Why is NASA sending a penny to Mars?

Loading...

A penny in today's economy does not go very far, but that has not stopped NASA from making a 1-cent piece stretch all the way to another planet: Mars.

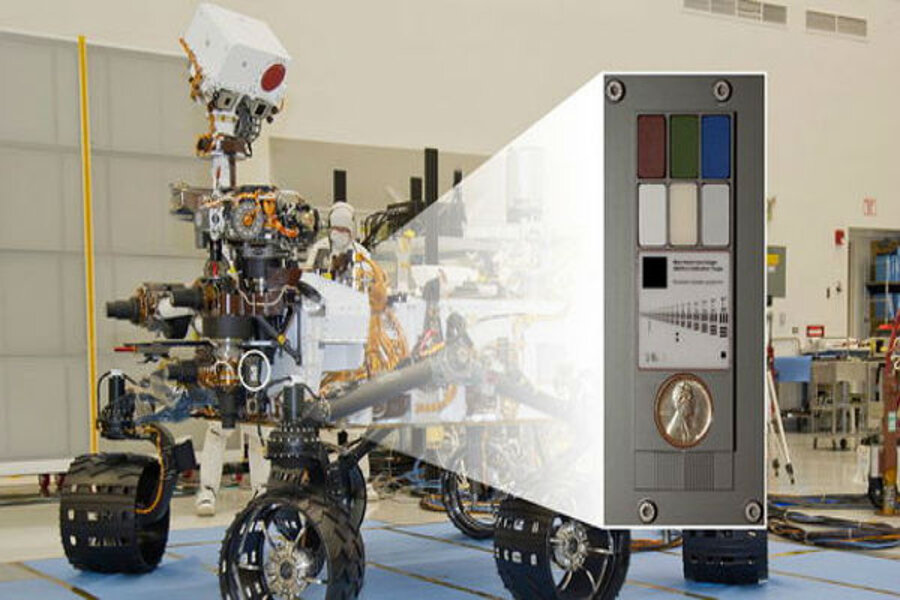

The copper coin is attached to a smartphone-size plaque at the end of the robotic arm on Curiosity, NASA's Mars Science Laboratory car-size rover. The plaque, which was added to the vehicle as a calibration target, looks like an eye chart supplemented with color chips and the attached penny.

NASA launched the Curiosity rover last November and it is scheduled to touch down on Mars in August.

Targeted for a landing inside the Red Planet's Gale Crater, Curiosity will then begin its two-year mission to determine whether the area's environment has ever been favorable to support microbial life.

Researchers will use Curiosity's calibration plaque to test one of the six-wheeled rover's five science cameras, the Mars Hand Lens Imager (MAHLI).

The "hand lens" in MAHLI's name refers to Earth-bound field geologists' practice of carrying a hand lens for close inspection of rocks they find. When shooting photos in the field, geologists use various calibration methods.

"When a geologist takes pictures of rock outcrops she is studying, she wants an object of [a] known scale in the photographs," said principal investigator Ken Edgett with Malin Space Science Systems in San Diego, Calif. "If it is a whole cliff face, she'll ask a person to stand in the shot. If it is a view from a meter or so away, she might use a rock hammer." [Photos: NASA's New Mars Rover Curiosity]

"If it is a close-up, as the MAHLI can take, she might pull something small out of her pocket. Like a penny," Edgett said.

Centennial cent

Curiosity's 1-cent piece is not just any old penny.

Edgett picked out and purchased the penny with his own funds. A 1909 "VDB" cent, the coin is from the first year Lincoln pennies were minted, the centennial of President Abraham Lincoln's birth. The initials ("VDB") of the coin's designer — Victor David Brenner — are etched onto the coin's reverse.

"The penny is on the MAHLI calibration target as a tip of the hat to geologists' informal practice of placing a coin or other object of known scale in their photographs. A more formal practice is to use an object with [its] scale marked in millimeters, centimeters or meters," Edgett said. "Of course, this penny can't be moved around and placed in MAHLI images; it stays affixed to the rover."

The middle of the target offers a marked scale of black bars in a range of labeled sizes. While the scale will not appear in the photos that MAHLI takes of Martian rocks, knowing the distance from the camera to a rock target will allow scientists to correlate calibration images to each of the investigation images. [Amazing Photos of Mars]

Another part of MAHLI's calibration target plaque displays six patches of pigmented silicone as aids for interpreting color and brightness in images. Five of them – red, green, blue, 40-percent gray and 60-percent gray – are spares from targets on NASA's Mars Exploration Rovers Spirit and Opportunity, which landed on the Red Planet in 2004.

The sixth square, with a fluorescent pigment that glows red when exposed to ultraviolet light, allows verification of an ultraviolet light source on MAHLI.

A stair-stepped area at the bottom of the target, plus the penny, will help with three-dimensional calibration using known surface shapes.

A penny for the public's thoughts

Accompanying the penny on the MAHLI calibration target is a tiny cartoon of a character named "Joe the Martian." Both the coin and the character serve double duty: both are calibration targets and both are intended to engage the public.

"Everyone in the United States can recognize the penny and immediately know how big it is, and can compare that with the rover hardware and Mars materials in the same image," Edgett said. "The public can watch for changes in the penny over the long term on Mars."

"Will it change color? Will it corrode? Will it get pitted by windblown sand?" Edgett said.

The Joe the Martian character is taken from a children's science periodical, "Red Planet Connection," where it was regularly seen when Edgett directed the Mars outreach program at Arizona State University, Tempe, in the 1990s.

Joe was created earlier, as a part of Edgett's schoolwork when he was 9 years old and NASA's Viking missions, launched in 1975, inspired him to dream of becoming a Mars researcher.

"The Joe the Martian on Curiosity really is a 'thank you' from the MAHLI team to the folks who have provided us with the opportunity to study Mars, the U.S. taxpayers," Edgett said. "He's also there to encourage children around the world to set goals that will help them achieve their dreams in whatever interests they pursue."