- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- US House is up for grabs – and may hinge on two blue states

- Today’s news briefs

- Putin has ruled Russia for 25 years. How did he last so long?

- Is US too late to counter Chinese clout in the Global South?

- What it’s like to be a poll worker in the US election

- Harris and Trump on family issues, from IVF to schools

- In ‘A Real Pain,’ a road trip whose emotional power sneaks up on you

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Integrity at the polls

The front-line facilitators of democracy, poll workers are trained problem-solvers. They’re strict followers of procedure, staying quiet about their own politics and keeping the line moving.

More than ever, their work calls for maintaining a sense of integrity that can shore up respect and help soothe any voter who seeks to do more than humbly engage in the electoral process. (Some poll workers receive deescalation training.)

Today, Sophie Hills and Caitlin Babcock help us understand a critical, sometimes underappreciated election-time role in the United States.

Also: Don’t miss our online guide to the U.S. presidential candidates’ policy stances. It’s highly shareable.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

US House is up for grabs – and may hinge on two blue states

With partisan gerrymandering reducing the number of competitive House districts across the U.S., some analysts see just 15 pure toss-ups, five of which are in New York and California. The top of the ticket will likely have a big impact.

California and New York are reliably Democratic – so no suspense there for Tuesday’s election, right?

Wrong. These two states may well determine control of the U.S. House of Representatives, where Republicans currently hold a whisker-thin majority. If Democrats can flip just four seats, they will retake control. And California and New York have more swing districts than anywhere else – including many GOP-held seats in districts Joe Biden won in 2020. Between them, they may well determine whether the House acts as a brake or gas pedal for the next president.

In this era of tight margins, it’s not a given that Democrats will get what they need in these blue bastions. And even if they do, the gains could be canceled out in states where Republicans are trying to flip seats, such as Pennsylvania, Michigan, Alaska, and Maine.

“The fight for the House is as close as the fight for the presidency, and I don’t think either party has a clear advantage in either one of those races,” says Nathan Gonzales, editor and publisher of the nonpartisan Inside Elections.

US House is up for grabs – and may hinge on two blue states

California and New York are reliably Democratic – so no suspense there for Tuesday’s election, right?

Wrong. These two states may well determine control of the U.S. House of Representatives, where Republicans currently hold a whisker-thin majority. If Democrats can flip just four seats, they will retake control. And California and New York have more swing districts than anywhere else – including many GOP-held seats in districts Joe Biden won in 2020. Between them, they may well determine whether the House acts as a brake or gas pedal for the next president.

In this era of tight margins, it’s not a given that Democrats will get what they need in these blue bastions. And even if they do, the gains could be canceled out in other states where Republicans are trying to flip seats, such as Pennsylvania, Michigan, Alaska, and Maine.

“The fight for the House is as close as the fight for the presidency, and I don’t think either party has a clear advantage in either one of those races,” says Nathan Gonzales, editor and publisher of the nonpartisan Inside Elections.

With partisan gerrymandering greatly reducing the number of competitive districts across the United States, Mr. Gonzales’ nationwide rankings list just 15 pure toss-ups, five of which are in New York and California. Four more seats in those states are rated as competitive, but slightly favoring either Democrats or Republicans.

The coattail effect

House races are notoriously hard to poll. And in an era of nationalized politics, the top of the ticket in a presidential year can have a huge impact. Democrats feel they got a reprieve when President Biden dropped out of the race last summer and Vice President Kamala Harris became the nominee. They’re hoping she’ll draw more voters to the polls, and that those voters will pick Democrats all the way down the ballot.

California is Ms. Harris’ home state, and she has support from 59% of voters there. That strength could be the difference in competitive districts like CA-13 in the agricultural Central Valley, where Republican Rep. John Duarte beat his Democrat opponent by a mere 564 votes in 2022. Similarly, Republican Rep. Mike Garcia eked out a win in CA-27, in northern Los Angeles County, by 333 votes in 2020.

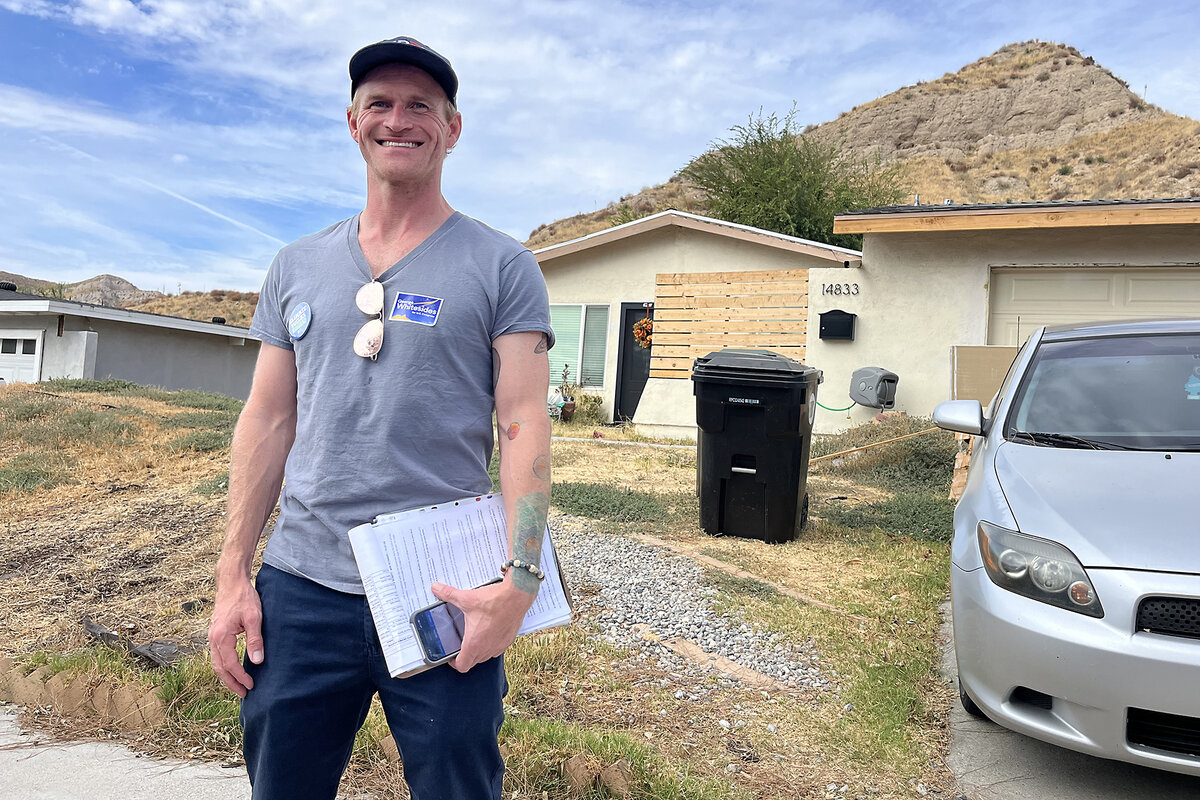

On Sunday, Mr. Garcia’s Democratic opponent, George Whitesides, rallied volunteers for a home-stretch push at a park in Santa Clarita, a northern suburb of Los Angeles. The district’s lines were redrawn after the last census, and Democrats now outnumber Republicans there. Still, “Trump trains” of pickup trucks and flags run regularly through this part of the Mojave high desert, home to a state prison and Edwards Air Force Base. The heavily Latino district has thrice elected Mr. Garcia, a decorated Navy combat pilot and former Raytheon executive.

