- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usMonitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Redwoods used 1,000-year-old trick to survive huge fire

Mark Sappenfield

Mark Sappenfield

We have plenty to discuss today, from climate conferences to the Ukraine war. But here is something for the science nerd in all of us (or at least me). Researchers have discovered that redwood trees in California survived a catastrophic 2020 fire by sprouting buds that began growing 1,000 years ago. The tissue grew under the bark and then paused until needed – a millennium later, it turned out.

The study shows the incredible resilience of the trees, which can draw on reserves stored for decades, even centuries. You can read about it here. In a week when much of humanity is focused on finding environmental balance, it is a reminder of nature’s extraordinary gifts all around us.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Beyond trendy vibes, summit addresses climate future

This week marks the United Nations’ COP28, the biggest climate conference in the world. It’s increasingly becoming something closer to a world’s fair – a place to see and be seen. But the need is still for unglamorous negotiating, and that heart still beats, too, if you look for it.

-

Taylor Luck Special correspondent

If climate change had a festival, sort of a Dreamforce meets Burning Man meets World Cup, but with undercurrents of existential anxiety, it would probably look something like COP.

That’s the annual United Nations gathering, or Conference of Parties, that is being held this week and next in the United Arab Emirates. The event has evolved from a buttoned-up meeting of scientists and diplomats into a slick, 70,000-person, world’s fair-like summit.

Despite the buzzy feel, conversations at the conference are taking on even more urgency. This year is poised to be the hottest on human record. In 2015, countries agreed to take measures to keep warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius, the number scientists say may limit the most catastrophic effects of global warming. But U.N. analyses show that the world is not on track to meet this goal.

Only a few days into COP28, there have been points of progress. World leaders agreed to set up a fund to help lower-income countries, which are disproportionately affected by climate change even though they didn’t cause it. COP countries also agreed on grant funding of more than $1 billion to reduce emissions of methane, a powerful heat-trapping gas. And they pledged money to climate-friendly agriculture.

Beyond trendy vibes, summit addresses climate future

If climate change had a festival, sort of a Burning Man meets Dreamforce meets World Cup, but with undercurrents of existential anxiety, it would probably look something like COP.

That’s the annual United Nations gathering, or Conference of Parties, that is being held this week and next in the United Arab Emirates, an event that has evolved from a buttoned-up meeting of scientists and diplomats into a slick, 70,000-person, world’s fair-like summit. (With, as scientists point out, the ecological future of the world at stake.)

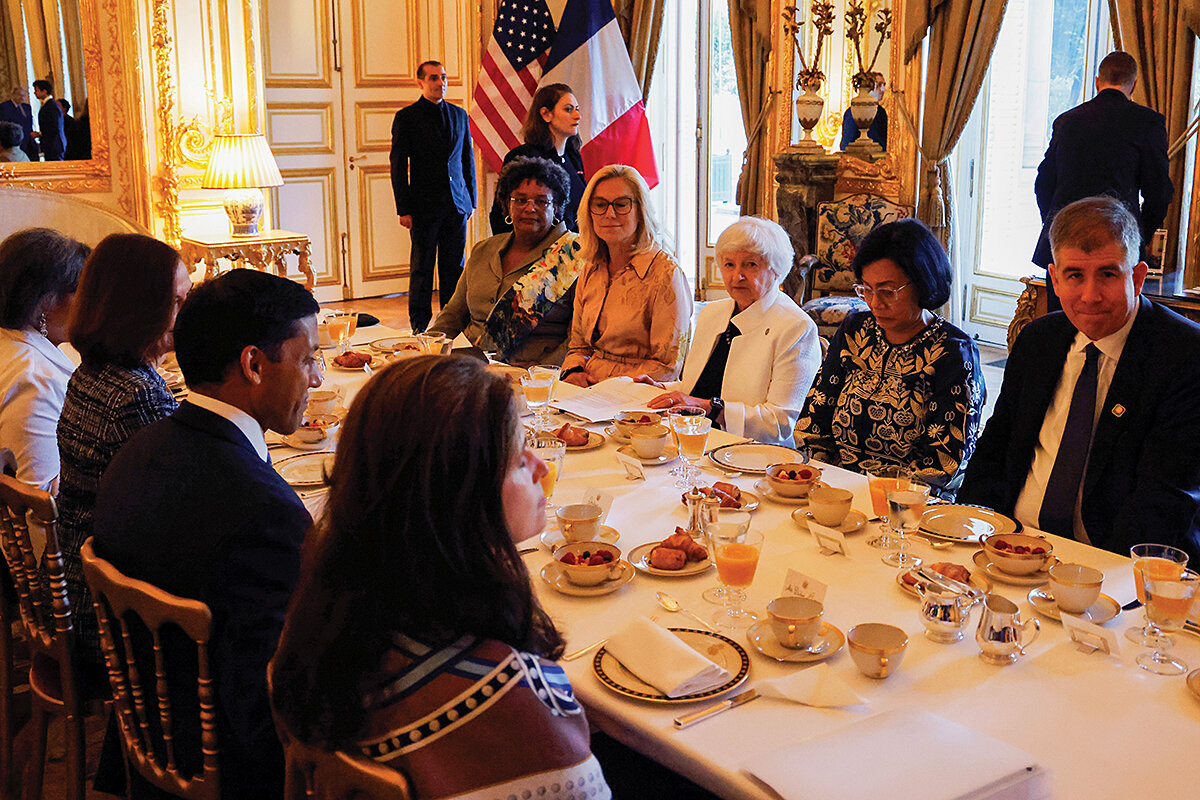

U.N. representatives and heads of state jostle alongside business executives and activists, journalists and protesters in the ultramodern city of Dubai. Keeping them busy are panel discussions, art exhibits, research presentations, and receptions, not to mention backroom negotiations, all focused on the challenges of – and possible solutions to – a rapidly heating world.

Despite the buzzy, Davos-in-the-desert feel, with princes and figures like Bill Gates heading sessions in front of high-tech LED screens, the heart of the gathering is still the crucial negotiations among U.N. members about how to respond to climate change.

And this year, these conversations are taking on even more urgency. Humans are noticing the effects of climate change like never before. And what’s happening here goes far beyond the performative. The cycle of annual summits – all the talks and the commitments that result from them – are viewed by many as the world’s best current mechanism for acting collectively on what’s increasingly seen as a planetary emergency.

“COP28 is coming at the end of a year that has really been defined by the climate crisis,” said John Podesta, senior adviser to U.S. President Joe Biden for clean energy innovation and implementation, referring to the summit’s acronym and the countries’ 28th such meeting.

The hottest day on record happened this past July 4, he pointed out. July was the hottest month ever recorded, and 2023 is poised to be the hottest year on record. Climate-related disasters cost the United States billions of dollars this year, he said. Other regions have been equally, if not more, affected, with flooding and fires, storms and droughts.

“Earth’s vital signs are failing,” warned U.N. Secretary-General António Guterres Friday at the opening of the conference.

In 2015, at the COP gathering in Paris, countries agreed to take measures to keep warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius, the number scientists say may limit the most catastrophic effects of global warming. But U.N. analyses show that the world is not on track to meet this goal. Diplomats at this year’s COP will participate in what’s known as a “global stocktake,” basically a review of how the world is doing when it comes to climate action and an agreed-upon road map for addressing any gaps.

But the “how” becomes a big question – and, this year, the cause of quite a bit of drama.

Advocates for climate action have expressed dismay at the growing number of fossil fuel industry representatives attending COP; this year, the president of the conference is Sultan al-Jaber, CEO of the Abu Dhabi National Oil Company.

These advocates worry about efforts to shift the storyline of climate action from the elimination of fossil fuels, which are responsible for about 75% of all greenhouse gas emissions, to decarbonization. That word is increasingly favored by industry to describe a future in which oil and gas production continue, but with new technology to minimize carbon emissions. (This carbon capture technology, while widely considered an essential tool against climate change, has yet to prove its effectiveness.)

There is also a sense among delegates that this year’s summit has morphed into something slicker, and more elitist, than previous conferences. VIP attendees, from philanthropists to tech moguls to heads of state, announce pledges and then retreat to plush lounges that only the 1% of the 1% can enter. Advocates worry that the highly produced announcements distract from the gritty, necessary efforts to combat and adjust to climate change.

But for all the controversies and inside-baseball maneuvering (watch for heated discussions about a fossil fuel “phasedown” versus a “phaseout,” or about whether the world works to eliminate fossil fuel emissions or “unabated” fossil fuel emissions), the point remains that facing climate change requires global cooperation.

“Addressing climate change is a global collective problem and a global collective challenge,” says Nathan Cogswell, research analyst with the World Resources Institute. “This process is really an opportunity for governments to get together to discuss strategies and plans and tactics and ways that they can collectively work on addressing the challenges.”

