan suggests. As he tries to deal with a sour economy and to head off popular unrest, “he is saying he is fighting against Hollywood, defending Egypt from these external enemies. This is very much in the interests of the government – to blow the story up ... to latch onto culture war issues.”

The museum, which declined an interview request, stood by its Kemet exhibition, insisting that both “Eurocentric and Afrocentric perspectives” are important, as are contemporary Egyptian perspectives on ancient Egypt. Social media commentary has taken the content of the exhibition out of context, the museum said in a statement.

Interpreting history

Modern academics argue that race is a social construct. Indeed, the concept of race was developed millennia after the fall of ancient Egypt. And interpretations of race have always been subject to political and societal forces.

“It is a model for explaining differences, and of course it is already loaded with who is better and who is superior, who is inferior,” says Ulrike Dubiel, an Egyptologist affiliated with the Freie Universität in Berlin. “It goes horribly destructive, of course,” in the hands of the Nazis, she adds.

Egyptology itself has changed with the times; the Germans during the Third Reich depicted Egypt as more European than African, says Ms. Dubiel. “It was a matter of the Egyptologists having to justify why their discipline was relevant,” and, under the Nazis, that meant “whitewashing it.”

The Dutch museum’s approach was not “appropriation” in the way that Americans would define it, says Dr. Hamdan, who is Arab American. “In fact, it seems like they are just trying to expose people to relationships they didn’t realize existed.”

Perhaps the lesson is that the interpretation and reinterpretation of history should be expected, suggests Ms. Dubiel.

“We have more and more facts, and if you are a good scientist, you indeed look at all the facts that are available, and then you have to readjust your interpretation of those facts,” she says.

“And the sooner that we can acknowledge that we are always going to be interpreting history subjectively, the better,” says Dr. Atta, the Egyptian Canadian artist. “I think the idea that anyone is going to have access to a pure and unmediated vision of the past is an illusion.”

Museumgoers in Amsterdam seemed to be intrigued by what they learned. Priscilla Matkussa had never thought about Cleopatra’s race, but she came away realizing that many cultures have drawn inspiration from ancient Egypt.

Ms. Matkussa hails from Indonesia; her husband is Dutch; their 11-year-old boy Kymani is named after Jamaican reggae star Bob Marley’s son. With Frank Ocean playing in the background, the boy explains his approach to race: “Everybody is the same,” he says. “I see both colors” in Cleopatra. “We should all be happy whatever color anything is.”

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

The giving season’s new song

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

The weekend before Thanksgiving kicks off what is often called the “giving season.” Family and friends prepare to share food and joy for the U.S. holiday. People volunteer at soup kitchens. They begin to buy gifts for end-of-year celebrations. The burst of shopping on Black Friday and Cyber Monday has led to GivingTuesday, aimed at countering consumerism with caring. At the end of the season, or just before the new year, many people donate to charities for a tax deduction.

What may be new for 2023 is that some charities and nonprofits are asking if those on the receiving end of all this largesse ever have a say in how they are portrayed in appeals to donors.

For decades, fundraisers have usually relied on narratives and images that played to one of two stereotypes: the suffering of those in need, or the solutions to the problems of the “recipients” of other people’s generosity. The choice in framing – showing hungry children versus new wells for water – was often driven simply by which approach brought in more money. Many in the giving industry are challenging the either-or framing and, even more, who decides what to make a pitch.

The giving season’s new song

The weekend before Thanksgiving kicks off what is often called the “giving season.” Family and friends prepare to share food and joy for the U.S. holiday. People volunteer at soup kitchens or other relief organizations. They begin to buy gifts for Christmas, Hanukkah, and other end-of-year celebrations. The burst of shopping on Black Friday and Cyber Monday has led to GivingTuesday, aimed at countering consumerism with caring. At the end of the season, or just before the new year, many people donate to charities for a tax deduction.

What may be new for 2023 is that some charities and nonprofits are asking if those on the receiving end of all this largesse ever have a say in how they are portrayed in appeals to donors.

For decades, fundraisers have usually relied on narratives and images that played to one of two stereotypes: the suffering of those in need or the solutions to the problems of the “recipients” of other people’s generosity. The choice in framing – showing hungry children versus new wells for water – was often driven simply by which approach brought in more money.

Many in the giving industry are challenging the either-or framing and, even more, who decides what to pitch. The organizers of GivingTuesday, for example, proclaim that “every act of generosity counts” and “everyone has something to give.” Some charities are now letting the beneficiaries of aid tell their stories as they wish. In West Palm Beach, Florida, for example, Alzheimer’s Community Care sends out “Testimonial Tuesday” emails that share the tales of those impacted by the group’s work.

One reason for the rapid rise of platforms like GoFundMe is that donors can see the descriptions of those asking for money and connect with them in meaningful ways. The appeals that “always work best are the ones where the donor is hearing directly from the person who they want to support,” says Jess Crombie, a researcher at the University of the Arts London in the United Kingdom. “Authenticity is what you achieve with storytelling like that.”