Mr. Whitesides, who is running as a moderate Democrat, has an aerospace background as the former CEO of the Mojave-based space tourism company Virgin Galactic and a former chief of staff of NASA. His wife is Cuban and Salvadoran. He boasts of having created 700 local jobs – an important consideration for commuters to Los Angeles, who battle two-hour drives each way, high gas prices, and higher housing costs as more people move from LA to the exurbs.

The Garcia campaign is attacking Mr. Whitesides for his political donations, including to unpopular progressive LA County District Attorney George Gascón and the LGBTQ+ advocacy group Equality California. The group supported a bill equalizing sentencing for sex crimes; an attack ad accuses Mr. Whitesides of having “funded a group opposing pedophiles registering as sex offenders.”

The Whitesides campaign is hitting Mr. Garcia for his votes against the bipartisan infrastructure bill and against the bill that included a price cap on insulin for older adults, and for rejecting the electoral count for Mr. Biden in 2020. And they’ve hammered the congressman for his “no exceptions” opposition to abortion, though in a statement Mr. Garcia says he does support exceptions for rape, incest, and the life of the mother.

In an interview, Mr. Whitesides said, “Choice is obviously a huge deal” that cuts across demographic groups and parties. Even though the California Constitution protects reproductive rights, voters are worried about a national ban and concerned for women in other states, he says. With polls showing his campaign ahead by 2 points, he says he feels “cautiously positive.”

A 2022 drubbing for New York Democrats

On the other side of the country, in New York, Democrats have high hopes for retaking the seat held by Rep. Brandon Williams, a first-term Republican who represents Syracuse. In 2022, the former Navy submarine officer defeated his Democrat opponent by less than 1 percentage point, and his all-in stance for Donald Trump puts him at odds with his redrawn district, which shifted from Biden+7 to Biden+11.

Democrats are aggressively going after three more New York seats, and eyeing a “cherry on top” at the tip of Long Island, says Jacob Smith, an assistant professor of political science at Fordham University.

In the 2022 midterms, held not long after the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade, Democrats did better than expected nationwide, with an anticipated “red wave” largely failing to materialize. But in the Empire State, the party got swamped, says Professor Smith.

That drubbing in New York, however, now means Democrats have an opportunity to win back those seats. Professor Smith points to an October poll by Siena College that shows Ms. Harris leading Mr. Trump by 19 points among likely voters in the state – a big jump from September, when she led by 13 points. If the trend holds, “That sort of a rising tide lifts all boats,” he says.

On the other hand, in California, state GOP Chairwoman Jessica Millan Patterson lists lots of reasons she believes “The environment is fantastic for us.” Mr. Trump may be polling at only 33% in the state – but that’s little changed from 2020, when Republicans picked up four House seats there. Before that, they hadn’t flipped a seat from blue to red in California since 1994. They gained another in 2022.

Republican registrations overall in California have been rising, after years of decline. Ms. Patterson notes that since she took over party leadership in 2019, it has registered more than 820,000 new Republicans.

Party investments in community centers that serve Latinos and Asians in swing districts have made a “huge” difference, she says, noting that Representative Garcia gained 18 points among Latinos from 2020-2022 after the GOP created a community center in his district. The party saw a similar shift in Republican Rep. David Valadao’s Central Valley district, CA-22, where it has another Latino center. Ms. Patterson, herself Latina, says Latino voters “are the pathway back to sanity” in the state.

The independent Cook Political Report notes that Democrats are showing signs of slippage overall in California, with Ms. Harris running 6 points behind Mr. Biden’s 2020 vote share in a recent poll. And that slippage appears to be driven largely by Latinos. While Mr. Biden won that group by nearly 40 points in 2020, the vice president is currently winning them by only 20.

Republicans have an easy explanation for all of this – persistent problems with homelessness, border security, affordability, and crime. “California Democrats have destroyed the Golden State,” says Ms. Patterson, pointing to high levels of support in polls for Proposition 36, which would increase punishment for certain drug and theft crimes.

Crime is something Scott Baugh hears a lot about when he knocks on doors. The Republican former state legislator is running for the open seat vacated by Democrat Katie Porter in Orange County – where seats have flipped back and forth between parties. This district, CA-47, has been reconfigured and is rated by most election analysts as a toss-up or lean Democrat. But Mr. Baugh is ahead of his challenger, Democratic state Sen. Dave Min, by at least 3 points in some polls.

“People are uniting around the constant stories about crime,” says Mr. Baugh in an interview at a rally in Newport Beach on Saturday. Many voters here were shaken by a murder during a botched robbery outside the city’s upscale Fashion Island mall this summer, followed a month later by another robbery and shooting there. “All of our Orange County Republicans are going to get reelected. I’m going to be elected. Even Democrats know that,” says Mr. Baugh, on a morning thick with marine fog. “We will maintain the House [majority] and grow it,” he says with confidence.

With polls that lie within the margin of error, no one will know until after Election Day. Even then, it could be weeks before the outcome is clear, because of the heavy use of mail-in ballots in California and the time it takes to count them.

Today’s news briefs

• Spain flooding: Crews search for survivors as residents try to salvage what they can from ruined homes following flash floods in Spain that claimed at least 158 lives as of Thursday.

• North Korea missile test: It test-fires an intercontinental ballistic missile for the first time in almost a year, demonstrating an improved ability to potentially launch long-range nuclear attacks.

• Challenge to Musk on hold: A judge in Philadelphia places a state challenge to Elon Musk’s $1 million-a-day voter sweepstakes on hold while lawyers for the billionaire try to move the lawsuit to federal court.

• Diwali begins: In India, celebrants mark the Hindu festival of lights by symbolically lighting a record 2.51 million clay oil lamps at dusk on the banks of the Saryu River.

• Dodgers win World Series: Overcoming a 5-run deficit in the final game, the Los Angeles Dodgers win their second World Series championship in five seasons.

+ Related Monitor story: The Dodgers’ Freddie Freeman, World Series home-run hero, and the Lakers’ Bronny James, who scored his first NBA points, each also made fatherhood an LA story Wednesday night. Commentator Ken Makin explains.

Putin has ruled Russia for 25 years. How did he last so long?

The Russian public is generally satisfied with how their country has transformed under 25 years of Vladimir Putin’s rule. But that’s less because of any special attributes he has, Russian experts say, and more a reflection of history and culture.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

No one expected Vladimir Putin to last more than a few weeks when he was appointed prime minister a quarter century ago by then-President Boris Yeltsin. But last Mr. Putin did. An entire generation has grown up knowing no other leader.

Still, the reasons for Mr. Putin’s extraordinary ability to ride the Russian tiger so effectively for so long remain obscure.