And only a few days into COP, there have been points of progress.

Soon after the conference opened, world leaders agreed to set up a fund to help lower income-countries, which are disproportionately affected by climate change even though they didn’t cause it.

This weekend, John Kerry, U.S. climate envoy, said the Biden administration would commit to not build any new coal plants and to phase down existing coal operations. COP countries agreed on grant funding of more than $1 billion to reduce emissions of methane, a powerful heat-trapping gas. They also pledged money to climate-friendly agriculture.

“There’s real power in having people, communities, governments come together,” Mr. Cogswell says. “To hear the moral calls from small islands, to hear the calls for greater action, and the need to address this crisis with everything we have, with all of society, and to hear the commitment that so many people and governments and communities have to do just that is extremely powerful.”

Stephanie Hanes reported from Northampton, Massachusetts, and Taylor Luck reported from Dubai.

A deeper look

An ‘aha’ moment becomes a nation’s alternative fuel

Our Climate Generation series is about young people finding new ways to address climate change through a shift in mindset. In Barbados, a group of students was tasked with finding a new green fuel for the island’s vehicles. Their answer surprised everyone.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 16 Min. )

Brittney McKenzie, a university microbiology major in Barbados, had been tapped in 2019 with a handful of other students to develop an alternative fuel source to power cars and trucks without releasing the greenhouse gases largely responsible for the planet’s rapid heating.

One morning, Ms. McKenzie was gazing out the window of a van taxi bumping along the island’s coastal road. She saw mounds of sargassum seaweed that had been choking beaches since 2011 and continues today.

She had an idea. She rushed to her lab and hurried up to her professor. “Sargassum,” she said, out of breath. What if they were to use seaweed as the new biofuel base?

Though skeptical at first, the professor has since led students to successfully develop production of a new biofuel that uses seaweed and sugar cane and commercialized the research in a company called Rum and Sargassum.

Other young entrepreneurs and innovators from what we call the Climate Generation are also using sargassum in sustainable technology unique to the Barbadian environment.

“We must have the cultural confidence to develop technologies of our own kind,” Prime Minister Mia Mottley said of the new trend of climate change-driven innovation and finance in a 2020 speech. “On a timeline that plays to our strengths and which captures the imagination of our own people.”

An ‘aha’ moment becomes a nation’s alternative fuel

The problem had been nagging at Brittney McKenzie ever since she began her summer internship.

A microbiology major at the University of the West Indies, Cave Hill campus, Ms. McKenzie had been tapped along with a handful of other students to come up with a way to transform Barbados’ transportation sector into a climate-friendly model for the Caribbean. The project was the brainchild of Professor Legena Henry, an international expert in renewable energy systems. And the mission, as Ms. McKenzie describes it, was to develop an alternative fuel source that could power cars and trucks without releasing the greenhouse gases largely responsible for the planet’s rapid heating, and that have been particularly devastating to small island states like this one.

But the young team had run into challenges.

It started off by focusing on sugar cane. Brazil had successfully converted most of its cars to run partially on sugar cane-based ethanol, and the team thought Barbados might do the same. But it quickly became clear that there wasn’t enough of that crop, a legacy of slavery, left on the island. The students knew they could use rum distillery wastewater in their project. But they were stumped on what to mix with it to produce enough gas to power a car.

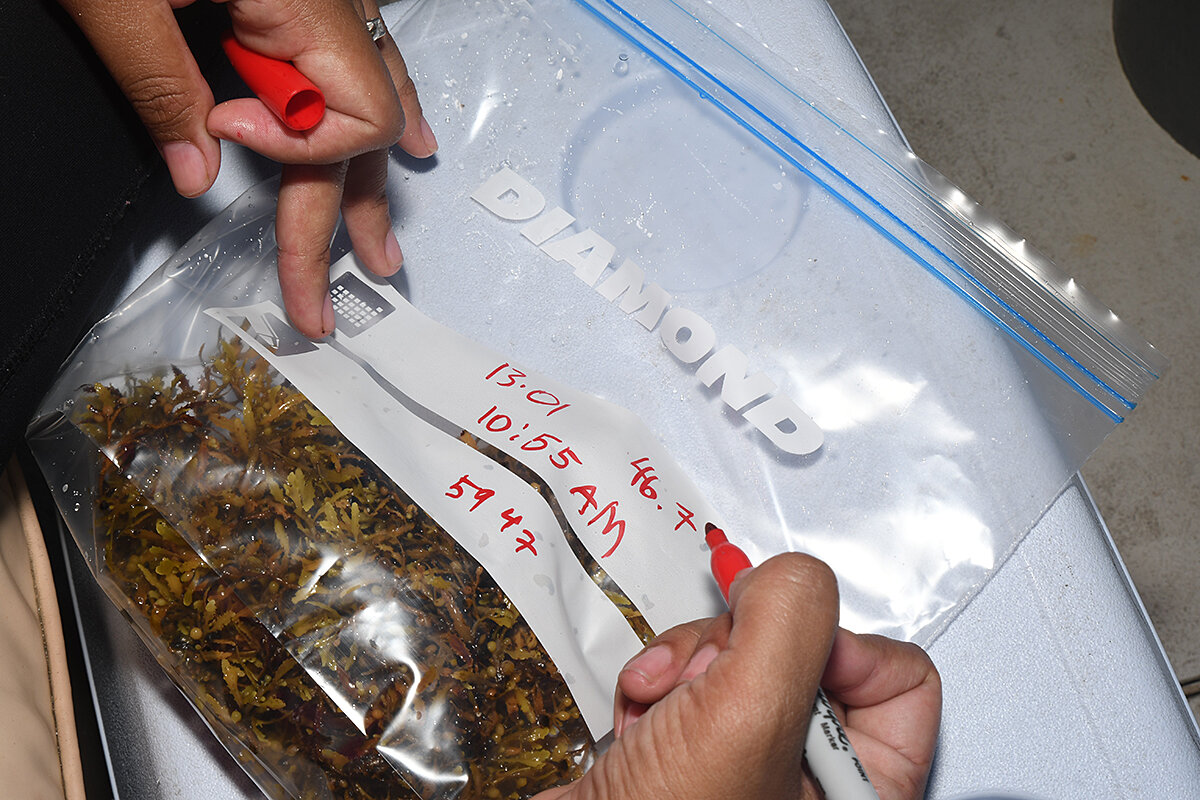

Then, one morning, Ms. McKenzie was gazing out the window of the van taxi she took to campus, bumping along the pockmarked coastal road that circles this easternmost Caribbean island. Her eyes lingered on the mounds of sargassum seaweed that had been choking beaches in 2019, part of an influx that began around 2011 and continues today.

She had an idea. By the time she got to campus, she couldn’t wait to share it. She rushed to her lab, pushed open the doors, and hurried up to Dr. Henry.

“Sargassum,” she said, out of breath. What if they were to use seaweed as the new biofuel base? Island officials had been struggling to figure out what to do about the increasing amount of foul-smelling sargassum inundating their shores, an explosion exacerbated by warming ocean temperatures. Using seaweed to make climate-friendly vehicles would be a win-win, Ms. McKenzie declared.

Dr. Henry sighed inwardly. There was already existing research casting doubt on sargassum’s use as a biofuel source.

She almost said no.

But to get to climate change solutions, she knew she needed to let the young people follow their hunches and ideas and excitement.

What happened next is a story about young people, innovation, and solutions, and the way countries like this one – small, climate-vulnerable Barbados – are becoming global leaders of climate adaptation and innovation.

From individual entrepreneurs and groups of young researchers to the country’s prime minister herself, Barbadians are developing new ideas and approaches to everything from climate technology to climate finance. Young people, who’ve traditionally emigrated from Barbados for better opportunities abroad, are starting to imagine – and build – a home-based future for themselves in sectors such as clean energy, sustainable design, and climate-friendly agriculture.

Dr. Henry, a Trinidad native who studied at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, started her lab here because she believes in the power of young people’s enthusiasm and creativity. It was a philosophy she learned from her mentors in college, she says, and one that has felt even truer in her field of climate change solutions.

Around the world, members of the Climate Generation – as we call the cohort born since 1989 – are transforming everything from food systems to the construction industry to technology, all with a climate lens in mind.

While these young climate innovators may be connected through green incubators or United Nations innovation groups or nonprofit-sponsored climate solution challenges, they don’t necessarily consider themselves part of a global movement, in the way of, say, the climate strikes started by Swedish teenager Greta Thunberg.

Many don’t consider themselves climate activists; some shrug away questions about how climate change motivated their work. Some talk about “eco-anxiety,” or stress around what a heating world might mean for the future; others say it’s just something they’ve absorbed. To them, climate change is simply an ever-present fact, a reality learned in school. And if it is a threat looming along the Caribbean blue horizon, it is also opening new sectors and opportunities.