Her research bears this out. In 2021, she and a colleague sent two different appeals for money on behalf of the charity Amref Health Africa. One was designed by the charity and the other by Patrick Malachi, a community health worker at Amref in Kenya, who had total control of stories and images. The result: More money was raised by Mr. Malachi’s appeal. Most of those who gave based on his narrative found an emotional connection and recognized that those being helped are helping themselves.

Ms. Crombie refers to people in need as “contributors” rather than recipients. While contributors don’t ignore their own needs, she finds, they don’t want to be defined by them. By being in charge, they retain a dignity of their choosing. There is not one universal way to experience dignity, she states.

She cites a proverb from Niger to explain why people depicting their own needs can evoke stronger empathy: “A song sounds sweeter from the author’s mouth.” During this year’s giving season, many charities are starting to let others do the singing.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

A higher perspective of running

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 4 Min. )

-

By Jay Frost

Seeking out a spiritual view of reality – rather than a limited, material one – brings inspiration and healing, as a runner experienced when faced with a painful foot condition.

A higher perspective of running

Ever since I was a child, I have loved to run. While I enjoy healthy competition, pushing limits, and tracking my workout progress, over time these runs have become less about how fast my body is moving and more about my spiritual growth.

One day, after finishing a run around a lake, I sat down by the water’s edge to stretch. I noticed a lot of buoys along the shore that were apparently arranged in no particular order. “What are those for?” I wondered.

A few minutes later I climbed to the top of the nearby bleachers to take in the view of the lake and noticed the buoys again. I was surprised to see that they were actually arranged in perfectly parallel lines, creating lanes for a boat race.

When I was sitting on the shoreline looking at the buoys up close, I couldn’t perceive any order or purpose in how they were arranged. But that was just my limited viewpoint, which turned out to be deceptive. When I improved my understanding of what was going on by looking from a higher angle, the design and usefulness were clear.

It dawned on me that this was analogous to the understanding of God and His creation as explained in Christian Science: No matter how confusing and messy the world may seem, there’s a spiritual view of creation that is logical and perfect and that we can trust and rely on. When we move past the lower view – a limited, physical perspective – and pray for inspiration from God, we achieve a higher view and gain a better understanding of God.

In “Miscellaneous Writings 1883-1896,” the discoverer of Christian Science, Mary Baker Eddy, writes, “To strike out right and left against the mist, never clears the vision; but to lift your head above it, is a sovereign panacea” (p. 355). Would it ever help to take things into our own hands by wading out to the “buoys” and trying to rearrange them in a way that makes sense from our limited perspective? No.

The truth is that God’s spiritual creation is already arranged perfectly and permanently, no matter what appears to be true from where we are humanly standing. When we pray to see a situation as God sees it – from the top of the bleachers, so to speak – instead of as it appears to a material outlook, healing occurs.

Several years ago, I experienced inflammation in the arches of my feet, which made walking and running uncomfortable. At one point, I called a Christian Science practitioner for Christian Science treatment.

During our discussion, it was brought to my attention that in Christian Science, inflammation is associated with fear, and I was afraid of never being able to run again because of the persistent sharp pain in my feet. The practitioner explained that I am a child of God and that the spiritual qualities of God that I reflect cannot be touched by any material conditions or diagnoses.

As the spiritual insights from that phone call sank in over the following days, I found myself letting go of my identity as merely a runner and gaining a clearer sense of my true identity as a spiritual idea of God. As a result, pride and obsession with the sport slowly faded, and so did the inflammation in my feet, which hasn’t returned. My perspective of the situation moved from the lower, matter-based angle to a higher view that approached the true, spiritual reality of my being.

Looking back, I realize that this healing is what started to shift my focus away from the physical aspects of running and toward its spiritual qualities, such as joy, vitality, and agility. Today I continue enjoying rigorous runs, races, and other sports activities whenever I can.

One of the ways it has come to me to pray is to put synonyms for God, as highlighted in the Bible and in “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures” by Mrs. Eddy, at the end of the phrase “powered by” and ponder what it means to be “powered by” God. For example, I might pray, “This run is powered by Principle, the divine law and basis for the activity of all of God’s ideas; this run is powered by Love, who tenderly cares for, protects, and guides.”

Whatever pursuits we may be involved in, we can affirm that all-powerful God, good, is ever present to perfectly govern all activity.

Adapted from an article published in the Sept. 4, 2023, issue of the Christian Science Sentinel.

Viewfinder

Time to clean up

A look ahead

Thank you for spending time with us today. On Monday, we hope you’ll keep an eye out for the next installment of our Climate Generation series. It’s reported from Bangladesh, where climate change determines where children live, how long they go to school, and when they will marry. The adaptability these young people demonstrate is their hope.