He has survived a string of challenges, any of which might have wrecked him. They include a tragic disaster with the sunken submarine Kursk in his first year as president, the rupture of relations with the West, and a military mutiny that featured a march on Moscow. The war in Ukraine, which he appears to have started without consulting even his closest advisers, is still ongoing.

Throughout all this, Mr. Putin’s public approval rating has seldom dipped below 60% and is currently running around 80%.

Mr. Putin and his team “were able to overcome the difficult crises of the 1990s, with all that disorder, chaos, and banditry,” says Marina, a Moscow pensioner. “We’ve had a lot of experience with things going wrong, so obviously we cherish stability and calm. It’s hard to imagine anyone but Putin at the top of this country.”

Putin has ruled Russia for 25 years. How did he last so long?

No one expected Vladimir Putin to last more than a few weeks when he was appointed prime minister a quarter century ago by then-President Boris Yeltsin. At the time, the relatively unknown, seemingly unremarkable ex-KGB agent was simply next in line after a series of failed prime ministers selected by the fading president amid spiraling crises in Russia.

But last Mr. Putin did. An entire generation has grown up knowing no other leader. Today, having been reelected to another six-year Kremlin term earlier this year, he has never looked so firmly in control.

Still, the reasons for Mr. Putin’s extraordinary ability to ride the Russian tiger so effectively for so long remain obscure.

His supporters seldom mention any unusual qualities such as charisma, infallibility, or wisdom. They tend to point to the way Russia has transformed over 2 1/2 decades: from a dysfunctional, crime-ridden post-Soviet wreck to an orderly, relatively prosperous society where people can say they feel proud to be Russian. Most of the reforms that have remade Russia were not begun by Mr. Putin, but have reached fruition under his watch.

A good example is private ownership of land, which is now a universal right. Over the past 15 years or so, the right to sell and repurpose land has produced suburban sprawl around most Russian cities that’s reminiscent of North America in the 1950s and also, along with other factors, has led to a boom in agriculture. It may not seem impressive to Westerners, but millions of contemporary homeowners are the first Russians in a thousand years – other than a czar – who can point to a piece of land and say, “I own this” with full legal control and freedom.

“We don’t ask why Putin is popular. It just doesn’t seem like the right question,” says Alexei Mukhin, director of the independent Center for Political Information in Moscow. “We concentrate on the life around us. It seems to me that when the state and society have their own separate spheres, and don’t interfere too much with each other, life is OK. Putin seems to have found a formula that, at least so far, works.”

Better than the 1990s?

Mr. Putin has survived a string of harsh challenges, any of which might have wrecked the careers of many politicians. They include a tragic disaster with the sunken submarine Kursk in his first year as president, financial crisis, the seemingly irreparable rupture of relations with the West, and the most intense blizzard of sanctions ever leveled against a country. He has also faced a military mutiny that featured a march on Moscow, and a costly, still-ongoing war in Ukraine that he appears to have started without consulting even many of his closest advisers.

Throughout all this, Mr. Putin’s public approval rating has seldom dipped below 60% and is currently running around 80%.

“In Russian society, there is a solid base of support for the country’s leader, where about two-thirds of people express loyalty regardless of the current policy,” says Alexei Levinson, an expert with the Levada Center, an independent polling agency. “The lowest points occurred at times of economic hardship, when the population expressed its discontent,” while imperial successes, such as the 2008 war in Georgia and the 2014 annexation of Crimea, tended to boost support by up to 20%.

And while political freedoms have contracted, especially since the war in Ukraine began, the private lives of the conforming majority have remained largely untouched. For Russians over 40 years old, the cataclysmic 1990s appear to be the main reference point.

“Perhaps Putin had a good team, but they were able to overcome the difficult crises of the 1990s, with all that disorder, chaos, and banditry,” says Marina, a working Moscow pensioner. “We’ve had a lot of experience with things going wrong, so obviously we cherish stability and calm. It’s hard to imagine anyone but Putin at the top of this country.”

“Putin was the one”

Even Russian opposition figures, many of whom are in exile these days, don’t seem to agree on the sources of Mr. Putin’s political resilience.

Some point to the aura of state propaganda, in which most independent and opposition voices are banished from the official airwaves. Others say deepening repressions, especially since the Ukraine war began, have created an atmosphere of fear that makes any discussion of genuine popularity impossible. Still others stress traditional Russian political culture, and say Mr. Putin has ensconced himself as a czar who is seen by the population as above any sort of democratic accountability.

Abbas Gallyamov, a former Putin speechwriter-turned-opponent who is now living in exile, says Mr. Putin answered society’s need for a strong hand following the devastating decade of the ’90s, when society collapsed, the economy imploded, and all efforts to build democracy appeared to fail. “Putin was the one who could satisfy this demand,” he says.

At first, Mr. Putin recognized the need to integrate Russia into the wider world led by the West, he says. But since then, he’s discovered that stoking nationalism and blaming the external enemy for Russia’s troubles is a better formula.

“When the external agenda dominates, the authorities look like strong patriots, and the opposition appears to be a bunch of traitors,” Mr. Gallyamov says. “When the focus is on internal affairs, people see the authorities as corrupt, looking out only for their own interests. ... The principle that ‘Russia is surrounded by enemies’ has always worked well in the past.”

A comfortable mystery

Everyone agrees that Mr. Putin has changed over the years, reinventing his public image even as the country and its society evolved.

Recently the Minchenko Consulting group in Moscow issued an analysis that attempts to define Mr. Putin’s changing role in Russian society. Using a framing largely in line with Russian mainstream thinking, it presents him first as a “warrior” who restored order to a badly fractured country, defeating Chechen separatists and exiling delinquent oligarchs, in the early 2000s.

Then, it says, he morphed into a “caring ruler,” presiding over a surge of market-driven growth and the creation of Russia’s first-ever working consumer economy. In his latest incarnation, Mr. Putin is presented more as a global “creator,” or a leader who drives the establishment of a new world order with an entirely new role for Russia.

And the state-funded RT global TV network recently released a tool that divides Mr. Putin’s 25 years into three distinct periods, and uses artificial intelligence to convert key speeches from each into clear, spoken English.

“It just remains a mystery, but one that most Russians seem comfortable with,” says Mr. Mukhin. “When Putin came to power, things started to work. People are afraid of him, yes, but it’s hard to imagine an alternative. He exercises a kind of alchemy, maybe, but very many people see him as a genuine leader.”

Patterns

Is US too late to counter Chinese clout in the Global South?

China and Russia have so far set the pace in building economic and political ties with Global South nations. Can Western governments match their appeal? That’s their goal.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

Beyond the hot wars in Ukraine and the Middle East that the next U.S. president will have to deal with, there is a major soft-power challenge.

It is the tussle for influence in the Global South – the broad collection of countries not aligned with any great power. And in trying to persuade these nations that they have common interests with the West, Washington will be going up against Russia and China.

Moscow sees the BRICS group, led by Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa, as a way of demonstrating the West’s shrinking influence. Beijing has taken the lead so far on economic relations with the Global South, offering huge loans for infrastructure projects on every continent.

But the West is pushing back. As BRICS met in Russia, the International Monetary Fund announced that it would slash charges on its loans by more than 30%, and expand its lending program. It named an additional executive board member, from sub-Saharan Africa.