Together, these Barbadian innovators and others like them across the Global South are reshaping their world, says Jules Pretty, professor of environment and society at the University of Essex in England.

“The climate crisis opens up opportunities for innovation,” he says. “New things will happen that completely shift and undermine what look like very stable businesses, sectors, operations.” Young people, he says, “know that something must be done, and they know the future belongs to them.”

Getting island cars off fossil fuels by 2030

Dr. Henry wanted to tap into this energy in the Caribbean, a region that has long faced disproportionate challenges to innovation, from a lack of financial investment to the brain drain of educated young people who don’t see professional opportunities at home.

At first, she taught in Trinidad, but she quickly found that her work put her on the fringes in her oil-rich homeland.

“It was like, ‘Oh, isn’t that cute,’” she says, recalling the way colleagues there reacted to her research on renewables.

So in 2019, she accepted a position here in Barbados, a country that was on the front lines of both climate vulnerability and innovation.

Barbados is a relatively flat 167-square-mile land mass (no bigger than the city of New Orleans) on the eastern edge of the Antilles. Though located within the region’s hurricane belt, it has tended to avoid direct hits from these storms – at least in recent history. Some locals attribute this to the divine. (“God is a Bajan” is a common phrase here.) But meteorologists attribute it to something called the Coriolis force, a sort of atmospheric deflection caused by trade winds and Earth’s rotation that pushes hurricanes north of the country.

Recently, though, storms have become stronger. Flooding has increased, and officials worry about accelerated erosion. Heat waves keep the humid air hanging like a blanket, day and night. And a number of officials worry about what could happen if climate-

related changes to the region’s currents and winds end up sending a hurricane directly over the island.

But even without this speculation, Barbados’ government recognizes it needs climate-friendly solutions. Some of this is because of the threat of natural disasters. But it is also because of finances.

Barbados imports fossil fuels for about 95% of its energy load. And it has among the highest electricity prices in the region, at around 30 U.S. cents per kilowatt-hour, according to 2020 data from the Caribbean Development Bank. (That’s about double the U.S. rate.) The country also imports the bulk of its food – contributing to climate change and making it vulnerable to storms, port damage, and rising fuel prices.

But like many small countries, Barbados doesn’t have the international heft to change world energy systems or impact prices at the pump. Add to that the country’s substantial international debt, and many officials here say they are financially and ethically trapped in the status quo fossil fuel system – unless there are changes.

“We don’t produce or consume enough oil and gas or other energy products to influence the supply and demand chains,” Prime Minister Mia Mottley said in a 2022 speech. “But we suffer the effects of prices that we can hardly bear. ... Each day, we devote a high percentage of our time, our energy and our intellectual capacity looking for new ways to cushion the shock of our nation.”

Ms. Mottley has been attracting increasing attention, and a larger international platform, for her insistence that the world must overhaul its financial systems to address climate change, and for her innovative policy proposals to do just that. Not only must international banking institutions create new policies to alleviate debt pressure in the face of climate disasters, she and her administration have said, but also there should be new ways to unlock private capital to support climate innovations in developing countries. She and her government have also made their own climate pledges at home, such as getting cars and trucks off fossil fuels by 2030.

A solution tailored for Barbados

That initiative was the focus of Dr. Henry’s lecture one morning in 2019, when she says a student challenged her assumptions and helped spark what would become a new biofuel initiative.

She had been talking to the class about electric cars, she recalls, which were a relatively new technology for the island in 2019 and widely touted as the future of clean transportation. She was excited about the prospect of ditching gas-guzzling vehicles, and about Barbados’ efforts to build a small but growing fleet of electric alternatives.

But a student at the front of the classroom raised her hand.

“She’s like, ‘Well, Dr. Henry, I can’t buy an electric car,’” the professor recalls. “‘So you can tell me we are going to have to drive electric cars by 2030. But there’s no way I’m gonna buy an electric car between now and 2030.’”

The professor was taken aback. But then, she says, “I thought of my electricity bill, and I was like, ‘Yeah, me neither.’”

It got her wondering: What was the solution for people such as her students, or for her – everyday folk who couldn’t shell out tens of thousands of dollars for electric cars or hefty electric bills? In other words, what was a climate solution that could actually work for Barbados?

If anyone was going to have that answer, she thought, it would be her students. She asked a group to spend a summer working with her with the goal of transforming the Barbadian transportation sector.

So now Ms. McKenzie was in front of the professor, breathlessly talking about seaweed.

“I wanted to say no,” Dr. Henry recalls. But then she remembered her professors in Cambridge, who never shut down a student’s idea. “And I said, ‘Brittney, if you are going to be this happy and this enthusiastic for the next six weeks, then sure, go in the lab and test sargassum.’”

Within days, Ms. McKenzie says, she realized she had found the climate solution.

The mixtures she was testing were producing more biogas than their lab bottles could hold. Dr. Henry was astounded. The team continued its work, tinkering with and recording the results of different chemical reactions. It published its findings, and then spoke with Barbadian government officials. By the end of the summer, representatives of the Inter-American Development Bank had reached out to get briefings. Soon, university administrators suggested to Dr. Henry that she might want to commercialize her research.

Later that year, Dr. Henry traveled to New York City to present the findings at a U.N. global climate solutions summit. She caught the attention of representatives from the Blue Chip Foundation, which directs early funding for sustainability efforts. After learning more about Ms. McKenzie’s discovery, the foundation pledged $100,000 in seed money for the project.

The professor founded Rum and Sargassum, a company that would continue to develop and market this new biofuel, in partnership with her continuing flow of students.

Investing in creativity

Climate financing is at the center of a lot of debate these days – in particular, when it comes to how and whether wealthy countries, which are disproportionately responsible for the world’s greenhouse gas emissions, should support lower-income countries like Barbados, which are disproportionately suffering from what those gases have done.

But as Ms. Mottley and her climate envoy, Avinash Persaud, have reiterated to international leaders, most funding for the world’s climate adaptation and mitigation efforts will come not from foreign aid, but from within the private sector. Mr. Persaud regularly points out that the world needs to invest $2.4 trillion a year to address climate change. It’s a mind-bogglingly massive number that comes from a U.N. expert report and suggests the clear need for some innovative solutions. The amount of foreign aid distributed now by all countries for all purposes, after all, is around $200 billion.

Governments still have a role, though. In 2022, the United States, China, and the European Union invested a combined $867 billion in climate sector research and development, as well as innovation grants and other early-stage business efforts, according to the market research firm BloombergNEF. This gives entrepreneurs and inventors needed cash before they can attract private sector investors. Private sector financiers have also become increasingly interested in climate initiatives, with climate-oriented equity transactions increasing more than 2.5 times between 2019 and 2022, according to the consulting firm McKinsey.

But relatively little of this capital has flowed to the developing world. This isn’t because there aren’t climate ventures there. To the contrary: Entrepreneurs here say that they are, in many ways, best positioned to innovate when it comes to climate solutions.

“In Barbados, we ... are living the changes and the disruptions,” says Joshua Forte, a 29-year-old Barbadian entrepreneur whose company, Red Diamond Compost Inc., is part of a climate business incubator here. “But innovations come because you have some type of difficulty or conflict. It stretches the mind [and makes one] a lot more creative.”

The problem, explains Anderson Lee, a research associate in the World Resources Institute’s Finance Center, is that structural factors penalize investors for financing projects in countries like Barbados.

Investments in the developing world often carry what’s called “foreign exchange risk” – or the chance that the local currency might lose value. They also might carry political risks, or the chance that government actions could impact the business, whether by nationalizing industries or creating civil unrest or making any number of risky policy decisions. While financiers can hedge those risks with what’s basically bank-backed insurance, this adds cost to an investment.

“The reason why investors are not investing a lot in developing countries is not because of the projects per se,” Mr. Lee says. “What really is blocking a lot of private financing going to developing countries is the cost of capital on the macro level.”

This means that many entrepreneurs in Barbados, and other less wealthy countries, struggle to get funding. And without investment, many great ideas never make it out of concept stage.

“We don’t have the same entrepreneurial pipeline” as in the U.S., says Debbie Estwick, a design and innovation strategist who was the country lead for ClimateLaunchpad Barbados, part of one of the world’s largest green-business ideas competitions. “You can go from [business] competition to competition, but it’s never enough.”

This is a problem not just for Barbados and countries like it, but for the world.

That’s because those places on the front lines of the climate crisis are, in a lot of ways, most likely to come up with the solutions that the whole world might soon need. In other words, young people who most need climate innovation today could be crucial first responders in a crisis that much of the world has been able to push out of mind – if they have the resources.

“We must have the cultural confidence to develop technologies of our own kind,” Ms. Mottley said in a 2020 speech. “On a timeline that plays to our strengths and which captures the imagination of our own people.”

An idea dawns while growing greens for pet iguana

Mr. Forte had always wanted to be an entrepreneur, ever since he woke up early before school in order to catch Bloomberg News on TV at his mother’s modest home in Weston. He spent hours on YouTube, researching tips and techniques for starting a business.

It was in college, after he started growing leafy greens for a pet iguana (a way to cut back on pet care costs) that he started wondering why there weren’t more places to get high-quality, locally grown food for humans.

Mr. Forte remembers being troubled by his island nation’s reliance on imported food, both because of the climate footprint of importing goods across the ocean, and for what he saw as health drawbacks of processed and industrially produced food.

He decided to grow greens for himself, as well. But he couldn’t find a commercially available compost that met his standards. So he decided to make one himself – and realized that he had stumbled across a business.

“This was 2014, and in the U.S. the compost industry was booming,” he says. “You were seeing a lot of companies raising millions of dollars here and there, all these new technologies, really exciting stuff.”

He began by building traditional compost piles in his mother’s backyard. But soon, he decided to test sargassum as a base for an organic “agro-enhancement” product that would both improve soil health and help plants grow better. He collected bags and bags of the seaweed and started experimenting with it in his mother’s kitchen, using her stove to cook different ingredients and her counters to hold his lab equipment.

Much to her relief, he says with a smile, he has since invested in his own processing facilities, the newest of which he plans to open later this year. He now has three full-time employees and a product line that focuses on liquid fertilizer, which he calls Liquid Sunshine, and a Supreme Sea Biostimulant that increases plant germination rates. He supplies Barbadian gardening centers and says he is in the process of contracting with companies in the U.S., the United Kingdom, Africa, and other Caribbean islands.

His goal is not just to export his own product, he says, but also to consult with farmers on how to replicate his process within their own local environments.

He says he’s been fortunate to have his business included in the Bloom Cluster, a Barbadian clean-tech incubator that houses entrepreneurs working on everything from solar energy to bioplastics to an electric vehicle rental service. But finding long-term funding has been a perpetual struggle, he says. And he is one of the entrepreneurial survivors.

“I can tell you firsthand ... there are a number of my colleagues who, for one reason or the other, have abandoned their projects because of lack of support,” he says. “And they’re really talented people with really great ideas. But, you know, you need that [entrepreneurial] ecosystem to be able to be successful.”

But he also says that he sees changes.

“We’re starting to see more private sector investment companies and investors starting to have an interest in ... clean-tech projects in Barbados and the Caribbean region because of this macro shift in the atmosphere,” he says. “It’s definitely happening.”

Sharing innovation abroad

On one humid afternoon earlier this year, Shamika Spencer opens the door to the back room of Dr. Henry’s Renewable Energy Teaching and Research Laboratory, an air-conditioned space of computers and classroom tables in a small cement university courtyard.

The 28-year-old is monitoring dozens of glass bottles containing different combinations of rum distillery waste product and sargassum and using the results to work on her thesis, which will also help shape Rum and Sargassum’s business product. Dr. Henry has continued to tap young people to both pursue her biofuel research and help design her business – an effort that, the professor says, will help build the sort of climate solutions the world needs.

“Ah, you see this one here? The water level is down,” says Ms. Spencer, checking her beakers. This is an indication that a particular concoction is releasing more gas.

Rum and Sargassum has been getting increasing attention around Barbados, as well as funding. This year, it finalized a contract with the Barbados National Oil Co., which is re-branding itself as an “energy” company. Dr. Henry says her own car is being converted to run on Sargassum and Rum’s biofuel next year as a prototype.

This spring, Ms. Spencer traveled to the University of San Diego to work with faculty and students in the department of environmental and ocean sciences, as well as with the Shiley-Marcos School of Engineering. Her mission was both to share her findings and to bring insights from her work in Barbados to American researchers looking to develop biofuel from their own local waste products, such as kelp and beer wastewater.

For three months, Ms. Spencer worked with other scientists as they tested possible inputs for biofuel, from fish remains to sheep waste to kelp. She figured out that when they weren’t getting results similar to those the Barbadian team had recorded, they should look at the diets of the animals whose waste they were incorporating into their experiments. The American sheep, for instance, were not grass-fed like their Barbadian counterparts – and that made a huge difference when it came to biofuel production.

Today, Ms. Spencer is working to finish her thesis, monitoring rows of beakers in the back room. She isn’t sure if she wants to continue in business – she likes academic research more than commercial pursuits. But she is eager to share the innovations that she and others are finding in this small laboratory on this small island. And she is embracing her role as a climate ambassador for a region and a world craving solutions.

“Every time I do a seminar, or a presentation, I talk about climate change,” she says. “We need to be fossil fuel-free by 2030. This project is actually helping with that.”

War pushes Ukrainians away from Russian language

For many bilingual Ukrainians, the choice to now speak Ukrainian is a protest and a statement of identity. We chat with some who are making the switch – from a YouTube influencer to members of a Ukrainian class – and one woman who isn’t giving up on Russian. “Russia does not own my Russian language,” she says.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine last year, the Russian language was critical to the livelihood of Anton Ptushkin, who grew up 45 minutes from the Russian border.

Mr. Ptushkin made content for almost 5.6 million YouTube subscribers, mostly in Russian. But after Feb. 24, 2022, he decided to switch to Ukrainian, even if that meant losing part of his audience.

In a nation where many people are bilingual, the language people choose to speak is an emotionally charged topic during war. Russian President Vladimir Putin argued his invasion was justified in part by claiming that Russian speakers needed to be defended.

But for many Ukrainians, the war with Russia has proven reason to bolster their Ukrainian usage – and for some to abandon usage of Russian entirely. Whether driven by repulsion from Russia or patriotism for their own nation, Ukrainians are changing their lingua franca.

Data from the end of 2022 shows that across Ukraine, 62.6% of respondents reported speaking Ukrainian at home, while 19.2% said they speak both languages, and 15.8% said they spoke Russian. That’s compared with data from 2017, when only 49.9% said they spoke Ukrainian at home, 23.9% spoke both, and 25.8% spoke Russian.

“It was a no-brainer for me,” says Mr. Ptushkin. “I don’t have any other choice because for us, it’s also a cultural war.”

War pushes Ukrainians away from Russian language

Russian had always been Kyiv native Olena Bondarenko’s mother tongue. That all changed with the invasion and accompanying atrocities last year.

“After Bucha, Hostomel, Irpin, and what was discovered, I just can’t speak the Russian language,” she says. “It’s the language of the aggressor and the language of the occupier.”

That was what inspired her to come to Anna Pastushok’s weekly Ukrainian conversation group in central Kyiv. But not all the group’s attendees had the same motivation.