And the G7 leading industrial nations met in Italy to discuss ways of supporting infrastructure projects in developing nations. The battle for influence has been joined.

Is US too late to counter Chinese clout in the Global South?

Even as the clock ticks down to an election that will decide U.S. policy on hot wars in Ukraine and the Middle East, it’s becoming increasingly clear that a major “soft power” challenge also awaits whoever wins the White House.

The battlefield will be what many call the Global South, the broad collection of nations that are not formally aligned with any of the great powers. The challenge will be to convince such nations that they share interests – and can find common ground – with the West. That will pit Washington and its allies against Russia and China.

And in the past week, three dramatically different economic meetings have underscored the growing importance that both sides attach to its outcome.

The gatherings also provided a snapshot of where the contest currently stands: America’s rivals, above all China, have been making much greater economic and political advances with the countries of the Global South.

But Washington and the West are pushing back.

The most high-profile meeting took place in the Russian city of Kazan.

Hosted by President Vladimir Putin, it brought together the BRICS countries, named for the five core members of the 8-year-old group – Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa.

China and Russia see the now-expanding partnership as a way of demonstrating – and, they hope, accelerating – what they see as the West’s shrinking influence.

For Mr. Putin, the key context is Ukraine. He framed the summit, at which he hosted 36 world leaders, as proof that Washington and its allies had failed to isolate him internationally since he invaded Ukraine.

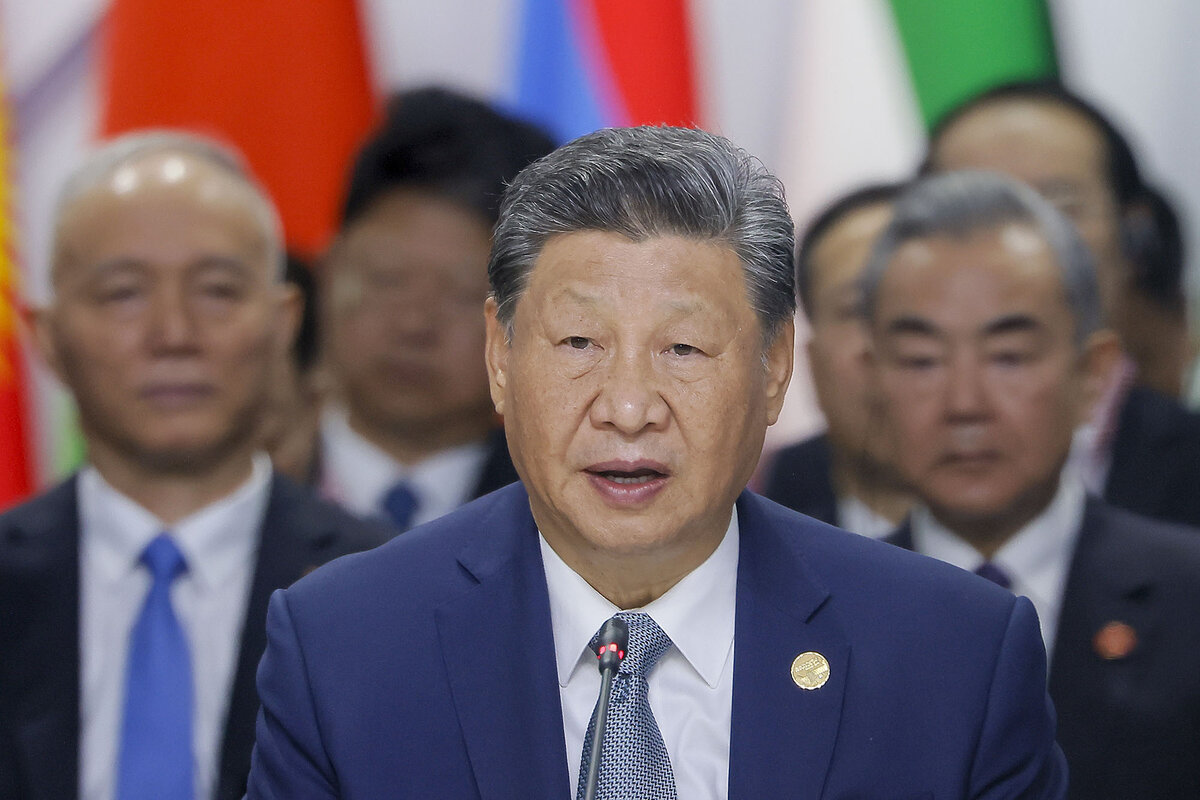

For Chinese leader Xi Jinping, it is one of two prongs in a more ambitious project: positioning his country to rival, and ultimately surpass, America’s power and sway in the world.

The first prong is BRICS, and China’s membership in it. The other prong is a $1 trillion loan and investment program called Belt and Road, through which China has been rolling out major infrastructure projects across the Global South.

Among the attractions for beneficiaries has been that China’s help comes without the kind of economic and political conditions that U.S. and Western donors have long emphasized: economic sustainability, transparency, and a broad acceptance of democratic norms.

That’s where the past week’s other, lower-key economic meetings come in.

They provided a window into how the United States and its allies are seeking to match the appeal of the Belt and Road and BRICS with initiatives of their own.

In Washington, the twin pillars of the international economic system built by America and Europe after World War II – the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund – held their annual meetings.

The IMF clearly had the Belt and Road in mind – especially the huge debt burden some Chinese infrastructure deals have imposed – when it announced significant changes to its lending terms.

The IMF said it was slashing “charges and surcharges” on its loans by more than 30%, potentially saving borrowers $1.2 billion, and that it would also expand its own lending capacity.

On the political front, it announced that its executive board would add a member: from sub-Saharan Africa.

The Western response was even clearer at a meeting of the G7 group of major world economies in Pescara, on the eastern coast of Italy, the group’s current chair.

The discussion focused on infrastructure projects for developing nations in the Global South. The plans are part of the Partnership for Global Infrastructure and Investment, an idea first proposed by U.S. President Joe Biden in 2021 with the aim of providing a total of $600 billion in public and private-sector investment by 2027.

That’s proving to be a very hard lift. Only $30 billion, 5% of the target, has been raised so far, with the single largest project a major cross-African rail link known as the Lobito Corridor.

But the overall approach is deliberately different from the Belt and Road: ensuring the projects do not lead recipient countries into debt traps and addressing a broad range of development priorities including digital infrastructure, health provision, and climate resilience.

The hope is that this kind of partnership, over time, will prove more attractive.

But another challenge, this one political, may raise its head.

Not only are Chinese and Russian “values free” partnerships enticing for many leaders in the Global South. But Washington’s approach to world affairs in recent years, not least in the Middle East, has fed disillusion with American leadership among those countries.

Still, a number of Global South nations, including key BRICS members India and Brazil, have been equally reluctant to draw too close to Beijing or Moscow. They do not want to make BRICS an explicitly anti-Western alliance.

A recent worldwide survey by the Pew Research Institute may also encourage Western hopes that institutions like the IMF could yet find fertile ground for their new initiatives.

The survey did find falling confidence that President Biden would “do the right thing” in world affairs: only 43% agreed with that.