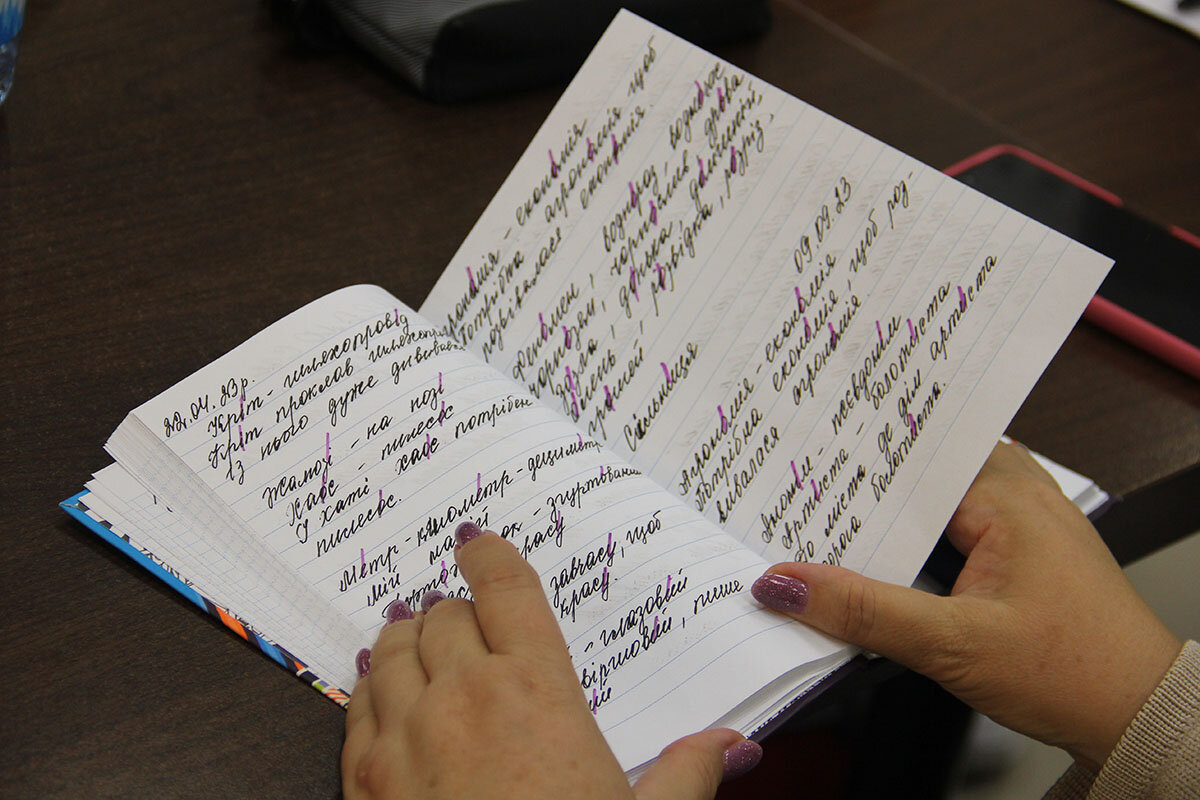

“For me, the Ukrainian language is about Ukrainian culture and nurturing it,” says fellow classmate Sasha Voloshchyk. She brought her 5-year-old son, Lev, to the class and showed a home video of them practicing pronunciation emphasis. Originally from the southeastern city of Zaporizhzhia, she switched to speaking Ukrainian in 2017. “When I made the switch, I wasn’t really repelled by Russia. It was simply the attraction of Ukrainian culture and its preservation and respect for my language in my country.”

Whatever their motivation, the students are part of an ongoing movement in Ukraine of people choosing to switch from speaking Russian to their country’s official language: Ukrainian.

In a nation where many people are bilingual, the language people choose to speak is a personal decision and an emotionally charged topic during war. Russian President Vladimir Putin argued his invasion was justified in part by claiming Russian speakers needed to be defended.

But for many Ukrainians, the war with Russia has proven reason to bolster their Ukrainian usage – and for some to abandon usage of Russian entirely. Whether driven by repulsion from Russia or patriotism for their own nation, Ukrainians are changing their lingua franca – and their society.

Language and statehood

Ms. Pastushok’s class, part of a free 28-day online course through the group Yedyni (whose name means “united ones” in Ukrainian), is one example of such efforts to spread the use of Ukrainian. During the conversation group, the students play card games and ask Ms. Pastushok about pronunciation. “People don’t just need knowledge, but also psychological support in the transition because it is difficult,” she says.

Over 102,000 people have already taken Yedyni’s course over the past 19 months, says the group’s co-founder Natalka Fedechko. Perfectionism and embarrassment are the biggest psychological barriers.

Suppression and banning of the Ukrainian language dates back hundreds of years. During Soviet times, Russian was the language used to get ahead in careers, and Ukrainian was perceived as a lesser, village language, Ms. Fedechko says. “This inferiority complex, unfortunately, still exists.”

Ukrainian became the state language in 1989, but at first there was no strict implementation. In 2019, Ukraine adopted a new language law, making Ukrainian the default language in many social domains – not just state offices but private companies, too. Quotas in film, TV, and radio also increased the use of Ukrainian.

The trend “is a gradual shift ... from Russian to Ukrainian,” says Volodymyr Kulyk, a visiting scholar at Stanford University who has been studying language practices and attitudes in Ukraine for the last 20 years. “It was very slow until 2022.”

The latest available data from the end of 2022 shows that across Ukraine, 62.6% of respondents reported speaking Ukrainian at home, 19.2% said they speak both languages, and 15.8% said they spoke Russian. That’s compared with data from 2017, when only 49.9% of Ukrainians reported speaking Ukrainian at home, 23.9% reported speaking both, and 25.8% said they spoke Russian.

It will likely be years before researchers will be able to judge the impact of the war on Ukrainian language usage.

Natalya Pipa, a member of Ukraine’s parliament who works on the Ukrainian language environment of educational institutions, says support for the Ukrainian language is growing, but there is still a long way to go.

While some soldiers on Ukraine’s front lines speak Russian, Ms. Pipa argues that everyone who isn’t serving should have the time to study. “Language and statehood are very much connected,” she says.

“It’s also a cultural war”

Before the invasion, Russian was critical to the livelihood of Anton Ptushkin, who grew up in Luhansk, 45 minutes from the Russian border. Mr. Ptushkin co-hosted a popular Russian-language travel show that was broadcast in several countries before making his own content for almost 5.6 million YouTube subscribers. To be successful meant knowing Russian, and Moscow offered much bigger salaries for entertainers.

For Mr. Ptushkin, everything changed on Feb. 24, 2022. He decided to switch to publishing in Ukrainian, even if that meant losing part of his audience. “It was a no-brainer for me. I don’t have any other choice because for us, it’s also a cultural war,” he says. “This is a historical chance to cut these bonds with Russia.”

Some followers were unhappy and even accused him of being paid to switch. Mr. Ptushkin says it was a “100% conscious decision” not to make any Russian content. He estimates that a little less than half of his current YouTube audience is Russian.

Ukrainian was in Mr. Ptushkin’s subconscious, but learning hasn’t been easy amid the lingering stress of war, which research suggests impacts memory and cognitive skills. He has been reading Ukrainian books and building his vocabulary.

Over a year ago, Mr. Ptushkin and his friend Misha Katsurin decided to film a YouTube show about food across Ukrainian cities and to speak in Ukrainian. He hopes growing Ukrainian YouTube content will help younger Ukrainians develop their skills.

Divergent views

Not all Ukrainians have felt compelled to abandon the Russian language. Some, like Olha Chuyeva, hold on to it in spite of Moscow’s campaign.

Ms. Chuyeva was born in Belarus to two ethnically Russian parents but was raised by Russian-speaking relatives in Yalta, Crimea, following her mother’s death. Ms. Chuyeva says she never felt any attachment to the Russian government, and she moved to Kyiv in 2014 following Russia’s annexation of Crimea.

Sitting in her apartment in central Kyiv where Ukrainian flags hang, Ms. Chuyeva says she has not fully shifted to speaking Ukrainian. “Russia does not own my Russian language. Russia has not usurped the Russian language,” she says, speaking in flawless Ukrainian. “And I don’t want to give it up until I decide I will.”

Russia has taken a lot away already. “The language of the aggressor is theirs. But for me, there is my Russian language that is tied to my own personal history and has nothing to do with Russia,” she says.

Ms. Chuyeva will not speak Russian out of respect to anyone who doesn’t want to hear it, and she argues that Ukrainian should be the state language. But she also says that Ukraine should be a democracy and people should have choice in what they speak. She thinks an approach of “gentle Ukrainization” will be more attractive to people. “You don’t have to force it; you have to wait,” she says. “That can sound cynical; there are people who won’t change. They grew up in the USSR.”

Others are not so willing to accommodate.

Oleksandr Shevchenko, 26, is “super aggressive” about the language question. It’s a big change for the information technology manager who grew up in the eastern Ukrainian city of Kharkiv speaking Russian and Surzhyk, a hybrid mix of Russian and Ukrainian.

On the first day of the full-scale war, Mr. Shevchenko heard explosions soon after waking up. He started writing a social media post in Russian “about how bad the Russians are,” but he stopped when he thought that voicing his complaint in Russian “isn’t right, it shouldn’t be this way.”

Mr. Shevchenko instead wrote his post in Ukrainian, and that was the moment his full change began. He moved to the western city of Lviv and began reading Ukrainian books, listening to Ukrainian music, and eschewing Russian entirely. These days, the only Russian he will speak is to his elderly grandparents, and he thinks that people should feel a responsibility to speak Ukrainian. But Mr. Shevchenko also says he is cynical and thinks if people haven’t already switched to Ukrainian, they won’t.

When asked why he ultimately made the switch he responds with a question: “How else could it be?”

Visitors breathe new life into Kashmir’s battered border villages

Once India and Pakistan agreed to stop shooting at each other in Kashmir, a wonderful thing happened: Tourists came. The visitors are of the hardier sort – navigating bad roads and military checkpoints. But the village of Keran shows what peace can do. And it has bigger dreams.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

-

By Durdana Bhat Contributor

In Keran, India, sounds of shelling have been replaced by camera shutters. Bunkers have been converted into homestays. And instead of appearing in headlines about military operations, the riverside village is being promoted as a “hidden gem” for adventurous travelers.

Two years after India and Pakistan recommitted to a cease-fire along the countries’ de facto northern border, Keran and other frontier hamlets are shedding their war-torn image and playing happy hosts to outsiders.

Locals say 2023 has witnessed unprecedented foot traffic, and new inns and eateries have sprung up to accommodate tourists. India’s central government has also been investing in road improvements in remote border areas.

Though challenges and trauma remain, residents agree that the influx of visitors is breathing new life into the village, providing a vital source of income and fostering greater awareness about life on the border. Some tourists come specifically to photograph deserted wooden homes, abandoned years ago by families fleeing violent insurgency, or to compare this village with the one sitting just across the closely guarded river: Keran, Pakistan.

“It seems that the other side of the border is more developed in terms of infrastructure, roads, and electricity,” notes Bilal Ahmad, who came to Keran after learning about the village on Instagram.

Visitors breathe new life into Kashmir’s battered border villages

A major transformation is underway in the riverside village of Keran, India. The once ubiquitous sounds of exploding shells have been replaced by the clatter of camera shutters. Bunkers have been converted into homestays. And instead of appearing in headlines about terrorist infiltrations or military operations, Keran is being promoted as a “hidden gem” for adventurous travelers.

For decades, village residents had to dodge cross-border fire during frequent violations of a cease-fire declared at the end of the India-Pakistan war in 1971. But two years after the two countries recommitted to the cease-fire along the countries’ de facto northern border, Keran and other frontier hamlets are shedding their war-torn image and playing happy hosts to outsiders.

Locals say 2023 has witnessed unprecedented foot traffic. Some estimate that tens of thousands of people have visited Keran so far this year, and new inns and eateries have cropped up to accommodate tourists. India’s central government has also been investing in road improvements in remote border areas.

Residents welcome the shift, expressing pride that their hometown is now “on the map.” Though challenges and trauma remain, they agree that the influx of visitors is breathing new life into the battered village, as well as fostering greater awareness about life on the border between the two traditional enemies.

“With the return of peace,” says local cleric Iftikhar Khan, “the village’s newfound tourism industry is becoming a vital source of income.”

On the map

Guns have fallen silent in this formerly hostile corner of Kashmir, a predominantly Muslim and heavily militarized region in northern India that shares a contentious border with Pakistan.

Surrounded by towering peaks and pine-clad slopes, Keran lies some 60 miles northwest of Srinagar, the summer capital of the Jammu and Kashmir region. Watchful sentries guard the banks of the Kishanganga River, which flows into Pakistan-administered Kashmir as the Neelum River.

Access to such border villages used to be extremely limited. But following the reiteration of the cease-fire agreement in February 2021, the Jammu and Kashmir administration decided to open these no-go zones to tourists.

Still, reaching Keran is no easy feat. Visitors face not just a high-altitude mountain pass but also five military checkpoints. At the final stop, they must submit their identity cards, and the village remains under strict surveillance.

“Traveling to Keran was not a pushover,” says Shakir Baba, a tourist from central Kashmir. “The problem here is with the phone connectivity and the road connectivity; the last kilometers of Keran [roads are] dusty, and it’s very difficult to drive on this terrain. Most of the time the cars get stuck.”

Dilip Kuman from Noida, India, agrees that the final miles were tough to navigate – but judging by the pace of road work around Keran, he doesn’t think that will be a barrier for long. Once the roads improve, he predicts that the valley will see rapid development. “People here are nice,” he says. “They are loving.”

And for his photographer wife, Keran’s natural beauty was well worth the trouble.

“People trek miles in order to reach a place like this,” says Gita Singhaniya, pointing her camera on its tripod towards the Kishanganga River. “The government’s decision to open this border area has been fruitful. It has given immense happiness to see this beautiful place.”

Locals are eager to share the valley’s history, too. For instance, few visitors know that India’s first post office sits along the Kishanganga River, predating independence and the 1947 Partition of India. “It never stopped its services,” says postmaster Shakir Bhat.

A community divided

After decades of intermittent hostilities, people here are beginning to relax, says Mr. Bhat, and are finding new ways to earn a living from the influx of visitors. He was among the first villagers to convert his wooden home into a homestay for tourists, charging around 1,000 rupees ($12) per night for a single room, or around 600 rupees ($7) per night for a tent in his courtyard.

The septuagenarian runs the homestay with his wife, daughter, and sons, and the extra income has brought the family hope and financial security.

Yet Keran remains a divided village, lying on both sides of the border. No amount of tourist dollars will restore lost lives or heal broken families. The cease-fire has brought a sense of normalcy and new economic opportunities to Keran, but it has not opened the border.

After an uprising against the Indian state broke out in majority-Muslim Kashmir in the 1990s, “many villagers migrated to the other side of the river to escape from the daily mayhem,” says Aurangzeb Khan, looking at the staffed checkpoints stationed on what used to be open grasslands. “My brother and his family, my wife, two daughters, two sons – they all went to the other side and never returned.”

These narratives of loss and longing are now finding voice in tourist experiences and travelogues. Indeed, many visitors come to Keran specifically to learn about life near India’s most volatile border. They photograph deserted wooden homes, abandoned years ago by families such as Mr. Khan’s, and compare Keran, India, with the village sitting just across the river: Keran, Pakistan.

“It seems that the other side of the border is more developed in terms of infrastructure, roads, and electricity,” says Bilal Ahmad, a Kashmiri visiting Keran after seeing a video about the village on Instagram. “The opposite village is ... well maintained, and the double-storied wooden houses are scattered over the Neelum Valley.”

At night, many tourists watch as locals trek to the riverside, light up their phone flashlights, and wave to relatives across the water. In a region with poor phone and internet connectivity, this is the primary form of contact for many cross-Keran families.

Mr. Khan, who is now in his late 80s and starting to lose his sight, makes this journey every day, coming down from the mountains just to gaze upon his daughter who lives on the other side of the border. “Too near,” he whispers, “yet too far.”

Points of Progress

How Indigenous people’s work can save crucial ecosystems

Our roundup of global progress also speaks to the resilience of nature and human efforts to help. Scientists and the Indigenous community are teaming up to protect a key ocean ecosystem in Canada, while women in Brazil are collecting the seeds that could drive reforestation.