But the corresponding figure for Mr. Xi was 24%.

And for Mr. Putin, just 21%.

What it’s like to be a poll worker in the US election

Election workers play a key role in running voting operations on Election Day. Their role has come under increased scrutiny since the 2020 U.S. elections. Here’s what this position involves – and how people are handling the pressure.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

-

Sophie Hills Staff writer

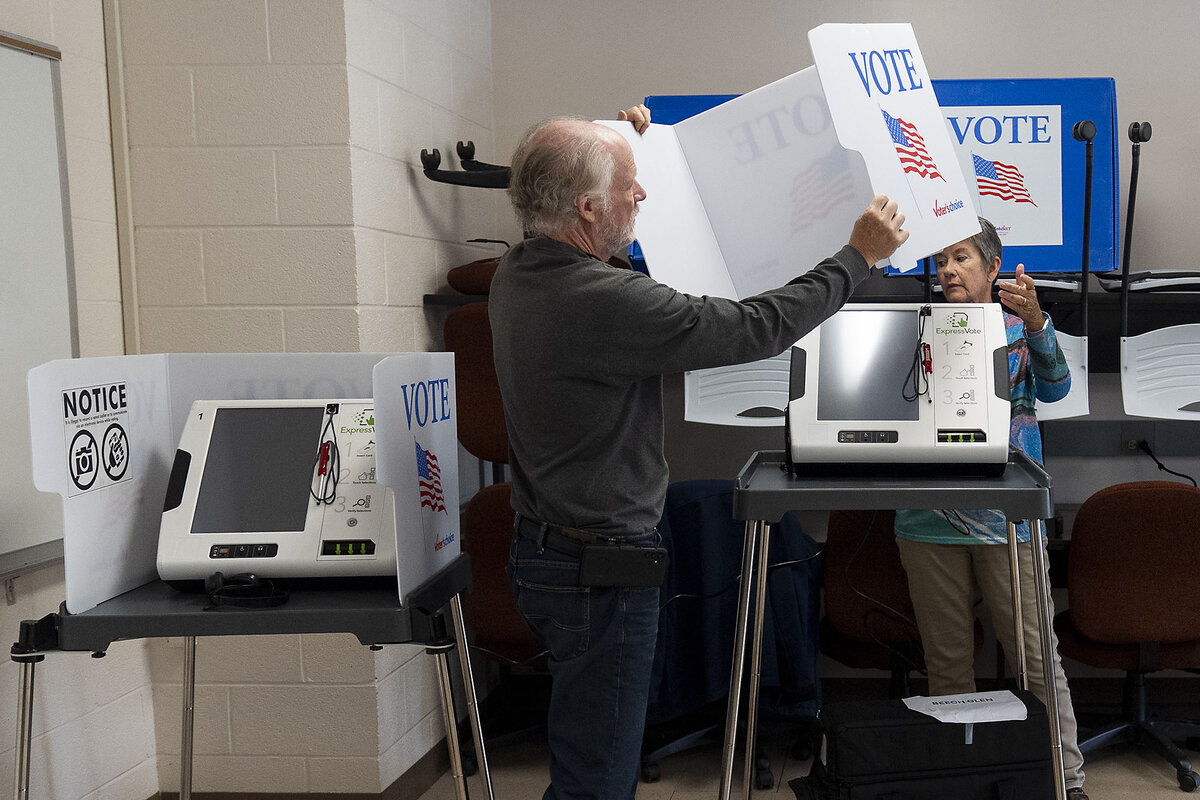

When voters head to the polls next week, the millions of ballots cast will be processed by at least 700,000 election workers across the United States. Most of those involved are either volunteers or temporary staff who are paid modestly to set up equipment, verify voter registration and identification, and count ballots.

Threats aimed at election workers spiked in 2020 and have remained high since. In response, election officials around the country from both major political parties have worked to educate voters about how elections work, saying the more people understand the process, the more they trust the results.

Election workers are unaffiliated with political parties. Often, they serve in the community where they live. Poll workers are different from poll watchers, who volunteer – typically with a party or partisan group – to observe how elections are carried out. Almost all states require training for at least some poll workers.

“I think that given the temperature of these past elections, I have been concerned,” says Melissa Harris, a poll worker from Georgia. But the importance of her work outweighs those worries. “In order to have an active role and a democracy that we care about, everyone should consider, How can they get out and do something?”

What it’s like to be a poll worker in the US election

When voters head to the polls next week, the millions of ballots cast will be processed by at least 700,000 election workers across the United States. Most of those involved are either volunteers or temporary staff who are paid modestly, some as little as $5 per day, to set up equipment, verify voter registration and identification, and count ballots.

Amid misinformation about election integrity, threats aimed at election workers spiked in 2020 and have remained high since. In response, election officials around the country from both major parties have worked to educate voters about how elections work, saying the more people understand the process, the more they trust the results.

The specifics of poll workers’ jobs vary by locality since most election administration is conducted at the county level. But generally speaking, these positions around the country follow a similar model.

You don’t work for political parties

Election workers are unaffiliated with political parties. Often, they serve in the community where they live. Poll workers are different from poll watchers who volunteer – typically with a party or partisan group – to observe how elections are carried out.

Most states require poll workers to be a U.S. citizen, above 18, and without a criminal background that would prevent them from voting.

Poll workers aren’t typically allowed to discuss politics while they’re on the job, or even wear clothing that expresses political opinions. “Up until 6 a.m. on Election Day, you can have your opinions,” an instructor told a room of about 40 poll workers during a training this month in Media, Pennsylvania, a small town outside of Philadelphia.

Ishea Jennings, an attendee at the training, signed up to be a poll worker two years ago in part because she didn’t see many other minorities who were doing that work.

She was the the only millennial working at her polling place in the 2022 midterm elections, but for Pennsylvania's 2024 primaries, she was impressed to see high schoolers who weren’t old enough to vote spending their day working at the polling place.

“I always thought that these were, like, state government employees that were doing this,” Ms. Jennings says, “so just knowing that these are average people that are running it is really cool.”

You complete hours of training

Almost all states require training for at least some poll workers. In the states that don’t, some counties develop their own training course.

In Media, Pennsylvania, that training consists of three hours on a Monday evening in a county government office, where poll workers are walked through how to use the equipment and learn what they’ll be responsible for in the polling place. They're also given a 100-page election guide that walks them through a slew of scenarios they might have to deal with on Election Day. It includes numbers to call for support, from a poll worker’s hotline if there’s a technology failure, to the District Attorney’s office if someone tries to block voters from entering the polling place.

It’s similar in Montgomery County, Maryland. Eamon Vahidi, who’s worked elections in California and then Maryland since 2016, went through an online training and quiz, followed by a three-hour, in-person training in order to work the polls this year.

In Maricopa County, Arizona, the poll worker training manual includes instructions on how to reach a hotline in situations such as voter wait times surpassing 30 minutes or power outages at the polling facility.

You have to think on your feet

Handling equipment and checking voters in is only part of a poll worker’s job. They’re also tasked with making sure voters can exercise their right to vote without interference.

That means being observant. If a voter might need assistance to fill out a ballot, it’s their job to notice that. If poll watchers are getting in voters’ way, they’ll need to step in.