How Indigenous people’s work can save crucial ecosystems

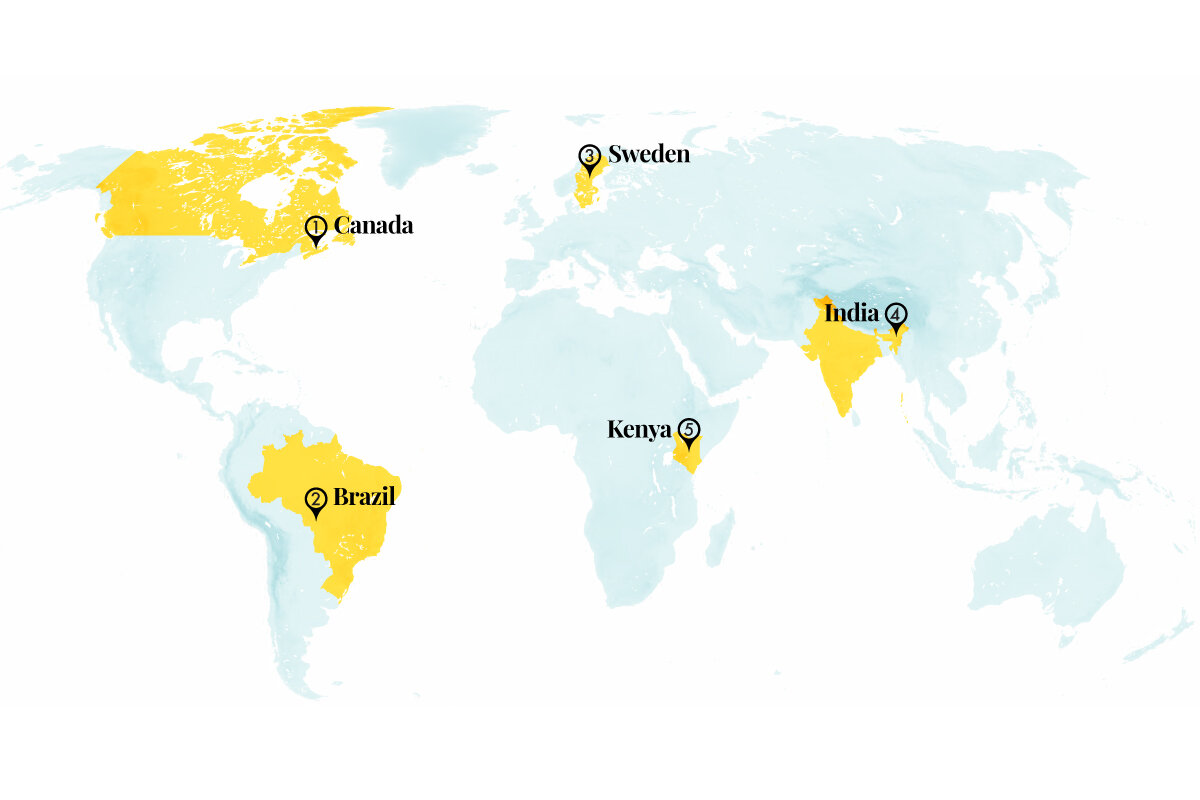

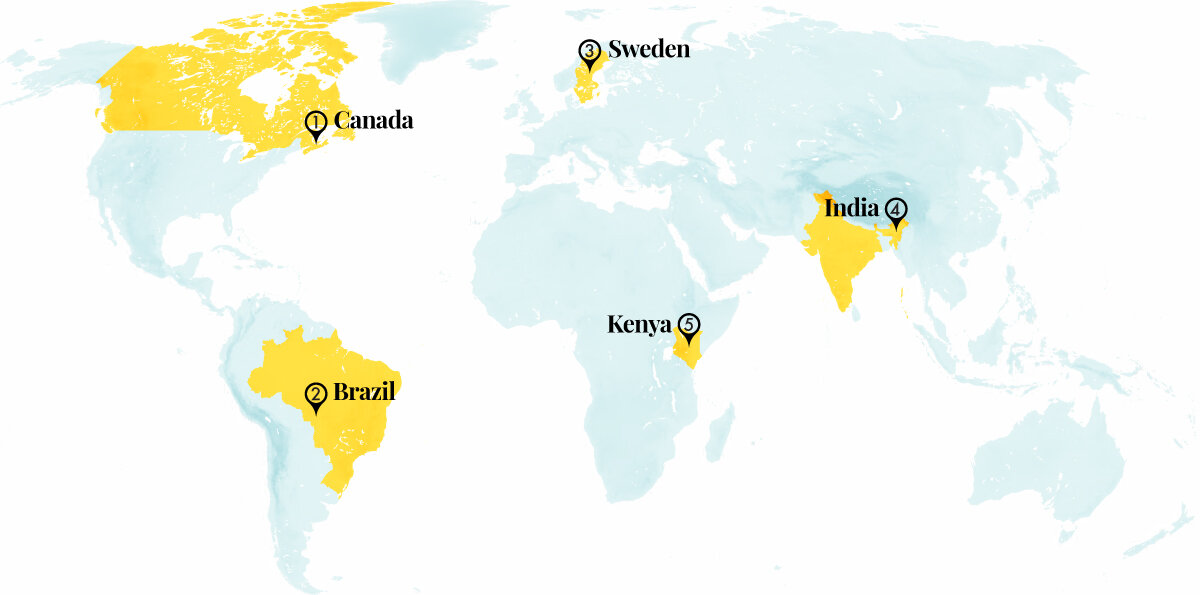

1. Canada

Scientists and Indigenous knowledge holders are teaming up to save Canada’s eelgrass by using “two-eyed seeing,” an approach that honors the insights and skills of both communities.

As eelgrass meadows struggle to cope with seabed disturbance, pollution, warming water, and invasive species, Dalhousie University researchers and the First Nations of Nova Scotia are working together in the lab and the field to study eelgrasses, keystone species of some of the ocean’s most biodiverse ecosystems.

In the waters of Maliko’mijk (Mergomish Island), sacred to the members of the Pictou Landing First Nation, volunteers and scientists transplanted eelgrass to restore vital habitat for the American eel, a cultural and nutritional staple of the Indigenous Micmac communities in Nova Scotia. Researchers are also exposing eelgrass seed to different salinity and temperature levels while examining genetic differences. Such work allows them to predict which types of grass will be most resilient to climate change, helping to guide decisions on the best strains to replant.

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and industry players are interested in the eelgrass studies for the potential impact on carbon credit markets and to increase knowledge of the meadows’ carbon storage properties.

Source: Mongabay

2. Brazil

Women are collecting seeds and building networks to help restore Brazil’s forests. The world’s most biodiverse country, Brazil seeks to reforest 31 million acres by 2030. Seed collection is crucial to reaching this goal. The country is currently without a government-led forest restoration program, and grassroots groups are finding ad hoc ways to collaborate and exchange knowledge.

In July, members of the Reseba network, founded by six Indigenous groups in the state of Rondônia, traveled to neighboring Mato Grosso to learn from Brazil’s oldest seed collectors association. The Xingu Seeds Network, which has more than 550 members, has collected seeds from some 200 species. Members discussed the importance of storing seeds free of fungi and pests, and showed how driving a car over the seeds of the jatobá-do-cerrado tree can help to break them up.

Seed collectors face various challenges, including changes in public policy that allow landowners to delay land restoration efforts. An estimated 49.4 million acres of such land are eligible, according to the Forest Code Observatory, a network of civil society groups. Its purpose is to help strengthen implementation of the Brazilian law that protects native vegetation on private land but has always been difficult to enforce.

While they await the government’s reestablished commission to oversee restoration, the collector networks are working to enhance women’s income and autonomy.

Source: Mongabay, Partnerships for Forests

3. Sweden

Scientists discovered a process for more efficient battery recycling. Lithium-ion batteries power everything from phones to electric vehicles, but the race to electrify transportation has increased the demand for the minerals necessary to make these batteries. Researchers from Chalmers University of Technology found that by using oxalic acid, the strongest of the natural plant acids, they could recover through hydrometallurgy 100% of a battery’s aluminum and 98% of its lithium, and minimize the loss of other valuable heavy metals. An estimated 256 recycled batteries or 250 tons of ore are needed to produce 1 ton of lithium.

In traditional hydrometallurgy, a battery’s metals are reduced to a black powder and dissolved in an inorganic acid. Metals are separated in a multistep process. In the new method, lithium and aluminum are removed first, reducing the waste occurring from each step. By fine-tuning temperature, concentration, and time, the researchers have found “an innovative method that can offer the recycling industry new alternatives,” said Martina Petranikova, research lead.

Source: Chalmers University of Technology, Separation and Purification Technology

4. India

Solar-powered boat clinics are bringing health care to river communities in India’s state of Assam. About 2.5 million people live on the 2,500 nonurbanized islands of the Brahmaputra River, which flows through almost the entire east-west width of the state. Since 2005, floating clinics equipped with an array of health care infrastructure have provided the isolated, flood-prone communities with free medical care. And since 2017, solar power has raised the level of care and improved working conditions for the professionals who live on the boats.

Run by a partnership between the government and the nonprofit Centre for North East Studies and Policy Research, each clinic hosts 12 to 15 patients at once, providing a range of services from prenatal care to malaria checkups. Solar power has allowed medical personnel to ditch noisy, polluting diesel generators. Round-the-clock electricity refrigerates medicines and enables fewer supply trips to the mainland. Residents say they save time and money by not having to travel for care, and the research center says 18,000 to 20,000 people use the clinics every month.

Source: Reasons to be Cheerful

5. Kenya

Scholarships for nursing students have placed skilled professionals in remote areas, bridging critical health care gaps. Over the past seven years, Kenya’s partnership with the World Bank has supported the education of 1,200 nurses from communities with low indicators of maternal and child health. Many of these students were from disadvantaged minority groups, who had felt that training was out of reach.

The government currently employs nearly 600 nurses in health care facilities with a dearth of skilled medical professionals. The initiative selects nurses native to each region to facilitate communication in the local language and ensure that services are best suited for the populations living there, which also builds trust between communities and health care professionals. The program places a special emphasis on midwifery and emergency pregnancy care, often enabling patients to remain close to home instead of be transferred to a distant hospital.

Kenya has seen an uptick in some of its health metrics in the last two decades, with mortality rates for children under age 5 falling by half. The program next seeks to expand into more communities, and calls for more investment in infrastructure and medical equipment.

Source: World Bank Blogs

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Limitless thinking in climate talks

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

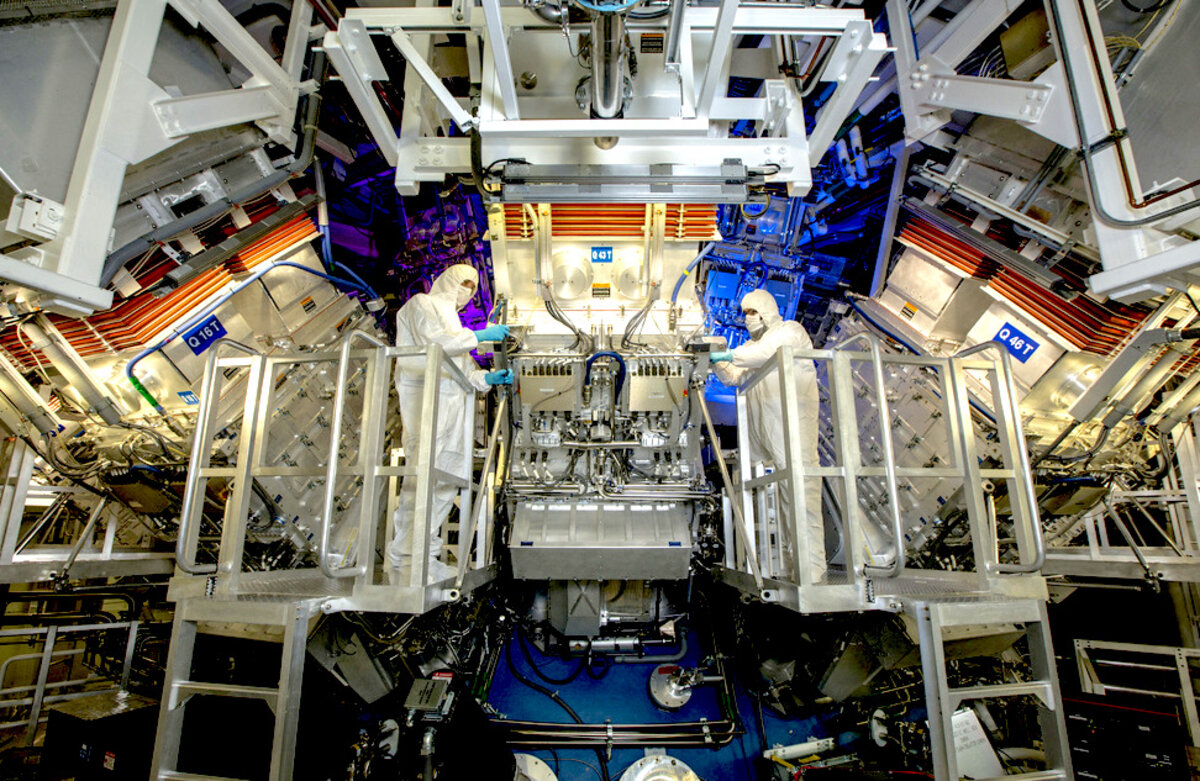

This year’s United Nations summit on climate change may see a shift in its mental climate on Tuesday. With talks stalled on reducing carbon emissions, the United States plans to deliver its main – and potentially unifying – message at the summit: a global plan to commercialize nuclear fusion as a substitute for fossil fuels.

“Fusion energy is no longer just a science experiment,” said John Kerry, U.S. special presidential envoy for climate, last month in anticipation of the announcement. Rather, after a recent scientific breakthrough in fusion research, the nascent technology that offers unlimited energy can be “an emerging climate solution,” he said.

Pooling the world’s many efforts to develop fusion might help provide a change of tone in climate talks. If other nations sign on to the U.S. plan, it would add to an agreement at the G20 meeting of major economies in September to triple their renewable energy capacity.

Such steps toward boosting energy alternatives reflect a necessity to move climate negotiations from the stalled issue of how nations can share the sacrifices needed in curbing carbon pollution. The talks need a “trajectory of progress,” writes Asif Husain-Naviatti, a visiting fellow at Columbia University.

Limitless thinking in climate talks

This year’s United Nations summit on climate change may see a shift in its mental climate on Tuesday. With talks stalled on reducing carbon emissions, the United States plans to deliver its main – and potentially unifying – message at the summit: a global plan to commercialize nuclear fusion as a substitute for fossil fuels.

“Fusion energy is no longer just a science experiment,” said John Kerry, U.S. special presidential envoy for climate, last month in anticipation of the announcement. Rather, after a recent scientific breakthrough in fusion research, the nascent technology that offers unlimited energy can be “an emerging climate solution,” he said.

Pooling the world’s many private and public efforts to develop fusion – or the harnessing of energy from pushing atoms together – might help provide a change of tone in climate talks. If other nations sign on to the U.S. plan, it would add to an agreement at the G20 meeting of major economies in September to triple their renewable energy capacity.

Such steps toward boosting energy alternatives reflect a necessity to move climate negotiations from the stalled issue of how nations can share the sacrifices needed in curbing carbon pollution. The talks need a “trajectory of progress,” writes Asif Husain-Naviatti, a visiting fellow at Columbia University, in The Conversation, based on “global collective action” and “universal values.”

“Common ground can also often be reached incrementally by building trust, confidence, comfort and eventually clarity over time,” he writes, based on his experience in negotiating agreements on sustainable development.

The U.S. has been a leader in fusion, notably with last year’s breakthrough in fusion ignition at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory. That achievement “showed that controlled fusion can be a source of clean energy for humanity,” said Dr. Scott Hsu, lead fusion coordinator at the U.S. Department of Energy. “Practical fusion energy may now be less a matter of time than of collective societal will.”

Fusion’s full promise may be years away, but in the meantime it may alter the dynamics in global climate talks. As economist Paul Romer, a winner of the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences, has noted, in the many routes to solving climate change, “we will be surprised that it wasn’t as hard as we anticipated.” Innovation in energy, he adds, requires inspiration. “We consistently fail to grasp how many ideas remain to be discovered.” The U.S. plan for the world to collaborate on commercialized fusion sets the ground for success with climate change rather than failure.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Are you moved with compassion?

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Susan Stark

As we open our hearts to God’s limitless love for all His children, we’re naturally empowered to help others in meaningful ways.

Are you moved with compassion?

Compassion moves us in a lot of different ways, perhaps especially during the holidays. People volunteer at food banks, donate toys, serve meals in shelters, or carry out other, unseen kindnesses. Acts of kindness bless the giver and the receiver and open the door to the possibility of seeing each other as the Bible indicates Christ Jesus saw people – as whole and well.

More than all else, a compassionate heart longs to heal the woes of others. The Gospel of Mark describes how Jesus responded compassionately when a man suffering from leprosy came to him. The man said, “If thou wilt, thou canst make me clean.” Then the account tells us, “Jesus, moved with compassion, put forth his hand, and touched him, and saith unto him, I will; be thou clean” (1:40, 41).

It’s fair to ask, “Does my compassion reach far enough to heal?” Compassion that depends on the ups and downs of personal goodness isn’t up to the task. The Bible, however, helps us feel the compassion that moved Jesus, by connecting it to divine Love, the source of love that never runs dry. This tells us about the unity of God, our Father-Mother, and His child, our true spiritual selfhood.

The Gospels show that Jesus saw each individual not as broken or harmed by tough human circumstances, but as beloved, cared for, valued, and embraced by God. It’s the “I will not forget you” kind of compassion, which sees no separation between Father-Mother and child, that brings the transformation of human consciousness needed to cure ills. The Savior healed through his understanding that everyone’s unique spiritual individuality is the perfect likeness of God, our creator. Then the mental chains of sin and disease dropped off from the receptive hearts who came to him for help.

We have the opportunity to practice the Christly compassion Jesus epitomized that leads to healing. We may feel that we have little to give, but we can make a start. Feeling God’s love for us makes us want to share it, just as taking the time to love others teaches us about God’s unbounded love for all. Wanting to help by letting our deepest affection for Love’s children guide us becomes the norm, not the exception, in our days. This is the work of Christ in us, the real man that reflects God’s nature as Truth, Life, and Love.

Mary Baker Eddy followed Christ Jesus closely. She experienced sorrow and want many times in her life and yearned to help anyone who was suffering. But her strength was more than a tender heart. Her inner protest against all that was unlike Love, God, led her to discover Christian Science and its power to regenerate human lives. While healing scores of people of mental, emotional, and physical illnesses, she discovered the rules for Christian compassion and healing.

Mrs. Eddy described one rule this way: “The human affections need to be changed from self to benevolence and love for God and man; changed to having but one God and loving Him supremely, and helping our brother man” (“Miscellaneous Writings 1883-1896,” p. 50).

We, too, must be moved with compassion, because mercy, kindness, justice are always at work in Love’s reflection. It can be hard not to focus on what we think needs fixing. But compassion impels us to pray to see more of the divine nature that Jesus saw in people. Compassion that rises up from meekness, patience, and spiritual intuition always helps us see possibilities for healing. These qualities are alive with love for God, and with the consciousness of achievable good that Christ, the spirit of Truth, gives us.

As we accept man’s oneness with God, we find that our daily experiences turn into a practice ground for hope, gratitude, and healing. To be safe, supplied, and well is what we want for ourselves and others. This promise is fulfilled through the compassion that moved Jesus. Christ lifts our thoughts to the reality of our spiritual sonship with God that expresses the wisdom of Mind, the vitality of Life, and the healing power of Love.

With Christ as our model, we can recognize opportunities to see healing. And with Christly compassion as our guide, we can answer the question “Am I moved with compassion?” with a heartfelt “Yes!”

Adapted from an editorial published in the November 2023 issue of The Christian Science Journal.

Viewfinder

Ruling party

A look ahead

Thank you for joining us today. We’re working on a suite of intriguing stories about the Israel-Hamas war tomorrow. We’ll examine the crackdown on freedom of expression in Israel, how the conflict is reverberating throughout the COP28 summit in the United Arab Emirates, as well as in K-12 schools in the United States. We hope you’ll come back and give them a look.