Often, in the polling place where Mr. Vahidi works, voters don’t realize they are not allowed to have cellphones out, he says. At his site, one worker is assigned to the door to watch for phones and offer voters pencil and paper to copy down their voting plan, which many bring on their phone.

When Ms. Jennings worked the polls in Pennsylvania for the first time, she made an emergency trip to the Dollar Tree. Her precinct served a lot of senior citizens, and she and her co-workers realized that some were struggling to read their ballots. They bought extra eyeglasses, which they handed out to voters who needed them.

Melissa Harris, a Georgian who will be working the polls in her third election next week, often has to help voters who come to the wrong precinct.

You’re not a poll watcher

Poll workers facilitate elections. Poll watchers observe them. And, unlike poll workers, poll watchers are often recruited by a party or partisan organization. They’re dispatched to polling places and election headquarters, where they observe the casting and counting of ballots, flag any suspected irregularities they see, and often provide on-the-ground reports about turnout to their party.

As with election workers, the rules governing poll watchers vary by state. In most cases, they’re not supposed to interfere in any way or speak with voters in the polling place. Often, they have to stand a certain distance away from voting machines.

Wenda Kincaid, an election judge in Berks County, Pennsylvania, has noticed a big uptick in the number of poll watchers. More often than not, she says, the issues she encounters on election day are not from the general public, but from poll watchers “who aren’t trained, or aren’t following the training they’re supposed to have.”

Your job is harder this time

Threats to poll workers’ safety spiked following Mr. Trump’s unfounded claims that the 2020 election was stolen. In a May 2024 report, over a third of local officials reported experiencing threats or harassment, according to the Brennan Center for Justice. Seventy percent of local election officials reported feeling as if threats have increased since 2020, and 92% of election administrators have taken steps to increase security for election workers and voters.

“I think that given the temperature of these past elections, I have been concerned,” says Ms. Harris, the poll worker from Georgia. But the importance of her work outweighs those worries. “I just think that in order to have an active role and a democracy that we care about, everyone should consider, how can they get out and do something?”

There are indications that most of the public still trusts their local election workers. Among supporters of Vice President Kamala Harris, 97% believe poll workers in their community will do a good job, as do 84% of former President Donald Trump’s supporters, according to a recent Pew Research Center survey.

In her community, election workers are generally anxious – mostly because of the national temperature, says Ms. Kincaid, the election judge. She doesn’t expect tempers to run high in her rural county, though. “The people who are voting are our friends, our neighbors, our family. These are people we’re going to see at the grocery store.”

Harris and Trump on family issues, from IVF to schools

The Harris and Trump tickets project diverse family portraits that, collectively, represent the United States today. They all share family as a top priority, but their policy approaches diverge sharply.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

While polls show top voter concerns are about the economy and democracy itself, family issues offer a robust catchall for how voters feel about the state of America – and offer the presidential candidates a way to share their visions for the nation. Safety, education, financial security, gender roles, and even immigration all funnel into a family framework.

Candidate family portraits, on full display, are snapshots of modern America.

Former President Donald Trump, a wealthy businessman, has five children from three marriages, two of which were to immigrants. His running mate, Ohio Sen. JD Vance, who grew up on the margins of poverty, has three children from his biracial marriage.

Vice President Kamala Harris, daughter of immigrants, has helped raise two stepchildren in her multiracial marriage. Her running mate, Minnesota Gov. Tim Walz, and his wife relied on fertility treatments to have two children, one diagnosed with a learning disorder.

These portraits project distinct undertones, says sociologist Richard Petts. “The conservative approach is, ‘The government is not going to help, or it’s not our job. Small government, low spending, no public policies. ... We need to go back to the glory days.’ And the more liberal side is, ‘We need to spend tax dollars and provide social supports to people who need it.’”

Harris and Trump on family issues, from IVF to schools

Family is front and center in the U.S. presidential campaign: Safety, education, financial security, gender roles, and even immigration all funnel into a family framework.

While voters say their top concern is the economy, family life offers a robust catchall for how voters feel about the state of the country – and offers the campaigns a way to share their visions for America.

Just about any issue can be presented as a family issue, says University of Dayton political science professor Christopher Devine. “Whether it connects is different, and maybe a candidate’s success at doing that could relate to his or her ability to speak about their relationships within their own family.”

The candidates’ family portraits, which they’ve put on full display, are snapshots of modern America.

Former President Donald Trump, a wealthy businessman, has five children from three marriages. His spouse and one of his former wives are immigrants. His running mate, JD Vance, who went from the margins of poverty in small-town Ohio to the U.S. Senate with a combination of grit and his grandmother’s determination, has three children from his biracial marriage.

Vice President Kamala Harris is a daughter of immigrants – a scholar and a scientist – and has helped raise two stepchildren in her multiracial marriage. Her running mate, Tim Walz, and his wife of 30 years relied on fertility treatments to have their two children, one of whom is diagnosed with a learning disorder.

These portraits have distinct undertones, says sociologist Richard Petts. “The conservative approach is, ‘The government is not going to help, or it’s not our job. Small government, low spending, no public policies. ... We need to go back to the glory days.’ And the more liberal side is, ‘We need to spend tax dollars and provide social supports to people who need it.’”

Bipartisan support for better schools and child tax credits

The campaigns agree on certain aspirations: supporting working families with things like the Child Tax Credit and paid family leave; creating safe communities; and helping families who want them to have more children. Both acknowledge a need for families to feel economically stable, for students to attend well-resourced schools.

The Child Tax Credit has shaped up to be a central talking point with strong bipartisan support – but the candidates’ approaches have stark differences.

Mr. Trump’s platform calls for permanent implementation of his own Tax Cut and Jobs Acts, which Congress passed in 2017 and expires next year. That doubled the maximum Child Tax Credit from $1,000 to $2,000, raised income thresholds for reducing the tax credit, and allowed for a portion of it to be refunded to families whose tax bills came in under the credit. It also added smaller tax credits for older teens living at home and full-time college students, and for older dependent parents.

Critics say that this version of the credit helps higher-earning parents who don’t need it – and that qualifications exclude the poorest parents, who need it desperately.

For his part, Senator Vance has said he’d like to see a large bump – from $2,000 per child to $5,000 – with no income thresholds.

Ms. Harris’ proposal would raise the tax credit based on a child’s age: to $6,000 for newborns, $3,600 for children under 6 years old, and $3,000 per child ages 6 to 17. And it could be in the form of a refund, which benefits families with the lowest incomes. But it is expensive, by one estimate costing $1.6 trillion over 10 years.

Tax credits can be helpful, say experts – but they’re not a replacement for other supports.

Paid family leave support for working parents

Policies around working parents and family caretakers illustrate the candidates’ divergent family portraits.

Mr. Vance’s controversial remarks about leaning on grandparents to care for children and his comments about the “civilizational crisis” of low birth rates vis-à-vis “childless cat ladies” show the broad differences between the tickets on family issues. The Republican emphasis is on married, heterosexual, two-parent households with children – versus all types of families for the Democrats.

“The cat lady comment was really articulating a sort of traditional – and offensive to many people – view of family life,” says Joel Goldstein, a vice presidential scholar at St. Louis University. “It provoked a lot of discussion and pushback.”

Despite polarization on family matters, “Americans have generally been moving toward an idea that people should have the right to divorce, should have the right to make decisions about working,” says sociologist Stephanie Coontz, director of research and public education at the Council on Contemporary Families. Surveys from the 1970s and 1980s show people thought working mothers could not be good parents, she adds. “That has just been transformed.”

As of last year, nearly 33 million families had children under 18 at home. Among those with married parents, more than two-thirds have both parents working. Those percentages go up for single parents – 89% of unmarried fathers work, as do 77% of unmarried mothers.

Nearly 86% of American voters in a Morning Consult survey say the U.S. economy would be stronger with federal policies that make it easier to work and care for loved ones. And both candidates have plans for that.

During his presidency, Mr. Trump implemented paid family leave for federal workers – up to 12 weeks to care for a newborn or close relative, and his current platform proposes tax credits for unpaid family members who care for loved ones full time.

Paid family leave is a priority for the Harris-Walz team. Ms. Harris has said she wants to expand the federal program to all workers, and as governor, Mr. Walz implemented 20 weeks of partially paid family leave in Minnesota.

As the cost of child care increases, Ms. Harris suggests no family should pay more than 7% of their income for it – an idea that was included with President Joe Biden’s unsuccessful Build Back Better plan in 2021.

On education, which is largely controlled at the local level, candidate Mr. Trump emphasizes parental rights and school choice – meaning that parents should be able to influence educational curriculums, determine their children’s in-school gender identity, and redirect tax funds to subsidize private schooling. He has also proposed eliminating the Department of Education.

Ms. Harris, who is backed by several unions representing educators, has said she will fight attempts to pull public funding from public schools. Her choice of Mr. Walz, who has deep roots in Minnesota’s public school system, where he met his wife who was also a teacher, implicitly speaks to her belief in that system. And Minnesota’s policies to help students – like universal free lunch – align with her vision of offering broad government supports.

A modern view of fatherhood

At one moment during their debate, Governor Walz and Senator Vance connected over gun violence: When Mr. Walz said his son had witnessed a shooting, Mr. Vance offered an audible show of empathy. From there they diverged, with Mr. Vance calling for greater security measures and attention to mental health and Mr. Walz pitching stronger limits on the types of guns on the legal market.

Families on the campaign trail are nothing new. Candidates have long stood alongside their spouses and children to launch their campaigns, and at stops along the way to Election Day. But the way Mr. Vance and Mr. Walz talk about fatherhood is particularly modern, says Professor Petts, who specializes in the role of fathers.

“It’s much more accepting for fathers to be seen as loving and caring and involved and not just this passive secondary parent,” he says, talking about progress in the way society views fathers. They’re now expected “to be not only involved and connected, but to be emotionally involved in their family life.”

In ‘A Real Pain,’ a road trip whose emotional power sneaks up on you

“A Real Pain,” written by, directed by, and co-starring Jesse Eisenberg, is the kind of movie that creeps up on you, says Monitor film critic Peter Rainer. It has a way of seeing that, in its own modest way, owes something to the Yiddish sensibility that informed storytellers like Isaac Bashevis Singer.

In ‘A Real Pain,’ a road trip whose emotional power sneaks up on you

“A Real Pain,” written by, directed by, and co-starring Jesse Eisenberg, is the kind of movie that creeps up on you. When I first saw it, I found it smart and engaging but also a tad tenuous. A road movie about two New York cousins who embark on a Holocaust history tour in Poland, it feels shaggy and discursive at the outset. But all that looseness is a decoy. A lot of emotional weight is packed into this seriocomic ramble if you know where to look.

David (Eisenberg) and his cousin Benji (Kieran Culkin) were close as kids but haven’t seen each other in years. The death of their beloved grandmother, a Holocaust survivor, prompts a reunion. Their plan is to fly to Warsaw and eventually split off from the tour to visit their grandmother’s childhood home.

It’s clear from the start that these two are a classic odd couple. David, a husband and father, holds down an unexciting but lucrative tech job. As is true of most of the characters Eisenberg has played in the movies, he’s sharp and tightly wound, and speaks in staccato sentences. Benji, by contrast, is a gregarious oversharer with no real job. His spiritedness is unsettling because it also carries an edge of hysteria.

Both men, in their own way, are visibly distressed. David mostly keeps his discontents locked inside; Benji holds nothing back. He prides himself on being a truth-teller. He loves David but thinks he’s “kind of a lightweight.” He says he misses the kid “who used to cry all the time.” David has a great residual affection for Benji, but what he finds exasperating is that this truth-teller can’t really confront the troubling truths about himself.

As a writer-director, Eisenberg is attuned to register the absurd in even the direst situations. It’s a way of seeing that, in its own modest way, perhaps owes something to the Yiddish sensibility that also informed storytellers like Bernard Malamud and Isaac Bashevis Singer. “A Real Pain,” despite its dark undercurrents, is often very funny.

The tour is headed by James (Will Sharpe), a young, Oxford-educated Brit who, despite not being Jewish, prides himself on his knowledge of Polish Holocaust lore. The group also includes a recently divorced woman, Marcia (Jennifer Grey), and Eloge (Kurt Egyiawan), a Canadian resident who escaped the Rwandan genocide and has converted to Judaism. Among many other stops along the way, they visit the Warsaw Ghetto, posing before its monument, and, near the town of Lublin, the Majdanek concentration camp.

In between jaunts, they stay in deluxe hotels and ride in first-class train compartments. The juxtaposition between such comforts and the horrendous history underscoring the trip spins Benji around. He refuses to travel in style and tries, without much success, to make everyone else feel guilty. His carryings-on are not misplaced exactly, but there’s an air of one-upmanship at work, too. He wants everybody to know that he feels more than they do. David finds himself apologizing to the group for Benji’s outbursts, but we can see that, on some level, he wishes he could be as unfettered.

What’s distinctive about “A Real Pain,” which I was slow to grasp, is that none of these scenes is intended to be cathartic, including the moment when the cousins finally encounter their grandmother’s house. This film is saying that you can’t will catharsis. It happens when it happens. Or it doesn’t. This seems to me a more honest view of experience than what we are accustomed to seeing in the movies.

Eisenberg, whose family fled Poland in 1938, drew on his personal experiences for this film. As an actor, he does well by David, though the performance is not much of a stretch for him. Culkin is rightly the film’s star. He makes Benji’s obnoxiousness both deplorable and deeply touching. Benji revels in his own suffering and, for companionship if nothing else, wants others to suffer alongside him. He’s a wayfarer who embarks on this trip because, without fully realizing it, he is yearning for a foundation. He may be a real pain, but he’s also in real pain. The movie doesn’t diminish his woe.

Peter Rainer is the Monitor’s film critic. “A Real Pain” is rated R for language throughout and some drug use.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

The light in Cuba

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

In Cuba, blackouts may be bringing light. The island’s power grid has collapsed at least four times in October, plunging the country into darkness. Even under the best conditions, electricity reaches only parts of the population for a few hours at a time.

President Miguel Díaz-Canel declared a state of emergency and blamed the crisis on Washington’s long-standing economic embargo. But even his most senior aides no longer trust that old excuse to placate frustrated citizens.

On Tuesday, the ruling Communist Party fired the vice prime minister in an anti-corruption probe into private business. Several days earlier, Vice President Manuel Marrero Cruz openly contradicted his boss, ascribing the outages – a “complex” situation, he called it – primarily to dilapidated energy infrastructure.

Such rays of transparency may seem at odds with a government hobbled by corruption and criticized for jailing its opponents. Yet that reputation obscures gradual reforms to meet the rising demands of a new and entrepreneurial generation, such as legalization of privately owned businesses.

“With the new circumstances, more honesty has found its way into all areas of the economic debate,” notes Marcel Kunzmann, a Cuba expert at the University of Buckingham. The expectations of ordinary citizens have shifted. Some officials might now be listening.

The light in Cuba

In Cuba, blackouts may be bringing light. The island’s power grid has collapsed at least four times in October, plunging the country into darkness. Even under the best conditions, electricity reaches only parts of the population for a few hours at a time.

President Miguel Díaz-Canel declared a state of emergency and blamed the crisis on Washington’s long-standing economic embargo. But even his most senior aides no longer trust that old excuse to placate frustrated citizens.

On Tuesday, the ruling Communist Party fired the vice prime minister in an anti-corruption probe into private business. Several days earlier, Vice President Manuel Marrero Cruz openly contradicted his boss, ascribing the outages – a “complex” situation, he called it – primarily to dilapidated energy infrastructure.

Such rays of transparency may seem at odds with a government hobbled by corruption and criticized for jailing its opponents. Yet that reputation obscures gradual reforms to meet the rising demands of a new and entrepreneurial generation, such as legalization of privately owned businesses.

“With the new circumstances, more honesty has found its way into all areas of the economic debate,” wrote Marcel Kunzmann, a Cuba expert at the University of Buckingham, in a paper published in May. Although most workers still work for the state, he noted, the expectations of ordinary citizens have shifted. “If anything can be said about the young generation in Cuba, it is that we are workers,” a young woman told him.

Honesty has lately helped another country confront its own persistent energy crisis. Since roughly 2007, South Africans have endured rolling brownouts to cope with rising demand on an aging, publicly owned power grid never designed to meet the needs of the full population. Efforts to overhaul the system were beset by deepening corruption. Last year, President Cyril Ramaphosa was forced to declare the power cuts a national emergency.

But the formation of a new coalition government following elections in May that ended three decades of one-party rule has already brought change. A new law signed in August maps an end to the state’s monopoly on power generation. Democratizing the grid, Mr. Ramaphosa said, will boost competition and a shift toward renewable energy sources.

Oil fuels 80% of Cuba’s energy production. In March, during a previous round of acute power shortages, only one of the country’s three refineries was functional. Protests broke out in several cities over “freedom, food, and electricity.” Nearly 5% of the population has emigrated since 2021.

The government’s attempt “year after year to explain the situation and affirm that ‘they are working to resolve it’ are not well received by a large part of the population, tired and worn out by the difficulty of sustaining life in Cuba with a minimum of well-being,” the news blog La Joven Cuba observed.

Some officials might now be listening. Out of the darkness, their honesty shines new light.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Finding the real cause

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 4 Min. )

-

By Susan Stark

Seeing God, or good, as the one true cause of everything that really exists brings healing.

Finding the real cause

In everyday life we might not think much about cause-and-effect relationships until we encounter something we don’t like, such as pain or sickness. Then we try to figure out what’s making us suffer.

What if our belief that we need to find a material cause for sickness is wrong? Wouldn’t it be a great relief to know that there’s a better way to think about cause and effect?

The words and works of many people in the Bible point in a spiritual direction. They searched for a primary cause for all things and found God to be that cause, the universal divine intelligence, as proclaimed in statements such as, “Thou art great, and doest wondrous things: thou art God alone” (Psalms 86:10).

Among the wondrous things God, Spirit, has created is the real, spiritual nature of each of us as the effect, or likeness, of Spirit. Grasping this true identification of ourselves as wholly spiritual frees us to express health and harmony, what Christ Jesus called the “works of God” (John 9:3).

Jesus faced questions like those we might pose about the source of disease. His students once asked why a man had been born blind and suggested it might be because either the man or his parents had sinned (see John 9:1-7). He said, “Neither hath this man sinned, nor his parents: but that the works of God should be made manifest in him.” Then he healed the man.

In seeking both the cause and the cure of disease, Mary Baker Eddy discovered Christian Science, the Science or spiritual understanding she discerned in Jesus’ teaching and healing. She uncovered the fact that the flesh and its ills are actually mental – are, in fact, illusions.

Much of her book “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures” is devoted to disproving the reasoning that starts with matter as a cause, including accepting that it has produced some bad effect. Instead, Christian Science shows the belief that another power besides God, good, exists to be a mistake.

Only Spirit, God, has the power to cause anything real because God is All. Science and Health describes how to heal with this higher understanding: “It breaks the dream of disease to understand that sickness is formed by the human mind, not by matter nor by the divine Mind” (p. 396).

Once when I had an upset stomach, I saw how the belief that matter is a cause can be replaced with the knowledge that the power of God alone is causative. Although I thought briefly about what might be the physical root of the trouble, there’s an insight in Science and Health that is helpful in this kind of situation: “You say that indigestion, fatigue, sleeplessness, cause distressed stomachs and aching heads. Then you consult your brain in order to remember what has hurt you, when your remedy lies in forgetting the whole thing; for matter has no sensation of its own, and the human mind is all that can produce pain” (pp. 165-166).

I put aside the reasoning that a physical cause was producing the stomach trouble. In prayer, I turned from the pain to God, the First Cause, who produces only good, and the upset stopped.

We experience this “forgetting” that heals through listening for Christ, God’s message of Truth and Love, coming to our receptive hearts to take away our fears and break the mistaken association between material cause and effect. Christ spiritually guides our reasoning from “Why is this bad thing happening?” to faith in God as the creator of good, not evil. Loving God and accepting the divine Mind as our real Mind brings to light health as normal and disease as abnormal.

Long-term illnesses are healed in the same way. For example, Science and Health tells of a woman being healed of consumption – a leading cause of death in the United States in the early 20th century. The woman thought that wind from the east made it difficult for her to breathe. After Mrs. Eddy prayed for her, the woman’s breath came easily.

Mrs. Eddy describes what happened to bring about the healing: “My metaphysical treatment changed the action of her belief on the lungs, and she never suffered again from east winds, but was restored to health” (p. 185).

We don’t have to keep asking “What’s causing this sickness?” The belief that we have to suffer from material causes can increasingly fade from our lives. This happens as we gain in our understanding of Mind, God, as the supreme cause that originates all true action and effects only good.

Adapted from an editorial published in the Aug. 19, 2024, issue of the Christian Science Sentinel.

Viewfinder

I choose the treat

A look ahead

Thanks for joining us today. Come back tomorrow. We’ll have a podcast conversation with Peter Ford, our international news editor, about our recent series of stories on Sudan.